Saint Séverin Boèce

Philosophe et théologien

romain, martyr (+ 524)

Philosophe et théologien

romain, né dans une famille noble de Rome, Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus

Boethius avait fait ses études à Athènes et Alexandrie. Nommé consul sous le

roi Théodoric qui lui faisait confiance et lui donna le titre de Maître des

Bureaux. Leurs relations se détériorèrent à cause de leurs religions, ce qui

amena le martyre de Séverin. Il est l'auteur de nombreux ouvrages et

traductions.

"San Pietro in Ciel

d’Oro était l’église la plus importante de Pavie, même si elle était hors les

murs; elle avait été construite sur les lieux du martyre de Séverin Boèce, tué

en 525 par l’empereur Théodoric dont il avait été le conseiller. La dépouille

de Boèce est conservée aujourd’hui encore dans la crypte de l’église". (sanctuaires

lombards)

Commémoraison de saint

Séverin Boèce, martyr en 524 ou 525. Célèbre par sa science et ses écrits, il

fut détenu en prison, où il écrivit son traité “Sur la consolation de la

philosophie” et servit Dieu avec droiture jusqu’à la mort que lui infligea le

roi Théodoric, à Ticinum [Pavie] en Lombardie.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/12303/Saint-Severin-Boece.html

De

institutione musica by Boethius, XIIth century, Cambridge University Library.

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 12 mars 2008

Boèce et Cassiodore

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais parler

aujourd'hui de deux auteurs ecclésiastiques, Boèce et Cassiodore, qui vécurent

pendant les années les plus tourmentées de l'Occident chrétien et, en

particulier, de la péninsule italienne. Odoacre, roi des Erules, une ethnie

germanique, s'était rebellé, mettant un terme à l'empire romain d'Occident

(476), mais avait dû rapidement succomber aux Ostrogoths de Théodoric, qui

pendant plusieurs décennies s'assurèrent du contrôle de la péninsule italienne.

Boèce, né à Rome vers 480 dans la noble famille des Anicii, entra encore jeune

dans la vie publique, obtenant déjà la charge de sénateur à l'âge de vingt-cinq

ans. Fidèle à la tradition de sa famille, il s'engagea dans la politique,

convaincu qu'il était possible d'harmoniser les lignes directrices de la

société romaine avec les valeurs des nouveaux peuples. Et à cette nouvelle

époque de la rencontre des cultures, il considéra comme sa mission de

réconcilier et de mettre ensemble ces deux cultures, la culture romaine

classique et la culture naissante du peuple ostrogoth. Il fut très actif en

politique, également sous Théodoric, qui les premiers temps l'estima beaucoup.

Malgré cette activité publique, Boèce ne négligea pas ses études, se consacrant

en particulier à l'approfondissement de thèmes d'ordre philosophique et

religieux. Mais il écrivit également des manuels d'arithmétique, de géométrie,

de musique, d'astronomie: le tout avec l'intention de transmettre aux

nouvelles générations, aux nouveaux temps, la grande culture gréco-romaine.

Dans ce cadre, c'est-à-dire dans l'engagement pour promouvoir la rencontre des

cultures, il utilisa les catégories de la philosophie grecque pour proposer la

foi chrétienne, ici aussi à la recherche d'une synthèse entre le patrimoine

hellénistique-romain et le message évangélique. C'est précisément pour cela que

Boèce a été présenté comme le dernier représentant de la culture romaine

antique et le premier des intellectuels du Moyen-âge.

Son œuvre certainement la

plus célèbre est le De consolatione philosophiae, qu'il rédigea en prison

pour donner un sens à sa détention injuste. En effet, il avait été accusé de

complot contre le roi Théodoric pour avoir pris la défense d'un ami, le

sénateur Albin, lors de son jugement. Mais cela était un prétexte: en

réalité Théodoric, arien et barbare, soupçonnait Boèce d'éprouver de la

sympathie pour l'empereur byzantin Justinien. De fait, jugé et condamné à mort,

il fut exécuté le 23 octobre 524, à 44 ans seulement. Précisément en raison de

cette fin dramatique, il peut parler à partir de sa propre expérience à l'homme

d'aujourd'hui également, et surtout aux très nombreuses personnes qui subissent

le même sort à cause de l'injustice présente dans de nombreux domaines de la

"justice humaine". Dans cette œuvre, alors qu'il est en prison il

recherche le réconfort, il recherche la lumière, il recherche la sagesse. Et il

dit avoir su distinguer, précisément dans cette situation, entre les biens

apparents - en prison ceux-ci disparaissent - et les vrais biens, comme

l'amitié authentique, qui même en prison ne disparaissent pas. Le bien le plus

élevé est Dieu: Boèce apprit - et il nous l'enseigne - à ne pas tomber

dans le fatalisme, qui éteint l'espérance. Il nous enseigne que ce n'est pas le

destin qui gouverne, mais la Providence et que celle-ci a un visage. On peut

parler avec la Providence, car Dieu est la Providence. Ainsi, même en prison il

lui reste la possibilité de la prière, du dialogue avec Celui qui nous sauve.

Dans le même temps, même dans cette situation il conserve le sens de la beauté

et de la culture et rappelle l'enseignement des grands philosophes antiques

grecs et romains, comme Platon, Aristote - il avait commencé à traduire ces

grecs en latin -, Cicéron, Sénèque, et également des poètes comme Tibulle et

Virgile.

Selon Boèce, la

philosophie, au sens de la recherche de la véritable sagesse, est le véritable

remède de l'âme (lib. I). D'autre part, l'homme ne peut faire l'expérience du

bonheur authentique que dans sa propre intériorité (lib. II). C'est pourquoi

Boèce réussit à trouver un sens en pensant à sa tragédie personnelle à la

lumière d'un texte sapientiel de l'Ancien Testament (Sg 7, 30-8,1), qu'il

cite: "Contre la sagesse le mal ne prévaut pas. Elle s'étend avec

force d'un bout du monde à l'autre et elle gouverne l'univers pour son

bien" (lib. III, 12: PL 63, col. 780). La soi-disant prospérité des

méchants se révèle donc mensongère (lib. IV), et la nature providentielle de

la adversa fortuna est soulignée. Les difficultés de la vie révèlent

non seulement combien celle-ci est éphémère et de brève durée, mais elles se

démontrent même utiles pour déterminer et conserver les rapports authentiques

entre les hommes. L'Adversa fortuna permet en effet de discerner les vrais amis

des faux et elle fait comprendre que rien n'est plus précieux pour l'homme

qu'une amitié véritable. Accepter de manière fataliste une situation de

souffrance est absolument dangereux, ajoute le croyant Boèce, car "cela

élimine à la racine la possibilité même de la prière et de l'espérance théologale

qui se trouvent à la base de la relation de l'homme avec Dieu" (lib. V,

3: PL 63, col. 842).

Le discours final

du De consolatione philosophiae peut être considéré comme une

synthèse de tout l'enseignement que Boèce s'adresse à lui-même et à tous ceux

qui pourraient se trouver dans la même situation. Il écrit ainsi en

prison: "Combattez donc les vices, consacrez-vous à une vie vertueuse

orientée par l'espérance qui pousse le cœur vers le haut, jusqu'à atteindre le

ciel avec les prières nourries d'humilité. L'imposition que vous avez subie

peut se transformer, si vous refusez de mentir, en l'immense avantage d'avoir

toujours devant les yeux le juge suprême qui voit et qui sait comment sont

vraiment les choses" (lib. V, 6: PL 63, col. 862). Chaque détenu,

quel que soit le motif pour lequel il est en prison, comprend combien cette

condition humaine particulière est lourde, notamment lorsqu'elle est aggravée,

comme cela arriva à Boèce, par le recours à la torture. Particulièrement

absurde est aussi la condition de celui qui, encore comme Boèce - que la ville

de Pavie reconnaît et célèbre dans la liturgie comme martyr de la foi -, est

torturé à mort sans aucun autre motif que ses propres convictions idéales,

politiques et religieuses. Boèce, symbole d'un nombre immense de détenus

injustement emprisonnés de tous les temps et de toutes les latitudes, est de

fait une porte d'entrée objective à la contemplation du mystérieux Crucifié du

Golgotha.

Marc Aurèle Cassiodore,

un calabrais né à Squillace vers 485, qui mourut à un âge avancé à Vivarium

vers 580, fut un contemporain de Boèce. Lui aussi d'un niveau social élevé, il

se consacra à la politique et à l'engagement culturel comme peu d'autres

personnes dans l'Occident romain de son époque. Les seules personnes qui purent

l'égaler dans son double intérêt furent peut-être Boèce, déjà mentionné, et le

futur Pape de Rome, Grégoire le Grand (590-604). Conscient de la nécessité de

ne pas laisser sombrer dans l'oubli tout le patrimoine humain et humaniste,

accumulé au cours des siècles d'or de l'empire romain, Cassiodore collabora

généreusement, et aux niveaux les plus élevés de la responsabilité politique,

avec les peuples nouveaux qui avaient traversé les frontières de l'empire et

qui s'étaient établis en Italie. Il fut lui aussi un modèle de rencontre

culturelle, de dialogue, de réconciliation. Les événements historiques ne lui

permirent pas de réaliser ses rêves politiques et culturels, qui visaient à

créer une synthèse entre la tradition romano-chrétienne de l'Italie et la

nouvelle culture des Goths. Ces mêmes événements le convainquirent cependant du

caractère providentiel du mouvement monastique, qui s'affirmait dans les terres

chrétiennes. Il décida de l'appuyer en lui consacrant toutes ses richesses

matérielles et toutes ses forces spirituelles.

Il conçut l'idée de

confier précisément aux moines la tâche de retrouver, conserver et transmettre

à la postérité l'immense patrimoine culturel de l'antiquité, pour qu'il ne soit

pas perdu. C'est pourquoi il fonda Vivarium, un monastère dans lequel tout

était organisé de manière à ce que le travail intellectuel des moines soit

estimé comme très précieux et indispensable. Il disposa que les moines qui

n'avaient pas de formation intellectuelle ne devaient pas s'occuper seulement

du travail matériel, de l'agriculture, mais également de transcrire des

manuscrits et aider ainsi à transmettre la grande culture aux générations

futures. Et cela sans aucun dommage pour l'engagement spirituel monastique et

chrétien et pour l'activité caritative envers les pauvres. Dans son

enseignement, publié dans plusieurs ouvrages, mais surtout dans le traité De

anima et dans les Institutiones divinarum litterarum, la prière (cf. PL

69, col. 1108), nourrie par les saintes Ecritures et particulièrement par la

lecture assidue des Psaumes (cf. PL 69, col. 1149), a toujours une position

centrale comme nourriture nécessaire pour tous. Voilà, par exemple, la façon

dont ce très docte calabrais introduit son Expositio in Psalterium:

"Ayant refusé et abandonné à Ravenne les sollicitations de la carrière

politique, marquée par le goût écœurant des préoccupations mondaines, et ayant

goûté le Psautier, un livre venu du ciel comme un authentique miel de l'âme, je

me plongeai avec avidité, comme un assoiffé, dans la lecture incessante afin de

me laisser imprégner entièrement de cette douceur salutaire, après en avoir eu

assez des innombrables amertumes de la vie active" (PL 70, col. 10).

La recherche de Dieu,

visant à sa contemplation - note Cassiodore -, reste l'objectif permanent de la

vie monastique (cf. PL 69, col. 1107). Il ajoute cependant que, avec l'aide de

la grâce divine (cf. PL 69, col. 1131.1142), on peut parvenir à

une meilleure compréhension de la Parole révélée grâce à

l'utilisation des conquêtes scientifiques et des instruments culturels

"profanes", déjà possédés par les Grecs et les Romains (cf. PL 69,

col. 1140). Cassiodore se consacra, quant à lui, aux études philosophiques,

théologiques et exégétiques sans créativité particulière, mais attentif aux

intuitions qu'il reconnaissait valables chez les autres. Il lisait en

particulier avec respect et dévotion Jérôme et Augustin. De ce dernier, il

disait: "Chez Augustin il y a tellement de richesse qu'il me semble

impossible de trouver quelque chose qu'il n'ait pas déjà abondamment

traité" (cf. PL 70, col. 10). En citant Jérôme, en revanche, il exhortait

les moines de Vivarium: "Ce n'est pas seulement ceux qui luttent

jusqu'à verser leur sang ou qui vivent dans la virginité qui remportent la

palme de la victoire, mais également tous ceux qui, avec l'aide de Dieu,

l'emportent sur les vices du corps et conservent

la rectitude de la foi. Mais pour que vous puissiez, toujours avec l'aide de

Dieu, vaincre plus facilement les sollicitations du monde et ses attraits, en

restant dans celui-ci comme des pèlerins sans cesse en chemin, cherchez tout

d'abord à vous garantir l'aide salutaire suggérée par le premier psaume qui

recommande de méditer nuit et jour la loi du Seigneur. En effet, l'ennemi ne

trouvera aucune brèche pour vous assaillir si toute votre attention est occupée

par le Christ" (De Institutione Divinarum Scripturarum, 32: PL 70,

col. 1147D-1148A). C'est un avertissement que nous pouvons accueillir comme

valable également pour nous. Nous vivons, en effet, nous aussi à une époque de

rencontre des cultures, du danger de la violence qui détruit les cultures, et

de l'engagement nécessaire de transmettre les grandes valeurs et d'enseigner

aux nouvelles générations la voie de la réconciliation et de la paix. Nous

trouvons cette voie en nous orientant vers le Dieu au visage humain, le Dieu

qui s'est révélé à nous dans le Christ.

* * *

Je salue les pèlerins

francophones, en particulier les jeunes du collège de Vaugneray et les pèlerins

de l’Île de la Réunion. Puissiez-vous mobiliser toutes les ressources de votre

intelligence pour rechercher toujours la vraie sagesse, qui est le Christ. Avec

ma Bénédiction apostolique.

© Copyright 2008 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080312.html

Cote : Besançon - BM - ms. 0434 f. 314 Sujet : Boèce et la Philosophie Auteur : Boethius Titre : Consolation de Philosophie Datation : 1372

Boèce

(470/480-525)

Martyr

De la consolation de la

Philosophie - lire - télécharger

La consolation de la philosophie (trad. Jean-Yves Guillaumin), Belles-Lettres, 2002.

Courts traités de théologie, Le Cerf, 1991.

Boèce (Anicius Manlius

Torquatus Severinus Boetius, dit) philosophe latin, né vers 470 à Rome, mort en

525 à Pavie. Il fit ses études à Rome, puis à Athènes. A son retour, il fut

élevé trois fois au consulat (en 487, 510 et 511) par Théodoric, roi des

Wisigoths . Mais des ennemis trouvèrent le moyen lui faire perdre la

confiance de Théodoric. Des remontrances qu'il adressa à ce dernier, au sujet

des exactions des receveurs des deniers publics, furent le prétexte de sa

disgrâce. Un décret du sénat le déclara coupable de trahison; renfermé dans une

prison, il fut mis à mort en 525. Ses biens, dont la confiscation avait été prononcée,

furent rendus à sa veuve par la reine Amalasonte qui fit relever ses statues.

Boèce fut l'écrivain et le philosophe le plus distingué de son temps. Il avait

embrassé la doctrine d'Aristote, et commenté ses ouvrages; il avait aussi

composé des traités de théologie et de mathématiques.

En librairie - Ouvrages

de Boèce :

Boèce. Consolation de

Philosophie

Traduit du latin

par J-Y. Guillaumin

La Consolation est un

texte unique dans l’antiquité, un mélange de 39 proses et 39 poésies, où une

figure allégorique, Philosophia, s’adresse à son élève (Boèce) et lui apporte

la consolation de son enseignement (évidemment une présentation du monde de

type néo-platonicien). Ce dialogue est l’oeuvre d’un haut personnage romain

chrétien, sénateur et patrice, emprisonné et accusé de haute trahison, alors

qu’il attendait la mort, vers 524 après J.-C.. Cette situation « d’urgence » et

d’imminence de la mort (pensons à celle de Socrate), démenti par la belle

sobriété du texte, est devenu un modèle pour la philosophie, dernier rempart de

la beauté et de la méditation, symbole de résistance à l’oppression et de

méditation sur la condition humaine.

La Consolation de

Philosophie devait devenir l’un des ouvrages fondamentaux du Moyen Age, à côté

de ceux de St Augustin, de St Benoît et de Bède le vénérable. C’est évidemment

aussi un lointain modèle de la Divine Comédie de Dante. Boèce est un parfait

représentant de la haute culture italienne de l’époque, déchirée entre sa

fidélité à une tradition classique tenace (les satires grecques ou latines, la

philosophie grecque, les consolations de Cicéron, Ovide ou Sénèque) et les

réalités politiques de son temps, celui de l’Empereur Justinien (occupation par

les Goths, la persécution des chrétiens, attrait d’un Orient encore brillant de

sa vie culturelle).

Boèce, après des études

approfondies, qui l’avaient mis en contact avec les sources grecques

néoplatoniciennes, avait conçu un vaste projet d’acclimatation de la culture

grecque en Occident par le moyen de traductions latines des grands textes

philosophiques et scientifiques de l’Antiquité : c’est pourquoi il est révéré

par tout le Moyen Age, qui lui doit sa connaissance des textes aristotéliciens

et de leurs commentaires néo-platoniciens.

La présente traduction,

inédite, est due à un spécialiste de Boèce ; elle tient compte des très

nombreux travaux modernes (édition du texte latin chez Loeb en 1973).

BOÈCE

La Fortune est plus

bénéfique aux êtres humains quand elle est mauvaise que quand elle est bonne.

L'une, en effet, quand elle se montre séduisante, est toujours en train de

mentir avec son apparence de bonheur ; l'autre, au contraire, est toujours

sincère quand elle révèle, par ses volte-face, son instabilité. L'une trompe,

l'autre instruit ; l'une en faisant croire à un faux bonheur, ligote l'âme de

ceux qui y trouvent leur jouissance, l'autre la libère en lui faisant prendre

conscience de la précarité de la chance... La bonne Fortune use de ses charmes

pour égarer les gens loin du bien véritable, tandis que la mauvaise les

accroche au passage pour les ramener vers les véritables valeurs.

N'espère rien, n'aie peur de rien

Et tu désarmeras ton adversaire.

Quand on est agité par la crainte ou l'espoir,

Faute d'être calme et de se contrôler

On lâche son bouclier, on abandonne son poste

Et on resserre le lien qui sert à nous traîner.

Qu'est-ce que la santé des âmes sinon la bonté ? Et leur maladie sinon la méchanceté ?

Les sages n'éprouvent pas la moindre tentation de haine. Car qui pourrait haïr

les bons, sinon des imbéciles ? Quant à haïr les méchants, ce serait

déraisonnable. Si en effet, de même que l'asthénie est une maladie du corps, la

méchanceté est une sorte de maladie de l'âme, étant donné qu'à nos yeux, les

gens malades dans leur corps ne méritent absolument pas d'être haïs mais plutôt

d'être pris en pitié, raison de plus de prendre en pitié plutôt que de les

harceler, ceux dont l'âme est accablée par un mal plus pitoyable que n'importe

quelle forme d'asthénie : la méchanceté.

Veux-tu retourner à autrui ce qu'il mérite ?

Aime les bons et prends pitié des méchants.

Plus une chose s'éloigne de l'Intelligence suprême, plus les liens du destin l'enserrent, et une chose est d'autant moins dépendante du destin qu'elle se rapproche étroitement de ce pivot de l'univers. Si elle adhère fermement à l'Intelligence supérieure stable, elle échappe aussi à la nécessité du destin.

Si tu veux, sous une lumière limpide discerner le vrai,

Coupe au plus court : chasse les joies, chasse la peur,

Défie-toi de l'espoir, éloigne la douleur.

L'esprit est embrumé et bridé quand il est sous leur emprise

.

La sagesse consiste à évaluer la finalité de toutes choses et c'est précisément

cette faculté de passer d'un extrême à l'autre qui ne rend pas redoutables les

menaces de la Fortune, ni souhaitables, ses séductions.

Si on cherche profondément le vrai

Et qu'on désire ne pas se fourvoyer,

On doit réfléchir sur soi sa lumière intérieure,

Concentrer les amples mouvements de sa pensée

Et apprendre à son âme que ce qu'elle entreprend au-dehors,

Elle le possède déjà, déposé secrètement en elle.

Tout homme heureux est un

dieu. Bien qu'il n'y ait évidemment qu'un seul Dieu par nature, par

participation, rien n'empêche qu'il n'y en ait autant qu'on veut.

O bienheureux genre humain

Si votre cœur obéit à l'amour

Auquel obéit le ciel.

Vous cherchez, je crois,

à bannir le besoin par l'abondance. Or cela vous mène au résultat inverse. En

effet, on a besoin de nombreuses aides pour protéger son mobilier précieux,

quand on en a beaucoup, et il vrai que les besoins sont multiples quand on

possède beaucoup, alors qu'ils sont très réduits quand on mesure sa richesse à

ce que nécessite la nature et non à une ambition démesurée.

Si le besoin, éternelle

bouche béante sans cesse à l'affût, trouve sa satisfaction dans les richesses,

il subsiste nécessairement un autre besoin à satisfaire. Sans compter qu'il

suffit d'un rien pour satisfaire la nature tandis que rien ne suffit à

satisfaire la convoitise. Dans ces conditions, si les richesses, loin d'écarter

le besoin, créent elles-mêmes leurs propres besoins, comment peut-on croire

qu'elles offrent une garantie d'indépendance ?

Mais non ! Plus dévastateur que l'Etna,

Brûle le dévorant désir de posséder !

Où se cache le bien qu'ils convoitent,

Peu leur importe de l'ignorer :

Au lieu de le chercher par-delà le ciel étoilé,

Ils le cherchent, englués dans la terre...

Comment les blâmer à la mesure de leur bêtise ?

Qu'ils sollicitent richesse et honneurs !

Quand ils auront peiné pour acquérir les faux biens,

Qu'ils apprennent alors à distinguer les vrais.

Accorde, Père, à mon esprit de rejoindre le lieu de ton règne,

Accorde-lui de visiter la source du bien, de trouver la lumière

Et de ne plus poser que sur Toi les regards de mon âme.

Disloque les nuages et pesanteurs de la masse terrestre

Et resplendis de tous tes feux ! Car Tu es la sérénité,

Tu es le repos et la paix des justes : Te voir est leur fin,

Toi l'origine, le conducteur, le guide, le chemin et l'arrivée tout à la fois.

Extraits de la Consolation

de la Philosophie (Ed. Rivages - 1989).

BOÈCE (en latin, Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus Boetius)

Poète latin (Rome vers 480 - près de Pavie, 524)

C'est essentiellement au travers de ses traductions que le Moyen Âge connut les œuvres de Platon et d'Aristote . Il fut l'un des fondateurs de la scolastique médiévale.

Ministre de Théodoric, il tomba en disgrâce, fut emprisonné, supplicié et exécuté.

Pendant sa captivité il composa vers 523 un dialogue philosophique, De Consolatione philosophae [De la consolation de la philosophie] qui exerça une profonde influence sur la pensée et la littérature médiévales et fut avec l'Histoire d'Alexandre et Navigatio Sancti Brendani un des trois textes importants circulant en Europe au Moyen Âge.

Les cinq livres de la Consolation sont un dialogue alternant vers et prose, entre une femme qui personnifie la philosophie et l'auteur qui attend la mort. Il s'agit d'une méditation sur le hasard et la nécessité de l'existence humaine, la providence divine et la confiance que l'homme vertueux doit placer en elle.

voir Bibliographie

- Courts traités de théologie, présentation par Hélène Merle, Cerf, 1991, [154 pages]

- Consolation de la Philosophie, Préface de Marc Fumaroli, Traduit du latin par Colette Lazam, Rivages, [220 pages]

collaboration(s) : Hélène Merle

Néoplatonicien, Boèce (480 ? -525) a essayé de répondre aux difficiles questions que posaient à la doctrine chrétienne les philosophes « païens ». Ces "Courts traités" ("Opuscula sacra") traitent de la trinité, de l’essence de Dieu, de la nature humaine et de la nature divine du Fils, etc. L’argumentation de Boèce a servi de « bréviaire » à nombre de grands auteurs du Moyen Âge comme Jean Scot, Anselme, Thomas d’Aquin, Raymond Lulle.

langue originale : latin

SOURCE : http://jesusmarie.free.fr/boece.html

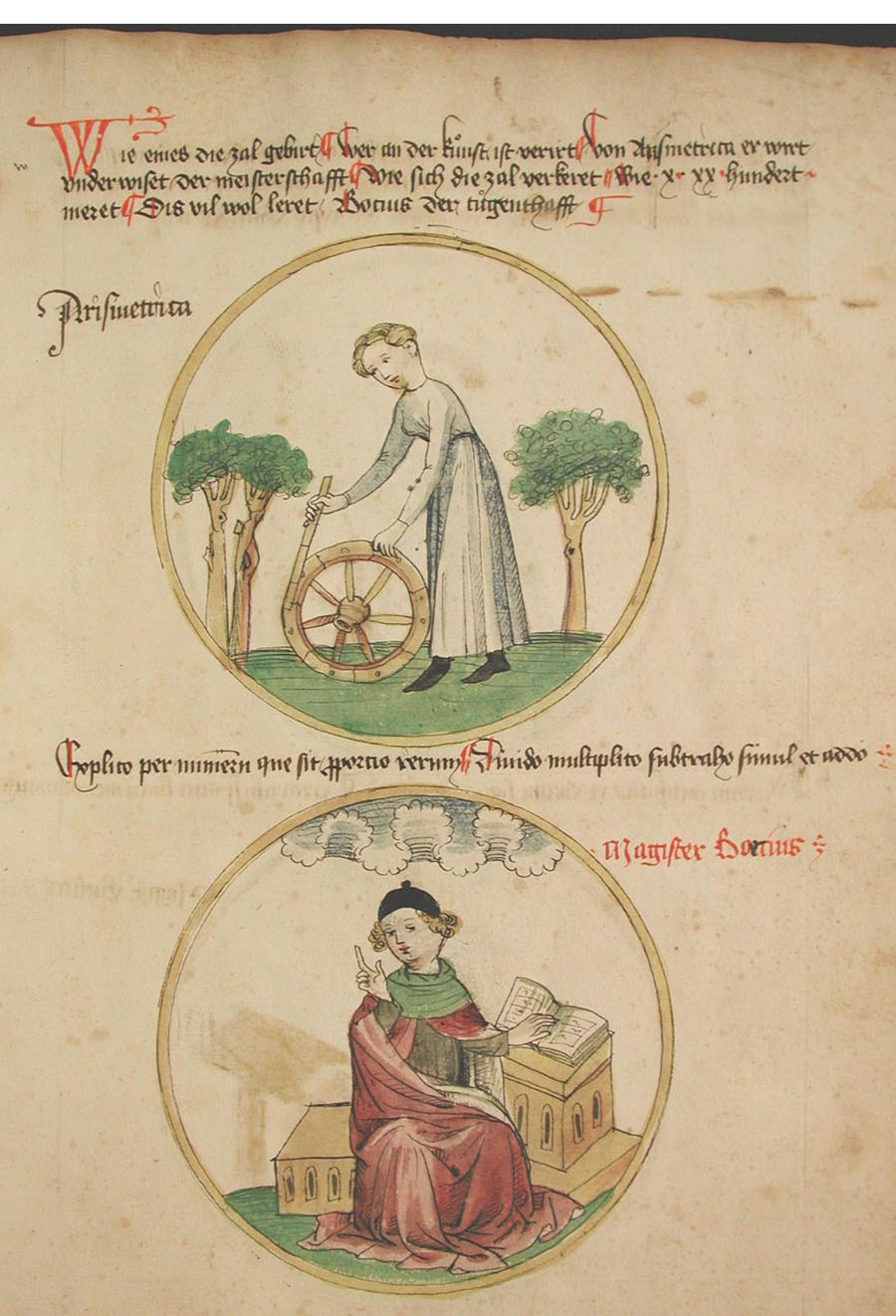

Die

sieben freien Künste. Arithmetik und Boethius. Anicius Manlius Torquatus

Severinus Boethius.

Kolorierte Federzeichnung. Unibibliothek Salzburg, M III 36

The

Seven liberal arts. Arithmetic and Boethius. Anicius Manlius Torquatus

Severinus Boethius.

Artes

Liberales. Arifmetica et Boethius. Так в самом изображении, правильнее:

"Arithmetica".

Семь

свободных искусств. Арифметика и Боэций. Аниций Манлий Торкват Северин

Боэций.

Boèce

Boetius Anicius Mantius

Severinus

480-524

Homme d’État, philosophe,

mathématicien. En 485 il épouse la fille du consul Symmaque (préfet de Rome,

prince du sénat, exécuté en 525). En 500 il est sénateur et patrice, en 510,

nommé consul. Il est ministre de Théodoric, roi des Ostrogoths à Rome, en 522,

maître des offices. Ses deux fils, encore adolescents sont nommés consuls. En

523 il est envoyé en exil et exécuté en 524, sur l’ordre de Théodoric.

La place de Boèce, dans

l’histoire du traité de théorie musicale, comme dans celle de la pensée philosophique

est importante. Elle tient à des conjonctures liées à ses choix conceptuels, à

la situation politique de Rome à son époque, et à l’utilisation que les

intellectuels firent du personnage et de l’oeuvre.

Boèce est un grand

dignitaire romain, ministre du roi Théodoric à Rome où se disputent alors trois

pouvoirs. Celui du roi barbare Théodoric, celui de la papauté, protégé par le

roi incroyant, et l’empereur de Byzance, Justin.

Boèce, aristocrate romain

tient aux prérogatives de sa caste, menacées parles trois pouvoirs. Sa culture

d'aristocrate romain comprend la connaissance du grec. Il traduit notamment

Aristote et des écrits relatifs à la théorie musicale (Ptolémée, Nicomaque) en

latin. En philosophie, il est proche de Martianus Capella. En politique, il

croit que Rome décadente ne peut être relevée que par les peuples barbares de

Gaule.

Théodoric suivra les

conseils de Boèce, en se tournant vers la Gaule barbare, et en traitant avec

les fils de Clovis lors du partage du royaume burgonde en 523. Malheureusement,

ce partage se fit à son désavantage.

Sans doute Boèce se

fit-il quelques ennemis alors qu’il était un Maître des Offices, semble-t-il

intègre la légende selon laquelle Boèce aurait comploté contre Théodoric avec

l’empereur de Byzance, est tardive et tend à effacer la responsabilité de

l’Église.

Les trois pouvoirs qui se

disputaient alors l’héritage de l’empire romain n’avaient rien à attendre de

Boèce, ni sur le plan religieux, ni sur ceux de la philosophie et de la

politique. Son Traité de la réincarnation est dédié à Jean, diacre de

l’Église Romaine (pape en 523, au moment de la condamnation de Boèce et de sa

réconciliation avec l’empereur de Byzance (Justin).

Glaréan, dans la préface

à l’édition des oeuvres de Boèce (Bâle 1546), met en doute l’authenticité d’une

partie de ces écrits, qui sont selon lui, peu chrétiens : Boèce ne parle que de

la malice du siècle, l’instabilité de la fortune, le pouvoir des méchants en ce

monde. Un auteur chrétien, et sur toutcelui qui a écrit les Traités de

l’Incarnation et de la Trinité n'aurait manqué de nommer le

Christ au moins une fois, et de chercher dans la foi la consolation.

Pourtant, Boèce est très

vite considéré comme un penseur chrétien, et comme une autorité par les

intellectuels. Il en est autrement de la hiérarchie religieuse. Ce sont les

Jésuites en feront officiellement un martyre. L’Église reste prudente. Un culte

local dédié à Boèce, en Italie, ne sera reconnu (par le pape Léon XIII) qu’en

1883.

Dans le fond, la pensée

de Boèce était plus embarrassante pour l’Église romaine que pour Théodoric. On

peut penser que son destin tragique est lié aux tractations de la

réconciliation de l’empereur et du pape, alors que la vitalité des peuples

barbares de Gaule s’affirmait.

Pour le traité de théorie

musicale, l’oeuvre de Boèce est en quelque sorte un modèle scolaire qui se fait

sentir jusqu’au XVIIe siècle, notamment pour ce qui concerne le calcul des

intervalles et du monocorde, et l’harmonie des sphères. On associe souvent

Boèce et Cassiodore, comme les deux premiers grands théoriciens de la musique

du Moyen Âge.

Contemporains, tous deux

consuls, tous deux ministres de Théodoric. Mais il convient en fait de les

opposer. Cassiodore s’inscrit en plein dans la tradition catholique romaine, et

ce sont les auteurs romains, notamment saint Augustin, qui fondent son oeuvre.

Enfin, si l’on se réfère statistiquement aux manuscrits et éditions imprimées,

Cassiodore n’atteint pas la renommée de Boèce.

Contre Euthychès et

Nestorius

De hebdomadibus

De trinitate (De la

trinité)

Utrum pater

De fide catholica (De la

foi catholique)

La Consolation

philosophique [traduction

de Louis Judicis, 1881] ; [traduction

Léon Colesse,1771, rééditée en 1835].

De Institutione Musica

Plan de

l’Institutione musicale

Livre I (ms. 15. 22), I.

De tribus generibus musicae–II. De uocibus ac musicae elementis – III. De

speciebus inaequalitatis – IIII. Quae inaequalitatis species consonantiis

aptentur – V. Cur multiplicitas et superparticularitas consonantiis deputentur.

– VI. Quae proportiones quibus consonantiis musicis aptentur. – VII. Quid sit

sonus. quid interuallum. quid concinentia. – VIII. Non omne iudicium dandum

esse sensibus. sed amplius rationi esse credendum – IX. Que-madmodum Pytagoras

proportiones consonantiarum inuestigauerit – X. Quibus modis uariae a Pythagora

proportiones consonantiarum perpensae sint – XI. De diuisione uocum earumque

explanatione – XII. Quod infinitatem uocum humana natura finierit – XIII. Quis

modus sit audiendi – XIIII. De ordine theorematum idest speculationum – XV. De

consonantiis et tono et semotonio – XVI. In quibus primis numeris semitonium

constet – XVII. Diatessaron a diapente tono distare – XVIII. Diapason quinque

tonis et duobus semitoniis iungi – XIX. De additione cordarum earumque

nominibus – XX. De additione octauae corde – XXI. De generibus cantile-nae –

XXII. De ordine cordarum. nominibusque earum in tribus generibus – XXIII. Quid

sint inter uoces in singulis generibus proportiones – XXIIII. Quid sit sinaphe

– XXV. Quid sit die-zeuxis – XXVI. De differentia toni inter mesen et paramesen

– XXVII. Quibus nominibus ne-ruos appellauerit Albinus – XXVIII. Qui nerui

quibus sideribus comparentur – XXIX. Quae sit natura consonantiarum – XXX. Vbi

consonantiae reperiuntur – XXXI. Quemadmodum Plato dicat fieri consonantias –

XXXII. Quid contra Platonem Nicomachus sentia – XXXIII. Quae consonantia

quam merito praecedat – XXXIIII. Quo sint modo accipienda quae dicta sunt –

XXXV. Quid sit musicus. — Livre II (ms. 15. 22), I. Quid Phytagoras

philosophiam esse cons-tituerit – II. De differentiis quantitatis. et quae cui

sit disciplinae deputata – III. De relatiuae quantitatis diffentiis – IIII. Cur

multiplicitas caeteris antecellat – V. Quid sint quadrati numeri. deque his

speculatio – VI. Omnem aequalitatem ex aequalitate procedere. eiusque demonstratio

– VII. Regula quotlibet continuas proportiones. et supparticulares inueniniendi

– VIII. De pro-portione numerorum qui ab aliis metiuntur – IX. Quae ex

multiplicibus et superparticularibus multiplicitates fiant – X. Qui

superparticulares quos multiplices effician – X. De arithmetica. geometrica.

armonica medietate – XII. De continuis medietatibus et disiunctis – XIII. Cur

ita appellatae sunt superius digestae medietates – XIIII. Quemadmodum ab

aequalitate supradictae processerint medietates – XV. De armonica medietate.

deque ea uberior speculatio – XVI. Quemadmodum inter duos terminos supradictae

medietates uicissim locentur – XVII. De con-sonantiarum merito uel modo

secundum Nicomachum – XVIII. De ordine consonantiarum sententia Eubolis et

Hispasi – XIX. Sententia Nicomachi de quibus consonantiis apponantur –

XX. Quid oporteat praemitti. ut diapason in multiplici genere demonstretur

– XXI. Demonstra-tio per impossibile diapason in multiplici genere esse –

XXII. Demonstratio diapente. diatessa-ron et tonum in superparticulari esse –

XXIII. Demonstratio diapente. diatessaron in maximis superparticularibus esse –

XXIIII. Diapente in sesqualtera. diatessaron in sesquitertia esse. to-num in

sesquioctaua – XXV. Diapason ac diapente in tripla proportione esse. in

quadrupla bis diapason – XXVI. Diatessaron ac diapason. non esse secundum

Pitagoricos consonantias – XXVII. De semitonio. in quibus numeris minimis

constet – XXVIII. Demonstrationes non esse CCXLIII ad CCLVI toni medietatem –

XXIX. De maiore parte toni in numeris constet – XXX. Quibus proportionibus

diapente ac diapason constent. et quoniam diapason VI tonis non cons-tent.

– Expliciunt capitula. Incipit liber secundus. – LIVRE III (ms.15.

22) – [I. addition mar-ginale] ADVERSVS Aristoxenum demonstratio superparticularem

proportionem diuidi in aequa non posse. atque ideo nec tonum. – [II. Manquant]

– III. Aduersus Aristoxenem demonstratio-nes diatessaron consonantiam ex duobus

tonis semitonioque non constare. nec diapason sex tonis – IIII. Diapason consonantiam

sex tonis comate excedi. et quit sit minor numerus comatis – V. Quomodo

Philolaus tonum diuidat – [VI. Addition marginale.] Sonum ex duobus semito-niis

et comate distare – VII. Demonstratio tonum duobus semitoniis comate distare –

VIII. De minoribus semitonii interuallis – IX. De toni partibus per

consonantias sumendis – X. Regula semitonii sumendi – XI. Demonstratio Architae

superparticularem proportionem in aequa diuidi non posse. eiusque repraehensio

– XII. In qua proportione numerorum sit coma. et quoniam in ea quae maior est

quam LXXV ad LXXIIII. minor quam LXXIIII ad LXXIII – XIII. Quod semitonium

minus maius quidem sit. quam XX ad XIX. minus uero quam XIX minus quam decem et

nouem semis. ad decem et octo semis – XIIII. Semitonium minus maius quidem esse

tribus comatibus. minus uero quattuor. XV – Apotomen maiorem esse quam quattuor

comata. minorem quam quinque tonum esse maiorem quam octo, minorem quam nouem –

XVI. Supe-rius dictorum per numeros demonstratio. – Livre IV (ms. 15. 22)

– I. VOCVM differentias in quantitate consistere – II. Diuersae de interuallis

speculationes – III. Musicarum per grecas ac latinas litteras notarum

nuncupatio – IIII. Musicarum notarum per uoces conueniens dispositio in tribus

generibus – V. Monochordi regularis partitio in genere diatonico – VI.

Monochordi netarum hyperboleon per tria <spatium 7 litt.> genera partitio

– VII. Ratio superius digestae descriptionis – VIII. Monochordi netarum

diezeugmenon per tria genera partitio – IX. Mono-chordi meson per tria genera partitio

– X. Monochordi hypaton per tria genera partitio et totius dispositio

descriptionis – XI. Ratio superius dispositae descriptionis – XII De

stantibus uocibus ac mobilibus – XIII De consonantiarum speciebus – XIIII.

Dispositio notarum per singulos modos ac uoces in descriptione – XV. Descriptio

continens modos. ordinem ac differentia – XVI. Ratio superius dispositae

modorum descriptionis – XVII Quemadmodum indubitanter musicae consonantiae aure

diiudicari possint. – Livre V (Migne) – Caput I, De vi harmonicae et quae

sint ejus instrumenta judicii et quoniam usque sensibus oporteat credi. –

Chapitre II, Quid sid harmonica regula, vel quam intentionem harmonici

Pythagorici vel Aristoxenus, vel Ptole-maeus – Chapitre III, In quo

Aristoxenus vel Pythagorici vel Ptolemaeus gravitatem atque acu-mem constare

posuerunt. – Chapitre IV, De sonorum differentiis Ptolemaei sententia.

– Chapi-tre V, Quae voces enharmoniae sunt aptae. – Chapitre VI,

Quem numerum proportionum Pythagorici statuunt. – Chapitre VII, Quod

reprehendat Ptolemaeus Pythagoricos in numero propositionum. – Chapitre

VIII, Demonstratio secundum Ptolemaeum diapason et diatessaron consonantiae.

– Chapitre IX, Quae sit proprietas diapason consonantiae. –

Chapitre X, Quibus modis Ptolemaeus consonantias statuat. – Chapitre XI,

Quae sint aequisonae, vel quae conso-nae, vel quae hemmelis. – Chapitre

XII, Quemadmodum Aristoxenus intervallum consideret. – Chapitre XIII,

Descriptio octochordi, qua ostenditur diapason consonantiam minorem esse sex

tonis. – Chapitre XIV, Diatessaron consonantiam tetrachordo contineri.

– Chapitre XV, Quo-modo Aristoxenus vel tonum dividat, vel genera ejusque

divisionis dispositio. – Chapitre XVI, Quomodo Archytas tetrachorda

dividat eorumque descriptio. – Chapitre XVIII, Quemadmo-dum tetrachordum

divisionem fieri dicat oportere.

Manuscrits ( De

Institutione Musica)

IXe siècle

Ms. Lat. 7200, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale, origine de Fleury- sur-Loire, IXe siècle, f. 1-93

Ms. Lat. 13955, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale., originaire de Corbie, IXe, Xe et XIe siècles, f.

60-105v

Ms. 14523, München,

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, originaire de Freising, daté de 854-875 (f. 49-117),

du Xe siècle (f. 1-48), du XIe siècle (f. 118-133), de 1279 (f. 134-159), f.

52v-117

Xe siècle

Ms. Cpv 55, Wien,

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Xe siècle, f. 1r-92v, De Institutione

Geometrica et Arithmetica, f. 93r-167r, De Institutione Musica

Ms. 531, Brugge,

Stadsbibliotheek, Xe ou du XIe siècle, f. 1-51 (f. 18, gloses de Gerbert,

Scholium ad Boethii Musicae Institutionis)

Ms. Class. 9, Bamberg,

Staatsbibliothek, origine allemande, Xe siècle, f. 49-150

Ms. Varia 1, id., origine

allemande, Xe siècle, f. 41v-42v

Ms. W 331, Köln,

Stadtarchiv, origine à cologne, Xe-XIe siècles, f. 1v-89

Ms. Lat. 7297, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale, originaire de Fleury- sur-Loire, Xe siècle, f. 55-92

Ms. Lat. 8663, id.,

originaire de Fleury-sur-Loire, Xe-XIe siècles, f. 51v-57

Ms. Nouv. Acq. Lat. 1618,

Paris, id., origine française, Xe-XIe siècles, f. 1-69

Ms. 260, Cambridge,

Corpus Christi College. Provenant de la Christ Church de Canterbury,

seconde moitié Xe siècle, f. 1-2v

Ms. Harley 3595, London,

British Library, origine allemande, provenant de diverses collections, Xe

siècle, f. 50-56v

Ms. Regulae Lat. 1283,

Roma, Biblioteca Vaticana, X-XIe siècle pour cette partie, f. 111r

XIe siècle

Ms. 5444/6, Bruxelles,

Bibliothèque Royale, originaire de l’abbaye bénédictine de St.-Pierre de

Gembloux, XIe siècle, f. 41v-98, f. 58 & 63, Scholium ad Boethii Musicae

Institutionis (I. II, c. 10 & 21)

Ms. 10114/6, id., origine

liégeoise, XIe siècle, f. 2v-75

Ms. 1988, Darmstadt

Hessische Landes-und Hochschulbibliothek, fin XIe (extraits) f. 169v-170v

Ms. 504, Karlsruhe,

Badische Landesbibliothek, origine allemande (Bamberg, Michelsberg), XIe et

XIIe siècles, f. 32rv

Ms. 14272, München,

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, origine allemande, originaire de St.-Emmeram de

Regensburg et de Chartres, XIe siècle, f. 1v-62 (glosé par Bernard de Chartres)

Ms. 18478, id.,

originaire de Tegernsee, daté de v. 1050-1075, f. 61-115

Ms. 18914, id.,

originaire de Tegernsee, daté de v. 1050-1075, f. 33-38 (fragment du livre IV)

Ms. Gud. Lat. 2° (cat

4376), Wolfenbüttel, Herzog-August-Bibliothek, originaire de St.-Ulrich et Afra

d’Augsburg, début XIe siècle, f. 1-50

Ms. Ripoll 42, Barcelona,

Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, originaire de l’abbaye bénédictine S.-Maria de

Ripoll, daté 1018-1046, f. 6v-38v & 42

Ms. 9088, Madrid,

Biblioteca Nacional, origine italienne, XIe ou XIIe siècles, Arithmétique: f.

3v-39, Musica: f. 41-39

Ms. Lat. 7202, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale de France, origine italienne ou française, XIe siècle,

f. 1-50r avec tonaire interpolé, f. 24-36

Ms. Latin 7361, id.,

origine normande, XIe-XIIe siècles f. 57-103

Ms. Lat 10275, id.,

XIe-XIIe siècles, f. 1v-77

Ms. Arundel 77, London,

British Library, origine allemande, fin XIe siècle, f. 6v-62

Ms. Pal. Lat. 1342, Roma,

Biblioteca Vaticana, XIe siècle, f. 1r

Ms. Reg. Lat. 1638, id.,

origine française, XIe- XIIe siècle, f. 1r

Ms. 364, Luxembourg,

Bibliothèque nationale, XIe siècle, f. 119

XIIe siècle

Ms. Cpv 51, Wien,

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, XIIe siècle, f. 4r-34v

Ms. 18397, Bruxelles,

Bibliothèque royale, XIIe siècle, f. 1v-46r, fragment de l’Arithmétique; f.

47r-59v, de Musica

Ms. Clm 13021, München, Bayerische

Staatsbibliothek, originaire de St.-Georg de Prüfering, XIIe et XIIIe siècles,

f. 97-150

Ms. 2, Alençon,

Bibliothèque municipale, originaire de l’abbaye de St. Evroult, daté de v. 1113

au plus tard

Ms. 237, Avranches,

Bibliothèque municipale, XIIe siècle, f. 1-76

Ms. 172, Cambrai,

Bibliothèque municipale, origine française, XIIe siècle, f. 16 vab

Ms. Lat. 2627, Paris,

Bibliothèque Nationale, origine française (Normandie), XIIe siècle, f. 84r

Ms. Lat. 5577, id.,

origine espagnole, XIIe siècle (Xe pour le f. 3)

Ms. 7203, id., originaire

de Fleury-sur-Loire, première moitié XIIe siècle, f. 8-104 (f. 6-7v, Boethius

vir eruditissimus)

Ms. Lat. 16201, id.,

origine française, fin XIIe siècle, f. 83-124v

Ms. R.15.22 (944),

Cambridge, Trinity College, origine anglaise, (provenant de Christ Church,

Canterbury), daté 1130-1160 ou 1175-1200 (?), f. 5-101v [livre I, 5r-27r; livre

II, 27v-48v; livre III, 48v-65v] [édition

TLM / Université d'Indiana : 5r-27r. ; 27v-48v ; 48v-65v ; 65v-91r ]

Ms. Lat. 19, Oxford,

Magdalen College, XIIe siècle

Ms. VIII. D. 12, Napoli,

Biblioteca nazionale, composé de trois liasses: I, f. 1-22v, fin XIIe siècle:

II, f. 23-32r, XIVe siècle; III, 33r-59v, XVe siècle, f. 1r

Ms. Ashburnham 1051,

Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, XIIe-XIIIe siècles, f. 96r

Ms. 194, Leiden,

Rijksuniversiteit Bibliotheek, origine liégeoise, XIIe siècle, f. 41-43,

monocorde

Ms. f. 9 (Admont 491),

Chicago (Il.), The Newberry Library, origine allemande ou autrichienne, XIIe

siècle, f. 1-62v

Ms. Kane 50, Philadelphia

(Pa.), University of Pennsylvania, Charles Patterson Van Pelt Library, origine

anglaise, XIIe-XIIIe siècles, f. 1-50, Arithmétique

XIIIe siècle

Ms. Cpv 2269, Wien,

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, XIIIe siècle, f. 153r-172v

Ms. 528, Brugge,

Stadsbibliotheek, origine flamande, XIIIe siècle et de la première moitié XIVe

siècle (f. 54v-59), f. 47-51

Ms. 66, Erlangen,

Universitätsbibliothek, XIIIe (f. 1-100v), XIVe (f. 102-109) et XVe siècles (f.

110-119), f. 35-84v

Ms. Clm 13021, München,

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, daté début XIIIe, f. 97-150

Ms. lat. 7185, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale, origine française, XIIIe siècle pour cette partie, f.

126-177r

Ms. 3, Saumur,

Bibliothèque municipale, peut-être originaire de Fleury-sur-Loire, XIIIe

siècle, f. 1-3 & 60, Arithmétique; f. 4-58, musica; f. 59-65, Boetius

erudissimus

Ms. 43 (XXV), Novara,

Biblioteca Capitolare, originaire de France, XIIIe siècle, f. 40-41r,

Commentaire de La Consolation (Restat ostendere quomodo resolvatur)

XIVe siècle

Ms. Lat. 18514, Paris,

Bibliothèque nationale, origine française, début XIVe siècle, f. 1-85

Ms. Harley 957, London,

British Library, origine anglaise, début XIVe siècle, f. 1-2 & 32rv

Ms. Regulae lat. 1146,

Roma, Biblioteca Vaticana, origine anglaise, XIVe siècle, f. 65v-66r

Ms. Regulae lat. 1315,

id., XIVe siècle, f. 1r

XVe siècle

Ms. 10162/6, Bruxelles,

Bibliothèque royale, XVe siècle

Ms. Clm 6006, München,

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, origine allemande, fin XVe siècle, f. 167-170

(extraits)

Ms. 98 th. 4°,

Regensburg, Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek, Proskesche- Musikbibliothek,

origine allemande, daté 1457-1476, f. 364-368& 382-385

Ms. O.I.I.9, El Escorial,

Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo, origine espagnole, XVe et XVIe

siècles, p. 85-86, De institutione I.2-V.19 en espagnol

Ms. Réserves 386, Z 461,

Paris Bibliothèque nationale, XVe siècle

Ms. II I 406 (Magliab.

XIX 19), Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale, origine italienne, XVe siècle, f.

6r-30v

Ms. l.V. 30, Siena,

Biblioteca comunale, origine italienne, XVe siècle, f. 144r-146r

Ms. G. IV. 31, Turino,

Biblioteca nazionale, f. 41r

Ms. Typ. 10, Cambrige

(Ma), Harvard Univeristy, The Houghton Library, origine italienne, XVe siècle,

f. 1-61

Ms. Add. 22315, London,

British Library, manuscrit d’origine italienne copié par Nicola Burzio, daté

d’après 1473 (Musica, extraits), f. 65v

Ms. Oxford, Bodleian

Library, Canonici Class. Lat. 273 (S.C. 19518), origine italienne, daté de

v. 1400

Ms. 1861, Kraków,

Biblioteka Jagiełłonska, origine supposée à Cracovie, daté de v. 1445, f. 8-90v

XVIe siècle

Ms. 4° Cod. Ms. 743,

München, Universitätsbibliothek, origine autrichienne supposée, daté 1500, f.

99-102v & 126

Ms. S. XXVI. 1, Cesena,

Biblioteca Malatestina, XVe siècle, f. 61v-132v

Dès la fin du XVe,

l’édition concernant Boèce est extrêmement abondante. La Bibliothèque nationale

conserve : 46 éditions de 1476 à 1499, 59 éditions de 1500 à 1549, 13 éditions

de 1550 à 1599, 18 éditions de 1600 à 1649, 9 éditions de 1650 à 1699, 4 éditions

de 1700 à 1750.

Arithmetica Boetii.

Augsburg, Erhard Ratdolt 1488 (44 exemplaires conservés)

Boetii Opera. Venezia, J.

de Forlivo et Gregorium Fratres, Venise 1491-1492 [V. I, p. 174-205: De

Musica] (99 exemplaires conservés) rééd. 1497-1499 (31 exemplaires conservés) ;

Basel, H. Petrum 1546 [préface de Glaréan, p. 1063-1162: De

musica. Copie pour l’édition à Paris Bibliothèque nationale] (18

exemplaires cponservés); rééd., Basel, H. Petri 1570 [p. 1371-1481: De musica]

(31 exemplaires conservés.)

BERNHARD MICHAEL &

BOWER CALVIN M. (*1938, édit.), Glossa maior in institutionem musicam Boethii

(I-IV). Dans «Veröffentlichungen der Musikhistorischen Kommission» (9),

Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, München 1993 [lxxvi-358 p.]; (10) 1994

[x-302 p. ; (11) 1996, [x-403 p.]; (12), Glossa maior in institutionem musicam

Boethii. Kommentar- und Registerband (en préparation). Cette collection

comprend l’édition de 55 manuscrits du IXe au XIIe siècle

–, Glossen

zur Arithmetik des Boethius. Dans «Scire litteras, Festschrift Bernhard

Bischoff zum 80. Geburtstag» Abhandlungen der Akademie München (n.F. 99),

München 1988, p. 23-34

BOWER CALVIN M. (*1938),

Boethius, The Principles of Music, an Introduction, Translation and Commentary

(thèse). George Peabody College 1967 [518 p.]

–, Traduction

anglaise (Fundamentals of music), introduction et notes. Éd. par Claude V.

Palisca, Music theory translation series, New Haven, Yale University Press

1989; London 1989

FRIEDLEIN GOTTFRIED,

Anicii Manlii Torquati Severini Boetii de institutione arithmetica libri duo;

De institutione musica libri quinque. Leipzig 1867 [ édition électronique TLM /

Université d'Indiana 1-72 ; 72-173 ; 173-225 ; 225-267 ; 268-300 ; 300-349 ; 349-371 ]

GODWIN JOSCELYN, The

Harmony of the Spheres. A Sourcebook of the Pythagorean Tradition in

Music. Rochester 1993 [trad. anglaise des passages relatifs à l’harmonie

des sphères, dans une optique ésotérique]

KRISCHER TILMAN,

Boethius: De institutione arithmetica, lib. I, cap. 1; lib. II, cap.

54. Dans Fr. Zaminer (éd.), «Geschichte der Musiktheorie» (3), Darmstadt

1990, p. 203-217 [trad.]

MARZI GIOVANNI, An. M. T.

Severini Boethii de institutione musica. Roma 1990 [éd. et trad. italienne]

MASI MICHAEL, Boethian

Number Theory: A Translation of the De Institutione Arithmetica. Dans

«Studies in Classical Antiquity» (6), Amsterdam 1983

MEYER

CHRISTIAN, Traité de la musique de Boèce, introduction, traduction et

notes. Brepols 2004.

MIGNE JACQUES-PAUL

(1800-1875), Patrologiae cursus completus. Serie latina [221 v.].

Petit Montrouge 1844-1855; Turnhout 1966, (63 et 64) [repris de Glarean: De

musica; livre I, p. 1167-1196; livre II, p. 1195-1224; livre III, p. 1225-1246]

[édition TLM / Université d'Indiana 1167-1196

; 1195-1224 ; 1223-1146 ; 1245-1286 ; 1285-1300 ]

PIZZANI UBALDO, [Bedae

presbyteri] musica theorica sive scholia in Boethi de instititutione musica

libros quinque. Dans «Romanobarbarica» (5) 1980, p. 299-361

PAUL OSCAR, Boethius:

Fünf Bücher über Musik. Leipzig 1872; Hildesheim, Olms 1985 [trad.]

BIELER LUDWIG, Anicii

Manlii Boethii Philosophiae consolatio. Corpus Christianorum (94), Turnholti,

Brepols 1957 [xxviii-124 p., trad., française: Consolation de la philosophie.

Paris, Rivages 1989]

BRANDT S., Porphyre,

Isagogen. Dans «Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum» (48), Vienne 1906

HOCHADEL MATTHIAS,

Edition, Kommentar und Übersetzung der Boethius-Kommentare Oxford, Bodleian

Library, Bodley 77, und Oxford, All Souls College XC (thèse). Freiburg

[dir. Christian Berger]

MEISER KARL (CAROLUS,

1843-1912), Commentaries on Aristotele’s De interpretatione: Amicii Manilii

Severinii Boethii commentarii in librum Peri Hermeneias. Teubner, Leipzig

1877-1880; New York, Garland 1987 [2 v., 22 cm]

OBERTELLO LUCA, De

hypotheticis syllogismis. Paideia Editrice, Brescia 1969

STEWART HUGH FRASER

(1863-1948) & RAND EDWARD KENNARD (1871-1945, trad.), Theological Tractates

(Opuscula sacra). Loeb Classic Library, London 1918

STUMP ELEONORE, De

differentiis topicis. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (N.Y.) 1978

Études musicales

ATKINSON CHARLES M., On

the Interpretation of Modi, quos abusive tonos dicimus. Dans P. J.

Gallacher & H. Damico (éd.), «Hermeneutics and Medieval Culture», Albany

1989, p. 148

BARBERA C. ANDRÉ,

Arithmetic and Geometric Divisions of the Tetrachord. Dans «Journal of Music

Theory» (21, 2) 1977, p. 294-323

BELLERMANN FRIEDRICH, Die

Tonleitern und Musiknoten der Griechen. Berlin 1847; Wiesbaden 1969

BERNHARD MICHAEL,

Wortkonkordanz zu Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, De institutione musica.

Dans «Veröffentlichungen der Musikhistorischen Kommission» (4), Bayerische

Akademie der Wissenschaften, München 1979 [viii-814 p.,]

–, Glosses

on Boethius De institutione musica. Dans A. Barbera (éd.), «Music Theory and

its Sources», Notre Dame Conferences in Medieval Studies (1), Notre Dame 1990,

p. 136-149

–, Ex

gentium vocabulis sortiti. Zu den Namen der Kirchentonarten. Dans W. Pass &

A. Rausch (éd.), «Mittelalterliche Musiktheorie in Zentraleuropa», Musica

mediaevalis Europae occidentalis (4), Tutzing 1998, p. 7-19

–, Boethius

im mittelalterlichen Schulunterricht. Dans M. Kintzinger & S. Lorenz

& M. Walter (éd.), «Schule und Schüler im Mittelalter», Beihefte zur Archiv

für Kulturgeschichte (42) 1996, p. 11-27

–, Überlieferung

und Fortleben der antiken lateinischen Musiktheorie im Mittelalter. Dans

Friedrich Zaminer (éd.), «Geschichte der Musiktheorie» (3), Darmstadt 1990, p.

1-35

BOFILL I SOLIGUER JOAN,

La Problemàtica del tractat De institutione musica de Boeci. Dans «Aurea

Saecula» (8), Barcelona 1993

BOWER CALVIN M. (*1938),

Boethius and Nicomachus: An Essay Concerning the Sources of De institutione

Musica. Dans «Vivarium» (16) 1978, p. 1-45

–, Boethius’

De institutione musica. A Handlist of Manuscripts. Dans «Scriptorium» (42)

1988, p. 205-251

–, Die

Wechselwirkung von philosophia mathematica und musica in der karolingischen

Rezeption der Institutio musica von Boethius. Dans F. Hentschel (éd.), «Musik

und Geschichte der Philosophie und Naturwissenschaft im Mittelalter», Studien

und Texte zur Geistesgeschiche des Mittelalters (62), Leiden 1998, p. 163-183

–, The

Modes of Boethius. Dans «Journal of Musicology» (3) 1984, p. 252-263

–, The

Role of Boethius’ De institutione musica in the Speculative Tradition of

Western Musical Thought. Dans M. Masi (éd.), «Boethius and the Liberal Arts»,

Utah Studies in Litteratre and Linguistic (18), Bern 1981, p. 157-174

BRAGARD ROGER, Boethiana:

Études sur le De institutione musica de Boèce. Dans «Hommage à Charles van den

Borren», Anvers 1945, p. 84-139

–, Les

sources du De institutione musica de Boèce (thèse). Liège 1926

–, L’harmonie

des sphères selon Boèce. Dans «Speculum» (4) 1929, p. 206-213

BRAMBACH WILHELM, Die

Musiklitteratur des Mittelalters bis zur Blüthe der Reichenauer Sängerschule.

Dans «Mittheilungen aus der Grossherzoglichen Badischen Hof- und

Landesbibliothek» Karlsruhe 1883, p. 2-4

BROWNE ALMA C., The a-p

System of Letter Notation. Dans «Musica Disciplina» (35) 1981, p. 5-54

CALDWELL JOHN, The De

Institutione Arithmetica and the De Institutione Musica. Dans M. Gibson (éd.),

«Boethius. His Life, Thought and Influence», Oxford 1981, p. 135-154

CESARI GAETANO, Tre

tavole di strumenti in un Boezio del X secolo. Dans «Studien zur

Musikgeschichte», Festschrift Guido Adler zum 75. Geburtstag, Wien-Leipzig

1930, p. 26-28

CHADWICK HENRY, Boethius.

The Consolations of Music, Logic, Theology, and Philosophy. Oxford 1983

CHAILLEY JACQUES (1910-1999),

Henri Potiron, Boèce théoricien de la musique Grecque, Paris 1961. Dans «Revue

de Musicologie» (47) 1961, p. 207-208 [recension]

CHAMBERLAIN DAVID S.,

Anticlaudianus, III. 412-445, and Boethius’ De musica. Dans «Manuscripta»

(13) 1969, p. 1 67-169

–, Philosophy

of Music in the Consolation of Boethius. Dans «Speculum» (45) 1970, p.

80-7

CHAMBERS G. B., Boethius.

De musica. An interpretation. Dans «Studia patristica» (3)

CHAMPIGNEULLE BERNARD,

Histoire de la musique. Collection «Que sais-je?» (40), PUF, Paris 1964, p. 9

CHARTIER YVES, Hucbald de

Saint-Amand et la notation musicale. Dans M. Huglo (éd.), «Musicologie

médiévale, notations et séquences», Paris 1987, p. 145-155

COHEN DAVID E., Boethius

and the Enchiriadis theory: The metaphysics of consonance and the concept of

organum (thèse). Brandeis University 1993

CROCKER RICHARD L.,

Alphabet Notations for Early Mediaeval Music. Dans «Saints, Scholars and

Heroes» Studies in Honour of Ch. W. Jones, Ann Arbor 1979, (2), p. 80

DAHLHAUS CARL

(1928-1989), Zur Theorie des frühen Organums. Dans «Kirchenmusikalisches

Jahrbuch» (42) 1958, p. 47-52

DARMSTÄDTER BEATRIX, Das

präscholastische Ethos in patristisch-musikphilosophischem Kontext. Dans

«Musica mediaevalis Europae occidentalis» (1), Tutzing 1996

DEASON WILLIAM DAVID, A

taxonomic paradigm from Boethius’ De divisione applied to the eight modes of

music (thèse). Ohio State University 1992

DEHNERT EDMUND JOHN,

Music as liberal in Augustine and Boethius. Dans «Arts libéraux et

philosophie au Moyen Age», Actes du 4. Congrès International de Philosophie

Médiévale, Montréal 1967. Paris 1969, p. 987-991

DUCHEZ MARIE-ÉLISABETH,

Jean Scot Érigène premier lecteur du De institutione musica de Boèce? Dans

«Eriugena. Studien zu seinen Quellen», Vorträge des III. International

Eriugena-Colloquiums Freiburg 1979, Heidelberg 1980, p. 165-187

EDMISTON JEAN, Boethius

on Pythagorean Music. Dans «The Music Review» (35) 1974, p. 179-184

EITNER ROBERT

(1832-1905), Die Kirchentonarten in ihrem Verhältnisse zu den griech. Tonleitern,

nebst ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklung. Dans «Monatshefte für Musikgeschichte»

(4) 1872, p. 169-184, 189-206

ERICKSON RAYMOND,

Eriugena, Boethius and the Neoplatonism of Musica and Scolica enchiriadis. Dans

«Musical Humanism and its Legacy: Essays in Honor of Claude V. Palisca»,

Stuyvesant (NY) 1992, p. 53-78

EVANS GILLIAN R., A

Commentary on Boethius’s Arithmetica of the Twelfth or Thirteenth Century. Dans

«Annals of Science» (35) 1978, p. 131-141

–, Introductions to

Boethius’s Arithmetica of the Tenth to the Fourteenth Century. Dans «History of

Science» (16) 1978, p. 22-41

GERCMAN EVGENIJ, Boecij i

evropejskoe muzykoznanie. Dans «Srednie veka» (48) 1985, p. 233-43

GÉROLD THÉODORE, Histoire

de la musique des origines à la fin du XIVe siècle. H. Laurens Paris 1936,

p. 45, 129, 166, 205, 222-226, 258

GIBSON MARGARET (éd.),

Boethius. His Life, Thought and Influence. Oxford 1981

GOMBOSI OTTO, Studien zur

Tonartenlehre des frühen Mittelalters. Dans «Acta Musicologica» (10) 1938, p.

149-174; (11) 1939, p. 128-135; (12) 1940, p. 21-52

GUSHEE LAWRENCE A., C. M.

Bower, A. M. S. Boethius, De institutione musica, New Haven 1989. Dans «Journal

of Music Theory» (38) 1994, p. 328-343 [recension]

HEBBORN BARBARA, Die

Dasia-Notation. Dans «Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik»

(79), Bonn 1995, p. 76

HELLER BRUNO, Boethius im

Lichte der frühmittelalterlichen Musiktheorie (thèse). Wien 1939

HELLGARDT ERNST, Zum

Problem symbolbestimmter und formalästhetischer Zahlenkomposition in

mittelalterlicher Literatur. Münchener Texte und Untersuchungen zur deutschen

Literatur des Mittelalters. (45), München 1973, p. 28

HOCHADEL MATTHIAS, Zur

Rezeption der Institutio musica von Boethius an der spätmittelalterlichen

Universität. Dans F. Hentschel (éd.), «Musik und die Geschichte der Philosophie

und Naturwissenschaft im Mittelalter. Studien und Texte zur Geistesgeschichte

des Mittelalters » (62), Leiden 1998, p. 187-206

HOLBROOK AY KUIAN, The

concept of musical consonance in Greek antiquity and its application in the

earliest medieval descriptions of polyphony (thèse). University of Washington

1983

HUGLO MICHEL, M. Masi,

Manuscripts Containing the De Musica of Boethius. Dans «Manuscripta» (16)

1972, p. 89-95. Dans «Scriptorium» (27) 1973, p. 401-402 [recension]

ILLMER DETLEF, Die

Zahlenlehre des Boethius. Dans Fr. Zaminer (éd.), «Geschichte der

Musiktheorie» (3), Darmstadt 1990, p. 219-252

KÁRPÁTI ANDRÁS,

Translation or Compilatio? Contribution to the Analysis of Sources of Boethius’

De institutione musica. Dans «Studia Musicologica» (29) 1987, p. 5-35

KLEIN J., Zu Boethius De

musica. Dans «Rheinisches Museum für Philologie» (23) 1868, p. 703-704

KLINKENBERG HANS M., Der

Zerfall des Quadriviums in der Zeit von Boethius bis zu Gerbert von

Aurillac. Dans «Gesellschaft für Musikforschung», Kongress-Bericht,

Hamburg 1956, Kassel-Basel 1957, p. 129-133

KUNZ LUCAS, Die

Tonartenlehre des Boethius. Dans «Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch» (31-33)

1936-1938, p. 5-24

LOCHNER FABIAN, Die Ars

musica im Willibrorduskloster zu Echternach. Dans G. Kiesel & J. Schroeder

(éditeurs), «Willibrord, Gedenkgabe zum 1250. Todestag», 1990, p. 150-165

–, Un

manuscrit de théorie musicale provenant d’Echternach (début du XIe siècle):

Luxembourg, B. N. I. 21. Dans «Scriptorium» (41) 1987, p. 256-261

MACHABEY ARMAND, La

notation musicale. Collection «Que sais-je?» (514), PUF, Paris 1971, p.

18, 20, 29, 48, 49, 54

MARKOVITS MICHAEL, Das

Tonsystem der abendländischen Musik im frühen Mittelalter. Dans «Publikationen

der Schweizerischen Musikforschenden Gesellschaft» (II/30), Bern-Stuttgart

1977, p. 13, 17-27, 29, 31-33, 37-42, 60, 68-74, 77, 82, 88, 91, 93, 101, 107,

109-111

MASI MICHAEL, Boethius

and the Iconography of the Liberal Arts. Dans «Latomus» (33) 1974, p. 57-75

–, The

Influence of Boethius De Arithmetica on Late Medieval Mathematics. Dans M. Masi

(éd.), «Boethius and the Liberal Arts», Bern-Frankfurt-Las Vegas 1981, p. 81-95

–, Manuscripts

Containing the De musica of Boethius. Dans «Manuscripta» (15) 1971, p.

88-97

MASSERA GIUSEPPE,

Severino Boezio e la scienza armonica tra l’antichità ed il medio evo. Parma

1976

MEYER CHRISTIAN, Un

abrégé universitaire des deux premiers livres du De institutione musica de

Boèce. Dans «Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Age» (65)

1998, p. 91-121

MIEKLEY GUALTHERUS, De

Boethii libri de musica primi fontibus (thèse). Jena 1898

MONTICO MARIA GIOVANNI,

Il valore psicagogico della musica nel pensiero di S. Agostino e di altri

filosofi cristiani (Boezio, Cassiodoro e S. Bonaventura). Dans «Miscellanea

Francescana» (38) 1938, p. 398-410

NALLI PAOLO, Regulae

contrapuncti secundum usum regni Siciliae. Dans «Archivio Storico per la

Sicilia Orientale», Seconda Serie 29 (2-3) 1933, p. 277-292

NISHIMAGI SHIN,

L’influence de Boèce sur le «De musica» d’Hucbald de Saint-Amand. Bigaku

(47) 1996, p. 48-58

OPPEL HERBERT, KANON. Zur

Bedeutungsgeschichte des Wortes und seinen lateinischen Entsprechungen, 2. Die

Bedeutung des Wortes in der Musiklehre. Dans «Philologus» (sup.-Band 30/4)

1937, p. 17-20

PALISCA CLAUDE V.,

Boethius in the Renaissance. Dans A. Barbera (éd.), «Music Theory and its

Sources», Notre Dame Conferences in Medieval Studies (1), Notre Dame 1990, p.

259-280

PIETZSCH GERHARD, Die

Musik im Erziehungs- und Bildungsideal des ausgehenden Altertums und frühen

Mittelalters. Dans «Studien zur Geschichte der Musiktheorie im Mittelalter»

(II), Halle 1932 (rééd. Darmstadt 1968)

–, Die

Klassifikation der Musik von Boetius bis Ugolino von Orvieto. Dans «Studien zur

Geschichte der Musiktheorie im Mittelalter» (I), Halle 1929

(rééd. Darmstadt 1968)

PIZZANI UBALDO, Aureliano

di Réôme e la riscoperta del De institutione musica di Boezio. Dans

«Esercizi» (2) 1979, p. 7-29

–, The

Influence of the De Institutione Musica of Boethius up to Gerbert d’Aurillac: A

Tentative Contribution. Dans M. Masi (éd.), «Boethius and the Liberal Arts»,

Bern-Frankfurt-Las Vegas 1981, p. 97-156

–, Studi

sulle fonti del De institutione musica di Boezio. Dans «Sacris Erudiri» (16)

1965, p. 5-164

–, Uno

pseudo-trattato dello pseudo-Beda. Dans «Maia» (9) 1957, p. 36-48

POTIRON HENRI, Boèce

théoricien de la musique grecque. Dans «Travaux de l’Institut Catholique de

Paris» (9), Bloud et Gay, Paris 1961

–, La

notation grecque et Boèce. Dans «Petite histoire de la notation antique», Paris

1951

RUELLE CHARLES-ÉMILE

(1833-1912), Le musicographe Alypius corrigé par Boèce. Académie des

Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Année 1894, 4e

série (22), p. 458-468

RUINI CESARINO, Alcune

osservazioni sulla Practica artis musice di Amerus. Dans «L’Ars Nova Italiana

del Trecento» (5), Certaldo 1985, p. 219

SACHS KLAUS-JÜRGEN,

Boethius and the Judgement of the Ears: A Hidden Challenge in Medieval and

Renaissance Music. Dans Ch. Burnett, M. Fend & P. Gouk (éd.), «The Second

Sence», London 1991, p. 169-198

SCHEPSS G., Zu den

mathematisch-musikalischen Werken des Boethius. Dans «Festschrift Wilhelm von

Christ zum 60. Geburtstag», München 1891, p. 107-113

SCHRADE LEO (1903-1964),

Das Bildungsethos in der Musikerziehung. Dans «Die Musikerziehung» (8) 1931, p.

33-46, 76-80

–, Music

in the Philosophy of Boethius. Dans «Musical Quarterly» (33) 1947, p. 188-200

–, Das

propädeutische Ethos in der Musikanschauung des Boethius. Dans Leo Schrade, «De

Scientia Musicae Studia atque Orationes», Bern-Stuttgart 1967 p. 35-75

–, Die

Stellung der Musik in der Philosophie des Boethius als Grundlage der

ontologischen Musikerziehung. Dans Leo Schrade, «De Scientia Musicae Studia

atque Orationes», Bern-Stuttgart 1967, p. 76-112

–, G.

Pietzsch Die Klassifikation der Musik von Boetius bis Ugolino von Orvieto,

Halle 1929. Dans «Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft» (13) 1930-1931, p. 570-577

[recension]

SINCLAIR K. V., Eine alte

Abschrift zweier Musiktraktate. Dans «Archiv für Musikwissenschaft» (22) 1965,

p. 52-55

SMITS VAN WAESBERGHE

JOSEPH, Problèmes de compréhension et de traduction dans les traités consacrés

au quadrivium par A. M. T. S. Boèce. Dans «Liber amicorum Roger Bragard», Revue

Belge de Musicologie (34-35) 1980-1981, p. 16-21

SUDAK BOGUSLAW,

Matematyczny aspekt boecjanskiej koncepcji muzyki. Dans «Muzyka» (31/1) 1986,

p. 35-50

–, Praktyczny

aspekt boecjanskiej koncepcji muzyki. Zeszyty naukowe, Akademia Muzyczna

im. St. Moniuszki (25) 1986, p. 211-233

–, Problematyka

filozoficzna w pogladach Boecjusza na muzyke. Zeszyty naukowe: Akademia

Muzyczna im. St. Moniuszki (24) 1985, p. 41-67

SULLIVAN BLAIR, Nota and

Notula: Boethian Semantics and the Written Representation of Musical Sound in

Carolingian Treatises. Dans «Musica Disciplina» (47) 1993, p. 71-97

TRAUB ANDREAS, MICHAEL

BERNHARD & CALVIN M. BOWER, Glossa maior in institutionem musicam Boethii

(I). Dans «Veröffentlichungen der Musikhistorischen Kommission» (9), Bayerische

Akademie der Wissenschaften, München 1993. Dans «Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch» (29/2)

1994, p. 152-153 [recension]

VIKÁRIUS LÁSZLÓ, A

Boethius-Fragment: New Source for Research into the Theoretical Musical

Teaching in Medieval Hungary. Dans «Cantus Planus », Société

Internationale de Musicologie, troisième conférence de Tihany (1988), Budapest

1990, p. 245-256

VOGEL MARTIN, Boetius und

die Herkunft der modernen Tonbuchstaben. Dans «Kirchenmusikalisches

Jahrbuch», (46) 1962, p. 1-19

WAGNER PETER, Zur

Musikgeschichte der Universität. Dans «Archiv für Musikwissenschaft» (3) 1921,

p. 1

WANGERMÉE ROBERT, La

musique flamande dans la société des XVe et XVIe siècles. Édition Arcade

Bruxelles 1965, p. 19-22, 27, 31, 47, 68, 89

WHITE ALISON, Boethius in

the Medieval Quadrivium. Dans M. Gibson (éd.), «Boethius. His Life,

Thought and Influence», Oxford 1981, p. 164, 185-186, 199, 204

WILLE GÜNTHER, Musica

Romana. Die Bedeutung der Musik im Leben der Römer. Amsterdam 1967, p. 10, 13,

301, 594, 599, 654, 656, 704, 721

WITKOWSKA-ZAREMBA

ELZBIETA, Pojecie muzyki w Krakówskich traktatach «Musicae planae» i polowy XVI

wieku. Dans «Muzyka» 1984, p. 3-22

Études philosophiques et

littéraires

BARNES JONATHAN, Boethius

and the Study of Logic, Boethius: His Life, Thought and Influence. Oxford 1981

[éd. Margaret Gibson] p. 73-89

BARK W., The Legend of

Boethius martyrdom. Dans «Speculum» (21) 1946, p. 213-17

–, Theoderic.

Boethius: vindication and apology. Dans «American Historical Review» (49) 1944,

p. 410-26

BARRETT HELEN MARJORIE,

Boethius. Some aspects of his times and work. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

1940

BIELER LUDWIG, Consolatio

philosophiae. Turnhout 1957

BARNISH S. J. B.,

Maximian, Cassiodorus, Boethius, Theodahad: Poetry, Philosophy and Politics in

Ostrogothic Italy. Dans «Nottingham Medieval Studies», 1990

BONNAUD R., L’éducation

scientifique de Boèce. Dans «Speculum» (4) 1929, p. 198-206

BRUYNE EDGARD DE, Études

d’esthétique médiévale. Brugge 1946, p. 310; Genève, Slatkine 1975; Paris,

Albin Michel 1998

COURCELLE Pierre, Boèce

et l’école d’Alexandrie. Dans «Mélanges d’histoire et d’archéologie» École

Française de Rome (52e année) 1935, p. 185

–, Étude

critique sur les commentaires du De consolatione de Boèce. Dans «Archives

d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge», 1939

–, La

Consolation de Philosophie dans la tradition littéraire. Antécédents et

postérité de Boèce. Dans «Études augustiniennes», Paris 1967

–, Les

lettres grecques dans l’Occident de Macrobe à Cassiodore. Paris 1948 (en

anglais: Late Latin Writers and Their Greek Sources. 1969)

GIBSON MARGARET (dir.),

Boethius: His Life, Thought and Influence. Oxford 1981

GRUBER ALBION, Kommentar

zu Boethius De Consolatione Philosophiae. De Gruyter, Berlin 1978

HADOT PIERRE, Forma

essendi. Dans «Les Études classiques» (38) 1970, p. 225-239

–, Un

fragment du commentaire perdu de Boèce sur les Catégories d’Aristote dans le

Codex Bernensis 363. Dans «Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du

Moyen-Âge» (26) 1959, p. 11-27

KIRKBY HELEN, The Scholar

and his Public. Dans «Boethius: His Life, Thought and Influence», ed. Margaret

Gibson, Oxford 1981, p. 44-69

MCKINLAY, A. P.,

Stylistic Tests and the Chronology of the Works of Boethius. Dans «Harvard

Studies in Classical Philology» (18) 1907, p. 123-56

MASI MICHAEL, Boethian

Number Theory: A Translation of the De Institutione Arithmetica. Dans «Studies

in Classical Antiquity» (6), Amsterdam 1983

MATTHEWS JOHN, Anisius

Manlius Severinus Boethius. Dans Margaret Gibson (éd.), «Boethius: His Life,

Thought and Influence», Oxford 1981, p. 15-43

MOORHEAD JOHN, Boethius

and Romans in Ostrogothic service. Dans «Historia» (27) 1978, p. 604-12

MORTON CATHERINE,

Boethius in Pavia: the Tradition and the Scholars. Dans «Congresso

internazionale di studi Boeziani: Atti» Roma 1981, p. 49-58

KAYLOR NOEL HAROLD, The

Medieval Consolation of Philosophy. New York 1992 [bibliographie]

OBERTELLO LUCA, Severino

Boezio, Accademia Ligure di Scienze e Lettere, Gênes 1974 [2 v., abondante

bibliographie]

–, Boezio

le scienze del quadrivio e la cultura medievale. Atti della Accademia Ligure di

Scienze e Lettere (28) 1972, p. 152-170

– (dir.), Atti del

Congresso Internazionale di studi boeziani (Pavie, 5-8 oct. 1980), Herder, Roma

1981

PIZZANI UBALDO, Boezio

consulente tecnico al servizio dei re barbarici. Dans «Romanobarbarica»

(3) 1978, p. 189-242

REISS EDMUND, The Fall of

Boethius and the Fiction of the Consolatio Philosophiae. Dans «Codex

Justinianus» (77) 1981, p. 37-47

RUSSELL BERTRAND, History

of Western Philosophy. London 1961, p. 366-370

WHITE ALISON, Boethius in

the Medieval Quadrivium. Dans «Boethius: His Life, Thought and Influence»

Oxford 1981 [ed. Margaret Gibson] p. 162-205

Citations (traduction

Potiron)

Sur la musique : Avant

tout, la musique est une science qui touche à la morale. Nous perce-vons les

qualités du son et leurs différences, mais nous éprouvons du plaisir lorsqu’ils

sont bien ordonnés, une sorte d’angoisse lorsqu’ils sont incohérents. L’âme du

monde est intimement liée à la musique qui purifie ou corrompt les moeurs. Elle

peut avoir une mauvaise influence sur les enfants. (Platon, la République).

Elle a une influence sur les états violents, elle peut guérir les maladies

graves. Les sens peuvent nous tromper. Il faut se fier à la raison. La

perception doit être contrôlée par la raison. (Platon, la République VII, 530)

Le musicien: Il y a la

raison qui conçoit et la main qui exécute. Il est plus important de savoir que

de faire. Supériorité de l’esprit sur le corps. L’exécutant n’est qu’un

serviteur. Combien plus belle est la science de la musique fondée sur la

connaissance raisonnable que sur la réalisation matérielle. (Ch. 35)

Le son: C’est la

consonance qui régit la conduite de la mélodie. La consonance suppose le son.

Il n’y a pas de son sans impulsion ni percussion de l’air, sans mouvement qui

la provoque. Le son est la percussion indivise de l’air qui parvient à nos

oreilles. Les mouvements sont plus ou moins rapides, plus ou moins lents, plus

ou moins fréquents, plus ou moins rares. La rapidité engendre l’aigu. La

lenteur engendre le grave. Une corde tendue engendre l’aigu. Une corde détendue

engendre le grave. Tendue, elle revient vite à son point de départ. Détendue,

elle revient lentement à son point de départ. Mais il n’y a pas de continuité

de grave à aigu. Le son est continu ou discontinu. Continu dans la

conversation, la lecture, les discours, parce qu’il ne s’arrête pas à l’aigu ou

au grave, parce qu’il glisse de l’un à l’autre sans qu’on puisse fixer de

rap-port précis. Il est discontinu dans le chant ou chaque degré est

suffisamment distingué.

Consonances: Quand deux

sons, l’un plus aigu, l’autre plus grave sont entendus ensemble de façon

agréable à l’oreille. (I, 8) La douzième (quinte redoublée) rapport triple, 3/1

- l’octave est la plus parfaite, 2/1 - la quinzième (double octave) bis

diapason, 4/1 - la quinte (diapente) ses-quialtere, 3/2 - la quarte

(diatessaron) sesquitierce, 4/3 - Au dessus de 4, il n’y a pas de conso-nance.

La quarte redoublée de rapport superpartiel (8/3) n’est pas une consonance

(avis contraire chez Ptolémée)

Dissonances : Son dur et

désagréable, comme si chacun voulait se séparer de l’autre. Mais il faut

prendre garde à sa perception et se fier à la raison et aux chiffres.

Les marteaux de Pythagore

: Comme Gaudence et Nicomaque, Boèce reprend la légende relative à la

découverte des consonances par Pythagore: C’est en écoutant un forgeron

travailler que Pythagore s’interroge sur l’harmonie rendue par les marteaux

frappant les enclumes: 2 son-nent l’octave 2 sonnent la quinte ou la quarte 1

est dissonant. Il fait peser les marteaux : Le plus lourd pèse 12 - Le plus

léger pèse 6 - Le quatrième pèse 8 - Le cinquième pèse 9 - 12 et 6 son-nent

l’octave - 12 et 8 ou 9 et 6 sonnent la quinte - 12 et 9 ou 8 et 6 sonnent la

quarte - 9 et 8 sonnent le ton (Différence entre quinte et quarte). Ainsi se

définit la proportion harmonique ou proportion dorée: 6, 8, 9, 12 ou 12, 9, 8,

6. Entré chez lui, Pythagore fixe deux cordes sembla-bles à un clou et y

attache des poids différents. Il obtient les mêmes résultats numériques que

dans la forge.

Les rapports

intervalliques : Il y a cinq espèces d’inégalités : 1- Par multiplicité, l’un

des ter-mes du rapport étant double triple, quadruple, 2/1, 3/1, 4/1 - 4/2,

6/2, 8/2. 2- Par superbipar-ticularité. Le chiffre le plus élevé de la

proportion dépasse l’autre d’une unité, 3/2, 4/3, 9/8 - sesquialtere 3/2

(altere = 2) - sesquitierce 4/3 - sesquioctave 9/8 - 3- Superpartiens. un des

deux termes est plus élevé que l’autre de 2 unités, 5/3, 6/4 - superbipartien:

3 unités: 7/4 - 4- Multi-plicité et superparticularité. Le nombre le plus grand

contient 2 fois, 3 fois le plus petit et une certaine partie de ce dernier.

Double sesquialtere 5/2 = (2 + 2 + [2(1/2)] - Double sesquitierce 7/3 = (3 + 3+

[3(1/3)] - 5- multiplex superpartiens. Double superpartien 8/3 (2 x 2 + 2) -

Triple superpartien 11/3 (3 x 3 + 2)

La division de la musique

: Boèce divise la musique en trois espèces : 1- La musique du monde (cosmique)

- 2- La voix humaine - 3- La musique instrumentale. La musique ou harmo-nie

cosmique se manifeste dans le ciel lui même, dans l’union des quatre éléments