Statue

de l'apôtre saint Pierre à la basilique Saint-Jean-de-Latran à Rome.

Saint Pierre

Pape (1 er) - apôtre (+ 64)

Saint Pierre et saint Paul: On ne peut les séparer. Ils sont les deux piliers de l'Église et jamais la Tradition ne les a fêtés l'un sans l'autre. L'Église romaine, c'est l'Église de Pierre et de Paul, l'Église des témoins directs qui ont partagé la vie du Seigneur. Pierre était galiléen, reconnu par son accent, pêcheur installé à Capharnaüm au bord du lac de Tibériade. Paul était un juif de la diaspora, de Tarse en Asie Mineure, mais pharisien et, ce qui est le plus original, citoyen romain. Tous deux verront leur vie bouleversée par l'irruption d'un homme qui leur dit: "Suis-moi. Tu t'appelleras Pierre." ou "Saul, pourquoi me persécutes-tu? Simon devenu Pierre laisse ses filets et sa femme pour suivre le rabbi. Saul, devenu Paul se met à la disposition des apôtres. Pierre reçoit de l'Esprit-Saint la révélation du mystère caché depuis la fondation du monde: "Tu es le Christ, le Fils du Dieu vivant." Paul, ravi jusqu'au ciel, entend des paroles qu'il n'est pas possible de redire avec des paroles humaines. Pierre renie quand son maître est arrêté, mais il revient: "Seigneur, tu sais tout, tu sais bien que je t'aime." Paul, persécuteur des premiers chrétiens, se donne au Christ: "Ce n'est plus moi qui vis, c'est le Christ qui vit en moi." Pierre reçoit la charge de paître le troupeau de l'Église: "Tu es Pierre et sur cette pierre je bâtirai mon Église." Paul devient l'apôtre des païens. Pour le Maître, Pierre mourra crucifié et Paul décapité.

Solennité des saints apôtres Pierre et Paul. Simon, fils de Yonas et frère d’André, fut le premier parmi les disciples de Jésus à confesser (*) le Christ, Fils du Dieu vivant, et Jésus lui donna le nom de Pierre. Paul, Apôtre des nations, annonça aux Juifs et aux Grecs le Christ crucifié. Tous deux annoncèrent l’Évangile du Christ avec foi et amour et subirent le martyre sous l’empereur Néron; le premier, comme le rapporte la tradition, fut crucifié la tête en bas et inhumé au Vatican, près de la voie Triomphale, en 64; le second eut la tête tranchée et fut enseveli sur la voie d’Ostie, en 67. Le monde entier célèbre en ce jour le triomphe de l’un et de l’autre avec un honneur égal et une même vénération.

(*) c'est-à-dire 'proclamer sa foi' (voir le glossaire)

Martyrologe romain

En un seul jour, nous fêtons la passion des deux Apôtres, mais ces deux ne font qu’un. Pierre a précédé, Paul a suivi. Aimons donc leur foi, leur existence, leurs travaux, leurs souffrances ! Aimons les objets de leur confession et de leur prédication !

Saint Augustin - Sermon pour la fête des saints Pierre et Paul

SAINT PIERRE, APÔTRE (1)

Bild aus: Psalterium Feriatum, Hildesheim (?), bald nach 1235. Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart, Cod. Don. 309

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 24 mai 2006

Pierre, l'Apôtre

Chers frères et soeurs,

Dans ces catéchèses, nous méditons sur l'Eglise. Nous

avons dit que l'Eglise vit dans les personnes et, dans la dernière catéchèse,

nous avons donc commencé à méditer sur les figures de chaque apôtre, en

commençant par saint Pierre. Nous avons vu deux étapes décisives de sa

vie: l'appel sur les rives du Lac de Galilée, puis la confession de

foi: "Tu es le Christ, le Messie". Une confession, avons-nous

dit, encore insuffisante, à ses débuts et qui est toutefois ouverte. Saint

Pierre se place sur un chemin de "sequela". Ainsi, cette confession

initiale contient déjà en elle, comme en germe, la future foi de l'Eglise.

Aujourd'hui, nous voulons considérer deux autres événements importants de la

vie de saint Pierre: la multiplication des pains - nous avons entendu

dans le passage qui vient d'être lu la question du Seigneur et la réponse de

Pierre - et ensuite le Seigneur qui appelle Pierre à être pasteur de l'Eglise

universelle.

Commençons par l'épisode de la multiplication des

pains. Vous savez que la foule avait écouté le Seigneur pendant des heures. A

la fin, Jésus dit: ils sont fatigués, ils ont faim, nous devons donner à

manger à ces gens. Les apôtres demandent: mais comment? Et André, le

frère de Pierre, attire l'attention de Jésus sur un jeune garçon, qui portait

avec lui cinq pains et deux poissons. Mais cela est bien peu pour tant de

personnes, disent les Apôtres. Alors le Seigneur fait asseoir la foule et

distribuer ces cinq pains et ces deux poissons. Et tous se rassasient. Le

Seigneur charge même les Apôtres, et parmi eux Pierre, de recueillir les restes

abondants: douze paniers de pain (cf. Jn 6, 12, 13). Par la

suite, la foule, voyant ce miracle, - qui semble être le renouvellement, tant

attendu, d'une nouvelle "manne", du don du pain du ciel - veut en

faire son roi. Mais Jésus n'accepte pas et se retire sur la montagne, pour

prier tout seul. Le jour suivant, sur l'autre rive du lac, dans la synagogue de

Capharnaüm, Jésus interpréta le miracle, - non dans le

sens d'une royauté sur Israël avec un pouvoir de ce monde de la façon espérée

par la foule, mais dans le sens d'un don de soi: "Le pain que je

donnerai, c'est ma chair pour la vie du monde" (Jn 6, 51). Jésus

annonce la croix, et avec la croix, la véritable multiplication des pains, le

pain eucharistique - sa façon absolument nouvelle d'être roi, une façon

totalement contraire aux attentes des gens.

Nous pouvons comprendre que ces paroles du Maître -

qui ne veut pas accomplir chaque jour une multiplication des pains, qui ne veut

pas offrir à Israël un pouvoir de ce monde, - apparaissent véritablement

difficiles, et même inacceptables pour les gens. "Il donne sa

chair": qu'est-ce que cela signifie? Pour les disciples aussi, ce

que Jésus dit à ce moment-là apparaît inacceptable. C'était et c'est pour notre

coeur, pour notre mentalité, un discours "dur", qui met la foi à

l'épreuve (cf. Jn 6, 60). Beaucoup de disciples se rétractèrent. Ils

voulaient quelqu'un qui renouvelle réellement l'Etat d'Israël, de son peuple,

et non pas quelqu'un qui disait: "Je donne ma chair". Nous

pouvons imaginer que les paroles de Jésus étaient difficiles également pour

Pierre, qui à Césarée de Philippe, s'était opposé à la prophétie de la croix.

Et toutefois, lorsque Jésus demanda aux Douze: "Voulez-vous partir,

vous aussi?", Pierre réagit avec l'élan de

son coeur généreux, guidé par l'Esprit Saint. Au nom de tous, il

répondit par les paroles immortelles, qui sont aussi les nôtres:

"Seigneur, vers qui pourrions-nous aller? Tu as les paroles de la

vie éternelle. Quant à nous, nous croyons, et nous

savons que tu es le Saint, le Saint de Dieu" (cf. Jn 6,

66-69).

Ici, comme à Césarée, Pierre entame à travers ses

paroles la confession de foi christologique de l'Eglise et devient également la

voix des autres Apôtres et de nous, croyants de tous les temps. Cela ne veut

pas dire qu'il avait déjà compris le mystère du Christ dans toute sa

profondeur. Sa foi était encore à ses débuts, une foi en marche; il ne serait

arrivé à la véritable plénitude qu'à travers l'expérience des événements

pascals. Mais toutefois, il s'agissait déjà de foi, une foi ouverte aux

réalités plus grandes - ouverte surtout parce que ce n'était pas une foi en

quelque chose, c'était une foi en Quelqu'un: en Lui, le Christ. Ainsi,

notre foi également est toujours une foi qui commence et nous devons encore

accomplir un grand chemin. Mais il est essentiel que ce soit une foi ouverte et

que nous nous laissions guider par Jésus, car non seulement Il connaît le

Chemin, mais il est le Chemin.

Cependant, la générosité impétueuse de Pierre ne le

sauve pas des risques liés à la faiblesse humaine. Du reste, c'est ce que nous

aussi, nous pouvons reconnaître sur la base de notre vie. Pierre a suivi Jésus

avec élan, il a surmonté l'épreuve de la foi, en s'abandonnant à Lui.

Toutefois, le moment vient où lui aussi cède à la peur et chute: il

trahit le Maître (cf. Mc 14, 66-72). L'école de la foi n'est pas une

marche triomphale, mais un chemin parsemé de souffrances et d'amour, d'épreuves

et de fidélité à renouveler chaque jour. Pierre, qui avait promis une fidélité

absolue, connaît l'amertume et l'humiliation du reniement: le téméraire

apprend l'humilité à ses dépends. Pierre doit apprendre lui aussi à être faible

et à avoir besoin de pardon. Lorsque finalement son masque tombe et qu'il

comprend la vérité de son coeur faible de pécheur croyant, il éclate en

sanglots de repentir libérateurs. Après ces pleurs, il est désormais prêt pour

sa mission.

Un matin de printemps, cette mission lui sera confiée

par Jésus ressuscité. La rencontre aura lieu sur les rives du lac de Tibériade.

C'est l'évangéliste Jean qui nous rapporte le dialogue qui a lieu en cette

circonstance entre Jésus et Pierre. On y remarque un jeu de verbes très

significatif. En grec, le verbe "filéo" exprime l'amour d'amitié,

tendre mais pas totalisant, alors que le verbe "agapáo" signifie

l'amour sans réserves, total et inconditionné. La première fois, Jésus demande

à Pierre: "Simon... m'aimes-tu (agapls-me)" de cet amour total

et inconditionné (Jn 21, 15)? Avant l'expérience de la trahison, l'Apôtre

aurait certainement dit: "Je t'aime (agapô-se) de manière

inconditionnelle". Maintenant qu'il a connu la tristesse amère de

l'infidélité, le drame de sa propre faiblesse, il dit avec humilité:

"Seigneur, j'ai beaucoup d'amitié pour toi (filô-se)", c'est-à-dire

"je t'aime de mon pauvre amour humain". Le Christ insiste:

"Simon, m'aimes-tu de cet amour total que je désire?". Et Pierre

répète la réponse de son humble amour humain: "Kyrie, filô-se",

"Seigneur, j'ai beaucoup d'amitié pour toi, comme je sais aimer". La

troisième fois, Jésus dit seulement à Simon: "Fileîs-me?,

"As-tu de l'amitié pour moi?". Simon comprend que son pauvre amour

suffit à Jésus, l'unique dont il est capable, mais il est pourtant attristé que

le Seigneur ait dû lui parler ainsi. Il répond donc: "Seigneur, tu

sais tout: tu sais combien j'ai d'amitié pour toi" (filô-se)".

On pourrait dire que Jésus s'est adapté à Pierre, plutôt que Pierre à Jésus!

C'est précisément cette adaptation divine qui donne de l'espérance au disciple,

qui a connu la souffrance de l'infidélité. C'est de là que naît la confiance

qui le rendra capable de la sequela Christi jusqu'à la fin: "Jésus

disait cela pour signifier par quel genre de mort Pierre rendrait gloire à Dieu.

Puis il lui dit encore: "Suis-moi"" (Jn 21, 19).

A partir de ce jour, Pierre a "suivi" le

Maître avec la conscience précise de sa propre fragilité; mais cette conscience

ne l'a pas découragé. Il savait en effet pouvoir compter sur la présence du Ressuscité

à ses côtés. De l'enthousiasme naïf de l'adhésion initiale, en passant à

travers l'expérience douloureuse du reniement et des pleurs de la conversion,

Pierre est arrivé à mettre sa confiance en ce Jésus qui s'est adapté à sa

pauvre capacité d'amour. Et il nous montre ainsi le chemin à nous aussi, malgré

toute notre faiblesse. Nous savons que Jésus s'adapte à notre faiblesse. Nous

le suivons, avec notre pauvre capacité d'amour et nous savons que Jésus est bon

et nous accepte. Cela a été pour Pierre un long chemin qui a fait de lui un

témoin fiable, "pierre" de l'Église, car constamment ouvert à

l'action de l'Esprit de Jésus. Pierre lui-même se qualifiera de:

"témoin de la passion du Christ, et je communierai à la gloire qui va se

révéler" (1 P 5, 1). Lorsqu'il écrira ces paroles, il sera désormais âgé,

en route vers la conclusion de sa vie qu'il scellera par le martyre. Il sera

alors en mesure de décrire la joie véritable et d'indiquer où on peut la

puiser: la source est le Christ, auquel on croit et que l'on aime avec

notre foi faible mais sincère, malgré notre fragilité. C'est pourquoi, il

écrira aux chrétiens de sa communauté, et il nous le dit à nous aussi:

"Lui que vous aimez sans l'avoir vu, en qui vous croyez sans le voir

encore; et vous tressaillez d'une joie inexprimable qui vous transfigure, car

vous allez obtenir votre salut qui est l'aboutissement de votre foi" (1 P

1, 8-9).

***

Je salue cordialement les pèlerins francophones, en

particulier le groupe de l’oeuvre des écoles d’Orient, la communauté de l’Arche

de Saint-Rémy-lès-Chevreuse, ainsi que les jeunes du Foyer de Charité de

Châteauneuf-de-Galaure. Que votre pèlerinage aux tombeaux des Apôtres Pierre et

Paul ravive votre foi en Jésus Christ, et qu’il renouvelle en vous le désir de

chercher toujours plus le visage de Dieu.

***

Chers frères et soeurs, demain je me rendrai en Pologne, patrie du bien-aimé Pape Jean-Paul II; je reparcourrai les lieux de sa vie et de son ministère sacerdotal et épiscopal. Je rends grâce au Seigneur de l'opportunité qu'il m'offre de réaliser un désir que je conservais depuis longtemps dans mon coeur. Chers frères et soeurs, je vous invite à m'accompagner par la prière au cours de ce Voyage apostolique, que je m'apprête à accomplir avec une grande espérance et que je confie à la Sainte Vierge, si vénérée en Pologne. Que ce soit Elle qui guide mes pas afin que je puisse confirmer dans la foi la bien-aimée communauté catholique polonaise et l'encourager à affronter, par une action évangélisatrice incisive, les défis du moment présent. Que ce soit Marie qui obtienne pour toute cette nation un printemps renouvelé de foi et de progrès civil, en conservant toujours vivante la mémoire de mon grand prédécesseur.

© Copyright 2006 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20060524.html

Guercino (1591–1666), sa Pietro, 1650, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento

Also known as

Cephas

First Pope

Keipha

Kepha

Pre-eminent Apostle

Prince of the Apostles

Shimon Bar-Yonah

Shimon Ben-Yonah

Simeon

Simon

Simon bar Jonah

Simon ben Jonah

Simon Peter

29 June (feast of

Peter and Paul)

22

February (feast of

the Chair

of Peter, emblematic of the world unity of the Church)

1 August (Saint

Peter in Chains)

18

November (feast of

the dedication of the Basilicas of Peter and Paul)

Profile

Professional fisherman.

Brother of Saint Andrew

the Apostle, the man who led him to Christ. Apostle. Renamed “Peter” (rock)

by Jesus to indicate that Peter would be the rock-like foundation on which the

Church would be built. Bishop.

First Pope. Miracle worker.

Born

c.1 in Bethsaida as Simon

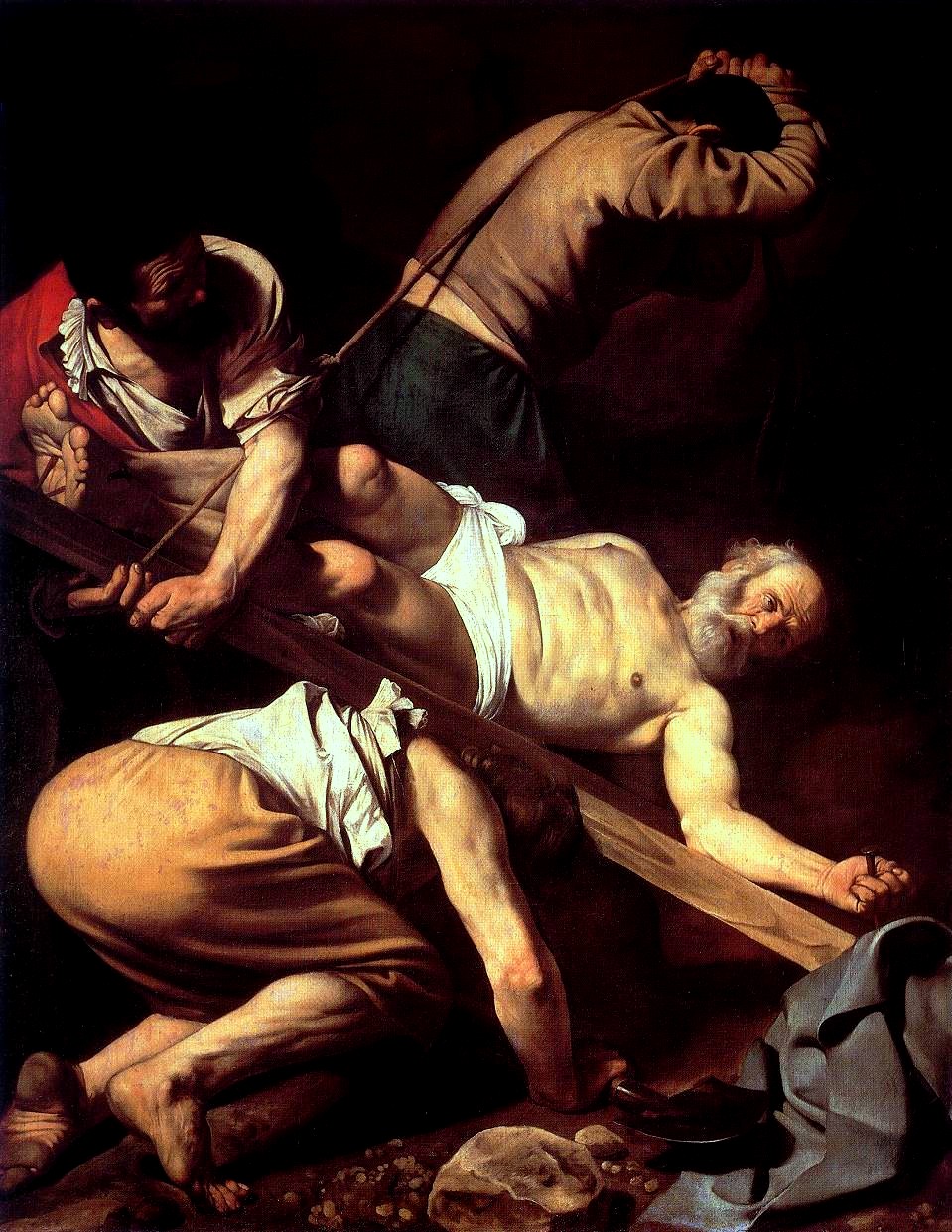

crucified head

downward because he claimed he was not worthy to die in the same manner as

Christ

Name Meaning

rock

–

dioceses, archdioceses and

vicariates apostolic

Brno,

Czechia

Maralal,

Kenya

Peterborough,

Ontario

in Belgium

in Brazil

in England

in France

in Germany

–

in Italy

Adria,

city of

–

in Malta

keys of

Heaven

Apostle holding a book

Apostle holding a scroll

bald man,

often with a fringe of hair on the sides and a tuft on top

man crucified head

downwards

pope and

bearing keys and

a double-barred cross

Additional Information

A

Garner of Saints, by Allen Banks Hinds, M.A.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Golden

Legend: Chairing of Saint Peter

Golden

Legend: Life of Saint Peter the Apostle

Golden

Legend: Peter in Chains

Handbook

of Christian Feasts and Customs

Illustrated

Catholic Family Annual: Saint Peter’s Fish

Illustrated

Catholic Family Annual: Saint Peter’s Statue

Life

and Mission of Saint Peter, by Father Richard

Brennan

Light

From the Altar, edited by Father James

J McGovern

Little

Lives of the Great Saints

Lives

of Illustrious Men, by Saint Jerome

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Meditations

on the Gospels for Every Day in the Year, by Father Pierre

Médaille

Our

Lord and Saint Peter, from Christ Legends, by Selma Lagerlöf

Quodcumque

in orbe, by Saint Paulinus

of Aquileia

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saint

Peter the Great-Hearted, by Monsignor John

T McMahon

Saints

of the Canon, by Monsignor John

T McMahon

Saints

Through the Ages, by Sister M. Julienne, C.S.J.

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

–

by Pope Benedict

XVI

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

Breviarium SOP: Vigil of Saints Peter and Paul – Domine Quo

Vadis?

Franciscan Media: Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul

uCatholic:

Saint Peter the Apostle

uCatholic:

Bones of Saint Peter Displayed

uCatholic: Did Saint Peter Have a Daughter?

Wikipedia: Saint Peter the Apostle

Wikipedia: Saints Peter and Paul

images

audio

video

e-books

A

Commentary by Writers of the First Five Centuries on the place of Saint Peter

in the New Testament, and that of Saint Peter’s Successors in the Church,

by Father James Waterworth

Life

of Saint Peter for the Young, by George Ludington Weed

Saint

Peter and the First Years of Christianity, by Father Constant Fouard

Saint

Peter, Bishop of Rome, by Father Thomas Stiverd Livius

Saint

Peter, His Name and His Office, by Thomas W Allies

Saint

Peter in Rome and his Tomb on Vatican Hill, by Father Arthur Stapylton

Barnes

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Readings

Out of the whole world one man, Peter, is chosen to

preside at the of all nations and to be set over all the apostles and all the

fathers of the church. Though there are in God’s people many bishops and many

shepherds, Peter is thus appointed to rule in his own person those whom Christ

also rules as the original ruler. Beloved, how great and wonderful is this

sharing in his power that God in his goodness has given to this man. Whatever

Christ has willed to be shared in common by Peter and the other leaders of the

Church, it is only through Peter that he has given to others what he has not

refused to bestow on them. Jesus said: “Upon this rock I will build my Church,

and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” On this strong foundation,

he says, I will build an everlasting temple. The great height of my Church,

which is to penetrate the heavens, shall rise on the firm foundation of this

faith. Blessed Peter is therefore told: “To you I will give the keys of the

kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound also in heaven.

Whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed also in heaven.” – from a

sermon by Pope Saint Leo

the Great

MLA Citation

“Saint Peter the Apostle“. CatholicSaints.Info.

27 April 2021. Web. 29 June 2021.

<http://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-the-apostle/>

SOURCE : http://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-the-apostle/

St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles

The life of St. Peter may be conveniently considered

under the following heads:

St.

Peter in Jerusalem and Palestine after the Ascension

Missionary

journeys in the East; the Council of the Apostles

Activity

and death in Rome; burial-place

Until the Ascension of Christ

Bethsaida

St. Peter's true and

original name was Simon, sometimes occurring in the form Symeon.

(Acts

15:14; 2

Peter 1:1). He was the son of Jona (Johannes) and was born in Bethsaida (John

1:42, 44), a town on Lake

Genesareth, the position of which cannot be established with certainty,

although it is usually sought at the northern end of the lake. The Apostle

Andrew was his brother, and the Apostle

Philip came from the same town.

Capharnaum

Simon settled in Capharnaum,

where he was living with his mother-in-law in his own house (Matthew

8:14; Luke

4:38) at the beginning of Christ's public

ministry (about A.D. 26-28). Simon was thus married, and, according

to Clement

of Alexandria (Stromata, III, vi, ed. Dindorf, II, 276), had children.

The same writer relates the tradition that

Peter's wife suffered martyrdom (ibid.,

VII, xi ed. cit., III, 306). Concerning these facts, adopted by Eusebius (Church

History III.31) from Clement,

the ancient Christian literature

which has come down to us is silent. Simon pursued in Capharnaum the

profitable occupation of fisherman in Lake

Genesareth, possessing his own boat (Luke

5:3).

Peter meets Our Lord

Like so many of his Jewish contemporaries, he was attracted by the Baptist's preaching of penance and was, with his brother Andrew, among John's associates in Bethania on the eastern bank of the Jordan. When, after the High Council had sent envoys for the second time to the Baptist, the latter pointed to Jesus who was passing, saying, "Behold the Lamb of God", Andrew and another disciple followed the Saviour to his residence and remained with Him one day.

Later, meeting his brother Simon, Andrew said

"We have found the Messias",

and brought him to Jesus,

who, looking upon him, said: "Thou art Simon the son of Jona: thou shalt

be called Cephas, which is interpreted Peter". Already, at this first

meeting, the Saviour foretold

the change of Simon's name to Cephas (Kephas; Aramaic Kipha, rock), which

is translated Petros (Latin, Petrus) a proof that Christ had

already special views with regard to Simon. Later, probably at the time of his definitive

call to the Apostolate with the eleven other Apostles, Jesus actually

gave Simon the name of Cephas (Petrus), after which he was usually called

Peter, especially by Christ on

the solemn occasion after Peter's profession of faith (Matthew

16:18; cf. below). The Evangelists often

combine the two names, while St.

Paul uses the name Cephas.

Peter becomes a disciple

After the first meeting Peter with the other

early disciples remained

with Jesus for

some time, accompanying Him to Galilee (Marriage at Cana), Judaea,

and Jerusalem,

and through Samaria back

to Galilee (John

2-4). Here Peter resumed his occupation of fisherman for a short time,

but soon received the definitive call of the Saviour to

become one of His permanent disciples.

Peter and Andrew were

engaged at their calling when Jesus met

and addressed them: "Come ye after me, and I will make you to be fishers

of men".

On the same occasion the sons of Zebedee were called (Matthew

4:18-22; Mark

1:16-20; Luke

5:1-11; it is here assumed that Luke refers

to the same occasion as the other Evangelists).

Thenceforth Peter remained always in the immediate neighbourhood of Our

Lord. After preaching the Sermon on the Mount and curing the son of

the centurion in Capharnaum, Jesus came

to Peter's house and cured his wife's mother, who was sick of a fever (Matthew

8:14-15; Mark

1:29-31). A little later Christ chose

His Twelve

Apostles as His constant associates in preaching the kingdom

of God.

Growing prominence among the Twelve

Among the Twelve Peter soon became conspicuous. Though of irresolute character, he clings with the greatest fidelity, firmness of faith, and inward love to the Saviour; rash alike in word and act, he is full of zeal and enthusiasm, though momentarily easily accessible to external influences and intimidated by difficulties. The more prominent the Apostles become in the Evangelical narrative, the more conspicuous does Peter appear as the first among them. In the list of the Twelve on the occasion of their solemn call to the Apostolate, not only does Peter stand always at their head, but the surname Petrus given him by Christ is especially emphasized (Matthew 10:2): "Duodecim autem Apostolorum nomina haec: Primus Simon qui dicitur Petrus. . ."; Mark 3:14-16: "Et fecit ut essent duodecim cum illo, et ut mitteret eos praedicare . . . et imposuit Simoni nomen Petrus"; Luke 6:13-14: "Et cum dies factus esset, vocavit discipulos suos, et elegit duodecim ex ipsis (quos et Apostolos nominavit): Simonem, quem cognominavit Petrum . . ." On various occasions Peter speaks in the name of the other Apostles (Matthew 15:15; 19:27; Luke 12:41, etc.). When Christ's words are addressed to all the Apostles, Peter answers in their name (e.g., Matthew 16:16). Frequently the Saviour turns specially to Peter (Matthew 26:40; Luke 22:31, etc.).

Very characteristic is the expression of true fidelity

to Jesus,

which Peter addressed to Him in the name of the other Apostles. Christ,

after He had spoken of the mystery of

the reception of His Body and Blood (John

6:22 sqq.) and many of His disciples had

left Him, asked the Twelve if

they too should leave Him; Peter's answer comes immediately: "Lord to whom

shall we go? thou hast the words of eternal life.

And we have believed and

have known,

that thou art the Holy

One of God" (Vulgate "thou

art the Christ,

the Son

of God"). Christ Himself

unmistakably accords Peter a special precedence and the first place among

the Apostles,

and designates him for such on various occasions. Peter was one of the

three Apostles (with James and John)

who were with Christ on

certain special occasions the raising of the daughter of Jairus from the dead (Mark

5:37; Luke

8:51); the Transfiguration of Christ (Matthew

17:1; Mark

9:1; Luke

9:28), the Agony in

the Garden

of Gethsemani (Matthew

26:37; Mark

14:33). On several occasions also Christ favoured

him above all the others; He enters Peter's boat on Lake

Genesareth to preach to the multitude on the shore (Luke

5:3); when He was miraculously walking

upon the waters, He called Peter to come to Him across the lake (Matthew

14:28 sqq.); He sent him to the lake to catch the fish in whose mouth Peter

found the stater to

pay as tribute (Matthew

17:24 sqq.).

Peter becomes head of the apostles

In especially solemn fashion Christ accentuated Peter's precedence among the Apostles, when, after Peter had recognized Him as the Messias, He promised that he would be head of His flock. Jesus was then dwelling with His Apostles in the vicinity of Caesarea Philippi, engaged on His work of salvation. As Christ's coming agreed so little in power and glory with the expectations of the Messias, many different views concerning Him were current. While journeying along with His Apostles, Jesus asks them: "Whom do men say that the Son of man is?" The Apostles answered: "Some John the Baptist, and other some Elias, and others Jeremias, or one of the prophets". Jesus said to them: "But whom do you say that I am?" Simon said: "Thou art Christ, the Son of the living God". And Jesus answering said to him: "Blessed art thou, Simon Bar-Jona: because flesh and blood hath not revealed it to thee, but my Father who is in heaven. And I say to thee: That thou art Peter [Kipha, a rock], and upon this rock [Kipha] I will build my church [ekklesian], and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven". Then he commanded his disciples, that they should tell no one that he was Jesus the Christ (Matthew 16:13-20; Mark 8:27-30; Luke 9:18-21).

By the word "rock" the Saviour cannot have meant Himself, but only Peter, as is so much more apparent in Aramaic in which the same word (Kipha) is used for "Peter" and "rock". His statement then admits of but one explanation, namely, that He wishes to make Peter the head of the whole community of those who believed in Him as the true Messias; that through this foundation (Peter) the Kingdom of Christ would be unconquerable; that the spiritual guidance of the faithful was placed in the hands of Peter, as the special representative of Christ. This meaning becomes so much the clearer when we remember that the words "bind" and "loose" are not metaphorical, but Jewish juridical terms. It is also clear that the position of Peter among the other Apostles and in the Christian community was the basis for the Kingdom of God on earth, that is, the Church of Christ. Peter was personally installed as Head of the Apostles by Christ Himself. This foundation created for the Church by its Founder could not disappear with the person of Peter, but was intended to continue and did continue (as actual history shows) in the primacy of the Roman Church and its bishops.

Entirely inconsistent and in itself untenable is the position of Protestants who (like Schnitzer in recent times) assert that the primacy of the Roman bishops cannot be deduced from the precedence which Peter held among the Apostles. Just as the essential activity of the Twelve Apostles in building up and extending the Church did not entirely disappear with their deaths, so surely did the Apostolic Primacy of Peter not completely vanish. As intended by Christ, it must have continued its existence and development in a form appropriate to the ecclesiastical organism, just as the office of the Apostles continued in an appropriate form.

Objections have been raised against the genuineness of

the wording of the passage, but the unanimous testimony of the manuscripts,

the parallel passages in the other Gospels,

and the fixed belief of

pre-Constantine literature furnish the surest proofs of

the genuineness and

untampered state of the text of Matthew (cf.

"Stimmen aus Maria Laach", I, 1896,129 sqq.; "Theologie und

Glaube", II, 1910, 842 sqq.).

His difficulty with Christ's Passion

In spite of his firm faith in Jesus, Peter had so far no clear knowledge of the mission and work of the Saviour. The sufferings of Christ especially, as contradictory to his worldly conception of the Messias, were inconceivable to him, and his erroneous conception occasionally elicited a sharp reproof from Jesus (Matthew 16:21-23, Mark 8:31-33). Peter's irresolute character, which continued notwithstanding his enthusiastic fidelity to his Master, was clearly revealed in connection with the Passion of Christ. The Saviour had already told him that Satan had desired him that he might sift him as wheat. But Christ had prayed for him that his faith fail not, and, being once converted, he confirms his brethren (Luke 22:31-32). Peter's assurance that he was ready to accompany his Master to prison and to death, elicited Christ's prediction that Peter should deny Him (Matthew 26:30-35; Mark 14:26-31; Luke 22:31-34; John 13:33-38).

When Christ proceeded

to wash

the feet of His disciples before

the Last

Supper, and came first to Peter, the latter at first protested, but,

on Christ's declaring

that otherwise he should have no part with Him, immediately said: "Lord,

not only my feet, but also my hands and my head" (John

13:1-10). In the Garden

of Gethsemani Peter had to submit to the Saviour's reproach

that he had slept like the others, while his Master suffered

deadly anguish (Mark

14:37). At the seizing of Jesus,

Peter in an outburst of anger wished

to defend his Master by force,

but was forbidden to do so. He at first took to flight with the other Apostles (John

18:10-11; Matthew

26:56); then turning he followed his captured Lord to the courtyard of

the High

Priest, and there denied Christ,

asserting explicitly and swearing that he knew Him

not (Matthew

26:58-75; Mark

14:54-72; Luke

22:54-62; John

18:15-27). This denial was of course due, not to a lapse of interior faith in Christ,

but to exterior fear and

cowardice. His sorrow was thus so much the greater, when, after his Master had

turned His gaze towards him, he clearly recognized what he had done.

The Risen Lord confirms Peter's precedence

In spite of this weakness, his position as head of

the Apostles was

later confirmed by Jesus,

and his precedence was not less conspicuous after the Resurrection than

before. The women,

who were the first to find Christ's

tomb empty, received from the angel a

special message for Peter (Mark

16:7). To him alone of the Apostles did Christ appear

on the first day after the Resurrection (Luke

24:34; 1

Corinthians 15:5). But, most important of all, when He appeared at

the Lake

of Genesareth, Christ renewed

to Peter His special commission to feed and defend His flock, after Peter had

thrice affirmed his special love for

his Master (John

21:15-17). In conclusion Christ foretold

the violent death

Peter would have to suffer, and thus invited him to follow Him in a special

manner (John

21:20-23). Thus was Peter called and

trained for the Apostleship and

clothed with the primacy of

the Apostles,

which he exercised in a most unequivocal manner after Christ's

Ascension into Heaven.

Benjamin West, Saint Pierre prêchant lors de la Pentecôte

St. Peter in Jerusalem and Palestine after the

Ascension

Our information concerning the earliest Apostolic activity of St. Peter in Jerusalem, Judaea, and the districts stretching northwards as far as Syria is derived mainly from the first portion of the Acts of the Apostles, and is confirmed by parallel statements incidentally in the Epistles of St. Paul.

Among the crowd of Apostles and disciples who, after Christ's Ascension into Heaven from Mount Olivet, returned to Jerusalem to await the fulfilment of His promise to send the Holy Ghost, Peter is immediately conspicuous as the leader of all, and is henceforth constantly recognized as the head of the original Christian community in Jerusalem. He takes the initiative in the appointment to the Apostolic College of another witness of the life, death and resurrection of Christ to replace Judas (Acts 1:15-26). After the descent of the Holy Ghost on the feast of Pentecost, Peter standing at the head of the Apostles delivers the first public sermon to proclaim the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, and wins a large number of Jews as converts to the Christian community (Acts 2:14-41). First of the Apostles, he worked a public miracle, when with John he went up into the temple and cured the lame man at the Beautiful Gate. To the people crowding in amazement about the two Apostles, he preaches a long sermon in the Porch of Solomon, and brings new increase to the flock of believers (Acts 3:1-4:4).

In the subsequent examinations of the two Apostles before the Jewish High Council, Peter defends in undismayed and impressive fashion the cause of Jesus and the obligation and liberty of the Apostles to preach the Gospel (Acts 4:5-21). When Ananias and Sapphira attempt to deceive the Apostles and the people Peter appears as judge of their action, and God executes the sentence of punishment passed by the Apostle by causing the sudden death of the two guilty parties (Acts 5:1-11). By numerous miracles God confirms the Apostolic activity of Christ's confessors, and here also there is special mention of Peter, since it is recorded that the inhabitants of Jerusalem and neighbouring towns carried their sick in their beds into the streets so that the shadow of Peter might fall on them and they might be thereby healed (Acts 5:12-16). The ever-increasing number of the faithful caused the Jewish supreme council to adopt new measures against the Apostles, but "Peter and the Apostles" answer that they "ought to obey God rather than men" (Acts 5:29 sqq.). Not only in Jerusalem itself did Peter labour in fulfilling the mission entrusted to him by his Master. He also retained connection with the other Christian communities in Palestine, and preached the Gospel both there and in the lands situated farther north. When Philip the Deacon had won a large number of believers in Samaria, Peter and John were deputed to proceed thither from Jerusalem to organize the community and to invoke the Holy Ghost to descend upon the faithful. Peter appears a second time as judge, in the case of the magician Simon, who had wished to purchase from the Apostles the power that he also could invoke the Holy Ghost (Acts 8:14-25). On their way back to Jerusalem, the two Apostles preached the joyous tidings of the Kingdom of God. Subsequently, after Paul's departure from Jerusalem and conversion before Damascus, the Christian communities in Palestine were left at peace by the Jewish council.

Peter now undertook an extensive missionary tour, which brought him to the maritime cities, Lydda, Joppe, and Caesarea. In Lydda he cured the palsied Eneas, in Joppe he raised Tabitha (Dorcas) from the dead; and at Caesarea, instructed by a vision which he had in Joppe, he baptized and received into the Church the first non-Jewish Christians, the centurion Cornelius and his kinsmen (Acts 9:31-10:48). On Peter's return to Jerusalem a little later, the strict Jewish Christians, who regarded the complete observance of the Jewish law as binding on all, asked him why he had entered and eaten in the house of the uncircumcised. Peter tells of his vision and defends his action, which was ratified by the Apostles and the faithful in Jerusalem (Acts 11:1-18).

A confirmation of the position accorded to Peter

by Luke,

in the Acts,

is afforded by the testimony of St.

Paul (Galatians

1:18-20). After his conversion and

three years' residence in Arabia, Paul came

to Jerusalem "to see Peter". Here the Apostle

of the Gentiles clearly designates Peter as the authorized head of

the Apostles and

of the early Christian

Church. Peter's long residence in Jerusalem and

Palestine soon came to an end. Herod

Agrippa I began (A.D. 42-44) a new persecution of

the Church in Jerusalem;

after the execution of James, the son of Zebedee, this ruler had Peter

cast into prison,

intending to have him also executed after the Jewish Pasch was

over. Peter, however, was freed in a miraculous manner,

and, proceeding to the house of the mother

of John Mark, where many of the faithful were

assembled for prayer,

informed them of his liberation from the hands of Herod,

commissioned them to communicate the fact to James and the brethren,

and then left Jerusalem to

go to "another place" (Acts

12:1-18). Concerning St. Peter's subsequent activity we receive no further

connected information from the extant sources, although we possess short

notices of certain individual episodes of his later life.

Missionary journeys in the East; Council of the

Apostles

St.

Luke does not tell us whither Peter went after his liberation from

the prison in Jerusalem.

From incidental statements we know that

he subsequently made extensive missionary tours in the East, although we are

given no clue to the chronology of

his journeys. It is certain that

he remained for a time at Antioch;

he may even have returned thither several times. The Christian community

of Antioch was

founded by Christianized Jews who

had been driven from Jerusalem by

the persecution (Acts

11:19 sqq.). Peter's residence among them is proved by

the episode concerning the observance of the Jewish

ceremonial law even by Christianized pagans,

related by St.

Paul (Galatians

2:11-21). The chief Apostles in Jerusalem —

the "pillars", Peter, James, and John — had

unreservedly approved St.

Paul's Apostolate to the Gentiles,

while they themselves intended to labour principally among the Jews.

While Paul was

dwelling in Antioch (the date cannot

be accurately determined), St. Peter came thither and mingled freely with

the non-Jewish Christians of

the community, frequenting their houses and sharing their meals. But when

the Christianized Jews arrived

in Jerusalem,

Peter, fearing lest these rigid observers of the Jewish

ceremonial law should be scandalized thereat,

and his influence with the Jewish

Christians be imperiled, avoided thenceforth eating with the uncircumcised.

His conduct made a great impression on the other Jewish Christians at Antioch,

so that even Barnabas, St.

Paul's companion, now avoided eating with the Christianized pagans.

As this action was entirely opposed to the principles and practice of Paul,

and might lead to confusion among the converted pagans,

this Apostle addressed

a public reproach to St. Peter, because his conduct seemed to indicate a wish

to compel the pagan converts to

become Jews and

accept circumcision and

the Jewish

law. The whole incident is another proof of

the authoritative position of St. Peter in the early Church,

since his example and conduct was regarded as decisive. But Paul,

who rightly saw the inconsistency in the conduct of Peter and the Jewish Christians,

did not hesitate to defend the immunity of converted pagans from

the Jewish

Law. Concerning Peter's subsequent attitude on this question St.

Paul gives us no explicit information. But it is highly probable that

Peter ratified the contention of the Apostle

of the Gentiles, and thenceforth conducted himself towards the Christianized pagans as

at first. As the principal opponents of his views in this connexion, Paul names

and combats in all his writings only the extreme

Jewish Christians coming "from James" (i.e., from Jerusalem).

While the date of

this occurrence, whether before or after the Council of the Apostles, cannot be

determined, it probably took place after the council (see below). The

later tradition,

which existed as early as the end of the second century (Origen,

"Hom. vi in Lucam"; Eusebius, Church

History III.36), that Peter founded the Church

of Antioch, indicates the fact that he laboured a long period there, and

also perhaps that he dwelt there towards the end of his life and then

appointed Evodrius,

the first of the line of Antiochian bishops,

head of the community. This latter view would best explain the tradition referring

the foundation of the Church

of Antioch to St. Peter.

It is also probable that Peter pursued his Apostolic labours in various districts of Asia Minor for it can scarcely be supposed that the entire period between his liberation from prison and the Council of the Apostles was spent uninterruptedly in one city, whether Antioch, Rome, or elsewhere. And, since he subsequently addressed the first of his Epistles to the faithful in the Provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, and Asia, one may reasonably assume that he had laboured personally at least in certain cities of these provinces, devoting himself chiefly to the Diaspora. The Epistle, however, is of a general character, and gives little indication of personal relations with the persons to whom it is addressed. The tradition related by Bishop Dionysius of Corinth (in Eusebius, Church History II.25) in his letter to the Roman Church under Pope Soter (165-74), that Peter had (like Paul) dwelt in Corinth and planted the Church there, cannot be entirely rejected. Even though the tradition should receive no support from the existence of the "party of Cephas", which Paul mentions among the other divisions of the Church of Corinth (1 Corinthians 1:12; 3:22), still Peter's sojourn in Corinth (even in connection with the planting and government of the Church by Paul) is not impossible. That St. Peter undertook various Apostolic journeys (doubtless about this time, especially when he was no longer permanently residing in Jerusalem) is clearly established by the general remark of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 9:5, concerning the "rest of the apostles, and the brethren [cousins] of the Lord, and Cephas", who were travelling around in the exercise of their Apostleship.

Peter returned occasionally to the original Christian Church of Jerusalem, the guidance of which was entrusted to St. James, the relative of Jesus, after the departure of the Prince of the Apostles (A.D. 42-44). The last mention of St. Peter in the Acts (15:1-29; cf. Galatians 2:1-10) occurs in the report of the Council of the Apostles on the occasion of such a passing visit. In consequence of the trouble caused by extreme Jewish Christians to Paul and Barnabas at Antioch, the Church of this city sent these two Apostles with other envoys to Jerusalem to secure a definitive decision concerning the obligations of the converted pagans (see JUDAIZERS). In addition to James, Peter and John were then (about A.D. 50-51) in Jerusalem. In the discussion and decision of this important question, Peter naturally exercised a decisive influence. When a great divergence of views had manifested itself in the assembly, Peter spoke the deciding word. Long before, in accordance with God's testimony, he had announced the Gospels to the heathen (conversion of Cornelius and his household); why, therefore, attempt to place the Jewish yoke on the necks of converted pagans? After Paul and Barnabas had related how God had wrought among the Gentiles by them, James, the chief representative of the Jewish Christians, adopted Peter's view and in agreement therewith made proposals which were expressed in an encyclical to the converted pagans.

The occurrences in Caesarea and Antioch and

the debate at the Council of Jerusalem show clearly Peter's attitude towards

the converts from paganism.

Like the other eleven original Apostles,

he regarded himself as called to preach the Faith in Jesus first

among the Jews (Acts

10:42), so that the chosen people of God might

share in the salvation in Christ,

promised to them primarily and issuing from their midst.

The vision at Joppe and

the effusion of the Holy

Ghost over the converted pagan Cornelius and

his kinsmen determined

Peter to admit these forthwith into the community of the faithful,

without imposing on them the Jewish

Law. During his Apostolic journeys

outside Palestine, he recognized in practice the equality of Gentile and Jewish converts,

as his original conduct at Antioch proves.

His aloofness from the Gentile converts,

out of consideration for the Jewish Christians from Jerusalem,

was by no means an official recognition of the views of the extreme Judaizers,

who were so opposed to St.

Paul. This is established clearly and incontestably by his attitude at the

Council of Jerusalem. Between Peter and Paul there

was no dogmatic difference

in their conception of salvation for Jewish and Gentile Christians.

The recognition of Paul as

the Apostle of

the Gentiles (Galatians

2:1-9) was entirely sincere, and excludes all question of a fundamental

divergence of views. St. Peter and the other Apostles recognized

the converts from paganism as Christian brothers

on an equal footing; Jewish and Gentile Christians formed

a single Kingdom

of Christ. If therefore Peter devoted the preponderating portion of

his Apostolic activity

to the Jews,

this arose chiefly from practical considerations, and from the position

of Israel as

the Chosen People. Baur's hypothesis of opposing currents of

"Petrinism" and "Paulinism" in the early Church is

absolutely untenable, and is today entirely rejected by Protestants.

Activity and death in Rome; burial place

It is an indisputably established historical fact that St. Peter laboured in Rome during the last portion of his life, and there ended his earthly course by martyrdom. As to the duration of his Apostolic activity in the Roman capital, the continuity or otherwise of his residence there, the details and success of his labours, and the chronology of his arrival and death, all these questions are uncertain, and can be solved only on hypotheses more or less well-founded. The essential fact is that Peter died at Rome: this constitutes the historical foundation of the claim of the Bishops of Rome to the Apostolic Primacy of Peter.

St. Peter's residence and death in Rome are

established beyond contention as historical facts by a series of distinct

testimonies extending from the end of the first to the end of the second

centuries, and issuing from several lands.

That the manner, and therefore the place of his death,

must have been known in

widely extended Christian circles

at the end of the first century is clear from the remark introduced into

the Gospel

of St. John concerning Christ's prophecy that

Peter was bound to Him and would be led whither he would not — "And this

he said, signifying by what death he should glorify God"

(John

21:18-19, see above). Such a remark presupposes in the readers of the Fourth

Gospel a knowledge of

the death of Peter.

St.

Peter's First Epistle was written almost undoubtedly from Rome,

since the salutation at the end reads: "The church that

is in Babylon, elected together with you, saluteth you: and so doth my

son Mark"

(5:13).

Babylon must here be identified with the Roman

capital; since Babylon

on the Euphrates, which lay in ruins, or New Babylon (Seleucia) on the

Tigris, or the Egyptian Babylon

near Memphis,

or Jerusalem cannot

be meant, the reference must be to Rome,

the only city which is called Babylon elsewhere in ancient Christian literature

(Revelation

17:5; 18:10;

"Oracula Sibyl.", V, verses 143 and 159, ed. Geffcken, Leipzig,

1902, 111).

From Bishop

Papias of Hierapolis and Clement

of Alexandria, who both appeal to the testimony of the old presbyters (i.e.,

the disciples of

the Apostles),

we learn that Mark wrote

his Gospel in Rome at

the request of the Roman Christians,

who desired a written memorial of the doctrine preached

to them by St. Peter and his disciples (Eusebius, Church

History II.15, 3.40, 6.14);

this is confirmed by Irenaeus (Against

Heresies 3.1). In connection with this information concerning

the Gospel

of St. Mark, Eusebius,

relying perhaps on an earlier source, says that Peter described Rome figuratively

as Babylon in his First

Epistle.

Another testimony concerning the martyrdom of

Peter and Paul is

supplied by Clement

of Rome in his Epistle

to the Corinthians (written about A.D. 95-97), wherein he says (chapter

5): "Through zeal and

cunning the greatest and most righteous supports [of the Church]

have suffered persecution and

been warred to death. Let us place before our eyes the good Apostles —

St. Peter, who in consequence of unjust zeal,

suffered not one or two, but numerous miseries, and, having thus given

testimony (martyresas), has entered the merited place

of glory". He then mentions Paul and

a number of elect,

who were assembled with the others and sufferedmartyrdom "among

us" (en hemin, i.e., among the Romans, the meaning that the

expression also bears in chapter

4). He is speaking undoubtedly, as the whole passage proves,

of the Neronian persecution,

and thus refers the martyrdom of

Peter and Paul to

that epoch.

In his letter written at the beginning of the second

century (before 117), while being brought to Rome for martyrdom,

the venerable Bishop

Ignatius of Antioch endeavours by every means to restrain the Roman Christians from

striving for his pardon, remarking: "I issue you no commands, like Peter

and Paul:

they were Apostles,

while I am but a captive" (Epistle

to the Romans 4). The meaning of this remark must be that the two Apostles laboured

personally in Rome,

and with Apostolic authority

preached the Gospel there.

Bishop Dionysius of Corinth, in his letter to

the Roman

Church in the time of Pope

Soter (165-74), says: "You have therefore by your urgent

exhortation bound close together the sowing of Peter and Paul at Rome and Corinth.

For both planted the seed of the Gospel also in Corinth,

and together instructed us, just as they likewise taught in the same place

in Italy and

at the same time suffered martyrdom"

(in Eusebius, Church

History II.25).

Irenaeus

of Lyons, a native of Asia

Minor and a disciple of Polycarp

of Smyrna (a disciple of St.

John), passed a considerable time in Rome shortly

after the middle of the second century, and then proceeded to Lyons,

where he became bishop in

177; he described the Roman

Church as the most prominent and chief preserver of the Apostolic

tradition, as "the greatest and most ancient church,

known by all, founded and organized at Rome by

the two most glorious Apostles,

Peter and Paul"

(Against

Heresies 3.3; cf. 3.1).

He thus makes use of the universally known and

recognized fact of the Apostolic activity

of Peter and Paul in Rome,

to find therein a proof from tradition against

the heretics.

In his "Hypotyposes" (Eusebius, Church

History IV.14), Clement

of Alexandria, teacher in the catechetical school of

that city from about 190, says on the strength of the tradition of

the presbyters:

"After Peter had announced the Word of God in Rome and

preached the Gospel in the spirit

of God, the multitude of hearers requested Mark, who had long accompanied

Peter on all his journeys, to write down what the Apostles had

preached to them" (see above).

Like Irenaeus, Tertullian appeals,

in his writings against heretics,

to the proof afforded

by the Apostolic labours

of Peter and Paul in Rome of

the truth of ecclesiastical

tradition. In De

Præscriptione 36, he says: "If thou art near Italy,

thou hast Rome where

authority is ever within reach. How fortunate is this Church for

which the Apostles have

poured out their whole teaching with their blood, where Peter has emulated

the Passion of the Lord, where Paul was crowned with

the death of John".

In Scorpiace 15,

he also speaks of Peter's crucifixion. "The budding faith Nero first

made bloody in Rome.

There Peter was girded by another, since he was bound to the cross". As an

illustration that it was immaterial with what water baptism is

administered, he states in his book (On

Baptism 5) that there is "no difference between that with

which John baptized in

the Jordan and

that with which Peter baptized in

the Tiber"; and against Marcion he

appeals to the testimony of the Roman Christians,

"to whom Peter and Paul have

bequeathed the Gospel sealed with their blood" (Against

Marcion 4.5).

The Roman, Caius,

who lived in Rome in

the time of Pope

Zephyrinus (198-217), wrote in his "Dialogue with Proclus"

(in Eusebius, Church

History II.25) directed against the Montanists:

"But I can show the trophies of the Apostles.

If you care to go to the Vatican or

to the road to Ostia,

thou shalt find the trophies of those who have founded this Church".

By the trophies (tropaia) Eusebius understands

the graves of

the Apostles,

but his view is opposed by modern investigators who believe that

the place of execution is

meant. For our purpose it is immaterial which opinion is correct, as the

testimony retains its full value in either case. At any rate the place of execution and burial of

both were close together; St. Peter, who was executed on the Vatican,

received also his burial there. Eusebius also

refers to "the inscription of

the names of Peter and Paul,

which have been preserved to the present day on

the burial-places there" (i.e. at Rome).

There thus existed in Rome an

ancient epigraphic memorial commemorating the death of the Apostles.

The obscure notice in the Muratorian

Fragment ("Lucas optime theofile conprindit quia sub praesentia

eius singula gerebantur sicuti et semote passionem petri evidenter

declarat", ed. Preuschen, Tübingen, 1910, p. 29) also presupposes an

ancient definite tradition concerning

Peter's death in Rome.

The apocryphal Acts

of St. Peter and the Acts

of Sts. Peter and Paul likewise belong to the series of testimonies of

the death of the two Apostles in Rome.

In opposition to this distinct and unanimous testimony of early Christendom, some few Protestant historians have attempted in recent times to set aside the residence and death of Peter at Rome as legendary. These attempts have resulted in complete failure. It was asserted that the tradition concerning Peter's residence in Rome first originated in Ebionite circles, and formed part of the Legend of Simon the Magician, in which Paul is opposed by Peter as a false Apostle under Simon; just as this fight was transplanted to Rome, so also sprang up at an early date the legend of Peter's activity in that capital (thus in Baur, "Paulus", 2nd ed., 245 sqq., followed by Hase and especially Lipsius, "Die quellen der römischen Petrussage", Kiel, 1872). But this hypothesis is proved fundamentally untenable by the whole character and purely local importance of Ebionitism, and is directly refuted by the above genuine and entirely independent testimonies, which are at least as ancient. It has moreover been now entirely abandoned by serious Protestant historians (cf., e.g., Harnack's remarks in "Gesch. der altchristl. Literatur", II, i, 244, n. 2). A more recent attempt was made by Erbes (Zeitschr. fur Kirchengesch., 1901, pp. 1 sqq., 161 sqq.) to demonstrate that St. Peter was martyred at Jerusalem. He appeals to the apocryphal Acts of St. Peter, in which two Romans, Albinus and Agrippa, are mentioned as persecutors of the Apostles. These he identifies with the Albinus, Procurator of Judaea, and successor of Festus and Agrippa II, Prince of Galilee, and thence conciudes that Peter was condemned to death and sacrificed by this procurator at Jerusalem. The untenableness of this hypothesis becomes immediately apparent from the mere fact that our earliest definite testimony concerning Peter's death in Rome far antedates the apocryphal Acts; besides, never throughout the whole range of Christian antiquity has any city other than Rome been designated the place of martyrdom of Sts. Peter and Paul.

Although the fact of St. Peter's activity and death in Rome is so clearly established, we possess no precise information regarding the details of his Roman sojourn. The narratives contained in the apocryphal literature of the second century concerning the supposed strife between Peter and Simon Magus belong to the domain of legend. From the already mentioned statements regarding the origin of the Gospel of St. Mark we may conclude that Peter laboured for a long period in Rome. This conclusion is confirmed by the unanimous voice of tradition which, as early as the second half of the second century, designates the Prince of the Apostles the founder of the Roman Church. It is widely held that Peter paid a first visit to Rome after he had been miraculously liberated from the prison in Jerusalem; that, by "another place", Luke meant Rome, but omitted the name for special reasons. It is not impossible that Peter made a missionary journey to Rome about this time (after 42 A.D.), but such a journey cannot be established with certainty. At any rate, we cannot appeal in support of this theory to the chronological notices in Eusebius and Jerome, since, although these notices extend back to the chronicles of the third century, they are not old traditions, but the result of calculations on the basis of episcopal lists. Into the Roman list of bishops dating from the second century, there was introduced in the third century (as we learn from Eusebius and the "Chronograph of 354") the notice of a twenty-five years' pontificate for St. Peter, but we are unable to trace its origin. This entry consequently affords no ground for the hypothesis of a first visit by St. Peter to Rome after his liberation from prison (about 42). We can therefore admit only the possibility of such an early visit to the capital.

The task of determining the year of St. Peter's death is attended with similar difficulties. In the fourth century, and even in the chronicles of the third, we find two different entries. In the "Chronicle" of Eusebius the thirteenth or fourteenth year of Nero is given as that of the death of Peter and Paul (67-68); this date, accepted by Jerome, is that generally held. The year 67 is also supported by the statement, also accepted by Eusebius and Jerome, that Peter came to Rome under the Emperor Claudius (according to Jerome, in 42), and by the above-mentioned tradition of the twenty-five years' episcopate of Peter (cf. Bartolini, "Sopra l'anno 67 se fosse quello del martirio dei gloriosi Apostoli", Rome, 1868) . A different statement is furnished by the "Chronograph of 354" (ed. Duchesne, "Liber Pontificalis", I, 1 sqq.). This refers St. Peter's arrival in Rome to the year 30, and his death and that of St. Paul to 55.

Duchesne has shown that the dates in the "Chronograph" were inserted in a list of the popes which contains only their names and the duration of their pontificates, and then, on the chronological supposition that the year of Christ's death was 29, the year 30 was inserted as the beginning of Peter's pontificate, and his death referred to 55, on the basis of the twenty-five years' pontificate (op. cit., introd., vi sqq.). This date has however been recently defended by Kellner ("Jesus von Nazareth u. seine Apostel im Rahmen der Zeitgeschichte", Ratisbon, 1908; "Tradition geschichtl. Bearbeitung u. Legende in der Chronologie des apostol. Zeitalters", Bonn, 1909). Other historians have accepted the year 65 (e.g., Bianchini, in his edition of the "Liber Pontificalis" in P.L. CXXVII. 435 sqq.) or 66 (e.g. Foggini, "De romani b. Petri itinere et episcopatu", Florence, 1741; also Tillemont). Harnack endeavoured to establish the year 64 (i.e. the beginning of the Neronian persecution) as that of Peter's death ("Gesch. der altchristl. Lit. bis Eusebius", pt. II, "Die Chronologie", I, 240 sqq.). This date, which had been already supported by Cave, du Pin, and Wieseler, has been accepted by Duchesne (Hist. ancienne de l'église, I, 64). Erbes refers St. Peter's death to 22 Feb., 63, St. Paul's to 64 ("Texte u. Untersuchungen", new series, IV, i, Leipzig, 1900, "Die Todestage der Apostel Petrus u. Paulus u. ihre rom. Denkmaeler"). The date of Peter's death is thus not yet decided; the period between July, 64 (outbreak of the Neronian persecution), and the beginning of 68 (on 9 July Nero fled from Rome and committed suicide) must be left open for the date of his death. The day of his martyrdom is also unknown; 29 June, the accepted day of his feast since the fourth century, cannot be proved to be the day of his death (see below).

Concerning the manner of Peter's death, we possess a tradition — attested to by Tertullian at the end of the second century (see above) and by Origen (in Eusebius, Church History II.1)—that he suffered crucifixion. Origen says: "Peter was crucified at Rome with his head downwards, as he himself had desired to suffer". As the place of execution may be accepted with great probability the Neronian Gardens on the Vatican, since there, according to Tacitus, were enacted in general the gruesome scenes of the Neronian persecution; and in this district, in the vicinity of the Via Cornelia and at the foot of the Vatican Hills, the Prince of the Apostles found his burial place. Of this grave (since the word tropaion was, as already remarked, rightly understood of the tomb) Caius already speaks in the third century. For a time the remains of Peter lay with those of Paul in a vault on the Appian Way at the place ad Catacumbas, where the Church of St. Sebastian (which on its erection in the fourth century was dedicated to the two Apostles) now stands. The remains had probably been brought thither at the beginning of the Valerian persecution in 258, to protect them from the threatened desecration when the Christian burial-places were confiscated. They were later restored to their former resting-place, and Constantine the Great had a magnificent basilica erected over the grave of St. Peter at the foot of the Vatican Hill. This basilica was replaced by the present St. Peter's in the sixteenth century. The vault with the altar built above it (confessio) has been since the fourth century the most highly venerated martyr's shrine in the West. In the substructure of the altar, over the vault which contained the sarcophagus with the remains of St. Peter, a cavity was made. This was closed by a small door in front of the altar. By opening this door the pilgrim could enjoy the great privilege of kneeling directly over the sarcophagus of the Apostle. Keys of this door were given as previous souvenirs (cf. Gregory of Tours, "De gloria martyrum", I, xxviii).

The memory of St. Peter is also closely associated with the Catacomb of St. Priscilla on the Via Salaria. According to a tradition, current in later Christian antiquity, St. Peter here instructed the faithful and administered baptism. This tradition seems to have been based on still earlier monumental testimonies. The catacomb is situated under the garden of a villa of the ancient Christian and senatorial family, the Acilii Glabriones, and its foundation extends back to the end of the first century; and since Acilius Glabrio, consul in 91, was condemned to death under Domitian as a Christian, it is quite possible that the Christian faith of the family extended back to Apostolic times, and that the Prince of the Apostles had been given hospitable reception in their house during his residence at Rome. The relations between Peter and Pudens whose house stood on the site of the present titular church of Pudens (now Santa Pudentiana) seem to rest rather on a legend.

Concerning the Epistles of St. Peter, see EPISTLES

OF SAINT PETER; concerning the various apocrypha bearing

the name of Peter, especially the Apocalypse and the Gospel of St. Peter,

see APOCRYPHA.

The apocryphal sermon

of Peter (kerygma), dating from

the second half of the second century, was probably a collection of

supposed sermons by

the Apostle;

several fragments are preserved by Clement

of Alexandria (cf. Dobschuts, "Das Kerygma Petri kritisch

untersucht" in "Texte u. Untersuchungen", XI, i, Leipzig, 1893).

Feasts of St. Peter

As early as the fourth century a feast was

celebrated in memory of

Sts. Peter and Paul on

the same day, although the day was not the same in the East as

in Rome.

The Syrian Martyrology of

the end of the fourth century, which is an excerpt from

a Greek catalogue of saints from Asia

Minor, gives the following feasts in

connexion with Christmas (25

Dec.): 26 Dec., St.

Stephen; 27 Dec., Sts. James and John; 28 Dec., Sts. Peter

and Paul.

In St.

Gregory of Nyssa's panegyric on St.

Basil we are also informed that these feasts of

the Apostles and St.

Stephen follow immediately after Christmas.

The Armenians celebrated

the feast also

on 27 Dec.; the Nestorians on

the second Friday after the Epiphany.

It is evident that 28 (27) Dec. was (like 26 Dec. for St.

Stephen) arbitrarily selected, no tradition concerning

the date of

the saints' death

being forthcoming. The chief feast of

Sts. Peter and Paul was

kept in Rome on

29 June as early as the third or fourth century. The list of feasts of

the martyrs in

the Chronograph of Philocalus appends this notice to the date — "III. Kal.

Jul. Petri in Catacumbas et Pauli Ostiense Tusco et Basso

Cose." (=the year 258) . The "Martyrologium Hieronyminanum"

has, in the Berne manuscript,

the following notice for 29 June: "Romae via Aurelia natale sanctorum

Apostolorum Petri et Pauli, Petri in Vaticano, Pauli in via Ostiensi, utrumque

in catacumbas, passi sub Nerone, Basso et Tusco consulibus" (ed. de

Rossi-Duchesne, 84).

The date 258 in the notices shows that from this year the memory of the two Apostles was celebrated on 29 June in the Via Appia ad Catacumbas (near San Sebastiano fuori le mura), because on this date the remains of the Apostles were translated thither (see above). Later, perhaps on the building of the church over the graves on the Vatican and in the Via Ostiensis, the remains were restored to their former resting-place: Peter's to the Vatican Basilica and Paul's to the church on the Via Ostiensis. In the place Ad Catacumbas a church was also built as early as the fourth century in honour of the two Apostles. From 258 their principal feast was kept on 29 June, on which date solemn Divine Service was held in the above-mentioned three churches from ancient times (Duchesne, "Origines du culte chretien", 5th ed., Paris, 1909, 271 sqq., 283 sqq.; Urbain, "Ein Martyrologium der christl. Gemeinde zu Rom an Anfang des 5. Jahrh.", Leipzig, 1901, 169 sqq.; Kellner, "Heortologie", 3rd ed., Freiburg, 1911, 210 sqq.). Legend sought to explain the temporary occupation by the Apostles of the grave Ad Catacumbas by supposing that, shortly after their death, the Oriental Christians wished to steal their bodies and bring them to the East. This whole story is evidently a product of popular legend. (Concerning the Feast of the Chair of Peter, see CHAIR OF PETER.)

A third Roman feast of

the Apostles takes

place on 1 August: the feast of

St. Peter's Chains. This feast was

originally the dedication feast of

the church of

the Apostle,

erected on the Esquiline Hill in the fourth century. A titular priest of

the church,

Philippus, was papal

legate at the Council

of Ephesus in 431. The church was

rebuilt by Sixtus

III (432-40) at the expense of the Byzantine imperial family.

Either the solemn consecration took

place on 1 August, or this was the day of dedication of

the earlier church.

Perhaps this day was selected to replace the heathen festivities

which took place on 1 August. In this church,

which is still standing (S. Pietro in Vincoli), were probably preserved from

the fourth century St. Peter's chains, which were greatly venerated,

small filings from the chains being regarded as precious relics.

The church thus

early received the name in Vinculis, and the feast of

1 August became the feast of

St. Peter's Chains (Duchesne, op. cit., 286 sqq.; Kellner, loc. cit., 216

sqq.). The memory of both Peter and Paul was

later associated also with two places of ancient Rome:

the Via Sacra, outside the Forum, where the magician

Simon was said to have been hurled down at the prayer of

Peter and the prison Tullianum,

or Carcer Mamertinus, where the Apostles were

supposed to have been kept until their execution.

At both these places, also, shrines of the Apostles were

erected, and that of the Mamertine

Prison still remains in almost its original form from the early

Roman time.

These local commemorations of the Apostles are

based on legends, and no special celebrations are held in the two churches.

It is, however, not impossible that Peter and Paul were

actually confined in the chief prison in Rome at

the fort of the Capitol, of which the present Carcer Mamertinus is a

remnant.

Representations of St. Peter

The oldest extant is the bronze medallion with the heads of the Apostles; this dates from the end of the second or the beginning of the third century, and is preserved in the Christian Museum of the Vatican Library. Peter has a strong, roundish head, prominent jaw-bones, a receding forehead, thick, curly hair and beard. (See illustration in CATACOMBS.) The features are so individual that it partakes of the nature of a portrait. This type is also found in two representations of St. Peter in a chamber of the Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus, dating from the second half of the third century (Wilpert, "Die Malerein der Katakomben Rom", plates 94 and 96). In the paintings of the catacombs Sts. Peter and Paul frequently appear as interceders and advocates for the dead in the representations of the Last Judgment (Wilpert, 390 sqq.), and as introducing an Orante (a praying figure representing the dead) into Paradise.

In the numerous representations of Christ in the midst of His Apostles, which occur in the paintings of the catacombs and carved on sarcophagi, Peter and Paul always occupy the places of honour on the right and left of the Saviour. In the mosaics of the Roman basilicas, dating from the fourth to the ninth centuries, Christ appears as the central figure, with Sts. Peter and Paul on His right and left, and besides these the saints especially venerated in the particular church. On sarcophagi and other memorials appear scenes from the life of St. Peter: his walking on Lake Genesareth, when Christ summoned him from the boat; the prophecy of his denial; the washing of his feet; the raising of Tabitha from the dead; the capture of Peter and the conducting of him to the place of execution. On two gilt glasses he is represented as Moses drawing water from the rock with his staff; the name Peter under the scene shows that he is regarded as the guide of the people of God in the New Testament.

Particularly frequent in the period between the fourth and sixth centuries is the scene of the delivery of the Law to Peter, which occurs on various kinds of monuments. Christ hands St. Peter a folded or open scroll, on which is often the inscription Lex Domini (Law of the Lord) or Dominus legem dat (The Lord gives the law). In the mausoleum of Constantina at Rome (S. Costanza, in the Via Nomentana) this scene is given as a pendant to the delivery of the Law to Moses. In representations on fifth-century sarcophagi the Lord presents to Peter (instead of the scroll) the keys. In carvings of the fourth century Peter often bears a staff in his hand (after the fifth century, a cross with a long shaft, carried by the Apostle on his shoulder), as a kind of sceptre indicative of Peter's office. From the end of the sixth century this is replaced by the keys (usually two, but sometimes three), which henceforth became the attribute of Peter. Even the renowned and greatly venerated bronze statue in St. Peter's possesses them; this, the best-known representation of the Apostle, dates from the last period of Christian antiquity (Grisar, "Analecta romana", I, Rome, 1899, 627 sqq.).

Sources

BIRKS Studies of the Life and character of St. Peter (LONDON, 1887), TAYLOR, Peter the Apostle, new ed. by BURNET AND ISBISTER (London, 1900); BARNES, St. Peter in Rome and his Tomb on the Vatican Hill (London, 1900): LIGHTFOOT, Apostolic Fathers, 2nd ed., pt. 1, VII. (London, 1890), 481sq., St. Peter in Rome ; FOUARD Les origines de l'Église: St. Pierre et Les premières années du christianisme (3rd ed., Paris 1893); FILLION, Saint Pierre (2nd ed Paris, 1906); collection Les Saints; RAMBAUD, Histoire de Saint Pierre apôtre (Bordeaux, 1900); GUIRAUD, La venue de St Pierre à Rome in Questions d'hist. et d'archéol. chrét. (Paris, 1906); FOGGINI, De romano D. Petr; itinere et episcopatu (Florence, 1741); RINIERI, S. Pietro in Roma ed i primi papi secundo i piu vetusti cataloghi della chiesa Romana (Turin, 1909); PAGANI, Il cristianesimo in Roma prima dei gloriosi apostoli Pietro a Paolo, e sulle diverse venute de' principi degli apostoli in Roma (Rome, 1906); POLIDORI, Apostolato di S. Pietro in Roma in Civiltà Cattolica, series 18, IX (Rome, 1903), 141 sq.; MARUCCHI, Le memorie degli apostoli Pietro e Paolo in Roma (2nd ed., Rome, 1903); LECLER, De Romano S. Petri episcopatu (Louvain, 1888); SCHMID, Petrus in Rome oder Aufenthalt, Episkopat und Tod in Rom (Breslau, 1889); KNELLER, St. Petrus, Bischof von Rom in Zeitschrift f. kath. Theol., XXVI (1902), 33 sq., 225sq.; MARQUARDT, Simon Petrus als Mittel und Ausgangspunkt der christlichen Urkirche (Kempten, 1906); GRISAR, Le tombe apostoliche al Vaticano ed alla via Ostiense in Analecta Romana, I (Rome, 1899), sq.

Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 2 Jul. 2017 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11744a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by Gerard Haffner.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. February

1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal

Farley, Archbishop of New York.