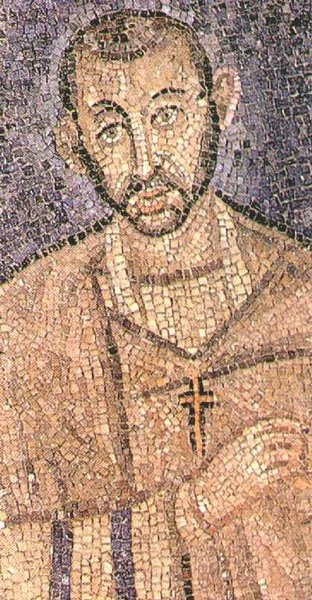

Sant'

Ambrogio, Sacello di San Vittore in ciel d'oro, mosaici del 450-500

Milan (Italy). Saint

Ambrose. Detail from the dome of the

shrine of San Vittore in ciel d'oro, now a chapel

of Sant'Ambrogio basilica. This images

could be based on an actual portrait of Ambrose. The building dates back to the

4th century, the mosaic to the second half of the 5th century. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, April 25 2007.

San Ambrosio, mosaico in iglesia St. Ambrogio, Milano

Saint Ambroise de Milan

Évêque et Docteur de l'Église (+ 397)

Cet avocat célèbre avait une si grande personnalité qu'il devint gouverneur de la province de Milan. Il découvre alors Jésus-Christ. Il n'est encore que catéchumène lorsque, de passage dans sa ville, il est élu évêque par acclamation du peuple. Il est alors immédiatement baptisé, ordonné prêtre, consacré évêque en peu de temps. Saint Ambroise est un véritable évêque, soucieux de la rectitude de la foi et de la paix sociale. Ses relations avec les empereurs successifs (qui favorisent tantôt les catholiques, tantôt les hérétiques ariens) sont mouvementées. En 390, l'empereur Théodose fait massacrer toute une partie de la population de Thessalonique pour arrêter des émeutes. Pour cette raison, saint Ambroise lui refusera l'accès de son église à Milan, exigeant qu'il se soumette d'abord à la pénitence publique de l'Église. L'empereur, subjugué, obéit et, après des mois de pénitence, Théodose ne communie plus dans le sanctuaire avec les prêtres (selon le privilège impérial), mais au milieu des laïcs.

Saint Augustin doit, en partie à saint Ambroise, sa conversion, car il épiait ses sermons en cachette, écoutait sa pensée, admirait la parole de ce grand orateur. Saint Ambroise avait un grand souci de belles liturgies. Il introduisit dans l'Église latine l'usage grec de chanter des hymnes qui étaient à la fois des prières, des actions de grâce et des résumés du dogme. Il en composa plusieurs que nous chantons encore aujourd'hui "Aeterne rerum Conditor" - "Dieu créateur de toutes choses".

Patron des apiculteurs, il est parfois représenté avec une ruche en paille tressée.

C'est évidemment d'abord à la sagesse et à l'autorité de l'administrateur, sans doute aussi à son sens pédagogique (il fut "l'inventeur" du chant populaire liturgique pour aider à la prière et à la mémorisation des vérités de foi) que se réfère le corps administratif et technique des armées en choisissant saint Ambroise comme saint protecteur. (Diocèse aux Armées françaises)

Un portrait de saint Ambroise de Milan.

Celui qui est considéré comme un des plus grands Pères de l'Église (339-397) fut initié aux études bibliques par Origène. "Il a transposé dans le contexte culturel latin -a expliqué le Pape- la méditation de l'Ecriture, inaugurant en occident la Lectio Divina, qui inspira sa prédication et son œuvre, toute orientée sur l'écoute" de la Parole divine.

Il enseigna tout d'abord aux catéchumènes "l'art de vivre bien afin d'être bien préparés aux grands mystères christiques". Sa prédication partant "de la lecture des Livres sacrés pour vivre en conformité à la Révélation".

"Il est évident -a précisé le Saint-Père- que le témoignage personnel du prédicateur et son exemple pour la communauté conditionnent l'efficacité de sa démarche. C'est pourquoi le mode de vie et la réalité de la Parole vécue sont déterminants".

Puis Benoît XVI a rappelé le témoignage de saint Augustin dont la conversion fut le fruit des "belles homélies" d'Ambroise entendues à Milan, mais aussi "du témoignage qu'il donnait et de celui de l'Église milanaise qui ne faisaient qu'un en priant et chantant d'une seule voix". L'Évêque d'Hippone raconte également sa surprise de voir Ambroise lire mentalement en privé les Écritures, "alors qu'à l'époque leur lecture devait être faite à voix haute afin d'en faciliter la compréhension".

Dans ce mode de lecture, a souligné le Pape, "où le cœur s'efforce de comprendre la Parole de Dieu, on entrevoit la méthode catéchistique de saint Ambroise. Complètement assimilée, l'Écriture suggère les contenus à diffuser en vue de la conservation des cœurs... De fait, la catéchèse est inséparable du témoignage de vie".

"Qui éduque dans la foi ne saurait courir le risque de sembler un acteur interprétant un rôle". Le prédicateur doit, "à l'exemple de Jean, appuyer sa tête sur le cœur de son maître, adoptant son mode de pensée, de parler et d'agir".

Ambroise de Milan mourut la nuit du Vendredi Saint les bras en croix, "exprimant dans cette attitude sa participation mystique à la mort et à la résurrection du Seigneur. Ce fut là son ultime catéchèse". Sans paroles et dans le silence des gestes il continua de témoigner.

Source: VIS 071024 (390) le 24 octobre 2007, Benoît XVI durant l'audience générale.

- vidéo: Saint Ambroise de Milan, KTOTV

Le 7 décembre, mémoire de saint Ambroise, évêque de Milan et docteur de

l'Église. Il s'endormit dans le Seigneur le 4 avril 397 dans la nuit sainte de

Pâques, mais on l'honore principalement en ce jour, où, encore catéchumène, il

fut, en 374, appelé à gouverner ce siège célèbre, alors qu'il exerçait la

fonction de préfet de la cité. Vrai pasteur et docteur des fidèles, il mit la

plus grande énergie à exercer la charité envers tous, à défendre la liberté de

l'Église et à enseigner la doctrine de la vraie foi contre les ariens et

enseigna au peuple la piété par ses commentaires de la Bible et les hymnes

qu'il composa.

Martyrologe romain

"Lorsque la prière est trop longue, elle se

répand souvent dans le vide mais, lorsqu'elle devient rare, la négligence nous

envahit"

Ambroise

Saint Ambroise de Milan

Évêque, Docteur de

l'Église

(333-398)

Saint Ambroise était fils

d'un préfet des Gaules. Étant encore au berceau, il dormait, un jour, quand

soudain des abeilles vinrent voltiger autour de lui et pénétrèrent dans sa

bouche ouverte, puis s'élevèrent vers le ciel: c'était le présage de son éloquence

et de sa grandeur future. Quelques années plus tard il prédit lui-même, sans

peut-être le comprendre, son avenir; car, s'étant aperçu que sa mère et sa

soeur baisaient la main de l'évêque, à l'église, il leur dit naïvement:

"Baisez-moi aussi la main, je serai évêque un jour."

Ambroise était gouverneur

de Milan, quand le peuple, réuni à l'église, semblait prêt à faire une sédition

pour obtenir un évêque, dont il était privé depuis vingt ans par la faute des

hérétiques. Le magistrat se rendit à l'église pour calmer la foule; mais voici

qu'un enfant l'interrompit et cria: "Ambroise évêque!" C'était la

voix du Ciel; celle du peuple y répondit, et le temple retentit de ce cri

répété avec enthousiasme: "Ambroise évêque! Ambroise évêque!"

Ambroise proteste; il objecte qu'il n'est que catéchumène, il se fraye un

passage à travers la foule et s'esquive en son palais; mais la foule le suit,

déjoue tous ses stratagèmes et répète cent fois le même cri. Il s'enfuit à

cheval pendant la nuit, mais il perd son chemin, et à son grand étonnement se

retrouve le matin à son point de départ.

On sait comment le nouvel

évêque comprit la mission qu'il avait reçue d'une manière si providentielle.

Ambroise fut le fléau des hérétiques et le vaillant défenseur de la vraie foi.

Parmi toutes ses vertus, l'énergie, une fermeté tout apostolique, semble avoir

été la principale. Un jour on vient lui apporter un ordre injuste signé par

l'empereur Valentinien: "Allez dire à votre maître, répondit Ambroise,

qu'un évêque ne livrera jamais le temple de Dieu." Bientôt il apprend que

les hérétiques, soutenus par l'autorité, vont s'emparer de deux basiliques:

"Allez, s'écria Ambroise du haut de la chaire sacrée, dire aux violateurs

des temples saints que l'évêque de Milan excommunie tous ceux qui prendront

part au sacrilège."

Le fait le plus célèbre,

c'est le châtiment qu'il osa imposer à l'empereur Théodose. Ce prince, les

mains encore souillées du sang versé au massacre de Thessalonique, se présente

au seuil du temple. Ambroise est là: "Arrêtez, lui dit-il; imitateur de

David dans son crime, imitez-le dans sa pénitence." Saint Ambroise fut un

grand évêque, un savant docteur, un orateur éloquent, un homme de haute

sainteté.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_ambroise.html

Paolo Veneziano, Polittico dei santi Cosma e

Damiano. La figura di Sant'Ambrogio.

Opera esposta nella Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo a

Brescia.

L’intime adversaire

Nul n’est davantage

notre adversaire que notre chute, qui nous accuse sur les preuves de

notre vie : non pas que le juge futur ait besoin du ministère d’un

accusateur quelconque, mais parce que devant le témoin de toutes choses notre

activité nous accuse, quand elle se trouve étrangère à la pratique de la vertu

et aux préceptes apostoliques. Ainsi notre adversaire, c’est toute habitude

vicieuse, notre adversaire c’est la passion ; adversaire l’avidité,

adversaire toute perversité, adversaire toute pensée inique, toute la mauvaise

conscience enfin, qui nous trouble ici-bas et plus tard nous accusera et

dénoncera, comme en témoigne l’Apôtre quand il dit : Leur conscience

en témoigne, ainsi que les arguments par lesquels ils se condamnent ou

s’approuvent les uns les autres (Rm 2, 15). Si la conscience de chacun le

dénonce, combien plus le résultat de nos actes est-il présent devant

Dieu !

Reste à découvrir

maintenant ce que veut dire la figure du centime. Et il semble que le nom

de cet objet familier exprime le mystère d’un sens spirituel. En effet, comme

on paie sa dette en rendant l’argent, et comme le titre à l’intérêt n’est

éteint que lorsque tout le montant du capital est payé jusqu’au dernier

centime, quel que soit le mode de paiement, de même c’est par la compensation

de la charité et des autres œuvres, ou par une satisfaction quelconque, que la

peine du péché est éteinte.

Saint Ambroise de Milan

Saint Ambroise († 397),

évêque de Milan et orateur réputé, a aussi écrit des hymnes pour la liturgie. /

Traité sur l’Évangile de saint Luc, t. II, VII, 151-152.156, trad. G. Tissot,

Paris, Cerf, coll. « Sources Chrétiennes » 52, 1958, p. 64-66.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/vendredi-21-octobre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Ceci est mon corps

T’approchant de l’autel,

peut-être te dis-tu : « C’est mon pain ordinaire. » Mais ce pain

est du pain avant les paroles sacramentelles ; dès que survient la

consécration, le pain se change en la chair du Christ. Car tout ce qu’on dit

avant est dit par le prêtre : on loue Dieu, on lui adresse la prière, on

prie pour le peuple, pour les rois, pour tous les autres. Dès qu’on en vient à

produire le vénérable sacrement, le prêtre ne se sert plus de ses propres

paroles, mais il se sert des paroles du Christ. C’est donc la parole du Christ

qui produit ce sacrement.

Quelle est cette parole

du Christ ? Eh bien, c’est celle par laquelle tout a été fait. Le Seigneur

a ordonné, le ciel a été fait. Le Seigneur a ordonné, la terre a été faite. Le

Seigneur a ordonné, toutes les créatures ont été engendrées. Tu vois donc comme

elle est efficace, la parole du Christ !

Tu existais toi-même, mais

tu étais une vieille créature ; une fois consacré, tu as commencé à être

une nouvelle créature.

St Ambroise de Milan

Saint Ambroise († 397),

évêque de Milan et orateur réputé, a aussi écrit des hymnes pour la liturgie. /

Des sacrements, IV, 14-16, trad. B. Botte, Paris, Cerf, 2007, Sources

Chrétiennes 25 bis, p. 109-111.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/dimanche-2-juin-2/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Simone Martini (1284–1344), Altarretabel

von Pisa,

dritte Predellatafel von rechts: Hl. Agnes und Hl. Ambrosius, 1319, Museo di

San Matteo, Pisa

Dieu se jette à ton cou

À ta rencontre vient Celui qui t’entend converser dans le secret de ton âme ; et quand tu es encore loin, il te voit et accourt. Il voit dans ton cœur ; il accourt, pour que nul ne te retarde ; il t’embrasse aussi. Sa rencontre, c’est sa prescience ; son embrassement, c’est sa clémence, et les démonstrations de son amour paternel. Il se jette à ton cou pour te relever gisant, et, chargé de péchés et tourné vers la terre, te retourner vers le ciel pour y chercher ton auteur. Le Christ se jette à ton cou pour dégager ta nuque du joug de l’esclavage et suspendre à ton cou son « joug facile à porter ». Il se jette à ton cou lorsqu’il dit : « Venez à moi, vous tous qui peinez sous le poids du fardeau, et moi, je vous procurerai le repos. » Telle est la manière dont il t’étreint, si tu te convertis.

St Ambroise de Milan

Saint Ambroise († 397), évêque de Milan et orateur réputé, a aussi écrit des hymnes pour la liturgie. / Traité sur l’Évangile de S. Luc VII, 230, trad. G. Tissot, Paris, Cerf, Sources Chrétiennes 52, 1958, p. 94-95.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/mercredi-7-decembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-2/

Pietro

daRrimini e bottega, affreschi dalla Chiesa di S. Chiara a Ravenna, 1310-1320

ca., volta con Evangelisti e Dottori, Ambrogio e Marco

Cherche-moi, trouve-moi

Viens, Seigneur, chercher

ton serviteur (Ps 118, 176). Viens sans te faire aider et sans

t’annoncer : depuis longtemps je t’attends, toi qui dois venir. Car je

sais que tu viendras – car je n’ai pas oublié tes volontés (Ps 118,

176). Viens, non pas avec un bâton, mais avec la charité et l’Esprit de

douceur. N’hésite pas à laisser dans les montagnes tes quatre-vingt-dix-neuf

autres brebis, car établies dans les hauteurs, les loups rapaces ne peuvent les

attaquer.

Cherche-moi, car moi, je

te cherche. Cherche-moi, trouve-moi, prends-moi, porte-moi. Tu es capable de

trouver celui que tu cherches. Porte-moi sur ta croix qui est le salut des

brebis errantes, en qui seule se trouve le repos des fatigués, en qui seule

vivent ceux qui sont morts. Car il ne peut mourir celui que ta puissance porte

sur ses épaules.

St Ambroise de Milan

Saint Ambroise († 397),

évêque de Milan et orateur réputé, a aussi écrit des hymnes pour la

liturgie. / Sermon 22 sur le psaume 118, 27-30, trad. L. Brésard, 2 000 ans

d’homélies, année C, Perpignan, Socéval, 2000, p. 28-29.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/jeudi-3-novembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 24 octobre 2007

Saint Ambroise

Chers frères et sœurs,

Le saint Evêque Ambroise - dont je vous parlerai aujourd'hui - mourut à Milan dans la nuit du 3 au 4 avril 397. C'était l'aube du Samedi Saint. La veille, vers cinq heures de l'après-midi, il s'était mis à prier, étendu sur son lit, les bras ouverts en forme de croix. Il participait ainsi, au cours du s

olennel triduum pascal, à la

mort et à la résurrection du Seigneur. "Nous voyions ses lèvres

bouger", atteste Paulin, le diacre fidèle qui, à l'invitation d'Augustin,

écrivit sa Vie, "mais nous n'entendions pas sa voix". Tout d'un coup,

la situation parut précipiter. Honoré, Evêque de Verceil, qui assistait

Ambroise et qui se trouvait à l'étage supérieur, fut réveillé par une voix qui

lui disait: "Lève-toi, vite! Ambroise va mourir...". Honoré descendit

en hâte - poursuit Paulin - "et présenta le Corps du Seigneur au saint. A

peine l'eut-il pris et avalé, Ambroise rendit l'âme, emportant avec lui ce bon

viatique. Ainsi, son âme, restaurée par la vertu de cette nourriture, jouit à

présent de la compagnie des anges" (Vie 47). En ce Vendredi Saint de l'an

397, les bras ouverts d'Ambroise mourant exprimaient sa participation mystique

à la mort et à la résurrection du Seigneur. C'était sa dernière catéchèse: dans

le silence des mots, il parlait encore à travers le témoignage de sa vie.

Ambroise n'était pas

vieux lorsqu'il mourut. Il n'avait même pas soixante ans, étant né vers 340 à

Trèves, où son père était préfet des Gaules. Sa famille était chrétienne. A la

mort de son père, sa mère le conduisit à Rome alors qu'il était encore jeune homme,

et le prépara à la carrière civile, lui assurant une solide instruction

rhétorique et juridique. Vers 370, il fut envoyé gouverner les provinces de

l'Emilie et de la Ligurie, son siège étant à Milan. C'est précisément en ce

lieu que faisait rage la lutte entre les orthodoxes et les ariens, en

particulier après la mort de l'Evêque arien Auxence. Ambroise intervint pour

pacifier les âmes des deux factions adverses, et son autorité fut telle que,

bien que n'étant qu'un simple catéchumène, il fut acclamé Evêque de Milan par

le peuple.

Jusqu'à ce moment,

Ambroise était le plus haut magistrat de l'Empire dans l'Italie du Nord.

Culturellement très préparé, mais tout aussi démuni en ce qui concerne

l'approche des Ecritures, le nouvel Evêque se mit à étudier avec ferveur. Il

apprit à connaître et à commenter la Bible à partir des œuvres d'Origène, le

maître incontesté de l'"école alexandrine". De cette manière,

Ambroise transféra dans le milieu latin la méditation des Ecritures commencée

par Origène, en introduisant en Occident la pratique de la lectio divina. La

méthode de la lectio finit par guider toute la prédication et les écrits

d'Ambroise, qui naissent précisément de l'écoute orante de la Parole de Dieu.

Un célèbre préambule d'une catéchèse ambrosienne montre de façon remarquable

comment le saint Evêque appliquait l'Ancien Testament à la vie chrétienne:

"Lorsque nous lisions les histoires des Patriarches et les maximes des

Proverbes, nous parlions chaque jour de morale - dit l'Evêque de Milan à ses

catéchumènes et à ses néophytes - afin que, formés et instruits par ceux-ci,

vous vous habituiez à entrer dans la vie des Pères et à suivre le chemin de

l'obéissance aux préceptes divins" (Les mystères, 1, 1). En d'autres

termes, les néophytes et les catéchumènes, selon l'Evêque, après avoir appris

l'art de bien vivre, pouvaient désormais se considérer préparés aux grands

mystères du Christ. Ainsi, la prédication d'Ambroise - qui représente le noyau

fondamental de son immense œuvre littéraire - part de la lecture des Livres

saints ("les Patriarches", c'est-à-dire les Livres historiques, et

"les Proverbes", c'est-à-dire les Livres sapientiels), pour vivre

conformément à la Révélation divine.

Il est évident que le

témoignage personnel du prédicateur et le niveau d'exemplarité de la communauté

chrétienne conditionnent l'efficacité de la prédication. De ce point de vue, un

passage des Confessions de saint Augustin est significatif. Il était venu à

Milan comme professeur de rhétorique; il était sceptique, non chrétien. Il

cherchait, mais il n'était pas en mesure de trouver réellement la vérité

chrétienne. Ce qui transforma le cœur du jeune rhéteur africain, sceptique et

désespéré, et le poussa définitivement à la conversion, ne furent pas en

premier lieu les belles homélies (bien qu'il les appréciât) d'Ambroise. Ce fut

plutôt le témoignage de l'Evêque et de son Eglise milanaise, qui priait et

chantait, unie comme un seul corps. Une Eglise capable de résister aux

violences de l'empereur et de sa mère, qui aux premiers jours de l'année 386,

avaient recommencé à prétendre la réquisition d'un édifice de culte pour les

cérémonies des ariens. Dans l'édifice qui devait être réquisitionné - raconte

Augustin - "le peuple pieux priait, prêt à mourir avec son Evêque". Ce

témoignage des Confessions est précieux, car il signale que quelque chose se

transformait dans le cœur d'Augustin, qui poursuit: "Nous aussi, bien que

spirituellement encore tièdes, nous participions à l'excitation du peuple tout

entier" (Confessions 9, 7).

Augustin apprit à croire

et à prêcher à partir de la vie et de l'exemple de l'Evêque Ambroise. Nous

pouvons nous référer à un célèbre sermon de l'Africain, qui mérita d'être cité

de nombreux siècles plus tard dans la Constitution conciliaire Dei Verbum:

"C'est pourquoi - avertit en effet Dei Verbum au n. 25 - tous les clercs,

en premier lieu les prêtres du Christ, et tous ceux qui vaquent normalement,

comme diacres ou comme catéchistes, au ministère de la Parole, doivent, par une

lecture spirituelle assidue et par une étude approfondie, s'attacher aux

Ecritures, de peur que l'un d'eux ne devienne "un vain prédicateur de la

Parole de Dieu au-dehors, lui qui ne l'écouterait pas au-dedans de

lui"". Il avait appris précisément d'Ambroise cette "écoute

au-dedans", cette assiduité dans la lecture des Saintes Ecritures, dans

une attitude priante, de façon à accueillir réellement dans son cœur la Parole

de Dieu et à l'assimiler.

Chers frères et sœurs, je

voudrais vous proposer encore une sorte d'"icône patristique", qui,

interprétée à la lumière de ce que nous avons dit, représente efficacement

"le cœur" de la doctrine ambrosienne. Dans son sixième livre des

Confessions, Augustin raconte sa rencontre avec Ambroise, une rencontre sans

aucun doute d'une grande importance dans l'histoire de l'Eglise. Il écrit

textuellement que, lorsqu'il se rendait chez l'Evêque de Milan, il le trouvait

régulièrement occupé par des catervae de personnes chargées de problèmes, pour

les nécessités desquelles il se prodiguait; il y avait toujours une longue file

qui attendait de pouvoir parler avec Ambroise, pour chercher auprès de lui le

réconfort et l'espérance. Lorsqu'Ambroise n'était pas avec eux, avec les

personnes, (et cela ne se produisait que très rarement), il restaurait son

corps avec la nourriture nécessaire, ou nourrissait son esprit avec des

lectures. Ici, Augustin s'émerveille, car Ambroise lisait l'Ecriture en gardant

la bouche close, uniquement avec les yeux (cf. Confess. 6, 3). De fait, au

cours des premiers siècles chrétiens la lecture était strictement conçue dans

le but de la proclamation, et lire à haute voix facilitait également la

compréhension de celui qui lisait. Le fait qu'Ambroise puisse parcourir les

pages uniquement avec les yeux, révèle à un Augustin admiratif une capacité

singulière de lecture et de familiarité avec les Ecritures. Et bien, dans cette

"lecture du bout des lèvres", où le cœur s'applique à parvenir à la

compréhension de la Parole de Dieu - voici "l'icône" dont nous

parlons -, on peut entrevoir la méthode de la catéchèse ambrosienne: c'est

l'Ecriture elle-même, intimement assimilée, qui suggère les contenus à annoncer

pour conduire à la conversion des cœurs.

Ainsi, selon le magistère

d'Ambroise et d'Augustin, la catéchèse est inséparable du témoignage de la vie.

Ce que j'ai écrit dans l'Introduction au christianisme, à propos du théologien,

peut aussi servir pour le catéchiste. Celui qui éduque à la foi ne peut pas

risquer d'apparaître comme une sorte de clown, qui récite un rôle "par

profession". Il doit plutôt être - pour reprendre une image chère à

Origène, écrivain particulièrement apprécié par Ambroise - comme le disciple

bien-aimé, qui a posé sa tête sur le cœur du Maître, et qui a appris là la

façon de penser, de parler, d'agir. Pour finir, le véritable disciple est celui

qui annonce l'Evangile de la manière la plus crédible et efficace.

Comme l'Apôtre Jean,

l'Evêque Ambroise - qui ne se lassait jamais de répéter: "Omnia Christus

est nobis!; le Christ est tout pour nous!" - demeure un authentique témoin

du Seigneur. Avec ses paroles, pleines d'amour pour Jésus, nous concluons ainsi

notre catéchèse: "Omnia Christus est nobis! Si tu veux guérir une

blessure, il est le médecin; si la fièvre te brûle, il est la source; si tu es

opprimé par l'iniquité, il est la justice; si tu as besoin d'aide, il est la

force; si tu crains la mort, il est la vie; si tu désires le ciel, il est le

chemin; si tu es dans les ténèbres, il est la lumière... Goûtez et voyez comme

le Seigneur est bon: bienheureux l'homme qui espère en lui!" (De

virginitate, 16, 99). Plaçons nous aussi notre espérance dans le Christ. Nous

serons ainsi bienheureux et nous vivrons en paix.

* * *

Je suis heureux de saluer

les pèlerins de langue française, particulièrement les membres du Chapitre général

de la Congrégation de Jésus-Marie. Que votre Chapitre soit pour toutes les

religieuses de l’Institut l’occasion d’un renouveau en profondeur de leur vie

consacrée apostolique, fondée sur une relation forte avec la personne de Jésus

Christ ! J’adresse aussi un salut affectueux aux jeunes. À la suite de saint

Ambroise, soyez tous d’authentiques témoins du Seigneur parmi vos frères ! Avec

ma Bénédiction apostolique.

© Copyright 2007 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Saint Ambroise de Milan :

Vie et Oeuvres

Publié le 4/12/23

Familier des princes, ami

des petits, homme d’État et homme d’Église, intraitable au péché, compatissant

aux pécheurs, la haute stature d’Ambroise suscite une universelle admiration.

Son secret ? N’avoir jamais quitté des yeux les Saintes Écritures.

Qui sont réellement les

Pères de l'Église, ces défenseurs ardents de la foi chrétienne dont l'influence

perdure encore aujourd'hui ? Dans cette série, explorons avec le père Guillaume

de Menthière les figures emblématiques des premiers temps du christianisme, de

Saint Ignace à Saint Grégoire le Grand, en passant par Saint Ambroise.

Saint Ambroise de Milan,

né à Trêves vers 340 dans une famille chrétienne de haut rang, est l'une des

figures les plus influentes du christianisme primitif. Il est célèbre non

seulement pour son rôle d'évêque de Milan mais aussi pour son impact

considérable sur la théologie, la liturgie et la politique de son temps. Sa vie

a été marquée par une série d'événements extraordinaires, notamment son

élection soudaine comme évêque alors qu'il n'était même pas encore baptisé.

Consacré évêque le 7 décembre 373, il devint un défenseur acharné de

l'orthodoxie chrétienne et joua un rôle clé dans la conversion de saint

Augustin. Ambroise est également reconnu pour son influence politique, ayant eu

le courage de défier les empereurs pour des questions de foi et de morale. Il

est fêté le 7 décembre, jour de sa consécration épiscopale.

Biographie de Saint

Ambroise

Date de naissance et de

décès : Saint Ambroise est né vers 340 à Trêves, dans ce qui est

aujourd'hui l'Allemagne, et il est décédé le 4 avril 397 à Milan, Italie.

Origine et contexte

familial : Issu d'une famille chrétienne de haut rang, Ambroise était le

cadet de trois enfants. Son père était préfet romain de la Gaule, ce qui lui a

permis de recevoir une éducation classique et juridique de qualité.

Moments clés de sa vie :

Formation et carrière

pré-épiscopale : Ambroise a reçu une éducation solide en rhétorique,

droit, et grec. Il a gravi les échelons jusqu'à devenir gouverneur de Milan, un

poste de grande importance dans l'Empire romain à l'époque.

Élection épiscopale

inattendue : En 374, alors qu'il tentait de pacifier un conflit entre

ariens et nicéens concernant la sélection d'un nouveau évêque de Milan, il fut

choisi par acclamation populaire pour devenir évêque, bien qu'il fût encore catéchumène

à ce moment-là.

Baptême et consécration :

Rapidement baptisé et ordonné, Ambroise adopta un style de vie ascétique et se

dévoua entièrement à l'épiscopat, mettant ses vastes connaissances au service

de l'Église.

Confrontations politiques

et défense de la foi : Ambroise s'est distingué par son audace à

confronter les empereurs sur des questions de foi et de justice, notamment dans

sa célèbre confrontation avec l'empereur Théodose après le massacre de

Thessalonique.

Influence sur saint

Augustin : Ambroise a joué un rôle déterminant dans la conversion de saint

Augustin au christianisme, influençant l'un des plus grands penseurs de

l'Église.

Saint Ambroise est resté

célèbre pour sa capacité à articuler la doctrine chrétienne, sa fermeté dans la

foi, et son impact durable tant sur le plan ecclésiastique que politique. Sa

vie témoigne de la manière dont la foi peut guider le service public et

influencer profondément la culture et la politique.

Contributions et Œuvres

de Saint Ambroise

Description des

contributions majeures : Saint Ambroise est reconnu pour ses contributions

fondamentales à la doctrine chrétienne, à la liturgie, et à l'éthique

ecclésiastique. Sa défense de la foi nicéenne contre l'arianisme et son

influence dans les sphères politiques et sociales de son temps ont marqué de

manière indélébile l'histoire de l'Église.

Œuvres ou écrits

importants :

Hexameron : Un

ouvrage sur les six jours de la création, qui illustre la profondeur de sa

réflexion théologique et son engagement envers la compréhension des Écritures.

De Officiis Ministrorum :

Inspiré par le travail de Cicéron, ce texte traite des devoirs des responsables

de l'église, jetant les bases de la pensée chrétienne sur la morale et

l'éthique.

Commentaires sur les

Psaumes : Ces commentaires illustrent son approche exégétique et sa

capacité à interpréter les textes bibliques de manière à nourrir la vie

spirituelle des fidèles.

De Virginibus et De

Viduis : Des traités sur la vie consacrée qui encouragent la virginité et

le veuvage comme formes de dévotion chrétienne, soulignant la haute estime

qu'Ambroise portait à la chasteté.

Hymnes : Saint

Ambroise a introduit le chant antiphonique dans la liturgie occidentale,

enrichissant considérablement la musique sacrée de l'Église. Ses hymnes sont

parmi les premières grandes œuvres de la tradition hymnographique occidentale.

La capacité d'Ambroise à

intégrer la philosophie classique dans le discours chrétien a établi un

précédent pour la manière dont l'Église pourrait dialoguer avec la culture

environnante. Ses efforts pour défendre l'indépendance de l'Église face au

pouvoir politique ont également posé les bases des discussions ultérieures sur

les relations entre l'Église et l'État. Ses écrits et son héritage liturgique continuent

d'influencer la théologie, la musique et la pastorale chrétiennes à ce jour.

Signification et

Influence de Saint Ambroise

L'impact et la

signification de Saint Ambroise de Milan dans l'Église sont immenses.

Reconnu comme l'un des quatre Pères latins de l'Église occidentale, aux côtés

de Saint Augustin, Saint Jérôme et Saint Grégoire le Grand, Ambroise a joué un

rôle crucial dans le développement de la théologie chrétienne, en particulier

en matière de christologie, de sotériologie, et de mariologie.

Son approche innovante de

la liturgie, notamment par l'introduction des hymnes et du chant antiphonique,

a permis d'enrichir la dimension spirituelle et communautaire du culte

chrétien, influençant la tradition liturgique occidentale de manière durable.

Saint Ambroise est

également célèbre pour son impact sur la conversion et la formation théologique

de Saint Augustin, l'un des plus grands penseurs de l'histoire chrétienne.

Cette relation mentor-disciple a façonné le développement de la théologie

occidentale de façon significative.

Célébration de Saint

Ambroise

Date de la fête : Saint Ambroise est célébré le 7 décembre, qui est le jour de sa consécration épiscopale et aussi reconnu comme le jour de sa fête dans l'Église catholique ainsi que dans d'autres traditions chrétiennes.

Pour aller plus loin,

découvrez également 10 autres articles sur les Pères de l’Église :

Qu'est-ce

qu'un Père de L'Église ?

Audience

de Benoit XVI sur Saint Ambroise de Milan

Giovanni di Paolo (1403–1482), Saint

Ambrose,

circa 1465, 60,6 x 36,8, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert

Lehman Collection

Saint Ambroise ou le rêve

d’un empire catholique

Basilique de

Sant'Ambrogio, Milan. Retable de Camillo Procaccini (1551-1629) représentant

Saint Ambroise arrêtant l'empereur Théodose aux portes de la basilique après le

massacre de Thessalonique en 390 après J.-C.

Anne Bernet - publié

le 06/12/23

Grand serviteur de

l’Empereur, devenu évêque, Ambroise n’aura qu’une ambition : établir les droits

de Dieu et de l’Église sur Rome, unique moyen de délivrer l’Empire des tares

qui le rongent. L’Église le fête le 7 décembre.

Héritier d’une famille de

grands serviteurs patriciens de l’État, lui-même entré tôt dans la haute

fonction publique, Aurelius Ambrosius est promis à un rôle de premier plan.

Gouverneur de Ligurie-Émilie, il devient par surprise en décembre 374, évêque

de Milan. Le nouveau prélat n’en nourrit pas moins des vues politiques, non par

ambition personnelle, mais pour le bien commun.

Conscience de l’Empire

Son objectif ? Régénérer,

en le christianisant pour de bon, un Empire romain gangrené par le lucre, la

luxure, la corruption, les malversations, menacé par l’appartenance de

l’impératrice Justine à l’hérésie arienne, les tentatives de mainmise du

souverain sur l’Église, l’influence d’un parti païen encore puissant en quête

d’une revanche sur les chrétiens, l’omniprésente menace barbare.

Face à ces périls,

Ambroise dresse la croix et l’évangile, quitte à se faire de puissants, nombreux

et dangereux ennemis. Mais, élevé dans le culte des martyrs, le prélat dont la

devise épiscopale pourrait être : « À Dieu ma préférence » ne

reculera jamais. Malgré les difficultés, véritable conscience de l’Empire,

conseiller détesté parfois, respecté toujours, de la dynastie valentinienne, il

semblera souvent soutenir à lui seul la grandeur chancelante de Rome. Sa mort

prématurée, le soir de Pâques 397, a-t-elle changé le cours de l’histoire, et

empêché la survie de l’Empire romain d’Occident ? Peut-être…

Repéré pour sa probité

En 341, le père

d’Ambroise, préfet du prétoire d’Occident, chargé d’administrer Gaule, Espagne,

Belgique, Germanie, Bretagne insulaire, meurt, victime des querelles des fils

de Constantin, quelques mois après la naissance de son cadet à Trèves. Ce drame

ne nuit pas à Ambroise et son aîné, Satyrus, car les réseaux familiaux de

l’aristocratie catholique sont puissants. En 366, les garçons sont nommés

avocats à la cour centrale de justice de Sirmium en Pannonie seconde, poste

difficile où leurs compétences et leur inentamable probité, les signalent à

l’attention de leur protecteur, Probus, tout-puissant préfet du prétoire

d’Italie. L’homme est pourri mais a le sens de l’État. Désireux de supprimer

des abus dont il est, au demeurant, le premier à profiter, il ambitionne une

grande « opération mains propres » et cherche sur qui s’appuyer pour

le seconder.

En quelques jours,

Ambroise reçoit baptême, ordination sacerdotale, sacre épiscopal.

Voilà comment, en 370,

Ambroise est nommé gouverneur de Ligurie-Émilie, poste qui le confronte à la

misère sociale de son temps et au féroce égoïsme des riches, fléau contre

lesquels il ne cessera, devenu évêque, de s’insurger. À la mort de l’évêque de

Milan, Auxence, dernier prélat arien d’Italie, Ambroise se voit contraint de

lui succéder, alors qu’il n’est même pas baptisé. En quelques jours, il reçoit

baptême, ordination sacerdotale, sacre épiscopal. Dans l’esprit de Probus,

désireux de ménager le parti arien, il s’agit d’un habile arrangement

diplomatique, Ambroise passant pour un catholique tiède qui ne gênera personne.

Erreur !

Un geste d’une audace

folle

Puisque l’empereur, en le

forçant à accepter l’épiscopat, l’a libéré de l’obéissance qu’il lui devait et

mis au service du vrai Maître, Ambroise ne travaillera plus désormais qu’à

établir les droits de Dieu et de l’Église sur Rome, unique moyen de délivrer

l’Empire des tares qui le rongent. Décidé à assumer parfaitement ses

obligations épiscopales, Ambroise ose contester au clergé arien la propriété

des basiliques milanaises, confisquées aux catholiques, malgré l’impératrice

Justine, qui gouverne depuis la mort de son époux. Il défend par ses discours

et ses écrits la divinité du Christ niée par les hérétiques, revendique pour

les chrétiennes le droit de préférer la vie consacrée au mariage, convainc le

jeune empereur Gratien de bannir du sénat la statue de la Victoire, afin que

des délibérations chrétiennes ne soient pas présidées par une idole, enseigne,

convertit Augustin…

Ambroise marque la

distance entre les droits des princes et ceux de Dieu, agenouillant le pouvoir

temporel devant le spirituel.

En 390, il ose

excommunier l’empereur Théodose qui s’est rendu coupable d’un épouvantable

massacre de civils à Thessalonique pour punir la ville d’avoir assassiné son

gouverneur lors d’une émeute. Avant de le réintroduire dans l’Église, il

exige qu’il fasse pénitence publique le soir de Noël. Par ce geste

d’une audace folle qui aurait pu lui coûter la tête, Ambroise marque la

distance entre les droits des princes et ceux de Dieu, agenouillant le pouvoir

temporel devant le spirituel. Il donnera ainsi paradoxalement sa légitimité au

système monarchique qui n’était jusqu’alors que tyrannie hors de contrôle, mais

dont les détenteurs rendront à l’avenir des comptes au Ciel et à ses

représentants sur terre, façonnant du même coup le futur visage de l’Occident

chrétien.

Le seul but

Certes, en cette fin du

IVe siècle, Ambroise ne peut imaginer cet avenir que dans le cadre de cet

Empire romain que, par son courage et son exemple, il est en train, en effet,

de rendre chrétien tout de bon. Un coup de froid, pris lors d’une tournée

pastorale effectuée malgré un printemps glacial et une santé défaillante, le

tue, deux ans après le décès de Théodose, anéantissant cette œuvre patiente.

L’Empire est laissé aux mains d’adolescents peu doués et de conseillers

ambitieux ou désemparés. Quelques années suffiront pour livrer l’Occident aux

Barbares qui prendront Rome en 410. Le rêve politique d’Ambroise, lui disparu,

n’était pas viable mais sa vision religieuse perdurera ; à terme, elle

permettra la renaissance d’une civilisation chrétienne en Europe. Tel était, au

vrai, le seul but poursuivi par le grand évêque de Milan.

Lire aussi :Saint Satyre, le mal nommé

Lire aussi :Prière de saint Ambroise pour un proche en train de mourir

Subleyras, Saint Ambroise convertissant Théodose, 1745, National Gallery of Umbria (https://www.wga.hu/html/s/subleyra/ambrose.html)

Devant l’évêque Ambroise, le Noël à genoux de l’empereur Théodose

Anne

Bernet - publié le 06/12/22

Après ce Noël, rien ne

sera plus comme avant, et pour longtemps. L’Église fête son roi de gloire, un

enfant pauvre né dans une crèche, et l’Empereur, repentant, reconnaît devant

son évêque qu’il n’a pas tous les pouvoirs.

En cette vigile de la

Nativité 390, la basilique Portia de Milan resplendit de mille feux. Tapis et

tentures de pourpre ont été déployés ; les encensoirs font monter vers les

voûtes des volutes d’encens parfumées et l’assemblée a entonné ces hymnes

que l’évêque

Ambroise a introduites dans la liturgie pour mieux célébrer la louange

divine. Le spectacle, magnifique, donnerait presque un avant-goût du paradis.

Le Christ est né, la Seconde Personne de la Sainte Trinité s’est abaissée

jusqu’à prendre la nature humaine. Grave au milieu de la liesse ambiante,

Ambroise se dirige vers le porche fermé qu’il fait signe d’ouvrir.

À genoux sur le parvis

Là, sur le parvis, un

homme se tient humblement agenouillé, tête basse, vêtu d’une simple tunique,

dans l’attitude traditionnelle des pénitents venus implorer de l’Église la

levée des sanctions qui les frappent et leur réintégration dans la communauté

catholique. En cette époque qui ne connaît pas encore la confession, la scène

est fréquente. Un grand pécheur ne peut obtenir son pardon qu’au prix de

lourdes, longues et pénibles pénitences, publiques de surcroît. L’épreuve peut

durer des années, toute une vie parfois.

L’homme qui se tient à

genoux sur le parvis est un très grand pécheur, coupable de la mort de milliers

d’innocents, victimes d’une tendance à la colère qu’il n’a jamais su ni voulu

dominer, défaut exacerbé depuis qu’il détient le pouvoir absolu. De cette toute

puissance, il a cruellement abusé, se sentant dans son droit. Il a eu tort et,

comme, malgré ses excès, il est un catholique sincère, il a accepté d’en payer

le prix. Cela n’a l’air de rien mais la scène qui se joue sur le parvis de la

basilique milanaise est l’une des plus déterminantes de l’Histoire ; elle

décide pour plus de quinze siècles des relations entre l’Église et le pouvoir

temporel, jette les fondements de la monarchie chrétienne. Car l’homme

prosterné devant Ambroise s’appelle Théodose, surnommé le Grand, détenteur de

la pourpre. Pour la première fois dans l’histoire de l’humanité, un souverain

autocrate à même d’imposer à ses sujets tous ses caprices, fussent les pires,

reconnaît qu’il existe au-dessus de lui une puissance à laquelle il devra un

jour rendre des comptes. Ce triomphe du Christ sur César, c’est la victoire

d’Ambroise, frêle quinquagénaire épuisé de veilles, de prières, de soucis, de

travail, mais animé d’un souci des âmes qui lui fait tout braver.

Ses vérités en face

L’histoire a commencé au

printemps précédent dans la ville grecque de Thessalonique où deux hommes se

disputent les faveurs d’un joli garçon… L’un est un conducteur de char célèbre,

idole des foules, l’autre le gouverneur de la cité, Boutherikos qui, afin de se

débarrasser d’un rival, se sert d’une nouvelle législation impériale réprimant

l’homosexualité pour arrêter le champion, le jeter en prison, puis le maintenir

en détention malgré les pétitions de ses « fans ». Jouer avec les

passions sportives des foules peut être dangereux, Boutherikos l’apprend à ses

dépens. Son refus de libérer l’aurige provoque des émeutes et, en juillet, il

finit massacré par des parieurs exaspérés qui vont ensuite libérer leur

champion.

“Je n’ai pas prêché

contre toi, j’ai prêché pour toi !” a-t-il rétorqué un jour à Théodose qui lui

reprochait d’avoir attaqué sa politique religieuse dans un sermon.

La nouvelle de ce meurtre

atteint Milan, l’une des capitales impériales, où Théodose s’est installé,

début août. De tels incidents ne sont pas rares. Le pouvoir impérial s’en

accommode avec pragmatisme et les sanctions, quand il y en a, se bornent au

versement de dommages et intérêts. Cela évite d’aggraver tensions et

mécontentements. Théodose ne s’en tient pas à cette ligne de conduite. L’homme

est emporté. Haut officier, il n’a pas hérité de la pourpre mais s’en est

emparé, d’abord en Orient, au lendemain du désastre militaire d’Andrinople en

378, puis en Occident en profitant de la faiblesse du jeune empereur

Valentinien II, un adolescent confronté à des usurpateurs qu’il n’a pu vaincre

; il est entré ensuite dans la famille impériale en épousant la sœur de

Valentinien, la princesse Galla. Devenu indispensable, Théodose est le maître

du jeu politique auquel nul n’ose s’opposer. Excepté l’évêque Ambroise,

aristocrate romain de la vieille école que son passé de très haut fonctionnaire

impérial a familiarisé avec les rouages du pouvoir et de l’administration. À

plusieurs reprises, avec la liberté de ton et l’audace de celui qui place sa

confiance en Dieu, non dans les hommes, Ambroise a dit à Théodose ses vérités

en face, et en public. Depuis, l’empereur, humilié, ne se cache pas de détester

l’évêque de Milan, avec lequel il est pourtant obligé de composer. Ambroise le

sait, et ne change pas d’attitude pour autant. « Je n’ai pas prêché contre

toi, j’ai prêché pour toi ! » a-t-il rétorqué un jour à Théodose qui lui

reprochait d’avoir attaqué sa politique religieuse dans un sermon. Une nuance

que l’autre feint de ne pas comprendre. N’est-il pas le maître de l’Empire, qui

n’a de leçon à recevoir de quiconque, même de l’Église ? Méfiant, il a interdit

que l’on évoque devant Ambroise les sujets débattus au conseil des ministres.

Une décision horrible

En ce 10 août 390,

l’empereur entend le rappeler. Au lieu de passer l’éponge, il prend des mesures

de représailles d’une sévérité inédite : les troupes envoyées sur place

passeront au fil de l’épée un dixième de la population de Thessalonique, pris

au hasard, vieillards, femmes, enfants, voyageurs et touristes compris…

Théodose est dans une telle fureur qu’aucun de ses proches n’ose dénoncer

l’injustice et l’horreur de sa décision, ni lui désobéir en avertissant

Ambroise, seul capable de lui tenir tête. L’évêque n’est mis au courant, par

une indiscrétion, que le 18. Voilà huit jours que les ordres impériaux sont

partis. Théodose n’en éprouve aucun regret. Il est victime de l’ubris, mot grec

qui désigne la démesure, maladie du pouvoir absolu faisant perdre le sens du

réel, aggravée par son acceptation, qui a scandalisé l’Église, des anciennes

titulatures impériales païennes. L’on n’exige pas d’être appelé

« divin » empereur à longueur de journée sans finir par oublier que

l’on est un mortel comme les autres, qui met en jeu le salut de son âme et ne

s’en aperçoit même plus.

Devant l’empereur, il

dit, avec une douleur évidente : “As-tu oublié que tu étais chrétien ?”

Cette réalité bouleverse

Ambroise et le fait se précipiter au palais impérial. Devant l’empereur, il

dit, avec une douleur évidente : « As-tu oublié que tu étais chrétien

? » Oui, Théodose l’a oublié. Soudain calmé, il mesure l’horreur de son

acte, signe un contrordre qui doit partir immédiatement mais ne partira que

deux jours après, certains ministres refusant de voir l’empereur se désavouer

pour plaire à l’Église… Lorsque le contrordre atteindra Thessalonique, le pire

aura eu lieu, le massacre aura été perpétré. Certains historiens parleront de

70.000 morts, chiffre sans doute exagéré mais il est certain que des milliers

de gens ont péri dans ces représailles injustes et disproportionnées.

« Si tu es

chrétien… »

La nouvelle du carnage

arrive à Milan alors qu’Ambroise préside un concile d’évêques italiens et

gaulois, et les plonge dans la stupeur. L’histoire romaine ne connaît pas

d’exemple d’une pareille monstruosité, et il faut que ce soit un empereur

catholique qui s’en rende coupable ! Pour s’être couvert de sang innocent,

Théodose mérite l’excommunication ; il doit faire pénitence. Reste à aller le

lui dire et cela, aucun des évêques n’en trouve le courage. Sauf Ambroise qui

ne recule jamais quand il s’agit du Christ, de l’Église et du salut des âmes.

Conscient qu’il risque au pire sa tête, au mieux d’être destitué de l’évêché de

Milan, il écrit à l’empereur une lettre admirable :

« À Thessalonique,

il s’est passé quelque chose d’atroce, de sans exemple. Je souffre de te voir,

toi, un modèle de piété encore inconnu, toi qui pratiquais la plus haute

clémence et ne supportais même pas d’assister à l’exécution d’un coupable,

accepter sans émotion la mort de tant d’innocents… […] Maintes actions t’ont

valu des louanges, mais c’était ta piété qui mettait le comble à ta gloire et

de ce que tu possédais de meilleur que le diable est devenu jaloux. Ce crime

odieux pèserait également sur mes épaules si ni moi ni personne ne te disait

que tu dois te réconcilier avec Dieu. Tu n’es qu’un homme. Le péché est venu.

Eh bien, chasse-le !

Je n’oserais offrir le saint

sacrifice si tu te présentais à l’église et prétendais y assister. Il m’est

interdit de célébrer en présence de celui qui a versé le sang d’un seul

innocent. Comment pourrais-je célébrer devant celui qui a versé le sang de tant

de malheureux ? Je pense n’en avoir pas le droit. J’écris cette lettre de ma

propre main et tu seras le seul à la lire. Si tu es chrétien, tu feras ce que

je te demande. Sinon, pardonne-moi ce que je fais. À Dieu, ma

préférence. »

Quoique exprimée avec une

immense délicatesse, il s’agit bel et bien d’une sanction d’excommunication, et

Ambroise ne la lèvera pas tant que l’empereur n’aura pas fait pénitence.

Théodose le sait, surtout, il admet que l’évêque a raison. Alors, publiquement,

il demandera pardon. Après ce Noël, rien ne sera plus comme avant car la loi

divine l’emportera sur les caprices des puissants. Grâce à Dieu !

Lire aussi :Cette

prière de saint Ambroise dont les paroles sont pleines d’amour pour Jésus

Lire aussi :Notre

Dame de Myans veille sur la montagne

Lire aussi :Saint

Satyre, le mal nommé

Saint Ambroise,

Évêque et docteur de

l'Église

Ambroise naquit (vers

340) à Trèves où son père était préfet du prétoire pour les Gaules. A la mort

de son père, sa mère qui était une pieuse chrétienne, vint habiter Rome avec

ses trois enfants1. Après des études classiques et juridiques, Ambroise

parcourut rapidement une brillante carrière administrative. Ses plaidoiries

ayant attiré sur lui l’attention, le préfet du prétoire de Valentinien I° le nomma

gouverneur de l’Emilie et de Ligurie, en résidence à Milan, avec le titre

consulaire (374).

L'évêque légitime de

Milan, saint Denis, était mort en exil, et l'intrus arien Auxence, qui venait

de mourir, avait, durant près de vingt ans, opprimé les catholiques. Survenant,

comme un pacificateur, dans une élection épiscopale que des divergences

tumultueuses rendaient difficile, Ambroise quoique simple catéchumène, sur le

cri d’un enfant, fut acclamé évêque et malgré ses résistances, ne put se

dérober à une charge aussi lourde qu’imprévue. Les évêques d’Italie et

l’Empereur donnèrent leur approbation au choix du peuple de Milan. Ambroise fut

baptisé et, huit jours plus tard, fut consacré évêque (7 décembre 374).

Devenu chrétien et

évêque, Ambroise s’initia par une étude incessante et approfondie à la doctrine

qu`il avait mission d’enseigner ; il se dépouilla au profit des pauvres de son

riche patrimoine, il racheta les captifs en vendant les vases de son église, et

se fit l'homme de tous. Son éloquence qui captivait la foule, attira Augustin

et dissipa les derniers doutes du futur évêque d'Hippone : « Je considérais

Ambroise lui-même comme un homme heureux, au regard du monde, d'être si fort

honoré par les plus hauts personnages. Il n'y avait que son célibat qui me

paraissait chose pénible. Quant aux espérances qu'il portait en lui, aux

combats qu'il avait à soutenir contre les tentations inhérentes à sa grandeur

même, aux consolations qu'il trouvait dans l'adversité, aux joies savoureuses

qu'il goûtait à ruminer Votre Pain, avec cette bouche mystérieuse qui était

dans son cœur ; de tout cela je n'avais nulle idée, nulle expérience. Et il

ignorait pareillement ces agitations et l'abîme où je risquais de choir. Il

m'était impossible de lui demander ce que je voulais, comme je le voulais ; une

foule de gens affairés, qu'il aidait dans leur embarras, me dérobait cette

audience et cet entretien. Quand il n'était pas occupé d'eux, il employait ces

très courts instants à réconforter son corps par les aliments nécessaires, ou

son esprit par la lecture. Lisait-il, ses yeux couraient sur les pages dont son

esprit perçait le sens ; mais sa voix et sa langue se reposaient. Souvent quand

je me trouvais là, - car sa porte n'était jamais défendue, on entrait sans être

annoncé, - je le voyais lisant tout bas et jamais autrement. Je demeurais assis

dans un long silence, - qui eût osé troubler une attention si profonde ? - puis

je me retirais, présumant qu'il lui serait importun d'être interrompu dans ces

rares moments dont il bénéficiait pour le délassement de son esprit, quand le

tumulte des affaires d'autrui lui laissait quelque loisir. »

L'action d'Ambroise,

évêque de la seconde ville d’Occident, s'exerçait bien au delà de son diocèse.

Défenseur de la doctrine orthodoxe, il assista au concile d'Aquilée (38l) où

furent déposés les évêques ariens Palladius et Secundianus, il présida, en 38l

ou en 382, un concile des évêques du vicariat d'Italie qui condamna

l'apollinarisme2 ; il se rencontra avec saint Epiphane de Salamine et Paulin

d'Antioche au concile romain de 382, et dans les Actes, il est nommé le premier

après le pape saint Damase. En 390, Ambroise tint à Milan, contre Jovinien, un

concile où la sentence portée l'année précédente par les évêques des Gaules

contre les ithaciens3 fut confirmée.

Ecouté de Valentinien I°

(364-375)4, Ambroise le fut surtout de Gratien (375-383) qui le considérait

comme son père, et ensuite de Valentinien II (3755-392). C’est peut être à

l’instigation d’Ambroise que Gratien reprit la lutte contre le paganisme qui

avait été suspendue sous Valentinien I° : outre qu’un édit supprima les revenus

des collèges de prêtres et de vestales, Gratien leur enleva les allocation

cultuelles et les biens-fonds ; enfin, il fit ôter l’autel et la statue de la

Victoire sous laquelle les sénateurs se réunissaient depuis le règne d’Auguste.

Ambroise eut beaucoup d’influence sur Valentinen II, successeur de Gratien.

La mère de Valentinien

II, l'arienne Justine, rencontra dans l'évêque de Milan un adversaire

inflexible ; Ambroise refusa à l'Impératrice la basilique Porcia et, à défaut

de celle-ci, la basilique neuve qu'elle exigeait pour les ariens (385 et 386) ;

il répondit aux envoyés de l’Empereur : « Si l’Empereur me demandait ce qui est

à moi, mes terres, mon argent, je ne lui opposerais aucun refus, encore que

tous mes biens soient aux pauvres. Mais les choses divines ne sont point sous

la dépendance de l’Empereur. S’il vous faut mon patrimoine, prenez-le. S’il

vous faut ma personne, la voici. Voulez-vous me jeter dans les fers, me

conduire à la mort ? J’accepte tout avec joie... » Enfermé dans l’église, il

exhorta le peuple à résister et, ayant mis les soldats de son côté, la cour dut

se retirer. Ambroise s'opposa à la loi qui rendait la liberté aux adhérents du

concile de Rimini, et interdisait, sous peine de mort, aux catholiques toute

résistance. Ambroise bravait les menaces d'exil et récusait les juges qu'on

voulait lui donner ; « L’Empereur est dans l’Eglise, il n’est pas au-dessus de

l’Eglise. Un bon empereur recherche l’assistance de l’Eglise, il ne la refuse

pas. Je le dis avec humilité mais je le publie aussi avec fermeté. » Ambroise

subit enfin des tentatives d'assassinat.

Ambroise cependant était

allé défendre à Trèves, auprès de l’usurpateur Maxime6, meurtrier de Gratien,

les intérêts de Valentinien II (383) ; en 387, il tenta une seconde démarche,

qui n’arrêta point Maxime sur le chemin de l'Italie : Rome tomba au pouvoir de

l’usurpateur (janvier 388). Théodose7 battit Maxime en Pannonie et en Styrie ; quelques

semaines plus tard, retranché à Aquilé, Maxime fut tué. Ambroise qui soutenait

la politique de Théodose, se lia avec lui d’une grande amitié, sans pour autant

craindre de le réprimander lorsque Théodose outrepassait les prérogatives

impériales ou menaçait les intérêts de l’Eglise.

Après la mort de sa mère,

Valentinien II, irrévocablement gagné à la cause de la vraie foi, suivit la

direction d'Ambroise, notamment en s’opposant au rétablissement de la statue de

la Victoire dans le Sénat que Gratien avait fait enlever et dont les sénateurs

païens, conduits par Symmaque et le le préfet du prétoire d’Italie, demandaient

le rétablissement.8

« Ils viennent se

plaindre de leurs pertes, eux qui furent si peu économes de notre sang, et qui,

de nos églises ont fait des ruines... Ils réclament de vous des privilèges,

quand, hier encore, les lois de Julien9 nous refusaient le droit dévolu à tous

de parler et d’enseigner... La présente cause est celle de la religion,

j’interviens donc en tant qu’évêque... Si une décision contraire est prise,

nous ne pourrons, nous évêques, nous en accommoder d’un cœur léger, ni

dissimuler notre opinion. Il vous sera loisible de vous rendre à l’église, mais

vous n’y trouverez point de prêtre ou il ne sera là que pour protester10. »

Ambroise fut l'ami de

Théodose, mais un ami qui ne se tut et ne faillit jamais. En 388, il l'avait

décidé à retirer un édit qui ordonnait aux chrétiens de Callinique11, en

Mésopotamie, de rebâtir une synagogue.

Après le massacre de

Thessalonique, décrété dans une heure de fièvre furieuse pour venger la mort de

quelques fonctionnaires impériaux, Ambroise avait interdit l’entrée de son

église à Théodose et lui avait imposé une pénitence publique. « L’Empereur, de

retour à Milan, raconte Théodoret, voulut entrer comme de coutume dans

l'église. Mais Ambroise marcha a sa rencontre en dehors du vestibule et lui

interdit de mettre le pied sur le saint parvis. » Ambroise adresse ensuite un

discours grandiloquent à Théodose, qui se retire avec des gémissements dans son

palais. Huit mois plus tard, à l'approche de la fête de Noël, l'Empereur,

accablé de tristesse, dépêche Rufin, maître des offices, vers Ambroise pour

essayer de le fléchir, mais en vain. Théodose se décide alors à venir implorer

lui-même son pardon. Ambroise lui impose l'obligation de promulguer une loi

portant que toute sentence de confiscation ou de mort ne deviendra exécutoire

qu’au bout de trente jours, après avoir été de nouveau examinée et confirmée.

Théodose obéit et Ambroise lève l'excommunication prononcée contre lui.

L’Empereur entre dans l’Eglise et il y donne le spectacle le plus touchant

repentir. Il n'est pourtant pas encore arrivé au bout de ses humiliations :

alors qu’il s’est avancé pour recevoir la communion, jusque dans l'enceinte la plus

voisine de l'autel, Ambroise lui fit signifier par un diacre que ce lieu était

réservé aux seuls prêtres, et qu'il eût a se retirer. Théodose obéit, en

alléguant pour son excuse que les choses étaient différentes à Constantinople.

Quelques mois plus tard,

au printemps de 391, Théodose partait pour Constantinople, laissant l'Occident

aux mains de Valentinien II, qui avait alors dix-neuf ans. Depuis la mort de

Justine, le caractère du jeune Valentinien s'était affirmé de la façon la plus

favorable, et, mieux en état de se former des opinions personnelles, il rendait

pleine justice à l'admirable loyauté de l'évêque autrefois persécuté en son

nom. Aussi Ambroise donna-t-il les larmes les plus sincères à sa mémoire, quand

le jeune prince eut été étouffé à l'instigation du Goth Arbogaste12 que

Théodose trop confiant avait placé auprès de lui en qualité de magister

militum. L’assassinat de Valentinien II laissa seul maître de l'empire Théodose,

son puissant associé.

A l'égard d'Eugène, un

ancien rhéteur à qui Arbogast venait de faire conférer la dignité impériale,

Ambroise garda une attitude pleine de réserve, quoique très déférente en la

forme. A peine devenu empereur, Eugène lui avait adressé deux lettres pour

essayer de gagner sa sympathie, tant il sentait l'importance de l'appui que

l’évêque pouvait lui apporter. Les procédés équivoques d'Eugène dans les

questions d'ordre religieux, surtout la faveur de plus en plus manifeste qu'il

marquait aux partisans du vieux culte romain, disposait mal Ambroise, qui évita

soigneusement les occasions de se rencontrer avec Eugène. Bientôt l'usurpateur

tombait sous les coups de Théodose, accouru de Constantinople13. Ambroise

obtint que Théodose usât de la plus large indulgence à l'égard des partisans

d'Eugène.

Théodose mourut le 17

janvier 395 ; Ambroise prononça son oraison funèbre, à Milan, en présence

d'Honorius14 et de l'armée. Il célébra la transformation des princes, maîtres

de l'univers romain, qui étaient devenus les prédicateurs de la foi, après en

avoir été les persécuteurs et nul n'avait coopéré plus efficacement cette œuvre

que Théodose. Sa politique religieuse s'était proposé un triple objet. D'abord,

protéger l'Eglise contre toute violence ou toute indiscrétion de l'Etat :

l'Empereur n'a le droit ni de mettre la main sur les édifices sacrés, ni de

prononcer, au lieu et place des évêques, dans les choses de foi. Ensuite,

obliger le pouvoir civil à respecter la loi morale, même dans des actes

dépourvus de caractère spécifiquement religieux, et ce, sous peine des censures

de l'Église (tel est le principe dont Ambroise s'inspira dans l'affaire de

Thessalonique). Enfin sceller une étroite union entre l'Église et l'Etat, de

telle sorte que, loin de mettre sur le même pied les différents cultes, l'État

marque inlassablement, quoique sans violence ni effusion de sang, sa faveur

spéciale et unique au culte catholique et décourage tous les autres. Cette

image prestigieuse d'un empire chrétien qui hantait la pensée d’Ambroise, mit

des siècles encore avant de se réaliser.

Saint Ambroise tomba

malade, un jour qu'il dictait à Paulin, son diacre, un commentaire sur le

psaume LXIII ; un feu lui couvrit la tête en forme de petit bouclier, et de là

entra dans sa bouche comme dans sa propre demeure. Alors son visage devint

blanc comme la neige et demeura quelque temps dans cette beauté. Il ne put donc

achever l'ouvrage qu'il dictait, et bientôt après il tomba malade. Le comte

Stilicon qui était le plus puissant dans l'Empire, craignant que la mort

d’Ambroise ne causât un notable préjudice à tout l'Occident, lui envoya

plusieurs personnes d'honneur pour le porter à demander à Dieu la prolongation

de sa vie ; mais il leur dit « Je n'ai pas vécu de telle sorte parmi vous, que

j’aie honte de vivre davantage ; mais, d’ailleurs, je ne crains point de

mourir, parce que nous avons affaire à un bon maître. » Quatre de ses diacres,

s'entretenant dans un coin de sa chambre, pour savoir qui l'on pourrait élire

évêque en sa place, vinrent à nommer saint Simplicien. Ils étaient si loin et

ils parlaient si bas, qu’il ne pouvait pas les entendre ; cependant, Dieu lui

révéla ce qu’ils disaient, et il s'écria : « Il est vieux, mais il est bon. »

Simplicien était cet excellent prêtre qui avait été son conseil durant tout le

temps de son épiscopat, et il fut effectivement mis en sa place après son

décès. Saint Bastien, évêque de Todi, le visitait quelquefois dans sa maladie,

et un jour qu'il priait auprès de lui, il vit Notre-Seigneur descendre du ciel,

s'approcher de son lit et lui faire beaucoup de caresses. Ensuite, la nuit du

samedi saint, comme il priait secrètement, les bras étendus en forme de croix,

saint Honorat, évêque de Verceil, qui logeait dans une chambre au-dessus de la

sienne, entendit par trois fois une voix qui lui disait : « Lève-toi en diligence,

il passera bientôt. » Honorat se leva et lui apporta 1e corps adorable de

Jésus-Christ, qu'il reçut avec une profonde révérence, et incontinent après,

son âme, munie d'un si excellent viatique, se détacha de la prison de son corps

pour aller jouir de l'éternité bienheureuse (4 avril 397).

Son corps fut inhumé dans

sa cathédrale avec l'honneur dû à la grandeur de ses mérites. Plusieurs eurent

des visions qui marquaient la gloire qu'il possédait déjà dans le ciel. Surtout

il y en eut qui virent une étoile rayonnante élevée au-dessus de son cercueil.

Les démons n’en osaient approcher mais les possédés que l’on y traînait par force,

étaient aussitôt délivrés.

Saint Ambroise fut durant

sa vie une grande autorité morale grâce à la noblesse de son caractère, à la

sainteté de sa vie, à la fermeté et à la droiture de sa conduite, mais aussi à

sa science des affaires et à son art de gouverner. Excellent magistrat devenu

homme d’église, il ne perdit pas ses premières aptitudes, qu’il élargit encore.

Esprit éminemment pratique, pondéré, puisant dans le droit le sens de la

justice, mais tempérant par la charité ce que cette justice pouvait avoir de

froid et de dur. Tous ceux qui l’approchèrent, subirent son influence ou même

l’aimèrent passionnément.

Le menu peuple dont, tout

le long du jour, il accordait les procès, il lui était dévoué jusqu’au sang. «

Si Ambroise levait le doigt, disait un jour Valentinien à ses courtisans,

vous-même me livreriez à lui pieds et poings liés. » Milan était après Rome la

véritable capitale de l’empire d’Occident, puisque l’empereur y séjournait.

Ambroise qui en était l’évêque, fut, par son prestige personnel, le plus en vue

des prélats latins.

La tournure d’esprit de

saint Ambroise est toute romaine, épanouie dans les questions morales et

pratiques. S’il traite volontiers des questions dogmatiques, il ne s’élève pas

aux spéculations ingénieuses, préférant développer l’argument scripturaire et

traditionnel. « Saint Ambroise, dit Fénelon15, suit quelquefois la mode de son

temps. Il donne à son discours les ornements qu'on estimait alors. Mais, après

tout, ne voyons-nous pas saint Ambroise, nonobstant quelques jeux de mots,

écrire à Théodose avec une force et une persuasion inimitables ? Quelle

tendresse n'exprime-t-il pas quand il parle de son frère Satyre ! »

Saint Ambroise est, dans

son exégèse, généralement allégoriste, c’est-à-dire que au lieu d’expliquer,

comme saint Jean Chrysostome, le sens littéral du texte sacré, il y cherche

plutôt les enseignements moraux et ascétiques cachés sous l’histoire et les

faits, ou les mystères, les personnages chrétiens dont l’Ancien Testament nous

présente la figure. Cette méthode exigeait de sa part moins d’études ; il en

avait des modèles tout prêts : et d’autre part, elle lui paraissait plus propre

à l’enseignement des fidèles. C’est une des raisons qui expliquent qu’il ait

commenté plus volontiers l’Ancien Testament que le Nouveau, vis-à-vis duquel il

était tenu à plus de réserve. Ses commentaires ne sont d’ailleurs, la plupart

du temps, comme beaucoup de ses autres ouvrages, que des réunions d’homélies ou

de discours prononcés sur les Livres saints. Notons, parmi les plus

intéressants, les six livres sur l’Hexammeron c’est-à-dire sur l’œuvre des six

jours, ouvrage imité de saint Basile, mais où il ne montre pas le même sens des

beautés de la nature que l’auteur grec. Puis le plus long de ses traités,

l’Exposé sur l’évangile de saint Luc en dix livres. Même si saint Augustin a

formulé quelques réserves sur cet écrit, probablement en raison de l’idée

qu’Ambroise s’y fait des peines de l’enfer, le Moyen-Age l’a cependant beaucoup

lu et copié.

Saint Ambroise est plus

un catéchiste qu’un théologien. Parmi ses œuvres se trouvent quelques écrits

doctrinaux : par exemple, un traité De la foi, c’est-à-dire sur la Trinité,

composé pour Gratien en 376 et 379 ; un traité du Saint Esprit, calqué sur

celui de Didyme l’Aveugle et composé pour le même Gratien en 381 ; deux livres

Sur la pénitence (vers 384), contre les novatiens ; mais surtout le traité Des

mystères (De mysteriis) qui expose, sous forme de catéchèse, la doctrine sur le

baptême, la confirmation et l’eucharistie. La doctrine de la

transsubstantiation y est enseignée aussi clairement que dans les catéchèses de

saint Cyrille de Jérusalem.

En 374, Valentinien I°

est empereur d’Occident ; Valens, son frère, gagné à l’arianisme, est empereur

d’Orient. Valentinien meut en 375, laissant deux enfants, l’un, Gratien, d’une

première femme nommée Severa, l’autre, Valentinien II, d’une seconde femme,

Justine, gagnée elle aussi à l’arianisme. La Cour réside à Milan, et le jeune

Gratien, devenu empereur à seize ans, donne toute sa confiance à Ambroise, sans

qui il ne fait rien d’important. En 378, Valens est battu par les Goths et tué

à Andrinople. Pour lui succéder, Gratien choisit, en 379, Théodose. En 383,

Maxime se révolte dans les Gaules, et Gratien est assassiné à Lyon. Son frère

Valentinien II lui succède et, sur la demande de Justine, Ambroise va trouver

l’usurpateur Maxime à Trèves, et l’empêche d’envahir l’Italie. Une seconde fois

probablement en 384-385, il fait le même chemin, mais par la faute de la Cour

ne réussit pas dans son ambassade. Il faut que Théodose intervienne et batte en

388, l’armée de Maxime qui est tué. La paix ne dura que quatre ans. En 392,

nouvelle révolte d’Arbogast dans les Gaules. Valentinien II qui s’y est rendu,

et qui sent sa vie en danger, appelle Ambroise pour lui donner le baptême.

Ambroise part une troisième fois ; mais, avant qu’il arrive, Valentinien est

assassiné à Vienne le 15 mai 392. Arbogast fait proclamer empereur le rhéteur

Eugène. De nouveau, Théodose intervient et les écrase tous deux à la bataille

d’Aquilée en septembre 394. Le rôle diplomatique d’Ambroise est terminé. Mais,

pendant ce temps, il a dû défendre le christianisme, l’orthodoxie et aussi la

discipline ecclésiastique. En 381, il prend une part prépondérante au concile

d’Aquilée ; de 383 à 387, il se trouve en relation avec Augustin et contribue à

le convertir. A partir de 382, les sénateurs païens, sous la conduite de

Symmaque, assiègent les différents empereurs pour obtenir le rétablissement

dans la salle des séances de l’autel de la Victoire enlevé par l’ordre de

Gratien. Par trois fois, Ambroise fait échouer leurs efforts. Puis il s’oppose

aux tentatives de Justine et des Ariens pour se faire livrer l’une au moins des

églises catholiques de Milan, la basilique Portia surtout, en 386, et institue,

à cette occasion, le chant des psaumes et des hymnes à deux chœurs. Il proteste

en 385, contre l’immixtion des évêques dans la condamnation à mort des

priscillianistes, obtient de Théodose, en 388, que l’évêque de Callinicus ne

soit pas obligé à rebâtir la synagogue juive détruite par les catholiques et -

suprême triomphe - fait accepter à l’empereur de se soumettre à la pénitence

publique pour le massacre de Tessalonique en 390. Sa mort se place le 4 avril

397. On célèbre sa fête le 7 décembre.

1 Deux garçons : Ambroise

et Satyre ; une fille : Marceline.

2 L'apollinarisme est une

hérésie christologique professée par Apollinaire de Laodicée qui refusait au

Christ un âme humaine, jugée incompatible avec sa divinité.

3 Les ithaciens,

disciples de l’évêque Ithace d’Ossonoba (Espagne), fort liés à l’usurpateur

Maxime, qui prétendent que le pouvoir séculier doit régler les causes

ecclésiastiques.

4 Valentinien I° est

empereur d’Occident ; Valens, son frère, gagné à l’arianisme, est empereur

d’Orient. Valentinien meurt en 375, laissant deux enfants, l’un, Gratien, d’une

première femme nommée Severa, l’autre, Valentinien II, d’une seconde femme,

Justine, gagnée elle aussi à l’arianisme.

5 Fils et successeur de

Valentinien I°, il succéda à son père à l’âge de quatre ans et partagea

l’empire d’Occident avec son frère Gratien.

6 Maxime fut proclamé

empereur par les légions de Bretagne (383) et s’établit à Trèves.

7 Théodose, nommé Auguste

par Gratien, reçut le gouvernement de l’empire d’Orient (379).

8 Symmaque rédigea une

pétition, écrite, pour mission défendre « les institutions des ancêtres, les

droits et les destinées de la patrie. » La pétition fut remise à l’Empereur par

une délégation sénatoriale. « Eh quoi ! s'écriait Symmaque, la religion romaine

est-elle mise en dehors du droit romain ? Les affranchis touchent les legs qui

leur sont faits ; on ne conteste plus aux esclaves les avantages légaux que les

testaments leur concèdent : ct de nobles vierges, les ministres d'un culte

sacré, seraient exclus des biens qui leur arrivent par succession ? Que leur

sert-il de dévouer leur chasteté au salut public, de donner à l'éternité de

l'Empire la protection d'en haut, d'attacher à vos armes, à vos aigles, des

puissances amies, de faire pour tous des voeux efficaces, s'ils ne jouissent

même pas du droit commun ? » Et, évoquant la grande image de Rome, il lui

faisait prononcer des paroles empreintes d’une majestueuse tristesse pour

déplorer les attentats dont des traditions si vénérables étaient victimes. Lu

dans le conseil de l'Empereur, la pétition produisit grand effet : chrétiens et

païens parurent un instant d'accord pour donner une réponse favorable.

9 Julien l’Apostat, neveu

de Constantin, avait cinq ans (337) lorsque le carnage dynastique qui suivit la

mort de Constantin, le rendit spectateur de l'assassinat de toute sa parenté

mâle, à l'exception de son demi-frère Gallus. Très sensible et frustré

d’affection, il fut élevé par l'évêque arien Eusèbe de Nicomédie et un eunuque

goth, Mardonius. Exilé avec Gallus dans la forteresse de Macellum (Cappadoce),

il y fut dans la solitude et y perdit la foi chrétienne ; il s'enthousiasma

pour la vieille religion païenne. Il commença à lire les auteurs païens dont le

philosophe néoplatonicien Jamblique. En 351, libre de voyager, il gagna

Constantinople et séjourna à Nicomédie, où il rencontra des disciples de

Jamblique qui l'initièrent aux mystères néoplatoniciens et à la magie

théurgique. En 354 Gallus fut exécuté et Julien fut emprisonné à Milan. Peu

après, il obtint la permission de visiter les écoles philosophiques à Athènes.

Brusquement rappelé à Milan, il y reçut des missions militaires qu'il remplit

avec succès. Vainqueur à Strasbourg (357), il rétablit l'administration romaine

en Gaule et, à Lutèce, il fut proclamé empereur par l'armée (360). La guerre

civile ne fut évitée que par la mort de Constance II (361). Unique empereur à

la fin de 361, Julien se lança aussitôt dans l'application de son programme de

réforme. Son plan consistait à affaiblir l'Église de toutes manières et à

organiser en contre-église le culte païen traditionnel. Pour faire pièce à

l'universalité du christianisme, il favorisa les cultes des dieux locaux et

nationaux ; il accorda aux Juifs une bienveillante indulgence, leur laissant

espérer la reconstruction du Temple de Jérusalem. Il augmenta la confusion des

chrétiens en rappelant sur leurs sièges les évêques ariens exilés, en privant

l'Église de ses privilèges administratifs et financiers, en réservant les

postes d'enseignement officiels aux professeurs païens. Il chercha à rétablir

partout le culte païen traditionnel, ordonna la réouverture des temples et

l'organisation du clergé en église hiérarchisée ; il favorisa l'élaboration

d'une théologie philosophique. Cette politique violemment antichrétienne le

rendit très impopulaire. L'incident de Daphné (violation par Julien du tombeau

du saint martyr Babylas, riposte des chrétiens par l'incendie du temple

d'Apollon) illustre les difficultés qu'il rencontra. Il mourut le 26 juin 363 en

combattant contre les Perses.

10 Saint Ambroise :

lettre XVII, § 4 & 13.

11 Callinicos fut fondée

par Alexandre le Grand qui lui donna le nom de Nicéphorium. Séleucus Callinus,

roi de Syrie (246-225), la restaura et l'appela Callinicos. Déjà fortifiée sous

Julien l'Apostat, elle le fut encore davantage par Léon I° (457-474) ; c'est pourquoi

des auteurs byzantins lui donnent aussi le nom de Léontopolis. Le site de la

ville se trouve sur la rive gauche de l'Euphrate, à 15 km. à l'ouest du

confluent du Bilichus (Bélik) avec le fleuve. La plaine voisine fut le théâtre

de deux grandes batailles livrées aux Perses par Belisaire (531) et l'empereur

Maurice (583). En 388, le comte d'Orient ayant accusé l'évêque de Callinicos

d'avoir fait incendier la synagogue de la ville, l'em¬pereur Théodose condamna