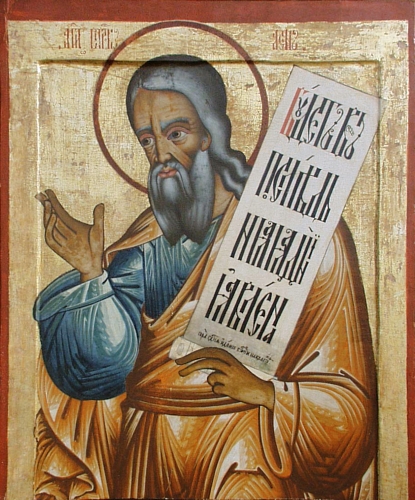

Saint Isaïe

prophète

de l'Ancien Testament (8ème s. av JC.)

Il annonça

le Christ, Messie et salut des nations. Il reçut sa vocation dans le Temple de

Jérusalem où il eut la révélation de la sainteté de Dieu et de l'indignité de

l'homme. Grand prophète messianique, il annonça la naissance mystérieuse de

l'Emmanuel, descendant de David, qui ferait régner la paix et la justice et

répandrait la connaissance de Dieu.

Lire dans la Bible, le Livre d'Isaïe, aelf.

Les Églises d'Orient fêtent le 9 mai celui qui prophétisa la Passion du

Christ, "le serviteur souffrant", et la virginité de la Sainte Mère

de Dieu, la toujours Vierge Marie. L'Église d'Occident le fête le 6 juillet.

Commémoraison de saint Isaïe, prophète, qui, au VIIIe siècle avant

le Christ, aux jours d’Ozias, de Jotham, d’Achaz et d’Ézéchias, rois de Juda,

fut envoyé pour révéler au peuple infidèle et pécheur un Seigneur fidèle et

sauveur, qui accomplirait la promesse jurée par Dieu à David. Selon la

tradition, il serait mort martyr, en Judée, sous le roi Manassé.

Martyrologe romain

Que sait-on d'Isaïe ?

Quand vivait Isaïe ? Comment vivait-on à son époque ? Quels

furent les grands événements ? Quel est le cœur de son message ? Voici

quelques éléments de réponse…

• Que sait-on d'Isaïe ? Quand est-il né ?

La date de la naissance d'Isaïe nous est inconnue. Mais on connaît la

date à laquelle il exerça son activité de prophète. C'était à peu près entre

740 et 700 avant Jésus Christ. On peut en déduire qu’il naquit vers 765-760.

Nous ne savons pas grand-chose de sa vie privée. Son père s'appelait Amoç

(Isaïe, 1,1). Isaïe était marié. Dans ses écrits, sa femme reçoit le nom de

« prophétesse » (8,3). Deux de ses enfants y sont aussi désignés par

des noms à portée symbolique : Shéar-Yashouv, ce qui veut dire « Un reste

reviendra » (ou se convertira) et Maher-Shalal-Hash-Baz, ce qui veut dire

« Proche est le pillage, imminente la déprédation » (7,3; 8,3). Ces

noms serviront à exprimer le message du prophète à certains moments.

Isaïe parle très peu de lui, de ses sentiments. Une fois seulement, il

donne libre cours à son désarroi face au comportement de ses contemporains

(22,4). À deux reprises, on le voit aussi se démarquer de ses contemporains

(7,13; 8, 11-18).

• Quelles étaient les grandes puissances de l'époque ?

Deux puissances occupent le devant de la scène : l'Assyrie et l'Égypte.

L'Assyrie connaît un renouveau et une forte expansion à partir de 745, grâce à

1'arrivée sur le trône d'un roi qui fera beaucoup parler de lui :

Tiglat-Piléser (ou Téglat-Phalasar) III. L'Égypte, elle, est alors plongée dans

une situation presque anarchique qui durera jusqu'à la fin du 8° siècle.

Cependant, pour les petits royaumes de Syrie et de Palestine, elle continue à

être une puissance avec laquelle il faut compter. C'est vers elle qu'on se

tournera, en vain d'ailleurs, pour chercher de l'aide contre les Assyriens.

Quant à la Babylonie, elle sera annexée par Tiglat-Piléser III. Malgré quelques

tentatives pour prendre la tête d'un vaste mouvement anti-assyrien incluant

même le royaume de Juda (Is 39), elle restera très marginalisée.

• Connaît-on la situation intérieure du royaume de Juda où vivait Isaïe

? Et le royaume du Nord ?

La situation intérieure du royaume de Juda évolue au long de la vie du

prophète. L'enfance et la jeunesse d'Isaïe se déroulent à un moment de grande

prospérité. À partir de 735, cette prospérité est fortement limitée puisque

Jérusalem se retrouve en situation de vassale de l'Assyrie. La plus grande

partie du ministère prophétique d'Isaïe se déroule donc dans ce cadre de

vassalité. Les tributs à payer aux Assyriens réduisent considérablement le

niveau de vie des gens, car il faut bien trouver l'argent quelque part. À

partir de 701, la situation est encore plus catastrophique à la suite de la

révolte du roi Ézékias : il doit payer un lourd tribut et perd une partie du

territoire national (2 Rois 18,14-16).

Dans le Royaume du Nord, la situation est la même jusqu'à l'arrivée des

Assyriens. Entre 734 et 722, la vie est précaire à cause de la perte d'une très

grande partie du territoire, à cause aussi de la déportation de bon nombre

d'habitants et du lourd tribut à payer aux Assyriens. Le Royaume du Nord

disparaît en 722.

• Isaïe avait-il des liens avec les hommes politiques ? Quelle était

l'importance d'un roi à cette époque ? Un prophète pouvait-il facilement le

contredire?

Isaïe fréquentait certainement la cour royale. Il devait faire partie de

l'aristocratie du royaume. Certains textes démontrent les liens étroits du

prophète avec la cour, vu l'aisance avec laquelle il s'adresse au roi et à

certains fonctionnaires, vu aussi les consultations dont il est l'objet (Is

7,1-7; 22,15-25; 37,1-7; 38-39). En outre, il est fort probable qu'Isaïe ait

été le prophète officiel du roi Ézékias, ce qui expliquerait, entre autres, sa

fréquentation de la cour.

Le roi à l'époque avait une importance capitale. Dans la mentalité du

temps, il constituait la clé de voûte de l'ensemble du système socio-religieux.

Il était le « fils » de Dieu, chargé de rendre la justice, de

conduire la guerre, de gagner la paix et d'apporter le bien-être au peuple. Il

avait aussi l'autorité suprême sur le temple, les prêtres étant ses fonctionnaires.

Le prophète qui critiquait le roi s'attirait inévitablement les foudres

du pouvoir, car il mettait en cause le fonctionnement de ce bel édifice social,

voire le système lui-même. Il suffit de lire Amos 7,10-17 pour s'en rendre

compte. Mais c'est là justement que les prophètes reconnus comme authentiques

représentants de la parole de Dieu donnent une des preuves de leur

« véracité ». Ils refusent d'identifier la religion d'Israël avec la

religion du roi; ils critiquent celui-ci en conséquence. C'est une des caractéristiques

essentielles du prophétisme en Israël. Isaïe croyait fortement en la valeur de

la monarchie comme médiation de salut pour Israël, mais cela ne l'empêchait pas

de critiquer rudement le roi et la cour.

• Y avait-il des riches, des pauvres ? Les classes sociales

étaient-elles très marquées ?

Amos, Osée, Isaïe et Michée, tous les quatre prophètes du 8° siècle,

critiquent âprement la violence et l'oppression dont sont victimes les petits

et les pauvres. La situation sociale s'est extrêmement dégradée à cette époque

et la différence entre classes s'est donc renforcée. La critique sociale

d'Isaïe, comme celle des trois autres prophètes cités, constitue un élément

essentiel du ministère prophétique. La critique se porte aussi sur la pratique

cultuelle, étant entendu que les prophètes ne délient jamais la pratique du

culte de celle de la justice, celle-ci étant à leurs yeux essentielle.

• Est-il possible de résumer le cœur de son message en quelques lignes ?

Isaïe est un homme de son temps qui, en tant qu'envoyé du Dieu d'Israël,

le Saint, va intervenir dans tous les domaines de la vie de son peuple. Son

époque étant très mouvementée politiquement et socialement, il va dénoncer

constamment le désir de la cour et du peuple de conduire leur vie en marge du

plan du Dieu d'Israël : alliances politiques pour sauver le pouvoir (30,1-8),

oppression des pauvres pour s'enrichir soi-même (1,21-28), tout cela accompagné

d'un culte « des lèvres » (1,10-20). On pourrait citer bien des

textes ! Pour Isaïe, la vie du peuple et des institutions qui sont à son

service, roi, prophètes, sages, culte, n'a de sens qu'enracinée dans le Saint

d'Israël qui a choisi Sion, son roi et son temple, pourvu que tous répondent

par une foi sans concessions.

• Quel langage le prophète utilisait-il ?

Tout est bon pour faire passer le message prophétique. Chaque prophète a

ses propres caractéristiques, mais on trouve souvent des oracles de jugement,

avec le couple « accusation/sentence » (5,8-10; 30,15-17), des

oracles de salut (7,3-9), des paraboles (5,17; 28,23-29), des lamentations

(29,1-8), des poèmes de toutes sortes (9,1-6; 11,1-9), des actions symboliques

(8,1-4; 20,1-6), des visions (6). Si les premiers prophètes avaient surtout une

activité orale, ils commencèrent assez vite à mettre par écrit certains oracles

(Is 8,16; 30,8), créant ensuite les premières collections d’oracles. Il n'est

pas impossible que plus tard, Ézéchiel par exemple, ait écrit directement ses

oracles sans passer par une proclamation orale préalable de son message.

© SBEV. Jésus Asurmendi

Note :

Isaïe : un livre... trois auteurs !

Le livre d’Isaïe est composé de trois parties rédigées à des époques

différences et par des auteurs différents.

Les chapitres 1 à 39 sont en grande partie l'œuvre d'Isaïe lui-même, et

c'est pourquoi on parle du “ livre d'Isaïe ” pour l’ensemble du livre. Mais,

plus tard, de lointains disciples se réclameront de lui, et leurs œuvres seront

ajoutées à la sienne : tout d’abord un disciple du temps de l'Exil, auteur des

chapitres 40 à 55, puis un autre prophète anonyme, après l'Exil, auteur des

derniers chapitres (56 à 66).

Le premier auteur (ch. 1 à 39) est donc Isaïe lui-même. C’est le “

premier Isaïe ”, ou “ proto-Isaïe ” (du grec prôtos, premier). Pour

désigner le second auteur (ch. 40–55) on utilise l’expression de “ second-Isaïe

”, ou “ deutéro-Isaïe ” (du grec, deutéro “ deuxième ”), et pour le

dernier rédacteur (ch. 56–66), les spécialistes parlent de “ troisième Isaïe

”, ou “ trito-Isaïe ” (du grec trito “ troisième ”).

• Les oracles du premier Isaïe se trouvent essentiellement dans les

chapitres 1-12 (oracles sur Juda et Jérusalem); 13-12 (oracles sur les

Nations); et 28-33 (oracles sur Samarie et Jérusalem).

• Le second Isaïe s’adresse aux exilés et à Jérusalem durant l’exil

(entre 5857 et 538), pour leur annoncer la libération prochaine et le retour.

• Les oracles du

troisième Isaïe veulent réconforter le Communquté juive rentrée en Judée après

l’Exil et qui doit faire face à bien des difficultés et des déceptions.

Saint JÉRÔME, « SUR LA TRADUCTION DU PROPHÈTE ISAÏE.

À PAULA ET À EUSTOCHIA »

Il ne faut pas

s'imaginer que les livres des Prophètes sont écrits en vers dans l'original hébreu,

comme le livre des Psaumes et les livres de Salomon, parce qu'on les voit

divisés en versets dans la traduction latine. Le traducteur a cru être agréable

au public en distinguant cette nouvelle traduction par un ordre nouveau, comme

on a fait autrefois pour les ouvrages de Démosthène et de Cicéron.

Je me suis livré à une

étude particulière d'Isaïe, que j'appellerai le prince des prophètes, non à

cause de sa haute naissance, mais à cause de la beauté de son génie, de l'éclat

et de la force de son éloquence. Ses idées sont grandes et magnifiques, ses

pensées sont fortes et élevées, ses images sont nobles et majestueuses, et son

style est brillant et énergique.

Aussi a-t-il été difficile de conserver dans la

traduction toutes les beautés et toute la noblesse de ses expressions. D'un

autre côté, il est bon de prévenir qu'il est tout aussi bien un évangéliste

qu'un prophète ; car il nous révèle d'une manière si claire et si frappante

tous les mystères de Jésus-Christ et de l'Eglise, qu'il semble plutôt raconter

des choses passées que prédire des choses à venir. Et je pense que c'est ce qui

a engagé les Septante , comme il sera facile de le remarquer en lisant cette

traduction, à omettre plusieurs passages et à cacher aux païens les mystères de

la religion judaïque, de peur de donner les « choses saintes aux chiens » et de

jeter les perles devant les pourceaux.

Je sais au reste

combien les prophètes sont difficiles à expliquer et je n'ignore pas que je

m'expose à la censure de ceux qui, par une secrète envie, méprisent tout ce qui

parait leur être supérieur. Je m'attends donc à me voir livré à toutes les

attaques de l’envie et de la médisance. Mais comme les Grecs, qui néanmoins se

servent de la version des Septante, ne laissent pas que de consulter les traductions

d'Aquila, de Symmaque et de Théodotien, soit pour profiter de leurs lumières,

soit pour mieux entendre les Septante en comparant toutes ces versions avec la

leur, je prie ces lecteurs difficiles qui ne trouvent rien à leur goût de me

permettre d'ajouter encore une traduction à celles que l'on a déjà données au

public, et je les conjure de prendre la peine de la lire avant que de la

mépriser, de peur qu'on ne les accuse de ta condamner plutôt par prévention et

par caprice que par raison et avec connaissance de cause.

Mais je reviens à

Isaïe. Ce prophète a paru dans Jérusalem et dans la Judée avant la captivité

des dix tribus. Il prédit tantôt en général, tantôt séparément, tout ce qui

doit arriver aux deux royaumes de Juda et d'Israël. On dirait qu'il est entré

dans le secret des desseins de la sagesse divine, et que Dieu n'a rien eu de

caché pour lui; car, bien qu'il semble n'avoir en vue que les affaires de son

temps et le rétablissement des Juifs après la captivité de Babylone , il est

cependant certain que sa grande affaire est de nous indiquer la vocation des

gentils et l'avènement de Jésus-Christ. Comme ce divin Sauveur est l'unique

objet de votre affection, je vous supplie aussi, mesdames, de le prier, avec

une ardeur égale à votre amour, de me tenir compte un jour des chagrins et des

ennuis que me font maintenant éprouver mes ennemis, qui ne se fatiguent ni de

m'attaquer, ni de me diffamer de toutes les manières; car notre Seigneur sait

bien que je ne me suis appliqué avec tant de soin et de travail à l'étude d'une

langue étrangère que pour empêcher les Juifs d'insulter plus longtemps à son

Eglise, et de lui reprocher que tout est corrompu et défiguré dans nos saintes Écritures.

Isaias (Isaiah), Prophet (RM)

Died c. 681 BC. Isaiah is the great poet and believer of the Old Testament, and

one of the four major prophets of the Old Testament. He lived at a time when

the people of Israel had settled in Canaan; David and Solomon had formed the

Hebrew religion, the temple had been built and Josiah had just ended a long and

useful reign.

In 740 BC, the year of Josiah's death, Isaiah had a vision of the

Lord sitting on a throne surrounded by seraphim. Each had six wings: "And

one cried to another, and said, 'Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the

whole earth is full of His glory"--words which today form part of the

Mass. The God of Isaiah was a God of Holiness, and the beginnings of his

vocation were marked by majesty, piety, and grandeur.

Tradition tells us that Isaiah was sawn

in two by order of King Manassas of Judah, and buried under an oak tree. His

tomb was still venerated in the 5th century AD (Benedictines).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0706.shtml

Isaias

Among the writers whom the Hebrew Bible styles the "Latter Prophets" foremost stands "Isaias, the holy prophet . . . the great prophet, and faithful in the sight of God" (Eccliasticus 48:23-25).

Life

The book of Isaias

First Isaias

Second Isaias

Appreciation of the work of Isaias

Sources

Souvay, Charles. "Isaias."

The

Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 12 Jul. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08179b.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by WGKofron. With thanks to St. Mary's Church, Akron, Ohio.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08179b.htm

Entre la nuit et l’aurore, Manuscrit (Constantinople, Xe siècle) dit Psautier de Paris.

Folio

435 verso, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Mss., Grec 139)

Isaias

Among the writers whom the Hebrew Bible styles the "Latter Prophets" foremost stands "Isaias, the holy prophet . . . the great prophet, and faithful in the sight of God" (Eccliasticus 48:23-25).

Life

The name Isaias signifies "Yahweh

is salvation". It assumes two different forms

in the Hebrew Bible: for in the

text of the Book of Isaias

and in the historical writings

of the Old Testament, for example in 2 Kings 19:2; 2 Chronicles 26:22; 32:20-32, it is read Yeshá'yahu,

whereas the collection of the Prophet's

utterances is entitled Yeshá'yah, in

Greek 'Esaías, and in Latin

usually Isaias, but sometimes Esaias.

Four other persons of the same name are mentioned in the Old Testament (Ezra 8:7; 8:19; Nehemiah 11:7; 1 Chronicles 26:25); while the names Jesaia (1 Chronicles 25:15), Jeseias (1 Chronicles 3:21; 25:3) may be regarded as mere variants. From the Prophet

himself (i, 1; ii, 1) we learn that he was the son of Amos.

Owing to the similarity between Latin

and Greek forms of this name and

that of the Shepherd-Prophet of Thecue,

some Fathers mistook the Prophet

Amos for the father of Isaias.

St. Jerome in the preface to his

"Commentary on Amos" (P.L., XXV, 989) points out this error. Of Isaias's ancestry we know nothing; but several passages of his prophecies

(iii, 1-17, 24; iv, 1; viii, 2; xxxi, 16) lead us to believe

that he belonged to one of the best families of Jerusalem. A Jewish

tradition recorded in the Talmud

(Tr. Megilla, 10b.) held him to

be a nephew of King Amasias. As to the exact time

of the Prophet's birth we lack

definite data; yet he is believed to have been about twenty years of age when

he began his public ministry. He was a citizen, perhaps a native, of Jerusalem. His writings give unmistakable signs

of high culture. From his prophecies

(vii and viii) we learn that he married

a woman whom he styles "the prophetess" and that he had two sons, She'ar-Yashub

and Maher-shalal-hash-baz. Nothing whatever indicates that he was twice married

as some fancy on the gratuitous and indefensible supposition that the 'almah of vii, 14, was his wife.

The prophetical

ministry of Isaias

lasted wellnigh half a century, from the closing year of Ozias,

King of Juda, possibly up to

that of Manasses. This period

was one of great prophetical

activity. Israel and Juda

indeed were in sore need of guidance. After the death of Jeroboam

II revolution followed upon revolution and the northern

kingdom had sunk rapidly into an abject vassalage to the Assyrians. The petty nations of the West,

however, recovering from the severe blows received in the beginning of the

eighth century, were again manifesting aspirations

of independence. Soon Theglathphalasar III marched his armies towards Syria; heavy tributes were levied and utter ruin

threatened on those who would show any hesitation to pay. In 725 Osee,

the last King of Samaria, fell miserably under the onslaught

of Salmanasar IV, and three years later Samaria

succumbed to the hands of the Assyrians. In the meantime the Kingdom

of Juda hardly fared better. A

long period of peace had enervated characters, and the young, inexperienced,

and unprincipled Achaz was no

match for the Syro-Israelite

coalition which confronted him. Panic-stricken

he, in spite of the remonstrances of Isaias, resolved to appeal

to Theglathphalasar. The help of Assyria was secured, but the independence of Juda

was thereby practically forfeited. In order to explain clearly the political

situation to which so many allusions are made in Isaias's writings

there is here subjoined a brief chronological

sketch of the period: 745, Theglathphalasar III, king of Assyria; Azarias (A. V. Uzziah),

of Juda; Manahem

(A. V. Menahem) of Samaria; and Sua of Egypt; 740, death of Azarias; Joatham (A. V. Jotham),

king of Juda; capture of Arphad

(A. V. Arpad) by

Theglathphalasar III (Isaiah 10:9); 738, campaign of Theglathphalasar against Syria; capture of Calano (A. V. Calno) and Emath (A.

V. Hamath); heavy tribute

imposed upon Manahem (2 Kings 15:19-20); victorious wars of Joatham against the Ammonites (2 Chronicles 27:4-6); 736, Manahem

succeeded by Phaceia (A. V.

Pekahiah); 735, Joatham succeeded by Achaz

(2 Kings 16:1); Phaceia

replaced by Phacee (A. V. Pekah), son of Remelia (A. V. Remaliah), one of his captains;

Jerusalem besieged by Phacee in alliance with

Rasin (A. V. Rezin), king of Syria (2 Kings 16:5; Isaiah 7:1-2); 734, Theglathphalasar, replying to Achaz'

request for aid, marches against Syria and Israel, takes several cities of North and East

Israel (2 Kings 15:29), and banishes their inhabitants;

the Assyrian allies devastate

part of the territory of Juda

and Jerusalem; Phacee slain

during a revolution in Samaria and succeeded by Osee

(A. V. Hoshea); 733, unsuccessful expeditions of Achaz

against Edom (2 Chronicles 28:17) and the Philistines (20); 732, campaign of Theglathphalasar

against Damascus; Rasin besieged

in his capital, captured, and slain;

Achaz goes to Damascus

to pay homage to the Assyrian

ruler (2 Kings 16:10-19); 727, death of Achaz;

accession of Ezechias

(2 Kings 18:1); in Assyria

Salmanasar IV succeeds Theglathphalasar III, 726, campaign of Salmanasar

against Osee (2 Kings 17:3); 725, Osee

makes alliance with Sua, king of Egypt (2 Kings 17:4); second campaign of Salmanasar IV, resulting

in the capture and deportation of Osee

(2 Kings 17:4); beginning of the siege of Samaria; 722, Sargon succeeds Salmanasar IV in Assyria;

capture of Samaria by Sargon; 720, defeat of Egyptian army at Raphia

by Sargon; 717, Charcamis, the Hittite

stronghold on the Euphrates, falls into the hands of Sargon (Isaiah 10:8); 713, sickness of Ezechias

(2 Kings 20:1-11; Isaiah 38); embassy from Merodach Baladan to Ezechias

(2 Kings 20:12-13; Isaiah 39); 711, invasion of Western Palestine by

Sargon; siege and capture of Azotus

(A. V. Ashdod; Isaiah 20); 709, Sargon defeats Merodach Baladan, seizes

Babylon, and assumes title of

king of Babylon; 705, death of

Sargon; accession of

Sennacherib; 701, expedition of Sennacherib against Egypt; defeat of latter at Elteqeh; capture of Accaron

(A. V. Ekron); siege of Lachis; Ezechias's

embassy; the conditions laid

down by Sennacherib being found too hard the king of Juda

prepares to resist the Assyrians; destruction of part of the Assyrian army; hurried retreat

of the rest (2 Kings 18; Isaiah 36:37); 698, Ezechias

is succeeded by his son Manasses.

The wars of the ninth century and the peaceful security

following them produced their effects in the latter part of the next century.

Cities sprang up; new pursuits, although affording opportunities of easy wealth,

brought about also an increase of poverty.

The contrast between class and class became daily more marked, and the poor

were oppressed by the rich with

the connivance of the judges. A social

state founded on iniquity is

doomed. But as Israel's social

corruption was greater than Juda's,

Israel was expected to succumb first. Greater

likewise was her religious

corruption. Not only did idolatrous worship

prevail there to the end, but we know from Osee

what gross abuses and shameful practices obtained in Samaria and throughout the kingdom,

whereas the religion of the

people of Juda on the whole

seems to have been a little better. We know, however, as regards these, that at the very time

of Isaias certain forms

of idolatrous worship,

like that of Nohestan and of Moloch, probably that also of Tammur and of

the "host of heaven",

were going on in the open or in secret.

Commentators are at

variance as to when Isaias was called to the prophetical

office. Some think that previous to the vision

related in vi, 1, he had received communications from heaven. St. Jerome in his commentary

on the passage holds that chapters

i-v ought to be attributed to the last years of King Ozias,

then ch. vi would commence a new series begun in the year of the death of that

prince (740 B.C.; P.L., XXIV, 91; cf. St. Gregory Nazianzen, Orat. ix; P.G., XXXV, 820). It is

more commonly held, however, that ch. vi refers to the first calling of the Prophet;

St. Jerome himself, in a letter to Pope Damasus seems to adopt

this view (P.L., XXII, 371; cf. Hesychius

"In Is.", P.G. XCIII, 1372), and St. John Chrysostom, commenting

upon Isaiah 6:5, very aptly contrasts the

promptness of the Prophet with

the tergiversations of Moses

and Jeremias. On the other hand,

since no prophecies appear to be

later than 701 B.C., it is doubtful if Isaias saw the reign of Manasses

at all; still a very old and widespread tradition,

echoed by the Mishna (Tr. Yebamoth, 49b; cf. Sanhedr.,

103b), has it that the Prophet

survived Ezechias and was slain

in the persecution of Manasses

(2 Kings 21:16). This prince had him convicted of blasphemy, because he had dared say: "I saw the Lord

sitting upon a throne" (vi,

1), a pretension in conflict with God's own assertion in Exodus 33:20: "Man shall not see me and live".

He was accused, moreover, of having predicted the ruin of Jerusalem and called the holy

city and the people of Juda by

the accursed names of Sodom

and Gomorrah. According to the

"Ascension of Isaias", the Prophet's

martyrdom consisted in being sawed asunder. Tradition

shows this to have been unhesitatingly believed.

The Targum on 2 Kings 21:6, admits it; it is preserved in two treatises

of the Talmud (Yebamoth, 49b; Sanhedr.,

103b); St. Justin (Dialogue with Trypho 120), and many of the Fathers

adopted it, taking as

unmistakable allusions to Isaias those words of the Hebrews 11:37, "they (the ancients) were cut

asunder" (cf. Tertullian, "De patient.", xiv;

P.L., I, 1270; Orig., "In

Is., Hom." I, 5, P.G., XIII, 223; "In Matt.", x, 18, P.G., XIII,

882; "In Matt.", Ser. 28, P.G., XIII, 1637; "Epist. ad Jul. Afr.",

ix, P.G., XI, 65; St. Jerome, "In Is.", lvii, 1, P.L.,

XXIV, 546-548; etc.). However, little trust

should be put in the strange details mentioned in the "De Vit. Prophet."

of pseudo-Epiphanius (P.G., XLIII, 397, 419). The date

of the Prophet's demise is not

known. The Roman Martyrology

commemorates Isaias on

6 July. His tomb is believed to have been in Paneas

in Northern Palestine, whence his relics were taken to Constantinople

in A.D. 442.

The literary

activity of Isaias is attested by the canonical

book which bears his name; moreover allusion is made in 2 Chronicles 26:22, to "Acts of Ozias first and

last . . . written by Isaias, the son of Amos, the prophet". Another

passage of the same book informs us that "the rest of the acts

of Ezechias and his mercies, are

written in the Vision of Isaias,

son of Amos, the prophet",

in the Book of the Kings

of Juda and Israel. Such at least is the reading of the Massoretic Bible,

but its text here, if we may judge

from the variants of the Greek

and St. Jerome, is somewhat corrupt. Most commentators

who believe the passage to be authentic

think that the writer refers to Isaiah 36-39. We must finally mention the "Ascension of Isaias",

at one time attributed to the Prophet,

but never admitted into the Canon.

The book of Isaias

The canonical

Book of Isaias is made

up of two distinct collections of

discourses, the one (chapters 1-35) called sometimes the "First Isaias";

the other (chapters 40-66) styled by many modern critics

the "Deutero- (or Second) Isaias"; between these two comes

a stretch of historical

narrative; some authors, as Michaelis and Hengstenberg, holding with St. Jerome that the prophecies

are placed in chronological

order; others, like Vitringa and

Jahn, in a logical order; others finally, like Gesenius,

Delitzsch, Keil, think the actual order is partly logical and partly chronological.

No less disagreement prevails on the question of the collector. Those who believe

that Isaias is the author of all the prophecies

contained in the book generally fix upon the Prophet

himself. But for the critics who

question the genuineness of some

of the parts, the compilation is by a late and unknown collector. It would be

well, however, before suggesting a solution to analyse

cursorily the contents.

First Isaias

In the first collection

(cc. i-xxxv) there seems to be a grouping of the discourses according to their

subject-matter: (1) cc. i-xii, oracles

dealing with Juda and Israel; (2) cc. xiii-xxiii, prophecies

concerning (chiefly) foreign nations; (3) cc. xxiv-xxvii, an apocalypse;

(4) cc. xxviii-xxxiii, discourses on the relations

of Juda to Assyria;

(5) cc. xxxiv-xxxv, future of Edom and Israel.

First

section

In the first group

(i-xii) we may distinguish separate oracles.

Ch. i arraigns Jerusalem for her ingratitude and

unfaithfulness; severe chastisements have proved unavailing; yet forgiveness can be secured by

a true change of life.

The ravaging of Juda points to

either the time of the Syro-Ephraimite

coalition (735) or the Assyrian

invasion (701). Ch. ii threatens judgment

upon pride and seems to be one of the earliest of the Prophet's

utterances. It is followed (iii-iv) by a severe arraignment of the nation's

rulers for their injustice and a lampoon against the women of Sion

for their wanton luxury. The beautiful apologue of the vineyard serves as a

preface to the announcement of the punishment due to the chief social

disorders. These seem to point to the last days of Joatham, or the very

beginning of the reign of Achaz

(from 736-735 B.C.). The next chapter

(vi), dated in the year of the

death of Ozias (740), narrates

the calling of the Prophet. With

vii opens a series of utterances not inappropriately called "the Book

of Emmanuel"; it is made up

of prophecies bearing on the Syro-Ephraimite

war, and ends in a glowing description (an

independent oracle?) of what the country will be under

a future sovereign (ix, 1-6). Ch. ix, 7-x, 4, in five strophes announces that Israel is foredoomed to utter ruin; the allusion to

rivalries between Ephraim and Manasses

possibly has to do with the revolutions which followed the death of Jeroboam

II; in this case the prophecy

might date some time between

743-734. Much later is the prophecy

against Assur (x, 5-34), later

than the capture of Arshad (740), Calano (738), or Charcamis

(717). The historical situation

therein described suggests the time

of Sennacherib's invasion (about 702 or 701 B.C.). Ch. xi depicts the happy reign to be of the ideal king, and a hymn of thanksgiving and praise (xii) closes this

first division.

Second

section

The first

"burden" is aimed at Babylon

(viii, 1-xiv, 23). The situation presupposed by the Prophet

is that of the Exile; a fact that inclines some to date

it shortly before 549, against others who hold it was written on the death of

Sargon (705). Ch. xiv, 24-27, foretelling the overthrow of the Assyrian army on the mountains of Juda,

and regarded by some as a misplaced part of the prophecy

against Assur (x, 5-34), belongs

no doubt to the period of Sennacherib's campaign. The next

passage (xiv, 28-32) was occasioned by the death of some foe of the Philistines: the names of Achaz

(728), Theglathphalasar III (727), and Sargon (705) have been suggested, the

last appearing more probable. Chapters

xv-xvi, "the burden of Moab",

is regarded by many as referring to the reign of Jeroboam

II, King of Israel (787-746); its date

is conjectural. The ensuing "burden of Damascus" (xvii, 1-11), directed against the Kingdom of Israel as well, should be assigned to about 735 B.C.

Here follows a short utterance on Ethiopia (prob. 702 or 701). Next comes the remarkable prophecy

about Egypt (xix), the interest

of which cannot but be enhanced by the recent discoveries at Elephantine (vv.

18, 19). The date presents a

difficulty, the time ranging,

according to diverse opinions, from 720 to 672 B.C.. The oracle following (xx), against Egypt and Ethiopia, is ascribed to the year in which Ashdod

was besieged by the Assyrians (711). Just

what capture of Babylon is

alluded to in "the burden of the desert of the sea" (xxi, 1-10) is not easy to

determine, for during the lifetime of Isaias Babylon

was thrice besieged and taken (710, 703, 696 B.C.). Independent critics

seem inclined to see here a description of the taking of Babylon

in 528 B.C., the same description being the work of an author living towards

the close of the Babylonian Captivity. The two short prophecies,

one on Edom (Duma; xxi, 11-12) and one on Arabia

(xxi, 13-17), give no clue as to when they were uttered. Ch. xxii, 1-14, is a

rebuke addressed to the inhabitants of Jerusalem. In the rest of the chapter

Sobna (Shebna) is the object of the Prophet's

reproaches and threats (about 701 B.C.). The section closes with the

announcement of the ruin and the restoration of Tyre (xxiii).

Third

section

The third section

of the first collection includes

chapters xxiv-xxviii, sometimes

called "the Apocalypse of Isaias".

In the first part (xxiv-xxvi, 29) the Prophet

announces for an undetermined future the judgment

which shall precede the kingdom of God (xxiv); then in symbolic

terms he describes the happiness of the good

and the punishment of the wicked

(xxv). This is followed by the hymn of the elect (xxvi, 1-19). In the second part (xxvi, 20-xxvii) the Prophet

depicts the judgment hanging

over Israel and its neighbours. The date

is most unsettled among modern critics,

certain passages being attributed

to 107 B.C., others even to a date

lower than 79 B.C.. Let it be remarked, however, that both the ideas and the language of these four chapters

support the tradition

attributing this apocalypse to Isaias.

The fourth division opens with a pronouncement of woe against Ephraim

(and perhaps Juda; xxviii, 1-8),

written prior to 722 B.C.; the historical

situation implied in xxviii, 9-29, is a strong indication that this passage was

written about 702 B.C. To the same date belong xxix-xxxii, prophecies

concerned with the campaign of Sennacherib. This series fittingly concludes

with a triumphant hymn (xxxiii), the Prophet

rejoicing in the deliverance of Jerusalem (701). Chapters

xxxi-xxxv, the last division, announce the devastation of Edom, and the enjoyment of bountiful blessings by ransomed Israel. These two chapters

are thought by several modern critics

to have been written during the captivity

in the sixth century. The foregoing analysis

does not enable us to assert indubitably that this first collection

as such is the work of Isaias; yet as the genuineness

of almost all these prophecies

cannot be seriously questioned, the collection

as a whole might still possibly be attributed to the last years of the Prophet's

life or shortly afterwards. If

there really be passages reflecting a later epoch, they found their way into

the book in the course of time on account of some analogy

to the genuine writings of Isaias. Little need be said of

xxxvii-xxxix. The first two chapters

narrate the demand made by Sennacherib—the surrender of Jerusalem, and the fulfillment of Isaias's

predictions of its deliverance; xxxviii tells of Ezechias's

illness, cure, and song of thanksgiving; lastly xxxix tells of the embassy sent

by Merodach Baladan and the Prophet's

reproof of Ezechias.

Second Isaias

The

second collection (xl-lvi) deals

throughout with Israel's restoration from the Babylonian exile. The main lines of the division as

proposed by the Jesuit Condamine

are as follows: a first section is concerned with the mission and work of

Cyrus; it is made up of five pieces: (a) xl-xli: calling of Cyrus to be Yahweh's instrument in the restoration of Israel; (b) xlii, 8-xliv, 5: Israel's deliverance from exile; (c) xliv, 6-xlvi, 12:

Cyrus shall free Israel and allow Jerusalem to be built; (d) xlvii: ruin of Babylon;

(e) xlviii: past dealings of God with his people are an earnest for the future.

Next to be taken up is another group of utterances, styled by German

scholars "Ebed-Jahweh-Lieder"; it is made up of xlix-lv (to which

xlii, 1-7, should be joined) together with lx-lxii. In this section we hear of

the calling of Yahweh's servant (xlix, 1-li, 16); then of Israel's glorious

home-coming (li, 17-lii, 12);

afterwards is described the servant of Yahweh ransoming his people by his sufferings and death

(xlii, 1-7; lii, 13-15; liii, 1-12); then follows a glowing vision

of the new Jerusalem (liv, 1-lv, 13, and lx, 1-lxii,

12). Ch. lvi, 1-8, develops this idea, that all the upright of heart, no matter what

their former legal status, will

be admitted to Yahweh's new people. In lvi, 9-lvii, the Prophet

inveighs against the idolatry and immorality

so rife among the Jews; the sham piety with which their fasts were observed (lvii). In lix the Prophet

represents the people confessing

their chief sins; this humble acknowledgment of their guilt prompts Yahweh to stoop to those who have "turned from

rebellion". A dramatic description of God's vengeance (lxiii, 1-7) is followed by a prayer for mercy (lxiii, 7-lxiv, 11), and the book

closes upon the picture of the punishment of the wicked

and the happiness of the good.

Many perplexing questions are raised by the exegesis of the "Second Isaias".

The "Ebed-Jahweh-Lieder", in particular, suggest many difficulties.

Who is this "servant of Yahweh"? Does the title apply to the same person throughout the ten chapters?

Had the writer in view some historical

personage of past ages, or one belonging to his own time, or the Messias to come, or even some ideal person? Most commentators

see in the "servant of Yahweh" an individual.

But is that individual one of

the great historical figures of Israel? No satisfactory

answer has been given. The names of Moses,

David, Ozias,

Ezechias, Isaias, Jeremias,

Josias, Zorobabel, Jechonias,

and Eleazar have all been

suggested as being the person. Catholic exegesis has always pointed out the fact that all the

features of the "servant of Yahweh" found their complete realization in the person of Our Lord Jesus Christ. He therefore should be regarded as

the one individual described by

the Prophet. The "Second Isaias"

gives rise to other more critical and less important problems. With the

exception of one or two passages, the point of view throughout this section is

that of the Babylonian Captivity; there is an unmistakable

difference between the style of these twenty-seven chapters

and that of the "First Isaias"; moreover, the theological ideas of xl-lxvi show a decided advance on those

found in the first thirty-nine chapters.

If this be true, does it not follow that xl-lxvi are not by

the same author as the prophecies

of the first collection, and may

there not be good grounds for

attributing the authorship of these chapters

to a "second Isaias" living towards the close of the Babylonian Captivity? Such is the contention of most of

the modern non-Catholic scholars.

This is hardly the

place for a discussion of so intricate a question. We therefore limit ourselves

to stating the position of Catholic scholarship on this point. This is clearly set

out in the decision issued by the Pontifical Biblical Commission, 28 June, 1908. (1) Admitting the existence

of true prophecy;

(2) There is no reason why "Isaias and the other Prophets

should utter prophecies

concerning only those things which were about to take place immediately or

after a short space of time"

and not "things that should be fulfilled after many ages". (3) Nor

does anything postulate that the Prophets

should "always address as their hearers, not those who belonged to the

future, but only those who were present and contemporary, so that they could be

understood by them". Therefore it cannot be asserted that "the second

part of the Book of Isaias

(xl-lxvi), in which the Prophet

addresses as one living amongst them, not the Jews who were the contemporaries of Isaias, but

the Jews mourning in the Exile of Babylon,

cannot have for its author Isaias himself, who was dead long before,

but must be attributed to some unknown Prophet

living among the exiles". In other words, although the author of Isaias

xl-lxvi does speak from the point of view of the Babylonian Captivity, yet this is no proof that he must have lived and

written in those times. (4) "The philological argument from language and

style against the identity of the author of the Book

of Isaias is not to be considered weighty enough to

compel a man of judgment,

familiar with Hebrew and criticism,

to acknowledge in the same book a plurality of authors". Differences of

language and style between the parts of the book are neither denied nor

underrated; it is asserted only that such as they appear, they do not compel

one to admit the plurality of authors. (5) "There are no solid arguments

to the fore, even taken cumulatively, to prove

that the book of Isaias is to be attributed not to Isaias

himself alone, but to two or rather to many authors".

Appreciation of the work of Isaias

It may not be

useless shortly to set forth the prominent features of the great Prophet,

doubtless one of the most striking personalities in Hebrew

history. Without holding any

official position, it fell to the lot of Isaias to take an active

part during well nigh forty troublesome years in controlling the policy of his

country. His advice and rebukes were sometimes unheeded, but experience finally

taught the rulers of Juda that

to part from the Prophet's views

meant always a set-back for the political situation of Juda.

In order to understand the trend of his policy it is necessary to remember

by what principle it was animated. This principle he derived from his unshaken faith in God governing the world, and particularly His own

people and the nations coming in contact with the latter. The people of Juda,

forgetful of their God, given to idolatrous practices and social

disorders of many kinds, had paid little heed to former warnings. One thing

only alarmed them, namely that hostile nations were threatening Juda

on all sides; but were they not the chosen people of God? Certainly He would not allow His own nation

to be destroyed, even as others had been. In the meantime prudence dictated that the best possible means be taken

to save themselves from present

dangers. Syria and Israel were plotting against Juda

and her king; Juda and her king

would appeal to the mighty

nation of the North, and later to the King of Egypt.

Isaias would not

hear aught of this short-sighted policy, grounded only on human

prudence, or a false religious

confidence, and refusing to look beyond the moment. Juda

was in terrible straits; God alone could save

her; but the first condition

laid down for the manifestation of His power was moral

and social reformation. Syrians,

Ephraimites, Assyrians, and all the rest were but the instruments of

the judgment of God, the purpose of which is the overthrow of

sinners. Certainly Yahweh will not allow His people to be

utterly destroyed; His covenant He will keep; but it is vain to hope

that well-deserved chastisement may be escaped. From this view of the designs

of God never did the faith of Isaias waver. He first proclaimed

this message at the beginning of the reign of Achaz.

The king and his counsellors saw no salvation for Juda

except in an alliance with, that is an acknowledgment of vassalage to, Assyria.

This the Prophet opposed with all

his might. With his keen foresight he had clearly perceived that the real

danger to Juda was not from Ephraim

and Syria, and that the intervention of Assyria in the affairs of Palestine involved a

complete overthrow of the balance of power along the Mediterranean coast.

Moreover, the Prophet

entertained no doubt but that sooner or later a conflict

between the rival empires of the Euphrates and the Nile must arise, and then

their hosts would swarm over the

land of Juda. To him it was

clear that the course proposed by Juda's

self-conceited politicians was like the mad

flight of "silly doves",

throwing themselves headlong into the net. Isaias's advice was not

followed and one by one the consequences he had foretold were realized.

However, he continued to proclaim his prophetical

views of the current events. Every new event of importance is by him turned

into a lesson not only to Juda

but to all the neighbouring nations. Damascus

has fallen; so will the drunkards

and revellers of Samaria see the ruin of

their city. Tyre boasts of her wealth

and impregnable position; her doom is no less decreed,

and her fall will all the more

astound the world. Assyria

herself, fattened with the spoils of all nations, Assyria

"the rod of God's

vengeance", when she will have accomplished her providential

destiny, shall meet with her fate.

God has thus decreed

the doom of all nations for the accomplishment of His purposes and the establishment

of a new Israel cleansed from all past defilements.

Judean politicians

towards the end of the reign of Ezechias

had planned an alliance with the King of Egypt against Assyria

and carefully concealed their purpose from the Prophet.

When the latter came to know the preparations for rebellion, it was already

too late to undo what had been done. But he could at least give vent to his anger (see Isaiah 30), and we know both from the Bible and Sennacherib's own account of the campaign

of 701 how the Assyrian army routed the Egyptians

at Altaku (Elteqeh of Joshua 19:44), captured Accaron,

and sent a detachment to ravage Juda;

Jerusalem, closely invested, was saved

only by the payment of an enormous ransom. The vindication of Isaias's

policy, however, was not yet complete. The Assyrian army withdrew; but Sennacherib, apparently

thinking it unsafe to leave in his wake a fortified city like Jerusalem, demanded the immediate surrender of Ezechias's

capital. At the command of Ezechias,

no answer was given to the message; but the king humbly

bade Isaias to intercede

for the city. The Prophet had

for the king a reassuring message. But the respite in the Judean

capital was short. Soon a new Assyrian

embassy arrived with a letter from the king containing an ultimatum. In the

panic-stricken city there was a man of whom Sennacherib had taken no account;

it was by him that the answer was to be given to the ultimatum of the proud

Assyrians: "The virgin,

the daughter of Sion hath despised

thee and laughed thee to scorn; . . . He shall not come into this city, nor

shoot an arrow into it. . . . By the way that he came, he shall return, and

into this city he shall not come, saith the Lord" (xxxvii, 22, 33). We know in reality how a sudden catastrophe overtook

the Assyrian army and God's promise was fulfilled. This crowning

vindication of the Divinely inspired

policy of Isaias prepared the hearts of the Jews for the religious

reformation brought about by Ezechias,

no doubt along lines laid down by the Prophet.

In reviewing the

political side of Isaias's public life, we have already seen

something of his religious and social

ideas; all these view-points

were indeed most intimately connected in his teaching. It may be well now to

dwell a little more fully on this part of the Prophet's

message. Isaias's description of the religious

condition of Juda

in the latter part of the eighth century is anything but flattering. Jerusalem is compared to Sodom

and Gomorrah; apparently the

bulk of the people were superstitious rather than religious.

Sacrifices were offered

out of routine; witchcraft and divination

were in honour; nay more, foreign deities were openly invoked

side by side with the true God, and in secret the immoral worship

of some of these idols was

widely indulged in, the higher-class

and the Court itself giving in

this regard an abominable example. Throughout the kingdom

there was corruption of higher officials, ever-increasing luxury among the wealthy,

wanton haughtiness of women, ostentation among the middle-class people,

shameful partiality of the judges,

unscrupulous greed of the owners of large estates, and

oppression of the poor and

lowly. The Assyrian suzerainty

did not change anything in this woeful state of affairs. In the eyes of Isaias

this order of things was intolerable; and he never tired repeating it could not

last. The first condition of social

reformation was the downfall of the unjust and corrupt rulers; the Assyrians were the means appointed by God to level their pride and tyranny with the dust. With their mistaken

ideas about God, the nation imagined

He did not concern Himself about the dispositions of His worshippers. But God loathes

sacrifices offered

by ". . . hands full of blood. Wash

yourselves, be clean, . . . relieve the oppressed, judge

for the fatherless, defend the widow. . . . But if you will not, . . . the sword

shall devour you" (i, 15-20). God here appears as the avenger of disregarded human

justice as much as of His Divine rights. He cannot and will not let injustice, crime, and idolatry go unpunished. The destruction of sinners will

inaugurate an era of regeneration,

and a little circle of men faithful

to God will be the first-fruits of a new Israel free from past defilements

and ruled by a scion of David's House. With the reign of Ezechias

began a period of religious

revival. Just how far the reform

extended we are not able to state; local sanctuaries

around which heathenish abuses had gathered were

suppressed, and many 'asherîm and masseboth were destroyed. It is true the times were not ripe for a radical change,

and there was little response to the appeal

of the Prophet for moral

amendment and redress of social

abuses.

The Fathers of the Church, echoing the eulogy of Jesus,

son of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus 48:25-28), agree that Isaias was

the greatest of the literary Prophets

(Eusebius, "Præp. Evang.", v, 4, P.G., XXII,

370; "Synops. Script. S.", among the works of St. Athan., P.G.,

XXXVIII, 363; St. Cyril of Jerusalem, "In Is., Prooem.", P.G.,

LXX, 14; St. Isidore of Pelusium, "Epist.", i, 42, P.G.,

LXXVIII, 208; Theodoret.,

"In Is. Argum.", P.G., LXXXI, 216; St. Jerome, "Prol. in Is.", P.L., XXIV, 18;

"Præf. ad Paul. et Eustoch.", P.L., XXXII, 769; City of God XVIII.29). Isaias's poetical

genius was in every respect worthy of his lofty position as a Prophet.

He is unsurpassed in poetry, descriptive, lyric, or elegiac. There is in his

compositions an uncommon elevation and majesty of conception, and an

unparalleled wealth of imagery,

never departing, however, from the utmost propriety, elegance, and dignity. He

possessed an extraordinary power of adapting his language both to occasions and

audiences; sometimes he displays

most exquisite tenderness, and at other times austere severity; he successively

assumes a mother's pleading and irresistible tone, and the stern manner of an

implacable judge, now making use

of delicate irony to bring home to his hearers what he would have them

understand, and then pitilessly shattering

their fondest illusions or

wielding threats which strike like mighty thunderbolts.

His rebukes are neither impetuous like those of Osee

nor blustering like those of Amos;

he never allows the conviction of his mind

or the warmth of his heart to overdraw any feature or to overstep the limits

assigned by the most exquisite taste. Exquisite taste indeed is one

of the leading features of the Prophet's

style. This style is rapid, energetic, full of life

and colour, and withal always chaste

and dignified. It moreover manifests a wonderful command of language. It has

been justly said that no Prophet

ever had the same command of noble thoughts; it may be as justly

added that never perhaps did any man

utter lofty thoughts in more beautiful language. St. Jerome rejected the idea that Isaias's prophecies

were true poetry in the full sense of the word (Præf. in

Is., P.L., XXVIII, 772). Nevertheless the authority of the illustrious Robert

Lowth, in his "Lectures on the Sacred

Poetry of the Hebrews" (1753), esteemed "the whole book of Isaiah

to be poetical, a few passages excepted, which if brought together, would not

at most exceed the bulk of five or six chapters".

This opinion of Lowth, at first scarcely noticed, became more and more general

in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and is now common among Biblical

scholars.

In

addition to general and special commentaries consult: CHEYNE, Book

of Isaiah chronologically arranged (London, 1870); IDEM, Prophecies

of Isaiah (London, 1880); IDEM, Introd. to the Book of Isaiah

(London, 1895); DRIVER, Isaiah: his life and times and the writings

which bear his name (London, 1888); LOWTH, Isaiah,

translation, dissert. and notes (London, 1778); SKINNER, Isaiah

(Cambridge, 1896); G. A. SMITH, Book of Isaiah (Expositor's

Bible, 1888-1890); W. R. SMITH, The Prophets of Israel and their

place in history (London, 1882); KNABENBAUER, Comment. in

Isaiam prophetam (Paris, 1887); CONDAMINE, Livre d'Isaie,

trad. critique avec notes et comment. (Paris, 1905; a volume of

introduction to the same is forthcoming); LE HIR, Les trois grandes

prophètes, Isaïe, Jérémie, Ezéchiel (Paris, 1877); IDEM, Etudes

Bibliques (Paris, 1878); DELITZSCH, Commentar über das Buch

Jesaja; tr. (Edinburgh, 1890); DUHM, Das Buch Jesaia

(Gottingen, 1892); GESENIUS, Der Prophet Jesaja (Leipzig,

1820-1821); EWALD, Die Propheten des Alten Bundes (Tübingen,

1840-1841); tr. by F. SMITH, (London, 1876—); HITZIG, Der Prophet

Jesaja übers. und ausgelegt (Heidelberg, 1833); KITTEL, Der

Prophet Jesaia, 6th ed. of DILLMANN's work of the same title (Leipzig,

1898); KNABENBAUER, Erklärung des Proph. Isaias (Freiburg,

1881); MARTI, Das Buch Jesaja (Tübingen, 1900).

Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by WGKofron. With thanks to St. Mary's Church, Akron, Ohio.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil

Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New

York.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08179b.htm

THE MARTYRDOM OF ISAIAH

[Chapter 1]

1 And it came to pass in the twenty-sixth year of the reign of

Hezekiah king of Judah that he

2 called Manasseh his son. Now he was his only one. And he called him

into the presence of Isaiah the son of Amoz the prophet; and into the presence

of Josab the son of Isaiah.

6b, 7 And whilst he (Hezekiah) gave commands, Josab the son of Isaiah

standing by, Isaiah said to Hezekiah the king, but not in the presence of

Manasseh only did he say unto him: 'As the Lord liveth, whose name has not been

sent into this world, [and as the Beloved of my Lord liveth], and as the Spirit

which speaketh in me liveth, all these commands and these words shall be made

of none effect by Manasseh thy son, and through the agency of his hands I shall

depart mid the torture of

8 my body. And Sammael Malchira shall serve Manasseh, and execute all

his desire, and he shall

9 become a follower of Beliar rather than of me. And many in

Jerusalem and in Judaea he shall cause to abandon the true faith, and Beliar

shall dwell in Manasseh, and by his hands I shall be

10 sawn asunder.' And when Hezekiah heard these words he wept very

bitterly, and rent his garments,

11 and placed earth upon his head, and fell on his face. And Isaiah

said unto him: 'The counsel of

12 Sammael against Manasseh is consummated: nought shall avail thee.'

And on that day Hezekiah

13 resolved in his heart to slay Manasseh his son. And Isaiah said to

Hezekiah: ['The Beloved hath made of none effect thy design, and] the purpose

of thy heart shall not be accomplished, for with this calling have I been

called [and I shall inherit the heritage of the Beloved].'

[Chapter 2]

1 And it came to pass after that Hezekiah died and Manasseh became

king, that he did not remember the commands of Hezekiah his father but forgat

them, and Sammael abode in Manasseh

2 and clung fast to him. And Manasseh forsook the service of the God

of his father, and he served

3 Satan and his angels and his powers. And he turned aside the house

of his father which had been

4 before the face of Hezekiah the words of wisdom and

from the service of God. And Manasseh turned aside his heart to serve Beliar;

for the angel of lawlessness, who is the ruler of this world, is Beliar, whose

name is Matanbuchus. And he delighted in Jerusalem because of Manasseh, and he

made him strong in apostatizing (Israel) and in the lawlessness which was

spread abroad in Jerusalem

5 And witchcraft and magic increased and divination and augulation,

and fornication, [and adultery], and the persecution of the righteous by

Manasseh and [Belachira, and] Tobia the Canaanite, and John

6 of Anathoth, and by (Zadok> the chief of the works. And the rest

of the acts, behold they are written

7 in the book of the Kings of Judah and Israel. And when Isaiah the

soll of Amoz saw the lawlessness which was being perpetratcd in Jerusalem and

the worship of Satan and his wantonness, he

8 withdrew from Jerusalem and settled in Bethlehem of Judah. And

there also there was much

9 lawlessness, and withdrawing from Bethlehem he settled on a

mountain in a desert place. [And Micaiah the prophet, and the aged Ananias, and

Joel and Habakkuk, and his son Josab, and many of the faithful who believed in

the ascension into heaven, withdrew and settled on the mountain.]

10 They were all clothed with garments of hair, and they were all

prophets. And they had nothing with them but were naked, and they all lamented

with a great lamentation because of the going

11 astray of Israel. And these eat nothing save wild herbs which they

gathered on the mountains, and having cooked them, they lived thereon together

with Isaiah the prophet. And they spent two years of

12 days on the mountains and hills. [And after this, whilst they were

in thc desert, there was a certain man in Samaria named Belchlra, of the family

of Zedekiah, the son of Chenaan, a false prophet whose dwelling was in

Bethlehem. Now Hezekiah the son of Chanani, who was the brother of his father,

and in the days of Ahab king of Israel had been the teacher of the 400 prophets

of Baal,

13 had himself smitten and reproved Micaiah the son of Amada the

prophet. And he, Micaiah, had been reproved by Ahab and cast into prison. (And

he was) with Zedekiah the prophet: they were

14 with Ahaziah the son of Ahab, king in Samaria. And Elijah the

prophet of Tebon of Gilead was reproving Ahaziah and Samaria, and prophesied

regarding Ahaziah that he should die on his bed of sickness, and that Samaria

should be delivered into the hand of Leba Nasr because he had slain

15 the prophets of God. And when the false prophets, who were with

Ahaziah the son of Ahab and

16 their teacher Gemarias of Mount Joel had heard -now he was brother

of Zedekiah -when they had heard, they persuaded Ahaziah the king of Aguaron

and slew Micaiah.

[Chapter 3]

1 And Belchlra recognized and saw the place of Isaiah and the

prophets who were with him; for he dwelt in the region of Bethlehem, and was an

adherent of Manasseh. And he prophesied falsely in Jerusalem, and many

belonging to Jerusalem were confederate with him, and he was a Samaritan.

2 And it came to pass when Alagar Zagar, king of Assyria, had come

and captured Samaria and taken the nine (and a half) tribes captive, and led

them away to the mountains of the Medes and the

3 rivers of Tazon; this (Belchira) while still a youth, had escaped

and come to Jerusalem in the days of Hezekiah king of Judah, but he walked not

in the ways of his father of Samaria; for he feared

4 Hezekiah. And he was found in the days of Hezekiah speaking words

of lawlessness in Jerusalem.

5 And the servants of Hezekiah accused him, and he made his escape to

the region of Bethlehem.

6 And they persuaded . . . And Belchlra accused Isaiah and the

prophets who were with him, saying: 'Isaiah and those who are with him prophesy

against Jerusalem and against the cities of Judah that they shall be laid waste

and (against the children of Judah and) Benjamin also that they shall go into

captivity, and also against thee, O lord the king, that thou shalt go (bound)

with hooks

8 and iron chains': But they prophesy falsely against Israel and

Judah. And Isaiah himself hath

9 said: 'I see more than Moses the prophet.' But Moses said: 'No man

can see God and live':

10 and Isaiah hath said: 'I have seen God and behold I live.' Know,

therefore, O king, that he is lying. And Jerusalem also he hath called Sodom,

and the princes of Judah and Jerusalem he hath declared to be the people of

Gomorrah. And he brought many accusations against Isaiah and the

11 prophets before Manasseh. But Beliar dwelt in the heart of

Manasseh and in the heart of the

12 princes of Judah and Benjamin and of the eunuchs and of the

councillors of the king. And the words of Belchira pleased him [exceedingly],

and he sent and seized Isaiah.

[Chapter 5]

1b, 2 And he sawed him asunder with a wood-saw. And when Isaiah was

being sawn in sunder Balchlra stood up, accusing him, and all the false

prophets stood up, laughing and rejoicing because

3 of Isaiah. And Balchlra, with the aid of Mechembechus, stood up

before Isaiah, [laughing]

4 deriding; And Belchlra said to Isaiah: 'Say: "I have lied in

all that I have spoken, and likewise

5 the ways of Manasseh are good and right. And the ways also of

Balchlra and of his associates are

6, 7 good."' And this he said to him when he began to be sawn in

sunder. But Isaiah was (absorbed)

8 in a vision of the Lord, and though his eyes were open, he saw them

. And Balchlra spake thus to Isaiah: 'Say what I say unto thee

and I will turn their heart, and I will compel Manasseh

9 and the princes of Judah and the people and all Jerusalem to

reverence thee.' And Isaiah answered and said: 'So far as I have utterance (I say):

Damned and accursed be thou and all thy powers and

10, 11 all thy house. For thou canst not take (from me) aught save

the skin of my body.' And they

12 seized and sawed in sunder Isaiah, the son of Amoz, with a

wood-saw. And Manasseh and

13 Balchlra and the false prophets and the princes and the people

[and] all stood looking on. And to the prophets who were with him he said

before he had been sawn in sunder: 'Go ye to the region

14 of Tyre and Sidon; for for me only hath God mingled the cup.' And

when Isaiah was being sawn in sunder, he neither cried aloud nor wept, but his

lips spake with the Holy Spirit until he was sawn in twain.

From The

Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament

by R.H. Charles, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913

Scanned and edited by Joshua Williams, Northwest Nazarene College, 1995

by R.H. Charles, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913

Scanned and edited by Joshua Williams, Northwest Nazarene College, 1995

SOURCE : http://www.ccel.org/c/charles/otpseudepig/martisah.htm

Isaia, figlio di Amos e parente del re Manasse, discendeva dalla casa reale di Davide. Visse circa ottocento anni prima di Cristo.

La missione di profeta gli fu conferita in modo solenne in una visione: vide il Signore seduto sopra un gran trono nel tempio, circondato da cherubini. Uno di questi spiriti si mosse prese dall’altare un carbone acceso, e venuto a Isaia gli toccò la bocca con il carbone dicendo: “Ecco che questo ha toccato le tue labbra, e sarà tolta la tua iniquità e sarà lavato il tuo peccato”. Poi il Signore parlò direttamente a Isaia invitandolo a predicare al suo popolo.

Il Profeta predicò la parola di Dio sotto i re Ozia, Giatan, Acaz, Ezechia, Manasse e la sua missione durò circa un secolo. Al re Manasse, empio e crudele, caduto nell'idolatria, il Signore mandò Isaia per richiamarlo al culto dell’unico vero Dio, al pentimento dei suoi peccati.

Il Profeta non fu ascoltato; anzi il sovrano adirato lo condannò a morte. Fu preso e segato in due con una sega di legno, e soffrendo questo tremendo supplizio passò al Signore. Il re Manasse subì il castigo che gli era stato predetto, e Isaia aggiungeva alla gloria di profeta quella di martire.

Isaia fu il maggiore dei Profeti. S. Girolamo lo riguarda non solo come profeta, ma anche come evangelista e apostolo. Le sue profezie sono di una tale chiarezza che sembrano una storia del passato piuttosto che una predizione.

Gli scritti di Isaia narrano principalmente le minacce di Dio al popolo di Israele e ai popoli vicini per i loro peccati, ma il profeta nel descrivere i giusti giudizi di Dio allude molto spesso alla venuta del Liberatore e descrivendo la sua nascita, le sue opere e specialmente la sua passione, eccita negli animi l’amore e la confidenza in Lui.

Sant' Isaia Profeta

n. 770 a.C. circa

Etimologia: Isaia = Jahvè è il mio aiuto, dall'ebraico.

Martirologio Romano: Commemorazione di sant’Isaia, profeta, che, nei

giorni di Ozia, Iotam, Acaz ed Ezechia, re di Giuda, fu mandato a rivelare al

popolo infedele e peccatore la fedeltà e la salvezza del Signore a compimento

della promessa fatta da Dio a Davide. Presso i Giudei si tramanda che sia morto martire

sotto il re Manasse.

Di questo

santo Profeta lo Spirito Santo nell’Ecclesiastico ha fatto scrivere: “Isaia fu

un grande profeta e fedele agli occhi del Signore. Il sole tornò indietro nei

di lui giorni e molti altri egli aggiunse alla vita del re. Vide il fine dei

tempi per un gran dono di Spirito, e consolò quelli che piangevano

Gerusalemme”.

Isaia, figlio di Amos e parente del re Manasse, discendeva dalla casa reale di Davide. Visse circa ottocento anni prima di Cristo.

La missione di profeta gli fu conferita in modo solenne in una visione: vide il Signore seduto sopra un gran trono nel tempio, circondato da cherubini. Uno di questi spiriti si mosse prese dall’altare un carbone acceso, e venuto a Isaia gli toccò la bocca con il carbone dicendo: “Ecco che questo ha toccato le tue labbra, e sarà tolta la tua iniquità e sarà lavato il tuo peccato”. Poi il Signore parlò direttamente a Isaia invitandolo a predicare al suo popolo.

Il Profeta predicò la parola di Dio sotto i re Ozia, Giatan, Acaz, Ezechia, Manasse e la sua missione durò circa un secolo. Al re Manasse, empio e crudele, caduto nell'idolatria, il Signore mandò Isaia per richiamarlo al culto dell’unico vero Dio, al pentimento dei suoi peccati.

Il Profeta non fu ascoltato; anzi il sovrano adirato lo condannò a morte. Fu preso e segato in due con una sega di legno, e soffrendo questo tremendo supplizio passò al Signore. Il re Manasse subì il castigo che gli era stato predetto, e Isaia aggiungeva alla gloria di profeta quella di martire.

Isaia fu il maggiore dei Profeti. S. Girolamo lo riguarda non solo come profeta, ma anche come evangelista e apostolo. Le sue profezie sono di una tale chiarezza che sembrano una storia del passato piuttosto che una predizione.

Gli scritti di Isaia narrano principalmente le minacce di Dio al popolo di Israele e ai popoli vicini per i loro peccati, ma il profeta nel descrivere i giusti giudizi di Dio allude molto spesso alla venuta del Liberatore e descrivendo la sua nascita, le sue opere e specialmente la sua passione, eccita negli animi l’amore e la confidenza in Lui.

Autore: Antonio

Galuzzi