Saint Nicolas du Japon

(+ 1912)

Originaire de la province

de Smolensk en Russie, il voulait devenir militaire. Mais une fois ses études

finies, il se décida à évangéliser le Japon. Après quatre années à l'académie

de Saint Petersbourg, il partit à Khakondate où il apprit seul le japonais.

Après des années de patience, il put réunir une petite communauté orthodoxe et

transféra son centre missionnaire à Tokyo qui était alors la nouvelle capitale

de l'empire. Il ouvrit un séminaire pour la formation du clergé autochtone où

l'on enseignait les langues chinoise, japonaise et russe. Durant la guerre

russo-japonaise de 1905, il continua d'aimer ses ouailles d'un grand amour et

c'est ainsi qu'il fut et qu'il est encore une source de grâce pour l'Eglise

orthodoxe du Japon.

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/5535/Saint-Nicolas-du-Japon.html

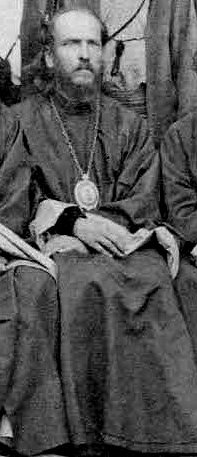

Nicholas of Japan, 1882

Saint Nicolas du Japon

Saint Nicolas du Japon était

un exemple unique et remarquable pour tous les missionnaires chrétiens

orthodoxes. Premièrement, il s'est jeté à corps perdu dans la compréhension de

la langue et la culture [du Japon]. Quand il le surprenait à lire des livres

dans une langue autre que le japonais, son archevêque le réprimandait, et il

résolut de ne lire que de la littérature japonaise. Il sortit de sa communauté

et écouta les conteurs et prédicateurs bouddhistes et shintoïstes. Il étudia

l'histoire du Japon. Il la connaissait mieux que la plupart des Japonais.

Deuxièmement, il avait

des vues à long terme pour sa mission. Il passa huit ans en recherches sur la

langue et la culture japonaises. Son premier converti vint après quatre années

d'études. Vue à long terme signifie également la délégation. En 1869 (cinq ans

après la première conversion!), il a remis sa congrégation à un autre

missionnaire. Après avoir établi une congrégation, il partit à Tokyo afin d'en

mettre en place une autre. Ce modèle d'établissement, de délégation et de

mobilité a marqué son ministère.

Troisièmement, il comprit

le peuple. Son premier chrétien, était un samouraï appelé Sawabe. Takuma.

Sawabe était un ultra-nationaliste (l'un des types de personnes dans des

mini-fourgonnettes noires qui nous feraient peur de nos jours) qui considérait

le consulat de Russie comme le symbole de tous les problèmes de l'ouverture du

pays aux étrangers. Lorsque Sawabe vint au consulat, épée tirée, prêt à tuer

Nicolas, Nicolas sut faire appel à sa nature de Samuraï:

"Pourquoi êtes-vous

en colère contre moi?" a demandé Père Nicolas à Sawabe.

"Vous, tous les

étrangers devez mourir. Vous êtes venus ici pour espionner notre pays et ce qui

est pire encore, vous faites du mal au Japon avec votre prédication,"

répondit Sawabe.

"Mais savez-vous ce

que je prêche?" a répondu Nicolas.

"Non,"

répondit-il.

"Alors comment

pouvez-vous juger, et encore moins condamner quelque chose dont vous ne savez

rien? Est-il juste de diffamer quelque chose que vous ne connaissez pas?

Ecoutez-moi, d'abord, puis jugez. Si ce que vous entendez est mauvais, alors

jetez-nous dehors."

Sawabe l'écouta alors, et

fut persuadé par ses paroles et par l'Esprit Saint qui agissait en lui. Nicolas

a su se faire écouter de Sawabe. Comment aujourd'hui, beaucoup d'entre nous

peuvent-ils dire honnêtement que nous savons comment nous faire écouter des

Japonais et leur faire entendre notre message?

Quatrièmement, il a été

dévoué à son peuple. C'est une question d'intégrité. Il avait besoin que le

peuple japonais sache qu'il était de leur côté. Beaucoup de missionnaires

préfèrent se fier à leur pays d'origine quand les choses deviennent difficiles,

mais Nicolas était absolument engagé pour le Japon, et sa congrégation

connaissait son amour par son dévouement pour eux. Lorsque le Japon et la

Russie sont entrés en guerre, beaucoup de gens de sa propre congrégation le

pressèrent de rentrer chez lui [en Russie] -Rappelez-vous qu'il était venu au

Japon sous l'égide du Consulat de Russie au Japon. Mais il a refusé, il avait

besoin de servir et d'être avec son peuple. Dans le même temps, il a trouvé des

moyens pour s'occuper des prisonniers de guerre russes au Japon.

Enfin, il fut prompt à

déléguer, comme nous l'avons déjà mentionné. Quand Paul Sawabe commença à

croire, il a amené trois amis avec lui pour entendre la prédication de Nicolas.

Nicolas laissa les quatre croyants autochtones faire leurs propres disciples,

et un an plus tard, il y avait douze baptisés, et vingt-cinq de ce que nous

appellerions aujourd'hui "personnes en recherche". Quinze ans plus

tard, l'église était forte de quatre mille hommes. Pour que cela fonctionne, il

fallait encore plus de délégation, et ainsi il a commencé le processus

d'ordination de prêtres japonais. Au moment où il vint fêter les cinquante

années de sa mission, il y avait quarante-trois prêtres ordonnés et cent

vingt-et-un prédicateurs laïcs. Et rappelons-nous que, cinq ans après avoir une

personne dans l'Église, il la confia [à Sawabe] et partit à Tokyo. Il savait

que s'il voulait atteindre l'ensemble du Japon, il ne pouvait se borner à un

seul territoire pour l'ensemble de sa vie missionnaire.

Version française Claude Lopez-Ginisty d'après Père Geoffrey Korz. Mission Notes: Saint Nicholas of Japan in http://www.pravmir.com/article_420.html

SOURCE : http://orthodoxologie.blogspot.ca/2010/02/saint-nicolas-du-japon.html

SAINT NICOLAS du Japon

16 février / 3 février

Saint Nicolas du Japon fut un missionnaire Russe qui

partit pour le Japon au XIXe siècle, et c'est un des plus grands saints

missionnaires des temps modernes

Son nom de Baptême était Jean, et il naquit le 22

août1836, second fils de Dimitri Ivanovitch Kasatkin, qui était diacre de

l'église de Beryoza dans la province de Smolensk. Il étudia la théologie à

l'Académie théologique de Saint-Petersbourg

Il fut nommé chapelain du consulat Russe à Hakodate.

Il traversa la Sibérie en calèche en juillet 1860, et atteint Nikolaevsk à la

fin septembre. Il y demeura pour l'hiver, et là il rencontra le célèbre

missionnaire de Sibérie et d'Alaska, Saint Innocent (Veniaminov) d'Alaska. Il

continua son voyage l'année suivante et atteint Hakodate en juillet 1861

A sa demande, le père Nicolas fut affecté au Japon

dans la ville de Hakodate.

Au début, la prédication de l'Évangile au Japon lui

parut complètement impossible. Selon ses propres mots : "De tout temps, le

Japonais a considéré des Étrangers comme des bêtes, et voit dans le

christianisme comme la partie la plus mauvaise, à laquelle seulement les

bandits et les sorciers peuvent appartenir." Il passa huit ans à étudier

le pays, la langue, des façons et des coutumes du peuple parmi qui il prêcherait.

Il donna aussi des leçons de russe aux Japonais qui étaient intéressés.

En 1868, Nicolas avait regroupé autour de lui une

vingtaine de japonais. Après son retour à Moscou, la décision fut prise, en

1870, de former une mission spirituelle russe spéciale pour prêcher la parole

de Dieu parmi les Japonais païens et de nommer le père Nicolas au grade

díarchimandrite et nommé comme chef de cette mission.

Après deux ans passés en Russie, le Père Nicolas

retourna au Japon. Il transféra la responsabilité de la communauté de Hakodate

au hiéromoine Anatole, et commença sa mission d'évangélisation à Tokyo .

En 1871, les premiers chrétiens de Hadokate furent persécutés

et arrêtés dont le premier prêtre orthodoxe japonais : Paul Sawabe. En 1873 les

persécutions diminuèrent et la prédication devint plus libre.

En 1874, l'Archimandrite Nicolas commença la

construction d'une église, d'un séminaire pour une cinquantaine d'hommes et

d'une école religieuse. La même année l'Évêque Paul du Kamtchaka vint à Tokyo

pour y ordonner prêtres plusieurs japonais recommandés par Nicolas.

Plusieurs écoles virent le jour : quatre à Tokyo et

deux à Hakodate.

En 1877 la mission publia régulièrement un journal : «

Le héraut de l'Église ». En 1878 on comptait 4 115 convertis répartis en

plusieurs communautés et Nicolas demanda bientôt que soit nommé un évêque

supplémentaire.

Un Samurai, propriétaire terrien et prêtre Shintoïste,

Takuma Sawabe, considéra le père Nicolas comme une menace pour le Japon et sa

culture, et vint au consulat où il le menaça de le tuer s'il n'arrêtait pas

d'enseigner la Foi Chrétienne au peuple. La réponse de Nicolas fut simple : il

lui demanda s'il savait ce que lui enseignait. Sawabe dit qu'il ne savait pas,

et Nicolas lui demanda s'il était raisonnable pour lui de tuer quelqu'un pour

avoir enseigné ce qu'il ignorait, et s'il ne serait pas plus raisonnable

d'écouter d'abord ce qu'il enseignait. Sawabe accepta d'écouter... et fut

convaincu de la vérité de la Foi Chrétienne Orthodoxe.

L'Archimandrite Nicholas fut consacré évêque le 30

mars 1880 dans la cathédrale de La Trinité à la laure st Alexandre Nevski.

Retournant au Japon, il reprit son travail apostolique avec une ferveur accrue.

Il termina la construction de la cathédrale de la Résurrection du Christ à

Tokyo, il traduisit des livres et créa un dictionnaire théologique orthodoxe

spécial dans la langue japonaise.

Le saint et ses communautés eurent de graves problèmes

lors de la guerre Russo-Japonaise. Pour son travail pendant ces années

difficiles, il fut élevé au rang d'archevêque.

En 1911, un demi-siècle après son arrivée au Japon, il

y avait 33.017 chrétiens dans les 266 communautés de l'église orthodoxe

japonaise, y compris 1'Archevêque, 1 évêque, 35 prêtres, 6 diacres, 14

instructeurs chanteurs, et 116 catéchistes.

Le 3 février 1912, l'Archevêque Nicholas parti

paisiblement vers le seigneur à l'âge de soixante-seize ans.

SOURCE : http://www.histoire-russie.fr/icone/saints_fetes/textes/nicolas_japon.html

Saint Nicholas, Enlightener of Japan

Commemorated on February 3

Saint Nicholas (Kasatkin) Equal of the Apostles,

Bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church. Missionary, Founder of the Orthodox Church

in Japan, honorary member of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society. (Name

Day: May 9).

Saint Nicholas (in the world John Kasatkin) was born

on August 1,1836 in the village of Berezovsky Pogost, Belsky District, Smolensk

Province into the family of a deacon. He graduated from the Belsk Theological

School and the Smolensk Theological Seminary (1857). Among the best students he

was recommended for the St. Petersburg Theological Academy, where he studied

until 1860, when, at the personal request of Metropolitan Gregory (Postnikov)

of St. Petersburg, he was given the post of rector of the church at the Russian

consulate in the city of Hakodate (Japan), and was also awarded a Ph.D in

Theology without having to submit an appropriate qualifying essay.

On June 23, 1860, he was tonsured by the rector of the

Academy, Bishop Nektarios (Nadezhdin), and named for Saint Nicholas of Myra. On

June 30 he was ordained a Hieromonk.

He arrived at Hakodate on July 2, 1861. During the

first years of his stay in Japan, on his own he studied the Japanese language,

culture and way of life.

The first Japanese person to convert to Orthodoxy,

despite the fact that conversion to Christianity was forbidden by law, was the

adopted son of a Shinto cleric, Takuma Sawabe, a former samurai who was

baptized with two other Japanese in the spring of 1868.

During his half-century of service in Japan, Father

Nicholas left only twice: in 1869-1870 and in 1879-1880. In 1870, through his

intercession, a Russian ecclesiastical mission was opened in Japan with its

center in Tokyo. On March 17, 1880, by the decision of the Holy Synod, he was

assigned as vicar of Reval, then vicar of the Diocese of Riga. He was

consecrated as a Bishop on March 30, 1880, in Holy Trinity Cathedral at

Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

In the course of his missionary work, Father Nicholas

translated the Holy Scriptures and other liturgical books into Japanese; he

established a theological seminary, six theological schools for girls and boys,

a library, a shelter and other institutions. He published the Orthodox journal

Church Herald in Japanese. According to his report to the Holy Synod, by the

end of 1890 the Orthodox Church in Japan numbered 216 communities with 18,625

Christians in them.

On March 8, 1891, the Cathedral of the Resurrection in

Tokyo, called Nikorai-do (ニコライ堂)

by the Japanese, was consecrated. During the Russo-Japanese War, he remained

with his flock in Japan, but did not take part in any public services. because

according to the rite of worship (and the blessing of Japanese Christians to

pray for their country's victory over Russia. Bishop Nicholas said:

"Today, according to custom, I serve in the cathedral, but from now on I

will no longer take part in the public services of our church... Hitherto I

have prayed for the prosperity and peace of the Empire of Japan. Now, since war

has been declared between Japan and my country, I, as a Russian subject, cannot

pray for Japan's victory over my own homeland. I also have obligations to my

country, and that is why I will be happy to see that you fulfill your duty in

relation to your country."

When Russian prisoners of war began to arrive in Japan

(their total number reached 73,000 people), Bishop Nicholas, with the consent

of the Japanese government, formed the Society for the Spiritual Consolation of

Prisoners of War. For their spiritual guidance, he selected five priests who

spoke Russian. The prisoners were provided with icons and books. Vladyka

repeatedly addressed them in writing (he himself was not allowed to see the

prisoners).

On March 24, 1906, he was elevated to the rank of

Archbishop of Tokyo and All Japan. In the same year, the Kyoto Vicariate was

founded. In 1911, when half a century of Saint Nicholas' s missionary work was

completed, there were already 266 communities of the Japanese Orthodox Church,

which included 33,017 Orthodox laymen.

Archbishop Nicholas, the Enlightener of Japan, fell

asleep in the Lord on February 3, 1912 at the age of 76, After the Hierarch's

repose, the Japanese Emperor Meiji personally gave permission for him to be

buried within the city, at the Yanaka cemetery. In Japan, Saint Nicholas is

revered as a great righteous man and a special intercessor before the Lord.

He was canonized on April 10, 1970, by the decision of

the Holy Synod of the Moscow Patriarchate. A Service was composed for him by

Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) of Leningrad and Novgorod, and published in 1978.

Saint Nicholas is also commemorated on the Sunday

before July 28 (Synaxis of the Smolensk Saints).

SOURCE : https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2026/02/03/100455-saint-nicholas-enlightener-of-japan

Enlightener of Japan –

Blessed Nicholas Kasatkin

By Presbytera Doreen

Bartholomew

On August 1, 1836, one of

the greatest missionaries in the history of the Orthodox Church was born, a man

who, in the course of his life in Japan, left behind over two hundred churches,

more than 30,000 Orthodox Christians, translations of almost the entire Bible,

almost all of the Orthodox liturgical texts and theological literature; a man

who founded several schools, a seminary, a library and countless other

institutions, some of which are still functioning today.

The early life of Ivan

Dimitrievich Kasatkin was one of poverty and great hardship. His mother died

when he was very young and he was brought up by his father, the village deacon.

He was full of life and very mischievous but his pranks ceased when he entered

the church for services. He sang and prayed with such attentiveness that it

seemed inevitable he would enter the seminary, which he did in 1853.

The Smolensk Seminary was

150 miles from Ivan’s home and, being one of the poorer seminarians, he was

forced to walk back and forth at the beginning and end of term. Nevertheless,

he never lost his sense of humor and remained a good student. After graduation

in 1857 he was offered a scholarship to the St. Petersburg Theological Academy

where he continued his studies, showing a particular gift for patristics and

foreign languages. After graduation Ivan was invited to stay at the St.

Petersburg Theological Academy to prepare for an academic seat, but one day a

notice appeared on the bulletin board requesting applications from students

interested in a consular posting in Japan. Ivan was intrigued. Five people

applied, he being one of them. However, the other four applicants withdrew

their application upon learning that the position called for a celibate priest.

Ivan had never considered the monastic life, but his call to Japan was so

strong that it did not present a problem. Bishop Nektary, the rector of the

Academy, was originally opposed to Ivan being sent to Japan, feeling that a man

with such academic abilities would be wasting his talents in a consular position.

Ivan agreed that such a position would be a waste of time, but he was planning

to evangelize Japan. After much thought Bishop Nektary finally consented, but

the other members of the Holy Synod hesitated at sending such a young man, with

no experience behind him. It was only after the agreement of Metropolitan

Isidore, Ivan’s spiritual father, that permission was granted. On June 22,

1860, Ivan Kasatkin made his monastic profession, receiving the name of

Nicholas. After his ordination to the diaconate on June 22 and to the

priesthood on June 29, he was ready to begin his journey to Japan.

On July 29 Nicholas left

St. Petersburg for his new assignment in Hakodate, Japan. The journey was

arduous: in order to reach his point of embarkation at Nikolaevsk-on-Amur he

had to cross the Volga region, the Urals and all of Siberia-a distance of 6,214

miles-all done on carriages and sleds. When he arrived in Nikolaevsk it was

winter and further travel was impossible due to frozen conditions. Fr. Nicholas

was forced to spend the winter of 1861 in Nikolaevsk. This turned out to be a

blessing instead of the waste of time he thought it would be. During this time

he had the opportunity to speak with Archbishop Innocent (Veniaminov), the

missionary to America. Archbishop Innocent was forty years Nicholas’ senior and

was almost at the end of his missionary career. The hierarch told him that his

first goal had to be to master the Japanese language, and next, to translate

the Bible, especially the Gospels. He cautioned Fr. Nicholas not to expect too

much, that his life in Japan would be filled with great disappointments as well

as good times. He advised him not to despair when he found himself longing for

his native Russia, that the feeling would pass and soon Japan would seem almost

like home.

Archbishop Innocent

decided Fr. Nicholas’ cassock was too worn to make a good impression in Japan,

and he helped Fr. Nicholas to cut and sew a new one. He also gave him the

bronze cross he had been wearing.

With the arrival of

spring Fr. Nicholas continued his journey to Japan aboard the military

transport vessel Amur. He reached Hakodate on June 14, 1861, almost a year

after leaving St. Petersburg.

It was not a good time

for missionary work in Japan. The Japanese regarded foreigners with suspicion,

even hatred. For the most part they ignored missionaries, but they were quite

prepared to kill them at the drop of a hat. The preaching of Christianity was

strictly prohibited and converts to Christianity faced torture or even death.

Missionaries walking on the streets were often assaulted by stone-throwing

crowds.

This was hard on the

young hieromonk; he had imagined flocks of people gathering to hear his

preaching, once the word of God had been heard. “Imagine my disappointment,” he

wrote, “when I arrived in Japan only to be greeted by the exact opposite of

what I had dreamed.” He resigned himself to being restricted to performing the

Divine services for the small Russian community at the consulate. He tried to

hire a Japanese teacher, but this proved almost impossible; no Japanese wanted

to be seen with a foreigner, let alone a missionary. This being the case he

contented himself with reading the German and French books he found in the

consulate and began evolving into the kind of chaplain he promised Bishop

Nektary he would never become.

At this time Archbishop

Innocent was on a trip to Kamchatka and, being delayed in Hakodate for a few

days, he decided to drop in on the young missionary. Learning of the sad state

of affairs, the hierarch advised Fr. Nicholas to throw away the French and

German books and begin a serious study of Japanese. Soon Fr. Nicholas was able

to find a language tutor and he began to study diligently. In the end, Fr.

Nicholas needed three teachers to maintain his pace in learning. In addition to

this private tutoring Fr. Nicholas began to attend the Japanese schools, never

saying a word but just listening to the lectures. There is a story recorded in

the memoirs of Shimomura Kainan, the editor of Tokyo Asahi newspaper, which

tells of Fr. Nicholas’ going to school and the reaction of the school

authorities. The school sought to keep Fr. Nicholas out, fearing reprisals

should the government find out that a Christian missionary, a Russian no less,

was attending classes. They tried everything, even threatening him with

violence. In the end a notice was placed on the school gates saying “Entrance

Forbidden to Russian Priest”. Fr. Nicholas read the notice, put it in his

pocket and went to class. Eventually they let him stay, simply because they

could not get him to leave.

The Japanese language

consists of three systems of writing, two being hiragana and katakana, and the

Chinese characters known as Kanji. Hiragana is used to show some Japanese

grammer while katakana is used to transcribe foreign words and onomatopeia. Any

foreigner wishing to study the language had to do so without the use of modern

grammers, textbooks or other learning tools available to students today. This

meant that Fr. Nicholas had to devise his own system of study; it worked so

well that he rapidly gained a working knowledge of the language.

After seven years of

language study, Fr. Nicholas felt he was prepared to begin conversion of the

Japanese. As it happens, his first “catechumen” came with sword in hand and

murder in his mind. Takuma Sawabe, a samurai Shinto priest and devoted

nationalist, came to Fr. Nicholas one night and told him that all foreigners

must die because they spread lies and are here to spy on Japan. Sawabe demanded

that Fr. Nicholas either leave Japan at once or prepare to die. Fr. Nicholas

heard him out and then asked if Sawabe was acquainted with what he preached.

Sawabe admitted that he was not and Fr. Nicholas asked him why he was

condemning him to death without a hearing first. Sawabe agreed to hear what Fr.

Nicholas had to say before killing him.

Fr. Nicholas began to

preach the Gospel to Sawabe. He spoke of God, sin, the soul and its

immortality. Sawabe listened intently, then took out some paper and began to

take notes. He came back again and again and became so filled with love for his

newfound faith that he was baptized and received the name of Paul. Soon Sawabe

began to talk of Orthodoxy to his friends, specifically Sakai and Urano. They

were also converted to Orthodoxy and in April of 1868 received baptism with the

names of John and Jacob, respectively. The cornerstone for the building of

Orthodoxy in Japan had been put in place through the events of one night.

Around this time

political change was in the air and the Shogun’s government wanted to stop it.

They placed road blocks everywhere and the police arrested any suspicious

characters. Knowing of the danger to Japanses Christians, in Hakodate

specifically, Fr. Nicholas ordered Sawabe, Sakai and Urano to leave Hakodate at

once. He armed them with a variety of religious books but really did not expect

much in the way of preaching from them. It was enough that they were safe. In

the meantime Fr. Nicholas’ catechumens were growing in number. One, baptized as

John Ono, was later to become the first native bishop of the Japanese Orthodox

Church. (John Ono’s great-grandson is now a priest at the cathedral in Tokyo,

also having taken the name of John at baptism.)

In 1869 the Holy Synod

ordered Hieromonk Nicholas to return to St. Petersburg to work towards the

establishment of a Russian Orthodox mission in Japan. The Japanese Missionary

Society was granted 6,000 rubles annually, which was received until the

beginning of the Russo-Japanese War. In addition, Metropolitan Isidore raised

Fr. Nicholas to the rank of Archimandrite and appointed him head of the

mission. It was put under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Kamchatka. Fr.

Nicholas returned to Japan on February 15, 1871 with a few monks to assist him.

They all soon left due to illness or personal reasons. During his absense,

Sawabe, Sakai and Urano continued their missionary activities and Fr. Nicholas

returned to a whole new flock of catechumens.

Upon his return from

Russia, Fr. Nicholas increased his translation effort. He had met Dr. Mayama, a

scholar from the city of Sendai in the northern part of Japan, and together

with John Ono they translated and published a Russian-Japanese Dictionary, a

catechism, prayerbook, wall calendar and Lives of the saints.

It is important to

understand the emphasis Fr. Nicholas put on his translation work. It was

extremely important to him; he considered that the soul of the mission’s work

was to be found in the translation of books. He, therefore, spent most of his

time in translation. For thirty years he spent every evening from six until ten

with his assistant, Nakai, and translated. The only time this routine was

broken was on days when there were evening services. During the hours of

translation the door was shut and only his aide, Ivan, could enter to serve

tea. “Were the heavens to unfold I would have no right to abandon my

translation work,” said Fr. Nicholas.

He always strove for

perfection and was never satisfied, always seeking new forms. The Lord’s

Prayer, for example, went through four revisions. He began by using already

existing Chinese translations but this did not succeed. The Chinese

translations were either too literal or too much like paraphrases. This forced

him to follow the Russian and Slavonic texts closely while also using the Vulgate,

the English version and the Greek. Using this method, he was able to translate

at the rate of fifteen verses per five hours of work. It was in this manner

that the Gospels were translated. After his move to Tokyo the scope of his work

increased. He began work on the Sunday cycle, then moved to the Pentecostarion

and the Lenten Triodion. Gradually, the whole cycle of services and all the

parts of the Old Testament necessary for services were translated, and he still

dreamed of translating the entire Bible.

Fr. Nicholas’ biggest

problem was choosing the proper Chinese characters and not simply using ones

that have special meaning in the Buddhist and Shinto canons. For example, the

Buddhist terms referring to an absolute being as impersonal, such as Nirvana, are

completely different from the Orthodox teaching of a personal God, paradise and

free will. Sometimes selection of one character took hours of discussion; there

were even cases where letters to the entire church were sent requesting

suggestions as to a suitable translation.

Fr. Nicholas’

translations have been criticized as being too difficult for Japanese to read.

His attitude towards this was that the level of translations of the Gospels and

the services should never descend to the level of the masses; rather, the

masses should be raised to the level of the Gospels and services. He said that

popular language was not admissible in the Gospels. If there were two

completely identical characters and both were equally pleasing to the ear, he

would naturally choose the simpler of the two, but he never would make the

slightest compromise in the accuracy of the translations, even if it meant

using little known characters. The move to Tokyo took place in January of 1872

and Nicholas took up residence in Tsukiji, one of the places designated for

foreigners. When he arrived in Tsukiji he found it difficult to find a place to

live. He ended up spending nights at the house of an Englishman and being

forced to wander around the city during the day. Finally he found a small house

consisting of two rooms, the larger of which could-with all the furniture

removed-hold ten people. Although it was still illegal to preach Christianity

in Japan, he managed to attract about fifteen listeners from the people in

Tsukiji. Meanwhile he continued his study of the language, making friends with

people in the area. He became particular friends with the abbot of Zojoji

Temple, and it was this abbot who sheltered him when the Japanese government

became suspicious of his activity.

Fr. Nicholas came to the

notice of the government in a positive way when he served as interpreter for

Tsar Alexander II during his visit to Japan in 1872. Meanwhile, the laws

against Christianity were becoming an embarrassment to Japan and its diplomatic

relations with western nations, and were soon revoked. Fr. Nicholas felt

reassured as a result of this and his recent service to the Japanese government

and so set about finding a suitable plot of land on which to build the mission.

He searched all over Tokyo but kept coming back to a residence on Surugadai

Hill. Surugadai was then the residence of Count Toda and when the property came

up for sale in 1872, Fr. Nicholas secured it. He first used the buildings for

preaching and teaching of the Russian language, but in 1873 he built two

European-style buildings and used the top floor of one building for a chapel.

In the midst of all this, he baptized his first group of ten catechumens.

It was in the 1870’s that

the Orthodox missionary activity ceased to be a “one man show” and truly became

an organized effort. A girls’ school was opened and a seminary. In addition,

four missions were opened in 1874 in Tokyo and one in Osaka in 1875. Soon to

follow were the catechist’s school, the orphanage, the iconography division of

the mission, the choir and the library. A monthly magazine, Seiko Shimpo, was

published. (It still exists under the name of Seiko Jiho or Orthodox Herald.)

On June 12, 1875, the

Synod of the Japanese Orthodox Church decided to ordain Paul Sawabe to the

priesthood and John Sakai to the diaconate. They were ordained by Bishop Paul

of Eastern Siberia and were soon followed in 1878 by Paul Sakai, Paul Sato,

Jacob Takaya, Matthew Kageta and Timothy Hariyu.

In 1880 Archimandrite

Nicholas was summoned to Russia and on March 3 he was consecrated Bishop of

Revel. He returned to Japan on October 17 with choir master Dimitry

Konstantinovich Lvov. Fr. Nicholas had long felt the need for a qualified music

teacher in the Japanese mission and with the help of J.D. Tikhai they set about

adapting the Japanese words to the Russian melodies. It was Tikhai who formed

the first choir in the cathedral and it was he who adapted the Obikhod for unison

singing in Japanese (these same books are still used for Vigil services.) When

Lvov arrived at the mission he was appointed a teacher of singing and soon

music was arranged for the festal and paschal services (1).

In the 1880s and 1890s the Orthdox Church of

Japan grew more, with magazines being published and people being sent abroad to

study. It is also during this period that construction of the cathedral

building began. Much money and labor went into this building which occupies

9,573 square feet and measures 110 feet in height, with a bell tower of 128

feet. The cornerstone was laid in 1884 and construction took seven years. It

was supervised by the English architect Josiah Conder, who designed many

buildings in Meiji Japan, and was built in the Byzantine style according to plans

drawn up by the Russian architect Michael Shicherpov.

Construction was not

without its problems, most of which came from the newspapers. The problem was

that the site occupied the highest ground in Tokyo, above and not far from the

Imperial Palace. Until very recently it was considered rude to build even an

office building more than three stories high lest it overlook the palace. This

was taken very seriously in the 1880s and there was a strong newspaper campaign

against the building of the cathedral. It was argued that it would become an

observation post and that the Russians must have some ulterior motive. Even

some Orthodox Christians were against it. Nevertheless, Bishop Nicholas

persisted and the cathedral was built.

Construction was

completed in 1891 and it was consecrated on March 8, and given the name of the

Cathedral of the Holy Resurrection. But from the first it was rarely referred

to by this name; it was simply called “Nikorai-do” or Nicholas’ house (“do”

meaning temple, or house). It is a most remarkable building and is considered

one of the great architectural achievements in Japan. A minor event worth

nothing is that the major bell in the belltower was donated by the then Grand

Duke Nicholas upon his visit to Japan in 1891.

On February 8, 1904, the

Russo-Japanese war began. To say that this put the Japanese Church in a

difficult position is an understatement. But thanks to the attitude and love of

Bishop Nicholas the Church was kept from falling apart. From the beginning of

the war there were attacks from the Japanese. The church was placed under

supervision and in some places Orthodox Christians were persecuted. The

Japanese press launched an all-out campaign against the Church.

At this point Bishop

Nicholas was asked by his flock if Orthodox Japanese could fight Orthodox

Russians. After studying the situation carefully he concluded that the Japanese

should fight, using the example of our Lord’s patriotism and loyalty. He told

the Japanese that Jesus Himself shed tears for the fate of Jerusalem, giving

proof of His patriotism and that they must follow in the footsteps of the

Teacher. He instructed them to do their duty as loyal Japanese subjects, to

pray for the victory of Japan and to do all things necessary to work for that

victory, but to do all this not out of hatred for the enemy, but for love of

their country.

The war put Bishop

Nicholas in a very difficult position. As a Russian, he could hardly pray for

the victory of Japan, yet he would not abandon his flock. He told the Church

that until the war was over he would not take part in the public prayers of the

Church, that he, too, had responsibilities to his homeland.

From the beginning of the

war a military guard was posted to the mission, and when a Japanese transport

was sunk by Russian cruisers more than a company of soldiers was placed outside

the mission. Recognizing the danger to Bishop Nicholas, the clergy asked if he

wanted to spend the remainder of the war outside Japan. Although well aware

that his life was in constant danger, he declined, choosing to remain with his

flock.

The Japanese Church did

not neglect its responsibilities to the over 70,000 Russian prisoners of war.

Eventually twenty Russian-speaking priests were set to serve as chaplains for

the prisoners. Reading materials were provided which included over two thousand

religious books and a thousand books on secular subjects. Independent of the

church effort, the Orthodox Christians organized the “Society for the Spiritual

Comfort of P.O.W.s” and collected donations for gifts and foodstuffs for the

prisoners. Meanwhile, in 1906, Bishop Nicholas was raised to the rank of

Archbishop and the Japanese Church celebrated his twenty-fifth anniversary as

bishop. In recognition of the Church’s work during the war, the Japanese

government donated a silver vase to the church and the Holy Synod in Russia

sent twenty gold altar crosses.

June 16, 1911 was the

fiftieth anniversary of the Archbishop’s arrival in Japan. He was then seventy

years old and had to begin thinking about an assistant. On June 27 Bishop

Sergius arrived and was appointed Bishop of Kyoto.

Archbishop Nicholas had

begun to suffer from heart disease in 1910, and the activities of the Church

and the celebration in 1911 had worsened his condition. In the beginning of the

winter of 1911 he became ill and in January of 1912 was admitted to St. Luke’s

Hospital in Tsukiji. The newspapers published daily bulletins about his illness

and many people called on him. On February 5, regardless of the fact that there

was no improvement in his condition, he decided to leave the hospital, saying

that there were too many things that needed to be done and there was no time to

waste in a hospital. He returned to Nikorai-do and continued his translation

work of the Old Testament. By February 15 he had recovered his strength enough

to write a final report to the Holy Synod and discuss with Bishop Sergius his

ten-year plan for the Church. While this meeting was in progress Archbishop

Nicholas noticed that the choir was not practicing as usual. He was told that

his doctors had advised the choir not to practice for fear it would disturb

him. He said he preferred that they practice and requested his favorite piece,

“By the Waters of Babylon”.

The Apostle of Japan

reposed at 7:15 a.m. on February 3 (OS), 1912, as Bishop Sergius was reading

the prayers for the departure of the soul. His last word was “resurrection.” At

that moment the doctor and the nurse-both unbelievers-fell to their knees in

honor of their great patient. The righteous hierarch-his life, his spiritual

countenance-made such an impression on the nurse that she said later:

“Definitely, I’m definitely going to get baptized.”

The bell of the cathedral

announced his passing and the Japanese Orthodox Church fell into a state of

mourning, as did the rest of Japan. After being dressed in his archepiscopal

vestments, the body of the hierarch was taken to the cathedral which was

already packed. Memorial services alternated with reading of the Gospel.

Countless wreaths arrived from parishioners, from Japanese nobility, the

diplomatic community, the mission; there was one from the Emperor himself.

In accordance with his

will, mourners paid respect to Nicholas bearing palm branches in hand. His

funeral was the largest one ever given a foreigner in Japan and none has

surpassed it since. The local English-language newspaper reported the details

which included the fact that the streets of Tokyo were lined with people,

ordinary Japanese citizens, who wished to say goodbye to the Enlightener of

Japan. He was buried in Yanaka Cemetery, close to the grave of the last

Tokugawa shogun.

There are those who think

that sanctity must necessarily be attested by miracles-and they look in vain

for such signs in the life of Archbishop Nicholas of Japan. During his final

illness he himself found nothing in which to boast. “Here I look back upon my

life… And what do I find? Only darkness! God alone accomplished everything,

while I… such a nonentity, zero, literally zero! And if a righteous man shall

scarcely be saved, then where shall I, a sinner, find myself? I’m worthy of the

very depths of hell.” This was, however, but evidence of his extraordinary humility

which crowned and safeguarded his outstanding achievements By the time of his

death, Japanese Orthodoxy had grown from one man with his single convert to

over 35,000 believers and thirty-two priests, all native Japanese! In addition

there were seven deacons, fifteen choir directors, 121 lay preachers, a

cathedral, ninety-six churches and 265 chapels. What further “sign” is needed?

And there is the miracle of his enduring legacy. For the last twenty years or

so, the Japanese Orthodox Church has been headed by Metropolitan Theodosius

(Nagashima) as an autonomous Church. Having recovered from the devastation of

the Great Kanto Earthquake and World War II, plus the cutting off of funds from

Russia after the Russian Revolution, the Church is now back up to around

thirty-thousand faithful. The cathedral itself has been declared a national

historic landmark and receives over five thousand visitors per year. Services

are sung entirely in Japanese and all the clergy are Japanese. A visit to the

cathedral is a must on any Tokyo itinerary.

Sources: Nicholas

Kasatkin and the Orthodox Church in Japan, by Roberta Takahashi; “The

Missionary Activity of St. Nicholas of Japan”, Master’s Thesis by The Rev. John

Bartholomew; A History of the Japanese Orthodox Church, by A. Bakulevski

(translation by Fr. John Bartholomew); Archbishop Nicholas of Japan:

Reminiscences and Characteristics, by Dimitrii Pozdneev (translation by Fr.

John Bartholomew).

Those acquainted with the

life of this hierarch have no doubt that he now dwells in the choirs of the

saints. He has already been glorified by several local Churches, and after the

glorification of Metropolitan Innocent (Veniaminov), Apostle to America, now in

preparation, it is earnestly hoped that the Russian Church Abroad will accord

the same official recognition to Archbishop Nicholas, Apostle to Japan. Grant

this, O Lord!

(1) The task of organizing

the church choir and setting Japanese liturgical texts to Russian music was a

difficult one. The Japanese texts are much longer, to begin with, and the

language is diametrically opposed to Russian in construction. In addition, the

Japanese language has a nasal “N” sound, which must be pronounced as a separate

syllable. When a beat falls on this sound it cannot be ignored but must be

sung. Bearing this in mind one can well imagine the difficulty the Japanese

texts presented to these musicians. Soon there were over one hundred male and

female voices in the choir and it was an ornament to the church. To this day,

students of music are brought to the cathedral to hear the choir, considered

one of the best in Japan.

SOURCE : https://www.roca.org/oa/volume-xii/issue-113-114/enlightener-of-japan-blessed-nicholas-kasatkin/

Enlightener of Japan

Blessed Nicholas Kassatkin

Matushka Naomi Takahashi

In these evil times when

the forces of materialism, ignorance and coldness of faith rise up against us,

the believers, and challenge us to prove at all moments our faith, whether or

not we are consciously aware of it, each of us is a missionary to those around

us who are in darkness; that is, we are wit nesses of the power and glory of

the Holy Spirit graciously transmitted to us through our Holy Orthodox Church.

As Christ our Saviour taught us in the parable of the talents, we are not to

bury our talents but to cultivate, invest and employ them that they might

manifest the reality of our faith in God. Each of us has different talents-for

some it is the achievement of virtues; for others, power of prayer; some are

gifted with practicing mercy and charity-and a few, special chosen are granted

missionary zeal and fervor to preach the Gospel to the far corners of the

earth.

Go ye therefore, and

teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son,

and of the Holy Spirit. (Matt. 28:19)

A young Russian priest,

inspired by the Lord’s call to preach the Gospel to all nations , traveled to

one of the far corners of the earth, to the band of the Rising Sun. He was to

become known as one of the greatest missionaries of recent times and the “Enlightener

of Japan”-Blessed Nicholas Kassatkin.

This righteous hierarch

was born in l835 to the family of a poor deacon in the provincial village

Beryoza of Smolensk. His pa rents, Deacon Dimitri and Matushka Xenia, were

blessed with four children, Gabriel, Olga, Basil and the future great

missionary to Japan who was given the name of John at baptism. When john was

still very young his elder brother Gabriel died and not long after- wards, his

mother also departed this life at the age of 35. His father worked hard to

preserve his little family and instructed his children in piety and service to

the Lord. As little john was the eldest of the two remaining boys, it is only

natural that his father paid special attention to the cultivation of virtue and

love of God in this child. He also taught him secular subjects. Among other

things, he told him about the far off land of Japan; about how highly civilized

and polite its people were. This struck a responsive chord in the heart of the

youth who soon developed a great sense of love and respect for the Japanese

people. He himself grew up to be a highly refined and dignified personality

with a determined will.

When john was old enough,

he was sent to the local elementary school, and upon completion, he entered a

seminary in Belinski. After graduating from the seminary near the top of his

class , he was sent to the Theological Academy in Petersburg from which he

graduated in 1361, Through all these years he never lost his love for the

Japanese.

It was during this time

that Japan, after several hundred years of isolationism, once again opened its

doors to foreign traders and diplomats. For the young seminarian this signaled

an opportunity to evangelize the Far Fast. When a Russian embassy was

established in. Hakodate, a port in northern Japan, and there arose a need for

a priest to serve the diplomatic corps. John enthusiastically answered the

call.

Immediately upon

graduating from the academy, he was tonsured and given the name of Nicholas. He

was soon ordained and the same year, at the age of 26, this young priest- monk

set out upon the arduous journey across Siberia-alone. Sometimes he traveled on

foot, sometimes by coach and lastly, by ship. Upon his arrival to Japan, Fr.

Nicholas wrote back to his superiors in St. Petersburg that he was impressed by

the highly civilized, polite, and refined character of the Japanese people.

Yet, he could not help pitying them for they lacked the one good thing-faith in

Jesus Christ the Saviour of mankind.

Unfortunately, the young missionary was not very warmly received either by the

Russiansin Hakodate, nor by the Japanese who, because of the nation’s previous

isolationism, were not well disposed to hear the Gospel. The situation was

discouraging. However, on September 9, 1861, he received a visit from

Archbishop Innocent, Apostle to America, who rebuked him for his waning

enthusiasm and advised him to study the Japanese language. Thus, his missionary

zeal was rekindled and Father Nicholas began to apply himself in earnest to the

study of Japanese. He studied diligently with a private tutor and also visited

the Buddhist temples to listen to the sermons and study the vocabulary

necessary to preach about virtues. His teacher was filled with admiration for

his pupil’s patience and ability to withstand hardships and proudly introduced

Father Nicholas to many important people.

I will give you a mouth

and wisdom which all your adversaries shall not be able to gainsay nor resist

(Luke 21:15)

During the time he was

studying the language, Father Nicholas began his preaching. One evening, as he

was sitting in his study, a samurai (Japanese war-lord) burst into the room

brandishing a sword and threatened his life if he did not stop preaching and

“corurupting” the local people. Humbly, the gentle Father Nicholas agreed to

die-if the man would listen to what he was studying. Out of customary Japanese

politeness, the samurai laid down his sword and agreed to listen. Father

Nicholas began to tell his would-be- assassin about the creation of the

universe by God, about His will for man and about how Christ came for man’s

salvation. The war- lord, Takuma Sawabe, became so engrossed in what Father

Nicholas was explaining, that he gave no more thought to his original murderous

intent and, in S t e a d, returned time and again to listen to the words of

life and wisdom which flowed so sweetly from the lips of the zealous

missionary. This Japanese samurai became the first man to be baptized by Father

Nicholas and fourteen years later, when be was ordained to the priesthood, he

became the first Japanese Orthodox priest- Father Paul Sawabe.

Within seven years,

Father Nicholas had mastered reading and writing Japanese sufficiently to begin

his translation work. As much as he is admired by the Japanese people for his

gift as a preacher and evangelizer and as a merciful and 10 v i n g pastor,

Blessed Nicholas’ greatest talent is universally recognized as his ability to

translate. Besides all of the other works for which he is knownthe righteous

hierarch must be ac claimed for the vast quantities of material which he

translated; he translated all of the Scriptures and all of the major services

and prayers with the exception only of the Synax- anon and Typicon. He did not,

however, hide himself in a closet to translate. This great lover of souls

applied himself equally diligently to preaching instructing and pastoral care

for his people. One of the first things he did as soon as he had begun to

gather a flock, was to set up a carefully organized system of catechism. He

established some rules for catechists and sent out a network of instructors to

preach in the outlying areas. His teaching was best received in the rural

districts, where the people are closer to God’s creation, but he was not

rejected in the urban areas either; by the time he reposed there were churches

in almost all of the major cities in Japanincluding an immense cathedral

erected in Tokyo.

On March 30, 1381, while

he was touring Russia to collect funds for the building of this cathedral, he

was consecrated Bishop. He returned with the funds from the Russian faithful

and a beautiful set of bells donated by the Tsar. It took seven years to complete

the construction of the cathedral which was dedicated to the Holy Resurrection.

A semi nary was built on some adjacent property be longing to the cathedral.

Here Orthodox young women were also accepted for instruction. This was one of

the first public institutions of higher learning where ladies could study in

all of Japan.

The fame of this

outstanding missionary hierarch grew. The cathedral received more members and

visitors so that each Sunday when he served, Nicholai-do (the affectionate name

given in the cathedral by local residents) was filled from the front to the

back. Bishop Nicholas continued to translate, preach and baptize. By the time

of his repose on Feb. 3, 1912, more than 35,000 people had received Holy

Baptism in Japan

May Blessed Nicholas’

spirit of love and evangelism move everyone to employ his own talent, however

small, to be a living witness, to the power and glory of Holy orthodoxy

throughout the whole world!

SOURCE : https://www.roca.org/oa/volume-ii/issue-17/enlightener-of-japan-blessed-nicholas-kassatkin

St. Nicholas Kasatkin

1836-1912

Harisutosu fukkatsu!

Christ is risen! Jitsu ni fukkatsu! Indeed He is risen!

February 3, 2012

marked the centennial of the death of Archbishop Nicholas (Kasatkin) of Tokyo

who is venerated around the world as the "Enlightener of Japan" and

"Equal-to-the-Apostles". By the time of his death in 1912 St.

Nicholas left behind a church that grew from one man with one convert to over

35,000 Orthodox Christians, 32 priests, 96 churches, and 265 chapels.

St. Nicholas was born

with the name Ivan Kasatkin in the Smolensk province of Russia. His mother died

when he was age five leaving his father, the parish deacon, to raise him alone.

He entered the seminary, and due to the poverty of his family he would walk the

150 miles to and from the seminary at the beginning and end of each semester.

Being a gifted and intelligent student, upon graduation in 1857, he received a

scholarship for advanced studies at the St. Petersburg Theological Academy.

With a special aptitude for the study of the Church Fathers (Patristics) and

for foreign languages he was headed for a career as a seminary professor. But

as the words of the Scripture states: Many are the plans in a man's heart, but

it is the Lord's purpose that prevails. (Proverbs 19:21) One day, Ivan saw a

notice on the seminary bulletin board requesting applications from students

interested in working at the Russian consulate in Japan. Initially the rector

of the Academy, Bishop Nektary, was opposed to sending Ivan to Japan feeling

that he would be wasting his academic talents in such a far off, pagan land.

Finally, after much reluctance on his part and on the part of the Holy Synod,

Ivan received permission to leave for Japan. First he was professed as a monk,

taking the name of Nicholas, then ordained as a deacon and priest in June,

1860.

Father Nicholas left for

his new assignment in Hakodate, Japan the next month. Unable to reach Japan

before winter set in, he was forced to spend the winter in city of Nikolaevsk

in the Russian Far East. While this delay seemed at first to be a waste of

time, the words of Proverbs 19 once again proved true in the life of the young

priest. While in Nikolaevsk he was able to meet and spend time with Archbishop

Innocent (Veniaminov) the great missionary to Alaska (now St. Innocent, Apostle

of America). With decades of missionary experience behind him, St. Innocent

advised Father Nicholas to first learn the Japanese language, begin translating

the Scriptures and not be tempted by setbacks and disappointments. St. Innocent

even sewed a new cassock for the priest and gave him the bronze cross he had

been wearing.

After a year of

traveling, Father Nicholas arrived in Japan in 1861 and expected flocks of people

gather to hear him preach the Gospel. He later wrote:

I was young and not

devoid of imagination, which painted a picture of crowds of listeners then

followers of the word of God coming from all directions. Imagine my

disappointment when I arrived in Japan only to be greeted by the exact opposite

of what I had dreamed.

The Mission Begins

The Japanese regarded

these foreigners with suspicion and mostly ignored them. In fact the preaching

of Christianity was forbidden by law and converts were threatened with death.

The new missionary resigned himself to simply serving the small Russian

community at the Russian embassy and reading the books in their library. It was

only another encounter with the saintly Archbishop Innocent (Veniaminov) that

changed the direction of Father Nicholas' life. Traveling through Japan, he

stopped to see the young priest. St. Innocent counseled him to put away the

library books he was reading and to begin a serious study of the Japanese

language. After seven years of language study, Father Nicholas felt prepared to

begin preaching the Gospel to the Japanese people. A samurai Shinto priest by

the name of Takuma Sawabe came to Father Nicholas one night with the intention

of forcing him to leave the country or killing him.

We must kill all you

foreigners. Your preaching brings evil and harm to Japan. You came to spy on

our country. I would sooner kill you than permit preaching.

Father Nicholas persuaded

him to listen to what he had to say before killing him. Takuma heard the

message of God, sin, the soul and eternal life. He was so moved that he

received baptism in 1868 along with two of his friends Sakai and Urano. The

Orthodox Church in Japan had begun!

The new converts faced

danger from the hostile government and were forced to go into hiding to save

their lives. Father Nicholas supplied them with Orthodox books and sent them

off across the country with little hope that they would be able to spread the

Faith. He wrote:

The goal of their

journey, besides the obvious one of saving them from danger, was to enable them

to get in touch with the currents of thought in various places, to discover the

kind of people necessary for our work, and finally, if possible, to lay the

foundation for Christian groups. But, frankly, I had little hope for their

success. As long as they remained safe it would be enough.

Despite the danger,

Father Nicholas continued to attract catechumens as did his new converts:

Takuma, Sakai and Urano. In 1869, Father Nicholas returned to Russia to report

on his efforts and the Church set up a formal Mission. By 1873 the persecution

of Christians in Japan had eased which allowed more widespread preaching and

teaching. The Orthodox mission grew rapidly. In 1873 schools were established,

in 1878 a seminary, in 1874 the first Japanese candidates were ordained priests

and deacons. The first man to be ordained a priest was his first convert,

Takuma Sawabe who became Father Paul Sawabe. By 1878 there were 4,115 Orthodox

Christians, by 1879 7,000. Because of the fast growth of the new Church, in

1880 Father Nicholas returned to Russia to be consecrated as the first bishop

of Tokyo.

Bishop Nicholas spent

much of his time in translating the Bible and the liturgical services from

Russian to Japanese. For thirty years he spent every evening from 6:00 till

10:00 on this project. By the end of his life, taking one verse at a time,

Bishop Nicholas provided the Scriptures, liturgical books, prayers, theological

texts which are still used by the Orthodox Church of Japan. Along with his translation

work, Bishop Nicholas devoted much time to visiting all of the parishes and

communities of the Church. He held discussion sessions with the parishioners,

made a point to meet with the children and performed baptisms. A major project

was the construction of Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Tokyo which was

consecrated in 1891. Today it is a tourist attraction in Tokyo and is commonly

called "Nikorai-do" or "House of Nicholas".

Bishop Nicholas lived a

simple life, living in Tokyo for forty years in two small rooms. His clothes

were patched because he washed them many times and would not throw them away.

When his assistant, Bishop Sergei, checked his rooms after his death, he found

nothing but some old underwear.

Bishop Nicholas

celebrated his last Divine Liturgy on Christmas Day, January 7, 1912 after

which he fell ill and was hospitalized. He continued his translation work from

his hospital bed and met Bishop Sergei to review a ten-year plan for the future

of the Mission. As he came to the end of his life he reflected on his life,

showing his great humility:

As I look her upon the

path I've followed in my life...and what of it, then?...Only

darkness...Everything was done by God, and I...what an

insignificance!....Nothing, nil, literally nil...And yet if a righteous man

barely attains to salvation, then where will I – a sinner – find myself? I am

deserving of the worst place in the abyss.

He fell asleep in the

Lord on February 16, 1912 and was buried following a massive funeral sung

entirely in Japanese by a 200 member student choir. He was glorified as the

first saint of Japan in 1970.

Tropar (Tone 4)

O holy Saint Nicholas,

the Enlightener of Japan

You share the dignity and the throne of the Apostles;

You are a wise and faithful servant of Christ,

A temple chosen by the Divine Spirit,

A vessel overflowing with the love of Christ.

O hierarch equal to the Apostles,

Pray to the life-creating Trinity

For all your flock and for the whole world.

His Significance

Upon arriving in Japan,

St. Nicholas was initially satisfied with serving "his people", that

is, the small Russian community in Japan. This has been the problem with

Orthodox Christians in America: we have limited the mission of our Church to

serve our people. We do welcome others into our churches but we exist primarily

to serve the religious needs of our people. We have neglected the final command

of Jesus: Go therefore and make disciples of all nations....(Matthew

28:19) There are people all around us who are yearning for a meaning in life

which only Jesus can provide. There are people in our communities who are open

to a Christian Church that was established by the Lord Jesus Himself and not

some human reformer. There are people looking for the preaching and teaching of

the Gospel that is unchanged from the time of the Apostles. While the steps

that a parish can undertake to begin outreach work is beyond this short

article, there are several simple steps every parish can and must take:

Are the times of services

clearly listed on the outside of your church with a welcome sign to all? Is

your parish visible on the internet with a website that is regularly updated?

Are visitors warmly welcomed to your parish and escorted to the social hour

afterwards? (From my experience in several parishes, this often does not

happen.) Are there booklets and brochures on the Orthodox Faith available in

the vestibule and/or hall? Do we offer avenues for spiritual growth such as

regular Bible Studies or other small groups?

May the life and example

of St. Nicholas of Japan inspire us to move beyond the comfort of serving our

people!

- Father Edward Pehanich

SOURCE : https://www.acrod.org/orthodox-christianity/articles/saints/st-nicholas-of-japan

St. Nicholas, Equal of

the Apostles and Archbishop of Japan

Commemorated on February

16

O holy saint Nicholas

The enlightener of Japan,

You share a dignity and the throne of the Apostles;

You are a wise and faithful servant of Christ,

A temple chosen by the Divine Spirit,

A vessel overflowing with the love of Christ.

O hierarch equal to the Apostles,

Pray to the Life-Creating Trinity

For all your flock and for the whole world.

--Troparion, Tone 4

Saint Nicholas,

Enlightener of Japan, was born Ivan Dimitrievich Kasatkin on August 1, 1836 in

the village of Berezovsk, Belsk district, Smolensk diocese, where his father

served as deacon. At the age of five he lost his mother. He completed the Belsk

religious school, and afterwards the Smolensk Theological Seminary. In 1857

Ivan Kasatkin entered the Saint Peterburg Theological Academy. On June 24,

1860, in the academy temple of the Twelve Apostles, Bishop Nectarius tonsured

him with the name Nicholas.

On June 29, the Feast of

the foremost Apostles Peter and Paul, the monk Nicholas was ordained deacon.

The next day, on the altar feast of the academy church, he was ordained to the

holy priesthood. Later, at his request, Father Nicholas was assigned to Japan

as head of the consular church in the city of Hakodate.

At first, the preaching

of the Gospel in Japan seemed completely impossible. In Father Nicholas’s own

words: “the Japanese of the time looked upon foreigners as beasts, and on

Christianity as a villainous sect, to which only villains and sorcerers could

belong.” He spent eight years in studying the country, the language, manners

and customs of the people among whom he would preach.

In 1868, the flock of

Father Nicholas numbered about twenty Japanese. At the end of 1869 Hieromonk

Nicholas reported in person to the Synod in Peterburg about his work. A

decision was made, on January 14, 1870, to form a special Russian Spiritual

Mission for preaching the Word of God among the pagan Japanese. Father Nicholas

was elevated to the rank of archimandrite and appointed as head of this

Mission.

Returning to Japan after

two years in Russia, he transferred some of the responsibility for the Hakodate

flock to Hieromonk Anatolius, and began his missionary work in Tokyo. In 1871

there was a persecution of Christians in Hakodate. Many were arrested (among

them, the first Japanese Orthodox priest Paul Sawabe). Only in 1873 did the

persecution abate somewhat, and the free preaching of Christianity became

possible.

In this year

Archimandrite Nicholas began the construction of a stone building in Tokyo

which housed a church, a school for fifty men, and later a religious school,

which became a seminary in 1878. In 1874, Bishop Paul of Kamchatka arrived in

Tokyo to ordain as priests several Japanese candidates recommended by

Archimandrite Nicholas. At the Tokyo Mission, there were four schools: for

catechists, for women, for church servers, and a seminary. At Hakodate there

were two separate schools for boys and girls.

In the second half of

1877, the Mission began regular publication of the journal “Church Herald.” By

the year 1878 there already 4115 Christians in Japan, and there were a number

of Christian communities. Church services and classes in Japanese, the

publication of religious and moral books permitted the Mission to attain such

results in a short time. Archimandrite Nicholas petitioned the Holy Synod in

December of 1878 to provide a bishop for Japan.

Archimandrite Nicholas

was consecrated bishop on March 30, 1880 in the Trinity Cathedral of Alexander

Nevsky Lavra. Returning to Japan, he resumed his apostolic work with increased

fervor. He completed construction on the Cathedral of the Resurrection of

Christ in Tokyo, he translated the service books, and compiled a special

Orthodox theological dictionary in the Japanese language.

Great hardship befell the

saint and his flock at the time of the Russo-Japanese War. For his ascetic

labor during these difficult years, he was elevated to the rank of Archbishop.

In 1911, half a century

had passed since the young hieromonk Nicholas had first set foot on Japanese

soil. At that time there were 33,017 Christians in 266 communities of the

Japanese Orthodox Church, including 1 Archbishop, 1 bishop, 35 priests, 6 deacons,

14 singing instructors, and 116 catechists.

On February 3, 1912,

Archbishop Nicholas departed peacefully to the Lord at the age of seventy-six.

The Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church glorified him on April 10, 1970,

since the saint had long been honored in Japan as a righteous man, and a

prayerful intercessor before the Lord.

SOURCE : https://www.orthodoxtacoma.com/stnicholasofjapan

St. Nicholas, equal to the Apostles and enlightener of Japan

San Nicola del Giappone Arcivescovo, isapostolo

Berjozovskij, Russia, 1

agosto 1836 - Tokyo, Giappone, 12 febbraio 1912

Nicola, al secolo Ivan

Kasatkin, fu monaco e teologo russo. Nel 1861 si trasferì in Giappone dove

fondò la Chiesa ortodossa giapponese; a lui si deve anche la fondazione di

circa 250 chiese. Nel 1970 la Chiesa Ortodossa Russa lo ha canonizzato e

dichiarato “isapostolo”, cioè uguale agli apostoli, per la sua opera

missionaria svolta in terra Giapponese.

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/93805

Maria Junko MATSUSHIMA, ST.

NIKOLAI of JAPAN and the Japanese Church Singing : https://www.orthodox-jp.com/maria/Nikolai-JAPAN.htm