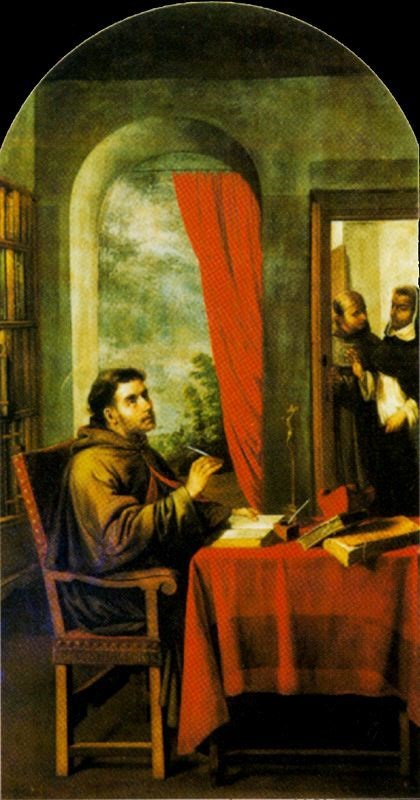

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), The Prayer of St. Bonaventura about the Selection of the New Pope, 1628-1629, 239 x 222, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Saint Bonaventure

Evêque, Docteur de l'Église (+ 1274)

Avec le bienheureux

Jean Duns Scot et saint

Thomas d'Aquin, il est l'un des trois plus célèbres docteurs de la

scolastique. Comme auteur spirituel, il est parmi les grands de tous les temps.

Né à Bagno-Regio en Italie, fils de médecin, Jean Fisanza fut guéri d'une grave

maladie quand sa mère fit un vœu à saint François qui venait d'être canonisé.

On l'envoie étudier les lettres et les arts à l'Université de Paris. C'est là

que, impressionné par l'exemple de l'un de ses maîtres, il entre chez les

frères mineurs, à 22 ans, prenant le nom de Bonaventure. Il gravit sans peine

le cursus des études théologiques et commence à enseigner de 1248 à 1257. En 1257, il est élu ministre général de l'Ordre et se met à

parcourir l'Europe. Il a fort à faire pour maintenir l'unité de cet Ordre

devenu si grand, car il n'est pas simple de faire suivre à 35.000 frères la

règle de vie élaborée par saint François pour quelques disciples. Des

aménagements s'imposent. Mais il sait allier la fermeté dans l'autorité et la

compréhension à l'égard de tous ses frères, tout en demeurant d'une affectueuse

humilité avec tous. En plus de sa charge, il mène de front une vie de

prédicateur, d'enseignant et d'écrivain. Il se voit confier par le Pape des

missions diplomatiques, en particulier pour le rapprochement avec l'Église

grecque. En 1273, le pape Grégoire X le crée cardinal et le charge de préparer

un second concile de Lyon. C'est dans cette ville que frère Bonaventure meurt

en plein concile. Le Pape Sixte-Quint en a fait un docteur de l'Église en 1587.

Le 3 mars 2010, Benoît XVI a tracé un portrait de saint

Bonaventure, un personnage a dit le Pape, "qui m'est particulièrement

cher pour l'avoir étudié dans ma jeunesse". Né vers 1217 à Bagnoregio, au

nord de Rome, et mort en 1274, cet "homme d'action et de contemplation, de

grande piété et de prudence" fut un des principaux promoteurs de l'harmonie

entre foi et culture au XIII siècle. Baptisé sous le nom de Jean, il faillit

mourir jeune d'une grave maladie. Sa mère le recommanda à saint François à

peine canonisé et il guérit, ce qui le marqua pour la vie. Pendant son séjour

d'études théologie à Paris, il se fit franciscain et prit le nom de

Bonaventure. Dès le début de sa vie religieuse il se distingua par sa

connaissance de l'Écriture, de l’œuvre de Pierre Lombard et des principaux

théologiens de son temps.

"La perfection évangélique fut sa réponse lors de sa dispute avec les maîtres séculiers de l'Université de Paris, qui mettaient en doute son droit à enseigner dans les universités"(*) Il démontra comment les franciscains vivaient selon les vœux, en pauvreté, chasteté et obéissance évangélique. "Au-delà de cet épisode historique, la vie, l'enseignement et l’œuvre de Bonaventure demeurent actuels. L'Église est rendue plus belle et lumineuse par la fidélité à leur vocation de ses filles et fils mettant en pratique les préceptes évangéliques, qui sont aussi appelés à témoigner par leur mode de vie que l'Évangile est source de joie et de perfection".

Lorsque Bonaventure fut élu en 1257 supérieur général, les franciscains étaient 30.000, principalement répartis en Europe, certains en Afrique du nord, au proche-orient et en Chine. "Il était nécessaire de consolider cette expansion et surtout lui assurer une unité d'action et d'esprit selon le charisme de saint François. Il existait alors plusieurs interprétations de son message, ce qui risquait de provoquer une fracture interne". Pour préserver l'esprit franciscain authentique, Bonaventure "rassembla de nombreux documents sur le Poverello d'Assise et entendit les témoignages de ceux qui l'avaient connu". Ainsi naquit la Legenda Major, qui est malgré son nom la biographie la plus précise de saint François. Bonaventure y présente le fondateur comme "un chercheur passionné du Christ. Dans un amour mû par l'imitation il s'est complètement conformé au Maître, un idéal que le théologien de Bagnoregio proposa de vivre à tous les disciples de François...un idéal valable pour tout chrétien, aujourd'hui aussi. Jean-Paul II l'a re-proposé pour le troisième millénaire".

Vers la fin de son existence, Bonaventure fut consacré évêque et élevé à la

dignité cardinalice par Grégoire X, qui le chargea de préparer le concile de

Lyon, convoqué pour mettre fin à la division entre Églises latine et grecque.

Mais il ne vit pas la concrétisation de ses efforts et mourut durant le

concile. Benoît XVI a conclu la biographie de ce Docteur de l'Église en

invitant à recueillir l'héritage de saint Bonaventure, qui résumait le sens de

sa vie ainsi: "Sur terre nous pouvons contempler l'immensité divine grâce

au raisonnement et à l'admiration. A l'inverse, au ciel, lorsque nous serons

devenus semblables à Dieu, par la vision et l'extase...nous entrerons dans la

joie de Dieu". (source: VIS 100303-540)

(*) note d'un internaute.

Mémoire de saint Bonaventure, évêque d'Albano et docteur de l'Église, célèbre

par sa doctrine, sa sainteté et ses actions remarquables au service de

l'Église. Ministre général de l'Ordre des Mineurs, il le dirigea avec prudence

dans l'esprit de saint François. Dans ses nombreux écrits, il réunit la plus

grande érudition et la piété la plus ardente. Alors qu'il travaillait avec une

belle ardeur au déroulement du deuxième Concile Œcuménique de Lyon, en 1274, il

mérita de parvenir à la vision bienheureuse de Dieu.

Martyrologe romain

"Pour la recherche spirituelle, la nature ne peut

rien et la méthode peu de choses. Il faut accorder peu à la recherche et

beaucoup à l'action. Peu à la langue et le plus possible à la joie intérieure.

Peu aux discours et aux livres et tout au don de Dieu, c'est-à-dire au

Saint-Esprit. Peu ou rien à la créature et tout à l'Etre créateur: Père, Fils

et Saint-Esprit. "

Saint Bonaventure-Itinéraire de l'esprit vers Dieu.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). Saint

Bonaventure, circa 1620, 140 X 80, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_bonaventure.html

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100303_fr.html

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100310_fr.html

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664).

San Buenaventura recibiendo la visita de Santo Tomas

de Aquino, 1629, 291 X 165, San Francisco el

Grande Basilica

15 juillet

Saint Bonaventure

Jean de Fidanza et de Ritella naît en 1221, à Bagnorea

(entre Viterbe et Orvieto), dans une noble et opulente famille. Enfant, à la

prière de sa mère, il est guéri d’une grave maladie par l’intercession de saint

François. Ayant commencé ses études au couvent de Bagnorea, il les continue à

Paris où il entre au noviciat des Franciscains et prend le nom de Bonaventure.

Il étudie la théologie, l’Écriture sainte et la patristique latine. En 1248, il

débute dans l’enseignement, à l’université de Paris, comme bachelier biblique

et commence à écrire des commentaires des livres saints.

En 1253, il fait un commentaire du « Livre des

Sentences » ; dans de doctes tournois contre les ennemis des ordres

nouveaux, il rompt des lances pour l’honneur de Dame Humilité, reine de tous

les religieux, de Dame Pauvreté, la reine des Mendiants, et de ses sœurs

Chasteté et Obéissance. Au chapitre de Rome, il est élu ministre général des

Mineurs (2 février 1257), charge qu’il occupe jusqu’au 20 mai 1273. Il est

comme le second fondateur de l’ordre qu’il préserve des excès des relâchés

comme de ceux qui visent à un idéal intenable. En 1260, au chapitre de

Narbonne, il promulgue des Constitutions.

Après enquête, il rédige la « Vie »

officielle de saint François où il voit une montée en six étapes marquées par

six apparitions du crucifix et qui s’achève par les stigmates. « Alors est

réalisée ta première vision annonçant que tu serais un chef dans la chevalerie

du Christ, et que tu porterais des armes célestes marquées du signe de la

Croix. Au début de ta conversion, la vision de Jésus crucifié avait transpercé

ton âme d’un glaive de douloureuse compassion ; tu avais entendu une voix

tombant de la croix, comme du trône sublime du Christ et d’un autel

sacré ; tu l’avais affirmé de ta bouche sacrée, et c’est pour nous

maintenant une vérité incontestable. Plus tard, quand tu progressais en

sainteté, le F. Sylvestre vit une croix sortant miraculeusement de ta bouche et

le saint F. Pacifique aperçut deux glaives croisés qui transperçaient ton

corps. Alors que saint Antoine prêchait sur le titre de la croix, l’angélique

Monaldus te vit élevé dans les airs, les bras en croix. Toutes ces merveilles

n’étaient pas des effets de l’imagination, mais une révélation céleste ;

telle est la vérité que nous croyons et affirmons. Enfin, cette vision qui te

montra tout ensemble, vers la fin de ta vie, l’image d’un séraphin sublime et

celle de l’humble Crucifié, qui embrasa ton âme d’amour, imprima les stigmates

dans ton corps et fit de toi un autre ange montant de l’Orient et portant le

signe du Dieu vivant (Apocalypse, VII 2 ), cette vision corrobore la

vérité de celles qui l’ont précédée et reçoit d’elles un surcroît

d’authenticité. Par sept fois, la croix du Christ apparut merveilleusement à

tes yeux ou en ta personne aux diflérentes époques de ta vie. Les six

premières apparitions étaient comme autant de degrés pour arriver à cette

septième où tu trouverais enfin le repos. En effet, la croix du Christ qui

t’est apparue et que tu as embrassée au début de ta conversion, que tu as

portée continuellement dans la suite en toi-même par une vie très parfaite et

que tu as présentée comme un modèle aux autres, nous a appris, avec une

évidence incontestable, que tu étais enfin parvenu au sommet de la perfection

évangélique. Et cette manifestation de la sagesse chrétienne imprimée dans la

poussière de ta chair, nul homme vraiment dévot ne la rejettera. »

Pour que prospèrent tous les bercails de l’ordre

franciscain, il faut l’œil du maître. Bonaventure, qui n’est pas robuste,

s’impose les fatigues d’inspections fréquentes et de prédications nombreuses.

Il parle aux Mineurs - près de cent fois - il parle aux Prêcheurs, aux

bénédictins de Cluny et de Saint-Denis, à des clarisses, à des moniales, à des

béguines et au peuple fidèle. Il s’adresse parfois à la Curie romaine et au

clergé des cathédrales. Des publications ascétiques et mystiques portent au

loin la pensée du grand contemplatif : opuscules sur la légende et l’ascèse

franciscaines, petits traités spirituels. Peu avant 1257, il donne le Breviloquium que

Gerson regardera comme le joyau de la théologie médiévale. En 1259, paraît son

livre médité longuement sur l’Alverne, la plus belle sans doute des œuvres

mystiques du XIII° siècle, l’Itinerarium mentis in Deum qui achemine l’âme

vers Dieu ; l’amour s’y appuie sur la philosophie et la théologie, il

s’élève par six degrés des créatures au Créateur, partant humblement du monde

des sens : « Pour ce passage des créatures à Dieu, la nature ne peut

rien et la science très peu de chose; il faut donner peu au travail de

l’intelligence et beaucoup à l’onction ; peu à la langue et beaucoup à la

joie intérieure ; peu à la parole et aux livres et tout au don de Dieu,

c’est-à-dire au Saint-Esprit ; peu ou rien à la créature et tout au

Créateur, Père, Fils et Saint-Esprit. Interrogez la grâce et non la science ;

le désir et non l’intelligence; les gémissements de la prière et non l’étude

livresque ; l’époux et non le maître ; Dieu et non l’homme ;

l’obscurité et non la clarté ; non la lumière qui brille, mais le feu qui

embrase tout entier et transporte en Dieu. »

Le pape Clément IV veut le nommer archevêque d’York (24 novembre 1265) mais Bonaventure esquive cette gloire. En 1271, après une vacance de trois ans, à Viterbe, il réussit à faire élire pape Grégoire X qui le crée cardinal-évêque d’Albano. Il meurt à Lyon le 14 juillet 1274.

L’itinéraire de l’âme vers Dieu

Le Christ est le chemin et la porte, l'échelle et le

véhicule ; il est le propitiatoire posé sur l'arche de Dieu et le mystère

caché depuis le commencement.

Celui qui tourne résolument et pleinement ses yeux

vers le Christ en le regardant suspendu à la croix, avec foi, espérance et

charité, dévotion, admiration, exultation, reconnaissance, louange et

jubilation, celui-là célèbre la Paque avec lui, c'est-à-dire qu’il se met en

route pour traverser la mer Rouge grâce au bâton de la croix. Quittant

l'Égypte, il entre au désert pour y goûter la manne cachée et reposer avec le

Christ au tombeau, comme mort extérieurement mais expérimentant dans la mesure

où le permet l'état de voyageur ce qui a été dit sur la croix au larron

compagnon du Christ : « Aujourd'hui avec moi tu seras dans le

paradis. »

En cette traversée, si l'on veut être parfait, il

importe de laisser là toute spéculation intellectuelle. Toute la pointe du

désir doit être transportée et transformée en Dieu. Voilà le secret des

secrets, que « personne ne connaît sauf celui qui le

reçoit », que nul ne reçoit sauf celui qui le désire, et que nul ne

désire, sinon celui qui au plus profond est enflammé par l'Esprit Saint que le

Christ a envoyé sur la terre. Et c'est pourquoi l'Apôtre dit que cette

mystérieuse sagesse est révélée par l'Esprit Saint.

Si tu cherches comment cela se produit, interroge la

grâce et non le savoir, ton aspiration profonde et non pas ton intellect, le

gémissement de ta prière et non ta passion pour la lecture ; interroge

l'Époux et non le professeur, Dieu et non l'homme, l'obscurité et non la

clarté ; non point ce qui luit mais le feu qui embrase tout l'être et le

transporte en Dieu avec une onction sublime et un élan plein d'ardeur. Ce feu

est en réalité Dieu lui-même dont « la fournaise est à

Jérusalem. » C'est le Christ qui l'a allumé dans la ferveur brûlante

de sa Passion. Et seul peut le percevoir celui qui dit avec Job : « Mon

âme a choisi le gibet, et mes os, la mort. » Celui qui aime cette

mort de la croix peut voir Dieu ; car elle ne laisse aucun doute, cette

parole de vérité : « L'homme ne peut me voir et vivre. »

Mourons donc, entrons dans l'obscurité, imposons

silence à nos soucis, à nos convoitises et à notre imagination. Passons avec le

Christ crucifié de ce monde au Père. Et quand le Père se sera manifesté, disons

avec Philippe : « Cela nous suffit » ; écoutons

avec Paul : « Ma grâce te suffit » ; exultons en

disant avec David : « Ma chair et mon cœur peuvent défaillir :

le roc de mon cœur et mon héritage, c’est Dieu pour toujours. Béni soit le

Seigneur pour l’éternité, et que tout le peuple réponde : Amen,

amen ! »

St Bonaventure

Transpercez mon âme, très doux Seigneur Jésus, dans

tout ce qu'elle a de plus profond et de plus intime ; transpercez-la du dard

tout suave et tout salutaire de votre amour, de ce dard de la véritable et pure

charité, de cette charité très sainte qu'a eue votre apôtre saint Jean ; en

sorte que mon âme languisse et se fonde sans cesse d'amour et de désir pour

vous seul. Qu'elle soupire après vous et se sente défaillir à la pensée de vos

tabernacles ; qu'elle n'aspire qu'à sa délivrance et à son union avec vous.

Faites que mon âme ait faim de vous qui êtes le pain des anges, aliment des

âmes saintes, notre pain quotidien supersubstantiel ayant en lui toute douceur

et toute suavité délectable. O vous que le désir des anges est de contempler,

puisse mon coeur être toujours affamé et toujours se nourrir de vous, mon âme

être remplie jusque dans ses profondeurs de la suavité de vos délices. Que mon

coeur ait toujours soif de vous, source de vie, source de sagesse et de

science, source d'éternelle lumière, torrent de délices, abondance de la maison

de Dieu. Qu'il n'aspire jamais qu'à vous, ne cherche et ne trouve que

vous ; qu'il tende vers vous et parvienne jusqu'à vous ; qu'il ne pense

qu'à vous, ne parle que de vous, et qu'il accomplisse toutes choses pour l'honneur

et la gloire de votre nom, avec humilité et discernement, avec amour et

plaisir, avec facilité et affection, avec persévérance jusqu'à la fin. Soyez

toujours mon seul espoir et toute ma confiance, mes richesses et mes délices,

mon plaisir et ma joie, mon repos et ma tranquillité, ma paix et ma suavité,

mon parfum et ma douceur, ma nourriture et ma force, mon refuge et mon secours,

ma sagesse et mon partage, mon bien et mon trésor. Qu'en vous seul, mon esprit

et mon coeur soient à jamais fixés, affermis et inébranlablement enracinés.

Amen.

Saint Bonaventure

Afin que l'Eglise fût formée du côté du Christ pendant

son sommeil sur la Croix et afin que fût accomplie la parole de l'Ecriture

: Ils regarderont vers celui qu'ils auront transpercé (Zacharie XII 10),

Dieu a disposé qu'un soldat ouvrît ce côté sacré en le perçant de sa lance et

que, dans cet écoulement de sang et d'eau, fût versé le prix de notre salut :

en jaillissant des profondeurs de ce Coeur, il donnerait aux sacrements de l'Eglise

la vertu de conférer la vie de la grâce et désormais ceux qui vivraient dans le

Christ auraient là une source d'eau vive jaillissant pour la vie éternelle.

Lève-toi donc, âme qui aime le Christ ; ne cesse pas de te tenir attentive ;

applique là ta bouche ; tu y boiras aux sources du Sauveur.

Saint Bonaventure

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/07/15.php

L'Itinéraire de l’esprit jusqu’en Dieu de saint

Bonaventure, fruit d'une extase mystique

Publié le : 4 Février 2021

Avec ce nouveau cycle du blog Ecrits mystiques,

Martine Petrini-Poli nous invite à l'étude de la vie et de l'oeuvre de saint

Bonaventure ( (1217 ou 1221 - 1274). Théologien et philosophe majeur du XIIIe

siècle, contemporain de Thomas d’Aquin, il est devenu supérieur de l’ordre des

Frères Mineurs (franciscains) et créé cardinal-évêque d’Albano à la fin de sa

vie. Sa réflexion philosophique s'inscrit dans le courant de l'augustinisme.

Nous abordons ici l'étude de l'Itinéraire de l'esprit jusqu’en Dieu, écrit en

1259 par saint Bonaventure après avoir expérimenté une extase mystique sur le

mont Alverne, lieu de la vision séraphique de saint François d’Assise.

Itinéraire de l'esprit jusqu’en Dieu (Itinerarium

mentis ad Deum) est un ouvrage de saint Bonaventure, composé en 1259,

après une extase mystique lors d'une promenade sur le mont Alverne,

lieu de la vision séraphique de saint François d’Assise, son maître

spirituel, fondateur de l’ordre des frères mineurs. Rappelons la vision telle

qu’elle est relatée, à la demande du pape Grégoire IX, par le frère mineur

Thomas de Celano, qui composa en 1228, pour la canonisation de François, une

première Vie du saint. Ce texte révèle que François vit dans une vision un

homme, semblable à un séraphin doté de six ailes, qui se tenait au-dessus de

lui, attaché à une croix, les bras étendus et les pieds joints. Deux ailes s'élevaient

au-dessus de sa tête, deux autres restaient déployées pour le vol, les deux

dernières lui voilaient tout le corps.

[…]

Récente édition de L’ITINÉRAIRE DE L’ESPRIT JUSQU’EN

DIEU, de Saint BONAVENTURE (Édition Vrin, Coll. « Translatio/philosophies

médiévales », Paris, 2019), Introduction de Laure Solignac (Institut Catholique,

Paris) et traduction du texte latin par André Ménard, Capucin (Ecole Franciscaine,

Paris).

Plan de l'ouvrage de Saint Bonaventure, qui sera

surnommé Docteur séraphique

• Prologue : plan analytique de l'Itinéraire

À l'exemple de notre père saint François, j'étais tout haletant à la recherche de cette paix, moi pauvre pécheur, indigne successeur du bienheureux père, depuis sa mort septième ministre général de ses frères. C'est alors qu’une inspiration, vers le trente-troisième anniversaire de son trépas, me conduisit à l'écart sur le mont Alverne, comme en un lieu de repos, avec le désir d’y trouver la paix de l'esprit. Là, tandis que je méditais sur les élévations de l'âme vers Dieu, je me remémorai, entre autres choses, le miracle arrivé en ce lieu à saint François lui-même : la vision du séraphin ailé en forme de croix. Or il me sembla aussitôt que cette apparition représentait l’extase du bienheureux père et indiquait l'itinéraire à suivre pour y parvenir. Car par les six ailes du séraphin on peut entendre six élévations diverses où l'âme est illuminée successivement, et qui lui sont comme autant de degrés pour arriver, au milieu des ravissements enseignés par la sagesse chrétienne, à la possession de la paix.

Or, la voie qui y conduit n'est autre qu'un amour très-ardent pour Jésus crucifié ; c'est cet amour qui, après avoir ravi saint Paul jusqu'au troisième ciel, le transformera en son Sauveur, de telle sorte qu'il s'écriait : Je suis attaché à la croix avec Jésus-Christ. Je vis ; mais non, ce n'est plus moi qui vis, c'est Jésus-Christ qui vit en moi (1 Gal., 2). C'est cet amour qui absorba tellement l'âme de François que ses traces se manifestèrent en sa chair lorsque, pendant les deux dernières années de sa vie, il porta en son corps, les stigmates sacrés de la Passion.

Ces six ailes du séraphin sont donc six degrés successifs d'illumination, qui

partent de la créature pour nous conduire jusqu'à Dieu, à qui l'on ne saurait

arriver que par Jésus crucifié.

Les six ailes du séraphin sont refermées sur

lui-même : chaque méditation permet d'en lever une (les six premiers chapitres)

; la dernière méditation est le repos de l'extase mystique.

Contemplation de Dieu à l'extérieur de nous (théologie symbolique) :

• Chapitre I : Degrés d'élévation à Dieu et contemplation de Dieu par ses vestiges dans l’univers

• Chapitre II : Contemplation de Dieu dans ses vestiges à travers le

monde sensible

Contemplation de Dieu à l'intérieur de nous (théologie spéculative) :

• Chapitre III : Contemplation de Dieu par son image gravée dans nos facultés naturelles

• Chapitre IV : Contemplation de Dieu dans son image réformée par les

dons de la grâce

Contemplation de Dieu au-dessus de nous (théologie mystique) :

• Chapitre V : Contemplation de l'unité divine par son premier nom : l’Être

• Chapitre VI : Contemplation de la bienheureuse Trinité dans son nom : le Bien

• Chapitre VII : De l’extase mystique où notre intelligence se tient

en repos, tandis que notre ferveur passe tout entière en Dieu

Martine Petrini-Poli

Witraż z klasztoru franciszkanów w Waszyngtonie DC w Stanach Zjednoczonych, Św. Bonawentura, doktor Kościoła, franciszkanin

Dieu se révèle dans l’Écriture

L’origine de l’Écriture ne se situe pas dans la

recherche humaine, mais dans la divine révélation qui provient du Père des

lumières, de qui toute paternité au ciel et sur terre tire son nom. De lui, par

son Fils Jésus Christ s’écoule en nous l’Esprit Saint. Par l’Esprit Saint,

partageant et distribuant ses dons à chacun de nous selon sa volonté, la foi

nous est donnée, et par la foi, le Christ habite en nos cœurs. Telle est la

connaissance de Jésus Christ de laquelle découlent comme de sa source, la

fermeté et l’intelligence de toute la Sainte Écriture.

Il est donc impossible d’entrer dans la connaissance

de l’Écriture sans d’abord posséder la foi infuse du Christ, comme la lumière,

la porte et aussi le fondement de toute l’Écriture.

L’aboutissement ou le fruit de la Sainte Écriture

n’est pas quelconque, c’est la plénitude de l’éternelle félicité. Car elle est

l’Écriture dans laquelle sont les paroles de la vie éternelle, elle est donc

écrite, non seulement pour que nous croyions, mais aussi pour que nous possédions

la vie éternelle dans laquelle nous verrons, nous aimerons et où nos désirs

seront universellement comblés. Alors, nos désirs étant comblés, nous

connaîtrons vraiment la charité qui surpasse la connaissance et ainsi nous

serons remplis jusqu’à toute la plénitude de Dieu. C’est à cette plénitude que

la divine Écriture s’efforce de nous introduire selon le sens vrai du texte de

l’Apôtre. C’est donc en vue de cette fin, c’est dans cette intention que la

Sainte Écriture doit être étudiée, enseignée et entendue.

St Bonaventure

Saint Bonaventure († 1274), immense théologien et

successeur de saint François à la tête de la famille franciscaine, archevêque

et cardinal, mourut durant le concile de Lyon. / Breviloquium, Paris, Éd.

franciscaines, 1966, p. 85.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/jeudi-15-juillet/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Bleiglasfenster in der Kapelle (Seitenschiff) des

Couvent des Franciscains in Paris (7, rue Marie-Rose im 14. arrondissement),

Darstellung: hl. Bonaventura, links unten Signatur:

""ANDRE-PIERRE"

Vitral São Boaventura / André-Pierre ; foto de

GFreihalter. -- Paris : Capela do Convento dos Fraciscanos, 2000 (foto).

Les précieux conseils de saint Bonaventure pour

trouver sa place dans le monde

Fr.

Michael Rennier - Publié le 14/07/21

Trois recommandations de saint Bonaventure, évêque du

XIIIe siècle et docteur de l’Eglise, fêté ce 15 juillet, pour être en paix avec

ses choix de vie.

Je suis un imposteur. Ou du moins, c’est la

pensée qui m’assaille quand je suis en chaire à la messe et que je donne à une

église remplie de fidèles des paroles à méditer. Pendant que je prêche, je

me demande s’ils savent à quel point j’étais impatient sur le chemin de

l’église, ou à quel point je me suis énervé lorsque j’ai fait brûler ma tartine

au petit déjeuner. Les sentiments qui me viennent sont alors de ne pas

être à ma place, de faire un travail pour lequel je ne suis pas qualifié et que

je prétends simplement être compétent pour le remplir. Qui suis-je pour

penser que je peux être un bon prêtre catholique ?

À d’autres moments, le pendule oscille et j’ai le

problème inverse. La fierté s’installe et je suis convaincu que je suis

très sage, que personne d’autre n’est aussi bon prêtre que moi et que je mérite

peut-être la paroisse la plus grande et la plus belle du diocèse. Encore

une fois, c’est une manière de ne pas être à ma place. Rien n’est jamais

assez bon et peu importe à quel point ma situation actuelle est merveilleuse,

je pense à ce qui aurait pu être autrement et je suis jaloux de ce que les

autres ont.

Ces deux mentalités sont dommageables. Les deux

détruisent le moment présent et représentent un refus de chérir sa place dans

le monde. C’est un manque de confiance.

Quand je lis saint Bonaventure, je me rends compte que

je suis là où je dois être.

C’est un défi majeur de pouvoir accepter qui nous

sommes, où nous sommes et à quel point nous pouvons vraiment être

heureux. C’est tellement irrationnel, de rejeter ce qui est juste devant

nous, de nous aliéner volontairement de nos propres vies, et pourtant nous le

faisons tous. Pensez au parent qui souhaite avoir moins d’enfants ou plus

d’enfants, à l’employé qui se plaint et fait part de son insatisfaction au

travail, au désir permanent d’avoir une maison plus grande, d’une voiture plus

chic, d’un groupe d’amis différent et plus accompli. Nous nous

convainquons que personne ne nous comprend vraiment, personne ne nous apprécie,

et nous sommes à la dérive et flottant dans la vie. Ce sentiment

d’itinérance nous amène à voir le monde et notre place dans celui-ci avec une

vision déformée.

Lire aussi :La « sainte indifférence », la bonne méthode pour

faire un choix

Dans des moments comme celui-ci, nous pouvons nous

tourner vers saint Bonaventure pour obtenir de précieux

conseils. Bonaventure est un moine franciscain qui a vécu au XIIIème

siècle. Il a étudié à la Sorbonne et s’est lié d’amitié avec un certain

nombre de sommités de l’époque, dont saint Thomas d’Aquin et saint

Louis. Il n’était pas aussi intelligent que Thomas d’Aquin mais n’a jamais

été jaloux, insistant pour que son ami reçoive son diplôme avant lui en signe

d’honneur. Il n’était pas aussi riche ou puissant que Louis IX, mais il

n’a jamais souhaité échanger leur place. Après avoir obtenu son diplôme,

le pape Grégoire a essayé de faire de lui un archevêque, mais ce n’était pas le

bon endroit pour Bonaventure et il a refusé. Finalement, il est devenu le

chef de l’Ordre franciscain et parmi ses écrits se trouve la méditation

classique Le voyage de l’esprit vers Dieu.

Bonaventure était un homme qui connaissait sa place

dans le monde. Il était en paix avec sa vie, ses choix et prenait une

grande joie à réaliser sa vocation. Dans Le voyage de l’esprit vers

Dieu, il offre trois conseils utiles sur la façon dont nous pouvons atteindre

cette paix.

1. ENQUÊTER DE MANIÈRE RATIONNELLE

Saint Bonaventure dit : « Dans la première façon de

voir, l’observateur considère les choses en elles-mêmes… » En d’autres termes,

c’est faire une enquête factuelle sur sa vie. Cela peut-être aussi simple

que de se rappeler avoir une famille merveilleuses, des amis formidables et un

travail qui vous plait. Voire d’estimer ne mériter ni plus ni moins d’éloges et

que l’herbe n’est pas toujours plus verte ailleurs. C’est un regard

honnête sur la façon dont tout dans la vie s’emboîte et l’assurance que je suis

au bon endroit.

2. CROIRE FIDÈLEMENT

Ensuite, dit saint Bonaventure, nous considérons le

monde dans son « origine, son développement et sa fin ». Cela nous

rappelle qu’il y a une progression dans nos vies et que nous sommes en

chemin. Il encourage la gratitude pour les bénédictions passées, la

gratitude pour le présent et l’espoir pour l’avenir. Nous devons avoir foi

dans la bonté ultime du monde et dans la direction que prend notre vie.

3. CONTEMPLER INTELLECTUELLEMENT

Maintenant que nous nous sommes rappelés les faits et

que nous avons renouvelé notre sens du mouvement vers un but, saint Bonaventure

invite à discerner les choses qui sont « meilleures et plus

dignes ». Lorsque nous désirons les mauvaises choses pour les

mauvaises raisons, cela provoque l’aliénation. Nous devons trier ce qui

est réellement bon pour nous. C’est une autre façon de voir, de constater

que toute bonne chose a un sens et que dans notre quotidien nous touchons

constamment à l’éternité. Une personne qui recherche ces aspects beaux et

nobles de la vie découvre un sentiment d’appartenance et de foyer, que le monde

est plein de permanence et de bonté.

Lire aussi :La méthode de saint Ignace pour discerner les signes de Dieu

En fin de compte, quand je lis saint Bonaventure, il

m’aide à me rappeler que quoi que nous fassions, cela compte. Nos vies

comptent, notre famille, nos amis, nos pensées, nos émotions, notre travail et

nos loisirs comptent. Il importe que ma tasse de café soit bonne le matin

et que j’aie vu une fleur particulièrement agréable en promenant le chien après

le travail. Ma vie est importante. Votre vie est

importante. Rien n’est parfait, mais quand je lis saint Bonaventure, je me

rends compte que je suis là où je dois être.

Lire aussi :Les cinq étapes indispensables pour bien discerner

Jean Hey (style de) ; Jean Pichore (style de) ; Maître

de la Chronique scandaleuse (style du). Saint Bonaventure.

Miniature. Heures à l'usage de Rome (c. 1510). Tours - BM - ms. 2104

f. 172

1] Apoc. XIV, 6.

[2] Luc. XVII, 34-35.

[3] Isai. VI, 3.

[4] Luc. X, 1.

[5] Gen. XIX, 1.

[6] De ecclesiast. hierarchia, pars I, cap. I, 11.

[7] Johan. XVII, 3.

[8] Ibid. V, 35.

[9] Sap. VII, 27.

[10] Sap. VI, 14.

[11] Ibid. 15.

[12] Bonav. Expositio in Lib. Sapientiœ, VI, 15.

[13] Sap. VIII, 19-20.

[14] Ibid. VII, 8-9.

[15] Prov. VII, 4.

[16] Sap. VIII, 2-3.

[17] Ibid. VII, 10.

[18] Exp. in Lib. Sap. VI, 15.

[19] Sap. VIII, 9.

[20] Expl in Lib. Sap. VIII, 9.

[21] Prov. XV, 15.

[22] Litt. Alexandri IV : De fontibus paradisi flumen egrediens.

[23] Bonav. in II Sent. dist. XXIII, art. 2, qu. 3. ad 7.

[24] Sap. VII, 21.

[25] Ibid. VIII, 4.

[26] Ibid. 7.

[27] Ibid. 8.

[28] Litt. Sixti IV : Superna coelestis patriae civitas ; Sixti V : Triumphantis Hierusalem ; Leonis XIII ; Aeterni Patris.

[29] Exp. In Lib. Sap. VIII, 9, 16.

[30] Antonini Chronic. p. III, tit. XXIV, cap. 8.

[31] H. Sedulius, Histor. seraph.

[32] Eccli. VI, 23.

[33] Bonav. Proœmium in I Sent. qu. 3.

[34] II Sent. dist. XXVIII, qu. 6, ad b.

[35] II Sent. dist. XLIV, qu. 2, ad 6.

[36] IV Sent. dist. XXVIII qu. 6, ad 5.

[37] III Sent. dist. XL, qu. 3, ad 6.

[38] Sap. VIII, 1.

[39] Prov. IX, 9.

[40] Bonav. de eccl. hier. p. II, s. n.

[41] Litt. Superna cœlestis.

[42] Gerson. Epist. cuid. Fratri Minori, Lugdun. an. 4126.

[43] Tract, de examinat, doctrinarum.

[44] Trithem. De scriptor. eccl.

[45] Incend. amoris, Prologus.

[46] Cant. III, 9-10.

[47] Illuminationes Ecclesiœ in Hexaemeron, sermo XXIII.

[48] Illuminationes Ecclesiae in Hexaemeron, Additiones.

[49] II Reg. I, 26.

[50] Matth. XXV, 21.

[51] Bonav. De perfectione vitae, ad Sorores, VIII.

[52] Anselm. Proslogion, XXVI.

[53] Bonav. De reductione artium ad theologiam.

[54] Illuminationes Eccl. I.

[55] De reduct. atrium ad theolog.

[56] Itinerarium mentis in Deum, III.

[57] Psalm. LXXV, 5.

[58] Legenda sancti Francisci, VIII.

[59] Ibid. IX.

[60] Sap. V, 21.

[61] Psalm. XCI, 5.

[62] Bonav. Itinerar. mentis in Deum, I.

[63] Ibid. 11.

[64] Ibid. III.

[65] Ibid. IV.

[66] Ibid. V.

[67] Ibid. VI.

[68] Ibid. VII.

[69] Ibid. Prologus.

[70] Bonav. Itiner. mentis in Deum, I.

[71] Johan. XIV, 6, 8.

[72] Bonav. Intiner. mentis in Deum, VII.

[73] Illuminationes Eccl. II.

[74] Ibid. XIX.

Francisco Herrera the Elder (1576–1656). St Bonaventure Enters the Franciscan Order, 1628, 231 X 215, Museo del Prado : La obra representa al místico italiano San Buenaventura (1218-1274), que llegó a ser obispo de Albano y cardenal de la Iglesia Católica, recibiendo el hábito de fraile de la Orden de San Francisco

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682). Saints Bonaventura and Leander, between circa 1665 and circa 1666, 200 X 176, Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla. La obra representa al místico franciscano San Buenaventura, que fue cardenal y obispo de Albano, junto al prelado San Leandro, que fue arzobispo de Sevilla.

Chiesa di San Bonaventura al Palatino, statua del santo sulla facciata

Saint Bonaventure of

Bagnoregio

Also known as

Seraphic Doctor

of the Church

the Devout Doctor

Doctor Seraphicus

Profile

Healed from

a childhood disease through

the prayers of Saint Francis

of Assisi. Bonaventure joined the Order

of Friars Minor at age 22. Studied theology and philosophy in Paris, France,

and later taught there.

Friend of Saint Thomas

Aquinas. Doctor of Theology.

Friend of King Saint Louis

IX. General of the Franciscan

Order at 35. Bishop of Albano, Italy,

chosen by Pope Gregory

X. Cardinal. Wrote commentaries

on the Scriptures, text-books in theology and philosophy,

and a biography of Saint Francis. Doctor

of the Church. Pope Clement

IV chose him to be Archbishop of York, England,

but Bonaventure begged off, claiming to be inadequate to the office. Spoke at

the Council of Lyons, but died before

its close.

Born

1221 at

Bagnoregio, Tuscany, Italy

15

July 1274 at

Lyon, France of

natural causes

14

April 1482 by Pope Sixtus

IV

Banja

Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Saint

Bonaventure University, New

York

cardinal‘s

hat

cardinal in Franciscan robes,

usually reading or writing

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

—

Holiness of Life, by Saint Bonaventure

Journey of the Mind into God, by Saint Bonaventure

Life of Saint Francis, by Saint Bonaventure

Psaltar of the Blessed Virgin Mary, by Saint Bonaventure

download in EPub format

Saint Bonaventure, the Seraphic Doctor, by Father

Laurence Costelloe

—

Pope Benedict XVI

General

Audience, 3

March 2010

General

Audience, 10

March 2010

General

Audience, 17

March 2010

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

Parish

of Saint Bonaventure, Bagnoregio, Italy

Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy

images

audio

Alleluia Audio Books: Holiness of Life, by Saint

Bonaventure

Life of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, by Saint

Bonaventure (audio book)

video

Holiness of Life, by Saint Bonaventure

(audiobook)

e-books

Life

of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ

Three

Treatises from the Writing of Saint Bonaventure

Virtues

of a Religious Superior

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

notitia in latin

nettsteder i norsk

Readings

A man of eminent learning and eloquence, and of outstanding

holiness, he was known for his kindness, approachableness, gentleness and

compassion. – Pope Gregory

X on hearing of the death of

Bonaventure

Mary seeks for those who approach her devoutly and

with reverence, for such she loves, nourishes, and adopts as her

children. – Saint Bonaventure

When we pray, the voice of the heart must be heard

more than that proceeding from the mouth. – Saint Bonaventure

Christ is both the way and the door. Christ is the

staircase and the vehicle, like the “throne of mercy over the Ark of the

Covenant,” and “the mystery hidden from the ages.” A man should turn his full

attention to this throne of mercy, and should gaze at him hanging on the cross,

full of faith, hope, and charity, devoted, full of wonder and joy, marked by

gratitude, and open to praise and jubilation. Then such a man will make with

Christ a “pasch,” that is, a passing-over. Through the branches of the cross he

will pass over the Red Sea, leaving Egypt and

entering the desert. There he will taste the hidden manna, and rest with Christ

in the sepulcher, as if he were dead to things outside. He will experience, as

much as is possible for one who is still living, what was promised to the thief

who hung beside Christ: “Today you will be with me in paradise.” –

from Journey of the Mind to God by Saint Bonaventure

MLA Citation

“Saint Bonaventure of

Bagnoregio“. CatholicSaints.Info. 30 December 2020. Web. 18 February 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-bonaventure-of-bagnoregio/>

Born in Bagnorea near Viterbo, Italy, in 1221; died at Lyons, France, in 1274; canonized in 1482; declared a Doctor (the "Seraphic Doctor") of the Church in 1587 by Sixtus V; feast day formerly on July 14.

Wounds, our rich inheritance . . .

May these all our spirits fill,

And with love's devotion thrill . . .

Christ, by coward hands betrayed,

Christ, for us a captive made,

Christ upon the bitter tree,

Slain for man--all praise to thee."

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0715.shtml

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Saint Bonaventure

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Today I would like to talk about St Bonaventure of

Bagnoregio. I confide to you that in broaching this subject I feel a certain

nostalgia, for I am thinking back to my research as a young scholar on this

author who was particularly dear to me. My knowledge of him had quite an impact

on my formation. A few months ago, with great joy, I made a pilgrimage

to the place of his birth, Bagnoregio, an Italian town in Lazio that

venerates his memory.

St Bonaventure, in all likelihood born in 1217, died

in 1274. Thus he lived in the 13th century, an epoch in which the Christian

faith which had deeply penetrated the culture and society of Europe inspired

imperishable works in the fields of literature, the visual arts, philosophy and

theology. Among the great Christian figures who contributed to the composition

of this harmony between faith and culture Bonaventure stands out, a man of

action and contemplation, of profound piety and prudent government.

He was called Giovanni di Fidanza. An episode that

occurred when he was still a boy deeply marked his life, as he himself

recounts. He fell seriously ill and even his father, who was a doctor, gave up

all hope of saving him from death. So his mother had recourse to the

intercession of St Francis of Assisi, who had recently been canonized. And

Giovanni recovered.

The figure of the Poverello of Assisi became

even more familiar to him several years later when he was in Paris, where he

had gone to pursue his studies. He had obtained a Master of Arts Diploma, which

we could compare with that of a prestigious secondary school in our time. At

that point, like so many young men in the past and also today, Giovanni asked

himself a crucial question: "What should I do with my life?".

Fascinated by the witness of fervour and evangelical radicalism of the Friars

Minor who had arrived in Paris in 1219, Giovanni knocked at the door of the

Franciscan convent in that city and asked to be admitted to the great family of

St Francis' disciples. Many years later he explained the reasons for his

decision: he recognized Christ's action in St Francis and in the movement he

had founded. Thus he wrote in a letter addressed to another friar: "I confess

before God that the reason which made me love the life of blessed Francis most

is that it resembled the birth and early development of the Church. The Church

began with simple fishermen, and was subsequently enriched by very

distinguished and wise teachers; the religion of Blessed Francis was not

established by the prudence of men but by Christ" (Epistula de tribus

quaestionibus ad magistrum innominatum, in Opere di San Bonaventura.

Introduzione generale, Rome 1990, p. 29).

So it was that in about the year 1243 Giovanni was

clothed in the Franciscan habit and took the name "Bonaventure". He

was immediately sent to study and attended the Faculty of Theology of the

University of Paris where he took a series of very demanding courses. He

obtained the various qualifications required for an academic career earning a

bachelor's degree in Scripture and in the Sentences. Thus Bonaventure

studied profoundly Sacred Scripture, the Sentences of Peter Lombard

the theology manual in that time and the most important theological authors. He

was in contact with the teachers and students from across Europe who converged

in Paris and he developed his own personal thinking and a spiritual sensitivity

of great value with which, in the following years, he was able to infuse his works

and his sermons, thus becoming one of the most important theologians in the

history of the Church. It is important to remember the title of the thesis he

defended in order to qualify to teach theology, the licentia ubique

docendi, as it was then called. His dissertation was entitled Questions

on the knowledge of Christ. This subject reveals the central role that

Christ always played in Bonaventure's life and teaching. We may certainly say

that the whole of his thinking was profoundly Christocentric.

In those years in Paris, Bonaventure's adopted city, a

violent dispute was raging against the Friars Minor of St Francis Assisi and

the Friars Preachers of St Dominic de Guzmán. Their right to teach at the

university was contested and doubt was even being cast upon the authenticity of

their consecrated life. Of course, the changes introduced by the Mendicant

Orders in the way of understanding religious life, of which I have spoken in

previous Catecheses, were so entirely new that not everyone managed to understand

them. Then it should be added, just as sometimes happens even among sincerely

religious people, that human weakness, such as envy and jealousy, came into

play. Although Bonaventure was confronted by the opposition of the other

university masters, he had already begun to teach at the Franciscans' Chair of

theology and, to respond to those who were challenging the Mendicant Orders, he

composed a text entitled Evangelical Perfection. In this work he

shows how the Mendicant Orders, especially the Friars Minor, in practising the

vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, were following the recommendations of

the Gospel itself. Over and above these historical circumstances the teaching

that Bonaventure provides in this work of his and in his life remains every timely:

the Church is made more luminous and beautiful by the fidelity to their

vocation of those sons and daughters of hers who not only put the evangelical

precepts into practice but, by the grace of God, are called to observe their

counsels and thereby, with their poor, chaste and obedient way of life, to

witness to the Gospel as a source of joy and perfection.

The storm blew over, at least for a while, and through

the personal intervention of Pope Alexander IV in 1257, Bonaventure was

officially recognized as a doctor and master of the University of Paris.

However, he was obliged to relinquish this prestigious office because in that

same year the General Chapter of the Order elected him Minister General.

He fulfilled this office for 17 years with wisdom and dedication, visiting the provinces, writing to his brethren, and at times intervening with some severity to eliminate abuses. When Bonaventure began this service, the Order of Friars Minor had experienced an extraordinary expansion: there were more than 30,000 Friars scattered throughout the West with missionaries in North Africa, the Middle East, and even in Peking. It was necessary to consolidate this expansion and especially, to give it unity of action and of spirit in full fidelity to Francis' charism. In fact different ways of interpreting the message of the Saint of Assisi arose among his followers and they ran a real risk of an internal split. To avoid this danger in 1260 the General Chapter of the Order in Narbonne accepted and ratified a text proposed by Bonaventure in which the norms regulating the daily life of the Friars Minor were collected and unified. Bonaventure, however, foresaw that regardless of the wisdom and moderation which inspired the legislative measures they would not suffice to guarantee communion of spirit and hearts. It was necessary to share the same ideals and the same motivations.

For this reason Bonaventure wished to present the authentic charism of Francis,

his life and his teaching. Thus he zealously collected documents concerning

the Poverello and listened attentively to the memories of those who

had actually known Francis. This inspired a historically well founded biography

of the Saint of Assisi, entitled Legenda Maior. It was redrafted more

concisely, hence entitled Legenda minor. Unlike the Italian term the

Latin word does not mean a product of the imagination but, on the contrary,

"Legenda" means an authoritative text, "to be read"

officially. Indeed, the General Chapter of the Friars Minor in 1263, meeting in

Pisa, recognized St Bonaventure's biography as the most faithful portrait of

their Founder and so it became the Saint's official biography.

What image of St Francis emerged from the heart and

pen of his follower and successor, St Bonaventure? The key point: Francis is

an alter Christus, a man who sought Christ passionately. In the love

that impelled Francis to imitate Christ, he was entirely conformed to Christ.

Bonaventure pointed out this living ideal to all Francis' followers. This

ideal, valid for every Christian, yesterday, today and for ever, was also

proposed as a programme for the Church in the Third Millennium by my

Predecessor, Venerable John Paul II. This programme, he wrote in his

Letter Novo

Millennio Ineunte, is centred "in Christ himself, who is to be

known, loved and imitated, so that in him we may live the life of the Trinity,

and with him transform history until its fulfilment in the heavenly

Jerusalem" (n. 29).

In 1273, St Bonaventure experienced another great

change in his life. Pope Gregory X wanted to consecrate him a Bishop and to

appoint him a Cardinal. The Pope also asked him to prepare the Second

Ecumenical Council of Lyons, a most important ecclesial event, for the purpose

of re-establishing communion between the Latin Church and the Greek Church.

Boniface dedicated himself diligently to this task but was unable to see the

conclusion of this ecumenical session because he died before it ended. An

anonymous papal notary composed a eulogy to Bonaventure which gives us a

conclusive portrait of this great Saint and excellent theologian. "A good,

affable, devout and compassionate man, full of virtue, beloved of God and human

beings alike.... God in fact had bestowed upon him such grace that all who saw

him were pervaded by a love that their hearts could not conceal" (cf. J.G.

Bougerol, Bonaventura, in A. Vauchez (edited by), Storia dei

santi e della santità cristiana. Vol. VI. L'epoca del rinnovamento

evangelico, Milan 191, p. 91).

Let us gather the heritage of this holy doctor of the

Church who reminds us of the meaning of our life with the following words:

"On earth... we may contemplate the divine immensity through reasoning and

admiration; in the heavenly homeland, on the other hand, through the vision, when

we are likened to God and through ecstasy... we shall enter into the joy of

God" (La conoscenza di Cristo, q. 6, conclusione, in Opere di

San Bonaventura. Opuscoli Teologici / 1, Rome 1993, p. 187).

To special groups

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

I welcome the English-speaking pilgrims present at

today's Audience, including those from Nigeria, Japan and the United States. To

the pilgrims from Sophia University in Tokyo I offer my prayerful good wishes

that the coming centenary of your University will strengthen your service to

the pursuit of truth and your witness to the harmony of faith and reason. Upon

you and your families I invoke God's abundant Blessings!

Lastly, I greet the young people, the sick and the newlyweds. Dear young people, prepare yourselves to face the important stages of life by founding every project of yours on fidelity to God and to your brothers and sisters. Dear sick people, offer your sufferings to the heavenly Father in union with those of Christ, to contribute to building the Kingdom of God. And you, dear newlyweds, may you be able to edify your family in listening to God in faithful and reciprocal love.

© Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Domenico Vaccaro, Vision of St. Bonaventura, San Lorenzo Maggiore (museum), Napoli

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

To participants in the Pilgrimage of the Don

Carlo Gnocchi Foundation

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

I am glad to receive you in this Basilica and to

address my cordial welcome to each one of you. I greet the pilgrimage promoted

by the Don Carlo Gnocchi Foundation after the recent beatification of

this luminous figure of the Milanese clergy. Dear friends, I am well aware of

the extraordinary activity you carry out in the vast area of health-care

assistance for children in difficulty, for the disabled, for the elderly and

for the terminally ill. Through your projects of solidarity you strive to

perpetuate the praiseworthy work begun by Bl. Carlo Gnocchi, an apostle of

modern times and a genius of Christian charity, who, in taking up the

challenges of his time, devoted himself with every possible

care to little ones who were mutilated, victims of war in whom

he discerned the Face of God. A dynamic and enthusiastic priest and a

perceptive teacher, he lived the Gospel integrally in the different milieus in

which he worked with unflagging zeal and indefatigable apostolic fervour. In

this Year for Priests the Church once again looks to him as a model to imitate.

May his shining example sustain the work of all who are

dedicated to the service of the weakest. May it also inspire in priests the

keen desire to rediscover and reinvigorate awareness of the extraordinary gift

of Grace that the ordained ministry represents for those who have received it,

for the whole Church and for the world.

Let us conclude this short Meeting by singing the prayer of the Pater Noster.

Saint Bonaventure (2)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Last week I spoke of the life and personality of St

Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. This morning I would like to continue my

presentation, reflecting on part of his literary opus and on his doctrine.

As I have already said, among St Bonaventure's various merits was the ability to interpret authentically and faithfully St Francis of Assisi, whom he venerated and studied with deep love.

In a special way, in St Bonaventure's day a trend among the Friars Minor known

as the "Spirituals" held that St Francis had ushered in a totally new

phase in history and that the "eternal Gospel", of which Revelation

speaks, had come to replace the New Testament. This group declared that the

Church had now fulfilled her role in history. They said that she had been

replaced by a charismatic community of free men guided from within by the

Spirit, namely the "Spiritual Franciscans". This group's ideas were

based on the writings of a Cistercian Abbot, Joachim of Fiore, who died in

1202. In his works he affirmed a Trinitarian rhythm in history. He considered

the Old Testament as the age of the Fathers, followed by the time of the Son,

the time of the Church. The third age was to be awaited, that of the Holy

Spirit. The whole of history was thus interpreted as a history of

progress: from the severity of the Old Testament to the relative freedom

of the time of the Son, in the Church, to the full freedom of the Sons of God

in the period of the Holy Spirit. This, finally, was also to be the period of

peace among mankind, of the reconciliation of peoples and of religions. Joachim

of Fiore had awakened the hope that the new age would stem from a new form of

monasticism. Thus it is understandable that a group of Franciscans might have

thought it recognized St Francis of Assisi as the initiator of the new epoch

and his Order as the community of the new period the community of the Age of

the Holy Spirit that left behind the hierarchical Church in order to begin the

new Church of the Spirit, no longer linked to the old structures.

Hence they ran the risk of very seriously

misunderstanding St Francis' message, of his humble fidelity to the Gospel and

to the Church. This error entailed an erroneous vision of Christianity as a

whole.

St Bonaventure, who became Minister General of the

Franciscan Order in 1257, had to confront grave tension in his Order precisely

because of those who supported the above-mentioned trend of the

"Franciscan Spirituals" who followed Joachim of Fiore. To respond to

this group and to restore unity to the Order, St Bonaventure painstakingly

studied the authentic writings of Joachim of Fiore, as well as those attributed

to him and, bearing in mind the need to present the figure and message of his beloved

St Francis correctly, he wanted to set down a correct view of the theology of

history. St Bonaventure actually tackled the problem in his last work, a

collection of conferences for the monks of the studium in Paris. He did not

complete it and it has come down to us through the transcriptions of those who

heard him. It is entitled Hexaëmeron, in other words an allegorical

explanation of the six days of the Creation. The Fathers of the Church

considered the six or seven days of the Creation narrative as a prophecy of the

history of the world, of humanity. For them, the seven days represented seven

periods of history, later also interpreted as seven millennia. With Christ we

should have entered the last, that is, the sixth period of history that was to

be followed by the great sabbath of God. St Bonaventure hypothesizes this

historical interpretation of the account of the days of the Creation, but in a

very free and innovative way. To his mind two phenomena of his time required a

new interpretation of the course of history.

The first: the figure of St Francis, the man

totally united with Christ even to communion with the stigmata, almost an alter

Christus, and, with St Francis, the new community he created, different

from the monasticism known until then. This phenomenon called for a new

interpretation, as an innovation of God which appeared at that moment.

The second: the position of Joachim of Fiore who

announced a new monasticism and a totally new period of history, going beyond

the revelation of the New Testament, demanded a response. As Minister General

of the Franciscan Order, St Bonaventure had immediately realized that with the

spiritualistic conception inspired by Joachim of Fiore, the Order would become

ungovernable and logically move towards anarchy. In his opinion this had two

consequences:

The first, the practical need for structures and for

insertion into the reality of the hierarchical Church, of the real Church,

required a theological foundation. This was partly because the others, those

who followed the spiritualist concept, upheld what seemed to have a theological

foundation.

The second, while taking into account the necessary

realism, made it essential not to lose the newness of the figure of St Francis.

How did St Bonaventure respond to the practical and

theoretical needs? Here I can only provide a very basic summary of his answer

and it is in certain aspects incomplete:

1. St Bonaventure rejected the idea of the Trinitarian

rhythm of history. God is one for all history and is not tritheistic. Hence

history is one, even if it is a journey and, according to St Bonaventure, a

journey of progress.

2. Jesus Christ is God's last word in him God said

all, giving and expressing himself. More than himself, God cannot express or

give. The Holy Spirit is the Spirit of the Father and of the Son. Christ

himself says of the Holy Spirit: "He will bring to your remembrance

all that I have said to you" (Jn 14: 26), and "he will take what

is mine and declare it to you" (Jn 16: 15). Thus there is no loftier Gospel,

there is no other Church to await. Therefore the Order of St Francis too must

fit into this Church, into her faith and into her hierarchical order.

3. This does not mean that the Church is stationary,

fixed in the past, or that there can be no newness within her. "Opera

Christi non deficiunt, sed proficiunt": Christ's works do not

go backwards, they do not fail but progress, the Saint said in his letter De

Tribus Quaestionibus. Thus St Bonaventure explicitly formulates the idea

of progress and this is an innovation in comparison with the Fathers of the

Church and the majority of his contemporaries. For St Bonaventure Christ was no

longer the end of history, as he was for the Fathers of the Church, but rather

its centre; history does not end with Christ but begins a new period. The

following is another consequence: until that moment the idea that the

Fathers of the Church were the absolute summit of theology predominated, all

successive generations could only be their disciples. St Bonaventure also recognized

the Fathers as teachers for ever, but the phenomenon of St Francis assured him

that the riches of Christ's word are inexhaustible and that new light could

also appear to the new generations. The oneness of Christ also guarantees

newness and renewal in all the periods of history.

The Franciscan Order of course as he emphasized

belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ, to the apostolic Church, and cannot be

built on utopian spiritualism. Yet, at the same time, the newness of this Order

in comparison with classical monasticism was valid and St Bonaventure as I said

in my previous Catechesis defended this newness against the attacks of the

secular clergy of Paris: the Franciscans have no fixed monastery, they

may go everywhere to proclaim the Gospel. It was precisely the break with

stability, the characteristic of monasticism, for the sake of a new flexibility

that restored to the Church her missionary dynamism.

At this point it might be useful to say that today too

there are views that see the entire history of the Church in the second

millennium as a gradual decline. Some see this decline as having already begun

immediately after the New Testament. In fact, "Opera Christi non

deficiunt, sed proficiunt": Christ's works do not go backwards

but forwards. What would the Church be without the new spirituality of the

Cistercians, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, the spirituality of St Teresa

of Avila and St John of the Cross and so forth? This affirmation applies today

too: "Opera Christi non deficiunt, sed proficiunt", they

move forward. St Bonaventure teaches us the need for overall, even strict

discernment, sober realism and openness to the newness, which Christ gives his

Church through the Holy Spirit. And while this idea of decline is repeated,

another idea, this "spiritualistic utopianism" is also reiterated.

Indeed, we know that after the Second Vatican Council some were convinced that

everything was new, that there was a different Church, that the pre-Conciliar

Church was finished and that we had another, totally "other" Church

an anarchic utopianism! And thanks be to God the wise helmsmen of the Barque of

St Peter, Pope Paul VI and Pope John Paul II, on the one hand defended the

newness of the Council, and on the other, defended the oneness and continuity

of the Church, which is always a Church of sinners and always a place of grace.

4. In this regard, St Bonaventure, as Minister General

of the Franciscans, took a line of government which showed clearly that the new

Order could not, as a community, live at the same "eschatological

height" as St Francis, in whom he saw the future world anticipated, but

guided at the same time by healthy realism and by spiritual courage he had to

come as close as possible to the maximum realization of the Sermon on the Mount,

which for St Francis was the rule, but nevertheless bearing in mind

the limitations of the human being who is marked by original sin.

Thus we see that for St Bonaventure governing was not

merely action but above all was thinking and praying. At the root of his

government we always find prayer and thought; all his decisions are the result

of reflection, of thought illumined by prayer. His intimate contact with Christ

always accompanied his work as Minister General and therefore he composed a

series of theological and mystical writings that express the soul of his

government. They also manifest his intention of guiding the Order inwardly,

that is, of governing not only by means of commands and structures, but by

guiding and illuminating souls, orienting them to Christ.

I would like to mention only one of these writings,

which are the soul of his government and point out the way to follow, both for

the individual and for the community: the Itinerarium mentis in

Deum, [The Mind's Road to God], which is a "manual" for mystical

contemplation. This book was conceived in a deeply spiritual place: Mount

La Verna, where St Francis had received the stigmata. In the introduction the

author describes the circumstances that gave rise to this writing:

"While I meditated on the possible ascent of the mind to God, amongst

other things there occurred that miracle which happened in the same place to

the blessed Francis himself, namely the vision of the winged Seraph in the form

of a Crucifix. While meditating upon this vision, I immediately saw that it

offered me the ecstatic contemplation of Fr Francis himself as well as the way

that leads to it" (cf. The Mind's Road to God, Prologue, 2,

in Opere di San Bonaventura. Opuscoli Teologici / 1, Rome 1993, p.

499).

The six wings of the Seraph thus became the symbol of

the six stages that lead man progressively from the knowledge of God, through

the observation of the world and creatures and through the exploration of the

soul itself with its faculties, to the satisfying union with the Trinity

through Christ, in imitation of St Francis of Assisi. The last words of St

Bonaventure's Itinerarium, which respond to the question of how it is

possible to reach this mystical communion with God, should be made to sink to

the depths of the heart: "If you should wish to know how these

things come about, (the mystical communion with God) question grace, not

instruction; desire, not intellect; the cry of prayer, not pursuit of study;

the spouse, not the teacher; God, not man; darkness, not clarity; not light,

but the fire that inflames all and transports to God with fullest unction and

burning affection.... Let us then... pass over into darkness; let us impose

silence on cares, concupiscence, and phantasms; let us pass over with the

Crucified Christ from this world to the Father, so that when the Father is

shown to us we may say with Philip, "It is enough for me'" (cf. ibid., VII

6).

Dear friends, let us accept the invitation addressed to us by St Bonaventure, the Seraphic Doctor, and learn at the school of the divine Teacher: let us listen to his word of life and truth that resonates in the depths of our soul. Let us purify our thoughts and actions so that he may dwell within us and that we may understand his divine voice which draws us towards true happiness.

To special groups

I offer a warm welcome to the many school groups

present, including the Bruderhof group from England and the students of St

Michael's Holy Cross Secondary School in Dublin, Ireland. The developments

taking place in Northern Ireland in these days are a promising sign of hope,

and I pray that they will help to consolidate the future of peace desired by

all. Upon the English-speaking pilgrims and visitors I invoke God's abundant

Blessings.

Lastly, I greet the young people, the sick and

the newlyweds. Dear young people, may the Lenten journey we

are taking be an opportunity for authentic conversion that leads you to a

mature faith in Christ. Dear sick people, in taking part lovingly in

the suffering of the incarnate Son of God, may you share from this moment in

the glory and joy of his Resurrection. And may you, dear newlyweds, find

in the covenant which, at the price of his Blood, Christ made with this Church,

the support and model of your marriage contract and your mission at the service

of the Gospel.

* * *

Appeal for aid to Turkey and peace in Nigeria

I am profoundly close to the people hit by the recent

earthquake in Turkey and to their families. I assure each one of my prayers,

while I ask the international community to contribute promptly and generously

to the aid operations.

My heartfelt sympathy also goes to the victims of the atrocious violence that is staining Nigeria with blood and has not even spared defenceless children. Once again, I repeat with anguish that violence does not solve conflicts but only serves to increase their tragic consequences. I appeal to everyone in the country who has civil and religious responsibilities to do their utmost to bring security and peaceful coexistence to the entire population. Lastly, I express my closeness to the Nigerian Pastors and faithful and I pray that with strong, firm hope, they may be authentic witnesses of reconciliation.

© Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100310.html

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Saint Bonaventure (3)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

This morning, continuing last Wednesday's reflection, I would like to study with you some other aspects of the doctrine of St Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. He is an eminent theologian who deserves to be set beside another great thinker, a contemporary of his, St Thomas Aquinas. Both scrutinized the mysteries of Revelation, making the most of the resources of human reason, in the fruitful dialogue between faith and reason that characterized the Christian Middle Ages, making it a time of great intellectual vigour, as well as of faith and ecclesial renewal, which is often not sufficiently emphasized. Other similarities link them: Both Bonaventure, a Franciscan, and Thomas, a Dominican, belonged to the Mendicant Orders which, with their spiritual freshness, as I mentioned in previous Catecheses, renewed the whole Church in the 13th century and attracted many followers. They both served the Church with diligence, passion and love, to the point that they were invited to take part in the Ecumenical Council of Lyons in 1274, the very same year in which they died; Thomas while he was on his way to Lyons, Bonaventure while the Council was taking place.

Even the statues of the two Saints in St Peter's Square are parallel. They

stand right at the beginning of the colonnade, starting from the façade of the

Vatican Basilica; one is on the left wing and the other on the right. Despite

all these aspects, in these two great Saints we can discern two different

approaches to philosophical and theological research which show the originality

and depth of the thinking of each. I would like to point out some of their

differences.

A first difference concerns the concept of theology.

Both doctors wondered whether theology was a practical or a theoretical and

speculative science. St Thomas reflects on two possible contrasting answers.

The first says: theology is a reflection on faith and the purpose of faith is

that the human being become good and live in accordance with God's will. Hence

the aim of theology would be to guide people on the right, good road; thus it

is basically a practical science. The other position says: theology seeks to

know God. We are the work of God; God is above our action. God works right

action in us; so it essentially concerns not our own doing but knowing God, not

our own actions. St Thomas' conclusion is: theology entails both aspects: it is

theoretical, it seeks to know God ever better, and it is practical: it seeks to

orient our life to the good. But there is a primacy of knowledge: above all we

must know God and then continue to act in accordance with God (Summa

Theologiae, 1a, q. 1, art. 4). This primacy of knowledge in comparison

with practice is significant to St Thomas' fundamental orientation.

St Bonaventure's answer is very similar but the stress

he gives is different. St Bonaventure knows the same arguments for both

directions, as does St Thomas, but in answer to the question as to whether

theology was a practical or a theoretical science, St Bonaventure makes a

triple distinction he therefore extends the alternative between the theoretical

(the primacy of knowledge) and the practical (the primacy of practice), adding

a third attitude which he calls "sapiential" and affirming that

wisdom embraces both aspects. And he continues: wisdom seeks contemplation (as

the highest form of knowledge), and has as its intention "ut boni

fiamus" that we become good, especially this: to become good

(cf. Breviloquium, Prologus, 5). He then adds: "faith is in the

intellect, in such a way that it provokes affection. For example: the knowledge

that Christ died "for us' does not remain knowledge but necessarily

becomes affection, love (Proemium in I Sent., q. 3).

His defence of theology is along the same lines,

namely, of the rational and methodical reflection on faith. St Bonaventure

lists several arguments against engaging in theology perhaps also widespread

among a section of the Franciscan friars and also present in our time: that

reason would empty faith, that it would be an aggressive attitude to the word

of God, that we should listen and not analyze the word of God (cf. Letter

of St Francis of Assisi to St Anthony of Padua). The Saint responds to these

arguments against theology that demonstrate the perils that exist in theology

itself saying: it is true that there is an arrogant manner of engaging in

theology, a pride of reason that sets itself above the word of God. Yet real

theology, the rational work of the true and good theology has another origin,

not the pride of reason. One who loves wants to know his beloved better and

better; true theology does not involve reason and its research prompted by

pride, "sed propter amorem eius cui assentit [but is] motivated

by love of the One who gave his consent" (Proemium in I Sent., q. 2)

and wants to be better acquainted with the beloved: this is the fundamental

intention of theology. Thus in the end, for St Bonaventure, the primacy of love

is crucial.

Consequently St Thomas and St Bonaventure define the

human being's final goal, his complete happiness in different ways. For St

Thomas the supreme end, to which our desire is directed is: to see God. In this

simple act of seeing God all problems are solved: we are happy, nothing else is

necessary.

Instead, for St Bonaventure the ultimate destiny of

the human being is to love God, to encounter him and to be united in his and

our love. For him this is the most satisfactory definition of our happiness.

Along these lines we could also say that the loftiest

category for St Thomas is the true, whereas for St Bonaventure it is the good.

It would be mistaken to see a contradiction in these two answers. For both of

them the true is also the good, and the good is also the true; to see God is to

love and to love is to see. Hence it was a question of their different

interpretation of a fundamentally shared vision. Both emphases have given shape

to different traditions and different spiritualities and have thus shown the

fruitfulness of the faith: one, in the diversity of its expressions.

Let us return to St Bonaventure. It is obvious that

the specific emphasis he gave to his theology, of which I have given only one

example, is explained on the basis of the Franciscan charism. The

"Poverello" of Assisi, notwithstanding the intellectual debates of

his time, had shown with his whole life the primacy of love. He was a living

icon of Christ in love with Christ and thus he made the figure of the Lord

present in his time he did not convince his contemporaries with his words but

rather with his life. In all St Bonaventure's works, precisely also his

scientific works, his scholarly works, one sees and finds this Franciscan

inspiration; in other words one notices that his thought starts with his