Vitrail d'Émile Thibaud représentant saint Sidoine Apollinaire, église Saint-Sidoine d'Aydat, Puy-de-Dôme, France.

Saint

Sidoine Apollinaire

Ecrivain,

évêque de Clermont (+ 486)

ou Caius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius.

Évêque de Clermont. Il est le dernier écrivain romain classique. Né à Lyon, il avait une statue sur le Forum de Rome dont il fut le préfet. Il était également le poète officiel de la cour impériale. Il connut huit empereurs, mais aucun ne l'entraîna dans sa disgrâce car il savait s'engager et se dégager. Après l'assassinat de l'empereur Majorien, il se retire prudemment dans son domaine d'Auvergne avec sa femme et ses deux fils, chassant pêchant, écrivant des poèmes. Ce furent les cinq plus belles années de sa vie. Mais tout changea quand les Wisigoths se ruèrent sur Clermont dont il était devenu à la fois gouverneur et évêque. Le siège dura quatre ans et, lui, le raffiné, dut manger des chats et ensuite s'entendre "avec ces géants grossiers dont l'haleine pue l'ail et l'oignon des ragoûts qu'ils mangent dès le matin." Il est un pasteur exemplaire, donne son mobilier que sa femme rachète sur le marché, ce qui permet à saint Sidoine de les donner à nouveau. Les souffrances et la tristesse le font mourir prématurément.

À Clermont en Auvergne, vers 479, saint Sidoine Apollinaire, évêque. De préfet

de la ville de Rome, il fut ordonné évêque des Arvernes. D'une grande culture

humaine et sacrée, remarquable par sa force d'âme, il s'opposa à la férocité

des barbares en père catholique et docteur éclairé.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1716/Saint-Sidoine-Apollinaire.html

Il

y a quinze siècles, l’épopée de saint Sidoine Apollinaire

15 JANVIER, 2021

PROVENANCE: FSSPX.NEWS

L’année 2021 voit le

1550e anniversaire de l’accession de saint Sidoine Apollinaire au siège épiscopal

de Clermont-Ferrand, l’un des plus importants dans la Gaule d’alors.

FSSPX.Actualités revient sur cette grande figure épiscopale, ultime témoin du

monde gallo-romain qui devait bientôt disparaître sous les coups des invasions

barbares.

Caïus Sollius Modestus

Apollinarius Sidonius naît à Lyon, alors capitale des Gaules, en 431 ou 432. Il

appartient à l’une des familles les plus importantes du pays : son

grand-père avait été préfet du prétoire de Gaule sous le règne de Théodose, et

c’est par la conversion de cet aïeul que le christianisme est entré dans la

famille. Sous l’empereur Valentinien III, son père avait été revêtu de la même

dignité. Le plus brillant avenir semblait donc réservé à Sidoine.

Après avoir achevé des

études aussi complètes que possible, celui-ci épouse en effet, vers 452 une

jeune fille originaire d’Auvergne, Papianilla, dont le père – Flavius Eparchius

Avitus – devait être, quelques années plus tard, élu empereur par les députés

de la noblesse gauloise réunis à Beaucaire.

Le 1er janvier 456, selon

la coutume, Sidoine est chargé de prononcer devant le Sénat romain le

traditionnel panégyrique de son-beau père : ce qu’il fit avec succès.

Las ! Peu de temps après, l’empereur est renversé, mais Sidoine rentre

dans les grâces de son successeur, dont il prononcera aussi le panégyrique.

En 468, son éloquence lui

vaut d’être nommé préfet de Rome, puis, à la sortie de sa charge, patrice. Le

futur saint espérait jouir en paix des années qui lui restaient à vivre

lorsque, dans des conditions mal connues, il se trouve propulsé en 471 sur le

siège épiscopal de Clermont, alors vacant.

Rien ne l’a préparé à

l’exercice de ces hautes fonctions, mais dès qu’il est élu, Sidoine Apollinaire

a le souci de se rendre digne de la confiance de son peuple et de ses

collègues, et de se montrer à la hauteur des circonstances particulièrement

difficiles dans lesquelles son ministère devait s’exercer.

En effet, dès 474, les

nuages s’amoncellent sur la cité des Arvernes : les Wisigoths conduits par

l’hérétique arien Euric envahissent la région. Sidoine doit organiser lui-même

la résistance. Mais Clermont tombe bientôt, et l’évêque est emprisonné dans la

forteresse de Livia, près de Carcassonne.

Rendu à la liberté,

Sidoine Apollinaire retrouve son siège épiscopal sur lequel il mourra en paix,

vers 487 ou 489.

Il y a eu deux hommes

dans Sidoine Apollinaire : le patricien gallo-romain et l’évêque. Sa vie,

se partage en deux phases bien distinctes. La première, toute mondaine, est

absorbée par la légitime ambition que pouvait concevoir un homme de son rang et

de sa naissance.

La seconde nous présente

un évêque, dans toute l’acception de ce mot : un pasteur vigilant de son

troupeau, dévoué aux soins de ses intérêts moraux et matériels, préoccupé de la

multitude d’affaires qui s’imposaient à un évêque des Gaules, à la fin du Ve

siècle, dans le désarroi général de la société.

Mais, à côté de l’évêque,

nous trouvons aussi le patriote gallo-romain, profondément attaché à tout ce

que comprenait de gloire, de traditions et de souvenirs ce grand nom de Rome.

Les derniers efforts de

patriotisme romain, c’est Sidoine qui les a faits, preuve remarquable de cette

unité profonde dont Rome avait empreint les nations soumises à son

empire ; les dernières paroles éloquentes, inspirées de ce patriotisme,

c’est l’évêque de Clermont qui les a prononcées. Et il est remarquable que la

terre gauloise qui lutta avec tant d’énergie contre les légions de César ait

été aussi la dernière à résister, au nom de Rome, à l’invasion et à la conquête

des barbares ariens.

(Sources :

Dictionnaire de théologie catholique/Eugène Baret : préface aux œuvres de

Sidoine Apollinaire – FSSPX.Actualités)

Sidoine

Apollinaire

Sidoine

Apollinaire (Caius Sollius Apollinaris Sidonius dit). - Descendant

d'une des plus nobles familles de la Gaule, né à Lyon ou à Clermont-Ferrand en

430; son grand-père et son père étaient chrétiens; il fut lui aussi, élevé dans

la religion chrétienne

Sidoine composa, en 456,

à la gloire de son beau-père un panégyrique en vers qui nous est resté

(Panegyricus Avito Auguto socero dictus, carmen VII). La même année, Avitus fut renversé par Ricimer et Majorien, contre lesquels

Sidoine Apollinaire lutta deux ans avec la noblesse gauloise. Il finit par se

soumettre, en 458, et s'empressa, pour rentrer en grâce auprès des vainqueurs,

de faire le panégyrique

Quatre ans plus tard, en

472, il est élu évêque de la ville des Arvernes,

aujourd'hui Clermont-Ferrand. Ce n'est pas qu'il ait la science théologique ou

l'esprit ecclésiastique; mais l'épiscopat, à Clermont, avait une grande

influence politique et pouvait séduire un ambitieux. En effet, le successeur

de Théodoric II,

le roi Euric, menaçait l'Auvergne

Le rôle de Sidoine

Apollinaire est aussi considérable au point de vue littéraire qu'au point de

vue historique et politique. Il a laissé neuf livres de lettres où se trouvent

de nombreux morceaux de poésie; il se vante lui-même d'avoir imité Pline le Jeune et

Symmaque. Ces lettres affectées, prétentieuses, gonflées de métaphores, nous

révèlent le caractère de cet évêque, bonhomme, vaniteux et au fond paresseux et

ami des plaisirs. D'ailleurs, comme les poèmes, la correspondance de Sidoine

Apollinaire est très utile à l'histoire du Ve siècle. Augustin Thierry en a

usé plus d'une fois. Les poèmes de Sidoine, au nombre de vingt-quatre

(hexamètres, distiques élégiaques

SOURCE : https://www.cosmovisions.com/Sidoine.htm

Sidoine

Apollinaire, un écrivain gallo-romain devenu évêque et saint

Par Le

Progrès - 28 déc. 2013 à 22:35 -

Sidoine Apollinaire,

écrire, raconter, flatter et prier.

S’il naît à Lugdunum, le

Lyon de l’époque antique, c’est dans une famille de notables gallo-romains et

chrétiens, où l’on est par tradition un haut fonctionnaire de la cité, de père

en fils. Le jeune Sidoine y ajoute un goût marqué pour l’écriture, la

littérature et la poésie, épousant en 452 une jeune fille de sa caste,

appartenant à l’une des familles les plus influentes de la Gaule romaine.

Au sein des factions, des

intrigues et des coups d’état qui scandent l’Empire romain déclinant, son

beau-père Avitus devient même empereur, confiant à son gendre un poste de choix

lié à la plume éloquente de ce dernier. Pas pour longtemps : il est prestement

renversé, mais son remplaçant Majorien conserve le gendre et sa fameuse plume,

prompte à flatter le nouveau maître de Rome.

En prison pendant deux

ans

Pas pour longtemps non

plus : il est assassiné, mais un de ses successeurs, Anthémius rejouera le même

scénario, rappellera dans la capitale impériale le Lyonnais et sa plume aussi

brillante que flatteuse, lui confiant même un poste politique d’importance.

Pour peu de temps : au milieu des intrigues et des famines qui frappent la Rome

décadente, Sidoine regagne prestement sa Gaule natale.

Là, continuant sa

production littéraire et poétique, il est élu évêque de Clermont, aux

prérogatives touchant à la fois les domaines religieux, politiques et

administratifs. Ainsi, pendant quatre ans, il assure la défense de la cité

contre les armées du roi wisigoth Euric.

En 475, la ville tombe et

Sidoine se retrouve en prison pendant deux ans à Carcassonne, ne retrouvant la

liberté qu’au prix de quelques textes louangeurs chantant les mérites du

nouveau maître. Après quoi il quitte le tumulte et meurt une dizaine d’années

plus tard, devenu par la suite un saint de l’Église catholique, fêté le 21

août.

SidoineApollinaire 430

environ : naissance à Lyon (Lugdunum). 468 : préfet de

Rome. 470 environ : retour en Gaule. 471 : évêque de

Clermont. 486 : décès à Clermont.

Sidoine

Apollinaire vers 430 - 487

Qui étaient les gaulois ?

Sidoine Apollinaire

Gallo-Romain né à Lyon, fils

et petit-fils de préfets des Gaules, poète et historien, personnage politique

et évêque, Sidoine Apollinaire est un des écrivains qui nous

renseignent le mieux sur la Gaule du milieu du Vème siècle, sur les rapports

entre Gallo-Romains, Wisigoths et Francs.

Appartenant à une riche

famille de la noblesse sénatoriale, il joue d'abord un rôle politique à Rome.

Marié à la fille de l'empereur Avitus, puis préfet de Rome en 468 au temps de

l'empereur Anthemios, il part ensuite pour l'Auvergne afin d'affermir l'autorité

romaine dans cette région, pôle de résistance à la pénétration barbare.

C'est alors, vers 470,

qu'il est élu évêque de Clermont per saltum, c'est-à-dire sans être encore

prêtre, mais il est aussitôt ordonné et sacré. Sa vie familiale laïque cesse.

Cependant, la pression

wisigothique s'accentue et quand l'empereur Julius Nepos (473-475), aux

abois, donne aux Wisigoths le droit de s'installer en Auvergne comme

ils le sont déjà de la Loire aux Pyrénées et dans la péninsule Ibérique, Sidoine

Apollinaire est de ceux qui protestent. En vain.

Ils arrivent à Clermont.

L'évêque ayant refusé de fuir, il est arrêté et emprisonné près de Carcassonne.

Mais deux ans plus tard, c'est-à-dire un an après la déposition de Romulus

Augustule, le dernier empereur de Rome (476), il se rallie au roi

des Wisigoths, Euric, demande son pardon et l'obtient.

Ni théologien ni

particulièrement dévot, mais esprit généreux, excellent administrateur, ayant

une claire intelligence politique et un incontestable talent littéraire, il est

une des plus belles figures du monde impérial romain en train de s'effondrer.

C'est lui qui a donné

des Francs la plus exacte description dont on dispose :

"Leurs cheveux roux

sont ramenés du sommet de la tête vers le front, laissant la nuque à découvert

; leurs yeux sont verdâtres et humides, leur visage est rasé avec une maigre

moustache. Des vêtements collants serrent les membres de ces guerriers de

haute stature et laissent à nu leurs jarrets. C'est un jeu pour eux de lancer

au loin leur francisque, sûrs du coup qu'ils portent, de faire tourner leur

bouclier et de sauter d'un bond sur l'ennemi, devançant le javelot. Dès

l'enfance, la guerre est leur passion".

En d'autres pages, il

déplore la décadence du latin, écrivant à un ami : "Toute la pourpre du

noble langage perd son éclat à cause de l'incurie du vulgaire. La multitude des

paresseux est tellement croissante que si nous ne travaillons pas à préserver

la pureté de la langue latine de la rouille des barbarismes populaires, nous ne

tarderons pas à déplorer sa disparition..."

Mort à Clermont vers 487,

il a laissé des poèmes et neuf livres de lettres écritent en vers.

SOURCE : http://www.alex-bernardini.fr/histoire/Sidoine-Apollinaire.php

The

beginning of Sidonius’ letters in the manuscript Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms.

lat. fol. 591, fol. 1r.

Der

Anfang der Briefe des Sidonius in der Handschrift Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms.

lat. fol. 591, fol. 1r.

Also

known as

Caius Sollius Apollinaris

Sidonius

Sidonio Apollinare

Profile

Born to the imperial

Roman nobility, son of Apollinaris, Prefect of Gaul. Soldier. Married to

Papianilla, the daughter of Emperor Avitus, c.452. Father of

Apollinaris. Arrested for

political reasons in 457,

but was well treated, and after release he eventually rose through the ranks of

the new regime. Urban Prefect of Rome in 468 and 469.

Roman Patrician. Roman Senator. Reluctant bishop of Clermont, France,

chosen more for political than theological reasons. Imprisoned when

the Goths under Alaric took Clermont in 474;

Sidonius had helped defend his city against the invaders. He was later released

and returned to his see where

he served the rest of his life. Noted writer and poet;

his poetry in

particular helped advance his political career. Known for giving of his great

wealth to the poor and

his support of monasteries.

Born

c.423 in

Lugdunum, Gaul (modern Lyon, France)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Introduction to the Letters, by O M Dalton

images

e-books

Letters

of Sidonius, volume 1

Letters

of Sidonius, volume 2

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

MLA

Citation

“Saint Sidonius Apollinaris“. CatholicSaints.Info.

27 January 2022. Web. 20 August 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-sidonius-apollinaris/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-sidonius-apollinaris/

Sidonius Apollinaris

(CAIUS SOLLIUS MODESTUS APOLLINARIS SIDONIUS).

Christian author

and Bishop of Clermont, b. at Lyons, 5 November, about

430; d. at Clermont,

about August, 480. He was of noble descent, his father and

grandfather being Christians and

prefects of the pretorium of the Gauls. About 452 he married Papianilla,

daughter of Avitus, who was proclaimed emperor at the end of 455, and who set

up in the Forum of Trajan a statue of his

son-in-law. Sidonius wrote a panegyric in honor of his father who had

become consul on 1 Jan., 456. A year had elapsed before Avitus was overthrown

by Ricimer and Majorian. Sidonius at first resisted, then yielded and wrote a

second panegyric on the occasion of Majorian's journey to Lyons (458). After

the fall of Majorian, Sidonius supported Theodoric II, King of the Visigoths, and after

Theodoric's assassination hoped to see the empire arise anew during the

consulate of Anthemius. He went to Rome, where he eulogized

the second consulate of Anthemius (1 Jan., 468) in a panegyric, and became

prefect of the city. About 470 he returned to Gaul, where contrary to

his wishes he was elected Bishop of the

Arveni (Clermont in Auvergne). He had been chosen as the only one capable of

maintaining the Roman power against the attacks of Euric, Theodoric's

successor. With the general Ecdicius, he resisted the barbarian army up to the

time when Clermont fell, abandoned by Rome (474). He was

for some time a prisoner of

Euric, and was later exposed to the attacks of two priests of

his diocese. He

finally returned to Clermont,

where he died (Epist., IX, xii).

His works form two

groups, the "Carmina" and the "Epistulae". The poems are

the three panegyrics with their appendixes; two epithalamia; an acknowledgment

to Faustus of Reji (now

Riez), a eulogy of Narbonne, or rather, of two citizens of Narbonne; a

description of the castle (burgas) of Leontius, etc. The letters have been

divided into nine books, the approximate dates of which are: I, 469; II, 472;

V-VII, 474-475; IX, 479. Although written in prose, these letters contain

several metrical pieces. After his conversion to Christianity, Sidonius

ceased to write profane poetry. The poems of Sidonius are written in a fairly

pure latinity. The prosody is correct, but the frequent alliterations and the

use of short verses in lengthy compositions betray the poet of a decadent

period. The excessive use of mythological and allegorical terms and the

elaboration of details make the reading of these works tiresome. The sources of

his inspiration are usually Statius and Claudian. His defects are atoned for by

powerful descriptions (sketches of barbarian races, landscapes, details of

court intrigues) noticeable particularly in his letters, in the composition of

which he took as models Symmachus and Pliny the Younger. Most of them are

genuine letters, only somewhat retouched before their insertion in the

collection. They abound more in mannerisms than the poems and contain also many

archaic words and expressions borrowed from every period of the Latin language;

he is very diffuse and runs to antithesis and plays upon words. He foreshadows

the artificial diction of the "Hisperica Tamina", only the artistic

skill of the painter and

the story-teller makes up for these defects. These letters exhibit a highly

colored and unique picture of the times. Sidonius wished to unite the service

of Christ and that of the Empire. He is the last representative of the ancient

culture in Gaul.

By his works as well as by his career, he strove to perpetuate it under the

aegis of Rome;

eventually he had to be content with saving its last vestiges under a barbarian

prince.

Sources

The writings of Sidonius

were edited by SIRMOND (Paris, 1652); for new editions see LUETJOHANN in Mon. Ger. Hist.: Auct. antiq., VIII

(Berlin, 1887); MOHR in Bibliotheca

Teubneriana (Leipsig). For an exhaustive bibliography see CHEVALIER, Répertoire; IDEM, Bio-bibl., s.v.; ROGER, L'enseignement

des lettres classiques d'Ansone à Alcuin (Paris, 1905), 60-88.

Lejay,

Paul. "Sidonius Apollinaris." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1912. 20 Aug. 2022 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13778a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Joseph E. O'Connor.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1912. Remy Lafort, D.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13778a.htm

Book of Saints

– Sidonius Apollinaris

Article

(Saint) Bishop (August

23) (5th

century) One of the most notable personages of the Age in which he lived,

and distinguished both as an orator and as a poet. He began life as a prominent

public man, was married and had children. The Invasion of the Barbarians, which

led to the collapse of the Roman Empire, had commenced; and Sidonius, called

to Rome,

was appointed Prefect of the City. But the people of Gaul soon reclaimed him

and obtained his recall to his own country. Separating from his wife with her

consent, he was made Bishop of

Clermont in Auvergne. He proved himself a model Bishop, not only by his zeal

for religion, but also by his prudence and skill in safeguarding his flock in

the troubles of the times. His dealings with Alaric, the chief of the Goths,

though they irritated the Barbarians, ultimately resulted in the escape of his

people from destruction. Saint Sidonius died in

A.D. 482,

and has left many letters and poems. Like so many of his contemporaries, he

could not bring himself to believe that the Roman Empire was to pass away and

to be succeeded by a new Europe, peopled by conflicting nations. This makes his

correspondence specially interesting.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Sidonius Apollinaris”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

20 August 2016. Web. 20 August 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-sidonius-apollinaris/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-sidonius-apollinaris/

August

23

St.

Apollinaris Sidonius, Bishop of Clermont, Confessor

CAIUS SOLLIUS APOLLINARIS SIDONIUS was

born at Lyons about the year 431, and was of one of the most noble families in

Gaul, where his father and grandfather, both named Apollinaris, had commanded

successively in quality of prefects of the prætorium. He was educated in arts

and learning under the best masters, and was one of the most celebrated orators

and poets of the age in which he lived. From his epistles, it is manifest that

he was always religious, pious, humble, affable, extremely affectionate,

beneficent, and compassionate, and no lover of the world, even whilst he lived in

it; for some time he had a command in the imperial army; and he married

Papianilla, by whom he had a son called Apollinaris, and two daughters.

Papianilla was daughter of Avitus, who after having been thrice prefect of the

prætorium in Gaul, was raised to the imperial throne at Rome in 455; but being

obliged to quit the purple after a reign of ten months, died on the road to

Auvergne. Majorian, his successor, prosecuted his relations, and coming to

Lyons, caused Sidonius to be apprehended; but admiring the constancy with which

he bore his disgrace, and becoming acquainted with his extraordinary

qualifications and virtue, restored his estates to him, and created him count.

Majorian was a good soldier, and began to curb the barbarians who laid waste

the fairest provinces of the empire, but was slain in 461, by Ricimer the Goth,

his own general, who placed the diadem upon the head of Severus. Upon this

revolution Sidonius left the court, and led a retired life in Auvergne, where

he protected his province from the Goths, and divided his time between studies

and the exercises of piety. Severus was poisoned by Ricimer after a reign of

four years, and Anthemius chosen emperor in 467, who immediately called

Sidonius again to Rome, and created him prince of the senate, patrician, and

prefect of the city. His piety and devotion suffered no prejudice in his

elevation, and amidst the distraction of his secular employments, in which he

made use of his authority only to promote the divine honour, and to render

himself the servant of others in studying to advance every one’s happiness and

comfort.

God soon called him from

these secular dignities to the government of his church. The bishopric of

Arvernum, since called Clermont, in Auvergne, falling vacant in 471, the people

of that extensive diocess, and the bishops of the whole country, who had long

regretted his absence whilst he was detained in the capital of the world,

unanimously demanded that he should be restored to them in order to fill the

episcopal chair. Sidonius was then a layman, and his wife was yet living; he

therefore urged the authority of canons against such an election, and opposed

it with all his might, till, fearing at length to resist the will of heaven, he

acquiesced; it having been customary on extraordinary occasions to dispense

with the canons which forbid laymen to be chosen bishops. He therefore and his

wife agreed to a perpetual separation; and from that moment he renounced poesy,

which till then had been his delight, to apply himself only to those studies

which were most agreeable to his ministry. He was no stranger to them whilst a

layman, and he soon became an oracle whom other bishops consulted in their

difficulties; though he was always reserved and unwilling to decide them, and

usually referred them to others, alleging that he was not capable of acting the

part of a doctor among his brethren, whose direction and science he stood

himself infinitely in need of. St. Lupus, bishop of Troyes, who had loved and

honoured him whilst he was yet wandering in the dry deserts of the world, found

his affection for him redoubled when he beheld him become a guide of souls in

the paths of religion and virtue. Upon his promotion to the episcopal dignity

he wrote him an excellent letter of congratulation and advice, in which, among

other things, he told him: 1 “It is no

longer by pomp and an equipage that you are to keep up your rank, but by the

most profound humility of heart. You are placed above others, but must consider

yourself as below the meanest and last in your flock. Be ready to kiss the feet

of those whom formerly you would not have thought worthy to sit under your

feet. You must render yourself the servant of all.” This Sidonius made the rule

of his conduct. He kept always a very frugal table, fasted every second day,

watched much, and though of a tender constitution, often seemed to carry his

penitential austerities to excess. He was frequently in want of necessaries,

because he had given all away to the poor. His love and compassion for them,

even whilst he lived in the world, was such, that he sometimes had sold all his

plate for their relief; which having been done without the knowledge of his

wife, she afterwards redeemed it.

After he was bishop, he

looked upon it as his principal duty to provide for the instruction, comfort,

and assistance of the poor. In the time of a great famine he maintained, at his

own charge, with the charitable succours which Ecdicius, his wife’s brother, put

into his hands, more than four thousand Burgundians and other strangers, who

had been driven from their own country by misery and necessity; and when the

scarcity was over he furnished them with carriages, and sent them to their

respective homes. St. Sidonius made frequent visitations of his diocess, and

performed every office of his ministry with all the care and prudence possible.

The reputation of his wisdom was so great, that being summoned to Bourges, when

that see, which was his metropolitan church, was vacant in 472, all the

prelates there assembled, with one consent, referred the election of a bishop

to him, and he nominated Simplicius, a holy pastor. 2 He says

that a bishop ought to do by humility what a monk and a penitent are obliged to

do by their profession. He gives us the following account of Maximus,

archbishop of Toulouse, whom he had before known a very rich man in the world;

that he found him in his new spiritual dignity wholly changed; his clothing,

countenance, and discourse savoured of nothing but modesty and piety; he had

short hair, and a long beard; his household-stuff was plain; he had nothing but

wooden benches, stuff curtains, a bed without feathers, and a table, without a

carpet; and the food of his family consisted of pulse more than flesh. 3 He

testifies that the annual festivals of saints were kept with great solemnity;

that on them the people flocked to the church in throngs before day; that they

lighted up a great many tapers; that the monks and clergy sung the vigils or

matins in two choirs, and that they celebrated mass about noon. 4

The city of Clermont

being besieged, in 475, by Alaric, king of the Visigoths, who then reigned in

the southern provinces of France, the zealous bishop encouraged the people to

stand upon their defence, by which he exposed himself to the rage of the

conquerers after they were masters of the place. He entreated the Arian king to

grant several articles in favour of the Catholics, which the barbarian was so

far from allowing, that he sent the holy prelate prisoner to Liviane, a castle

near Carcassone, where he suffered much. However, Alaric some time after

restored him to his see, and he continued to be the comfort and support of the

distressed Catholics in that country. He was again expelled by two factious

wicked priests, but some time after recovered the government of his church, and

died in peace in the year 482, on the 21st of August. His festival was kept

soon after his death with solemnity at Clermont, where his memory is in great

veneration. His body lay first in the old church of St. Saturninus, but was

afterwards translated into that of St. Genesius. See his works; 5 St. Gregory

of Tours, Hist. Fr., l. 11, c. 22, 24, and the life of the saint by Savaron and

F. Sirmond; also Fleury, l. 29, n. 36. Ceillier, t. 15. Rivet, Hist. Lit. t. 2,

p. 550. Gall. Chr. Nov., t. 2, p. 231.

Note 1. Spicileg. t.

5, p. 579. [back]

Note 2. L. 7, ep.

9. [back]

Note 3. L. 4, ep.

24. [back]

Note 4. L. 5, ep.

17. [back]

Note 5. Sidonius’s

works consist of nine books of letters, and of a collection of short poems upon

particular subjects, directed to his friends. His principal poems are three

panegyrics on the Emperors Avitus, Majorian, and Anthemius. He discovers a rich

poetical genius, and wrote verses readily, but his promotion to the episcopal

dignity hindered him from polishing them. His thoughts are ingenious, witty,

and curious; and his style is concise, pleasant, and lively, but sometimes too

lofty and subtle. He uses some words which show the Latin language had then

degenerated from its purity. He had a flowery imagination, and excels in his

descriptions and draughts. The learned Savaron published the works of

Apollinaris Sidonius with useful notes, in quarto, at Paris and Hanover; but

the edition of F. Sirmondus, in the year 1652, which is more ample, is enriched

with new notes so well chosen, so curious, and judicious, as to give an ample

proof of the excellency of the editor’s understanding, and the depth of his

learning. The correctness of all the works of this learned Jesuit, justify the

advice which he gave Huet; “Be not in haste,” said he, “to make your appearance

in print; revise your works at distant intervals; keep them by you, according

to the maxim of Horace and Vida, for ten years; and declare not yourself an

author before you are fifty years old.” [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume VIII: August. The Lives of the Saints. 1866

SOURCE : https://www.bartleby.com/210/8/233.html

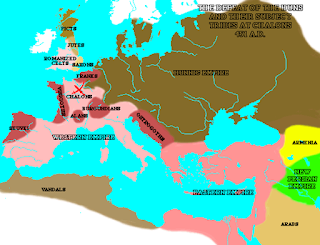

Europe

in 451

Apollinaris Sidonius (5

November c.430 - 21 August c.483)

I: General Remarks

Although a saint, a

bishop, and an important figure in a turbulent age, Sidonius is remembered

particularly because of his somewhat dubious literary talents. These were so

admired until the revival of appreciation for good Latin that some 147 letters

and twenty-four poems of his have survived. It is not a simple matter to

reconstruct an entire life from such materials, and much of what follows may

not be correct in detail. Its account of the course of events and descriptions

of some of the institutions of the Late Roman Empire are true enough, however,

and the attempt to weave the life and attitudes of Apollinaris Sidonius into

this context accords well enough with what we do know of the man and his works.

II: Youth (c. 430-456)

A: General Situation in

the Empire in the West

1: The condition of the

empire had deteriorated badly by the time of Sidonius' birth in Lyon in about

the year 430, and the situation of the western provinces deteriorated rapidly

during his youth.

a: By 430, the first

invaders of the Empire, the Vandals, had moved to Africa, the richest grain

area of the Empire, which they took and held in defiance of imperial authority.

They took to the sea and their piratical attacks soon destroyed Roman commerce

on the Western Mediterranean.

b: The Visigoths, who had

sacked Rome in 410, were settled in Aquitaine by a treaty with the imperial

government. They soon threw off their federate status and established

themselves as a separate kingdom. Always seeking to operate in a favorable

manner with the Romans, the Goths nevertheless sought to expand: into Spain,

against the Vandals and Alans left in the northwest of the peninsula, and in

every other direction against Roman provinces of the region, Tarraconensis,

Narbonnensis, and Lugdunensis -- the province of Lyon -- which stretched along

the valleys of the Rhone and Loire.

c: The Burgundians had

been allowed to settle in Savoy, along the upper Rhone, perhaps as a

counterweight to the Visigoths.

d: North of the Loire,

the rebel Bretons were poised and, the greatest Germanic force that would

emerge in the future, the Franks who were experiencing a slow but steady growth

of population that would eventually drive them to cross the lower Rhine and

establish themselves in what is now Belgium.

2: The Empire had not

responded well to this threat.

a: The Italian Provinces,

especially Rome, had been favored at the expense of the more exposed regions.

b: Rather than putting

aside personal interests, the central government had become the site of almost

continuous conspiracy and treachery. Barbarians used this factionalism to

advance their own candidates for the throne, hoping to gain advantages thereby.

c: The heavy expenses of

government; salaries, bribes, and, most particularly, defense, were met by an

extremely uneven taxation, in which the provinces paid more than Italy, and in

which the poor and the middle class bore the entire burden.

3. Despite these

conditions, the tone of Sidonius' letters suggests that the class to which he

belonged were hardly aware of the direction in which Roman affairs were moving.

B: Birth and

education

1: Sidonius was born in

the pleasant city of Lyon, situated on the Rhone River in what is now southern

France. His family was of the praefectorial class and was one of the more

influential of the region. His grandfather and father had both been Praefect of

the Gauls, a position at the time of real responsibility. The family had

accepted Christianity in his grandfather's time, but like most of the noble

families of the region, they had not become fanatic about it. At least they had

not yet, as some other families had already done, produced a saint.

2: When the time came,

Sidonius entered the Roman equivalent of a university located in his own city

of Lyon. For some time, the caliber of the schools of Gaul had been improving,

although those in the rest of the West were in a state of decline. Lyon was not

one of the first rank of Gallic schools, but it was respected. The emperor

Gratian (370-383) had attended the "university" of Bordeaux and had

appointed his old professor, the poet Ausonius, to the consulship in 379. This

remarkable appointment had brought Bordeaux prestige and funds, and it had

assumed a rank in Gaul not unlike that of Harvard in the United States. If

Bordeaux was the Harvard of the Western empire, Toulouse and Marseilles might be

considered the Princeton and Yale. Lyon was, then, the equivalent of a great

state university such as Michigan or the University of California at Berkeley.

The organization and

purpose of the Roman school was considerably different from the medieval or modern

concept, but education was certainly as highly regarded. The central government

endowed chairs and, more commonly, required municipalities to do so. In many

cases, the government built public lecture halls where the professors could

discourse. Normally, however, the lecture was only a part of the education. The

serious student would pay his professor a fee to work with him personally.

The school of Grammar was

the basic level, corresponding, one might suppose, to the first and second

years of a modern American university, although the student might spend more or

less time in studies at this level. In a fully-staffed institution, the school

of Grammar consisted of two divisions, Greek grammar and Latin grammar. Faculty

generally began teaching at this level, and, if they were sufficiently skilled,

might move up to the better pay and greater prestige of the school of Rhetoric.

The curriculum and

teaching methods of the schools of Grammar were more or less standardized.

There were certain great works of literature recognized as suitable for study,

some more important than others; the poets were particularly emphasized.

Homer's Iliad and Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days were

the most important works for Greek Grammar, and Virgil's Aeneid and

Cicero's orations and letters were basic to the study of Latin Grammar. The

professor would read a passage to his students, and then comment extensively

upon it, discussing its style, allusions, comparing it with similar passages in

other authors, clarifying archaic words, etc. At best such training could have

been a fine liberal education. In practice, it sometimes rose to literary

criticism, and more often sank to providing massive footnotes and glosses.

Upon completion of the

both the Greek and Latin curricula of the school of Grammar, student were

prepared to move on. Many chose to end their formal education at this point,

and, if the institution provided such, some entered the professional schools of

medicine and law. The brightest and wealthiest students, and those from the

most important families, however went on to enter the school of Rhetoric. The

school of Rhetoric was composed, like that of Grammar, into divisions of Greek

and Latin Rhetoric, and the student normally took one as a major and the other

as a minor field of study.

At the level of the

school of Rhetoric, the student was not expected simply to study past authors,

but to create. But the emphasis was upon creation in the style of the past

masters, especially extemporaneous compositions and speeches. The great

orations of the past were studied, and the students learned to speak in the

style of Cicero, with literary allusions drawn from Virgil, discussing some

episode of Homer's Iliad. Achievement was measured by style, not by

content.

This was the sort of

education that Sidonius pursued, although he did not enjoy the benefits that

would have come with a full curriculum of study. By this time, the lack of

funds, the rise of Christian thought, and other factors were leading to the

"downsizing" of the late Roman universities, and few could afford to

maintain a full faculty. Lyon appears to have dispensed with Philosophy and

Law, and did not emphasize Greek Rhetoric. Sidonius thus knew his Greek authors

reasonably well, but not to the point that he could think in Greek. His letters

and poems were solidly based on Latin models, and he attempted to demonstrate

the extent of his learning with frequent allusions and images drawn from the

Greek classics. He was not too different from others of his class in this respect.

The cultural ties that had bound the Western nobility to the Greek tradition of

scholarship were weakening, although every attempt was made to disguise that

fact.

3: What was the purpose

of this sterile and imitative talent, and why did the children of noble

families spend their youth in learning how to write and give public speeches in

a centuries-old style? Why did they memorize Greek and Latin fables and myths,

and fill their writings and speeches with obscure references and ponderous

evocations of long-dead authors? The answer was, as is often the case, that

they were educated in the skills that might gain them advancement. In the world

of fourth-century Gaul, however, there were few areas in which demanded any

real ability from the nobility. The Roman nobles had for so long attempted to

avoid the burdens of empire that there were very few areas of life in which

they could demonstrate real ability.

a: They were forbidden to

serve in the army, and, even if they had been able to do so, there would have been

little role for them to play. Military command authority was usually in the

hands of a barbarian chieftain, like Merobaudes, who led Roman armies that

consisted primarily of Germanic mercenaries.

b: The traditions of

their class forbade them to go into manufacture, their great estates were

self-sufficient and managed by trained slaves. They continued to make money,

but could do nothing with it except loan it out at interest. Since, under the

declining economic conditions of the period, loans were often note repaid. This

meant that the nobility simply gained more land. Even if their loans were

repaid, this simply provided them with more money that they could use only in

making more loans. Since families of the senatorial rank or above were tax-

exempt and their estates relieved them of having to buy anything but the most

exotic of luxuries, the wealth of the Roman nobles grew no matter what they

did. The distance between them and the mass of the Roman population increased

until they were virtually isolated within their own society.

c: The local government

was entrusted to the middle-class curiales, and senatorial scions were debarred

from these onerous functions.

d: Positions of

responsibility within the central government were in the hands of professional

bureaucrats

The nobles could simply

retire to their estates and wear themselves out with excesses, and some did.

Most, however, sought a "nobler" life. Basically they attempted to

add to the honors of their family by holding some position of prestige within

what was called the cursus honorum, something that might best be

translated as "The Ladder of Offices." Many of the old imperial

administrative offices had been preserved and the emperors had even added new

ones. These had once been offices of prestige and responsibility. Although the

responsibilities had been long since been assumed by professional civil

servants, the prestige remained, and members of the Roman nobility gained honor

of serving as figurehead administrators of these offices. The offices of

the cursus honorum formed a ladder of positions, a ladder on

increasing prestige and social status. There were numerous lower ranks, but the

three highest -- those of prefect, patrician, and consul -- were avidly

pursued, especially since the person who served a short term in one of these

higher offices earned social status that became hereditary in his family. The

young Roman, after having finished his education, would use his family

connections to enter the cursus honorum at as high a level as

possible. Once having obtained such an office he would attempt to ingratiate

himself with his superiors so that they might appoint him to another office

further up the ladder.

How did one ingratiate

himself with one's superiors? By demonstrating one's social skills. These

skills consisted primarily of culture, wit, and urbanity. Clever and polished

conversation, the ability to make and to recognize literary allusions, facility

in publicly praising one's sponsors and patrons in fashionable poetry,

personally declaimed in public, graceful manners, mastery of the art of

conversation, and other genteel accomplishments were the signs of merit that

gained one favor and advanced one's career. Certainly these were artificial and

mannered affectations, but their mastery demanded an education that only the

wealthy could afford and only the noble could value. Privileged classes often

close their ranks to outsiders in this way, as one will see with the hereditary

nobility of Medieval Europe or the nobility of Restoration London.

The term of service in

each of these offices was short, often only a year, and the average noble

reached the limit of his ability to rise in the cursus honorum relatively

early in life, often by his early thirties and then had nothing to do but to

retire to his country estate and to the company of neighbors much like himself.

He Superannuated in the prime of his life, the Roman noble devoted himself to

reading, writing, conversation, mild sports, and his gardens.

Thus the school education

of the day while, admittedly artificial, achieved three basic ends: it gave the

nobles a sense of identity and protected them from encroachment by the lower

classes; it provided them with the skills necessary to achieve success in their

terms; and it provided the best of them with a cultured mind which could

survive a lifetime of retirement years without falling into excess or simple

vegetation.

4. This was Sidonius'

education, and this was the type of life which lay before him. His first step

was to marry, and he did quite well, marrying a daughter of the family of the

Avitii, perhaps the most prestigious and wealthy family in the region. She

brought with her as a dowry, the great estate of Avitacum, which Sidonius

mentions a great deal more than he does her. After making himself at home here,

By about 455 he was ready to enter politics.

III: Entering

the Cursus Honorum (456-458)

1: The situation was

somewhat unusual when Sidonius was ready to begin public life in his

mid-twenties. In the year 451, the western provinces had been menaced by the

invasion of Attila the Hun and a large army. Attila and his forces crossed the

Rhine River, and a remarkable Roman general, Aetius (pronounced aye-EE-tee-

uhs), had been able to patch together an equally remarkable confederation to

meet them. He convinced the Germanic tribes residing in the area to join in

resistance and, under his leadership, Visigoths, Franks, Bretons, and

Burgundians joined forces with the small regular Roman army in defeating the

enemy in battle at Chalons-sur Marne. More to the point, Aetius had been

successful in enlisting the active assistance of some of the nobles resident in

the area, among them being Sidonius' father-in-law, Avitus. The results of this

co-operation were very encouraging to the West, and the Germanic leaders were

impressed with the advantages of forming a western confederation under the

leadership of Aetius. The Visigoths returned to their former status of Roman

allies, the Sueves gave the Spanish province of Carthaginensis back to imperial

administration. and the new Visigothic king, Theodoric II, began to search for

new avenues of mutual action.

It was at this point that

Aetius was murdered by enemies at the imperial court who were jealous of his

successes. The effects of this assassination in the West were quite dramatic.

Acting as if their chieftain had been killed and they were seeking vengeance

according to German custom, the Franks and Alamanni moved south and west,

occupying stretches of imperial territory and gaining control of some important

imperial arms factories. Meanwhile, the court faction that had encompassed

Aetius' death ignored the German attacks and concentrated on eliminating their

political opponents. A group of the old followers of Aetius gathered to attempt

to restore Aetius' vision of a Western Federation, by were betrayed. Many were

killed (15 March, 455), and the other nobles of the region organized to defend

their territory and their own lives. Avitus, who had survived the downfall of

both Aetius and his friends, was sent by his neighbors to the Visigothic

capital of Toulouse to enlist the assistance of the Visigoths. Meanwhile, Rome

was in turmoil. Attila had appeared before the city and had been bought off by

Pope Leo with the gift of a heavy tribute. Almost as soon as the Huns, who were

suffering from an epidemic of some sort anyway, had departed, the Vandal fleet

sailed up the Tiber River, and Vandal marines took and sacked Rome. This was

followed by a flood that destroyed many of the poor neighborhoods of the city,

and swept away many of the warehouses in which the city's food supply was

stored. Hunger was followed by the effects of the sickness the Huns had left

behind them. The Roman government, under the control of Petronius Maximus, a

usurper, had proven completely unable to protect the city or its inhabitants.

When Petronius ventured outside the imperial palace to speak to the masses,

they came carrying rocks and stoned him to death. When the news reached

Toulouse, the Westerners decided to attempt to seize imperial power and restore

the policy of Aetius. The Visigothic king Theodoric, probably hoping to gain

the power of the king-maker, recommended Avitus as emperor and promised to

support him. The Gallo-Roman senators crowned Avitus at Arles, and, in

September, he left for Rome with a strong detachment of Visigothic warriors.

His son-in-law, Sidonius,

was also a member of his train and ready for a dazzling career. He had wealth,

education, and now patronage of the highest level. On his arrival in Rome,

Sidonius did what any ambitious young man would do. He wrote a excessively

flattering poem about Avitus and read it publicly in the Roman forum. Although

it is rather pompous and obscure, everyone applauded and voted to place

Sidonius' statue in Forum of Trajan along with those of other accomplished

Romans. Sidonius was sure that he was on the path to success, and he failed to

note that the Romans applauded every imperial protege and voted to erect his

statue in the Forum of Trajan, but such projects were brought to a successful

conclusion only very rarely. Sidonius seemed not to have realized upon how

slender bases his present prestige rested.

Although Avitus was able

to take power, he was unable to solve all of Rome's problems at once, and so

was unable to hold on to that power. He fought and defeated the Vandals, but

Rome faced a famine, and there was no food to be had to alleviate conditions

until the Spring harvests would become available. Avitus may have been a bit

gullible, since he agreed that it would look better if he were to send his

Visigothic troops home, where they would no longer be an additional drain on

the city's food supply. As soon as they had left, the old faction that had

opposed Aetius stirred up a revolt among the Roman populace. Majorian, a Roman

general who had been an enemy of Aetius, took command of the rebels, and

managed to defeat and kill Avitus in October of 456. Majorian then set about

rooting the Westerners and their sympathizers out of all positions of any power

or prestige.

The Romans of Lugdunensis

did not give up easily, however, and rose in revolt against Majorian, who had

made himself the new emperor. The revolt was crushed, however, and Sidonius --

along with other Gallo-Roman nobles of the region -- retired from public life.

IV: County Gentleman

(458-467)

1: The affairs of the

West steadily declined during these years. Majorian failed in his attempts to

defeat the Vandals, losing Africa definitively, as well as Sardinia, Corsica

and the Balearics. Most of Lugdunensis, including Lyons, was turned over to the

Burgundians, and the Visigoths were allowed to take Narbonnensis Prima.

Finally, the Vandals took Sicily, the last granary of the West (468). At this

point, the Eastern emperor, Leo, intervened, and appointed Anthemius, his own

man, as emperor in the West. Matters had gone too far for imperial fortunes to

be repaired, however, and Anthemius' reign was, in retrospect, the last gasp of

the Roman Empire in the West.

2: This steady decline in

Roman fortunes seems to have had little effect upon Sidonius during these nine

years. He appears to have accepted the curtailment of his public career as an

unfortunate, but not unusual, event, and retreated to retirement at Avitacum.

His letters from this period. as well as a few incidental poems provided us an

unparalleled picture of the life of the leisured classes of the time.

The nobles lived on great

estates, of which they might own a number. The estate formed a separate world,

self-sufficient in virtually all things. Slaves did all the necessary work,

although the owner supervised building, decorating, and some of the more

refined activities such a flower gardening. The mansion formed the heart of the

estate, and embellishing its amenities and enjoying them were the profession of

the owner. Much time was spent in visiting, reading, hunting, bathing, and

generally resting. The nearest society to it that springs to mind is that of

the Ante-Bellum south pictured in MGM movies from the thirties, such as the

opening scenes from Gone With the Wind.

3: Unbeknownst to

Sidonius, who appears to have given up all political ambition, events were

moving him towards a second excursion into public life.

V: Second Attempt at

Politics (468-469)

1: The new Emperor,

Anthemius, was attempting to reconcile the West and restore some order. The

people of the district of Auvergne asked Sidonius to present a petition to

Anthemius while he was in a conciliatory mood, and Sidonius travelled to Rome

to do so.

He arrived in Rome in

time for the marriage of Anthemius' daughter and seized the opportunity to

write a poem about the event, and read it publicly. The acclaim was great and

much to Sidonius' joy, he was made Prefect of the City, only two steps away

from the golden prize of the consulship. He encountered problems, however, since

one of the major responsibilities of the Prefect was to ensure the regular

distribution of grain to the city. Of course, the Prefect had no power to do

anything about the matter, but he was praised when grain was plentiful and

condemned when it was short. With Sardinia, Sicily, and Africa in the hands of

the Vandals, the city's grain supply was no longer as assured as it once had

been. Sidonius spent the entire year in fear that something would go wrong and

that people would boo him in the theater. Even the idea of such humiliation

horrified him, and, by the end of his term, he seems to have suffered what

might best be termed a nervous breakdown. As soon as he was relieved of office,

and before his successor had been installed, he had gathered his household and

fled to his villa at Avitacum. He did not even wait for the ceremony that

raised him and his family to the Patrician status, a dignity that his service

as Prefect of the City had won him.

2: Once again, he retired

to Avitacum. This time, he should have definitely given up any ambitions. He

had broken down under the pressure of office and being placed in the public

eye, he was in his late forties, and he had accomplished enough to bring honor

to his family's name and to be remembered and honored by his descendants.

VI: Roman Bishop (c.

470-474)

1: This was not to be the

case, however. Within the year, he was called by the people of Auvergne to

become their bishop. This brings up the problem of why they would have chosen a

retired gentleman with no record of spirituality and little proof of personal

administrative ability. One must understand that different cities had different

needs, and two types of men during this period were considered as prime

candidates for the post of bishop, a post that was, to all intents and

purposes, filled by someone chosen by members of the congregation. the bishops

of the time were more like elected representatives than any other officials of

the West.

a: The superficiality of

the public educational system had led the Church to concentrate Christian

education in the monasteries, and a number of these were springing up in the

West. The major one in Lugdunensis was at Lerins, off the coast of France.

where St. Honoratus had established an institution modelled upon the monasteries

and schools of Egypt and Syria. In such places, which were usually in close and

frequent contact with Eastern centers, real philosophy was being developed and

a peculiar western version of Christianity -- the semi-Pelagian school -- was

showing great promise of revivifying Roman life.

b: On the other hand, an

ascetic thinker was not always what a given church needed. Sometimes it needed

a wealthy man to help endow it; sometimes a cultured man to impress Germanic

neighbors; sometimes a man of good birth to handle its properties honestly;

sometimes a man of position simply as a compromise candidate. Generally

speaking, since local needs were peculiar and paramount, the people of the

diocese elected their own man.

2: It is difficult to

ascertain what Sidonius' special qualifications were, but the call to serve as

bishop represented for the nobility of the time a public charge which, unlike

all others, it was impossible simply to refuse. It was possibly the only really

public obligation the senatorial class still recognized.

3: The position of

Sidonius' diocese was perilous. The Visigoths under the stern and Arian king

Euric coveted the territory and threatened it from the south, while it was cut

off from other Roman territories by the Bretons and Burgundians to the east and

north. Many of the officials of the region were in despair. Roman taxation was

heavy, and benefits were nil. Corruption was endemic, and many residents of the

district had come to the conclusion that they were simply being exploited, which

was indeed the case.

4: Bishop Sidonius and

his brother-in-law Ecdicius stiffened the resistance of the inhabitants of the

territory, and Euric finally invaded and laid seige to the city of Auvergne.

Sidonius managed supplies and morale during this difficult period, while

Ecdicius formed a body of eighteen commandos which made life hell for the

besiegers by their sudden raids and ambushes. Both Sidonius and Ecdicius showed

a strength of character that one would not have believed possible of men of

their tender upbringing and impractical background. Upon arriving at his seat

of Aurillac, already under Visigothic threat and menaced by famine, Sidonius

ordered his flock to scrape the algae and lichens from the walls of the city to

make soup, and to eat the dogs and cats instead of feeding them. Before the

matter was over, he would have his congregation dining on rat rather than

surrender to a bunch of heretical barbarians. For his part, Ecdicius and his

friends are said to have enjoyed slipping out of the city at night to cut the

throats of unwary Germans. Some of these accounts may be more than a little

romanticized, but they illustrate what the people of the time believed that

their urbane and sophisticated leaders were capable of doing. In any event, the

Visigoths, who had terrorized great expanses of the empire in the West, were

unable to dislodge the bishop and his followers.

In 474 the Visigoths

lifted the seige, and a Roman official arrived to pour praise on the defenders.

Arrangements were made for peace talks with Euric. The bishops of Arles,

Marseilles, Riez, and Aix were the Roman negotiators, and they appeased Euric

by giving him Auvergne in exchange for his promise not to attack their own

territories. It was betrayal plain and simple, but these were perilous times,

and self-preservation was the order of the day. In the year 475, Sidonius

ceased to be a Roman citizen and never seems to have recovered from the blow.

VII: Later Years

(475-483)

1: Sidonius was thrown

into a Visigothic prison as a recognition of how steadfast had been his

resistance to Euric's designs. His imprisonment seems to have been light, but

of a sort that must have been particularly painful. He was exiled to a small

villa high in the Pyrenees Mountains, where he was isolated from others of his

class and culture. Interestingly enough, this little district still exists, a

patch of land of about a mile square called Llivia, a piece of Spanish

territory completely surrounded by the lands of France. After a while, he was

simply released and allowed to go his own way. This lack of regard was perhaps

only a further punishment. Sidonius wandered to Bordeaux, where Euric was

holding his court, and being attended by many of the Gallo-Roman nobles who,

like Sidonius, now found themselves subjects of a barbarian king. After a

period of being ignored in Bordeaux, Sidonius finally returned to Avitacum. His

friends apparently feared that the shocks of recent years might drive him into

a permanent state of depression, and suggested that he occupy his time by

editing some of the best of his letters and poems. He did so, with great

pleasure, and it is to this period -- his final retirement -- that we owe the

written works which have kept his name alive.

He seemed to have paid

little attention to events in Italy, where the barbarian commander of the Roman

army, Odoacer, found himself faced with a steady increase in the price of food,

now that the peninsula could no longer relay on imports from the imperial

granaries of Sicily, North Africa, Spain, and southern France. His troops could

no longer feed themselves on the pay they were given, and salary increases were

only eaten up by inflation. In the year 476, he went to Orestes, regent for the

boy-emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and asked that each of his soldiers be given a

piece of land and a slave family to till it and produce enough food to maintain

the soldier. These lands and slaves were to be donated, naturally enough, by

the nobility who owned most of the land and slaves. Orestes flatly refused, and

Odoacer had him killed. He then brought in monks to give the eleven-year old

Romulus Augustulus the monastic tonsure. The last of the Roman emperors on the

West spent the rest of his life in a lovely monastery overlooking the Bay of

Naples. Odoacer, meanwhile had packed up the imperial regalia, the diadem,

purple cloak, and red shoes that were the official dress of a Roman emperor. He

had sent them to the emperor of the East with he message that they were no

longer needed. There was no more Roman Empire of the West.

2: Sidonius died of

unknown causes on the 21st of August, probably in the year 483. He was buried

in the church in Auvergne, and was immediately regarded as a saint by popular,

if not overly excited, acclaim. The shrine of St. Apollinaris was venerated

until the disorders of 1794, when it was destroyed by mobs inspired by the more

radical of the ideals of the French Revolution to erase from the face of France

all signs of its superstitious and monarchical past.

VIII: Some General

Observations

1: The career of Sidonius

suggests a cause for the fall of the Roman Empire which is not generally

emphasized: that the empire trained a noble class superbly well to compete in

an artificial fashion for a series of empty honors. Their education blunted

their creativity, and their energy was dissipated in meaningless pursuits. The

late Roman noble was brave and honorable; talented and dogged, as Sidonius and

Ecdicius proved during the siege of Auvergne. Such men could have saved the

empire if they had not been so finely trained to waste their time. Sidonius had

every opportunity to see the sham and waste; he lived to learn of the

deposition of the boy emperor Romulus Augustulus, the last Roman Emperor in the

West and yet seemed unable to comprehend that it was all over. His last letter

to his wife closed with the words,

... I pray in our common

name that just as we of this generation were born into prefectorian families,

and have been enabled by divine favor to elevate them to patrician rank, so

(our children) in turn may exalt the patrician to the consular' dignity. V,

xvi

SOURCE : http://www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/sidonius.html

Folio

27r du ms. lat. 2782 (XII-XIIIe siècles) répertoriant les lettres de Sidoine

Apollinaire.

Sidonius Apollinaris,

Letters. Tr. O.M. Dalton (1915): Preface to the online edition

Sidonius Apollinaris was

a Roman aristocrat of the 5th century AD. Born around 431 AD, he held

estates in Gaul. He pursued an official career under the emperors Avitus

(a kinsman), Majorian, and Anthemius, rising to be Prefect of Rome. But

all these emperors were murdered in turn by the sinister Ricimer, a barbarian

general holding the highest office in the state, that of Patrician, or Prime

Minister. Ricimer ostensibly governed in the Roman interest. In

reality he pursued no interest but his own, and his murder of the capable

Majorian ensured the collapse of the empire.

As Roman rule weakened,

the barbarians occupied more and more of Gaul. Sidonius had returned to

Gaul under Anthemius. Like so many other aristocrats, he had reluctantly

become Bishop in his local town, Clermont in Arvernia. The

advancing Visigoths under their king Euric moved into the region; Sidonius

helped organise resistance,since none of the Roman forces paid for from the

crushing taxation of the time were available to defend them. But after

enduring a siege, he found to his appalled horror that the imperial government

was plotting to betray the Arvernians, some of their strongest

supporters. (His outraged letter to Bishop Graecus, one of the go-betweens,

is included in this edition). And so it proved. Sidonius himself

was imprisoned by Euric.

States prepared to sell

their own allies to appease an advancing enemy have little prospect of

survival. In less than a dozen years, Roman rule had ceased everywhere in

the West; the consequence of its rulers placing themselves in the power of

those whose loyalties were ultimately non-Roman. Sidonius lived long

enough to outlive the last emperor, Julius Nepos. He died, sometime after

480, and is canonised as a saint.

Sidonius left two works;

a set of 24 Carmina or Poems, and 9 books of Letters. This

translation, in two volumes contains only the letters; both are available in

the Loeb text. The Poems include verse panegyrics of all three

emperors, and have considerable historical value.

Dalton included an

introduction of almost 200 pages; nearly a third of the book. It seems

permissable to wish that he had included the poems instead. This preface

has been written so that the general reader may orient himself first.

Roger Pearse

24th January 2003

Sidonius Apollinaris,

Letters. Tr. O.M. Dalton (1915) pp. xi-clv ; Introduction

INTRODUCTION

(CAIUS) SOLLIUS

APOLLINARIS (MODESTUS) SIDONIUS 1 was

born at Lyons, about the year 431, and died at Clermont perhaps in A.D. 489, at

the age of nearly sixty years.2 The

exceptional interest of the period covered by his life is apparent from these

dates; he saw the last sickness and the death of the Roman Empire in the West,

and is our principal authority for some of the events which attended its

extinction. He was a younger contemporary of Attila and Gaiseric. The campaigns

of Aëtius took place in his boyhood; he was a youth of about twenty when the

Huns were defeated on the Catalaunian plains, and for the first time in history

the Roman and the Teuton fought side by side against a common |xii enemy. He was about twenty-four when the house of

Theodosius became extinct with Valentinian III, and the Vandals plundered the

city of the Caesars (A.D. 455). He was still alive when Romulus Augustulus laid

down his diadem at the bidding of Odovakar. More than once his path crossed

that of the last emperors who ruled in Italy; as the son-in-law of Avitus, and

a high officer of state under Anthemius, he saw Rome in the final phases of her

imperial existence. In his own country he met or corresponded with every person

of importance. He had dined with Majorian, he had played backgammon with the

Visigoth Theodoric II; he lived to become first the prisoner and then the

subject of that monarch's fierce successor, Euric. He exchanged letters with

Lupus, Remigius, Faustus, and all the leaders of the Church in Gaul. There was

hardly a single distinguished name with which in some way or another his own

was not associated. Like Cassiodorus, he enjoyed an outlook over two worlds,

the old Roman civilization in its decay, and mediaeval society in its

beginnings. To paraphrase a sentence of Sir Thomas Browne, he stands like Janus

in the field of history.

Sidonius came of a

senatorial family long settled in Gallia Lugdunensis, a family to which, as he

himself says, the holding of high office seemed almost a hereditary right: both

his father and his grandfather had been prefects in Gaul.3 His

mother belonged to the gens |xiii of the Aviti,

which was connected with other noble provincial families, the Ferreoli, the

Ommatii, and the Agroecii; when therefore he married Papianilla, daughter of

the Avitus who became emperor, he may only have added a new tie to an old

alliance.4 He

had a brother, who may not have lived to mature age, as no letter is addressed

to him;5 he

had aunts or sisters and a mother-in-law, mentioned as taking care of one of

his children (V. xvi. 5). A nephew Secundus (III. xii), and a cousin

Apollinaris complete the list of his own relations, with the possible addition

of Simplicius, who is so often mentioned with Apollinaris that he may have been

his brother. He had two brothers-in-law, Ecdicius and Agricola,6 of

the latter of whom we hear little, of the former, much. For Ecdicius was the

hero of his native country of Auvergne. He distinguished himself by great

gallantry in the last struggle for independence (III. iii), and seems to have

had in him much of the spirit of mediaeval chivalry.7 Nor |xiv was he deficient in other gifts; he must have possessed

some talent for diplomacy, since he was instrumental in rallying the

Burgundians to the cause of Auvergne at a very critical moment. Sidonius and

Papianilla8 had

one son, Apollinaris, and three daughters, Alcima, Roscia, and Severiana.9 The

boy, whose early promise is mentioned in one of the most pleasing passages of

the Letters (IV. xii. 1), was destined to disappoint his parents, first in his

failure to maintain the intellectual promise of his youth, and later by more

serious deficiencies, recorded by other hands than those of his own father.10 Of

the girls, only Roscia and Severiana are |xv mentioned

in the Letters, and both in an incidental manner; for Sidonius was not

communicative on his family affairs. The name of Alcima does not occur at all:

we learn more of her from other sources than Sidonius himself tells us of her

sisters. She became noted for her devotion to the saints, and for her

munificence to the Church,11 and

is said to have joined her sister-in-law Placidina in a successful effort to

obtain the see of Clermont for her brother some years after her father's death

(see below, p. li, note 2).

Sidonius was educated in

his native city, where the schools, if less famous than those of Bordeaux, were

yet of high repute. He passed through the regular course of academic training,

the essential parts of which consisted of grammar and rhetoric; and in both

Letters and Poems preserves kindly memories of his teachers and fellow

students.12 As

might be expected from the fortunate circumstances of his birth, and his

father's rank as prefect, his youth was probably a happy one, passed

alternately between the city and the country estate, where he enjoyed games and

all the pleasures of |xvi the chase.13 His

love of eloquence began early; he refers to the delight with which, as a youth

of eighteen, he listened to the speech of Nicetius when Astyrius assumed the consulship

at Aries in 449 (VIII. vi. 5). After his marriage, which must have been an

early one, he probably divided his time between Lyons and Auvergne; in the

latter region was situated his father-in-law's estate of Avitacum, which was

ultimately to come to him through Papianilla, and of which he has left a

description (II. ii; Carm. xviii). It was probably during the first

years of his married life that he frequented the Visigothic Court at Toulouse,

from which he wrote home the very interesting letter descriptive of Theodoric

II to his brother-in-law Agricola (I. ii).14 Avitus,

to whose exertions the coalition of Roman and Visigoth against Attila had been

largely due, had long favoured an understanding between the two peoples. He had

been a familiar figure at the Court of Theodoric I, whose sons he had

endeavoured to imbue with Roman civilization; 15 it

was therefore natural that he should |xvii encourage

the visits of his son-in-law to the more important of these pupils. He may not

have clearly foreseen the part which he was destined personally to play in the

near future; but it must have appeared a possible contingency that the Goths

and their Gallo-Roman neighbours might once more be called upon to take

decisive action together. With Tonantius Ferreolus and many others, he may well

have shared the belief that the Roman understanding with the most civilized of

the barbaric peoples might save an Empire which Italy was too enfeebled to

lead. He had seen the Visigoths and the Burgundians in their homes, and learned

to appreciate the rude virtues and the manly strength which redeemed the

coarser elements in their nature. He dreamed perhaps of a Teutonic aristocracy

more and more refined by Latin influences, which should impart to the Romans

the qualities of a less sophisticated race and to their own countrymen a wider

acceptance of Italian culture.16 He

knew that for more than a century Gaul had been the most vigorous and

enlightened portion of the Empire in the West, and as Italy became year by year

more helpless, he may well have believed that the leadership of the decaying

state might pass into the control of his own country. But throughout he

probably gave Theodoric II credit for a greater disinterestedness than he

possessed; for in all likelihood the Visigothic king intended to exploit the

Roman connexion in the |xviii interest of himself

and his own people. Be that as it may, when, in 455, the line of Theodosius

became extinct with Valentinian III, the murderer of Aëtius, Avitus was sent

as magister milltum to secure the recognition of Petronius Maximus in

Gaul. But while he was at Toulouse, news came of that emperor's murder,

whereupon Theodoric urged him to assume the diadem himself.17 After