Bienheureuse

Sára Salkaházi

Religieuse

martyre à Budapest (+ 1944)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/12454/Bienheureuse-Sara-Salkahazi.html

Hongrie

: Béatification d’une religieuse assassinée pour avoir sauvé des Juifs

ROME, Dimanche 17 septembre 2006 (ZENIT.org) – Ce dimanche a été béatifiée à

Budapest, en Hongrie, la religieuse Sára Salkaházi, assassinée pour avoir

protégé des Juifs pendant la deuxième guerre mondiale (cf. Zenit, 27 juin).

SEPTEMBRE 17, 2006 00:00ZENIT STAFFJUSTICE

ET PAIX

La béatification, la première célébrée sur le sol

hongrois depuis 900 ans, s’est déroulée sur le parvis de la basilique de

Saint-Etienne. Le pape était représenté par le cardinal Peter Erdö, primat de

Hongrie, archevêque de Esztergom-Budapest et président de la Conférence

épiscopale de Hongrie.

« Je crois qu’en l’année du renouveau spirituel de la

Nation, le Saint-Père ne pouvait pas faire de plus beau cadeau à l’Eglise, et

même à toute la société hongroise », avait déclaré le cardinal Peter Erdö, lors

de l’annonce de la décision de Benoît XVI de béatifier la religieuse.

Sára

Salkaházi, de l’institut des sœurs de l’Assistance, est née le

11 mai 1899 à Kassa (Kosice, actuellement en Slovaquie) et morte en décembre

1944 à Budapest (Hongrie).

« Elle lutte contre l’idéologie fasciste avec ses

capacités d’écrivain. Au cours de la deuxième guerre mondiale, l’Institut des

Sœurs de l’Assistance accueille les persécutés dans ses maisons, sauvant

environ mille personnes, dont environ cent personnes doivent la vie à Sœur Sára

qui était directrice des Collèges des Filles Ouvrières. Consciente du danger menaçant,

le 14 septembre 1943 elle demande à ses supérieurs l’autorisation de pouvoir

offrir sa vie en sacrifice », écrit le journal catholique hongrois « Magyar

Kurír ».

« L’offrande de sa vie se réalise le 27 décembre 1944

: sœur Sára cachait des persécutés au collège des ouvrières dans la maison, au

n. 3 de la rue Bokréta, à Budapest. C’est là que, ayant été dénoncée, sœur Sára

sera arrêtée et emmenée par les hommes armés du pouvoir fasciste… avec la

catéchiste Vilma Bernovits et quelques persécutés. Ils seront fusillés le soir

même près du Danube gelé, au pied du Pont de la Liberté, à Budapest ».

Sára Salkaházi, blahoslavená 2006, košická rodáčka,

zavraždená v Budapešti kvôli ukrývaniu Židov

w:Sára Salkaházi, beatified 2006, Košice born,

killed in Budapest due to hiding of Jews

Also known as

Sára Schalkház

Profile

Second of three children born

to Leopold and Klotild Salkahaz, hotel

owners. Her father died when

Sara was two. Her brother described her as “a tomboy with a strong will and a

mind of her own; when it came to play she would always join the boys in

their games or tug of war”. She began writing plays

as a teenager,

and at the same time developed a deep prayer life.

She received a degree and taught elementary school for

a year, but gave it up to work as a bookbinder.

She began writing again,

and was active in the Hungarian literary

world. Journalist.

Member of the leadership of the National Christian Socialist Party of

Czechoslovakia, and editor of

the Party newspaper.

Sara was engaged to be married,

but broke it off when she realized a call to a different life. Joined the Sisters

of Social Service in 1929,

making her vows in 1930.

Worked at the Catholic Charities Office in Kosice, Slovakia.

Supervised charity efforts, taught religion, lectured,

continued to write,

and she organized groups of lay

women to help with the Church‘s

social work. Organized a national Catholic Women’s Association. Sara

worked herself to complete exhaustion; seeing this, her supervisors refused to

allow her to take her final vows in the Sisters. However, Sara lived the

rest of her life with self-imposed restrictions as though she had taken

vows.

In 1941 she

was assigned to be national director of the Hungarian Catholic Working

Women’s Movement which had about 10,000 members across the country,

and edited its

magazine. Wrote against Nazism.

She continued her social work with the poor and

the displaced, and started hostels to provide safe housing for working

single women,

and as a place to hide Jews and others being sought by the Nazis.

Started vocational schools,

leadership classes for working lay

people, and retreat centers for them. On 27 December 1944 Nazis surround

the Working Women’s Hostel, 4 Bokréta-Street, Budapest, looking for Jews.

When Sára arrived, she immediately introduced herself as being in charge of the

house. She and five others were taken by the Nazis to

the Danube, stripped naked, and murdered;

the Sisters saved more than 1,000 people.

Born

11 May 1899 in

Kassa, Hungary (modern

Košice, Slovakia)

shot on 27

December 1944 by

members of the Arrow Cross Party on the banks of the River Danube in

Budapest, Hungary

body thrown into the Danube

28 April 2006 by Pope Benedict

XVI

17

September 2006 by Pope Benedict

XVI at Budapest, Hungary

first non-aristocrat Hungarian to

be beatified

Additional Information

other sites in english

Sisters of Social Service, Buffalo, New York

images

sites en français

fonti in italiano

nettsteder i norsk

Readings

Sara Salkahazi heroically exercised her love of

humanity stemming from her Christian faith. This is for what she gave her

life. – Cardinal Peter

Erdo, celebrant of the beatification mass for Blessed Sara, 17 September 2006

I am grateful to you for the love you have given me.

My dear Jesus, I place this love into your hands: keep it chaste and bless it

so that it may always be rooted in You. And increase in me my love for You. I

know that if I love You, I can never get lost. If I want to be yours with all

my heart, you will never let me stray from You. – Blessed Sara

in her spiritual diary

To love, even when it is difficult, even when my heart

has complaints, when, I feel rejected! Yes, this is what God wants! I will try;

I want to start – even if I would fail – until I will be able to love. The Lord

God gives me grace, and I have to work with that grace. – Blessed Sara

in her spiritual diary

I want to follow you wherever you take me, freely,

willingly, joyfully. Break my will! Let your will reign in me! I do not want to

make my own plans. Let your will be done in me and through me. No matter how

hard it might be, I want to love Your will! I want to be one with You, my

Beloved, my Spouse. – Blessed Sara

in her spiritual diary

MLA Citation

“Blessed Sára Salkaházi“. CatholicSaints.Info. 7

February 2019. Web. 27 December 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-sara-salkahazi/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-sara-salkahazi/

Sára

Salkaházi (1899-1944)

Martyr,

Member of the Sisters of Social Service

Teacher, bookbinder, milliner, journalist: this was

the resume of Sára Salkaházi when she applied to join the Sisters of

Social Service, a Hungarian religious society that today is also active in the

United States, Canada, Mexico, Taiwan and the Philippines.

The Sisters of that new congregation, founded in 1923

by Margit Slachta and devoted to charitable, social and women's causes, were

reluctant to accept this chain-smoking, successful woman journalist, and she

was at first turned away from their Motherhouse in Budapest. But 16 years

later, she became the Society's first martyr, at the hands of the Nazis.

Fun-loving and intelligent, Sára was born into a

well-to-do family at Kassa-Kosice, Upper Hungary, now Slovak territory, on 11

May 1899. She studied to become a teacher. In the classroom, she learned

through her students about the social problems of the poor, which she

publicized via newspaper articles.

To widen her horizon and experience first-hand what

discrimination meant, Sára became a bookbinder's apprentice, where she was

given the hardest and dirtiest work. She learned that trade, then went to work

in a millinery shop, all the while continuing to write articles for newspapers.

She became a member of the Christian Socialist Party

and then worked as editor of that party's newspaper, focusing on women's social

problems.

After she had come into contact with the Sisters of

Social Service, Sára felt a strong call to join them. Following her initial

rebuff, she quit smoking - with great difficulty - and was admitted to the

Society at age 30, in 1929. She chose as her motto Isaiah's "Here I am! Send

me!" (Is 6: 8b).

Her first assignment was to her native Kassa (which at

the end of World War I had been incorporated into Czechoslovakia) to organize

the work of Catholic Charities; subsequently, she was sent to Komarom, for the

same task.

In addition, she wrote, edited and published a

Catholic women's journal, managed a religious bookstore, supervised a shelter

for the poor and taught.

The Bishops of Slovakia then entrusted her with the

organization of the National Girls' Movement. She thus began giving leadership

courses and publishing manuals.

In one year alone, she received 15 different

assignments, from cooking to teaching at the Social Training Centre, all of

which exhausted her physically and spiritually. When several novices left the

Society, Sára also considered leaving, especially since her superiors would not

allow her to renew her temporary vows (she was deemed "unworthy"),

nor permit her to wear the habit for a year. These decisions hurt her deeply.

But Sára accepted these hardships and made up her mind

to remain faithful to her calling for the sake of the One who called her. Her

faithfulness paid off as she received permission to renew her vows some time

later.

She wanted to go to the missions, to China or Brazil,

but the outbreak of World War II made it impossible to leave the country. She

worked instead as a social lecturer and administrator in Upper Hungary and

Sub-Carpathia (which had also been part of Hungary until the end of World War

l), and took her final vows in 1940.

As national director of the Catholic Working Girls'

Movement, Sister Sára built the first Hungarian college for working women, near

Lake Balaton. In Budapest, she opened Homes for working girls and organized

training courses.

To protest the rising Nazi ideology Sister Sára changed

her last name to the more Hungarian-sounding "Salkaházi".

As the Hungarian Nazi Party gained strength and also

began to persecute the Jews, the Sisters of Social Service provided safe

havens. Sister Sára opened the Working Girls' Homes to them where, even in the

most stressful situations, she managed to cheer up the anxious and discouraged.

As if her days were not busy enough, she managed to

write a play on the life of St Margaret of Hungary, canonized on 19 November

1943. The first performance, in March 1944, was also the last, since German

troops occupied Hungary that very day and immediately suppressed this religious

production.

The life of St Margaret may have provided the

inspiration for Sister Sára to offer herself as a victim-soul for the safety and

protection of her fellow-Sisters of Social Service. For this, she needed the

permission of her superiors, which was eventually granted. At the time, they

alone knew about her self-offering.

Meanwhile, she kept hiding additional groups of

refugees in the various Girls' Homes, under increasingly dangerous

circumstances. Providing them with food and supplies became more and more

complicated every day, given the system of ration cards and the frequent air

raids. Nevertheless, Sister Sára herself is credited with the saving of 100

Jewish lives, and her Community, with saving 1,000.

The Russian siege of Budapest began on Christmas 1944.

On the morning of 27 December, Sister Sára still delivered a meditation to her

fellow-Sisters. Her topic? Martyrdom! For her, it would become a reality that

very day.

Before noon, Sister Sára and another Sister were

returning on foot from a visit to another Girls' Home. They could already see

in the distance, armed Nazis standing in front of the house. Sister Sára had

time to get away, but she decided that, being the director, her place was at

this Home.

Upon entering the house, she too was accompanied down

into the air raid shelter where the Nazis were already checking the papers of

the 150 residents. About 10 of them were refugees with false papers. Some were

declared suspicious and were to be taken to the ghetto, while those in charge

would have to "give statements at Nazi headquarters before being

released".

As she was led out, Sister Sára managed to step into

the chapel and quickly genuflected before the altar, but her captors dragged

her away. One of the Nazis suggested, "Why don't we finish them off here

in the yard?". But another gestured, "No".

That night, a group of people was driven by agents of

the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross regime to the Danube Embankment. Sister Sára was among

them. As they were lined up, she knelt and made the Sign of the Cross before a

bullet mowed her down. Her stripped corpse and those of her companions were

thrown into the river.

The other Sisters anxiously awaited Sister Sára's

return. A youngster from the neighbourhood brought them news of the shooting

the following day. It seems that the Lord had accepted Sister Sára's sacrifice,

because none of the other Sisters of her Community was harmed.

Every year, on 27 December, the anniversary of her

martyrdom, the Sisters of Social Service hold a candlelight memorial service on

the Danube Embankment for Sister Sára Salkaházi. The voluntary offering of

their first martyr saved not only many persecuted Jews, but also her Religious

Community.

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20060917_salkahazi_en.html

Salkaházi, Sára

Sister Sára

Salkaházi was a nun in the order called the Sisters of Social Service headed by

Margit Slachta*. The “gray sisters” – so called because of

the gray habits they wore – rejected the anti-Jewish edicts of the time, and

placed their institutions at the service of the persecuted Jews. In 1943, the

“Social Sisters” in the city of Kassa / Košice (today Slovakia) hid Mirjam

Grosz (later Shlomi), a Jewish refugee from Slovakia, together with her son.

Later, after the German occupation of Hungary, the order’s house, in which they

and other Jews were hiding, was searched by the Gestapo. Salkaházi managed to

smuggle Grosz and her son out of the building, and traveled with them to

Budapest. This surely saved their lives; three other Jews who were caught in

the basement of the building were shot on the spot. Grosz, equipped with forged

papers, and disguised in a gray nun’s habit, and her son, found shelter with

the Social Sisters of Budapest. A job was arranged for Grosz within the

framework of the order, but as the danger for Jews in the city increased, she

and her son were smuggled back to Kassa. Salkaházi remained in Budapest, where

she was appointed director of the Home for Working Catholic Women, located on

Bokréta Street. During the Arrow Cross period, this house, under Salkaházi’s

direction, was filled with hidden Jewish women and children. Nearly all these

fugitives were put to work at various jobs, equipped with Aryan documents and

were given uniforms of the “gray sisters” so as not to arouse the suspicions of

the Arrow Cross gangs.

In addition to the Catholic girls, the staff and the

hidden Jews, there were also Hungarian soldiers staying in the residence. One

day, a Christian woman who was employed at the residence was warned by

Salkaházi to stay away from the Hungarian soldiers. Angered by what she saw as

an inappropriate intrusion into her personal affairs, the worker denounced

Salkaházi to the Arrow Cross, informing the party thatSalkaházi was hiding Jews

at the residence. On December 27, 1944, the Arrow Cross invaded the residence,

searching for Jews. They checked documents, and arrested a number of Jews whose

papers aroused their suspicions. Together with Salkaházi and Vilma Bernovits,

one of the teachers, these suspects were taken for “interrogation” – in fact,

all of them were shot dead on the banks of the Danube. On February 18, 1969,

Yad Vashem recognized Sára Salkaházi as Righteous Among the Nations Slachta,

Margit Margit Slachta, a devout Roman Catholic, was the first woman ever

elected to the Hungarian parliament. Beginning in 1920 she represented the

United Christian Party (KNEP). Slachta was the founder and director of a

Catholic order known as the Sisters of Social Service, which was active both in

Hungary and in Slovakia. Because of the gray habits worn by the nuns of the

order, they were called “the Gray Sisters.” Slachta was active within the

framework of the order, sponsoring educational programs for Catholic women and

supporting socialist and charitable objectives. In 1941, Slachta was the first

to raise her voice against the Central National Authority for Controlling

Foreigners (KEOKH) expulsions of “stateless” Jews from Hungary to Galicia. In

1942, when the deportations from Slovakia became known, Slachta put the

institutions of the order at the service of the Jewish refugees. One of the

Jewish refugees saved was Miriam Grosz (later Shlomi). In 1943, together with

her young son, Grosz escaped to Kassa / Košice (today Slovakia) and was hidden

in the order’s residence. Her life and the life of her son were saved thanks to

Slachta and Sister Sára Salkaházi*. After the war, Grosz immigrated to Israel.

After the German occupation, and especially during the Arrow Cross period,

Slachta took up residence in the “Social Sisters” center on Thököly Street in

Budapest, an institution that provided a hiding place for many Jews. The center

was located opposite the 14thdistrict Arrow Cross party headquarters, a

building notorious for being a place where Jews were tortured and murdered. At

one point, Arrow Cross gangs invaded the Social Sisters center, and carried out

a brutal hunt for Jews. Slachta herself suffered physical attack at the hands

of one of the Arrow Cross men. She managed to remain calm, however. She called

for help from the Vatican representative and continued to do what she could to

protect the residents of the building by voicing her strenuous opposition to

the search. Hundreds of Jews – both well-known people and everyday citizens –

owed their lives to Margit Slachta. Some received forged papers through her,

and others were given a place to hide. During the democratic period after the

war, Slachta was again appointed to the Hungarian parliament. At the end of

1948 she fled Hungary. She died in 1974. On February 18, 1969, Yad Vashem

recognized Margit Slachta as Righteous Among the Nations.

SOURCE : https://righteous.yadvashem.org/?searchType=righteous_only&language=en&itemId=4017359&ind=NaN

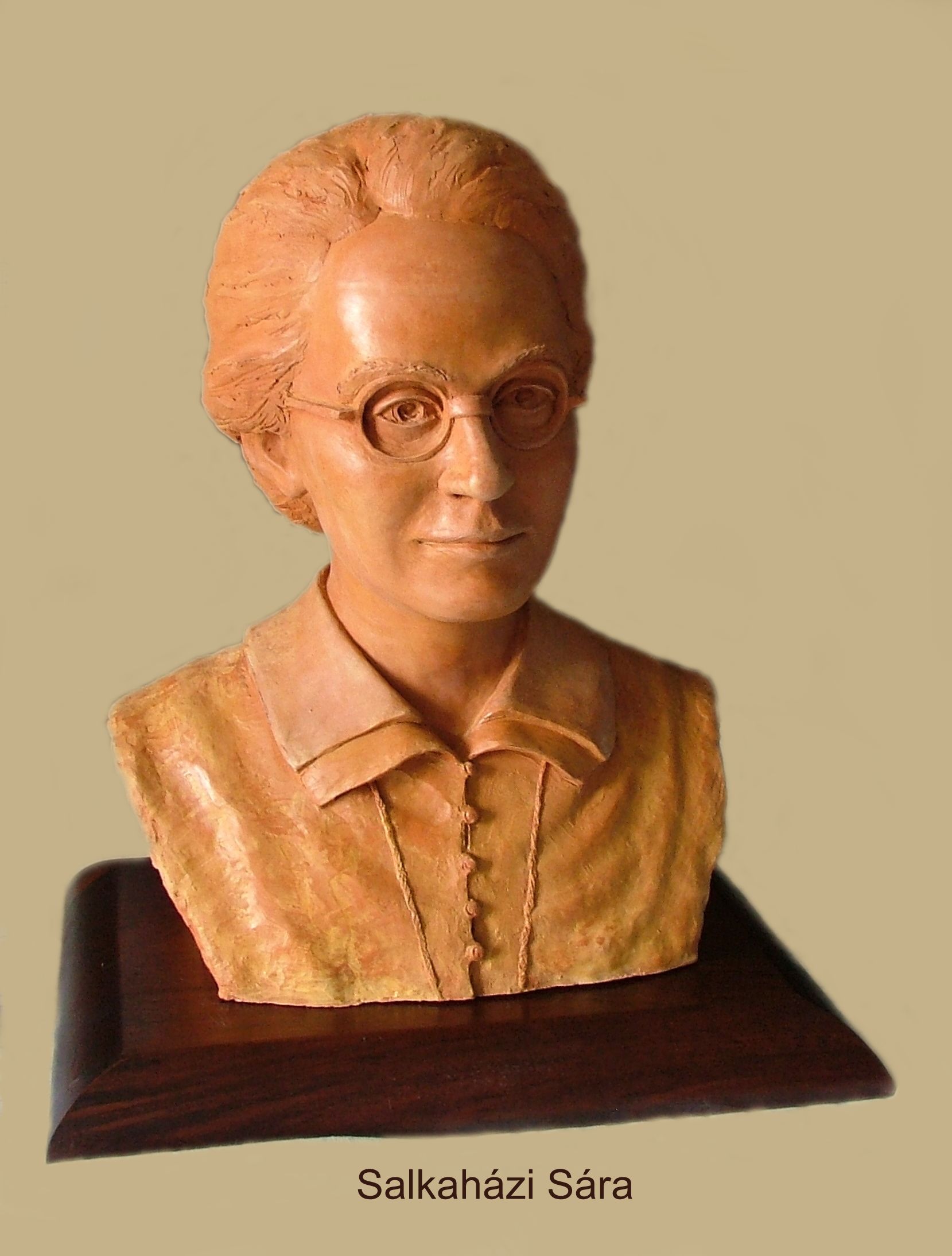

Juha

Richárd: Salkaházi Sára terrakotta mellszobra a debreceni Szent László

Domonkos Plébánián

Beata Sara

Salkahazi Vergine e martire

Kassa-Kosice, Repubblica Slovacca, 11 maggio 1899 -

Budapest, Ungheria, 27 dicembre 1944

Sara Salkahazi, religiosa professa dell’Istituto delle

Suore dell’Assistenza, nacque l’11 maggio 1899 a Kassa-Kosice, in terra allora

ungherese ed oggi in territorio slovacco, e fu uccisa in odio alla sua opera di

difesa degli ebrei il 27 dicembre 1944 a Budapest (Ungheria). La rapidissima

causa di canonizzazione sul suo conto, avviata con il nulla osta della Santa

Sede in data 14 dicembre 1996, ha portato in soli dieci anni al riconoscimento

del suo martirio “in odium fidei” il 28 aprile 2006, passo necessario per la

sua beatificazione senza la necessità di un miracolo avvenuto per sua intercessione.

La cerimonia di beatificazione è stata celebrata a Budapest il 17 settembre

2006.

Ma procediamo con ordine e facciamo un passo indietro

per capire chi era, in realtà, Sára Salkaházi e quali furono i motivi che

portarono al suo arresto. Secondogenita di Leopold e Klotild Stiller, venne

alla luce l’11 maggio 1899 a Kassa – l’odierna cittadina slovacca di Košice –

una delle più eleganti città ungheresi sulle propaggini orientali dei monti

metalliferi di Gömör-Szepes, dove il nonno era proprietario di un rinomato

hotel. Dopo aver conseguito il diploma di maestra presso l’istituto delle Orsoline

di Kassa, visto che con l’avvento del nuovo regime in seguito alla dissoluzione

dell’Impero Austro-Ungarico sancito con la firma del trattato di pace di

Trianon, era praticamente impossibile ottenere un insegnamento perché si

rifiutava di giurare fedeltà al governo cecoslovacco, non si tirò indietro

davanti a nessun tipo di lavoro e per un anno svolse, dapprima le mansioni di

impiegata presso l’ufficio del Grand Hotel Schalkhaz, e poi – considerato lo

stipendio piuttosto esiguo – ai principi di gennaio del 1920, iniziò il suo

apprendistato presso il laboratorio del rilegatore Pintér. Proprio in quegli

anni cominciò a coltivare la passione per la scrittura e, dopo essere riuscita

ad ottenere la tessera di giornalista, a partire dal 1926, divenne redattrice

dell’organo ufficiale del Partito Nazionale dei Socialisti Cristiani

cecoslovacchi NÉP, impegnandosi attivamente come membro della direzione del

partito soprattutto nel settore che si occupava delle questioni sociali che

riguardavano le donne, tanto da diventare ben presto portavoce degli operai e

di tutti coloro che non potevano rivendicare i propri diritti.

Fu proprio in questo ambiente che incominciò a

prendere coscienza dei problemi che affliggevano il mondo del lavoro tanto che,

come vedremo in seguito, saranno al centro anche delle sue principali attività

tra le fila della congregazione religiose nella quale entrerà a far parte. Nel

corso di questi anni, in particolare tra il 1918 ed il 1928, come rileva la sua

amica Elisabetta Forgách, inizia pian piano a percepire la sua vocazione.

Difatti, dopo una fugace storia d’amore con suo vecchio amico, capì che la sua

strada era ben altra. A schiarirle le idee ci pensarono alcune religiose della

Società del Servizio Sociale che ebbe la fortuna di conoscere nel 1928, le

quali la aiutarono a trovare le risposte alle domande che da alcuni anni ormai

tormentavano i suoi pensieri tanto che, dopo aver resistito a lungo, il 6

febbraio 1929 decise di voltare definitivamente pagina e lasciare Kassa per

trasferirsi a Budapest allo scopo di iniziare il suo periodo di noviziato

presso le Suore del Servizio Sociale. Dopo aver preso i primi voti solenni, la

domenica di Pentecoste del 1930, subito si fece notare per il suo carisma,

dedicandosi in diverse attività: dall’insegnamento alla supervisione delle

opere di carità, dall’organizzazione del lavoro della comunità all’attività

giornalistica a favore delle donne cattoliche, raggruppate poi in

un’associazione nazionale col beneplacito della Conferenza Episcopale Slovacca

che, il 3 marzo 1933, affiderà alle Suore Sociali l’organizzazione e il

controllo delle donne, nominando proprio suor Sàra Schalkházi moderatrice

nazionale. Quindi, durante la Pentecoste del 1940, facendo proprio il motto del

profeta Isaia: “Ecce ego, mi mitte” (Eccomi, manda me!), potrà pronunciare

finalmente la sua professione perpetua dedicandosi toto corde al servizio dei

bisognosi.

Nel frattempo, il 30 agosto 1940, subito dopo la firma

del secondo arbitrato di Vienna, si profilava all’orizzonte un altro grave

problema con cui le religiose dovettero confrontarsi: la lotta contro

l’antisemitismo. Il ritorno sotto l’amministrazione militare ungherese della

Transilvania e della Terra dei Szekely aveva determinato, infatti, anche

l’immediato dispiegamento dei militari nazisti in quella zona i quali, l’8

novembre 1940, indussero le autorità governative magiare a decretare

l’espulsione di ben ventiquattro famiglie ebree, costrette ad abbandonare

rapidamente Csíkszereda in poche ore. Due giorni dopo, visto che i Rumeni si

rifiutavano di prenderli in consegna, su ordine del comandante militare i

gendarmi ungheresi, a piccoli gruppi, li condussero oltre il confine russo da

dove, tuttavia, poco dopo alcuni riuscirono a rientrare clandestinamente e ad

avvertire i loro congiunti, i quali subito si rivolsero a suor Margit, come la

signora Schultz Benőné, per rintracciare la figlia, il genero e la nipote. Ad

occuparsi di questa delicata missione fu incaricata proprio suor Sára che,

immediatamente, si recò da Técső a Körösmező e, dopo varie peripezie, riuscì a

parlare con un agente di polizia il quale la rassicurò che li avevano presi in

consegna i Russi e dopo qualche giorno sarebbero stati rimessi in libertà. Il

clima politico non prometteva niente di buono, anzi, diventò sempre più

difficile e pericoloso soprattutto quando, il 19 marzo 1944, di fronte al

rifiuto oppostogli dal reggente Miklós Horthy di appoggiare le potenze

dell’Asse accettando lo stazionamento di truppe tedesche in Ungheria e un

cambiamento di governo più compiacente alla politica nazista, senza pensarci su

due volte, Hitler decretò l’occupazione dell’Ungheria mediante quella che fu

definita in codice Operazione Margarethe.

Poi, dopo aver appreso delle trattative segrete per

siglare l’armistizio con l’Unione Sovietica intavolate dall’Ammiraglio Horthy

il 15 ottobre 1944, ordinò al colonnello Skorzeny di arrestarlo e affidare il

governo magiaro nelle mani più compiacenti del leader filo-tedesco del Partito

delle Croci Frecciate Ferenc Szálasi, il quale subito si fece notare per la sua

crudeltà macchiandosi dei più efferati delitti e per la deportazione di massa

di migliaia di cittadini di religione ebraica verso i lager nazisti. Di lì a

poco, infatti, il Führer nominò l’ambasciatore Edmund Veesenmayer

plenipotenziario del Reich Tedesco in Ungheria e Otto Winkelmann capo delle SS

e della Polizia col preciso intento di presiedere alla soluzione finale della

popolazione ebraica ancora residente in Ungheria. In questo clima arroventato

dall’odio e dalla violenza, con l’incalzare degli eventi, anche sr. Sára

Salkaházi, con sprezzo del pericolo e alto senso di umanità, seguendo l’esempio

della consorella Roza-Katalin Peitl – che aveva salvato la vita a più di 90

persone, tra cui il dr. Szcucs Albertné, Szekely Zoltan, Sperak Jozsefné,

Sandor Palné, Szekely Otto, Lukin Laszloné e Hetenyi Varga Karoly – e della

fondatrice sr. Margit Slachta si prodigò con tutti i mezzi per aiutare i

perseguitati, riuscendo a trarre in salvo circa un centinaio di persone, tra donne

e bambini, che nascose sotto mentite spoglie nella casa madre di via Thökölyne

nell’altra di via Bokréta 3 a Budapest, di cui era direttrice, che aveva preso

in affitto il 31 ottobre 1944 per offrire riparo ad oltre un centinaio di donne

operaie, tra cui c’era anche – travestita da suora – l’ebrea slovacca Mirjam

Grosz (poi Shlomi) insieme al figlio Menachem di appena quattro anni. Dopo

l’avvento al potere del partito dei Croce frecciati anche la villa sul lago

Balaton che ospitava il primo istituto popolare di insegnamento superiore per

operaie, si riempì di profughi offrendo asilo a più di trenta ebrei

perseguitati. Qui, spesso la religiosa si recava per infondere coraggio,

provvedere al loro sostentamento e interporre i suoi buoni uffici con le autorità

al fine di indurle a più miti consigli.

Insieme al vescovo di Győr Vilmos Apor, al cardinale

József Mindszenty, al console svizzero Carl Lutz ed a molti esponenti di spicco

di altre ambasciate presenti a Budapest, ispirati dall’attivismo del diplomatico

svedese Raoul Wallenberg e dall’italiano Giorgio Perlasca – che, il 30 novembre

1944, dopo la partenza del capo della legazione spagnola Angel Sanz-Briz, con

un’astuta messa in scena era riuscito a spacciarsi per incaricato d’affari

spagnolo – fu allestita un’efficiente rete clandestina per sottrarre alla

deportazione verso i lager nazisti decine di migliaia di ebrei allora residenti

a Budapest, grazie ai numerosi documenti di protezione che ognuno di loro

emisero su carta intestata delle rispettive ambasciate e la costituzione di

varie “case protette” che, godendo del diritto di extraterritorialità, si

rivelarono un rifugio sicuro per molti ebrei braccati dai nazisti e dai loro

sodali ungheresi delle Croci Frecciate. In tal senso si mosse abilmente anche

la nunziatura apostolica della S. Sede che, grazie all’abnegazione profusa da

mons. Angelo Rotta e del suo segretario don Gennaro Verolino che, dopo aver

espresso formale protesta al governo ungherese per la deportazione degli ebrei,

oltre alla produzione di numerosi falsi certificati di battesimo, provvide a

distribuire loro, in meno di un anno, tra le 25.000 e le 30.000 “lettere di

protezione”, con le quali riuscirono a salvarsi perché sotto la protezione

diretta dello Stato della Città del Vaticano. Anche la casa madre delle Suore

del Servizio Sociale che sorgeva a Budapest in via Thököly godeva di questo

privilegio. Difatti, un giorno appena si presentarono i nazisti, la superiora

sr. Margit Slachta immediatamente contattò Raoul Wallenberg che, insieme all’ufficiale

dell’ambasciata svedese Valdemar Langlet ed al segretario del nunzio apostolico

don Gennaro Verolino, subito si recarono sul posto riuscendo a sventare ogni

pericolo e impedire la perquisizione.

Tuttavia, sapendo il grave rischio al quale consapevolmente

si era esposta la sua superiora, ospitando, fin dal 1942, all’interno della

casa madre alcuni rifugiati slovacchi, sr. Sára – che in segno di protesta

contro l’influenza nazista aveva fatto magiarizzare il suo cognome Schalkhaz in

Salkaházi – per impedire che i croce frecciati potessero far del male a sr. Margit

e alle altre sue consorelle, il 14 settembre 1943, aveva chiesto ed ottenuto

dai suoi superiori l’autorizzazione ad offrire il sacrificio della propria vita

«nel caso in cui dovesse avvenire la persecuzione della Chiesa e quella della

società e delle suore, […per] risparmiarle dalle minacce e dalle torture». La

cerimonia si svolse solennemente, in gran segreto, nella piccola cappella della

casa madre di via Thököly, dove trovarono rifugio per un certo periodo di

tempo, tra gli altri, anche la scultrice Erzsébet Schaártra, Fanni Gyarmati

moglie del celebre poeta ungherese di origini ebraiche Miklós Radnóti – ucciso

il 9 novembre 1944 dai croci frecciati – Jenő Heltai, Istvánt Rusznyák, l’ottantaquattrenne

attrice Emilia Márkus con suo marito Károly Pulszky, Oszkárt Párdányi, il

socialdemocratico Tibor Vágvölgyi e lo scultore Tibor Vilt. Il pericolo,

tuttavia, era sempre in agguato a causa dei numerosi delatori che per qualche

vile tornaconto personale erano disposti a tutto denunciando le persone che le

suore proteggevano. Difatti, i croce frecciati avendo fiutato qualcosa di

strano negli atteggiamenti di sr. Sára, si misero a tallonarla per controllare

ogni suo spostamento. Ma, grazie al suo savoir-faire la giovane suora per un

bel po’ riuscì a schivare ogni insidia, ingannando la loro vigilanza, anche se

era consapevole che in ogni momento correva il rischio di essere scoperta e

uccisa. Il sinistro presagio si materializzò come accennato in precedenza,

appena due giorni dopo il Natale, la mattina del 27 dicembre 1944, allorché un

drappello di croce frecciati giunsero presso la casa di via Bokréta

nell’intento di acciuffare la direttrice sr. Sára Salkaházi insieme agli ebrei

ivi rifugiati così come era stato loro segnalato. Il turpe misfatto, in realtà,

si consumò il giorno precedente, quando la religiosa aveva confidato ad una

delle due cameriere, la giovane Erzsébet Dömötör, che aveva deciso di

trasferirla in un’altra casa, alle stesse condizioni di servizio perché,

evidentemente, la sua relazione con un soldato ungherese, che alloggiava

insieme ai suoi commilitoni proprio al piano di sopra della loro casa, poteva

pregiudicare l’opera di salvataggio che stava portando a termine nel più stretto

riserbo. La ragazza lì per lì non rispose nulla, ma poi spifferò tutto a

Magdolna Borbàs – che in precedenza aveva fatto parte della direzione di quella

casa – la quale riuscì a persuaderla che a quel punto, per salvaguardare il suo

posto di lavoro, doveva ad ogni costo denunciare la religiosa alle autorità

magiare, rivelando l’opera di salvataggio che svolgeva a beneficio degli ebrei.

Detto fatto. La ragazza non se lo fece ripetere la seconda volta e, per

vendicarsi del torto subito, la mattina del 27 dicembre, si recò presso il

quartier generale delle croci frecciate in Ferenc körút 41, per sporgere

denuncia ai danni della consorella, proprio mentre sr. Sàra, in compagnia di

Edvige Jolsvai si stava recando presso la casa di Liszt Ferenc 6 per predisporre

il suo trasferimento con la direttrice. Quindi, verso l’una, mentre stava

rincasando, da un angolo di via Mester, Edvige Jolsvai scorgendo da lontano una

sentinella dei croce frecciati appostata proprio davanti all’uscio, allarmata

rivolgendosi all’amica esclamò: «non vuoi tagliar la corda? Per poter

continuare a sbrigare le cose. Entrerò io nella casa». Ma sr. Sàra replicò

fermamente: «No, vengo anch’io!». In effetti era accaduto che subito dopo la

denuncia presentata dalla giovane Erzsébet Dömötör, una pattuglia di 7-8 croce

frecciati si era precipitata in via Bokréta allo scopo di perquisire da cima a

fondo l’intero stabile al termine del quale erano riusciti a scovare le donne

ebree nascoste nel rifugio antiaereo. Poi, controllando meticolosamente le carte

dei 150 ospiti, erano riusciti a scoprire perfino che una decina di loro erano

in possesso di documenti falsi. A quel punto la compagna cercò invano di

persuadere la giovane suora a fuggire, ma lei con coraggio si avvicinò al

gendarme il quale con un tono minaccioso la costrinse a scendere nel rifugio

dove il comandante stava procedendo al controllo dei documenti dei rifugiati.

Senza scomporsi più di tanto gli si accostò e, dissimulando una certa

meraviglia, esclamò: «Io sono la responsabile della casa. Mi spiegate per

favore di cosa si tratta?»

Fissando negli occhi la religiosa, incominciando a

sospettare qualcosa, il croce frecciato chiese spiegazioni sulla presenza di

tutti quei documenti ritrovati in una cassa, dopodiché, con un tono

intimidatorio, indicando una donna, aggiunse: «Lei è la direttrice – da quando

questa donna si trova in questa casa?». Suor Sàra obiettò dicendo che avevano

«assunto tutti i lavoratori alla fine di ottobre, così lei è venuta qualche

giorno dopo». Ma il gendarme non abboccò tant’è che subito la interruppe

gridando: «Sta mentendo, questa è una bugia! So tutto di lei!»

Fu a quel punto che la suora capì che per lei non

c’era più nulla da fare perché, ormai, la sua sorte era segnata. Difatti, dopo

un pasto frugale, mentre stava per essere condotta via dalle croci frecciate

insieme alle altre sei donne fermate, all’improvviso rivolta ad uno dei suoi

aguzzini esclamò perentoriamente: «Lasciatemi entrare qui per un breve

istante!». Rapidamente aprì la porta della cappella e prostrata davanti al

tabernacolo, per qualche minuto, si raccolse in una fervida preghiera

stringendo forte il rosario fra le sue mani finché il gendarme spazientito le

intimò: «Basta! Vieni immediatamente! Andiamo, potrai pregare ancora durante la

notte!» e afferratala brutalmente, col pretesto di farle firmare il verbale, e

la condussero presso il loro ufficio in Ferenc körút 41, insieme alla

catechista Vilma Bernovits, Béláné Fischer, Leontint Féderer, Róna Andornét,

Jónás Magdolnát e un certo Bátorinét con il figlio, Istvánnal Bátori, che alla

fine, per fortuna, riuscirono a farla franca dimostrando che non erano di

origine ebraica. Da quel momento in poi Sr. Sàra Salkaházi e le altre persone

arrestate svanirono nel nulla e di loro non si seppe più niente.

Le consorelle attesero invano il suo ritorno recitando

i salmi per tutta la notte, senza sapere che ormai, a loro insaputa, il

sacrificio si era già consumato. Il giorno successivo, infatti, come racconta

nelle sue memorie l’aspirante Leticia, al secolo Ilus Pozsegovits, appresero da

un giovane croce frecciato che abitava nei dintorni che sr. Sàra Salkaházi era

stata giustiziata all’imbrunire insieme agli altri prigionieri ebrei, dopo un

processo sommario, senza neanche una regolare sentenza, aggiungendo che si

dovevano ritenere «contente che non fosse toccato a noi». I particolari

raccapriccianti del martirio di sr. Sára, tuttavia, furono rivelati soltanto

alcuni anni dopo, nel corso del processo che si celebrò a Zugló nel 1967 nei

confronti dei diciannove aderenti al partito dei croce frecciati responsabili

della tortura e del massacro di tutte quelle persone innocenti. In tale

circostanza, infatti, uno degli imputati raccontò, con dovizia di particolari,

che «durante quella notte di fine dicembre, i prigionieri vennero trasportati a

sera tarda davanti all’edificio della dogana centrale e costretti a togliersi i

vestiti di dosso I poveri disgraziati stavano lì, sulla riva del fiume e

sapevano che dovevano morire. Alcuni si lamentavano ed imploravano la grazia.

In quel momento – prima che rimbombassero nell’aria gli spari del plotone

d’esecuzione – una piccola donna dai capelli neri e corti si girò con

un’inspiegabile tranquillità d’animo verso i suoi giustizieri, li guardò per un

istante negli occhi, si inginocchiò e, alzando gli occhi al cielo, si fece un

ampio segno della croce». Fu questo il suo ultimo gesto d’amore anche verso i

suoi carnefici i quali, evidentemente, non ancora paghi dello scempio commesso,

trascinarono i loro corpi ancora caldi sulla riva del Danubio e, senza alcun

ritegno, afferrandoli per i piedi e le braccia, li scaraventarono tra le onde

alte che non li avrebbe mai più restituiti. In virtù di questo esemplare gesto

d’amore, nel 1969 sr. Sára Salkaházi ha ricevuto da Yad Vashem il titolo di

“Giusto tra le Nazioni”, mentre il 17 settembre 2006 è stata innalzata agli

onori degli altari dal Primate d’Ungheria, card. Péter Erdő, in rappresentanza

di Benedetto XVI, proprio nel giorno in cui 78 anni prima aveva mosso il primo

passo sulla strada della sua vocazione.

Autore: Giovanni Preziosi

Fonte: Vatican Insider

I vari regimi totalitari del XX secolo hanno mietuto

nel continente europeo una schiera innumerevole di vittime, tra le quali molti

cristiani che di fronte a tante atrocità non esitarono comunque a testimoniare

la loro fede.

Tra i pochi ungheresi morti in tali circostanze e già

innalzati agli onori degli altari troviamo Sara Salkahazi, nata l’11 maggio

1899 presso la città di Kassa, oggi conosciuta come Kosice in territorio slovacco.

In giovane età fu impegnata in diverse attività: rilegatore, giornalista e

redattore di un giornale. Nel 1930 prese i voti nell’Istituto delle Suore

dell’Assistenza. Il motto della sua vita religiosa fu: “Alleluia! Ecce ego,

mitte me!”, cioè “Alleluia! Eccomi, manda me!”

Durante i mesi finali della seconda guerra mondiale si

prodigò nell’aiuto agli ebrei perseguitati, offrendo loro rifugio in un

edificio di proprietà dell’istituto religioso. Fu però prontamente segnalata

alle autorità da alcune spie ed i membri del partito ungherese filonazista non

esitarono a procedere ad un rastrellamento, fucilando a Budapest sul fiume

Danubio Sara ed altre donne ebree sue protette. Pochi istanti prima Sara fece

il segno della croce, testimoniando così la sua fede cristiana che l’aveva

spinta alla caritatevole accoglienza dei perseguitati di un altra religione. La

religiosa condivise così la medesima sorte che secoli prima era toccata a San

Gerardo, primo vescovo ed apostolo dell’Ungheria. Il suo corpo non fu mai rinvenuto,

forse trasportato più a valle dalle acque del grande fiume.

Suor Sára Salkaházi testimoniò sino all’estremo

sacrificio “il modo in cui un vero cristiano deve comportarsi in situazioni

così tragiche”, sostiene il Cardinale Péter Erdo, Arcivescovo di

Esztergom-Budapest e Primate d’Ungheria, che il 17 settembre 2006 ha proceduto

alla beatificazione della religiosa dinnanzi alla cattedrale di Santo Stefano

nella capitale ungherese. La rapidissima causa di canonizzazione sul suo conto,

avviata con il nulla osta della Santa Sede in data 14 dicembre 1996, ha portato

infatti in soli dieci anni al riconoscimento del suo martirio “in odium fidei”

il 28 aprile 2006, passo necessario per la sua beatificazione senza la

necessità di un miracolo avvenuto per sua intercessione.

Veramente commoventi e degni di nota sono alcuni passi

dell’intervista rilasciata dal primate ungherese al portale cattolico Zenit,

ricchi di testimonianza sulla vita della novella beata. Se ne riportano i passi

più salienti:

“Prima di tutto, Suor Sára è stata una donna molto

moderna: giornalista nella città di Kosice che appartenne all’Ungheria quando

ella è nata e che poi entrò a far parte della Cecoslovacchia; ha scritto per

diversi giornali poi ha scritto anche diversi pezzi di teatro e i suoi scritti

sono pieni di sensibilità umana ma anche pieni del pensiero cristiano.

Attraverso questa sua attività intellettuale si è aperta verso la vocazione ed

ha deciso di dedicare tutta la sua vita al servizio dei prossimi. E’ per questo

che è entrata nella società delle Suore Sociali che era una congregazione nuova

in quel tempo e che si occupava sopratutto del servizio dei poveri e dei

malati.

Per quanto riguarda i poveri Suor Sára ha scoperto l’estrema necessità delle donne nella società di allora, delle donne che erano costrette a lavorare, pur avendo la famiglia da accudire, e che molto spesso vivevano in piena dipendenza e miseria. Ha organizzato anche diverse case per donne in situazione di crisi. Quindi un femminismo cristiano che caratterizzava il pensiero di questa suora e anche la casa a Budapest dove è stata Superiora alla fine della sua vita è stata una casa originalmente per le donne operaie e in questa casa hanno poi nascosto tante donne di origine ebraica. Questa non è stata un’azione isolata della Suor Sára ma anche organizzata centralmente di tutta la sua congregazione. Era un’azione molto ben organizzata e molto rischiosa e per questo Suor Sára in una dedicazione solenne, fatta nella cappella della congregazione qui a Budapest, si è offerta come sacrificio della società per salvare tutti gli altri. Infatti, dopo la sua morte nessun’altra suora è rimasta massacrata, né dai nazisti e né dai comunisti che venivano successivamente. E’ stata una storia veramente commovente già in quell’epoca, ma una storia sulla quale sotto il comunismo si parlava relativamente poco. Inoltre la causa di beatificazione è potuta cominciare soltanto dopo il cambiamento del sistema. La sua vita era inserita armonicamente nella sua congregazione quindi era un servizio sociale della persona umana perché oggi i grandi sistemi di previsione sociale anche di sanità, se funzionano, non riescono a funzionare come una volta anche nel mondo occidentale. Un’altra questione è che le prestazioni che danno questi sistemi sono generalmente prestazioni materiali e non direttamente personali, quindi i sistemi sono spersonalizzati, mentre l’aiuto che cercavano di dare queste suore era sempre un aiuto personalissimo che non calcolava soltanto la quantità degli alimenti distribuiti ma che cercava di mettersi in contatto personale con i bisognosi. Anche questo, secondo me, è un aspetto attualissimo della spiritualità cristiana. Io conosco personalmente ancora delle signore che sono state salvate da Suor Sára oppure dalle altre suore della sua congregazione. Per me la sua figura era sempre una figura dei racconti degli anziani, se vogliamo una leggenda molto realistica, una prova del fatto che i santi non sono delle persone lontane da noi, dalla vita quotidiana, dalle nostre possibilità, ma che sono persone come noi che semplicemente nelle circostanze persino banali della vita quotidiana riescono a seguire con coerenza la volontà di Dio. E questa prontezza della persona riceve poi la benedizione di Dio e in seguito alle nostre azioni semplici accadono dei miracoli, avvenimenti che poi scuotono un’intera generazione e che lasciano il loro ricordo per lunghissimo tempo, anche nella coscienza di una intera città o di un intero popolo”.

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/92766

Salkaházi Sára boldoggá avatása

Den salige Sara Salkaházi (1899-1944)

Minnedag: Den

salige Sara Salkaházi (ung: Sára) ble født den 11. mai 1899 i Kassa i Ungarn, i

dag Kosice i Slovakia. Hun var det andre barnet av Leopold og

Klotild Salkahaz, som eide Hotel Salkahaz i Kosice. Sara ble født i en

praktiserende katolsk familie, og hun var et fromt, men likevel viljesterkt og

begavet barn. Hun mistet sin far

da hun var to år gammel, og hennes mor oppdro henne alene sammen med hennes to

søsken.

Saras litterære

talent ble tydelig tidlig i livet. Hun studerte ved

Ursulasøstrenes institutt i Kosice og tok grad som folkeskolelærer, som var den

høyeste oppnåelige for kvinner der den gangen. Men hun underviste i skolen i

bare ett år. Av politiske årsaker forlot hun læreryrket og lærte seg

bokbinderhåndverket. Der kom hun i kontakt med de fattiges kår, spesielt kvinners,

og de som var tvunget inn i en minoritetssituasjon. Dette fordypet hennes

følsomhet og bevissthet om spørsmål om sosial rettferdighet.

Sara begynte å skrive. Hun ble journalist og deltok

aktivt i det litterære samfunn for den ungarske minoriteten i Slovakia, som

etter Første verdenskrig ble fratatt Ungarn og slått sammen med Bøhmen og

Morava (Tsjekkia) til Tsjekkoslovakia. Hun ble redaktør for den offisielle

avisen til Tsjekkoslovakias nasjonale kristne sosialistparti, og hun var medlem

av partiets ledelse. Hun skrev også romaner, som handlet om de fattiges kår, om

moralske spørsmål som angikk rettferdighet. Men hun var ikke tilfreds og var på

jakt etter sitt sanne kall.

I noen måneder var hun forlovet, men så returnerte hun

ringen, for hun forsto at hennes dypeste lengsler førte henne i en annen

retning. Kristus banket på hennes hjerte og fikk henne til å ville rette all

sin kjærlighet til ham og til tjeneste for de trengende. Men Sara strittet også

mot i flere år, for det betydde at hun måtte oppgi den livsstilen hun hadde

blitt så glad i. Men til slutt ble Kristi kjærlighet den sterkeste.

Hun trådte i 1929 inn i Instituttet «Søstre av

Sosialtjeneste» (Sisters of Social Service – SSS), som var grunnlagt

i 1923 av sr. Margareta Slachta (1884-1974). På 1920-tallet spredte

kongregasjonen seg fra Ungarn til Romania og Slovakia samt til Canada og USA.

Deres oppgave var Kirkens sosiale misjon og hjelp til fattige arbeidere. De

åpnet og drev en skole for å utdanne sosialarbeidere og organiserte og ledet kristne

kvinnebevegelser. Sr. Margareta

var i 1920 den første kvinnen i det ungarske parlamentet.

Sara avla sine

første løfter i pinsen 1930. Hennes motto var «Halleluja», som

viser hennes følelser. Etter løfteavleggelsen startet hun sin sosiale tjeneste.

Hennes første utnevnelse var på det katolske karitative kontoret i Kosice, og

hun arbeidet på mange områder hvor hun kunne bruke sine mange talenter. Hun

ledet karitativt arbeid, ledet et suppekjøkken for 500 fattige barn, ga

religionsundervisning, dannet flere grupper av katolske kvinner og skapte deres

organisasjon, hun ga forelesninger og utga et tidsskrift med tittelen «Katolske

kvinner».

Etter oppdrag fra den katolske bispekonferansen i

Slovakia organiserte hun de ulike kvinnegruppene i en nasjonal katolsk

kvinnebevegelse. Ved siden av alt dette fant hun tid til å skrive. Det er ikke

merkelig at hun ble totalt utslitt. Hennes utbrenthet ble imidlertid

misforstått, hennes overordnede tvilte på hennes kall og nektet henne å fornye

løftene. Dette betydde en betydelig lidelse og ydmykelse for henne, men hun

fortsatte å leve som en SSS-søster uten løfter. Kristi kjærlighet brant inne i

henne og holdt henne trofast. Hun bar disse prøvelsene tålmodig, noe som med

tiden bar vitnesbyrd om ektheten av hennes kall. Denne og andre prøvelser

renset ikke bare hennes kjærlighet til Gud, men også til medlemmene av kommuniteten.

Etter som hennes kjærlighet vokste, våknet det en misjonslengsel i hennes

hjerte. De ungarske benediktinerne i Brasil ba om søstre, og sr. Sara var

villig til å bli sendt, men Andre verdenskrig forpurret planene om å bli sendt

dit.

Men på en måte ble hun en misjonær som sosialarbeider

i et svært fattig område nordøst i Ungarn, som nå er en del av Ukraina. I

pinsen 1940 avla hun sine evige løfter. I 1941 ble hun nasjonal direktør for

den ungarske katolske arbeiderkvinnebevegelsen, med et medlemstall på nesten

10.000. 230 grupper var organisert i femten bispedømmer. Hun forberedte

møtetemaer og sendte dem til gruppelederne, hun skrev artikler i

organisasjonens avis for å tilby fast katolsk orientering for medlemmene som da

var utsatt for nazistisk ideologi. Hun åpnet flere herberger i Budapest for

enslige arbeiderkvinner for å skape et trygt miljø for dem. Hun grunnla også et

kallshus for bevegelsen hvor medlemmene kunne fornye sitt åndelige liv og finne

ny energi. Hun opprettet også en yrkesskole og organiserte kurser for å gi

ledelsestrening og instruksjoner for en holistisk menneskelig utvikling for

arbeidere. Hun gjorde arbeiderkvinner oppmerksomme på deres

menneskerettigheter, men også på deres ansvar. Hun ga muligheter for retretter

og bønn. Sr. Sara elsket og spredte kjærlighet rundt seg.

Det politiske

klimaet etter nazistenes overtok makten i 1938 ble svært vanskelig og farlig. SSS-søstrenes

grunnlegger, sr. Margareta, kjempet mot naziideologien med alle tilgjengelige

midler, og hun involverte kommuniteten for å motstå deres makt. Hun ga sr. Sara

et fremragende eksempel og ga henne tillatelse til å ofre sitt liv for

kommuniteten.

Under Andre verdenskrig reddet SSS-søstrene mer enn

tusen jøder i ulike ungarske byer. I tillegg organiserte de kurs for å avsløre

nazistenes doktrine, og de protesterte mot ungarske lovgiveres maktesløshet i å

hindre den ulovlige beslagleggingen av jødisk eiendom. Sr. Margareta fikk under

krigen en audiens med pave Pius XII (1939-58) for å fortelle om jødenes

tilstand, og hun skrev til prester over hele Ungarn for å hjelpe jødene.

Da tyskerne okkuperte Ungarn den 19. mars 1944, åpnet

sr. Margaret kongregasjonens hus for å gi ly til jøder. Sr. Sara deltok aktivt

i dette arbeidet. Hun åpnet et av herbergene samt bevegelsens kallshus for de

forfulgte. Sr. Sara hjalp til med å skjule hundrevis av jøder, inkludert mange

kvinner og barn, i krigens siste måneder.

Men en av arbeiderkvinnene rapporterte henne til

myndighetene for å gi ly til jøder, og soldater fra det herskende fascistiske

Pilkorspartiet kom for å arrestere henne den 27. desember 1944. Hun gikk da til

kapellet og prostrerte seg foran sakramentet. Deretter reiste hun seg og fulgte

soldatene sammen med en gruppe hun forsøkte å skjule og en kateket som hjalp

henne. De vendte aldri tilbake.

Flere år senere ble det holdt en rettssak, hvor en

soldat tilsto hva som hadde skjedd. Sr. Sara og hennes gruppe ble drevet til

breddene av elva Donau i Budapest, avkledd, skutt og kastet i Donau den 27.

desember 1944. Deres legemer ble aldri funnet igjen.

Etter krigen ble sr. Margareta igjen innvalgt i

parlamentet, og sammen med kardinal Mindszenty var hun en del av motstanden mot

kommunismen. I 1949 måtte hun av politiske årsaker flytte til Buffalo i USA, og

der sluttet hun seg til SSS-søstre som hadde kommet fra Ungarn på 1920-tallet

og i 1947. Ordenen ble oppløst i Øst-Europa i 1950, og sr. Margareta flyttet

administrasjonen av Selskapet til Buffalo. Etter den ungarske revolusjonen i

1956 kom en gruppe noviser fra Budapest til Buffalo.

«Føderasjonen av Søstre av Sosialtjeneste» ble

etablert i 1972. Den består av tre autonome grener: SSS i California, SSS i

Canada og SSS i Ungarn/Buffalo, nå med hovedkvarter i Budapest. Medlemmer arbeider

i dag i USA, Canada, Cuba og Puerto Rico. Sr. Margareta Slachta ble den 1. juni

1986 æret av Yad Vashem for å ha hjulpet jøder i Ungarn.

Sr. Saras saligkåringsprosess ble åpnet i 1997. Den

28. april 2006 undertegnet pave Benedikt XVI dekretet fra Helligkåringskongregasjonen

som anerkjente hennes død som et martyrium in odium fidei – «av hat

til troen», og hun fikk dermed tittelen Venerabilis, «Ærverdig». Som

martyr er det ikke krav om noe mirakel for å bli saligkåret.

Fra saligkåringen i Budapest

Hun ble saligkåret den 17. september 2006 av

pave Benedikt XVI på plassen utenfor St. Stefansbasilikaen i Budapest. Som

vanlig under dette pontifikatet ble seremonien ikke ledet av paven selv, men av

hans representant, i dette tilfelle kardinal Peter Erdö,

erkebiskop av Esztergom-Budapest og president for den ungarske

bispekonferansen. De overlevende fra gruppen på 140 som Sara hjalp til med å

redde var blant dem som var til stede ved seremonien. Dette er den første

salig- eller helligkåring som skjer i Ungarn siden helligkåringen i 1083 av den

hellige kong Stefan

I (Szent István), hans hellige sønn Emerik (Szent

Imre) og den hellige Gerhard Sagredo av

Csanád (Szent Gellért).

Vanligvis er pavens legat ved saligkåringer prefekten

for Helligkåringskongregasjonen i Vatikanet, kardinal José Saraiva Martins CMF,

men han presiderte samme dag over saligkåringen av Moses Tovini i

Brescia i Italia.

Kilder:

santiebeati.it, sistersofsocialservice.ca, sistersofsocialservicebuffalo.org,

salkahazisara.com, the-tidings.com, holycross.edu - Kompilasjon og

oversettelse: p. Per Einar Odden -

Sist oppdatert: 2006-09-25 22:13

SOURCE : http://www.katolsk.no/biografier/historisk/ssalkaha