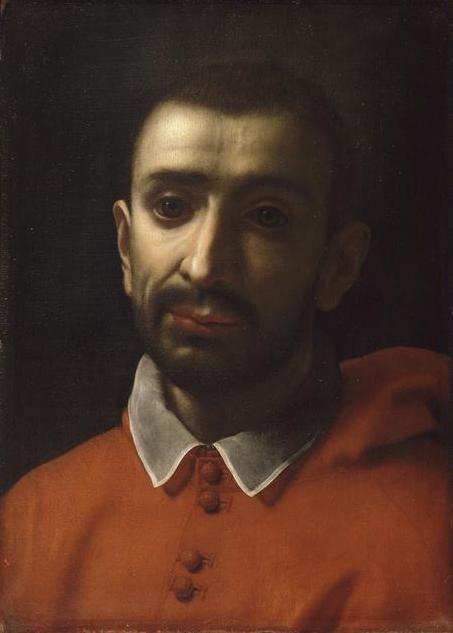

Saint Charles Borromée

Archevêque de Milan (+ 1584)

Fils cadet d'une noble famille italienne, il avait

tout pour se laisser entraîner dans une vie facile et fastueuse.

Neveu d'un pape, nommé cardinal à 22 ans, il est

submergé de charges honorifiques très lucratives: son revenu annuel était de

52.000 écus(*). Il reçoit les revenus du diocèse de Milan, des abbayes de

Mozzo, Folina, Nonatella, Colle et de quelques autres légations: Bologne,

Spolète, Ravenne, etc ... Il reste laïc, grand amateur de chasse et de musique

de chambre.

Mais la conscience de son devoir est telle qu'il

s'impose dans la vie mondaine et brillante de Rome, par sa rigueur et son

travail. Il collabore efficacement à la reprise du Concile de Trente,

interrompu depuis huit ans. Au moment de la mort subite de son frère aîné,

alors qu'il pourrait quitter l'Église pour la charge de chef d'une grande

famille, il demande à devenir prêtre.

Désormais il accomplit par vocation ce qu'il réalisait

par devoir. Devenu archevêque de Milan, il crée des séminaires pour la

formation des prêtres. Il prend soin des pauvres alors qu'il vit lui-même

pauvrement. Il soigne lui-même les pestiférés quand la peste ravage Milan en 1576.

Il demande à tous les religieux de se convertir en infirmiers. Les années

passent. Malgré le poids des années, il n'arrête pas de se donner jusqu'à

l'épuisement.

"Pour éclairer, la chandelle doit se consumer,

" dit-il à ceux qui lui prêchent le repos.

(*) Un internaute nous signale: "si on se

rapporte à l'écu de François Ier (environ même époque ), il pesait environ 3

grammes; les 52 000 écus du revenu de Charles ne devaient donc pas de beaucoup

dépasser les 150 000 grammes d'or fin soit 150 kg"

Le 4 novembre 2010, le Saint-Père a fait parvenir un

message au Cardinal Dionigio Tettamanzi, Archevêque de Milan (Italie), pour le

quatrième centenaire de la canonisation de saint Charles Borromée. En voici les

passages principaux: Charles Borromée vécut dans une période difficile

pour le christianisme, "une époque sombre parsemée d'épreuves pour la

communauté chrétienne, pleine de divisions et de convulsions doctrinales,

d'affaiblissement de la pureté de la foi et des mœurs, de mauvais exemples de

la part du clergé. Mais il ne se contenta pas de se lamenter ou de condamner.

Pour changer les autres, il commença par réformer sa propre vie... Il était

conscient qu'une réforme crédible devait partir des pasteurs" et pour y

parvenir il eut recours à la centralité de l'Eucharistie, à la spiritualité de

la croix, à la fréquence des sacrements et à l'écoute de la Parole, à la

fidélité envers le Pape, "toujours prompt à obéir à ses indications comme

garantie d'une communion ecclésiale, authentique et complète".

Après avoir manifesté le désir de voir l'exemple de

saint Charles continuer à inspirer la conversion personnelle comme

communautaire, Benoît XVI encourage prêtres et diacres à faire de leur vie un

parcours de sainteté. Il encourage en particulier le clergé milanais à suivre

"une foi limpide, à vivre une vie sobre, selon l'ardeur apostolique de

saint Ambroise, de

saint Charles Borromée et de tant d'autre pasteurs locaux... Saint Charles, qui

fut un véritable père des pauvres, fonda des institutions d'assistance"

et, "durant la peste de 1576 il resta parmi son peuple pour le servir et

le défendre avec les armes de la prière, de la pénitence et de l'amour".

Sa charité ne se comprend pas si on ignore son rapport passionné au Seigneur,

qui "se reflétait dans sa contemplation du mystère de l'autel et de la

croix, d'où découlait sa compassion des hommes souffrants et son élan

apostolique de porter l'Évangile à chacun... C'est de l'Eucharistie, cœur de

toute communauté, qu'il faut tirer la force d'éduquer et de combattre pour la

charité. Toute action charitable et apostolique trouve force et fécondité dans

cette source". Le Saint-Père conclut par un appel aux jeunes: "A

l'exemple de Charles Borromée, vous pouvez faire de votre jeunesse une offrande

au Christ et au prochain... Si vous êtes l'avenir de l'Église, vous en faites

partie dès aujourd'hui. Si vous avez l'audace de croire dans la sainteté, vous

serez le principal trésor de l'Église ambrosienne, bâtie sur ses saints".

(source: VIS 20101104 420)

Nommé par son oncle, le pape Pie IV, cardinal et

archevêque de Milan, il se montra sur ce siège un vrai pasteur, attentif aux

besoins de l’Église de son temps. Pour la formation de son clergé, il réunit

des synodes et fonda des séminaires ; pour favoriser la vie chrétienne, il

visita plusieurs fois tout son troupeau et les diocèses suffragants et

prit beaucoup de dispositions pour le salut des âmes. Il s’en alla la

veille de ce jour à la patrie du ciel, en 1584.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/7/Saint-Charles-Borromee.html

Saint Charles Borromée

Archevêque de Milan

(1538-1584)

Saint Charles Borromée, né au sein de l'opulence et

des grandeurs, devait être l'un des plus illustres pontifes de l'Église dans

tous les temps. Sa vocation se révéla d'une manière si remarquable, que son

père le destina dès son enfance au service des autels. Neveu du Pape Pie VI,

Charles était cardinal avant l'âge de vingt-trois ans, et recevait les plus

hautes et les plus délicates missions.

Après son élévation au sacerdoce, il fut promu à

l'archevêché de Milan, qu'il devait diriger avec la sagesse et la science des

vieillards. Ce beau diocèse était alors dans une désorganisation complète:

peuple, clergé, cloîtres, tout était à renouveler. Le pieux et vaillant pontife

se mit à l'oeuvre, mais donna d'abord l'exemple. Il mena dans son palais la vie

d'un anachorète; il en vint à ne prendre que du pain et de l'eau, une seule

fois le jour; ses austérités atteignirent une telle proportion, que le Pape dut

exiger de sa part plus de modération dans la pénitence.

Il vendit ses meubles précieux, se débarrassa de ses

pompeux ornements, employa tout ce qu'il avait de revenus à l'entretien des

séminaires, des hôpitaux, des écoles, et au soulagement des pauvres honteux et

des mendiants. Son personnel était soumis à une règle sévère; les heures de

prières étaient marquées, et personne ne s'absentait alors sans permission. Les

prêtres de son entourage, soumis à une discipline encore plus stricte,

formaient une véritable communauté, qui fut digne de donner à l'Église un

cardinal et plus de vingt évêques.

Le saint archevêque transforma le service du culte

dans sa cathédrale et y mit à la fois la régularité et la magnificence. Aucune

classe de son diocèse ne fut oubliée; toutes les oeuvres nécessaires furent

fondées, et l'on vit apparaître partout une merveilleuse efflorescence de vie

chrétienne. Ce ne fut pas sans de grandes épreuves. Saint Charles reçut un

jour, d'un ennemi, un coup d'arquebuse, pendant qu'il présidait à la prière

dans sa chapelle particulière; par une protection providentielle, la balle ne

fit que lui effleurer la peau, et le Saint continua la prière sans trouble. On

sait le dévouement qu'il montra pendant la peste de Milan. Il visitait toutes

les maisons et les hôpitaux, et sauva la vie, par ses charités, à soixante-dix

mille malheureux. Les pieds nus et la corde au cou, le crucifix à la main, il

s'offrit en holocauste, fit des cérémonies expiatoires et apaisa la colère

divine. Il mourut sur la cendre, à quarante-six ans.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_charles_borromee.html

Borromée, Charles

2.10.1538 à Arona, 3.11.1584 à Milan, de Milan. Fils de Gilberto, comte d'Arona, et de Margherita de' Medici. Neveu par sa mère du pape Pie IV (Giovan Angelo de' Medici), cousin de Federico Borromeo et de Mark Sittich von Hohenems. B. fut orienté précocement vers la carrière ecclésiastique et reçut à 12 ans déjà le titre d'abbé commendataire. Eduqué par des précepteurs privés à Arona et à Milan, B. fit ses études de droit à Pavie et obtint son doctorat en l'un et l'autre droits (1559). La même année, son oncle devint pape; ce dernier l'appela à Rome et en fit son proche collaborateur en le nommant cardinal-diacre et secrétaire d'Etat (1560). En 1560 encore, B. se vit confier l'administration permanente de l'archidiocèse de Milan mais, comme il resta à Rome jusqu'en septembre 1565, il délégua cette charge aux évêques auxiliaires Sebastiano Donati (1561) et Gerolamo Ferragata (1562). Son séjour à Rome coïncida avec un processus de maturation spirituelle (peut-être liée à la mort de son frère en 1562) qui le conduisit au sacerdoce puis à l'épiscopat (1563). En 1564, B. devint cardinal du titre de Sainte-Praxède. Il s'installa dans son diocèse en 1566 et y appliqua immédiatement les directives du concile de Trente. Il accorda une attention particulière aux cantons catholiques et à leurs bailliages italiens soumis à la juridiction ecclésiastique de Milan, s'y rendant fréquemment au cours de son épiscopat. En 1560 déjà, il avait été nommé Protector Helvetiae à la demande des cantons catholiques. Ses visites pastorales et diplomatiques lui permirent de prendre conscience de la gravité de la situation morale et matérielle dans laquelle se trouvaient le clergé et le peuple et d'établir les fondements d'une profonde réforme spirituelle. Afin de renforcer l'instruction et la discipline du clergé et de contenir le développement du protestantisme, B. demanda en 1579 la création d'une nonciature permanente auprès des Confédérés, instituée en 1586 seulement en raison de la résistance de la curie romaine; il demanda aussi l'ouverture d'un collège jésuite et d'un grand séminaire. La fondation à Milan du Collegium helveticum, destiné à la formation du clergé suisse et doté de cinquante bourses d'études (1579), et le patronage de la fondation du collège Papio d'Ascona (1584) vont dans le même sens. Encouragés par ces exemples, les jésuites s'établirent à Lucerne puis dans d'autres villes de la Confédération (Fribourg, Porrentruy), tandis que les capucins ouvraient leurs missions en Suisse centrale (Altdorf, Stans et Lucerne) avec l'appui du nonce Giovanni Francesco Bonomi. Considéré comme un modèle d'évêque post-tridentin, B. fut canonisé le 1er novembre 1610; il est le patron de la Suisse catholique.

Bibliographie

– P. D'Alessandri, Atti di san Carlo riguardanti la Svizzera e i suoi

territori, 1909

– HS, I/1, 42; I/6, 355-356

– DBI, 20, 360-369

– C. di Filippo Bareggi, «San Carlo e la Riforma cattolica», in Storia

religiosa della Svizzera, éd. F. Citterio, L. Vaccaro, 1996, 193-246

Auteur(e): Pablo Crivelli / LT

SOURCE : http://www.hls-dhs-dss.ch/textes/f/F10211.php

Biographie de Saint Charles Borromée

Paroisse Saint-Charles à

Marseille > Biographie de Saint Charles Borromée

Humilitas ! Cette devise figurant en lettres d’or

sur le blason familial aurait pu paraître bien incongrue chez les Borromée,

tant ils n’étaient pas habitués à la pratiquer. Il revint pourtant au plus

illustre de leurs enfants de l’illustrer, et de quelle façon !

Sa jeunesse

Deuxième fils du comte Gilbert II Borromée et de

Marguerite de Médicis de Marignan, Charles, né à Arona le 2 octobre 1538, était

par sa mère le neveu du cardinal Jean Ange de Médicis de Marignan.

En 1547, il reçut la tonsure la charge d’abbé

commendataire de l’abbaye d’Arona, dans la province de Manfredonia. Manifestant

déjà la vertu de charité qui marquera toute sa vie, il en reversera la totalité

des revenus aux pauvres.

Le jeune Charles entreprit par la suite des études de

droit canonique et civil à Pavie. En 1559, il devint docteur in utroque jure.

Son père étant mort en 1558, et bien qu’il eût un

frère aîné, Charles fut appelé dès cette date à gérer les affaires de sa

puissante famille. La même année, il reçut également les titres d’abbé

commendataire de San Silano de Romagnano, et prieur commendataire de Santa

Maria di Calvenzano, en percevant ainsi les bénéfices.

A Rome

Le 25 décembre 1559, son oncle maternel fut élu pape

sous le nom de Pie IV. Le nouveau pontife appela immédiatement à Rome ses

neveux Charles et Frédéric Borromée, nommant le premier son secrétaire privé et

administrateur apostolique de Milan. Ce dernier titre titre lui permettait de

gérer les affaires temporelles du diocèse (et d’en percevoir les revenus) sans

avoir à en assumer la charge spirituelle, Charles n’étant même pas prêtre à

cette époque.

Ce n’était qu’un début, car il a plu au nouveau pape

de combler son neveu de titres et d’honneurs : en 1561, et bien que n’étant que

simple clerc tonsuré, Pie IV le créa cardinal et en fit son secrétaire d’Etat

(à l’époque cardinal-neveu, ce qui correspondait effectivement à sa situation).

Charles fut également légat apostolique à Bologne, en Romagne et dans les

Marches, archiprêtre de la basilique Sainte Marie Majeure et Préfet de la

Congrégation Consistoriale.

En 1562, le comte Frédéric Borromée, frère aîné de

Charles, mourut brusquement. Sa famille insista pour que Charles renonce à ses

charges ecclésiastiques et fonde une famille. Mais Charles avait déjà choisi de

ne rien préférer à l’amour de Dieu et en 1563 il reçut successivement le

sacerdoce et l’épiscopat, devenant ainsi archevêque de Milan.

Le concile de Trente était alors suspendu depuis près

de huit ans, sans avoir terminé ses travaux. Ce fut l’une des grandes oeuvres

de Charles de persuader son oncle mais également les divers souverains d’Europe

de convoquer la dernière session du concile : il y consacra deux ans de

négociations avant que la sainte assemblée puisse se réunir en toute sécurité

et indépendance, sa continuité étant désormais garantie. En 1566, le concile

étant terminé, il revint à Charles de diriger les travaux de rédaction du

Catéchisme du Concile de Trente, lequel est resté en vigueur jusqu’à la

promulgation du Catéchisme de l’Eglise Catholique par Saint Jean-Paul II.

Pendant ses années romaines, Charles s’attacha

également à réformer la chapelle musicale vaticane, exigeant selon les

prescriptions du concile, qu’on cherchât à obtenir l’intelligibilité des

paroles et une musique en rapport avec le texte chanté.

A Milan

A la mort de Pie IV en 1566, Charles se démit de

toutes ses fonctions pour aller résider dans son diocèse de Milan. Celui-ci

était alors dans un état moral et spirituel désastreux, et aucun de ses

archevêques n’y avait résidé depuis plus de quatre-vingt ans.

Le cardinal Borromée, dès son arrivée, donna dans son

diocèse l’exemple de la sainteté et s’attacha à restaurer la discipline selon

les normes de la Contre Réformes voulues par le concile de Trente. C’est avec

raison qu’il est appelé le modèle des évêques et le restaurateur des vertus,

tant il fit preuve pendant son épiscopat d’une science, d’une persévérance et

d’un renoncement à l’amour de soi qui justifient ces titres.

Cette discipline, il se l’imposa d’abord à lui-même,

vivant dans l’ascétisme le plus rigoureux, portant le cilice, allant jusqu’à

dormir par terre (il avait vendu tous ses meubles précieux pour faire un don en

argent aux pauvres) et à ne prendre qu’un repas maigre par jour, voulant ainsi

s’offrir lui-même en victime pour les péchés de son peuple, comme le Christ

s’immola en croix pour ceux du genre humain tout entier.

Tout d’abord, il ouvrit un grand séminaire à Milan, un séminaire helvétique pour former des prêtres devant exercer en Suisse menacée par les progrès du protestantisme, et plusieurs petits séminaires pour assurer au clergé une formation convenable. Il imposa également aux communautés religieuses de revenir à l’observance de leur règle et fit remettre les grilles aux parloirs des couvents.

Dans son oeuvre réformatrice il s’appuya sur les Jésuites, les Théatins et les

Barnabites, et fonda une nouvelle congrégation, les Oblats de Saint Ambroise en

1578.

Se dépensant sans compter, Saint Charles s’attacha

également à visiter chacune des paroisses de son immense diocèse, fit restaurer

ou construire plusieurs églises, monastères et établissements d’enseignement,

et, pour s’assurer de la bonne application des réformes qu’il voulait

introduire, tint pas moins de onze synodes diocésains et six conciles

provinciaux et instaura un conseil permanent pour veiller à l’application de

leurs décisions. A ces assemblées, s’ajouta l’interminable et admirable suite

des mandements généraux ou spéciaux, lettres pastorales, instructions aux

confesseurs, sur la liturgie, la tenue des églises, la prédication, les

sacrements : une véritable encyclopédie pastorale, dont l’ampleur grandiose ne

laisse pas soupçonner la brièveté de l’existence de leur auteur.

Bien évidemment, tous ces changements, cette lutte

incessante contre les abus et dérèglements en tous genres rencontrèrent de

vives résistances, de la part des évêques de la région négligents des affaires

de leur diocèse, du chapitre de la cathédrale imbu de ses privilèges, du clergé

habitué à vivre dans le relâchement moral et la mollesse spirituelle, mais également

de la noblesse lombarde depuis longtemps accoutumée à s’ingérer dans les

affaires de l’Église. L’une des plus fortes fut celle de l’ordre dit des

Humiliés, dont les idées dérivaient en outre vers le calvinisme. L’un des

membres de cet ordre n’hésita pas à commettre un attentat contre Saint Charles

en tirant un coup d’arquebuse dans son dos, alors que le cardinal étant en

prière dans son oratoire privé, ajoutant l’horreur du sacrilège (l’attentat a

été commis dans une chapelle) à celle de la tentative de meurtre. Fort

heureusement, Saint Charles s’en tira avec une éraflure à l’épaule. Bien que

Charles fut prêt à pardonner à son agresseur, l’ordre des Humiliés fut dissous

et ses biens répartis entre d’autres ordres et églises du diocèse.

La sollicitude pastorale de Saint Charles trouva

encore à s’exprimer de façon éclatante pendant la famine de 1570 et surtout

lors de la peste qui affecta Milan en 1576 et 1577. N’hésitant pas à

interrompre une visite pastorale pour rentrer en ville malgré le danger de la

contagion, il porta secours aux malades autant qu’il le pouvait. L’Histoire a

surtout retenu à cette occasion la grande procession dont il prit la tête,

pieds nus et la corde au cou, tenant en mains une croix de bois dans laquelle

avait été enchâssée la relique du Saint Clou, à la suite de quoi l’épidémie

cessa.

Mort et canonisation

A la fin d’octobre 1584, s’étant retiré au Sacro Monte

de Varallo pour méditer sur la Passion de Notre Seigneur, Saint Charles,

affaibli par les mortifications, tomba malade. Ramené en litière et atteint

d’une forte fièvre jusqu’à Milan, il s’éteignit dans la nuit du 3 au 4 novembre

1584 à l’âge de 46 ans, couché sur le sac et la cendre, les yeux fixés sur le

crucifix qu’il tenait à la main.

Il fut béatifié en 1602 et canonisé le 1er novembre

1610 par le pape Paul V. Sa fête, de 3ème classe dans l’église universelle mais

de 1ere classe dans notre paroisse dont il est le patron, est fixée au 4

novembre.

En 1910 le pape Saint Pie X publia l’encyclique Editae

Saepe, célébrant la mémoire de Saint Charles.

Saint Charles est le saint patron des séminaristes et

des directeurs spirituels. Il repose dans la cathédrale de Milan.

Saint Charles est ainsi l’un des plus beaux ornements

de l’Eglise au XVIè siècle. La collecte de la messe de sa fête résume,

admirablement et en peu de mots ce que fut sa vie : pastoralis sollicitudo

gloriosum redidit (la sollicitude pastorale le rendit glorieux).

Sancte Carole, gloriose patrone, ora pro nobis !

Successeur de Saint Ambroise, vous fûtes l’héritier de son zèle pour la maison

de Dieu. Votre action fut puissante aussi dans l’Eglise, et vos deux noms, à

plus de mille ans d’intervalle, s’unissent dans une commune gloire. Puissent de

même s’unir au pied du trône de Dieu vos prières au profit de nos temps amoindris

; puisse votre crédit au Ciel nous obtenir des chefs dignes de continuer, de

reprendre au besoin, votre oeuvre sur terre ! Elle éclata de vos jours en

pleine évidence, cette parole des Saints Livres : « tel le chef de la

cité, tels sont les habitants », et cette autre encore :

« j’enivrerai de grâce les âmes sacerdotales et mon peuple sera rempli de

mes biens, dit le Seigneur ». (Dom Guéranger)

SOURCE : http://paroisse-saint-charles.fr/WordPress3/biographie-saint-charles-borromee/

Orazio Borgianni (1574–1616), San Carlo Borromeo, circa 1612, 217 x 151, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

Benoît XVI évoque Charles Borromée, saint patron de

Karol Wojtyla

Allocution du pape à l’angélus de midi

NOVEMBRE 04, 2007 00:00ZENIT STAFFEGLISES

LOCALES

ROME, Dimanche 4 novembre 2007 (ZENIT.org) – Benoît XVI a évoqué le grand

évêque Charles Borromée, saint patron de Karol Wojtyla, avant la prière de

l’angélus dominical place Saint-Pierre, à midi.

Le pape rappelait quelques traits biographiques et

spirituels de ce grand archevêque de Milan : « Sa figure se détache au XVI e s.

comme modèle de pasteur exemplaire par sa charité, sa doctrine, son zèle

apostolique, et surtout, par sa prière : « les âmes, disait-il, se conquièrent

à genoux ». Consacré évêque à 25 ans, il mit en pratique la consigne du concile

de Trente qui imposait aux pasteurs de résider dans leurs diocèses respectifs,

et il se consacra totalement à l’Eglise ambrosienne ».

Le pape expliquait que l’évêque visita son diocèse «

trois fois, de long en large », mais aussi qu’il « convoqua six synodes

provinciaux et onze diocésains ; il fonda des séminaires pour la formation

d’une nouvelle génération de prêtres ; il construisit des hôpitaux et destina

les richesses de sa famille au service des pauvres ; il défendit les droits de

l’Eglise contre les puissants, renouvela la vie religieuse et institua une

congrégation nouvelle de prêtres séculiers, les Oblats ».

Sa charité méprisa le danger lorsque la peste sévit en

1576 : « Il visita les malades et les réconforta et il dépensa pour eux tous

ses biens ».

« Sa devise tenait en un seul mot : « Humilitas ».

L’humilité le poussa, comme le Seigneur Jésus, à renoncer à lui-même pour se

faire le serviteur de tous », ajoutait le pape.

Benoît XVI évoquait aussi son « vénéré prédécesseur

Jean-Paul II qui portait son nom avec dévotion » et il confiait « à

l’intercession de saint Charles tous les évêques du monde, invitant les fidèles

à invoquer pour eux « la céleste protection de la très sainte Vierge Marie,

Mère de l’Eglise ».

En polonais, le pape ajoutait : « Je salue les

Polonais présents et ceux qui s’unissent à nous grâce à la radio et la

télévision. C’est aujourd’hui la mémoire de saint Charles Borromée, patron de

baptême de Jean-Paul II. Remercions Dieu pour la vie et l’œuvre de ces deux

grands hommes de l’Eglise, éloignés dans le temps mais proches dans l’Esprit.

Que Dieu vous bénisse ! ».

SOURCE : https://fr.zenit.org/2007/11/04/benoit-xvi-evoque-charles-borromee-saint-patron-de-karol-wojtyla/

Le sens de l’Avent

Voici, mes bien-aimés, ce

temps célébré avec tant de ferveur, et, comme dit l’Esprit Saint, temps de la

faveur divine, période de salut, de paix et de réconciliation ; temps

jadis désiré très ardemment par les vœux et les aspirations instantes des anciens

prophètes et patriarches, et qui a été vu enfin par le juste Siméon avec une

joie débordante ! Puisqu’il a toujours été célébré par l’Église avec tant

de ferveur, nous-mêmes devons aussi le passer religieusement dans les louanges

et les actions de grâce adressées au Père éternel pour la miséricorde qu’il a

manifestée dans ce mystère.

Du fait que ce mystère

est revécu chaque année par l’Église, nous sommes exhortés à rappeler sans

cesse le souvenir de tant d’amour envers nous. Cela nous enseigne aussi que l’avènement

du Christ n’a pas profité seulement à ceux qui vivaient à l’époque du Sauveur,

mais que sa vertu devait être communiquée aussi à nous tous ; du moins si

nous voulons, par le moyen de la foi et des sacrements, accueillir la grâce

qu’il nous a méritée et diriger notre vie selon cette grâce en lui obéissant.

L’Église nous demande

encore de comprendre ceci : de même qu’il est venu au monde une seule fois

en s’incarnant, de même, si nous enlevons tout obstacle de notre part, il est

prêt à venir à nous de nouveau, à toute heure et à tout instant, pour habiter

spirituellement dans nos cœurs avec l’abondance de ses grâces.

St Charles Borromée

Charles Borromée (†

1584), archevêque de Milan, fut un des acteurs du concile de Trente et en

rédigea largement le catéchisme en 1566. Il fut canonisé en 1610.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/dimanche-27-novembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

4 novembre

Saint Charles Borromée

Ayant un grand respect des choses de Dieu et de ses

saints, ainsi que de tous les ordres de la sainte Eglise et de votre pasteur,

et veillez à les observer intégralement.

Tournez constamment vos regards vers la Providence de

Dieu, dans la pensée que rien n'arrive sans sa volonté et que tout doit tourner

à bien.

Gardez-vous d'entretenir la curiosité de savoir les

actions d'autrui, ou d'être avides de nouveautés, principalement dans les

choses de la foi, et ne parlez pas de ce que vous ignorez.

Défendez-vous de croupir dans la paresse, c'est le

poison de l'âme : mais efforcez-vous de vos occuper des oeuvres pies, ou tout

au moins à des choses utiles.

Evitez de travailler avec l'argent ou les biens

d'autrui, à moins que vous n'y soyez contraints par raison de charité. Et ne

vous laissez entraîner à aucune action injuste, opposée à la volonté de Dieu,

ni pour le gain, ni par amitié, ni par amour des vôtres.

Si la fécondité de la vie conjugale est, certes, chose

bonne, meilleure est la chasteté virginale, et par-dessus tout est excellente

la fécondité virginale.

On ose dire qu'il faut s'accommoder au temps, comme si

l'Esprit de Jésus-Christ et les règles de l'Evangile devaient changer avec le

temps, et être asservis aux sentiments et aux affections des hommes. Au lieu

que l'on doit travailler au contraire à rendre tous les temps conformes aux

ordonnances de l'Eglise, et à réformer tout ce qui s'y trouve défectueux, par

la rectitude immuable de l'esprit évangélique et apostolique. Car c'est la

chair et le sang et non pas l'Esprit de Dieu qui a fait que notre siècle est

devenu incapable de cette vertu si pure et si simple des anciens Pères. C'est

l'esprit humain qui, voulant satisfaire ses désirs, trouve toujours mille

défenseurs et des raisons apparentes pour se couvrir et se défendre. Mais les

paroles de Dieu et les règles des saints demeurent toujours fermes. Elles n'ont

pas été établies pour changer avec le temps, mais pour être inviolables et

immuables en tous temps, et pour se soumettre et s'assujettir tous les temps.

Pourquoi cette église, qui est la vôtre,

demeure-t-elle ainsi sans soins et sans ornements ? Ces murs, ce toit, ce

dallage dénoncent votre irréligion. Ils crient (...) Votre église que vous

honorez et que vous aimez si peu, vous êtes capable de la négliger à ce point ?

O Combien votre indifférence extérieure témoigne de la tiédeur de vos âmes !

Charles Borromée, second fils du comte Gibert et de

Marguerite de Medici, sœur du futur Pie IV, naquit sur la rocca (roc

ou château fort) Borromeo d'Arona, près du lac Majeur, le 2 octobre 1538. Dès

1550 il reçut l'habit clérical et les revenus de l'abbaye locale de San

Gratiniano.

Etudiant à l'université de Pavie, il était sérieux et

studieux, précis, net et volontaire plus solide que brillant, avide de livres,

mais souvent sans argent. A la fin de 1559, il fut reçu docteur en droit canon

et en droit civil.

En janvier 1560, ce jeune homme de vingt-deux ans fut

appelé à Rome par son oncle qui venait d’être élu pape sous le nom de Pie IV.

Cardinal dès le 31 janvier, bien qu’il ait obligation de résider à Rome, il est

nommé administrateur du diocèse de Milan, des légations de Bologne et de

Romagne, puis des Marches, en même temps qu’il reçoit en commende plusieurs

abbayes. Pie IV qui voulait un homme dévoué et actif au sommet de son

administration fait de Charles Borromée ce que sera plus tard le

secrétaire d'Etat. Au début, on le trouvait trop regardant, par comparaison

avec d'autres princes de l'Eglise, qui gaspillaient avec une prodigalité de

grands seigneurs. Pour compléter sa culture, le jeune cardinal fonda chez lui

une académie des Nuits vaticanes, allusion au Nuits

attiques du païen Aulu-Gelle. Chaos - c'était le pseudonyme de

Charles Borromée - commenta la quatrième Béatitude, condamna la luxure et loua

la charité.

Restait à achever le concile de Trente, ouvert en

1545. Pie IV y réussit en 1562-1563, grâce au dévouement de son neveu, qui

assuma l'écrasante besogne de la correspondance avec les agents du Saint-Siège,

nonces et légats du concile. Plutôt simple exécutant que conseiller, selon

un ambassadeur vénitien, il travaillait même la nuit, rédigeait de brefs

rapports sur les nouvelles qui lui arrivaient de partout, répontait à toute la

correspondance pontificale et s’occupait des affaires courantes.

En novembre 1562, quand mourut Frédéric, son frère

aîné, on se demanda si le Charles quitterait les Ordres pour perpétuer sa race,

mais, le 17 juillet 1563 il fut ordonné prêtre et, en décembre, il reçut

la consécration épiscopale. Il restreignit son train de maison, augmenta ses

veilles, ses jeûnes et ses austérités, se refusa tout divertissement, fût-ce

une innocente promenade. Les Nuits vaticanes se muèrent en conférences

religieuses. Un bref de Pie IV autorisait le cardinal-neveu à faire sortir,

pour ses travaux, livres et manuscrits de la Bibliothèque vaticane et Charles

Borromée, malgré une certaine timidité, s'exerça à l'éloquence sacrée.

Après que Charles Borromée avait rendu à Rome les

services que l’on attendait de lui, fort du concile de Trente qui imposait la

résidence aux évêques, il voulut s’installer à Milan où il entra solennellement

23 septembre 1565, après avoir, comme légat, effectué un voyage au centre et au

nord de l'Italie. Il dut revenir à Rome près de son oncle mourant et, le

conclave ayant élu Pie V, il rentra à Milan (avril 1566). Saint Pie V lui

témoigna d’autant plus d'estime et de confiance qu’il était fort lié à

Séraphin Grindelli, chanoine régulier du Latran et son aumônier.

Le cardinal de Milan, passa désormais le reste de sa

vie dans son vaste archidiocèse, à l’exception de brefs séjours romains.

Charles Borromée, à la tête de quinze suffragants, avec juridiction sur des

terres vénitiennes, génoises, novaraises et aussi suisses, puisqu’il avait été

nommé, en mars 1560, protecteur de la nation helvétique, avec juridiction

spirituelle sur plusieurs cantons ; il n’obtint un nonce que sous Grégoire

XIII. Charles Borromée visita la Suisse (notamment les trois vallées ou trois

lignes du Tessin en 1567, les cantons allemands en 1570, 1581, 1583),

s'enquérant des abus, rédigeant des ordonnances, entretenant une lourde

correspondance, se bataillant contre des magistrats et des fonctionnaires

civils souvent revêches, tandis qu’il restait courtois, souple et habile. En

général, il se montra fin connaisseur et manieur d'hommes, sa vertu

perfectionnait ses dons naturels. Il lui arrivait cependant de se raidir, par

exemple contre l'usage invétéré de suspendre dans les églises des écussons et

trophées en mémoire de hauts faits militaires, allant jusqu'à lancer l'interdit

contre des paroisses récalcitrantes, mais un ordre exprès de Rome l'obligea à

désarmer. Il réussit à maintenir catholique une partie de la Suisse allemande,

il favorisa les capucins (à Altdorf en 1581) et les jésuites, dont les collèges

de Lucerne et de Fribourg sont en partie le fruit de son zèle.

Si la richesse avait alors gâté dans la chrétienté une

partie du haut clergé, la pauvreté avait avili le bas clergé, victime d'un

recrutement inconsidéré, de l'abandon où le laissaient ses supérieurs et de

l'ignorance.

L'Eglise avait pâti, et pâtissait encore, en ce

temps-là, des empiétements parfois scandaleux du civil sur l'ecclésiastique

dans les territoires espagnols, et même dans les Etats pontificaux. Les évêques

avaient trop pris l'habitude de vivre hors de leur diocèse, et le clergé

volontiers flagornait le pouvoir civil pour en tirer des avantages matériels.

En Lombardie administrée par les Espagnols, il souffrit de la morgue des hidalgos et

de leurs prétentions. Ses contre-attaques pour sa liberté embarrassèrent

parfois la Cour romaine, obligée de ménager le tout-puissant Philippe II.

Appuyé par son peuple, Charles Borromée s'opposa net à l'introduction chez lui

de l'Inquisition espagnole, au profit de la romaine. Il lutta contre les

gouverneurs de Milan : Alburquerque, Requesens, qu'il excommunia en 1573,

Ayamonte. Pour se rendre populaire, Ayamonte donna en 1579 un grand éclat aux

fêtes du carnaval. Borromée riposta par un édit excommuniant tous ceux qui y

assisteraient. L’année suivante, seul un escadron de cavalerie, en service

commandé, fit les frais des réjouissances, tandis que la femme du gouverneur

interdisait à ses fils d’y participer. Ayamonte mourut en avril 1580 réconcilié

avec l'Eglise ; ses furent pacifiques et pleins de déférence pour le redoutable

cardinal.

Ce chef austère payait de sa personne. Il suffisait de

le voir pour sentir ce qu'était la discipline ecclésiastique. Devant les

décadences, il était une résurrection. Il sut consolider dans son diocèse la

religion, développer le culte eucharistique et le sens moral. Son peuple, dans

l'ensemble, l'admirait et le soutenait, mais ses réformes, exécutées d'une main

forte, soulevèrent quelques résistances dans le clergé : en août 1569, les

chanoines de Santa Maria della Scala, à Milan, soutenus par Alburquerque,

le repoussèrent quand il voulut entrer dans leur basilique. Les Humiliés,

congrégation milanaise enrichie par le commerce de la laine, avaient perdu la

ferveur. Borromée voulut y ramener l'ordre. Un religieux du couvent de Milan,

Jérôme Donato, dit Farina, tira un coup d'arquebuse presque à bout portant

sur le cardinal qui priait dans sa chapelle avec le personnel de sa maison (26

octobre 1569). Borromée eut ses vêtements troués sur l'épine dorsale, mais,

n’étant pas blessé, il fit achever la prière. Peu après, une bulle supprimait

le premier ordre des Humiliés. Par la suite, leur tiers ordre fusionna

avec des confréries similaires. Quant aux Humiliés du second ordre,

qui étaient restées saines, elles survécurent jusque vers 1807.

L'archevêque voulait des auxiliaires intelligents et

dévoués : il les choisit volontiers parmi les nouveaux ordres de clercs

réguliers récemment créés. Charles Borromée était très personnel dans son

gouvernement ; il essaya d'imposer un général de son choix aux

dominicains, et aux jésuites. Il voulait que chez lui les religieux fussent à

lui. Il écrivait en décembre 1577 : Eux (les prêtres de l'Oratoire)

entendent que cette congrégation de Pères qui s'établira ici existe comme

membre de celle de Rome et dépende de là-bas, et moi j'entends qu'elle dépende

absolument d'ici, tout en désirant utiliser ces Pères de Rome pour commencer et

diriger cette œuvre. Charles Borromée retira aux Jésuites la direction de

son grand séminaire, trop indépendants, et créa à son usage les oblats de

Saint-Ambroise dont il composa lui-même la règle. Après sa canonisation,

en 1611, la congrégation s'intitula des Saints-Ambroise-et-Charles.

Charles Borromée créa des sanctuaires devenus

célèbres, des séminaires, des collèges laïcs, un refuge pour repenties, un

mont-de-piété. Il avait revu soigneusement les premiers statuts du

mont-de-piété de Rome, vers 1565, en qualité de protecteur de l'ordre

franciscain. Il fit adopter des sages mesures de contrôle contre la fraude ou

les malversations : il fut le bienfaiteur de l'institution. Il organisa

des confraternités comme celles du Saint-Sacrement, du Saint-Rosaire.

Il mit beaucoup d'ardeur à promouvoir l'œuvre catéchétique du saint prêtre

Castellino da Castello. Lui-même commentait volontiers l'Evangile : par

les moyens les plus simples, il en tirait des applications très variées pour

ses auditeurs et, par son exemple, il sut réveiller chez son clergé le goût de

l'éloquence sacrée. Avec un grand dévouement, il visita les peuples de son

diocèse et des diocèses suffragants ; comme les vivres étaient chers, il avait

stipulé que l'entretien de sa suite ne serait pas à la charge de la mense

épiscopale.

Au total, le cardinal vit plus de mille paroisses,

convoqua onze synodes diocésains et six conciles provinciaux. Lors de la

terrible peste de 1576-1577, compliquée d'une famine, Charles Borromée vendit

sa principauté napolitaine d'Oria pour soulager la misère publique.

Il mourut à Milan le samedi 3 novembre 1584 au soir.

Dans une lettre d'Arona, datée du 1er novembre, il disait que la fièvre le

dévorait et qu'il allait cesser ses visites pastorales pour regagner Milan afin

de recevoir son beau-frère le comte Annibal d'Altaemps et lui faire fête quatre

ou cinq jours. Il venait d’inaugurer un séminaire (30 octobre) et de consoler

les gens de Locarno où la peste avait fait passer la population de 4800 à

700 habitants.

Pour lui, Charles Borromée fut dur : peu de

nourriture et peu de sommeil, aucun confort ni aucun luxe personnel.

Intelligence claire et administrateur plutôt que de penseur, sa bibliothèque

était un instrument de travail. Il priait profondément et largement. Il reste,

dans l'Eglise militante, une grande figure de chef. Son blason

portait : Humilitas. Au physique, il était de belle taille, avec

de vastes yeux bleus, un nez aquilin puissant, le teint pâle sous des cheveux

bruns ; jusqu'en 1574, il porta une barbe courte, rousse, négligée ;

puis, ayant ordonné au clergé de se raser, il donna l'exemple.

Le 4 novembre 1601, à Milan, au lieu de chanter le

service accoutumé pour son anniversaire, on organisa, sur le conseil de Baronius,

une grandiose manifestation de vénération publique. En 1602, et les années

suivantes, ce témoignage fut de plus en plus éclatant. En 1610, Rome canonisa

Charles Borromée qui obtint vite un culte populaire : son origine

patricienne, sa dignité cardinalice, son génie réformateur, les œuvres de son

zèle pastoral pour le clergé et le peuple, sa charité pour les pauvres, son

dévouement lors de la peste le redirent rapidement cher au peuple chrétien,

notamment aux Pays-Bas espagnols où l'imagerie anversoise vulgarisa l'homme de

prière ou le consolateur des pestiférés. Son influence fut très grande en

France.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/11/04.php

Tanzio da Varallo. Carlo Borromeo comunica

un appestato, 1616

Saint Charles Borromée, le cardinal qui soignait les

malades de la peste

Thérèse

Puppinck - Publié le 03/11/20 - Mis à jour le 03/11/21

En 1576, alors que la ville de Milan est ravagée par

la peste, saint Charles Borromée, célébré par l'Église ce 4 novembre, fait

preuve d'un dévouement extraordinaire auprès des malades et mène des actions

rapides pour limiter la propagation du mal.

Saint Charles Borromée est un des grands prélats

italiens du XVIe siècle. Il est connu pour sa participation active au concile

de Trente, notamment dans la rédaction du célèbre catéchisme appelé aujourd’hui

catéchisme du concile de Trente. Dans son diocèse de Milan, saint Charles eut à

cœur de faire appliquer la réforme catholique issue du concile dans un esprit

de charitable pédagogie. Toutefois, les Milanais se souviennent davantage de

son action énergique et spectaculaire lors de la terrible peste qui ravagea la

ville durant les derniers mois de l’année 1576.

Dès le début de la propagation de cette redoutable

maladie, que la médecine de l’époque ne sait pas soigner, l’évêque propose son

assistance aux autorités civiles, et il conseille le gouverneur pour mettre en

place les premières mesures prophylactiques destinées à limiter la propagation

du mal. Immédiatement, on décide la fermeture des portes de la ville afin

d’empêcher l’arrivée de nouveaux pestiférés, car la maladie vient des villes

environnantes. Autre mesure élémentaire pour restreindre la contagion : séparer

les malades des biens portants. Ainsi, à la moindre suspicion de peste, les

habitants sont envoyés au lazaret. Mais rapidement, celui-ci ne suffit pas, et

les autorités organisent la construction, en dehors de la ville, de plusieurs

centaines de cabanes pour recevoir les malades.

De la santé du corps à la santé de l’âme

Saint Charles ne conçoit pas de laisser les pesteux et

les mourants sans réconfort. Il sait combien le soutien affectif, et surtout

spirituel, est fondamental en période d’épidémie. La santé de l’âme est plus

importante que celle du corps, estime le pieux évêque. A quoi bon soulager le

corps si l’âme est malade ? Il décide alors d’aller tous les jours visiter

les pestiférés pour les réconforter, les confesser et leur donner la sainte

communion. Son courage et son élan de générosité entraînent d’autres prêtres et

religieux. Progressivement, ces ecclésiastiques viennent à leur tour apporter

les secours de la religion aux malades, qui, sans eux, seraient dans une

profonde solitude et une profonde détresse.

L’acceptation du risque de la maladie par amour de

Dieu et des âmes n’empêche pas l’évêque de Milan de suivre les recommandations

médicales pour se protéger et empêcher la contagion. Ainsi, Charles désinfecte

toujours ses vêtements au vinaigre, et il refuse désormais de se faire servir,

ne souhaitant pas exposer les serviteurs du palais épiscopal. Comme il risque

chaque jour d’être infecté, il se promène avec une longue baguette qui lui

permet de maintenir une distance de sécurité quand il rencontre des biens

portants. Il préconise les mêmes mesures préventives à tous ceux qui approchent

les pestiférés. Mais plus que tous les moyens terrestres, Mgr Charles Borromée

s’abandonne totalement à la volonté de son Père céleste. Il encourage les

prêtres à conserver une âme à la fois ardente, entièrement dévouée à leur

ministère, et tranquille, pleinement confiante en Dieu. Force est de constater

que sa confiance ne fut pas vaine, puisque, malgré une exposition quasi

journalière à la maladie, Charles ne fut pas atteint par la peste.

Un confinement strict

Au mois d’octobre, quelques semaines après le début de

l’épidémie, les autorités civiles publient un édit de quarantaine :

interdiction est faite à tous les habitants de sortir de leur demeure, sous

peine de mort. L’isolement profond entraîné par ce confinement, la crainte du

mal toujours menaçant, la préoccupation du sort des parents et des amis, les

premières atteintes de la maladie, tout contribue à aggraver encore plus la

détresse des Milanais. Leur pasteur sent combien cette situation est

douloureuse pour le cœur, mais aussi dangereuse pour l’âme. Il décide de réagir

en conséquence et commence par prévenir la municipalité que ses prêtres ne vont

pas respecter la quarantaine. Le gouverneur, qui a déserté la ville quelques

jours après le début de l’épidémie pour se réfugier à la campagne, se retrouve

impuissant face à la détermination de Charles. De plus, il comprend les

bienfaits d’une présence spirituelle pour maintenir la santé morale des

habitants. L’évêque répartit ensuite les équipes sacerdotales entre le

ministère des pestiférés et le ministère des confinés, et il cherche les moyens

de transmettre aux fidèles les grâces sacramentelles malgré le confinement.

Tout d’abord, saint Charles incite les habitants à une

prière plus fréquente et plus intense, en leur proposant des lectures

spirituelles et la récitation des litanies. Puis il fait sonner les cloches de

la ville sept fois par jour, afin d’inviter les habitants à se recueillir tous

ensemble au même moment. Des prêtres déambulent dans les rues en priant à voix

haute, et les fidèles, de leurs fenêtres, leur donnent la réplique. Quand ils

souhaitent se confesser, ils appellent le prêtre qui les confesse alors sur le

pas de la porte. Enfin, Charles fait construire à travers la ville dix-neuf

colonnes surmontée d’une croix. Un autel est installé au pied de chacune

d’elle, et la messe y est célébrée tous les jours. Postés à leurs fenêtres, les

habitants peuvent se tourner vers les croix dressées dans le ciel, et prendre

ainsi part aux messes. Les prêtres portent ensuite la communion aux fidèles, à

travers les fenêtres ou sur le pas des portes. La quarantaine est partiellement

levée à la fin du mois de décembre et la peste quitte progressivement la ville

durant les mois suivants.

Charles Borromée mourut en 1584 ; il fut canonisé

dès 1610. Son action à Milan contribua à la reconnaissance de l’héroïcité de

ses vertus. Pendant ces semaines éprouvantes d’épidémie, saint Charles n’hésita

pas à bousculer les règlements et les conventions sociales, et il eut le

courage de risquer sa vie, par amour du Christ et des âmes. Son dévouement

auprès des prêtres et des fidèles de son diocèse lors cette épidémie lui a valu

d’être déclaré saint patron des évêques.

Cet Italien est à

l’origine du confessionnal

Anna Ashkova - publié

le 03/11/22

C’est au XVIe siècle

qu’est apparu le confessionnal. On doit l’usage de cet isoloir clos à un

cardinal italien devenu saint, Charles Borromée, que l'Église fête le 4

novembre.

S’il est moins utilisé de

nos jours, le confessionnal fait partie intégrante de l’histoire de

l’Église catholique. N’est-ce pas cette petite cabine qui vient bien souvent à

l’esprit lorsqu’on évoque le sacrement de réconciliation ? Sans parler des

films et des séries qui le mettent encore en valeur lors des scènes de

confession. Mais cet isoloir clos n’est pas si ancien. Il n’a été créé qu’au

XVIe siècle. En effet jusqu’à cette date la confession se

faisait de différentes manières.

Au IIIe siècle, la

confession ne se fait qu’une fois dans sa vie et publiquement. À partir du IVe

siècle, le prêtre l’entend en privé et donne une « pénitence »

proportionnée aux péchés confessés. Les chrétiens se confessent alors plusieurs

fois dans leur vie. Tout change en 1215 lors du concile de Latran, sous le pape Innocent III. La confession

a lieu alors chaque année avant la fête de Pâques. Elle est faite sur un banc (sedes

confessionnalis), et le pénitent reçoit l’absolution à genoux. Un siècle plus

tard, la question de la discrétion de la confession se pose.

Soucis d’anonymat et de

discrétion d’échanges

Certains conciles locaux

recommandent de confesser les hommes in secretario, dans la sacristie

fermée. Pour les femmes, il est conseillé au prêtre d’en être séparé par une

petite cloison verticale dont le centre est percé d’une grille et le bas muni

d’un agenouilloir. Entre 1545 et 1563, le Concile de Trente consacre une

session entière au sacrement de pénitence. C’est à ce moment là qu’est définit

l’obligation de confesser tous les péchés mortels avant la communion. C’est

donc durant la Contre-Réforme que le confessionnal est promu pour la première

fois. Et on attribue l’origine de ce meuble liturgique à saint Charles Borromée, l’un des grands prélats italiens du

XVIe siècle qui a consacré beaucoup de ses œuvres au sacrement de la

confession. Parmi ses écrits qui eurent le plus de succès et la postérité la

plus riche figurent les Instructions aux confesseurs de sa ville et

de son diocèse.

Lire aussi :Saviez-vous que Padre Pio perdait souvent patience au

confessionnal ?

Ce cardinal-archevêque de

Milan recommande l’usage d’un confessionnal et le rend obligatoire dans la cité

italienne et dans sa province. Sa réputation comme évêque réformateur gagne la

France dès la fin du concile, puis sa mort en 1584, et surtout après sa

canonisation en 1610. Ainsi rapidement, le confessionnal a été adopté par

d’autres pays, dont la France, à la suite des conciles d’Aix-en-Provence (1585)

et de Toulouse (1590). Ce meuble assure l’anonymat entre le confesseur et son

pénitent, et permet la discrétion de l’échange. Entre le XVIIe et XVIIIe

siècles, il bénéficie d’une décoration soignée et devient le lieu presque

unique de la confession dans le catholicisme.

Les confessionnaux clos

de moins en moins utilisés

Depuis le concile de Vatican II, les confessionnaux en forme

d’isoloir sont de moins en moins utilisés même s’ils sont toujours en usage. En

effet, on encourage davantage les confessions en face-à-face. Si le fidèle le

souhaite, il peut ainsi simplement s’asseoir en face du prêtre pour se

confesser ou s’agenouiller sur un prie-Dieu. Une séparation entre pénitent et

confesseur peut être cependant maintenue pour préserver l’anonymat. Un simple

séparation, plus légère, remplace alors les grands confessionnaux anciens. Il

est en effet important que le fidèle puisse choisir sous quelle forme se

déroule la confession afin qu’il reçoive le sacrement de réconciliation dans de

bonnes conditions.

Leçons des Matines (avant 1960)

Quatrième leçon. Charles naquit à Milan, de la noble

famille des Borromée. Une lumière divine, qui brilla la nuit de sa naissance

sur la chambre de sa mère, fit présager combien sa sainteté serait éclatante.

Enrôlé dès son enfance dans la milice cléricale et pourvu quelque temps après

d’une abbaye, il avertit son père de ne pas employer pour sa maison les revenus

de ce’ bénéfice ; et lorsque l’administration lui en fut dévolue, il en

distribua aux pauvres tout le superflu. La chasteté lui fut si chère, qu’il

repoussa avec une invincible constance les femmes impudiques plusieurs fois

envoyées pour lui faire perdre sa pureté. A vingt-trois ans, son oncle le Pape

Pie IV l’ayant agrégé au Sacré Collège des Cardinaux, il s’y distingua par une

piété insigne et par l’éclat de toutes les vertus. Bientôt après, le même Pape

l’ayant fait Archevêque de Milan, il s’appliqua avec beaucoup de sollicitude à

gouverner l’Église qui lui était confiée, selon les règles du concile de

Trente, qui venait d’être terminé, grâce à lui surtout ; et pour réformer les

mœurs déréglées de son peuple, outre qu’il assembla maintes fois des synodes,

il montra dans sa personne un modèle d’éminente sainteté. Il travailla

par-dessus tout à extirper l’hérésie du pays des Rhètes et des Suisses, dont il

convertit un grand nombre à la foi chrétienne.

Cinquième leçon. La charité de cet homme de Dieu

brilla tout particulièrement lorsqu’ayant vendu sa principauté d’Oria, il en

donna aux pauvres, en un seul jour, tout le prix, qui était de quarante mille

pièces d’or. Ce fut avec la même charité qu’il en distribua vingt mille qu’on

lui avait léguées. Il renonça aux amples revenus ecclésiastiques dont il avait

été comblé par son oncle, et n’en retint que ce qui lui était nécessaire pour

lui-même et pour assister les indigents. Pour les nourrir pendant la peste qui

ravagea Milan, il vendit tout le mobilier de sa maison, sans même se réserver

un lit ; de sorte que, depuis, il coucha sur le plancher. Empressé à visiter

ceux que le fléau atteignait, il les soulageait avec une affection de père, et,

leur administrant lui-même les sacrements de l’Église, les consolait d’une

façon merveilleuse. Pendant ce temps, pour se faire médiateur auprès de Dieu

par de très humbles prières et pour détourner sa colère, il ordonna une

procession publique : il y marcha la corde au cou, les pieds nus et

ensanglantés par les pierres contre lesquelles il se heurtait, portant une

croix et s’offrant lui-même comme victime pour les péchés de son peuple. Il fut

un très énergique défenseur de la liberté de l’Église. Mais, comme il avait à

cœur de rétablir la discipline, des séditieux lâchèrent contre lui, pendant

qu’il était en prières, la roue d’une arquebuse ; le projectile l’ayant frappé,

il ne dut qu’à la protection divine d’être préservé de tout mal.

Sixième leçon. Il était d’une abstinence étonnante ;

jeûnait très souvent au pain et à l’eau, et, d’autres fois, se contentait de

légumes. Il domptait son corps par les veilles, un cilice très dur, de

fréquentes disciplines. L’humilité et la douceur lui étaient on ne peut plus

chères. Il ne manqua jamais de se livrer à la prière et à la prédication de la

parole de Dieu, quelque grandes occupations qu’il eût. Il bâtit beaucoup

d’églises, des monastères et des collèges. Il a écrit plusieurs ouvrages très

utiles, surtout pour l’instruction des Évêques, et c’est par ses soins que le

catéchisme des curés a paru. Enfin, il se retira dans une solitude du mont

Varale, où se trouvent des tableaux représentant au vif la passion de notre

Seigneur. C’est là que, menant pendant quelques jours une vie rude par la

mortification volontaire, mais douce par la méditation des souffrances de

Jésus-Christ, il fut pris de la fièvre, et comme la maladie s’aggravait, il

revint à Milan, où, sous la cendre et le cilice, les yeux attachés sur un

crucifix, il partit pour le ciel, âgé de quarante-sept ans, le troisième jour

des nones de novembre de l’année mil cinq cent quatre-vingt-quatre. Des

miracles l’ayant illustré, le Souverain Pontife Paul V le mit au nombre des

Saints.

Daniele Crespi (1598–1630), Supper

of Saint Carlo Borromeo', circa 1620, 190 x 265, Santa Maria della Passione church

in Milan

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Humilitas. A sa naissance au château d’Arona, Charles

trouvait inscrit en chef de l’écu de famille ce mot couronné d’or [1]. Parmi

les pièces nombreuses du blason des Borromées, on disait de celle-ci qu’ils ne

connaissaient l’humilité que dans leurs armes. Le temps était venu où

l’énigmatique devise de la noble maison se justifierait dans son membre le plus

illustre ; où, au faîte des grandeurs, un Borromée saurait vider de soi son

cœur pour le remplir de Dieu : en sorte pourtant que, loin de renier la fierté

de sa race, plus intrépide qu’aucun, cet humble éclipserait dans ses

entreprises les hauts faits d’une longue suite d’aïeux. Nouvelle preuve que

l’humilité ne déprime jamais. Charles atteignait à peine sa vingt-deuxième

année, quand Pie IV, dont sa mère était la sœur, l’appelait au poste difficile

qu’on nomme aujourd’hui la Secrétairerie d’État, et bientôt le créait cardinal,

archevêque de Milan, semblait se complaire à entasser honneurs et

responsabilités sur ses jeunes épaules. On était au lendemain du règne de Paul

IV, si mal servi par une confiance pareille, que ses neveux, les Caraffa, y

méritèrent le dernier supplice. Mais l’événement devait montrer que son doux

successeur recevait en cela ses inspirations de l’Esprit-Saint, non de la chair

et du sang.

Soixante ans déjà s’étaient écoulés de ce siècle de

Luther qui fut si fatal au monde, et les ruines s’amoncelaient sans fin, tandis

que chaque jour menaçait l’Église d’un danger nouveau. Les Protestants venaient

d’imposer aux catholiques d’Allemagne le traité de Passau qui consacrait leur

triomphe, et octroyait aux dissidents l’égalité avec la liberté. L’abdication

de Charles-Quint découragé donnait l’empire à son frère Ferdinand, tandis que

l’Espagne et ses immenses domaines des deux mondes allaient à Philippe II son

fils ; or Ferdinand Ier inaugurait la coutume de se passer de Rome, en ceignant

le diadème mis au front de Charlemagne par saint Léon III ; et Philippe,

enserrant l’Italie par la possession de Naples au Sud, du Milanais au Nord,

semblait à plusieurs une menace pour l’indépendance de Rome elle-même.

L’Angleterre, un instant réconciliée sous Marie Tudor, était replongée par

Élisabeth dans le schisme où elle demeure jusqu’à nos jours. Des rois enfants

se succédaient sur le trône de saint Louis, et la régence de Catherine de

Médicis livrait la France aux guerres de religion.

Telle était la situation politique que le ministre

d’État de Pie IV avait mission d’enrayer, d’utiliser au mieux des intérêts du

Siège apostolique et de l’Église. Charles n’hésita pas. Appelant la foi au

secours de son inexpérience, il comprit qu’au déluge d’erreurs sous lequel le

monde menaçait de périr, Rome se devait avant tout d’opposer comme digue

l’intégrale vérité dont elle est la gardienne ; il se dit qu’en face d’une hérésie

se parant du grand nom de Réforme et déchaînant toutes les passions, l’Église,

qui sans cesse renouvelle sa jeunesse [2], aurait beau jeu de prendre occasion

de l’attaque pour fortifier sa discipline, élever les mœurs de ses fils,

manifester à tous les yeux son indéfectible sainteté. C’était la pensée qui

déjà, sous Paul III et Jules III, avait amené la convocation du concile de

Trente, inspiré ses décrets de définitions dogmatiques et de réformation. Mais

le concile, deux fois interrompu, n’avait point achevé son œuvre, qui restait

contestée. Depuis huit ans qu’elle demeurait suspendue, les difficultés d’une

reprise ne faisaient que s’accroître, en raison des prétentions discordantes

qu’affichaient à son sujet les princes. Tous les efforts du cardinal neveu se

tournèrent à vaincre l’obstacle. Il y consacra ses jours et ses nuits,

pénétrant de ses vues le Pontife suprême, inspirant son zèle aux nonces

accrédités près des cours, rivalisant d’habileté autant que de fermeté avec les

diplomates de carrière pour triompher des préjugés ou du mauvais vouloir des

rois. Et quand, après deux ans donnés à ces négociations épineuses, les Pères

de Trente se réunirent enfin, Charles apparut comme la providence et l’ange

tutélaire de l’auguste assemblée ; elle lui dut son organisation matérielle, sa

sécurité politique, la pleine indépendance de ses délibérations, leur

continuité désormais ininterrompue. Retenu à Rome, il est l’intermédiaire du

Pape et du concile. La confiance des légats présidents lui est vite acquise ;

les archives pontificales en gardent la preuve : c’est à lui qu’ils recourent

journellement, dans leurs sollicitudes et parfois leurs angoisses, comme au

meilleur conseil, à l’appui le plus sûr.

Le Sage disait de la Sagesse : « A cause d’elle, ma

jeunesse sera honorée des vieillards ; les princes admireront mes avis : si je

me tais, ils attendront que je parle ; quand j’ouvrirai la bouche, ils

m’écouteront attentifs, les mains sur leurs lèvres [3]. » Ainsi en fut-il de

Charles Borromée, à ce moment critique de l’histoire du monde ; et l’on

comprend que la Sagesse divine qu’il écoutait si docilement, qui l’inspirait si

pleinement, ait rendu son nom immortel dans la mémoire reconnaissante des

peuples [4].

C’est de ce concile de Trente dont l’achèvement lui

est dû, que Bossuet reconnaît, en sa. Défense de la trop fameuse Déclaration,

qu’il ramena l’Église à la pureté de ses origines autant que le permettait

l’iniquité des temps [5]. Écoutons ce qu’à l’heure où les assises œcuméniques

du Vatican venaient de s’ouvrir, l’évêque de Poitiers, le futur cardinal Pie,

disait « de ce concile de Trente, qui, à meilleur titre que celui même de

Nicée, a mérité d’être appelé le grand concile ; de ce concile dont il est

juste d’affirmer que, depuis la création du monde, aucune assemblée d’hommes

n’a réussi à introduire parmi les hommes une aussi grande perfection ; de ce

concile dont on a pu dire que, comme un arbre de vie, il a pour toujours rendu

à l’Église la vigueur de sa jeunesse. Plus de trois siècles se sont écoulés

depuis qu’il termina ses travaux, et sa vertu curative et fortifiante n’a point

cessé de se faire sentir [6]. »

« Le concile de Trente est demeuré comme en permanence

dans l’Église au moyen des congrégations romaines chargées d’en perpétuer

l’application, ainsi que de procurer l’obéissance aux constitutions

pontificales qui l’ont suivi et complété [7]. » Charles inspira les mesures

adoptées dans ce but par Pie IV, et au développement desquelles les Pontifes

qui suivirent attachèrent leurs noms. La révision des livres liturgiques, la

rédaction du Catéchisme romain l’eurent pour promoteur. Avant tout, et sur

toutes choses, il fut l’exemplaire vivant delà discipline renouvelée, acquérant

ainsi le droit de s’en montrer envers et contre tous l’infatigable zélateur.

Rome, initiée par lui à la réforme salutaire où il convenait qu’elle précédât

l’armée entière des chrétiens, se transforma en quelques mois. Les trois

églises dédiées à saint Charles en ses murs [8], les nombreux autels qui

portent son nom dans les autres sanctuaires de la cité reine, témoignent de la

gratitude persévérante qu’elle lui a vouée.

Son administration cependant et son séjour n’y

dépassèrent pas les six années du pontificat de Pie IV. A la mort de celui-ci,

malgré les instances de saint Pie V, qu’il contribua plus que personne à lui

donner pour successeur, Charles quitta Rome pour Milan où l’appelait son titre

d’archevêque de cette ville. Depuis près d’un siècle, la grande cité lombarde

ne connaissait guère que de nom ses pasteurs, et cet abandon l’avait, comme

tant d’autres en ces temps, livrée au loup qui ravit et disperse le troupeau

[9]. Notre Saint comprenait autrement le devoir de la charge des âmes. Il s’y

donnera tout entier, sans ménagement de lui-même, sans nul souci des jugements

humains, sans crainte des puissants. Traiter dans l’esprit de Jésus-Christ les

intérêts de Jésus-Christ sera sa maxime [10], son programmées ordonnances

édictées à Trente. L’épiscopat de saint Charles fut la mise en action du grand

concile ; il resta comme sa forme vécue, son modèle d’application pratique en

toute Église, la preuve aussi de son efficacité , la démonstration effective

qu’il suffisait à toute réforme, qu’il pouvait sanctifier à lui seul pasteur et

troupeau.

Nous eussions voulu donner mieux qu’un souvenir à ces

Acta Ecclesiae Mediolanensis, pieusement rassemblés par des mains fidèles, et

où notre Saint paraît si grand ! C’est là qu’à la suite des six conciles de sa

province et des onze synodes diocésains qu’il présida, se déroule l’inépuisable

série des mandements généraux ou spéciaux que lui dicta son zèle ; lettres

pastorales, où brille le Mémorial sublime qui suivit la peste de Milan ;

instructions sur la sainte Liturgie, la tenue des Églises, la prédication,

l’administration des divers Sacrements, et entre lesquelles se détache

l’instruction célèbre aux Confesseurs ; ordonnances concernant le for

archiépiscopal, la chancellerie, les visites canoniques ; règlements pour la

famille domestique de l’archevêque et ses vicaires ou officiers de tous rangs,

pour les prêtres des paroisses et leurs réunions dans les conférences dont il

introduisit l’usage, pour les Oblats qu’il avait fondés, les séminaires, les

écoles, les confréries ; édits et décrets, tableaux enfin et formulaire

universels. Véritable encyclopédie pastorale, dont l’ampleur grandiose ne

laisse guère soupçonner la brièveté de cette existence terminée à quarante-six

ans, ni les épreuves et les combats qui, semble-t-il, auraient dû l’absorber

tout entière.

Successeur d’Ambroise, vous fûtes l’héritier de son

zèle pour la maison de Dieu ; votre action fut puissante aussi dans l’Église ;

et vos deux noms, à plus de mille ans d’intervalle, s’unissent dans une commune

gloire. Puissent de même s’unir au pied du trône de Dieu vos prières, en faveur

de nos temps amoindris ; puisse votre crédit au ciel nous obtenir des chefs

dignes de continuer, de reprendre au besoin, votre œuvre sur terre ! Elle

éclata de vos jours en pleine évidence, cette parole des saints Livres : Tel le

chef de la cité, tels sent les habitants [11]. Et cette autre non moins :

J’enivrerai de grâce les âmes sacerdotales, et mon peuple sera rempli de mes

biens, dit le Seigneur [12].

Combien justement vous disiez, ô Charles : « Jamais

Israël n’entendit pire menace que celle-ci : Lex peribit a sacerdote [13].

Prêtres, instruments divins, desquels dépend le bonheur du monde : leur

abondance est la richesse de tous ; leur nullité, le malheur des nations [14].

» Et lorsque, du milieu de vos prêtres convoqués en synode, vous passiez à

l’auguste assemblée des dix-sept pontifes, vos suffragants ; réunis en concile,

votre voix se faisait, s’il se peut, plus forte encore : « Craignons que le

Juge irrité ne nous dise : Si vous étiez les éclaireurs de mon Église, pourquoi

donc fermiez-vous les yeux ? Si vous vous prétendiez les pasteurs du troupeau,

pourquoi l’avez-vous laissé s’égarer ? Sel de la terre, vous vous êtes affadis.

Lumière du monde, ceux qui étaient assis dans les ténèbres et dans l’ombre de

la mort n’ont point vu vos rayons. Vous étiez Apôtres ; mais qui donc éprouva

votre vigueur apostolique, vous qui jamais n’avez rien fait que pour complaire

aux hommes ? Vous étiez la bouche du Seigneur, et l’avez rendue muette. Si

votre excuse doit être que le fardeau dépassait vos forces, pourquoi fut-il

l’objet de vos brigues ambitieuses [15] ? »

Mais, par la grâce du Seigneur Dieu bénissant votre

zèle pour l’amendement des brebis comme des agneaux, vous pouviez ajouter, ô

Charles : « Province de Milan, reprends espoir. Voici que, venus à toi, tes

pères se sont rassemblés dans le but de guérir tes maux ; ils n’ont plus

d’autre souci que de te voir porter des fruits de salut, multipliant à cette

fin leurs efforts communs [16]. »

Mes petits enfants que j’enfante de nouveau, jusqu’à

ce que le Christ soit formé en vous [17] ! C’est l’aspiration de l’Épouse, le

cri qui ne cessera qu’au ciel : et synodes, visites, réformation, décrets

concernant prédication, gouvernement, ministère, ne sont à vos yeux que la

manifestation de cet unique désir de l’Église, la traduction du cri de la Mère

[18] en travail de ses fils [19].

Daignez, bienheureux Pontife, ranimer en tous lieux

l’amour de cette discipline sainte, où la sollicitude pastorale qui vous rendit

glorieux [20] trouva le secret de sa fécondité merveilleuse. Il peut suffire

aux simples fidèles de n’ignorer point que parmi les trésors de l’Église leur

Mère existe, à côté de la doctrine et des Sacrements, un corps de droit

incomparable, œuvre des siècles, objet de légitime fierté pour tous ses fils

dont il protège les privilèges divins ; mais le clerc, qui se voue à l’Église,

ne saurait la servir utilement sans l’étude approfondie, persévérante, qui lui

donnera l’intelligence du détail de ses lois ; mais fidèles et clercs doivent

supplier Dieu que le malheur des temps ne mette plus obstacle à la tenue par

nos chefs vénérés de ces assemblées conciliaires et synodales prescrites à

Trente [21], magnifiquement observées par vous, ô Charles, qui fîtes

l’expérience de leur vertu pour sauver la terre. Veuille le ciel exaucer en

votre considération notre prière, et nous pourrons redire avec vous [22] à

l’Église : « O bénigne Mère, ne pleurez plus ; vos peines seront récompensées,

vos fils vous reviendront de la contrée ennemie. Et moi, dit le Seigneur, j’enivrerai

de grâce les âmes sacerdotales, et mon peuple sera rempli de mes biens [23]. »

1] Le chef de l’écu d’argent, chargé du mot humilitas,

en lettres gothiques de sable, surmonté d’une couronne d’or.

[2] Psalm. CII, 5.

[3] Sap. VIII, 10-12.

[4] Ibid. 13.

[5] Gallia orthodoxa, Pars III, Lib. XI, c. 13 ; VII,

c. 40.

[6] Discours prononcé à Rome, dans l’église de

Saint-André della Valle, le 14 janvier 1870.

[7] Instruction pastorale à l’occasion du prochain

concile de Bordeaux, 26 juin 1830.

[8] Saint-Charles aux Catinari, l’une des plus belles

de Rome ; Saint-Charles au Corso, qui garde son cœur ; Saint-Charles aux

Quatre-Fontaines.

[9] Johan. X, 12.

[10] Acta Eccl. Mediolanensis, Oratio habita in

concil. prov. VI.

[11] Eccli. X, 2.

[12] Jerem. XXXI, 14.

[13] La loi périra, s’éteindra, sera muette, au cœur

du prêtre et sur ses lèvres. Ezech. VII, 26. Acta Eccl. Mediolan.

Constitutiones et regula ; societatis scholarum doctrina : christianae, Cap.

III.

[14] Concio I ad Clerum, in Synod. diœces. XI.

[15] Oratio habita in Concil. prov II.

[16] Oratio habita in Concil. prov. VI.

[17] Gal. IV, 19.

[18] Apoc. XII, 2.

[19] Concio I ad Clerum, in Synod. diœces. XI.

[20] Collecte de la fête.

[21] Sessio XXIV, de Reformatione cap. II.

[22] Concio I ad Clerum, in Synod. XI.

[23] Jerem. XXXI, 16, 14.

Johann Michael Rottmayr . Intercession

de Charles Borromée supporté par la Vierge

Marie,

1714. Fresque, dôme de l'Église Saint-Charles-Borromée,

Vienne.

Bhx Cardinal Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Si Milan regarde saint Charles comme le plus illustre de ses pasteurs depuis saint Ambroise, l’Église Mère de Rome le serre sur son cœur et le salue comme l’un des plus chers et des plus méritants de ses enfants.

En effet, l’œuvre de saint Charles peut être considérée en deux périodes et sur deux champs distincts. D’abord son activité aux côtés de son oncle Pie IV, activité qui embrassa non seulement Rome mais l’Église universelle elle-même. Vient ensuite l’action pastorale accomplie à Milan par le Saint, apôtre et pasteur de ce vaste diocèse.

Secrétaire d’État de Pie IV, saint Charles se trouva aux côtés du Pontife à l’une des époques les plus décisives pour l’histoire de la papauté. Il s’agissait de savoir si le Saint-Siège s’engagerait enfin d’une manière résolue dans la voie de la réforme ecclésiastique, si longtemps et si universellement réclamée ; ou bien s’il ajournerait encore cette difficile entreprise, se contentant, comme malheureusement quelques-uns des Pontifes de ce siècle, de demi-mesures.

Ce fut sous l’influence personnelle de saint Charles que Pie IV se décida pour la réforme ; et de ce jour le Saint, au nom et avec l’autorité de son oncle, marcha hardiment dans la voie ouverte, sans considérations humaines. On peut donc dire que, de Rome, il dirigea la dernière période du Concile de Trente, et ce qui est encore plus important, lorsque le Concile eut été approuvé par le Pape, saint Charles s’appliqua avec toute son énergie à en réaliser effectivement le plan de réforme.

Ici commence la seconde partie de la vie de saint Charles. Pie IV étant mort, il se fixa définitivement dans son Église de Milan, où étaient à relever les ruines accumulées par de longues années de mauvais gouvernement, en l’absence des pasteurs légitimes.

Saint Charles, pour sanctifier son troupeau, commença par se sanctifier lui-même. Comme Jésus avait voulu racheter le monde moins par sa prédication et ses miracles que par sa passion, ainsi saint Charles s’offrit-il comme une victime à Dieu pour son peuple par une vie très austère. Les âmes, disait-il, se gagnent à genoux, faisant ainsi allusion à ses longues prières au pied du Crucifix ou dans la crypte de l’église du Saint-Sépulcre à Milan.

L’activité déployée par saint Charles en toute sorte de labeur pastoral est incroyable. Son champ d’action, à titre de métropolitain de Milan et de légat du Saint-Siège, était immense. Et pourtant il n’y eut pas de village des Alpes ou de pays perdu où saint Charles ne se rendît pour y faire la visite pastorale. Ses biographes nous disent qu’en moins de trois semaines il lui arriva de consacrer quinze églises.

L’archevêque de Milan avait alors à résoudre d’importants et difficiles problèmes. L’hérésie, qui avait infecté les cantons suisses confinant au diocèse, menaçait de contaminer aussi celui-ci. Il fallait tout au moins en paralyser l’influence et saint Charles le fit. Il fallait en outre former des évêques et des prêtres inspirés par l’idéal le plus élevé : le Saint érige des collèges et des séminaires, rassemble des conciles, promulgue des canons, favorise l’ouverture de maisons religieuses pour l’éducation de la jeunesse.

L’affaiblissement de l’esprit ecclésiastique dans le clergé est presque toujours favorisé par le pouvoir civil qui avilit en effet le prêtre pour pouvoir ensuite se l’assujettir plus aisément. Saint Charles fut le vengeur intrépide de l’autorité épiscopale ; aussi non seulement il eut à lutter contre les chanoines, les religieuses et les religieux qui s’étaient écartés de leur route primitive — par exemple les Humiliés qui allèrent jusqu’à tenter d’assassiner le Saint ! — mais il trouva des adversaires beaucoup plus redoutables dans les gouverneurs de Milan, trop jaloux des prétendues prérogatives de la couronne d’Espagne.

Ainsi vécut, agit et combattit le grand saint Charles Borromée, qui se montra le digne champion de la lutte sacrée pour laquelle il s’immola. Usé avant le temps par les dures fatigues de sa vie pastorale, il mourut sur la brèche le 3 novembre 1584, âgé seulement de quarante-six ans.

Dans la collecte de la Messe, l’Église résume son éloge dans ces brèves mais éloquentes paroles : pastoralis sollicitudo gloriosum reddidit.

Rome conserve de lui de nombreux souvenirs, à Saint-Martin-aux-Monts, par exemple, et à Sainte-Praxède, dont il fut titulaire. Son cœur est conservé dans la grande église qui lui est dédiée près de la porte Flaminienne, église qui représente aujourd’hui le sanctuaire particulier des Lombards dans la Ville éternelle. Outre cette église de Saint-Charles au Corso, deux autres sanctuaires de la Ville se parent de son nom ; ce sont : Saint-Charles a’ Catinari et Saint-Charles-aux-Quatre-Fontaines. Dans le palais Altemps on vénère toujours la chambre habitée par le Saint. Quant au manteau de pourpre du grand Cardinal, il est conservé religieusement dans le Titre de Sainte-Cécile.

La messe est du commun Státuit, à l’exception de la

première collecte : « Gardez toujours, Seigneur, votre Église sous la

protection de votre saint pontife Charles ; et de même que la sollicitude

pastorale l’éleva à une si grande gloire, que son intercession nous embrase

aussi du saint amour. »

Bertholet Flemalle (1614-1675), Saint Charles Borromée

et les pestiférés, Cathédrale Saint-Paul, Liège

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide dans l’année liturgique

« Un véritable et grand pasteur d’âmes »