Papa

Innocenzo II e santi Lorenzo e Callisto, Santa Maria in Trastevere

Pope Innocent II and Saints Lorenzo and Callisto, Santa Maria in Trastevere - Apse

Apsismosaik:

Callistus (Mitte) mit Maria und Jesus

Christus sowie Laurentius

von Rom ( 2. von links) und Papst Innozenz II. (ganz links), um 1140,

in der Kirche Santa

Maria in Trastevere

Papa

Innocenzo II e santi Lorenzo e Callisto, Santa Maria in Trastevere

Pope Innocent II and Saints Lorenzo and Callisto, Santa Maria in Trastevere - Apse

Apsismosaik:

Callistus (Mitte) mit Maria und Jesus

Christus sowie Laurentius

von Rom ( 2. von links) und Papst Innozenz II. (ganz links), um 1140,

in der Kirche Santa

Maria in Trastevere

Saint Calixte Ier

Pape (16 ème) de 217 à

222 (+ 222)

ou Calliste.

Le pape de l'indulgente

bonté. C'était un esclave chrétien. Son maître lui avait donné à gérer une

banque. Il la mit en faillite et, pour cette raison, fut condamné aux mines de

Sardaigne. La maîtresse de l'empereur Commode, chrétienne de cœur et non pas de

conduite, le connaissait et elle obtint sa grâce. Il se retira loin de Rome et

reçut des subsides du pape saint Victor,

ce qui lui permet de s'adonner à l'étude des Saintes Écritures. Affranchi,

Calixte devint l'archidiacre du pape saint

Zéphyrin et fonda le cimetière des catacombes qui porte son nom et où

furent enterrés tous les papes du IIIe siècle. Devenu pape à son tour, il

autorisa, à l'encontre de la loi civile, les mariages entre esclaves et

personnes libres. Il fit recevoir à la pénitence, malgré les tenants de la

rigueur, tous les pécheurs, si grandes soient leurs fautes. Il résista au

schisme d'Hippolyte et il

assouplit les normes d'entrée au catéchuménat. Celui-ci en deviendra enragé et

son rigorisme le conduisit hors de l'Église. Saint Calixte mourut massacré sans

qu'on sache pourquoi, lors d'une émeute.

* vidéo, Rome, ville des martyrs, visite des catacombes de Saint Calixte.

- Les

Catacombes chrétiennes de Rome.

Mémoire de saint Calliste

Ier, pape et martyr. Alors qu’il était diacre, après un long exil en Sardaigne,

il fut chargé par le pape saint Zéphyrin d’aménager, sur la voie Appienne, le

cimetière qui porte son nom; élu pape, il défendit la pureté de la foi,

réconcilia avec bienveillance les fidèles qui avaient failli dans la

persécution et acheva son épiscopat par le témoignage plus éclatant du martyre,

sans doute au cours d’une émeute contre les chrétiens au Transtévère, en 222.

Il fut mis au tombeau au cimetière de Calépode, sur la voie Aurélienne.

Martyrologe romain

Dieu aime à pardonner. Il

faut donc que les enfants de Dieu soient, eux aussi, pacifiques et

miséricordieux, qu’ils se pardonnent réciproquement comme le Christ nous a

pardonnés et nous ne jugions pas de peur d’être jugés

Tertullien - Traité

de la pudeur

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/2014/Saint-Calixte-Ier.html

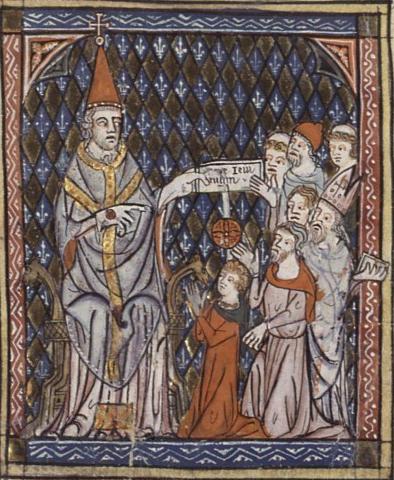

Saint Calixte Ier instituant

les jeûnes, iIllustration de Vies de saints, manuscrit de l'atelier de Jeanne et Richard

de Montbaston, Paris, XIVe siècle

San Callisto I papa insegna la dottrina cristiana ai giovani

Saint Calixte Ier

Pape et Martyr

(† 222)

A la mort de saint

Zéphirin, Calixte, Romain, fut élevé au Siège apostolique. Il ne fallait point,

pour gouverner l'Église, à une époque si tourmentée, un pasteur moins sage ni

moins vaillant. Il rendit le jeûne des Quatre-Temps, qui remontait aux Apôtres,

obligatoire dans toute l'Église.

C'est sous son règne que

l'on commença à bâtir des temples chrétiens, qui furent détruits dans les

persécutions suivantes. Il fit creuser le cimetière souterrain de la voie

Appienne, qui porte encore aujourd'hui son nom et qui renferme tant de précieux

souvenirs, entre autres le tombeau de sainte Cécile, la crypte de plusieurs

Papes, des peintures qui attestent la conformité de la foi primitive de

l'Église avec sa foi actuelle.

De nombreuses conversions

s'opérèrent sous le pontificat de saint Calixte. La persécution ayant éclaté,

il se réfugia, avec dix de ses prêtres, dans la maison de Pontien. La maison

fut bientôt enveloppée par des soldats qui reçurent la défense d'y laisser

rentrer aucune espèce de vivres. Pendant quatre jours, le Pape Calixte fut

privé de toute nourriture; mais le jeûne et la prière lui donnaient des forces

nouvelles. Le préfet, redoublant de cruauté, donna l'ordre de frapper chaque

matin le prisonnier à coups de bâton, et de tuer quiconque essayerait de

pénétrer pendant la nuit dans sa maison.

Une nuit, le prêtre

martyr Calépode, auquel Calixte avait fait donner une sépulture honorable,

apparut au Pontife et lui dit: "Père, prenez courage, l'heure de la

récompense approche; votre couronne sera proportionnée à vos souffrances."

Parmi les soldats qui

veillaient à la garde du prisonnier, il y avait un certain Privatus, qui

souffrait beaucoup d'un ulcère; il demanda sa guérison à Calixte, qui lui dit:

"Si vous croyez de tout coeur en Jésus-Christ et recevez le baptême au nom

de la Sainte Trinité, vous serez guéri. – Je crois, reprit le soldat, je veux

être baptisé, et je suis sûr que Dieu me guérira." Aussitôt après

l'administration du baptême, l'ulcère disparut sans laisser de trace. "Oui,

s'écrie le nouveau chrétien, le Dieu de Calixte est le seul vrai Dieu; les

idoles seront jetées aux flammes, et le Christ régnera éternellement!" Le

préfet eut connaissance de cette conversion et fit fouetter Privatus jusqu'à la

mort. Par son ordre, Calixte, une grosse pierre au cou, fut jeté de la fenêtre

d'une maison dans un puits.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_calixte_ier.html

Legendari di sancti istoriado uulgar, 1497 : Callisto martire

Legenda aurea, 1497 - Callisto martire, 1497, Biblioteca Europea di

Informazione e Cultura, Milan, Italy

Saint Callixte 1er,

Pape et martyr

La principale source

biographique de saint Callixte, le livre IX des Philosophoumena,

attribuées à saint Hippolyte, est un pamphlet, une caricature qui le présente

comme homme industrieux pour le mal et plein de ressources pour l'erreur,

qui guettait le trône épiscopal.

D’abord esclave de

Carpophore, chrétien de la maison de César, qui lui confia des fonds importants

pour ouvrir une banque dans le quartier de la piscine publique (les

futurs thermes de Caracalla). Des chrétiens lui remirent leur économies

qu’il dilapida avant de fuir pour s'embarquer à Porto. Rejoint par Carpophore,

Callixte se jeta à l'eau, mais repêché, il fut condamné à tourner la meule.

Carpophore, poursuivi par les créanciers de Callixte, l’envoya récupérer de

l'argent déposé chez des Juifs. Les Juifs traînèrent Callixte comme chrétien et

perturbateur de l'ordre public devant le préet Fuscien (185-189) ;

Carpophore protesta que Calliste n'était pas chrétien, mais seulement

banqueroutier. Callixte fut flagellé et envoyé comme forçat aux mines de

Sardaigne.

Marcia, maîtresse de

l'empereur Commode et chrétienne de cœur, demanda au pape Victor la liste des

déportés en Sardaigne. Un eunuque, le prêtre Hyacinthe, se rendit dans l'île et

fit libérer tous les détenus mais Callixte qui était absent de la liste

n’obtint que plus tard son élargissement. Le pape Victor lui donna une pension

mensuelle et l’envoya à Antium où, pendant une dizaine d'années, Calliste se

cultiva. Le successeur de Victor, Zéphyrin, fit rentrer Calliste à Rome,

l'inscrivit dans son clergé et le nomma diacre, chargé de gérer le cimetière.

Callixte organisa un nouveau cimetière via Appia, sans pour autant fermer

les catacombes de Priscille sur la via Salaria. Calliste lui a laissé son

nom.

Financier, un homme

d'action, d'administration et de gouvernement, plutôt que théologien, Callixte

était l’opposé d’Hippolyte, prêtre de brillante doctrine. Lorsque Callixte fut

élu à la succession de Zéphyrin, Hippolyte rallia une partie du clergé romain

et fit opposition jusqu'en 235.

Pour parer les

accusations d'Hippolyte qui l’accusait de montrer le Père comme souffrant avec

le Fils, Callixte condamna Sabellius, père du monarchianisme où l’on

distinguait mal les personnes de la Trinité. Sans condamner Hippolyte à

proprement parler, Callixte s'éleva contre ses théories qui semblaient

subordonner le Logos, le Christ, à Dieu : elles lui paraissaient suspectes

de dithéisme, c’est-à-dire d'introduire une dualité entre la nature divine du

Père et celle du Fils. De son mieux, avec une terminologie encore incertaine,

Callixte proclamait la foi traditionnelle.

Selon Hippolyte, Callixte

était d'un laxisme écœurant, pardonnant sur tout pour grossir son parti ;

il accueillait les transfuges des sectes, admettait dans son clergé les bigames

(les remariés), laissait des clercs prendre femme, reconnaissait (contre la loi

civile) les mariages entre hommes de vile condition et femmes nobles. Autant

d’accusations dont nous n’avons pas de preuves.

Callixte mourut très

probablement le 14 octobre 222, si l’on en croit la table philocalienne

des Depositiones martyrum (336) où il est mentionné avec les papes

Pontien, Fabien, Corneille, et Xyste II. Callixte mourut sous l'empereur

Alexandre Sévère, qui ne persécuta point les chrétiens, mais sa Passio le

fait jeter dans un puits, au Transtévère, par des furieux.

Il se pourrait donc que

saint Callixte ait péri lynché dans une bagarre : cela expliquerait son

absence, vraiment surprenante, du cimetière qui était sa chose, son entreprise

de prédilection, de la catacombe où reposent les papes du troisième siècle.

Les chrétiens le

portèrent au plus près, via Aurelia, au cimetière de Calépode,

le iuxta Callistum où le pape Jules I° (337-352) éleva la basilique

Sainte-Marie au Transtévère. Son corps aurait été porté en France à

Cysoing (Nord) au IXe siècle. Avant 900, un abbé de Cysoing le donna à

Notre-Dame de Reims.

Source : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/14.php

St Calixte Ier, pape et

martyr

Martyr en 222. Sa tombe

fut retrouvée en 1960. Culte attesté en 336.

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon. Calixte,

Romain d’origine, gouverna l’Église, Antonin Héliogabale étant empereur. Ce fut

ce Pape qui établit les Quatre-Temps et qui ordonna qu’en ces jours, le jeûne

reçu dans l’Église de tradition apostolique, serait obligatoire pour tous. Il

construisit la basilique de Sainte Marie du Transtévère et agrandit un ancien

cimetière sur la voie Appienne, où beaucoup de saints Prêtres et Martyrs

avaient été ensevelis, et qu’on appela depuis cimetière de Calixte.

Cinquième leçon. Ce fut

aussi par une inspiration de sa piété, qu’il eut soin de faire rechercher le

corps du Prêtre et Martyr Callépode, qui avait été jeté dans le Tibre, et,

quand on l’eut trouvé, de le faire ensevelir avec honneur. Ayant baptisé

Palmatius, personnage consulaire, et Simplicius, illustre sénateur, ainsi que

Félix et Blanda, qui, plus tard, subirent tous le martyre, il fut incarcéré,

et, dans sa prison, guérit d’une manière merveilleuse le soldat Privatus, qui

était couvert d’ulcères, et le gagna au Christ. Bientôt après, ce soldat frappé

jusqu’à la mort à coups de fouets plombés, succomba pour Celui dont il venait

de recevoir la foi.

Sixième leçon. Calixte occupa le Saint-Siège cinq ans, un mois et douze jours. En cinq ordinations, au mois de décembre, il ordonna seize Prêtres, quatre Diacres et sacra huit Évêques. Après lui avoir fait endurer la faim et subir de nombreuses fustigations, on le précipita dans un puits. Ainsi couronné du martyre, sous l’empereur Alexandre, il fut déposé, le premier jour des ides d’octobre, dans le cimetière de Callépode, sur la voie Aurélia, au troisième mille au sortir de Rome. Plus tard, on transporta son corps dans la basilique de Sainte-Marie du Transtévère, bâtie par lui, et on le plaça sous le maître autel, où il est l’objet d’une très grande vénération.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/14-10-St-Calixte-Ier-pape-et

Also

known as

Callixtus I

Calixtus I

Profile

Born a slave,

owned by Carpophorus, a Christian in

the household of Caesar. His master entrusted a large sum to Callistus to open

a bank,

which took in several deposits, made several loans to people who refused to pay

them back, and went broke. Knowing he would be personally blamed and punished,

Callistus fled, but was caught and

returned to his owner. Several depositors begged for his life, believing he had

not lost the money, but had stolen and hid it. They were wrong; he wasn’t

a thief,

just a victim, but he was sentenced to work the tin

mines. By a quirk of Roman law, the ownership of Callistus was transferred

from Carpophorus to the state, and when he was later ransomed out of his

sentence with a number of other Christians,

he became a free man. Pope Zephyrinus put

Callistus in

charge of the Roman public burial grounds, today still called

the Cemetery of Saint Callistus. Archdeacon.

Sixteenth Pope.

Most of what we know

about him has come down to us from his critics, including an anti-Pope of

the day. Callistus was on more than one occasion accused of heresy for

such actions as permitting a return to Communion for

sinners who had repented and done penance, or for proclaiming that differences

in economic class were no barrier to marriage.

This last put him in conflict with Roman civil law, but he stated that in

matters concerning the Church and

the sacraments, Church law trumped

civil law.

In both cases he taught what the Church has

taught for centuries, including today, and though a whole host of schismatics wrote against

him, his crime seems to have been to practice orthodox Christianity. Martyred in

the persecutions of Alexander

Severus.

Papal Ascension

c.218

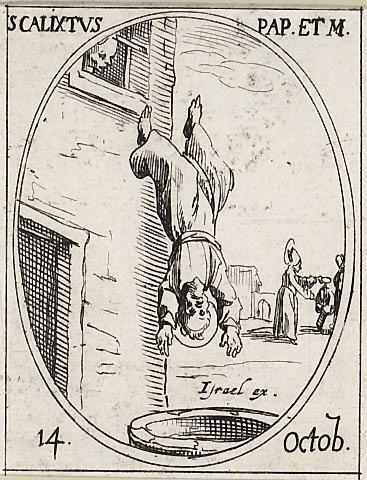

legend says he was killed by

being thrown down a well with a millstone around his neck, but there is no

solid evidence

pope with

a millstone on

him or nearby

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by John Chapman

Lives

and Times of the Popes, by Alexis-François Artaud de Montor

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Little

Pictorial Lives of the Saints

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

notitia

in latin

Works

MLA

Citation

“Pope Saint Callistus

I“. CatholicSaints.Info. 28 July 2022. Web. 9 May 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/pope-saint-callistus-i/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pope-saint-callistus-i/

Vitrail de Saint Calixte de l'Église Saint-Calixte de Lambersart

Vitrail

de Saint Calixte de l'Église Saint-Calixte de Lambersart (détail)

Book of

Saints – Callistus – 14 October

Article

CALLISTUS (CALIXTUS)

(Saint) Pope, Martyr (October 14) (3rd century) A Roman by birth, the successor

of Pope Saint Zephyrinus, whose Archdeacon or representative he had been. His

five years of vigorous Pontificate were marked by many salutary measures: the

moderating of the rigour of the penitential discipline; the repression of the

Patripassians, Sabellians and other heretics; the fixing of the Ember Day

Fasts, etc. etc. He seems to have met with much opposition, and at length,

probably in a riot or outburst of the heathen against the Christians, was flung

headlong from the window of a high building in the Trastevere quarter (A.D.

223). He was buried in the Catacombs of Saint Calepodius, his contemporary, and

his relics now repose together with those of that Saint in the Church of Santa

Maria in Trastevere, close to the scene of his martyrdom. The document called

the Philosophoumena, an anonymous production of the heretics of his time,

written to besmirch the memory of the holy Pope, notwithstanding the credit

given to it by Bunsen and by Protestant writers in general, has been amply

refuted by Dollinger and others.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Callistus”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 20

September 2012.

Web. 13 October 2020. <http://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-callistus-14-october/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-callistus-14-october/

Portrait

of en:Pope Callistus I in the en:Basilica of Saint Paul

Outside the Walls, Rome

Ritratto

di it:Papa Callisto I nella it:Basilica di San Paolo fuori

la Mura, Roma

St. Callistus I

Feastday: October 14

Patron: of

Cemetery workers

Imagine that your

biography was written by an enemy of yours. And that its information was all

anyone would have not only for the rest of your life but

for centuries to come. You would never be able to refute it -- and even if you

couldno one would believe you because your accuser was a saint.

That is the problem we

face with Pope Callistus I who died about 222. The only story of his life we

have is from someone who hated him and what he stood for, an author identified

as Saint Hippolytus, a rival candidate for the chair of Peter. What had made

Hippolytus so angry? Hippolytus was very strict and rigid in his adherence to

rules and regulations. The early Church had been very rough on those who

committed sins of adultery, murder, and fornication. Hippolytus was enraged by

the mercy that Callistus showed to these repentant sinners, allowing them back

into communion of the Church after they had performed public penance.

Callistus' mercy was also matched by his desire for equality among Church

members, manifested by his acceptance of

marraiges between free people and slaves. Hippolytus saw all of this as a degradation of

the Church, a submission to lust and

licentiousness that reflected not mercy and holiness in

Callistus but perversion and fraud.

Trying to weed out the

venom to find the facts of Callistus' life in

Hippolytus' account, we learn that Callistus himself was a slave (something

that probably did not endear him to class-conscious Hippolytus). His master,

Carporphorus made him manager of a bank in the Publica Piscina sector

of Rome where

Callistus took in the money of other Christians. The bank failed -- according

to Hippolytus because Callistus spent the money on his own pleasure-seeking. It

seems unlikely that Carporphorus would trust his good name

and his fellow Christians' savings to someone that unreliable.

Whatever the reason,

Callistus fled the city by ship in order to escape punishment. When his master

caught up with him, Callistus jumped into the sea (according to Hippolytus, in

order to commit suicide). After Callistus was rescued he was brought back to

Rome, put on trial, and sentenced to a cruel punishment -- forced labor on the

treadmill. Carporphorus took pity on his former slave and manager and Callistus

won his release by convincing him he could get some of the money back from

investors. (This seems to indicate, in spite of Hippolytus' statements, that

the money was not squandered but lent or invested

unwisely.) Callistus' methods had not improved with desperation and when he

disrupted a synagogue by

shouting for money, he was arrested and sentenced again.

This time he

was sent to the mines. Other Christians who had been sentenced there because of

their religion were

released by negotiations between the emperor and the Pope (with the help of the

emperor's mistress who was friendly toward Christians). Callistus accidentally

wound up on the same list with the persecuted brothers and sisters. (Hippolytus

reports that this was through extortion and connniving on Callistus' part.)

Apparently, everyone, including the Pope, realized Callistus did not deserve

his new freedom but unwilling to carry the case further the Pope gave Callistus

an income and situation -- away from Rome. (Once again, this is a point for

suspecting Hippolytus' account. If Callistus was so despicable and

untrustworthy why provide him with an income and a situation? Leaving him free

out of pity is one thing, but giving money to a convicted criminal and slave is

another. There must have been more to the story.)

About nine or ten years

later, the new pope Zephyrinus recalled Callistus to Rome. Zephyrinus was good-hearted

and well-meaning but had no understanding of theology. This was disastrous in

a time when

heretical beliefs were springing up everywhere. One minute Zephyrinus would

endorse a belief he

thought orthodox and the next he would embrace the opposite statement.

Callistus soon made his value known, guiding Zephyrinus through theology to

what he saw as orthodoxy. (Needless to say it was not what Hippolytus felt was

orthodox enough.) To a certain extent, according to Hippolytus, Callistus was

the power behind the Church before he even assumed the bishopric of Rome.

When Zephyrinus died in

219, Callistus was proclaimed pope over the protests of his rival candidate

Hippolytus. He seemed to have as strong a hatred of heresy as

Hippolytus, however, because he banished one of the heretics named

Sabellius.

Callistus came to power

during a crucial time of

the Church. Was it going to hang on to the rigid rules of previous years and

limit itself to those who were already saints or was it going to embrace

sinners as Christ commanded?

Was its mission only to a few holy ones or to the whole world, to the healthy

or to the sick? We can understand Hippolytus' fear -- that hypocritical

penitents would use the Church and weaken it in the time when

they faced persecution. But Callistus chose to trust God's mercy and love and

opened the doors. By choosing Christ's mission, he chose to spread the Gospel

to all.

Pope Callistus is listed

as a martyr but

we have no record of how he was martyred or by whom. There were no official

persecutions at the time, but he may well have been killed in riots against

Christians.

As sad as it is to

realize that the only story we have of his life is

by an enemy, it is glorious to see in it the fact that the Church is large

enough not only to embrace sinners and saints, but to proclaim two people

saints who hold such wildly opposing views and to elect a

slave and an alleged ex-convict to guide the whole Church. There's hope for

all of us then!

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=31

Statue de Saint Calixte dans l'Église Saint-Calixte de Lambersart

Chapelle

Saint-Calixte dans l'Église Saint-Calixte de Lambersart - reliquaire

Chapelle Saint-Calixte dans l'Église Saint-Calixte de Lambersart - relique de Saint-Calixte

St. Calixtus

Feastday: October 14

Patron: of

Cemetery workers

St. Calixtus (Callistus)

Pope and Martyr October

14 A.D. 222 The name of St. Callistus is

rendered famous by the ancient cemetery which he beautified, and which, for the

great number of holy martyrs whose bodies were there deposited, was the most

celebrated of all those about Rome. He was a Roman by birth, succeeded St.

Zephirin in the pontificate in 217 or 218, on the 2d of August, and governed

the church five years and two months, according to the true reading of the most

ancient Pontifical, compiled from the registers of the Roman Church, as

Henschenius, Papebroke, and Moret show, though Tillemont and Orsi give him only

four years and some months. Antoninus Caracalla, who had been liberal to his

soldiers, but the most barbarous murderer and oppressor of the people having

been massacred by a conspiracy, raised by the contrivance of Macrinus, on the

8th of April, 217, who assumed the purple, the empire was threatened on every

side with commotions. Macrinus bestowed on infamous pleasures at Antioch that time which

he owed to his own safety, and to the tranquillity of the state, and gave an

opportunity to a woman to

overturn his empire. This was Julia Moesa, sister to Caracallata mother, who

had two daughters, Sohemis and Julia Mammaea. The latter was mother of

Alexander Severus, the former of Bassianus, who, being priest of

the sun, called by the Syrians Elagabel, at Emesa, in Phoenicia, was surnamed

Heliogabalus. Moesa, being rich and liberal, prevailed for money with the army

in Syria to

proclaim him emperor; and Macrinus, quitting Antioch, was defeated and slain in

Bithynia in 219, after he had reigned a year and two months, wanting three

days. Heliogabalus, for his unnatural lusts, enormous prodigality and gluttony,

and mad pride and

vanity, was one of the most filthy monsters and detestable tyrants that Rome ever

produced. He reigned only three years, nine months, and four days, being

assassinated on the 11th of March, 222, by the soldiers, together with his

mother and favorites. Though he would be adored with his new idol, the sun, and

in the extravagance of his folly and Vices, surpassed, if possible, Caligula

himself, yet he never persecuted the Christians. His cousin-german and

predecessor, Alexander, surnamed Severus, was, for his clemency, modesty,

sweetness, and prudence, one of the best of princes. He discharged the officers

of his predecessor, reduced the soldiers to their duty, and kept them in awe by

regular pay. He suffered no places to be bought saying, "He that buys must

sell." Two maxims which he learned of the Christians were the rules by

which he endeavored to square his conduct. The first was, "Do to all men

as you would have others do to you." The Second, That all places of

command are to be bestowed on those who are the best qualified for them; though

he left the choice of the magistrates chiefly to the people, whose lives and

fortunes depend on them. He had in his private chapel the

images of Christ, Abraham, Apollonius of Tyana, and Orpheus, and learned of his

mother, Mammaea, to have a great esteem for the Christians. It reflects great

honor on our pope that this wise emperor used always to admire with what

caution and solicitude the choice was made of persons that were promoted to

the priesthood among

the Christians, whose example he often proposed to his officers and to the

people, to be imitated in the election of

civil magistrates. It was in his peaceable reign that the Christians first

began to build Churches, which were demolished in the succeeding persecution.

Lampridius, this emperor's historian tells us, that a certain idolater, putting

in a claim to an oratory of

the Christians, which he wanted to make an eating-house of the emperor adjudged

the house ten the bishop of

Rome, saying, it were better it should serve in any kind to the divine worship

than to gluttony, in being made a cook's shop. To the debaucheries of

Heliogabalus, St. Callistus opposed fasting and

tears, and he every way promoted exceedingly true religion and

virtue. His apostolic labors were recompensed with the crown of martyrdom on

the 12th of October, 222. His feast is marked on this day in the ancient Martyrology of

Lucca. The Liberian Calendar places him in the list of martyrs, and testifies

that he was buried on the 14th of this month in the cemetery of Calepodius, on

the Aurelian way,

three miles from Rome. The Pontificals ascribe to him a decree appointing

the four fasts called Ember-days; which is confirmed by ancient Sacramentaries,

and other monuments quoted by Moretti. He also decreed, that ordinations should

be held in each of the Ember weeks. He founded the church of the Blessed

Virgin Mary beyond

the Tiber. In the calendar published by Fronto le Duc he is styled a confessor;

but we find other martyrs sometimes called confessors. Alexander himself never

persecuted the Christians; but the eminent lawyers of that time, whom this

prince employed in the principal magistracies, and whose decisions are

preserved in Justinian's Digestum, as Ulpian, Paul, Sabinus, and others, are

known to have been great enemies to the faith, which they considered as an

innovation in the commonwealth. Lactantius informs us that Ulpian bore it so

implacable a hatred, that, in a work where he treated on the office of a

proconsul, he made a collection of all the edicts and laws which had been made

in all the foregoing reigns against the Christians, to incite the governors to

oppress them in their provinces. Being himself prefect of the praetorium, he

would not fail to make use of the power which his office gave him, when upon

complaints he found a favorable opportunity. Hence several martyrs suffered in

the reign of Alexander. If St. Callistus was

thrown into a pit, as his Acts relate, it

seems probable that he was put to death in some popular tumult. Dion mentions

several such commotions under this prince, in one of which the praetorian

guards murdered Ulpian, their own prefect. Pope Paul I. and his successors,

seeing the cemeteries without

walls, and neglected after the devastations of the barbarians, withdrew from

thence the bodies of the most illustrious martyrs, and had them carried to the

principal churches of the city. Those of SS. Callistus and Calepodius were

translated to the church off St. Mary, beyond the Tiber. Count Everard, lord of

Cisoin or Chisoing, four leagues from Tournay, obtained of Leo IV., about the

year 854, the body of St. Callistus, pope and martyr, which he placed in

the abbey of Canon Regulars which

he had founded at Cisoin fourteen years before; the church of which place was

on this account dedicated in honor of St. Callistus. These circumstances are

mentioned by Fulco, archbishop of

Rheims, in a letter which he wrote to pope Formosus in

890. The relics were

removed soon after to Rheims for fear of the Normans, and never restored to

the abbey of

Cisoin. They remain behind the altar of our Lady at Rheims. Some of the relics,

however, of this pope are kept with those of St. Calepodius martyr,

in the church of St. Mary Trastevere

at Rome. A portion was formerly possessed at Glastenbury. Among the sacred

edifices which, upon the first transient glimpse of favor, or at least

tranquillity that the church enjoyed at Rome, this holy pope erected, the most

celebrated was the cemetery which he enlarged and adorned on the Appian road,

the entrance of which is at St. Sebastian's, a monastery founded by Nicholas

I., now inhabited by reformed Cistercian monks. In it the bodies of SS. Peter

and Paul lay for some time, according to Anastasius, who says that the devout

lady Lucina buried St. Cornelius in

her own farm near this place; whence it for some time took

her name, though she is not to be confounded with Lucina who buried St. Paul's

body on the Ostian way, and built a famous cemetery on the Aurelian way.

Among many thousand martyrs deposited in this place were St. Sebastian, whom

the lady Lucina interred, St. Cecily, and several whose tombs pope Damasus

adorned with verses. In the assured faith of

the resurrection of the flesh, the saints, in all ages down from Adam, were

careful to treat their dead with religious respect, and to give them a modest

and decent burial. The commendations which our Lord bestowed

on the woman who

poured precious ointments upon him a little before his death, and the devotion

of those pious persons who took so much care of our Lord's funeral, recommended

this office of charity; and the practice of the primitive Christians in this

respect was most remarkable. Julian the Apostate, writing to a chief priest of

the idolaters, desires him to observe three things, by which he thought Atheism (so

he called Christianity) had gained most upon the world, namely, "Their

kindness and charity to strangers, their care for the burial of their dead, and

the gravity of their carriage." Their care of their dead consisted not in

any extravagant pomp, in which the pagans far outdid them, but in a modest

religious gravity and respect which was most pathetically expressive of their

firm hope of

a future resurrection, in which they regarded the mortal remains of their dead

precious in the eyes of God, who watches over them, regarding them as the apple

of his eye, to be raised one day in the brightest glory, and made shining

lusters in the heavenly Jerusalem.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=870

Le

reliquaire de saint Calixte, en l'église Saint-Évrard-Saint-Calixte de Cysoing,

dans le département du Nord.

Pope Callistus I

(Written by most Latins,

Augustine, Optatus, etc. CALLIXTUS or CALIXTUS).

Martyr,

died c. 223. His contemporary, Julius

Africanus, gives the date of

his accession as the first (or second?) year of Elagabalus,

i.e., 218 or 219. Eusebius and

the Liberian catalogue agree in giving him five years ofepiscopate.

His Acts are spurious, but he is the earliest pope found

the fourth-century "Depositio Martirum", and this

is good evidence that he was really a martyr,

although he lived in a time of peace under Alexander

Severus, whose mother was a Christian.

We learn from the "Historiae Augustae" that a spot on which he had

built anoratory was claimed by the tavern-keepers, popinarii, but the

emperor decided that the worship of any god was better than

a tavern. This is said to have been the origin of Sta. Maria in

Trastevere, which was built, according to the Liberian catalogue,

by Pope Julius, juxta Callistum. In fact the Church of St.

Callistus is close by, containing a well into which legend says his

body was thrown, and this is probably the church he built, rather

than the more famous basilica. He was buried in

the cemetery of Calepodius on the Aurelian Way, and

his anniversary is given by the "Depositio Martirum" (Callisti in viâ

Aureliâ miliario III) and by the subsequent martyrologies on

14 October, on which day his feast is

still kept. His relics were

translated in the ninth century to Sta. Maria in Trastevere.

Our chief knowledge of

this pope is

from his bitter enemies, Tertullian and

the antipope who

wrote the "Philosophumena", no doubt Hippolytus.

Their calumnies are

probably based on facts. According to the "Philosophumena" (c. ix)

Callistus was the slave of Carpophorus, a Christian of

the household of Caesar. His master entrusted large sums of money to

Callistus, with which he started a bank in which brethren and widows lodged

money, all of which Callistus lost. He took to

flight. Carpophorus followed him to Portus, where Callistus had

embarked on a ship. Seeing his master approach in a boat,

the slave jumped into the sea, but was prevented from drowning

himself, dragged ashore, and consigned to the punishment reserved

for slaves, the pistrinum, orhand-mill. The brethren, believing that

he still had money in his name, begged that he might be released. But he had

nothing, so he again courted death by insulting the Jews at

their synagogue.

The Jews haled

him before theprefect Fuscianus. Carpophorus declared that

Callistus was not to be looked upon as a Christian,

but he was thought to be trying to save his slave, and Callistus

was sent to the mines in Sardinia.

Some time after this,Marcia, the mistress of Commodus,

sent for Pope

Victor and asked if there were any martyrs in Sardinia.

He gave her the list, without including Callistus. Marcia sent a

eunuch who was a priest (or

"old man") to release theprisoners.

Callistus fell at his feet, and persuaded him to take him

also. Victor was annoyed; but being a compassionate man, he

kept silence. However, he sent Callistus to Antium with a

monthly allowance. When Zephyrinus became pope,

Callistus was recalled and set over the cemetery belonging to

the Church,

not a private catacomb;

it has ever since borne Callistus's name. He obtained great influence over

the ignorant,

illiterate, and grasping Zephyrinus by bribes.

We are not told how it came about that the runaway slave (now free

by Roman

law from his master, who had lost his rights when

Callistus was condemned to penal servitude to the State) became archdeacon and

then pope.

Döllinger and De

Rossi have demolished this contemporary scandal.

To begin with, Hippolytus does

not say that Callistus by his own fault lost the money deposited with him. He

evidently jumped from the vessel rather to escape than to commit suicide.

That Carpophorus, a Christian,

should commit a Christian slave to

the horrible punishment of the pistrinum does not speak well for

the master's character. The intercession of the Christians for

Callistus is in his favour. It is absurd to suppose that he courted death by

attacking a synagogue;

it is clear that he asked the Jewish money-lenders to repay what

they owed him, and at some risk to himself. The declaration

ofCarpophorus that Callistus was no Christian was scandalous and untrue. Hippolytus himself

shows that it was as aChristian that

Callistus was sent to the mines, and therefore as a confessor, and that it

was as a Christian that

he was released. If Pope Victor granted Callistus a

monthly pension, he need not suppose that he regretted his release. It is

unlikely that Zephyrinus was ignorant and

base. Callistus could hardly have raised himself so high without considerable

talents, and the vindictive spirit exhibited by Hippolytus and

his defective theology explain

why Zephyrinus placed

his confidence rather in Callistus than in the

learned disciple of Irenaeus.

The orthodoxy of

Callistus is challenged by both Hippolytus and Tertullian on

the ground that in a famous edict he granted Communion after

due penance to those who had committed adultery and

fornication. It is clear that Callistus based his decree on

the power of binding and loosing granted to Peter, to his successors,

and to all in communion with them: "As to thy decision", cries

the Montanist Tertullian,

"I ask, whence dost thou usurp thisright of the Church?

If it is because the Lord said to Peter: Upon this rock I will

build My Church, I will give thee the keys of the kingdom

of heaven', or whatsoever though bindest or loosest on earth

shall be bound or loosed in heaven',

that thou presumest that this power of binding and loosing has been handed down

to thee also, that is to every Church in communion

with Peter's (ad omnem ecclesiam Petri propinquam, i.e. Petri

ecclesiae propinquam), who art thou that destroyest and alterest the

manifest intention of the Lord, who conferred this

onPeter personally and alone?" (On

Pudicity 21) The edict was an order to the

whole Church (ib., i): "I hear that an edict has been published,

and a peremptory one; the bishop of bishops,

which means the Pontifex Maximus, proclaims: I remit the crimes

of adultery and

fornication to those who have done penance." Doubtless Hippolytus and Tertullian were

upholding a supposed custom of earlier times, and the pope in decreeing a

relaxation was regarded as enacting a new law. On this point it is

unnecessary to justify Callistus. Other complaints of Hippolytus are

that Callistus did not put converts from heresy to

public penance for sins committed

outside the Church (this

mildness was customary in St.

Augustine's time; that he had received into his "school"

(i.e. The Catholic Church)

those whom Hippolytus had excommunicated from

"The Church" (i.e., his own sect);

that he declared that a mortal sin was

not ("always", we may supply) a sufficient reason

for deposing a bishop. Tertullian (De

Exhort. Castitatis, vii) speaks with reprobation of bishops who

had been married more than once, and Hippolytus charges

Callistus with being the first to allow this, against St.

Paul's rule. But in the East marriages before baptism were

not counted, and in any case the law is

one from which the pope can

dispense if necessity arise. Again Callistus allowed the lower clergy to marry,

and permitted noble ladies to marry low persons and slaves,

which by the Roman

law was forbidden; he had thus given occasion for infanticide.

Here again Callistus was rightly insisting on the distinction between

the ecclesiastical law of marriage and the civil

law, which later ages have always taught. Hippolytus also

declared that rebaptizing (of heretics)

was performed first in Callistus's day, but he does not state that Callistus

was answerable for this. On the whole, then, it is clear that the Catholic church sides

with Callistus against the schismatic Hippolytus and

the heretic Tertullian.

Not a word is said against the character of Callistus since his

promotion, nor against the validity of his election.

Hippolytus,

however, regards Callistus as a heretic.

Now Hippolytus's own Christology is

most imperfect, and he tells us that Callistus accused him of Ditheism. It

is not to be wondered at, then, if he calls Callistus the inventor of a kind of

modified Sabellianism.

In reality it is certain that Zephyrinus and

Callistus condemned various Monarchians and Sabellius himself,

as well as the opposite error of Hippolytus.

This is enough to suggest that Callistus held the Catholic Faith.

And in fact it cannot be denied that the Church of Rome must

have held aTrinitarian doctrine not

far from that taught by Callistus's elder contemporary Tertullian and

by his much younger contemporary Novatian--a doctrine which

was not so explicitly taught in the greater part of the East for a

long period afterwards. The accusations of Hippolytus speak

for the sure tradition of the Roman

Church and for itsperfect orthodoxy and

moderation. If we knew more

of St. Callistus from Catholic sources,

he would probably appear as one of the greatest of the popes.

Sources

The Acts of St. Callistus were uncritically defended in the Acta SS., 14 Oct.; and by MORETTI, De S. Callisto P. et M. (Rome, 1752). The Philosophumena were first published in 1851. On the story of Callistus BUNSEN, Hippolytus and his Age (London, 1852), and CH. WORDSWORTH, St. Hippolytus and the Church of Rome (London, 1853) are worthless. DOLLINGER'S great work Hippolytus und Kallistus (Ratisbon, 1853), tr. PLUMMER (Edinburgh, 1876) is still the chief authority. See also DE ROSSI, Bulletino di Arch. Crist., IV (1886); NORTHCOTE AND BROWNLOW, Roma Sotterranea (London, 1879), I, 497-505. De Rossi observes that the Liber Pontificalis calls Callistus the son of Domitius, and he found Callistus Domitiorum stamped on some titles of the beginning of the second century. Further there is extant an inscription of a Carpophorus, a freedman of M. Aurelius. The edict of Callistus on penance has been restored with too much assurance by ROLFFS, Das Indulgenz-Edikt des römischen Bischofs Kallist (Leipzig, 1893), Harnack thinks that Callistus also issued a decree about fasting, and that other writings of his may have been known to Pseudo-Isidore, who attributed two letters to him (which will be found in the Councils, in HINSCHIUS, etc.); one of these seems to connect itself with the decision attributed to Callistus by Hippolytus; see HARNACK, Chronol., II, 207-8. On the Catacomb of St. Callistus see DE ROSSI, Roma Sotterranea (Rome, 1864-77); NORTHCOTE AND BROWNLOW, Roma Sotterranea (London, 1879).

Chapman, John. "Pope Callistus I." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1908. 14 Aug.

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03183d.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Benjamin F. Hull.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. November 1, 1908. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03183d.htm

Chiesa

parrocchiale di San Callisto Papa e Martire a Cornegliano Laudense.

Golden Legend

– Life of Saint Calixtus

Here followeth of Saint

Calixtus, and first of his name.

Calixtus is said

of caleo, cales, that is to say, eschauffe or make warm. For he was

hot and burning, first in the love of God, and after, he was hot and burning in

getting and purchasing souls, and thirdly, he was hot in destroying the false

idols, and also in showing the pains for sin.

Of Saint Calixtus.

Calixtus the pope was

martyred the year of our Lord two hundred and twenty-two, under Alexander the

emperor. And by the works of the said emperor the most apparent part of Rome

was then burnt by vengeance of God, and the left arm of the idol Jupiter, which

was of fine gold, was molten. And then all the priests

of the idols went to the emperor Alexander, and required him that the gods that

were angry might be appeased by sacrifices. And as they sacrificed on a

Thursday by the morn, the air being all clear, four of the priests

of the idols were smitten to death with one stroke of thunder. And the altar of

Jupiter was burnt, so that all the people fled out of the walls of Rome. And

when Palmatius, consul, knew that Calixtus with his clerks. hid him over the

water of Tiber, he required that the christian men, by whom this evil was

happed and come, should be put out for to purge and cleanse the city. And when

he had received power for to do so, he hasted him incontinent with his knights

for to accomplish it, and anon they were all made blind. And then Palmatius was

afeard, and showed this unto Alexander. And then the emperor commanded that the

Wednesday all the people should assemble and sacrifice to Mercury, that they

might have answer upon these things. And as they sacrificed, a maid of the

temple, which was named Juliana, was ravished of the devil, and began to cry:

The god of Calixtus is very true and living, which is wroth and hath

indignation of our ordures. And when Palmatius heard that, he went over Tiber

unto the city of Ravenna unto Saint Calixtus, and was

baptized of him, he, his wife, and all his meiny. And when the emperor heard

that, he did do call him, and delivered him to Simplician, senator, for to warn

and treat him by fair words, because he was much profitable for the commune.

And Palmatius persevered in fastings and in prayers. Then came to him a man

which promised to him that if he healed his wife, which had the palsy, that he

would believe in God anon. And when Palmatius had adored and prayed, the woman

that was sick arose, and was all whole, and ran to Palmatius saying: Baptize me

in the name of Jesu Christ, which hath taken me by the hand and lifted me up.

Then came Calixtus and baptized her and her husband, and Simplician and many

others. And when the emperor heard hereof, he sent to smite off the heads of

all them that were baptized, and made Calixtus to live five days in the prison

without meat and drink, and after, he saw that Calixtus was the more comforted

and glad, and commanded that he should every day be beaten with staves. And

after, he made a great stone to be bounden to his neck, and to be thrown down

from an height out of a window into a pit. And Asterius, his priest,

took up the body out of the pit, and after, buried the body in the cemetery of

Calipodium.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/golden-legend-life-of-saint-calixtus/

La

chiesa parrocchiale dei Santi Simone, Giuda e Callisto a Muzza Sant’Angelo,

frazione di Cornegliano Laudense.

Callistus (Callixtus) I,

Pope M (RM)

Died c. 222; honored as a martyr in Todi, Italy, on August 14. Most of what is

known about Callistus comes from untrustworthy sources, such as his

arch-opponent. Callistus was a Roman from the Trastevere section of Rome, son

of Domitius. His contemporary Saint Hippolytus says that when Callistus, a

young Christian slave, was put in charge of a bank by his Christian master

Carpophorus, he lost the money deposited with him by other Christians. He fled

from Rome but was caught on board a ship off Porto (Portus). To escape capture,

he jumped overboard into the sea. He was rescued and taken back to Carpophorus.

He was sentenced to the dreaded punishment reserved for slaves--the hand mill.

He was released at the request of the creditors, who hoped he might be able to

recover some of the money, but was rearrested for fighting in a synagogue when

he tried to borrow or collect debts from some Jews. Denounced now as a Christian,

Callistus was sentenced to work in the mines of Sardinia. Finally, he was

released with other Christians at the request of Marcia, a mistress of Emperor

Commodus. His health was so weakened that his fellow Christians sent him to

Antium to recuperate and he was given a pension by Pope Victor I.

About 199, Callistus was

appointed by Pope Saint Zephyrinus as supervisor of the public Christian burial

grounds on the Via Appia (which would come to be called the cemetery of San

Callistus). (In its papal crypt most of the bishops of Rome from Zephyrinus to

Eutychian, except Cornelius and Callistus, were buried.) He is said to have

expanded the cemetery, bringing private portions into communal possession.

He was ordained by Saint

Zephyrinus as a deacon and became his friend and advisor. When Zephyrinus died

in 217, Callistus was elected pope by popular vote of the Roman people and

clergy. Soon thereafter he was denounced by Saint Hippolytus (himself a nominee

for the papal seat) for his kindness.

Compassionate towards

repentant sinners, Callistus established the practice of the absolution of all

repented sins. Saint Hippolytus was especially upset by the pope's admitting to

communion those who had repented for murder, adultery, and fornication. Saint

Hippolytus, Tertullian, Novatian, and the Rigorists called Callistus a heretic,

claiming that he taught that committing a mortal sin was not sufficient to

depose a bishop, that multi- married men could be admitted to the clergy, and

that marriages between free women and Christian slaves were legitimate.

This last was Callistus's

resolution of the problem of wealthy Christian women who were unable to find

suitable Christian husbands. He saw marriages to Christian slaves as a better

alternative than risking excommunication for themselves and their children by

marrying pagans.

He was known for his

gentleness and forgiveness. Hippolytus also accused him of leniency to

heretics, despite the fact that Callistus had excommunicated Sabellius, the

leader of the heretics who denied the plurality of the Divine Persons

(Monarchianism).

It is possible that

Callistus was martyred around 222, perhaps during a popular uprising, but the

legend that he was thrown down a well has no authority. He was buried on the

Aurelian Way.

The chapel of San

Callistus in Trastevere is probably a successor to the one built by the pope on

a piece of land adjudged to the Christians by Alexander Severus against some

innkeepers--the emperor declared that any religious rites were better than a

tavern (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Delaney, Encyclopedia, White)

Saint Callistus is

depicted in art wearing a red robe with a tiara (sign of a pope); or being

thrown into a well with a millstone around his neck; or with a millstone around

his neck (White). Often there is a fountain near him (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1014.shtml

Catedral de San Calixto de Timaná - Huila. (Parroquia mas antigua de la Diócesis de Garzón). A Pulido-Villamarín

Catedral de San Calixto de Timaná - Huila. (Parroquia mas antigua de la Diócesis de Garzón). A Pulido-Villamarín

Catedral

de San Calixto de Timaná - Huila. (Parroquia mas antigua de la Diócesis de Garzón).

A Pulido-Villamarín

Pictorial

Lives of the Saints – Saint Callistus, Pope, Martyr

Early in the third

century, Callistus, then a deacon,

was entrusted by Pope Saint Zephyrinus

with the rule of the clergy, and set by him over the cemeteries of the

Christians at Rome; and, at the death of Zephyrinus, Callistus, according to

the Roman usage, succeeded to the Apostolic See. A decree is ascribed to him

appointing the four fasts of the Ember seasons, but his name is best known in

connection with the old cemetery on the Appian Way, which was enlarged and

adorned by him, and is called to this day the Catacomb of Saint Callistus.

During the persecution under the Emperor Severus, Saint Callistus was driven to

take shelter in the poor and populous quarters of the city; yet, in spite of

these troubles, and of the care of the Church, he made diligent search for the

body of Calipodius, one of his clergy who had suffered martyrdom shortly

before, by being cast into the Tiber. When he had found it he was full of joy,

and buried it, with hymns of praise. Callistus was martyred October 14th, 223.

Reflection – In the body

of a Christian we see that which has been the temple of the Holy Ghost, which

even now is precious in the eyes of God, who will watch over it, and one day

raise it up in glory to shine forever in His kingdom. Let our actions bear

witness to our belief in these truths.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-callistus-pope-martyr/

St. Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit Ausstattung.

St. Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit Ausstattung.

St. Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit Ausstattung.

St. Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit Ausstattung.

St. Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit Ausstattung.

St.

Calixtus, Mailling, Tuntenhausen; Saalbau mit Dachreiter, erbaut 1583; mit

Ausstattung.

Pope St. Callistus

Imagine that your

biography was written by an enemy of yours. And that its information was all

anyone would have not only for the rest of your life but for centuries to come.

You would never be able to refute it — and even if you could no one would

believe you because your accuser was a saint.

That is the problem we

face with Pope Callistus I who died about 222. The only story of his life we

have is from someone who hated him and what he stood for, an author identified

as Saint Hippolytus, a rival candidate for the chair of Peter. What had made

Hippolytus so angry? Hippolytus was very strict and rigid in his adherence to

rules and regulations. The early Church had been very rough on those who

committed sins of adultery, murder, and fornication. Hippolytus was enraged by

the mercy that Callistus showed to these repentant sinners, allowing them back

into communion of the Church after they had performed public penance.

Callistus’ mercy was also matched by his desire for equality among Church

members, manifested by his acceptance of marriages between free people and

slaves. Hippolytus saw all of this as a degradation of the Church, a submission

to lust and licentiousness that reflected not mercy and holiness in Callistus

but perversion and fraud.

Trying to weed out the

venom to find the facts of Callistus’ life in Hippolytus’ account, we learn

that Callistus himself was a slave (something that probably did not endear him

to class-conscious Hippolytus). His master, Carporphorus made him manager of a

bank in the Publica Piscina sector of Rome where Callistus took in the money of

other Christians. The bank failed — according to Hippolytus because Callistus

spent the money on his own pleasure-seeking. However, it seems unlikely that

Carporphorus would trust his good name and his fellow Christians’ savings to

someone that unreliable.

Whatever the reason,

Callistus fled the city by ship in order to escape punishment. When his master

caught up with him, Callistus jumped into the sea (according to Hippolytus, in

order to commit suicide). After Callistus was rescued he was brought back to

Rome, put on trial, and sentenced to a cruel punishment — forced labor on the

treadmill. Carporphorus took pity on his former slave and manager and Callistus

won his release by convincing him he could get some of the money back from

investors. (This seems to indicate, in spite of Hippolytus’ statements, that

the money was not squandered but lent or invested unwisely.) Callistus’ methods

had not improved with desperation and when he disrupted a synagogue by shouting

for money, he was arrested and sentenced again.

This time he was sent to

the mines. Other Christians who had been sentenced there because of their

religion were released by negotiations between the emperor and the Pope (with

the help of the emperor’s mistress who was friendly toward Christians).

Callistus accidentally wound up on the same list with the persecuted brothers

and sisters. (Hippolytus reports that this was through extortion and conniving

on Callistus’ part.) Apparently, everyone, including the Pope, realized

Callistus did not deserve his new freedom but unwilling to carry the case

further the Pope gave Callistus an income and situation — away from Rome. (Once

again, this is a point for suspecting Hippolytus’ account. If Callistus was so

despicable and untrustworthy why provide him with an income and a situation?

Leaving him free out of pity is one thing, but giving money to a convicted

criminal and slave is another. There must have been more to the story.)

About nine or ten years

later, the new pope Zephyrinus recalled Callistus to Rome. Zephyrinus was good-hearted

and well-meaning but had no understanding of theology. This was disastrous in a

time when heretical beliefs were springing up everywhere. One minute Zephyrinus

would endorse a belief he thought orthodox and the next he would embrace the

opposite statement. Callistus soon made his value known, guiding Zephyrinus

through theology to what he saw as orthodoxy. (Needless to say it was not what

Hippolytus felt was orthodox enough.) To a certain extent, according to

Hippolytus, Callistus was the power behind the Church before he even assumed

the bishopric of Rome.

When Zephyrinus died in

219, Callistus was proclaimed pope over the protests of his rival candidate

Hippolytus. He seemed to have as strong a hatred of heresy as Hippolytus,

however, because he banished one of the heretics named Sabellius.

Callistus came to power

during a crucial time of the Church. Was it going to hang on to the rigid rules

of previous years and limit itself to those who were already saints or was it

going to embrace sinners as Christ commanded? Was its mission only to a few

holy ones or to the whole world, to the healthy or to the sick? We can

understand Hippolytus’ fear — that hypocritical penitents would use the Church

and weaken it in the time when they faced persecution. But Callistus chose to

trust God’s mercy and love and opened the doors. By choosing Christ’s mission,

he chose to spread the Gospel to all.

Pope Callistus is listed

as a martyr but we have no record of how he was martyred or by whom. There were

no official persecutions at the time, but he may well have been killed in riots

against Christians.

As sad as it is to

realize that the only story we have of his life is by an enemy, it is glorious

to see in it the fact that the Church is large enough not only to embrace

sinners and saints, but to proclaim two people saints who hold such wildly

opposing views and to elect a slave and an alleged ex-convict to guide the

whole Church. There’s hope for all of us then!

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/pope-saint-callistus/

Transept

nord de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims

(Marne, France), statue de Calixte Ier sur le portail des Saints

Northern transept of Our Lady cathedral of Reims (Marne, France), statue of Pope Callistus Ist on the Saints portal

Transept

nord de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims

(Marne, France), statue de Calixte Ier sur le portail des Saints

Northern transept of Our Lady cathedral of Reims (Marne, France), statue of Pope Callistus Ist on the Saints portal

Transept

nord de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims

(Marne, France), statue de Calixte Ier sur le portail des Saints

Northern

transept of Our Lady cathedral of Reims (Marne, France), statue of Pope

Callistus Ist on the Saints portal

October 14

St. Calixtus, or

Callistus, Pope and Martyr

See Tillem. t. 2, from

St. Optatus, St. Austin, and the Pontificals. Also Hist. des Emper. Moret,

named by Benedict XIV. canon of St. Calixtus’s church of St. Mary beyond the

Tiber, l. de S. Callisto ejusque Ecclesia S. Mariæ Transtyberinæ, Romæ, 1753, folio,

and Sandini, Vit. Pontif. p. 43

THE NAME of St.

Callistus 1 is

rendered famous by the ancient cemetery which he beautified, and which, for the

great number of holy martyrs whose bodies were there deposited, was the most

celebrated of all those about Rome. 2 He

was a Roman by birth, succeeded St. Zephirin in the pontificate in 217 or 218,

on the 2nd of August, and governed the church five years and two months,

according to the true reading of the most ancient pontifical, compiled from the

registers of the Roman church, as Henschenius, Papebroke, and Moret show, though

Tillemont and Orsi give him only four years and some months. Antoninus

Caracalla, who had been liberal to his soldiers, but the most barbarous

murderer and oppressor of the people, having been massacred by a conspiracy,

raised by the contrivance of Macrinus, on the 8th of April, 217, who assumed

the purple, the emperor was threatened on every side with commotions. Macrinus

bestowed on infamous pleasures at Antioch that time which he owed to his own

safety, and to the tranquillity of the state, and gave an opportunity to a

woman to overturn his empire. This was Julia Mœsa, sister to Caracalla’s

mother, who had two daughters, Sohemis and Julia Mammæa. The latter was mother

of Alexander Severus, the former of Bassianus, who, being priest of the sun,

called by the Syrians Elagabel, at Emesa, in Phœnicia, was surnamed

Heliogabalus. Mœsa, being rich and liberal, prevailed for money with the army

in Syria to proclaim him emperor; and Macrinus, quitting Antioch, was defeated

and slain in Bithynia in 219, after he had reigned a year and two months,

wanting three days. Heliogabalus, for his unnatural lusts, enormous prodigality

and gluttony, and mad pride and vanity, was one of the most filthy monsters and

detestable tyrants that Rome ever produced. He reigned only three years, nine

months, and four days, being assassinated on the 11th of March, 222, by the

soldiers, together with his mother and favourites. Though he would be adored

with his new idol, the sun, and, in the extravagance of his folly and vices,

surpassed, if possible, Caligula himself, yet he never persecuted the

Christians. His cousin-german and successor, Alexander, surnamed Severus, was,

for his clemency, modesty, sweetness, and prudence, one of the best of princes.

He discharged the officers of his predecessor, reduced the soldiers to their

duty, and kept them in awe by regular pay. He suffered no places to be bought,

saying: “He that buys must sell.” Two maxims which he learned of the Christians

were the rules by which he endeavoured to square his conduct. The first was:

“Do to all men as you would have others do to you.” The second: “That all

places of command are to be bestowed on those who are the best qualified for

them;” though he left the choice of the magistrates chiefly to the people,

whose lives and fortunes depend on them. He had in his private chapel the

images of Christ, Abraham, Apollonius of Tyana, and Orpheus, and learned of his

mother, Mammæa, to have a great esteem for the Christians. It reflects great

honour on our pope, that this wise emperor used always to admire with what

caution and solicitude the choice was made of persons that were promoted to the

priesthood among the Christians, whose example he often proposed to his

officers and to the people, to be imitated in the election of civil

magistrates. 3 It

was in his peaceable reign that the Christians first began to build churches,

which were demolished in the succeeding persecution. Lampridius, this emperor’s

historian, tells us, that a certain idolater, putting in a claim to an oratory

of the Christians, which he wanted to make an eating-house of, the emperor

adjudged the house to the bishop of Rome, saying, it were better it should

serve in any kind to the divine worship than to gluttony, in being made a

cook’s shop. To the debaucheries of Heliogabalus St. Callistus opposed fasting

and tears, and he every way promoted exceedingly true religion and virtue. His

apostolic labours were recompensed with the crown of martyrdom on the 12th of

October, 222. His feast is marked on this day in the ancient Martyrology of

Lucca. The Liberian Calendar places him in the list of martyrs, and testifies

that he was buried on the 14th of this month in the cemetery of

Calepodius, 4 on

the Aurelian way, three miles from Rome. The pontificals ascribe to him a

decree appointing the four fasts called Ember-days; which is confirmed by

ancient Sacramentaries, and other monuments quoted by Moretti. 5 He

also decreed, that ordinations should be held in each of the Ember weeks. 6 He

founded the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary beyond the Tiber. In the calendar

published by Fronto le Duc he is styled a confessor; but we find other martyrs

sometimes called confessors. Alexander himself never persecuted the Christians;

but the eminent lawyers of that time, whom this prince employed in the

principal magistracies, and whose decisions are preserved in Justinian’s

Digestum, as Ulpian, Paul, Sabinus, and others, are known to have been great

enemies to the faith, which they considered as an innovation in the

commonwealth. Lactantius informs us 7 that

Ulpian bore it so implacable a hatred, that, in a work where he treated on the

office of a proconsul, he made a collection of all the edicts and laws which

had been made in all the foregoing reigns against the Christians, to incite the

governors to oppress them in their provinces. Being himself prefect of the

prætorium, he would not fail to make use of the power which his office gave

him, when upon complaints he found a favourable opportunity. Hence several

martyrs suffered in the reign of Alexander. If St. Callistus was thrown into a

pit, as his Acts relate, it seems probable that he was put to death in some

popular tumult. Dion 8 mentions

several such commotions under this prince, in one of which the prætorian guards

murdered Ulpian, their own prefect. Pope Paul I., and his successor, seeing the

cemeteries without walls, and neglected after the devastations of the

barbarians, withdrew from thence the bodies of the most illustrious martyrs,

and had them carried to the principal churches of the city. 9 Those

of SS. Callistus and Calepodius were translated to the church of St. Mary, beyond

the Tiber. Count Everard, lord of Cisoin or Chisoing, four leagues from

Tournay, obtained of Leo IV., about the year 854, the body of St. Callistus,

pope and martyr, which he placed in the abbey of Canon Regulars that he had

founded at Cisoin fourteen years before; the church of which place was on this

account dedicated in honour of St. Callistus. These circumstances are mentioned

by Fulco, archbishop of Rheims, in a letter which he wrote to Pope Formosus in

890. 10 The

relics were removed soon after to Rheims for fear of the Normans, and never

restored to the abbey of Cisoin. They remain behind the altar of our Lady at

Rheims. Some of the relics, however, of this pope are kept with those of St.

Calepodius, martyr, in the church of St. Mary Trastevere at Rome. 11 A

portion was formerly possessed at Glastenbury. 12 Among

the sacred edifices which, upon the first transient glimpse of favour, or at

least tranquillity that the church enjoyed at Rome, this holy pope erected, the

most celebrated was the cemetery which he enlarged and adorned on the Appian

road, the entrance of which is at St. Sebastian’s, a monastery founded by

Nicholas I., now inhabited by reformed Cistercian monks. In it the bodies of

SS. Peter and Paul lay for some time, according to Anastasius, who says that

the devout lady Lucina buried St. Cornelius in her own farm near this place;

whence it for some time took her name, though she is not to be confounded with

Lucina who buried St. Paul’s body on the Ostian way, and built a famous

cemetery on the Aurelian way. Among many thousand martyrs deposited in this

place were St. Sebastian, whom the lady Lucina interred, St. Cecily, and

several whose tombs Pope Damasus adorned with verses.

In the assured faith of

the resurrection of the flesh, the saints, in all ages down from Adam, were

careful to treat their dead with religious respect, and to give them a modest

and decent burial. The commendations which our Lord bestowed on the woman who

poured precious ointments upon him a little before his death, and the devotion

of those pious persons who took so much care of our Lord’s funeral, recommended

this office of charity; and the practice of the primitive Christians in this

respect was most remarkable. Julian the Apostate, writing to a chief priest of

the idolaters, desires him to observe three things, by which he thought Atheism

(so he called Christianity) had gained most upon the world, namely, “Their

kindness and charity to strangers, their care for the burial of their dead, and

the gravity of their carriage. 13 Their

care of their dead consisted not in any extravagant pomp, 14 in

which the pagans far outdid them, 15 but

in a modest religious gravity and respect which was most pathetically expressive

of their firm hope of a future resurrection, in which they regarded the mortal

remains of their dead as precious in the eyes of God, who watches over them,

regarding them as the apple of his eye, to be raised one day in the brightest

glory, and made shining lustres in the heavenly Jerusalem.”

Note

1. This name in several later MSS. is written Calixtus: but truly in

all ancient MSS. Callistus, a name which we frequently meet with among the

ancient Romans, both Christians and Heathens, even of the Augustan age. (See

the inscriptions collected by Gruter, p. 634; Blanchini, Inscrip. 36, 191, 217,

&c.; Boldetti, l. 2, c. 18, &c.; Muratori, Thesaurus, &c. The name

in Greek signifies The best, most excellent, or most beautiful. [back]

Note

2. The primitive Christians were solicitous not to bury their dead

among infidels, as appears from Gamaliel’s care in this respect, mentioned by

Lucian, in his account of the discovery of St. Stephen’s relics: also from St.

Cyprian, who makes it a crime in Martialis, a Spanish bishop, to have buried

children in profane sepulchres, and mingled with strangers. (ep. 68.) See this

point proved by Mabillon, (Diss. sur les Saints Inconnus, § 2, p. 9,) Boldetti,

(l. 1, c. 10,) John de Vitâ, (Thesaur. Antiquit. Benevent. Diss. 11, an. 1754,)

Bottario, &c. That the catacombs were the cemeteries of the Christians is

clear from the testimony of all antiquity, and from the monuments of

Christianity with which they are every where filled. Misson, (Travels through

Italy, t. 2, ep. 28,) Burnet, (Letters on Italy,) James Basnage, (Hist. Eccl.

l. 18, c. 5, 6,) Fabricius, (Bibl. Antiqu. c. 23, n. 10, p. 1035,) suspect

heathens to have been often buried in these catacombs. Burnet will have them to

have been the Puticuli, or burial place of slaves, and the poorest people,

mentioned by Horace, (Satyr. 8, et Epod. l. 5, et ult.) Varro, Festus, Sextus,

Pompeïus, Aulus Gellius, &c. But all these authors mention the Puticuli to

have been without the Esquiline-gate only, where the ashes, or sometimes (if

criminals, slaves, or other poor persons who died without friends or money to

procure a pile to burn them, or so much as an earthen urn to contain their

ashes) the bodies of such persons were thrown confusedly on heaps in pits,

whence the name Puticuli. There were probably other such pits in places

assigned near other highways, which were called Columellæ, Saxa, and Ampullæ.

See Gutherius (De Jure Manium, l. 2,) and Bergier. (Hist. des. Chem. Milit. l.

2, c. 38, et ap. Grævium, t. 10.) The catacombs, on the contrary, are dug on

all sides of the city, in a very regular manner, and the bodies of the dead are

ranged in them in separate caverns on each hand, the caverns being shut up with

brick or mortar. By the law of the twenty-two tables mentioned by Cicero, (De

Leg. l. 2, c. 23,) it was forbidden to bury or burn any dead corpse within the

walls of towns. At Athens, by the laws of Solon, and in the rest of Greece, the

same custom prevailed, upon motives partly of wholesomeness, as St. Isidore

observes, (l. Etymol.) partly of superstition. (See the learned canon John de

Vitâ loc. cit. c. 11.) At Rome, vestal virgins, and sometimes emperors were

excepted from this law, and allowed burial within the walls. Every one knows

that on Trajan’s pillar (that finished and most admirable monument) the ashes

of that emperor were placed in a golden urn: which having been

long before plundered, Sixtus V. placed there a statue of St. Peter, as he did

that of St. Paul on Antoninus’s pillar; though the workmanship of this falls

far short of the former. The heathen Romans burned the corpses of their dead,

and placed the urns in which the ashes were contained usually on the sides of

the highways. Cicero mentions (l. 1, Tuscul. Quæst. c. 7,) those of the

Scipios, the Servilii, and the Metelli on the Appian road. See Montfaucon.

(Antiqu. t. 9, 10, et Suppl. t. 5, et Musæum Florent.) And on the ancient

consular roads about Rome, Ficoroni, (Vestigia di Roma antica, c. 2, p. 6,) the