Saint Bernard de

Clairvaux

Abbé, Docteur de l’Église

(+1153)

A quoi pouvait rêver dans

l'éclat de sa jeunesse le fils de Tescelin, chevalier du duc de Bourgogne, et

de dame Aleth

de Montbard, si bonne chrétienne? de chasses ou de tournois? de chants de

guerre ou de galantes conquêtes? En tous cas, certainement pas de vie

monastique comme il en fera le choix à l'âge de vingt-trois ans. D'autant qu'il

entraînait avec lui une trentaine de jeunes en quête d'absolu... Dès 1115,

après trois années de vie monastique à Citeaux, Bernard est envoyé à Clairvaux

pour y fonder l'abbaye dont il restera père-abbé jusqu'à sa mort. Mais loin de

rester cloîtré il parcourt les routes d'Europe devenant, comme on a pu

l'écrire, «la conscience de l'Église de son temps». Il vient plusieurs fois à

Paris, à Saint Pierre de Montmartre, à la chapelle du Martyrium, à la chapelle

Saint Aignan où il vient prier souvent devant la statue de la Vierge qui se

trouve maintenant à Notre-Dame de Paris. Sa correspondance abondante avec des

princes, des frères moines ou des jeunes gens qui requièrent son conseil ne

l'empêche pas de se consacrer à la contemplation tout autant qu'à l'action

directe dans la société de son temps. Infatigable fondateur, on le voit sur sa

mule, traînant sur les routes d'Europe sa santé délabrée et son enthousiasme

spirituel. Sa réforme monastique l'oppose à l'Ordre de Cluny dont il jugeait

l'interprétation de la règle de saint

Benoît trop accommodante. A sa mort, en 1153, ce sont trois cent

quarante-trois abbayes cisterciennes qui auront surgi du sol européen.

A lire: Le

sens de la permanence du peuple juif pour saint Bernard - Abbaye de

Cîteaux, Joël Regnard, ocso.

St Bernard vint dans

notre région en provenance de l'abbaye de Cîteaux. Lassé de la richesse de cette

dernière, il s'installa avec quelques frères moines dans des lieux retirés tels

que Loc-Dieu, Sylvanès, Bonneval, Bonnecombe, Aubrac. (diocèse

de Rodez en Aveyron - deux mille ans d'histoire)

"les cisterciens, en

essor sous l'impulsion de Bernard de Clairvaux, s'implantent à Clermont et à

Bellebranche (1152) puis à Fontaine-Daniel (1205)" (Les abbayes

médiévales: essor et déclin de la vie monastique - diocèse de Laval)

- vidéo de la webTV de la

CEF: Bernard

de Clairvaux (KTO, la foi prise au mot)

Au cours de l'audience

générale, le 21

octobre 2009, le Pape a évoqué la figure de Bernard de Clairvaux (1090-1153),

considéré comme le dernier Père de l'Église car il relança et rénova la

théologie des Pères des premiers siècles. Né en Bourgogne, il entra à vingt ans

au monastère de Citeaux, et le troisième abbé, saint Etienne Harding,

l'envoya fonder en 1115 celui de Clairvaux, dont il devint l'abbé. Il "y

introduisit une vie sobre et mesurée à tout point de vue, nourriture,

habillement, bâtiments, tournée également vers l'assistance aux pauvres".

Ce fut le succès de Clairvaux, dont la communauté ne cessa de grandir et

d'essaimer. "Bernard entretint une vaste correspondance et composa de

nombreux sermons et traités. A partir de 1130, il s'intéressa aux graves

problèmes qui affectaient l'Église et la papauté. Il combattit aussi l'hérésie

cathare dont les fidèles dépréciaient le Créateur en méprisant la matière et le

corps. Il condamna la montée de l'anti-sémitisme et défendit les juifs".

Benoît XVI a ensuite

indiqué que les aspects majeurs de la doctrine de saint Bernard regardaient

Jésus et Marie. "S'il n'apporta pas d'orientations nouvelles à la

recherche théologique, il s'est révélé être un théologien contemplatif et

mystique" pour qui "la connaissance de Dieu est une expérience

profondément personnelle du Christ et de son amour". Ceci est valable pour

tout chrétien car la foi est avant tout recherche de l'amitié de Jésus. Bernard

ne doutait pas non plus que l'on parvient à Jésus par Marie. Ainsi

souligna-t-il "la place privilégiée de la Vierge dans l'économie du salut,

due à la participation de la Mère au sacrifice du Fils". Les réflexions de

saint Bernard, a ajouté le Saint-Père, "interpellent justement,

aujourd'hui encore, théologiens et croyants. Trop souvent on entend résoudre

par la seule force de la raison les questions fondamentales sur Dieu, l'homme

et le monde. En se fondant sur la Bible et les Pères, Bernard montre que sans

une foi profonde, alimentée par la prière et la contemplation... toute

réflexion sur les mystères de Dieu risque de n'être qu'un simple exercice

intellectuel sans la moindre crédibilité. La théologie conduit à la science des

saints, à leurs intuitions des mystères et à leur sagesse, don de l'Esprit,

référence de toute pensée théologique... au final, le modèle le plus

authentique du théologien et de l'évangélisateur est l'apôtre

Jean, qui appuya sa tête sur le cœur du Maître".

(source: VIS 091021 410)

Mémoire de saint Bernard,

abbé et docteur de l'Église. Né en Bourgogne, il entra à vingt-deux ans, avec

trente compagnons, au monastère de Cîteaux, fonda ensuite, sur le territoire de

Langres, le monastère de Clairvaux, dont il fut le premier abbé, dirigeant ses

moines, avec sagesse et par son exemple, sur le chemin de la perfection. Il

parcourut l'Europe pour rétablir la paix et l'unité et fut pour l'Église

entière une lumière par ses écrits et ses conseils. Il mourut, épuisé, dans son

monastère en 1153.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1702/Saint-Bernard-de-Clairvaux.html

Saint Bernard

Docteur de l'Église

(1091-1153)

Saint Bernard, le prodige

de son siècle, naquit au château de Fontaines, près de Dijon, d'une famille

distinguée par sa noblesse et par sa piété, et fut, dès sa naissance, consacré

au Seigneur par sa mère, qui avait eu en songe le pressentiment de sa sainteté

future. Une nuit de Noël, Bernard, tout jeune encore, assistait à la Messe de

Noël; il s'endormit, et, pendant son sommeil, il vit clairement sous ses yeux

la scène ineffable de Bethléem, et contempla Jésus entre les bras de Marie.

A dix-neuf ans, malgré

les instances de sa famille, il obéit à l'appel de Dieu, qui le voulait dans

l'Ordre de Citeaux; mais il n'y entra pas seul; il décida six de ses frères et

vingt-quatre autres gentilshommes à le suivre. L'exemple de cette illustre

jeunesse et l'accroissement de ferveur qui en résulta pour le couvent

suscitèrent tant d'autres vocations, qu'on se vit obligé de faire de nouveaux

établissements. Bernard fut le chef de la colonie qu'on envoya fonder à

Clairvaux un monastère qui devint célèbre et fut la source de cent soixante

fondations, du vivant même du Saint.

Chaque jour, pour animer

sa ferveur, il avait sur les lèvres ces mots: "Bernard, qu'es-tu venu

faire ici?" Il y répondait à chaque fois par des élans nouveaux. Il

réprimait ses sens au point qu'il semblait n'être plus de la terre; voyant, il

ne regardait point, entendant, il n'écoutait point; goûtant, il ne savourait

point. C'est ainsi qu'après avoir passé un an dans la chambre des novices, il

ne savait si le plafond était lambrissé ou non; côtoyant un lac, il ne s'en

aperçut même pas; un jour, il but de l'huile pour de l'eau, sans se douter de

rien.

Bernard avait laissé, au

château de sa famille, Nivard, le plus jeune de ses frères: "Adieu, cher

petit frère, lui avait-il dit; nous t'abandonnons tout notre héritage. – Oui,

je comprends, avait répondu l'enfant, vous prenez le Ciel et vous me laissez la

terre; le partage n'est pas juste." Plus tard, Nivard vint avec son vieux

père rejoindre Bernard au monastère de Clairvaux.

Le Saint n'avait point

étudié dans le monde; mais l'école de l'oraison suffit à faire de lui un grand

Docteur, admirable par son éloquence, par la science et la suavité de ses

écrits. Il fut le conseiller des évêques, l'ami des Papes, l'oracle de son temps.

Mais sa principale gloire, entre tant d'autres, semble être sa dévotion

incomparable envers la très Sainte Vierge.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_bernard.html

Antonio

Vázquez (1485–1563), San Bernardo de Claraval, Primera mitad del

siglo XVI, 119.5 x 50.5, National Sculpture Museum,

Valladolid

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 21 octobre 2009

Saint Bernard

Chers frères et sœurs,

Aujourd'hui je voudrais

parler de saint Bernard de Clairvaux, appelé le dernier des Pères de l'Eglise,

car au XII siècle, il a encore une fois souligné et rendue présente la grande

théologie des pères. Nous ne connaissons pas en détail les années de son

enfance; nous savons cependant qu'il naquit en 1090 à Fontaines en France, dans

une famille nombreuse et assez aisée. Dans son adolescence, il se consacra à

l'étude de ce que l'on appelle les arts libéraux - en particulier de la

grammaire, de la rhétorique et de la dialectique - à l'école des chanoines de

l'église de Saint-Vorles, à Châtillon-sur-Seine et il mûrit lentement la

décision d'entrer dans la vie religieuse. Vers vingt ans, il entra à Cîteaux,

une fondation monastique nouvelle, plus souple par rapport aux anciens et

vénérables monastères de l'époque et, dans le même temps, plus rigoureuse dans

la pratique des conseils évangéliques. Quelques années plus tard, en 1115,

Bernard fut envoyé par saint Etienne Harding, troisième abbé de Cîteaux, pour

fonder le monastère de Clairvaux. C'est là que le jeune abbé (il n'avait que

vingt-cinq ans) put affiner sa propre conception de la vie monastique, et

s'engager à la traduire dans la pratique. En regardant la discipline des autres

monastères, Bernard rappela avec fermeté la nécessité d'une vie sobre et

mesurée, à table comme dans l'habillement et dans les édifices monastiques,

recommandant de soutenir et de prendre soin des pauvres. Entre temps, la

communauté de Clairvaux devenait toujours plus nombreuse et multipliait ses

fondations.

Au cours de ces mêmes

années, avant 1130, Bernard commença une longue correspondance avec de

nombreuses personnes, aussi bien importantes que de conditions sociales

modestes. Aux multiples Lettres de cette période, il faut ajouter les nombreux

Sermons, ainsi que les Sentences et les Traités. C'est toujours à cette époque

que remonte la grande amitié de Bernard avec Guillaume, abbé de Saint-Thierry,

et avec Guillaume de Champeaux, des figures parmi les plus importantes du xii

siècle. A partir de 1130, il commença à s'occuper de nombreuses et graves

questions du Saint-Siège et de l'Eglise. C'est pour cette raison qu'il dut

sortir toujours plus souvent de son monastère, et parfois hors de France. Il

fonda également quelques monastères féminins, et engagea une vive

correspondance avec Pierre le Vénérable, abbé de Cluny, dont j'ai parlé

mercredi dernier. Il dirigea surtout ses écrits polémiques contre Abélard, le

grand penseur qui a lancé une nouvelle manière de faire de la théologie en

introduisant en particulier la méthode dialectique-philosophique dans la

construction de la pensée théologique. Un autre front sur lequel Bernard a

lutté était l'hérésie des Cathares, qui méprisaient la matière et le corps

humain, méprisant en conséquence le Créateur. En revanche, il sentit le devoir

de prendre la défense des juifs, en condamnant les vagues d'antisémitisme

toujours plus diffuses. C'est pour ce dernier aspect de son action apostolique

que, quelques dizaines d'années plus tard, Ephraïm, rabbin de Bonn, adressa un

vibrant hommage à Bernard. Au cours de cette même période, le saint abbé

rédigea ses œuvres les plus fameuses, comme les très célèbres Sermons sur le

Cantique des Cantiques. Au cours des dernières années de sa vie - sa mort

survint en 1153 - Bernard dut limiter les voyages, sans pourtant les

interrompre complètement. Il en profita pour revoir définitivement l'ensemble des

Lettres, des Sermons, et des Traités. Un ouvrage assez singulier, qu'il termina

précisément en cette période, en 1145, quand un de ses élèves Bernardo

Pignatelli, fut élu Pape sous le nom d'Eugène III, mérite d'être mentionné. En

cette circonstance, Bernard, en qualité de Père spirituel, écrivit à son fils

spirituel le texte De Consideratione, qui contient un enseignement en vue

d'être un bon Pape. Dans ce livre, qui demeure une lecture intéressante pour

les Papes de tous les temps, Bernard n'indique pas seulement comment bien faire

le Pape, mais présente également une profonde vision des mystères de l'Eglise

et du mystère du Christ, qui se résout, à la fin, dans la contemplation du

mystère de Dieu un et trine: "On devrait encore poursuivre la recherche de

ce Dieu, qui n'est pas encore assez recherché", écrit le saint abbé:

"mais on peut peut-être mieux le chercher et le trouver plus facilement

avec la prière qu'avec la discussion. Nous mettons alors ici un terme au livre,

mais non à la recherche" (xiv, 32: PL 182, 808), à être en chemin vers

Dieu.

Je voudrais à présent

m'arrêter sur deux aspects centraux de la riche doctrine de Bernard: elles

concernent Jésus Christ et la Très Sainte Vierge Marie, sa Mère. Sa sollicitude

à l'égard de la participation intime et vitale du chrétien à l'amour de Dieu en

Jésus Christ n'apporte pas d'orientations nouvelles dans le statut scientifique

de la théologie. Mais, de manière plus décidée que jamais, l'abbé de Clairvaux

configure le théologien au contemplatif et au mystique. Seul Jésus - insiste

Bernard face aux raisonnements dialectiques complexes de son temps - seul Jésus

est "miel à la bouche, cantique à l'oreille, joie dans le cœur (mel in

ore, in aure melos, in corde iubilum)". C'est précisément de là que vient

le titre, que lui attribue la tradition, de Doctor mellifluus: sa louange de

Jésus Christ, en effet, "coule comme le miel". Dans les batailles

exténuantes entre nominalistes et réalistes - deux courants philosophiques de

l'époque - dans ces batailles, l'Abbé de Clairvaux ne se lasse pas de répéter

qu'il n'y a qu'un nom qui compte, celui de Jésus le Nazaréen. "Aride est

toute nourriture de l'âme", confesse-t-il, "si elle n'est pas baignée

de cette huile; insipide, si elle n'est pas agrémentée de ce sel. Ce que tu écris

n'a aucun goût pour moi, si je n'y ai pas lu Jésus". Et il conclut:

"Lorsque tu discutes ou que tu parles, rien n'a de saveur pour moi, si je

n'ai pas entendu résonner le nom de Jésus" (Sermones in Cantica Canticorum

xv, 6: PL 183, 847). En effet, pour Bernard, la véritable connaissance de Dieu

consiste dans l'expérience personnelle et profonde de Jésus Christ et de son

amour. Et cela, chers frères et sœurs, vaut pour chaque chrétien: la foi est

avant tout une rencontre personnelle, intime avec Jésus, et doit faire

l'expérience de sa proximité, de son amitié, de son amour, et ce n'est qu'ainsi

que l'on apprend à le connaître toujours plus, à l'aimer et le suivre toujours

plus. Que cela puisse advenir pour chacun de nous!

Dans un autre célèbre

Sermon le dimanche entre l'octave de l'Assomption, le saint Abbé décrit en

termes passionnés l'intime participation de Marie au sacrifice rédempteur du

Fils. "O sainte Mère, - s'exclame-t-il - vraiment, une épée a transpercé

ton âme!... La violence de la douleur a transpercé à tel point ton âme que nous

pouvons t'appeler à juste titre plus que martyr, car en toi, la participation à

la passion du Fils dépassa de loin dans l'intensité les souffrances physiques

du martyre" (14: PL 183-437-438). Bernard n'a aucun doute: "per

Mariam ad Iesum", à travers Marie, nous sommes conduits à Jésus. Il

atteste avec clarté l'obéissance de Marie à Jésus, selon les fondements de la

mariologie traditionnelle. Mais le corps du Sermon documente également la place

privilégiée de la Vierge dans l'économie de salut, à la suite de la

participation très particulière de la Mère (compassio) au sacrifice du Fils. Ce

n'est pas par hasard qu'un siècle et demi après la mort de Bernard, Dante

Alighieri, dans le dernier cantique de la Divine Comédie, placera sur les

lèvres du "Doctor mellifluus" la sublime prière à Marie: "Vierge

Mère, fille de ton Fils, / humble et élevée plus qu'aucune autre créature /

terme fixe d'un éternel conseil,..." (Paradis 33, vv. 1ss).

Ces réflexions,

caractéristiques d'un amoureux de Jésus et de Marie comme saint Bernard,

interpellent aujourd'hui encore de façon salutaire non seulement les

théologiens, mais tous les croyants. On prétend parfois résoudre les questions

fondamentales sur Dieu, sur l'homme et sur le monde à travers les seules forces

de la raison. Saint Bernard, au contraire, solidement ancré dans la Bible, et

dans les Pères de l'Eglise, nous rappelle que sans une profonde foi en Dieu

alimentée par la prière et par la contemplation, par un rapport intime avec le

Seigneur, nos réflexions sur les mystères divins risquent de devenir un vain

exercice intellectuel, et perdent leur crédibilité. La théologie renvoie à la

"science des saints", à leur intuition des mystères du Dieu vivant, à

leur sagesse, don de l'Esprit Saint, qui deviennent un point de référence de la

pensée théologique. Avec Bernard de Clairvaux, nous aussi nous devons

reconnaître que l'homme cherche mieux et trouve plus facilement Dieu "avec

la prière qu'avec la discussion". A la fin, la figure la plus authentique

du théologien et de toute évangélisation demeure celle de l'apôtre Jean, qui a

appuyé sa tête sur le cœur du Maître.

Je voudrais conclure ces

réflexions sur saint Bernard par les invocations à Marie, que nous lisons dans

une belle homélie. "Dans les dangers, les difficultés, les incertitudes -

dit-il - pense à Marie, invoque Marie. Qu'elle ne se détache jamais de tes

lèvres, qu'elle ne se détache jamais de ton cœur; et afin que tu puisses

obtenir l'aide de sa prière, n'oublie jamais l'exemple de sa vie. Si tu la

suis, tu ne te tromperas pas de chemin; si tu la pries, tu ne désespéreras pas;

si tu penses à elle, tu ne peux pas te tromper. Si elle te soutient, tu ne

tombes pas; si elle te protège, tu n'as rien à craindre; si elle te guide, tu

ne te fatigues pas; si elle t'est propice, tu arriveras à destination..."

(Hom. II super "Missus est", 17: PL 183, 70-71).

* * *

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins de langue française, particulièrement les jeunes d’Alsace et de

Normandie ainsi que les servants de messe des unités pastorales Notre-Dame et

Sainte-Claire du canton de Fribourg. Que l’enseignement de saint Bernard vous

aide à découvrir toujours plus en Marie la Mère qui protège de toute crainte et

qui nous guide vers son divin Fils. Que Dieu vous bénisse !

© Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Filippino Lippi (1457–1504), Apparition

de la Vierge Marie à Saint Bernard / apparition of

the Virgin to Saint Bernard, 1486, 210 x 195, Badia Fiorentina

Filippino Lippi, Apparizione

della Madonna a

San Bernardo di Chiaravallescrivente (1480 ca.),

tavola; Firenze,

Badia, cappella di

S. Bernardo

BENOÎT XVI

Chers frères et sœurs,

Dans la dernière

catéchèse, j'ai présenté les caractéristiques principales de la théologie

monastique et de la théologie scolastique du xii siècle, que nous pourrions

appeler, d'une certaine manière, respectivement "théologie du cœur"

et "théologie de la raison". Entre les représentants de chacun de ces

courants théologiques s'est développé un vaste débat, parfois animé, représenté

symboliquement par la controverse entre saint Bernard de Clairvaux et Abélard.

Pour comprendre cette

confrontation entre les deux grands maîtres, il est bon de rappeler que la

théologie est la recherche d'une compréhension rationnelle, dans la mesure du

possible, des mystères de la Révélation chrétienne, auxquels on croit dans la

foi: fides quaerens intellectum - la foi cherche

l'intelligibilité - pour reprendre une définition traditionnelle, concise et

efficace. Or, tandis que saint Bernard, typique représentant de la théologie

monastique, met l'accent sur la première partie de la définition, c'est-à-dire

sur la fides - la foi, Abélard, qui est un scolastique, insiste sur

la deuxième partie, c'est-à-dire sur l'intellectus, sur la compréhension

au moyen de la raison. Pour Bernard, la foi elle-même est dotée d'une intime

certitude, fondée sur le témoignage de l'Ecriture et sur l'enseignement des

Pères de l'Eglise. En outre, la foi est renforcée par le témoignage des saints

et par l'inspiration de l'Esprit Saint dans l'âme des croyants. Dans les cas de

doute et d'ambiguïté, la foi est protégée et illuminée par l'exercice du

Magistère ecclésial. Ainsi, Bernard a des difficultés à être d'accord avec

Abélard, et plus généralement avec ceux qui soumettaient les vérités de la foi

à l'examen critique de la raison; un examen qui comportait, à son avis, un

grave danger, c'est-à-dire l'intellectualisme, la relativisation de la vérité,

la remise en question des vérités mêmes de la foi. Dans cette façon de

procéder, Bernard voyait un élan audacieux poussé jusqu'à l'absence de

scrupules, fruit de l'orgueil de l'intelligence humaine, qui prétend

"capturer" le mystère de Dieu. Dans l'une de ses lettres, empli de

douleur, il écrit: "L'esprit humain s'empare de tout, et ne laisse

plus rien à la foi. Il affronte ce qui est au-dessus de lui, il scrute ce qui

lui est supérieur, fait irruption dans le monde de Dieu, altère les mystères de

la foi, au lieu de les illuminer; il n'ouvre pas ce qui est fermé et scellé,

mais le déracine, et ce qu'il considère impossible à parcourir par lui-même, il

le considère comme nul et refuse d'y croire" (Epistola CLXXXVIII,

1; PL 182, I, 353).

Pour Bernard, la

théologie a un unique but: celui de promouvoir l'expérience vivante et

intime de Dieu. La théologie est alors une aide pour aimer toujours plus et

toujours mieux le Seigneur, comme le dit le titre du traité sur le Devoir

d'aimer Dieu (De diligendo Deo). Sur ce chemin, il existe différentes

étapes, que Bernard décrit de façon approfondie, jusqu'au bout, lorsque l'âme

du croyant s'enivre aux sommets de l'amour. L'âme humaine peut atteindre déjà

sur terre cette union mystique avec le Verbe divin, union que le Doctor

Mellifluus décrit comme des "noces spirituelles". Le Verbe divin

la visite, élimine ses dernières résistances, l'illumine, l'enflamme et la

transforme. Dans une telle union mystique, elle jouit d'une grande sérénité et

douceur, et chante à son Epoux un hymne de joie. Comme je l'ai rappelé dans la

catéchèse consacrée à la vie et à la doctrine de saint Bernard, la théologie

pour lui ne peut que se nourrir de la prière contemplative, en d'autres termes

de l'union affective du cœur et de l'esprit avec Dieu.

Abélard, qui est par

ailleurs précisément celui qui a introduit le terme de "théologie" au

sens où nous l'entendons aujourd'hui, se place en revanche dans une perspective

différente. Né en Bretagne, en France, ce célèbre maître du xii siècle était

doué d'une intelligence très vive et l'étude était sa vocation. Il s'occupa

d'abord de philosophie, puis appliqua les résultats obtenus dans cette

discipline à la théologie, dont il fut un maître dans la ville la plus cultivée

de l'époque, Paris, et par la suite dans les monastères où il vécut. C'était un

brillant orateur: ses leçons étaient suivies par de véritables foules

d'étudiants. Un esprit religieux, mais une personnalité inquiète, son existence

fut riche de coups de théâtre: il contesta ses maîtres, eut un enfant

d'une femme cultivée et intelligente, Eloïse. Il entra souvent en polémique

avec ses collègues théologiens, il subit aussi des condamnations

ecclésiastiques, bien qu'il mourût en pleine communion avec l'Eglise, à

l'autorité de laquelle il se soumit avec un esprit de foi. C'est précisément

saint Bernard qui contribua à la condamnation de certaines doctrines d'Abélard

lors du synode provincial de Sens en 1140, et qui sollicita également

l'intervention du Pape Innocent II. L'abbé de Clairvaux contestait, comme nous

l'avons rappelé, la méthode trop intellectualiste d'Abélard, qui, à ses yeux,

réduisait la foi à une simple opinion détachée de la vérité révélée. Les

craintes de Bernard n'étaient pas infondées et elles étaient partagées, du

reste, également par d'autres grands penseurs de l'époque. En effet, un recours

excessif à la philosophie rendit dangereusement fragile la doctrine trinitaire

d'Abélard, et par conséquent, son idée de Dieu. Dans le domaine moral, son

enseignement n'était pas dépourvu d'ambiguïtés: il insistait pour

considérer l'intention du sujet comme l'unique source pour décrire la bonté ou

la méchanceté des actes moraux, en négligeant ainsi la signification et la

valeur morale objectives des actions: un subjectivisme dangereux. C'est

là - nous le savons bien - un aspect très actuel pour notre époque, où la

culture apparaît souvent marquée par une tendance croissante au relativisme

éthique: seul le moi décide ce qui serait bon pour moi, en ce moment.

Quoi qu'il en soit, il ne faut pas non plus oublier les grands mérites

d'Abélard, qui eut de nombreux disciples et contribua de manière décisive au

développement de la théologie scolastique, destinée à s'exprimer de manière

plus mûre et féconde au siècle suivant. Pas plus qu'il ne faut sous-évaluer

certaines de ses intuitions, comme par exemple lorsqu'il affirmait que, dans

les traditions religieuses non chrétiennes, il y a déjà une préparation à

l'accueil du Christ, Verbe divin.

Que pouvons-nous

apprendre, aujourd'hui, de la confrontation, aux tons souvent enflammés, entre

Bernard et Abélard, et, en général, entre la théologie monastique et la

théologie scolastique? Je crois tout d'abord que cette confrontation montre

l'utilité et la nécessité d'une saine discussion théologique dans l'Eglise,

surtout lorsque les questions débattues n'ont pas été définies par le

Magistère, qui reste, cependant, un point de référence inéluctable. Saint

Bernard, mais également Abélard lui-même, en reconnurent toujours sans

hésitation l'autorité. En outre, les condamnations que ce dernier subit nous

rappellent que dans le domaine théologique doit exister un équilibre entre ce

que nous pouvons appeler les principes architectoniques qui nous sont donnés

par la Révélation et qui conservent donc toujours l'importance prioritaire, et

les principes interprétatifs suggérés par la philosophie, c'est-à-dire par la

raison, et qui ont une fonction importante mais uniquement instrumentale. Quand

cet équilibre entre l'architecture et les instruments d'interprétation fait

défaut, la réflexion théologique risque d'être entachée par des erreurs, et

c'est alors au Magistère que revient l'exercice de ce service nécessaire à la

vérité, qui lui est propre. En outre, il faut souligner que, parmi les

motivations qui poussèrent Bernard à "se ranger" contre Abélard et à

solliciter l'intervention du Magistère, il y eut également la préoccupation de

sauvegarder les croyants simples et humbles, qui doivent être défendus

lorsqu'ils risquent d'être confondus ou égarés par des opinions trop

personnelles et par des argumentations théologiques anticonformistes, qui

pourraient mettre leur foi en péril.

Je voudrais enfin

rappeler que la confrontation théologique entre Bernard et Abélard se conclut

par une pleine réconciliation entre les deux hommes, grâce à la médiation d'un

ami commun, l'abbé de Cluny, Pierre le Vénérable, dont j'ai parlé dans l'une

des catéchèses précédentes. Abélard montra de l'humilité en reconnaissant ses

erreurs, Bernard fit preuve d'une grande bienveillance. Chez tous les deux

prévalut ce qui doit vraiment tenir à cœur lorsque naît une controverse

théologique, c'est-à-dire sauvegarder la foi de l'Eglise et faire triompher la

vérité dans la charité. Que ce soit aujourd'hui aussi l'attitude avec laquelle

on se confronte avec l'Eglise, en ayant toujours comme objectif la recherche de

la vérité.

* * *

Je suis heureux de saluer

les pèlerins de langue française, venant notamment de France, de Suisse et de

Belgique. Que votre pèlerinage à Rome soit une occasion pour approfondir votre

foi afin de donner une place centrale à la personne du Christ dans votre vie.

Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique!

© Copyright 2009 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Gregorio Fernández, Le

Christ en croix embrassant Saint Bernard Clairvaux, 1613,

blo mayor. Iglesia del Monasterio de las

Huelgas Reales, Valladolid

Répondre à l’amour de

Dieu

Dieu notre Époux n’est

pas seulement aimant : il est l’amour. N’est-il pas aussi l’honneur ?

L’affirme qui voudra ; pour moi, je ne l’ai lu nulle part. J’ai lu

que Dieu est amour ; je n’ai pas lu qu’il est honneur.

Certes, à Dieu seul

l’honneur et la gloire (cf. 1 Tm 1, 17) ; mais Dieu n’acceptera ni

l’un ni l’autre, s’ils n’ont pas été assaisonnés du miel de l’amour. L’amour se

suffit à lui-même, il plaît par lui-même et pour lui-même. Il est à

lui-même son mérite, à lui-même sa récompense. L’amour ne cherche pas hors de

lui-même ni sa cause ni son fruit : en jouir, voilà son fruit. J’aime

parce que j’aime ; j’aime pour aimer. Grande chose que l’amour, si du

moins il remonte à son principe, s’il retourne à son origine, s’il reflue vers

sa source pour y puiser sans cesse son pérenne jaillissement. De tous les

mouvements de l’âme, de ses sentiments et de ses affections, l’amour est le

seul qui permette à la créature de répondre au Créateur, sinon d’égal à égal,

du moins dans une réciprocité de ressemblance. Par exemple, si Dieu se met en

colère contre moi, riposterai-je par une colère semblable ? Non, certes,

mais je craindrai, je tremblerai, j’implorerai le pardon. Quand Dieu aime, il

ne veut rien d’autre que d’être aimé. Car il n’aime que pour être aimé, sachant

que ceux qui l’aimeront seront bienheureux par cet amour même.

St Bernard de Clairvaux

Consulté par les princes

et les papes, saint Bernard († 1153), moine de Cîteaux, a fait rayonner,

au xiie siècle, l’ordre cistercien dans toute l’Europe.

/ Sermons sur le Cantique 83, 4, trad. R. Fassetta, Paris, Cerf,

Sources Chrétiennes 511, 2007, p. 347-349.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/mercredi-5-janvier/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

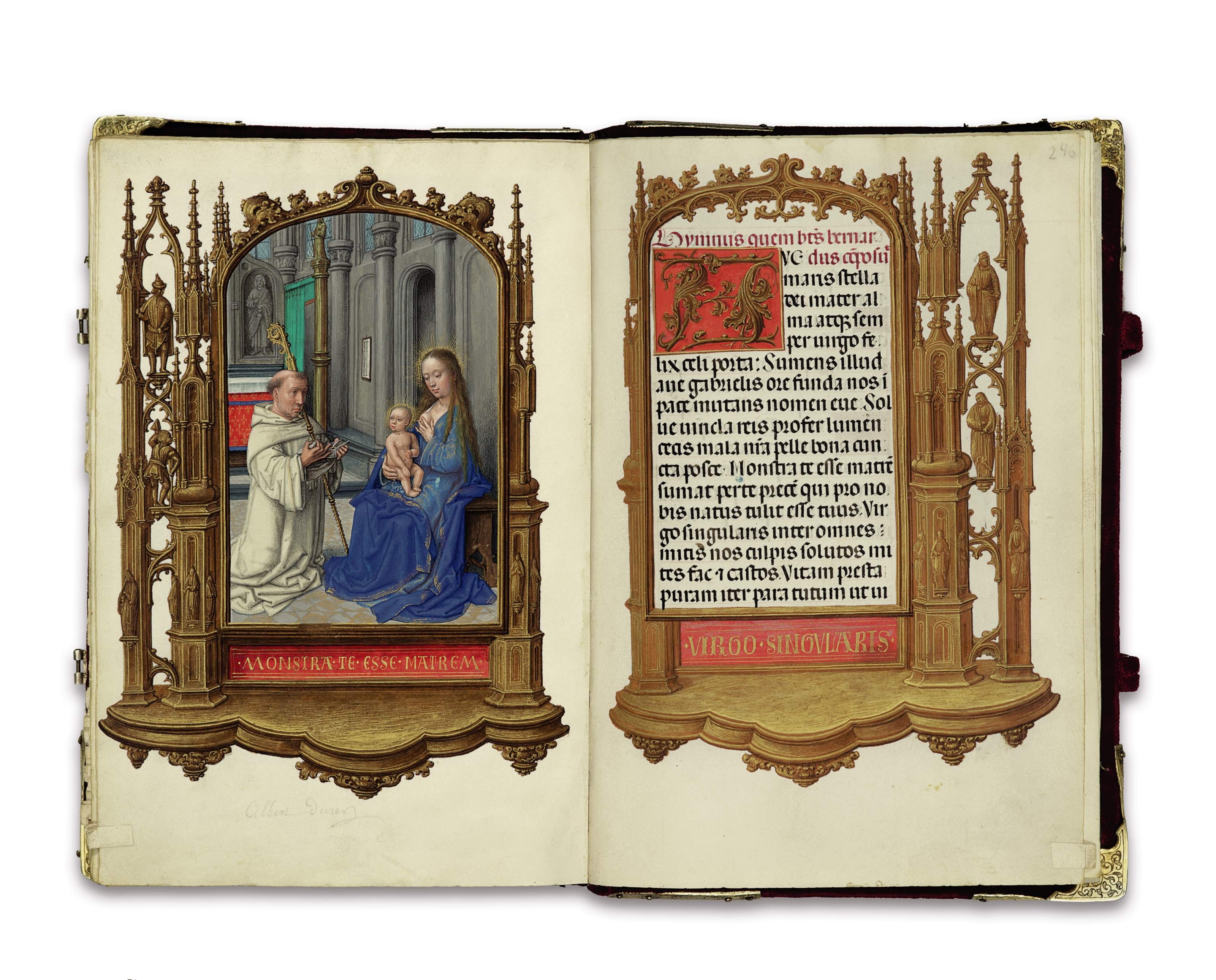

Saint

Bernard Heures d'Étienne Chevalier, enluminées par Jean Fouquet Musée

Condé, Chantilly, R.-G. Ojeda, RMN / musée Condé, Chantilly Dans la salle

capitulaire, saint Bernard s'adresse à ses frères. Les expressions et attitudes

corporelles des huit moines qui l'écoutent sont des plus variées. Nul n'entend

ni ne contemple les mots de cet éloquent prêcheur de la même manière. Le geste

d'énumération de saint Bernard fait sans doute référence à l'épisode évoqué en

dessous. Le diable, vaincu par la ténacité de saint Bernard, lui révèle enfin

les sept vers du Psautier, dont la simple récitation quotidienne assure le

salut de l'homme.

Pourquoi sept

pains ?

Je vais vous dire quels

sont les sept pains qui doivent vous donner des forces. Le premier, c’est le

pain de la parole de Dieu qui est la vie de l’homme, ainsi qu’il l’atteste

lui-même (cf. Mt 4, 4). Le second est celui de l’obéissance, c’est encore

Jésus qui nous l’assure en disant : « Ma nourriture est de faire

la volonté de celui qui m’a envoyé » (Jn 4, 34). Le troisième pain

est la sainte méditation, car c’est d’elle qu’il est écrit : « La

sainte méditation te conservera » ; et qu’il semble qu’on doit

entendre ce que l’auteur sacré appelle un pain de vie et

d’intelligence (Si 15, 3). Le quatrième pain, c’est le don des larmes

unies à la piété. Le cinquième, c’est le travail de la pénitence. Il ne faut

pas vous étonner si je donne ce nom de pain au travail et aux larmes, car vous

n’avez point oublié, je pense, que le prophète a dit : Seigneur, tu

nous nourriras d’un pain de larmes (Ps 79, 6) ; et

ailleurs : C’est du labeur de tes mains que tu mangeras :

heureux es-tu, à toi le bonheur (Ps 127, 2). Le sixième pain est la douce

union qui fait de nous un seul corps ; c’est, en effet, un pain fait de

grains nombreux, et dont la grâce de Dieu a été le levain. Quant au septième

pain, c’est le pain eucharistique, car le Seigneur a dit : « Le

pain que je vous donnerai, c’est ma propre chair que je dois livrer pour la vie

du monde » (Jn 6, 51).

St Bernard de Clairvaux

Consulté par les princes

et les papes, saint Bernard († 1153), moine de Cîteaux, a fait rayonner,

au xiie siècle, l’ordre cistercien dans toute l’Europe. / Œuvres

complètes, t. 3, Paris, Vivès, 1867, p. 290.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-12-fevrier/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Illustration

du Liber de sancto Benedicto (ca 1437) - Jean de Stavelot (1388-1449)

20 août: Saint Bernard

De 1973 à 1977, j'étais

novice à l'abbaye cistercienne d'Oka, près de Montréal. C'est là que j'ai

découvert saint Bernard et la spiritualité cistercienne. Figure importante de

l’Occident chrétien, Bernard de Clairvaux demeure actuel aujourd’hui. Sa

doctrine, comme ses actes, reflète les inspirations d’une nature mystique et

contemplative, prompte à s’irriter contre tout ce qui peut éloigner de Dieu.

Celui qui a donné le véritable envol à l’Ordre cistercien ne dissocie jamais le

discours de l’expérience, la théologie de la spiritualité. Pour certains, il

est le dernier des Pères de l’Église par sa connaissance amoureuse de la Bible,

de la liturgie et de la tradition.

L’aventure cistercienne

Bernard de Clairvaux est

né en 1090 dans une famille noble, au château de Fontaine, près de Dijon. Son

père, Tescelin, était le seigneur de Fontaine et chevalier du duc de Bourgogne.

Sa mère, dame Aleth de Montbard, sera vénérée comme bienheureuse. Ils eurent de

nombreux enfants. À la mort de sa mère en 1112, Bernard entre avec trente

compagnons, frères et cousins, à l’abbaye

de Citeaux, fondée en 1098 par saint Robert. Le monastère était dirigé par

saint Étienne Harding.

Après quinze années de

dur labeur à construire le monastère, il n’y avait qu’une poignée de moines, et

plusieurs doutaient de plus en plus du bien-fondé de leur mission :

revenir à la pureté de la Règle

de saint Benoît. Le nouveau monastère avait besoin de jeunes hommes en

santé qui délaisseraient les fêtes, les joutes et les guerres pour affronter le

désert de Cîteaux. Aussi est-ce avec grand soulagement que l’abbé Étienne voit

arriver Bernard et ses amis. Son père et ses autres frères le suivront plus

tard.

En 1115, Bernard est

chargé de fonder l’abbaye

de Clairvaux, la claire vallée. Il y restera abbé jusqu’à sa mort. Assoiffé

de contemplation, il sera pourtant appelé à parcourir les chemins de l’Europe.

Au concile de Troyes, il reconnaît l’Ordre des Templiers et rédige leur Règle

de Vie.

Un guerrier spirituel

À partir de 1130, Bernard

règle les conflits qui existent dans la papauté, ralliant le roi de France et

l’empereur d’Allemagne à la cause de l’unité de l’Église. Homme de vérité, il

s’oppose au théologien Abélard,

l’amant d’Héloïse, et obtient sa condamnation au concile de Sens, en 1140. Il

conseille le pape Eugène III, ancien moine de Clairvaux, qui lui demande de

prêcher la seconde croisade. Sa voix est si forte à Vézelay qu’on l’entend très

loin dans les champs. À Noël 1146, il prêche à Spire. Il intervient à Mayence

pour empêcher les massacres de juifs par les fanatiques. On le consulte de

partout.

Durant ce temps, de

nouvelles abbayes cisterciennes surgissent un peu partout en Europe. Celui

qu’on appelle le second fondateur de l’Ordre cistercien meurt en 1153. Il

laisse derrière lui plus de 160 moines à Clairvaux, tandis que la nouvelle

famille cistercienne compte près de 350 abbayes. Grand meneur d’âmes, animateur

de la vie spirituelle, conseiller des évêques, gloire du XIIe siècle,

Bernard est canonisé en 1173 par le pape Alexandre III, puis déclaré docteur de

l’Église par Pie VIII en 1830. L’oraison du jour de sa fête, le 20 août, résume

bien la place déterminante qu’il occupa dans l’Église et le zèle qui le

dévorait : « Seigneur, tu as voulu que saint Bernard, rempli d’amour

pour ton Église, soit dans ta maison la lampe qui brûle et qui éclaire;

accorde-nous, par son intercession, la même ferveur de l’esprit, afin de vivre

comme des fils de la lumière. »

La connaissance amoureuse

de Dieu

Saint Bernard a non

seulement vécu intensément, il a aussi beaucoup écrit. Ce fin lettré a une

plume alerte qui suit le mouvement de son cœur aimanté au Christ et à Marie, sa

Dame qu’il aime beaucoup. Vrai chercheur de Dieu, il se livre à une

connaissance amoureuse de Dieu, qu’il traduit dans une prose superbe. Le

traité de l’amour de Dieu et ses quatre-vingt-six Sermons sur le

Cantique des cantiques, chant nuptial où il décrit l’union mystique de

l’âme-épouse avec le Verbe-époux, demeurent des œuvres d’une grande beauté

littéraire et d’une profondeur spirituelle où transparaît son désir de Dieu.

Ce désir caractérise la

nature humaine et grandit avec l’alternance de présence et d’absence de l’Époux

dans l’âme et dans l’Église. Il décrit à merveille ce cache-cache divin dans sa

somme de théologie spirituelle que sont ses Sermons sur le Cantique des

cantiques. Pour Bernard, influencé par saint Augustin, « l’amour est à

soi-même son mérite et sa récompense ». Il écrit : « La raison

d’aimer Dieu, c’est Dieu même; la mesure de l’aimer, c’est de l’aimer sans

mesure. »

Le saint moine montre que

l’être humain est par nature capable de s’unir à Dieu. L’unique moyen pour y

arriver est l’amour, ce qui implique une connaissance de soi-même et de Dieu.

Il écrit dans son Traité de l’amour de Dieu : « Mon Dieu,

mon soutien, je vous aimerai pour tout ce que vous m’avez donné, avec ma mesure

qui, certes, ne correspond pas à celle qui vous est due en justice, mais qui,

cependant, n’est pas au-dessous de ce que je peux. »

Le troubadour de Notre

Dame

L’enseignement de saint

Bernard aura une grande postérité dans l’Église. Sa mystique nuptiale inspirera

la vie carmélitaine. Sa vie d’oraison, axée sur la méditation des mystères de

Jésus, aura une influence sur les franciscains. L’art roman, où sont

privilégiés le silence et la lumière, doit beaucoup à saint Bernard. Et que

dire de sa grande dévotion à Marie, à qui il réserve de beaux chants d’amour.

Il ajouta ces dernières paroles au Salve Regina : « Ô

clémente, ô toute belle, ô douce Vierge Marie. » Il nomme Marie

« l’étoile de la mer » :

"Regarde l’étoile,

appelle Marie. Dans les périls, les angoisses et les doutes, pense à Marie,

invoque Marie. Que son nom ne s’éloigne jamais de tes lèvres, qu’il ne

s’éloigne pas de ton cœur; et, pour obtenir le secours de sa prière, ne néglige

pas l’exemple de sa vie. En la suivant, tu es sûr de ne pas dévier, en la priant,

de ne pas désespérer; en la consultant, de ne pas te tromper."

Pour aller plus loin, ma

biographie Saint

Bernard de Clairvaux (Le Figaro / Presses de la Renaissance).

Les

saints, ces fous admirables (Novalis / Béatitudes).

SOURCE : https://www.jacquesgauthier.com/blog/entry/20-aout-saint-bernard.html

Bernard

de Clairvaux recevant le lait de la Vierge (Lactatio),

MS

Douce 264, f.38v. the Bodleian Library, Oxford

La curieuse histoire de

la lactation de saint Bernard de Clairvaux

Domitille

Farret d'Astiès - Publié le 29/03/18

Une légende raconte que

saint Bernard de Clairvaux que nous fêtons ce 20 août a reçu un jet de lait

directement du sein de la Vierge.

Connaissez-vous

l’histoire de la lactation de saint Bernard de Clairvaux ? Certains sont

sceptiques, d’autres la boivent comme du petit lait. Mais que l’on soit

crédule, tempéré ou soupe-au-lait, cette histoire ne compte pas pour du beurre,

encore moins en cette journée mondiale de l’allaitement.

Au XIIe siècle, ce

bourguignon, conseiller des rois et des papes, réforma la vie religieuse

catholique et notamment l’ordre

des cisterciens . On raconte qu’un beau jour, alors que le bon

moine faisait ses dévotions devant une statue de la Vierge ,

il prononça ces mots audacieux: Monstra te esse

matrem (Montrez-vous une mère). En guise de réponse, la

sculpture se serait alors animée et la Vierge aurait propulsé du lait dans la

bouche du saint assoiffé d’amour maternel… Une façon d’affirmer en actes sa

maternité spirituelle. Une biographie du XVIIe siècle explique que ce

geste généreux provoque chez lui « une douceur et un ravissement d’esprit

extraordinaires ».

Lire aussi :

Redécouvrez

saint Bernard de Clairvaux !

Plus prosaïquement, il

est probable que des figures littéraires employées par le saint, auteur parmi

les plus prolifiques de son temps, soit à la source d’une confusion … et d’une

légende volontiers reprend par des peintres les siècles

suivants. Plusieurs variantes existent d’ailleurs au sujet de cette fameuse

« lactation » et, compte tenu du sujet, les représentations de ce

« miracle » variant au grès des époques et des régions. Ce qui

est certain, c’est que ce miracle n’est pas mentionné dans la Légende

dorée de Jacques de Voragine. De quoi émettre quelques réserves sur

son authenticité.

Il n’en demeure pas moins

que saint Bernard de Clairvaux, surnommé parfois « le chantre de

Marie », nous a laissé de magnifiques prières mariales. Cette beauté

ne laisse cette fois aucun doute sur la sainteté de Bernard de Clairvaux et sa

relation toute particulière avec la Vierge Marie:

«Lorsque vous assaillent

les vents des tentations, lorsque vous voyez paraître les écueils du malheur,

regardez l’étoile, invoquez Marie. Si vous êtes ballottés sur les vagues de

l’orgueil, de l’ambition, de la calomnie, de la jalousie, regardez l’étoile,

invoquez Marie. Si la colère, l’avarice, les séductions charnelles viennent

secouer la légère embarcation de votre âme, levez les yeux vers Marie. Dans le

péril, l’angoisse, le doute, pensez à Marie, invoquez Marie. Que son nom ne

quitte ni vos lèvres ni vos cœurs! Et pour obtenir son intercession, ne vous

détournez pas de son exemple. En la suivante, vous ne vous égarerez pas. En la

suppliant, vous ne connaîtrez pas le désespoir. En pensant à elle, vous

éviterez toute erreur. Si elle vous soutient, vous ne sombrerez pas; si elle

vous protège, vous n’aurez rien à craindre; sous sa conduite vous ignorerez la

fatigue; grâce à sa faveur, vous atteindrez le mais. Ainsi soit-il. »Louanges à

Marie – Deuxième Homélie de Saint Bernard

L'Étoile de la mer est une étoile lumineuse et très belle, dont les rayons illuminent le monde entier, dont la splendeur brille dans les cieux et pénètre les enfers ; elle illumine le monde et réchauffe les âmes... Ô toi qui te vois ballotté dans le courant de ce siècle au milieu des orages et des tempêtes, ne détourne pas les yeux de l'éclat de cet astre. Si les vents de la tentation s'élèvent, si tu es submergé par l'orgueil, l'ambition, la trahison et l'envie, regarde l'Étoile, invoque Marie.

[...]

Si, accablé par l'énormité de tes crimes, confus de la laideur de ta conscience, effrayé par l'horreur du jugement, tu commences à t'enfoncer dans le gouffre de la tristesse et du désespoir, pense à Marie. Dans les dangers, dans les difficultés, dans les perplexités, pense à Marie, invoque Marie. Que ce nom ne s'éloigne ni de tes lèvres, ni de ton coeur. En la suivant, tu ne dévieras point ; en la priant, tu ne pourras désespérer ; en pensant à elle, tu éviteras l'erreur. Qu'elle te tienne, plus de chute ; qu'elle te protège, plus de crainte ; si elle te guide, plus de fatigue ; si elle t'est favorable, tu seras sûr d'arriver.

Saint Bernard de Clairvaux

Portait de Bernard de Clairvaux dans une lettrine ornant un manuscrit de La Légende dorée, vers 1267-1276

Saint Bernard de

Clairvaux

Mort le 20 août 1153.

Canonisé en 1174 par Alexandre III. Culte interne à l’ordre cistercien,

toutefois il est inscrit au calendrier de la Curie Romaine en 1255.

St Pie V en fait une fête double en 1568. En 1830, Pie VIII le proclame

Docteur.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Bernard

naquit à Fontaine, en Bourgogne, d’une noble famille. Dans sa jeunesse, il fut,

à cause de sa grande beauté, vivement sollicité par des femmes, mais aucune ne

réussit à ébranler sa résolution de garder la chasteté. Pour fuir ces

tentations du diable, il prit, à l’âge de vingt-deux ans, le parti d’entrer à

Cîteaux, berceau de l’Ordre de ce nom, qui florissait alors par une grande

sainteté. Ayant ou connaissance du projet de Bernard, ses frères mirent tous

leurs efforts à l’en détourner ; mais, dans cette lutte, il fut le plus

éloquent et le plus heureux ; car il les amena si bien, eux et d’autres, à sa

manière de voir, que trente jeunes gens reçurent avec lui l’habit religieux.

Devenu moine, il s’adonna tellement au jeûne, que chaque fois qu’il prenait son

repas, il semblait endurer un supplice. Merveilleusement appliqué aux veilles

et aux oraisons prolongées, voué à la pratique de la pauvreté chrétienne, il

menait sur terre une vie presque céleste, étrangère aux sollicitudes et aux

désirs des choses périssables.

Cinquième leçon. En lui

brillaient l’humilité, la miséricorde, la douceur ; il était si attaché à la

contemplation, qu’il semblait ne se servir de ses sens que pour les devoirs de

la piété, en quoi cependant il se comportait avec la plus louable prudence.

Pendant qu’il s’appliquait à ces exercices, il refusa successivement les

évêchés de Gênes, de Milan, et plusieurs autres qui lui furent offerts, se

déclarant indigne de l’honneur d’une telle dignité. Élu Abbé de Clairvaux, il

construisit en beaucoup de lieux des monastères où se maintinrent longtemps la

règle et la discipline du fondateur. Le monastère des Saints Vincent et

Anastase à Rome ayant été restauré par le Pape Innocent II, Bernard y établit

comme Abbé le religieux qui, plus tard, devint souverain Pontife sous le nom

d’Eugène III. C’est à ce Pape qu’il adressa son livre De la Considération.

Sixième leçon. Bernard a

écrit beaucoup d’autres ouvrages, dans lesquels se montre une doctrine inspirée

par la grâce divine plutôt qu’acquise par l’étude. Sa grande réputation de

vertu le fit appeler par les plus grands princes pour trancher leurs différends

; il dut aussi aller souvent en Italie pour régler les affaires de l’Église. Le

souverain Pontife Innocent II eut en lui un aide précieux, tant pour mettre un

terme au schisme suscité par Pierre de Léon, que dans ses légations près de

l’empereur d’Allemagne, d’Henri, roi d’Angleterre, et du concile de Pisé.

Enfin, à l’âge de soixante-trois ans, il s’endormit dans le Seigneur. Des

miracles le glorifièrent et Alexandre III le mit au rang des Saints. Le

souverain Pontife Pie VIII, de l’avis de la Congrégation des Rites, déclara

saint Bernard Docteur de l’Église universelle, et ordonna en même temps qu’on

dirait, le jour de sa fête, l’Office et la Messe des Docteurs. Il concéda aussi

à perpétuité des indulgences plénières annuelles à tous ceux qui visiteraient

ce jour-là les églises des Cisterciens.

Au troisième nocturne. Du

Commun.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Matthieu. Cap. 5, 13-19.

En ce temps-là : Jésus

dit à ses disciples : Vous êtes le sel de la terre. Mais si le sel s’affadit,

avec quoi le salera-t-on ? Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Jean

Chrysostome. Homil. 15 in Matth., sub med.

Septième leçon. Remarquez

ce que dit Jésus-Christ : « Vous êtes le sel de la terre ». Il montre par là

combien il est nécessaire qu’il donne ces préceptes à ses Apôtres. Car, ce

n’est pas seulement, leur dit-il, de votre propre vie, mais de l’univers entier

que vous aurez à rendre compte. Je ne vous envoie pas comme j’envoyais les

Prophètes, à deux, à dix, ou à vingt villes ni à une seule nation, mais à toute

la terre, à la mer, et au monde entier, à ce monde accablé sous le poids de

crimes divers.

Huitième leçon. En disant

: « Vous êtes le sel de la terre », il montre que l’universalité des hommes

était comme affadie et corrompue par une masse de péchés ; et c’est pourquoi il

demande d’eux les vertus qui sont surtout nécessaires et utiles pour procurer

le salut d’un grand nombre. Celui qui est doux, modeste, miséricordieux et

juste, ne peut justement se borner à renfermer ces vertus en son âme, mais il

doit avoir soin que ces sources excellentes coulent aussi pour l’avantage des

autres. Ainsi celui qui a le cœur pur, qui est pacifique et qui souffre

persécution pour la vérité, dirige-sa vie d’une manière utile à tous.

Neuvième leçon. Ne croyez

donc point, dit-il, que ce soit à de légers combats que vous serez conduits, et

que ce soient des choses de peu d’importance dont il vous faudra prendre soin

et rendre compte, « vous êtes le sel de la terre ». Quoi donc ? Est-ce que les

Apôtres ont guéri ce qui était déjà entièrement gâté ? Non certes ; car il ne

se peut faire que ce qui tombe déjà en putréfaction soit rétabli dans son

premier état par l’application du sel. Ce n’est donc pas cela qu’ils ont fait,

mais ce qui était auparavant renouvelé et à eux confié, ce qui était délivré

déjà de cette pourriture, ils y répandaient le sel et le conservaient dans cet

état de rénovation qui est une grâce reçue du Seigneur. Délivrer de la

corruption du péché, c’est l’effet de la puissance du Christ ; empêcher que les

hommes ne retournent au péché, voilà ce qui réclame les soins et les labeurs

des Apôtres.

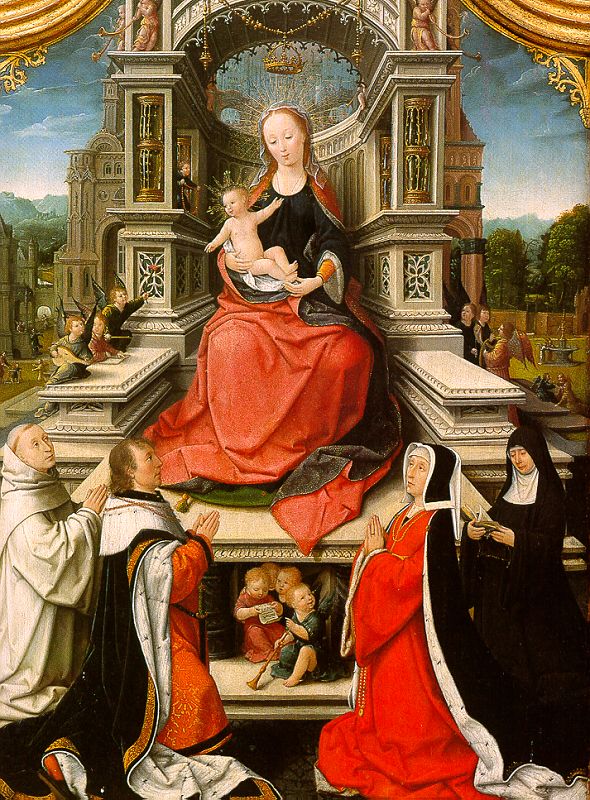

Jehan Bellegambe, Triptyque du Cellier (vers

1509), New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sainte Humbeline, sœur de Bernard et Jeanne de

Boubais, abbesse de l'abbaye de Flines, aux pieds de la Vierge à l'Enfant - Description

sur le site du Metropolitan Museum qui accueille l'œuvre. [archive] ; A. G. Pearson « [archive] Nuns, images, and the ideals of

women's monasticism: Two paintings from the Cistercian convent of

Flines », Renaissance Quarterly, 22 décembre 2001

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Le val d’absinthe a perdu

ses poisons. Devenu Clairvaux, la claire vallée, il illumine le monde ; de tous

les points de l’horizon, les abeilles vigilantes y sont attirées par le miel du

rocher [1] qui déborde en sa solitude. Le regard de Marie s’est abaissé sur ces

collines sauvages ; avec son sourire, la lumière et la grâce y sont descendues.

Une voix harmonieuse, celle de Bernard, l’élu de son amour, s’est élevée du

désert ; elle disait : « Connais, ô homme, le conseil de Dieu ; admire les vues

de la Sagesse, le dessein de l’amour. Avant que d’arroser toute l’aire, il

inonde la toison [2] ; voulant racheter le genre humain, il amasse en Marie la

rançon entière. O Adam, ne dis plus : La femme que vous m’avez donnée m’a

présenté du fruit défendu [3] ; dis plutôt : La femme que vous m’avez donnée

m’a nourri d’un fruit de bénédiction. De quelle ardeur faut-il que nous

honorions Marie, en qui la plénitude de tout bien fut déposée ! S’il est en

nous quelque espérance, quelque grâce de salut, sachons qu’elle déborde de

celle qui aujourd’hui s’élève inondée d’amour : jardin de délices, que le divin

Auster n’effleure pas seulement d’un souffle rapide, mais sur lequel il fond

des hauteurs et qu’il agite sans fin de la céleste brise, pour qu’en tous lieux

s’en répandent les parfums [4], qui sont les dons des diverses grâces. Ôtez ce

soleil matériel qui éclaire le monde : où sera le jour ? Ôtez Marie, l’étoile

de la vaste mer : que restera-t-il, qu’obscurité enveloppant tout, nuit de

mort, glaciales ténèbres ? Donc, par toutes les fibres de nos cœurs, par tous

les amours de notre âme, par tout l’élan de nos aspirations, vénérons Marie ;

car c’est la volonté de Celui qui a voulu que nous eussions tout par elle »

[5].

Ainsi parlait ce moine

dont l’éloquence, nourrie, comme il le disait, parmi les hêtres et les chênes

des forêts [6], ne savait que répandre sur les plaies de son temps le vin et

l’huile des Écritures. En 1113, âgé de vingt-deux ans, Bernard abordait Cîteaux

dans la beauté de son adolescence mûrie déjà pour les grands combats. Quinze

ans s’étaient écoulés depuis le 21 mars 1098, où Robert de Molesmes avait créé

entre Dijon et Beaune le désert nouveau. Issue du passé en la fête même du

patriarche des moines, la fondation récente ne se réclamait que de l’observance

littérale de la Règle précieuse donnée par lui au monde. Pourtant l’infirmité

du siècle se refusait à reconnaître, dans l’effrayante austérité des derniers

venus de la grande famille, l’inspiration du très saint code où la discrétion

règne en souveraine [7], le caractère de l’école accessible à tous, où Benoît «

espérait ne rien établir de rigoureux ni de trop pénible au service du Seigneur

» [8]. Sous le gouvernement d’Étienne Harding, successeur d’Albéric qui

lui-même avait remplacé Robert, la petite communauté partie de Molesmes allait

s’éteignant, sans espoir humain de remplir ses vides, quand l’arrivée du

descendant des seigneurs de Fontaines, entouré des trente compagnons sa

première conquête, fit éclater la vie où déjà s’étendait la mort.

Réjouis-toi, stérile qui

n’enfantais pas ; voilà que vont se multiplier les fils de la délaissée [9]. La

Ferté, fondée cette année même dans le Châlonnais, voit après elle Pontigny

s’établir près d’Auxerre, en attendant qu’au diocèse de Langres Clairvaux et Morimond

viennent compléter, dans l’année 1115, le quaternaire glorieux des filles de

Cîteaux qui, avec leur mère, produiront partout des rejetons sans nombre.

Bientôt (1119) la Charte de charité va consacrer l’existence de l’Ordre

Cistercien dans l’Église ; l’arbre planté six siècles plus tôt au sommet du

Cassin, montre une fois de plus au monde qu’à tous les âges il sait s’orner de

nouvelles branches qui, sans être la tige, vivent de sa sève et sont la gloire

de l’arbre entier.

Durant les mois de son

noviciat cependant, Bernard a tellement dompté la nature, que l’homme intérieur

vit seul en lui ; les sens de son propre corps lui demeurent comme étrangers.

Par un excès toutefois qu’il se reprochera [10], la rigueur déployée dans le

but d’obtenir un résultat si désirable a ruiné ce corps, indispensable

auxiliaire de tout mortel dans le service de ses frères et de Dieu. Heureux

coupable, que le ciel se chargera d’excuser lui-même magnifiquement ! Mais le

miracle, sur lequel tous ne peuvent ni ne doivent compter, pourra seul le

soutenir désormais dans l’accomplissement de la mission qui l’attend.

Bernard est ardent pour

Dieu comme d’autres le sont pour leurs passions. « Vous voulez apprendre de

moi, s’écrie-t-il dans un de ses premiers ouvrages, pourquoi et comment il faut

aimer Dieu. Et moi, je vous réponds : La raison d’aimer Dieu, c’est Dieu même ;

la mesure de l’aimer, c’est de l’aimer sans mesure » [11]. Quelles délices

furent les siennes à Cîteaux, dans le secret de la face du Seigneur [12] !

Lorsque, après deux ans, il quitta ce séjour béni pour fonder Clairvaux, ce fut

la sortie du paradis. Moins fait pour converser avec les hommes qu’avec les

Anges, il commença, nous dit son historien, par être l’épreuve de ceux qu’il

devait conduire : tant son langage était d’en haut, tant ses exigences de

perfection dépassaient la force même de ces forts d’Israël, tant son étonnement

se manifestait douloureux à la révélation des infirmités qui sont la part de

toute chair [13].

Outrance de l’amour,

eussent dit nos anciens, qui lui réservait d’autres surprises. Mais

l’Esprit-Saint veillait sur le vase d’élection appelé à porter devant les

peuples et les rois le nom du Seigneur [14] ; la divine charité qui consumait

cette âme, lui fit comprendre, avec leurs durs contrastes, les deux objets

inséparables de l’amour : Dieu, dont la bonté en fournit le motif, l’homme,

dont la misère en est l’exercice éprouvant. Selon la remarque naïve de

Guillaume de Saint-Thierry, son disciple et ami, Bernard réapprit l’art de

vivre avec les humains [15] ; il se pénétra des admirables recommandations du

législateur des moines, quand il dit de l’Abbé établi sur ses frères : « Dans

les corrections même, qu’il agisse avec prudence et sans excès, de crainte

qu’en voulant trop racler la rouille, le vase ne se brise. En imposant les

travaux, qu’il use de discernement et de modération, se rappelant la discrétion

du saint patriarche Jacob, qui disait : Si je fatigue mes troupeaux en les

faisant trop marcher, ils périront tous en un jour [16]. Faisant donc son

profit de cet exemple et autres semblables sur la discrétion, qui est la mère

des vertus, qu’il tempère tellement toutes choses que les forts désirent faire

davantage, et que les faibles ne se découragent pas » [17].

En recevant ce que le

Psalmiste appelle l’intelligence de la misère du pauvre [18], Bernard sentit

son cœur déborder de la tendresse de Dieu pour les rachetés du sang divin. Il

n’effraya plus les humbles. Près des petits qu’attirait la grâce de ses

discours, vinrent se ranger les sages, les puissants, les riches du siècle,

abandonnant leurs vanités, devenus eux-mêmes petits et pauvres à l’école de

celui qui savait les conduire tous des premiers éléments de l’amour à ses

sommets. Au milieu des sept cents moines recevant de lui chaque jour la

doctrine du salut, l’Abbé de Clairvaux pouvait s’écrier avec la noble fierté

des saints : « Celui qui est puissant a fait en nous de grandes choses, et

c’est à bon droit que notre âme magnifie le Seigneur. Voici que nous avons tout

quitté pour vous suivre [19] : grande résolution, gloire des grands Apôtres ;

mais nous aussi, par sa grande grâce, nous l’avons prise magnifiquement. Et

peut-être même qu’en cela encore, si je veux me glorifier, ce ne sera pas folie

; car je dirai la vérité : il y en a ici qui ont laissé plus qu’une barque et

des filets » [20].

Et dans une autre

circonstance : « Quoi de plus admirable, disait-il, que de voir celui qui

autrefois pouvait deux jours à peine s’abstenir du péché, s’en garder des

années et sa vie entière ? Quel plus grand miracle que celui de tant de jeunes

hommes, d’adolescents, de nobles personnages, de tous ceux enfin que j’aperçois

ici, retenus sans liens dans une prison ouverte, captifs de la seule crainte de

Dieu, et qui persévèrent dans les macérations d’une pénitence au delà des

forces humaines, au-dessus de la nature, contraire à la coutume ? Que de

merveilles nous pourrions trouver, vous le savez bien, s’il nous était permis

de rechercher par le détail ce que furent pour chacun la sortie de l’Égypte, la

route au désert, l’entrée au monastère, la vie dans ses murs [21] ! »

Mais d’autres merveilles

que celles dont le cloître garde le secret au Roi des siècles, éclataient déjà

de toutes parts. La voix qui peuplait les solitudes, avait par delà

d’incomparables échos. Le monde, pour l’écouter, s’arrêta sur la pente qui

conduit aux abîmes. Assourdie des mille bruits discordants de l’erreur, du

schisme et des passions, on vit l’humanité se taire une heure aux accents

nouveaux dont la mystérieuse puissance l’enlevait à son égoïsme, et lui rendait

pour les combats de Dieu l’unité des beaux jours. Suivrons-nous dans ses

triomphes le vengeur du sanctuaire, l’arbitre des rois, le thaumaturge acclamé

des peuples ? Mais c’est ailleurs que Bernard a placé son ambition et son

trésor [22] ; c’est au dedans qu’est la vraie gloire [23]. Ni la sainteté, ni

le mérite, ne se mesurent devant Dieu au succès ; et cent miracles ne valent

pas, pour la récompense, un seul acte d’amour. Tous les sceptres inclinés

devant lui, l’enivrement des foules, la confiance illimitée des Pontifes, il

n’est rien, dans ces années de son historique grandeur, qui captive la pensée

de Bernard, bien plutôt qui n’irrite la blessure profonde de sa vie, celle

qu’il reçut au plus intime de l’âme, quand il lui fallut quitter cette solitude

à laquelle il avait donné son cœur.

A l’apogée de cet éclat

inouï éclipsant toute grandeur d’alors, quand, docile à ses pieds, une première

fois soumis par lui au Christ en son vicaire, l’Occident tout entier est jeté

par Bernard sur l’infidèle Orient dans une lutte suprême, entendons ce qu’il

dit : « Il est bien temps que je ne m’oublie pas moi-même. Ayez pitié de ma

conscience angoissée : quelle vie monstrueuse que la mienne ! Chimère de mon

siècle, ni clerc ni laïque, je porte l’habit d’un moine et n’en ai plus les

observances. Dans les périls qui m’assiègent, au bord des précipices qui

m’attirent, secourez-moi de vos conseils, priez pour moi » [24].

Absent de Clairvaux, il

écrit à ses moines : « Mon âme est triste ; elle ne sera point consolée qu’elle

ne vous retrouve. Faut-il, hélas ! que mon exil d’ici-bas, si longtemps

prolongé, s’aggrave encore ? Véritablement ils ont ajouté douleur sur douleur à

mes maux, ceux qui nous ont séparés. Ils m’ont enlevé le seul remède qui me fit

supporter d’être sans le Christ ; en attendant de contempler sa face glorieuse,

il m’était donné du moins de vous voir, vous son saint temple De ce temple, le

passage me semblait facile à l’éternelle patrie. Combien souvent cette

consolation m’est ôtée ! C’est la troisième fois, si je ne me trompe, qu’on

m’arrache mes entrailles. Mes enfants sont sevrés avant le temps ; je les avais

engendrés par l’Évangile, et je ne puis les nourrir. Contraint de négliger ce

qui m’est cher, de m’occuper d’intérêts étrangers, je ne sais presque ce qui

m’est le plus dur, ou d’être enlevé aux uns, ou d’être mêlé aux autres. Jésus,

ma vie doit-elle donc tout entière s’écouler dans les gémissements ? Il m’est

meilleur de mourir que de vivre ; mais je voudrais ne mourir qu’au milieu des

miens ; j’y trouverais plus de douceur, plus de sûreté. Plaise à mon Seigneur

que les yeux d’un père, si indigne qu’il se reconnaisse de porter ce nom,

soient fermés de la main de ses fils ; qu’ils l’assistent dans le dernier

passage : que leurs désirs, si vous l’en jugez digne, élèvent son âme au séjour

bienheureux ; qu’ils ensevelissent le corps d’un pauvre avec les corps de ceux

qui furent pauvres comme lui. Par la prière, par le mérite de mes frères, si

j’ai trouvé grâce devant vous, accordez-moi ce vœu ardent de mon cœur. Et

pourtant, que votre volonté se fasse, et non la mienne ; car je ne veux ni vivre

ni mourir pour moi » [25].

Plus grand dans son

abbaye qu’au milieu des plus nobles cours, saint Bernard en effet devait y

mourir à l’heure voulue de Dieu, non sans avoir vu l’épreuve publique [26] et

privée [27] préparer son âme à la purification suprême. Une dernière fois il

reprit sans les achever ses entretiens de dix-huit années sur le Cantique,

conférences familières recueillies pieusement par la plume de ses fils, et où

se révèlent d’une manière si touchante le zèle des enfants pour la divine

science, le cœur du père et sa sainteté, les incidents de la vie de chaque jour

à Clairvaux [28]. Arrivé au premier verset du troisième chapitre, il décrivait

la recherche du Verbe par l’âme dans l’infirmité de cette vie, dans la nuit de

ce monde [29], quand son discours interrompu le laissa dans l’éternel face à

face, où cessent toute énigme, toute figure et toute ombre.

Offrons à saint Bernard cette

Hymne aux naïves allusions, bien digne de lui pour la suavité gracieuse avec

laquelle elle chante ses grandeurs.

HYMNE.

Lacte quondam

profluentes,

Ite, montes, vos procul,

Ite, colles, fusa quondam

Unde mellis flumina ;

Isræl, jactare late

Manna priscum desine.

Ecce cujus corde sudant,

Cuius ore profluunt

Dulciores lacte fontes,

Mellis amnes æmuli :

Ore tanto, corde tanto

Manna nullum dulcius.

Quæris unde duxit ortum

Tanta lactis copia ;

Unde favus, unde prompta

Tanta mellis suavitas ;

Unde tantum manna fluxit,

Unde tot dulcedines.

Lactis imbres Virgo fudit

Cœlitus puerpera :

Mellis amnes os leonis

Excitavit mortui :

Manna sylvæ, cœlitumque

Solitudo proxima.

Doctor o Bernarde, tantis

Aucte cœli dotibus,

Lactis hujus, mellis hujus,

Funde rores desuper ;

Funde stillas, pleniore

Jam potitus gurgite.

Monts qui jadis laissiez

le lait

s’échapper des rochers,

disparaissez au loin ;

disparaissez, collines

dont les pentes

autrefois répandaient le

miel en ruisseaux ;

Israël, cesse de vanter

l’antique manne par le

monde.

Voici quelqu’un de qui le

cœur

verse des flots plus doux

que le lait,

de qui la bouche épand

des ondes rivales du miel

:

nulle manne plus suave

que

cette noble bouche, que

ce grand cœur.

Vous demandez d’où prend

sa source

un lait de si grande

abondance,

d’où provient le rayon

d’où se distille un miel

de telle suavité,

d’où pareille manne a

pris naissance,

d’où coulent enfin tant

de douceurs,

La pluie de lait, c’est

la Vierge Mère

qui du ciel l’a répandue

;

les flots de miel ont

leur origine

dans la gueule d’un lion

mort ;

les forêts, la solitude

voisine des cieux,

ont produit la manne.

O Bernard, ô Docteur

enrichi d’en haut de tels

dons,

versez sur nous la rosée

de ce lait, de ce miel ;

versez les gouttes,

maintenant que leur plénitude,

maintenant que la mer est

à vous.

Soit louange souveraine

au Père souverain,

souveraine à son Fils ;

pareille à vous, Esprit-Saint

qui procédez de l’un et

de l’autre :

comme il était, et

maintenant,

et toujours, gloire égale

à jamais.

Amen.

Il convenait que l’on vît

le héraut de la Mère de Dieu suivre de près son char de triomphe ; et c’est

avec délices qu’entrant au ciel en l’Octave radieuse, vous vous perdez dans la

gloire de celle dont vous proclamiez ici-bas les grandeurs. Protégez-nous à sa

cour ; inclinez vers Cîteaux ses yeux maternels ; en son nom, sauvez encore

l’Église et défendez le Vicaire de l’Époux.

Mais en ce jour, vous

nous conviez, plutôt que de vous implorer vous-même, à la chanter, à la prier

avec vous ; l’hommage que vous agréez le plus volontiers, ô Bernard, est de

nous voir mettre à profit vos écrits sublimes pour admirer « celle qui monte

aujourd’hui glorieuse, et porte au comble le bonheur des habitants des cieux.

Si brillant déjà, le ciel resplendit d’un éclat nouveau à la lumière du

flambeau virginal. Aussi, dans les hauteurs, retentissent l’action de grâces et

la louange. Ne faut-il pas faire nôtres, en notre exil, ces allégresses de la

patrie ? Sans demeure permanente, nous cherchons la cité où la Vierge bénie

parvient à cette heure. Citoyens de Jérusalem, il est bien juste que, de la

rive des fleuves de Babylone, nous en ayons souvenir et dilations nos cœurs au

débordement du fleuve de félicité dont les gouttelettes rejaillissent aujourd’hui

jusqu’à la terre. Notre Reine a pris les devants ; la réception qui lui est

faite nous donne confiance à nous sa suite et ses serviteurs. Notre caravane,

précédée de la Mère de miséricorde, à titre d’avocate près du Juge son Fils,

aura bon accueil dans l’affaire du salut [30].

« Qu’il taise votre

miséricorde, Vierge bienheureuse, celui qui se rappelle vous avoir invoquée en

vain dans ses nécessités ! Pour nous, vos petits serviteurs, nous applaudissons

à vos autres vertus ; mais de celle-ci, c’est nous que nous félicitons. Nous

louons en vous la virginité, nous admirons votre humilité ; mais la miséricorde

a pour les malheureux plus de douceur, nous l’embrassons plus chèrement, nous

la rappelons plus fréquemment, nous l’invoquons sans trêve. Qui dira, ô bénie,

la longueur, la largeur, la hauteur, la profondeur de la vôtre ? Sa longueur,

elle s’étend jusqu’au dernier jour ; sa largeur, elle couvre la terre ; sa

hauteur et sa profondeur, elle a rempli le ciel et vidé l’enfer. Aussi

puissante que miséricordieuse, ayant maintenant recouvré votre Fils, manifestez

au monde la grâce que vous avez trouvée devant Dieu : obtenez le pardon au

pécheur, la santé à l’infirme, force pour les pusillanimes, consolation pour

les affligés, secours et délivrance pour ceux que menace un péril quelconque

[31],ô clémente, ô miséricordieuse, ô douce Vierge Marie [32] ! »

[1] Deut. XXXII, 13.

[2] Judic. VI, 37-40.

[3] Gen. III, 12.

[4] Cant. IV, 16.

[5] Bernard. Sermo in

Nativ. B. M.

[6] Vita Bernardi, I, IV,

23.

[7] Greg. Dialog. II,

XXXVI.

[8] S. P. Benedict. in

Reg. Prolog.

[9] Isai. LIV, 1.

[10] Vita, I, VIII, 41.

[11] De diligendo Deo, I,

1.

[12] Psalm. XXX, 13.

[13] Vita, I, VI, 27-30.

[14] Act. IX, 15.

[15] Vita, I, VI, 30.

[16] Gen. XXXIII, 13.

[17] S. P. Benedict. Reg.

LXIV.

[18] Psalm. XL, 2.

[19] Matth. XIX, 27.

[20] Bern. De Diversis,

Sermo XXXVII, 7.

[21] In Dedicat. Eccl.

Sermo 1, 2.

[22] Matth. VI, 21.

[23] Psalm. XLIV, 14.

[24] Epist. CCL.

[25] Epist. CXLI.

[26] De Consideratione,

II, I, 1-4.

[27] Epist. CCXCVIII,

etc.

[28] In Cantica, Sermon.

I, 1 ; III, 6 ; XXVI, 3-14 ; XXXVI, 7 ; XLIV, 8 ; LXXIV, 1-7 ; etc.

[29] Ibid. Sermo LXXXVI,

4.

[30] Bernard. In Assumpt

B. V. M. Sermo 1.

[31] Bernard. In Assumpt.

B. M. V. Sermo IV.

[32] On sait que la

tradition de la cathédrale de Spire attribue à saint Bernard l’addition de ces

trois cris du cœur au Salve Regina.

Bhx cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Dans la basilique

transtévérine de Sainte-Marie, sur le tympan du tombeau du pape Innocent II,

l’on voit un moine vêtu de blanc, qui ramène le Pontife à Rome et le fait

asseoir triomphalement sur le trône de saint Pierre. Ce moine est saint

Bernard, abbé de Clairvaux.

Figure vraiment

grandiose, Bernard fut en même temps réformateur de la vie monastique, apôtre

de la Croisade, docteur de l’Église universelle, thaumaturge, pacificateur des

rois, des princes et des peuples, oracle des Papes et champion du pontificat

romain contre les schismes et les hérésies. Son corps, épuisé par les pénitences

et les maladies, arrivait à grand’peine à retenir une âme toute de feu pour la

gloire de Dieu. Ce feu brûlait autour de lui, en sorte que ses secrétaires ne

suffisaient pas à enregistrer toutes les guérisons miraculeuses qu’il opérait

par le seul attouchement de sa main ou par sa simple bénédiction.

Les nécessités de

l’Église amenèrent plusieurs fois saint Bernard à descendre en Italie et à

venir à Rome. On lui doit la restauration de l’abbaye ad aquas Salvias, sur la

voie Laurentine, où il établit comme abbé ce Bernard de Pise, qui devint

ensuite Eugène III.

Les relations du maître

avec son ancien disciple devenu pape sont admirables. Bernard ne peut oublier

son rôle paternel vis-à-vis de l’âme du Pontife, et pour l’aider à bien

méditer, il lui adresse son ouvrage De Consideratione, qui, avec le Pastoral de

saint Grégoire le Grand, ne manqua jamais de figurer, jusqu’au XVIe siècle,

dans la bibliothèque de l’appartement pontifical.

La messe est celle des

Docteurs, sauf la première lecture, commune à la fête de saint Léon Ier. En

effet, saint Bernard refusa constamment, par humilité, les honneurs de

l’épiscopat qui lui avait été offert plusieurs fois. Son activité de docteur

s’exerça en grande partie dans l’enceinte de son abbaye, où il prêchait assidûment

aux moines, leur commentant les divines Écritures. Cet aspect spécial de

l’activité de saint Bernard est en parfaite relation avec la règle du

Patriarche saint Benoît, qui conçoit le monastère comme une Dominici schola

servitii, où l’abbé doit prodiguer sans cesse son enseignement spirituel aux

moines.

Les disciples de saint

Bernard furent très nombreux et se distinguèrent par une grande sainteté. Parmi

eux se trouvent ses parents et ses frères, qui le suivirent dans le cloître. On

raconte que, quand saint Bernard, suivi de trente membres de sa famille attirés

par lui au monastère, fut sur le point d’abandonner le château paternel, il dit

à son petit frère Nivard qui jouait dans la cour : « Adieu, Nivard, nous te

laissons tous ces biens que tu vois alentour ». Mais l’enfant, avec une sagesse

bien supérieure à son âge, répondit : « Ce partage n’a pas été fait avec

justice. Comment ! Vous me laissez la terre et vous prenez le ciel ? » Et il

voulait les suivre, lui aussi, au monastère, mais on lui en refusa l’entrée

jusqu’à un âge plus mûr.

Notons une pensée

expressive de saint Bernard, sur la nécessité de la sainteté en un ministre de

Dieu, qui, si non placet, non placat.

Philippe Quantin, Saint Bernard écrivant, huile

sur toile, musée des beaux-arts de Dijon,

- provient

de la chapelle du collège des Gaudrans de Dijon. Saisie révolutionnaire,

au musée en 1799. INV. CA 443

Dom Pius Parsch, Le

guide dans l’année liturgique

Le Docteur melliflue.

1. Saint Bernard. — Jour

de mort : 20 août 1153, à l’âge de 62 ans. Tombeau : Dans l’église abbatiale de

Clairvaux (devant l’autel de la Très Sainte Vierge). Vie : Saint Bernard, le

second fondateur de l’Ordre des Cisterciens, est surnommé le Docteur «

melliflue » (Doctor mellifluus). Ses sermons, que nous trouvons en grande

partie au bréviaire, sont remarquables par la profondeur extraordinaire du

sentiment. On lui attribue l’admirable « Memorare ». Saint Bernard est né, en

1090, d’une famille de vieille noblesse bourguignonne ; il entra à 22 ans au

monastère de Cîteaux, berceau de l’Ordre des Cisterciens, et détermina 30

jeunes gens de son rang à le suivre. Il fut bientôt promu abbé de Clairvaux

(1115) et construisit de nombreux monastères dans lesquels survécut pendant

longtemps son esprit. Son élève, Bernard de Pise, devint pape plus tard sous le

nom d’Eugène III ; c’est à lui qu’il dédia son ouvrage, écrit en toute

franchise, le « De consideratione ». Il exerça une puissante influence sur les

princes, le clergé et le peuple de son temps. Il fut aussi un apôtre zélé de la

croisade.

2. La messe (In medio)

est du commun des docteurs toutefois avec une leçon propre qui a rapport à la

vie contemplative du saint moine. Nous voyons Bernard prier pendant la nuit ;

avec sa famille monacale il observe les veilles nocturnes ; nous le voyons