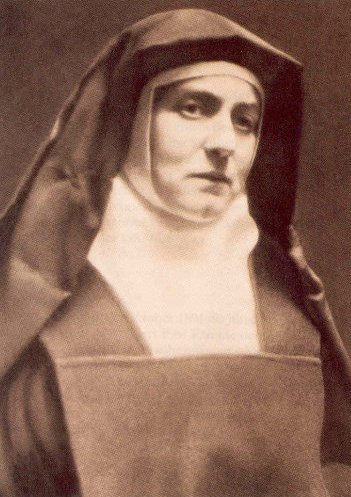

Thérèse-Bénédicte

de la Croix Edith Stein (1891-1942)

"Inclinons-nous profondément devant ce témoignage

de vie et de mort livré par Edith Stein, cette remarquable fille d'Israël, qui

fut en même temps fille du Carmel et soeur Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix, une

personnalité qui réunit pathétiquement, au cours de sa vie si riche, les drames

de notre siècle. Elle est la synthèse d'une histoire affligée de blessures

profondes et encore douloureuses, pour la guérison desquelles s'engagent,

aujoud'hui encore, des hommes et des femmes conscients de leurs responsabilités;

elle est en même temps la synthèse de la pleine vérité sur les hommes, par son

coeur qui resta si longtemps inquiet et insatisfait, "jusqu'à ce qu'enfin

il trouvât le repos dans le Seigneur" ". Ces paroles furent

prononcées par le Pape Jean-Paul II à l'occasion de la béatification d'Édith

Stein à Cologne, le 1 mai 1987.

Qui fut cette femme?

Quand, le 12 octobre 1891, Édith Stein naquit à

Wroclaw (à l'époque Breslau), la dernière de 11 enfants, sa famille fêtait le

Yom Kippour, la plus grande fête juive, le jour de l'expiation. "Plus que

toute autre chose cela a contribué à rendre particulièrement chère à la mère sa

plus jeune fille". Cette date de naissance fut pour la carmélite presque

une prédiction.

Son père, commerçant en bois, mourut quand Édith

n'avait pas encore trois ans. Sa mère, femme très religieuse, active et

volontaire, personne vraiment admirable, restée seule, devait vaquer aux soins

de sa famille et diriger sa grande entreprise; cependant elle ne réussit pas à

maintenir chez ses enfants une foi vivante. Édith perdit la foi en Dieu:

"En pleine conscience et dans un choix libre je cessai de prier".

Elle obtint brillamment son diplôme de fin d'études

secondaires en 1911 et commença des cours d'allemand et d'histoire à

l'Université de Wroclaw, plus pour assurer sa subsistance à l'avenir que par

passion. La philosophie était en réalité son véritable intérêt. Elle

s'intéressait également beaucoup aux questions concernant les femmes. Elle

entra dans l'organisation "Association Prussienne pour le Droit des Femmes

au Vote". Plus tard elle écrira: "Jeune étudiante, je fus une

féministe radicale. Puis cette question perdit tout intérêt pour moi.

Maintenant je suis à la recherche de solutions purement objectives".

En 1913, l'étudiante Édith Stein se rendit à Gôttingen

pour fréquenter les cours de Edmund Husserl à l'université; elle devint son

disciple et son assistante et elle passa aussi avec lui sa thèse. À l'époque

Edmund Husserl fascinait le public avec son nouveau concept de vérité: le monde

perçu existait non seulement à la manière kantienne de la perception

subjective. Ses disciples comprenaient sa philosophie comme un retour vers le

concret. "Retour à l'objectivisme". La phénoménologie conduisit

plusieurs de ses étudiants et étudiantes à la foi chrétienne, sans qu'il en ait

eu l'intention. À Gôttingen, Édith Stein rencontra aussi le philosophe Max

Scheler. Cette rencontre attira son attention sur le catholicisme. Cependant

elle n'oublia pas l'étude qui devait lui procurer du pain dans l'avenir. En

janvier 1915, elle réussit avec distinction son examen d'État. Elle ne commença

pas cependant sa période de formation professionnelle.

Alors qu'éclatait la première guerre mondiale, elle

écrivit: "Maintenant je n'ai plus de vie propre". Elle fréquenta un

cours d'infirmière et travailla dans un hôpital militaire autrichien. Pour elle

ce furent des temps difficiles. Elle soigna les malades du service des maladies

infectieuses, travailla en salle opératoire, vit mourir des hommes dans la

fleur de l'âge. À la fermeture de l'hôpital militaire en 1916, elle suivit

Husserl à Fribourg-en-Brisgau, elle y obtint en 1917 sa thèse "summa cum

laudae" dont le titre était: "Sur le problème de l'empathie".

Il arriva qu'un jour elle put observer comment une femme

du peuple, avec son panier à provisions, entra dans la cathédrale de Francfort

et s'arrêta pour une brève prière. "Ce fut pour moi quelque chose de

complètement nouveau. Dans les synagogues et les églises protestantes que j'ai

fréquentées, les croyants se rendent à des offices. En cette circonstance

cependant, une personne entre dans une église déserte, comme si elle se rendait

à un colloque intime. Je n'ai jamais pu oublier ce qui est arrivé". Dans

les dernières pages de sa thèse elle écrit: "Il y a eu des individus qui,

suite à un changement imprévu de leur personnalité, ont cru rencontrer la

miséricorde divine". Comment est-elle arrivée à cette affirmation?

Édith Stein était liée par des liens d'amitié profonde

avec l'assistant de Husserl à Gôtingen, Adolph Reinach, et avec son épouse.

Adolf Reinach mourut en Flandres en novembre 1917. Édith se rendit à Gôttingen.

Le couple Reinach s'était converti à la foi évangélique. Édith avait une

certaine réticence à l'idée de rencontrer la jeune veuve. Avec beaucoup

d'étonnement elle rencontra une croyante. "Ce fut ma première rencontre

avec la croix et avec la force divine qu'elle transmet à ceux qui la portent

[...] Ce fut le moment pendant lequel mon irréligiosité s'écroula et le Christ

resplendit". Plus tard elle écrivit: "Ce qui n'était pas dans mes

plans était dans les plans de Dieu. En moi prit vie la profonde conviction que

-vu du côté de Dieu- le hasard n'existe pas; toute ma vie, jusque dans ses

moindres détails, est déjà tracée selon les plans de la providence divine et,

devant le regard absolument clair de Dieu, elle présente une unité parfaitement

accomplie".

À l'automne 1918, Édith Stein cessa d'être

l'assistante d'Edmund Husserl. Ceci parce qu'elle désirait travailler de

manière indépendante. Pour la première fois depuis sa conversion, Édith Stein

rendit visite à Husserl en 1930. Elle eut avec lui une discussion sur sa

nouvelle foi à laquelle elle aurait volontiers voulu qu'il participe. Puis elle

écrit de manière surprenante: "Après chaque rencontre qui me fait sentir

l'impossibilité de l'influencer directement, s'avive en moi le caractère

pressant de mon propre holocauste".

Édith Stein désirait obtenir l'habilitation à

l'enseignement. À l'époque, c'était une chose impossible pour une femme. Husserl

se prononça au moment de sa candidature: "Si la carrière universitaire

était rendue accessible aux femmes, je pourrais alors la recommander

chaleureusement plus que n'importe quelle autre personne pour l'admission à

l'examen d'habilitation". Plus tard on lui interdira l'habilitation à

cause de ses origines juives.

Édith Stein retourna à Wroclaw. Elle écrivit des

articles sur la psychologie et sur d'autres disciplines humanistes. Elle lit

cependant le Nouveau Testament, Kierkegaard et le livre des exercices de saint

Ignace de Loyola. Elle s'aperçoit qu'on ne peut seulement lire un tel écrit, il

faut le mettre en pratique.

Pendant l'été 1921, elle se rendit pour quelques

semaines à Bergzabern (Palatinat), dans la propriété de Madame Hedwig

Conrad-Martius, une disciple de Husserl. Cette dame s'était convertie, en même

temps que son époux, à la foi évangélique. Un soir, Édith trouva dans la

bibliothèque l'autobiographie de Thérèse d'Avila. Elle la lut toute la nuit.

"Quand je refermai le livre je me dis: ceci est la vérité".

Considérant rétrospectivement sa propre vie, elle écrira plus tard: "Ma

quête de vérité était mon unique prière".

Le ler janvier 1922, Édith Stein se fit baptiser.

C'était le jour de la circoncision de Jésus, de l'accueil de Jésus dans la

descendance d'Abraham. Édith Stein était debout devant les fonds baptismaux,

vêtue du manteau nuptial blanc de Hedwig Conrad-Martius qui fut sa marraine.

"J'avais cessé de pratiquer la religion juive et je me sentis de nouveau

juive seulement après mon retour à Dieu". Maintenant elle sera toujours

consciente, non seulement intellectuellement mais aussi concrètement, d'appartenir

à la lignée du Christ. À la fête de la Chandeleur, qui est également un jour

dont l'origine remonte à l'Ancien Testament, elle reçut la confirmation de

l'évêque de Spire dans sa chapelle privée.

Après sa conversion, elle se rendit tout d'abord à

Wroclaw. "Maman, je suis catholique". Les deux se mirent à pleurer.

Hedwig Conrad-Martius écrivit: "Je vis deux israélites et aucune ne manque

de sincérité" (cf Jn 1, 47).

Immédiatement après sa conversion, Édith aspira au

Carmel, mais ses interlocuteurs spirituels, le Vicaire général de Spire et le

Père Erich Przywara, S.J., l'empêchèrent de faire ce pas. Jusqu'à pâques 1931

elle assura alors un enseignement en allemand et en histoire au lycée et

séminaire pour enseignants du couvent dominicain de la Madeleine de Spire. Sur

l'insistance de l'archiabbé Raphaël Walzer du couvent de Beuron, elle

entreprend de longs voyages pour donner des conférences, surtout sur des thèmes

concernant les femmes. "Pendant la période qui précède immédiatement et

aussi pendant longtemps après ma conversion [... ] je croyais que mener une vie

religieuse signifiait renoncer à toutes les choses terrestres et vivre

seulement dans la pensée de Dieu. Progressivement cependant, je me suis rendue

compte que ce monde requiert bien autre chose de nous [...]; je crois même que

plus on se sent attiré par Dieu et plus on doit "sortir de soi-même",

dans le sens de se tourner vers le monde pour lui porter une raison divine de

vivre".

Son programme de travail est énorme. Elle traduit les

lettres et le journal de la période pré-catholique de Newman et l'œuvre "

Questiones disputatx de veritate " de Thomas d'Aquin et ce dans une

version très libre, par amour du dialogue avec la philosophie moderne. Le Père

Erich Przywara S.J. l'encouragea à écrire aussi des oeuvres philosophiques

propres. Elle apprit qu'il est possible "de pratiquer la science au

service de Dieu [... ] ; c'est seulement pour une telle raison que j'ai pu me

décider à commencer une série d'oeuvres scientifiques". Pour sa vie et

pour son travail elle trouve toujours les forces nécessaires au couvent des

bénédictins de Beuron où elle se rend pour passer les grandes fêtes de l'année

liturgique.

En 1931, elle termina son activité à Spire. Elle tenta

de nouveau d'obtenir l'habilitation pour enseigner librement à Wroclaw et à

Fribourg. En vain. À partir de ce moment, elle écrivit une oeuvre sur les

principaux concepts de Thomas d'Aquin: "Puissance et action". Plus

tard, elle fera de cet essai son ceuvre majeure en l'élaborant sous le titre

"Être fini et Être éternel", et ce dans le couvent des Carmélites à

Cologne. L'impression de l'œuvre ne fut pas possible pendant sa vie.

En 1932, on lui donna une chaire dans une institution

catholique, l'Institut de Pédagogie scientifique de Münster, où elle put développer

son anthropologie. Ici elle eut la possibilité d'unir science et foi et de

porter à la compréhension des autres cette union. Durant toute sa vie, elle ne

veut être qu'un "instrument de Dieu". "Qui vient à moi, je

désire le conduire à Lui".

En 1933, les ténèbres descendent sur l'Allemagne.

"J'avais déjà entendu parler des mesures sévères contres les juifs. Mais

maintenant je commençai à comprendre soudainement que Dieu avait encore une

fois posé lourdement sa main sur son peuple et que le destin de ce peuple était

aussi mon destin". L'article de loi sur la descendance arienne des nazis

rendit impossible la continuation de son activité d'enseignante. "Si ici

je ne peux continuer, en Allemagne il n'y a plus de possibilité pour moi".

"J'étais devenue une étrangère dans le monde".

L'archiabbé Walzer de Beuron ne l'empêcha plus

d'entrer dans un couvent des Carmélites. Déjà au temps où elle se trouvait à

Spire, elle avait fait les veeux de pauvreté, de chasteté et d'obéissance. En

1933 elle se présenta à la Mère Prieure du monastère des Carmélites de Cologne.

"Ce n'est pas l'activité humaine qui peut nous aider, mais seulement la

passion du Christ. J'aspire à y participer".

Encore une fois Édith Stein se rendit à Wroclaw pour

prendre congé de sa mère et de sa famille. Le dernier jour qu'elle passa chez

elle fut le 12 octobre, le jour de son anniversaire et en même temps celui de

la fête juive des Tabernacles. Édith accompagna sa mère à la Synagogue. Pour

les deux femmes ce ne fut pas une journée facile. "Pourquoi l'as-tu connu

(Jésus Christ)? Je ne veux rien dire contre Lui. Il aura été un homme bon. Mais

pourquoi s'est-il fait Dieu?" Sa mère pleure.

Le lendemain matin Édith prend le train pour Cologne.

"Je ne pouvais entrer dans une joie profonde. Ce que je laissais derrière

moi était trop terrible. Mais j'étais très calme - dans l'intime de la volonté

de Dieu". Par la suite elle écrira chaque semaine une lettre à sa mère.

Elle ne recevra pas de réponses. Sa soeur Rose lui enverra des nouvelles de la

maison.

Le 14 octobre, Édith Stein entre au monastère des

Carmélites de Cologne. En 1934, le 14 avril, ce sera la cérémonie de sa prise

d'habit. L'archiabbé de Beuron célébra la messe. À partir de ce moment Édith

Stein portera le nom de soeur Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix.

En 1938, elle écrivit: "Sous la Croix je compris

le destin du peuple de Dieu qui alors (1933) commençait à s'annoncer. Je

pensais qu'il comprenait qu'il s'agissait de la Croix du Christ, qu'il devait

l'accepter au nom de tous les autres peuples. Il est certain qu'aujourd'hui je

comprends davantage ces choses, ce que signifie être épouse du Seigneur sous le

signe de la Croix. Cependant il ne sera jamais possible de comprendre tout

cela, parce que c'est un mystère".

Le 21 avril 1935, elle fit des voeux temporaires. Le

14 septembre 1936, au moment du renouvellement des voeux, sa mère meurt à

Wroclaw. "Jusqu'au dernier moment ma mère est restée fidèle à sa religion.

Mais puisque sa foi et sa grande confiance en Dieu [...] furent l'ultime chose

qui demeura vivante dans son agonie, j'ai confiance qu'elle a trouvé un juge

très clément et que maintenant elle est ma plus fidèle assistante, en sorte que

moi aussi je puisse arriver au but".

Sur l'image de sa profession perpétuelle du 21 avril

1938, elle fit imprimer les paroles de saint Jean de la Croix auquel elle

consacrera sa dernière oeuvre: "Désormais ma seule tâche sera

l'amour".

L'entrée d'Édith Stein au couvent du Carmel n'a pas

été une fuite. "Qui entre au Carmel n'est pas perdu pour les siens, mais

ils sont encore plus proches; il en est ainsi parce que c'est notre tâche de

rendre compte à Dieu pour tous". Surtout elle rend compte à Dieu pour son

peuple. "Je dois continuellement penser à la reine Esther qui a été

enlevée à son peuple pour en rendre compte devant le roi. Je suis une petite et

faible Esther mais le Roi qui m'a appelée est infiniment grand et

miséricordieux. C'est là ma grande consolation". (31-10-1938)

Le 9 novembre 1938, la haine des nazis envers les

juifs fut révélée au monde entier. Les synagogues brûlèrent. La terreur se

répandit parmi les juifs. La Mère Prieure des Carmélites de Cologne fait tout

son possible pour conduire soeur Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix à l'étranger.

Dans la nuit du 1er janvier 1938, elle traversa la frontière des Pays-Bas et

fut emmenée dans le monastère des Carmélites de Echt, en Hollande. C'est dans

ce lieu qu'elle écrivit son testament, le 9 juin 1939: "Déjà maintenant

j'accepte avec joie, en totale soumission et selon sa très sainte volonté, la

mort que Dieu m'a destinée. Je prie le Seigneur qu'Il accepte ma vie et ma mort

[...] en sorte que le Seigneur en vienne à être reconnu par les siens et que

son règne se manifeste dans toute sa grandeur pour le salut de l'Allemagne et

la paix dans le monde".

Déjà au monastère des Carmélites de Cologne on avait

permis à Édith Stein de se consacrer à ses oeuvres scientifiques. Entre autres

elle écrivit dans ce lieu "De la vie d'une famille juive". "Je

désire simplement raconter ce que j'ai vécu en tant que juive". Face à

"la jeunesse qui aujourd'hui est éduquée depuis l'âge le plus tendre à

haïr les juifs [...] nous, qui avons été éduqués dans la communauté juive, nous

avons le devoir de rendre témoignage".

En toute hâte, Édith Stein écrira à Echt son essai sur

"Jean de la Croix, le Docteur mystique de l'Église, à l'occasion du quatre

centième anniversaire de sa naissance, 1542-1942". En 1941, elle écrivit à

une religieuse avec laquelle elle avait des liens d'amitié: "Une scientia

crucis (la science de la croix) peut être apprise seulement si l'on ressent

tout le poids de la croix. De cela j'étais convaincue depuis le premier instant

et c'est de tout coeur que j'ai dit: Ave Crux, Spes unica (je te salue Croix,

notre unique espérance)". Son essai sur Jean de la Croix porta le

sous-titre: "La Science de la Croix".

Le 2 août 1942, la Gestapo arriva. Édith Stein se

trouvait dans la chapelle, avec les autres soeurs. En moins de 5 minutes elle

dut se présenter, avec sa soeur Rose qui avait été baptisée dans l'Église

catholique et qui travaillait chez les Carmélites de Echt. Les dernières

paroles d'Édith Stein que l'on entendit à Echt s'adressèrent à sa soeur:

"Viens, nous partons pour notre, peuple".

Avec de nombreux autres juifs convertis au

christianisme, les deux femmes furent conduites au camp de rassemblement de

Westerbork. Il s'agissait d'une vengeance contre le message de protestation des

évêques catholiques des Pays-Bas contre le progrom et les déportations de

juifs. "Que les êtres humains puissent en arriver à être ainsi, je ne l'ai

jamais compris et que mes soeurs et mes frères dussent tant souffrir, cela

aussi je ne l'ai jamais vraiment compris [...]; à chaque heure je prie pour eux.

Est-ce que Dieu entend ma prière? Avec certitude cependant il entend leurs

pleurs". Le professeur Jan Nota, qui lui était lié, écrira plus tard:

"Pour moi elle est, dans un monde de négation de Dieu, un témoin de la

présence de Dieu".

À l'aube du 7 août, un convoi de 987 juifs parti en

direction d'Auschwitz. Ce fut le 9 août 1942, que soeur Thérèse-Bénédicte de la

Croix, avec sa soeur Rose et de nombreux autres membres de son peuple, mourut

dans les chambres à gaz d'Auschwitz.

Avec sa béatification dans la Cathédrale de Cologne,

le ler mai 1987, l'Église honorait, comme l'a dit le Pape Jean-Paul II,

"une fille d'Israël, qui pendant les persécutions des nazis est demeurée

unie avec foi et amour au Seigneur Crucifié, Jésus Christ, telle une catholique,

et à son peuple telle une juive".

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_19981011_edith_stein_fr.html

Sainte Thérèse Bénédicte de La Croix

Carmélite - Martyre en Pologne (+ 1942)

Née le 12 octobre 1891 dans le judaïsme, Edith Stein était professeur d'université à Wroclaw (Breslau) et elle se tourna progressivement vers le Christ, malgré les difficultés nées de l'incompréhension de sa famille. Au temps de l'invasion nazie et de la persécution anti-juive, elle devint carmélite à Cologne traduisant dans sa vie les "sept demeures" de sainte Thérèse d'Avila et s'unissant, par la Croix, aux souffrances de son peuple. Réfugiée aux Pays-Bas, elle y fut arrêtée au carmel d'Echt, et elle meurt à Oświęcim (Auschwitz) huit jours plus tard, le 9 août 1942. Elle avait partagé la persécution de son peuple, portant le don de soi jusqu'au martyre pour le Christ.

canonisée à Rome le 11 octobre 1998.

- Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix Edith Stein (1891-1942) Carmélite déchaussée, martyre

- Edith Stein, femme de dialogue et d'espérance

- proclamée copatronne de l'Europe le 1e octobre 1999

- Edith Stein - Site du Carmel en France

- Sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix, nouvelle patronne de la Paroisse du Pays de Stenay - diocèse de Verdun.

Morte à Auschwitz parce qu'elle était juive. "Notre amour pour le prochain est la mesure de notre amour pour Dieu. Pour les chrétiens et pas seulement pour eux, personne n'est 'étranger'. L'amour du Christ ne connaît pas de frontière" (Edith Stein)

- Prier avec l'icône de Sainte Thérèse Bénédicte de la Croix (Edith Stein) vidéo

...Saint Benoît, proclamé patron de l'Europe par Paul VI en 1964, saint Cyrille et Méthode proclamés copatrons en 1980 par Jean-Paul II et trois saintes proclamées copatronnes de l'Europe en 1999 par Jean-Paul II: sainte Brigitte de Suède, sainte Catherine de Sienne et sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix (Edith Stein)...

Mémoire (En Europe : Fête) de sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix, carmélite

et martyre. Édith Stein, née et formée dans le judaïsme, après plusieurs années

où elle enseigna la philosophie au milieu de beaucoup de difficultés, reçut la

vie nouvelle dans le Christ par le baptême, et la poursuivit sous le voile des

moniales jusqu'à ce que le régime nazi la forçât à l'exil en Hollande. Pendant

la seconde guerre mondiale, elle fut arrêtée comme juive et conduite au camp

d'extermination d'Auschwitz, près de Cracovie, en Pologne, où elle mourut dans

une chambre à gaz.

Martyrologe romain

Je crois ... que plus on se sent attiré par Dieu et

plus on doit 'sortir de soi-même', dans le sens de se tourner vers le monde

pour lui porter une raison divine de vivre.

Edith Stein

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/7859/Sainte-Therese-Benedicte-de-La-Croix.html

Edith Stein, student at Breslau (1913-1914).

Edith Stein, estudiante en Breslavia (1913-1914).

Monasterio Santa Teresa de Jesús, Buenos Aires.

Self-scanned.

Sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix

D'origine juive, née en Allemagne le jour du Yom Kippour (Jour du grand Pardon) 1891, Edith Stein est élevée avec ses six frères et sœurs par leur mère veuve, énergique et juive convaincue. D'une intelligence très vive, Edith se passionne pour la philosophie, déclarant que la soif de vérité est sa seule prière. En même temps, elle milite pour la justice sociale et la promotion des valeurs de la féminité. Lorsque la guerre de 1914-1918 éclate, Edith est à l'université de Fribourg-en-Brisgau. Elle est l'assistante de Husserl, fondateur de la phénoménologie, qui devient son maître à penser. Elle commence à découvrir des aspects de la foi chrétienne : la prière, le "Notre Père" et des écrits de saint Thomas d'Aquin. Un jour, chez des amis, elle trouve "Le château intérieur ou le Livre des Demeures", autobiographie de sainte Thérèse d'Avila.

C'est l'illumination après un long cheminement intellectuel. Edith demande et reçoit le baptême chrétien. Loin de renier ses racines juives, elle les poussera à leur accomplissement. Elle enseigne chez les dominicaines de Spire et fréquente l'abbaye bénédictine de Beuron. Malgré la douleur de sa mère, Edith entre au Carmel de Cologne et devient soeur Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix. Sa soeur Rose la rejoint comme membre du Tiers-Ordre du Carmel.

Edith a offert sa vie à Dieu pour la rédemption du peuple d'Israël, alors que se déclenche la persécution des Nazis. Avec sa soeur, elle doit se réfugier au carmel d'Echt en Hollande. Elles y seront arrêtées, emmenées à Auschwitz et exécutées le 9 août 1943. Prophète du sacrifice de soi, de la tolérance et du respect des valeurs de l'esprit, sainte Edith Stein a été proclamée patronne de l'Europe par Jean-Paul II le 1er octobre 1999, dans la suite de Catherine de Sienne et avec Brigitte de Suède.

Edith est un nom d'origine germanique qui a le sens de "richesse" (od).

Rédacteur : Frère Bernard Pineau, OP

SOURCE : http://www.lejourduseigneur.com/Web-TV/Saints/Edith-Stein/(language)/fre-FR

1. L'espoir de construire un monde plus juste et plus

digne de l'homme, aiguisé par l'attente du troisième millénaire désormais à nos

portes, ne peut faire abstraction de la conscience que les efforts humains

seraient vains s'ils n'étaient accompagnés par la grâce divine: « Si le

Seigneur ne bâtit la maison, les bâtisseurs travaillent en vain » (Ps 127

[126], 1). C'est une vérité dont doivent tenir compte également ceux qui,

aujourd'hui, se posent la question de donner à l'Europe de nouvelles bases qui

aident le vieux continent à puiser dans les richesses de son histoire, écartant

les tristes aspects de l'héritage du passé pour répondre, avec une originalité

enracinée dans les meilleures traditions, aux besoins du monde qui change.

Il n'y a pas de doute que, dans l'histoire complexe de

l'Europe, le christianisme représente un élément central et caractéristique,

renforcé par le solide fondement de l'héritage classique et des contributions

multiples apportées par divers mouvements ethniques et culturels qui se sont

succédé au cours des siècles. La foi chrétienne a façonné la culture du

continent et a été mêlée de façon inextricable à son histoire, au point que

celle-ci serait incompréhensible sans référence aux événements qui ont

caractérisé d'abord la grande période de l'évangélisation, puis les longs

siècles au cours desquels le christianisme, malgré la douloureuse division

entre l'Orient et l'Occident, s'est affirmé comme la religion des Européens

eux-mêmes. Dans la période moderne et contemporaine aussi, lorsque l'unité

religieuse s'est progressivement fractionnée tant à cause de nouvelles

divisions intervenues entre les chrétiens qu'en raison des processus qui ont

amené la culture à se détacher des perspectives de la foi, le rôle de cette

dernière a gardé un relief non négligeable.

La route vers l'avenir ne peut pas ne pas tenir compte

de ce fait; les chrétiens sont appelés à en prendre une conscience renouvelée

afin d'en montrer les potentialités permanentes. Ils ont le devoir d'apporter à

la construction de l'Europe une contribution spécifique, qui aura d'autant plus

de valeur et d'efficacité qu'ils sauront se renouveler à la lumière de

l'Évangile. Il se feront alors les continuateurs de cette longue histoire de

sainteté qui a traversé les diverses régions de l'Europe au cours de ces deux

millénaires, où les saints officiellement reconnus ne sont que les sommets

proposés comme modèles pour tous. Il y a en effet d'innombrables chrétiens qui,

par leur vie droite et honnête, animée par l'amour de Dieu et du prochain, ont

atteint, dans les vocations consacrées et laïques les plus diverses, une

sainteté véritable et largement diffusée, même si elle était cachée.

2. L'Église ne doute pas que ce trésor de sainteté

soit précisément le secret de son passé et l'espérance de son avenir. C'est en

lui que s'exprime le mieux le don de la Rédemption, grâce auquel l'homme est

racheté du péché et reçoit la possibilité de la vie nouvelle dans le Christ.

C'est en lui que le peuple de Dieu en marche dans l'histoire trouve un soutien

incomparable, se sentant profondément uni à l'Église glorieuse, qui au ciel

chante les louanges de l'Agneau (cf. Ap 7, 9-10) tandis qu'elle

intercède pour la communauté encore en pèlerinage sur la terre. C'est pourquoi,

depuis les temps les plus anciens, les saints ont été considérés par le peuple

de Dieu comme des protecteurs et, par suite d'une habitude particulière, à

laquelle l'influence de l'Esprit Saint n'est certainement pas étrangère, tantôt

à la demande des fidèles acceptée par les Pasteurs, tantôt sur l'initiative des

Pasteurs eux-mêmes, les Églises particulières, les régions et même les

continents ont été confiés au patronage spécial de certains saints.

Dans cette perspective, alors qu'est célébrée la

deuxième Assemblée spéciale pour l'Europe du Synode des Évêques, dans

l'imminence du grand Jubilé de l'An 2000, il m'a semblé que les chrétiens

européens, tout en vivant avec tous leurs compatriotes un passage d'une époque

à l'autre qui est à la fois riche d'espoir et non dénué de préoccupations, peuvent

tirer un profit spirituel de la contemplation et de l'invocation de certains

saints qui sont de quelque manière particulièrement représentatifs de leur

histoire. Aussi, après une consultation opportune, complétant ce que j'ai fait

le 31 décembre 1980 quand j'ai déclaré co-patrons de l'Europe, aux côtés de

saint Benoît, deux saints du premier millénaire, les frères Cyrille et Méthode,

pionniers de l'évangélisation de l'Orient, j'ai pensé compléter le cortège des

patrons célestes par trois figures également emblématiques de moments cruciaux

du deuxième millénaire qui touche à sa fin: sainte Brigitte de Suède, sainte

Catherine de Sienne, sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix. Trois grandes

saintes, trois femmes qui, à des époques différentes — deux au cœur du Moyen

Âge et une en notre siècle — se sont signalées par l'amour actif de l'Église du

Christ et le témoignage rendu à sa Croix.

3. Naturellement, le panorama de la sainteté est si

varié et si riche que le choix de nouveaux patrons célestes aurait pu s'orienter

aussi vers d'autres figures très dignes dont chaque époque et chaque région

peuvent se glorifier. Je crois toutefois particulièrement significatif le choix

de cette sainteté au visage féminin, dans le cadre de la tendance

providentielle qui s'est affermie dans l'Église et dans la société de notre

temps, reconnaissant toujours plus clairement la dignité de la femme et ses

dons propres.

En réalité, l'Église n'a pas manqué, depuis ses

origines, de reconnaître le rôle et la mission de la femme, bien qu'elle ait

été conditionnée parfois par une culture qui ne prêtait pas toujours à la femme

l'attention qui lui était due. Mais la communauté chrétienne a progressé peu à

peu dans ce sens, et précisément le rôle joué par la sainteté s'est révélé

décisif sur ce plan. Une incitation constante a été offerte par l'image de

Marie, « femme idéale », Mère du Christ et de l'Église. Mais également le

courage des martyres, qui ont affronté les tourments les plus cruels avec une

surprenante force d'âme, le témoignage des femmes engagées de manière

exemplaire et radicale dans la vie ascétique, le dévouement quotidien de

nombreuses épouses et mères dans l'« Église au foyer » qu'est la famille, les

charismes de tant de mystiques qui ont contribué à l'approfondissement théologique

lui-même, tout cela a fourni à l'Église des indications précieuses pour

comprendre pleinement le dessein de Dieu sur la femme. D'ailleurs, ce dessein a

déjà dans certaines pages de l'Écriture, en particulier dans l'attitude du

Christ dont témoigne l'Évangile, son expression sans équivoque. C'est dans

cette ligne que prend place le choix de déclarer sainte Brigitte de Suède,

sainte Catherine de Sienne et sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix co-patronnes

de l'Europe.

Le motif qui m'a fait me tourner spécifiquement vers

elles repose dans leurs vies elles-mêmes. Leur sainteté s'est en effet exprimée

dans des circonstances historiques et dans un contexte « géographique » qui les

rendent particulièrement significatives pour le continent européen. Sainte Brigitte

renvoie à l'extrême nord de l'Europe, où le continent se regroupe dans une

quasi-unité avec le reste du monde et d'où elle partit pour aborder à Rome.

Catherine de Sienne est aussi connue pour le rôle qu'elle joua en un temps où

le Successeur de Pierre résidait à Avignon, et elle acheva une œuvre

spirituelle déjà commencée par Brigitte en se faisant la promotrice de son

retour à son siège propre près du tombeau du Prince des Apôtres. Enfin

Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix, récemment canonisée, non seulement passa sa vie

dans divers pays d'Europe, mais par toute sa vie d'intellectuelle, de mystique,

de martyre, jeta comme un pont entre ses racines juives et l'adhésion au

Christ, s'adonnant avec un intuition sûre au dialogue avec la pensée

philosophique contemporaine et, en fin de compte, faisant résonner par son

martyre les raisons de Dieu et de l'homme face à la honte épouvantable de la «

shoah ». Elle est devenue ainsi l'expression d'un pèlerinage humain, culturel

et religieux qui incarne le noyau insondable de la tragédie et des espoirs du

continent européen.

4. La première de ces trois grandes figures, Brigitte,

est née 1303, d'une famille aristocratique, à Finsta, dans la région suédoise

d'Uppland. Elle est connue surtout comme mystique et fondatrice de l'Ordre du

Très Saint Sauveur. Toutefois, il ne faut pas oublier que la première partie de

sa vie fut celle d'une laïque qui eut le bonheur d'être mariée avec un pieux

chrétien dont elle eut huit enfants. En la désignant comme co-patronne de

l'Europe, j'entends faire en sorte que la sentent proche d'eux non seulement

ceux qui ont reçu la vocation à une vie de consécration spéciale, mais aussi

ceux qui sont appelés aux occupations ordinaires de la vie laïque dans le monde

et surtout à la haute et exigeante vocation de former une famille chrétienne.

Sans se laisser fourvoyer par les conditions de bien-être de son milieu, elle

vécut avec son époux Ulf une expérience de couple dans laquelle l'amour

conjugal alla de pair avec une prière intense, avec l'étude de l'Écriture

Sainte, avec la mortification, avec la charité. Ils fondèrent ensemble un petit

hôpital, où ils soignaient fréquemment les malades. Brigitte avait l'habitude

de servir personnellement les pauvres. En même temps, elle fut appréciée pour

ses qualités pédagogiques, qu'elle eut l'occasion de mettre en œuvre durant la

période où l'on demanda ses services à la cour de Stockholm. C'est dans cette

expérience que mûriront les conseils qu'elle donnera en diverses occasions à

des princes ou à des souverains pour un bon accomplissement de leurs tâches.

Mais les premiers qui en bénéficièrent furent assurément ses enfants, et ce

n'est pas par hasard que l'une de ses filles, Catherine, est vénérée comme

sainte.

Cette période de sa vie familiale n'était qu'une première

étape. Le pèlerinage qu'elle fit avec son mari Ulf à Saint-Jacques de

Compostelle en 1341 mit symboliquement fin à cette étape, préparant Brigitte à

la nouvelle vie qu'elle inaugura quelques années plus tard lorsque, après la

mort de son époux, elle entendit la voix du Christ qui lui confiait une

nouvelle mission, la guidant pas à pas par une série de grâces mystiques

extraordinaires.

5. Ayant quitté la Suède en 1349, Brigitte s'établit à

Rome, siège du Successeur de Pierre. Son transfert en Italie constitua une

étape décisive pour l'élargissement non seulement géographique et culturel,

mais surtout spirituel, de l'esprit et du cœur de Brigitte. Beaucoup de lieux

d'Italie la virent encore en pèlerinage, désireuse de vénérer les reliques des

saints. Elle visita ainsi Milan, Pavie, Assise, Ortona, Bari, Benevento,

Pozzuoli, Naples, Salerne, Amalfi, le Sanctuaire de saint Michel Archange sur

le Mont Gargano. Le dernier pèlerinage, effectué entre 1371 et 1372, l'amena à

traverser la Méditerranée en direction de la Terre Sainte, lui permettant

d'embrasser spirituellement, en plus de beaucoup de lieux sacrés de l'Europe

catholique, les sources mêmes du christianisme dans les lieux sanctifiés par la

vie et par la mort du Rédempteur.

En réalité, plus encore que par ce pieux pèlerinage,

c'est par le sens profond du mystère du Christ et de l'Église que Brigitte

participa à la construction de la communauté ecclésiale, à une période

notablement critique de son histoire. Son union intime au Christ s'accompagna

en effet de charismes particuliers de révélation qui firent d'elle un point de

référence pour beaucoup de personnes de l'Église de son époque. On sent en

Brigitte la force de la prophétie. Son ton semble parfois un écho de celui des

anciens grands prophètes. Elle parle avec sûreté à des princes et à des papes,

révélant les desseins de Dieu sur les événements de l'histoire. Elle n'épargne

pas les avertissements sévères même en matière de réforme morale du peuple

chrétien et du clergé lui-même (cf. Revelationes, IV, 49; cf. aussi IV,

5). Certains aspects de son extraordinaire production mystique suscitèrent en

son temps des interrogations bien compréhensibles, à l'égard desquelles s'opéra

le discernement de l'Église; celle-ci renvoya à l'unique révélation publique, qui

a sa plénitude dans le Christ et son expression normative dans l'Écriture

Sainte. Même les expériences des grands saints, en effet, ne sont pas exemptes

des limites qui accompagnent toujours la réception par l'homme de la voix de

Dieu.

Toutefois, il n'est pas douteux qu'en reconnaissant la

sainteté de Brigitte, l'Église, sans pour autant se prononcer sur les diverses

révélations, a accueilli l'authenticité globale de son expérience intérieure.

Brigitte se présente comme un témoin significatif de la place que peut tenir

dans l'Église le charisme vécu en pleine docilité à l'Esprit de Dieu et en

totale conformité aux exigences de la communion ecclésiale. En particulier, les

terres scandinaves, patrie de Brigitte, s'étant détachées de la pleine

communion avec le siège de Rome au cours de tristes événements du XVIe siècle,

la figure de la sainte suédoise reste un précieux « lien » œcuménique, renforcé

encore par l'engagement de son Ordre dans ce sens.

6. L'autre grande figure de femme, sainte Catherine de

Sienne, est à peine postérieure. Son rôle dans les développements de l'histoire

de l'Église et même dans l'approfondissement doctrinal du message révélé a été

reconnu d'une manière significative, jusqu'à l'attribution du titre de Docteur

de l'Église.

Née à Sienne en 1347, elle fut favorisée dès sa plus

tendre enfance de grâces extraordinaires qui lui permirent d'accomplir, sur la

voie spirituelle tracée par saint Dominique, un parcours rapide de perfection

entre prière, austérité et œuvres de charité. Elle avait vingt ans quand le

Christ lui manifesta sa prédilection à travers le symbole mystique de l'anneau

nuptial. C'était le couronnement d'une intimité mûrie dans le secret et dans la

contemplation, grâce à la constante permanence, bien que ce soit hors des murs

d'un monastère, dans la demeure spirituelle qu'elle aimait appeler la « cellule

intérieure ». Le silence de cette cellule, qui la rendait très docile aux

divines inspirations, put bien vite s'allier à une activité apostolique qui a

quelque chose d'extraordinaire. Beaucoup de personnes, même des clercs, se

regroupèrent autour d'elle comme disciples, lui reconnaissant le don d'une

maternité spirituelle. Ses lettres se répandirent à travers l'Italie et

l'Europe elle-même. En effet, la jeune siennoise entra avec un regard sûr et

des paroles de feu dans le vif des problèmes ecclésiaux et sociaux de son

époque.

Catherine s'engagea inlassablement pour la résolution

des multiples conflits qui déchiraient la société de son temps. Son action

pacificatrice atteignit des souverains européens comme Charles V de France,

Charles de Durazzo, Élisabeth de Hongrie, Louis le Grand de Hongrie et de

Pologne, Jeanne de Naples. Son intervention pour la réconciliation de Florence

avec le Pape fut significative. Désignant « le Christ crucifié et la douce

Marie » aux adversaires, elle montrait que, pour une société qui s'inspirait

des valeurs chrétiennes, il ne pouvait jamais y avoir de motif de querelle

tellement grave que l'on puisse préférer le recours à la raison des armes plutôt

qu'aux armes de la raison.

7. Mais Catherine savait bien que l'on ne pouvait

aboutir efficacement à cette conclusion si les esprits n'avaient pas été formés

auparavant par la vigueur même de l'Évangile. D'où l'urgence de la réforme des

mœurs, qu'elle proposait à tous sans exception. Aux rois, elle rappelait qu'ils

ne pouvaient gouverner comme si le royaume était leur « propriété »: bien

conscients qu'ils auraient à rendre compte à Dieu de la gestion du pouvoir, ils

devaient plutôt assumer la tâche d'y maintenir « la sainte et véritable justice

», se faisant « pères des pauvres » (cf. Lettre n. 235 au Roi de France).

L'exercice de la souveraineté ne pouvait en effet être séparé de celui de la

charité, qui est l'âme à la fois de la vie personnelle et de la responsabilité

politique (cf. Lettre n. 357 au Roi de Hongrie).

C'est avec la même force que Catherine s'adressait aux

ecclésiastiques de tout rang, pour leur demander la cohérence la plus stricte

dans leur vie et dans leur ministère pastoral. Le ton libre, vigoureux,

tranchant, avec lequel elle admoneste prêtres, évêques et cardinaux est

impressionnant. Il fallait — disait-elle — déraciner dans le jardin de l'Église

les plantes pourries et les remplacer par des « plantes nouvelles » fraîches et

odorantes. Forte de son intimité avec le Christ, la sainte siennoise ne

craignait pas d'indiquer avec franchise au Souverain Pontife lui-même, qu'elle

aimait tendrement comme le « doux Christ sur la terre », la volonté de Dieu qui

lui imposait d'en finir avec les hésitations dictées par la prudence terrestre

et par les intérêts mondains, pour rentrer d'Avignon à Rome, près du tombeau de

Pierre.

Avec la même passion, Catherine s'employa à remédier

aux divisions qui surgirent lors de l'élection du Pape qui suivit la mort de

Grégoire XI: dans cette affaire aussi, elle fit appel une fois de plus, avec

une ardeur passionnée, aux raisons indiscutables de la communion. C'était là

l'idéal suprême qui avait inspiré toute sa vie, dépensée sans réserve au

service de l'Église. C'est elle-même qui en témoignera devant ses fils

spirituels sur son lit de mort: « Tenez pour certain, mes très chers, que j'ai

donné ma vie pour la sainte Église » (Bienheureux Raymond de Capoue, Vie

de sainte Catherine de Sienne, Livre III, chap. IV).

8. Avec Edith Stein — sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la

Croix —, nous sommes dans un tout autre monde historique et culturel. Elle nous

entraîne en effet au cœur de notre siècle tourmenté, indiquant les espérances

qui l'ont éclairé, mais aussi les contradictions et les échecs qui l'ont marqué.

Elle ne vient pas, comme Brigitte et Catherine, d'une famille chrétienne. En

elle, tout exprime le tourment de la recherche et l'effort du « pèlerinage »

existentiel. Même après être parvenue à la vérité dans la paix de la vie

contemplative, elle dût vivre jusqu'au bout le mystère de la Croix.

Elle était née en 1891 dans une famille juive de

Breslau, alors territoire allemand. L'intérêt qu'elle développa pour la

philosophie, abandonnant la pratique religieuse à laquelle sa mère l'avait

pourtant initiée, aurait fait prédire, plus qu'un chemin de sainteté, une vie

menée à l'enseigne du pur « rationalisme ». Mais la grâce l'attendait

précisément dans les méandres de la pensée philosophique: engagée sur la voie

du courant phénoménologique, elle sut saisir l'exigence d'une réalité objective

qui, loin de trouver sa solution dans le sujet, devance et mesure sa

connaissance, réalité qui doit donc être examinée dans un effort rigoureux

d'objectivité. Il convient de se mettre à son écoute pour la saisir surtout dans

l'être humain, en vertu de la capacité d'« empathie » — mot qui lui est cher —

qui consent dans une certaine mesure à faire sien le vécu d'autrui (cf. E.

Stein, Le problème de l'empathie).

C'est dans cette tension d'écoute qu'elle rencontra,

d'une part, le témoignage de l'expérience spirituelle chrétienne offert par

sainte Thérèse d'Avila et par d'autres grands mystiques, dont elle devint

disciple et émule, d'autre part, l'ancienne tradition chrétienne structurée

dans le thomisme. Sur cette voie, elle parvint d'abord au baptême, puis choisit

la vie contemplative dans l'ordre du Carmel. Tout se déroule dans le cadre d'un

itinéraire existentiel plutôt mouvementé, scandé, non seulement par la

recherche intérieure, mais aussi par des engagements d'étude et d'enseignement,

qu'elle conduit avec un admirable don d'elle-même. Son militantisme en faveur

de la promotion sociale de la femme fut particulièrement appréciable pour son

temps, et les pages dans lesquelles elle explora la richesse de la féminité et

la mission de la femme du point de vue humain et religieux sont vraiment

pénétrantes (cf. E. Stein, La femme. Sa mission selon la nature et la

grâce).

9. Sa rencontre avec le christianisme ne la conduit

pas à renier ses racines juives, mais les lui fait plutôt redécouvrir en

plénitude. Cependant, cela ne lui épargne pas l'incompréhension de la part de

ses proches. Le désaccord de sa mère, surtout, lui procura une douleur

indicible. En réalité, tout son chemin de perfection chrétienne se déroule sous

le signe non seulement de la solidarité humaine avec son peuple d'origine, mais

aussi d'un vrai partage spirituel avec la vocation des fils d'Abraham, marqués

par le mystère de l'appel et des « dons irrévocables » de Dieu (cf. Rm 11,

29).

En particulier, elle fit sienne la souffrance du

peuple juif, à mesure que celle-ci s'exacerbait au cours de la féroce

persécution nazie, qui demeure, à côté d'autres graves expressions du

totalitarisme, l'une des taches les plus sombres et les plus honteuses de

l'Europe de notre siècle. Elle ressentit alors, dans l'extermination

systématique des juifs, que la Croix du Christ était mise sur le dos de son

peuple, et elle vécut comme une participation personnelle à la Croix sa

déportation et son exécution dans le tristement célèbre camp d'AuschwitzBirkenau.

Son cri se mêla à celui de toutes les victimes de cette épouvantable tragédie,

s'unissant en même temps au cri du Christ, qui assure à la souffrance humaine

une fécondité mystérieuse et durable. Son image de sainteté reste pour toujours

liée au drame de sa mort violente, aux côtés de tous ceux qui la subirent avec

elle. Et elle reste comme une annonce de l'Évangile de la Croix à laquelle elle

voulut s'identifier par son nom de religieuse.

Nous nous tournons aujourd'hui vers Thérèse-Bénédicte

de la Croix, reconnaissant dans son témoignage de victime innocente, d'une

part, l'imitation de l'Agneau immolé et la protestation élevée contre toutes

les violations des droits fondamentaux de la personne; d'autre part, le gage de

la rencontre renouvelée entre juifs et chrétiens qui, dans la ligne voulue par

le Concile Vatican II, connaît un temps prometteur d'ouverture réciproque.

Déclarer aujourd'hui Edith Stein copatronne de l'Europe signifie déployer sur

l'horizon du vieux continent un étendard de respect, de tolérance, d'accueil,

qui invite hommes et femmes à se comprendre et à s'accepter au-delà des

diversités de race, de culture et de religion, afin de former une société

vraiment fraternelle.

10. Puisse donc l'Europe croître! Puisse-t-elle

croître comme Europe de l'esprit, dans la ligne du meilleur de son histoire,

qui trouve précisément dans la sainteté son expression la plus haute. L'unité

du continent, qui mûrit progressivement dans les consciences et se définit

aussi toujours plus nettement sous l'angle politique, incarne assurément une

perspective de grande espérance. Les Européens sont appelés à laisser

définitivement de côté les rivalités historiques qui ont souvent fait de leur

continent le théâtre de guerres dévastatrices. En même temps, ils doivent

s'engager à créer les conditions d'une plus grande cohésion et d'une plus

grande collaboration entre les peuples. Ils sont face au grand défi de la

construction d'une culture et d'une éthique de l'unité, sans lesquelles

n'importe quelle politique de l'unité est destinée tôt ou tard à s'effondrer.

Pour édifier la nouvelle Europe sur des bases solides,

il ne suffit certes pas de lancer un appel aux seuls intérêts économiques qui,

s'ils rassemblent parfois, d'autres fois divisent, mais il est nécessaire de

s'appuyer plutôt sur les valeurs authentiques, qui ont leur fondement dans la

loi morale universelle, inscrite dans le cœur de tout homme. Une Europe qui

remplacerait les valeurs de tolérance et de respect universel par

l'indifférentisme éthique et le scepticisme en matière de valeurs inaliénables,

s'ouvrirait aux aventures les plus risquées et verrait tôt ou tard réapparaître

sous de nouvelles formes les spectres les plus effroyables de son histoire.

Pour conjurer cette menace, le rôle du christianisme,

qui désigne inlassablement l'horizon idéal, s'avère encore une fois vital. À la

lumière des nombreux points de rencontre avec les autres religions que le

Concile Vatican II a reconnus (cf. décret Nostra

ætate), on doit souligner avec force que l'ouverture au Transcendant est

une dimension vitale de l'existence. Il est donc essentiel que tous les

chrétiens présents dans les différents pays du continent s'engagent à un

témoignage renouvelé. Il leur appartient de nourrir l'espérance de la plénitude

du salut par l'annonce qui leur est propre, celle de l'Évangile, à savoir la «

bonne nouvelle » que Dieu s'est fait proche de nous et que, en son Fils Jésus

Christ, il nous a offert la rédemption et la plénitude de la vie divine. Par la

force de l'Esprit Saint qui nous a été donné, nous pouvons lever les yeux vers

Dieu et l'invoquer avec le doux nom d'« Abba », Père (cf. Rm 8,

15; Ga 4, 6).

11. C'est justement cette annonce d'espérance que j'ai

voulu confirmer, en proposant à une dévotion renouvelée, dans une perspective «

européenne », ces trois figures de femmes qui, à des époques diverses, ont

apporté une contribution très significative à la croissance non seulement de

l'Église, mais de la société elle-même.

Par la communion des saints qui unit mystérieusement

l'Église terrestre à celle du ciel, elles nous prennent en charge dans leur

intercession permanente devant le trône de Dieu. En même temps, en les

invoquant de manière plus intense et en nous référant plus assidûment et plus

attentivement à leurs paroles et à leurs exemples, nous ne pouvons pas ne pas

réveiller en nous une conscience plus aiguë de notre vocation commune à la sainteté,

qui nous pousse à prendre la résolution d'un engagement plus généreux.

Ainsi donc, après mûre considération, en vertu de mon

pouvoir apostolique, je constitue et je déclare co-patronnes célestes de toute

l'Europe auprès de Dieu sainte Brigitte de Suède, sainte Catherine de Sienne,

sainte Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix, leur accordant tous les honneurs et

privilèges liturgiques qui appartiennent selon le droit aux patrons principaux

des lieux.

Gloire à la sainte Trinité, qui resplendit de façon

singulière dans leur vie et dans la vie de tous le saints! Paix aux homme de

bonne volonté, en Europe et dans le monde entier!

Rome, près de Saint-Pierre, le 1er octobre 1999, en la

vingt et unième année de mon Pontificat.

JEAN-PAUL II

© Copyright 1999 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Büste, Edith

Stein, Kirchstraße 13, Berlin-Moabit, Deutschland

Bust, Edith

Stein, Kirchstraße 13, Berlin-Moabit, Germany

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 13 août 2008

· Celui

qui prie ne perd jamais l'espérance,

les témoignages d'Edith Stein et de Maximilien Marie Kolbe

· Chers

frères et sœurs!

· De

retour de Bressanone, où j'ai pu passer une période de repos, je suis content

de vous rencontrer et de vous saluer, chers habitants de Castel Gandolfo, et

vous pèlerins qui êtes venus aujourd'hui me rendre visite. Je voudrais encore

une fois remercier ceux qui m'ont accueilli et ont veillé sur mon séjour en

montagne. Ce furent des jours de détente sereine, au cours desquels je n'ai

cessé de rappeler au Seigneur tous ceux qui s'en remettent à mes prières. Et

ils sont vraiment très nombreux tous ceux qui m'écrivent en me demandant de

prier pour eux. Ils m'expriment leurs joies, mais aussi leurs inquiétudes, leurs

projets de vie, ainsi que les problèmes familiaux et professionnels, les

attentes et les espoirs qu'ils portent dans leur cœur, avec les angoisses liées

aux incertitudes que l'humanité vit en ce moment. Je peux assurer que je me

souviens de tous et de chacun, en particulier lors de la célébration

quotidienne de la Messe et de la récitation du Rosaire. Je sais bien que le

premier service que je peux rendre à l'Eglise et à l'humanité est précisément

celui de la prière, parce qu'en priant je place entre les mains du Seigneur

avec confiance le ministère qu'il m'a lui-même confié, avec le destin de toute

la communauté ecclésiale et civile.

· Celui

qui prie ne perd jamais l'espérance, même lorsqu'il en vient à se trouver dans

des situations difficiles voire humainement désespérées. C'est ce que nous

enseigne la Sainte Ecriture et ce dont témoigne l'histoire de l'Eglise. Combien

d'exemples, en effet, pourrions nous apporter de situations où ce fut

véritablement la prière qui soutint le chemin des saints et du peuple chrétien!

Parmi les témoignages de notre époque je voudrais citer celui de deux saints

dont nous célébrons ces jours-ci la mémoire: Thérèse Bénédicte de la

Croix, Edith Stein, dont nous avons célébré la fête le 9 août, et Maximilien

Marie Kolbe, que nous célébrerons demain, 14 août, veille de la solennité de

l'Assomption de la Bienheureuse Vierge Marie. Tous deux ont conclu leur vie

terrestre par le martyre dans le camp d'Auschwitz. Apparemment leurs existences

pourraient être considérées comme un échec, mais c'est précisément dans leur

martyre que resplendit l'éclair de l'Amour, qui vainc les ténèbres de l'égoïsme

et de la haine. A saint Maximilien Kolbe sont attribuées les paroles suivantes

qu'il aurait prononcées en pleine fureur de la persécution nazie:

"La haine n'est pas une force créatrice: seul l'amour en est

une". Et il apporta une preuve héroïque de l'amour en s'offrant

généreusement en échange de l'un de ses compagnons de prison, une offrande qui

culmina par sa mort dans le bunker de la faim, le 14 août 1941.

· Edith

Stein, le 6 août de l'année suivante, à trois jours de sa fin dramatique,

approchant des consœurs du monastère de Echt, en Hollande, leur dit:

"Je suis prête à tout. Jésus est ici aussi au milieu de nous, jusqu'à

présent j'ai pu très bien prier et j'ai dit de tout mon cœur: "Ave,

Crux, spes unica"". Des témoins qui parvinrent à échapper à

l'horrible massacre racontèrent que Thérèse Bénédicte de la Croix, tandis

qu'elle revêtait l'habit carmélitain, avançait consciemment vers sa mort, elle

se distinguait par son comportement empli de paix, par son attitude sereine et

par des manières calmes et attentives aux nécessités de tous. La prière fut le

secret de cette sainte copatronne de l'Europe, qui "même après être parvenue

à la vérité dans la paix de la vie contemplative, dut vivre jusqu'au bout le

mystère de la Croix" (Lettre apostolique Spes aedificandi, Enseignements

de Jean-Paul II, XX, 2, 1999, p. 511).

· "Ave

Maria!": ce fut la dernière invocation sur les lèvres de saint

Maximilien Marie Kolbe tandis qu'il tendait le bras à celui qui le tuait par

une injection d'acide phénique. Il est émouvant de constater comment le recours

humble et confiant à la Vierge est toujours une source de courage et de sérénité.

Alors que nous nous préparons à célébrer la solennité de l'Assomption, qui est

l'une des célébrations mariales les plus chères à la tradition chrétienne, nous

renouvelons notre consécration à Celle qui depuis le Ciel veille à tout instant

sur nous avec un amour maternel. Tel est en effet ce que nous disons dans la

prière familière du "Je vous salue Marie", en lui demandant de prier

pour nous "aujourd'hui et à l'heure de notre mort".

****

· Je

salue cordialement les pèlerins de langue française, en particulier le groupe

des jeunes collégiens de Draguignan, ainsi que les Petites Sœurs de Jésus qui

se préparent à émettre leurs vœux perpétuels dans l’esprit du Bienheureux

Charles de Foucauld. Que votre pèlerinage auprès du tombeau des Apôtres Pierre

et Paul soit pour vous l’occasion de raffermir votre attachement au Christ et à

son Église et de renforcer votre esprit missionnaire. Que Dieu vous bénisse !

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria

Editrice Vaticana

Le monde est en feu

Aujourd’hui le Seigneur

nous regarde, grave, mettant à l’épreuve, et il demande à chacune de

nous : Veux-tu garder la fidélité au Crucifié ? Réfléchis bien !

Le monde est en feu, le combat entre le Christ et l’Antéchrist bat son plein

ouvertement. Si tu te décides pour le Christ, il peut t’en coûter la vie.

Réfléchis bien aussi à ce que tu promets.

Le monde est en feu. Le

brasier peut aussi atteindre notre maison. Mais élevée au-dessus de toutes les

flammes, la croix s’élance. Elles ne peuvent pas l’embraser. Elle est le chemin

de la terre vers le ciel. Celui qui l’embrasse en croyant, aimant, espérant,

elle le porte jusque dans le sein de la Trinité.

Le monde est en feu.

Est-ce qu’il ne te presse pas de l’éteindre ? Regarde en haut vers la

croix. Du cœur ouvert coule le sang du Rédempteur. Il éteint les flammes de

l’enfer. Rends ton cœur libre par l’accomplissement fidèle de tes vœux, ensuite

se déversera dans ton cœur le flot de l’amour divin, jusqu’à ce qu’il déborde

et devienne fécond jusqu’aux limites de la terre.

Ste Édith Stein

Édith Stein, philosophe

allemande issue d’une famille juive, se convertit au catholicisme en 1922 et

entre au Carmel en 1933, prenant le nom de Thérèse-Bénédicte de la Croix.

Solidaire de ses frères, elle meurt au camp d’Auschwitz en 1942. / Source cachée,

Paris, Ad Solem-Cerf, 1999, p. 238

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/vendredi-15-avril/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Edith Stein Denkmal in Köln Bildhauer Bernd Gerresheim

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

Also known as

Edith Stein

Teresia Benedicta

Profile

Youngest of seven children in

a Jewish family. Edith lost interest and faith in Judaism by age 13.

Brilliant student and philosopher with

an interest in phenomenology. Studied at

the University of

Göttingen, Germany and

in Breisgau, Germany.

Earned her doctorate in philosophy in 1916 at

age 25. Witnessing the strength of faith of Catholic friends

led her to an interest in Catholicism,

which led to studying a catechism on

her own, which led to “reading herself into” the Faith. Converted to Catholicism in Cologne, Germany; baptized in

Saint Martin’s church, Bad Bergzabern, Germany on 1

January 1922.

Carmelite nun in 1934,

taking the name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. Teacher in

the Dominican school in Speyer, Germany and lecturer at

the Educational Institute in Munich, Germany.

However, anti-Jewish pressure

from the Nazis forced her to resign both positions. Profound spiritual writer.

Both Jewish and Catholic, she was smuggled out

of Germany,

and assigned to Echt, Netherlands in 1938.

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands,

she and her sister Rose, also a convert to Catholicism,

were captured and

sent to the concentration camp at Auschwitz where they died in

the gas chambers like so many others.

Born

12

October 1891 at

Breslaw, Dolnoslaskie, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland)

as Edith Stein

body cremated

gassed on 9

August 1942 in

the ovens of Oswiecim (a.k.a. Auschwitz), Malopolskie (Poland)

26

January 1987 by Pope John

Paul II

1

May 1987 by Pope John

Paul II in the cathedral at Cologne, Germany

11

October 1998 by Pope John

Paul II

Star of David

Storefront

Additional Information

Pope Benedict XVI: General Audience, 13

August 2008

books

John Paul II’s Book of Saints, by Matthew Bunson and

Margaret Bunson

other sites in english

Catholic Herald: How Saint Teresa Benedicta reconciled with

her devout Jewish mother

Pope John Paul II: Canonization Homily

images

audio

Curious Catholic: Essays on Women, with Sister Judith

Parsons

Curious Catholic: On the Problem of Empathy, with Donald

Wallenfang

Curious Catholic: Knowledge and Faith, with Richard Bernier

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

fonti in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Readings

Whatever did not fit in with my plan did lie within

the plan of God. I have an ever deeper and firmer belief that nothing is merely

an accident when seen in the light of God, that my whole life down to the

smallest details has been marked out for me in the plan of Divine Providence

and has a completely coherent meaning in God’s all-seeing eyes. And so I am

beginning to rejoice in the light of glory wherein this meaning will be

unveiled to me. Saint Teresa

Benedicta of the Cross

God is there in these moments of rest and can give us

in a single instant exactly what we need. Then the rest of the day can take its

course, under the same effort and strain, perhaps, but in peace. And when night

comes, and you look back over the day and see how fragmentary everything has

been, and how much you planned that has gone undone, and all the reasons you have

to be embarrassed and ashamed: just take everything exactly as it is, put it in

God’s hands and leave it with Him. Then you will be able to rest in Him —

really rest — and start the next day as a new life. Saint Teresa

Benedicta of the Cross

Learn from Saint Thérèse to

depend on God alone and serve Him with a wholly pure and detached heart. Then,

like her, you will be able to say ‘I do not regret that I have given myself up

to Love’. Saint Teresa

Benedicta of the Cross

O my God, fill my soul with holy joy, courage and

strength to serve You. Enkindle Your love in me and then walk with me along the

next stretch of road before me. I do not see very far ahead, but when I have

arrived where the horizon now closes down, a new prospect will prospect will

open before me, and I shall meet it with peace. Saint Teresa

Benedicta of the Cross

MLA Citation

“Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross“. CatholicSaints.Info.

14 November 2020. Web. 10 August 2021. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-teresa-benedicta-of-the-cross/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-teresa-benedicta-of-the-cross/

1. The hope of building a more just world, a world

more worthy of the human person, stirred by the expectation of the impending

Third Millennium, must be coupled with an awareness that human efforts are of

no avail if not accompanied by divine grace: “Unless the Lord builds the house,

those who build it labour in vain” (Ps 127:1). This must also be a

consideration for those who in these years are seeking to give Europe a new

configuration which would help the Continent to learn from the richness of her

history and to eliminate the baneful inheritances of the past, so as to respond

to the challenges of a changing world with an originality rooted in her best

traditions.

There can be no doubt that, in Europe's complex

history, Christianity has been a central and defining element, established on

the firm foundation of the classical heritage and the multiple contributions of

the various ethnic and cultural streams which have succeeded one another down

the centuries. The Christian faith has shaped the culture of the Continent and

is inextricably bound up with its history, to the extent that Europe's history

would be incomprehensible without reference to the events of the first

evangelization and then the long centuries when Christianity, despite the

painful division between East and West, came to be the religion of the European

peoples. Even in modern and contemporary times, when religious unity

progressively disintegrated as a result both of further divisions between

Christians and the gradual detachment of culture from the horizon of faith, the

role played by faith has continued to be significant.

The path to the future cannot overlook this fact, and

Christians are called to renew their awareness of it, in order to demonstrate

faith's perennial potential. In the building up of Europe, Christians have a

duty to make a specific contribution, one which will be all the more valid and

effective to the extent that they themselves are renewed in the light of the

Gospel. In this way they will carry forward that long history of holiness which

has traversed the various regions of Europe in the course of these two

millennia, in which the officially recognized Saints are but the towering peaks

held up as a model for all. For through their upright and honest lives inspired

by love of God and neighbour, countless Christians in a wide range of

consecrated and lay vocations have attained a holiness both authentic and

widespread, even if often hidden.

2. The Church has no doubt that this wealth of

holiness is itself the secret of her past and the hope of her future. It is the

finest expression of the gift of the Redemption, which ransoms man from sin and

gives him the possibility of new life in Christ. The People of God making their

pilgrim way through history have an incomparable support in this treasure of

holiness, sensing as they do their profound union with the Church in glory,

which sings in heaven the praises of the Lamb (cf. Rev 7:9-10) and

intercedes for the community still on its earthly pilgrimage. Consequently,

from very ancient times the Saints have been looked upon by the People of God

as their protectors, and by a singular practice, certainly influenced by the

Holy Spirit, sometimes as a request of the faithful accepted by the Bishops,

and sometimes as an initiative of the Bishops themselves, individual Churches,

regions and even Continents have been entrusted to the special patronage of

particular Saints.

Accordingly, during the celebration of the Second

Special Assembly for Europe of the Synod of Bishops, on the eve of the Great

Jubilee of the Year 2000, it has seemed to me that the Christians of Europe, as

they join their fellow-citizens in celebrating this turning-point in time, so

rich in hope and yet not without its concerns, could draw spiritual benefit

from contemplating and invoking certain Saints who are in some way particularly

representative of their history. Therefore, after appropriate consulation, and

completing what I did on 31 December 1980 when I declared Co-Patrons of Europe,

along with Saint Benedict, two Saints of the first millennium, the brothers

Cyril and Methodius, pioneers of the evangelization of the East, I have decided

to add to this group of heavenly patrons three figures equally emblematic of

critical moments in the second millennium now drawing to its close: Saint

Bridget of Sweden, Saint Catherine of Siena and Saint Theresa Benedicta of the

Cross. Three great Saints, three women who at different times—two in the very

heart of the Middle Ages and one in our own century—were outstanding for their

fruitful love of Christ's Church and their witness to his Cross.

3. Naturally the vistas of holiness are so rich and

varied that new heavenly patrons could also have been chosen from among the

other worthy figures which every age and region can vaunt. Nevertheless I feel

that the decision to choose this “feminine” model of holiness is particularly

significant within the context of the providential tendency in the Church and

society of our time to recognize ever more clearly the dignity and specific

gifts of women.

The Church has not failed, from her very origins, to

acknowledge the role and mission of women, even if at times she was conditioned

by a culture which did not always show due consideration to women. But the

Christian community has progressively matured also in this regard, and here the

role of holiness has proved to be decisive. A constant impulse has come from

the icon of Mary, the “ideal woman”, Mother of Christ and Mother of the Church.

But also the courage of women martys who faced the cruelest torments with

astounding fortitude, the witness of women exemplary for their radical commitment

to the ascetic life, the daily dedication of countless wives and mothers in

that “domestic Church” which is the family, and the charisms of the many women

mystics who have also contributed to the growth of theological understanding,

offering the Church invaluable guidance in grasping fully God's plan for women.

This plan is already unmistakably expressed in certain pages of Scripture and,

in particular, in Christ's own attitude as testified to by the Gospel. The

decision to declare Saint Bridget of Sweden, Saint Catherine of Siena and Saint

Teresa Benedicta of the Cross Co-Patronesses of Europe follows upon all of

this.

The real reason then which led me to these three

particular women can be found in their lives. Their holiness was demonstrated

in historical circumstances and in geographical settings which make them

especially significant for the Continent of Europe. Saint Bridget brings us to

the extreme north of Europe, where the Continent in some way stretches out to

unity with the other parts of the world; from there she departed to make Rome

her destination. Catherine of Siena is likewise well-known for the role which

she played at a time when the Successor of Peter resided in Avignon; she

brought to completion a spiritual work already initiated by Bridget by becoming

the force behind the Pope's return to his own See at the tomb of the Prince of

the Apostles. Finally, Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, recently canonized, not

only lived in various countries of Europe, but by her entire life as thinker,

mystic and martyr, built a kind of bridge between her Jewish roots and her

commitment to Christ, taking part in the dialogue with contemporary

philosophical thought with sound intuition, and in the end forcefully

proclaiming by her martyrdom the ways of God and man in the horrendous atrocity

of the Shoah. She has thus become the symbol of a human, cultural and religious

pilgrimage which embodies the deepest tragedy and the deepest hopes of Europe.

4. The first of these three great figures, Bridget,

was born of an aristocratic family in 1303 at Finsta, in the Swedish region of

Uppland. She is known above all as a mystic and the foundress of the Order of

the Most Holy Saviour. Yet it must not be forgotten that the first part of her

life was that of a lay woman happily married to a devout Christian man to whom

she bore eight children. In naming her a Co-Patroness of Europe, I would hope

that not only those who have received a vocation to the consecrated life but

also those called to the ordinary occupations of the life of the laity in the

world, and especially to the high and demanding vocation of forming a Christian

family, will feel that she is close to them. Without abandoning the comfortable

condition of her social status, she and her husband Ulf enjoyed a married life

in which conjugal love was joined to intense prayer, the study of Sacred

Scripture, mortification and charitable works. Together they founded a small

hospital, where they often attended the sick. Bridget was in the habit of

serving the poor personally. At the same time, she was appreciated for her

gifts as a teacher, which she was able to use when she was required to serve at

Court in Stockholm. This experience was the basis of the counsel which she

would later give from time to time to princes and rulers concerning the proper

fulfilment of their duties. But obviously the first to benefit from these

counsels were her children, and it is not by chance that one of her daughters,

Catherine, is venerated as a Saint.

But this period of family life was only a first step.

The pilgrimage which she made with her husband Ulf to Santiago de Compostela in

1341 symbolically brought this time to a close and prepared her for the new

life which began a few years later at the death of her husband. It was then that

Bridget recognized the voice of Christ entrusting her with a new mission and

guiding her step by step by a series of extraordinary mystical graces.

5. Leaving Sweden in 1349, Bridget settled in Rome,

the See of the Successor of Peter. Her move to Italy was a decisive step in

expanding her mind and heart not simply geographically and culturally, but

above all spiritually. In her desire to venerate the relics of saints, she went

on pilgrimage to many places in Italy. She visited Milan, Pavia, Assisi, Ortona,

Bari, Benevento, Pozzuoli, Naples, Salerno, Amalfi and the Shrine of Saint

Michael the Archangel on Mount Gargano. Her last pilgrimage, made between 1371

and 1372, took her across the Mediterranean to the Holy Land, enabling her to

embrace spiritually not only the many holy places of Catholic Europe but also

the wellsprings of Christianity in the places sanctified by the life and death

of the Redeemer.

Even more than these devout pilgrimages, it was a

profound sense of the mystery of Christ and the Church which led Bridget to

take part in building up the ecclesial community at a quite critical period in

the Church's history. Her profound union with Christ was accompanied by special

gifts of revelation, which made her a point of reference for many people in the

Church of her time. Bridget was recognized as having the power of prophecy, and

at times her voice did seem to echo that of the great prophets of old. She

spoke unabashedly to princes and pontiffs, declaring God's plan with regard to

the events of history. She was not afraid to deliver stern admonitions about

the moral reform of the Christian people and the clergy themselves (cf. Revelations, IV,

49; cf. also IV, 5). Understandably, some aspects of her remarkable mystical

output raised questions at the time; the Church's discernment constantly

referred these back to public revelation alone, which has its fullness in

Christ and its normative expression in Sacred Scripture. Even the experiences

of the great Saints are not free of those limitations which always accompany

the human reception of God's voice.

Yet there is no doubt that the Church, which

recognized Bridget's holiness without ever pronouncing on her individual

revelations, has accepted the overall authenticity of her interior experience.

She stands as an important witness to the place reserved in the Church for a

charism lived in complete docility to the Spirit of God and in full accord with

the demands of ecclesial communion. In a special way too, because the

Scandinavian countries from which Bridget came were separated from full

communion with the See of Rome during the tragic events of the sixteenth

century, the figure of this Swedish Saint remains a precious ecumenical

“bridge”, strengthened by the ecumenical commitment of her Order.

6. Slightly later in time is another great woman,

Saint Catherine of Siena, whose role in the unfolding history of the Church and

also in the growing theological understanding of revelation has been recognized

in significant ways, culminating in her proclamation as a Doctor of the Church.

Born in Siena in 1347, she was blessed from her early

childhood with exceptional graces which enabled her to progress rapidly along