Francisco Garcia, Istoria della conversione alla nostra Santaa Fede dell'Isole Mariane, Naples, 1686, pl. XV : Martyre du Padre San Vitores by Mata'pang and Hurao en 1672 à Guam». en:Category:Images of Guam

Bienheureux Didace-Louis

de San Vitores

Martyr aux Iles Mariannes

(+1672)

Diego Luis de San Vitores.

Béatifié le 6 octobre 1985 par Jean-Paul II, Diego de San Vitores est né en Espagne en 1627. Très tôt, une phrase de l'Évangile l'interpelle: «J'ai été envoyé pour évangéliser les pauvres» (Lc 4, 18). Mais, il doit vaincre des résistances pour entrer chez les Jésuites et pour réaliser son idéal missionnaire, notamment de la part de son père dont il est le préféré. Ensuite, ses supérieurs, qui apprécient son talent d'orateur, ne le laissent pas partir de sitôt. Finalement, En 1668, à l'âge de trente-trois ans, il parvient enfin sur son lieu de mission, aux îles Mariannes, lesquelles n'avaient pas encore été évangélisées. Embrassant un genre de vie très pauvre, qui est celui des gens du lieu, les Chamorros, il prêche avec zèle, baptise, construit églises et collèges. Quand la situation devient périlleuse, il ne ralentit pas ses activités missionnaires. Il est tué en 1672 avec son catéchiste, le bienheureux Pedro Calungsod qui a été béatifié le 5 mai 2000 par Jean-Paul II. Pedro est originaire des Philippines, il a 17 ans et, catéchiste, il accompagnait depuis 4 ans les jésuites espagnols lors de l'évangélisation des Chamorros. (source: abbaye Saint Benoît)

21 octobre 2012 - canonisation à Rome de Jacques Berthieu, Pedro Calungsod, Giovanni Battista Piamarta, Maria Carmen Sallés y Barangueras, Marianne Cope, Kateri Tekakwitha, Anna Schäffer - Livret de la célébration avec biographies en plusieurs langues.

Un internaute nous signale que Pedro Calungsod (1654-1672), laïc martyr à Guam, est le patron de la jeunesse philippine.

À Tumhom, village de l'île de Guam en Océanie, l'an 1672, les bienheureux

martyrs Didace-Louis de San Vitores, prêtre de la Compagnie de Jésus, et Pierre

Calungsod, catéchiste, qui furent massacrés sauvagement en haine de la foi par

quelques apostats et des indigènes païens, et précipités dans la mer.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/11144/Bienheureux-Didace-Louis-de-San-Vitores.html

Bienheureux Diego Luis de

San Vitores sj 6 octobre : menologe d’Espagne

Martyr, Fête le 6 octobre

Né en 1627 à Burgos d’une

famille noble, Diego Luis entra dans la Compagnie à 13 ans après avoir vaincu

la résistance de son père. Dès son noviciat il se fit remarquer par la ferveur

de sa piété et la vivacité de son esprit. Prêtre en 1651, il se consacra, après

son 3e An, à l’enseignement universitaire et à différentes formes d’apostolat

jusqu’à ce que le Père Général Goswin Nickel lui accorde de partir pour les

missions.

En 1660, il quitta sa

patrie et travailla courageusement pendant deux ans à Mexico en attendant

l’arrivée d’un bateau pour les Philippines. De 1662 à 1666, il exerça les

charges de maître des novices, de préfet des études et de professeur de

théologie, tout en se consacrant avec un grand zèle à l’apostolat auprès des

indigènes. Mais il désirait surtout annoncer le Christ aux habitants des Iles

Mariannes, lesquelles n’avaient encore jamais entendu parler du Christ. Il y

arriva en 1668 après avoir surmonté toutes sortes de difficultés.

Pendant quatre ans il y

partagea les consolations et les croix des missionnaires. En 1672 il fut tué en

haine de la foi au village de Tumon. Jean Paul II l’a béatifié en 1985.

6 octobre

Bienheureux DIEGO LUIS DE

SAN VITORES

prêtre et martyr

Commun d’un martyr (p.

237) ou des pasteurs (p. 260).

OFFICE DES LECTURES

Ménologe de l’Assistance

d’Espagne de la Compagnie de Jésus.

Le bienheureux Diego Luis

de San Vitores fut tué le 2 avril 1672 dans l’île de Guam alors qu’il venait de

baptiser une petite fille mourante : ce martyre lui valut d’être le premier

apôtre des Iles Mariannes. Il y avait construit, en peu d’années, huit maisons

florissantes, fondé trois écoles pour l’éducation des jeunes gens et jeunes

filles, et baptisé de sa main plusieurs milliers d’indigènes.

Le bienheureux Diego

Luis, réalisant les vœux ardents et les promesses de son adolescence, était

venu dans l’île de Guam avec d’autres jésuites et un catéchiste de 14 ans. Pour

encourager ce dernier à le suivre, il lui avait suffi de l’inviter par ces mots

: « Veux-tu venir avec moi dans le pays où tu deviendras martyr du Christ ? »

Il le fut en effet deux jours avant la mort du bienheureux. Celui-ci, ayant

appris suffisamment la langue des habitants de l’île pendant la traversée,

avait commencé son travail missionnaire en annonçant immédiatement Jésus Christ

sur la place publique. Après ce premier discours, un très grand nombre de catéchumènes,

dit-on, se firent instruire dans la doctrine chrétienne. On rapporte qu’il

baptisa tout de suite des petits enfants, pour le salut éternel desquels il

priait et mortifiait quotidiennement son corps, demandant à Dieu de ne pas

mourir avant d’avoir vu ces enfants confirmés dans la foi.

Dieu lui accorda encore

quatre années de vie ; tandis qu’il s’adonnait avec zèle à son œuvre

missionnaire, il fut transpercé d’un coup de lance par un apostat fou de

colère. Il rendit l’âme en implorant calmement la miséricorde de Dieu pour

lui-même et pour son meurtrier. Il avait 45 ans. Le bienheureux Diego Luis, qui

espérait mourir en vivant sa vie sacerdotale dans les missions, réalisait enfin

le vœu qu’il avait lui-même confié autrefois au Père Général Goswin Nickel :

« Depuis mes années

d’enfance dont je puis me souvenir, tout mon désir a été (selon mon âge et

peut-être même en le dépassant) la conversion des infidèles et le martyre.

Ce désir ancré en moi a

grandi de jour en jour, surtout celui de conduire les âmes des infidèles au

Christ, de verser mon sang pour cela, sans que jamais je puisse détourner mon

esprit en un autre sens.

Tel est donc le désir qui

se présentait à moi : verser mon sang pour le nom du Christ et pour le salut

des âmes les plus abandonnées. Toutefois je ne désire pas cela en sorte que je

veuille aller dans les missions pour obtenir la palme du martyre ; mais plutôt

en sorte que, à cause des missions, je ne craigne aucun genre de travail et

même de mort ; je me déclare prêt à quitter non seulement cette vie mais à

abandonner une mort glorieuse, pourvu que je gagne même une seule âme au

Christ. »

(Anon., 1784, Archives

Loyola – S. C. pour les Causes des Saints, Officium Historicum, 94, Déposition

sur la vie et le martyre du Serviteur de Dieu Diego Luis de San Vitores,

Rome, 1981, pp. 90-97).

R/ Je me suis bien battu,

j’ai tenu jusqu’au bout, je suis resté fidèle ;

* je n’ai plus qu’à

recevoir la récompense du vainqueur.

V/ Je considère toute

chose comme une perte en vue de connaître le Christ et de communier aux

souffrances de sa Passion, en reproduisant en moi sa mort.

* Je n’ai plus …

Seigneur notre Dieu, par

le ministère et le martyre du bienheureux Diego Luis, ton prêtre, tu as révélé

à ceux qui ne croyaient pas encore l’Évangile et l’amour du Christ ; par son

intercession accorde-nous d’être des témoins de la vérité et de la charité

évangélique.

2 janvier 2013

SOURCE : https://www.jesuites.com/diego-luis-de-san-vitores-sj/

Blessed Diego Luis San Vitores Portrait

Blessed

Diego Luis de San Vitores-Alonso

Profile

Member of the Jesuits,

joining in 1634. Ordained a priest on 23

December 1651.

He served several years as a teacher in

the Spanish cities

of Toledo, Madrid and Alcalà, but in 1660 was

finally able to moved to missionary work.

He studied in Mexico from 1660 to 1662,

and then was assigned to the Philippines.

After obtaining the proper permissions and funding, he moved on to the island

of Guam in 1668 where

he founded the first Catholic church,

and established the Spanish presence

in the Mariana Islands. Murdered by

a gang of anti–Christian pagans led

by an apostate name

Matapang while trying to save Saint Pedro

Calungsod whom they had already attacked. Martyr.

Born

13

November 1627 in

Burgos, Spain

body dumped into the

ocean

9

November 1984 by Pope John

Paul II (decree of martyrdom)

6

October 1985 by Pope John

Paul II

Additional

Information

other

sites in english

Blessed Diego Luis de San Vitores Church

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

nettsteder

i norsk

strony

w jezyku polskim

MLA

Citation

“Blessed Diego Luis de

San Vitores-Alonso“. CatholicSaints.Info. 14 May 2024. Web. 7 December

2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-diego-luis-de-san-vitores-alonso/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-diego-luis-de-san-vitores-alonso/

Blessed Diego Luis de San

Vitores

Established the Christian

presence in the Mariana Islands.

Jesuit Missionary to Guam

(1627-1672)

His life

+ Diego Luis was born to

a noble family in Burgos, Spain. In 1640, he entered the Society of Jesus and

was ordained in 1651.

+ Fulfilling his

long-time dream of being a missionary, Diego Luis was granted permission to

serve in the Philippines. As he was making his way there, the ship carrying him

stopped in Guam and Diego Luis vowed to return there.

+ In 1665, he persuaded

King Philip IV to establish a new mission in Guam. This became a reality in

1668. Diego Luis established the first Catholic church in Guam in 1669.

+ After years of serving

with limited success and the death of a friendly local chief who had supported

the missionaries, members of the Chamorro (an indigenous tribe) rose against

the missionaries who refused the protection of Spanish soldiers.

+ Blessed Diego Luis was

martyred on April 2, 1672. Killed with him was his assistant, a Filipino lay

catechist, Saint Pedro Calungsod. After the murders, the Christian Faith spread

quickly throughout Guam.

+ Blessed Diego Luis was

beatified in 1985. Saint Pedro Calungsod was canonized in 2012 and is also

honored on this day.

Spiritual bonus

The eight days spanning

from Easter Sunday to the Second Sunday of Easter (also known as Divine Mercy

Sunday) are celebrated as the Octave of Easter. Each of these days is

considered a celebration of Easter Day, reminding us that the victory of Christ

over death cannot be limited to a single day of celebration.

Quote

“The Christian is a

missionary of hope. Not by their merit, but thanks to Jesus, the grain of wheat

who, fallen to the earth, died and brought much fruit.”—Pope Francis

Prayer

We humbly beseech the

mercy of your majesty, almighty and merciful God, that, as you have poured the

knowledge of your Only Begotten Son into the hearts of the peoples by the

preaching of the blessed Martyrs Diego Luis and Pedro, so, through their intercession,

we may be made steadfast in the faith. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for

ever and ever. Amen.

(from The Roman

Missal: Common of Martyrs—For Several Missionary-Martyrs)

Saint profiles prepared

by Brother Silas Henderson, S.D.S.

SOURCE : https://aleteia.org/daily-prayer/monday-april-2

Father Diego Luis de San

Vitores

Marianas evangelist

Father Diego Luis de San

Vitores (1627 – 1672), a member of the religious order of the Society of Jesus

(Jesuits), brought Christianity to the CHamoru people in 1668. He was killed on

Guam 2 April 1672 just a little less than four years after his arrival, a death

that he welcomed because he would be considered a martyr in his efforts to

spread Christianity.

In the latter part of the

17th century, as the fervor of the Spanish empire’s expansionism to gain global

and economic power and Christian conversion spread, San Vitores came to Guam

and established the first Catholic Church in the Marianas, altering the social,

cultural and religious landscape of the fifteen-island archipelago.

Throughout his missionary

efforts, the people of Guam and the Mariana Islands took part in events that

transformed their island into the first permanent European Christian settlement

in Oceania. Hagåtña became the first European city after the establishment of

colonial government and hosted the beginnings of a European educational system

on Guam. The CHamorus survived a massive cultural upheaval as many traditional

institutions and cultural practices were eradicated and others adapted to

Catholic institutions and Spanish cultural practices.

One of the earliest

records of contact with the CHamorus of the Mariana Islands and Europeans was

when Ferdinand Magellan’s lost expedition (during its search for the Spice

Islands) berthed off Guam’s shores in 1521. Although, Miguel de Legazpi

wouldn’t claim the island for the Spanish empire for another forty-four years,

the Spanish would have no real interest in the islands until 1668, when San

Vitores’ five-year-long bid to establish a mission in the Marianas was finally

realized.

Early life

San Vitores was the son

of a nobleman. He was born Diego Jeronimo de San Vitores on 12 November 1627 in

the city of Burgos, Spain to Don Jeronimo San Vitores de Portilla

and Dona Maria Alonso Maluenda. Diego Luis de San Vitores entered the

Society of Jesus as a novitiate at the age of thirteen after having overcome

opposition from his parents who wished him to join the military and feared that

there would be no other son to carry on the family name as his brother Miguel

had died at the age of seven. His parents finally conceded, however, to his

wishes and he assured them that they would have several more children.

After becoming a member

of the Society of Jesus, he changed his name to Diego Luis de San Vitores as it

was the custom of the time to take the name of a saint. On 23 December 1651 San

Vitores was ordained a priest in Spain at the age of twenty-four.

Encountering the Chamorus

San Vitores’ first

encounter with the CHamorus was in 1662 while he and other missionaries were in

transit to the Philippines aboard the Spanish galleon San Damian. The ship

made a brief stop at the “Islas de los Ladrones,” or “Islands of Thieves”

as the Marianas were known at the time. (The islands received this unfortunate

name after Magellan’s lost, starved, and scurvy-ridden convoy landed there in

1521 and a dispute over a skiff led to a deadly attack on the CHamorus. Before

the incident occurred, Magellan initially named the islands “Islas de las Velas

Latinas” or the “Islands of Lateen Sails,” for the swiftness, agility and

maneuverability of the proas that the CHamorus navigated.)

As San Damian pulled

into the waters off the island of Guam, San Vitores sighted the CHamorus and

felt a great desire to “bring the light of Christianity” to what he interpreted

to be Godless islanders. He continued on to his mission in the Philippines, but

went to great lengths to find a way to begin a mission in the Marianas. He used

his father’s influence as a member of the Spanish Crown Treasury to get the

support of Queen Maria Ana de Austria for his way to the islands. In 1665,

three years after San Vitores first visited the islands, Spain’s King Philip

IV, issued a royal cedula, or royal decree, ordering the missions to begin

in the islands.

Despite the court’s

endorsement, San Vitores encountered several setbacks from Spanish authorities

in the Philippines and Mexico, which oversaw the funding of overseas expeditions

in the Pacific region. The resistance was presumably because the expense to

bring the missionary to the isolated islands was economically burdensome and

would not yield an economic profit. San Vitores was determined, however, to

reach the islands and was eventually successful.

In June 1668, the patache (or

supply boat) San Diego arrived off the shores of Guam’s primary

village, Hagåtña, carrying San Vitores and other missionaries to begin their

efforts. For her support, San Vitores renamed the archipelago Islas de

Marianas, the Mariana Islands, in honor of Queen Maria Ana. He subsequently

renamed the other islands in honor of Saints; Guam was renamed San Juan.

Conversion efforts

The first CHamoru

baptized was the infant daughter of a CHamoru mother and a Filipino castaway

named Pedro Calungsor who lived in the islands for thirty years after the 1638

shipwreck of the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción off Saipan’s coast.

Calungsor became San Vitores’ lay assistant and translator but later ran away

from him. After Calungsor left San Vitores the priest returned to the

Philippines and found another assistant with, ironically, the same name but who

was about seventeen-years-old. The younger Calungsor is also often referred to

as Calungsod in historical literature.

The first adult CHamoru

baptized was Chief Kepuha (Quipuha) from Hagåtña who gave land for the first

Catholic Church, which San Vitores dedicated as Dolce Nombre de Maria, the

Sweet Name of Mary. It was located near to where the present-day Dulce

Nombre de Maria Cathedral-Basilica stands in Hagåtña.

The CHamorus initially

welcomed San Vitores and the other Catholic missionaries and hundreds were

readily converted. The nobles of the community may have believed this would

elevate their social status while others village chiefs desired priests for

their own village, probably as symbols of status. Some islanders apparently

also received the sacrament of baptism more than once for the gifts of beads

and clothing they were given.

This enthusiasm for

Catholicism did not last long, however, as several factors quickly came into

play including the conflicts it created in the hierarchal caste system of the

CHamorus. The church preached that once baptized, people were equal in the eyes

of God. The missionary’s dogmatic zeal was also not well received as the

Jesuits shunned long-standing traditional beliefs and practices in trying to

assimilate the CHamorus in Christian doctrine. This included the rejection of

the CHamorus long standing veneration of ancestors. As part of the religious

practices of CHamoru culture, people had the skulls of deceased family members

placed in baskets in places of honor in their homes. The CHamorus believed that

this allowed their deceased to have a place to stay and often sought the

guidance of their ancestors and favors from them in their daily endeavors.

The missionaries told the

CHamorus that their ancestors (including parents and grandparents) were burning

in hell because they had not been baptized as Christians. The Christian

missionaries also looked down upon and ordered the burning and destruction

of Guma’ Uritao (men’s houses) because of what was considered

institutionalized prostitution. Boys lived in the Guma’ Uritao after

they reached puberty to learn the life skills they would need as men such as

canoe building, navigating, tool making and fishing. CHamorus believed that

learning about sex was also a valuable skill for youth. The women who taught

the uritaos (bachelors) about sex were not forced to live in

the Guma’ Uritaos, however, and it was considered honorable to become

a ma’ uritao. Men would leave the men’s houses and, usually, remained

married to one woman.

The social and cultural

importance of the Guma’ Uritao was lost to the missionaries who

remained fixated on what they perceived to be sinful acts in the Guma’

Uritao. To counter this form of accepted “cultural education,” San Vitores

created the beginnings of a colonial educational system by establishing

the Colegio San Juan de Letran in 1669, a seminary for boys; and

later a school for girls, Escuela de Ninas.

The tide of discontent

continued with the missionaries’ presence. For whatever reason, profit or

pride, historical documents pinpoint a Chinese man named Choco, who was living

on Guam for about two decades after he was shipwrecked in the Marianas prior to

the missionaries’ arrival, as having been the instigator of rumors that would

have negative ramifications for the missionaries.

Choco was married to a

CHamoru woman from Saipan, and living in the southern village of Pa’a (which

has now disappeared in present-day Guam). Choco came to the Marianas when the

boat he and other Chinese men sailing from the Philippines shipwrecked.

Choco promoted the rumor

that the baptismal water and anointing oils used in religious rites were

killing people, thwarting conversion efforts so much that San Vitores would

eventually end up confronting Choco at Pa’a. The two were locked into in a

days-long public debate about religion with Choco supposedly conceding and even

receiving baptism, but it did not take long for him to renounce Catholicism.

Martyrdom

The murder or San Vitores

and his assistant occurred at the height of a circulation of Choco’s rumors and

festering animosity between the CHamorus and the missionaries. San Vitores and

Pedro Calungsor were killed in Tumon on 2 April 1672 after he baptized the

infant daughter of Chief Mata’pang of Tumon, who was once a Christian convert,

without his consent. Mata’pang believed the baptismal waters would kill her.

When Mata’pang discovered San Vitores’ actions he enlisted a warrior, Hirao, to

kill San Vitores.

Despite San Vitores’

death, evangelization continued even more aggressively at the expense of the

lives of CHamorus and some Spaniards. Defiant CHamorus did not acquiesce to

colonial forces, but were eventually subdued by the colonizers’ advanced

weaponry. Their plans to rid the island of the Spaniards were thwarted, too, by

CHamorus who had chosen Christianity and who defended the Spanish against

attacks.

CHamorus from throughout

Marianas were forced to relocate to Guam and Rota to live in Spanish-style

villages with a Catholic church as a focal point, and forced to abandon

traditional ways of life such as seafaring.

Quest for Sainthood

Today Catholicism is the

leading religion on Guam and throughout the Mariana Islands. There is a

monument in Tumon, near the site of San Vitores’ death, showing the priest

baptizing the chief’s daughter as Mata’pang stands behind him lifting a sword

ready to strike the priest. Hirao is also behind he priest while Mata’pang’s

wife kneels watching her daughter being baptized.

The Catholic Church in

the Marianas, now led by CHamoru priests, has spearheaded efforts to have San

Vitores recognized as a saint. This effort was begun by the first CHamoru

bishop, Felixberto C. Flores, who was later elevated to archbishop. San Vitores

was beatified, along with his assistant Pedro Calangsod, in 1985.

For further reading

Garcia, Francisco,

S.J. The Life and Martyrdom of the Venerable Father Diego Luis de San

Vitores of the Society of Jesus, First Apostle of the Mariana Islands and

Events of These Islands from the Year Sixteen Hundred and Sixty-Eight Through

the Year Sixteen Hundred and Eighty-One. Translated from Spanish by Margaret M.

Higgins, Felicia Plaza and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough.

Mangilao, GU: University of Guam Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research

Center, 2004.

Hezel, Francis X,

S.J. Journey of Faith: Blessed Diego of the Marianas. [Hagåtña?]:

Guam Atlas Publication, Guam, 1985. Also published as “Diego Luis de San Vitores.” Pacific

Voice, October 6, 1985. Also available online at Micronesian

Seminar (accessed August 4, 2010).

Johnston, Emilie G.,

ed. Father San Vitores: His Life, Times and Martyrdom. MARC Publications

Series 6. Mangilao, GU: University of Guam Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area

Research Center, 1993.

Levesque, Rodrigue, comp.

and ed. Revolts in the Marianas. Vol. 6, History of Micronesia: A

Collection of Source Documents. Gatineau, Quebec: Levesque Publications,

1995.

Risco, Alberto,

S.J. The Apostle of the Marianas: The Life, Labors, and Martyrdom of Ven.

Diego Luis de San Vitores, 1627-1672. Translated by Juan M.H. Ledesma,

S.J. and edited by Msgr. Oscar L. Calvo. Hagåtña: Diocese of Agana, 1970.

SOURCE : https://www.guampedia.com/father-diego-luis-de-san-vitores/

Blessed Diego Luis de San

Vitores, SJ

(1627-1672)

Martyr of the Marianas

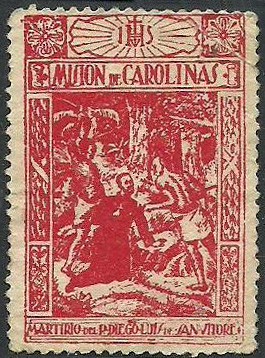

Spanish Jesuits were sent

in 1921 to work in the Caroline, Mariana and Marshall Islands as replacements

for the previous German missionaries. They and others worked in the region

until they were imprisoned and eventually executed in 1944. After the war the

mission fell to the care of American Jesuits. The above cinderella showing the

martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, SJ was issued presumably in the 1920s

or 1930s.

Blessed Diego Luís de San

Vitores (1627–1672) was a Spanish Jesuit missionary who founded the first

Catholic church on the island of Guam. He is responsible for establishing the

Spanish presence in the Mariana Islands. A son of a nobleman, he was baptized

Diégo Jeronimo de San Vitores y Alonso de Maluendo. His parents attempted to

persuade him to pursue a military career, but San Vitores instead chose to

pursue his religious interests. In 1640, he entered the Jesuit novitiate and

was ordained a priest in 1651. Believing his calling was to serve as a

missionary to non-Christians, San Vitores was granted his request and assigned

to a mission in the Philippines.

While in Mexico en route

to Guam, San Vitores had difficulty encouraging the Spanish viceroy to fund his

mission. However, in 1668, Padre Diego Luis de San Vitores set sail from

Acapulco to Guam. San Vitores named the Chamorro archipelago, "Islas

Marianas" (Mariana Islands) in honor of the Queen Regent of Spain, Maria

Ana of Austria, and the Blessed Virgin Mary. The missionary landed on Guam in

the village of Hagåtña and was greeted by Chief Kepuha. Kepuha's family donated

land to establish the first Catholic mission on Guam. On February 2, 1669 Padre

San Vitores established the first Catholic church in Hagåtña and dedicated it

to the sweet name of Mary, "Dulce Nombre de Maria." After Chief

Kepuha's death in 1669, Spanish missionary and Chamorro nobility relations

worsened and the Chamorro-Spanish War began in 1671 led by Chief Hurao. After

several attacks on the Spanish mission, a peace was negotiated. Though San

Vitores chose to emulate Saint Francis Xavier, who did not use soldiers in his

missionary efforts in India, as his model priest, he recognized that a military

presence would be necessary to protect the priests serving Guam. In 1672, San

Vitores ordered churches built in four villages, including Merizo. Later that

year, Chamorro resistance increased, led by makahnas and kakahnas (indigenous

priests and priestesses) from the Chamorri (upper caste) who would lose their

leadership position and status under a Roman Catholic mission organization and

male-dominated Spanish society.

The assassination of

Padre San Vitores in 1672 by Mata'pang and Hirao. On 2 April 1672, Mata'pang

and Hirao killed San Vitores and his Visayan assistant, St.

Pedro Calungsod. San Vitores had baptized Mata'pang's newborn daughter

without the chief's permission; Mata'pang's wife consented to the baptism

according to some accounts. Some records state that Mata'pang had believed holy

water used in baptism had caused the recent deaths of babies due to European

diseases.

The death of the Spanish

mission leader led to Spanish army reprisals against Chamorro chiefs who had

decided to defend their homeland from Spanish subjugation. Bounties were

offered for these chiefs' decapitated heads and many were hunted down. Under

Spanish military governors, Chamorros who were anti-Spanish were massacred in their

villages. European plague and warfare eventually contributed to the defeat of

the Chamorros. The Chamorro-Spanish Wars lasted more than 25 years. More

SOURCE : https://www.manresa-sj.org/stamps/1_SanVitores.htm

Blessed Diego Luis de San Vitores (1627-1672)

Author: Francisco Garcia, S.J.

Authored on: 9/30/1999

Of the Life and Martyrdom of the Venerable Padre Diego Luis de Sanvitores of the Society of Jesus, First Apostle of the Mariana Islands

CHAPTER I

The Nature of the Islas Marianas, Temperament and Customs of Their Natives.

The islands called formerly de Los Ladrones and de Las Velas Latinas whose name has now fortunately been changed through Religion into Las Marianas, are innumerable and run from north to south, from Japan to Peru. The thirteen discovered and illumined by the Gospel, are the only ones of which I wish to speak, from the information which the ministers of the Gospel (missionaries) have given. They have traveled over them many times, correcting the information of the older voyagers who saw them only from a distance or in great haste. They are situated in longitude 164 degrees from La Palma, Canary Islands and three hundred leagues nearer than Manila on the voyage from New Spain to the Philippines, 13 degrees latitude boreal from Muag which is 22 degrees and is the nearest one to Japan that has yet been discovered in the small boats that the missionaries have had thus far. From the charts and letters it is a matter of six days journey from japan. These thirteen islands are in their position so Marian that starting from the southwest to Northwest they form a crescent, a very appropriate throne for the feet of Mary and a symbol of the protection of this Sovereign Queen, in spite of Mahoma who has united to his crescent many of the islands of this archipelago.

Their names, not as they

are confused in some histories but as they were written by Padre Sanvitores who

changed the names into sacred ones, since he wished to make even the land

itself Christian, are in order (from the south to the north) as follows: Guam,

which he called San Juan; Arpana, which he called Santa Ana; Aquiguan, renamed

the Holy Angel; Tinian called Buenavista Mariana; Saipan, Saint Joseph;

Anatajan, St. Joaquin; Sariguan, St. Charles; Guguan, St. Philip; Alamagan, La

Concepcion; Pagon, St. Ignatius; Agrigan, St. Francis Xavier; Asanson, la

Asuncion; and Maug, San Lorenzo. The largest are Guam, which is 35 leagues

square and Aguigan which is fifty. The latter is more fertile and pleasant than

the others. The islands are not far apart, the farthest only a day's journey

from another. They have commerce and use the same language, a rare thing among

gentiles who are not subject to one dominion.

The climate is healthful and benign, although the last islands (northern) are

cooler than the first and in none is the cold or heat excessive. They do not

suffer the terrible earthquakes that are known in other islands of the

archipelago. The land is mountainous and has great marshes, always covered with

a spiny growth, with many trees but none of those of Europe. The most noticeable

tree is the one they call in their language "Maria" (Palo Maria) of

which they construct their houses and boats. Under the title of

"Maria," a harbinger of happiness and of the good tidings which would

be theirs through this name(?). The islands have many rivers of fresh

water, and on the Island of Guam there are more than thirty. No alligators

are found, nor snakes, nor other poisonous animals. There are fish in the

rivers, especially eels, but for some superstition, they do not catch

them. On the land there are not found other animals than cats and dogs which

are believed to have remained here from the galleon Concepcion when it was

wrecked in these islands. In the air are seen birds that resemble turtle doves.

The islanders do not eat them, but keep them in cages and teach them to

speak. Thus far no mines of silver or gold have been found nor anything of

value. That which is most valuable among the natives is iron, for

which they trade with the Spanish ships, exchanging the poor products of their

soil also tortoise shells, and whoever has the most iron is the most powerful.

Nature is parsimonious with these people, and they are content with so

little. Certainly a lesson for those who seek after material things to satisfy

their insatiable thirst and hunger. It goes to show that very little

suffices him who does not seek what is extra and nothing is extra to him who is

not content with only the necessary. The islands have many ports where

ships can anchor, some of them very suitable for the ships that come from New

Spain as well as those from the Philippines, unless contrary winds make

entrance impossible which the Servant of God believes is the work of demons

because of their fear of losing to the Faith their long held dominion

over these Islands. Now we are confident that the Star of the Sea will

appease the winds since the Marinas are under Her protection as well as under

her title.

In the Island of San Juan there are seven ports; that of San Antonio which is

in the western part, across from a town which the natives call Hati, in which

port there are two good rivers from which to obtain water. Another port, which was vented

by the Dutch for some three months during past years, careening their ships, in

half a league from the point that divides the inlet of San Antonio from the southern

part and faces a village, called in their language, Humatag. It has a good

river where the Dutch obtained water. Proceeding on this side from the south, there is found a

third port three leagues distant, at a village called Habadisan. It has some

shelter from the west and more from the north, but lacks a river. Traveling three leagues to

the eastward two bays are found, separated by a point of land, where there are

two rivers. The first bay faces a village called Pipug, and the second more to the

east, faces a village called Irig. it is well sheltered from the west and has

sufficient protection also from other winds. Leaving the port of San Antonio which we

mentioned before, and proceeding along the coast on the north within the

distance of a musket shot there is another port at a village called Tarogrichan, with rivers

of good water, which has on both sides, the same shelter from the winds as San

Antonio. Continuing more to the north, near the town of San Ignacion de Agadna, where

now are located the principal church and house of the Padres of the society in

front of a reef which faces West-Northwest at a distance of a shot of an arguebus from

said reef, there is found a very good sandy anchorage and land for the length

of 18 brazas and at a distance of two musket shots from the reef the depth is of 10

brazas and going in further at a distance of a shot of an arguebus from land

the depth of the water is of 22 brazas. It has a good river which flows into the center of

the bay. It is protected from all winds and appears to be the best port and

most appropriate of the island of San Juan. On the Island of Zarpana or Santa Ana,

which the natives call Rota, or Luta, there is a port in which the Dutch

anchored the three ships mentioned above. It faces a settlement called Socanrago and San

Pedro, and looks towards the north-east. One league to the south there is

another port with good depth and protection from all winds. On the island of Saypan there is

a good port, whose entrance faces the east, and is protected by the principal

point of the island, which looks to the southeast. The port is near a village which is

called Raurau. In the islands farther north, called Pani, and Los Volcanes. It

is said that there are good ports, especially one on the western part of Agrigan, a distance

of some fifteen leagues beyond Los Volcanes, which is said to be a suitable

anchorage for ships coming from Manila. All these ports nature has opened in these

islands in order that the Faith might enter if people would enter through a

port other than that of their own interest. Whence came the people of these islands is only surmised

but is not known. Padre Colin in his India Sacra, believes that they came from

Japan and he makes this seem credible because of their nearness to Japan, the

similarity of the people in many ways, expecially in the high regard they have

for the nobility, in spite of their own poverty. they have preserved in their memorized history

which is confused with many fables a belief that they came from the south or

west. The similarity of their skins and of their language, coloring, the teeth, and their

mode of governing, or lack of it, makes one suspect that they may have the same

origin as the Bisayos of Tagalogs. There are some inhabitants who would trace their

history to the Egyptians, according to the reference of Gomara, in his Historia

de las Indias as Magellan learned when he came to these islands in 1521. When or how the

first people came here is still unknown. It must have been a storm that spared

their lives but drove them to a sterile land. The number of inhabitants is large. In Guam

alone there are fifty thousand, on other island forty thousand, and less on

others, divided among the town and villages, along the beaches, usually in groups of fifty, sixty

or even a hundred and fifty houses. In the mountains there are from six to ten

or twenty in a group. The houses are the cleanest that have yet been found among Indios;

built of coconut and palo Maria. the walls and the ceiling made in the style of

a vault are curiously woven of coconut leaves. They have four rooms, with doors, and

curtains of the same matting. one serves as sleeping room, another for storing

food, one as kitchen, and the fourth is large enough in which to build and store

boats. The Marianos are in color a somewhat lighter shade than the Filipinos,

larger in stature, more corpulent and robust than Europeans, pleasant and with agreeable

faces. They are so fat they appear swollen. The women wear long hair and in

various ways they bleach it white. They color their teeth black, believing this is a

great adornment to their beauty. The men do not wear long hair, but shave their

head leaving only a small topknot on the crown, about the length of a finger. They remain in

good health to an advanced age and it is very usual to live ninety or one

hundred years, and among those who were baptized during the first year of the Mission, there

were more than a hundred twenty persons who were more than one hundred years

old. It may be due to their robustness, being accustomed to certain distempers from

the cradle, or for the uniformity and natural condition of their food, or

because of exercise and not too much anxiety, and for the lack of vices and worries, which

are roses with thorns, which flattering and then grieving men, finish them off.

Perhaps all together contribute to the prolonged age of the Islanders. Since they have

few ailments they know few medicines, and treat themselves with a few herbs, of

which experience and necessity have taught them the uses and virtues. Their costume

is that of a state of innocence although with the vices which sin brings about,

but fewer than their nudity and barbarity would promise. Only the women cover as much as

modesty requires with an apron called tifis. They live during four months of

the year on products of the ground, coconuts, which are abundant, bananas, sugar cane,

and fish. the remainder of the year they supplement the lack of fruits with

certain roots similar to sweet potato. The little rice which is grown they save for festines.

They practice no excess in eating: they have no wine or other intoxicating

liquor which as been a great impediment for the Faith in other countries. Their drink is water

and thus their commonest ailment is dropsy. Their occupation is the cultivation

of coconut groves and banana trees, the care of crops, and sea fishing. As they are

accustomed to this from childhood, they appear more like fish than men. Their

boats are very light, small and pretty, painted with a kind of bitumen which colors the hills

of Guam red. It is mixed with lime and coconut oil, and beautifies their boats

greatly. their language is easy to pronounce and to understand, especially for anyone who

knows Tagalog or Bisayan. It is reduced to a few rules and much freedom is

permitted in variety of vowels and consonants in a single word. This within the same island

and within the same town; it causes embarrassment to those who are beginners

since the difference of tense is very small. It is an elegance of style to place the

noun before the adjective. Thus they called Padre Sanvitores from the time he

arrived in the islands Padre Maagas which means Grande Padre. They practice many courtesies,

and an ordinary usage, on meeting and on passing in front of another, is Ati Arinmo which means: "Give me permission to kiss your feet." And if

one passes by a house they ask him if he will remain to eat, and they bring out

buyo (Betel nut) which is a plant they like very much, and keep in the mouth, like tobacco. To

pass the hand over the breast of the person one visits is considered a great

courtesy.

They rarely expectorate, and do so with great modesty and never near the house

of another, nor in the morning, in which there appears to be some superstition,

I do not know what. It is unnecessary to ask if they know any letters, sciences or

arts, those who are ignorant even of the elements, and did not know of the

existence of fire in the world until they saw it lighted by Spaniards who survived the

shipwreck in 1638. For all this, they admire poetry and believe poets to be men

who perform wonders. We wonder at times how such great ignorance goes hand in hand with

their great conceitedness through which they think themselves the wisest and

most talented of the world and despise all other nations as compared to themselves.

Their barbarity is not in keeping with the great esteem which they have for

their nobility and their observance and discretion of lineage, high, low and

middle class, which would seem to point to an origin in some civilized nation. It is seen how

pride banished from heaven, lives in all parts of the earth, among clothed

people, and the unclad alike. For nothing in the world would one of their chiefs, called

Chamorris, marry the daughter of a commoner, even if she were very rich and he

very poor as is said of the Japanese. Formerly, parents of the nobility killed sons who

married daughters of plebeian families whether it be for love or for riches. In

order to maintain their family status with splendor, the first born inherits large

estates of coconuts, bananas, as well as other choice properties and it is not

the son of the

defunct who inherits his father's estate but rather the brother or nephew of

the defunct. The heir now changes his name and takes the name of the founder or

chief ancestor of the family. Those of low station are not permitted to eat or drink

in the houses of the nobles, or even to go near them. If they need anything

they ask for it from a distance. These customs exist principally in the town of Agadna, where

through the goodness of the water and other conditions which in this location

are better than elsewhere, the Principals who came from Japan or from elsewhere gathered.

All the inhabitants of the island fear and respect the chiefs of Agadna. There

are in this settlement fifty three principal houses. As for the rest up to one hundred

and fifty are on separate grounds because they are of low people and would be

given no part in the affairs of the town or the court. The nature and temperament,

although at first seemed harmless and nude of deceit, as they were of clothing,

gained in Europe great praises of the Padres of the Society and of the first Spaniards

who dealt with them and allowed themselves to be persuaded by the

demonstrations of kindness and hospitality which they saw in them. Later it has been known to be

deceitful, double and treacherous, because they conceal with contrary words and appearances one or two years the feeling of offense which they received until

they find the opportunity for vengeance and they never heed promise to do nor

not to do whatever seem but to them. They are warriors of the most barbarous, easily

disturbed, and easily appeased, hesitant to attack, and prompt to flee. As one

town gets

ready to go against another with great shouts, but without a leader without

order or discipline they are wont to be two or three days in a campaign without

attacking, each observing the movements of the other; and when they arrive at the moment

of battle they arrange the peace very soon, because on falling dead two or

three on one side, it gives itself up as defeated, and sends ambassadors to the other,

with the tortoise shells which are the sign or surrender. The victors celebrate

the triumph with satiric songs, in which they exaggerate their valor, and make fun of the

conquered. The arms which they use are stones and lances in place or irons with

long hewn human bones. These are made of three or four shark tines which puncturing

easily the flesh, break off and some of the points remain inside the flesh

causing certain death. No remedy for this poison has been found although it was tried

later in Mexico by a team of doctors. They use these arms from childhood and

are very skillful in handling them; moreover, they can throw stones from a sling with

such dexterity and strength that they are able to drive them into the trunk of

a tree. They do not use the bow, nor arrow, nor sword; they have only some cutlasses and knives

acquired from our ships in exchange for their products. They have never used

the shield nor any other defensive arm, depending only on the swiftness of their

movements to prevent being injured and escape the blows of the adversary. They

are by nature jokesters (buffoons) enjoying fun and fiesta. The men get together to

dance, to play with lances, to run, leap, wrestle and to test in various ways

their strength, and amid these entertainments they retell with great laughter their stories or

fables, and a drink composed of gruel, rice and grated coconut. The women have

their own fiestas, in which they decorate themselves with wreaths on their foreheads,

sometimes of flowers resembling jasmine, sometimes of alvalorios and tortoise

shell, pendants of beads made from small pink shells which they value as much as we do

pearls. They also make belts of them with which they gird themselves, adding pendants all around of small coconuts over some skirts of strands of the roots

of trees, with which they finish off their regalia and finery, which looks more

like a cage than a dress. Twelve or thirteen get together and make a circle, without moving

from one spot, they sing in verse their histories and ancient things with

measured time and harmony of three voices: soprano, contraltos, and falsettos, with the

occasional tenor assistance of one of the Principals who attend these fiestas.

The movements of the hands accompany the voices, so that with the right they go along forming

half moons, and in the left some small boxes of little shells, which serve them

as castanets. This is in such perfect time and so well done that it causes no

little admiration to see the liveliness with which they learn the things to

which they apply themselves. Of their customs I shall not omit saying that although they were

given the name of Ladrones because of some little stealth of iron, which they

must have done on our ships, they do not deserve it, for all the houses being open,

rarely is anything missing from them. The young men, who are called Urritaos

are very indecent and live in public houses with the unmarried women, whom they buy or

rent from their parents for two or three hoops of iron, and some number of

tortoise shells. This does not hinder them from marrying later. The married ones

ordinarily content themselves with one woman and do not disturb the others.

They abhor assassins; and because of this they did not honor as they usually did, some of

the villages of the island of Saipan, because they have found them for several

years back cruel, and very inclined to make lances. They are liberal and kind to visitors,

as has been experienced byour ships upon passing through their lands, and much

more by those who landed there, thrown up by the shipwreck of the Concepcion. In

conclusion, although their customs generally are like those of blind people,

they are not so barbaric, as are their barbarisms, and like that of other nations.

CHAPTER II

Their Religion and Government

Of their religion and government, I do not know what to say: but I shall say

they are people without God, without a king, without law, and without any kind

of civil police. Neither the islands together, nor the villages in particular, have

heads which govern the others; only the Principals like sovereign princes

forming in each village a kind of republic, in which opinions are exchanged, but each one does as he wishes

if no stronger man prevents it. In each family the head is the father or elder relative but with limited influence. A son as he grows up neither fears nor

respects his father, as the animals do, he has but a place to go where they

feed him. In the home it is the woman who rules and her husband does not dare give an order

contrary to her wishes, nor punish the children, because if the woman feels

offended,

she will either beat the husband or leave him. Then if the wife leaves the

house all the children go with her, knowing no other father than the next

husband their mother may select.

They have no laws whatever. Individual choice governs the behavior of each one.

Transgressions are punished by war if they are of the crowd; by hatred if they

are of the individual. Nevertheless, any custom long in use has the enforcement of a

law. They do not have many wives nor do they marry relatives, if one call

marriage that which might better be called concubinage for its lack of perpetuity, for they

may separate and take another husband or wife at any trifling quarrel. However

if a man abandons his wife it costs him a great deal, for he loses both his property and

his children. Women can leave their men without inconvenience, and do so

frequently through jealousy and suspecting their husbands of disloyalty, punish them in

many ways. Sometimes the woman calls a meeting of all the women of the village,

who wearing hats and armed with spears and lances, go to the house of the

adulterer, and if he has growing crops, they destroy them. They make him come

out of the house and threaten to run him through with their lances, at last driving him

away. At other times the offended wife punished her husband by leaving him.

Then her relatives go to the husband's house and carry away everything of value, not

even leaving him a spear or a mat on which to sleep. They leave nothing more

than the mere shell of the house and sometimes they destroy even that. If a woman is

untrue to her husband the latter may kill her lover, but the woman receives no punishment.

Their belief is, like their government, full of errors and blindness. They were

of the opinion that they were the only people in the world and that there was

no other land than their own. But after they had seen our ships passing and those of the

Dutch, they were convinced that there must be many other lands and other races.

From this they fell into another error, incorporating in their traditions the belief that

all other lands and other men sprung from a single bit of land, which was the

island of Guam, and that it was at first a man, then it became stone and from it issued all

mankind, and from Guam men were over the earth, to Spain and other countries.

They add that as the people went away from the country of their origin, they forgot

their mother tongue, and that people of other nations now know no language at

all but jabber like lunatics, not even understanding each other. They contend that all people

other than themselves are ignorant since their language makes no sense. They affirm

that our ships, in passing their territory brought rats, flies, mosquitoes and all

kinds of infirmities. And they prove their statements about diseases, because

after ships have been in their islands they all have colds and other attacks; but the reason is

being that eager as they are for iron and other things, while the ships are in

port they never

leave the shore, staying out day and night, in the sun or in inclement weather.

They are continually shouting, which makes them return home hoarse and with

other ailments.

Regarding the creation of the world, they say that Puntan (who must have been

the first man, driven by a storm was cast up on this island), was a very

ingenious man who lived many years in an imaginary place which existed before

earth and sky were made. This good man being about to die, taking pity on

mankind who would be left without a place in which to live and without sustenance, called his sister

who, like himself, had been born without father or mother. Making known to her

the benefit he wished to confer to mankind, he gave her all his powers so that

when he died she could create from his breast and back the earth and sky; from

his eyes the sun and moon, a rainbow from his eyebrows, and thus adjust

everything else not without some balance between the lesser and the greater in

the world as the poets do. Only that in this case it did not remain as mere

symbolic poetry but became for them scripture and gospel. This they sung in

their poor verses and they know it by heart, but with all this, there is no one who renders Puntan or his

sister any worship or visible ceremony, invocation or recourse that would

indicate that they are recognized as divinities. These and other old tales they sing at their

feasts, those who are the best singers gambling on who can sing the most

verses. They recognize immortality of the soul, and speak of hell and of a paradise, to

which go the souls of men for no other merit nor demerit that that of whether

they have died a natural or a violent death. Those who die of violence they

say, go to the inferno or zazarraguan, or the house of Chayfi, who is the

devil, and has a cauldron in which he cooks them, stirring them continually.

Those who die a natural death go to another place under the earth, which is

their paradise, where there are bananas, coconuts, sugar cane and other fruits of the earth. There is not found among

them either sect or shadow of religion, nor priests of any kind. there are only

some impostors who set themselves up as prophets, called Macanas, who promise

health, water, fish, and similar benefits by invoking the dead whose skulls

they keep in their houses with no altar, niche, or ornament except a basket in which they

are left about the house, forgotten until the time comes when the Macanas want

to ask for some favor. But recently, I believe because of an idolatrous Chinese

lady who was cast up here in a storm, and of whom we shall speak later on, some

have now a kind of veneration for the skulls and bones of the defunct, and they carve and

paint them on the bark of the trees and blocks of wood. The Macanas, like all

the Bonzos or priests of India, look out for their own interests of the living in

the invocation of the dead, of whom they know and almost all know, nothing can

be expected; and if they invoke the dead honestly it is not to obtain favors but

to placate them so they will do them no harm. Because the devil, in order to

maintain this respect and servile fear, is accustomed to appear to them in the forms of their

parents and ancestors to frighten and mistreat them. This is the most that

Satan has been able to do to these poor Marianos. There are no temples nor

sacrifices, no idols or profession of any sect whatever, a thing that will

facilitate greatly the introduction of the Faith, for it is easier to introduce

a religion where there is none than to cast one out in order to introduce

another. With all this, the Marianos have certain superstitions, especially

when they are fishing, at which time they observe silence and great abstinence,

either for fear of, or to flatter, the Anites, which are the souls of their

grandparents so they will not punish them by keeping the fish away or by

frightening them in their dreams of which they are very credulous. some, when a

man is about to die, place a basket at this head as if inviting him to remain

with them in the basket instead of the body he has inhabited, and to show him

that he will have a place to stay whenever he returns from the other world to

pay them a visit. Others, after anointing a corpse with fragrant oil, carry it

about to the homes of relatives, in order that the soul may remain in whichever

house it chooses, or that it may, when it returns to visit them, find refuge in

the house of its choice. Then demonstrations of grief at funerals are very

singular, many tears, fasting and a great sounding of shells. Weeping

customarily continues for six or eight days, according to their affections or

obligation towards the departed. They spend this time singing lugubrious songs,

giving parties around the catafalque crested on the sepulcher or next to it,

adorned with flowers, palms, shells and other things they consider suitable.

The mother of the dead man cuts off a lock of his hair and keeps it as a

memento, and counts the days after his death by tying a knot each night in a

cord which she wears around her neck. Their demonstrations are much greater

when one of their Principals or Chamorris dies.....

THE LIFE AND MARTYRDOM OF THE VENERABLE FATHER DIEGO LUIS DE SANVITORES

by Francisco Garcia, S.J.

Translation by

FELICIA PLAZA, M.M.B.

Micronesian Area Research Center, U.O.G. 1980

BOOK III

Blessed Diego Luis de San

Vitores Church

884 Pale San Vitores Road

Tumon Bay, Guam USA 96911-4013

Beato Diego Luis de San Vitores Gesuita, martire

nelle Marianne

Burgos, Spagna, 12 novembre 1627 - Tomhom, Guam

(Marianne), 2 aprile 1672

Martirologio Romano: Nel villaggio di Tomhom

nell’isola di Guam in Oceania, beati martiri Diego Luigi de San Vitores,

sacerdote della Compagnia di Gesù, e Pietro Calungsod, catechista, uccisi

crudelmente in odio alla fede cristiana e precipitati in mare da alcuni

apostati e da alcuni indigeni seguaci di superstizioni pagane.

È considerato l’Apostolo delle Isole Marianne,

nell’Oceano Pacifico. Padre Diego Luis nacque nella nobile famiglia de San

Vitores, a Burgos in Spagna il 12 novembre 1627.

Per gli alti incarichi affidati dalla corte al padre

di Diego, la sua famiglia si trasferì a Madrid nel 1631, poi a Guadix (Granada)

nel 1635 e di nuovo a Madrid nel 1638. Frequentò il Collegio dei Gesuiti di

Madrid e giovanissimo entrò come novizio nella Compagnia di Gesù a Villarejo de

Fuentes; nel 1634 a 17 anni emise i primi voti; fino al 1650 compì gli studi di

filosofia e di teologia, venendo ordinato sacerdote il 23 dicembre 1651.

Fino al 1660 fu insegnante a Oropesa (Toledo), Madrid

e Alcalà e in quell’anno finalmente poté realizzare il sogno della giovinezza e

partire per le missioni, aveva 33 anni e così fu destinato, non in Cina come

desiderava, ma alle Filippine, dove giunse via Messico, solo nel 1662.

In Messico stazionò per due anni dal 1660 al 1662,

conquistandosi la stima dei confratelli missionari, rammaricati per la sua

partenza da Acapulco; fu durante il viaggio marittimo dal Messico alle

Filippine, che Diego ebbe un primo contatto con le Isole Marianne, allora

chiamate Ladroni, nome messo da Magellano che le scoprì nel 1521; rendendosi

conto che l’arcipelago non conosceva ancora l’evangelizzazione.

Perciò scrisse sia a Roma che in Spagna, a cui

appartenevano, sollecitando l’invio di missionari nelle Isole e a Guam

capoluogo, offrendo sé stesso per tale scopo. Il 10 luglio 1662 giunse al porto

di Lampong nelle Filippine da dove proseguì, via terra per Manila.

Fino al 1667 svolse la sua missione sacerdotale nella

Comunità di Taytay e poi come prefetto degli studi nel collegio di Manila. Nel

1665 giunse la disposizione del re di Spagna al governatore delle Filippine, di

provvedere per un’imbarcazione al missionario e il 7 agosto 1667 padre Diego

Luis de San Vitores, poté salpare non per le Marianne, ma per il Messico,

diretto dal viceré di Spagna, che avrebbe dovuto fornirgli il materiale ed i

mezzi necessari per avviare la missione, perché il governatore delle Filippine

non aveva denaro per lo scopo.

Dopo tre mesi di sosta in Messico per raccogliere i

fondi, il 23 marzo 1668 salpò per le Marianne, dove giunse nell’isola di Guam

il 16 giugno 1668, accompagnato da un gruppo di confratelli gesuiti.

L’opera di evangelizzazione si propagò fra alti e

bassi in tutto l’arcipelago, le conversioni affluirono numerose, nel contempo

si ergeva una opposizione alla loro opera, da parte di un guaritore cinese, un

certo Cocho, che sobillava gli indigeni cristiani, dicendo che l’acqua del

battesimo era avvelenata e perciò i bambini morivano; in realtà alcuni bambini

già gravemente ammalati erano stati battezzati e poi erano morti.

Ma questo bastò perché molti che si erano convertiti,

si rivoltassero contro i missionari, diventando loro nemici. L’evangelizzazione

delle Isole Ladroni poi Marianne, da parte di padre Diego, durò quattro anni,

con frequenti spostamenti da un’isola all’altra per sostenere i suoi

confratelli e con generosa dedizione alla gente dell’arcipelago.

Accompagnato dal giovane catechista filippino Pedro

Calungsod, il 2 aprile 1672 si recò al villaggio di Tomhom nell’isola di Guam e

avendo saputo che era nata una bambina al cristiano poi rinnegato, di nome

Matapang, cercò di convincerlo a battezzarla, l’uomo reagì con violenza,

rifiutò e recandosi al villaggio, cercò l’aiuto di un certo Hirao per

ucciderli; anche quest’ultimo era un beneficiario della bontà dei missionari e

in un primo momento rifiutò.

Nel frattempo, con il consenso della madre, padre

Diego battezzò la bambina; avendolo saputo, si scatenò l’ira di Matapang che

lanciò varie frecce, finché colpì al petto il giovane catechista Pedro, padre

Diego accorse per dargli l’assoluzione, nel frattempo sopraggiunse Hirao che

con un colpo alla testa finì il giovane e con la lancia uccise poi padre Diego.

I loro corpi spogliati e caricati su una barca, furono

gettati nell’Oceano. Primi martiri e apostoli delle Marianne. Padre Diego Luis

de San Vitores è stato beatificato il 6 ottobre 1985 da papa Giovanni Paolo II,

il quale ha poi beatificato Pedro Calungsod Bissaja il 5 marzo 2002. - Festa

liturgica per entrambi al 2 aprile.

Autore: Antonio Borrelli

OMELIA DI GIOVANNI PAOLO

II

Domenica, 6 ottobre 1985

1. “Ecco, sto alla porta

e busso” (Ap 3, 20).

Gesù Cristo, “il

testimone fedele e verace, il principio della creazione di Dio” (Ap 3, 14)

sta alla porta e bussa.

Gesù Cristo, colui

che il Padre, ha consacrato con l’unzione e ho mandato a portare il lieto

annunzio, a fasciare le piaghe dei cuori spezzati, a proclamare la libertà . .

.” (Is 61, 1).

Gesù Cristo, il

vero chicco di grano che, caduto in terra, è morto e produce molto

frutto (cf. Gv 12, 24).

Oggi anche noi siamo

chiamati a essere testimoni di questo frutto.

2. Gesù Cristo. Tutte le

letture dell’odierna liturgia parlano direttamente di lui, della sua persona e

del suo mistero.

Ecco, egli si è fermato

alla porta di quell’uomo, il cui nome era Ignazio di Loyola, e ha bussato

al suo cuore. Tutti ricordiamo quel bussare. La sua eco continua a risuonare

tuttora nella Chiesa diffusa nei cinque continenti.

Gesù Cristo, il testimone

fedele e verace. Un frutto di questa testimonianza fu l’uomo

nuovo nella storia di Ignazio di Loyola. E, in seguito, fu una grande

comunità nuova, la “Societas Iesu”, la Compagnia di Gesù.

Oggi siamo invitati a

ricordare i frutti dati da questa comunità nel corso di oltre quattro

secoli; con le opere nel campo dell’apostolato, delle missioni, della scienza,

dell’educazione, della pastorale.

Soprattutto i frutti

dovuti alla santità della vita dei figli spirituali del Santo di Loyola.

Oggi tra coloro che la

Chiesa ha elevato alla gloria degli altari, vengono aggiunti i tre servi

di Dio: Diego Luis de San Vitores, José María Rubio y Peralta e Francisco

Gárate.

3. I tre nuovi beati

nacquero in Spagna, nazione che tanto si è distinta nella diffusione del

Vangelo oltre che per la vitalità della sua fede cattolica.

Diverse diocesi e città

si onorano di avere dei vincoli con questi eletti del Signore: Burgos è la

città natale di padre San Vitores, l’evangelizzatore delle Isole Marianne;

padre Rubio nacque a Dalias (Almería) ed esercitò il suo apostolato soprattutto

nella capitale spagnola, restando noto come “l’apostolo di Madrid”; fratello

Gárate è originario di un villaggio nelle immediate vicinanze della città di

Loyola, parrocchia di Azpeitia (Guipúzcoa) e trascorse la maggior parte della

sua vita a Deusto (Bilbao).

Qual è il messaggio di

questi tre beati all’uomo d’oggi?

Se pensiamo ai principi

più profondi delle loro vite vediamo che questi tre modelli di santità sono

come uniti da un elemento comune: l’apertura totale e generosa a Dio che

dice loro: “Ecco, io sto alla porta e busso: se uno sente la mia voce e mi

apre, io entrerò da lui e cenerò con lui, e lui con me” (Ap 3, 20).

“Apriamo la nostra porta per riceverlo quando, sentendo la sua voce, diamo

liberamente il nostro assenso ai suoi inviti manifesti o velati e applichiamoci

con impegno ai compiti che egli ci confida” (Venerabile Beda, Omelia 21).

Effettivamente la

risposta dei tre beati subitanea e generosa alla chiamata di Dio unisce aspetti

diversi, ma allo stesso tempo complementari, della loro vocazione religiosa

vissuta come membri della Compagnia di Gesù.

4. Diego Luis de San

Vitores Alonso, ancora molto giovane, sente interiormente una voce che lo

attrae e insieme lo muove. Si sente attratto da Cristo, l’eterno inviato dal

Padre per salvare gli uomini, che lo spinge ad andare in terre lontane come

strumento della sua missione di salvezza. Risuonano nelle orecchie di Diego le

parole del Signore nella sinagoga di Nazaret: “Evangelizzare pauperibus misit me”

(Lc 4, 18; Is 61, 1). Gesù sta alla porta e chiama: la sua

voce si fa ogni volta più chiara e insistente nel cuore generoso del giovane,

che si apre a Dio e decide di entrare nella Compagnia di Gesù, rinunciando al

brillante avvenire che le sue doti personali e la posizione sociale della sua

famiglia gli avrebbero procurato.

Nella preghiera e nel

raccoglimento, la sua anima contempla “Gesù che percorreva città e villaggi

predicando il Vangelo del Regno” (Mt 9, 35), chiede al Signore la grazia

di non essere “sordo alla sua chiamata, ma pronto e diligente per fare la sua

santissima volontà” (S. Ignazio di Loyola, Esercizi Spirituali, 91). Il

giovane religioso bussa alla porta dei suoi superiori perché lo inviino alle

missioni dell’Oriente, per predicare la buona novella di Cristo ai popoli che

ancora non lo conoscono.

Dopo un lungo e faticoso

viaggio verso l’Oriente, via Messico, giunse nelle Filippine, dove rimase per

cinque anni prima di essere inviato alle Isole Marianne. Nel giugno del 1668 il

padre San Vitores e i suoi compagni gesuiti raggiunsero l’arcipelago e si

stabilirono nell’isola di Guam, il centro della loro attività missionaria.

Il loro zelo apostolico e

la completa dedizione nei confronti di quelle popolazioni bisognose di una

promozione spirituale e umana, caratterizzarono gli anni di questo esemplare

missionario, che, imitando le parole del maestro - “nessuno ha amore più grande

di colui che sacrifica la propria vita per i suoi amici” (Gv 15, 13) -

versò il suo sangue in sacrificio, mentre chiedeva a Dio di dimenticare il nome

del responsabile della sua morte.

La vita di questo nuovo

beato si caratterizzò per una totale disponibilità ad accorrere là

dove Dio lo chiamava. Egli parla in tono attuale e urgente ai missionari di

oggi sull’atteggiamento aperto e preparato per rispondere alle esigenze

del mandato: “Andate per tutto il mondo e predicate il Vangelo a ogni creatura”

(Mc 16, 15).

Giovani che mi ascoltate,

o che riceverete questo messaggio: aprite il vostro cuore al Signore che

sta alla porta e chiama (cf. Ap 3, 20). Siate generosi come il

giovane Diego, che lasciando tutto si fece pellegrino e missionario in terre

lontane per dare testimonianza dell’amore di Dio per gli uomini.

5. José María Rubio

y Peralta, “l’apostolo di Madrid”. La sua vita di fedele seguace di Cristo ci

insegna che è l’atteggiamento docile e umile nei confronti dell’operare di Dio

ciò che fa progredire il cristiano sul cammino della perfezione e lo converte

in uno strumento di salvezza.

Sapete tutti come padre

Rubio esercitò dal confessionale e dal pulpito una grande attività apostolica.

Il suo squisito tatto di guida di anime gli faceva trovare il consiglio

adeguato, la parola giusta, la penitenza, a volte esigente, che durante gli

anni di paziente e silenziosa opera, crearono via via apostoli, uomini e donne

di ogni classe sociale, che divennero in molti casi suoi collaboratori nelle

opere assistenziali e di carità, da lui ispirate e dirette. Formò secolari

impegnati, ai quali amava ripetere la sua nota frase: “Bisogna avere slancio!”,

animandoli a farsi presenti come cristiani negli ambienti poveri ed emarginati

della periferia di Madri dagli inizi del secolo, dove egli creò scuole e si

prese cura dei malati, degli anziani e degli operai disoccupati.

Il suo dialogo assiduo

con Cristo, soprattutto nel sacramento dell’Eucaristia, e la sua devozione al

Sacro Cuore lo portarono all’intimità con il Signore e ai suoi stessi

sentimenti (cf. Fil 2, 5 ss.). Nell’esemplare traiettoria della sua

vita, questo illustre figlio di Sant’Ignazio si presenta all’uomo d’oggi come

un autentico “alter Christus”, un sacerdote che guarda il popolo dal punto di

vista di Dio e che per far ciò ha la virtù di comunicare al prossimo qualcosa

che è riservato a coloro che vivono in Cristo.

6. Il messaggio di

santità che il fratello Francisco Gárate Aranguren ci ha inviato è

semplice e chiaro, come fu semplice la sua vita di religioso sacrificato nella

portineria di un centro universitario di Duesto. Fin dalla giovinezza

Francisco spalancò il suo cuore a Cristo che batteva alla sua porta

invitandolo ad essere suo seguace fedele, suo amico. Come la Vergine Maria, che

amò teneramente come madre, rispose con generosità e fiducia senza limiti, alla

chiamata della grazia.

Fratello Gárate visse la

sua consacrazione religiosa come apertura radicale a Dio, al cui servizio e

gloria si offrì (cf. Lumen

gentium, 44) e da cui riceveva ispirazione e forza per dare testimonianza

di una grande bontà con tutti. Questo lo poterono confermare tante e tante

persone che passarono per la portineria del cosiddetto, affettuosamente,

“Fratello Delicatezze”, presso l’Università di Deusto: studenti, professori,

impiegati, padri dei giovani residenti, gente insomma di tutte le classi e le

condizioni, che notarono nel fratello Gárate la disposizione totale e

sorridente di chi ha il suo cuore legato a Dio.

Costui ci dà una testimonianza

concreta e attuale del valore della vita interiore come anima di

ogni forma di apostolato oltre che della consacrazione religiosa. In

verità quando ci si sta offrendo a Dio e si concentra in lui la propria vita, i

frutti apostolici non si fanno aspettare. Dalla portineria di una casa di

studi, questo fratello coadiutore gesuita rese presente la bontà di Dio

mediante la forza evangelizzatrice del suo servizio silenzioso e umile.

7. Che cosa dicono

alla Chiesa e al mondo attuale i tre beati che oggi esaltiamo e che la

liturgia chiama “querce di giustizia, piantate dal Signore per la sua gloria” (Is 61,

3)?

In epoche diverse, con

persone e in aree geografiche differenti, risposero prontamente all’invito di

Gesù che li chiamava all’intimità con lui. Con le loro vite

incentrate nell’amore di Dio, diedero, ciascuno a suo modo, testimonianza:

della disponibilità assoluta del missionario che giunge fino allo spargimento

di sangue, dell’opera paziente e delicata di guida delle coscienze e creatore

di apostoli, di servizio umile e silenzioso, nel compiere l’ufficio quotidiano.

8. Dirigiamo di nuovo il

nostro sguardo al “testimone fedele e verace” del libro dell’Apocalisse, che un

giorno si trattenne davanti alla porta di Ignazio di Loyola e chiamò. Attento

al passaggio del Signore, Ignazio gli aprì la porta del suo cuore. Con

questa risposta, il cuore di Gesù si convertì per lui in “fonte di vita e

santità”.

Oggi, come nei tempi

scorsi, la Chiesa eleva nuovamente all’onore dell’altare tre figli di

Sant’Ignazio. Che questo giorno solenne diventi in Gesù Cristo un nuovo

“principio della creazione di Dio” (Ap 3, 14). Che, in virtù di questo

“principio”, si rinnovi in ognuno dei membri della Compagnia di Gesù la

chiamata all’indivisibile servizio a Dio nella Chiesa e nel mondo, che il

vostro fondatore e padre espresse con quelle brevi parole: “Prendete, o

Signore, e ricevete tutta la mia libertà . . .” (S. Ignazio di Loyola, Esercizi

Spirituali, 234).

I nomi dei gesuiti Diego

Luis de San Vitores Alonso, José Maria Rubio y Peralta e Francisco Gárate

Aranguren, vengono oggi a sommarsi alla lunga e feconda storia di santità di

questa benemerita famiglia religiosa. Costoro, come il chicco di grano che cade

a terra e muore, diedero molti frutti. furono fecondi perché Dio fu al centro

della loro vita.

Che in tutta la vostra

comunità ignaziana si ravvivi con nuova forza la chiamata alla santità di cui

sono alti esempi i nuovi beati che oggi la Chiesa celebra come figli

prediletti.

Che per intercessione di

Maria, regina di tutti i santi, alla cui attenzione materna affido l’eredità di

santità con cui lo Spirito ci ha arricchiti, siano sempre più abbondanti i

frutti di pienezza di vita cristiana nella Chiesa.

© Copyright 1985 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana