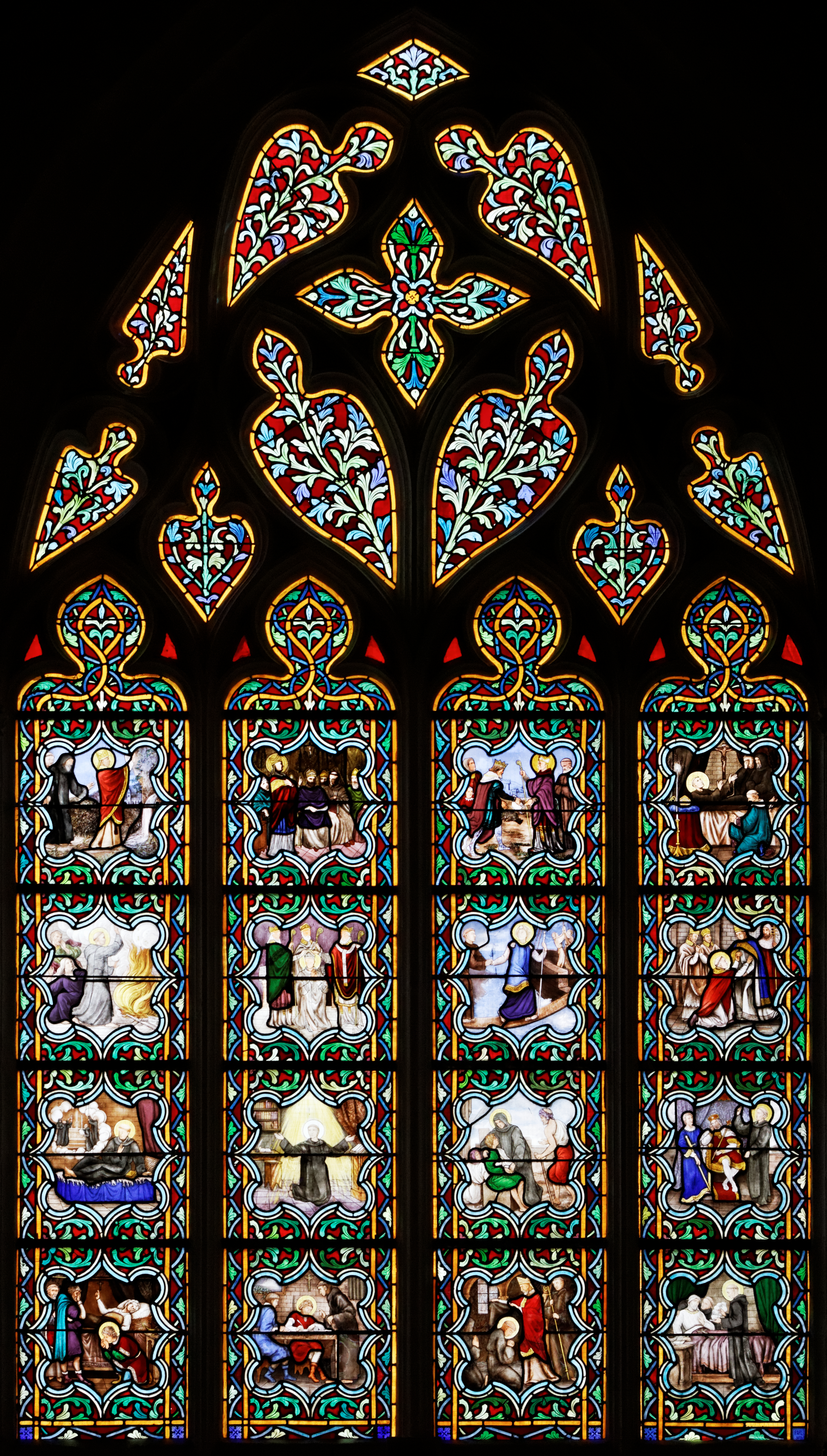

Triptyque de Saint Anselme, Abbaye Notre-Dame du Bec

Église de l’abbatiale de Notre-Dame du

Bec. De gauche à droite: Saint Jérôme, statue du XVe siècle. Triptyque de Saint

Anselme. Saint Grégoire, statue du XVe siècle.

In the abbey church Notre-Dame du Bec,

15th-century works: a triptych of Anselm of Canterbury, a Statue of Gregorius I

Magnus and a statue of Saint Jerome.

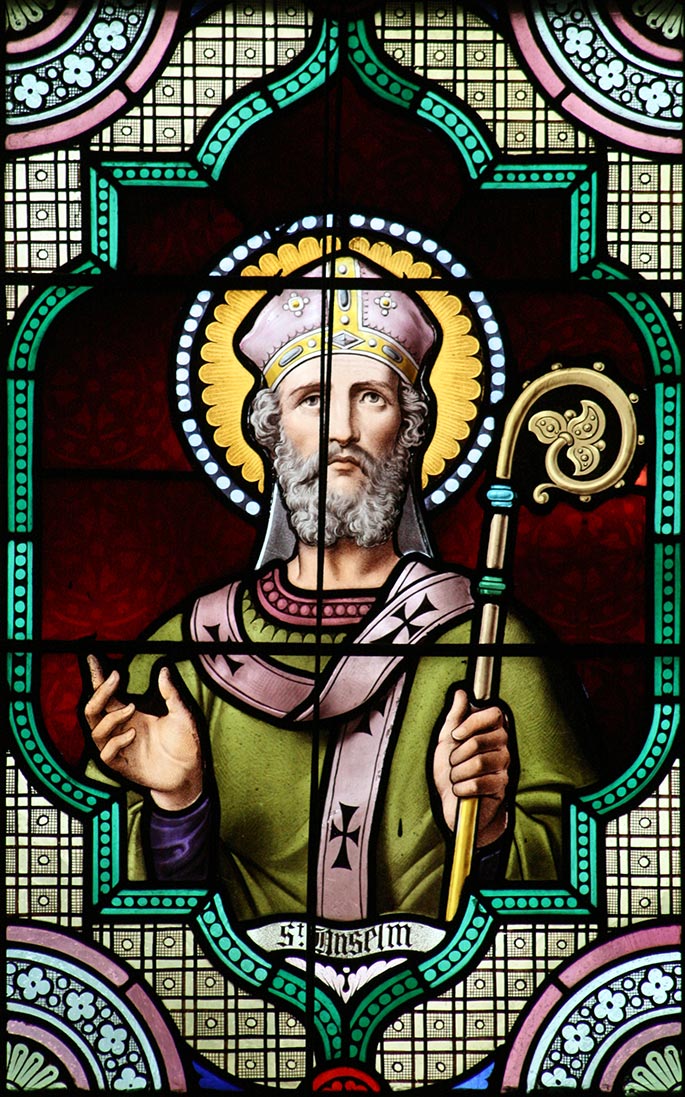

Saint Anselme, évêque et docteur de l'Église

Anselme (1033-1109) naquit dans la Val d'Aoste, il fut moine au Bec en Normandie, puis archevêque de Cantorbéry, vingt ans après le martyre de Thomas Becket. Toute sa vie consista dans une recherche ardente de Dieu, l'Etre parfait, à la lumière de l'intelligence et de la foi. Mais ce contemplatif sut aussi se battre pour défendre la liberté de l'Église.

Saint Anselme de Cantorbéry

Archevêque, docteur de l'Église (+ 1109)

Originaire du Val d'Aoste, il veut se faire moine alors qu'il a 15 ans. Mais son adolescence le fait changer d'avis: la vie mondaine lui semble plus amusante et attirante, plaisant à tous et à toutes. A la mort de sa mère, il quitte son père dont le caractère était invivable et gagne la France "à la recherche du plaisir". Ce qui ne l'empêche pas de poursuivre en même temps ses études. Et c'est ainsi qu'à 27 ans sa vocation de jeunesse se réveillera à l'abbaye du Bec en Normandie où il était venu simplement pour étudier, attiré par la renommée de cette école dirigée par Lanfranc. A peine moine profès, le voilà choisi comme prieur, n'en déplaise aux jaloux. Mais sa douceur gagnera vite les cœurs. Il est élu abbé et mènera de front cette charge et une intense réflexion théologique: selon lui, puisque Dieu est le créateur de la raison, celle-ci, loin de contredire les vérités de la foi, doit pouvoir en rendre compte. A cette époque, des relations étroites existaient entre l'abbaye du Bec et les monastères anglais proches de Cantorbery. En 1093, lors d'une visite de ces monastères, saint Anselme se retrouve élu évêque de Cantorbery. Son attachement à l'indépendance de l'Église contre les prétentions des rois d'Angleterre lui vaudra plusieurs exils. Il aspire à retrouver la paix du cloître, mais le pape ne l'autorise pas à quitter sa charge. C'est donc au milieu des tracas occasionnés par sa réforme de l'Église d'Angleterre qu'il mène à bien l'œuvre théologique qui lui vaudra le titre de "Docteur magnifique".

- Vidéo chronique des saints sur la webTV de la CEF.

Durant l'audience générale du 23 septembre 2009, le Saint-Père a évoqué la figure de saint Anselme, dit d'Aoste, du Bec ou de Canterbury, né à Aoste (Italie) en 1033... Il défendit l'Église anglaise des ingérences politiques des rois Guillaume le Rouge et Henri Ier, ce qui lui coûta d'être exilé en 1103. Anselme consacra les dernières années de sa vie "à la formation morale du clergé et à la recherche théologique", obtenant le titre de Docteur magnifique. "La clarté et la rigueur de sa pensée eurent pour but de porter l'esprit vers la contemplation de Dieu, soulignant que le théologien ne saurait compter sur sa seule intelligence mais devait cultiver une foi profonde". L'activité théologique de saint Anselme "se développa en trois volets: la foi comme don gratuit de Dieu qui doit être accueillie avec humilité, l'expérience qui est l'incarnation de la Parole dans la vie quotidienne, et la connaissance qui n'est pas seulement le fruit de raisonnements mais aussi celui de l'intuition contemplative... Son amour de la vérité et sa soif constante de Dieu...peuvent être pour le chrétien d'aujourd'hui un encouragement à rechercher sans cesse le lien profond qui nous unit au Christ... Le courage dont il fit preuve dans son action pastorale, qui lui causa souvent de l'incompréhension et même d'être exilé, doit inspirer les pasteurs, les consacrés et tous les fidèles dans l'amour de l'Église du Christ". (source: VIS 090923 - 450)

Anselme est né à Aoste en 1033. Éduqué dans la foi et la piété par sa mère, à la mort de celle-ci vit une jeunesse frivole. Bientôt, il se convertit, reprend ses études sous la conduite de Lanfranc, prieur de l'abbaye du Bec. Il choisit alors la vie monastique et reçoit l'habit des mains du bienheureux Herluin, fondateur de cette abbaye, auquel il succèdera en 1078. Il est ensuite appelé au siège épiscopal de Cantorbéry 1093, se trouve en butte à de nombreux débats et tracasseries de la part du roi d'Angleterre.

Il a surtout marqué l'Abbaye du Bec et le diocèse de Cantorbéry par sa foi lucide, son humilité, sa douceur, son esprit de paix et sa tendresse filiale envers la Vierge Marie.

L'Église entière lui doit aussi de remarquables traités de théologie.

Un internaute nous signale:

En 1058 Anselme arrive à Avranches comme enseignant à l'école épiscopale mais surtout comme précepteur du jeune Hugues, fils du vicomte, avec lequel il se lie d'une grande amitié qui durera toute sa vie; Hugues devenu comte de Chester et homme politique, ils seront ensemble influents près du roi notamment pour le mariage écossais d'Henri Ier dont ils sont les auteurs.

Mémoire de saint Anselme, évêque et docteur de l'Église. D'Aoste où il est né,

devenu moine puis abbé du Bec en Normandie, il enseigna à ses frères à avancer

sur le chemin de la perfection et à chercher Dieu par l'intelligence de la foi.

Promu ensuite au siège illustre de Cantorbéry, en Angleterre, il lutta

fermement pour la liberté de l'Église et souffrit pour cela des temps d'exil.

Il mourut enfin dans son Église, le mercredi saint de l'année 1109.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1013/Saint-Anselme-de-Cantorbery.html

Der

hl. Anselm übergibt Mathilde sein Werk. Anselm von Canterbury, Orationes,

Diözese Salzburg, um 1160. Admont, Stiftsbibliothek, Ms. 289, fol. 1v., circa

1160

SAINT ANSELME

Archevêque de Cantorbéry,

Docteur de l'Église

(1034-1109)

Anselme naquit à Aoste,

en Piémont. Sa pieuse mère Ermengarde lui apprit de bonne heure à aimer Dieu et

la Très Sainte Vierge; mais, privé du soutien maternel vers l'âge de quinze

ans, poursuivi dans sa vocation religieuse par un père mondain et intraitable,

il se laissa entraîner par le monde.

Las d'être la victime de

son père, il s'enfuit en France, et se fixa comme étudiant à l'abbaye du Bec,

en Normandie. Là il dit à Lafranc, chef de cette célèbre école: "Trois

chemins me sont ouverts: être religieux au Bec, vivre en ermite, ou rester dans

le monde pour soulager les pauvres avec mes richesses: parlez, je vous

obéis." Lafranc se prononça pour la vie religieuse. Ce jour-là, l'abbaye

du Bec fit la plus brillante de ses conquêtes. Anselme avait vingt-sept ans.

Quand bientôt Lafranc

prit possession du siège archiépiscopal de Cantorbéry, il fut élu prieur de

l'abbaye, malgré toutes ses résistances; il était déjà non seulement un savant,

mais un Saint. De prieur, il devint abbé, et dut encore accepter par force ce

fardeau, dont lui seul se croyait indigne.

Sa vertu croissait avec

la grandeur de ses charges. Le temps que lui laissait libre la conduite du

couvent, il le passait dans l'étude de l'Écriture Sainte et la composition

d'ouvrages pieux ou philosophiques. La prière toutefois passait avant tout le

reste; l'aube le retrouvait fréquemment à genoux. Un jour le frère excitateur,

allant réveiller ses frères pour le chant des Matines, aperçut dans la salle du

chapitre, une vive lumière; c'était le saint abbé en prière, environné d'une

auréole de feu.

Forcé par la voix du

Ciel, le roi d'Angleterre, Guillaume, le nomme archevêque de Cantorbéry;

Anselme refuse obstinément; mais, malgré lui, il est porté en triomphe sur le

trône des Pontifes. Huit mois après, il n'était pas sacré; c'est qu'il exigeait

comme condition la restitution des biens enlevés par le roi à l'Église de

Cantorbéry. Le roi promit; mais il manqua à sa parole, et dès lors Anselme,

inébranlable dans le maintien de ses droits, ne fut plus qu'un grand persécuté.

Obligé de fuir, il

traversa triomphalement la France, et alla visiter le Pape, qui le proclama

hautement "héros de doctrine et de vertu; intrépide dans les combats de la

foi." Quand Anselme apprit la mort tragique de Guillaume dans une partie

de chasse, il s'écria en fondant en larmes: "Hélas! J'eusse donné ma vie

pour lui épargner cette mort terrible!" Anselme put revenir en Angleterre,

vivre quelques années en paix sur son siège, et il vit refleurir la religion

dans son Église.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_anselme.html

Éveil de l'esprit à la

contemplation de Dieu

"Et maintenant,

homme de rien, fuis un moment tes occupations, cache-toi un peu de tes pensées

tumultueuses. Rejette maintenant tes pesants soucis, et remets à plus tard tes

tensions laborieuses. Vaque quelque peu à Dieu, et repose-toi quelque peu en

Lui. Entre dans la cellule de ton âme, exclus tout hormis Dieu et ce qui t'aide

à le chercher ; porte fermée, cherche-le. Dis maintenant, tout mon cœur, dis

maintenant à Dieu : Je cherche ton visage, ton visage, Seigneur, je le

recherche. Et maintenant, Toi Seigneur mon Dieu, enseigne à mon cœur où et

comment Te chercher, où et comment Te trouver. Seigneur, si Tu n'es pas ici, où

Te chercherai-je absent ? Et, si Tu es partout, pourquoi ne Te vois-je pas

présent ? Mais certainement Tu habites la lumière inaccessible. Où est la

lumière inaccessible ? Ou bien comment accéderai-je à la lumière inaccessible ?

Ou qui me conduira et introduira en elle pour qu'en elle je Te voie ? Par quels

signes enfin, par quelle face Te chercherai-je ? Je ne T'ai jamais vu, Seigneur

mon Dieu, je ne connais pas ta face. Que fera, très haut Seigneur, que fera cet

exilé, tien et éloigné ? Que fera ton serviteur, anxieux de ton amour et

projeté loin de ta face. II s'essouffle pour Te voir, et ta face lui est par

trop absente. Il désire accéder à Toi, et ton habitation est inaccessible. Il

souhaite vivement Te trouver, et il ne sait ton lieu. Il se dispose à Te

chercher, et il ignore ton visage. Seigneur, Tu es mon Dieu, Tu es mon

Seigneur, et je ne T'ai jamais vu. Tu m'as fait et fait à nouveau, Tu m'as

conféré tous mes biens, et je ne Te connais pas encore. Bref, j'ai été fait

pour Te voir et je n'ai pas encore fait ce pour quoi j'ai été fait.

Seigneur, et je ne T'ai

jamais vu. Tu m'as fait et fait à nouveau, Tu m'as conféré tous mes biens, et

je ne Te connais pas encore. Bref, j'ai été fait pour Te voir et je n'ai pas

encore fait ce pour quoi j'ai été fait. Et Toi, ô Seigneur, jusques à quand ?

Jusques à quand, Seigneur, nous oublieras-Tu, jusques à quand détournes-Tu de

nous ta face? Quand nous regarderas-Tu et nous exauceras-Tu? Quand

illumineras-Tu nos yeux et nous montreras-Tu ta face? Quand Te rendras-Tu à

nous? Regarde-nous, Seigneur, exauce-nous, illumine-nous, montre-toi à nous.

Rends-toi à nous, que nous soyons bien, nous qui, sans Toi, sommes si mal. Aie

pitié de nos labeurs et de nos efforts vers Toi, nous qui ne valons rien sans

Toi.

Enseigne-moi à Te

chercher, montre-toi à qui Te cherche, car je ne puis Te chercher si Tu ne

m'enseignes, ni Te trouver si Tu ne te montres. Que je Te cherche en désirant,

que je désire en cherchant. Que je trouve en aimant, que j'aime en

trouvant."

Saint Anselme de

Canterbury, évêque : Proslogion, 1.

Prière:

Ô Dieu qui as inspiré à

Saint Anselme un ardent désir de Te trouver dans la prière et la contemplation,

au milieu de l'agitation de ses occupations quotidiennes, aide-nous à

interrompre le rythme fébrile de nos occupations, entre les soucis et les

inquiétudes de la vie moderne, pour parler avec Toi, notre unique espérance et

salut. Nous te Le demandons par Jésus le Christ notre Seigneur.

Par l'Athénée Pontifical

"Regina Apostolorum"

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/spirit/documents/spirit_20000630_anselmo_fr.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 23 septembre

2009

Saint Anselme

Chers frères et sœurs,

A Rome, sur la colline de

l'Aventin, se trouve l'abbaye bénédictine de Saint-Anselme. En tant que siège

d'un institut d'études supérieures et de l'abbé primat des Bénédictins

confédérés, c'est un lieu qui unit la prière, l'étude et le gouvernement, qui

sont précisément les trois activités qui caractérisent la vie du saint auquel

elle est dédiée: Anselme d'Aoste, dont nous célébrons cette année le ix

centenaire de la mort. Les multiples initiatives, promues spécialement par le

diocèse d'Aoste pour cette heureuse occasion, ont souligné l'intérêt que

continue de susciter ce penseur médiéval. Il est connu également comme Anselme

du Bec et Anselme de Canterbury en raison des villes auxquelles il est lié. Qui

est ce personnage auquel trois localités, éloignées entre elles et situées dans

trois nations différentes - Italie, France, Angleterre - se sentent

particulièrement liées? Moine à la vie spirituelle intense, excellent éducateur

de jeunes, théologien possédant une extraordinaire capacité spéculative, sage

homme de gouvernement et défenseur intransigeant de la libertas Ecclesiae, de

la liberté de l'Eglise, Anselme est l'une des personnalités éminentes du

Moyen-âge, qui sut harmoniser toutes ces qualités grâce à une profonde

expérience mystique, qui en guida toujours la pensée et l'action.

Saint Anselme naquit en

1033 (ou au début de 1034), à Aoste, premier-né d'une famille noble. Son père

était un homme rude, dédié aux plaisirs de la vie et dépensant tous ses biens;

sa mère, en revanche, était une femme d'une conduite exemplaire et d'une

profonde religiosité (cf. Eadmero, Vita s. Anselmi, PL 159, col. 49). Ce fut

elle qui prit soin de la formation humaine et religieuse initiale de son fils,

qu'elle confia ensuite aux bénédictins d'un prieuré d'Aoste. Anselme qui,

enfant - comme l'écrit son biographe -, imaginait la demeure du bon Dieu entre

les cimes élevées et enneigées des Alpes, rêva une nuit d'être invité dans

cette demeure splendide par Dieu lui-même, qui s'entretint longuement et aimablement

avec lui, et à la fin, lui offrit à manger "un morceau de pain très

blanc" (ibid., col. 51). Ce rêve suscita en lui la conviction d'être

appelé à accomplir une haute mission. A l'âge de quinze ans, il demanda à être

admis dans l'ordre bénédictin, mais son père s'opposa de toute son autorité et

ne céda pas même lorsque son fils gravement malade, se sentant proche de la

mort, implora l'habit religieux comme suprême réconfort. Après la guérison et

la disparition prématurée de sa mère, Anselme traversa une période de débauche

morale: il négligea ses études et, emporté par les passions terrestres, devint

sourd à l'appel de Dieu. Il quitta le foyer familial et commença à errer à

travers la France à la recherche de nouvelles expériences. Après trois ans, arrivé

en Normandie, il se rendit à l'abbaye bénédictine du Bec, attiré par la

renommée de Lanfranc de Pavie, prieur du monastère. Ce fut pour lui une

rencontre providentielle et décisive pour le reste de sa vie. Sous la direction

de Lanfranc, Anselme reprit en effet avec vigueur ses études, et, en peu de

temps, devint non seulement l'élève préféré, mais également le confident du

maître. Sa vocation monastique se raviva et, après un examen attentif, à l'âge

de 27 ans, il entra dans l'Ordre monastique et fut ordonné prêtre. L'ascèse et

l'étude lui ouvrirent de nouveaux horizons, lui faisant retrouver, à un degré

bien plus élevé, la proximité avec Dieu qu'il avait eue enfant.

Lorsqu'en 1063, Lanfranc

devint abbé de Caen, Anselme, après seulement trois ans de vie monastique, fut

nommé prieur du monastère du Bec et maître de l'école claustrale, révélant des

dons de brillant éducateur. Il n'aimait pas les méthodes autoritaires; il

comparait les jeunes à de petites plantes qui se développent mieux si elles ne

sont pas enfermées dans des serres et il leur accordait une "saine"

liberté. Il était très exigeant avec lui-même et avec les autres dans

l'observance monastique, mais plutôt que d'imposer la discipline il s'efforçait

de la faire suivre par la persuasion. A la mort de l'abbé Herluin, fondateur de

l'abbaye du Bec, Anselme fut élu à l'unanimité à sa succession: c'était en

février 1079. Entretemps, de nombreux moines avaient été appelés à Canterbury

pour apporter aux frères d'outre-Manche le renouveau en cours sur le continent.

Leur œuvre fut bien acceptée, au point que Lanfranc de Pavie, abbé de Caen,

devint le nouvel archevêque de Canterbury et il demanda à Anselme de passer un

certain temps avec lui pour instruire les moines et l'aider dans la situation

difficile où se trouvait sa communauté ecclésiale après l'invasion des

Normands. Le séjour d'Anselme se révéla très fructueux; il gagna la sympathie

et l'estime générale, si bien qu'à la mort de Lanfranc, il fut choisi pour lui

succéder sur le siège archiépiscopal de Canterbury. Il reçut la consécration

épiscopale solennelle en décembre 1093.

Anselme s'engagea

immédiatement dans une lutte énergique pour la liberté de l'Eglise, soutenant

avec courage l'indépendance du pouvoir spirituel par rapport au pouvoir temporel.

Il défendit l'Eglise des ingérences indues des autorités politiques, en

particulier des rois Guillaume le Rouge et Henri I, trouvant encouragement et

appui chez le Pontife Romain, auquel Anselme démontra toujours une adhésion

courageuse et cordiale. Cette fidélité lui coûta également, en 1103, l'amertume

de l'exil de son siège de Canterbury. Et c'est seulement en 1106, lorsque le

roi Henri I renonça à la prétention de conférer les investitures

ecclésiastiques, ainsi qu'au prélèvement des taxes et à la confiscation des

biens de l'Eglise, qu'Anselme put revenir en Angleterre, accueilli dans la joie

par le clergé et par le peuple. Ainsi s'était heureusement conclue la longue

lutte qu'il avait menée avec les armes de la persévérance, de la fierté et de

la bonté. Ce saint archevêque qui suscitait une telle admiration autour de lui,

où qu'il se rende, consacra les dernières années de sa vie en particulier à la

formation morale du clergé et à la recherche intellectuelle sur des sujets

théologiques. Il mourut le 21 avril 1109, accompagné par les paroles de

l'Evangile proclamé lors de la Messe de ce jour: "Vous êtes, vous, ceux

qui sont demeurés constamment avec moi dans mes épreuves; et moi je dispose

pour vous du Royaume comme mon Père en a disposé pour moi: vous mangerez à ma

table en mon Royaume" (Lc 22, 28-30). Le songe de ce mystérieux banquet,

qu'il avait fait enfant tout au début de son chemin spirituel, trouvait ainsi

sa réalisation. Jésus, qui l'avait invité à s'asseoir à sa table, accueillit

saint Anselme, à sa mort, dans le royaume éternel du Père.

"Dieu, je t'en prie,

je veux te connaître, je veux t'aimer et pouvoir profiter de toi. Et si, en

cette vie, je ne suis pas pleinement capable de cela, que je puisse au moins

progresser chaque jour jusqu'à parvenir à la plénitude" (Proslogion, chap.

14). Cette prière permet de comprendre l'âme mystique de ce grand saint de

l'époque médiévale, fondateur de la théologie scolastique, à qui la tradition

chrétienne a donné le titre de "Docteur Magnifique", car il cultiva

un intense désir d'approfondir les Mystères divins, tout en étant cependant

pleinement conscient que le chemin de recherche de Dieu n'est jamais terminé,

tout au moins sur cette terre. La clarté et la rigueur logique de sa pensée ont

toujours eu comme fin d'"élever l'esprit à la contemplation de Dieu"

(ibid., Proemium). Il affirme clairement que celui qui entend faire de la

théologie ne peut pas compter seulement sur son intelligence, mais qu'il doit

cultiver dans le même temps une profonde expérience de foi. L'activité du

théologien, selon saint Anselme, se développe ainsi en trois stades: la foi,

don gratuit de Dieu qu'il faut accueillir avec humilité; l'expérience, qui

consiste à incarner la parole de Dieu dans sa propre existence quotidienne; et

ensuite la véritable connaissance, qui n'est jamais le fruit de raisonnements

aseptisés, mais bien d'une intuition contemplative. A ce propos, restent plus

que jamais utiles également aujourd'hui, pour une saine recherche théologique

et pour quiconque désire approfondir la vérité de la foi, ses paroles célèbres:

"Je ne tente pas, Seigneur, de pénétrer ta profondeur, car je ne peux pas,

même de loin, comparer avec elle mon intellect; mais je désire comprendre, au

moins jusqu'à un certain point, ta vérité, que mon cœur croit et aime. Je ne

cherche pas, en effet, à comprendre pour croire, mais je crois pour

comprendre" (ibid., 1).

* * *

J’accueille avec joie ce

matin les pèlerins francophones. Je salue en particulier les séminaristes

d’Aix-en-Provence, accompagnés de l’Archevêque, Mgr Feidt, les paroisses de

Baie Saint-Paul, au Canada, de Saint-Jacques à Paris, et de Rodez. A l’exemple de

saint Anselme, aimez, vous aussi, l’Eglise du Christ, priez et travaillez pour

elle, sans jamais l’abandonner ou la trahir! Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique!

© Copyright 2009 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Saint

Pie X, encyclique « Communium Rerum », 21 avril 1909

À NOS VÉNÉRABLES FRÈRES, LES PATRIARCHES, PRIMATS,

ARCHEVÊQUES, ÉVÊQUES ET AUTRES ORDINAIRES DE LIEUX AYANT PAIX ET COMMUNION AVEC

LE SIÈGE APOSTOLIQUE.

PIE X, PAPE

Vénérables Frères, Salut et Bénédiction Apostolique.

Au milieu des tristes vicissitudes des affaires

ordinaires, auxquelles se sont ajoutées dernièrement des afflictions

domestiques qui accablent notre âme de douleur, c’est pour nous un sujet de

consolation et de réconfort que ce concert récent de piété filiale de tout le

peuple chrétien, qui ne cesse pas d’être encore « un spectacle pour le monde,

pour les anges et pour les hommes (1) » ; l’état des maux présents l’a, sans

doute, excitée, mais, en définitive, elle dérive toujours de la même cause, à

savoir la charité de Nôtre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ. Car, en effet, comme aucune

vertu digne de ce nom ne peut exister sur la terre que par Jésus-Christ, c’est

à lui seul qu’il faut rapporter les fruits qui en découlent parmi les hommes,

même parmi ceux dont la foi est relâchée ou même qui sont hostiles à la

religion, car, s’il reste encore en eux quelque vestige de la vraie charité,

c’est un effet de cette civilisation apportée par le Christ qu’ils n’ont pu

abolir entièrement ni extirper de la société chrétienne.

Les paroles nous manquent, au milieu de notre émotion, pour exprimer nos

sentiments de reconnaissance envers ceux qui cherchent avec tant de zèle à

procurer des consolations au Père et de l’aide à leurs frères dans les

tribulations générales et privées. Que si déjà nous la leur avons témoignée en

particulier, nous n’avons pas voulu tarder à nous acquitter publiquement de ce

devoir de gratitude, d’abord auprès de vous, vénérables Frères, et par vous,

auprès de tous les fidèles, quels qu’ils soient, confiés à votre sollicitude.

Mais il nous plaît aussi de témoigner en public notre reconnaissance à ces fils

bien-aimés qui, de toutes les parties de la terre, ont accompagné de tant et de

si hauts témoignages d’amour et d’attachement la célébration du cinquantième

anniversaire de notre sacerdoce. Ces tributs d’affection nous ont moins réjoui

pour nous-même que pour la religion et pour l’Eglise, car ils étaient la preuve

d’une foi intrépide et comme une manifestation publique de l’honneur dû au

Christ et à l’Eglise, en raison des hommages rendus à celui que le Seigneur a

voulu placer à la tête de sa famille.

Mais d’autres fruits encore nous ont procuré, sous ce rapport, une grande joie. Car les fêtes célébrées à l’occasion du centième anniversaire de l’établissement des diocèses de l’Amérique du Nord ont donné l’occasion de rendre d’immortelles actions de grâces à Dieu, en raison du grand nombre de fils apportés à l’Eglise catholique. De son côté, la très noble Angleterre a donné le spectacle d’honneurs extraordinaires rendus chez elle à la très Sainte Eucharistie, au milieu d’une couronne d’évêques, nos vénérables frères, en présence de notre légat et avec le concours d’un peuple immense. Et en France aussi, l’Eglise affligée a séché ses larmes en contemplant les splendides triomphes de l’Auguste Sacrement, à Lourdes, en particulier, où nous avons eu la joie de voir fêter solennellement le cinquantième anniversaire de sa célébrité. De ces faits et des autres que les ennemis du nom catholique apprennent que toutes ces solennités extraordinaires, ce culte rendu à l’auguste Mère de Dieu, les honneurs eux-mêmes que l’on a coutume de rendre au Souverain Pontife tendent en dernier lieu à ce que le Christ soit tout et en tous (2), et enfin à ce que, par l’établissement du règne de Dieu sur la terre, le salut éternel des hommes soit assuré.

Le triomphe divin qu’il faut attendre et sur les individus et sur la société

humaine tout entière n’est pas autre chose que le retour des égarés à Dieu par

le Christ, et au Christ par son Eglise, et tel est le but que nous nous

proposons, comme nous l’avons publiquement indiqué dans nos premières lettres

apostoliques E. Supremi Apostolatus cathedra (3) et bien d’autres

fois. Ce retour, nous l’espérons avec confiance ; toutes nos pensées et tous

nos désirs y tendent comme au port, où les tempêtes de la vie présente

elle-même doivent s’apaiser. Et c’est dans ce sentiment aussi qu’en voyant dans

les honneurs publics rendus à l’Eglise comme un signe de ce retour, favorisé de

Dieu, des nations au Christ et d’un attachement plus étroit à Pierre et à

l’Eglise, nous acceptions avec reconnaissance et joie les hommages rendus à

notre humble personne.

Cet attachement affectueux au siège apostolique, qui ne s’est pas montré

toujours et partout de la même manière, semble, par un dessein de la divine

Providence, être devenu d’autant plus étroit que les temps, comme ceux où nous

sommes, sont plus mauvais et plus contraires soit à la saine doctrine, soit à

la sainte discipline, soit à la liberté de l’Eglise. Les saints ont donné

particulièrement des exemples de cette union lorsque le troupeau du Christ

était troublé, ou lorsque l’époque était plus dissolue : à ces maux Dieu a

providentiellement opposé leur vertu et leur sagesse. Parmi eux, il nous plaît

d’en rappeler un seulement dans ces lettres, en raison des solennités dont il

est l’objet à l’occasion du huitième centenaire de sa mort. Nous voulons parler

du saint docteur Augustin Anselme, ce maître si autorisé de la vérité catholique,

ce défenseur si zélé des droits sacrés, aussi bien quand il était moine et abbé

en France, que sacrés, il était archevêque de Cantorbéry et primat

d’Angleterre. Et il ne nous paraît pas hors de propos, après les magnifiques

solennités célébrées en l’honneur de Grégoire le Grand et de Jean Chrysostome,

ces deux lumières, l’un de l’Eglise Occidentale, l’autre de l’Eglise Orientale,

de contempler un autre astre qui, bien que « différent des autres en clarté (4)

», en marchant sur leurs traces, n’a pas projeté un éclat moindre d’exemples et

de doctrine, et l’on pourrait même dire, en quelque sorte, plus puissant, parce

que Anselme est plus près de nous par l’âge, le lieu, la manière d’être, les

études, et que tout en lui se rapproche plus des temps où nous vivons, soit le

genre de luttes qu’il eut à soutenir, soit la forme d’action pastorale qu’il a

mise en usage, soit la manière d’enseigner établie par lui ou par ses disciples

et accréditée surtout pas ses écrits d’où a été tirée « la méthode de défense

de la religion chrétienne et d’instruction des âmes, qui a été celle de tous

les théologiens qui ont enseigné les Saintes Lettres d’après la méthode

scolastique (5) ». Et ainsi, de même dans l’obscurité de la nuit, quand des

astres se couchent, d’autres se lèvent pour éclairer le monde, de même pour

illuminer l’Eglise, aux pères succèdent les fils, parmi lesquels a brillé comme

un astre éclatant le bienheureux Anselme.

Et, en vérité, au milieu des ténèbres de son temps, enlacé dans un réseau de vices et d’erreurs, il a paru, aux yeux des meilleurs juges, surpasser en éclat ses pairs par la splendeur de sa doctrine et de sa sainteté. Il fut, en effet, pour eux, « le prince de la foi et l’ornement de l’Eglise., la gloire de l’épiscopat, celui qui l’emporta sur les hommes les plus éminents de son temps (6) ». Il fut aussi « le sage et le bon, l’orateur éclatant, le brillant génie (7) », dont la renommée s’étendit au point qu’on put croire avec raison de lui qu’il ne se serait trouvé personne sur la terre pour vouloir dire : « Anselme m’est inférieur ou seulement mon égal (8). » Et pour cela, il fut considéré des rois, des princes, des Souverains Pontifes. Et non seulement il était cher à ses confrères et au peuple fidèle, « mais à ses ennemis eux-mêmes (9) ». Simple abbé encore, il reçut des lettres pleines d’estime et de bienveillance de ce grand et vaillant Pontife Grégoire VII, « qui se recommandait ainsi que l’Eglise catholique à ses prières 110) ». À lui aussi Urbain II « décernera la palme de la religion et de la science (11) ». Dans plusieurs lettres des plus affectueuses, Pascal II exalta « sa piété, sa foi puissante, son zèle instant (12) », toujours disposé, en raison de l’autorité particulière de sa religion et de sa sagesse, à accéder aux demandes de sa fraternité, et n’hésitant pas à le proclamer le plus sage et le plus religieux des évêques d’Angleterre.

Pour lui, cependant, il ne se considérait que comme un être misérable, un

pauvre petit personnage ignoré, un homme de minime science, un pêcheur dans sa

vie. Mais, tout en ayant de si bas sentiments de lui-même, il ne s’en élevait

pas moins haut contre les pensées et les jugements des hommes dépravés par les

mauvaises mœurs et les fausses doctrines, dont la sainte écriture a dit : «

L’homme animal ne comprend pas les choses de l’esprit de Dieu (13). » Mais ce

qu’il y a de plus admirable, c’est que sa grandeur d’âme et son invincible

fermeté, mise à l’épreuve de tant de tracasseries, de persécutions et

d’expulsions, s’alliait chez lui à une telle douceur et aménité qu’il brisait

la colère de ceux qui s’emportaient le plus contre lui et se conciliait leur

bienveillance. Et ainsi ceux qui avaient à souffrir à cause de lui le louaient

de ce qu’il était bon (14).

Il y avait en lui une admirable harmonie et convenance des qualités que la

plupart des hommes croient, à tort, ne pas pouvoir s’accorder entre elles et

même se combattre mutuellement : ainsi la grandeur unie à la candeur, la

modestie jointe au talent, la douceur avec la force, la piété et la science,

qui s’alliaient si bien en lui que, dans toute sa vie, comme à l’époque de son

noviciat dans son institut religieux, « il parut à tous un admirable modèle de

sainteté et de doctrine (15) ».

Et ce double mérite d’Anselme ne resta pas confiné dans les murs d’une maison

ou dans les limites d’un magister, mais, comme s’élançant d’une tente de

soldat, il se produisit au soleil et à la poussière. Etant venu dans les temps

dont nous avons parlé, il eut à combattre terriblement pour la justice et la

vérité.

Et lui qui était porté, par sa nature, aux études contemplatives, il se trouva

engagé dans les plus nombreuses et les plus difficiles affaires, et, ayant

embrassé la sainte milice, il tomba en pleine bataille et dans la mêlée la plus

âpre. Doux et paisible comme il était naturellement, il fut obligé, pour la

défense de la doctrine et du droit de l’Eglise, d’abandonner le charme d’une

vie tranquille, de renoncer à l’amitié et à la faveur des grands, de rompre les

doux liens qui l’unissaient à ses confrères dans sa famille religieuse et aux

évêques compagnons de ses travaux, pour s’engager dans les luttes quotidiennes

et s’exposer à tous les genres d’épreuves. Il trouva, en effet, l’Angleterre en

proie aux passions et aux crises, et il lui fallut combattre à la fois les rois

et les princes, de qui dépendaient les Eglises et auxquels on avait laissé le

sort des peuples, les ministres du culte lâches ou indignes de leur saint

ministère, les grands et le peuple ignorants de tout et adonnés à tous les

vices, et cela, avec une ardeur qui ne défaillit jamais dans la défense de la foi,

des mœurs, de la discipline et de l’immunité ecclésiastiques, au point d’être

vraiment le rempart de la doctrine et de la sainteté, digne à tous égards de

cet autre éloge que fit de lui le pape Pascal nommé plus haut : « Nous rendons

grâces à Dieu de ce qu’en toi l’autorité épiscopale vit toujours et que, placé

au milieu de barbares, rien, ni la violence des tyrans, ni la faveur des

puissants, ni la menace du feu, ni la contrainte militaire, ne t’empêche de

proclamer la vérité » ; et, ailleurs : « Nous exultons de joie, parce que, la

grâce de Dieu aidant, ni les menaces ne t’ébranlent, ni les promesses ne te

séduisent (16) ».

De tout cela, vénérables Frères, à nous, comme à notre prédécesseur Pascal, il

nous est permis, au bout de huit siècles, de nous réjouir encore et de faire

écho à sa voix, en rendant grâces à Dieu. Mais il nos plaît également de vous

inviter aussi à contempler cette lumière de sainteté et de doctrine qui s’est

levée en Italie, a brillé pendant plus de trente ans en France, plus de quinze

en Angleterre, et a été pour l’Eglise universelle enfin un secours et un

ornement.

Que si Anselme a excellé en œuvres et en paroles, c’est-à-dire, si par l’emploi

de sa vie et de sa doctrine, si par sa puissance de méditation et d’action, si

en combattant avec force et en tendant avec douceur à la paix il a remporté

pour l’Eglise de splendides triomphes et a procuré à la société civile

d’insignes bienfaits, tout cela est à imiter en lui, puisque, dans tout le

cours de sa vie et l’exercice de son ministère, il s’est toujours tenu

fermement uni au Christ et à l’Eglise.

En ayant soin de nous inculquer dans l’esprit ses exemples, à l’occasion de la

commémoration solennelle de ce grand Docteur, nous aurons de quoi, vénérables

Frères, amplement admirer et imiter. De cette contemplation, résultera surtout

un accroissement de force et d’encouragement pour remplir courageusement les

fonctions, souvent si ardues et si pleines de soucis du saint ministère, pour

travailler ardemment à tout restaurer dans le Christ « pour que le Christ soit

formé en tous (17) » et principalement en ceux qui s’élèvent pour l’espoir du

sacerdoce, pour défendre fermement le magistère de l’Eglise, et lutter

énergiquement pour la liberté de l’épouse du Christ, pour la sauvegarde des

droits d’institution divine et enfin pour tout ce qui importe à la défense du

Souverain Pontificat.

Car vous n’ignorez pas, vénérables Frères, après toutes les occasions que vous

avez eues d’en gémir avec nous, à quels temps malheureux nous sommes arrivés et

combien est triste l’état de choses présent, et à l’indicible douleur causée en

nous par les maux publics s’est ajoutée la cruelle blessure que nous avons

ressentie des divers attentats commis contre le clergé, et aussi les

empêchements apportés à l’administration des secours de l’Eglise à ses enfants

malheureux, au mépris de ses droits maternels de soins et de sollicitudes

envers eux. Nous en passons beaucoup d’autres sous silence, de ceux qui ont été

perfidement ou astucieusement ourdis pour la perle de l’Eglise, ou

audacieusement accomplis, en violation du droit public et au mépris de toute

loi naturelle d’équité et de justice.

Et ce qui est plus grave, c’est que de tels attentats

ont été commis dans les pays sur lesquels les bienfaits de la civilisation ont

été répandus le plus abondamment par l’Eglise. Qu’y a-t-il, en effet, de plus

cruel que de voir des fils que l’Eglise a nourris comme ses aînés et qu’elle a

élevés dans sa fleur et dans sa force ne pas hésiter à tourner leurs coups

contre le sein de la mère la plus aimante ?

Et la condition des autres pays n’est guère faite non plus pour nous consoler,

car, si la forme d’hostilité est différente, c’est la même haine qui s’exerce

déjà ou qui s’apprête à sortir bientôt de l’ombre des complots ténébreux. Car

tel est le but suprême chez les nations ou les bienfaits de la religion

chrétienne se sont fait le plus sentir : dépouiller l’Eglise de tous ses droits

et en agir avec elle comme si elle n’était pas, en droit et par elle- même, une

société parfaite, ainsi que l’a instituée le divin réparateur de notre humanité

; abolir son règne qui, tout en s’appliquant surtout et directement aux âmes,

ne tend pas moins à la conservation du bien social qu’au salut éternel des

hommes, tout disposer, enfin, pour que, sous le nom menteur de liberté, règne

une licence effrénée à la place de l’autorité de Dieu. Et pendant qu’ils

travaillent à établir, par le règne des vices et des passions, une servitude

universelle et à précipiter la société à une catastrophe « car le péché fait le

malheur des peuples (18) », ils ne cessent de crier : « Nous ne voulons pas que

celui-là règne sur nous (19) ». De là, la proscription des ordres religieux,

qui ont toujours été d’un si grand secours et d’un si grand ornement pour

l’Eglise et qui ont été les principaux promoteurs de la civilisation et de la

science parmi les nations barbares et ses propagateurs les plus zélés chez les

peuples cultivés ; de là, la destruction ou la spoliation des instituts de

charité chrétienne ; de là, le mépris affiché du clergé, à qui l’on fait une

telle opposition que son action en est contrariée ou à qui l’on interdit ou

l’on limite tout ministère public, ou à qui on ne laisse aucune part dans

l’éducation de la jeunesse ; de là, toute action chrétienne d’utilité publique

empêchée ; les hommes les plus distingués qui font profession de la foi

catholique écartés des fonctions ou comptés pour rien, injuriés incessamment,

traqués comme une espèce inférieure et abjecte et plus ou moins près de voir le

jour où, par l’aggravation des lois hostiles, il ne leur sera même plus permis

de s’occuper de rien de ce qui constitue l’action publique.

Et cependant, les auteurs de cette guerre si acharnée et si perfide s’en vont

disant qu’ils ne sont inspirés d’aucun autre motif que du culte de la liberté

et du zèle du progrès et même de l’amour de la patrie, et en cela ils mentent

comme leur père, qui fut « homicide dès le commencement » et qui, « lorsqu’il

ment, parle de son propre fond, parce qu’il est menteur (20) », et animé d’une

haine inextinguible contre Dieu et l’espèce humaine. Hommes impudents qui

s’efforcent de donner des prétextes et de dresser des pièges aux oreilles

étourdies. Car ce n’est ni le doux amour de la patrie, ni le souci du peuple ni

aucun motif de bien et d’honnête qui les pousse à cette guerre impie, mais

uniquement leur fureur insensée contre Dieu et contre l’Eglise, son œuvre

admirable. De cette haine délibérée, comme d’une source empoisonnée, découlent

ces projets scélérats qui tendent à opprimer l’Eglise et à l’exclure de la

société humaine ; de là, ces voix grossières qui proclament à l’envi qu’elle

est morte, quand on ne cesse cependant de la combattre, et même quand on en

arrive à ce point d’audace et de folie de l’accuser, après qu’on l’a dépouillée

de toute liberté, de ne servir de rien pour l’humanité et de n’être d’aucune

utilité pour l’Etat. C’est le même esprit d’hostilité qui fait que les mêmes

hommes dissimulent perfidement ou passent sous silence les bienfaits les plus

certains de l’Eglise et du siège apostolique et même qu’ils saisissent toute

occasion de jeter habilement sur elle le soupçon et la défiance dans l’esprit

et les oreilles de la multitude, en faussant tous les actes et toutes les

paroles de l’Eglise et en les interprétant comme autant de dangers pour la

société, alors qu’on ne saurait douter, au contraire, que les progrès de la

liberté et de la civilisation émanent principalement de Jésus-Christ par son

Eglise.

Très souvent, Vénérables Frères, mais surtout dans notre allocution prononcée au Consistoire du 16 décembre 1907, nous vous avons exhortés à la plus soigneuse vigilance contre les menaces de cette guerre conduite par l’ennemi du dehors, que nous voyons, ici, en lutte ouverte, et comme en bataille rangée, ailleurs par des ruses insidieuses et à force de retranchements, mais partout, de quelque manière, livrer des assauts à l’Eglise.

Mais il est une guerre d’un autre genre, une guerre intestine, domestique, et

d’autant plus funeste qu’elle apparaît moins au dehors, qu’il nous faut

dénoncer et réprimer avec non moins de décision qu’elle nous occasionne de

douleur. Celle-là a été machinée par quelques fils de perdition qui se tiennent

cachés dans le sein même de l’Eglise pour la mieux pouvoir déchirer, et dont

les coups, portés avec une détermination délibérée et raisonnée, frappent

l’Eglise dans son âme, ainsi qu’un tronc dans sa racine.

Ce que se proposent ceux-ci, c’est de troubler les sources mêmes de la vie et

de la doctrine chrétiennes ; de réduire en lambeaux le dépôt sacré de la foi ;

de saper dans ses fondements l’institution divine en livrant au mépris le

magistère pontifical et l’autorité des évêques ; d’assigner à l’Eglise une

forme nouvelle, des lois nouvelles, un droit nouveau, au gré et à l’image

monstrueuse des opinions mauvaises qu’ils professent ; enfin de déformer toute

la face de l’Epouse de Dieu, au nom – tant ils sont fascinés par la vaine

splendeur d’une culture ultra-moderne – au nom d’une fausse science dont

l’apôtre, à plusieurs reprises, nous ordonne de nous garder en nous disant

: Veillez que personne ne vous trompe par la philosophie et par

d’inconsistantes faussetés selon l’opinion des hommes, selon les éléments du

monde et non selon le Christ (21).

Séduits par cette apparence de philosophie et par cette contrefaçon vaine

d’érudition, portée à l’ostentation et jointe à une audace de jugement

excessive, plusieurs se sont évanouis dans leurs pensées (22), et, repoussant

la bonne conscience, ont fait naufrage quant à la foi (23) ; d’autres,

tiraillés en tous sens par d’inconciliables idées, sont comme écrasés sous les

flots des opinions contradictoires et ne savent plus vers quel rivage chercher

refuge ; d’autres encore, abusant des loisirs qu’ils se font et des études,

s’acharnent, par un vain labeur, à édifier des théories aussi vides que

difficiles, ce qui a pour effet de les détourner de l’étude des choses divines

et des sources pures de la doctrine. Et, en aucune façon, cette peste

pernicieuse, qui doit son nom de modernisme à la fureur de nouveauté malsaine

d’où elle est sortie, encore qu’elle ait été dénoncée plusieurs fois et que

l’intempérance de ses propres fauteurs l’ait dépouillée de tous ses voiles, ne

cesse pas de faire de graves torts à la chrétienté. Ce poison se cache partout,

dans les veines et dans les organes de la société actuelle, qui a cessé de

connaitre le Christ et l’Eglise ; mais il se propage surtout, comme un ulcère,

dans la jeunesse en formation, qui n’a nulle expérience des choses et dont

l’esprit est plein de témérité.

La raison pour laquelle les choses en sont venues là, ce n’est pas que ces

hommes jouissent d’une doctrine solide ni distinguée ; car il ne saurait y

avoir aucune véritable dissension entre la raison et la foi (24). La vraie

cause, c’est que ces hommes ont d’eux-mêmes un sentiment exagéré, et qu’ils

s’admirent ; c’est qu’ils vivent sous un ciel devenu comme impur, dans un air

lourd où ne circule que le vent pestifère du temps ; c’est que la connaissance

qu’ils ont des choses sacrées, connaissance ou bien nulle ou bien confuse et

mélangée, se joint en eux à un orgueil qui ressemble à de la folie. La

contagion de cette misère est grandement favorisée par la disparition de la foi

en Dieu et par l’éloignement où l’on se tient de lui. Et, en effet, ceux que

cette passion aveugle de nouveautés pousse à l’aventure devant eux, s’imaginent

facilement avoir assez de force pour, soit ouvertement, soit avec des

dissimulations, secouer le joug de l’autorité divine, et se faire à eux-mêmes

une religion comme circonscrite dans les limites de la nature et accommodée à

l’esprit de chacun d’eux ; religion qui emprunte le nom et l’apparence de la

religion chrétienne, mais qui, en réalité, est aussi éloignée que possible de

la vie et de la vérité qui se trouvent dans celle-ci.

Ainsi, les guerres nouvelles contre toutes les choses divines sont une continuation de la guerre éternelle ; la façon de combattre seule a été changée ; et cela, d’autant plus dangereusement que sont plus adroites les armes de la piété simulée, de la candeur jouée, et de l’âpre volonté qu’emploient les factieux à unir les choses les plus contraires qui puissent être, à savoir, les délires de la faible science humaine et la foi divine, l’esprit incertain de ce siècle et la constance et la dignité de l’Eglise.

Ces choses, Vénérables Frères, vous vous en plaignez avec nous ; mais vous ne

perdez pas pour cela tout courage, ni n’abandonnez tout espoir. Vous savez, en

effet, quelles terribles luttes les âges anciens ont livrées à la chrétienté,

encore qu’elles ne fussent pas semblables à celle qu’on lui livre aujourd’hui.

Et sur ce point, il vous plaira de vous reporter d’esprit et de cœur aux temps

où vécut saint Anselme, temps qui furent des plus difficiles, ainsi que

l’histoire nous l’apprend. Il fallut, à cette époque, combattre pour l’autel et

pour le foyer, c’est-à-dire pour la sainteté du droit public, pour la liberté,

pour l’humanité et pour la doctrine, toutes choses dont la protection était

commise à l’Eglise seule ; il fallut résister à la violence des princes, qui

confondaient communément le droit sacré et le profane ; il fallut extirper les vices,

cultiver les intelligences, ramener à la politesse et à la civilisation les

hommes qui n’avaient pas encore oublié la vieille barbarie ; il fallut diriger

le clergé, dont une partie n’agissait pas assez ou agissait sans discrétion, et

dont plusieurs de ses membres, livrés à de basses intrigues, se soumettaient

trop souvent, corps et âme, à la domination des princes dont le caprice les

appelait aux dignités.

Tel était l’état des choses, surtout dans ces contrées dans lesquelles Anselme

appliqua son zèle secourable et sa sollicitude, soit qu’il enseignât comme

docteur, soit qu’il donnât l’exemple de la vie religieuse, soit que, comme

archevêque et comme primat, il se multipliât en industries et fît porter sur

tout sa vigilance infatigable. Les provinces des Gaules et les îles

Britanniques, les premières soumises, peu de siècles plus tôt à la domination

normande, les autres reçues depuis peu dans le sein de la sainte Eglise

éprouvèrent surtout les effets de sa bienfaisance. L’un et l’autre de ces deux

peuples, agités à l’intérieur par des séditions incessantes, et harcelés, en

plus, par des guerres étrangères, s’étaient, par suite de ces causes, relâchés

de la discipline des princes aux sujets et du clergé au peuple.

Les plus grands hommes de cette époque, au nombre desquels Lanfranc, le vieux

maître d’Anselme lui-même et son prédécesseur au siège de Cantorbéry, n’ont pas

cessé de se répandre en plaintes amères sur ces désordres. Mais surtout, il en

fut ainsi des pontifes romains, dont il nous suffira de citer par son nom un

seul, homme d’une force d’âme invincible, défenseur intrépide de la justice,

protecteur constant des droits et de la liberté de l’Eglise, gardien très

attentif et au besoin vengeur de la discipline du clergé. C’est à savoir

Grégoire VII.

Imitateur zélé des exemples de ces grands hommes, Anselme, laissant un libre

cours à sa douleur, écrivait à un prince, souverain de sa propre nation, qui

avait coutume de se glorifier de lui être uni à la fois par les liens de la

parenté et par ceux de l’amitié, ces paroles qui semblent des cris : « Vous

voyez, mon très cher Seigneur, de quelle façon notre mère l’Eglise de Dieu, que

Dieu nomme sa tendre amie et son épouse bien-aimée, est foulée aux pieds par

les mauvais princes ; comment, pour leur éternelle damnation, elle est jetée

dans la tribulation par ceux-là mêmes à qui elle a été confiée par Dieu comme à

des avocats chargés de sa défense ; avec quelle présomption ils ont usurpé ses

biens pour les réduire à leur usage personnel ; avec quelle cruauté ils

changent en servitude sa liberté; avec quelle impiété ils méprisent et

dissipent sa loi et ses enseignements. Dédaignant d’obéir aux décrets du

Pontife apostolique, promulgués pour garder sa force à la religion chrétienne,

ils se rebellent contre l’apôtre Pierre, dont ce Pontife tient la place, et

contre le Christ lui-même, qui a confié l’Eglise à Pierre… Tous ceux qui ne

veulent pas se soumettre à la loi de Dieu doivent être réputés. sans aucun

doute possible, comme les ennemis de Dieu » (25).

C’est ainsi que parlait Anselme, et il serait à souhaiter que ses paroles

eussent été reçues pieusement non seulement par le prince et par ceux qui lui

succédèrent, mais encore par d’autres rois et d’autres peuples qu’il embrassa

d’un tel amour, qu’il entoura de tant de sollicitude et qu’il combla de tant de

bienfaits.

Les tempêtes de persécution, les spoliations, les exils, les vexations de

toutes sortes qui furent dirigées contre lui, particulièrement dans l’exercice

de sa charge épiscopale, n’énervèrent pas sa vertu, ne le détachèrent pas de

l’étroite union qui le liait à son Eglise et au Saint-Siège apostolique. Au

contraire, il s’y attachait plus étroitement que jamais. C’est ainsi qu’abreuvé

d’angoisses, tiraillé par toutes sortes de soucis, il écrivait à notre

prédécesseur le pape Pascal, que nous avons déjà nommé : Je ne crains ni

l’exil, ni la pauvreté, ni les tortures, ni la mort, parce que, par la grâce

réconfortante de Dieu, mon cœur est préparé à tout pour l’obéissance au

Saint-Siège apostolique et pour la liberté de ma mère l’Eglise du Christ »

(26).

S’il cherche une protection, une aide et un refuge auprès de la Chaire de

Pierre, c’est, écrit-il, pour que jamais la fermeté de la discipline

ecclésiastique et de l’autorité apostolique ne soit, en aucune manière,

affaiblie ni par lui, ni à propos de lui.

Il s’en explique ainsi dans les lettres qu’il envoie à deux illustres chefs de

l’Eglise Romaine. Et il en donne cette raison, dans laquelle nous apparaît dans

toute sa dignité son courage de pasteur fidèle : « Je préfère en effet mourir,

et, tant que je vivrai, être en butte à toutes les misères parmi l’exil, que de

voir, soit à cause de moi, soit par le fait de mon exemple, l’honneur de

l’Eglise de Dieu violé de quelque façon » (27).

Ces trois choses, l’honneur de l’Eglise, sa liberté et son intégrité, sont jour et nuit l’objet que ne perd point de vue l’esprit du Saint ; pour le maintien de ces trois choses, il importune Dieu de ses larmes, de ses prières et de ses sacrifices ; pour leur accroissement, toutes ses forces sont tendues, et il applique à résister à ce qui les met en péril toute l’énergie de sa patience et de sa force ; il emploie à les protéger toute son activité, ses actes, ses écrits, sa voix. C’est à leur défense qu’il convie les religieux ses frères, les évêques, le clergé et le peuple fidèle, par des exhortations sans fin, douces et fortes, qu’il fait plus sévères pour les princes qui, pour leur grand malheur et pour celui de leurs sujets, méconnaissent les droits de la liberté de l’Eglise.

Ces nobles cris pour la liberté de l’Eglise s’adaptent bien au présent ; et ils

sont bien dignes de ceux que le Saint-Esprit a placés, en qualité

d’évêques, pour gouverner l’Eglise de Dieu (28).

Ils ne manquent point d’efficace, même quand, par suite de la ruine de la foi,

des mœurs, de la dissolution d’opinions erronées, et l’opposition de préjugés

malfaisants, ils sont reçus par des oreilles qui ne veulent pas les entendre.

C’est à nous, Vénérables Frères, à nous surtout, vous le savez, que s’adresse

cet avis divin : Crie, ne cesse pas, élève la voix comme le son de la

trompette (29) ; et cela nous est dit surtout quand le Très-Haut

a fait entendre sa propre voix (30), dans le

frémissement de la nature entière et dans de terrifiques calamités ; sa voix

qui ébranle la terre ; sa voix dont les éclats, importuns à nos oreilles

d’hommes, nous disent et nous redisent très haut que ce qui n’est pas éternel

n’est que néant ; que nous n’avons pas ici-bas une demeure permanente, mais que

nous en cherchons une future (31) ; sa voix, voix de justice autant que de

miséricorde, qui rappelle au sentier du bien et du droit les peuples perdus.

Dans ces infortunes publiques, Notre devoir est de parler plus haut encore et

d’enseigner les graves vérités de Dieu non pas seulement aux petits, mais aux

plus grands, à ceux qui vivent heureux, aux arbitres des Nations, et à ceux qui

sont appelés au gouvernement des Etats ; de leur notifier ces sentences d’une

fermeté inébranlable, dont l’Histoire si souvent a confirmé la vérité dans des

pages écrites par du sang, et dont voici quelques exemples : le péché rend

les peuples malheureux (32) ; les puissants seront tourmentés

puissamment (33) ; –et celui-ci encore, qui est tiré du psaume II : Et

maintenant, rois, comprenez ; instruisez-vous, vous qui jugez la terre.

Appréhendez la discipline, de peur que le Seigneur ne s’irrite contre vous et

que vous ne veniez périr hors de la voie juste. De ces menaces,

l’accomplissement le plus rigoureux est à craindre, lorsque l’iniquité publique

s’aggrave, lorsque ceux qui dirigent et le reste des citoyens commettent ce

crime d’entre les crimes, de chasser Dieu d’entre eux et de méconnaître

l’Eglise : car de cette double apostasie résulte la perturbation de toutes

choses et une moisson infinie de misères tant pour les individus que pour la

société entière.

Que si, comme il n’est pas rare qu’il arrive, même

chez les bons, il peut nous arriver de nous rendre complice de tels crimes en

nous taisant ou en les acceptant, il faut que les pasteurs sacrés regardent,

chacun à part soi, comme ayant été dit pour eux, et qu’ils rappellent à

l’occasion aux autres, ce qu’Anselmeécrivait au très puissant prince de Flandre

: « Je vous prie, je vous supplie, je vous avertis, je vous conseille, mon

seigneur, comme un ami fidèle de votre âme qui vous aime vraiment en Dieu, de

ne jamais penser que vous amoindrissez la dignité de vôtre puissance lorsque vous

défendez par amour la liberté de l’épouse de Dieu et de votre mère l’Eglise ;

ne croyez pas que vous vous diminuez en l’exaltant, ne croyez pas vous

affaiblir alors que vous la fortifiez. Voyez, considérez autour de vous; les

exemples s’offrent à vous; considérez les princes qui l’attaquent et la foulent

aux pieds. A quoi cela leur sert-il; où en arrivent-ils ? La réponse est assez

patente, et n’a pas besoin d’être faite (34). »

La

même chose est exprimée d’une façon plus éloquente, avec une force et une

douceur de mots toujours égale, dans ce qu’Anselme écrivit à Baudoin, roi

de Jérusalem : « C’est comme un très fidèle ami que je vous en prie, que je

vous en avertis, que je vous en supplie, et que je le demande à Dieu pour vous

: vivez comme sous la loi de Dieu, soumettant votre volonté en toutes choses à

celle de Dieu. Ne croyez pas, comme plusieurs mauvais rois, que l’Eglise de

Dieu vous a été livrée ainsi qu’un esclave à son maître, sachez qu’elle vous

est confiée comme à un avocat et à un défenseur. Dieu n’a rien de plus cher en

ce monde que la liberté de son Eglise. Ceux qui veulent la dominer plutôt que

la servir prouvent ainsi manifestement qu’ils sont les adversaires de Dieu.

Dieu veut que son épouse soit libre, et non au service de personne. Ceux qui la

traitent et l’honorent comme leur mère se montrent véritablement ses fils et

les fils de Dieu. Quant à ceux qui prétendent la dominer comme si elle leur

était soumise, ils se font par cela, non ses fils, mais des étrangers, et c’est

pourquoi ils sont justement déshérités des promesses qu’elle a reçues de Dieu

en manière de dot (35). »

C’est ainsi que l’amour fervent de ce saint personnage pour l’Eglise jaillissait de son cœur : c’est ainsi qu’éclatait son souci de la liberté dont il désirait la défense, qui est la chose la plus nécessaire dans un gouvernement chrétien, en même temps qu’elle est la plus chère à Dieu même, ainsi que l’éminent docteur l’enseigne dans cette brève et vibrante affirmation : « Dieu n’a rien de plus cher au monde que la liberté de son Eglise. » Et, Vénérables Frères, il n’y a rien non plus par quoi notre pensée et notre sentiment soient exprimés plus clairement que par la répétition de ces paroles que nous venons de rapporter.

Nous nous plaisons aussi à emprunter à saint Anselme les avertissements qu’il

adressait aux princes et aux seigneurs. A la reine d’Angleterre, Mathilde, il

écrivait : « Si voulez rendre grâce d’une manière qui soit droite, qui soit

bonne, qui soit efficace par le fait même, considérez cette reine qu’il a plu à

Dieu de se choisir dans ce monde-ci. Oui, considérez-la, vous dis-je,

exaltez-la, honorez-la, défendez-la, afin qu’avec elle et en elle, vous

plaisiez à Dieu, vous aussi, et que vous régniez avec elle dans l’éternelle

béatitude (36). Surtout s’il vous arrive de voir que votre fils s’enfle de sa

puissance terrestre, oublieux de cette mère si aimante, ou se rebelle contre

son doux empire, gardez ceci dans votre mémoire : c’est à vous qu’il appartient

de rappeler souvent, que ce semble opportun ou non, au prince qui vous doit la

vie, qu’il a à se conduire non pas comme le seigneur, mais comme l’avocat de

l’Eglise, non pas comme son bâtard mais comme son fils légitime (37). »

Il

est de notre charge, et il nous sied particulièrement de persuader aux hommes,

et de tâcher de graver dans leurs âmes ces autres paroles, si empreintes de

sens paternel et de noblesse, écrites encore par saint Anselme : « Si

j’entends à propos de vous quelque chose qui déplaît à Dieu et qui ne vous

convient pas, et si, en l’apprenant, je néglige de vous avertir, c’est que je

ne crains pas Dieu, et que je ne vous aime pas comme je dois (38). » Ainsi,

nous-même, s’il vient à notre connaissance que vous traitez les Eglises qui

sont dans vos mains autrement qu’il ne faut pour leur bien et celui de vos

âmes, alors, imitant saint Anselme, nous devons nous remettre « à

vous prier, à vous conseiller, et à vous avertir de ne pas traiter négligemment

ces choses, et de vous hâter de corriger ce qui, par votre conscience, vous est

montré comme devant être corrigé » (39). Car nous ne devons rien négliger de ce

qui peut être corrigé, parce que Dieu demande compte à tous les hommes, non

seulement du mal qu’ils font, mais encore des maux qu’ils ne corrigent pas

alors qu’ils le pourraient faire. Et plus il leur est donné de puissance pour

la réformation, plus strictement aussi Dieu exige d’eux qu’ils veuillent le

bien et qu’ils le fassent selon la puissance qu’il leur en a miséricordieusement

octroyée. « Si vous ne pouvez pas faire tout à la fois, vous ne devez pas pour

cela omettre de vous efforcer d’aller toujours de mieux en mieux; car Dieu a

pour coutume de parfaire, dans sa bonté, les bons propos et les bons efforts,

et de les rétribuer par une heureuse plénitude (40). »

Ces enseignements, et d’autres du même genre, que saint Anselme a inculqués avec force et avec sagesse aux rois et aux hommes puissants, conviennent aux pasteurs sacrés et aux princes de l’Eglise plus qu’à personne, parce que à eux plus qu’à personne est commise la défense de la vérité, de la justice et de la religion. Les temps nous ont engagés en de nombreuses difficultés, et tant d’embûches nous sont tendues, que c’est à peine si aujourd’hui il nous reste un lieu sûr où nous puissions faire notre devoir. Tandis que les freins sont lâchés à la licence universelle et que règne l’impunité, on s’acharne avec âpreté à tenir l’Eglise enchaînée, et, tandis qu’on conserve encore, ainsi qu’une ironie, le nom de la liberté, toute votre action et celle de votre clergé est entravée de jour en jour par des artifices nouveaux, en sorte qu’il n’est rien d’étonnant à ce que vous ne puissiez pas faire tout à la fois pour ramener les hommes de l’erreur et du vice, pour les retirer de leurs mauvaises habitudes, pour regreffer dans leurs esprits les notions du vrai et du droit, enfin, pour soulager l’Eglise de tant d’angoisses qui l’accablent.

Au

surplus, nous avons de quoi soutenir notre courage. Il vit, en effet, le

Seigneur, et il fera en sorte qu’à ceux qui aiment Dieu toutes choses

convergent en bien (41). Lui-même fera sortir le bien du mal, pour donner à

l’Eglise des triomphes d’autant plus splendides que l’humaine perversité se sera

obstinée avec plus d’opiniâtreté à ruiner son œuvre ici-bas. Telle est

l’admirable grandeur des desseins de la divine Providence ; telles sont, dans

l’ordre actuel des choses, ses voies impénétrables (42), mes pensées ne sont

pas les vôtres et mes voies ne sont pas vos voies, dit le Seigneur (43), telles

sont ses voies et ses pensées, qu’il veut que l’Eglise, de jour en jour, se

rapproche davantage de la ressemblance du Christ et se réfère à son image, à

lui qui a souffert tant et de si grandes tortures, en sorte que, de quelque

manière, elle accomplisse ce qui manque aux souffrances du Christ (44). Et

c’est pourquoi cette loi divine a été donnée à l’Église qui milite ici, sur la

terre, qu’elle soit perpétuellement éprouvée par des luttes, par des épreuves

et des angoisses et qu’elle puisse, par ce mode de vie, à travers de nombreuses

tribulations, entrer dans le royaume de Dieu (45), et se réunir enfin, un jour,

à l’Église triomphante du Ciel.

Dans

cet esprit, Anselme ayant à expliquer ce passage de saint Mathieu:

Jésus obligea ses disciples à monter dans la petite barque, s’exprime ainsi,

d’après le sens mystique : « l’Evangile décrit ici sommairement la condition de

l’Eglise depuis l’avènement du Sauveur jusqu’à la fin du siècle. La barque donc

était ballottée par les flots au milieu de la mer, tandis que Jésus s’attardait

sur le sommet de la montagne, parce que, du moment où le Sauveur est monté au

Ciel, la sainte Eglise a commencé d’être agitée dans ce monde par de grandes

tribulations, d’être secouée en tous sens par toutes sortes de tempêtes qui

sont celles des persécutions, d’être éprouvée par toutes sortes de vexations

que lui inflige la méchanceté des hommes pervers, et d’être, en mille manières,

assaillie par les vices humains. Car le vent lui était contraire, en ce sens

que le souffle des esprits malins doit s’exercer toujours contre elle pour

l’empêcher de parvenir au port du salut, et que le même souffle s’efforce de

l’engloutir sous le flot des adversités, en soulevant contre elle tous les

obstacles possibles (46). »

C’est donc bien profondément qu’ils se trompent ceux qui s’imaginent que la condition de l’Eglise peut être exempte de toutes ces perturbations et qui espèrent pour elle un état dans lequel, les choses allant à volonté, et rien ne s’opposant ni à l’autorité, ni au gouvernement de la puissance sacrée, il serait possible de jouir d’une tranquillité douce au cœur. Ils se trompent aussi d’ailleurs plus grossièrement que ceux-là, ceux qui, poussés par une fausse et vaine espérance de procurer une pareille paix, dissimulent les devoirs et les droits de l’Eglise, les font passer après les considérations privées, les atténuent, les diminuent injustement aux yeux du monde tout entier soumis au Malin (47), et s’arrangent avec celui-ci, sous le spécieux prétexte de s’attirer les sympathies des fauteurs de nouveautés qu’ils comptent réconcilier avec l’Église, comme si, entre la lumière et les ténèbres et entre le Christ et Bélial, il pouvait y avoir accord. Ce sont là des rêveries de malades, telles qu’on en a toujours aussi vainement caressées et qu’on en caressera encore, tant qu’il y aura de lâches soldats prêts à fuir en jetant leurs armes aussitôt qu’ils voient l’ennemi, ou des traîtres toujours hâtés de traiter avec l’adversaire, c’est-à-dire, dans notre cas, avec l’ennemi acharné et de Dieu et du genre humain.

Il est donc de votre devoir, Vénérables Frères, vous que la divine Providence a

constitués les pasteurs et les chefs du peuple chrétien, de tâcher, selon vos

forces, que notre âge, si enclin à ce genre de bassesse, cesse dorénavant alors

qu’une guerre si cruelle sévit contre la religion de s’endormir dans une

honteuse apathie, d’être neutre entre les deux camps, de pervertir les droits

divin et humain par de compromettants accommodements, mais retienne, au

contraire, profondément gravée au cœur de tous, cette sentence si formelle et

si précise du Christ : « Celui qui n’est pas avec moi est contre moi (48). » Ce

n’est pas qu’il ne faille que les ministres du Christ soient toujours pleins

d’une charité paternelle, eux à qui, entre tous, s’adressent les paroles de

Paul : « Je me suis fait tout à tous pour les sauver tous (49) » ; ce n’est pas

non plus qu’il ne convienne jamais de céder quelque chose, même de son droit, en

tant que cela est permis et utile au salut des âmes ; mais, certes, nul soupçon

d’une faute de ce genre ne tombe sur vous, que presse la charité du Christ.

Aussi bien, cette condescendance, qui a quelque chose d’équitable, ne mérite en

aucune façon le reproche d’être une restriction du Devoir, et elle ne touche en

rien du tout au fondement éternel de la Vérité et de la Justice. Il en a été

ainsi, d’après ce que nous dit l’histoire, dans la cause d’Anselme ou

plutôt dans la cause de Dieu et de l’Eglise pour laquelle, pendant si

longtemps, Anselme eut à lutter si âprement. Aussi, lorsque fut

apaisé enfin le long conflit; notre prédécesseur Pascal, déjà souvent nommé,

rendit hommage au saint évêque par ces paroles : « Que la miséricorde divine

ait pris enfin pitié de ce peuple sur qui veille sa sollicitude, nous croyons

que cette grâce a été obtenue par la charité pastorale et par l’instance de tes

prières. » Ce même Souverain Pontife, parlant de l’indulgence de père avec

laquelle il accueillait ceux qui s’étaient rendus coupables, usait des termes

suivants : « Si nous avons été aussi condescendant, ça l’a été, sache-le, afin

de pouvoir relever par l’effet de cette compassion affectueuse ceux qui étaient

tombés. Car, celui qui, étant debout, tend la main, pour le relever, à

quelqu’un qui gît devant lui, ne pourra pas le relever, s’il ne se courbe pas

lui-même. D’ailleurs, quoique l’inclination du corps puisse sembler proche de

la chute, il ne fait pas perdre pourtant l’équilibre à qui est debout (50). »

En nous appliquant à nous-mêmes ces paroles dites par notre pieux prédécesseur

à saint Anselme pour lui être une consolation, nous ne voulons pas,

néanmoins, dissimuler les douloureuses angoisses d’âme par lesquelles les

meilleurs même d’entre les pasteurs ont parfois à passer lorsqu’ils se

demandent, hésitants, s’il faut, de deux choses l’une, agir avec plus de

douceur ou résister avec une fermeté plus constante. De la douleur de ces

angoisses, on peut citer en témoignage les craintes, les tremblements, les larmes

de très saints hommes, des plus saints hommes, qui avaient le mieux éprouvé

combien est lourde la charge du gouvernement des âmes et combien en est grand

le danger pour ceux qui l’assument. La vie de saint Anselme en

fournit un clair témoignage. Appelé aux plus hautes fonctions, à une époque

très difficile, du fond d’une agréable retraite où il vaquait en paix à l’étude

et à la prière, il eut à traverser les plus pénibles des épreuves; et, tandis

qu’il était harcelé par tant de soucis, il ne craignait rien tant que de

n’avoir pas assez fait pour pourvoir au salut de son peuple et au sien, à

l’honneur de Dieu et à la dignité de l’Eglise. Rien ne relevait tant son âme

aux prises avec ces préoccupations, son âme brisée, endolorie, comme écrasée

par le fait de la défection d’un grand nombre de ses amis parmi lesquels

plusieurs évêques, rien ne consolait tant son âme que d’avoir placé sa

confiance dans le secours de Dieu et d’avoir cherché un refuge dans le sein de

la sainte Eglise. C’est pourquoi, sur le point de faire naufrage, et devant

l’assaut des tempêtes, il fuyait, écrit-il, « vers le port de la mère Eglise,

demandant au Pontife romain un pieux et prompt secours et une consolation »

(51).

C’est

peut-être par une permission divine qu’un homme d’une sagesse et d’une sainteté

aussi singulière fut exposé à tant d’adversité. C’est par toutes les épreuves

qu’il a eu à subir qu’il a pu nous être un exemple et un soutien à nous tous

qui peinons dans le saint ministère et que nous nous trouvons aux prises avec

les pires difficultés, en sorte que chacun de nous peut sentir et vouloir ainsi

que sent et veut saint Paul : « Volontiers, je me glorifierai dans mes

infirmités afin qu’habite en moi la puissance du Christ. C’est pourquoi je me

plais dans mes infirmités, car c’est quand je me sens infirme que je suis fort

(52).» Ce qu’écrit saint Anselme à Urbain II n’est pas sans ressembler à

ces paroles de l’apôtre : « Saint-Père, lui dit-il, je souffre d’être ce que je

suis, je souffre de n’être plus ce que j’ai été. J’ai douleur d’être évêque,

parce que, mes péchés l’empêchant je ne m’acquitte pas de mon devoir d’évêque.

En lieu humble, je paraissais faire quelque chose ; placé en haut, écrasé sous

une charge trop lourde, je ne fais aucun fruit pour moi, ni ne suis utile à

personne. Je succombe au fardeau, parce que, plus qu’il ne semblerait croyable,

je souffre d’être dépourvu des forces, des vertus, du génie et de la science

qu’exigent de si hautes fonctions. J’ai le désir de fuir un office que je ne

puis remplir, de me décharger d’un poids que je ne puis porter ; d’autre part,

j’ai la crainte, en le faisant, d’offenser Dieu : c’est la crainte de Dieu qui

m’a forcé à accepter cette fonction ; c’est la même crainte aujourd’hui qui me

contraint à la garder. Maintenant que la volonté de Dieu m’est cachée et que je

ne sais pas quoi faire, je vais errant et soupirant et j’ignore la fin qu’il

faut donner à ce tourment (53). »

Il plaît à la Bonté divine de ne pas laisser ignorer

aux hommes, même d’une sainteté éminente, quelle est leur faiblesse naturelle.

Ainsi, s’ils accomplissent quelque chose de grand, tous tiendront pour certain

que c’est à la force d’en haut qu’il convient de l’attribuer. Ainsi encore, les

hommes sont amenés à suivre avec humilité, et d’un effort plus généreux,

l’autorité de l’Eglise. C’est ce qui arriva pour Anselme et d’autres évêques

qui, sous la conduite du Saint-Siège, combattirent pour la liberté et pour la

doctrine de l’Eglise. Et leur obéissance leur a valu ce fruit, qu’ils sont

sortis vainqueurs de la lutte, ayant, par leur exemple, confirmé la divine

parole : « L’homme qui obéit parlera de victoire » (54). Une très grande

espérance d’obtenir pareille récompense brille aux yeux de tous ceux qui, d’une

âme sincère, obéissent à celui qui représente le Christ, en toutes les choses

qui se rapportent à la direction des âmes ou à l’administration de la

chrétienté, ou qui, d’une façon quelconque, ont rapport à ces grandes fins ;

car de l’autorité du Siège apostolique dépendent les directions et les conseils

des fils de l’Eglise (55).

Combien saint Anselme excella dans ce genre de gloire ! Avec quelle ardeur,

avec quelle fidélité, il se retint toujours uni avec le siège de Pierre, on

peut le conclure de ce qu’il écrivait au même pontife Pascal : « De nombreuses

et de très graves tribulations de mon cœur, connues de Dieu seul et de moi,

attestent le soin avec lequel mon âme observe, selon ses forces, le respect et

l’obéissance au siège apostolique. J’espère, en Dieu, que rien ne pourra m’arracher

à cette disposition. C’est pourquoi, pour autant qu’il m’est possible, je veux

remettre tous mes actes à la disposition de cette autorité afin qu’elle les

dirige et, si besoin est, les corrige (56). »

Toutes les actions et tous les écrits d’Anselme, et surtout ses lettres

privées, d’une suavité si grande, que notre prédécesseur Pascal disait avoir

été écrites par la plume de la Charité (57), témoignent identiquement de cette

volonté très ferme du saint homme. Dans ces lettres, il ne fait que demander et

qu’implorer de l’aide et de la consolation (58) : il promet d’adresser à Dieu,

pour le Pape, d’incessantes prières, comme lorsque, étant encore abbé du Bec,

il écrivait à Urbain II en ces termes si expressifs d’amour filial : « Nous ne

cessons de prier Dieu assidûment pour notre tribulations et celle de l’Eglise

romaine qui est la nôtre et celle de tous les vrais fidèles. Nous le prions

d’adoucir pour vous l’épreuve de ces jours mauvais, jusqu’à ce qu’enfin soit

creusée la fosse de ceux qui vous offensent. Et nous sommes sûrs, encore que le

Seigneur nous paraisse tarder beaucoup, qu’il ne laissera pas le fléau des

pécheurs peser sur le sort de ses justes, car il n’abandonnera pas son héritage

et les puissances de l’Enfer ne prévaudront pas contre lui (59).

Ce qui fait, Vénérables Frères, que nous nous délectons merveilleusement dans

la lecture de ces lettres et d’autres de ce genre écrites par Anselme, ce n’est

pas seulement qu’elles sont un témoignage à la mémoire d’un homme tel qu’on

n’en vit jamais de plus attaché au Saint-Siège ; c’est aussi qu’elles nous

rappellent les innombrables écrits et les actes de toute espèce par lesquels,

au milieu d’un conflit analogue, vous avez affirmé une union de volonté si

profonde et si explicite avec nous.

Il est admirable, vraiment, qu’au milieu des fureurs qui, au long cours des

siècles, sévissent orageusement contre le nom chrétien, l’union des Pontifes

sacrés et du troupeau fidèle n’ait cessé de se resserrer avec cette force et cette

vigueur autour du Pontife Romain. Cette union, de nos jours, s’est tellement

accrue encore et se montre avec une telle intensité qu’il semble que ce soit un

miracle de Dieu que des volontés d’hommes puissent s’unir avec une telle force

et, dans cette union, grandir dans une telle unité.

Cette conspiration d’amour et de fidélité, tandis qu’elle nous encourage et, à

la lettre, nous confirme, est, pour l’Eglise, une gloire et un soutien des plus

puissants. Mais, plus éclatant est le bien que nous vaut cette union, plus

aussi s’enfle contre nous l’envie de l’antique Serpent, et plus violentes sont

les rages qui coalisent contre nous les hommes impies, que la nouveauté d’un

tel fait frappe d’une sorte d’épouvante. Rien de semblable, il faut le dire, ne

s’offre à leur admiration dans les autres groupements d’hommes ; et ils ne

peuvent expliquer un tel fait par aucune des causes, soit publiques soit

autres, qui régissent les choses humaines ; mais ils ne s’avouent pas à

eux-mêmes que la sublime prière du Christ, dans le dernier repas qu’il prit

avec ses disciples, s’accomplit par cet événement.