Saint Henri II

Empereur germanique (+1024)

Il était le fils du duc de Bavière et, en raison de la mort prématurée de son parent Otton III, il fut couronné empereur germanique. Comme tel, il régna sur l'Allemagne, l'Autriche, la Suisse, les Pays-Bas et l'Italie du Nord. Il épousa sainte Cunégonde de Luxembourg que nous fêtons le 3 mars. Elle ne pouvait avoir d'enfants. Henri refusa de la répudier, fait inouï à cette époque et dans une société où la stérilité, surtout dans la noblesse, était une cause ordinaire de répudiation.

L'une de ses deux préoccupations majeures fut l'unité du Saint Empire romain germanique pour laquelle il dut beaucoup guerroyer. L'autre fut de réformer les habitudes de la Papauté, avec l'aide du roi de France, Robert le Pieux, en un siècle qui vit quatorze papes sur vingt-huit, être élus sous la seule influence des reines et des femmes.

Dans le même temps, il renforça l'influence de l'Eglise sur la société, fonda l'évêché de Bamberg et, oblat bénédictin, il soutint la réforme entreprise par les moines de Cluny.

Privé d'héritier, il institua le Christ comme son légataire de ses biens. A sa mort, sainte Cunégonde se retira à l'abbaye de Kaffungen qu'elle avait fondée.

Mémoire de saint Henri, empereur des Romains (romain-germanique), il garda,

rapporte-t-on, avec sa femme sainte Cunégonde, une continence totale, œuvra à

la réforme de l'Église et à sa propagation, conduisit le futur saint Étienne, roi des

Hongrois, à accueillir la foi du Christ avec presque tout son peuple, mourut à

Grona et fut inhumé, selon son désir, à Bamberg en Franconie, l'an 1024.

Martyrologe romain

Nous devons abandonner les biens temporels et mettre au second plan les avantages terrestres pour nous efforcer d'atteindre les demeures célestes qui sont éternelles. Car la gloire présente est fugitive et vaine si, tandis qu'on la possède, on omet de penser à l'éternité céleste.

Lettre de saint Henri à l'évêque de Bamberg

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1497/Saint-Henri-II.html

Saint Henri

Né en 973, couronné empereur d'Occident à Rome en 1014, Henri II mourut en 1024 et fut inhumé dans la cathédrale de Bamberg qu'il avait fondée. Avec son épouse Cunégonde, Henri vécut d'une vie quasi monastique. Sans négliger ses charges temporelles, il travailla activement à la réforme de l'Église en Germanie et en Italie.

SAINT HENRI II

Empereur d'Allemagne

(972-1024)

Saint Henri, surnommé le Pieux, appartenait à la famille impériale des Othons d'Allemagne, qui joua un si grand rôle au moyen âge. Touché d'une grâce spéciale de Dieu, il fit, jeune encore, un acte de hardiesse que lui eût dissuadé la prudence humaine, en promettant à Dieu de ne s'attacher qu'à Lui et en Lui vouant la continence perpétuelle. Héritier du royaume de Bavière par la mort de son père, il se vit obligé de prendre une épouse, pour ne pas s'exposer à la révolte de son royaume; le choix du peuple et le sien se porta sur la noble Cunégonde, digne en tous points de cet honneur. Elle avait fait, dès son adolescence, le même voeu que son mari.

Henri, devenu plus tard empereur d'Allemagne, justifia la haute idée qu'on avait conçue de lui par la sagesse de son gouvernement ainsi que par la pratique de toutes les vertus qui font les grands rois, les héros et les Saints. Il s'appliquait à bien connaître toute l'étendue de ses devoirs, pour les remplir fidèlement, il priait, méditait la loi divine, remédiait aux abus et aux désordres, prévenait les injustices et protégeait le peuple contre les excès de pouvoirs et ne passait dans aucun lieu sans assister les pauvres par d'abondantes aumônes. Il regardait comme ses meilleurs amis ceux qui le reprenaient librement de ses fautes, et s'empressait de réparer les torts qu'il croyait avoir causés.

Cependant son âme si élevée gémissait sous le poids du fardeau de la dignité royale. Un jour, comme il visitait le cloître de Vannes, il s'écria: "C'est ici le lieu de mon repos; voilà la demeure que j'ai choisie!" Et il demanda à l'abbé de le recevoir sur-le-champ. Le religieux lui répondit qu'il était plus utile sur le trône que dans un couvent; mais, sur les instances du prince, l'abbé se servit d'un moyen terme:

"Voulez-vous, lui dit-il, pratiquer l'obéissance jusqu'à la mort?

- Je le veux, répondit Henri.

- Et moi, dit l'abbé, je vous reçois au nombre de mes religieux; j'accepte la responsabilité de votre salut, si vous voulez m'obéir.

- Je vous obéirai.

- Eh bien! Je vous commande, au nom de l'obéissance, de reprendre le gouvernement de votre empire et de travailler plus que jamais à la gloire de Dieu et au salut de vos sujets." Henri se soumit en gémissant.

Sa carrière devait être, du reste, bientôt achevée. Près de mourir, prenant la main de Cunégonde, il dit à sa famille présente:

"Vous m'aviez confié cette vierge, je la rends vierge au Seigneur et à vous."

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours

de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/henri_II.html

Saint Henri,

Empereur romain-germanique

Né en 973, au moment où disparaissait son oncle, Othon le Grand, fondateur du Saint Empire Romain-Germanique, Henri était l’aîné des quatre enfants du duc de Bavière, Henri le Querelleur, devenu, sur le tard, Henri le Pacifique. Sa mère, Gisèle, sage et pieuse, qui l’avait formé à la vertu et à la prière dès sa prime enfance, le confia d’abord aux chanoines réguliers d’Hildesheim (Saxe), puis à saint Wolfgang, bénédictin évangélisateur de la Hongrie, alors évêque de Ratisbonne (mort le 31 octobre 994).

Lorsque son père mourut (28 août 995), Henri fut élu par la noblesse duc de Bavière et confirmé par le Roi. Dès 996, il accompagne Othon III en Italie pour secourir le Pape contre les Romains révoltés. Un peu plus tard, il épouse la vertueuse Cunégonde de Luxembourg. A la mort d’Othon III (23 janvier 1002), les ducs de Saxe et de Lorraine s’effacent devant la candidature d’Henri qui est élu par la diète de Werla, contre le duc Hermann de Souabe. Hermann gardant la rive gauche du Rhin, Henri renonce à se faire couronner à Aix-la-Chapelle et reçoit l’onction à Mayence. D’abord occupé à soumettre ses vassaux allemands, il doit aller pacifier l’Italie dont il reçoit la couronne, à Pavie, puis mâter les révoltes de Flandre et de Frise et, enfin, tenter de repousser le duc Boleslaw de Pologne.

Après avoir conforté la position du pape Benoît VIII, il en reçoit la couronne impériale, à Saint-Pierre de Rome (14 février 1014) et s’efforce vainement d’établir sa souveraineté sur le couloir rhodanien. A la demande de Benoît VIII, il descend au sud de l’Italie, menacé par les Byzantins : il entre à Bénévent (1002), prend Capoue, délivre le Mont-Cassin et regagne l’Allemagne en passant par Rome.

Tombé malade au début de 1024, il va cependant faire ses pâques à Magdebourg, reste à Goslar d’avril à juin où il prend la route de l’Ouest, mais il meurt au château de Grona. Il est enterré à la cathédrale de Bamberg.

Saint Henri, canonisé par Eugène III, fut, toute sa vie, zélé pour la réforme de l’Eglise pour quoi il préside de nombreux synodes en faveur de la stricte application de discipline canonique et de la condamnation des contrevenants, quel que soit leur rang ; il veilla scrupuleusement à nommer des évêques dignes de leurs fonctions et favorisa les monastères. La sainteté de sa vie est attestée par tous et l’on sait qu’il observa la chasteté conjugale. Cunégonde fut canonisée par Innocent III.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/07/13.php

Henri II. Déposition à Bamberg le 13 juillet 1024.

Canonisé en 1145. Mémoire au calendrier sous Urbain VIII le 13 juillet en la

fête de St Anaclet. Semidouble en 1668 le 15 juillet.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Henri, surnommé le Pieux, duc de Bavière, puis roi de Germanie, et enfin empereur des Romains, ne se contenta point des bornes étroites d’une domination temporelle. Aussi pour obtenir la couronne de l’immortalité, se montra-t-il le serviteur dévoué du Roi Éternel. Une -fois maître de l’empire, il mit son application et ses soins à étendre la religion, réparant avec beaucoup de magnificence les églises détruites par les infidèles et les enrichissant de largesses et de propriétés considérables, érigeant lui-même des monastères et d’autres établissements religieux, ou augmentant leurs revenus. L’évêché de Bamberg, fondé avec ses ressources patrimoniales, fut rendu par lui tributaire de Saint-Pierre et du Pontife romain. Benoît VIII étant fugitif, il le recueillit et le rétablit sur son Siège. C’est de ce Pape qu’il avait reçu la couronne impériale.

Cinquième leçon. Retenu au Mont-Cassin par une grave maladie, il en fut guéri d’une manière toute miraculeuse, grâce à l’intercession de saint Benoît. Il publia une charte importante spécifiant de grandes libéralités en faveur de l’Église romaine, entreprit pour la défendre une guerre contre les Grecs, et recouvra la Pouille, qu’ils avaient longtemps possédée. Ayant coutume de ne rien entreprendre sans avoir prié, il vit plus d’une fois l’Ange du Seigneur et les saints combattre aux premières lignes, pour sa cause. Avec le secours divin, il triompha des nations barbares plus par les prières que par les armes. La Pannonie était encore infidèle ; il sut l’amener à la foi de Jésus-Christ, en donnant sa sœur comme épouse au roi Etienne, qui demanda le baptême. Exemple rare : il unit l’état de virginité à l’état du mariage et sur le point de mourir, il remit sainte Cunégonde, son épouse, entre les mains de ses proches, dans son intégrité virginale.

Sixième leçon. Enfin après avoir disposé avec la plus grande prudence tout ce qui se rapportait à l’honneur et à l’utilité de l’empire, laissé ça et là, en Gaule, en Italie et en Germanie, des marques éclatantes de sa religieuse munificence, répandu au loin la plus suave odeur d’une vertu héroïque, et consommé les labeurs de cette vie, il fut appelé par le Seigneur à la récompense du royaume céleste, l’an du salut mil vingt-quatre. Sa sainteté l’a rendu plus célèbre que le sceptre qu’il a porté. Son corps fut déposé à Bamberg, dans l’église des saints Apôtres Pierre et Paul. Dieu le glorifia bientôt après par de nombreux miracles opérés auprès de son tombeau ; ces prodiges ayant été canoniquement prouvés, Eugène III l’a inscrit au catalogue des Saints.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Luc. Cap. 12, 35-40.

En ce temps-là : Jésus dit à ses disciples : Que vos reins soient ceints, et les lampes allumées dans vos mains. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Grégoire, Pape. Homelia 13 in Evang.

Septième leçon. Mes très chers frères, le sens de la lecture du saint Évangile que vous venez d’entendre est très clair. Mais de crainte qu’elle ne paraisse, à cause de sa simplicité même, trop élevée à quelques-uns, nous la parcourrons brièvement, afin d’en exposer la signification à ceux qui l’ignorent, sans cependant être à charge à ceux qui la connaissent. Le Seigneur dit : « Que vos reins soient ceints ». Nous ceignons nos reins lorsque nous réprimons les penchants de la chair par la continence. Mais parce que c’est peu de chose de s’abstenir du mal, si l’on ne s’applique également, et par des efforts assidus, à faire du bien, notre Seigneur ajoute aussitôt : « Ayez en vos mains des lampes allumées ». Nous tenons en nos mains des lampes allumées, lorsque nous donnons à notre prochain, par nos bonnes œuvres, des exemples qui l’éclairent. Le Maître désigne assurément ces œuvres-là, quand il dit : « Que votre lumière luise devant les hommes, afin qu’ils voient vos bonnes œuvres, et qu’ils glorifient votre Père qui est dans les cieux ».

Huitième leçon. Voilà donc les deux choses commandées : ceindre ses reins, et tenir des lampes ; ce qui signifie que la chasteté doit parer notre corps, et la lumière de la vérité briller dans nos œuvres. L’une de ces vertus n’est nullement capable de plaire à notre Rédempteur si l’autre ne l’accompagne. Celui qui fait des bonnes actions ne peut lui être agréable s’il n’a renoncé à se souiller par la luxure, ni celui qui garde une chasteté parfaite, s’il ne s’exerce à la pratique des bonnes œuvres. La chasteté n’est donc point une grande vertu sans les bonnes œuvres, et les bonnes œuvres ne sont rien sans la chasteté. Mais si quelqu’un observe les deux préceptes, il lui reste le devoir de tendre par l’espérance à la patrie céleste, et de prendre garde qu’en s’éloignant des vices, il ne le fasse pour l’honneur de ce monde.

Neuvième leçon. « Et vous, soyez semblables à des

hommes qui attendent que leur maître revienne des noces, afin que lorsqu’il

viendra et frappera à la porte, ils lui ouvrent aussitôt ». Le Seigneur vient

en effet quand il se prépare à nous juger ; et il frappe à la porte, lorsque,

par les peines de la maladie, il nous annonce une mort prochaine. Nous lui

ouvrons aussitôt, si nous l’accueillons avec amour. Il ne veut pas ouvrir à son

juge lorsqu’il frappe, celui qui tremble de quitter son corps, et redoute de

voir ce juge qu’il se souvient avoir méprisé ; mais celui qui se sent rassuré,

et par son espérance et par ses œuvres, ouvre aussitôt au Seigneur lorsqu’il

frappe à la porte, car il reçoit son Juge avec joie. Et quand le moment de la

mort arrive, sa joie redouble à la pensée d’une glorieuse récompense.

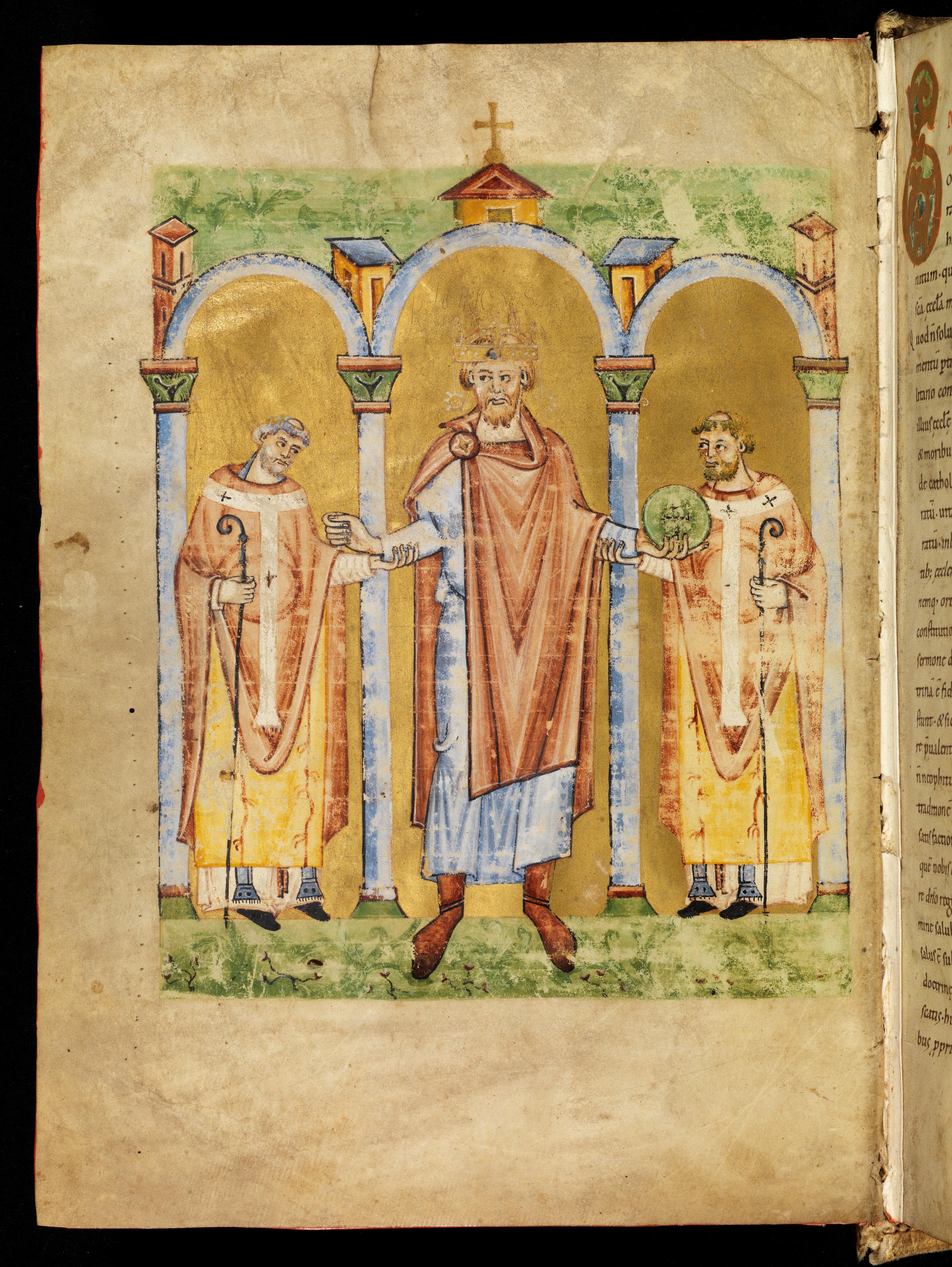

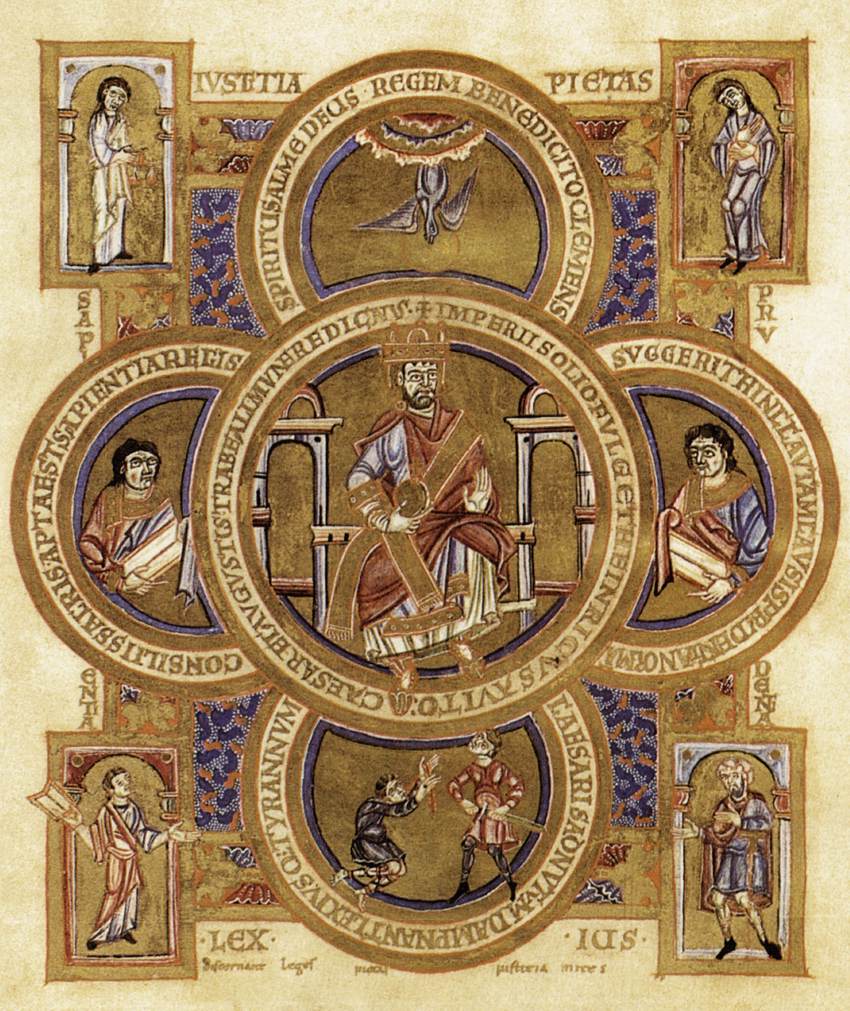

Henry II crowned as Emperor by Pope Benedict VIII in 1014.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Henri de Germanie, deuxième du nom quant à la royauté, premier quant à l’empire, fut le dernier représentant couronné de cette maison de Saxe issue d’Henri l’Oiseleur, à laquelle Dieu, au dixième siècle, confia la mission de relever l’œuvre de Charlemagne et de saint Léon III. Noble tige, où l’éclat des fleurs de sainteté qui brillent en ses rameaux l’emporte encore sur la puissance dont elle parut douée, quand elle implanta dans le sol allemand les racines des fortes institutions qui lui donnèrent consistance pour de longs siècles.

L’Esprit-Saint, qui divise comme il veut ses dons [1], appelait alors aux plus hautes destinées la terre où, plus que nulle part, s’était montrée l’énergie de son action divine dans la transformation des peuples. Acquise au Christ par saint Boniface et les continuateurs de son œuvre, la vaste contrée qui s’étend au delà du Rhin et du Danube était devenue le boulevard de l’Occident, sur lequel durant tant d’années elle avait versé la dévastation et la ruine. Loin de songer à soumettre à ses lois les redoutables tribus qui l’habitaient, Rome païenne, au plus haut point de sa puissance, avait eu pour suprême ambition la pensée d’élever entre elles et l’Empire un mur de séparation éternelle ; Rome chrétienne, plus véritablement souveraine du monde, plaçait dans ces régions le siège même du Saint-Empire Romain reconstitué par ses Pontifes. Au nouvel Empire de défendre les droits de la Mère commune, de protéger la chrétienté contre les barbares nouveaux, de conquérir à l’Évangile ou de briser les hordes hongroises et slaves, mongoles, tartares et ottomanes qui successivement viendront heurter ses frontières. Heureuse l’Allemagne, si toujours elle avait su comprendre sa vraie gloire, si surtout la fidélité de ses princes au vicaire de l’Homme-Dieu était restée à la hauteur de la foi de leurs peuples !

Dieu, en ce qui était de lui, avait soutenu magnifiquement les avances qu’il faisait à la Germanie. La fête présente marque le couronnement de la période d’élaboration féconde où l’Esprit-Saint, l’ayant créée comme à nouveau dans les eaux de la fontaine sacrée, voulut la conduire au plein développement de l’âge parfait qui convient aux nations. C’est dans cette période de formation véritablement créatrice que l’historien doit s’attacher principalement à étudier les peuples, s’il veut savoir ce qu’attend d’eux la Providence. Quand Dieu crée en effet, dans l’ordre de la vocation surnaturelle des hommes ou des sociétés coin nie dans celui de la nature elle-même, il dépose dès l’abord en son œuvre le principe de la vie plus ou moins supérieure qui doit être la sienne : germe précieux dont le développement, s’il n’est contrarié, doit lui faire atteindre sa fin ; dont par suite aussi la connaissance, pour qui sait l’observer avant toute déviation, manifeste clairement à l’endroit de l’œuvre en question la pensée divine. Or, maintes fois déjà nous l’avons constaté depuis l’avènement de l’Esprit sanctificateur, le principe de vie des nations chrétiennes est la sainteté de leurs origines : sainteté multiple, aussi variée que la multiforme Sagesse de Dieu dont elles doivent être l’instrument [2], aussi distincte pour chacune d’elles que le seront leurs destinées ; sainteté le plus souvent descendant du trône, et douée par là du caractère social que trop de fois plus tard revêtiront aussi les crimes des princes, en raison même de ce titre de princes qui les fait devant Dieu représentants de leurs peuples. Déjà aussi nous l’avons vu [3] : au nom de Marie, devenue dans sa divine maternité le canal de toute vie pour le monde, c’est à la femme qu’est dévolue la mission d’enfanter devant Dieu les familles des nations [4] qui seront l’objet de ses prédilections les plus chères ; tandis que les princes, fondateurs apparents des empires, occupent par leurs hauts faits l’avant-scène de l’histoire, c’est elle qui, dans le douloureux secret de ses larmes et de ses prières, féconde leurs œuvres, élève leurs desseins au-dessus de la terre et leur obtient la durée.

L’Esprit ne craint point de se répéter dans cette glorification de la divine Mère ; aux Clotilde, Radegonde et Bathilde, qui pour elles donnèrent en des temps laborieux les Francs à l’Église, répondent sous des cieux différents, et toujours à l’honneur de la bienheureuse Trinité, Mathilde, Adélaïde et Cunégonde, joignant sur leurs fronts la couronne des saints au diadème de la Germanie. Sur le chaos du dixième siècle, d’où l’Allemagne devait sortir, plane sans interruption leur douce figure, plus forte contre l’anarchie que le glaive des Othon, rassérénant dans la nuit de ces temps l’Église et le monde. Au commencement enfin de ce siècle onzième qui devait si longtemps encore attendre son Hildebrand, lorsque les anges du sanctuaire pleuraient partout sur des autels souillés, quel spectacle que celui de l’union virginale dans laquelle s’épanouit cette glorieuse succession qui, comme lasse de donner seulement des héros à la terre, ne veut plus fructifier qu’au ciel ! Pour la patrie allemande, un tel dénouement n’était pas abandon, mais prudence suprême ; car il engageait Dieu miséricordieusement au pays qui, du sein de l’universelle corruption, faisait monter vers lui ce parfum d’holocauste : ainsi, à l’encontre des revendications futures de sa justice, étaient par avance comme neutralisées les iniquités des maisons de Franconie el de Souabe, qui succédèrent à la maison de Saxe et n’imitèrent pas ses vertus.

Que la terre donc s’unisse au ciel pour célébrer aujourd’hui l’homme qui donna leur consécration dernière aux desseins de l’éternelle Sagesse à cette heure de l’histoire ; il résume en lui l’héroïsme et la sainteté de la race illustre dont la principale gloire est de l’avoir, tout un siècle, préparé dignement pour les hommes et pour Dieu. Il fut grand pour les hommes, qui, durant un long règne, ne surent qu’admirer le plus de la bravoure ou de l’active énergie grâce auxquelles, présent à la fois sur tous les points de son vaste empire, toujours heureux, il sut comprimer les révoltes du dedans, dompter les Slaves à sa frontière du Nord, châtier l’insolence grecque au midi de la péninsule italique ; pendant que, politique profond, il aidait la Hongrie à sortir par le christianisme de la barbarie, et tendait au delà de la Meuse à notre Robert le Pieux une main amie qui eût voulu sceller, pour le bonheur des siècles à venir, une alliance éternelle entre l’Empire et la fille aînée de la sainte Église.

Époux vierge de la vierge Cunégonde, Henri fut grand aussi pour Dieu qui n’eut jamais de plus fidèle lieutenant sur la terre. Dieu dans son Christ était à ses yeux l’unique Roi, l’intérêt du Christ et de l’Église la seule inspiration de son gouvernement, le service de l’Homme-Dieu dans ce qu’il a de plus parfait sa suprême ambition. Il comprenait que la vraie noblesse, aussi bien que le salut du monde, se cachait dans ces cloîtres où les âmes d’élite accouraient pour éviter l’universelle ignominie et conjurer tant de ruines. C’était la pensée qui, au lendemain de son couronnement impérial, l’amenait à Cluny, et lui faisait remettre à la garde de l’insigne abbaye le globe d’or, image du monde dont la défense venait de lui être confiée comme soldat du vicaire de Dieu ; c’était l’ambition qui le jetait aux genoux de l’Abbé de Saint-Vannes de Verdun, implorant la grâce d’être admis au nombre de ses moines, et faisait qu’il ne revenait qu’en gémissant et contraint par l’obéissance au fardeau de l’Empire.

Par moi règnent les rois, par moi les princes exercent l’empire [5]. Cette parole descendue des cieux, vous l’avez comprise, ô Henri ! En des temps pleins de crimes, vous avez su où étaient pour vous le conseil et la force [6]. Comme Salomon vous ne vouliez que la Sagesse, et comme lui vous avez expérimenté qu’avec elle se trouvaient aussi les richesses et la gloire et la magnificence [7] ; mais plus heureux que le fils de David, vous ne vous êtes point laissé détourner de la Sagesse vivante par ces dons inférieurs qui, dans sa divine pensée, étaient plus l’épreuve de votre amour que le témoignage de celui qu’elle-même vous portait. L’épreuve, ô Henri, a été convaincante : c’est jusqu’au bout que vous avez marché dans les voies bonnes, n’excluant dans votre âme loyale aucune des conséquences de l’enseignement divin ; peu content de choisir comme tant d’autres des meilleurs les pentes plus adoucies du chemin qui mène au ciel, c’est par le milieu des sentiers de la justice [8] que, suivant de plus près l’adorable Sagesse, vous avez fourni la carrière en compagnie des parfaits.

Qui donc pourrait trouver mauvais ce qu’approuve Dieu, ce que conseille le Christ, ce que l’Église a canonisé en vous et dans votre noble épouse ? La condition des royautés de la terre n’est pas lamentable à ce point que l’appel de l’Homme-Dieu ne puisse parvenir à leurs trônes ; l’égalité chrétienne veut que les princes ne soient pas moins libres que leurs sujets de porter leur ambition au delà de ce monde. Une fois de plus, au reste, les faits ont montré dans votre personne, que pour le monde même la science des saints est la vraie prudence [9]. En revendiquant votre droit d’aspirer aux premières places dans la maison du Père qui est aux cieux, droit fondé pour tous les enfants de ce Père souverain sur la commune noblesse qui leur vient du baptême, vous avez brillé comme un phare éclatant sous le ciel le plus sombre qui eût encore pesé sur l’Église, vous avez relevé les âmes que le sel de la terre, affadi, foulé aux pieds, ne préservait plus de la corruption [10]. Ce n’était pas à vous sans doute qu’il appartenait de réformer directement le sanctuaire ; mais, premier serviteur de la Mère commune, vous saviez faire respecter intrépidement ses anciennes lois, ses décrets nouveaux toujours dignes de l’Époux, toujours saints comme l’Esprit qui les dicte à tous les âges : en attendant la lutte formidable que l’Épouse allait engager bientôt, votre règne interrompit la prescription odieuse que déjà Satan invoquait contre elle.

En cherchant premièrement pour vous le royaume de Dieu

et sa justice [11], vous étiez loin également de frustrer votre patrie

d’origine et le pays qui vous avait appelé à sa tête. C’est bien à vous entre

tous que l’Allemagne doit l’affermissement chez elle de cet Empire qui fut sa

gloire parmi les peuples, jusqu’à ce qu’il tombât dans nos temps pour ne plus

se relever nulle part. Vos œuvres saintes eurent assez de poids dans la balance

des divines justices pour l’emporter, lorsque depuis longtemps déjà vous aviez

quitté la terre, sur les crimes d’un Henri IV et d’un Frédéric II, bien faits

pour compromettre à tout jamais l’avenir de la Germanie. Du trône que vous

occupez dans les cieux, jetez un regard de commisération sur ce vaste domaine

du Saint-Empire, qui vous dut de si beaux accroissements, et que l’hérésie a

désagrégé pour toujours ; confondez les constructeurs nouveaux venus d’au delà

de l’Oder, que l’Allemagne des beaux temps ne connut pas, et qui voudraient

sans le ciment de l’antique foi relever à leur profit les grandeurs du passé ;

préservez d’un affaissement plus douloureux encore que celui dont nous sommes

les témoins attristés, les nobles parties de l’ancien édifice restées à

grand-peine debout parmi les ruines. Revenez, ô empereur des grands âges,

combattre pour l’Église ; ralliez les débris de la chrétienté sur le terrain

traditionnel des intérêts communs à toute nation catholique : et cette

alliance, que votre haute politique avait autrefois conclue, rendra au monde la

sécurité, la paix, la prospérité que ne lui donnera point l’instable équilibre

avec lequel il reste à la merci de tous les coups de la force.

[1] I Cor. XII, 11.

[2] Eph. III, 10 ; I Petr. IV, 10.

[3] Le Temps après la Pentecôte, t. III, Sainte Clotilde.

[4] Psalm. XXI, 28.

[5] Prov. VIII, 15-16.

[6] Ibid. 14.

[7] Ibid. 18.

[8] Ibid. 20.

[9] Prov. IX, 10.

[10] Matth. V, 13-16.

[11] Ibid. VI, 33.

Bhx cardinal Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Un empereur du Saint-Empire romain-germanique, qui monte au sommet de la perfection chrétienne et de la sainteté, ce n’est pas un fait commun ; aussi la fête de ce jour appelle-t-elle toute notre pieuse attention sur les fastes glorieux de saint Henri.

Il semble en effet que les vertus, les béatitudes du sermon sur la montagne, rencontrent une difficulté spéciale quand on les doit pratiquer sur un trône glorieux, au milieu du faste des richesses, de la puissance, des triomphes, et non dans une situation humble et pénible.

L’Écriture elle-même traite d’extraordinaire le cas d’un riche qui n’a pas couru après l’or [12], et la liturgie, dans les rares occasions où elle a dû célébrer les louanges des saints rois, n’a pas manqué de faire remarquer combien est plus ardue et plus glorieuse la victoire remportée par eux contre les vaines séductions de la puissance mondaine.

Il sembla qu’au XIe siècle Henri II ressemblait à Constantin. A plusieurs reprises il descendit en Italie pour défendre contre les factions le Pontife légitime. Par amour pour l’Église romaine, il prit les armes contre les Grecs qui avaient occupé le sud de l’Italie. Il employa ses trésors à fonder des sièges épiscopaux, à enrichir des églises, à doter des monastères ; bien plus : il envoya un jour à l’abbaye de Cluny, pour qu’ils fussent offerts au Sauveur, ses insignes impériaux eux-mêmes. Saint Henri mourut le 13 juillet 1024 et fut canonisé par le bienheureux Eugène III en 1145. Voici son épitaphe primitive :

HENRIC • AVGVSTVS • VIRTVTVM • GERMINE • IVSTVS

HÆC • SERVAT • CVIVS • VISCERA • PVTRIS • HVMVS

SPLENDOR • ERAT • LEGVM • SPECVLVM • LVX • GEMMAQVE • REGVM

AD • CÆLOS • ABIIT • NON • MORIENS • OBIIT

IDIBVS • IN • TERRIS • VEXANTEM • PONDERA • CARNIS

IVLIVS • ÆTHEREO • SVMPSERAT • IMPERIO

Cette urne conserve la dépouille mortelle et corrompue

de l’empereur Henri, juste et auteur d’œuvres vertueuses.

Il était la splendeur du droit, le miroir, la lumière, la perle des monarques.

Il est parti pour le ciel et il est mort pour ne plus mourir.

Il s’est envolé à l’empire céleste aux ides de juillet,

ainsi libéré du poids de la chair.

La messe est du commun. La première collecte est la

suivante : « Seigneur qui, en ce jour, avez voulu élever du faîte de l’empire

terrestre au royaume céleste le bienheureux Henri ; nous vous demandons que,

comme votre grâce le prévint afin qu’il méprisât les attraits du siècle, vous

nous accordiez à nous aussi de l’imiter en foulant aux pieds les séductions du

monde, pour que nous arrivions ensuite à vous avec le cœur purifié de toute

souillure ».

[12] Eccli., XXXI, 8.

Dom Pius Parsch, Le guide dans l’année liturgique

Un empereur allemand au nombre des saints !

Saint Henri. — Jour de mort : 13 juillet 1024. Tombeau : à la cathédrale Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul, à Bamberg. Image : on le représente en empereur, avec un lis et une église. Vie : Henri et Cunégonde ; deux saints époux sur le trône impérial d’Allemagne ! Henri II (1002-1024) unissait en lui, comme souverain, la sublimité et la douceur de l’esprit de sacrifice à la plus forte personnalité. Voici ce que la prière des Heures nous raconte de lui : Il n’entreprenait rien sans avoir d’abord prié. Plus d’une fois avant le combat il vit son ange gardien et de saints martyrs protecteurs combattre pour lui et veiller sur sa vie. Il lutta contre les barbares plus par la prière que par les armes. Il conquit à la foi chrétienne la Hongrie encore païenne en donnant sa sœur comme épouse au roi Étienne, à la condition qu’il se fît baptiser. Il consacra ses biens à la fondation d’églises et de monastères ; il envoya un jour ses bijoux royaux à l’abbaye de Cluny pour les offrir au Seigneur. Même après son mariage, il garda avec une rare constance la virginité et, à l’approche de la mort, il rendit intacte à ses parents son épouse Cunégonde. Le saint s’est acquis un souvenir durable dans la liturgie romaine, car c’est à sa demande que le Credo fut introduit dans la messe.

Pratique : « Seigneur, qui lui as permis par l’abondance de ta grâce de triompher des attraits du monde, accorde-nous aussi d’éviter, à son exemple, les séductions de ce monde et de parvenir à toi avec un cœur pur » (oraison). Pratiquons la pureté conforme à notre état. Au fond, les soins que nous prodigue la sainte liturgie ne tendent pas à autre chose qu’à la pureté de vie. — La messe (Os justi) est celle du commun des confesseurs.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/15-07-St-Henri-empereur-et

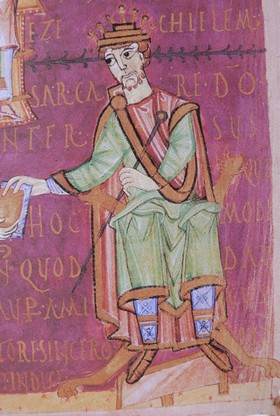

HENRI II LE SAINT (973-1024) empereur

germanique (1002-1024)

Duc de Bavière, Henri II

est élu empereur à la mort de son cousin Othon III, dépourvu d'héritier

direct. Mais son avènement est précédé d'une longue lutte de succession et

suivi d'un conflit avec les comtes de Luxembourg et la noblesse du royaume de

Bourgogne, qui refuse de le reconnaître comme son suzerain. Prince actif et

doué, il a maintenu l'unité dans la tradition ottonienne, dont il est le

dernier descendant indirect. Il consacre ses efforts à l'achèvement de la

constitution de l'Église ottonienne dont il met les biens au service de

l'Empire. Il s'appuie sur l'Église qu'il dote richement, nomme des hommes de

confiance aux sièges épiscopaux, impose une réforme monastique,

multiplie les synodes impériaux et entreprend une grande réforme, en accord

avec le pape, à la veille de sa mort. En 1007, Henri II fonde l'évêché de Bamberg,

doté de vastes seigneuries, qui va contribuer à sa légende. Reprenant les

ambitions italiennes de ses prédécesseurs, il organise trois expéditions en

Italie, où il rétablit l'autorité impériale. Il se fait couronner roi d'Italie

à Pavie en 1004 et empereur à Rome en

1014. Mais, moins heureux avec le duc de Pologne, Boleslas Ier,

qu'il combat pendant douze ans avec le concours de tribus slaves païennes, il

doit accepter l'indépendance de fait de la Pologne et lui consentir la Lusace

en fief. Sa générosité à l'égard de l'Église lui a valu de recevoir le surnom

de saint et d'être canonisé en 1146.

Bernard VOGLER, « HENRI II LE

SAINT (973-1024) - empereur germanique

(1002-1024) », Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne],

consulté le 13 juillet 2017. URL

: http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/henri-ii-le-saint/

SOURCE : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/henri-ii-le-saint/

Also known as

Good King Henry

Heinrich, Duke of Bavaria

Profile

Son of Gisella of Burgundy and

Henry II the Quarrelsome, Duke of Bavaria. Educated at

the cathedral school in Hildesheim by bishop Wolfgang

of Regensburg. Became Duke of Bavaria himself

in 995 upon

his father‘s death,

which ended Henry’s thoughts of becoming a priest.

Ascended to the throne of Germany in 1002.

Crowned King of Pavia, Italy on 15 May 1004. Married Saint Cunegunda,

but was never a father.

Some sources claim the two lived celibately, but there is no evidence either

way.

Henry’s brother rebelled against his power, and Henry

was forced to defeat him on the battlefield, but later forgave him, and the two

reconciled. Henry was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1014 by Pope Benedict

VIII; he was the last of the Saxon dynasty

of emperors. Founded schools,

quelled rebellions, protected the frontiers, worked to establish a stable peace

in Europe,

and to reform the Church while

respecting its independence. Fostered missions,

and established Bamberg, Germany as

a center for missions to

Slavic countries. Started the construction of the cathedral at Basel, Switzerland;

it took nearly 400 years to complete. Both Henry and Saint Cunegunda were prayerful people,

and generous to the poor.

At one point he was cured of an unnamed illness by

the touch of Saint Benedict

of Nursia at Monte

Cassino. He became somewhat lame in

his later years. Widower.

Following Cunegunda‘s death,

he considered becoming a monk, but

the abbot of

Saint-Vanne at Verdun, France refused

his application, and told him to keep his place in the world where he could do

much good for people and the advancement of God‘s kingdom.

Born

6 May 972 at

Albach, Hildesheim, Bavaria, Germany

13 July 1024 at

Pfalz Grona, near Göttingen, Saxony (in

modern Germany)

of natural causes

1146 by Pope Blessed Eugene

III

people

rejected by religious orders

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

True

Historical Stories for Catholic Children, by Josephine Portuondo

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

images

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

MLA Citation

“Saint Henry II“. CatholicSaints.Info. 3 July

2021. Web. 15 July 2021. <http://catholicsaints.info/saint-henry-ii/>

SOURCE : http://catholicsaints.info/saint-henry-ii/

Couronnement d'Henri II, sacramentaire, Bibliothèque d'État de Bavière, Clm4456, f.11

St. Henry

St. Henry, son of Henry, Duke of Bavaria, and of

Gisella, daughter of Conrad, King of Burgundy, was born in 972. He received an

excellent education under the care of St. Wolfgang, Bishop of Ratisbon. In 995,

St. Henry succeeded his father as Duke of Bavaria, and in 1002, upon the death

of his cousin, Otho III, he was elected emperor.

Firmly anchored upon the great eternal truths, which

the practice of meditation kept alive in his heart, he was not elated by this

dignity and sought in all things, the greater glory of God. He was most

watchful over the welfare of the Church and exerted his zeal for the

maintenance of ecclesiastical discipline through the instrumentality of the

Bishops. He gained several victories over his enemies, both at home and abroad,

but he used these with great moderation and clemency.

In 1014, he went to Rome and received the imperial

crown at the hands of Pope Benedict VIII. On that occasion he confirmed the

donation, made by his predecessors to the Pope, of the sovereignty of Rome and

the exarchate of Ravenna. Circumstances several times drove the holy Emperor into

war, from which he always came forth victorious. He led an army to the south of

Italy against the Saracens and their allies, the Greeks, and drove them from

the country.

The humility and spirit of justice of the Saint were

equal to his zeal for religion. He cast himself at the feet of Herebert, Bishop

of Cologne, and begged his pardon for having treated him with coldness, on

account of a misunderstanding. He wished to abdicate and retire into a

monastery, but yielded to the advice of the Abbot of Verdun, and retained his

dignity. Both he and his wife, St. Cunegundes, lived in perpetual chastity, to

which they had bound themselves by vow.

The Saint made numerous pious foundations, gave liberally to pious institutions and built the Cathedral of Bamberg. His holy death occurred at the castle of Grone, near Halberstad, in 1024. His feast day is July 13th. He is the patron saint of the childless, of Dukes, of the handicapped and those rejected by Religious Order.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-henry/

St. Henry II

German King

and Holy Roman Emperor, son of Duke Henry

II (the Quarrelsome) and of the Burgundian Princess Gisela; b. 972; d. in his palace

of Grona, at Gottingen, 13 July, 1024.

Like his predecessor, Otto

III, he had the literary education of

his time. In his youth he had been destined for the priesthood.

Therefore he became acquainted

with ecclesiastical interests at an early age.

Willingly he performed pious practices,

gladly also he strengthened the Church of Germany,

without, however, ceasing to regard ecclesiastical institutions

as pivots of his power, according to the views of Otto

the Great. With all his learning and piety,

Henry was an eminently sober man, endowed with sound, practical common sense.

He went his way circumspectly, never attempting anything but the possible and,

wherever it was practicable, applying the methods of amiable and reasonable

good sense. This prudence,

however, was combined with energy and conscientiousness. Sick and suffering

from fever, he traversed the empire in order to maintain peace. At all times he

used his power to adjust troubles. The masses especially he wished to help.

The Church,

as the constitutional Church of Germany,

and therefore as the advocate of German unity and of the claims of inherited

succession, raised Henry to the throne. The new king straightway resumed the

policy of Otto

I both in domestic and in foreign affairs. This policy first appeared

in his treatment of the Eastern Marches. The encroachments of Duke Boleslaw,

who had founded a great kingdom, impelled him to intervene. But his success was

not marked.

In Italy the

local and national opposition to the universalism of the German king had found

a champion in Arduin of Ivrea.

The latter assumed the Lombard crown in 1002. In 1004 Henry crossed the Alps.

Arduin yielded to his superior power.

The Archbishop of Milan now crowned him King of Italy. This rapid success was largely due to the fact that

a large part of the Italian episcopate upheld the idea of the Roman Empire and that of the unity

of Church and State.

On his second

expedition to Rome, occasioned by the dispute between the Counts

of Tuscany and the Crescentians over the nomination to the papal throne, he was crowned emperor on 14 February, 1014. But it was not

until later, on his third expedition to Rome, that he was able to restore the prestige of the

empire completely.

Before this happened, however, he was obliged to

intervene in the west. Disturbances were especially prevalent throughout the

entire northwest. Lorraine caused great trouble. The Counts of Lutzelburg

(Luxemburg), brothers-in-law of the king, were the heart and soul of

the disaffection in that country. Of these men, Adalbero had made himself Bishop of Trier by uncanonical methods (1003); but he was not

recognized any more than his brother Theodoric, who had had himself

elected Bishop of Metz.

True to his duty,

the king could not be induced to abet any selfish family policy

at the expense of the empire. Even

though Henry, on the whole, was able to hold his own against these Counts of

Lutzelburg, still the royal authority suffered greatly by loss of prestige in

the northwest.

Burgundy afforded compensation for this. The lord of

that country was Rudolph, who, to protect himself against his vassals, joined

the party of Henry II, the son of his sister, Gisela, and to Henry the

childless duke bequeathed his duchy, despite the opposition of the nobles

(1006). Henry had to undertake several campaigns before he was able to enforce

his claims. He did not achieve

any tangible result, he only bequeathed the theoretical claims on Burgundy to his successors.

Better fortune awaited the king in the central and

eastern parts of the empire. It

is true that he had a quarrel with the Conradinians over

Carinthia and Swabia: but Henry proved victorious because his kingdom rested on the

solid foundation of intimate alliance with the Church.

That his attitude towards the Church was

dictated in part by practical reasons, primarily he promoted the institutions

of the Church chiefly

in order to make them more useful supports his royal power, is clearly shown by

his policy. How boldly Henry

posed as the real ruler of the Church appears particularly in the establishment of

the See of Bamberg, which was entirely his own scheme.

He carried out this measure, in 1007, in spite of the

energetic opposition of the Bishop of

Wurzburg against this change in the organization of the Church.

The primary purpose of the new bishopric was

the germanization of the regions on the Upper Main and the Regnitz, where the

Wends had fixed their homes. As a large part of the environs of Bamberg belonged

to the king, he was able to furnish rich endowments for the new bishopric.

The importance of Bamberg lay

principally in the field of culture, which it promoted chiefly by its

prosperous schools.

Henry, therefore, relied on the aid of the Church against

the lay powers, which had become quite formidable. But he made no concessions

to the Church.

Though naturally pious,

and though well acquainted with ecclesiastical culture,

he was at bottom a stranger to her spirit. He disposed of bishoprics autocratically.

Under his rule the bishops,

from whom he demanded unqualified obedience, seemed to be nothing but officials

of the empire. He demanded the same obedience from the abbots.

However, this political dependency did not injure the internal life of the

German Church under Henry. By

means of its economic and educational resources the Church had a blessed influence in this epoch.

But it was precisely this civilizing power of the

German Church that aroused the suspicions of the reform party. This was

significant, because Henry was more and more won over to the ideas of

this party. At a synod at Goslar he confirmed decrees that tended to realize

the demands made by the reform party. Ultimately this tendency could not fail to subvert the Othonian system,

moreover could not fail to awaken the opposition of the Church of Germany as it was constituted.

This hostility on the part of the German Church came

to a head in the emperor's dispute with Archbishop Aribo of Mainz.

Aribo was an opponent of the reform movement of the monks of

Cluny. The Hammerstein marriage imbroglio afforded the opportunity he desired

to offer a bold front against Rome.

Otto von Hammerstein had

been excommunicated by Aribo on account of his marriage with

Irmengard, and the latter had successfully appealed to Rome.

This called forth the opposition of the Synod of

Seligenstadt, in 1023, which forbade an appeal to Rome without

the consent of the bishop.

This step meant open rebellion against the idea of

church unity, and its ultimate result would have been the founding of a German

national Church. In this dispute the emperor was entirely on the side of the

reform party. He even wanted to institute international proceedings against the

unruly archbishop by

means of treaties with the French king. But his death prevented this.

Before this Henry had made his third journey

to Rome in

1021. He came at the request of the loyal Italian bishops,

who had warned him at Strasburg of

the dangerous aspect of the Italian situation, and also of the pope,

who sought him out at Bamberg in

1020. Thus the imperial power, which had already begun to withdraw from Italy,

was summoned back thither. This time the object was to put an end to

the supremacy of the Greeks in Italy.

His success was not complete;

he succeeded, however, in restoring the prestige of the empire in northern and

central Italy.

Henry was far too reasonable a man to think seriously

of readopting the imperialist plans of his predecessors. He was satisfied to

have ensured the dominant position of the empire in Italy within

reasonable bounds. Henry's power

was in fact controlling, and this was in no small degree due to the fact that

he was primarily engaged in solidifying the national foundations of his

authority.

The later ecclesiastical legends

have ascribed ascetic traits to this ruler, some of which certainly cannot

withstand serious criticism. For

instance, the highly varied theme of his virgin marriage to Cunegond has

certainly no basis in fact.

The Church canonized this emperor in 1146, and his wife Cunegond in

1200.

Kampers, Franz. "St. Henry II." The

Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1910. 15 Jul.

2015<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07227a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by HCC.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. June

1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal

Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07227a.htm

Alte Heinrichskirche, Mauthausen

July 15

St. Henry II., Emperor

From his authentic life, published by Surius and

D’Andilly, and from the historians Sigebert, Glaber, Dithmar, Lambert of

Aschaffenburg, Leo Urbevetanus in his double chronicle of the popes and

emperors, in Deliciæ Eruditor, t. 1, and 2. Aventin’s Annals of Bavaria,

&c.

A.D. 1024.

ST. HENRY, surnamed the Pious and the Lame, was son of

Henry, duke of Bavaria, and of Gisella, daughter of Conrad, king of Burgundy,

and was born in 972. He was descended from Henry, duke of Bavaria, son of the

emperor Henry the Fowler, and brother of Otho the Great, consequently our saint

was near akin to the three first emperors who bore the name of Otho. St.

Wolfgang, the bishop of Ratisbon, being a prelate the most eminent in all

Germany for learning, piety, and zeal, our young prince was put under his

tuition, and by his excellent instructions and example he made from his infancy

wonderful progress in learning and in the most perfect practice of Christian

virtue. The death of his dear master and spiritual guide, which happened in

994, was to him a most sensible affliction. In the following year he succeeded

his father in the dutchy of Bavaria, and in 1002, upon the death of his cousin

Otho III., he was chosen emperor. 1 He

was the same year crowned king of Germany at Mentz, by the archbishop of that

city. He had always before his eyes the extreme dangers to which they are

exposed who move on the precipice of power, and that all human things are like

edifices of sand, which every breath of time threatens to overturn or deface;

he studied the extent and importance of the obligations which attended his

dignity; and by the assiduous practice of humiliations, prayer, and pious

meditation, he maintained in his heart the necessary spirit of humility and

holy fear, and was enabled to bear the tide of prosperity and honour with a

constant evenness of temper. Sensible

of the end for which alone he was exalted by God to the highest temporal

dignity, he exerted his most strenuous endeavours to promote in all things the

divine honour, the exaltation of the church, and the peace and happiness of his

people

Soon after his accession to the throne he resigned the

dukedom of Bavaria, which he bestowed on his brother-in-law Henry, surnamed

Senior. He procured a national council of the bishops of all his dominions,

which was assembled at Dortmund, in Westphalia, in 1005, in order to regulate

many points of discipline, and to enforce a strict observance of the holy

canons. It was owing to his zeal that many provincial synods were also held for

the same purpose in several parts of the empire. He was himself present at that

of Frankfort in 1006, and at another of Bamberg in 1011. The protection he owed

his subjects engaged him sometimes in wars, in all which he was successful. By

his prudence, courage, and clemency he stifled a rebellion at home in the

beginning of his reign, and without striking a stroke compelled the

malecontents to lay down their arms at his feet, which when they had done he

received them into favour. Two years after he quelled another rebellion in

Italy, when Ardovinus or Hardwic, a Lombard lord, had caused himself to be

crowned king at Milan. This nobleman, after his defeat, made his submission,

and obtained his pardon. When he had afterwards revolted a second time, the

emperor marched again into Italy, vanquished him in battle, and deprived him of

his territories, but did not take away his life, and Ardovinus became a monk.

After this second victory, St. Henry went in triumph to Rome, where, in 1014,

he was crowned emperor with great solemnity by Pope Benedict VIII. On that

occasion, to give a proof of his devotion to the holy see, he confirmed to it,

by an ample diploma, the donation made by several former emperors, of the

sovereignty of Rome and the exarchate of Ravenna: 2 and

after a short stay at Rome, took leave of the pope, and in his return to

Germany kept the Easter holydays at Pavia; then he visited the monastery of

Cluni, on which he bestowed the imperial globe of gold which the pope had given

him, and a gold crown enriched with precious stones. He paid his devotions in

other monasteries on the road, leaving in every one of them some rich monument

of his piety and liberality. But the most acceptable offering which he made to

God was the fervour and purity of affection with which he renewed the

consecration of his soul to God in all places where he came, especially at the

foot of the altars. Travelling through Liege and Triers, he arrived at Bamberg,

in which city he had lately founded a rich episcopal see, and had built a most

stately cathedral in honour of St. Peter, which Pope John XVIII. took a journey

into Germany to consecrate in 1019. The emperor obtained of this pope, by an

honourable embassy, the confirmation of this and all his other pious

foundations; for he built and endowed other churches with the two monasteries

at Bamberg, and made the like foundations in several other places; thus extending

his zealous views to promote the divine honour and the relief of the poor to

the end of time. Bruno, bishop

of Ausburg, the emperor’s brother, Henry, duke of Bavaria, and other relations

of the saint complained loudly that he employed his patrimony on such religious

foundations, and the duke of Bavaria and some others took up arms against him

in 1010; but he defeated them in the field; then pardoned the princes engaged

in the revolt, and restored to them Bavaria and their other territories which

he had seized.

The idolatrous inhabitants of Poland and Sclavonia had

some time before laid waste the diocess of Meersburg, and destroyed that and

several other churches. St. Henry marched against those barbarous nations, and

having put his army under the protection of the holy martyrs St. Laurence, St.

George, and St. Adrian, who are said to have been seen in the battle fighting

before him, he defeated the infidels. He had made a vow to re-establish the see

of Meersburg in case he obtained the victory, and he caused all his army to

communicate the day before the battle, which was fought near that city. The

barbarians were seized with a panic fear in the beginning of the action, and

submitted at discretion. The princes of Bohemia rebelled, but were easily brought

back to their duty. The victorious emperor munificently repaired and restored

the episcopal sees of Hildesheim, Magdeburg, Strasburg, Misnia, and Meersburg,

and made all Poland, Bohemia, and Moravia tributary to the empire. He procured

holy preachers to be sent to instruct the Bohemians and Polanders in the faith.

Those have been mistaken who

pretend that St. Henry converted St. Stephen, king of Hungary, for that prince

was born of Christian parents; but our saint promoted his zealous endeavours,

and had a great share in his apostolic undertakings for the conversion of his

people.

The protection of

Christendom, and especially of the holy see, obliged St. Henry to lead an army

to the extremity of Italy, 3 where he vanquished the conquering Saracens,

with their allies the Greeks, and drove them out of Italy, left a governor in

the provinces which he had recovered, and suffered the Normans to enjoy the

territories which they had then wrested from the infidels, but restrained them

from turning their arms towards Naples or Benevento. He

came back by Mount Cassino, and was honourably received at Rome; but during his

stay in that city, by a painful contraction of the sinews in his thigh, became

lame and continued so till his death. He passed by Cluni, and in the duchy of

Luxemburg had an interview with Robert, king of France, son and successor of

Hugh Capet. 4 It

had been agreed that, to avoid all disputes of pre-eminence, the two princes

should hold their conference in boats on the river Meuse, which, as Glaber

writes, was at that time the boundary that parted their dominions; but Henry,

impatient to embrace and cement a friendship with that great and virtuous king,

paid the first visit to Robert in his tent, and afterwards received him in his

own. A war had broke out between these two princes in 1006, and Henry gave the

French a great overthrow; but being desirous only to govern his dominions in

peace, he entered into negotiations which produced a lasting peace. In this

interview, which was held in 1023, the conference of the two princes turned on

the most important affairs of church and state, and on the best means of

advancing piety, religion, and the welfare of their subjects. After the most

cordial demonstrations of sincere friendship they took leave of each other, and

St. Henry proceeded to Verdun and Metz. He made frequent progresses through his

dominions only to promote piety, enrich all the churches, relieve the poor,

make a strict inquiry into all public disorders and abuses, and prevent unjust

usurpations and oppressions. He

desired to have no other heir on earth but Christ in his members, and wherever

he went he spread the odour of his piety, and his liberalities on the poor.

It is incredible how attentive he was to the smallest

affairs amidst the multiplicity of business which attends the government of the

state; nothing seemed to escape him; and whilst he was most active and vigilant

in every duty which he owed to the public, he did not forget that the care of

his own soul and the regulation of his interior was his first and most

essential obligation. He was sensible that pride and vain-glory are the most

dangerous of all vices, and that they are the most difficult to be discovered,

and the last that are vanquished in the spiritual warfare; that humility is the

very foundation of all true virtue, and our progress in it the measure of our

advancement in Christian perfection. Therefore, the higher he was exalted in

worldly honours the more did he study to humble himself, and it is said of him,

that never was greater humility seen under a diadem. He loved those persons

best who most freely put him in mind of his mistakes, and these he was always

most ready to confess, and to make for them the most ample reparation. Through

misinformations, he for some time harboured coldness towards St. Herebert,

archbishop of Cologn; but discovering the innocence and sanctity of that

prelate, he fell at his feet, and would not rise till he had received his

absolution and pardon. He banished flatterers from his presence, calling them

the greatest pests of courts; for none can put such an affront on a man’s

judgment and modesty, as to praise him to his face, but the base and most

wicked of interested and designing men, who make use of this artifice to

insinuate themselves into the favour of a prince, to abuse his weakness and

credulity, and to make him the dupe of their injustices. He who listens to them

exposes himself to many misfortunes and crimes, to the danger of the most

foolish pride and vain-glory, and to the ridicule and scorn of his flatterers

themselves; for a vanity that can publicly hear its own praises, openly unmasks

itself to its confusion. The Emperor Sigismund giving a flatterer a blow on the

face, called his fulsome praise the greatest insult that had ever been offered

him. St. Henry was raised by religion and humility above this abjectness of

soul which reason itself teaches us to abhor and despise. By the assiduous

mortification of the senses he kept his passions in subjection; for pleasure,

unless we are guarded against its assaults, steals upon us by insensible

degrees, smooths its passage to the heart by a gentle and insinuating address,

and softens and disarms the soul of all its strength. Nor is it possible for us

to triumph over unlawful sensual delights, unless we moderate and practise

frequent self-denials with regard to lawful gratifications. The love of the

world is a no less dangerous enemy, especially amidst honours and affluence;

and created objects have this quality that they first seduce the heart, and

then blind the understanding. By

conversing always in heaven, St. Henry raised his affections so much above the

earth as to escape this snare.

Prayer seemed the chief delight and support of his

soul; especially the public office of the church. Assisting one day at this

holy function at Strasburg, he so earnestly desired to remain always there to

sing the divine praises among the devout canons of that church, that, finding

this impossible, he founded there a new canonry for one who should always

perform that sacred duty in his name. In this spirit of devotion it has been

established that the kings of France are canons of Strasburg, Lyons, and some

other places; as in the former place the emperors, in the latter the dukes of

Burgundy, were before them. The holy sacrament of the altar and sacrifice of

the mass were the object of St. Henry’s most tender devotion. The blessed Mother

of God he honoured as his chief patroness, and among other exercises by which

he recommended himself to her intercession, it was his custom, upon coming to

any town, to spend a great part of the first night in watching and prayer in

some church dedicated to God under her name, as at Rome in St. Mary Major. He

had a singular devotion to the good angels and to all the saints. Though he

lived in the world so as to be perfectly disengaged from it in heart and

affection, it was his earnest desire entirely to renounce it long before his

death, and he intended to pitch upon the abbey of St. Vanne, at Verdun, for the

place of his retirement; but he was diverted from carrying this project into

execution, by the advice of Richard the holy abbot of that house. 5 He

had married St. Cunegonda, but lived with her in perpetual chastity, to which

they had mutually bound themselves by vow. It happened that the empress was

falsely accused of incontinency, and St. Henry was somewhat moved by the

slander; but she cleared herself by her oath, and by the ordeal trials, walking

over twelve red hot plough-shares without hurt. Her husband severely condemned

himself for his credulity, and made her the most ample satisfaction. In his

last illness he recommended her to her relations and friends, declaring that he

left her an untouched virgin. His health decayed some years before his death,

which happened at the castle of Grone, near Halberstadt, in 1024, on the 14th

of July, towards the end of the fifty-second year of his life; he having

reigned twenty-two years from his election, and ten years and five months from

his coronation at Rome. His body was interred in the cathedral at Bamberg, with

the greatest pomp, and with the unfeigned tears of all his subjects. The great

number of miracles by which God was pleased to declare his glory in heaven, procured

his canonization, which was performed by Eugenius III. in 1152. His festival is

kept on the day following that of his death. 6

Those who by

honours, dignities, riches, or talents are raised by God in the world above the

level of their fellow-creatures, have a great stewardship, and a most rigorous

account to give at the bar of divine justice, their very example having a most

powerful influence over others. This St. Fulgentius

observed, writing to Theodorus, a pious Roman senator: 7 “Though,”

said he, “Christ died for all men, yet the perfect conversion of the great ones

of the world brings great acquisitions to the kingdom of Christ. And they who

are placed in high stations must necessarily be to very many an occasion of

eternal perdition or of salvation. And as they cannot go alone, so either a high degree of glory or an

extraordinary punishment will be their everlasting portion.”

Note 1. The empire of the West, which had been

extinguished in Augustulus, was restored in the year 800, in the person of

Charlemagne, king of France, who extended his conquests into part of Spain,

almost all Italy, all Flanders and Germany, and part of Hungary. The imperial

crown continued some time in the different branches of his family, sometimes in

France, sometimes in Germany, and sometimes in both united under the same

monarch. Lewis IV. the eighth hereditary emperor of the Franks, was a weak

prince, and died in the twentieth year of his age, in 912, without leaving any

issue. These emperors, in imitation of the Lombards, had created several petty

sovereigns in their states, who grew very powerful. These princes declared that

by the death of Lewis IV. the imperial dignity had devolved on the Germanic

people; and excluding Charles the Simple, king of France, the next heir in

blood of the Carlovingian race, elected Conrad I. duke of Franconia; and after

him Henry I. surnamed the Fowler, duke of Saxony, who was succeeded by three

Othos of the same family of Saxony. After St. Henry II. several emperors (the

following Henries, and two Frederics in particular) were of the Franconian

family. Rodolph I. of the house of Austria was chosen in 1273. There have been

four dukes of Bavaria emperors, five of the house of Luxemburg, three of the

old Bohemian royal house, &c. But in 1438, Albert II. duke of Austria and

marquis of Moravia, was raised to that supreme dignity, which from that time

has remained chiefly in that family. The ancient ducal house of Saxony was

descended from Wittekind the Great, the last elected king of the Saxons, who

afterwards sustained a long obstinate war against Pepin and Charlemagne,

submitted to the latter, and being baptized by St. Lullus in 785, was created

by Charlemagne, first duke of Saxony. St. Henry II. was the fifth emperor of

the Saxon race, descended from Wittekind the Great. [back]

Note 2. On the authenticity of this diploma of Henry II. and also of those of

Pepin, Charlemagne, and Otho I. see the Dissertation of the Abbé Cenni,

entitled, Esame de Diplomi d’Ottone è S. Arrigo, printed at Rome in 1754.

That

the see of Rome was possessed of great riches, even during the rage of the

first persecutions, is clear from the acts of universal charity performed by

the popes, mentioned by St. Dionysius of Corinth, and after the persecutions by

St. Basil and St. John Climacus. From the reign of Constantine the Great, many

large possessions were bestowed on the popes for the service of the church.

Cenni (Esame di Diploma di Ludovico Pio) shows in detail from St. Gregory the

Great’s epistles, that the Roman see, in his time, enjoyed very large estates,

with a very ample civil jurisdiction, and a power of punishing delinquents in

them by deputy judges, in Sicily, Calabria, Apulia, Campania, Ravenna, Sabina,

Dalmatia, Illyricum, Sardinia, Corsica, Liguria, the Alpes Cottiæ, and a small

estate in Gaul. Some of these

estates comprised several bishoprics, as appears from St. Gregory, l. 7, ep.

39, Indict. ii.

The

Alpes Cottiæ that belonged to the popes included Genoa and the sea-coast from

that town to the Alps, the boundaries of Gaul, as Thomassin (l. 1, de Discipl.

Eccl. c. 27. n. 17,) takes notice, and as Baronius (ad an. 712, p. 9,) proves

from the testimony of Oldradus, bishop of Milan. And Paul the Deacon writes,

that the Lombards seized the Alpes Cottiæ, which were the estate of the Roman

see. “Patrimonium Alpium Cottiarum quæ quondam ad jus pertinuerant apostolicæ

sedis, sed a Longobardis multo tempore fuerant ablatæ.” (Paul. Diac. l. 6, c.

43.) Father Cajetan, in his Isagoge ad Historiam Siculam, points out at length

the different estates which the Roman see formerly possessed in Sicily. The

popes were charged with a great share of the care of the city and civil

government of Rome. St. Gregory the Great mentions that it was part of their

duty to provide that the city was supplied with corn (l. 5, ep. 40, alias l. 4,

ep. 31, ad Maurit.) and that he was obliged to watch against the stratagems of

the enemies, and the treachery of the Roman generals and governors. (l. 5, ep.

42, alias l. 4, ep. 35.) And he appointed Constantius, a tribune, to be governor

of Naples. (l. 2, ep. 11 alias ep 7.) Anastasius the Librarian testifies that the popes, Sisinnius and Gregory

II. both repaired the walls of Rome, and put the city in a posture of defence.

From

these and other facts Thomassin observes that the popes had then the chief

administration of the city of Rome and of the exarchate, made treaties of

peace, averted wars, defended and recovered cities, and repulsed the enemies.

(Thomass. de Benefic. 3, part. l. 1, c. 29, n. 6.) When the Lombards ravaged and

conquered the country, the emperors continued to oppress the people with

exorbitant taxes, yet being busy at home against the Saracens, refused to

protect the Romans against the barbarians. Whereupon the people of Italy, in the time of Gregory

II. in 715, chose themselves in many places leaders and princes, though that

pope exhorted them every where to remain in their obedience and fidelity to the

empire, as Anastasius the Librarian assures us: “Ne desisterent ab amore et

fide Romani imperii admonebat.”

Leo

the Isaurian and his son Constantine Copronymus persecuted the Catholics; yet

Zachary and Stephen II. paid them all due obedience and respect in matters

relating to the civil government. Leo threatened to destroy the holy images and

profane the relics of the apostles at Rome. At which news the people of Rome

were not to be restrained; but having before received with honour the images of

that emperor, according to custom, they, in a fit of sudden fury, pulled them

down. Pope Stephen II. exhorted the emperor to forbear such sacrileges and

persecutions, and at the same time gave him to understand the danger of

exasperating the populace, though he did what in him lay to prevent by

entreaties both the profanations threatened by the emperor, and also the revolt

of the people: “Tunc projecta laureata tua conculcarunt—Aisque: Romam mittam,

et imaginem S. Petri confringam.—Quòd si quospiam miseris, protestamur tibi,

innocentes sumus a sanguine quem fusuri sunt.” On the sacrileges and cruelties

exercised by the Iconoclasts in the East, see the Bollandists, August ix. To

prevent the like at Rome, some of the Greek historians say that Pope Gregory

II. withdrew himself and all Italy from the obedience of the emperor. But

Theophanes and the other Greeks were in this particular certainly mistaken, as

Thomassin takes notice. And

Natalis Alexander says: (Diss. 1, sæc. 8,) “This most learned pope was not

ignorant of the tradition of the fathers from which he never deviated; for the

fathers always taught that subjects are bound to obey their princes, though

infidels or heretics, in those things which belong to the rights of the

commonwealth.”

The case was, that when the emperors refused to

protect Italy from the barbarians, the popes, in the name of the people, who

looked upon them as their fathers and guardians, and as the head of the

commonwealth, sought protection from the French, as Thomassin observes, (p. 3,

de Benef. l, 1, c. 29.) The continuator of Fredegarius seems to say, that

Gregory III. and the Roman people created Charles Martel Patrician of Rome, by

which title was meant the protection of the church and poor, as De Marca (De

Concordiâ, l. 3, c. 11, n. 6,) and Pagi explain it from Paul the deacon. At

least Pope Stephen II. going into France to invite Pepin into Italy, conferred

on him the title of Patrician, but had not recourse to this expedient till the

Eastern empire had absolutely abandoned Italy to the swords of the Lombards.

Pope Zachary made a peace with Luitprand, king of the Lombards, and afterwards

a truce with king Rachis for twenty years. But that prince putting on the

Benedictin habit, his brother and successor Astulphus broke the treaty. Stephen

II. who succeeded Zachary in 752, sent great presents to Astulphus, begging he

would give peace to the exarchate; but could not be heard, as Anastasius

testifies. Whereupon Stephen went to Paris, and implored the protection of king

Pepin, who sent ambassadors into Lombardy, requiring that Astulphus would

restore what he had taken from the church of Rome, and repair the damages he

had done the Romans. Astulphus refusing to comply with these conditions, Pepin

led an army into Italy, defeated the Lombards, and besieged, and took Astulphus

in Pavia; but generously restored him his kingdom on condition he should live

in amity with the pope. But immediately after Pepin’s departure he perfidiously

took up arms, and in revenge put every thing to fire and sword in the

territories of Rome. This obliged Pepin to return into Italy, and Astulphus was

again beaten and made prisoner in Pavia. Pepin once more restored him his

kingdom, but threatened him with death if he ever again took up arms against

the pope; and he took from him the exarchate of Ravenna, of which the Lombard

had made himself master, and he gave it to the holy see in 755, as Eginhard

relates: “Redditam sibi Ravennam et Pentapolim, et omnem exarchatum ad Ravennam

pertinentem, ad S. Petrum traditit.” Eginhard, ib. Thomassin observes very

justly that Pepin could not give away dominions which belonged to the emperors

of Constantinople; but that they had lost all right to them after they had

suffered them to be conquered by the Lombards, without sending succours during

so many years to defend and protect them. These countries therefore either by

the right of conquest in a just war belonged to Pepin and Charlemagne, who

bestowed them on the popes; or the people became free, and being abandoned to

barbarians had a right to form themselves into a new government. See Thomassin

(p. 3, de Beneficiis, l. 1, c. 29, n. 9).

It is a principle laid down by Puffendorf,

Grotius, Fontanini, and others, demonstrated by the unanimous consent of all

ancients and moderns, and founded upon the law of nations, that he who conquers

a country in a just war, nowise untaken for the former possessors, nor in

alliance with them, is not bound to restore to them what they would not or

could not protect and defend: “Illud extra controversiam est, si jus gentium

respiciamus, quæ hostibus per nos erepta sunt, ea non posse vindicari ab his

qui ante hostes nostros ea possederant et amiserant.” (Grotius, l. 3, de Jure

belli et pacis, c. 6, 38.) The Greeks had by their sloth lost the exarchate of

Ravenna. If Pepin had conquered the Goths in Italy, or the Vandals in Africa

before Justinian had recovered those dominions, who will pretend that he would

have been obliged to restore them to the emperors? Or, if the Britons had

repulsed the Saxons after the Romans had abandoned them to their fury, might

they not have declared themselves a free people? Or, had not the popes and the

Roman people a right, when the Greeks refused to afford them protection, to

seek it from others? They had long in vain demanded it of the emperors of

Constantinople, before they had recourse to the French. Thus Anastasius

testifies that Pope Stephen II. had often in vain implored the succours of Leo

against Astulphus: “Ut juxta quod ei sæpius scripserat, cum exercitu ad tuendas

has Italiæ partes modis omnibus adveniret.” The same Anastasius relates, that

when the ambassadors of the Greek emperor demanded of Pepin the restitution of

the countries he had conquered from the Lombards, that prince answered, that as

he had exposed himself to the dangers of war merely for the protection of St.

Peter’s see, not in favour of any other person, he never would suffer the

apostolic church to be deprived of what he had bestowed on it. Pepin gave to

the holy see the city of Rome and its Campagna; also the exarchate of Ravenna

and Pentapolis, comprising Rimini, Pesaro, Fano, Senigallia, Ancona, Gubbio,

&c. He retained the office of protector and defender of the Roman church

under the title of Patrician. When Desiderius, king of the Lombards, again

ravaged the lands of the church of Rome, Charlemagne marched into Italy,

defeated his forces, and after a long siege took Pavia, and extinguished the

kingdom of the Lombards in 773, on which occasion he caused himself to be

crowned king of Italy, with an iron crown, such as the Goths and Lombards in

that country had used, perhaps as an emblem of strength. Charlemagne confirmed

to Pope Adrian I. at Rome, the donation of his father Pepin. The emperor

Charles the Bald and others ratified and extended the same. Charlemagne having

been crowned emperor of the West at Rome, by Pope Leo III. in 800, Irene who

was then empress of Constantinople, acknowledged him Augustus in 802; as did

her successor the emperor Nicephorus III. The Greeks at the same time ratified

the partition made of the Italian dominions. This point of history has been so

much misrepresented by some moderns, that this note seemed necessary in order

to set it in a true light. See Cenni’s Monumenta Dominationis Pontificiæ, in

4to. Romæ, 1760. Also Orsi’s Dissertation on this subject; Cenni’s Esame di

Diploma. &c. and Jos. Assemani, Hist. Ital. Scriptores, t. 3, c. 5. [back]

Note 3. In the partition of the empire between

Charlemagne and Irene, empress of Constantinople, Apulia and Calabria were assigned

to the Eastern empire, and the rest of Naples to Charlemagne and his

successors. Long before this, in the unhappy reign of the Monothelite emperor

Constans, about the year 660, the Saracens began to infest Sicily, and soon

after became masters of that island, and also of Calabria and some other parts

of Italy. Otho I., surnamed the Great, drove them out of Italy, and laid claim

to Calabria and Apulia by right of conquest. The Greeks soon after yielded up

their pretensions to those provinces by the marriage of Otho II. to Theophania,

daughter of Romanus, emperor of the East, who brought him Apulia and Calabria

for her dowry. Yet the treacherous Greeks joined the Saracens in those

provinces, and again expelled the Germans. But in 1008, Tancred, a noble Norman,

lord of Hauteville, with his twelve sons, and a gallant army of adventurers,