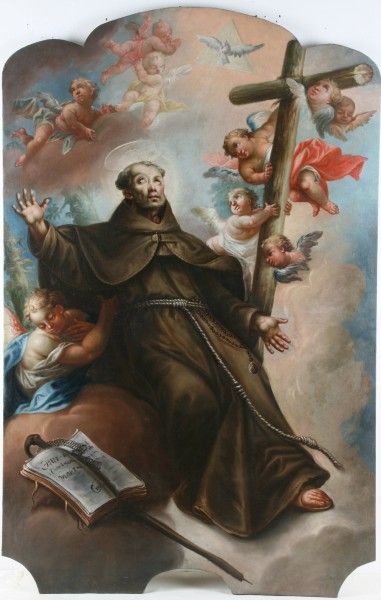

Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–1690), Dos frailes, circa 1675, 228 x 164.4, Museum of Navarre, Pamplona, .

La obra representa a San Pedro de Alcántara junto a otro

fraile franciscano.

Saint Pierre d'Alcantara

Franciscain

espagnol (+ 1562)

Sans aucun doute parmi les nombreux mystiques espagnols, il est l'un des plus grands. Franciscain à 16 ans, il crée une nouvelle branche de l'Ordre, plus austère et plus pauvre: "les franciscains déchaussés." Il sera de ceux qui aidèrent sainte Thérèse d'Avila à réformer le Carmel et même obtint pour elle l'autorisation de fonder à Avila son premier couvent des "carmélites déchaussées". Il connaissait de merveilleuses extases, au point que certains l'accusaient de folie. "Bienheureuses folies, mes sœurs, disait sainte Thérèse d'Avila à propos de saint Pierre d'Alcantara. Plût à Dieu que nous en fussions toutes atteintes." Sa vie ascétique était inimitable: ne manger que tous les trois jours - dormir assis contre une muraille et seulement une heure et demie afin d'avoir le temps de la méditation - ne parler que si on l'interrogeait.

À Arenas en Castille, l'an 1562, saint Pierre d'Alcantara, prêtre franciscain.

Remarquable par son don de conseil, sa pratique de la pénitence et l'austérité

de sa vie, il réforma la discipline régulière dans les couvents de son Ordre en

Espagne et fut le conseiller de sainte Thérèse de Jésus pour sa réforme de

l'Ordre du Carmel.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/2042/Saint-Pierre-d-Alcantara.html

Niche

of St. Peter of Alcantara

Statues of Peter of Alcantara in Malta ; Triq San Pawl (Valletta) ; Triq San Ġwann (Valletta)

Saint Pierre d'Alcantara

de l'Ordre de

Saint-François

(1496-1562)

Ce Saint, issu d'une

famille illustre, fut un prodige d'austérités. Entré dans l'Ordre de

Saint-François, après de brillantes études où avait éclaté surtout son amour

pour les Livres Saints, il montra, pendant son noviciat, une modestie

surprenante; il ne connaissait ses frères qu'à la voix, il ne savait point la

forme de la voûte de l'église; il passa quatre ans au couvent sans apercevoir

un arbre qui étendait ses branches et donnait son ombre près de la porte

d'entrée. Sa vertu extraordinaire l'éleva aux charges de l'Ordre dès ses

premières années de vie religieuse; mais l'humble supérieur se faisait, à toute

occasion, le serviteur de ses frères et le dernier de tous.

Dans un pays de

montagnes, couvert de neige, en plein hiver, il avait trouvé un singulier

secret contre le froid: il ôtait son manteau, ouvrait la porte et la fenêtre de

sa cellule; puis, après un certain temps, reprenait son manteau et refermait

porte et fenêtre. Sa prédication produisit les plus merveilleux effets; sa vue

seule faisait couler les larmes et convertissait les pécheurs: c'était, selon

la parole de sainte Thérèse, la mortification personnifiée qui prêchait par sa

bouche.

Dieu lui inspira de

travailler à la réforme de son Ordre, et il y établit une branche nouvelle qui

se fit remarquer par sa ferveur. Dans ses voyages, Pierre ne marchait que pieds

nus et la tête découverte: la tête découverte, pour vénérer la présence de Dieu;

pieds nus, afin de ne jamais manquer l'occasion de se mortifier. S'il lui

arrivait de se blesser un pied, il ne prenait qu'une sandale, ne voulant pas

qu'un pied fût à son aise quand l'autre était incommodé.

Pierre d'Alcantara fut un

des conseillers de sainte Thérèse d'Avila, qui l'avait en grande considération.

Sa mortification s'accroissait chaque jour au point qu'il ne se servait plus de

ses sens et de ses facultés que pour se faire souffrir; il ne mangeait qu'une

fois tous les trois jours, se contentant de mauvais pain et d'eau; parfois il

demeurait huit jours sans manger. Il passa quarante ans sans donner au sommeil

chaque nuit plus d'une heure et demie, encore prenait-il ce sommeil assis dans

une position incommode; il avoua que cette mortification avait été plus

terrible pour lui que les cilices de métal, les disciplines et les chaînes de

fer.

La seule pensée du

Saint-Sacrement et des mystères d'amour du Sauveur le faisait entrer en extase.

Saint Pierre d'Alcantara fit de nombreux miracles. Apparaissant à sainte

Thérèse après sa mort, il lui dit: "O bienheureuse pénitence, qui m'a valu

tant de gloire!"

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_pierre_d_alcantara.html

Saint Pierre d'Alcantara, Interior of Église Saint-Hilaire de Givet

Saint Pierre d'Alcantara, Interior of Église Saint-Hilaire de Givet

Pierre Garavito né en

1499 à Alcantara, petite ville de la province espagnole d'Estramadure, où son

père était gouverneur. A quatorze ans, il perdit son père, sa mère se remaria

et il partit étudier les arts libéraux, la philosophie et le droit canon à

l'université de Salamanque où il décida d'entrer chez les Frères Mineurs dont

il reçut l'habit, en 1515, au couvent de Los Majaretes. En 1519 il est choisi

comme gardien du couvent de Badajoz ; ordonné prêtre en 1524, il commença une

si brillante carrière de prédicateur qu'on l'appelât à la cour du Portugal. Élu

provincial de son Ordre (province Saint-Gabriel) en 1538, instaure un régime

très austère et, son mandat terminé, il se retire dans un désert, à

l'embouchure du Tage, où il fonde un couvent d'ermites (1542). Rappelé dans sa

province (1544), il y fonde, près de Lisbonne, un couvent qui sera le germe

d'une province nouvelle (1550). Lors d'un voyage à Rome, il reçoit

l'approbation de Jules III pour expérimenter une réforme radicale, sous la

juridiction des mineurs observants dont le commissaire général le nomme

commissaire général des mineurs réformés d'Espagne (1556) ; Paul IV lui donne

tous pouvoirs pour ériger de nouveaux couvents (1559).

Pierre d'Alcantara mourut

au couvent d'Arenas (province d'Avila) le 18 octobre 1562. Mes

fils, dit-il, ne pleurez pas. Le temps est venu pour le Seigneur

d'avoir pitié de moi. Il ne vous oubliera point. Pour moi, je ne suis plus

nécessaire ; au frère qui voulait remonter sa couverture, il dit

: Laisse-moi, mon fils, il y a encore du danger. Si les cèdres du Liban

tremblent, que fera le roseau ? Il se mit à genoux pour recevoir le

viatique ; le lendemain, à quatre heures du matin, il reçut l'extrême-onction,

embrassa et bénit tous ses frères, puis, immobile, se recueillit longuement

; Ne voyez-vous point, mes frères, la Très Sainte Trinité, avec la sainte

Vierge et le glorieux évangéliste ? Il expira doucement en murmurant des

psaumes. Il fut inhumé près de l'autel de l'église des franciscains d'Arénas.

Pierre d'Alcantara, calme

et prudent, pauvre et généreux, obéissant et humble, pénitent et accueillant,

disponible et magnanime fut un des grands orateurs sacrés du Siècle d'Or

espagnol.

Grégoire XV qui

l'appelait docteur et maître éclairé en théologie mystique, béatifia

Pierre d'Alcantara par la bulle In sede Principis

Apostolorum (18 avril 1622) ; le décret de canonisation fut rendu

sous Clément IX (28 avril 1669) et Clément X donna la bulle de canonisation le

11 mai 1670 (Romanorum gesta pontificum) et Clément X étendit sa fête à

l'Église universelle en 1670.

Pierre D'Alcantara vu par Ste Thérèse

Et quel bon modèle de

vertu Dieu vient de nous enlever en la personne du béni Frère Pierre

d'Alcantara ! Le monde aujourd'hui n'est plus capable d'une telle perfection.

On dit que les santés sont plus faibles et que nous ne sommes plus au temps

passé. Ce saint homme était de notre temps, mais sa ferveur était robuste comme

celle d'autrefois : aussi tenait-il le monde sous ses pieds. Sans aller

déchaussé comme lui, sans pratiquer une pénitence aussi âpre, il y a bien des

moyens de fouler le monde aux pieds, et le Seigneur nous les enseigne, quand il

voit qu'on a du coeur. Mais quel courage Sa Majesté a donné à ce saint pour

faire quarante-sept ans si âpre pénitence, comme chacun sait ! Je veux en dire

quelque chose : c’est la pure vérité, je le sais. Il me l’a dit à moi et à une

autre personne dont il se gardait peu ... Pendant quarante ans, je crois,

m’a-t-il dit, il avait dormi seulement une heure et demie par jour. Le plus

dur, dans les débuts, avait été de vaincre le sommeil ; pour cela, il était

toujours à genoux ou debout. Le temps qu’il dormait, il était assis, et la tête

appuyée sur un morceau de bois fixé au mur. Se coucher, s’il l’avait voulu, il

n’eût pu le faire, car sa cellule, comme on sait, n’avait que quatre pieds et

demi de long. Pendant toutes ces années, jamais il ne mit le capuchon, en dépit

du soleil ou de la pluie ; il n’avait rien sur les pieds ; comme vêtement, un

habit de bure, sans rien d’autre sur la chair, et aussi étroit que possible ;

et un petit manteau de même étoffe. Il me conta que pendant les grands froids

il le quittait, laissait ouvertes la porte et la petite fenêtre de la cellule ;

puis il mettait le manteau et fermait la porte, pour contenter le corps et

l’apaiser par un meilleur abri. Manger tous les trois jours était très

ordinaire. Il me dit qu’il n’y avait là rien d’étonnant : c’était très possible

à qui s’accoutumait à cela. Un sien compagnon me dit qu’il lui arrivait de

rester huit jours sans manger. Ce devait être lorsqu’il se tenait en oraison,

car il avait de grands ravissements et transports d’amour de Dieu. De quoi une

fois je fus témoin.

Sainte Thérèse d'Avila

Et quel bon modèle de

vertu Dieu vient de nous enlever en la personne du béni Frère Pierre

d'Alcantara ! Le monde aujourd'hui n'est plus capable d'une telle perfection.

On dit que les santés sont plus faibles et que nous ne sommes plus au temps

passé. Ce saint homme était de notre temps, mais sa ferveur était robuste comme

celle d'autrefois : aussi tenait-il le monde sous ses pieds. Sans aller

déchaussé comme lui, sans pratiquer une pénitence aussi âpre, il y a bien des

moyens de fouler le monde aux pieds, et le Seigneur nous les enseigne, quand il

voit qu'on a du coeur.

Sainte Thérèse d'Avila

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/19.php

A. Scacciati, after A.D. Gabbiani, Saint Peter of Alcántara with Saint Teresa, angels and other figures, 1758, Colour etching, LXXXXVII nella Galeria Palatina

SAINT PIERRE D'ALCANTARA,

CONFESSEUR.

« Bienheureuse pénitence,

qui m'a mérité une telle gloire ! » C'était la parole du Saint de ce jour, en

abordant les cieux ; tandis que Thérèse de Jésus s'écriait sur la terre : « Ah

! quel parfait imitateur de Jésus-Christ Dieu vient de nous ravir, en appelant

à la gloire ce religieux béni, Frère Pierre d'Alcantara ! Le monde, dit-on,

n'est plus capable d'une perfection si haute ; les santés sont plus faibles, et

nous ne sommes plus aux temps passés. Ce saint était de ce temps, sa mâle

ferveur égalait néanmoins celle des siècles passés, et il avait en souverain

mépris toutes les choses de la terre. Mais sans aller nu-pieds comme lui, sans

faire une aussi âpre pénitence, il est une foule d'actes par lesquels nous

pouvons pratiquer le mépris du monde, et que notre Seigneur nous fait connaître

dès qu'il voit en nous du courage. Qu'il dut être grand celui que reçut de Dieu

le saint dont je parle, pour soutenir pendant quarante-sept ans cette pénitence

si austère que tous connaissent aujourd'hui !

« De toutes ses

mortifications, celle qui lui avait le plus coûté dans les commencements,

c'était de vaincre le sommeil ; dans ce dessein, il se tenait toujours à genoux

ou debout. Le peu de repos qu'il accordait à la nature, il le prenait assis, la

tête appuyée contre un morceau de bois fixé dans le mur; eût-il voulu se

coucher, il ne l'aurait pu, parce que sa cellule n'avait que quatre pieds et

demi de long. Durant le cours de toutes ces années, jamais il ne se couvrit de

son capuce, quelque ardent que fût le soleil, quelque forte que fût la pluie.

Jamais il ne se servit d'aucune chaussure. Il ne portait qu'un habit de grosse

bure, sans autre chose sur la chair ; j'ai appris toutefois qu'il avait porté

pendant vingt années un cilice en lames de fer-blanc, sans jamais le quitter.

Son habit était aussi étroit que possible ; par-dessus il mettait un petit

manteau de même étoffe ; dans les grands froids il le quittait, et laissait

quelque temps ouvertes la porte et la petite fenêtre de sa cellule ; il les

fermait ensuite, il reprenait son mantelet, et c'était là, nous disait-il, sa

manière de se chauffer et de faire sentir à son corps une meilleure

température. Il lui était fort ordinaire de ne manger que de trois en trois

jours ; et comme j'en paraissais surprise, il me dit que c'était très facile à

quiconque en avait pris la coutume. Sa pauvreté était extrême, et sa mortification

telle qu'il m'a avoué qu'en sa jeunesse il avait passé trois ans dans une

maison de son Ordre sans connaître aucun des Religieux, si ce n'est au son de

la voix, parce qu'il ne levait jamais les yeux, de sorte qu'il n'aurait pu se

rendre aux endroits où l'appelait la règle, s'il n'avait suivi les autres. Il

gardait cette même modestie par les chemins. Quand je vins aie connaître, son

corps était tellement exténué, qu'il semblait n'être formé que de racines

d'arbres (Ste Thérèse, Vie, ch. XXVII, XXX, traduction Bouix). »

Au portrait du

réformateur franciscain par la réformatrice du Carmel, l'Eglise ajoutera

l'histoire de sa vie On sait que trois familles illustres et méritantes

composent aujourd'hui le premier Ordre de saint François ; le peuple chrétien les

connaît sous le nom de Conventuels, Observantins et Capucins. Une pieuse

émulation de réforme toujours plus étroite avait amené, dans l'Observance même,

la distinction des Observants proprement ou primitivement dits, des Réformés,

des Déchaussés ou Alcantarins, et des Récollets ; d'ordre plus historique que

constitutionnel, si l'on peut ainsi parler, cette distinction n'existe plus

depuis que, le 4 octobre 1897, en la fête du patriarche d'Assise, le Souverain

Pontife Léon XIII a cru l'heure venue de ramener à l'unité la grande famille de

l'Observance, sous le seul nom d'Ordre des Frères Mineurs qu'elle devra porter

désormais (Constit apost. Felicitate quadam).

Pierre naquit à

Alcantara, en Espagne, de nobles parents. Il fit présager dès ses plus tendres

années sa sainteté future. Entré à seize ans dans l'Ordre des Mineurs, il s'y

montra un modèle de toutes les vertus. Chargé par l'obéissance de l'office de

prédicateur, innombrables furent les pécheurs qu'il amena à sincère pénitence.

Mais son désir était de ramener la vie franciscaine à la rigueur primitive ;

soutenu donc par Dieu et l'autorité apostolique, il fonda heureusement le très

étroit et très pauvre couvent du Pedroso, premier de la très stricte observance

qui se répandit merveilleusement par la suite dans les diverses provinces de

l'Espagne et jusqu'aux Indes. Sainte Thérèse, dont il avait approuvé l'esprit,

fut aidée par lui dans son œuvre de la réforme du Carmel. Elle avait appris de

Dieu que toute demande faite au nom de Pierre était sûre d'être aussitôt

exaucée; aussi prit-elle la coutume de se recommander à ses prières, et de

l'appeler Saint de son vivant.

Les princes le

consultaient comme un oracle ; mais sa grande humilité lui faisait décliner

leurs hommages, et il refusa d'être le confesseur de l'empereur Charles-Quint.

Rigide observateur de la pauvreté, il ne portait qu'une tunique, et la plus

mauvaise qui se pût trouver. Tel était son délicat amour de la pureté, qu'il ne

souffrit pas même d'être touché légèrement dans sa dernière maladie par le

Frère qui le servait. Convenu avec son corps de ne lui accorder aucun repos

dans cette vie, il l'avait réduit en servitude, n'ayant pour lui que veilles,

jeûnes, flagellations, froid, nudité, duretés de toutes sortes. L'amour de Dieu

et du prochain qui remplissait son cœur, y allumait parfois un tel incendie,

qu'on le voyait contraint de s'élancer de sa pauvre cellule en plein air, pour

tempérer ainsi les ardeurs qui le consumaient.

Son don de contemplation

était admirable; l'esprit sans cesse rassasié du céleste aliment, il lui

arrivait de passer plusieurs jours sans boire ni manger. Souvent élevé

au-dessus du sol,il rayonnait de merveilleuses splendeurs. Il passa à pied sec

des fleuves impétueux. Dans une disette extrême, il nourrit ses Frères d'aliments

procurés par le ciel. Enfonçant son bâton en terre, il en fit soudain un

figuier verdoyant. Une nuit que, voyageant sous une neige épaisse, il était

entré dans une masure où le toit n'existait plus, la neige, suspendue en l'air,

fit l'office de toit pour éviter qu'il n'en fût étouffé. Sainte Thérèse rend

témoignage au don de prophétie et de discernement des esprits qui brillait en

lui. Enfin, dans sa soixante-troisième année, à l'heure qu'il avait prédite, il

passa au Seigneur, conforté par une vision merveilleuse et la présence des

Saints. Sainte Thérèse, qui était loin de là, le vit au même moment porté au

ciel; et, dans une apparition qui suivit, elle l'entendit lui dire: O heureuse

pénitence, qui m'a valu si grande gloire! Beaucoup de miracles suivirent sa

mort, et Clément IX le mit au nombre des Saints.

« Le voilà donc le terme

de cette vie si austère, une éternité de gloire (Ste Thérèse, Vie, XXVII.) ! »

Combien furent suaves ces derniers mots de vos lèvres expirantes : Je me suis

réjoui de ce qui m'a été dit: Nous irons-dans la maison du Seigneur (Psalm.

CXXI, 1). L'heure de la rétribution n'était pas venue pour ce corps auquel vous

étiez convenu de ne donner nulle trêve en cette vie, lui réservant l'autre ;

mais déjà la lumière et les parfums d'outre-tombe, dont l'âme en le quittant le

laissait investi, signifiaient à tous que le contrat, fidèlement tenu dans sa

première partie, le serait aussi dans la seconde. Tandis que, vouée pour de

fausses délices à d'effroyables tourments, la chair du pécheur rugira sans fin

contre l'âme qui l'aura perdue ; vos membres, entrés dans la félicité de l'âme

bienheureuse et complétant sa gloire de leur splendeur, rediront dans les

siècles éternels à quel point votre apparente dureté d'un moment fut pour eux

sagesse et amour.

Et faut-il donc attendre

la résurrection pour reconnaître que, dès ce monde, la part de votre choix fut

sans conteste la meilleure ? Qui oserait comparer, non seulement les plaisirs

illicites, mais les jouissances permises de la terre, aux délices saintes que

la divine contemplation tient en réserve dès ce monde pour quiconque se met en

mesure de les goûter ? Si elles demeurent au prix de la mortification de la

chair, c'est qu'en ce monde la chair et l'esprit sont en lutte pour l'empire (Gal.

V, 17) ; mais la lutte a ses attraits pour une âme généreuse, et la chair même,

honorée par elle, échappe aussi par elle à mille dangers.

Vous qu'on ne saurait

invoquer en vain, selon la parole du Seigneur, si vous daignez vous-même lui

présenter nos prières, obtenez-nous ce rassasiement du ciel qui dégoûte des

mets d'ici-bas. C'est la demande qu'en votre nom nous adressons, avec l'Eglise,

au Dieu qui rendit admirable votre pénitence et sublime votre contemplation

(Collecte de la fête). La grande famille des Frères Mineurs garde chèrement le

trésor de vos exemples et de vos enseignements ; pour l'honneur de votre Père

saint François et le bien de l'Eglise, maintenez-la dans l'amour de ses

austères traditions. Continuez au Carmel de Thérèse de Jésus votre protection

précieuse ; étendez-la, dans les épreuves du temps présent, sur tout l'état

religieux. Puissiez-vous enfin ramener l'Espagne, votre patrie, à ces glorieux

sommets d'où jadis la sainteté coulait par elle à flots pressés sur le monde ;

c'est la condition des peuples ennoblis par une vocation plus élevée, qu'ils ne

peuvent déchoir sans s'exposer à descendre au-dessous du niveau même où se

maintiennent les nations moins favorisées du Très-Haut.

Dom Guéranger. L'Année liturgique

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/gueranger/anneliturgique/pentecote/pentecote05/053.htm

Giovanni Battista Pittoni (1687–1767),

The Apotheosis of Saint Jérome (Sofronio

Eusebio Girolamo) with Saint Pietro d'Alcántara and an Unidentified

Franciscan, circa 1725, 275 x 143, National Gallery of Scotland, Edimburgo. Purchased 1960 - https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5285/apotheosis-saint-jerome-saint-peter-alcántara-and-unidentified-franciscan

Saint Pierre d’Alcantara (1499

- 1562)

LEÇON DU BRÉVIAIRE ROMAIN

Pierre naquit à Alcantara en Espagne, de parents nobles. A l'âge de seize ans, étant entré dans l'Ordre des Frères Mineurs, il s'y montra un modèle de toutes les vertus, spécialement de pauvreté et de chasteté, et, par la prédication de la parole de Dieu, il ramena du vice a la pénitence d'innombrables auditeurs. Désireux de rétablir l'Institut de Saint-François en sa primitive observance, il construisit près de Pedrosa un couvent très étroit et très pauvre, et y établit avec succès un genre de vie très austère qui se propagea ensuite merveilleusement. Il fut, dans l'œuvre de la réforme, du Carmel, le soutien de sainte Thérèse, dont il avait approuvé l'esprit et qui souvent lui donna de son vivant le nom de saint. Remarquable par la grâce de la contemplation et des miracles, il fut au témoignage de la même sainte Thérèse, gratifié du don de prophétie et de discernement des esprits. Enfin, âgé de soixante-trois ans, il s'en alla au ciel. La bienheureuse Thérèse l'aperçut, dans une vision, rayonnant d'une gloire admirable.

SOURCE : http://www.icrsp.org/Calendriers/Le%20Saint%20du%20Jour/Pierre-d-alcantara.htm

Giovanni Battista Lucini (1639–1686),

Miracle of St Peter of Alcantara, 1680, 184 x 245, Museo civico di Crema e del

Cremasco

Lucini,

Giovanni Battista (1639/ 1686), Miracolo di San Pietro d'Alcantara, 1680,

184 x 245, Crema (CR), Museo

Civico di Crema e del Cremasco

19/10 St Pierre d’Alcantara, confesseur

Né en 1499, mort le 18

octobre 1562. Canonisé en 1669, fête en 1670.

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon. Pierre, né de parents nobles, à Alcantara en Espagne, donna,

dès ses plus tendres années, des signes de sa sainteté future. Étant entré à

seize ans dans l’Ordre des Frères Mineurs, il s’y montra un modèle de toutes

les vertus. Ayant eu alors à exercer par obéissance le ministère de la

prédication, il amena un nombre incalculable de Chrétiens des désordres du vice

à une véritable pénitence. Désirant rétablir dans toute son exactitude

l’observance primitive de l’institut franciscain, confiant dans le secours du

ciel et appuyé de l’autorité apostolique, il fonda, près de Pédrosa, un couvent

très étroit et très pauvre, où il commença pieusement un genre de vie fort

austère, qui s’est merveilleusement répandu dans diverses provinces de l’Espagne

et jusqu’aux Indes. Il aida sainte Thérèse, dont il avait éprouvé l’esprit, à

établir la réforme des Carmélites. Cette Sainte ayant appris de Dieu qu’elle ne

lui demanderait rien au nom de Pierre sans être exaucée sur-le-champ, avait

coutume de se recommander à ses prières et de lui donner le nom de Saint,

quoiqu’il vécût encore.

Cinquième leçon. Il se

dérobait avec la plus grande humilité aux faveurs des princes qui le

consultaient comme un oracle, et il refusa d’être le confesseur de l’empereur

Charles-Quint. Très rigide observateur de la pauvreté, il se contentait d’une

seule tunique, la plus mauvaise de toutes. Il était si délicat pour tout ce qui

concerne la pureté, qu’il ne permit pas au frère qui le servait dans sa

dernière maladie de le toucher tant soit peu. Il réduisit son corps en

servitude par une continuité de veilles, de jeûnes, de flagellations ; par le

froid, la nudité, par toutes sortes de rigueurs, ayant fait pacte avec lui de

ne lui donner aucun repos en ce monde. L’amour de Dieu et du prochain qui

remplissait son cœur, y excitait parfois une flamme si vive, qu’il était obligé

de sortir brusquement de son étroite cellule pour aller, en pleine campagne,

tempérer par la fraîcheur de l’air, l’ardeur qui le brûlait.

Sixième leçon. Il fut élevé

à un degré de contemplation si admirable que, comme son esprit en était

continuellement nourri, il lui arriva parfois de passer plusieurs jours sans

prendre ni nourriture ni boisson. Fréquemment élevé en l’air, on l’a vu briller

d’un éclat admirable. Il passa des fleuves rapides à pied sec. Dans une disette

extrême, il nourrit ses frères d’un aliment venu du ciel. Un bâton qu’il avait

fixé en terre devint bientôt un figuier verdoyant. Une nuit qu’il cheminait, la

neige tombant épaisse, il entra dans une maison en ruines toute découverte, et

la neige, restant suspendue en l’air, lui servit de toit pour qu’il ne fût pas

étouffé par son abondance. Sainte Thérèse atteste qu’il était doué du don de

prophétie et de discernement des esprits. Enfin, étant dans sa

soixante-troisième année, il s’en alla vers le Seigneur, à l’heure qu’il avait

prédite, ayant été fortifié par une merveilleuse vision et par la présence de

plusieurs Bienheureux. A ce moment-là même, sainte Thérèse qui se trouvait dans

un lieu fort éloigné, le vit porté au ciel. Lui ayant apparu -ensuite, il lui

dit : O bienheureuse pénitence, qui m’a valu une si grande gloire ! Beaucoup de

miracles l’ont illustré après sa mort et Clément IX l’a inscrit au nombre des

Saints.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/19-10-St-Pierre-d-Alcantara

Pedro

de Moya (1610–1674), Ex-voto to Saint Peter of Alcantara, circa 1655, 240

x 186.5, Musée Goya, Castres.

Dépôt du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours en 1950

Also

known as

Juan de Garavito y Vilela

de Sanabria

Profile

Son of Peter

Garavita, governor of

the palace; his mother was

a member of the noble family of Sanabia. Peter studied grammar

and philosophy at

Alcantara, and both civil and canon law at Salamanca University. Franciscan at

age 16 at Manjarez. Founded the friary at Babajoz at age 20, and served as its

superior. Ordained in 1524 at

age 25. Noted preacher.

A recluse by nature, he lived at the convent of Saint Onophrius,

a remote location where he could study and pray between

missions. Franciscan provincial

for Saint Gabriel

in Estremadura, Spain in 1538.

Worked in Lisbon, Portugal in 1541 to

help reform the Order.

In 1555 he

started the Alcantarine reforms, now known as the Strictest

Observance. Commissioner of his Order in Spain in 1556.

Provincial of his reformed Order in 1561.

Friend and confessor of Saint Teresa

of Avila, and assisted her in 1559 during

her work to reform her own Order. Mystic and writer whose

works were used by Saint Francis

de Sales.

Born

1499 at

Alcantara, Estremadura, Spain

18

October 1562 at Estremadura, Spain of

natural causes

18 April 1622 by Pope Gregory

XV

28 April 1669 by Pope Clement

IX

Brazil (named

by Pope Blessed Pius

IX in 1862)

Estremadura Spain (named

in 1962)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

and Saintly Dominicans, by Blessed Hyacinthe-Marie

Cormier, O.P.

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, by Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

images

audio

video

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Readings

He does much in the sight

of God who does his best, be it ever so little. – Saint Peter

of Alcantara

No tongue can express the

greatness of the love which Jesus Christ bears to our souls. He did not wish

that between Him and His servants there should be any other pledge than

himself, to keep alive the remembrance of Him. – Saint Peter

of Alcantara

MLA

Citation

“Saint Peter of

Alcántara“. CatholicSaints.Info. 21 April 2024. Web. 4 December 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-of-alcantara/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-of-alcantara/

San Francesco della Vigna in Venice - right

transept - Chapel Giustinian dei Vescovi - The vault is

decorated with stucco from the 18th century, with a central medallion Saint

Peter of Alcantara in Glory (1765) by Francesco Fontebasso.

Eglise San Francesco della Vigna à

Venise - partie droite du transept - Chapelle Giustinian dei

Vescovi- La voûte est décorée de stuc du XVIIIe siècle, avec un médaillon

centrale Saint-Pierre d'Alcantara en Gloire (1765) par Francesco

Fontebasso.

Interno

della Chiesa di San Francesco della

Vigna a Venezia - transetto destro. Cappella Giustinian dei Vescovi - La

volta è decorata con stucchi del XVIII secolo, con un medaglione centrale San

Pietro d'Alcantara in Gloria (1765) di Francesco Fontebasso.

Book of Saints –

Peter of Alcantara

Article

(Saint)

(October

19) (16th

century) One of the famous Spanish Mystics

(Saint Teresa, Saint John

of the Cross, Blessed John

of Avila, etc.) who are the glory of the age of the disastrous Protestant

rebellion against the Church in

the North of Europe. Saint Peter

was a Franciscan and

originated one of the strictest Reforms of his Order. His short Treatise

on Prayer was much valued by Saint Francis

of Sales and other Masters of the Interior Life; but Saint Peter

is perhaps chiefly celebrated for the incredible austerities he practised, and

for his marvellous gift of supernatural communion with God.

He is also gratefully to be remembered for the encouragement he gave to Saint Teresa.

He died A.D. 1562 at

the age of sixty-three.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate. “Peter

of Alcantara”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

15 October 2016. Web. 5 December 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-peter-of-alcantara/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-peter-of-alcantara/

Estatua

de San Pedro de Alcantara, Arenas de San Pedro

Peter of Alcántara, OFM

(RM)

Born at Alcántara, Estremadura, Spain, in 1499; died at Arenas, 1562; canonized

in 1669.

Sixteenth century Spain

provided the Church with a wealth of heroes--most of whom seemed to know one

another. I hope you enjoy this story of a man who truly fell in love with God

at an early age.

Peter Garavito's father,

who was a lawyer and governor of the province, died in 1513 and two years

later, after studying law in Salamanca, 16-year-old Peter entered the Observant

Franciscans at Manxarretes (Manjaretes). At 22 he was sent to Badajoz to found

a friary.

He was ordained at the

age of 25 (1524), and preached missions in Spain and Portugal. After serving as

superior at Robredillo, Plasencia, and Estremadura, Peter finally had his

request for solitude granted with an appointment to the friary at Lapa, though

he was also named its superior. For a time he served as chaplain to the court

of King John III of Portugal. This period of his life is uneventful, but all

the time he was longing for a yet more rigorous following of the Franciscan

rule.

After he was elected

provincial for Saint Gabriel at Estremadura in 1538, he was able to take

definite steps to begin the reform, but his efforts were not well received

during the provincial chapter at Placensia in 1540. So, he resigned as minister

provincial. For two years (1542-44) he lived as a hermit with Friar Martin of

Saint Mary on Arabida Mountain near Lisbon and was named superior of Palhaes

community for novices when numerous friars were attracted to their way of life.

During that period he had become convinced of the need for a vigorous Catholic

reform, a Counter-Reformation with which to oppose the Protestant Reformation.

Unable to secure approval

for a stricter congregation of friars from his provincial, his idea was

accepted by the bishop of Coria. Finally, with the approval of Pope Julius III,

c. 1556, he founded the Reformed Friars Minor of Spain, usually called the

Alcatarine Franciscans, which established not only monasteries but also Houses

of Retreat where anyone could go and try to live according to the Rule of Saint

Francis. The friars lived in small groups, in great poverty and austerity,

going barefoot, abstaining from meat and wine, spending much time in solitude

and contemplation.

Three years later, in

1559, the new order was enlarged with the addition of a new province, that of

Saint Joseph. But the Reformed Franciscans failed to win the support of the

other Franciscans; Conventuals and Observants, both jealous of their

privileges, continued to quarrel over the inheritance of Saint Francis.

At the time of his death

in 1562, Saint Peter was still uncertain of the future of his work, which had

been placed under the Conventuals. But the example which he set was followed by

Saint Teresa of Ávila and there was thus born Saint Joseph of Ávila, the first

Reformed Carmel in Spain. Even if Peter's work was surpassed by that of Saint

Teresa, it was instrumental in releasing in Spain, and then throughout Europe,

a movement of vigorous revival which gave strength to the Church at a time when

it was sorely needed.

Teresa and Peter were

intimate friends for the last four years of her life. After they met in 1560,

he became her confessor, advisor, and admirer. His ferocious and almost

unbelievable asceticism is not myth, but rather described by Teresa in a

celebrated chapter of her autobiography. She wrote with awe that his penances

were "incomprehensible to the human mind." They had reduced him, she

tells us, to a condition in which he looked as if "he had been made of the

roots of trees."

He practiced asceticism

from the age of 16 until his death, opposing a will of iron against the

doubtlessly acute temptations of his body. He slept for no more than two hours

each night, and even then he did not lie down, but slept either in a hard wooden

chair or kneeling against the wall. His cell was no more than 4- ½ feet long.

He ate extremely little, at first going for three days, and then for a week

without food. When he did eat, he destroyed the taste of the food by sprinkling

it with ashes or earth. He never drank wine.

He never wore shoes, or

even sandals, and went about barefoot. He never wore a hat or a hood, and

exposed his head to the icy rains of winter or the scorching sun of summer. He

wore a hair shirt, and though he possessed a cloak, he never wore it in cold

weather. He went everywhere on foot, or at the most would ride on a donkey.

Consumed with fever, he

refused a glass of water, saying "Jesus was ready to die of thirst on the

cross." For three years he never raised his eyes from the ground. And yet,

"With all his holiness," wrote Saint Teresa of Ávila, "he was

very kindly, though spare of speech except when asked a question, and then he

was delightful, for he had a keen understanding."

Such asceticism may seem

self-centered and excessive to us today. Some may think that there are

sufficient mortifications in the normal course of life without adding to them.

But asceticism has been in the Church since the days of the Desert Fathers, and

though the practices of the ascetics might seem horrible, unnecessary, or even

ridiculous to us, the Church has never reproved them; indeed, they are to be

recommended for the active as well as for the contemplative. And who is to say

that the present unhappy state of the world would not be greatly changed for

the better if people did follow ascetic practices?

Peter's asceticism,

however, is only one aspect of his life of great holiness and incessant labor

devoted to the restoration in Spain of the primitive Franciscan rule.

Saint Peter was one of the

great Spanish mystics and his Treatise on Prayer and Meditation (1926 English

translation) was said by Pope Gregory XV to be "a shining light to lead

souls to heaven and a doctrine prompted by the Holy Spirit." This treatise

was used later by Saint Francis de Sales. His mystical works, intended purely

for edification, follow traditional lines.

"He had already

appeared to me twice since his death," wrote Teresa of Ávila, "and I

witnessed the greatness of his glory. Far from causing me the least fear, the

sight of him filled me with joy. He always showed himself to me in the state of

a body which was glorious and radiant with happiness; and I, seeing him, was

filled with the same happiness. I remember that when he first appeared to me he

said, to show me the extent of his felicity, 'Blessed be the penitence which

has brought me such a reward'" (Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney,

Encyclopedia, Underhill).

In art he is depicted as

a Franciscan in radiance levitated before the Cross, angels carry a girdle of nails,

chain, and discipline. Sometimes he is shown (1) walking on water with a

companion, a star over his head; (2) praying before a crucifix, discipline

(scourge), and hairshirt; or (3) with a dove at his ear, cross and discipline

in the picture. He is venerated at Alcántara and Pedrosa (Roeder).

In 1862, he was declared

the patron of Brazil (Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1019.shtml

Anton Schmidt (1706–1773), Svätý Peter z Alcantary, prima del 1763, 245 x 161, Galleria nazionale slovacca, Bratislava.

St. Peter of Alcantara

Feastday: October 18

Birth: 1499

Death: 1562

Saint Peter of Alcantara

was born in Alcantara, Spain in 1499. His father was the Governor of the

province and his mother came from a noble family. He was privately tutored and

attended the University of Salamanca. After he returned home from university,

he joined the Franciscans.

Peter was accepted as a

Franciscan Friar of the Stricter Observance in the Friary at Manxaretes

Extramadura in 1515.

At the young age of 22,

he was sent to found a community of the Stricter Observance at Badajoz.

He was ordained as a

priest in 1524 and in 1525 he became Guardian of the friary of St. Mary of the

Angels at Robredillo, Old Castile.

He later entered the

Order of the reform of the Discalced Friars. By 1538, he was elected the

Superior of St. Gabriel province. As the superior, he drew up new constitutions

for the order of Stricter Observance, however these were met with resistance.

Eventually he resigned from this post.

Peter then began a new

life, one of less formal responsibility but one of greater spiritual

responsibility. He took up his spiritual cross and preached with great success

to the poor. Peter preferred preaching to this group more than any other and he

frequently drew inspiration from the Old Testament books. His sermons often

concentrated on the topic of on compassion.

When Peter was not

preaching, he would spend long periods of time in solitude. From 1553 to early

1555, he spent this time alone in meditation and prayer. Following these two

years of solitude, Peter made a pilgrimage to Rome, barefoot the entire way. While

in Rome he obtained permission from Pope Julius III to establish friaries,

departing on his new mission just before the Holy Father’s death.

Along his way home, Peter

established several friaries. These friaries were compelled to follow a strict

constitution, mush like the ones he endeavored to impose in St. Gabriel

province.

This time, his new

constitution contained reforms that proved fruitful and were later adopted

across Spain.

Peter was known for

frequently experiencing ecstasy, a state where he was entirely consumed with

the warmth and light of the Holy Spirit. These euphoric moments were common

during his prayer and meditation. Some claim to have witness him levitate.

When he was close to

death, Peter took to his knees and prayed. When he was offered water he refused

it saying, "Even my Lord Jesus Christ thirsted on the Cross." Peter

died in prayer on October 18, 1562.

Following his death,

Peter was beautified by Pope Gregory XV on April 18, 1622. He was subsequently

canonized by Pope Clement IX on April 28, 1669.

St. Peter of Alcantara is

the patron saint of the Nocturnal Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=777

Statue

of Saint Peter of Alcantara in Saint Peter's Basilica

Hornacina de San Pedro de Alcántara (1713) en la nave central de la Basílica de San Pedro, Ciudad del Vaticano.

PETER OF ALCÁNTARA, ST.

Friar Minor, ascetic,

mystic, Franciscan reformer; b. Peter Garavita, in Alcántara, Estremadura,

Spain, 1499;d. Arenas, Spain, Oct. 18, 1562. Peter, of noble parentage, entered

the Franciscan order in the discalced vice province of Estremadura in 1515.

Although not its founder, Peter is closely linked with the discalced reform, a

controversial movement within Spanish Franciscanism. Because of his adherence

to it, the movement spread from Spain to Portugal, Italy, Mexico, the East

Indies, the Philippines, and Brazil, and his followers became known as

Alcantarines. By his followers he was hailed as the restorer of the Franciscan

Order and, as such, his statue was placed among the other founders of religious

orders in the Vatican basilica. Peter is known for the severity of his

mortifications, some of which are related in the autobiography of St. teresa of

Jesus, whom, in his last years, he advised and encouraged in her Carmelite

reform. He wrote little. His justly famous Tratado de la oración y

meditación was already popular in his lifetime, although its authenticity

has not escaped challenge. It has gone through more than 175 editions and

numerous translations. Peter died at Arenas, where his remains are still

venerated in the shrine built at royal expense. He was beatified in 1622 and

canonized in 1669. In 1826, by decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, he

was made the patron saint of Brazil; in 1962 he was declared copatron of

Estremadura.

Feast: Oct. 19.

Bibliography: "Estudios

sobre San Pedro de Alcántara," Archivo Ibero-Americano 22

(Madrid 1962). Peter of Alcantara, Treatise on Prayer and

Meditation, tr. D. dDvas (London 1926; repr. Westminster, Md. 1949). E. A. Peers, Studies of the Spanish Mystics, v. 2 (London 1930). Peter of Alcantara, Vida y Escritores de San Pedro de Alcantaro, ed. R. Sanz-Valdivieso (Madrid 1996). Conferencia de ministros provincales, ofm., Misticos

Franciscanos Espanoles (Madrid 1996), bibliography.

[J. B. Wuest]

New Catholic Encyclopedia

SOURCE : https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/peter-alcantara-st

São

Pedro de Alcântara, XIX sec, 140 x 103, Museo nazionale delle

belle arti, Rio de Janeiro.

St. Peter of Alcántara

Born

at Alcántara, Spain,

1499; died 18 Oct., 1562. His father, Peter Garavita, was the governor of the

place, and his mother was of the noble family of

Sanabia. After a course of grammar and philosophy in his native town,

he was sent, at the age of fourteen, to the University

of Salamanca. Returning home, he became a Franciscan in

the convent of

the Stricter Observance at Manxaretes in 1515. At the age of twenty-two

he was sent to found a new community of

the Stricter Observance at Badajoz.

He was ordained priest in

1524, and the following year made guardian of the convent of

St. Mary of the Angels at Robredillo. A few years later he began

preaching with much success. He preferred to preach to the poor; and

his sermons,

taken largely from the Prophets and Sapiential Books, breathe

the tenderest human sympathy. The reform of the "Discalced

Friars" had, at the time when Peter entered the order, besides

the convents in Spain,

the Custody of Sta. Maria Pietatis in Portugal,

subject to the General of the Observants.

Having

been elected minister of St. Gabriel's province in

1538, Peter set to work at once. At the chapter of Plasencia in

1540 he drew up the Constitutions of the Stricter Observants, but his

severe ideas met

with such opposition that he renounced the office of provincial and retired

with John

of Avila into the mountains of Arabida, Portugal,

where he joined Father Martin a Santa Maria in his life

of eremitical solitude.

Soon, however, otherfriars came

to join him, and several little communities were

established. Peter being chosen guardian and master

of novices at

the convent of Pallais.

In 1560 these communities were erected into

the Province of Arabida. Returning to Spain in

1553 he spent two more years in solitude, and then journeyed barefoot to Rome,

and obtained permission of Julius

III to found some poor convents in Spain under

the jurisdiction of

the general of theConventuals. Convents were

established at Pedrosa, Plasencia,

and elsewhere; in 1556 they were made acommissariat, with Peter as

superior, and in 1561, a province under the title of St. Joseph.

Not discouraged by the opposition and ill-success his efforts at reform had met

with in St. Gabriel's province, Peter drew up the

constitutions of the new province with even greater severity. The

reform spread rapidly into other provinces of Spain and Portugal.

In 1562

the province of St. Joseph was put under the jurisdiction of

the general of the Observants, and two new custodies were formed: St. John

Baptist's in Valencia,

and St. Simon's in Galicia (see Friars

Minor). Besides the above-named associates of Peter may be

mentioned St.

Francis Borgia, John

of Avila, and Ven.

Louis of Granada. In St.

Teresa, Peter perceived a soul chosen

of God for

a great work, and her success in the reform of Carmelwas in great measure

due to his counsel, encouragement, and defence. (See Carmelites.)

It was a letter from St. Peter (14 April, 1562) that encouraged her

to found her first monastery at Avila,

24 Aug. of that year. St. Teresa's autobiography is the source of

much of our information regarding Peter's life, work, and gifts of miraclesand prophecy.

Perhaps the most

remarkable of Peter's graces were

his gift of contemplation and the virtue of penance.

Hardly less remarkable was his love of God,

which was at times so ardent as to cause him, as it did St.

Philip Neri, sensible pain, and frequently rapt him into ecstasy.

The poverty he practised and enforced was as cheerful as it was real,

and often let the want of even the necessaries of life be felt.

In confirmation of his virtues and mission of

reformation God worked

numerous miracles through

his intercession and by his very presence. He wasbeatified by Gregory

XV in 1622, and canonized by Clement

IX in 1669. Besides the Constitutions of

the StricterObservants and many letters

on spiritual subjects, especially to St. Teresa, he composed a

short treatise on prayer,

which has been translated into all the languages of Europe.

His feast is

19 Oct. (See ST.

PASCAL BAYLON; ST.

PETER BAPTIST; JAPANESE

MARTYRS;

[Note: In

1826, St. Peter of Alcántara was named Patron of Brazil,

and in 1962 (the fourth centenary of his death), of Estremadura. Because of the

reform of the general Roman calendar in 1969, his feast on

19 October is observed only in local and particular liturgical calendars.]

Sources

Lives by JOHN OF SANTA

MARIA, Min. Obs. Ale. Chron. Prov. S. Jos., 1, I; and MARCHESIO (Rome,

1667); PAULO, Vita S. Petri Alc. (Rome, 1669); WADDING, Annales,

an. 1662; LEO, Lives of the Saints and Blessed of the Three Orders of

St. Francis, IV (Taunton, 1888); Acta SS., Oct., VIII, 636 sq.

Reagan,

Nicholas. "St. Peter of Alcántara." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company,1911. 2

Apr. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11770c.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. O Saint

Peter, and all ye holy Priests and Levites, pray for us.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11770c.htm

Saint

Peter of Alcántara, etching

October 19

St. Peter of Alcantara,

Confessor

From his life, written by

F. John of St. Mary, in 1619, and again by F. Martin of St. Joseph, in 1644:

also from the edifying account St. Teresa has left us of him in her own life,

c. 27. F. Wadding’s Annals of the Franciscan Order, and Helyot, Hist. des Ord.

Relig. t. 7, p. 137.

A.D. 1562

CHRIST declares the

spirit and constant practice of penance to be the foundation of a Christian or

spiritual life. This great and most important maxim, which in these latter ages

is little understood, even amongst the generality of those who call themselves

Christians, is set forth by the example of this saint to confound our sloth,

and silence all our vain excuses. St. Peter was born at Alcantara, a small town

in the province of Estramadura in Spain, in 1499. His father, Alphonso

Garavito, was a lawyer and governor of that town; his mother was of good

extraction, and both were persons eminent for their piety and personal merit in

the world. Upon the first dawn of reason, Peter discovered the most happy

dispositions to virtue, and seemed a miracle of his age in fervour and

unwearied constancy in the great duty of prayer from his childhood, and his

very infancy. He had not finished his philosophy in his own country, when his father

died. Some time after this loss he was sent to Salamanca to study the canon

law. During the two years that he spent in that university, he divided his

whole time between the church, the hospital, the school, and his closet. In

1513 he was recalled to Alcantara, where he deliberated with himself about the

choice of a state of life. On one side, the devil represented to him the

fortune and career which were open to him in the world; on the other side,

listening to the suggestions of divine grace, he considered the dangers of such

a course, and the happiness and spiritual advantages of holy retirement. These

sunk deep into his heart, and he felt in his soul a strong call to a religious

state of life, in which he should have no other concern but that of securing

his own salvation. Resolving, therefore, to embrace the holy Order of St.

Francis, in the sixteenth year of his age he took the habit of that austere

rule in the solitary convent of Manjarez, situated in the mountains which run

between Castile and Portugal. An ardent spirit of penance determined his choice

of this rigorous institute in imitation of the Baptist, and he was so much the

more solicitous after his engagement to cultivate and improve the same with

particular care, as he was sensible that the characteristical virtues of each

state ought to form the peculiar spirit of their sanctity who serve God in it.

During his novitiate he

laboured to subdue his domestic enemy by the greatest humiliations, most

rigorous fasts, incredible watchings and other severities. Such was his fervour

that the most painful austerities had nothing frightful or difficult for him;

his disengagement from the world from the very moment he renounced it was so

entire, that he seemed in his heart to be not only dead or insensible but even

crucified to it, and to find all that a pain which flatters the senses and the

vanity of men in it: and the union of his soul with his Creator seemed to

suffer no interruption from any external employments. He had first the care of

the vestry, (which employment was most agreeable to his devotion,) then of the

gate, and afterwards of the cellar; all which offices he discharged with

uncommon exactness, and without prejudice to his recollection. That his eyes

and other senses might be more easily kept under the government of reason, and

that they might not, by superfluous curiosity, break in upon the interior

recollection of his mind, such was the restraint he put upon them, that he had

been a considerable time a religious man without ever knowing that the church

of his convent was vaulted. After having had the care of serving the refectory

for half a year, he was chid by the superior for having never given the friars

any of the fruit in his custody; to which the servant of God humbly answered,

he had never seen any. The truth was, he had never lifted up his eyes to the

ceiling, where the fruit was hanging upon twigs, as is usual in countries where

grapes are dried and preserved. He lived four years in a convent, without

taking notice of a tree that grew near the door. He ate constantly for three

years in the same refectory, without seeing any other part of it than a part of

the table where he sat, and the ground on which he trod. He told St. Teresa

that he once lived in a house three years without knowing any of his religious

brethren but by their voices. From the time that he put on the religious habit

to his death he never looked any woman in the face. These were the marks of a

truly religious man, who studied perfectly to die to himself. His food was for

many years only bread moistened in water, or unsavoury herbs, of which, when he

lived a hermit, he boiled a considerable quantity together, that he might spend

the less time in serving his body, and ate them cold, taking a little at once

for his refection, which for a considerable time he made only once in three

days. Besides these unsavoury herbs, he sometimes allowed himself a porridge

made with salt and vinegar; but this only on great feasts. For some time his

ordinary mess was a soup made of beans; his drink was a small quantity of

water. He seemed by long habits of mortification, to have almost lost the sense

of taste in what he ate; for when a little vinegar and salt was thrown into a

porringer of warm water, he took it for his usual soup of beans. He had no

other bed than a rough skin laid on the floor, on which he knelt great part of

the night, leaning sometimes on his heels for a little rest; but he slept

sitting, leaning his head against a wall. His watchings were the most difficult

and the most incredible of all the austerities which he practised; to which he

inured himself gradually, that they might not be prejudicial to his health; and

which, being of a robust constitution of body, he found himself able to bear.

He was assailed by violent temptations and cruel spiritual enemies; but, by the

succour of divine grace, and the arms of humility and prayer, was always

victorious.

A few months after his

profession, Peter was sent from Manjarez to a remote retired convent near

Belviso, where he built himself a cell with mud and the branches of trees, at

some distance from the rest, in which he practised extraordinary mortifications

without being seen. About three years after, he was sent by his provincial to

Badajos, the metropolis of Estramadura, to be superior of a

small friary lately established there, though he was at that time but twenty

years old. The three years of his guardianship or wardenship appeared to him a

grievous slavery. When they were elapsed, he received his provincial’s command

to prepare himself for holy orders. Though he earnestly begged for a longer

delay, he was obliged to acquiesce, and was promoted to the priesthood in 1524,

and soon after employed in preaching. The ensuing year he was made guardian of

Placentia. In all stations of superiority he considered himself as a servant to

his whole community, and looked upon his post only as a strict obligation of

encouraging the rest in the practice of penance by his own example. Our saint,

who had never known the yoke of the world or vicious habits, entered upon his

penitential course in a state of innocence and purity which seemed never to

have been stained with the guilt of mortal sin. But by the maxims of the

gospel, and the spirit of God, which directs all the saints, a deep sense was

impressed upon his soul of the obligation which every Christian lies under of

making his whole life a martyrdom of penance, to satisfy the divine justice

both for past and daily infidelities, to prevent the rebellion of the senses

and passions, and to overcome the opposition which the flesh and self-will

raise against the spirit, unless they are entirely subdued, and made obedient

to it. Neither can God perfectly reign in a heart, so long as the least spark

of inordinate desires is habitually cherished in it. Every one, therefore, owes

to God a sacrifice of exterior mortification and interior self-denial of his

will, with a constant spirit of compunction, and a rigorous, impartial

self-examination or inspection into the dark recesses of his heart, in order to

discover and extirpate the roots of all rising vicious inclinations. St. Peter,

by his own example, inspired his religious brethren with fervour in all the

branches of holy penance: whilst, by purifying the affections of his heart, he

prepared his soul for the most sublime graces of divine love and heavenly

contemplation. When the term of his second guardianship was expired, he was

employed six years in preaching. Penetrated with the most profound sentiments

of humility, compunction, and sovereign contempt of all earthly things, and

burning with the most ardent charity, he appeared in the pulpits like a seraph

sent by God to rouse sinners to a true spirit of penance, and to kindle in

their most frozen breasts the fire of divine love. Hence incredible was the

fruit which his sermons produced. Besides his natural talents and stock of

learning, he was enriched by God with an experimental and infused sublime

knowledge and sense of spiritual things, and of the sacred paths of virtue,

which is never acquired by study, but is the fruit only of divine grace, an

eminent spirit of prayer, rooted habits, and the heroic practice of all

virtues. The saint’s very countenance or presence alone seemed a powerful

sermon, and it was said that he had but to show himself to work conversions,

and excite his audience to sighs and tears.

The love of retirement

being always St. Peter’s predominant inclination, he made it his earnest

petition to his superiors that he might be placed in some remote solitary

convent, where he might give himself up to the sweet commerce of divine

contemplation. In compliance with his request he was sent to the convent of St.

Onuphrius, at Lapa, near Soriana, situated in a frightful solitude; but, at the

same time, he was commanded to take upon him the charge of guardian or warden

of that house. In that retirement, he composed his golden book, On Mental

Prayer, at the request of a pious gentleman, who had often heard him speak on

that subject. This excellent little treatise was justly esteemed a finished

masterpiece on this important subject by St. Teresa, Lewis of Granada, St.

Francis of Sales, Pope Gregory XV., Queen Christina of Sweden, and others. In

it the great advantages and necessity of mental prayer are briefly set forth:

all its parts and its method are explained, and exemplified in affections of

divine love, praise, and thanksgiving, and especially of supplication or

petition. Short meditations on the last things, and on the passion of Christ,

are added as models. Upon the plan of this book, Lewis of Granada and many

others have endeavoured to render the use of mental prayer easy and familiar

among Christians, in an age which owes all its spiritual evils to a supine

neglect of this necessary means of interior true virtue. Our saint has left us

another short treatise, On the Peace of the Soul, or On an Interior Life, no

less excellent than the former. 1 St.

Peter was himself an excellent proficient in the school of divine love, and in

the exercises of heavenly contemplation. His prayer and his union with God was

habitual. He said mass with a devotion that astonished others, and often with

torrents of tears, or with raptures. He was seen to remain in prayer a whole

hour, with his arms stretched out, and his eyes lifted up without moving. His

ecstasies in prayer were frequent, and sometimes of long continuance. So great

was his devotion to the mystery of the incarnation, and the holy sacrament of

the altar, that the very mention or thought of them frequently sufficed to

throw him into a rapture. The excess of heavenly sweetness, and the great

revelations which he received in the frequent extraordinary unions of his soul

with God are not to be expressed. In the jubilation of his soul through the

impetuosity of the divine love he sometimes was not able to contain himself

from singing the divine praises aloud in a wonderful manner. To do this more

freely, he sometimes went into the woods, where the peasants who heard him

sing, took him for one who was beside himself.

The reputation of St.

Peter having reached the ears of John III., king of Portugal, that prince was

desirous to consult him upon certain difficulties of conscience, and St. Peter

received an order from his provincial to repair to him at Lisbon. He did not

make use of the carriages which the king had ordered to be

ready for him, but made the journey barefoot, without sandals, according to his

custom. King John was so well satisfied with his answers and advice, and so

much edified by his saintly comportment, that he engaged him to return again

soon after. In these two visits the saint converted several great lords of the

court; the infanta Maria, the king’s sister, trampling under her feet the pomp

of the world, made privately the three vows of religious persons, but with this

condition, that she should continue at court, and wear a secular dress, her

presence being necessary for the direction of certain affairs. This princess

founded a rigorous nunnery of barefooted Poor Clares at Lisbon, for ladies of

quality, and both she and the king were extremely desirous to detain the saint

at court. But though they had fitted up apartments like a cell, with an oratory

for him, and allowed him liberty to give himself up wholly to divine

contemplation, according to his desire, yet he found the conveniences too

great, and the palace not agreeable to his purposes. A great division having

happened among the townsmen of Alcantara, he took this opportunity to leave the

court, in order to reconcile those that were at variance. His presence and

pathetic discourses easily restored peace among the inhabitants of Alcantara.

This affair was scarcely finished, when, in 1538, he was chosen provincial of

the province of St. Gabriel, or of Estramadura, which, though it was of the

conventuals, had adopted some time before certain constitutions of reform. The

age required for this office being forty years, the saint warmly urged, that he

was only thirty-nine; but all were persuaded that his prudence and virtue were

an overbalance. Whilst he discharged this office he drew up several severe

rules of reformation, which he prevailed on the whole province to accept in a

chapter which he held at Placentia for this purpose, in 1540. Upon the

expiration of the term of his provincialship, in 1541, he returned to Lisbon,

to join F. Martin of St. Mary, who was laying the foundation of a most austere

reformation of this Order reduced to an eremitical life, and was building the

first hermitage upon a cluster of barren mountains called Arâbida, upon the

mouth of the Tagus, on the opposite bank to Lisbon. The Duke of Aveiro not only

gave the ground, but also assisted them in raising cells. St. Peter animated

the fervour of these religious brethren, and suggested many regulations which

were adopted. The hermits of Arâbida wore nothing on their feet, lay on bundles

of vine-twigs, or on the bare ground, never touched flesh or wine, and ate no

fish except on festivals. Peter undertook to awake the rest at midnight, when

they said matins together: after which they continued in prayer till break of

day. Then they recited prime, which was followed by one mass only, according to

the original regulation of St. Francis. After this, retiring to their cells,

they remained there till tierce, which they recited together, with the rest of

the canonical hours. The time between vespers and compline was allotted for

manual labour. Their cells were exceedingly mean and small: St. Peter’s was so

little, that he could neither stand up nor lie down in it without bending the

body. F. John Calus, general of the Order, coming into Portugal, desired to see

St. Peter, and made a visit to this hermitage. Being much edified with what he

saw, he gave F. Martin leave to receive novices, bestowed on this reform the

convents of Palhaes and Santaren, and erected it into a custody; his companion

leaving him to embrace this reformation. The convent of Palhaes being appointed

for the novitiate, St. Peter was nominated guardian, and charged with the

direction of the novices.

Our saint had governed

the novitiate only two years, when, in 1544, he was recalled by his own

superiors into Spain, and received by his brethren in the province of Estramadura

with the greatest joy that can be expressed. Heavenly contemplation being

always his favourite inclination, though by obedience, he often employed

himself in the service of several churches, and in the direction of devout

persons, he procured his superior’s leave to reside in the most solitary

convents, chiefly at St. Onuphrius’s, near Soriano. After four years spent in

this manner, he was allowed, at the request of Prince Lewis, the king’s most

pious brother, and of the Duke of Aveiro, to return to Portugal. During three

years that he staid in that kingdom he raised his congregation of Arâbida to

the most flourishing condition, and, in 1550, founded a new convent near

Lisbon. This custody was erected into a province of the Order, in 1560. His

reputation for sanctity drew so many eyes on him, and gave so much interruption

to his retirement, that he hastened back to Spain, hoping there to hide himself

in some solitude. Upon his arrival at Placentia in 1551, his brethren earnestly

desired to choose him provincial; but the saint turned himself into every shape

to obtain the liberty of living some time to himself, and at length prevailed.

In 1553 he was appointed custos by a general chapter held at Salamanca. In 1554

he formed a design of establishing a reformed congregation of friars upon a

stricter plan than before; for which he procured himself to be empowered by a

brief obtained of Pope Julius III. His project was approved by the provincial

of Estramadura, and by the bishop of Coria, in whose diocess the saint, with

one fervent companion, made an essay of this manner of living in a small

hermitage. A short time after, he went to Rome, and obtained a second brief, by

which he was authorized to build a convent according to this plan. At his

return a friend founded a convent for him, such a one as he desired, near

Pedroso, in the diocess of Palentine, in 1555, which is the date of this

reformed institute of Franciscans, called the Barefooted, or of the strictest

observance of St. Peter of Alcantara. This convent was but thirty-two feet

long, and twenty-eight wide; the cells were exceedingly small, and one half of

each was filled with a bed, consisting of three boards: the saint’s cell was

the smallest and most inconvenient. The church was comprised in the dimensions

given above, and of a piece with the rest. It was impossible for persons to

forget their engagement in a penitential life whilst their habitations seemed

rather to resemble graves than chambers. The Count of Oropeza founded upon his

estates two other convents for the saint; and certain other houses received his

reformation, and others were built by him. In 1561 he formed them into a

province, and drew up certain statutes, in which he orders that each cell

should only be seven feet long, the infirmary thirteen, and the church

twenty-four; the whole circumference of a convent forty or fifty feet; that the

number of friars in a convent should never exceed eight; that they should

always go barefoot, without socks or sandals; should lie on the boards, or mats

laid on the floor; or, if the place was low and damp, on beds raised one foot

from the ground; that none, except in sickness, should ever eat any flesh,

fish, or eggs, or drink wine; that they should employ three hours every day in

mental prayer, and should never receive any retribution for saying mass. The

general appointed St. Peter commissary of his Order in Spain, in 1556, and he

was confirmed in that office by Pope Paul IV., in 1559. In 1561, whilst he was

commissary, he was chosen provincial of his reformed Order, and, going to Rome,

begged a confirmation of this institute. Pius IV., who then sat in St. Peter’s

chair, by a bull dated in February, 1562, exempted this congregation from all

jurisdiction of the conventual Franciscans, (under whom St. Peter had lived,)

and subjected it to the minister-general of the Observantins, with this clause,

that it is to be maintained in the perpetual observance of the rules and

statutes prescribed by St. Peter. It is propagated into several provinces in

Spain, and is spread into Italy, each province in this reform consisting of

about ten religious houses

When the Emperor Charles

V., after resigning his dominions, retired to the monastery of St. Justus, in

Estramadura, of the Order of Hieronymites, in 1555, he made choice of St. Peter

for his confessor, to assist him in his preparation for death; but the saint,

foreseeing that such a situation would be incompatible with the exercises of

assiduous contemplation and penance to which he had devoted himself, declined that

post with so much earnestness, that the emperor was at length obliged to admit

his excuses. The saint, whilst in quality of commissary he made the visitation

of several monasteries of his Order, arrived at Avila in 1559. St. Teresa

laboured at that time under the most severe persecutions from her friends and

her very confessors, and under interior trials from scruples and anxiety,

fearing at certain intervals, as many told her, that she might be deluded by an

evil spirit. A certain pious widow lady, named Guiomera d’Ulloa, an intimate

friend of St. Teresa, and privy to her troubles and afflictions, got leave of

the provincial of the Carmelites that she might pass eight days in her house,

and contrived that this great servant of God should there treat with her at

leisure. St. Peter, from his own experience and knowledge in heavenly

communications and raptures, easily understood her, cleared all her

perplexities, gave her the strongest assurances that her visions and prayer

were from God, loudly confuted her calumniators, and spoke to her confessor in

her favour. 2 He

afterwards exceedingly encouraged her in establishing her reformation of the

Carmelite Order, and especially in founding it in the strictest poverty. 3 Out

of his great affection and compassion for her under her sufferings, he told her

in confidence many things concerning the rigorous course of penance in which he

had lived for seven-and-forty years. “He told me,” says she, “that, to the best

of my remembrance, he had slept but one hour and a half in twenty-four hours

for forty years together; and that, in the beginning, it was the greatest and

most troublesome mortification of all to overcome himself in point of sleep,

and that in order for this he was obliged to be always either kneeling or

standing on his feet: only when he slept he sat with his head leaning aside

upon a little piece of wood fastened for that purpose in the wall. As to the

extending his body at length in his cell it was impossible for him, his cell

not being above four feet and a half in length. In all these years he never put

on his capouch or hood, how hot soever the sun, or how violent soever the rain

might be; nor did he ever wear any thing upon his feet, nor any other garment

than his habit of thick coarse sackcloth, (without any other thing next his

skin,) and this short and scanty, and as straight as possible, with a short

mantle or cloak of the same over it. He told me, that when the weather was

extremely cold, he was wont to put off his mantle, and to leave the door and

the little window of his cell open, that when he put his mantle on again, and

shut his door, his body might be somewhat refreshed with this additional

warmth. It was usual with him to eat but once in three days; and he asked me

why I wondered at it; for it was very possible to one who had accustomed

himself to it. One of his companions told me, that sometimes he ate nothing at

all for eight days; but that perhaps might be when he was in prayer: for he

used to have great raptures, and vehement transports of divine love, of which I

was once an eye-witness. His poverty was extreme, and so also was his

mortification, even from his youth. He told me he had lived three years in a

house of his Order without knowing any of the friars but by their speech; for

he never lifted up his eyes: so that he did not know which way to go to many

places which he often frequented, if he did not follow the other friars. This

likewise happened to him in the roads. When I came to know him he was very old,

and his body so extenuated and weak, that it seemed not to be composed, but, as

it were, of the roots of trees, and was so parched up that his skin resembled

more the dried bark of a tree than flesh. He was very affable, but spoke

little, unless some questions were asked him; and he answered in few words, but

in these he was agreeable, for he had an excellent understanding.” St. Teresa

observes, that though a person cannot perform such severe penance as this

servant of God did, yet there are many other ways whereby we may tread the