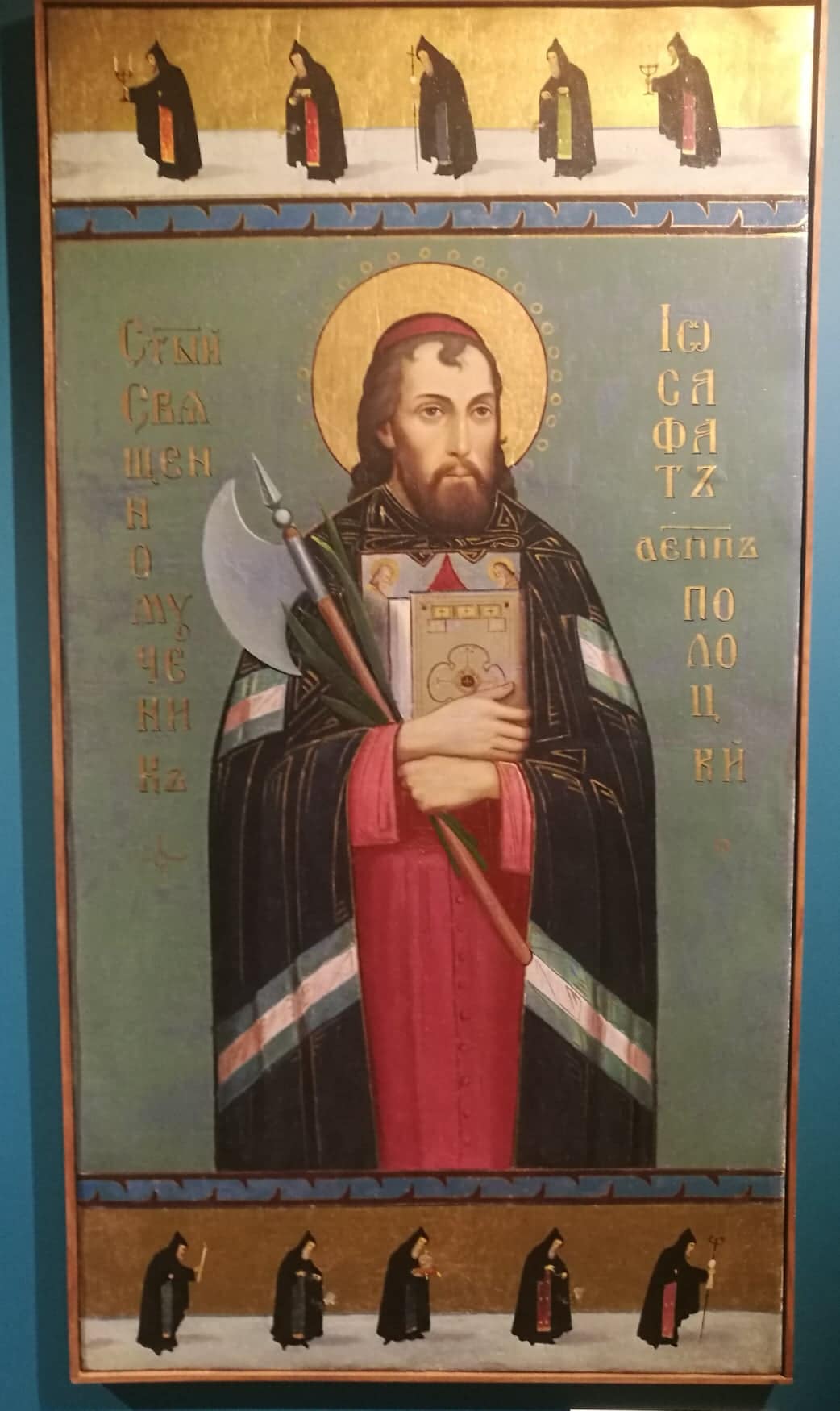

Devotional painting of Saint Josaphat Kuncevyc

Saint Josaphat Kuntsevych

Évêque basilien et martyr

à Vitebak (+ 1623)

- "Alors que l'Église célèbre le saint ukrainien Josaphat Kuncewycz, le Pape a pris le temps de saluer les pèlerins ukrainiens et les moines basiliens venus de divers pays pour célébrer le quatrième centenaire du martyre de l'évêque de Polotzk..." prière du Pape pour la paix, mémoire de saint Josaphat, le 12 novembre 2023.

Jean Kuntsevych, né en Volhynie, en 1580. Il est encore adolescent à l'époque de l'Union de Brest (1596) où une partie de l'Eglise d'Ukraine se rattache à Rome et constitue l'Eglise gréco-catholique ou Eglise ruthène. A vingt ans, il entre au monastère de la Sainte Trinité à Vilnius, alors dans le royaume polono-lituanien, dans un monastère de l'ordre basilien et prend le nom de Josaphat. A trente ans, il en devient l'un des supérieurs. Déchiré en lui-même par cette séparation entre catholiques romains et orthodoxes, il se dévoue à la cause de l'unité, polémique avec les orthodoxes tout en gardant une grande douceur. Nommé évêque de Polock en 1617, il se trouve dans une région où les antagonismes sont exacerbés plus encore par des considérations politiques et culturelles que par des points de vue religieux. Au cours d'une émeute provoquée par des intégristes orthodoxes, alors qu'il accomplissait une visite pastorale à Vitebsk, il est lynché et jeté dans le fleuve, martyr pour son attachement à l'Eglise romaine.

Béatifié par le pape Urbain VIII le 16 mai 1643 et canonisé par le bienheureux Pie IX le 29 juin 1867, il est le premier saint des Eglises uniates à être canonisé à Rome.

Ses reliques se trouvent sous l'autel saint Basile dans la basilique Saint

Pierre du Vatican.

Voir aussi

- lettre apostolique du pape Jean-Paul II à l'occasion du quatrième centenaire de l'union de Brest, le 12 novembre

1995, mémoire de saint Josaphat.

Né dans l'orthodoxie, Jean Kuncewicz adhéra, dès sa jeunesse, à l'union

catholique et, devenu évêque de Polotz sous le nom de Josaphat, il déploya un

zèle constant à garder son troupeau dans l'unité, attentif à donner toute sa

splendeur à la liturgie byzantine slave. Au cours d'une visite pastorale à

Vitebsk, en 1623, il fut massacré par une foule déchaînée contre lui et mourut

pour l'unité de l'Église et la défense de la vérité catholique.

Martyrologe romain

400e anniversaire du

martyre de saint Josaphat Kuncewycz, connu sous le nom de "martyr de

l'unité"... être tolérant, c'est toujours rechercher la vérité de Dieu qui

nous a créés frères et sœurs...

interview accordée à Radio Vatican-Vatican News, le père Robert

Lisseiko, OSBM, supérieur général de l'Ordre Basilien de Saint Josaphat 12

novembre 2023

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/14/Saint-Josaphat-Kuntsevych.html

Josaphat

Kuntsevych Йосафат Кунцевич Josafat Kuncevic Basiliani Via San Giosafat Roma

1991

Picture taken by Rev. Josaphat Vladimir Timkovic, OSBM, in 1991.

Saint Josaphat

Archevêque de Polotsk et martyr

(1584-1623)

Josaphat naquit à

Wladimir, ville de Pologne, d'une famille modeste. Il reçut le nom de Jean au

baptême. Sa pieuse mère déposa dans son coeur les germes d'une vertu précoce.

Lorsqu'elle n'apercevait pas son fils à la maison, elle était sûre de le

trouver en prière dans l'église. Ses parents le proposaient à ses frères et

soeurs comme un vivant modèle de vertus. Il entrait à vingt ans dans l'Ordre

des Basiliens-Unis de Pologne où il prit le nom de Josaphat.

Secrètement vendu au

schisme, le supérieur de la communauté tenta vainement de porter Josaphat à la

révolte contre le Saint-Père. Au grand mécontentement des schismatiques qui

accablèrent le Saint d'injures et de sarcasmes, Josaphat dénonça

l'archimandrite au métropolitain qui fut déposé de sa charge. Quoique simple

diacre, Josaphat fit preuve d'un zèle ardent pour la conversion des non-unis et

en ramena un bon nombre dans le giron de l'Église. Ordonné prêtre, le saint

basilien se fit l'apôtre de la contrée, s'appliqua au ministère de la

prédication et de la confession tout en pratiquant une exacte observance de ses

Règles. Dieu avait doté saint Josaphat d'un talent particulier pour assister

les condamnés à mort. Il visitait aussi les malades pauvres, lavait leurs pieds

couverts d'ulcères et tâchait de procurer des remèdes et de la nourriture à ces

miséreux.

Nommé archimandrite du couvent

de la Trinité qui se composait surtout de jeunes religieux, il les forma à la

vie monastique avec une vigilance toute paternelle. A l'âge de trente-huit ans,

saint Josaphat Koncévitch fut sacré archevêque de Polotsk à Vilna.

Pendant que le saint archevêque

se trouvait à la diète de Varsovie où plusieurs évêques avaient été convoqués,

un évêque schismatique s'empara de son siège à l'improviste. Saint Josaphat

s'empressa de revenir vers son troupeau pour rappeler les brebis rebelles à

l'obéissance. Au moment où il voulut prendre la parole, la foule excitée par

les schismatiques se rua impétueusement sur lui. Il aurait été impitoyablement

massacré si la force armée n'était intervenue pour le dégager des mains des

insoumis.

Le matin du 12 novembre

1623, alors qu'il priait dans la chapelle du palais épiscopal de Vitebsk, la

foule en furie envahit la sainte demeure. Saint Josaphat accourut promptement

au bruit de l'émeute: «Si vous en voulez à ma personne, dit-il aux assassins,

me voici.» Deux hommes s'avancèrent alors vers lui; l'un d'eux le frappa au

front avec une perche et l'autre lui asséna un coup de hallebarde qui lui

fendit la tête. Enfin, deux coups de fusil lui percèrent le crâne. Saint

Josaphat avait quarante-quatre ans lorsqu'il fut victime de ce crime sacrilège.

Résumé O.D.M.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_josaphat.html

Icone de Saint Josaphat - Icons amb Sant Josafat

12 novembre 1923

Lettre encyclique Ecclesiam

Dei

À l’occasion du IIIe

centenaire de la mort de saint Josaphat, martyr, archevêque de Polotsk, pour le

rite oriental.

accueil Formation Magistère Encyclique

Ecclesiam Dei

Aux Patriarches, Primats,

Archevêques, Évêques et autres ordinaires en paix et en communion avec le Siège

Apostolique,

Pie XI, Pape

Vénérables frères, salut

et bénédiction apostolique.

L’Eglise, par un

admirable dessein de son divin Fondateur, devait dans la plénitude des temps

constituer comme une immense famille embrassant l’ensemble du genre

humain ; Dieu a voulu, nous le savons, qu’on la pût reconnaître à divers

signes caractéristiques : notamment elle devait être tout à la fois une et

universelle.

De fait, quand le Christ

dit aux apôtres : Toute puissance m’a été donnée dans le ciel et sur

la terre : allez donc, enseignez toutes les nations (Mt 28, 18–19), il

ne s’est pas contenté de transmettre à eux seuls la mission qu’il avait

lui-même reçue de son Père ; il a voulu de plus que le collège apostolique

fût parfaitement un, et que les membres en fussent rattachés les uns aux autres

par un double lien très étroit : lien intime de la même foi et de la même

charité, qui a été répandue dans les cœurs… par l’Esprit-Saint (Rm 5,

5) ; lien extérieur de l’autorité exercée par un seul sur tous, le

Christ ayant conféré la primauté sur les apôtres à Pierre, comme au principe

perpétuel et au fondement visible de l’unité. Celle unité, Jésus la leur

recommanda avec les plus vives instances au seuil de la mort ; c’est elle

encore que, par une prière très ardente, il implora de son Père et qu’il

obtint, exaucé pour sa piété (He 5, 7).

Aussi l’Eglise s’est

formée et développée en « un seul corps », corps vivifié et animé par

un seul esprit ; corps dont la tête est le Christ, et c’est par le

Christ que le corps entier est coordonné et uni, grâce aux liens des membres

qui se prêtent un mutuel secours (Ep iv, 5, 15, 16).

Mais, pour la même

raison, ce corps a une tête visible qui est le Vicaire du Christ sur la terre,

le Pontife romain. C’est à lui, en tant que successeur de Pierre, qu’est

adressée d’âge en âge la parole du Christ : Sur cette pierre je

bâtirai mon Eglise (Mt 16, 18) ; toujours fidèle à ce rôle de

lieutenant que le Christ a confié à Pierre, le Pape ne cesse de confirmer ses

frères, quand il en est besoin, et de paître tous les agneaux et toutes les

brebis du Seigneur. Mais il n’est rien à quoi la haine de l’homme ennemi se

soit jamais autant acharnée qu’à rompre dans l’Eglise cette unité de

gouvernement qui est inséparable de « l’unité de l’esprit dans le lien de

la paix » (Ep 4, 3). Si jamais il n’est parvenu à prévaloir contre

l’Eglise elle-même, celle-ci s’est vu néanmoins arracher de son sein et de son

étreinte un grand nombre de ses enfants et jusqu’à des peuples entiers. Ces

malheurs sont dus pour une part très notable à des rivalités de nation à

nation, à des lois d’où étaient bannies la religion et la piété, enfin à

d’ardentes convoitises des biens périssables.

La plus grave rupture, la

plus déplorable de toutes, est celle qui sépara de l’Eglise œcuménique l’empire

de Byzance. On put croire que les Conciles de Lyon et de Florence avaient rétabli

l’unité ; mais, depuis, la scission s’est produite de nouveau et elle dure

aujourd’hui encore, au grand détriment des âmes. Il s’en est suivi que Byzance

a entraîné dans les sentiers d’égarement et de perdition d’autres peuples

orientaux parmi lesquels les Slaves ; et pourtant ceux-ci étaient

demeurés » plus longtemps que les autres, fidèles à leur Mère l’Eglise. Il

est prouvé, en effet, que ces peuples conservèrent certaines relations avec le

Siège apostolique même après le schisme de Michel Cérulaire, et que, après une

interruption causée par L’invasion des Tartares puis des Mongols, ils reprirent

ces rapports et les maintinrent jusqu’au jour où ils en furent empêchés par

l’opiniâtre rébellion des princes.

En ces conjonctures, les

Pontifes romains ont rempli tout leur devoir ; certains même se

consacrèrent avec un zèle et un dévouement tout particuliers au salut des

Slaves orientaux : tel Grégoire VII, qui, en une lettre adressée au prince

de Kiev, « Dimitri, roi de Russie, et à la reine son épouse », sur la

demande que lui en avait faite à Rome leur fils au moment de leur avènement au

trône, leur souhaita très affectueusement toutes les bénédictions du ciel [1]; tel

encore Honorius III, envoyant des légats à Novgorod, imité sur ce point par

Grégoire IX et, peu après, par Innocent IV, qui y délégua un personnage d’un

courage et d’une vaillance remarquable, Jean du Plan de Carpin, gloire de

l’Ordre franciscain.

Ce zèle empressé de Nos

prédécesseurs porta ses fruits en 1255, année qui vit rétablir la concorde et

l’unité ; pour célébrer cet événement, Opizon, abbé, au nom et par les

pouvoirs du même Pontife, dont il était légat, conféra en des fêtes grandioses

les insignes royaux à Daniel, fils de Romain. Aussi, en accord avec la

tradition et les usages vénérables des anciens Slaves orientaux, on put, au

Concile de Florence, entendre le métropolite de Kiev et de Moscou, Isidore,

cardinal de la Sainte Eglise Romaine, jurer au nom de ses compatriotes fidélité

inviolable à l’unité catholique dans la communion avec le Siège apostolique.

L’union cimentée de

nouveau se maintint à Kiev un certain nombre d’années : elle allait être

brisée encore pour divers motifs, auxquels vinrent s’ajouter les

bouleversements politiques qui marquèrent le début du XVIe siècle. Elle

fut heureusement rétablie en 1545 et promulguée l’année suivante à la

Conférence de Brest, sur l’initiative et grâce aux démarches de métropolite de

Kiev et des autres évêques ruthènes ; Clément VIII leur fit l’accueil le

plus affectueux et, par la constitution Magnus Dominus, invita tous

les fidèles à rendre grâces à Dieu, « dont toutes les pensées sont des

pensées de paix, et qui veut que tous les hommes soient sauvés et parviennent à

la connaissance de la vérité ».

Pour que cette unité et

cette bonne entente pussent se maintenir à jamais, la Providence si sage de

Dieu les marqua du sceau de la sainteté et du martyre. Cette auréole était

réservée à l’archevêque de Polotsk, Josaphat, du rite slave oriental, que nous

saluons a juste titre comme la plus belle gloire et le plus ferme soutien de

l’Orient slave ; car on trouvera difficilement quelqu’un qui ait fait plus

honneur au nom slave et plus efficacement travaillé au salut de ces populations

que Josaphat, leur pasteur et apôtre, qui a versé son sang pour l’unité de la

Sainte Église.

Puisque nous voici au

troisième centenaire de ce très glorieux martyre, ce Nous est une très vive

joie de rappeler le souvenir de ce si grand saint ; daigne le Seigneur,

cédant aux prières plus ferventes des fidèles, « susciter dans son Église

L’esprit qui remplissait le bienheureux martyr et pontife Josaphat… et qui le

porta à donner sa vie pour ses brebis » [2] ; puisse s’accroître le zèle du

peuple chrétien pour l’unité, et ainsi l’œuvre principale de Josaphat se

poursuivre jusqu’au jour où se réalisera le vœu du Christ et de tous les

saints : Et il n’y aura qu’un seul bercail et un seul Pasteur. (Jn

10, 16)

Né de parents séparés de

l’unité catholique, Josaphat, qui reçut au saint baptême le nom de Jean, se

consacra à la piété dès sa plus tendre enfance. Tout en suivant la splendide

liturgie slave, il recherchait avant toutes choses la vérité et la gloire de

Dieu ; à cette fin, et en dehors de toute considération humaine, il se

tourna tout enfant vers la communion de l’unique Église œcuménique ou

catholique, se considérant comme appelé à la communion de cette Église par le

baptême même qu’il avait validement reçu. Bien plus, se sentant poussé par une

inspiration du ciel à travailler au rétablissement de la sainte unité dans le

monde entier, il comprit qu’il pouvait y contribuer dans une très large mesure

s’il conservait dans le cadre de l’unité de l’Église universelle le rite slave

oriental et l’Ordre des moines Basiliens.

C’est pourquoi, reçu en

1604 parmi les Basiliens et ayant échangé le nom de Jean pour celui de

Josaphat, il s’adonna tout entier à l’exercice de toutes les vertus,

particulièrement de la piété et de la mortification.

La vue de Jésus crucifié

avait fait naître en lui, dès son enfance, l’amour de la croix, qu’il ne cessa

ensuite de pratiquer à un degré éminent.

D’après Joseph Velamin

Russky, métropolite de Kiev, qui avait été archimandrite de ce monastère,

« il fit en peu de temps de tels progrès dans la vie monastique qu’il put

servir de maître aux autres ». Aussi, à peine ordonné prêtre, Josaphat est

lui-même nommé archimandrite et placé à la tête du monastère. Pour accomplir sa

charge, il ne se contenta point de maintenir en bon état le monastère et l’église

attenante et de les fortifier contre les attaques des ennemis ; mais,

constatant qu’ils étaient presque abandonnés par le peuple chrétien, il résolut

de s’employer à l’y ramener.

Entre temps, préoccupé

avant tout de l’union de ses compatriotes avec la chaire de Pierre, il

s’enquérait de tous côtés des moyens soit de la promouvoir, soit de la

consolider ; surtout, il étudiait sans répit les livres liturgiques dont

les Orientaux, y compris les schismatiques eux-mêmes, avaient accoutumé de se

servir en accord avec les prescriptions des saints Pères.

Après cette si active

préparation, Josaphat se mit à l’œuvre de restauration de l’unité avec tant de

force tout ensemble et de douceur, et il y réussit à tel point que ses

adversaires eux-mêmes l’appelaient « ravisseur d’âmes ». Le nombre,

en effet, est étonnant de ceux qu’il ramena à l’unique bercail de Jésus-Christ,

convertis de toutes condition et origine, gens du peuple, commerçants, nobles,

préfets même et administrateurs de provinces, comme nous savons que ce fut le

cas pour Sokolinski de Polotsk, pour Tyszkievicz de Novgrodensk, pour Mieleczko

de Smolensk.

Mais il étendit bien plus

encore son action apostolique du jour où il fut nommé évêque de l’Eglise de

Polotsk. Cet apostolat a dû avoir une influence incroyable ; car on vit

Josaphat donner l’exemple d’une extrême chasteté, pauvreté et austérité ;

ii se montrait envers les pauvres d’une telle générosité qu’il alla jusqu’à

mettre en gage son omophorion pour secourir leur indigence ; se

renfermant strictement dans le domaine religieux, il ne s’ingérait en rien dans

les affaires politiques, encore que par des instances vives et réitérées on le

pressât de se charger d’intérêts et à prendre parti dans des conflits d’ordre

temporel ; enfin, il apportait à son œuvre le dévouement accompli d’un

très saint évêque, travaillant sans relâche par sa parole et ses écrits à faire

pénétrer la vérité. Il a publié en effet nombre d’ouvrages merveilleusement mis

à la portée du peuple, entre autres sur la Primauté de saint Pierre et le

Baptême de saint Vladimir, et encore une apologie de l’unité catholique, un

catéchisme selon la méthode du bienheureux Pierre Canisius, et d’autres travaux

du même genre.

Se multipliant pour

rappeler l’un et l’autre clergés à l’accomplissement attentif de ses devoirs,

il obtint peu à peu, en réveillant le zèle pour le ministère sacerdotal, que le

peuple, régulièrement instruit de la doctrine chrétienne et nourri de la parole

divine par une prédication appropriée, se reprît à fréquenter les sacrements et

les cérémonies liturgiques, et fût ramené à une vie toujours plus chrétienne.

C’est ainsi que, par une

large et abondante diffusion de l’esprit de Dieu, Josaphat consolida

merveilleusement l’œuvre d’unité à laquelle il s’était voué. Cet

affermissement, on peut même dire cette consécration, il la donna surtout le

jour où il tomba martyr de cette cause, par un acte de sa pleine volonté et

avec une admirable grandeur d’âme. La pensée du martyre était toujours dans son

esprit, fréquemment sur ses lèvres ; le martyre, il l’appela de ses vœux

au cours d’une prédication solennelle ; le martyre, enfin, il le

sollicitait comme une faveur particulière de Dieu. C’est ainsi que, peu de

jours avant sa mort, averti des embûches qui se tramaient contre lui, il dit :

« Seigneur, faites-moi la grâce de pouvoir répandre mon sang pour l’unité,

ainsi que pour l’obéissance au Siège apostolique. »

Son désir fut exaucé le

dimanche 12 novembre 1623 ; avec un visage où éclate la joie et qui

respire la bonté, il va au-devant de ses ennemis qui l’entourent, cherchant

l’apôtre de l’unité ; il leur demande, à l’exemple de son Maître et

Seigneur, de ne faire aucun mai aux siens, et se livre entre leurs mains ;

frappé avec une extrême cruauté et tombé sous leurs coups, il ne cesse jusqu’au

dernier soupir d’implorer de Dieu le pardon pour ses meurtriers.

Ce martyre si glorieux

fut fécond en résultats : notamment, il inspira une grande énergie et

fermeté aux évêques ruthènes, qui faisaient eux mois plus tard, dans une lettre

à la S. Congrégation de la Propagande, la déclaration suivante :

« Nous nous affirmons absolument prêts a donner notre vie jusqu’au sang,

comme vient de le faire l’un des nôtres pour la foi catholique. » Un

nombre considérable de schismatiques, parmi lesquels les meurtriers mêmes du

martyr, rentrèrent bientôt après dans la seule véritable Église.

Comme il y a trois

siècles, le sang de saint Josaphat doit être, aujourd’hui plus que jamais, un

gage de paix et d’unité : aujourd’hui, disons-Nous, que, dans les

malheureux pays slaves, en proie aux plus graves perturbations, la fureur de

guerres barbares multiplie les massacres fratricides. Il nous semble, en effet,

entendre ce sang crier plus haut que celui d’Abel (He 12, 24) et

s’adresser aux frères de la famille slave en empruntant les paroles du Christ

Jésus : Les brebis errent sans pasteur. J’ai pitié de la foule. (Mc

8, 2)

Et, en vérité, quel sort

affreux pèse sur les Slaves ! Dans quel dénuement absolu ils se

débattent ! Que d’exils ! Quels sanglants massacres ! Et, en

plus des corps, que d’âmes perdues ! Quand Nous considérons la situation

actuelle des Slaves, bien plus déplorable encore que celle dont se lamentait

saint Josaphat, Nous avons peine — si vive est Notre affection paternelle — à

retenir nos larmes.

Quant à Nous, pour

alléger ce poids immense d’infortunes, Nous Nous sommes appliqué, de Notre

propre initiative, à soulager ces malheureux, ne visant aucun intérêt humain,

ne faisant aucune distinction entre ces misères, préoccupé seulement de

réserver les secours les plus rapides aux nécessités les plus urgentes.

Hélas ! nos

ressources n’étaient pas à la mesure de si vastes besoins. Et Nous n’avons pu

empêcher que, au mépris de toute religion, on ne multipliât les attentats

contre la vérité et la vertu ; bien plus, çà et là, des chrétiens, et

jusqu’à des prêtres et des évêques, furent traqués pour être emprisonnés et

même massacrés.

Une bien douce

consolation rend moins pénible pour Nous le spectacle de ces maux : le

centenaire solennel du plus illustre évêque slave Nous offre, en effet, une

occasion tout indiquée de manifester les sentiments d’affection paternelle que

Nous portons à tous les Slaves orientaux et de leur rappeler le bien capital, à

savoir l’unité œcuménique de la sainte Église.

A cette unité, Nous

convions instamment Nos frères dissidents, et Nous demandons en même temps que

tous les fidèles sans exception, à l’exemple et selon les méthodes de saint

Josaphat, s’appliquent à Nous prêter, chacun dans la mesure de ses forces, le

concours de leur activité et de leur zèle. Qu’ils le comprennent bien, ce ne

sont pas tant les discussions et autres exhortations directes qui favoriseront

ce retour à l’unité, mais bien les exemples et les œuvres d’une vie sainte et,

par-dessus tout, l’amour envers nos frères slaves et les autres Orientaux,

suivant le mot de l’Apôtre : Ayez une même charité, une même âme, une

même pensée ; ne faîtes rien par esprit de rivalité ou de vaine

gloire ; mais que l’humilité vous fasse considérer les autres comme

supérieurs à vous ; que chacun recherche non ses propres intérêts, mais

ceux des autres. (Ph 2, 2–4)

Les Orientaux dissidents

ont à cet égard le devoir d’abandonner leurs antiques préjugés pour chercher à

connaître la véritable vie de l’Église, de ne point imputer à l’Église romaine

les écarts des personnes privées, écarts qu’elle-même condamne et auxquels elle

s’efforce de remédier. Les Latins, de leur côté, doivent acquérir des notions

plus complètes et plus approfondies des choses et des usages de l’Orient ;

saint Josaphat en avait une connaissance parfaite et c’est ce qui rendit son

apostolat si fécond.

Pour ces motifs, Nous

avons voulu favoriser de marques nouvelles de Notre bienveillance l’Institut

pontifical oriental, créé par Notre très regretté prédécesseur Benoit XV ;

Nous tenons, en effet, pour assuré qu’une connaissance exacte des choses amènera

une équitable appréciation des personnes en même temps qu’une sincère

bienveillance, et ces sentiments, si la charité chrétienne vient les couronner,

seront, avec la grâce de Dieu, souverainement profitables à l’unité religieuse.

Une fois pénétrés de

cette charité, tous saisiront l’enseignement divin de l’Apôtre : Il

n’y a point de distinction entre Juif et Grec ; car il n’y a qu’un même

Seigneur pour tous, riche de faveurs pour tous ceux qui l’invoquent (Rm

10, 12). Puis, ce qui vaut mieux encore, religieusement dociles aux

prescriptions du même Apôtre, ils dépouilleront et abandonneront non seulement

les préjugés, mais encore les soupçons injustifiés, les rivalités, les haines,

enfin tous les sentiments opposés à la charité chrétienne, qui sont la source

des conflits internationaux. Paul ne dit-il pas encore : N’usez point

de mensonges les uns envers les autres ; dépouillez le vieil homme ainsi

que ses œuvres, et revêtez l’homme nouveau, qui se renouvelle dans la science à

l’image de celui qui l’a créé ; il n’y a ici ni Gentil, ni Juif…; ni

Barbare, ni Scythe ; ni esclave, ni homme libre, mais le Christ est tout

et en tous (Col 3, 9–11).

C’est ainsi que, grâce au

rétablissement de la bonne entente entre les individus comme entre les peuples,

l’union pourra se réaliser parallèlement dans l’Église par la rentrée dans son

giron de tous ceux qui, pour une cause ou une autre, en sont sortis. Cette

réalisation de l’union sera obtenue non par des calculs humains, mais par la

seule charité de Dieu, qui ne fait point acception de personnes (Ac

10, 34) et qui ne met point de différence entre nous et eux (Ac 14,

9).

On verra alors tous les

peuples, ainsi rapprochés, jouir des mêmes droits, quelles que soient leur

race, leur langue ou leur liturgie : l’Église romaine a toujours

religieusement respecté et maintenu les divers rites, toujours elle a prescrit

de les conserver, s’en faisant à elle-même comme une parure précieuse,

telle cette reine couverte, d’un vêtement tissu d’or, drapée d’un manteau

aux couleurs variées (Ps 44, 10).

Et parce que cet accord

de tous les peuples de l’univers dans l’unité, œuvre le Dieu au premier chef,

ne pourra être obtenu que par le secours et la protection de Dieu, recourons

avec persévérance et ferveur à la prière, selon l’exemple et les conseils de

saint Josaphat lui-même, qui, dans son apostolat en faveur de l’unité, comptait

avant tout sur la puissance de la prière.

A l’exemple et à la suite

du saint évêque, ayons un culte tout particulier pour l’auguste sacrement de

l’Eucharistie, gage de l’unité et sa source principale ; tous ceux des

Slaves orientaux qui, après s’être séparés de l’Église romaine, conservèrent

l’amour du « mystère de la foi » et continuèrent à s’en approcher

fréquemment, ne tombèrent point dans l’impiété d’hérésies plus graves.

Nous pourrons alors

espérer voir enfin exaucer le vœu que l’Église notre Mère adresse à Dieu avec

piété et confiance à la messe du Saint-Sacrement : que Dieu, dans sa

bonté, accorde les bienfaits de l’unité et de la paix, symbolisés mystiquement

par les dons de l’oblation [3] ; ce vœu, Latins

et Orientaux le formulent pareillement dans les prières du Saint

Sacrifice : ceux-ci « demandent pour tous au Seigneur la grâce de

l’unité », ceux-là prient le Christ « d’avoir égard à la foi de son Église, et de daigner, conformément à sa propre volonté, lui donner la paix et

l’unité ».

Un autre point de contact

avec les Slaves orientaux, de nature à faciliter le rétablissement de l’unité,

est leur amour tout spécial et leur piété envers la Vierge Mère de Dieu, par où

ils se distinguent d’un grand nombre d’hérétiques et se rapprochent de nous.

Saint Josaphat, qui se signalait particulièrement dans cette dévotion à la

Vierge, plaçait également en elle une très grande confiance pour faire accepter

l’unité ; aussi avait-il coutume de vénérer, suivant l’usage des

Orientaux, une petite icône de la Vierge Mère de Dieu, que les moines

Basiliens, et ici même, à Rome, en l’église des Saints-Serge et Bacchus, les fidèles

des deux rites vénèrent avec grande dévotion sous le vocable de Reine des

pâturages (del Pascolo). Invoquons donc spécialement sous ce titre cette

Mère très aimante, et prions-la de ramener nos frères dissidents aux pâturages

du salut, où, toujours vivant dans ses successeurs, Pierre, vicaire du Pasteur

éternel, paît et gouverne tous les agneaux et toutes les brebis du troupeau

chrétien.

Enfin, recourons, pour

une si grande œuvre, au patronage de tous les saints du ciel, ceux-là surtout

qui brillèrent jadis en Orient par le renom de leur sainteté et de leur sagesse

et qui aujourd’hui sont plus spécialement l’objet de la vénération et du culte

des Orientaux.

En premier lieu,

sollicitons l’intercession de saint Josaphat : après avoir, pendant sa

vie, défendu avec un très grand courage la cause de l’unité, qu’il daigne

aujourd’hui en être auprès de Dieu le très puissant protecteur et avocat.

Quant à Nous, Nous lui

adressons la formule d’invocation composée par Notre prédécesseur Pie IX,

d’éternelle mémoire : « Puisse, ô saint Josaphat, le sang que vous

avez versé pour l’Eglise du Christ être le gage de cette union au Saint-Siège

apostolique qui fut sans-cesse l’objet de vos vœux et que jour et nuit vous

imploriez de Dieu, souverainement bon et souverainement grand. Pour que cette

union se réalise enfin, nous vous prions d’être constamment notre intercesseur

auprès de Dieu et de la cour céleste. »

Comme gage des divines

faveurs et en témoignage de Notre bienveillance, Nous vous accordons de tout

cœur, à vous, Vénérables Frères, à votre clergé et à vos ouailles, la

Bénédiction Apostolique.

Donné à Rome, près

Saint-Pierre, le 12 novembre 1923, de Notre Pontificat la deuxième année.

PIE XI, PAPE.

Source : Actes

de S. S. Pie XI, t. I, p. 291, La Bonne Presse, 1927.

Notes de bas de page

Ep., l. II, ep. 74, dans

Migne, P. L., t. 148, col. 425[↩]

Office de St Josaphat[↩]

Secrète de la Messe de la

Fête-Dieu[↩]

Ікона

Священномученика Йосафата Кунцевича, архієпископа Полоцького (УГКЦ) з експозиції

музею у Збаразькому замку. XIX ст. Полотно, олія, позолота.

Icon

of St. Martyr Josaphat Kuntsevych, Archbishop of Polotsk (UGCC) from the

exposition of museum in Zbarazh Castle. XIX Ct. Canvas, oil, gilding.

Chers Frères et Soeurs,

1. Le jour approche où

l'Église grecque-catholique d'Ukraine célébrera le quatrième centenaire de

l'union entre les évêques de la Province métropolitaine de la Rus' de Kiev et

le Siège apostolique. L'union fut établie lors de la rencontre des

représentants de la Province métropolitaine de Kiev avec le Pape, qui eut lieu

le 23 décembre 1595, et elle fut proclamée solennellement à Brest-Litovsk, sur

le fleuve Bug, le 16 octobre 1596. Par la constitution apostolique Magnus

Dominus et laudabile nimis(1), le Pape Clément VIII en fit l'annonce à l'Église

entière et, par la lettre apostolique Benedictus sit Pastor(2), il s'adressa

aux évêques de la Province métropolitaine pour les informer de l'union qui

venait de se faire.

Les Papes suivirent avec

sollicitude et affection la vie, souvent dramatique et douloureuse, de cette

Église. Je voudrais rappeler ici d'une façon particulière l'encyclique

Orientales omnes de Pie XII qui, en 1945, écrivit des paroles inoubliables pour

rappeler le trois cent cinquantième anniversaire du rétablissement de la pleine

communion avec le Siège de Rome(3).

L'Union de Brest ouvrit

une nouvelle page de l'histoire de cette Église(4). Aujourd'hui, celle-ci veut

chanter dans l'allégresse l'hymne d'action de grâce et de louange à Celui qui,

encore une fois, l'a ramenée de la mort à la vie, et elle veut reprendre sa

marche avec un élan renouvelé sur la route tracée par le Concile Vatican II.

Aux fidèles de l'Église

grecque-catholique d'Ukraine s'unissent, dans l'action de grâce et la

supplication, les Églises grecques-catholiques de la diaspora qui se réclament

de l'Union de Brest, ainsi que les autres Églises orientales catholiques et

l'Église tout entière.

Je veux m'unir aux

catholiques de tradition byzantine de ces terres, moi aussi, Évêque de Rome,

qui pendant de si nombreuses années, au temps de mon ministère pastoral en

Pologne, ai senti la proximité physique, et non seulement spirituelle, avec

cette Église qui était alors si durement éprouvée, moi qui, après mon élection

au Siège de Pierre, ai ressenti, à la suite de mes prédécesseurs, le pressant

devoir d'élever la voix pour défendre son droit à l'existence et à la libre

profession de la foi, alors qu'on les lui refusait toutes les deux. J'ai maintenant

le privilège de célébrer avec émotion, en même temps qu'elle, les jours de la

liberté retrouvée.

À la recherche de l'unité

2. Il faut replacer les

célébrations de l'Union de Brest dans le contexte du Millénaire du Baptême de

la Rus'. Il y a sept ans, en 1988, cet événement fut célébré très

solennellement. À cette occasion, j'ai publié deux documents : la lettre

apostolique Euntes in mundum, du 25 janvier 1988(5), pour l'Église entière, et

le message Magnum baptismi donum, du 14 février de la même année(6), adressé

aux catholiques ukrainiens. Il s'agissait en effet de célébrer un moment

fondamental pour l'identité chrétienne et culturelle de ces peuples, moment qui

revêtait une valeur tout à fait particulière du fait que les Églises de

tradition byzantine et l'Église de Rome vivaient encore en pleine communion.

Depuis qu'a eu lieu la

division qui blessa l'unité entre l'Occident et l'Orient byzantin, des efforts

fréquents et intenses furent faits pour rétablir la pleine communion. Je veux

rappeler deux événements particulièrement significatifs : le Concile de Lyon en

1274, et surtout le Concile de Florence en 1439, où furent signés des

protocoles d'union avec les Églises orientales. Malheureusement, diverses

causes empêchèrent les possibilités contenues dans ces accords de porter les

fruits attendus.

En rétablissant la

communion avec Rome, les évêques de la Province métropolitaine de Kiev se

référèrent explicitement aux décisions du Concile de Florence, donc à un

Concile auquel avaient participé directement, entre autres, les représentants

du Patriarcat de Constantinople.

Une figure resplendit

dans ce contexte : celle du métropolite Isidore de Kiev, fidèle interprète et

défenseur des décisions de ce Concile, qui dut subir l'exil en raison de ses

convictions.

Les évêques qui

encouragèrent l'union, ainsi que leur Église, gardaient une conscience très

vive des liens étroits qui les unissaient depuis l'origine à leurs frères

orthodoxes, en plus d'un sens profond de l'identité orientale de leur Province

métropolitaine, qu'il fallait sauvegarder même après l'union. Dans l'histoire

de l'Église catholique, il est d'une grande importance que ce juste désir ait

été respecté et que l'acte d'union n'ait pas signifié le passage à la tradition

latine, comme certains pensaient que cela devait se réaliser : leur Église se

vit reconnaître le droit d'être gouvernée par une hiérarchie propre selon une

discipline spécifique, et de maintenir son patrimoine oriental liturgique et

spirituel.

Entre persécution et

développement

3. Après l'union,

l'Église grecque-catholique d'Ukraine vécut une période de développement des

structures ecclésiastiques, avec des retombées bénéfiques sur la vie

religieuse, sur la formation du clergé et pour l'engagement spirituel des

fidèles. Faisant preuve d'une notable clairvoyance, on attribua une grande

place à l'éducation. Grâce à la précieuse contribution de l'Ordre basilien et

d'autres Congrégations religieuses, l'étude des disciplines sacrées et de la

culture propre connut une admirable croissance. Au cours du siècle actuel, dans

ce domaine comme aussi par le témoignage de la souffrance subie pour le Christ,

le métropolite André Szeptyckyj fut une figure d'un prestige extraordinaire : à

la formation personnelle et à la finesse spirituelle, il sut allier des dons

excellents d'organisateur, fondant des écoles et des académies, soutenant les

études théologiques et les sciences humaines, la presse, l'art sacré, la

sauvegarde des mémoires.

Et pourtant, une telle

vitalité ecclésiale fut toujours traversée par le drame de l'incompréhension et

de l'opposition. L'illustre archevêque de Polock et Vitebsk, Josaphat Kuncevyc,

en fut victime, lui dont le martyre fut auréolé de la couronne impérissable de

la gloire éternelle. Son corps repose maintenant dans la basilique vaticane, où

il reçoit continuellement l'hommage ému et reconnaissant de tous les

catholiques.

Les difficultés et les

souffrances se répétèrent sans répit. Pie XII les a rappelées dans l'encyclique

Orientales omnes, dans laquelle, après s'être arrêté sur les persécutions

précédentes, il présageait déjà cette autre persécution, dramatique, du régime

athée(7).

Parmi les témoins

héroïques non seulement des droits de la foi, mais aussi de la conscience

humaine, qui se distinguèrent au cours de ces années difficiles, se détache la

figure du métropolite Josyf Slipyj : son courage pour supporter l'exil et la

prison pendant dix-huit ans et sa confiance inébranlable en la résurrection de

son Église font de lui l'un des exemples les plus marquants de confesseur de la

foi de notre temps. Il ne faut pas non plus oublier ses nombreux compagnons de

souffrance, en particulier les évêques Grégoire Chomyszyn et Josaphat

Kocylowskyj.

Ces événements orageux

secouèrent l'Église de leur patrie. Mais la Providence divine avait déjà décidé

depuis longtemps que de nombreux fils de cette Église pourraient trouver une

issue pour eux et pour leur peuple : à partir du XIXe siècle, en effet, ils

commencèrent à se répandre en grand nombre au-delà des océans, par vagues

migratoires qui les conduisirent surtout au Canada, aux États-Unis d'Amérique,

au Brésil, en Argentine et en Australie. Le Saint-Siège se voulut proche d'eux,

les assistant et instituant pour eux des structures pastorales dans leurs

nouveaux lieux de résidence, jusqu'à constituer des Éparchies proprement dites.

Au temps de l'épreuve, pendant la persécution athée dans leur terre d'origine,

la voix de ces croyants put ainsi s'élever, en pleine liberté, avec force et

courage. Ils revendiquèrent avec force dans l'opinion internationale le droit à

la liberté religieuse pour leurs frères persécutés, donnant ainsi plus de

vigueur à l'appel que lança le Concile Vatican II en faveur de la liberté

religieuse(8) et à l'action exercée en ce sens par le Saint-Siège.

4. Toute la Communauté

catholique se souvient avec émotion des victimes de tant de souffrances : les

martyrs et les confesseurs de la foi de l'Église en Ukraine nous offrent une

admirable leçon de fidélité au prix de la vie. Et nous, témoins privilégiés de

leur sacrifice, nous sommes bien conscients qu'ils ont contribué à maintenir

dans la dignité un monde qui semblait emporté par la barbarie. Ils ont connu la

vérité, et la vérité les a rendus libres. Les chrétiens d'Europe et du monde,

s'inclinant en prière au seuil des camps de concentration et des prisons,

doivent leur être reconnaissants pour la lumière qu'ils ont donnée : c'était la

lumière du Christ, qu'ils ont fait resplendir dans les ténèbres. Aux yeux du

monde, les ténèbres ont longtemps paru l'emporter, mais elles n'ont pu éteindre

cette lumière, car c'était la lumière de Dieu et la lumière de l'homme offensé

mais qui ne pliait pas.

Cet héritage de

souffrance et de gloire se trouve aujourd'hui à un tournant historique : une

fois tombées les chaînes de la prison, l'Église grecque-catholique en Ukraine a

recommencé à respirer l'air de la liberté et à retrouver pleinement son rôle

actif dans l'Église et dans l'histoire. Cette tâche, délicate et

providentielle, requiert aujourd'hui une réflexion particulière pour qu'elle soit

accomplie avec sagesse et clairvoyance.

Dans le sillage du

Concile Vatican II

5. La célébration de

l'Union de Brest doit être vécue et interprétée à la lumière des enseignements

du Concile Vatican II. C'est là peut-être l'aspect le plus important pour bien

comprendre la portée de cet anniversaire.

On sait que le Concile

Vatican II a longuement réfléchi surtout sur le mystère de l'Église, et

qu'ainsi l'un des documents les plus importants qu'il a élaborés est la

constitution Lumen gentium. C'est précisément en raison de cette étude

approfondie que le Concile revêt une importance particulière sur le plan

oecuménique. On en a une confirmation dans le décret Unitatis redintegratio,

qui élabore un programme fort éclairé sur l'action à mener en vue de l'unité

des chrétiens. Il m'a semblé utile de revenir sur ce programme, trente ans

après la conclusion du Concile, en publiant, le 25 mai de cette année,

l'encyclique Ut unum sint(9). Elle indique les progrès oecuméniques qui ont été

réalisés après le Concile Vatican II et en même temps, dans la perspective du

troisième millénaire de l'ère chrétienne, elle cherche à ouvrir de nouvelles

perspectives pour l'avenir.

En plaçant les

célébrations de l'année prochaine dans le contexte de la réflexion sur

l'Église, promue par le Concile, je tiens surtout à inviter à approfondir le

rôle propre que l'Église grecque-catholique d'Ukraine est appelée à exercer

aujourd'hui dans le mouvement oecuménique.

6. Certains voient dans

l'existence des Églises orientales catholiques une difficulté pour la marche de

l'oecuménisme. Le Concile Vatican II n'a pas manqué d'aborder ce problème, tout

en donnant des éléments de solution, tant dans le décret Unitatis redintegratio

sur l'oecuménisme que dans le décret Orientalium Ecclesiarum, qui leur est

directement consacré. Les deux documents se placent dans la perspective du

dialogue oecuménique avec les Églises orientales qui ne sont pas en pleine

communion avec le Siège de Rome, de manière que soit mise en relief la richesse

que les autres Églises ont en commun avec l'Église catholique et que soit

fondée sur cette richesse partagée la recherche d'une communion toujours plus

pleine et plus profonde. En effet, «l'oecuménisme vise précisément à faire

progresser la communion partielle existant entre les chrétiens, pour arriver à

la pleine communion dans la vérité et la charité»(10).

Pour promouvoir le

dialogue avec l'Orthodoxie byzantine, il a été constitué après le Concile

Vatican II une commission mixte spéciale, qui a intégré aussi parmi ses membres

des représentants des Églises orientales catholiques.

Par divers documents, on

a cherché à intensifier les efforts pour qu'il y ait une meilleure

compréhension entre les Églises orthodoxes et les Églises orientales

catholiques, non sans résultats positifs. Dans la lettre apostolique Orientale

lumen(11) et dans l'encyclique Ut unum sint(12), j'ai déjà traité des éléments

de sanctification et de vérité(13) communs à l'Orient et à l'Occident

chrétiens, et de la méthode qu'il convient de suivre dans la recherche de la

pleine communion entre l'Église catholique et les Églises orthodoxes à la

lumière de l'approfondissement de l'ecclésiologie accompli par le Concile

Vatican II : «Nous savons aujourd'hui que l'unité ne peut être réalisée par

l'amour de Dieu que si les Églises le veulent ensemble, dans le plein respect

des traditions individuelles et de leur nécessaire autonomie. Nous savons que

cela ne peut se réaliser qu'à partir de l'amour d'Églises qui se sentent

appelées à manifester toujours plus l'unique Église du Christ, née d'un seul

baptême et d'une seule Eucharistie, et qui veulent être soeurs»(14).

L'approfondissement de la connaissance de la doctrine sur l'Église, réalisé par

le Concile et l'après-Concile, a tracé une voie que l'on peut appeler nouvelle

pour la marche de l'unité : c'est la voie du dialogue de la vérité nourri et

soutenu par le dialogue de la charité (cf. Ep 4, 15).

7. La sortie de la

clandestinité a entraîné un changement radical dans la situation de l'Église

grecque-catholique d'Ukraine : elle s'est retrouvée devant les graves problèmes

de la reconstruction des structures dont elle avait été totalement privée et,

d'une manière plus générale, elle a dû s'employer à se redécouvrir pleinement

elle-même, non seulement en son for intérieur mais aussi par rapport aux autres

Églises.

Grâce soit rendue au

Seigneur, qui lui a accordé de célébrer ce jubilé en situation de liberté

religieuse reconquise ! Grâce lui soit rendue également pour la croissance du

dialogue de la charité, par lequel des pas significatifs ont été accomplis dans

la marche vers la réconciliation souhaitée avec les Églises orthodoxes !

Les migrations et les

déportations multiples ont redessiné la géographie religieuse de ces terres;

les nombreuses années d'athéisme d'État ont profondément marqué les

consciences; le clergé n'arrive pas encore à répondre aux immenses besoins de

la reconstruction religieuse et morale : voilà quelques-uns des défis les plus

dramatiques auxquels toutes les Églises se trouvent confrontées.

Face à ces difficultés,

il faut un témoignage commun de la charité, afin qu'il n'y ait pas d'obstacle à

la prédication de l'Évangile. Comme je l'ai dit dans la lettre apostolique

Orientale lumen, «aujourd'hui, nous pouvons coopérer pour l'annonce du Royaume

ou nous rendre coupables de nouvelles divisions»(15). Puisse le Seigneur guider

nos pas sur le chemin de la paix !

Le sang des martyrs

8. Dans la liberté

retrouvée, nous ne pouvons oublier la persécution et le martyre que les Églises

de cette région, catholiques et orthodoxes, ont subis dans leur chair. C'est là

une dimension importante pour l'Église de tous les temps, comme je l'ai rappelé

dans la lettre apostolique Tertio millennio adveniente(16). C'est un héritage

particulièrement significatif pour les Églises d'Europe, qui en restent

profondément marquées; il faudra y réfléchir à la lumière de la Parole de Dieu.

Nous avons donc le

devoir, qui est partie intégrante de notre mémoire religieuse, de rappeler la

signification du martyre, afin de désigner à la vénération de tous les figures

concrètes de ces témoins de la foi, sachant qu'aujourd'hui encore le mot de

Tertullien conserve toute sa valeur : «Sanguis martyrum, semen

Christianorum»(17). Nous autres, chrétiens, avons déjà un martyrologe commun

dans lequel Dieu maintient et réalise entre les baptisés la communion dans

l'exigence suprême de la foi, manifestée par le sacrifice de la vie. La

communion réelle, quoique imparfaite, qui existe déjà entre catholiques et

orthodoxes dans leur vie ecclésiale, atteint sa perfection en ce que «nous

considérons tous comme le sommet de la vie de grâce, la martyria jusqu'à la

mort, la communion la plus vraie avec le Christ qui répand son sang et qui,

dans ce sacrifice, rend proches ceux qui jadis étaient loin (cf. Ep 2, 13)»(18).

Le souvenir des martyrs

ne peut être effacé de la mémoire de l'Église et de l'humanité : qu'ils soient

victimes d'idéologies de l'Orient ou de l'Occident, tous se retrouvent unis par

la violence qui, en haine de la foi, est faite à la dignité de la personne

humaine, créée par Dieu «à son image, à sa ressemblance».

L'Église du Christ est

une

9. «Je crois en l'Église,

une, sainte, catholique et apostolique». Cette profession de foi contenue dans

le symbole de Nicée-Constantinople est commune aux chrétiens catholiques et

orthodoxes; cela montre à l'évidence que non seulement ils croient en l'unité

de l'Église, mais qu'ils vivent et veulent vivre dans l'Église une et

indivisible, telle qu'elle a été fondée par Jésus Christ. Les différences qui

sont nées et se sont développées entre le christianisme d'Orient et celui

d'Occident au cours de l'histoire proviennent en grande partie de cultures et

de traditions diverses. En ce sens, «la diversité légitime ne s'oppose pas du

tout à l'unité de l'Église, elle en accroît même le prestige et contribue

largement à l'achèvement de sa mission»(19).

Le Pape Jean XXIII aimait

dire que «ce qui nous unit est beaucoup plus fort que ce qui nous divise». Je

suis certain que cet état d'esprit peut aider grandement toutes les Églises. Plus

de trente ans ont passé depuis que le Pape a prononcé ces paroles. Bien des

indices nous poussent à penser que pendant ce temps les chrétiens ont progressé

sur ce chemin. On en a des signes éloquents dans les rencontres fraternelles

entre le Pape Paul VI et le Patriarche oecuménique Athénagoras Ier et celles

que j'ai eues moi-même avec les Patriarches oecuméniques Dimitrios et, tout

récemment, Bartholomaios, de même qu'avec d'autres vénérables Patriarches des

Églises d'Orient. Tout cela, avec les nombreuses initiatives de rencontres et

de dialogue qui sont encouragées partout dans l'Église, nous invite à

l'espérance : l'Esprit Saint, l'Esprit d'unité, ne cesse d'agir parmi les

chrétiens encore séparés entre eux.

Et pourtant, la faiblesse

humaine et le péché continuent à opposer une résistance à l'Esprit d'unité. On

a même parfois l'impression que certaines forces sont prêtes à tout pour

freiner, voir anéantir, le processus d'union entre les chrétiens. Mais nous ne

pouvons pas renoncer; nous devons trouver chaque jour le courage et la force,

qui sont à la fois un don de l'Esprit et le fruit de l'effort humain, de

poursuivre la route entreprise.

10. En repensant à

l'Union de Brest, nous nous demandons quel est aujourd'hui le sens de cet

événement. Il s'est agi d'une union qui concernait seulement une aire

géographique précise; toutefois, sa portée est grande pour la question

oecuménique dans son ensemble. Les Églises orientales catholiques peuvent

apporter une contribution très importante à l'oecuménisme. Le décret

conciliaire Orientalium Ecclesiarum le rappelle : «Aux Église orientales qui

sont en communion avec le Siège apostolique romain revient la charge

particulière de faire progresser l'unité de tous les chrétiens, surtout des

chrétiens orientaux, selon les principes du décret de ce saint Concile Unitatis

redintegratio, par la prière avant tout, par l'exemple de leur vie, par leur

religieuse fidélité aux antiques traditions orientales, par une meilleure

connaissance mutuelle, par la collaboration et l'estime fraternelle des choses

et des hommes»(20). Il en résulte pour elles un engagement à vivre intensément

ce qui est indiqué ici. Il leur est demandé une profession sincère d'humilité

et de gratitude envers l'Esprit Saint, qui guide l'Église vers la fin qui lui a

été assignée par le Rédempteur du monde.

Un temps de prière

11. L'élément fondamental

qui devra caractériser la célébration de ce jubilé sera donc la prière.

Celle-ci est avant tout une action de grâce pour ce qu'a permis de réaliser, au

cours des siècles, l'engagement en faveur de l'unité de l'Église, et en

particulier pour l'impulsion qu'a donné à cet engagement le Concile Vatican II.

C'est une prière d'action

de grâce au Seigneur qui guide la marche de l'histoire, pour le climat de

liberté religieuse retrouvée dans lequel se célèbre ce jubilé. C'est aussi une

supplication à l'Esprit Paraclet pour qu'il fasse croître tout ce qui favorise

l'unité et qu'il donne courage et force à ceux qui s'engagent, selon les

orientations du décret conciliaire Unitatis redintegratio, dans cette oeuvre

bénie de Dieu. C'est une supplication pour obtenir l'amour fraternel, le pardon

des offenses et des injustices subies au cours de l'histoire. C'est une

supplication pour que la puissance du Dieu vivant tire du bien même du mal si

cruel et multiforme causé par la méchanceté des hommes. La prière est aussi

espérance pour l'avenir de la marche oecuménique : la puissance de Dieu est

plus grande que toutes les faiblesses humaines anciennes et nouvelles. Si ce

jubilé de l'Église grecque-catholique d'Ukraine, au seuil du troisième

millénaire, marque quelques pas en avant vers la pleine unité des chrétiens, ce

sera avant tout l'oeuvre de l'Esprit Saint.

Un temps de réflexion

12. Les célébrations

jubilaires seront en outre un temps de réflexion. L'Église grecque-catholique

d'Ukraine s'interrogera avant tout sur ce qu'a signifié pour elle la pleine

communion avec le Siège apostolique et sur ce qu'elle devra signifier à

l'avenir. Elle rendra gloire à Dieu, dans une attitude d'humble gratitude, pour

son héroïque fidélité au Successeur de Pierre, et, sous l'action de l'Esprit

Saint, elle comprendra que cette fidélité même la place aujourd'hui sur la voie

de l'engagement pour l'unité de toutes les Églises. Cette fidélité lui a valu des

souffrances et le martyre dans le passé : c'est là un sacrifice offert à Dieu

pour implorer l'union souhaitée.

La fidélité aux antiques

traditions orientales est l'un des moyens dont disposent les Églises orientales

catholiques pour promouvoir l'unité des chrétiens(21). Le décret conciliaire

Unitatis redintegratio est très explicite quand il déclare : «Que tous sachent

que connaître, vénérer, conserver, développer, le patrimoine liturgique et

spirituel si riche des Orientaux est de la plus haute importance pour conserver

fidèlement la plénitude de la tradition chrétienne et pour réaliser la

réconciliation des chrétiens d'Orient et d'Occident»(22).

Une mémoire confiée à

Marie

13. Ne cessons pas de

confier l'aspiration à la pleine unité des chrétiens à la Mère du Christ,

toujours présente dans l'action du Seigneur et de son Église. Le chapitre VIII

de la constitution dogmatique Lumen gentium la désigne comme Celle qui nous

précède dans le pèlerinage de la foi sur terre, affectueusement présente à

l'Église qui, au terme du deuxième millénaire, s'emploie à rétablir entre tous

ceux qui croient au Christ l'unité que le Seigneur veut pour eux. Elle est la

Mère de l'unité, parce qu'elle est la Mère de l'unique Christ. Si, par l'Esprit

Saint, elle a mis au monde le Fils de Dieu, qui a reçu d'elle son corps humain,

Marie désire ardemment l'unité visible de tous les croyants, qui forment le

Corps mystique du Christ. La dévotion envers Marie, qui unit si étroitement

l'Orient et l'Occident, oeuvrera, soyons-en certains, en faveur de l'unité.

La Vierge sainte, déjà

présente partout au milieu de nous, dans de si nombreux édifices sacrés comme

dans la vie de foi de tant de familles, parle continuellement d'unité, pour

laquelle elle intercède sans cesse. Aujourd'hui, en commémorant l'Union de

Brest, nous nous rappelons les merveilleux trésors de vénération qu'a su

réserver à la Mère de Dieu le peuple chrétien d'Ukraine; de cette admiration

pour l'histoire, pour la spiritualité, pour la prière de ces peuples, nous ne

pouvons pas ne pas tirer les conséquences pour l'unité qui sont si étroitement

liées à ces trésors.

Marie, qui a inspiré dans

l'épreuve pères et mères, jeunes, malades, personnes âgées, Marie, colonne de

feu capable de guider tant de martyrs de la foi, est certainement à l'oeuvre

pour préparer l'union désirée de tous les chrétiens; en vue de cette union,

l'Église grecque-catholique d'Ukraine a sans aucun doute un rôle à jouer.

L'Église exprime ses

remerciements à Marie et la prie de nous faire participer à sa sollicitude pour

l'unité; abandonnons-nous à elle avec une confiance filiale, afin de nous

retrouver avec elle là où Dieu sera tout en tous.

À vous tous, Frères et

Soeurs très chers, va ma Bénédiction apostolique.

Du Vatican, le 12

novembre 1995, mémoire de saint Josaphat, en la dix-huitième année de mon

pontificat.

(1) Cf. Bullarium Romanum

V/2 (1594-1602), pp. 87-92.

(2) Cf. A. WELYKYJ,

Documenta Pontificum Romanorum Historiam Ucrainæ illustrantia, t. I, pp.

257-259.

(3) Cf. AAS 38 (1946),

pp. 33-63.

(4) Cf. JEAN-PAUL II,

Lettre au Cardinal Myroslav I. Lubachivsky, Archevêque majeur de Lviv des

Ukrainiens (25 mars 1995), n. 3: L'Osservatore Romano, 5 mai 1995, p. 6.

(5) Cf. AAS 80 (1988),

pp. 935-956.

(6) Cf. ibid., pp.

988-997.

(7) Cf. AAS 38 (1946),

pp. 54-57. Ces craintes devaient trouver une confirmation angoissante quelques

années plus tard, comme le notait précisément le même Pape dans l'encyclique

Orientales Ecclesias (15 décembre 1952) : AAS 45 (1953), pp. 7-10.

(8) Cf. Déclaration sur

la liberté religieuse Dignitatis humanæ.

(9) Cf. L'Osservatore

Romano 31 mai 1995, pp. 1-8.

(10) Ibid., l.c., p. 2.

(11) Cf. nn. 18-19:

L'Osservatore Romano 2-3 mai 1995, p. 4.

(12) Cf. nn. 12-14:

L'Osservatore Romano 31 mai 1995, p. 2.

(13) Cf. CONC. OECUM.

VAT. II, Décret sur l'oecuménisme Unitatis redintegratio, n. 3.

(14) JEAN-PAUL II, Lettre

ap. Orientale lumen (2 mai 1995), n. 20: L'Osservatore Romano 2-3 mai 1995, p.

4.

(15) N. 19: L'Osservatore

Romano 2-3 mai 1995, p. 4.

(16) Cf. AAS 87 (1995),

pp. 29-30; Encycl. Ut unum sint, n. 84: L'Osservatore Romano 31 mai 1995, p. 7.

(17) Apol., 50, 13: CCL

I, 171.

(18) JEAN-PAUL II,

Encycl. Ut unum sint, n. 84: L'Osservatore Romano 31 mai 1995, p. 7.

(19) Ibid., n. 50: l.c.,

p. 5.

(20) N. 24.

(21) Cf. ibid.

(22) N. 15.

Copyright © Libreria

Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Ritratto

del santo it:Josaphat Kunzewitsch, di it:Volodymyr-Volyns'kyj (clip)

Chers pèlerins venus

d’Ukraine,

J’ai accueilli très

volontiers l’invitation de Sa Béatitude Sviatoslav Shevchuk, archevêque majeur

de Kiev-Haly?, et du synode de l’Église grecque-catholique ukrainienne, à

m’unir à vous au cours de ce pèlerinage sur la tombe de saint Josaphat, évêque

et martyr, à l’occasion du cinquantième anniversaire de la translation de ses

reliques dans cette basilique vaticane. J’accueille avec joie également la

délégation des Byzantins de Biélorussie.

Le 22 novembre 1963, le

Pape Paul

VI fit placer le corps de saint Josaphat sous l’autel consacré à saint

Basile le grand, près de la tombe de saint Pierre. Le saint martyr ukrainien,

en effet, avait choisi d’embrasser la vie monastique selon la Règle basilienne.

Et il le fit jusqu’au bout, en s’engageant également pour la réforme de son

Ordre d’appartenance, réforme qui conduisit à la naissance de l’Ordre basilien

de saint Josaphat. Dans le même temps, d’abord en tant que simple fidèle, puis

en tant que moine et, enfin, en tant qu’évêque, il s’engagea de toutes ses

forces pour l’union de l’Église sous la direction de Pierre, Prince des

apôtres.

Chers frères et sœurs, la

mémoire de ce saint martyr nous parle de la communion des saints, de la

communion de vie entre tous ceux qui appartiennent au Christ. C’est une réalité

qui nous donne un avant-goût de la vie éternelle, car un aspect important de la

vie éternelle consiste dans la joyeuse fraternité de tous les saints. « Chaque

élu (...) aimera chacun des bienheureux comme lui-même — enseignait saint

Thomas d’Aquin — ; c’est pourquoi il se réjouira du bien des autres comme de

son bien propre. Aussi l’allégresse et la joie de tous les élus

s’augmenteront-elles de la joie et de l’allégresse de chacun d’entre eux » (Commentaire

du Credo).

Si telle est la communion

de l’Église, chaque aspect de notre vie chrétienne peut être animé du désir de

construire ensemble, de collaborer, d’apprendre les uns des autres, de

témoigner de la foi ensemble. Jésus Christ, le Seigneur Ressuscité, nous

accompagne sur ce chemin et est le cœur de ce chemin. Ce désir de communion

nous pousse à chercher à comprendre l’autre, à le respecter, et également à

l’accueillir et à offrir la correction fraternelle.

Chers frères et sœurs, la

meilleure façon de célébrer saint Josaphat est de nous aimer entre nous et

d’aimer et de servir l’Église. Nous sommes soutenus en cela également par le

témoignage courageux de nombreux martyrs des temps récents, qui constituent une

grande richesse et un grand réconfort pour votre Église.

Je souhaite que la

communion profonde que vous désirez approfondir chaque jour au sein de l’Église

catholique, vous aide à construire des ponts de fraternité également avec les

autres Églises et communautés ecclésiales en terre ukrainienne et ailleurs, là

où vos communautés sont présentes. À travers l’intercession de la Bienheureuse

Vierge Marie et de saint Josaphat, que le Seigneur vous accompagne toujours et

vous bénisse !

Et s’il vous plaît,

n’oubliez pas de prier pour moi. Merci !

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Altar

of Saint Basil, in Basilica of S. Peter, at Vatican, 1745. The subject of the

altarpiece is St. Basil Celebrating Mass in the presence of the Arian Emperor

Valens. The painting that served as the cartoon for this altarpiece was

commissioned from Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749) , and

the mosaic was made from 1748 to 1751 by Guglielmo Paleat, Giuseppe Ottaviani,

Enroco Enuo, and Nicolo Onofri. Under the altar, tomb of Saint Josaphat

Kuntsewycz - https://stpetersbasilica.info/Altars/StBasil/StBasil.htm#:~:text=On%20the%20other%20side%20of,Emperor%20Valentius%20with%20his%20retinue.

Ukraine: prière du Pape

pour la paix, mémoire de saint Josaphat

À l’issue de la prière de

l'Angélus, François a salué les pèlerins ukrainiens présents à Rome pour la

célébration, à Saint-Pierre, de la Divine Liturgie présidée par l'Archevêque

Majeur de Kiev, pour les 400 ans du martyre de saint Josaphat. À cette

occasion, le supérieur de l'Ordre basilien fondé par le saint revient sur les

enseignements du saint dans un contexte de guerre: «Son témoignage nous exhorte

à avoir le courage de dénoncer le péché et de prier pour la conversion de

l'ennemi».

Svitlana Dukhovych - Cité

du Vatican

«Je prie avec vous pour

la paix dans votre pays martyrisé», a lancé le Pape ce dimanche depuis les

fenêtres des appartements pontificaux, appelant les fidèles à ne pas oublier

l'Ukraine.

Alors que l'Église célèbre

le saint ukrainien Josaphat Kuncewycz, le Pape a pris le temps de saluer les

pèlerins ukrainiens et les moines basiliens venus de divers pays pour célébrer

le quatrième centenaire du martyre de l'évêque de Polotzk, qui a vécut entre le

XVIe et le XVIIe siècle, exhortant son troupeau à l'unité catholique avec un

zèle constant tout en cultivant le rite byzantino-slave avec dévotion.

Une Divine Liturgie 400

ans après son martyre

Né à Wolodymyr en

Volynie, Josaphat Kuncewycz est mort le 12 novembre 1623 et a été canonisé

en 1877 en tant que premier représentant d'une Église orientale en communion

avec Rome. Sa dépouille repose sous l'autel de saint Basile le Grand dans la

basilique Saint-Pierre, où une Divine Liturgie a été présidée ce dimanche, à

l'occasion du 400e anniversaire de son martyre, par le chef de l'Église

gréco-catholique ukrainienne, l'archevêque majeur Sviatoslav Chevchouk, et

concélébrée par l'archevêque métropolitain de Vilnius, Gintaras Grušas,

président du Conseil des Conférences épiscopales d'Europe (CCEE).

Dans une interview

accordée à Radio Vatican-Vatican News, le père Robert Lisseiko, OSBM,

supérieur général de l'Ordre Basilien de Saint Josaphat, explique comment

leur fondateur a mis en pratique le concept d'unité, pour lequel il a donné sa

vie. Il revient également sur le rôle joué par son Ordre dans la construction

du tissu social et religieux de la société ukrainienne, et sur la manière dont

les enseignements de saint Josaphat peuvent aider les fidèles ukrainiens à

faire face à la tragédie de la guerre aujourd'hui.

Dimanche, en la basilique

Saint-Pierre, une divine liturgie est consacrée au 400e anniversaire du martyre

de saint Josaphat Kuncewycz, connu sous le nom de "martyr de

l'unité". Pouvez-vous nous expliquer pourquoi on le désigne ainsi?

Saint Josaphat est un

saint de l'époque où la métropole de Kiev, après l'Union de Brest (1595-1596),

est passée de la juridiction du patriarcat de Constantinople à celle du Pape,

retrouvant ainsi l'unité avec le Pontife romain de l'Église chrétienne

primitive. En tant que moine basile, prêtre puis évêque, saint Josaphat a

toujours cherché à amener les personnes qui lui étaient confiées à l'unité -

d'abord avec le Christ. Sa figure a parfois été perçue comme celle d'un homme

cherchant à convertir les orthodoxes à la foi catholique, mais si nous

examinons sa vie, nous constatons que son attitude était tout à fait

différente. Tout d'abord, en tant que moine entré au monastère de la

Sainte-Trinité à Vilnius, il a recherché l'unité personnelle avec le Christ par

la prière personnelle et liturgique et une profonde ascèse. Josaphat est entré

dans un monastère en ruines, matérielles et spirituelles, où il n'y avait

presque plus personne et où la vie monastique s'était dégradée. Au contraire,

par l'exemple qu'il a donné aux autres, il a réussi à attirer de nombreux

jeunes à la vie monastique en quelques années. Il a ensuite ramené de

nombreuses âmes humaines à l'unité avec le Christ, parce qu'il a été un grand

confesseur qui a prêché la parole du Christ, l'Évangile, en appelant à la

conversion et à la pénitence. C'est surtout pour cela que Josaphat est un

apôtre et un martyr de l'unité, parce que son travail a été vu d'un mauvais œil

par ceux dont la conscience avait probablement été touchée par sa parole. Ce

sont ceux qui ne voulaient pas entendre la parole de vérité de saint Josaphat ;

la colère a été la cause du martyre.

Quel rôle votre Ordre,

fondé par le saint, a-t-il joué dans la construction du tissu religieux et

social de l'Ukraine au cours de ces 400 ans?

Depuis le début du XXe

siècle, notre ordre était le seul ordre monastique de ce que nous appelons

aujourd'hui l'Église gréco-catholique ukrainienne. En tant qu'unique ordre

monastique renouvelé, fondé par saint Josaphat et le métropolite Josyf Veljamyn

Rutskyj, il a été à l'origine du développement de la métropole de Kiev en unité

avec le Pape. Au fil des ans, il s'est consacré non seulement à la prédication

de l'Évangile, mais aussi à l'éducation des gens: nous avions de nombreuses

écoles, des imprimeries (la plus célèbre étant celle de Pochaiv) où l'on

imprimait non seulement des livres ecclésiastiques et liturgiques, mais aussi

des livres populaires en langue vernaculaire. Cela a contribué à la croissance

de la société, car les personnes qui savaient lire pouvaient accéder aux

différentes sources de connaissances et devenaient intérieurement plus libres.

Alors que nous célébrons

le 400e anniversaire du martyre de saint Josaphat Kuncewycz, l'Ukraine traverse

l'une des périodes les plus difficiles de son histoire en raison de la guerre.

Quelles leçons pouvons-nous tirer de la vie de ce saint pour faire face à la

tragédie actuelle?

Je crois que dans le

contexte que nous vivons, la figure de saint Josaphat peut nous enseigner des

choses fondamentales, à savoir avoir le courage de dénoncer le péché et essayer

de grandir dans la vérité du Christ. Dans le contexte de la guerre, il y a deux

extrêmes: l'un consiste à dire que nous devons pardonner à nos ennemis et ne

pas défendre le peuple ukrainien, c'est ce que nous pouvons appeler un

"faux pacifisme" ; l'autre extrême consiste à se venger, parce que

notre ennemi est en train de détruire notre peuple. Au contraire, l'Évangile

nous enseigne autre chose: nous devons savoir pardonner à notre ennemi, non pas

en cherchant à l'anéantir, mais en travaillant à sa conversion. Le Christ nous

dit: "Priez pour vos ennemis, aimez vos ennemis", non pas dans le

sens de ne pas s'opposer à la violence qui vient de lui, mais dans le sens de

faire tout ce qui dépend de nous pour sa conversion, afin que l'ennemi devienne

un frère. C'est ce qu'a fait saint Josaphat en tant que prêtre, en tant

qu'évêque. Il a cherché à convertir à la vérité du Christ tous ceux qui étaient

éloignés de l'Évangile, et il a réussi à convertir les gens aussi bien pendant

sa vie qu'après son martyre: tant de ses adversaires sont devenus de vrais

chrétiens uniquement parce qu'ils ont vu l'exemple de saint Josaphat au service

du Christ dans la vérité.

Le saint a été tué par

une foule en colère qui n'acceptait pas son idée d'unité. Dans ce contexte, que

pouvez-vous dire de la tolérance entre les représentants de différentes

confessions et religions? Quel devrait être le bon critère pour la défense de

son identité, en l'occurrence religieuse ? À quoi faut-il veiller pour ne pas

dépasser la limite de l'injustice dans la défense de l'identité?

Je crois que la tolérance

dans le contexte évangélique est l'attitude qui consiste à respecter l'opinion

d'autrui qui est différente de la nôtre. Nous respectons le fait que chacun a

des limites et que pour arriver à la vérité, pour comprendre le message du

Christ, il faut du temps. Pour comprendre de nombreuses vérités prêchées par le

Christ, il faut du temps ; c'est une croissance continue, une méditation

continue de la Parole de Dieu. C'est cela la tolérance: tolérer les limites de

différentes personnes, même les nôtres, en sachant que nous voulons grandir. En

même temps, nous devons être vrais. Si, dans le dialogue interreligieux, nous

pouvons discuter de certains sujets, nous devons toujours le faire pour

rechercher la vérité de Dieu, pas seulement pour faire prévaloir une opinion,

mais pour trouver ce qui nous aide à vivre dans l'unité, dans l'amour mutuel

inclusif, capable aussi de renoncer à certaines choses. Car sans renoncement,

il n'est pas possible de parvenir à l'unité chrétienne et à l'amour entre

frères d'autres religions. C'est pourquoi être tolérant, c'est toujours

rechercher la vérité de Dieu qui nous a créés frères et sœurs.

Merci d'avoir lu cet

article. Si vous souhaitez rester informé, inscrivez-vous à la lettre

d’information en cliquant ici

Аляксандр

Тарасевіч. Св. (на той момант благаславёны) Язафат Кунцэвіч. Другая палова XVII

ст. Медзярыт - http://media.catholic.by/nv/n36/art6gallery.htm

Saint Josaphat

Jean Kuncewicz naquit à

Vladimir, en Volhynie. Placé par ses parents chez un riche négociant de Vilna,

il fuyait la dissipation et consacrait tout le temps dont il pouvait disposer à

l’étude et à la prière ; il ne fréquentait que les Catholiques unis au

Saint-Siège, et adressait à Dieu de ferventes prières pour la conversion des

protestants et des schismatiques.

Son patron, n’ayant pas

d’enfants, lui offrit de l’adopter et de le constituer héritier de sa fortune,

très considérable. Jean, qui n’aspirait qu’après les biens impérissables,

renonça an monde, prit l’habit de Saint-Basile, au couvent de la Trinité, à

Vilna (1604), et, selon une coutume encore en vigueur dans l’Église

gréco-russe, il changea son nom de Baptême en celui de Josaphat.

Il y avait, à l’entrée du

monastère, une petite cellule à peine digne de ce nom, qu’il choisit, parce

qu’elle était voisine de l’église. C’est dans ce dit paradis, comme il

l’appelait, qu’il s’ensevelit pour mener une vie d’anachorète. Promu au

sacerdoce, il exerça le saint ministère avec un zèle extraordinaire. À

l’église, chez lui, dans les rues, les places publiques, les hôtelleries,

partout, il expliquait la doctrine catholique, avec une clarté si vive, une

éloquence si émue, qu’il portait la persuasion dans l’âme des auditeurs : aussi

le clergé non uni défendait-il aux siens d’entendre la parole de saint

Josaphat.

Nommé évêque de Polotsk,

il composa, à l’usage de son clergé, des règles qui firent refleurir la

discipline ecclésiastique ; il rendit au culte son ancienne splendeur ; il

restaura la cathédrale de Polotsk et plusieurs autres édifices religieux. Il

fut le père des pauvres, pour lesquels il se dépouillait de tout. Une pauvre

veuve éplorée lui demanda du secours ; n’ayant plus la moindre monnaie, il

engagea son étole épiscopale pour lui venir en aide.

Irrités des innombrables

conversions qu’il opérait chaque jour, les schismatiques méditaient sa mort ;

le sachant, il offrit sa vie à Dieu : « Seigneur, dit-il, je sais que les

ennemis de l’union en veulent à ma vie ; je Vous l’offre de tout cœur : puisse

mon sang éteindre l’incendie causé par le schisme ! » Il fut assassiné pour la

cause de la Foi et de l’unité catholique, à Vitebst, le 12 novembre 1623,

Urbain VIII étant pape, Ferdinand II empereur romain germanique et Louis XIII

roi de France. Pie IX l’a canonisé le 29 juin1867.

On lit au Bréviaire

romain de ce jour :

« Josaphat Kuncewitz,

fils de parents nobles et Catholiques, naquit à Vladimir en Volhynie. Une

flèche partie du côté d’un crucifix le blessa au cœur, un jour que, tout

enfant, il écoutait sa mère lui parler de la Passion du Christ.

« À vingt ans, il fit

profession de vie monastique chez les Pères Basiliens. Il fut bientôt créé

archimandrite de Vilna, puis archevêque de Polotsk (1617) et se montra un

modèle de toutes les vertus. Ardent promoteur de l’union de l’Église Grecque

avec l’Église Latine il ramena au sein mater-nel de l’Église d’innombrables

hérétiques.

« Étant allé à Vitebsk

faire sa visite pastorale, il se présenta lui-même à des schismatiques qui le

cherchaient pour le tuer et avaient envahi la résidence archiépiscopale : « Mes

petits enfants, dit-il, si c’est à moi que vous en voulez, me voici ». Ils se

jettent alors sur lui, le rouent de coups, le percent de traits et le jettent

au fleuve, après l’avoir achevé à coups de hache.

« Le sang du Martyr fut

bienfaisant tout d’abord aux parricides eux-mêmes ; condamnés à mort, ils

abjurèrent presque tous le schisme et regrettèrent leur crime (1623).

« Le Pape Urbain VIII le

béatifia, et Pie IX canonisa ce défenseur de l’unité de l’Église (1867). C’est

le premier Saint oriental qui reçut cet honneur. »

Jozefat

Kuncewicz na ikonie w skansenie w Sanoku

Also known as

Giosafat Kuncewycz

Jehoshaphat Kuncewycz

John Kunsevich

Josaphat Kuntsevych

Josaphat of Polotsk

Jozofat Kuncewicz

formerly 14

November

Profile

His father was

a municipal counselor, and his mother known

for her piety. Raised in the Orthodox Ruthenian Church which, on 23

November 1595 in

the Union of Brest, united with the Church

of Rome. Trained as a merchant‘s apprentice at

Vilna, Lithuania,

he was offered partnership in the business,

and marriage to

his partner’s daughter; feeling the call to religious

life, he declined both. Monk in

the Ukrainian Order of Saint Basil (Basilians)

in Vilna at age 20 in 1604,

taking the name Brother Josaphat. Deacon. Ordained a Byzantine

rite priest in 1609.

Josaphat’s superior, Samuel, never accepted unity

with Rome,

and looked for a way to fight against Roman Catholicism and

the Uniats, the name given those who brought about and accepted the union

of the Churches. Learning of Samuel’s work, and fearing the physical and

spiritual damage it could cause, Josaphat brought it to the attention of his

superiors. The archbishop of Kiev, Ukraine,

removed Samuel from his post, replacing him with Josaphat.

He became a famous preacher.

Worked to bring unity among the faithful,

and bring strayed Christians back