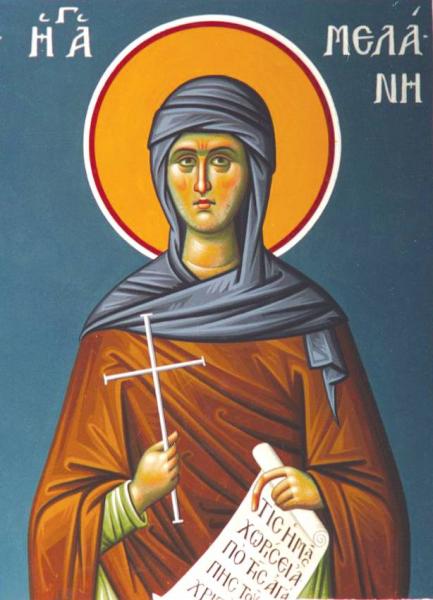

Sainte Mélanie la Jeune

Fondatrice de monastères,

recluse au mont des Oliviers (+ 439)

A quatorze ans, cette

jeune aristocrate romaine épousa son cousin Pinien qui en avait dix-sept. Dix ans

plus tard, ils perdirent leurs deux enfants et décident d'un commun accord de

suivre les conseils évangéliques. Riches, ils liquident tous leurs biens et

quittent Rome peu avant qu'Alaric vienne la piller. Ils se retirent d'abord en

Sicile puis à Thagaste dont le diocèse a pour pasteur un ami et voisin, saint

Augustin, évêque d'Hippone. Ils y amènent avec eux quinze eunuques et autant de

servantes. Toutes les terres de Thagaste leur appartiennent. Les fidèles

veulent que Pinien soit leur évêque, car ce serait la fortune assurée pour la

communauté chrétienne. Mais Pinien et Mélanie s'en vont à Jérusalem. Pinien y

meurt en 440 (ou 432), Mélanie fonde un monastère non loin du lieu de

l'Ascension, sur le Mont des Oliviers. Elle y meurt, de retour de la fête de

Noël à Bethléem.

À Jérusalem, sainte

Mélanie la Jeune, qui, avec son époux, saint Pinien, quitta la ville de Rome,

se rendit dans la Ville sainte et y mena la vie religieuse parmi les femmes

consacrées à Dieu, tandis que son mari en faisait de même parmi les moines:

tous deux firent une sainte mort elle en 439, lui en 440.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/337/Sainte-Melanie-la-Jeune.html

Le 31 décembre, clôture

de la Nativité et mémoire de notre vénérable Mère Mélanie la Romaine

Au moment où l'Eglise

prenait rang parmi les institutions officielles de l'empire romain, certaines

dames de la haute aristocratie de Rome, conquises par les récits des exploits

ascétiques des moines d'Egypte et par les exhortations enflammées de Saint Jérôme [1],

renoncèrent aux vanités du monde pour embrasser la voie étroite qui mène au

Royaume des cieux. Saintes Asella, Fabiola, Marcelle, Sainte Paule et sa fille

Eustochium, Sainte Métanie l'Ancienne et sa petite-fille Mélanie la Jeune dont

nous célébrons la mémoire le 31 décembre [2],

ont toutes abandonné richesses, gloire et vie délicate pour se consacrer aux

oeuvres de bienfaisance et aux travaux de l'ascèse, soit à Rome même, soit en

Terre Sainte.

Née en 383, Valéria

Mélania dut épouser contre son gré un de ses proches parents, Pinien, alors

qu'elle avait à peine quatorze ans. Sitôt la cérémonie des noces achevée elle

proposa à son jeune époux de vivre dans la continence ; celui-ci résista un peu

et proposa d'assurer d'abord leur postérité en ayant deux enfants et de

renoncer ensuite ensemble au monde. Il leur naquit d'abord une fille, qu'ils

consacrèrent à Dieu immédiatement. Tout en gardant les apparences de la vie

mondaine d'une riche aristocrate, la jeune Mélanie commençait pourtant à porter

un tissu rugueux sous ses robes de soie et à mener en secret une vie de

mortification. En 403, elle mit prématurément au monde un fils qui mourut peu

après, et elle n'échappa elle-même à la mort qu'après avoir fait jurer à son

époux de ne pas différer davantage son désir. Sa grand-mère, Mélanie

l'Ancienne, était revenue d'Orient l'année précédente, au bout de trente-sept

ans d'absence, pour la soutenir et encourager sa sainte résolution. Finalement

libérés de toute attache à la suite de la mort de leur fille et du père de

Pinien les deux époux quittèrent leur somptueuse demeure pour se retirer dans

une de leurs propriétés des environs de Rome et se consacrer aux soins des

voyageurs et au secours des malades et des prisonniers. Mélanie confectionna

elle-même une grossière tunique pour Pinien, et, méditant l'exemple de Celui

qui, de riche qu'Il était en Sa divinité, s'est fait pauvre et a assumé notre

nature misérable afin de l'enrichir par Sa pauvreté (cf. II Cor. 8, 9), elle

s'employa à liquider son immense fortune; car Pinien et elle avaient vu en rêve

qu'il leur faudrait franchir un mur élevé avant de passer par une porte étroite

pour parvenir au Royaume de Cieux. Mais la tâche n'était pas si aisée : leurs

propriétés s'étendaient dans tout l'empire, de la Bretagne à l'Afrique et de

l'Espagne à l'Italie, leurs demeures étaient si splendides que seul l'empereur

pouvait en être l'acquéreur. La distribution de telles richesses remettait en

question l'économie même de l'état, et certains de leurs parents, membres

influents du Sénat, faisaient tout pour les empêcher de réaliser leur projet.

Toutefois, grâce à l'intervention de l'impératrice, Mélanie commença par

affranchir 8000 de ses esclaves, en donnant à chacun trois pièces d'or ; puis,

par l'intermédiaires d'hommes de confiance, elle fit couler des flots-d'or

d'Occident en Orient: églises et monastères furent fondés un peu partout; or,

pierreries, vaisselles et tissus précieux furent consacrés au Service Divin ;

des territoires entiers furent cédés à l'Eglise ou le produit de leur vente

distribué en aumônes. Les Goths d'Alaric ayant pris Rome en 410 et semant

partout la terreur en Italie, les deux époux passèrent en Sicile avec soixante

vierges et trente moines, puis de là en Afrique du Nord, où ils achevèrent la

liquidation de leurs biens en fondant des monastères et en portant secours aux

victimes de l'invasion barbare.

« Si tu veux être parfait, va, vends ce que tu possèdes et donne-le

aux pauvres, et tu auras un trésor dans les cieux, puis viens et

suis-moi » (Mat. 19, 21). Contrairement au jeune homme riche de

l'Evangile, Mélanie se dépouilla avec joie de tout pour suivre le Seigneur. Dès

lors libérée, elle s'engagea dans l'arène de l'ascèse. Âgée d'à peine trente

ans, l'amour de Dieu brûlait si fort en elle qu'elle se soumit à une discipline

digne des plus rudes combattants du désert, sans s'accorder aucun

accommodement, sous prétexte des habitudes délicates acquises depuis sa

jeunesse. Elle portait toujours sur elle un cilice rugueux, et, après un

entraînement progressif, elle passa toute sa vie dans le jeûne complet cinq

jours par semaine, ne prenant une sobre réfection que le samedi et le dimanche.

Ce n'est que sur les instances de sa mère, Albine, qui l'accompagnait partout,

qu'elle consentit à prendre un peu d'huile les trois jours qui suivent la fête

de Pâques. Elle trouvait tous ses délices dans la méditation de l'Ecriture, des

vies des Saints et des oeuvres des Pères de l'Eglise, qu'elle lisait en latin

et en grec. Après un bref repos de deux heures, elle veillait en prière toutes

les nuits et enseignait aux vierges qui l'avaient suivie à joindre la veille et

l'attente ardente de l'Epoux à la chasteté. Malgré son désir croissant de ne

vivre que pour Dieu et de consacrer tout son temps à la prière sans

distraction, elle ne pouvait se retirer à cause de ses nombreuses obligations,

aussi trouva-t-elle la solution en consacrant ses journées à la charité et à la

direction de ses disciples, et en réservant ses nuits pour Dieu seul, en

s'enfermant dans une sorte de coffre, où elle ne pouvait même pas s'allonger.

Aux assauts du démon de la vaine gloire, elle répliquait avec une méprisante

ironie et cultivait envers tous un tel esprit de douceur qu'à la veille de sa

mort elle pouvait dire qu'elle ne s'était jamais endormie avec une pensée de

rancune.

Au bout de sept ans en Afrique, elle partit pour un pèlerinage en Terre Sainte

avec sa mère et son époux, devenu son frère spirituel, en s'arrêtant à

Alexandrie pour rendre visite à Saint Cyrille. A Jérusalem, elle passait toutes

ses journées dans la basilique de la Résurrection et, quand on fermait les

portes au coucher du soleil, elle se rendait au Golgotha pour y passer la nuit.

Après un nouveau voyage en Egypte, auprès des Saints solitaires des déserts de

Nitrie, elle s'installa sur le Mont des Oliviers dans une petite cellule en

planches, que sa mère avait faite construire en son absence. Elle y demeura

pendant quatorze ans (417-431). Chaque Carême, de la Théophanie à Pâques, elle

s'y enfermait strictement, revêtue d'un cilice et couchant sur la cendre, et

n'y recevait que sa mère, Pinien et sa jeune cousine Paule, fille de Sainte

Paule. Cette austère réclusion ne l'empêchait pas pour autant de porter son

attention sur la vie de l'Eglise.

Elle nourrissait un zèle ardent pour la Foi Orthodoxe et s'opposa avec force

aux partisans de Pélage qui donnait une trop grande part au libre arbitre de

l'homme, en suivant l'enseignement de Saint Jérôme, rencontré à Béthléem, et de

Saint Augustin qui lui portait une grande admiration et lui avait dédié son

ouvrage Sur la Grâce du Christ et le péché originel (418).

A la mort de sa mère, en 431, Mélanie sortit de sa réclusion et fonda sur le

Mont des oliviers un monastère suivant les usages liturgiques de Rome, qui fut

bientôt peuplé de quatre-vingt-dix vierges, grâce à la diligence de Pinien.

Dans son extrême humilité, la Sainte refusa d'en assurer la direction ; elle

nomma une autre supérieure et se contenta de leur délivrer un enseignement

spirituel, tant par ses paroles que par l'exemple de sa conduite. Comme le

Seigneur, elle se faisait la servante de toutes, venait soulager en secret les

soeurs malades et prenait sur elle les besognes les plus répugnantes. Elle leur

enseignait à sanctifier leur âme et leur corps par la sainte virginité, leur

recommandait sans relâche d'user de la sainte violence recommandée par le

Seigneur (Mat. 11, 12) pour renoncer à leur volonté propre et fonder le temple

spirituel des vertus sur l'obéissance. En prenant des exemples dans la vie des

Pères, elle les exhortait à la persévérance dans le combat spirituel, à la

vigilance contre les pièges du malin, au zèle et à la concentration de

l'intelligence dans la prière nocturne, et surtout à la charité. « Toutes

vertus et toutes ascèses sont vaines sans la charité, disait-elle. Le diable

peut aisément imiter toutes nos vertus, il est vaincu seulement par l'humilité,

et la charité ». Son frère spirituel Pinien mourut à son tour en 432. Elle

le fit ensevelir avec Albine, près de la grotte où le Christ avait prédit à ses

disciples la ruine de Jérusalem, et demeura là pendant quatre ans, dans une

cellule sans ouverture, complètement isolée du monde; puis elle chargea son

disciple et biographe, le Prêtre Gérontios, d'y installer un monastère

d'hommes, dont elle assura aussi la direction spirituelle - cas exceptionnel

dans l'histoire de l'Eglise. Vers la fin de 436, elle se rendit à Constantinople

à la demande de son oncle, le puissant Volusien, qui était resté attardé dans

le paganisme. En arrivant, elle le trouva gravement malade et réussit, avec

l'aide du Saint Patriarche Proclus, à le décider de recevoir le Saint Baptême

avant de mourir. Ayant trouvé la capitale agitée par les querelles concernant

la doctrine hérétique de Nestorius, elle fit campagne pour le Dogme Orthodoxe

avant de regagner en hâte son Monastère du Mont des Oliviers. L'année suivante,

l'impératrice Eudocie entreprit un pèlerinage en Terre Sainte sur les

recommandations de Sainte Mélanie, avec qui elle avait sympathisé à

Constantinople et qu'elle considérait comme sa mère spirituelle. Outre son

enseignement et le spectacle édifiant de sa communauté, la souveraine lui

demanda ses conseils avisés pour les nombreuses fondations et riches donations

qu'elle fit alors aux Eglises et aux Monastères.

Dieu accordait sans retard à sa servante les guérisons qu'elle lui demandait;

mais, avertie des pièges du démon de la vaine gloire, Mélanie donnait toujours

à ceux qui venaient demander son intercession soit de l'huile tirée des

veilleuses placées au-dessus des tombeaux des Martyrs, soit quelque objet ayant

appartenu à un saint personnage, de sorte qu'on ne crût pas que la guérison

était due à sa propre vertu.

Après avoir menée une telle course, constamment tendue en avant à la poursuite

de l'Epoux céleste, elle n'avait plus pour désir que d'être déliée de cette vie

pour être avec le Christ (Phil. 1, 23). Tombée malade en fêtant la Nativité à

Bethléem (439), elle rassembla ses religieuses dès son retour à Jérusalem pour

leur délivrer son testament spirituel. Elle les assura qu'elle serait toujours

invisiblement présente parmi elles, à condition qu'elles restent fidèles à ses

prescriptions et qu'elles gardent avec crainte de Dieu leurs lampes allumées,

telles des vierges sages (Mat. 25, 1-13), dans l'attente de la venue du

Seigneur. Au bout de six jours de maladie, elle fit ses dernières

recommandations aux moines et désigna Gérontios comme supérieur et père

spirituel des deux communautés, puis elle s'endormit doucement, avec une joie

confiante, en prononçant ces paroles: « Comme il a plu au Seigneur, voilà

ce qui est advenu ». Des moines venus des monastères, des déserts et de

toutes les extrémités de la Palestine célébrèrent une vigile de toute la nuit

et, au moment de l'ensevelir, au petit matin, les uns et les autres la

recouvrirent de vêtements, ceintures, cuculles et de maints autres objets

qu'ils avaient reçus en bénédiction de la part de saints personnages. Le

monastère de Sainte Mélanie fut détruit en 614, lors de l'invasion perse, mais

on vénère encore sa grotte au Mont des Oliviers.

NOTES:

[1]

Saint Jérôme quitta la vie mondaine et intellectuelle de la capitale pour se

faire moine et devenir l'ardent avocat de la vie ascétique. C'est à lui que

l'on doit la biographie de plusieurs de ces saintes femmes.

[2]

Ces saintes romaines ne sont pas commémorées par les synaxaires byzantins.

Sainte Asella († 385) est célébrée le 6 décembre en Occident, Sainte

Fabiola († 399), le 27 décembre, Sainte Paule et sa fille Eustochium, le

26 janvier, sainte Marcelle († 410) le 31 janvier, Sainte Mélanie

l'Ancienne n'est mentionnée ni par les martyrologes ni par les synaxaires, peut

être à cause de sa mésentente finale avec Saint Jérôme, mais elle est cependant

fort louée par Pallade (Histoire Lausiaque, chap. 46 et 54).

SOURCE : http://www.icones-grecques.com/textes/synaxaires-vies-de-saints/vie_melanie.htm

Фрагмент

икона «Св. Князь Михаил и Св. прп. Мелания».

MÉLANIE LA

JEUNE sainte (383-439)

Valeria Melania

appartenait à une très grande famille romaine. On l'appelle Mélanie la Jeune

pour la distinguer de sa grand mère, Mélanie l'Ancienne (350 env.-410). À

quatorze ans, elle fut mariée à Valerius Pinianus et eut de lui deux enfants,

qui moururent en bas âge ; les époux résolurent de quitter le monde et de

vivre dans l'ascèse, mais l'intervention de l'impératrice Serena fut nécessaire

pour leur permettre de liquider la plus grande partie de leur fabuleuse fortune.

Quand Rome fut prise par les Barbares en 410, Mélanie et son mari se

réfugièrent d'abord en Sicile, puis à Tagaste en Afrique du Nord. Les habitants

d'Hippone voulurent que leur évêque, Augustin, ordonnât prêtre Pinianus, afin

de s'assurer ses dons. Mécontents de ce projet, Pinianus et Mélanie partirent

pour la Palestine, où ils se retirèrent à Jérusalem, partageant

leur temps entre la prière, les œuvres charitables, l'étude de la Bible et des Pères. Mélanie y

fonda un monastère, dont cependant elle ne voulut pas être supérieure. Son mari

mourut vers 432.

En 436, elle se rendit à

Constantinople pour revoir son oncle Volusien, qui préparait le mariage de

l'empereur d'Occident Valentinien III avec Eudoxie, fille de l'empereur

d'Orient. Mélanie décida Volusien à recevoir le baptême et lutta pour

l'orthodoxie, attaquée par l'hérésie de Nestorius. Elle revint à Jérusalem

et y mourut.

Jacques DUBOIS,

« MÉLANIE LA JEUNE sainte (383-439) », Encyclopædia

Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 31 décembre 2015. URL

: http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/melanie-la-jeune/

SOURCE : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/melanie-la-jeune/

Мелания

Римляныня Младшая, Вифлеемская, Палестинская, прп. Миниатюра Минология Василия

II. Константинополь. 985 г. Ватиканская библиотека. Рим.

Saint Melania the Younger. Miniature from the Menologion of Basil II

Profile

Wealthy Roman patrician

noble; granddaughter of Saint Melania

the Elder. Married against

her will to Valerius

Pinianus (Saint Pinian)

at age 13. After the death of

their two children,

both of whom died young,

and to escape Visigoth invasion, the couple fled to Tagaste in North

Africa in 410 where

they had estates, and where they met Saint Augustine

of Hippo. Though they stayed married,

the two took vows of celibacy,

freed their slaves,

sold their lands and goods in Spain and Gaul, and

gave the proceeds to the poor.

They built two monasteries for Saint Augustine,

then the couple moved to Jerusalem and

entered a monastery and convent around 417.

Friend of Saint Paulinus

of Nola and Saint Jerome. Widowed in 432.

Directed the convent on

the Mount of Olives for several years.

Born

c.383

late December 439 at Jerusalem of

natural causes

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by Charles Schlitz

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Life of Saint Melania, by Cardinal Mariano

Rampolla del Tindaro

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

MLA

Citation

“Saint Melania the

Younger“. CatholicSaints.Info. 21 August 2020. Web. 31 December 2022. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-melania-the-younger/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-melania-the-younger/

Also

known as

Pinianus

Valerius Pinianus

Profile

Married to Saint Melania

the Younger. Father of

two; both children died very

young. About 410 the

couple left Rome, Italy, and

each entered religious

life. Monk.

c.438

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

MLA

Citation

“Saint Pinian“. CatholicSaints.Info.

12 April 2015. Web. 31 December 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-pinian/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-pinian/

St.

Melania the Younger

MELANIA the

Elder was of a most noble Spanish family, though descended of a Roman pedigree,

and a relation of St. Paulinus of Nola, second to no one in Aquitain and Spain

in riches or nobility. Being married young, she was left a widow at

twenty-three years of age. Upon the death of her husband she said to God: “Now,

O Lord, I shall be at liberty to devote myself without distraction to thy

service.” Having put her son Publicola into the hands of good tutors, she

embarked with Rufinus for Egypt in 371: and after spending six months in

visiting the monks of those parts, went into Palestine, but so much disguised,

that the governor of Jerusalem cast her into gaol for visiting certain

prisoners, till she made herself known to him, and then he treated her with the

greatest respect. After some time she built a monastery at Jerusalem, wore a

coarse habit, and had no other bed than a rough cloth spread on the floor,

without any other cover than a sackcloth. Thus she lived in Palestine

twenty-seven years, making prayer and the meditation of the holy scriptures her

principal employment. Her son Publicola grew up, and becoming most accomplished

in the necessary qualifications of mind and body, was married to Albina, by

whom he had two children, a son and a daughter, this latter being our saint.

She was married at thirteen years of age to Pinian, the son of Severus, who had

been prefect of Rome. Her children both died young, and by her moving

discourses and entreaties she gained his consent that they should bind

themselves by mutual vows to serve God in perpetual chastity. The elder

Melania, at this news, left the East, and returned to Rome, after having been

thirty-seven years absent. She was met at Naples by a train of the most

illustrious personages of the nobility of Rome, who attended her from thence

glittering in rich attire, and sumptuous equipages. The humble Melania

travelled at their head, meanly mounted on horseback, and clothed with coarse

and threadbare garments. During her stay in Rome it was her first care to

caution Pinian and her granddaughter against the heresies of that age. She

staid in the West four years, during which interval she took a journey into

Africa. There she received news of the death of her son Publicola. At her

return to Rome she advised Pinian and our saint to give what they possessed to

the poor, and to choose some remote retirement. This council they readily

embraced, and were imitated by Albina. Avita, a niece of Melania, after

converting her husband from the errors of idolatry, induced him to join her in

a vow of perpetual continency. Their son Asterius, and their daughter Eunomia,

followed the same example. All these fervent and illustrious persons went

together to pay a visit to St. Paulinus at Nola. So many wonderful conversions

astonished not only Rome, but all Christendom. The elder Melania had no sooner

completed this great work, but she hastened back to her dear solitude. The

tumult of Rome made that great city seem to her a place of exile, and a true

prison; nor was she able to bear the noise of the world, and the distraction of

visits. Rufinus accompanied her as far as Sicily, where he died. Melania

arrived at Jerusalem, distributed the residue of her money among the poor, and

shut herself up in a monastery. But exchanged this mortal life for a better,

forty days after, in the year 410, being about sixty-eight years old. Melania

the Elder seemed some time too warmly engaged with Rufinus in the defence of

Origen. The commendations which St. Austin, St. Paulinus, and others bestow on

her, bear evidence to her orthodoxy and her edifying virtue, though her name

has never been placed among the saints, unless she be meant on the 8th of June

in the manuscript calendar mentioned by Chiffletius, as Papebroke and Joseph

Assemmani 1 take

notice.

Albina,

Melania the Younger, and Pinian first made over their estates in Spain and

Gaul, reserving those which they possessed in Italy, Sicily, and Africa. They

made free eight thousand of their slaves, and those who would not accept of

their freedom, they gave to the brother of Melania. Their most precious

furniture they bestowed on churches and altars. Their first retreat was in

retired country places in Campania and Sicily, and their time they spent in

prayer, reading, and visiting the poor and the sick, in order to comfort and

relieve them. For this end they also sold their estates in Italy, and passed

into Africa, where they made some stay, first at Carthage, and afterwards at

Tagasté, under the direction of St. Alypius, who was at that time bishop of

this city. In a journey they made to Hippo, to see St. Austin, the people there

seized Pinian, demanding that St. Austin would ordain him priest; but he

escaped out of their hands, by promising that if he ever took holy orders, it

should be to serve their church. The poverty and austerity in which they lived

seven years at Tagasté appeared extreme. Melania by degrees arrived at such a

habit of long fasting, as often to eat only once a week, and to take nothing

but bread and water, except that on solemn occasions to her bread she added a

little oil. Their occupation was to read and copy good books; Pinian also

tilled his garden. In 417 they left Africa and went to Jerusalem, where they

continued the same manner of life. St. Melania buried her mother Albina in 433,

and her husband Pinian two years after. She survived him four years, shutting

herself up in a monastery of nuns, which she built and governed. Her cell was

her paradise; yet she left it to go to Constantinople, to convert her uncle

Volusian, who was an idolater, and she had the comfort to see him baptized, and

die full of hope and holy joy. After she had closed his eyes, she made haste

back to Jerusalem. She went to Bethlehem to pass Christmas-day at the holy

crib, and came back the day following; and found herself seized with her last

sickness, which she discovered to those about her. A great number of holy monks

and others visited her, whom she exhorted, and when she saw them weep, tenderly

comforted. She departed to our Lord in the year 439, the fifty-seventh of her

age, on a Sunday, which was the 31st of December, on which day her name stands

in the Roman Martyrology. See Palladius in Lausiac, and several letters of St.

Paulinus, St. Jerom, St. Austin, &c. Her Greek Acts, extant in Metaphrastes,

are translated in Lipomannus, t. 5. Other Greek acts of the same age are

mentioned and commended by Allatius. See Fabricius, Bibl. Gr. t. 6, p. 548, and

Fontanini, Hist. Eccl. Aquil. l. 4.

Men

often say, we are not obliged to do so much for salvation; but the example of

the saints ought to convince us, that we are bound at least by extraordinary

watchfulness and fervour to surpass the multitude, and not go with the world.

In the general torrent of example every one flatters himself, and relies upon

the crowd which goes the same way. Men follow one another to run upon

destruction: they are seduced, and they seduce. We perhaps rely sometimes on

the example of those who follow ours. Does not Christ assure us that the way to

life is narrow, and trodden by few? If we are content to follow the crowd, we

condemn ourselves by taking the broad way. The saints by fearing to fall into

it, seemed to set no bounds to their fervour.

Note

1. See Jos. Assem. in Calend. p. 522. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume

XII: December. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : https://www.bartleby.com/210/12/313.html

Melania the Younger,

Widow, and Pinian (RM)

Born in Rome, Italy, c.

383; died in Jerusalem, December 31, 438 (or 439). Melania was the product of

several pious generations of the patrician Roman family of the Valerii. Her

grandmother, Saint Antonia Melania the Elder, widow of Valerius Maximus, was one

of the first Roman matrons to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. When Melania

the Elder moved to Egypt in 372 and then to Palestine to become a nun, she left

behind her in Rome her six-year-old son Valerius Publicola, who fathered

today's saint and was a Roman senator.

Antonia Melania the

Younger began her life in the splendor of the Valerian palace. She inherited a

fantastic fortune--estates in what are now eight modern countries. She

controlled whole populations. Yet Melania chose asceticism, which, according to

Saint Jerome was inherited from her mother. Her life made contact with several

other saints, Saint Paulinus of Nola, Augustine of Hippo, and Jerome--all of

whom had a very high opinion of her and her husband.

At age 13, Melania

married her 17-year-old cousin Saint Valerius Pinianus against her will. She

suggested that they live together in celibacy, in exchange for which he could

have her entire fortune. He insisted that they have two sons first. They had a

daughter they vowed to virginity, then a son. Both of whom died soon after

birth. Melania seemed to be dying, too, and made her recovery contingent upon a

life of abstinence. Pinianus agreed and she recovered.

Their religious devotion

and austere lifestyle provoked opposition from other family members. But after

her father's death, her widowed mother, Albina, the Christian daughter of a

pagan priest, was also won over. The couple then lived in simplicity as far as

was possible. They struggled to give away all their property--her annual income

was the equivalent of about US$20 million today. When they tried to sell their

property for the good of the poor and the Church, their family appealed to

Emperor Honorius, who sided with Melania. She became one of the greatest

religious philanthropists of all time: She endowed monasteries in Egypt, Syria,

and Palestine; helped churches and monasteries in Europe; aided the poor, sick,

captives, and pilgrims.

Not only did they provide

charity out of their surplus, Melania and Pinianus gave of themselves. They

freed their 8,000 slaves in two years, but the slaves refused to be freed, so

they transferred themselves to Pinianus's brother. By the time Melania was 20,

Pinianus, Albina, and Melania left Rome and turned their country estate into a

religious center. Their palace became a home for innumerable sick, prisoners,

and exiles whom the couple personally sought out.

When the Visigoths

invaded Rome in 408, Pinianus and Melania moved to Messina, Sicily. In 410,

Rome was taken and their palace burned. Finding Sicily in danger, they decided

to cross the Mediterranean to Carthage with the aged priest Rufinus. They were

shipwrecked on the island of Lipari, which Melania ransomed from pirates.

Finally, they moved to their estate in Tagaste, Numidia, in northern Africa.

The saintliness of the couple quickly became apparent to the denizens. The

citizens of nearby Hippo demanded that Saint Augustine ordain Pinianus at once.

Augustine compromised by saying that he should stay in Hippo for a time as a

layman. The couple also established a monastery and a convent, where she lived

in great austerity.

By 417, most of their

estates were sold and the couple was truly poor. Melania, Pinianus, and Albina

made a pilgrimage to Palestine, then visited the desert monks in Egypt, and

finally settled in Jerusalem, where Melania's grandmother Antonia Melania had

been living as a nun. Melania's cousin, Saint Paula, introduced her to the

group of Roman women in Bethlehem presided over by Saint Jerome, whose friend

she became.

After her mother Albina's

death in 431, Melania established herself as a recluse. She founded a monastery

and sent her husband to seek out those with vocations. He succeeded, then died

in 432, and was buried on Mount Olivet near her mother. Melania lived in a room

near his tomb for four years until she attracted numerous disciples. Then she

founded and directed a convent to care for the Church of the Ascension and sing

the Divine Office continually for her mother and husband. She shared in their

life of prayer and good works, and occupied herself with copying books.

Her uncle Volusianus

wrote to her insinuating that she should consider marriage to Emperor

Valentinian III. She went to Constantinople, ingratiated herself with the

imperial family, then undertook a brisk campaign against the Nestorian heresy,

and fell ill. She converted her uncle and assisted him to a holy death on

January 6, 437.

Melania went to Bethlehem

for her last Christmas and spent it with Saint Paula. She returned to her

convent for the feast of Saint Stephen and died five days later, with Saint

Paula, the monks, nuns, and the bishop present. As she was dying Paula began

crying and Melania consoled her.

Melania's biography was

written by her chaplain, Gerontius. Although Melania has been venerated in the

Eastern Church for centuries, she has had no cultus in the West. Pope Pius X,

however, approved the observance of her feast in 1908 for the Somaschi, an

observance followed by the Latin Catholics of Constantinople and Jerusalem

(Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney, Encyclopedia, Martindale).

In art, Melania is

generally shown praying in a cave, a skull and vegetables near her

(Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1231.shtml

Святая

Мелания Римляныня, фреска из Монастыря Св.Стефана в Метеорах.

CHAPTER LXI: MELANIA THE

YOUNGER 1

[I] SINCE I promised

above to tell about the (grand) daughter of Melania, I am constrained to pay

the debt, for it is not just that men should disdain her youthfulness in

respect of the flesh and leave on one side with no pillar to commemorate it

such great virtue, virtue which, frankly, far surpasses that of old and zealous

women. Her parents by using compulsion made her marry a man of the highest rank

in Rome. Her conscience was always being pricked by the tales she heard about

her grandmother, and (at last) she was so goaded that she felt unable to

perform her marriage duty. [2] For, two male children having been born to her

and both having died, she came to have such great hatred of marriage as to say

to her husband Pinianus, son of Severus the exprefect: " If you choose to

practice asceticism with me according to the fashion of chastity, then I

recognize you as master and lord of my life. But if this appears grievous to

you, being still a young man, take all my belongings and set my body free, that

I may fulfil my desire toward God and become heir of the zeal of my

grandmother, whose name I also bear. [3] For if God had wished us to have

children, He would not have taken away my children untimely." After they

had, struggled under the yoke a long while, at last God had pity on the young

man and planted in him a zeal for renunciation, so that the word of Scripture

was fulfilled in their case: " How knowest thou, O woman, that thou shalt

save thy husband?'' (I Cor. 7:16) So having been married at thirteen and having

lived with her husband seven years, in the twentieth year she renounced the

world. And first she gave her silk dresses to the altars: this the holy

Olympias has also done. [4] Then she cut up her other silks and made them into

different church ornaments. And having entrusted her silver and gold to a

certain Paul, a priest, a monk of Dalmatia, she sent them across the sea to the

East, 10,000 pieces of money to Egypt and the Thebaid, 10,000 pieces to Antioch

and its neighborhood, 15,000 to Palestine, 10,000 to the churches in the

islands and the places of exile, while she herself distributed to the churches

in the West in the same way. [5] All this and four times as much she snatched,

if God will allow the expression, " out of the mouth of the lion,"

(II Tim. 4:17) Alaric by her faith. And she freed 8000 slaves who wished

freedom, for the rest did not wish it, but preferred to be slaves to her

brother; and she allowed him to take them all for three pieces of money. But

having sold her possessions in the Spains, Aquitania, Tarragonia and the Gauls,

she reserved for herself only those in Sicily and Campania and Africa and

appropriated their income for the support of monasteries. [6] Such was her wise

conduct with regard to the burden of riches. And her asceticism was as follows.

She ate every other dayto begin with after a five days' intervaland assigned

to herself a part in the daily work of her own slavewomen, whom also she made

her fellow ascetics.

She had with her also her

mother Albina, who lived a similar ascetic life and distributed her riches for

her part privately. Now these ladies are dwelling on their properties, now in

Sicily and now in Campania, with fifteen eunuchs (apparently to be interpreted

literally; but perhaps metaphorically in allusion to Mt. 19) and sixty virgins,

both free and slaved.

[7] Similarly also

Pinianus her husband lives with thirty monks, reading and busying himself with

the garden and solemn conferences. But in no small way did they honor us when

we, a numerous party, went to Rome because of the blessed bishop John; they refreshed

us both with hospitality and lavish equipment for the journey, thus winning for

themselves with great joy the fruit of eternal life by their Godgiven works

springing from a noble mode of life.

Palladius: The

Lausiac History

SOURCE : https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/palladius-lausiac.asp#

Ícone

de Melânia, a Jovem

St. Melania (the Younger)

Born at Rome,

about 383; died in Jerusalem,

31 December, 439. She was a member of the famous family of Valerii.

Her parents were Publicola

and Albina, her paternal grandmother of the same name is known as Melania,

Senior. Little is known of the saint's childhood,

but after the time of her marriage, which occurred in her thirteenth year,

we have more definite information. Through obedience to her parents she married one

of her relatives, Pinianus a patrician. During

her married life of seven years she had two children who died young.

After their death Melania's inclination toward a celibate life reasserting

itself, she secured her husband's consent and entered upon the path

of evangelic perfection, parting little by little with all

her wealth. Pinianus, who now assumed a brotherly position toward

her, was her companion in all her efforts toward sanctity.

Because of the Visigothic invasions

of Italy,

she left Rome in

408, and for two years lived near Messina in Sicily.

Here, their life of a monastic character was shared by

some former slaves. In 410 she went to Africa where she

and Pinianus lived with her mother for seven years, during which time

she grew well acquainted with St.

Augustine and his friend Alypius. She devoted herself to works

of charity and piety,

especially in her zeal for souls,

to the foundation of a nunnery of

which she became superior, and of a cloister of

which Pinianus took charge. In 417, Melania, her mother,

and Pinianus went to Palestine by way of Alexandria. For a year

they lived in a hospice for pilgrims in Jerusalem,

where she met St.

Jerome. She again made generous donations, upon the receipt of money

from the sale of her estates in Spain.

About this time she travelled in Egypt,

where she visited the principal places of monastic and eremetical life,

and upon her return to Jerusalem she lived for twelve years, in a

hermitage near the Mount of Olives. Before the death of her

mother (431), a new series of monastic foundations had begun. She

started with a convent for women on

the Mount of Olives, of which she assumed the

maintenance while refusing to be made its superior. After her husband's death

she built a cloister for men,

then a chapel,

and later, a more pretentious church. During this last period (Nov., 436),

she went to Constantinople where she aided in

the conversion of her pagan uncle,

Volusian, ambassador at the Court of Theodosius II, and in the

conflict with Nestorianism.

An interesting episode in her later life is the journey of the

Empress Eudocia, wife of Theodosius, to Jerusalem in 438. Soon

after the empress's return Melania died.

The Greek

Church began to venerate her shortly after her death, but

she was almost unknown in the Western

Church for many years. She has received greater attention since the

publication of her life by Cardinal Rampolla (Rome, 1905). In 1908, Pius

X granted her office to the congregation of clergy at Somascha.

This may be considered as the beginning of a zealous ecclesiastical cult,

to which the saint's life and

works have entitled her. Melania's life has been shrouded in

obscurity nearly up to the present time; many people having wholly or partially

confounded her with her grandmother Antonia Melania. The accurate knowledge of

her life we owe to the discovery of two manuscripts;

the first, in Latin, was found by Cardinal Rampolla in the Escorial in

1884, the second, a Greek biography, is in the Barberini library.

Cardinal Rampolla published both these important discoveries at

the Vatican printing-office.

Schlitz, Carl. "St. Melania (the Younger)." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 8

Jun. 2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10154a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Michael C. Tinkler.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10154a.htm

Weninger’s

Lives of the Saints – Saint Sylvester, Pope, and Saint Melania, the Younger

Article

The Roman Martyrology

speaks of the holy Pope, Saint Sylvester, as follows: “At Rome, the birth-day

of the holy Pope, Sylvester, who baptized the Emperor, Constantine the Great,

confirmed the general Council of Nice, and who, after having accomplished many

other holy works, ended his life peacefully.

Saint Sylvester was a

Roman, born of Christian parents, and carefully instructed in religion and all

necessary knowledge by the priest, Carinus. To the strangers who came to Rome

to perform their devotions, he showed all kindness. Tarquinius, the prefect,

thought that Sylvester had gained much money in this manner, and calling him

into his presence, menaced him with the most cruel tortures, in case he refused

to bring him all he had. Sylvester looked at him and said: “This night you will

die; how can you, therefore, fulfill your menaces?” And, in truth, Tarquinius

was suffocated that night from swallowing a fish-bone; hence Sylvester was

released from the prison into which he was cast. After the death of Pope

Melchiades, he was unanimously elected to be the head of the Church. This was

in the reign of Constantine, who already at that time greatly favored the

Christians; but as he was engaged in warfare away from Rome, the pagan officers

began again to persecute the faithful. Sylvester, advised by the clergy at

Rome, left the city and went to Mount Soracte, where he dwelt in a cave to

which all Christians had ad- mittance. There the holy Father offered his tears

to heaven, with humble prayers, that the Almighty, for the welfare of

Christendom, would end the persecution. His prayer was heard. Constantine the

Emperor, became leprous over his whole body, and his physicians and the

idolatrous priests advised him to bathe in the blood of infant children. On the

following night, in his sleep, there appeared to him two venerable old men, who

told him to call the high-priest of the Christians, from Mount Soracte, who

would prescribe for him a much more wholesome bath. Sylvester was called, and,

being informed of the vision, he showed the Emperor the pictures of the two

holy Apostles, Peter and Paul, in which Constantine immediately recognized the

two venerable men whom he had seen in his sleep. As the holy Pope informed him

farther, that the wholesome bath, of which the Apostles had spoken, was no

other than the bath of regeneration, or holy Baptism, the Emperor showed

himself ready to receive it, and having been sufficiently instructed in the

faith, he was baptized to the great joy of the Pope and all the faithful. By

the advice of the Saint, the Emperor erected many magnificent* churches, and

ornamented them splendidly, and gave” permission to the Christians to build

temples to the Lord wherever they desired. In the reign of this Pope, the first

General Council was held at Nice, in which the doctrine of Arius was

anathematised. The Papal nuncio presided over it, and the Emperor, who

liberally paid the travelling expenses of all poor bishops, was present, not as

a superior, but only as a protector. He sat the last in rank, and upon a low

chair. The esteem in which he held the clergy may be learned from a memorable

speech he made .there, in which he said: “If I should surprise a priest in an

actual sin, I would cover it with my purple, and endeavor to conceal it, from

esteem of the priesthood.” The decrees of the Council were confirmed by the

Pope at Rome, and received by all the faithful. Many other things done by Saint

Sylvester for the welfare of the Church, are related by the historians of his

life. He reigned over the Church 21 years and some months, and died a peaceful

and happy death, rejoicing that he was going to the Lord.

We have a bright example

of many virtues, especially of chastity, disregard of all things temporal, zeal

to labor for the honor of God, and charity to the poor, in Saint Melania,

called the Younger, to distinguish her from another Melania, who is surnamed

the Elder.

Melania, the Younger, was

born at Rome, where her parents not only belonged to the first nobility, but

were also considered the richest in the city., She admired virginal chastity

from her early youth, and desired to remain a virgin; but her parents forced

her to marry Pinian, a noble and wealthy youth. She became the mother of two

children, the first of whom lived scarcely a year, and the second died soon

after it had been baptized. This taught Pinian the vanity of all earthly

happiness; and although he had only reached his 24th year, and Melania was but

20, he agreed with her to live in future in perpetual continence, and to employ

the large fortune which their children would have inherited, for the honor of

God, for the maintenance of the clergy, for the consolation of the poor and for

other good works. As soon as they had made this, resolution, they chose a

dwelling, out of the city, Upon one of their estates, and served God and their

neighbor unostentatiously. They sold the estates which they possessed in Rome

and other places in Italy, and spent the money to relieve the poor, to build

and endow churches and convents, and to maintain priests and religious. After

this, they sailed to Sicily and Africa, where they also possessed valuable

estates, and after selling them, they intended to continue their charitable and

religious undertakings. On one island where they landed, they ransomed many

Christian captives from slavery to the infidels. At Tagaste, where Saint

Alipinus, a friend of Saint Augustine, was bishop, they built two convents, one

for women, and one for men. Into one Pinian went, and into the other, Melania.

Seven years they lived there in the exercises of the most noble virtues.

Melania fasted daily until evening, when she partook only of bread and water,

or of some herbs seasoned with a little oil. Afterwards she ate only once every

two days, then every three days, until finally once every week. All admired so

extraordinary a severity, in which nobody was able to follow her. She devoted

the whole night to prayer and contemplation, except two hours which she gave to

sleep, lying on a straw mattrass on the floor. During the day, she also

employed many hours in prayer, and the rest in work, which consisted of sewing

and mending clothes for the poor, in visiting the sick and needy, in assisting

the suffering, and in copying devout books for the welfare of men. After seven

years, she had a great desire to go to Jerusalem and visit the holy places.

Hence, she travelled with Pinian, her spouse, and Albina, her mother, from

Tagaste to Egypt, and arrived in Alexandria, where she was detained by

sickness. On her recovery, the holy pilgrims proceeded to Jerusalem. The

devotion with which Melania visited the holy places can hardly be told. Every

evening she went to the sepulchre of Christ, and remained there until morning.

Her love for the Holy Land became such that she resolved to remain there.

Hence, she had a little cottage built on Mount Olivet, where she lived for

fourteen years a most holy and religious life. Her spouse did the same in a

monastery at Jerusalem. The reputation of the holiness of Melania drew many

widows and virgins to her, who desired to live under her guidance. To this end,

she built a convent and a church at Jerusalem, and received all those who came

to her. She would never take upon herself the office of Superior, but waited on

the others as though she were a most lowly servant; but she untiringly

instructed them, both by word and work, how to serve the Lord. The death of her

pious mother, Albina, and of her spouse, Pinian, she bore with perfect

submission to the divine will, and thinking that she would soon follow them,

she redoubled her zeal in doing good. While all her thoughts were directed to

her great journey into Eternity, she was induced to take another earthly

journey. Volusian, her cousin, had been sent from Rome to the court of

Constantinople, and becoming very sick there, desired to see Melania, and had

written to her to that effect. Melania undertook the wearisome voyage, desiring

to convert Volusian, who was still a heathen and addicted to many vices. No

sooner, therefore, had she arrived at Constantinople than she hastened to her

sick cousin. Seeing her emaciated by fasting and the austerity of her life, he

cried, full of surprise: “O dear Melania! how different you look from what you

were! How your figure, your whole appearance has changed!” “Learn from it, my

dear cousin,” said Melania, “what I think of the future life and eternal

happiness; for I surely would not have esteemed so lightly all temporal honor,

would not have divested myself of all earthly riches, nor have treated my body

so severely, had I not surely believed that I should come into the possession

of greater honors, riches and joys.” These words made a deep impression upon

Volusian, and as Melania earnestly exhorted him to become a Christian and do

penance, he received holy baptism, and soon after died a peaceful death.

Melania, happy at this, was not satisfied with having opened heaven to only one

soul. At that period, there were in Constantinople many heretics, who called

themselves Nestorians. With these Melania disputed daily for several hours, as

she not only spoke the Greek language, but was also well instructed in the

Christian faith. Many of the heretics were brought back by her into the pale of

the true Church. She gave also many wholesome admonitions to the Emperor

Theodosius and his Empress Eudoxia, who had called her to their court After

this, she returned to the convent at Jerusalem, where God soon revealed to her

that her end was approaching, with the comforting assurance that He would

reward her with eternal goods, for the temporal goods she had employed in His

service. The joy that filled Melania’s heart at this revelation, the reader may

easily imagine. But she left nothing undone to prepare herself worthily for her

last hour. She once again visited the holy places with great devotion, and

passed the Christmas in the stable at Bethlehem, where our Lord had been born.

Returning to the convent, she became sick, desired to receive the holy

Sacraments, and after they had been administered to her, she gave her last

instructions to her religious. She was- visited by many who lamented her

departure. She herself, however, said, with great fortitude: “The Lord’s will

be done!” After these words, she gave her soul, ornamented with so many

extraordinary virtues, into the hands of her Creator, on the last day of

December, in the year 438, according to Baronius and several others. Her tomb

was glorified with many miracles, and her holy life became known all over the

Christian world.

Practical Considerations

• Both Saint Sylvester

and Saint Melania passed their whole lives in the service of the Lord. They

were careful to avoid sin; unwearied in the practice of good works; patient in

persecutions, trials and crosses. How greatly this must have consoled them in

their last hour! How happy both must now be in heaven!

The feast day for these

saints ends the year. If it also proved the end of your life, would you be as

happy as these two Saints? Would you have well-founded hopes to participate in

the joys of heaven? Consider how you have passed this year, and all the

preceding ones, and you will be enabled to answer the foregoing question. You

have had, in this year, 12 months, or 52 weeks, which are 365 days or 8760

hours! How have you passed these? Can you say truthfully, that you have

employed the 20th part of them to the end for which they were given you by the

Almighty? How have you employed so many opportunities to do good, which you

had? Have you been careful in avoiding sin? Have you practised good works? Have

you borne, with Christian patience, all that God has laid upon you? Have you,

in one word, been diligent and unwearied in the service of God and in working

out your, salvation? If you were able to answer all these questions

affirmatively, I could assure you that you have well-founded hopes of eternal

salvation, should you die today; but on the contrary, anxiety and fear must

befall you, if you are obliged to say, with the wicked man: “I have had empty

months.” (Job 7) Empty in good works, empty in merits, but full of indolence,

full of sin, full of vice, or, as the sinner said on his death-bed: “But now I

remember the evils that I did.” (1st Maccabees 6) I have done much evil, but

little good, and the little good I have done, was done without earnestness,

without zeal. Oh! such confessions can give to a dying person no consolation,

no satisfaction, but only extreme anxiety, and may even bring him to despair.

To have served the Lord zealousalv to have labored earnestly for the salvation

of our soul, to have avoided sin, or sincerely repented of it when committed;

and to have constantly practised good works, this will give consolation and

satisfaction to us in our dying hour, and hope to enter heaven. Endeavor so to

conduct yourself during the following year, that you may have this consolation

and hope, when you are dying.

• Saint Sylvester and

Saint Melania received many special graces from heaven, and used them to the

hon- or of God, the salvation of their own souls, and that of others. Can you

complain that you have not received, above thousands of others, especial graces

from God? Certainly not. But God can complain of you that you have not employed

them to your salvation. Let your thoughts go back only over this one year which

ends today. Can you count the benefits which God has bestowed on your soul and

body, in preference to many thousands, although you have not deserved them? And

if He had done nothing but preserved your life until this hour, that you might

not die in your sins; if He had given you nothing but so much time for penance

and so many opportunities to work out your salvation, He would have shown

Himself much more merciful and gracious towards you than towards thousands of

others, whom He has called, in this year, laden with sin, into the other world.

How have you conducted yourself towards God? What use have you made of His graces

and mercies? How have you manifested your thankfulness? Is it possible that you

can think of it without fear, without shame? Ah! your constant indolence in the

service of the Almighty, and more than that, the many and not small sins you

have committed, are no signs of gratefulness, but of great wickedness.

Employ at least this day

in humble gratitude for the many benefits which you have received during the

year, and in deep contrition for your ingratitude and wickedness. Give due

thanks to the Almighty for all His graces and benefits. Repent, with your whole

heart, and, if possible, with tears of blood, of your many sins. As

thanksgiving for so many graces, as atonement for so many sins, offer to the

Lord all that which has been done by others to His honor during the year, but

above all offer Him a contrite and humble heart, which, on this day, resolves

to serve Him in future with zeal and constancy. Recite, in thanksgiving, the

Ambrosian hymn of praise: “We praise thee, O God, etc.,” and in atonement for

your sins, the 50th psalm, “Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great

mercy, etc.”

MLA

Citation

Father Francis Xavier

Weninger, DD, SJ. “Saint Sylvester, Pope, and Saint Melania, the

Younger”. Lives of the Saints, 1876. CatholicSaints.Info.

4 June 2018. Web. 31 December 2022. <https://catholicsaints.info/weningers-lives-of-the-saints-saint-sylvester-pope-and-saint-melania-the-younger/>

Melania the Younger (c.

385–439)

Roman ascetic who was an

important patron of the early Christian Church. Born around 385; died in

439 ce; daughter of Valerius Publicola (son of Melania the Elder) and Albina;

married Valerius Pinianus (son of Valerius Severus, the Roman prefect), around

399.

The daughter of Valerius

Publicola (the son of Melania

the Elder ) and Albina , Melania the Younger was born around

385. Her parents were from extremely wealthy and well-connected Roman families

of Senatorial rank; for example, her maternal grandfather, Ceionius Rufius

Albinus, served as the prefect of Rome, a post reserved for the most elite,

between 389 and 391 ce. On her father's side, Melania's family had been

Christian for at least a couple of generations before her birth—a testimony to

the growing impact of Christianity on Rome's ruling class in the mid-4th

century. Her maternal ancestors, however, had been both important members of

the pagan establishment and slower to embrace Christianity; her

great-grandmother Caecina Lolliana was a priestess of Isis, and her

great-uncle Publilius Ceionius Caecina Albinus was a pontifex. In fact,

Melania's maternal grandfather was probably pagan, as is suggested by the fact

that his son (Melania's uncle), Rufius Antonius Agrypnius Volusianus, converted

to Christianity, largely because of Melania's advocacy, only shortly before his

death. If Melania the Younger's maternal grandfather remained a pagan

throughout his life, he nevertheless was tolerant of Christianity, as is

intimated by the following: he (perhaps) took a Christian wife; he seems to

have corresponded with St. Ambrose of Milan; he clearly married his daughter

Albina to a Christian; he allowed her to convert to Christianity if she had not

already been raised in the faith by a Christian mother; and he did nothing to

interfere with the Christian upbringing of Melania the Younger. Rome in the

mid-4th century was a fairly tolerant place where a Christian and a pagan could

rub elbows and even marry without necessarily adopting the other's religion.

(This tolerance was lost in subsequent generations as the Church, encouraged by

Christian emperors, eradicated the last vestiges of pagan Rome.) Melania the

Younger may have had a brother, but if so, he died without issue and probably

young.

When she was 14, Melania

the Younger wed a distant relative, the 17-year-old Christian Valerius Pinianus

(a son of Valerius Severus, the Roman prefect of 382). This union reunited two

threads of an ancient house, in order to foster political influence and

consolidate the immense economic resources which each side of the family

individually possessed. The marriage does not seem to have pleased Melania the

Younger, whose ascetic religious inclination had already been incited by the

example of her grandmother Melania the Elder. Desiring a life of ascetic

chastity but pressured by her family to generate heirs who could maintain the

family's station and wealth, Melania the Younger reluctantly acceded to her

father's wishes. Her marriage resulted in two pregnancies: the first producing

a daughter and the second a stillborn son—a birth which almost killed Melania.

Not long after this heartbreak, Melania the Younger's daughter, not yet two,

also died. The shock of the double deaths convinced both Melania and her

husband Pinian that her original wish to eschew intimate relations was also

God's will. As a result, although they continued to live together, the couple

renounced conjugal relations and began to experiment with an austere way of

life which was the antithesis of their upbringing.

Accomplishing the latter

was not an easy task, for the couple possessed vast estates, great movable

wealth, and huge numbers of slaves across three continents. These they began to

sell off, beginning with their Italian and Spanish properties, in order to fund

a number of Christian works. Melania the Younger's father, although himself a

generous patron of Christian causes, stoutly opposed their decision to divest

entirely their worldly goods, as well as their choice to remain childless—for

he saw no shame in secular Christianity and did not relish the thought that he

would never know grandchildren. Unable to make headway with his willful

daughter, however, the dying Valerius Publicola at last made a virtue out of

necessity and reconciled with Melania the Younger on her terms.

Also opposed to Melania's

and Pinian's decision to disburse their wealth was Pinian's brother, Severus,

who attempted legal action in order to maintain their family's control of the

estate being so purposefully liquidated by the couple. Presumably, Severus'

case revolved around the fact that neither Melania the Younger nor Pinian was

25 years old—the age of legal authority for such actions—when they began their

wholesale sell-off around 405. Nonetheless, this attempt failed when Melania

the Younger, exploiting the connections which came with her wealth and station,

approached Honorius, the emperor of the Roman West, through Serena (Honorius'

mother-in-law and the wife of Stilicho, who at the time was Honorius' most

important general), probably in the year 408. Through Serena's successful

advocacy, Honorius not only allowed Melania and Pinian to act as they saw fit,

he even ordered bureaucrats dispersed throughout the empire to act as agents on

behalf of their divestment.

Much, but not all, of

Melania's and Pinian's estate in Italy and Spain was thereby converted to cash

by 410, in which year a double disaster hurt both interests. First, Honorius

executed Serena and Stilicho for political reasons (the game at the imperial

court was played for high stakes), and second, the Visigoths invaded Italy and

sacked Rome. Before both disasters occurred, however, Melania and Pinian, with

her mother in tow (Melania was all the family Albina had after the death of her

husband), had made their way to North Africa to hasten the sell-off of

properties there. Thus, they escaped both the fallout of the emperor's anger

aimed at their political friends, and the ravages of the Visigoths, although

they did lose their unsold Italian properties as a result of the appearance of

the barbarians.

In North Africa, the trio

established themselves on land they owned near Thagaste, the small hometown

of St.

Augustine, where they grew close to that great bishop's brother, Alypius.

From this location, they oversaw the conversion of most of their African

estates into cash which they used both to adorn the church of Thagaste and to

distribute to the needy through local monasteries and convents. Concerning the

latter, so much money was spent so quickly to so little lasting effect that

Augustine, Alypius, and Aurelius, bishop of Carthage, advised the

well-intentioned threesome to give up on trying to feed all of the poor and to

concentrate on investing in the spiritual future. Melania, Pinian and Albina

heeded this advice and endowed both a monastery and a convent, their first such

foundations. About this time, an episode which had the potential of rupturing

the friendship between Augustine, Melania and Pinian occurred, in which the

people of Hippo (where Augustine was bishop) attempted to force ordination upon

Pinian so that he could become their priest. This was deftly avoided by Pinian,

who rather sought the life of a recluse, but local feelings were bruised and he

had to swear that he would not take orders elsewhere.

Melania the Younger,

Pinian and Albina remained in North Africa for about seven years, during which

time they embraced more and more isolated asceticism: their clothes became

little more than rags, their fasts became longer and more frequent, and all

comforts were purposefully shunned (they lived in barren monastic cells and

even had their beds constructed so as to make sleeping a torture). Throughout

all of this, they spent most of their time in prayer, studying scripture, and

working; in Melania the Younger's case, this frequently meant copying books.

When they did strike out into the larger world, it was to advise the less driven

to avoid heresy at all costs and to embrace a life of chastity (even going so

far as to bribe men and women to remain chaste). The issue of heresy was a

personal one to Melania the Younger, for her famous grandmother Melania the

Elder had had her reputation tainted through her association with the

increasingly discredited theology of Origen. Although Melania the Younger

stayed clear of that particular pitfall, the world of the early 5th century was

fraught with theological dangers, and reputations could be permanently lost if

one fell in with the wrong theological sort.

However real their desire

to withdraw from the world might have been, Melania and Pinian found their fame

begin to spread, increasingly bringing the outside world to their doors.

Perhaps motivated by a desire to cut back on the attention that ascetic piety

drew at that time, and perhaps also influenced by the erosion of North African

social stability in the wake of Rome's continuing collapse before the barbarian

invasions, Melania the Younger, Pinian and Albina left Thagaste (417) to

journey to the Holy

Land. The traveled by way of Alexandria and Egypt (in the footsteps of

Melania the Elder), where they met many of the most famous priests and bishops

(like Cyril) of the day, as well as many of the charismatic Christian hermits

(like Nestoros) who were exerting so much influence over the contemporary

practice of the Christian faith. Their stay in Egypt obviously left an

indelible impression on the pilgrims, because even though they continued on to

Jerusalem to establish their permanent residence there, they nevertheless took

a subsequent opportunity to return to Egypt so as to press their largesse upon

the reluctant holy women and men of that land.

In Jerusalem, the

threesome took up their abodes in tiny cells constructed on the Mount

of Olives, close to, but definitely distinct from, the religious community

which a generation before had been founded by Melania the Elder. It seems that

Melania the Younger wanted it known that her theology was not that of her

grandmother, a notion that was further driven home by her friendly visits to

Jerome, her grandmother's theological rival. On the Mount

of Olives, both Albina (c. 430) and Pinian (c. 431) died, losses which left

their mark on Melania the Younger. Her mother's death caused her to abandon all

social contact for a year, after which she founded a second convent (her first

since North Africa), situated on the Mount of Olives. Although Melania the

Younger declined to become this community's leader, she did write its rule and

intervened to make life more palatable for its members when the austerity of

their abbess tried even the most devout. After Pinian's death, Melania the

Younger engaged in a second period of mourning, this time for four years, after

which she established a second monastery, also on the Mount of Olives, in his

memory. Interest-ingly, by the time of this, her final, foundation, Melania the

Younger's money had run out, for the construction of this community was

dependent upon a gift of cash which she received from an admirer.

Soon after Melania the

Younger set up these communities, she learned that her (as yet) pagan uncle,

Volusian, was traveling to Constantinople upon imperial business. Desiring that

he should embrace Christianity, and wishing to see the greatest city of the

Roman world, she decided to visit the capital of the Eastern Empire herself.

Among the entourage accompanying her was Gerontius, the priest whom she probably

met in Jerusalem and who wrote the chronicle of her life from which most of the

information about her comes. The journey from Jerusalem to Constantinople was a

triumph of sorts, for her fame had preceded her virtually everywhere she went.

Her reception also was one as befitted a celebrity: among those Melania the

Younger met was the Empress Eudocia (c.

400–460), who was so impressed by Melania's piety that she would one day return

Melania the favor by visiting her in Jerusalem. Moreover, her journey had its

intended effect, for although Volusian died in Constantinople, he did so only

after having received baptism.

Melania the Younger

thereafter returned to Jerusalem and her cell on the Mount of Olives. There she

resumed her ascetic life while continuing her sponsorship of Christian

building: in addition to the religious communities which were constructed under

her patronage, she built a chapel of the Apostolion and a martyrium to hold

relics attributed to Zachariah, Stephen, and the 40 martyrs of Sebaste. Melania

the Younger was so busy with these various activities that she left Jerusalem

only one time after her return from Constantinople. When Eudocia made her way

to Jerusalem, in part to preside over the installment of relics in Melania's

martyrium (Eudocia had a vested interest: she had wanted these relics for

projects of her own), Melania the Younger met her at the port city of Sidon.

The last three or so years of Melania's life thus were largely given over to

spiritual struggle, prayer and study. Throughout, her reputation continued to

grow—so much so that when she died in 439, Melania the Younger was mourned not

only by those living in her communities, but by all Christians, great as well

as humble. No taint of unorthodoxy affixed itself to her memory. In fact,

present at her death was Paula the Younger , whose grandmother Paula (347–404)

had (with Jerome) been among Melania the Elder's most ardent theological

critics. It seems that Melania the Younger rehabilitated the reputation of her

family in the minds of those who constituted the Church's orthodox faction.

William Greenwalt ,

Associate Professor of Classical History, Santa

Clara University, Santa

Clara, California

Women in World History: A

Biographical Encyclopedia

Heilige

Melania de Jongere als kluizenares. S. Melania Junior (titel op object).

Kluizenaressen (serietitel). Sacra Eremus Ascetriarum (serietitel). prentmaker:

Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert, naar ontwerp van: Abraham Bloemaert, uitgever:

Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert, uitgever: Hendrik Aertssens (mogelijk), 1590 - 1612

en/of 1619

Santa Melania la Giovane Penitente

Etimologia: Melania =

nera, scura, dal greco

Martirologio Romano: A

Gerusalemme, santa Melania la Giovane, che con suo marito san Piniano andò via

da Roma e si recò nella Città Santa, dove abbracciarono la regola, lei tra le

donne consacrate a Dio e lui tra i monaci, ed entrambi riposarono in una santa

morte.

I nonni a volte sono determinanti nelle decisioni di una famiglia, ma nel secolo V a Roma, lo erano certamente in modo molto influente. Infatti se Melania la Giovane poté vincere tutte le opposizioni aspre dei parenti, per la sua scelta di farsi monaca, lo dovette all’intervento della nonna Melania l’anziana, che anche lei da giovane dovette affrontare e vincere le stesse resistenze.

Figlia di Valerio Publicola della gens Valeria e di Ceionia Albina della gens Ceionia, quindi discendente di gloriose famiglie di Roma; a 14 anni sposò il cugino Piniano anche lui della gens Valeria, che dopo la morte di due loro figli, Melania convinse a praticare una vita penitente e casta.

Influenzata dalla propaganda monastica che nel secolo V era assai fervorosa in Roma, la pia matrona lasciò la città per ritirarsi con tutti i servi in una villa suburbana per vivere una vita monastica.

Qui sorse l’opposizione tenace dei parenti, vinta solo con l’intervento della nonna paterna, che qualche decennio prima, aveva fatta la stessa scelta fra le resistenze della nobile famiglia.

Nel 406 si trasferì a Nola presso s. Paolino, forse suo lontano parente, dopo due anni, nel 408 vista l’invasione dei barbari, si spostò nei suoi possedimenti in Sicilia e ancora nel 410 emigrò in quelli d’Africa, dove conobbe s. Agostino, stringendo con lui una salda amicizia.

Circondata da un centinaio di servi ed ancelle e con la compagnia del marito Piniano e della madre Albina, che la seguivano in questo peregrinare, formando una specie di comunità monastica, decise di recarsi a Gerusalemme, passando prima per l’Egitto, culla del monachesimo orientale, per rendere omaggio ai monaci di cui provava grande ammirazione, cercando di imitarli.

A Gerusalemme volle tenere una vita eremitica più stretta (già la nonna Melania assieme a Rufino, aveva fondato un monastero), facendosi costruire una piccola cella sul Monte degli Ulivi, sede di altri asceti e qui condusse una vita di pesanti penitenze.

Dopo un certo tempo e dopo altri contatti con i monaci egiziani, per apprendere meglio lo spirito ascetico, fondò in una zona molto isolata un monastero femminile e dopo qualche anno, anche uno maschile, con oratori dotati di reliquie di santi martiri.

Il regolamento delle Comunità, disposto da Melania stessa, fu improntato ad una estrema severità, sul modello egiziano, anche se nella liturgia si notava una certa influenza romana ed occidentale.

Fu tanto caritatevole che il suo patrimonio e quello del marito Piniano, morto nel 432, fu lentamente esaurito a favore dei poveri; ebbe una grande fama di santità in tutto l’ambiente di Gerusalemme, dove morì nel 440.

Il culto per s. Melania la Giovane fu abbastanza sentito in Oriente, mentre in Occidente cominciò solo nel secolo IX.

La commemorazione della grande matrona romana, asceta e monaca a Gerusalemme è

al 31 dicembre. Il suo culto fu approvato nel 1908.

Il nome Melania proviene dal greco Melan e significa “scura, nera”; fu un

soprannome e poi nome individuale frequentemente attribuito alle donne brune,

di origine greca ed orientale.

Autore: Antonio Borrelli

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/83500

Ícone

de Melânia, a Jovem

Melania die Jüngere

auch: Melanie

Gedenktag katholisch: 31.

Dezember

Gedenktag orthodox: 31.

Dezember

Name bedeutet: die

Schwarze (griech.)

Wohltäterin,

Klostergründerin und Äbtissin in Jerusalem

* um 383 in Rom

† 31. Dezember 439 auf dem Ölberg bei Jerusalem in

Israel

Melania war Enkelin der

älteren Melania und

nach manchen verwandt mit Pammachius

von Rom. Ihre Familie war begütert; der Vater Valerius Publicola war

Senator und besaß auf dem Mons Caelius - an der Stelle des heutigen Neubaus des