Bienheureux Jerzy

Popieluszko

Prêtre et

martyr (+ 1984)

- 19

octobre 2019, la Pologne célèbre la mémoire du père Popieluszko, 35éme

anniversaire de son décès, Vatican News...

...Le prêtre

polonais Jerzy

Popieluszko (1947-1984), assassiné à 37 ans, fut notamment l'aumônier des

ouvriers du syndicat 'Solidarnosc' à Varsovie. Reconnu martyr par le pape

Benoît XVI, il a été béatifié le 6 juin 2010 à Varsovie...

Le

prêtre polonais Jerzy Popieluszko reconnu martyr par le pape Benoît XVI

...En août 1980, pendant

la grève de Solidarité aux aciéries de Varsovie, le père Jerry Popieluszko

devient, à la demande des sidérurgistes et par nomination du primat Wyszynski,

aumônier des ouvriers. Il s'engage profondément dans la pastorale des

travailleurs et accompagne le syndicat Solidarité pendant l'état de guerre.

C'est à partir de janvier 1982 que le dernier dimanche de chaque mois, le père

Jerzy Popieluszko célèbre des messes à l'intention de sa patrie. Ces messes

regroupent des milliers de fidèles venant de Varsovie et de différentes régions

de Pologne, devant des hommes à la recherche de la vérité, de liberté et de

justice, assoiffés d'amour et de paix.

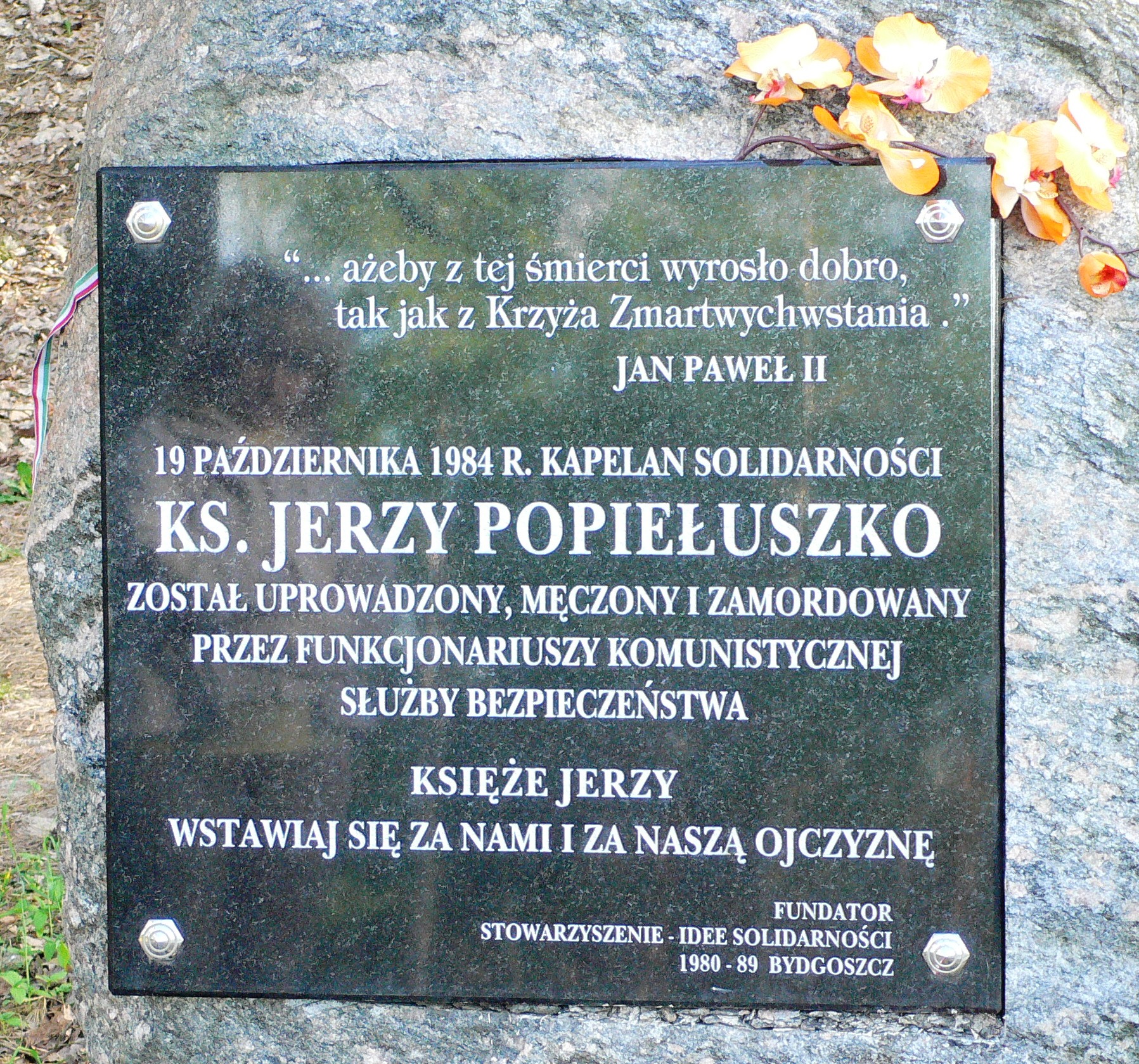

C'est le 19 octobre 1984

que le père Jerzy Popieluszko est attaqué alors qu'il revient en voiture de son

service pastoral à Bydgoszcz. Torturé, il est ensuite jeté dans la Vistule,

près de la ville de Wloclawek...

...Son ministère zélé et

son martyre sont un signe éloquent de la victoire du bien sur le mal. Puissent

son exemple et son intercession nourrir le zèle des prêtres et faire naître la

foi dans l'amour... (Benoît XVI - angelus

du 6 juin 2010 )

...Il a exercé son

ministère généreux et courageux aux côtés de ceux qui s'engageaient pour la

liberté, pour la défense de la vie et sa dignité. Son œuvre au service du bien

et de la vérité était un signe de contradiction pour le régime qui gouvernait

alors en Pologne. L'amour du Cœur du Christ l'a conduit à donner sa vie, et son

témoignage a été la semence d'un nouveau printemps dans l'Eglise et dans la

société... (Benoît XVI - angelus

du 13 juin 2010)

...L'Abbé Jerzy

Popieluszko, cruellement assassiné en 1984, devint aussi un symbole dans le

même sens, lui que l'on considère souvent comme le protecteur spirituel du

monde du travail polonais... (Jean-Paul

II au corps diplomatique le 8 juin 1991)

...Assassiné en 1984 à 37

ans, le prêtre polonais Jerzy Popieluszko, a été l'aumônier du syndicat

Solidarność. Béatifié en juin 2010 par Benoît XVI, on célèbre le 19 octobre

2014 les 30 ans de sa mort. Joanna, 30 ans, polonaise, dans l'équipe

'traduction' pour la préparation des JMJ de Cracovie en 2016, nous explique l'importance

de cette figure pour elle et pour les Polonais. (Le

p. Popieluszko, les JMJ et les Polonais)

- Une

guérison présumée miraculeuse attribuée au P. Popieluszko, site portail de

l'Eglise catholique en France, 21 novembre 2014.

« Vaincre avec le bien »

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/12617/Bienheureux-Jerzy-Popieluszko.html

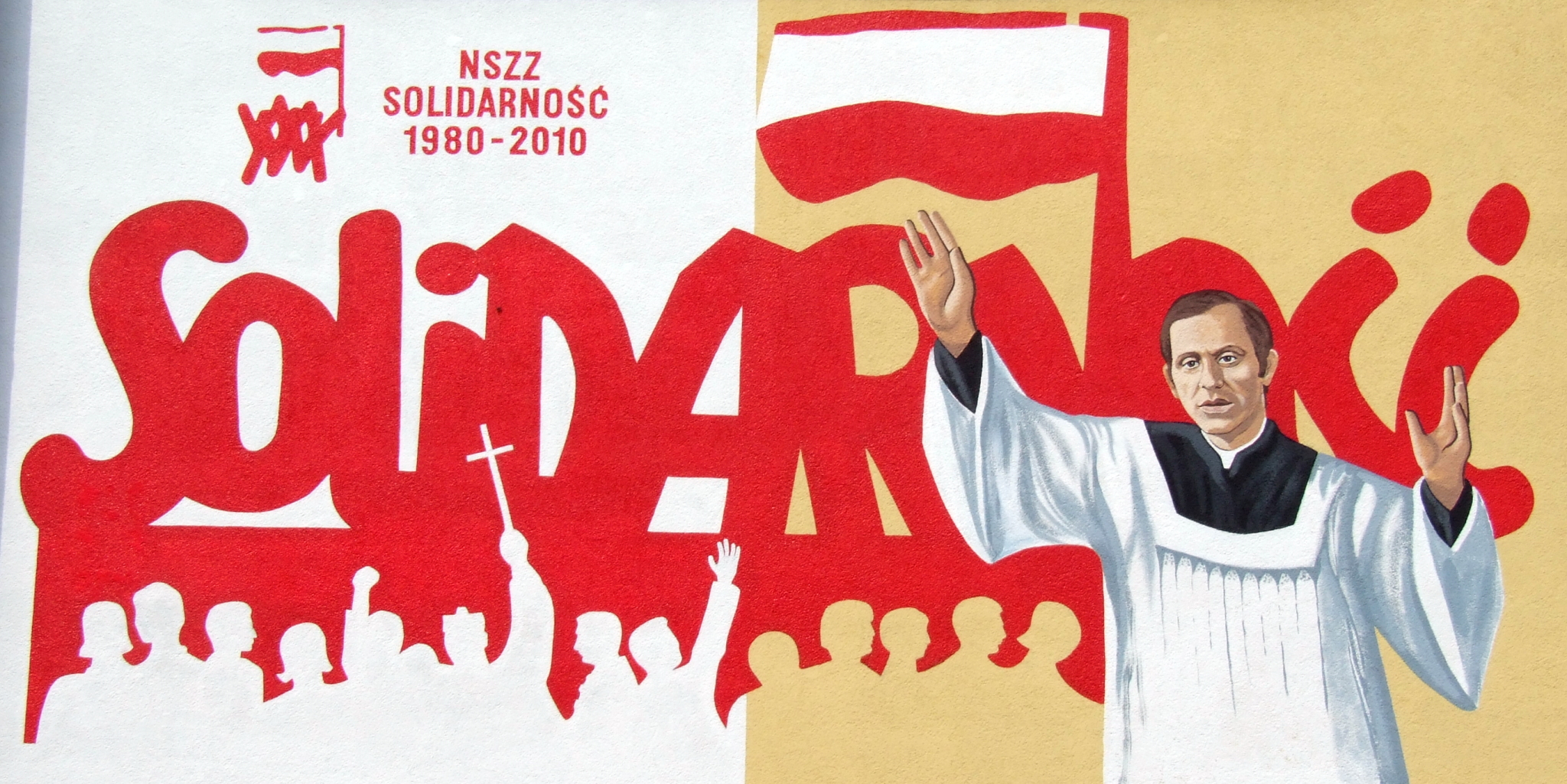

Jerzego Popiełuszki, znajdujący się na budynku

lokalnej siedziby związku w Ostrowcu Świętokrzyskim

30-years of Solidarity (Polish trade union) mural in Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski (priest Jerzy Popiełuszko in foreground)

Jerzego Popiełuszki, znajdujący się na budynku

lokalnej siedziby związku w Ostrowcu Świętokrzyskim

30-years

of Solidarity (Polish trade union) mural in Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski (priest Jerzy Popiełuszko in foreground)

Le 19 octobre :

Bienheureux Jerzy Popieluszko (1947 - 1984)

En août 1980, pendant la

grève de Solidarité aux aciéries de Varsovie, le père Jerry Popieluszko

devient, à la demande des sidérurgistes et par nomination du primat Wyszynski,

aumônier des ouvriers. Il s'engage profondément dans la pastorale des travailleurs

et accompagne le syndicat Solidarité pendant l'état de guerre. C'est à partir

de janvier 1982 que le dernier dimanche de chaque mois, le père Jerzy

Popieluszko célèbre des messes à l'intention de sa patrie. Ces messes

regroupent des milliers de fidèles venant de Varsovie et de différentes régions

de Pologne, devant des hommes à la recherche de la vérité, de liberté et de

justice, assoiffés d'amour et de paix.

C'est le 19 octobre 1984

que le père Jerzy Popieluszko est attaqué alors qu'il revient en voiture de son

service pastoral à Bydgoszcz. Torturé, il est ensuite jeté dans la Vistule,

près de la ville de Wloclawek.

Prière

Prions pour les prêtres

des pays où les chrétiens sont opprimés et persécutés. Que le

Seigneur leur donne la force d'encourager leurs fidèles à toujours plus de foi.

Soyons nous-mêmes des

exemples pour nos frères, invitons-les à plus de foi et d'espérance.

SOURCE : https://hozana.org/publication/98978-le-19-octobre-bienheureux-jerzy-popieluszko

Jerzy Popieluszko

Béatifié Dimanche !

Le prêtre polonais

Jerzy Popieluszko (1947-1984), assassiné à 37 ans, fut notamment l'aumônier des

ouvriers du syndicat « Solidarnosc » à Varsovie.

Reconnu martyr par

le Pape Benoît XVI en décembre dernier, il sera Béatifié le 6 Juin 2010 à

Varsovie.

Vingt-six ans déjà que le

Père Jerzy Popieluszko était jeté dans la Vistule après avoir été torturé à mort.

Elément gênant pour le

régime dictatorial, ce jeune prêtre de

trente sept ans, ami de Lech Walesa et proche de Jean-Paul II était devenu

insupportable en raison de sa popularité.

On peut faire taire un

homme. On n'aliène pas sa conscience. On peut canaliser le pouvoir temporel

d'une Eglise. On ne maîtrise pas le rayonnement de ses martyrs.

La Pologne fête, ce 6

Juin 2010, une de ses grandes figures nationales, en pleine Célébration de la

Fête Dieu, dévotion particulière pour ce prédicateur qui remuait les foules.

Sur décision de Benoît

XVI, l'Église Catholique célèbre sa Béatification à Varsovie. Les Catholiques

de l'Église en France expriment leur sentiment de fraternité à la communauté

Polonaise.

Mgr Bernard Podvin

Porte-parole de la Conférence

des évêques de France

Le Prêtre polonais Jerzy

Popieluszko reconnu Martyr par le Pape

Le Pape Benoît XVI a

autorisé samedi 19 Décembre la publication des décrets concernant le martyre du

Père Jerzy Popieluszko.

Né Alphonse Popieluszko

le 14 Septembre 1947, le Père Jerzy Popieluszko a été Baptisé dans l'église du

village d'Okopy, près de Suchowola.

Il a été élevé dans une

famille très Catholique, où la Prière était quotidienne et la fidélité à l'Evangile.

Entré au séminaire de

Varsovie, il effectue son service militaire de 1966 à 1968, où il est assigné à

la caserne de Bartosczyce, dans la zone frontalière nord-est du pays.

De santé fragile, le Père

Jerzy Popieluszko a particulièrement souffert des pressions exercées à l'encontre

des séminaristes.

Sous une Pologne

communiste, les séminaristes étaient en effet soumis à des pressions très

fortes : la Prière, en commun ou personnelle, à voix haute était interdite, de

même que le port des insignes religieux et la lecture de livres sur les sujets

religieux.

Le Père Jerzy Popieluszko

est ordonné prêtre le

28 Mai 1972 par le cardinal Stefan

Wyszynski.

Il exerce ses fonctions

pastorales en tant que vicaire de paroisses à

Zabki, à proximité de Varsovie, de 1972 à 1975, puis à Anin de 1975 à 1978, et

à Varsovie même, à la paroisse de

l'Enfant Jésus.

En 1979-1980, il assure

la catéchèse des

étudiants en médecine à l'église académique Sainte Anne à Varsovie.

Il est également nommé

membre du Corps consultatif national pour la pastorale du service de santé et,

sur le territoire de l'archidiocèse de Varsovie, aumônier diocésain du

personnel de santé.

A partir de Mai 1980, il

exerce son ministère dans

la paroisse Saint-Stanislas-Kostka

à Varsovie, où il dirige la pastorale spécialisée du personnel de santé.

Il organise des

rencontres religieuses de formation et de Prière pour les étudiants en

médecine, pour les infirmières des hôpitaux et pour les médecins.

En août 1980, pendant la

grève de Solidarité aux aciéries de Varsovie, le père Jerry Popieluszko

devient, à la demande des sidérurgistes et par nomination du primat Wyszynski,

aumônier des ouvriers.

Il s'engage profondément

dans la pastorale des travailleurs et accompagne le syndicat Solidarité pendant

l'état de guerre.

C'est à partir de Janvier

1982 que le dernier Dimanche de chaque mois, le père Jerzy Popieluszko célèbre

des messes à

l'intention de sa patrie.

Ces messes regroupent

des milliers de fidèles venant de Varsovie et de différentes régions de

Pologne, devant des hommes à la recherche de la vérité, de liberté et de

justice, assoiffés d'Amour et de Paix.

C'est le 19 Octobre 1984

que le Père Jerzy Popieluszko est attaqué alors qu'il revient en voiture de son

service pastoral à Bydgoszcz. Torturé, il est ensuite jeté dans la Vistule,

près de la ville de Wloclawek.

Les funérailles du Père

Jerzy Popieluszko furent Célébrées le 3 Novembre 1984 à Varsovie. Son corps

repose sur la terre de sa dernière paroisse,

Saint-Stanislas-Kostka à Varsovie.

D'après Nous voulons

Dieu, de Didier Rance, éd. Aide à l'église en détresse.

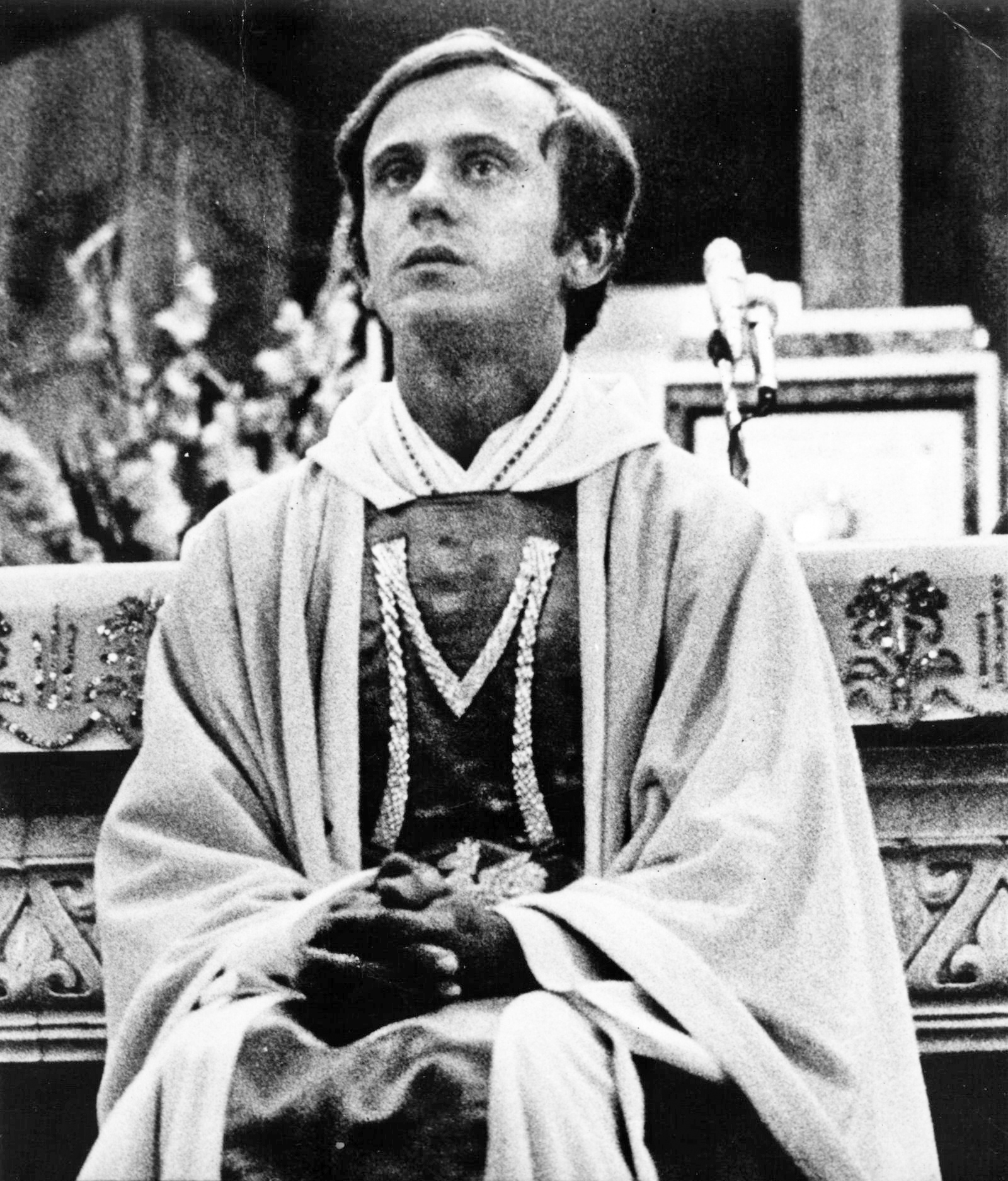

Jerzy Popiełuszko - zdjęcie z Europeany

i Cyfrowego Archiwum Pamiątek

Un miracle dans le

Val-de-Marne ouvre la voie à la Canonisation du Père Popieluszko

C'est ce samedi 20

Septembre 2014, lors d’une Messe Célébrée au Monastère de l’Annonciade à

Thiais, que Mgr Santier annonce l’ouverture de l’enquête pour la Canonisation

du Père Popieluszko.

"On est toujours

trop petit pour une telle grâce. Devant le passage de Dieu, on se sent

tout petit", confie Mgr Michel Santier, au

micro de Cyprien Viet, de Radio Vatican.

L'Évêque de Créteil ne

cache pas son émotion face à cette étonnante aventure spirituelle (lire

notre article à ce sujet), lui qui avait justement confié son diocèse à

l’intercession du Martyr polonais lors d’un voyage en Pologne, un an avant

cette guérison, le 14 Septembre 2012.

Ce samedi, lors d’une

Messe Célébrée au Monastère de l’Annonciade à Thiais, dans le département

français du Val-de-Marne, l’Évêque de Créteil annonce donc officiellement que

la Congrégation pour la cause des Saints a ouvert la procédure de Canonisation

du Père Jerzy Popieluszko.

Le monde entier se

souvient de ce Prêtre polonais, torturé et tué par la police politique

polonaise en 1984. Il était alors devenu l’icône de la résistance polonaise au

régime communiste.

Le Père Jerzy Popieluszko

avait été Béatifié en 2010 lors d’une Cérémonie organisée à Varsovie, à

laquelle avait assisté sa mère, décédée depuis.

" Il est déjà

béatifié, mais il n'y a pas eu besoin de miracle puisqu'il est

Martyr", explique Mgr Santier.

Mais il n'en va pas de

même pour la Canonisation. Et c’est justement une guérison aussi étonnante que

soudaine, qui pourrait bien être reconnue comme le miracle initiant la

procédure.

"La guérison s'est

passée dans le diocèse, à l'hôpital Albert-Chenevier, raconte l'Évêque de

Créteil.

La personne présumée

guérie souffrait d'un cancer. Les médecins avaient décidé d'arrêter le

traitement, et avaient dit à son épouse que c'était la fin. Elle avait déjà

pris contact avec les pompes funèbres."

Mais une Sœur polonaise

de l'aumônerie de l'hôpital l'a convaincue de faire appel à un

Prêtre. "Le Père Bernard Brien, qui venait tout juste d’être ordonné

Prêtre en « vocation tardive » était né le même jour que le martyr

polonais, le 14 Septembre 1947.

Il lui a donné le

Sacrement des malades, et a terminé en sortant une image du Père Popieluzko.

Il a prié, il s'est

adressé au Seigneur en disant "aujourd'hui c'est notre anniversaire. Il

faut que tu fasses quelque chose, c'est le moment d'intervenir."

L'épouse que j'ai reçu

m'a dit qu'aussitôt après, il avait ouvert les yeux. Le lendemain, la Sœur est

venue le visiter ; elle a vu qu'il n'était pas dans son lit, et a cru qu'il

était décédé. Puis elle a vu qu'il était debout et qu'il marchait.

Le rapport des médecins a

constaté qu'il n'y avait plus de cellules cancéreuses."

Il revient donc à

l’ordinaire du lieu, en l’occurrence l’Évêque de Créteil, d’annoncer

officiellement l’ouverture de l’enquête pour la Canonisation du Père

Popieluszko.

" La Sœur polonaise

était très heureuse, c'est elle qui a prévenu Varsovie, se souvient Mgr

Santier.

A la demande du Cardinal

Nisz, Archevêque de Varsovie, qui a prévenu la Congrégation des Saints, nous

allons ouvrir cette enquête ce samedi, en vue de la reconnaissance d'une

guérison miraculeuse mais présumée.

C'est la cause des Saints

qui instruira et la présentera au Pape, qui en définitive prend la décision.

Après, si cette guérison

est reconnue, cela initiera le processus de Canonisation du père

Popieluszko."

Découvrez

sur KTO un documentaire consacré à la vie du P. Jerzy Popieluszko

Statue

de Jerzy Popiełuszko, Sieradz, Pologne

Père Jerzy Popieluszko :

ultime étape vers la Canonisation

L’enquête (voir

ci-dessus) du diocèse de Créteil concernant une guérison attribuée à

l’intercession du Bienheureux Jerzy Popieluszko, a été envoyée à Rome ce Lundi

14 Septembre 2015.

C’est la fin d’une longue

et minutieuse enquête pour le diocèse de Créteil. Les conclusions de l’équipe

d’experts chargés d’étudier la guérison attribuée à l’intercession du bienheureux Père Jerzy

Popieluszko, devaient être envoyées à Rome ce lundi 14 septembre 2015.

Mgr Michel Santier,

Évêque du Val-de-Marne, annoncera officiellement la nouvelle au cours de la

Messe célébrée à la Cathédrale de Créteil ce même jour.

Une date symbolique, qui

commémore à la fois l’anniversaire de la naissance du Père Popieluszko et la

guérison inexpliquée de François A., un français âgé aujourd’hui de cinquante-huit

ans, hospitalisé à Créteil.

Le 14 Septembre 2012 en

effet, le Père Bernard Brien, un Prêtre du Val-de-Marne confie le patient

atteint d’une leucémie rare depuis plus de dix ans, à l’intercession du

Bienheureux. Le lendemain, François se lève de son lit, alors qu’il venait de

recevoir les derniers Sacrements. Quelques semaines plus tard, il est

totalement guéri de façon inexpliquée.

La Canonisation pourrait

être proche

Ce sont les détails de

cette guérison que les experts ont dû explorer durant plusieurs mois. L’enquête

doit désormais être approuvée par la Congrégation pour la cause des Saints,

pour que l’Église puisse officiellement décréter le caractère miraculeux de la

guérison.

Si celle-ci était

confirmée par Rome, le Père Popieluszko pourrait être Canonisé rapidement.

Ordonné Prêtre en 1972 en

Pologne, ce jeune Prêtre polonais fut l’aumônier du syndicat Solidarność

de Lech Walesa.

Après l’instauration de

la loi martiale par le général Jaruzelski en Décembre 1981, il aide les

militants du syndicat poursuivis et persécutés.

Vicaire à la paroisse

Saint-Stanislas de Varsovie, le Père Popieluszko célèbre des Messes qui

attirent des milliers de fidèles, venus de toute la Pologne.

Il dénonce inlassablement

la violence, invitant à « vaincre le mal par le bien ». Fiché parmi

les « Prêtres extrémistes », il est enlevé puis

assassiné en octobre 1984, à l’âge de 37 ans, par un commando de la police

du régime communiste.

Un Prêtre, exemple pour

la nouvelle évangélisation.

« Jerzy Popieluszko,

messager de la Vérité »

Anita Bourdin

ROME, Lundi 22 Octobre

2012 (ZENIT.org) – Le Bienheureux Prêtre polonais

Jerzy Popieluszko est un « exemple pour la nouvelle évangélisation »,

estime Mgr Eterovic.

Les pères synodaux et les

autres participants à la XIIIe assemblée générale ordinaire du synode des

évêques ont en effet été invités à la projection du film “Jerzy Popieluszko,

messager de la Vérité” à l’Institut Maria Bambina, près du Vatican, à mercredi

17 Octobre.

Des extraits du film sur

la vie du Bienheureux ont également été projetés au terme de la 15e

Congrégation générale du 17 Octobre en la salle du synode.

Le secrétaire général du

synode des Évêques, Mgr Nikola Eterovic, a qualifié la vie du Prêtre polonais

« d’exemple pour la nouvelle évangélisation ».

Le P. Jerzy Popieluszko (1947-1984) a été assassiné à 37 ans. Il était notamment l'aumônier des ouvriers du syndicat « Solidarnosc » à Varsovie.

Reconnu Martyr par le

Pape Benoît XVI en Décembre dernier, il a été Béatifié le 6 Juin 2010 à

Varsovie.

Lors de l’angélus du 13

Juin, 2010, Benoît XVI a évoqué le Martyr polonais en disant : « Il a

exercé son Ministère généreux et courageux aux côtés de ceux qui s'engageaient pour

la liberté, pour la défense de la vie et sa dignité. Son œuvre au service du

bien et de la vérité était un signe de contradiction pour le régime qui

gouvernait alors en Pologne. L'amour du Cœur du Christ l'a conduit à donner sa

vie, et son témoignage a été la semence d'un nouveau printemps dans l'Eglise et

dans la société ».

Le 6 Juin, le Pape avait

dit : « En Août 1980, pendant la grève de Solidarité aux aciéries de

Varsovie, le père Jerry Popieluszko devient, à la demande des sidérurgistes et

par nomination du primat Wyszynski, aumônier des ouvriers. Il s'engage

profondément dans la pastorale des travailleurs et accompagne le syndicat

Solidarité pendant l'état de guerre. C'est à partir de Janvier 1982 que le

dernier Dimanche de chaque mois, le Père Jerzy Popieluszko Célèbre des Messes à

l'intention de sa patrie. Ces Messes regroupent des milliers de fidèles venant

de Varsovie et de différentes régions de Pologne, devant des hommes à la

recherche de la vérité, de liberté et de justice, assoiffés d'amour et de paix.

C'est le 19 Octobre 1984 que le père Jerzy Popieluszko est attaqué alors qu'il

revient en voiture de son service pastoral à Bydgoszcz. Torturé, il est ensuite

jeté dans la Vistule, près de la ville de Wloclawek. Son Ministère zélé et son

Martyre sont un signe éloquent de la victoire du bien sur le mal. Puissent son

exemple et son intercession nourrir le zèle des Prêtres et faire naître la Foi

dans l’Amour ».

L'une des phrases les

plus célèbres du P. Popieluszko touche la proclamation de la Vérité :

« Le devoir du Chrétiens est de promouvoir la Vérité même si le prix est

très élevé. Parce que la Vérité se paie (...). Prions pour ne pas se laisser

intimider, pour être libérés de la peur et surtout du désir de la violence et

de la vengeance. »

Il a été assassiné le 19

Octobre 1984. L'Église célèbre sa Fête le 19 Octobre, jour de sa

« naissance au Ciel », son « dies natalis ».

Gdańsk, Plac Solidarności. Tablica - Jerzy Popiełuszko.

Bienheureux Jerzy

Popieluszko

Assassiné en 1984 à 37

ans, le prêtre polonais Jerzy Popieluszko, a été l'aumônier du syndicat

Solidarność. Il a été béatifié en juin 2010 par Benoît XVI. Il pourrait être

canonisé prochainement après un miracle intervenu en 2012 à Créteil.

Jerzy Popieluszko est né

en 1947 à Okopy, un petit village du nord-est de la Pologne, dans une famille

modeste de paysans. Il entre au séminaire à Varsovie, à l'âge de 18 ans.

Un prêtre engagé

Aumônier du

syndicat Solidarność de Lech Walesa, le père Popieluszko aide ses militants

poursuivis et persécutés après l'instauration de la loi martiale par le général

Jaruzelski en décembre 1981.

Vicaire à la paroisse Saint-Stanislas de Varsovie, le père Popieluszko célèbre des messes qui attirent des milliers de fidèles, venus des quatre coins de Pologne.

Dans ses homélies, le

père Popieluszko dénonce ouvertement la répression policière, la censure et les

persécutions des opposants au régime : "La violence n'est pas une

preuve de force, mais de faiblesse. Celui qui n'a pas su s'imposer par le cœur

ou par l'esprit, cherche à gagner par la violence«, disait-il en pleine loi

martiale. Son mot d'ordre : »vaincre le mal par le bien".

"En réclamant la vérité, nous devons la prêcher nous-mêmes. En réclamant la justice, nous devons être justes avec nos proches. En demandant le courage, nous devons nous-mêmes être courageux chaque jour", dira-t-il quelques mois avant sa mort.

Le père Popieluszko est

enlevé au retour d’une visite pastorale et assassiné en octobre 1984, à l'âge

de 37 ans, par un commando de la police du régime communiste.

Béatifié en 2010

Le procès en

béatification du père Jerzy Popieluszko a été ouvert en 1997 par le pape Jean

Paul II. Benoît XVI a évoqué la figure de père Jerzy Popieluszko lors de

l’Angélus du juin 2010 quelques jours après sa béatification : "Il a

exercé son ministère généreux et courageux aux côtés de ceux qui s'engageaient

pour la liberté, pour la défense de la vie et sa dignité. Son œuvre au service

du bien et de la vérité était un signe de contradiction pour le régime qui

gouvernait alors en Pologne. L'amour du Cœur du Christ l'a conduit à donner sa

vie, et son témoignage a été la semence d'un nouveau printemps dans l’Église et

dans la société."

Vers la canonisation

Le 14 septembre 2012, la

guérison d’un malade hospitalisé à Créteil relance le procès en canonisation du

Père Jerzy Popieluszko ouvert en Pologne. Une commission d’enquête composée de

deux notaires français et polonais, du délégué épiscopal pour la canonisation

de Jerzy Popieluszko et d'un spécialiste du droit canon, interroge de nombreux

témoins dont le père Brien.

Le Père Bernard Brien est

appelé le 14 septembre 2012 en urgence auprès d’un patient hospitalisé en soins

palliatifs à l’hôpital Chenevier de Créteil. Ce patient, atteint d'une leucémie

depuis 2001 est pratiquement dans le coma. Le père Brien lui administre le

sacrement des malades en présence de sa femme. Puis, il le confie à la prière

du Père Jerzy Popieluszko avec ces quelques mots : «Écoute Jerzy,

nous sommes le 14 septembre, c’est ton anniversaire et le mien, donc si tu dois

faire quelle chose pour notre frère François, c’est le jour !» Le

lendemain, le malade se porte bien à la stupéfaction de son entourage ; et

l’équipe médicale observe un recul net de la maladie. Après de nombreuses

analyses, les médecins constatent une guérison rapide, totale et inexpliquée du

cancer.

En son for intérieur, le

père Brien est persuadé qu’il s’agit d’un miracle, mais il garde le secret de

cette guérison car, dit-il «pour qu’un miracle soit reconnu, la guérison

doit être spontanée et totale, ce qui était le cas, mais elle doit aussi se

vérifier dans le temps. La patience s’imposait.» Il informe Mgr Santier de

la guérison en mai 2013 qui prévient le père Tomasz Kaczmarek, postulateur de

la cause du père Jerzy. Après de nombreuses discussions, Mgr Santier, à la

demande de l’archevêque de Varsovie, ouvre une enquête diocésaine. Celle-ci

aboutit en septembre 2015 à reconnaître l’authenticité du miracle.

Les conclusions de

l'enquête ont été envoyées à Rome à la Congrégation pour les causes des Saints

à Rome qui présentera le dossier au pape, seul habilité à décréter la

canonisation du père Jerzy Popieluszko.

Geneviève Pasquier

SOURCE : https://croire.la-croix.com/Definitions/Lexique/Saint/Bienheureux-Jerzy-Popieluszko

Jerzy Popiełuszko - meeting with

workers in Stocznia Gdańska, at the Gdańsk Shipyard

http://fbc.pionier.net.pl/zbiorki/dlibra/docmetadata?id=25

Andrzej

Iwański

Le Bienheureux Père Jerzy

Popiełuszko, martyr de la foi, a vaincu le mal par le bien.

La Pologne célébrait le

19 octobre dernier le 35ème anniversaire de la mort du bienheureux père

Jerzy Popiełuszko, martyr, combattant pour la vérité. Interview autour de cette

belle figure avec Joanna Chlebicka, en mission à Procida (Italie).

TdC : Peux-tu

présenter brièvement ce bienheureux si cher aux polonais ?

JCh : Jerzy (George)

Popiełuszko (1947-1984) est un prêtre et martyr Polonais. A l’époque de la

Pologne communiste, il raffermissait la société, enseignant à vaincre le mal

par le bien et offrant la souffrance de ses compatriotes sur l’autel

eucharistique. Les messes pour la patrie qu’il a célébré rassemblaient des

milliers de croyants de toute la Pologne. Elles étaient un oasis de liberté et

une communauté de prière intense. Le 19 octobre 1984, le père Jerzy fut enlevé

et sauvagement assassiné par les autorités communistes. Il avait 37 ans et 12

ans de sacerdoce. Il a été béatifié par le Pape Benoît XVI en 2010.

TdC : Il fut nommé

par l’épiscopat polonais comme aumônier du mouvement Solidarité. Pourquoi

une telle nomination, pourquoi ces personnes avaient-elles besoin d’un pasteur

? De quoi souffraient-elles et en quoi consistait sa mission ?

JCh : Le Père Jerzy

Popiełuszko était le pasteur de la communauté médicale (médecins, infirmières,

étudiants en médecine). Comme prêtre, il voulait être là où régnait la plus

grande souffrance. C’est ainsi que, d’une manière naturelle, un lien fort

s’établit entre lui et le monde des travailleurs. Il devint aumônier

de Solidarité parce que les ouvriers étaient le groupe le plus

nombreux et le plus vulnérable dans le système communiste. Le syndicat

indépendant Solidarité leur permettait de lutter ensemble pour des

conditions de travail et de vie décentes.

La société Polonaise

connut de vastes répressions, surtout après l’introduction de la loi martiale –

licenciement (dans un système où l’État était le seul employeur, il n’était pas

possible d’obtenir un nouvel emploi), emprisonnement et internement,

arrestation et torture, écoute clandestine, surveillance, interdiction des

rassemblements publics, censure, manque d’accès aux produits essentiels dans

les magasins. Telle était la réalité dans laquelle vivaient les Polonais. Le

père Jerzy croyait que le rôle du prêtre était de placer ces souffrances de la

nation sur l’autel de l’Eucharistie, les reliant au sacrifice du Christ.

TdC : Toute la

génération se souvient de la voix du bienheureux Jerzy Popiełuszko, qui

prêchait une fois par mois un sermon à la messe pour la patrie. De quoi

parlaient les sermons ?

JCh : Son

enseignement était très riche, mais le plus souvent il revenait à la question

de la vérité, la vérité, qui est le Christ, qui détermine la liberté et la

dignité inaliénable de tout être humain. Quelques phrases de lui sont restées

dans tous les esprits :

– Nous surmontons la peur

lorsque nous acceptons de souffrir ou de perdre quelque chose au nom de valeurs

supérieures. Si la vérité est une telle valeur pour nous, pour laquelle il vaut

la peine de souffrir, il vaut la peine de prendre un risque, alors nous

vaincrons la peur, qui est la cause directe de notre esclavage.

– Un homme qui témoigne

de la vérité est un homme libre, même dans des conditions d’esclavage

extérieur.

– Pour rester

spirituellement libre, il faut vivre dans la vérité (…). La vérité est

immuable. La vérité ne peut être détruite par une décision ou une autre, une

loi ou une autre.

– Seul peut vaincre le

mal celui qui seul est riche en bonté, qui prend soin du développement et de la

croissance en lui des valeurs qui font la dignité humaine d’un enfant de Dieu.

Multiplier le bien et vaincre le mal, c’est prendre soin de la dignité de

l’enfant de Dieu et de la dignité de sa propre personne.

L’homélie des messes pour

la patrie faisait une référence aux grands événements de la vie sociale (comme

la béatification de Maximilien Kolbe, les pèlerinages du pape Jean-Paul II en

Pologne, les anniversaires du soulèvement national au XIXe siècle). Les messes

elles-mêmes étaient mises en valeur par de nombreuses contributions des fidèles :

récitation de poésies, décoration de l’autel, beauté des chants. Le père Jerzy

appuyait souvent ses homélies sur les enseignements du cardinal Stefan

Wyszyński (dont la béatification aura lieu le 7 juin 2020) et du pape Jean-Paul

II.

TdC : Malgré son

énorme influence sur les Polonais de son temps, il était un homme très réservé

et timide.

JCh : Bien qu’issu

d’une famille simple et rurale, il avait une grande sensibilité artistique et

linguistique. Dans ses homélies, cependant, il utilisait un langage simple pour

les rendre compréhensibles de tous. Le père Jerzy était un homme très modeste.

Il était très attentif à chacun. Les gens lui présentaient leurs problèmes,

sachant qu’il ne resterait pas indifférent. C’était un homme en mauvaise santé

et un peu courbé, mais il portait sur ses épaules les problèmes de milliers de

personnes. Dans le même temps, il faisait lui-même l’objet d’une surveillance

exceptionnelle des services spéciaux – écoutes téléphoniques, espions dans le

voisinage immédiat, menaces et tentatives d’intimidation, surveillance

constante, provocations, convocations pour interrogatoires et arrestations. Son

entourage immédiat essayait bien de le protéger, mais tout le monde, y compris

lui, était conscient de la menace qui pesait sur sa vie. Le père Jerzy

considérait que le rôle du prêtre était de proclamer la vérité, de souffrir

pour la vérité, et s’il faut, donner sa vie pour elle.

TdC : Cette année,

l’Eglise Polonaise célèbre le 35ème anniversaire de sa mort, sa figure est-elle

encore importante pour les Polonais et les chrétiens de notre temps

?

JCh : Le père Jerzy

était un prêtre ardent, proche des gens et un grand patriote, c’est donc une

figure très importante pour la nation polonaise. Le culte du Père Jerzy

Popiełuszko ne se limite pas à la Pologne. Il y a déjà plus de 1400 reliques de

1er degré dans le monde, dont 400 hors des frontières de la Pologne, sur

différents continents. Son culte est encore en développement – le processus de

canonisation est en cours. Son enseignement sur la vérité est aussi valable à

l’époque du sécularisme universel qu’il ne l’était à l’époque du

communisme.

TdC : Vous avez

travaillé au Musée Popiełuszko, en quoi consistait ce travail? Quelle est votre

relation avec le Bienheureux ? Pouvez-vous partager quelques anecdotes

avec nos lecteurs ?

JCh : En 2011, le

Cardinal métropolitain de Varsovie, le Cardinal Nycz, a créé le « Centre

de Documentation de la Vie et du Culte du bienheureux père Jerzy Popiełuszko

« . Le siège du centre est situé dans l’appartement du Père Jerzy à la

paroisse St. Stanislas Kostka à Varsovie, où il a passé les dernières années de

sa vie. Le centre dispose d’une grande collection de documents, de

photographies, d’enregistrements audio et vidéo et de documents.

J’ai travaillé au centre

pendant 14 mois (aussi longtemps que durera ma mission avec Points-Cœur) pour

coordonner le projet de numérisation. Ce fut une grande grâce de travailler

dans l’appartement du Père Jerzy, apprenant à connaître les témoins de sa vie,

apercevant chaque jour de la fenêtre un groupe de pèlerins (du monde entier)

venu prier sur sa tombe et écoutant les témoignages sur les grâces reçues par

son intercession. Ils sont la preuve que le père Jerzy est un intercesseur très

efficace pour toutes sortes d’affaires. Le Père Jerzy continue à rassembler des

gens merveilleux autour de lui et cette relation étroite avec eux – dans un

esprit d’amour pour l’Eglise et la Patrie – fut une grande grâce pour

moi.

Propos recueillis par

Clément Imbert

Independence

March Warszawa 2019 /

Marsz

Niepodległości 2019. Warszawa, Rondo Dmowskiego.

Bienheureux Père

Popieluszko : « Écoute Jerzy, c’est le jour, fais-le ! »

ARTICLE | 06/11/2014 |

Numéro 1922 | Par Magali Michel

La guérison miraculeuse,

en 2012, de François Audelan, atteint d'une leucémie, est attribuée au Père

Popieluszko. Témoignage exclusif, en compagnie de son épouse Chantal et du Père

Bernard Brien.

Vous rentrez de Pologne

où vous avez participé à l’hommage rendu au Père Popieluszko trente ans après

sa mort. Quelles sont vos impressions ?

Chantal Audelan – Le

18 octobre, nous étions à Wloclawek, au barrage sur la Vistule, au lieu où le

Père Popieluszko a été jeté à l’eau après avoir été torturé. À cet endroit,

nous avons suivi ses reliques en procession en méditant le rosaire. Puis il y a

eu une messe en plein air, là où s’élève une basilique qui va devenir un

sanctuaire en son honneur. Cette messe a duré tout l’après-midi. La Pologne est

impressionnante de ferveur. On dirait que la foi lui coule dans les veines.

Rien qu’à Cracovie, on dénombre 440 paroisses, 1 170 prêtres, 964 religieux,

2 700 religieuses et 120 séminaristes. Le contraste est saisissant avec la

France.

Le Père Bernard

Brien – Le lendemain, une autre célébration à Varsovie a réuni une foule

venue de toute la Pologne. La présence du syndicat Solidarnosc y était très

forte.

François Audelan –

Il faut se rappeler ce qu’ont vécu ces gens et voir les documents d’époque. Ce

peuple a résisté à une pression folle. Dans les an-nées 80, nous avions des

supermarchés pléthoriques. Eux ne mangeaient pas à leur faim, ne pouvaient pas

parler, et souffraient pour la foi. Ils ont fait masse, ils ont fait corps. Le

Père Jerzy est un exemple parmi bien d’autres, il est loin d’être un cas isolé.

Et votre rencontre avec

la famille Popieluszko ?

C. A. – Nous avons

vu une famille très meurtrie. Mais tous lumineux. Ils sont encore marqués par

la mort du Père Jerzy et par les représailles qui ont suivi ses funérailles

historiques. Stanislas Popieluszko, son jeune frère, sanglotait aux

célébrations. Ils nous ont serrés chaleureusement dans leurs bras. À travers

François, nous avions l’impression qu’ils retrouvaient un petit souffle de leur

disparu.

Mon Père, comment vous

êtes-vous découvert jumeau du Père Popieluszko ?

B. B. – En juillet

2012, quatre mois après mon ordination, je suis parti sur les traces de

Jean-Paul II en Pologne. Durant ce pèlerinage, j’ai découvert dans la banlieue

de Varsovie le tombeau et la paroisse du Père Popieluszko. Attiré par ce

martyr, j’ai réalisé que nous étions nés le même jour, le même mois, la même

année. C’est au retour de ce voyage que j’ai été appelé au chevet de François,

le 14 septembre, jour anniversaire de la naissance du Père Jerzy et de la

mienne.

Retenu pour la

canonisation du bienheureux Popieluszko, un miracle s’est produit à Créteil le

14 septembre 2012. Que s’est-il passé ce jour-là ?

F. A. – En 2012,

j’ai 56 ans, une épouse, trois filles, un métier qui me passionne. On termine

de rembourser la maison de nos rêves. Mais depuis deux ans, je dégringole. Une

leucémie rare découverte onze ans plus tôt évolue à toute allure. Je reçois une

greffe de moelle osseuse en mai. Fin août, « il y a des métastases partout ».

Le scanner est sans appel. À ce stade, seuls des traitements de confort sont

préconisés. Le 11 septembre, j’entre en soins palliatifs à l’hôpital Albert-Chenevier

de Créteil.

C. A. – Dans le

couloir, Sœur Rozalia, une religieuse polonaise de l’aumônerie, me propose le

sacrement des malades pour mon mari. J’accepte volontiers connaissant la force

immense apportée par ce sacrement déjà reçu trois fois depuis que François est

malade.

B. B. – Le vendredi

14 septembre, appelé en début d’après-midi par cette même religieuse, je file à

Albert-Chenevier. Elle me conduit dans la chambre, où je vois un homme au

visage bouffi en phase terminale.

C. A. – Le Père Bernard

a posé sur la table de chevet une bougie, la croix de Jean-Paul II et l’image

d’un prêtre martyr polonais.

Une fois le sacrement donné, il nous propose de

confier François à l’intercession de ce jeune martyr du communisme.

L’image

du Père Jerzy en main, nous lisons la prière d’action de grâce. François est

somnolent.

B. B. – Arrivé à la

phrase « Accorde-moi par son intercession la grâce de… », je complète :

« Écoute Jerzy, c’est aujourd’hui le 14 septembre, c’est ton anniversaire et le

mien, si tu dois faire quelque chose pour notre frère François, c’est le jour,

fais-le ». Puis avec Sœur Rozalia, nous nous éclipsons. Je m’entends encore lui

dire que ça n’irait pas bien loin.

C. A. – La porte de

la chambre se referme, je suis assise à côté de François quand il ouvre les

yeux et me demande : « Que m’est-il arrivé ? » Ce sont ses premiers mots

cohérents depuis des semaines, mais je ne réalise pas. J’ai l’image d’un voile

qui se déchire. C’est tout. Le lendemain, je contacte deux sociétés de pompes funèbres.

B. B. – Le lendemain

à midi, le téléphone sonne. « Père Bernard ! Père Bernard ! C’est un

miracle ! » Au bout du fil, Sœur Rozalia est très excitée. En allant porter la

communion à François, elle trouve le lit vide. Elle croit à un décès survenu

pendant la nuit. Une infirmière la détrompe : il se douche…

F. A. – Du sacrement

des malades, je ne me rappelle rien. Je me souviens vaguement avoir demandé ce

qui m’arrivait avant de replonger. Je ne réalise pas que je suis guéri. La nuit

suivante, en revanche, en essayant de me lever à trois reprises, je découvre

que je ne tiens plus debout. Les jours suivants sont terribles quand je

comprends où je suis. Une psychologue me prépare à mourir. À aucun moment on ne

pense au miracle.

À partir de quand

avez-vous cru au miracle ?

C. A. – J’ai vu mon

mari sortir du tombeau comme Lazare. Ses bandelettes ont mis des mois à tomber.

Après la guérison du syndrome myélo-prolifératif, François a souffert de graves

séquelles oculaires, pulmonaires, rénales et dermatologiques. Durant des mois,

le Malin se déchaîne. Il fait tout pour brouiller la manifestation de la

guérison. Pourtant, en janvier 2013, « il n’y a plus rien du tout ». L’équipe

médicale du service d’hématologie clinique qui suit François depuis douze ans

constate qu’il est guéri. Le cancer a disparu. Cette rémission totale fait dire

au médecin chef : « Cas spectaculaire, voire miraculeux ». Ce jour-là, nous

savons que le Seigneur a totalement guéri François.

Comment les faits

sont-ils arrivés jusqu’à Rome ?

B. B. – Pour un

miracle, la guérison doit être totale et immédiate, mais elle doit aussi se

vérifier dans la durée. Nous sommes longtemps restés discrets. Lorsque la

rémission médicalement inexplicable a été attestée par plusieurs médecins, nous

avons été reçus par Mgr Michel Santier, notre évêque, informé à son tour.

Lui-même avait confié sa mission et son diocèse au bienheureux Popieluszko lors

d’un pèlerinage en Pologne un an plus tôt ! Ensuite, nous rencontrons le

postulateur, Mgr Tomasz Kaczmarek. Avéré par une commission diocésaine, le

miracle est retenu en mai 2014 par la Congrégation pour la cause des saints.

Père Brien, que vous

inspirent tous ces événements ?

B. B. – Dieu n’en

finit pas de montrer avec quelle miséricorde Il relève ceux qui tombent. J’ai

passé quarante ans sans fréquenter l’Église. Ce désert a duré de 16 à 56 ans.

Un an après la conversion radicale qui m’a ramené au Seigneur, j’ai entendu

l’appel au sacerdoce. C’était pendant une adoration. J’ai été ordonné à 65 ans.

À mon avis, « ses décisions sont insondables et ses chemins impénétrables »

(saint Paul).

François, comment

vivez-vous cette intervention extraordinaire ?

F. A. – Je me sens

tout petit devant une si grande grâce. Pourquoi moi ? Je suis habité par le

syndrome du survivant. Je suis sidéré. Que me dis-Tu, Seigneur ? Comment rendre

ce que j’ai reçu ?

Vous rendez témoignage au

corps et au sang du Christ.

F. A. – J’ai

toujours eu soif de l’eucharistie.

C. A. – À chaque

hospitalisation, François a reçu l’eucharistie tous les jours et même en

chambre stérile. Quelle grâce ! Douze ans plus tôt, quand nous avons découvert

la leucémie de François, je me souviens avoir reçu une image intérieure.

C’était au cours d’une messe, juste après avoir communié. Cette vision a été

notre force depuis. J’ai vu une veine dans laquelle coulait le sang de

François, chargé de son cancer, à l’extrémité, une hostie filtrait ce sang

malade. J’étais assurée que le corps du Christ serait force et salut pour nous.

Que retenez-vous du Père

Jerzy ?

C. A. – Sans se

lasser, il a proclamé que c’est par le bien qu’on peut vaincre le mal. J’aime

ses phrases : « Quel que soit ton métier, tu es un homme » ; « L’école ne peut

pas détruire les valeurs que la famille a semées dans l'âme des enfants » ;

« La sainteté est notre vocation et notre devoir ».

F. A. – Sa santé

précaire. Il avait une peur bleue du cancer du sang !

B. B. – Il est un

exemple de grande sensibilité envers les personnes souffrantes, déprimées,

perdues. Mgr Tomasz Kaczmarek rappelle aussi qu’il a été « un apôtre

inépuisable et un dispensateur de sacrement de la pénitence ». Ça me touche,

moi qui ai été ordonné le dimanche de la Divine Miséricorde.

Le bienheureux Père

Popieluszko

Béatifié en 2010, le

bienheureux Jerzy Popieluszko est désormais en lice pour la canonisation. Pour

être porté sur les autels, la reconnaissance d’un miracle suffit. C’est à quoi

travaille une commission annoncée et constituée, le 20 septembre, par Mgr

Michel Santier, évêque de Créteil. C’est en effet dans le Val-de-Marne qu’a eu

lieu le miracle retenu pour plaider le procès en canonisation du bienheureux

martyr polonais. Reste maintenant à prouver l’authenticité du miracle présumé.

Un tribunal constitué de

deux notaires, d’un promoteur de justice, d’experts médecins, d’un délégué

épiscopal et d’un président, s’y attelle. Depuis sa création, cette commission

d’enquête a déjà procédé à l’audition d’une partie des témoins du miracle. La

seconde audition se tiendra en décembre. En sus, deux médecins neutres

examineront François Audelan et tous les certificats médicaux fournis.

S’ensuivra un long travail de traduction en polonais, latin et italien des

pièces réunies. Après quoi, le dossier sera envoyé au postulateur, Mgr Tomasz

Kaczmarek, qui le transmettra à la Congrégation pour la cause des saints, à

Rome. Il faudra alors attendre que le pape François signe le décret. La

canonisation du bienheureux Popieluszko fait partie des événements très

attendus avec à l’horizon, également, les prochaines Journées mondiales de la

jeunesse prévues à Cracovie en 2016.

M. M.

Pomnik

Jerzego Popiełuszki w parku miejskim im. Ks. Jerzego Popiełuszki przy ul. Pl.

Kościuszki w Suchowoli, gmina Suchowola, podlaskie

Jerzy

Popiełuszko monument in Jerzy Popiełuszko town park by Pl. Kościuszki street in

Suchowola, gmina Suchowola, podlaskie, Poland

Jerzy Popieluszko

LE 19 OCTOBRE 1984 …..IL

Y A 25 ANS

"Mon cri était celui

de ma patrie"

Jerzy Popieluszko a eu le

courage de défendre les idéaux de vérité, de liberté et de justice".

"L'aumônier

charismatique de Solidarnosc a payé le prix suprême pour être resté fidèle à sa

vocation.

Il symbolise la grandeur

et la sainteté de l'homme, les valeurs que nous devons défendre toujours et

partout si nous voulons vivre dans un État libre et démocratique",

Le Père Jerzy

Popieluszko, actif défenseur du Syndicat Solidarité, est mort martyrisé le 19

octobre 1984, à l’âge de 37 ans, sous les coups de la police politique

polonaise. Jeune prêtre de Varsovie nommé aumônier des aciéries de Huta

Warszawa par le Cardinal Wyszynski, Il était alors un des jeunes prêtres

polonais les plus populaires. Les hommes de la police polonaise ont cherché à

enlever secrètement le Père Poieluszko, afin de le faire disparaître

mystérieusement. Ils espéraient pouvoir continuer leur macabre besogne sur

d’autres prêtres défenseurs de Solidarité, afin de créer un climat de terreur

en Pologne, dans la tradition des meilleures heures du stalinisme. Leur but

était de faire plier à la fois l’Église et le peuple polonais, dans un contexte

mêlé d’incertitude et d’angoisse. Mais en échappant à leurs mains, un homme à

réussi à casser la machine infernale des agents du terrorisme d’État. Cet homme

là était Waldemar Chrotowski, le chauffeur et l’ami du Père Popieluszko. Enlevé

en même temps que le Prêtre, il est parvenu à sauter en marche de la voiture

des policiers

Jerzy Popieluszko est né

le 14 Septembre 1947 à Okopy près de Suchowola en Podlasie. (nord-est de la

Pologne) Ses parents, Marianne et Ladislas, dirigeaient une exploitation

agricole.

A partir de 1961, Jerzy

étudie au Lycée à Suchowola. À l'école, les enseignants le définissent comme un

élève moyen, capable, mais ambitieux. Un individualiste. Dès son plus jeune âge

il est enfant de chœur. Cela dit, la vocation à la prêtrise, lui vint qu’a la

période du baccalauréat. Après son diplôme en 1965, il rejoint le Grand

Séminaire de Varsovie.

Au début de sa seconde

année d’étude, il est mobilisé dans l'armée.

Les années 1966 - 68 ont

étés consacrées au service militaire dans une unité spéciale pour les

séminaristes à Bartoszyce (Warminsko-mazurskie) Rappelons que le recrutement

des séminaristes dans l'armée (en dépit d'un accord entre l'État et l'Église en

1950) était une manière pour les autorités communistes de soustraire les jeunes

séminaristes de l’environnement des évêques récalcitrants de l'Église. Il était

prévu que par un astucieux système d'endoctrinement effectué par un personnel sélectionné,

et des officiers capables de persuader les séminaristes d’abandonner leurs

études cléricales .Jerzy Popieluszko fut un soldat distingué, d'un grand

courage défendant ses convictions, ce qui la conduit à subir diverses formes de

persécution.

En revenant de l'armée

Jerzy tomba malade. A partir de ce moment jusqu'à la fin de vie il aura à faire

face a des problèmes de santé.

Le 28 Mai, 1972, il est

ordonné, prêtre des mains du cardinal Stefan Wyszynski Primat de Pologne.

Les images distribuées

lors de sa première messe comportent la phrase suivante : «Dieu m'envoie, pour

prêcher l'Évangile et à panser les plaies des cœurs blessés."

Jerzy a vécu son

sacerdoce dans les paroisses suivantes : l'église St. Trinity Zabkach ; p.w.

Notre-Dame Reine de la Pologne à Aninie et p.w. L'enfant Jésus à Zoliborzu. Il

avait dans son ministère pastoral un penchant pour le travail avec les enfants

et les jeunes. Malheureusement, les problèmes de santé s'aggravent. En Janvier

1979, Jerzy s'évanouit pendant la célébration de la Messe Après quelques

semaines de séjour à l'hôpital il ne retourne pas son travail régulier de

vicaire

Pendant l'année scolaire

1979/80, il a officié à l’aumônerie de l'église universitaire. Sainte Anne. Il

organisé un séminaire pour les étudiants en médecine.

Fin 1978, il a été nommé

pasteur de l'équipe médicale. Depuis lors, chaque mois, il a célébré la messe à

la chapelle Saint Res Sacra Miser.

A partir du 20 Mai 1980,

il est à la paroisse St. Stanislas Kostka. En tant que responsable du ministère

du personnel médical, depuis août 1980 il s’est engagé dans des activités

pastorales auprès des travailleurs.

C’est en août 1980 que le

Cardinal Wyszynski, , lui a demandé d’être l’aumônier des aciéries de la

capitale. C’est ainsi que le jeune abbé Popieluszko est devenu un ardent

défenseur de l’idéal du syndicat de Solidarité, né à la même époque, lors des «

accords de Gdansk »

À. 10h00, chaque

dimanche, il a célébré la sainte messe pour eux. Il s'est entretenu avec eux

régulièrement, tous les mois. Il a organisé une sorte de «laboratoire» pour les

travailleurs. Il a dirigé leur catéchèse, mais aussi à travers une série de

conférences il veut les aider à acquérir des connaissances dans divers domaines

- l'histoire de la Pologne et de la littérature, de la doctrine sociale de

l'Église, droit, économie, et même les techniques de négociation En Octobre

1981, il fut nommé aumônier diocésain pour la santé et aumônier auprès de la

maison de santé des employés des services de santé dans la rue Elekcyjnej 37.

Chaque semaine, la messe sera célébrée. dans la chapelle, qu’il a en partie

aménagée

Après le coup d’État du

13 décembre 1981, il avait pris la défense du syndicat Solidarité, mis

brutalement hors-la-loi.

Tous les mois, depuis

cette date fatidique, le Père Popieluszko célébrait une « messe pour la patrie

» dans sa paroisse St Stanislas-Kotska, dans la banlieue de Varsovie. Il y

prononçait de vibrantes homélies pour la justice sociale et le respect de la

liberté de l’homme. Le texte de ses allocutions courageuses était enregistré

par de nombreux militants sociaux chrétiens de Solidarité, et diffusé par

cassettes à travers toute la Pologne. Autant dire que le jeune prêtre était

considéré comme un dangereux agitateur par les séides du régime communiste

polonais,

A l’automne 1983, une

liste de 69 « prêtres extrémistes » a été établie par le gouvernement du

Général Jaruzelski et remise au Cardinal Glemp, successeur de l’intrépide Mgr

Wyszynski. Prière était faite au nouveau Primat de Pologne de faire taire ces

gêneurs en soutane. Le Père Popielszko figurait en bonne place sur cette liste,

en compagnie, il est vrai, de deux évêques, Mgr Tokarczuk et Mgr Kraszewski,

auxiliaire de Varsovie, et du confesseur de Lech Walesa, l’ineffable Père

Jankowski.

Dès les 12 et 13 décembre

1983, l’Abbé Popieluszko a été placé en garde à vue pendant deux jours. La

police prétendait avoir découvert chez lui des armes et des explosifs, ainsi

que des tracts de Solidarité. Au cours de la nuit suivant sa garde a vue , il

échappa de justesse à un attentat, une grenade ayant explosé dans son vestibule

après qu’un inconnu eut sonné à sa porte. Accusé d’ « abus de sacerdoce », le

jeune prêtre fut convoqué treize fois par la milice, dans les quatre premiers

mois de l’année 1984. Le porte-parole du gouvernement communiste, Jerzy Urban,

aujourd’hui reconverti dans la presse pornographique et anticléricale,

qualifiait Jerzy Popieluszjo de « fanatique politique ». Le vendredi 19

octobre à 22 heures, trois officiers de police arrêtèrent la voiture du Père

Popieluszko en rase campagne, sous prétexte d’un contrôle d’alcooltest. Alors

que son chauffeur parvint à s’enfuir, le prêtre martyr resta entre leurs mains.

Pendant plusieurs jours,

aucune nouvelle ne fut donnée sur le sort du père Popieluszko, jusqu’à ce que

le 27 octobre, le capitaine Grzegorz Piotrowski déclare : « C’est moi

qui l’ai tué, de mes propres mains ».

Le corps de l’aumônier

fut retrouvé dans un lac artificiel formé par le barrage de Wloclawek, sur la

Wisla à une centaine de kilomètres au nord de Varsovie. La nouvelle eut un

impact impressionnant mais le peuple polonais y fit face sans céder à la colère

ou à la violence, se souvenant des paroles que le père Jerzy aimait

répéter : « Nous devons vaincre le mal par le bien ».

Le père Jerzy a

certainement pardonné à ses assassins et il aurait sans doute voulu qu’on ne

parle pas trop du procès de Torun, mais sachez simplement que ceux qui

ordonnèrent ce crime, raconté dans les moindres détails par les assassins, au

cours d’un procès dramatique, ne furent jamais jugés. Les accusés furent

condamnés, mais leur peine fut ensuite réduite. Tous sont déjà sortis depuis

bien longtemps de prison.

La tombe du père

Popieluszko, située à Varsovie près de l’église où il célébrait les messes pour

la patrie, est devenue un lieu de pèlerinage où se sont déjà rendues des

millions de personnes qui le vénèrent comme témoin de la résistance morale et

spirituelle du peuple polonais.

Le Martyre du Père

Popieluszko a entraîné de nombreuses conversions, et même l’éclosion de

vocations sacerdotales. Il a soudé davantage encore l’Église de Pologne et les

militants de Solidarités. Aux yeux de l’Église Universelle, il revêt la valeur

d’un témoignage suprême contre l’oppression du totalitarisme athée.

Le 31 octobre 1982, le

Père Pupieluszko déclarait : Pour rester un être libre intérieurement, il

faut vivre dans la vérité. La vie dans la vérité, c'est de témoigner autour de

soi, de reconnaître la vérité, la réclamer dans chaque situation. Nous ne

sommes pas directement persécutés, nous ne sommes pas menacés de mort.

Sommes-nous libres pour autant ? Le chemin de la liberté s'ouvre devant

celui qui témoigne avec courage, disait le Père Popieluszko. Il nous en faut,

du courage, pour témoigner de la vérité sur l'homme et sur la vie. La vérité ne

change pas, on ne peut pas la détruire par des décisions ou des lois. Deux ans

avant sa mort, il terminait ainsi un de ses sermons : Nous prions Dieu de nous

donner l'espérance, car seulement ceux qui sont forts par l'espérance sont

capables de surmonter toutes les difficultés.

Ryszard©

Gazet@ Beskid

Création et

réalisation Stéphane

Delrieu

SOURCE : http://www.beskid.com/popieluszko.html

Funeral

of Jerzy Popiełuszko at Saint Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw

Pogrzeb

księdza Jerzego Popiełuszki na terenie kościoła

św. Stanisława Kostki w Warszawie

Funeral

of Jerzy Popiełuszko at Saint Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw, 3

November 1984

Pogrzeb

księdza Jerzego Popiełuszki na terenie kościoła

św. Stanisława Kostki w Warszawie

Funeral

of Jerzy Popiełuszko at Saint Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw

Pogrzeb

księdza Jerzego Popiełuszki na terenie kościoła

św. Stanisława Kostki w Warszawie

Celebration

of memory of Jerzy Popiełuszko – altair

Bx Jerzy Popiełuszko

Prêtre et martyr

Jerzy Aleksander (au

baptême : Alfons) Popiełuszko naît le 14 septembre 1947 à Okopy, un petit

village de Voïvodine, au nord-est de Białystok (Pologne), au sein d’une famille

de paysans profondément chrétienne.

Entré au grand séminaire

de Varsovie en 1965, il a été appelé, un an plus tard, sous les drapeaux, pour

faire ses trois années de service militaire dans une unité spéciale. Les

autorités militaires procédaient à un endoctrinement anticlérical et

antireligieux pour détourner les séminaristes de leur vocation. Il fut l'objet

de vexations et de persécutions qui portèrent atteinte à sa santé.

Jerzy Popiełuszko fut

ordonné prêtre le 28 mai 1972 par le cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, primat de

Pologne, et choisit pour devise sacerdotale les paroles du prophète Isaïe et de

l'Évangile de Luc : « Il m'a envoyé porter la Bonne Nouvelle aux pauvres,

panser les plaies des cœurs brisés ».

Il exerça ses fonctions

pastorales en tant que vicaire de paroisses à Ząbki, à proximité de Varsovie,

puis à Anin, et enfin à Varsovie même, à la paroisse de l'Enfant Jésus.

En 1979-1980, il assura

la catéchèse des étudiants en médecine à l'église académique Sainte-Anne à

Varsovie. Il fut également nommé membre du Corps consultatif national pour la pastorale

du service de santé et aumônier diocésain du personnel de santé.

Dès mai 1980, il exerça

son ministère dans la paroisse Saint-Stanislas-Kostka à Varsovie.

En août 1980, pendant la

grève de Solidarność aux aciéries de Varsovie, le père Jerzy Popiełuszko

devient, à la demande des sidérurgistes et par nomination du primat Wyszyński,

aumônier des ouvriers. Il s'engage profondément dans la pastorale des

travailleurs et accompagne le syndicat Solidarność pendant l'état de guerre.

Après le coup de force du

général Wojciech Jaruzelski contre Solidarność en décembre 1981, le père

Popieluszko s'était mis à célébrer des « Messes pour la patrie », où

les homélies affrontaient des thèmes religieux et spirituels mais aussi des

questions d'actualité, à caractère social, politique et moral. Ces messes

regroupent des milliers de fidèles venant de Varsovie et de différentes régions

de Pologne, suscitant la fureur du pouvoir communiste.

Considéré comme «

dangereux », Jerzy Popiełuszko fut enlevé par trois officiers de la police

politique (SB) le 19 octobre 1984, alors qu'il revient en voiture de son

service pastoral. Après avoir été torturé jusqu'à ce que mort s'ensuive, le

corps est lesté puis jeté dans un réservoir d'eau de la Vistule (à 120 km au

nord de Varsovie). Son corps méconnaissable ne sera découvert, par des

plongeurs, que plusieurs jours plus tard dans ce réservoir, grâce aux aveux des

trois officiers. Ses funérailles, auxquelles participèrent plus de 1.000

prêtres et des centaines de milliers de fidèles, furent célébrées le 3 novembre

1984 à Varsovie.

Le père Popiełuszko

symbolise, aux yeux des Polonais, la lutte commune de l'opposition démocratique

et de l'Église catholique contre un régime totalitaire.

Jerzy Popiełuszko à

été béatifié le 6 juin 2010 par le card. Angelo Amato s.d.b., Préfet de la

Congrégation pour la cause des Saints, qui représentait le pape Benoît XVI.

La célébration, qui a eu

lieu en Pologne, à Varsovie, sur la place du Maréchal Józef Pilsudski,

réunissait des fidèles venus de tout le pays, les membres du syndicat «

Solidarność », les autorités civiles et militaires, les prêtres, les personnes

consacrées, la mère du bienheureux, Marianna Popiełuszko, et la famille du

prêtre martyr.

SOURCE : https://levangileauquotidien.org/FR/display-saint/a4d34830-d504-456c-bf40-976a2df114d0

Jerzy Popiełuszko - zdjęcie z Europeany

i Cyfrowego Archiwum Pamiątek

Profile

Born to a farm family. Ordained on 28 May 1972 in

the archdiocese of Warsaw, Poland.

Noted and vocal anti-Communist preacher during

the period of Communist rule

in Poland.

Worked closely with the anti-Communist Solidarity

union movement. When martial law was declared in Poland to

suppress opposition, the Church continued

to work against the Communists,

and Father Jerzy’s

sermons were broadcast on Radio Free Europe. The secret police threatened and

pressured him to stop, but he ignored them. They trumped up evidence and arrested him

in 1983,

but the Church hierarchy

indicated that they would fight the charges; the false charges were

dropped, Father Jerzy

was released, continued his work, and was pardoned in a general amnesty

of 22

July 1984.

The Communists tried

several times to kill him and make it look like an accident or anonymous

attack, but they quit hiding their intentions, and the secret police simply

kidnapped and killed Father Jerzy. Martyr.

Born

14

September 1947 in

Okopy, Podlaskie, Poland

kidnapped on 19

October 1984 by

the Sluzba Bezpieczenstwa (Security Service of the Ministry of Internal

Affairs), the Communist Polish secret

police

beaten

to death from 19 to 20

October 1984 near

Wloclawek, Pomorskie, Poland

body dumped in the

Vistula Water Reservoir where it was found on 30

October 1984

the murderers and their

supervisor, Grzegorz Piotrowski, Waldemar Chmielewski, Adam Pietruszka, and

Leszek Pêkala, were arrested, convicted of the crime, and received light

sentences

more than 250,000

attended Father Jerzy’s

funeral

buried at

Saint Kostka’s Church, Warsaw, Poland

the rock that struck

the killing blow

is enshrined at

Saint Bartholomew’s Basilica, Tiber Island, Rome, Italy

19

December 2009 by Pope Benedict

XVI (decree of martyrdom)

6 June 2010 by Pope Benedict

XVI

recognition to be

celebrated at Piłsudski Square, Warsaw, Poland,

presided by Archbishop Angelo

Amato

Additional

Information

books

Zenit: Process Begins to Recognize Miracle Attributed to

Prayer of Blessed Jerzy

images

video

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

strony

w jezyku polskim

Parafia p. w. Sw.

Stanislawa Kostki w Warszawie

MLA

Citation

“Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko“. CatholicSaints.Info.

10 July 2023. Web. 23 November 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-jerzy-popieluszko/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-jerzy-popieluszko/

Jerzy Popiełuszko in Gdańsk

http://fbc.pionier.net.pl/zbiorki/dlibra/docmetadata?id=25.

Andrzej Iwański

Polish priest, martyr and

hero: Remembering Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko

by Mary

Farrow

Warsaw, Poland, Oct 19,

2018 / 04:42 pm MT (CNA).-

When Communist officials kidnapped and killed Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, they

likely did not intend to help create a Polish hero, martyr and future saint for

the Catholic Church.

Although the Communists

had been trying to kill Popiełuszko in ways that would seem like an accident,

they captured him 34 years ago today, on Oct. 19, 1984. They beat him to death

and threw his body into a river. He was 37 years old.

His crimes: encouraging

peaceful resistance to Communism via the radio waves of Radio Free Europe, and

working as chaplain to the workers of the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement and

trade union, which was known for its opposition to Communism.

Popiełuszko was born on

Sept. 14, 1947 to a farming family in Okopy, a village in eastern Poland

bordering modern-day Ukraine. While World War II had ended, the regime of the

Communist Party had taken place of the Nazis and ruled Poland at the time.

As a young man,

Popiełuszko served his required time in the army before completing seminary

studies and becoming a priest for the Archdiocese of Warsaw. He was ordained on

May 28, 1972 at the age of 24.

As a priest in Warsaw,

Popiełuszko served in both regular and student parishes. He became known for

his steadfast, non-violent resistance to Communism, about which he spoke

frequently in his homilies, which were broadcast on Radio Free Europe.

Popiełuszko participated

in the Solidarity worker’s strike in Warsaw on March 27, 1981, a four-hour

national warning strike that essentially ground Poland to a halt, and was the

biggest strike in the history of the Soviet Bloc and in the history of Poland.

After this strikes, the

Communist party declared martial law until July 1983 in the country, severely

restricting the daily life of Poles in an effort to clamp down on their growing

political opposition.

During this time,

Popiełuszko celebrated monthly “Masses for the Homeland” on the last Sunday of

the month, advocating for human rights and peaceful resistance of Communism,

and attracting thousands of attendees. His Warsaw office had also become an

official hub for Solidarity activities.

It was also during this

time that Communist attacks against the priest escalated. In 1982, Communist

authorities attempted to bomb the priest’s home, but he escaped unharmed. In

1983, Popiełuszko was arrested on false charges by the Communist authorities,

but was released shortly thereafter following significant pressure from the

Polish people and the Catholic Church.

According to a 1990

article in the Washington Post, Cardinal Józef Glemp, Archbishop of Warsaw

at the time, received a secret message from the Polish Pope John Paul II,

demanding that Glemp defend Popiełuszko and advocate for his release.

"Defend Father Jerzy

- or they'll start finding weapons in the desk of every second bishop,"

the pope wrote.

But the Communist

officials did not relent. According to court testimony, in September 1984

Communist officials had decided that the priest needed to either be pushed from

a train, have a “beautiful traffic accident” or be tortured to death.

On October 13, 1984,

Popiełuszko managed to avoid a traffic accident set up to kill him. The back-up

plan, capture and torture, was carried out by Communist authorities on Oct. 19.

They lured the priest to them by pretending that their car had broken down on a

road along which the priest was travelling.

The captors reportedly

beat the priest with a rock until he died, and then tied his mangled body to

rocks and bags of sand and dumped it in a reservoir along the Vistula River.

His body was recovered on

Oct. 30, 1984.

His death grieved and

enraged Catholics and members of the Solidarity movement, who had hoped to

accomplish social change without violence.

“When the news was

announced at his parish church, his congregation was silent for a moment and

then began shrieking and weeping with grief,” the

BBC wrote of the priest’s death.

“The worst has happened.

Someone wanted to kill and he killed not only a man, not a Pole, not only a

priest. Someone wanted to kill the hope that it is possible to avoid violence

in Polish political life,” Solidarity leader Lech Walesa, a friend of

Popiełuszko, said at the time.

He also urged mourners to

remain calm and peaceful during the priest’s funeral, which drew more than a

quarter of a million people.

Again facing pressure

from the Church and the Polish people, Poland's president Gen. Wojciech

Jaruzelski was forced to answer for the priest’s death, and arrested Captain

Grzegorz Piotrowski, Leszek Pękala, Waldemar Chmielewski and Colonel Adam

Pietruszka as responsible for the murder.

“Our intelligence sources

in Poland do not believe it,” the Washington Post reported in 1990, when the

case was being revisited.

“Jaruzelski had presided

over a far-reaching anti-church campaign. At least two other priests died

mysteriously. And Jaruzelski created the climate that allowed the SB (Communist

secret service) to persecute and kill Father Jerzy.”

In 2009, Popiełuszko was

posthumously awarded the Order of the White Eagle, the highest civilian or

military decoration in Poland. That same year, he was declared a martyr of the

Catholic Church by Pope Benedict XVI, and on June 6, 2010 he was beatified. A

miracle in France through the intercession of Popiełuszko is being investigated

in France as the final step in his cause for canonization.

Popiełuszko is one of

more than 3,000 priests martyred in Poland under the Nazi and Communist regimes

which dominated the country from 1939-1989.

On Friday, Archbishop Stanisław Budzik of Poland and the Polish bishops’ conference released a statement honoring the memory of Father Popiełuszko and all the 20th century priest martyrs of Poland.

“Today, remembering Fr.

Jerzy Popiełuszko, we remember the unswerving priests who preached the Gospel,

served God and people in the most terrible times and had the courage not only

to suffer for the faith but to give what is most dear to men: their lives.”

Church of the Transfiguration in Sanok

stained glass window Jerzy Popiełuszko founded by Adam Sudoł

Kościół Przemienienia Pańskiego w

Sanoku. Witraż - ks. Jerzy Popiełuszko ufundowany przez ks. Adama Sudoła w 1994

The Touching Story of

Blessed Father Jerzy Popieluszko

MAR 1,

2019 ELEONORE VILLARRUBIA

This beloved and

unassuming young priest of Poland was a true hero of that tortured land during

the Soviet Communist occupation. Now a Blessed, Father Jerzy (pronounced

YEH-Zhe) was beloved by everyone in his homeland, believers and non-believers

alike, because of his bravery in the face of extreme hatred on the part of the

Communist officials. His story should be much more widely known than it is.

Never in good health, the

strongest part of Father Jerzy were his hands. His most beloved possessions

were the crucifix and Rosary sent to him by Pope John Paul II, a fellow

countryman. He was sickly his whole life, yet he never complained of illness or

injury. One day when he was making toys with his brothers and sisters, a nail

pierced his palm. Later, one of the children noticed blood dripping from his

hand. One of his siblings told the parents because young Jerzy did not want to

bother anyone.

Young Jerzy’s great hero

was Saint Maximillian Kolbe, another Polish priest who gave his life to save

another prisoner – a man with a family – at Auschwitz. He determined early on

to become a priest, but kept it a secret so that the authorities could not

alter his examination results or pressure the family to keep him out of the

seminary.

In 1966, his entire

seminary class was drafted into the special indoctrination unit in violation of

a church-state agreement. This cruel treatment was reserved for the most

outspoken church leaders, including the future Pope John Paul II.

The horrible treatment he

received in this “special unit” broke his health, but not his spirit. He wrote

to his father “It turned out to be very tough, but I can’t be broken by threats

or torture.” His seminary professors demanded that he take a period of rest,

but he refused. “One doesn’t suffer when one suffers for Christ,” was his

reply.

He became so weak that he

suffered recurring fainting spells. A fellow priest found him lying in a dead

faint at the foot of the altar, unconscious. After he endured another long

hospital stay, it was discovered that Father Jerzy suffered from a serious

blood disorder. He would need transfusions after each recurrence of the

illness. He was placed on a special diet. His doctors hoped that a quiet life

would prevent further episodes. He planned to rest and spend more time with his

beloved seminary students when the call came that would give him no rest for

the remainder of his life. His new position as chaplain to factory workers

“gave him wings,” and changed the course of his life. He worked tirelessly to

learn how to operate machinery, but more importantly, he grew to love the

workers and they grew to love him. He tore down barriers between himself and

the worker; there were many baptisms and weddings. All this brought him much

joy.

In the meantime, He was

shadowed relentlessly by the secret police, receiving death threats and urged

to break contact with his beloved workers. “Truth that costs nothing is a lie,”

became his motto.

In autumn of 1981, Father

Jerzy came to the United States to attend the funeral of a beloved aunt. Like

many Poles, he loved America and his many friends tried to convince him to stay

and take political asylum. He knew that his people would be in danger if did

that: “They need me and I need them.” So, as soon as the funeral was over, he

flew back to Warsaw.

The communist regime

declared a “state of war” against the Polish people on Dec 13, 1981 and, after

attacks by security forces on factories and demonstrators, the Solidarity

movement was forced underground. Solidarity was the first independent labor

union founded within the Soviet bloc. It had over nine million members. Those

workers who escaped arrest turned up at Father Jerzy’s apartment as soon as

martial law was declared. “It was reflex,” said one worker — “when in trouble,

see Jerzy.”

They came because they

knew he was not afraid. On one wall of his apartment was a huge map of Poland

marking every prison camp; next to it was a makeshift crucifix. When asked if

he was afraid to have such a thing on his wall, he answered, “It

is they who are afraid.” For Father Jerzy, his calling could be

summed up in a verse from Saint Luke that he had chosen when he was ordained.

It read, “To let the oppressed go free.”

The Polish people who had

heard of Father Jerzy came from near and far to help those oppressed by the

communists. People came from distant parishes and from abroad to give him aid.

While his own garments and shoes rotted away, he cared only to provide for the

needy, both Catholics and unbelievers. In return for their generosity, the

secret police persecuted his workers and students. They followed him wherever

he traveled. His apartment and car were electronically bugged so that the

secret police knew his location at all times.

Martial law had silenced

millions of Poles, but Father Jerzy was not afraid to speak out. He began to

hold special “Masses for the Homeland” as Christmas (the celebration of which

was forbidden) approached. Many of the miners from southern Poland were so

moved by the strength and confidence of his soft voice that they proclaimed

that it was the most powerful they had ever heard. Father said openly what they

really felt, but could not say. They would rise again after any humiliation,

“for you have knelt only before God.” The regime had banned the mere mention of

Solidarity, but Father declared, “Solidarity means remaning internally free,

even in conditions of slavery: overcoming the fear that grips you by your

throat.”

The “Mass for the

Homeland” grew into a national event, with people coming from all ver Poland to

attend. The most famous actors in Poland vied to take part in the readings.

Even at his Masses,

security forces forces circled the church as police tried to incite the

congregation. Father’s only words were “Overcome evil with good.” The priest

received hundreds of letters of thanks from Mass-goers, thanking him for

restoring their faith. There were many conversions, including ranking

communists who dared not go to anyone else. They knew that they could trust

this priest.

Thousands of paper copies

and audio cassettes were made of his preaching and spread across Poland. Church

officials had forbidden the spread of these materials; so Father had to open

his own underground print shop. His acclaim grew so great that even the Warsaw

police refused to take part in actions against him. Men from other parts of

Poland had to be brought in to do the dirty work.

As his Masses grew in

popularity, the greater became the threats and harassment. “The most they can

do is kill me,” he said. However, when the first attempt was made on his life,

he was shaken. He had just collapsed into bed at 2 AM on the first anniversary

of martial law, exhausted from preparing Christmas gifts for the children in

Warsaw’s hospitals, when the doorbell rang. Father was too tired to get up and

answer it. A moment later, a bomb crashed into the next room, blowing out the

windows where he would have been standing.

Father was astonished at

the hatred behind this attack. He had always thought that he would be exiled to

Siberia like generations of Polish priests before him. He had even kept

practicing his Russian so that he could “preach the good word in the camps.”

Now he confided to a friend that he began to feel real fear. But nothing would