Saint Serge de Radonège

Ermite, fondateur du

monastère de la Trinité-Saint-Serge (+ 1392)

Né à Rostov au nord de

Moscou, le jeune Barthélémy (le futur moine Serge) émigre à Radonège avec les

siens, fuyant l'avance des Tatares. Le garçon, peu doué pour les études, ne

rêve que de vie monastique. A la mort de ses parents, il se retire avec son frère

aîné dans la forêt pour y vivre en ermite au milieu des loups et des ours. Les

deux frères bâtissent une chapelle dédiée à la Sainte Trinité. Avec le temps,

l'ermitage devient un monastère (le monastère de la Sainte Trinité), peuplé de

moines vivant une pauvreté radicale dans une grande liberté. Le patriarche de

Constantinople dont dépend alors la Russie, impose à Serge l'adoption de la

Règle cénobitique du Studion, qui instaure entre les moines une vie commune

plus stricte. Serge se soumet à regret. Il ne reste pas confiné dans son

monastère. Il se sent responsable de son pays en pleine ébullition politique.

Les princes sollicitent ses conseils et ses prières. En 1380, il bénit le

grand-prince Dimitri de Moscou avant la bataille de Koulikovo qui inaugure la

fin du joug mongol en Russie. On pourrait la comparer en France à la bataille

de Poitiers sur les Musulmans. Il mène encore des missions de conciliation

entre les princes russes et fonde de nombreux autres monastères. Le monastère

de la Trinité Saint Serge, à 70 km de Moscou, resta, même aux jours les plus

sombres du communisme, un grand pèlerinage et l'un des centres théologiques et

spirituels de l'Église Russe.

Il fut canonisé en 1452.

Au monastère de la Sainte

Trinité, aux environs de Moscou, en 1392, saint Serge de Radonez, qui vécut

d’abord en ermite dans des forêts sauvages, puis pratiqua la vie cénobitique et

la propagea, une fois élu higoumène, homme plein de douceur, conseiller des

princes et consolateur des fidèles.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1447/Saint-Serge-de-Radonege.html

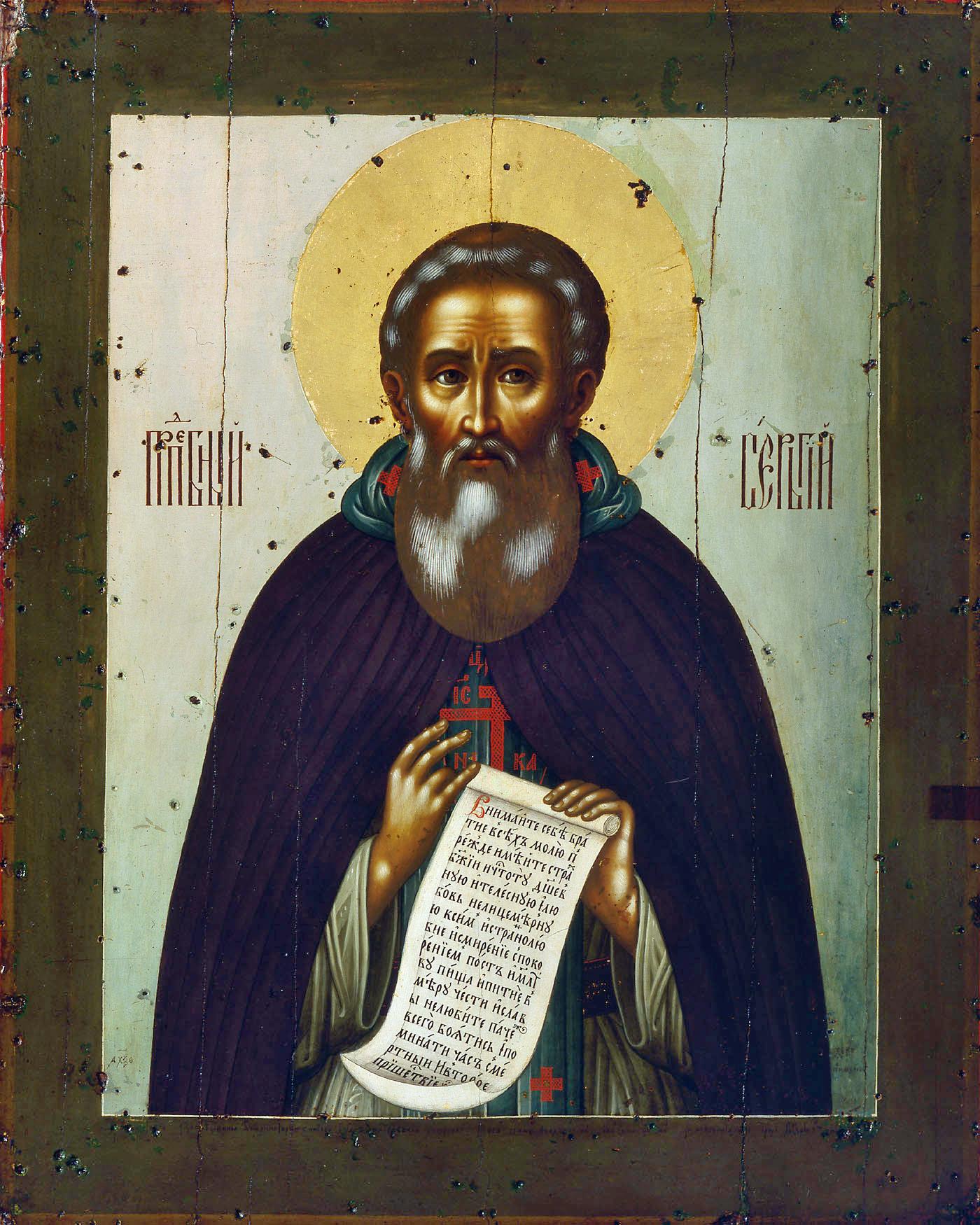

Simon

Ushakov (1626–1686). Икона Симона Ушакова - Сергий

Радонежский, 1669 год

La Vie du Saint Père Théophore Serge de Radonège,

Thaumaturge et Protecteur de la Russie

Saint Serge naquit en 1313 à Rostov. Ses parents,

Cyrille et Marie, lui donnèrent au baptême le nom de Barthélémy. Dès le sein de

sa mère, Dieu laissa prévoir la gloire future de son serviteur. C'est ainsi

qu'une fois, au cours de la liturgie avant la lecture de l'Évangile, l'enfant

se mit à crier dans le sein de sa mère, si fort que sa voix fut entendue par

d'autres. Au moment de l'hymne des chérubins, la voix de l'enfant se mit encore

à retentir, ce qui effraya Marie. Lorsque le prêtre prononça l'ecphonèse : «Ce

qui est saint aux saints !», l'enfant poussa un cri pour la troisième fois, et

sa mère commença à pleurer. Ceux qui étaient présents à la liturgie

souhaitaient voir l'enfant; mais la mère fut contrainte de dire qu'il criait

non pas sur ses bras, mais dans son sein. Après cet événement inhabituel,

Marie, pendant toute la période de sa grossesse, ne mangeait ni viande ni lait

ni poisson; elle se nourrissait exclusivement de pain et d'eau, et vaquait à la

prière. Lorsqu'il eut sept ans, on envoya l'enfant étudier. Or, contrairement à

ses frères Etienne et Pierre qui apprenaient bien, Barthélémy éprouvait des

difficultés. Le maître le punissait, ses camarades se moquaient de lui, ses

parents le réprimandaient; mais Barthélémy, malgré toute sa bonne volonté, ne

parvenait pas à apprendre. C'est alors que se produisit le même phénomène

qu'avec Saül. Un jour, alors que son père l'avait envoyé au champ chercher des

chevaux, Barthélémy aperçut un moine âgé sous un chêne, qui priait en versant

des larmes. Le jeune garçon s'approcha doucement, attendant la fin de la prière

du staretz, qui lui dit: «Que te faut-il, mon enfant?» Barthélémy répondit: «Je

ne puis apprendre malgré mes efforts. Prie Dieu pour moi, saint père, pour que

je puisse apprendre les lettres». Le staretz, en prononçant une prière, donna

un morceau de prosphore à l'enfant et lui dit: «Ne t'afflige point. A partir de

ce jour, le Seigneur te donnera la compréhension des lettres!» Alors que le

staretz voulait sortir, Barthélémy tomba à ses pieds et lui demanda de visiter

la maison de ses parents. Il ajouta: «Mes parents aiment fort les personnes

semblables à toi, Père». L'Ancien, en souriant, se rendit à la maison des

parents de l'enfant, qui le reçurent avec grande considération. Ils le prièrent

de partager leur repas, puis le staretz entra dans la chapelle familiale.

Prenant l'enfant avec lui, le vieux moine lui ordonna de lire les heures.

Cependant, Barthélémy, troublé, répondit qu'il ne pouvait pas lire. Le staretz

réintima l'ordre, et l'enfant, ayant pris sa bénédiction, commença à lire le

psautier correctement et distinctement, à l'étonnement général. A table, les

parents racontèrent au moine ce qui s'était produit à l'église quand l'enfant

était encore dans le sein de sa mère. Le staretz, avant de se séparer d'eux,

dit ces paroles énigmatiques: «Cet enfant va devenir la demeure de la Sainte

Trinité, et amènera une multitude à la compréhension de Sa volonté». Après

cela, Barthélémy commença à fréquenter avec ardeur l'église et à lire la sainte Écriture. Après un certain temps, alors qu'il était âgé de douze ans, il se mit

à observer une stricte tempérance, s'abstenant de toute nourriture le mercredi

et le vendredi et se contentant, les autres jours, de pain sec et d'eau. En

raison de certains malheurs qui le frappèrent à Rostov, le père de Barthélémy,

Cyrille, partit à Radonège avec sa famille. Là, Barthélémy continua son ascèse.

Alors que ses deux frères s'étaient mariés, il demanda à ses parents la

permission de s'engager dans la vie monastique. Ceux-ci le prièrent d'ajourner

son désir jusqu'à leur mort. Cependant, peu de temps après, ils entrèrent

eux-mêmes au monastère et décédèrent bientôt. Pendant quarante jours,

Barthélémy pria sur leur tombe, nourrit les pauvres et fit servir des offices

de requiem. Ensuite, il fit don de ses biens à son frère cadet Pierre et décida

d'accomplir son désir. Son frère aîné Etienne, dont la femme était décédée,

effectua sa profession monastique au monastère de Khotov, où ses parents

étaient enterrés. Barthélémy, qui souhaitait une profonde solitude, convainquit

Etienne de rechercher un endroit qui conviendrait mieux à la vie ascétique. Ils

cheminèrent longtemps dans les forêts, puis trouvèrent un endroit approvisionné

en eau et éloigné des chemins battus, à dix verstes de Radonège et de Khotov.

Ils bâtirent une cellule avec une petite église. Le frère cadet, obéissant à

l'aîné, demanda en quel nom serait construite l'église. Barthélémy, se

rappelant les paroles du staretz, répondit qu'il convenait de dédier l'église à

la Sainte Trinité. Le frère cadet dit alors que telle était aussi sa pensée.

L'église fut consacrée avec la bénédiction du métropolite Théognoste. Ayant

demandé à l'higoumène Métrophane de venir, Barthélémy reçut la tonsure

monastique avec le nom de Serge. Il avait alors vingt-quatre ans (1337).

Etienne, quant à lui, parti peu de temps après au monastère de la Theophanie à

Moscou.

Et voici que Serge se trouva seul dans cette forêt, où

les loups hurlaient près de sa cellule. Les ours aussi s'approchaient du lieu

où vivait le saint. Une fois, Serge s'aperçut qu'un ours n'était pas tant

féroce qu'affamé, et il commença à éprouver de la pitié pour cet animal, puis

lui donna de la nourriture. Le fauve s'éprit du père et vint souvent recevoir de

lui sa pitance. Le saint la lui donnait à chaque fois, partageait son dernier

morceau de pain avec cet animal, et allait même jusqu'à se priver de nourriture

pour lui. Saint Serge resta seul pendant trois ans jusqu'à ce que des zélateurs

de la piété commencent à lui demander de vivre sous sa direction spirituelle.

Peu à peu, douze frères se rassemblèrent, et chacun d'entre eux construisit sa

propre cellule. L'office de minuit, les matines, les heures, les vêpres et les

complies étaient quotidiennement célébrées à l'église. Pour la célébration de

la liturgie, les frères appelaient un prêtre de l'extérieur, car il n'y en

avait pas encore parmi eux. Enfin, l'higoumène Métrophane, qui avait tonsuré

Serge, vint vivre avec eux. Mais, peu de temps après, cet ancien mourut. Quant

à Serge, il ne voulait pas, par humilité, devenir higoumène. Les frères se

réunirent alors, vinrent voir le saint et lui dirent: «Père, nous ne pouvons

vivre sans higoumène, et nous souhaitons que ce soit toi qui remplisses cette

fonction. Ainsi, lorsque nous viendrons te révéler nos péchés, nous recevrons

des enseignements et l'absolution. Il convient également que la liturgie soit

célébrée et que nous recevions les saints Mystères de tes pures mains».

Cependant Serge refusa et, quelques jours après, la communauté se réunit de

nouveau chez le saint, en le priant d'accepter la charge d'higoumène. «Il ne

m'appartient pas d'accomplir le ministère angélique; il m'appartient de pleurer

mes péchés», répondit-il. Les frères pleurèrent et dirent enfin: «Si tu ne veux

pas prendre soin de nos âmes, nous serons contraints de quitter ce lieu, nous

errerons alors comme des brebis égarées, et tu devras en répondre devant Dieu.»

«Je préfère me soumettre que de commander, dit Serge; mais, craignant le jugement

de Dieu, je laisse ce problème à la volonté du Seigneur». Prenant avec lui deux

des moines les plus âgés, il se rendit à Péréïaslavl, chez Athanase, l'évêque

de Volynie, auquel S. Alexis, alors à Constantinople, avait remis les affaires

du diocèse métropolitain.

En 1354, Serge fut ordonné prêtre et élevé au rang

d'higoumène par l'évêque Athanase. Il célébrait quotidiennement la sainte

liturgie, et arrivait le premier à l'église pour chaque office. Il fabriquait

lui-même les cierges et les prosphores, ne permettant jamais à quiconque de

participer à cette dernière tâche. Pendant trois ans, le nombre des moines

resta identique, le premier qui fit augmenter ce nombre fut l'archimandrite

Simon de Smolensk, qui préférait obéir à S. Serge plutôt que commander ailleurs.

Le soir après les complies, et sauf en cas de besoin

urgent, nul n'avait l'autorisation de se rendre dans la cellule d'un autre

moine. Car les heures de la nuit devaient être réservées à Dieu seul. Le reste

du temps, ils restaient dans le silence à alterner la prière et le travail

manuel. A la fin de la prière que les frères devaient accomplir dans leur

cellule, le saint faisait secrètement le tour de celles-ci. S'il entendait de

vaines conversations ou des rires, il frappait à la fenêtre pour les faire

cesser et s'en allait tout triste. Le matin, il réunissait les fautifs, et «de

loin», à l'aide de paraboles et sur un ton humble et doux, il les instruisait.

Il n'employait une sévérité toute mesurée que pour ceux qui refusaient de faire

pénitence et persistaient dans leurs fautes. Il aimait tant la pauvreté qu'il

institua comme règle stricte de ne jamais faire de quête au profit du

monastère: quels que soient ses besoins. Le dépouillement était extrême dans la

communauté: On s'éclairait avec des tisons pour l'office, et les livres étaient

faits en écorce de bouleau. Un jour, le monastère se trouva réduit à une si

extrême misère qu'on ne pouvait plus y trouver ni pain ni eau. Après avoir

passé trois jours sans nourriture, Serge se rendit chez le frère Daniel et lui

dit: «J'ai entendu que tu voudrais construire une entrée devant ta cellule. Je

te la construirai afin que mes mains ne restent pas oisives. Cela ne te coûtera

pas cher, je veux du pain avarié et tu en as.» Daniel lui apporta donc des morceaux

de pain moisis qu'il avait chez lui. «Garde-les, lui dit le saint, jusqu'à la

neuvième heure; je ne prends pas de salaire avant d'avoir travaillé». Ayant

achevé son travail, Serge pria, bénit le pain, en mangea, puis but de l'eau, ce

qui constitua son repas. En raison de l'absence de nourriture, les frères

commencèrent à manifester leur mécontentement: «Nous mourons de faim», dirent

les faibles, «et tu ne permets pas de demander l'aumône. Demain, nous partirons

d'ici, chacun de son côté, et nous ne reviendrons plus ! » Le saint les

persuada alors de ne pas affaiblir leur espoir en Dieu. «Je crois, dit-il, que

Dieu ne délaissera pas les habitants de ce lieu». A ce moment, on entendit

quelqu'un frapper à la porte. Le portier vit que l'on avait apporté beaucoup de

pains. Il accourut tout joyeux, et dit à l'higoumène: «Père, on nous a apporté

beaucoup de pains. Donne-nous ta bénédiction afin que nous les prenions! » Le

saint ordonna de laisser entrer les bienfaiteurs, et convia tous les frères à

table, ayant au préalable célébré un office d'action de grâces. «Où sont ceux

qui nous ont apporté ces dons ?» demanda-t-il. «Nous les avons invites à table

et leur avons demandé qui les avait envoyés», répondit le moine, «et ils nous

dirent que c'était quelqu'un qui aime le Christ, qui les avait envoyés; mais

que, ayant une autre tâche accomplir, ils devaient partir».

Une autre fois, le saint, tard dans la soirée, priait

pour les frères de son monastère. Soudain, il entendit une voix lui dire:

«Serge! » Ayant terminé une prière, il ouvrit la fenêtre et aperçut une lumière

inhabituelle qui descendait du ciel, et la voix continua: «Serge ! Le Seigneur

a entendu la prière pour tes enfants; vois quelle multitude s'est rassemblée

autour de toi au nom de la Sainte Trinité». Alors, le saint vit une multitude

d'oiseaux merveilleux, volant non seulement dans le monastère, mais également

tout autour. «Ainsi, poursuivit la voix, se multipliera le nombre de tes

disciples et il ne te manquera point de successeurs pour marcher sur tes

traces».

Peu de temps après, le patriarche Philothée fit

parvenir au saint une croix et encore d'autres présents avec une lettre, dont

voici le contenu : «Par la Miséricorde Divine, l'archevêque de Constantinople,

patriarche œcuménique, Philothée, à Serge, fils dans le Saint-Esprit et

concélébrant de notre humble personne. Que la grâce, la paix et notre

bénédiction soient avec vous tous! Nous avons entendu parler de ta vie

vertueuse, nous l'approuvons, et nous en glorifions Dieu. Mais il te manque une

chose: la vie commune (cénobitique). Tu sais, Père très semblable au Christ,

que le parent de Dieu, le prophète David, qui saisissait tout par son esprit,

loua la vie commune. «Qu'y a-t-il de meilleur et de plus beau pour des frères

gue de vivre ensemble» ? (Ps 132). Pour cela, je vais vous donner un conseil

utile: instituez le cénobitisme. Que la miséricorde de Dieu et notre

bénédiction soient avec vous! » Suivant le conseil du patriarche, le saint,

avec la bénédiction du métropolite Alexis, introduisit la vie commune intégrale

dans son monastère. Il construisit les bâtiments nécessaires, définit les

devoirs propres à cette vie, et ordonna que toute chose soit commune,

interdisant d'avoir sa propriété ou d'appeler quelque chose «sien». Le nombre

des disciples s'accrut alors et l'abondance régna au monastère. On introduisit

l'hospitalité, on nourrit les pauvres et on donna l'aumône à ceux qui le

demandaient. Saint Serge s'était soumis à ce conseil du patriarche par esprit

d'obéissance. Bien qu'il demeurât amant de la solitude, il accepta d'assumer

cette forme plus rigide de direction, sans cesser pourtant d'être un père et un

éducateur plutôt qu'un administrateur. Mais il devait bientôt subir de cruelles

épreuves. Un samedi, le saint se trouvait dans le sanctuaire, célébrant les

vêpres. Son frère, revenu au monastère, demanda au canonarque: «Qui t'a donné

ce livre ?» «L'higoumène», répondit celui-ci. «Qui est higoumène ici ?»

répondit à son tour Etienne, avec colère. «N'ai-je pas fondé ce lieu en premier

?» A ceci, il ajouta de violentes paroles. Le saint entendait tout cela dans le

sanctuaire, et il comprit que cette manifestation de mécontentement était due

en fait au nouvel ordre qui régnait dans le monastère. Mécontents du

cénobitisme, certains quittèrent en secret le monastère, et d'autres

souhaitaient ne plus avoir Serge pour higoumène. Le saint, laissant ceux qui

voulaient vivre selon leur volonté face à leur conscience, ne rentra même pas

dans sa cellule, mais s'éloigna du monastère. Les meilleurs moines étaient inquiets,

mais pensaient encore que Serge reviendrait. Toutefois, leur attente fut déçue.

Le saint s'installa à Kirjatch. Sur la demande de certains, saint Alexis

dépêcha une délégation auprès de saint Serge, afin qu'il revînt au monastère où

il était si utile. Mais saint Alexis, sentant sa mort prochaine, souhaitait

trouver en la personne de Serge son successeur. Il le fit venir chez, lui fit

cadeau de sa croix épiscopale. Mais saint Serge, par humilité, la refusa en

disant: «Pardonne-moi, Seigneur, mais depuis mon enfance je n'ai jamais porté

d'or et maintenant, je souhaite d'autant plus rester dans le dépouillement».

«Je le sais, bien-aimé, mais accepte par obéissance!» répondit Alexis. Ce

faisant, il lui passa la croix autour du cou et lui annonça qu'il le désignait

comme son successeur. «Pardonne-moi, vénéré pasteur, mais tu veux me charger

d'un fardeau qui dépasse mes forces. Tu ne trouveras pas en moi ce que tu

cherches. Je suis le plus pécheur et le pire de tous.»

Lorsque les hordes tatares déferlèrent sur la terre

russe, et alors que la population était effrayée, le grand Duc Dimitri

Ioannovitch, qui avait une grande foi en saint Serge, lui demanda s'il devait

entrer en guerre contre les impies Tatares. Le saint bénit le grand Duc pour

entrer en guerre et lui dit: «Avec l'aide de Dieu, tu seras victorieux et tu

sortiras de la bataille sain et sauf et couvert d'honneurs.». Au moment de la

bataille de Koulikovo*, le saint était en prière avec ses frères et parlait du

déroulement heureux des combats. Il citait même les noms de ceux qui tombaient,

faisant une prière pour eux. Conformément à la prédiction de saint Serge, le

grand Duc remporta la célèbre victoire de Koulikovo, qui constituait le début

de la délivrance du joug tatare.

Une nuit, alors que saint Serge chantait l'Acathiste à

la Mère de Dieu et lui adressait de ferventes prières pour le monastère devant

son icône, il s'interrompit un instant pour dire à son disciple Michée: «Sois

vigilant, mon enfant, car nous allons recevoir une visite miraculeuse!» A peine

avait-il prononcé ces paroles qu'il entendit une voix: «La Très Pure arrive! »

Il se précipita à l'entrée de sa cellule et, soudain, une lumière inhabituelle

l'entoura, plus éclatante encore que le soleil. Il vit la Très Sainte Mère de

Dieu, accompagnée des Apôtres Pierre et Jean, rayonnante d'une gloire

indescriptible. Le saint se prosterna à terre, mais la Mère de Dieu le toucha

de sa main et dit: «Ne crains point, mon élu! Je suis venue te visiter, car

j'ai entendu ta prière pour tes disciples et pour ce lieu. Dorénavant je ne

quitterai pas ton monastère, durant ta vie comme après ta mort, et je le

protégerai». Après cela, le saint resta sans sommeil toute la nuit, méditant

avec piété sur la miséricorde céleste.

Six mois avant son trépas, le saint, appelant sa

communauté, la recommanda à Nicon, et se consacra lui-même à la solitude et à

la prière. En septembre, il pressentit la maladie, appela de nouveau les frères

et leur donna à tous ses dernières instructions. Il mourut le 25 septembre 1391,

à l'âge de 78 ans.

* Bataille décisive pour la Russie, que l'on peut

comparer à la bataille de Poitiers en France.

Macaire, moine de Simonos Petras

"Le Synaxaire. Vies des Saints de l'Eglise

Orthodoxe"

Editions "To Perivoli tis Panaghias", © S. M.

Simonos Petras, Mont Athos

SOURCE : http://www.orthodoxa.org/FR/orthodoxie/synaxaire/StSergeRadonege.htm

Sergius

of Radonezh vita icon, XVII c., Yaroslavl museum

Сергий

Радонежский с житием. Школа или худ. центр: Ярославль. Середина XVII в. 176 ×

113 см. Ярославский историко-архитектурный и художественный музей заповедник,

Ярославль, Россия. Инв. И-394. http://www.icon-art.info/masterpiece.php?mst_id=1139&where=library

Saint

Serge de Radonège + 1392

Ermite, fondateur de la Laure

de la Sainte Trinité-Saint-Serge (+ 1392)

Serguiev Posad - Сергиев

Посад (appelé Zagorsk - Загорск à l'époque soviétique), à 75 km au nord de

Moscou

Ce monastère fondé dans

les années 1340 par saint Serge, eut un rayonnement exceptionnel jusqu'au XXe

siècle.

En 1920, la laure est

fermée par les bolchéviques et ne sera réouverte qu'après le IIe guerre

mondiale : « cadeau » de Staline à l'Église

Le monastère de la

Trinité Saint Serge, resta même aux jours les plus sombres du soviétisme un

grand lieu de pèlerinage et l'un des centres théologiques et spirituels de

l'Église russe.

1919 - Profanation des

reliques de saint Serge de Radonège YOU

TUBE

Né à Rostov au nord de

Moscou, le jeune Barthélémy (le futur moine Serge) émigre à Radonège avec les

siens, fuyant l'avance des Tatares. Le garçon, peu doué pour les études, ne

rêve que de vie monastique. A la mort de ses parents, il se retire avec son frère

aîné dans la forêt pour y vivre en ermite au milieu des loups et des

ours.

Les deux frères bâtissent

une chapelle dédiée à la Sainte Trinité. Avec le temps, l'ermitage devient un

monastère (le monastère de la Sainte Trinité), peuplé de moines vivant une

pauvreté radicale dans une grande liberté. Le patriarche de Constantinople dont

dépend alors la Russie, impose à Serge l'adoption de la Règle cénobitique du

Studion, qui instaure entre les moines une vie commune plus stricte. Serge se

soumet à regret. Il ne reste pas confiné dans son monastère. Il se sent

responsable de son pays en pleine ébullition politique. Les princes sollicitent

ses conseils et ses prières.

En 1380, il bénit le

grand-prince Dimitri de Moscou avant la bataille de Koulikovo qui inaugure la

fin du joug mongol en Russie. On pourrait la comparer en France à la bataille

de Poitiers sur les Musulmans. Il mène encore des missions de conciliation entre

les princes russes et fonde de nombreux autres monastères.

Il fut canonisé en

1452.

"Rencontre de

Barthélémy avec le moine", par Mikhail Nesterov (1890).

В № 82 издаваемой в

Москве газеты Российской коммунистической партии "Правда" от 16

апреля 1919 года приведён протокол вскрытия мощей Сергия Радонежского .

Произошло это кощунственное святотатство 11 апреля 1919 года, а статья в

"Правде"называлась "Святые чудеса".

Протокол этот, надо

заметить, судя по содержанию носит официальный характер и начинается с

перечисления всех присутствующих при этом лиц. Всё это большевики,

представители партии коммунистов, члены "технической комиссии по вскрытию

мощей", представители волостей, уездов и врачей (доктора медицины

Ю.А.Гвоздикова и доктора И.П. Попова) представителей духовенства и пр.

Ровно в 20час.50 мин. По

приказанию председателя Сергиевского исполкома - финна Ванханена, один из

иеромонахов (Иона) и игумен Лавры, вынуждены были под дулами пистолетов

приступить к кощунственному акту вскрытия мощей одного из наиболее чтимых

святых угодников Православной церкви. Им пришлось в течении двух часов

разбирать покровы и мощи Св.Сергия, который более пятисот лет тому назад

благословлял русский народ на борьбу с татарским игом во имя спасения и

объединения России. У стен монастыря собралась огромная толпа, а в самом храме

народ спешил в последний раз приложиться к святым мощам, слышались возгласы

"Мы веровали и будем веровать!".

В это время в пределе

храма устанавливались камеры кинематографа, стали щёлкать фотоаппараты и не

смотря на протесты народа, кощунственный акт вскрытия мощей был приведён в

исполнение.

В 22час. 30мин. позорное

дело было закончено, а протокол был скреплён 50 подписями. В нём есть отметка,

что вскрытие сопровождалось киносъёмкой.

Мы приводим только один

случай подобного вандализма и надругания над святыней, но их множество. В то же

время были вскрыты мощи преп. Тихона Задонского в Ельце и Митрофания

Воронежского при большом скоплении народа. Красноармейцы эти мощи надевали на

штыки, производили кощунства и надругательства. В Ярославле были вскрыты мощи

благоверных князей Василия и Константина, а в Спасском монастыре князя Фёдора и

его чад Давида и Константина. Всем руководили местные комиссары. Советские

"Известия"пишут об извлечении мощей в соборе св.Софии в Новгороде.

Священников, отказывавшихся от заявлений, что "якобы кости сгнили",

большевики расстреливали на месте.

Rédigé par Parlons

d'orthodoxie le 8 Octobre 2013 à 05:30

SOURCE : http://www.egliserusse.eu/blogdiscussion/Saint-Serge-de-Radonege-1392_a304.html

Стеллецкий

Дмитрий Семенович. Икона Святого Сергия

Dmitry

Stelletski Icon of Sergius of Radonezh

Boris

ZAÏTSEV : Saint Serge de Radonège

Bibliographie des

œuvres de Boris Zaïtsev et en russe Boris

ZAÏTZEFF

Plus de six cents ans se sont écoulés depuis la naissance de saint Serge1, plus

de cinq cents depuis sa mort. Sa vie calme, sainte et pure, a duré près d’un

siècle. Le modeste adolescent, qui s’appelait d’abord Barthélemy et qui prit

plus tard le nom de Serge, devint une des plus grandes gloires de la Russie.

Par sa sainteté, Serge est grand pour l’univers, car il a vécu pour l’humanité

entière. Mais son harmonie parfaite avec son peuple, ce qu’il y a de typique

dans sa nature, qui réunit les traits disséminés du caractère russe, lui

donnent quelque chose de particulièrement émouvant pour nous.

De là proviennent la vénération tout exceptionnelle dont il est entouré en

Russie et la canonisation tacite dont il a été l’objet, et par laquelle le peuple

russe le reconnaît pour son saint par excellence ; privilège que personne

d’autre ne partage avec lui.

Saint Serge vivait aux temps du joug tartare. Il n’en souffrait pas

personnellement : les forêts de Radonège l’en préservaient. Mais il n’est pas resté

indifférent à l’oppression tartare. Tout ermite qu’il fût, il n’en éleva pas

moins la croix pour la Russie avec la résolution calme qui caractérisait tous

ses actes ; il bénit Dimitri Donskoï, en l’envoyant à la bataille de Koulikovo2

qui, grâce à son geste, a gardé un sens symboliquement mystique jusqu’à nos

jours.

Par ce combat avec le

khan mongol où s’engagèrent les Russes, le nom de Serge est resté lié à jamais

à l’œuvre de la construction de la Russie.

Aussi bien était-il doué pour l’action comme pour la contemplation. Cinq

siècles ont considéré son œuvre comme la juste cause.

Tous ceux qui venaient vénérer ses reliques à la Laure (couvent de la

Sainte-Trinité et de saint Serge) y étaient émus par la simplicité et la

sainteté qui y régnaient. L’esprit héroïque du moyen âge qui donna naissance à

tant de sainteté se manifestait là.

Rien de plus naturel que de juger d’une société et d’une époque d’après leur

manière d’apprécier un homme comme celui-là.

Saint Serge est un ennemi

pour tous ceux qui haïssent le Christ, qui s’affirment en niant la vérité. Ils

sont nombreux de notre temps où les « déchirures » du monde sont devenues si

grandes. Les Tartares, s’ils s’étaient approchés de son couvent, ne l’auraient

probablement pas attaqué ; ils savaient respecter la religion. Le métropolite

Pierre (contemporain de saint Serge) avait obtenu une charte de protection pour

le clergé russe de la part du khan Ouzbec.

Mais notre siècle s’est cru en droit de démolir la Laure, d’insulter les

reliques du saint. Pourtant il est hors de son pouvoir d’obscurcir son image.

Ceux qui habitent les environs du couvent ont déjà créé une légende, d’après

laquelle les reliques authentiques se seraient enfoncées dans la terre : le

saint se serait ainsi éloigné de ce monde grossier, comme il l’avait fait

jadis, dans l’expectative de temps meilleurs.

Qu’on le croie ou non, il reste indiscutable que l’image de Serge, après la

profanation de ses reliques, répand une lumière encore plus pure et plus

attirante. Le Christ a vaincu après sa crucifixion. B.Z. SUITE

Parmi les livres qui donnent un aperçu de la spiritualité orthodoxe, le Roseau

d’Or a choisi pour ses lecteurs l’ouvrage de M. Boris Zaïtzeff (1881-1971), qui

présente une des figures les plus populaires de la piété russe. Il importe en

effet que le public occidental soit informé sur ces questions par des documents

authentiques, lui procurant une connaissance directe. (N. D. E. 1927)

Rédigé par Parlons

D'orthodoxie le 18 Juillet 2020 à 06:30 | 0

commentaire | Permalien

SOURCE : https://www.egliserusse.eu/blogdiscussion/Boris-ZAITSEV-Saint-Serge-de-Radonege_a3847.html

Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926). Saint

Sergius of Radonezh. Icon for the Abramtsevo

church. 1882. Abramtsevo Museum

Also

known as

Sergius of Radonezh

Sergius of Radonez

Bartholomew of….

Profile

Born to the nobility, his

family moved to Radonezh to escape attack against the city of Rostov, losing

their fortune and becoming peasants in

the process. Following the deaths of

his parents, Sergius and his brother Stephen became hermits at

Makovka in 1335,

then each left separately to become a monk.

As Sergius’s reputation for holiness spread, he attracted so many students that

he founded the Holy Trinity monastery for

them; following his ordination at

Pereyaslav Zalesky, he served as its first abbot. His

brother joined the monastery,

but when he opposed Sergius’s strict rule, Sergius left the community to live

again as a hermit.

However, the monastery began

to decline, causing the metropolitan of Moscow to

order Sergius to return as abbot.

Advisor to the Prince of Moscow,

he encourged the campaign that ended with the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 which

ended the Mongol domination of Russia.

In the Russia that

followed he founded forty monasteries.

Late in life he resigned his position and retired to live his last few months

as a prayerful monk.

He is venerated as the foremost saint of Russia.

Born

c.1314 near

Rostov, Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia as Bartholomew

of Radonezh

25

September 1392 at

the Trinity Lavra of Saint Sergius of natural causes

1449 by Pope Nicholas

V

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

other

sites in english

Christian

Biographies, by James E Keifer

images

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

O God, whose blessed Son

became poor that we through his poverty might be rich: Deliver us from an

inordinate love of this world, that we, inspired by the devotion of your servant

Sergius of Moscow, may serve you with singleness of heart, and attain to the

riches of the age to come; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns

with you and the Holy

Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

MLA

Citation

“Saint Sergius of

Moscow“. CatholicSaints.Info. 19 November 2023. Web. 8 September 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-sergius-of-moscow/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-sergius-of-moscow/

Vyacheslav

Klykov. Saint Sergius of Radonezh. Statue in Danube Park, Novi Sad, Serbia,

1992.

Dunavski

park u Novom Sadu - skulptura ruskog igumana Sergija Radonješkog

St. Sergius of Radonezh

Feastday: September 25

Patron: of Russia

Birth: 1314

Death: 1392

One of the foremost

Russian saints and mystics. Born to a noble family near

Rostov, he was christened Bartholomew. At the age of fifteen, he fled with

his family to

Radonezh, near Moscow, to escape a campaign against Rostov by the rulers of

Moscow. As their wealth was all but wiped out, the family became

peasant farmers until 1335 when, after the death of his parents, he and his

brother Stephen became hermits at

Makovka. Stephen left to become a monk, and Sergius received a tonsure from

a local abbot. Increasingly well-known as a profoundly spiritual figure in the

Russian wilderness, he attracted followers and eventually organized them into a

community that became the famed Holy Trinity Monastery. He was ordained at

Pereyaslav Zalesky. Serving as abbot, he thus restored the great monastic

tradition which had been destroyed some time before

during the Mongol invasions of Russia. Sergius was soon joined by Stephen, who

opposed his stern cenobitical regulations and caused Sergius to leave the

community and to become a hermit again. As his departure brought swift decline

to the monastery, Sergius was asked to return by none other

than Alexis, metropolitan of

Moscow. As he was respected by virtually every segment of society, Sergius was

consulted by Prince flirnitry Donskoi of Moscow encouraging

the ruler to embark upon the campaign against the Mongols which culminated in

the triumphant Battle of Kulikovo (1380), thus breaking the Mongol domination

of Russia, Sergius sought to build upon this victory by promoting peace among

the ever-feuding Russian princes and building monasteries; in all he founded

around forty monastic communities. In 1378 he declined the office of

Metropolitan, resigning his abbacy in 1392 and dying six months later on

September 25, Canonized in 1449, he is venerated as the fore-most saint in

Russian history.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=2508

Mikhail Nesterov. Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, 1889,

160 x 211, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. One of a series of works depicting the acts of

the Venerable St Sergius of Radonezh (c.1321-91), baptised Bartholomew or

Varfolomei, shown here encountering a monk who helps him learn to read by

sharing a piece of holy bread

St Sergius of Radonezh

Celebrated on September

25th

Patron of Moscow and all

Russia, Sergius was born in Rostov of a noble family in 1315, about 100 years

after the Tartars conquered Russia. His family lost everything when he was 15

years old, in the civil war between Moscow and Rostov. Forced to flee, they

settled at Radonezh, living as poor peasants 50 miles north of Moscow.

After the death of their parents, Sergius and his brother Stephen went to live

as hermits in wild forests outside the town. They built a log cabin and a tiny

wooden church dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Eventually the elder brother found

the harsh conditions and lack of food too hard to bear and left.

Sergius stayed in the wilderness and was professed a monk by a local abbot. But

his hopes of staying alone did not work out. More and more people came to him

for advice and prayers. Many begged to join him. Russian monasticism had

virtually died out under Tartar rule. The new community that grew around

Sergius was to form the nucleus of a new and vibrant religious life in Russia.

He never turned anyone away.

In 1380 Dimitri Donskoi, Prince of Moscow, came to him for advice about how to

free Russia from the brutal Tartar occupation. Sergius said that if the Russian

troops had faith, their country would be freed. Dimitri believed him and his

army was victorious over the Tartars.

The saint now devoted himself to bringing peace to the divided country,

reconciling rival factions. In 1378 he refused to be consecrated Patriarch of

Moscow.

"Since the days of my youth I have never worn gold," he said.

"Now that I am an old man, more than ever I cling to my poverty."

Sergius cared for his community and founded another 40 before he resigned as

abbot and died peacefully shortly afterwards, in 1382.

SOURCE : https://www.indcatholicnews.com/saint/280

Sergei Kirillov. Sergius of Radonezh,

1992

Кириллов,

Сергей Алексеевич. «Преподобный Сергий

Радонежский

.

(Благословение). Вторая часть трилогии «Святая Русь». 1992. Х.м. 100 x 80

SERGIUS OF RADONEZH

ABBOT OF HOLY TRINITY (25 SEPT 1392)

To the people of Russia, Sergius is a national hero and an example of Russian

spiritual life at its best.

Sergius was born around

1314, the son of a farmer. When he was twenty, he and his brother began to live

as hermits in a forest near Moscow. Others joined them in what became the

Monastery of the Holy Trinity, a center for the renewal of Russian

Christianity. Pilgrims came from all Russia to worship and to receive spiritual

instruction, advice, and encouragement. The Russians were at the time largely

subservient to the neighboring (non-Christian) Tatar (or Tartar) people.

Sergius rallied the people behind Prince Dimitri Donskoi, who defeated the

Tatars in 1380 and established an independent Russia.

Sergius was a gentle man,

of winning personality. Stories told of him resemble those of Francis of

Assisi, including some that show that animals tended to trust him. He had the

ability to inspire in men an intense awareness of the love of God, and a

readiness to respond in love and obedience. He remained close to his peasant

roots. One contemporary said of him, "He has about him the smell of fir

forests." To this day, the effect of his personality on Russian devotion

remains considerable.

(The following material

is taken with minor alterations from The Lives of the Saints, by Sabine

Baring-Gould, author of the hymn "Onward, Christian Soldiers. The reader

will note that this account was written before the Communist Revolution, at a

time when the Czar was still ruler of Russia, and the Russian Orthodox Church

was the official religion of the country.)

The name of Sergius is as dear to every Russian's heart as that of William Tell to a Swiss, or that of Joan of Arc to a Frenchman. He was born at Rostoff in the early part of the 14th century, and when quite young left the house of his parents, and, together with his brother Stephen, settled himself in the dense forests of Radonege with bears for his companions, suffering from fierce cold in winter, often from famine. The fame of his virtues drew disciples around him. They compelled him to go to Peryaslavla-Zalessky, to receive priestly orders from Athanasius, Bishop of Volhynia, who lived there. Sergius built by his own labor in the midst of the forest a rude church of timber, by the name of the Source of Life, the Ever Blessed Trinity, which has since grown into the greatest, most renowned and wealthy monastery in all Russia--the Troitzka (=Trinity) Abbey, whose destiny has become inseparable from the destinies of the capital.

Princes and prelates applied to Sergius not only for advice, but also for teachers trained in his school, who might become in their realms and dioceses the heads of similar institutions, centers whence light and wisdom might shine. Tartar invasion had quenched the religious fervor of the Russians: a new era of zeal opened with the foundation of the Troitzka monastery and the labors of Sergius. At the request of Vladimir, Athanasius, a disciple of Sergius, founded the Visotsky monastery at Serpouchoff; and another of his pupils, Sabbas, laid the foundation of the convent of Svenigorod, while his nephew Theodore laid that of Simonoff in Moscow. In the terrible struggle against the Tartars, the heart of the Grand-Prince Demetrius failed him; how could he break the power of this inexhaustible horde which, like the locusts of the prophet Joel, had the garden of Eden before them and left behind them a desolate wilderness? It was the remonstrance, the prayers of Sergius, that encouraged the Prince to engage in battle with the horde on the fields of the Don. No historical picture or sculpture in Russia is more frequent than that which represents the youthful warrior receiving the benediction of the aged hermit. Two of his monks, Peresvet and Osliab, accompanied the Prince to the field, and fought in coats of mail drawn over their monastic habit; and the battle was begun by the single combat of Peresvet with a gigantic Tartar, champion of the Horde.

The two chief convents in the suburbs of Moscow still preserve the recollection of that day. One is the vast fortress of the Donskoi monastery, under the Sparrow Hills. The other is the Simonoff monastery already mentioned, founded on the banks of the Mosqua, on a beautiful spot chosen by the saint himself, and its earliest site was consecrated by the tomb which covers the bodies of his two warlike monks. From that day forth he stood out in the national recollection as the champion of Russia. It was from his convent that the noblest patriotic inspirations were drawn, and, as he had led the way in giving the first great repulse to the Tartar power, so the final blow in like manner came from a successor in his place. In 1480, when Ivan III wavered, as Demetrius had wavered before him, it was by the remonstrance of Archbishop Bassian, formerly prior of the Troitzka monastery, that Ivan too was driven, almost against his will, to the field. "Dost thou fear death?" so he was addressed by the aged prelate. "Thou too must die as well as others; death is the lot of all, man, beast, and bird alike; none avoid it. Give these warriors into my hands, and, old as I am, I will not spare myself, nor turn my back upon the Tartars." The Metropolitan, we are told, added his exhortations to those of Bassian. Ivan returned to the camp, the Khan of the Golden Horde fled without a blow, and Russia was set free for ever. [Note: The reader will remember that Constantinople (also called New Rome) fell to the Turks in 1453, and thus the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire came to an end. This same Ivan III married the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, and so claimed for himself a position in the line of Christian Emperors beginning with Constantine, and for Moscow the position of Third Rome, the capital thenceforth of the Christian world.]

Now back to the time of Sergius.

The Metropolitan, Alexis, being eighty-four years old, perceived that his end was approaching, and he wished to give Sergius his blessing and appoint him as his successor. But the humble monk, in great alarm, declared that he could not accept and wear the sacred picture of the Blessed Virgin suspended by gold chains, which the primate had sent him from his own breast on which it had hung. "From my youth up," said he, "I have never possessed or worn gold, and how now can I adorn myself in my old age?" St. Sergius died at an extremely advanced age in 1392, amidst the lamentations of his contemporaries.

by James Kiefer

SOURCE : http://www.satucket.com/lectionary/Sergius.htm

Миниатюра

"Сергий Радонежский благословляет Пересвета перед Мамаевым побоищем"

из Лицевого летописного свода Иоанна Грозного. Вторая половина 16 века. «Тогда

же

преподобного

игумена Сергия Радонежского изящный его послушник инок Пересвет начал говорить

великому князю и всем князям: „Нисколько о не сем смущайтесь, велик Бог наш и

великая крепость от него. Я хочу Божиею помощию, и пречистой его матери, и всех

святых его, и преподобного игумена Сергия молитвами с ним встретиться“. Был же

сей Пересвет, когда в мире был, славный богатырь, великую силу и крепость имел,

ростом и широтою плеч всех превосходил, и смышлен был весьма к воинскому делу»

(Татищев.

История Российская). XVI century (1558-1576)

The Life of our Venerable Father Amongst the Saints St. Sergius of Radonezh

Part 1 Childhood & the Hermitage

Our holy Father Sergius was born of noble, Orthodox, devout parents. His father was named Cyril and his mother Mary. They found favour with God; they were honourable in the sight of God and man, and abounded in those virtues which are well-pleasing unto God. Cyril had three sons, Stephen, Bartholomew, and Peter, whom he brought up in strict piety and purity.

Stephen and Peter quickly learned to read and write, but the second boy did not

so easily learn to write, and worked slowly and inattentively; his master

taught him with care, but the boy could not put his mind to his studies, nor

understand, nor do the same as his companions who were studying with him. As a

result he suffered from the many reproaches of his parents, and still more from

the punishments of his teacher and the ridicule of his companions. The boy

often prayed to God in secret and with many tears: "O Lord, give me

understanding of this learning. Teach me, Lord, enlighten and instruct

me." His reverence for God prompted him to pray that he might receive

knowledge from God and not from men.

One day his father sent him to seek for a lost foal. On his way he met a monk,

a venerable elder, a stranger, a priest, with the appearance of an angel. This

stranger was standing beneath an oak tree, praying devoutly and with much

shedding of tears. The boy, seeing him, humbly made a low obeisance, and

awaited the end of his prayers.

The venerable monk, when he had ended his prayers, glanced at the boy and, conscious that he beheld the chosen vessel of the Holy Spirit, he called him to his side, blessed him, bestowed on him a kiss in the name of Christ, and asked: "What art thou seeking, or what dost thou want, child?" The boy answered, "My soul desires above all things to understand the Holy Scriptures. I have to study reading and writing, and 1 am sorely vexed that 1 cannot learn these things. Will you, holy Father, pray to God for me, that he will give me understanding of book-learning?" The monk raised his hands and his eyes toward heaven, sighed, prayed to God, then said, "Amen."

Taking out from his satchel, as it were some treasure, with three fingers, he handed to the boy what appeared to be a little bit of white wheaten bread prosphora, saying to him: "Take this in thy mouth, child, and eat; this is given thee as a sign of God's grace and for the understanding of Holy Scriptures. Though the gift appears but small, the taste thereof is very sweet."

The boy opened his mouth and ate, tasting a sweetness as of honey, wherefore he

said, "Is it not written, How sweet are thy words to my palate, more than

honey to my lips, and my soul doth cherish them exceedingly?" The monk

answered and said, "If thou believest, child, more than this will be

revealed to thee; and do not vex thyself about reading and writing; thou wilt

find that from this day forth the Lord will give thee learning above that of

thy brothers and others of thine own age."

Having thus informed him of divine favour, the monk prepared to proceed on his

way. But the boy flung himself, with his face to the ground, at the feet of the

monk, and besought him to come and visit his parents, saying, "My parents

dearly love persons such as you are, Father." The monk, astonished at his

faith, accompanied him to his parents' house.

At the sight of the stranger, Cyril and Mary came out to meet him, and bowed low before him. The monk blessed them, and they offered him food, but before accepting any food, the monk went into the chapel, taking with him the boy whose consecration had been signified even before birth, and began a recitation of the Canonical Hours, telling the boy to read the Psalms. The boy said, "I do not know them, Father." The monk replied, "I told thee that from today the Lord would give thee knowledge in reading and writing; read the Word of God, nothing doubting." Whereupon, to the astonishment of all present, the boy, receiving the monk's blessing, began to recite in excellent rhythm; and from that hour he could read.

His parents and brothers praised God, and after accompanying the monk to the house, placed food before him. Having eaten, and bestowed a blessing on the parents, the monk was anxious to proceed on his way. But the parents pleaded, "Reverend Father, hurry not away, but stay and comfort us and calm our fears. Our humble son, whom you bless and praise, is to us an object of marvel. While he was yet in his mother's womb three times he uttered a cry in church during holy Liturgy. Wherefore we fear and doubt of what is to be, and what he is to do."

The holy monk, after considering and becoming aware of that which was to be, exclaimed, "O blessed pair, 0 worthy couple, giving birth to such a child! Why do you fear where there is no place for fear? Rather rejoice and be glad, for the boy will be great before God and man, thanks to his life of godliness." Having thus spoken the monk left, pronouncing an obscure saying that their son would serve the Holy Trinity and would lead many to an understanding of the divine precepts. They accompanied him to the doorway of their house, when he became of a sudden invisible. Perplexed, they wondered if he had been an angel, sent to give the boy knowledge of reading.

After the departure of the monk, it became evident that the boy could read any book, and was altogether changed; he was submissive in all things to his parents, striving to fulfil their wishes, and never disobedient. Applying himself solely to glorifying God, and rejoicing therein, he attended assiduously in Gods church, being present daily at Matins, at the Liturgy, at Vespers. He studied holy scripts, and at all times, in every way, he disciplined his body and preserved himself in purity of body and soul.

Cyril, devout servant of God, led the life of a wealthy and renowned boyar, in the province of Rostov, but in later years he was reduced to poverty. He, like others, suffered from the invasions of Tatar hordes into Russia, from the skirmishes of troops, the frequent demands for tribute, and from repeated bad harvests, in conjunction with the period of violence and disorder which followed the great Tatar war.

When the principality of Rostov fell into the hands of the Grand Duke Ivan Danilovich of Moscow, distress prevailed in the town of Rostov, and not least among the princes and boyars. They were deprived of power, of their properties, of honours and rank, of all of which Moscow became the possessor. By order of the Grand Duke they left Rostov, and a certain noble, Vasilii Kochev, with another called Minas, were sent from Moscow to Rostov as voevodas (messengers).

On arrival in the town of Rostov these two governors imposed a levy on the town and on the inhabitants. A severe persecution followed, and many of the remaining inhabitants of Rostov were constrained to surrender their estates to the Muscovites, in exchange for which they received wounds and humiliations, and went forth empty-handed and really as beggars. In brief, Rostov was subjected to every possible humiliation, even to the hanging, head downward, of their governor, Averkii, one of the chief boyars of Rostov.

Seeing and hearing of all this, terror spread among the people, not only in the town of Rostov but in all the surrounding country. Cyril, Gods devout servant, avoided further misfortune by escaping from his native town. He assembled his entire household and family and with them removed from Rostov to Radonezh, where he settled near the church dedicated to the Birth of Christ, which is still standing to this day.

Cyril's two sons, Stephen and Peter, married, but his second son, Bartholomew,

would not contemplate marriage, being desirous of becoming a monk. He often

expressed this wish to his father, but his parents said to him, "My son,

wait a little and bear with us; we are old, poor and sick, and we have no one

to look after us, for both your brothers are married." The wondrous youth

gladly promised to care for them to the end of their days, and from henceforth

strove for his parents' well-being, until they entered the monastic life and

went one to a monastery, and the other to a convent. They lived but a few

years, and passed away to God. Blessed Bartholomew laid his parents in their

graves, mourned for them forty days, then returned to his house.

Calling his younger brother Peter, he bestowed his share of his father's

inheritance on him, retaining nothing for himself. The wife of his elder

brother, Stephen, died also, leaving two sons, Clement and Ivan. Stephen soon

renounced the world and became a monk in the Monastery of the Theotokis at

Khotkov. Blessed Bartholomew now came to him, and begged him to accompany him

in the search for some desert place. Stephen assented, and he and the saint

together explored many parts of the forest, till finally they came to a waste

space in the middle of the forest, near a stream. After inspecting the place

they obeyed the voice of God and were satisfied.

Having prayed, they set about chopping wood and carrying it. First they built a hut, and then constructed a small chapel. When the chapel was finished and the time had come to dedicate it, Blessed Bartholomew said to Stephen, "Now, my lord and eldest brother by birth and by blood, tell me, in honour of whose feast shall this chapel be, and to which saint shall we dedicate it?" Stephen answered: "Why do you ask me, and why put me to the test? You were chosen of God while you were yet in your mother's womb, and he gave a sign concerning you before ever you were born, that the child would be a disciple of the Blessed Trinity, and not he alone would have devout faith, for he would lead many others and teach them to believe in the Holy Trinity. it behoves you, therefore, to dedicate a chapel above all others to the Blessed Trinity." The favoured youth gave a deep sigh and said, "To tell the truth, my lord and brother, I asked you because I felt I must, although I wanted and thought likewise as you do, and desired with my whole soul to erect and dedicate this chapel to the Blessed Trinity, but out of humility I inquired of you." And he went forthwith to obtain the blessing of the ruling prelate for its consecration.

From the town came the priest sent by Feognost, Metropolitan of Kiev and all Russia, and the chapel was consecrated and dedicated to the the Most Holy Trinity in the reign of the Grand Duke Semion Ivanovich, we believe in the beginning of his reign. The chapel being now built and dedicated, Stephen did not long remain in the wilderness with his brother. He realised soon all the labours in this desert place, the hardships, the all-pervading need and want, and that there were no means of satisfying hunger and thirst, nor any other necessity.

As yet no one came to the saint, nor brought him anything, for at this time,

nowhere around was there any village, nor house, nor people; neither was there

road or pathway, but everywhere on all sides were forest and wasteland.

Stephen, seeing this, was troubled, and he decided to leave the wilderness, and

with it his own brother the saintly desert-lover and desert-dweller. He went

from thence to Moscow, and when he reached this city he settled in the

Monastery of the Epiphany, found a cell, and dwelt in it, exercising himself in

virtue. Hard labour was to him a joy, and he passed his time in ascetic

practices in his cell, disciplining himself by fasting and praying, refraining

from all indulgence, even from drinking Kvas (a mild russian beer).

Part 2 Hermetic Life

Aleksei, the future

metropolitan, who at this time had not been raised to the rank of bishop, was

living in the monastery of the Theotokis in Khotkov, leading a quiet monastic

life. Stephen and he spent much time together in spiritual exercises, and they

sang in the choir side by side. The Grand Duke Simion came to hear of Stephen

and the godly life he led and commanded the Metropolitan Theognost to ordain him

priest and, later, to appoint him abbot of the monastery. Aware of his great

virtues, the Grand Duke also appointed him as his confessor. Our saint,

Sergius, had not taken monastic vows at this time for, as yet, he had not

enough experience of monastic life, and of all that is required of a

monk.

After a while, however,

he invited a spiritual elder, who held the dignity of priest and abbot, named

Mitrofan, to come and visit him in his solitude. In great humility he entreated

him, "Father, may the love of God be with us, and give me the tonsure of a

monk. From childhood have I loved God and set my heart on Him these many years,

but my parents' needs withheld me. Now, my lord and father, I am free from all

bonds, and I thirst, as the hart thirsteth for the springs of living

water." The abbot forthwith went into the chapel with him, and gave him

the tonsure on the 7th day of October on the feast day of the blessed martyrs

Sergius and Bacchus. And Sergius was the name he received as monk. In those

days it was the custom to give to the newly tonsured monk the name of the saint

whose feast day it happened to be.

Our saint was

twenty-three years old when he joined the order of monks. Blessed Sergius, the

newly tonsured monk, partook of the Holy Sacrament and received the grace of

God and the gift of the Holy Spirit. From one whose witness is true and sure,

we are told that when Sergius partook of the Holy Sacrament the chapel was

filled with a sweet odour; and not only in the chapel, but all around was the

same fragrant smell. The saint remained in the chapel seven days, touching no

food other than one consecrated loaf given him by the abbot, refusing all else

and giving himself up to fasting and prayer, having on his lips the Psalms of

David.

When Mitrofan bade

farewell, St. Sergius in all humility said to him: "Give me your blessing,

and pray regarding my solitude; and instruct one living alone in the wilderness

how to pray to the Lord God; how to remain unharmed; how to wrestle with the evil

one and with one's own temptation to fall into pride, for I am but a novice and

a newly tonsured monk." The abbot was astonished and almost afraid. He

replied, "You ask of me concerning that which you know no less well than

we do, 0 Reverend Father."

After discoursing with

him for a while on spiritual matters, and commending him to God, Mitrofan went

away, leaving St. Sergius alone to silence and the wilderness. Who can recount

his labours? Who can number the trials he endured living alone in the wilderness?

Under different forms, and from time to time, the devil wrestled with the

saint, but the demons beset St. Sergius in vain; no matter what visions they

evoked, they failed to overcome the firm and fearless spirit of the ascetic. At

one moment it was Satan who laid his snares; at another, incursions of wild

beasts took place, for many were the wild animals inhabiting this wilderness.

Some of these remained at a distance; others came near the saint, surrounded

him and even sniffed him.

In particular a bear used

to come to the holy man. Seeing the animal did not come to harm him, but in

order to get some food, the saint brought a small slice of bread from his but,

and placed it on a log or stump, so the bear learned to come for the meal thus

prepared for him, and having eaten it went away again. If there was no bread,

and the bear did not find his usual slice, he would wait about for a long while

and look around on all sides, rather like some moneylender waiting to receive

payment of his debt.

At this time Sergius had

no variety of foods in the wilderness, only bread and water from the spring,

and a great scarcity of these. Often, bread was not to be found; then both he

and the bear went hungry. Sometimes, although there was but one slice of bread,

the saint gave it to the bear, being unwilling to disappoint him of his

food.

He diligently read the

Holy Scriptures to obtain a knowledge of all virtue, in his secret meditations

training his mind in a longing for eternal bliss. Most wonderful of all, none

knew the measure of his ascetic and godly life spent in solitude. God, the

beholder of all hidden things, alone saw it. Whether he lived two years or more

in the wilderness alone we do not know; God knows only. The Lord, seeing his

very great faith and patience, took compassion on him and, desirous of

relieving his solitary labours, put into the hearts of certain god-fearing

monks to visit him. The saint inquired of them, "Are you able to endure

the hardships of this place, hunger and thirst, and every kind of want?"

They replied, "Yes, Reverend Father, we are willing with God's help and

with your prayers."

Holy Sergius, seeing

their faith and zeal, marvelled, and said: "My brethren, I desired to

dwell alone in the wilderness and, furthermore, to die in this place. If it be

Gods will that there shall be a monastery in this place, and that many brethren

will be gathered here, then may God's holy will be done. I welcome you with

joy, but let each one of you build himself a cell. Furthermore, let it be known

unto you, if you come to dwell in the wilderness, the beginning of

righteousness is the fear of the Lord."

To increase his own fear

of the Lord he spent day and night in the study of God's word. Moreover, young

in years, strong and healthy in body, he could do the work of two men or more.

The devil now strove to wound him with the darts of concupiscence. The saint,

aware of these attacks of the enemy, disciplined his body and exercised his

soul, mastering it with fasting, and thus was he protected by the grace of

God.

Although not yet raised to the office of priesthood, dwelling in company with the brethren, he was present daily with them in church for the reciting of the offices, Nocturnes, Matins, the Hours, and Vespers. For the Liturgy a priest, who was an abbot, came from one of the villages. At first Sergius did not wish to be raised to the priesthood and especially he did not want to become an abbot; this was by reason of his extreme humility. He constantly remarked that the beginning and root of all evil lay in pride of rank, and ambition to be an abbot. The monks were but few in number, about a dozen.

They constructed themselves cells, not very large ones, within the enclosure,

and put up gates at the entrance. Sergius built four cells with his own hands,

and performed other monastic duties at the request of the brethren; he carried

logs from the forest on his shoulders, chopped them up and carried them into

the cells. The monastery, indeed, came to be a wonderful place to look upon.

The forest was not far distant from it as now it is; the shade and the murmur

of trees hung above the cells; around the church was a space of trunks and

stumps; here many kinds of vegetables were sown. But to return to the exploits

of St. Sergius. He flayed the grain and ground it in the mill, baked the bread

and cooked the food, cut out shoes and clothing and stitched them; he drew

water from the spring flowing nearby, and carried it in two pails on his

shoulders, and put water in each cell. He spent the night in prayer, without

sleep, feeding only on bread and water, and that in small quantifies; and never

spent an idle hour.

Within the space of a

year the abbot who had given the tonsure to St. Sergius fell ill, and after a

short while, he passed out of this life. Then God put it into the hearts of the

brethren to go to blessed Sergius, and to say to him: "Father, we cannot

continue without an abbot. We desire you to be the guide of our souls and

bodies." The saint sighed from the bottom of his heart, and replied,

"I have had no thought of becoming abbot, for my soul longs to finish its

course here as an ordinary monk."

Part 3 His Abbothood

Within the space of a year the abbot who had given the tonsure to St. Sergius fell ill, and after a short while, he passed out of this life. Then God put it into the hearts of the brethren to go to blessed Sergius, and to say to him: "Father, we cannot continue without an abbot. We desire you to be the guide of our souls and bodies." The saint sighed from the bottom of his heart, and replied, "I have had no thought of becoming abbot, for my soul longs to finish its course here as an ordinary monk."

The brethren urged him again and again to be their abbot; finally, overcome by his compassionate love, but groaning inwardly, he said: "Fathers and brethren, I will say no more against it, and will submit to the will of God. He sees into our hearts and souls. We will go into the town, to the bishop." Aleksei, the Metropolitan of all Russia, was living at this time in Constantinople, and he had nominated Bishop Afanasii of Volynia in his stead in the town of Pereiaslavl. Our blessed Sergius went, therefore, to the bishop, taking with him two elders; and entering into his presence made a low obeisance.

Afanasii rejoiced exceedingly at seeing him, and kissed him in the name of Christ. He had heard tell of the saint and of his beginning of good deeds, and he spoke to him of the workings of the Spirit. Our Blessed Father Sergius begged the bishop to give them an abbot, and a guide of their souls. The venerable Afanasii replied, "Thyself, son and brother, God called in thy mother's womb. It is thou who wilt be father and abbot of thy brethren." Blessed Sergius refused, insisting on his unworthiness, but Afanasii said to him, "Beloved, thou hast acquired all virtue save obedience." Blessed Sergius, bowing low, replied-. "May God's will be done. Praised be the Lord forever and forever." They all answered, "Amen." Without delay the holy bishop, Afanasii, led blessed Sergius to the church, and ordained him subdeacon and then deacon.

The following morning the saint was raised to the dignity of priesthood, and was told to say the holy liturgy and to offer the bloodless Sacrifice. Later, taking him to one side, the bishop spoke to him of the teachings of the Apostles and of the holy fathers, for the edification and guidance of souls. After bestowing on him a kiss in the name of Christ, he sent him forth, in very deed an abbot, pastor, and guardian, and physician of his spiritual brethren.

He had not taken upon himself the rank of abbot; he received the leadership from God; he had not sought it, nor striven for it; he did not obtain it by payment, as do others who have pride of rank, chasing hither and thither, plotting and snatching power from one another. God himself led his chosen disciple and exalted him to the dignity of abbot.

Our revered father and abbot Sergius returned to his monastery, to the abode dedicated to the Holy Trinity, and the brethren, coming out to meet him, bowed low to the ground before him. He blessed them, and said: "Brethren, pray for me. I am altogether ignorant, and I have received a talent from the Highest, and 1 shall have to render an account of it, and of the flock committed to me." There were twelve brethren when he first became abbot, and he was the thirteenth. And this number remained, neither increasing nor diminishing, until Simon, the archimandrite of Smolensk, arrived among them. From that time onward their numbers constantly increased. This wondrous man, Simon, was chief archimandrite, excellent, eminent, abounding in virtue. Having heard of our Reverend Father Sergius' way of life, he laid aside honours, left the goodly city of Smolensk, and arrived at the monastery where, greeting our Reverend Father Sergius with the greatest humility, he entreated him to allow him to live under him and his rules in all submission and obedience: and he offered the estate he owned as a gift to the abbot for the benefit of the monastery. Blessed Sergius welcomed him with great joy.

Simon lived many years, submissive and obedient, abounding in virtue, and died in advanced old age. Stephen, the saint's brother, came with his younger son, Ivan, from Moscow and, presenting him to Abbot Sergius, asked him to give him the tonsure. Abbot Sergius did so, and gave him the name of Theodore; from his earliest years the boy had been taught abstinence, piety, and chastity, following his uncle's precepts; according to some accounts he was given the tonsure when he was ten years old, others say twelve. People from many parts, towns and countries, came to live with Abbot Sergius, and their names are written in the book of life. The monastery bit by bit grew in size.

It is recorded in the Paterikon -that is to say, in the book of the early fathers of the Church - that the holy fathers in assembly prophesied about later generations, saying that the last would be weak. But, of the later generations, God made Sergius as strong as one of the early fathers. God made him a lover of hard work, and to be the head over a great number of monks. From the time he was appointed abbot, the holy Liturgy was sung every day. He himself baked the holy bread; first he flayed and ground the wheat, sifted the flour, kneaded and fermented the dough; he entrusted the making of the holy bread to no one. He also cooked the grains for the "kutia," and he also made the candles.

Although occupying the chief place as abbot, he did not alter in any way his monastic rules. He was lowly and humble with all people, and was an example to all. He never sent away anyone who came to him for the tonsure, neither old nor young, nor rich nor poor; he received them all with fervent joy; but he did not give them the tonsure at once. He who would be a monk was ordered, first, to put on a long, black cloth garment and to live with the brethren until he got accustomed to all the monastic rules; then, later, he was given full monk's attire of cloak and hood. Finally, when he was deemed worthy, he was allowed the "schema," the mark of the ascetic.

After Vespers, and late at night, especially on long dark nights, the saint used to leave his cell and do the rounds of the monk's cells. If he heard anyone saying his prayers, or making genuflections, or busy with his own handiwork, he was gratified and gave thanks to God. If, on the other hand, he heard two or three monks chatting together, or laughing, he was displeased, rapped on the door or window, and passed. on. In the morning he would send for them and, indirectly, quietly and gently, by means of some parable, reprove them. If he was a humble and submissive brother he would quickly admit his fault and, bowing low before St. Sergius, would beg his forgiveness. If, instead, he was not a humble brother, and stood erect thinking he was not the person referred to, then the saint, with patience, would make it clear to him, and order him to do a public penance.

In this way they all learned to pray to God assiduously; not to chat with one another after Vespers, and to do their own handiwork with all their might; and to have the Psalms of David all day on their lips.

In the beginning, when the monastery was first built, many were the hardships and privations. A main road lay a long way off, and wilderness surrounded the monastery. Here the monks lived, it is believed, for fifteen years. Then, in the time of the Grand Duke Ivan Ivanovich Christians began to arrive from all parts and to settle in the vicinity. The forest was cut down; there was no one to prevent it; the trees were hewn down, none were spared, and the forest was converted into an open plain as we now see it. A village was built, and houses; and visitors came to the monastery bringing their countless offerings. But in the beginning, when they settled in this place, they all suffered great privations. At times there was no bread or flour, and all means of subsistence was lacking; at times there was no wine for the Eucharist, nor incense, nor wax candles. The monks sang Matins at dawn with no lights save that of a single birch or pine torch.

One day there was a great scarcity of bread and salt in the whole monastery. The saintly abbot gave orders to all the brethren that they were not to go out, nor beg from the laity, but to remain patiently in the monastery and await God's compassion. He himself spent three or four days without any food. On the fourth day, at dawn, taking an axe, he went to one of the elders, by name Daniel, and said to him: "I have heard tell that you want to build an entrance in front of your cell. See, 1 have come to build it for you, so that my hands shall not remain idle." Daniel replied, "Yes, I have been waiting for it a long while, and am as yet awaiting the carpenter from the village; but I am afraid to employ you, for you will require a large payment from me." Sergius said to him: "I do not require a large sum of money. Have you any mildewed loaves? I very much want to eat some such loaves. 1 do not ask from you anything else. Where will you find another carpenter like me?" Daniel brought him a few mildewed loaves, saying, "This is all I have." Sergius said: "That will be enough, and to spare. But bide it until evening. I take no pay before the work is done." Saying which, and tightening his belt, he chopped and worked all day, cut planks and put up the entrance.

At the close of day, Daniel brought him the sieveful of the promised loaves. Sergius, offering a prayer and grace, distributed the bread to the brethren, ate his portion of bread and drank some water. He had neither soup nor salt; the bread was both dinner and supper. Several of the brethren noticed something in the nature of a faint breath of smoke issuing from his lips, and turning to one another they said, "Oh, brother, what patience and self-control has this man!" But one of the monks, not having had anything to eat for two days, murmured against Sergius, and went up to him and said: "Why this mouldy bread? Why should we not go outside and beg for some bread? If we obey you we shall perish of hunger. Tomorrow morning we will leave this place and go hence and not return; we cannot any longer endure such want and scarcity."

Not all of them complained, only the one brother, but because of this one,

Sergius, seeing they were enfeebled and in distress, convoked the whole

brotherhood and gave them instruction from Holy Scriptures: "God's Grace

cannot be given without trials; after tribulations comes joy. It is written, at

evening there shall be weeping but in the morning gladness. You, at present,

have no bread or food, and tomorrow you will enjoy an abundance." And as

he was yet speaking there came a rapping at the gates.

The porter, peeping through an aperture, saw that a store of provisions had

been brought; he was so overjoyed that he did not open the gates but ran first

to St. Sergius to tell him. The saint gave the order at once, "Open the

gates quickly, let them come in, and let those persons who have brought the

provisions be invited to share the meal"; while he himself, before all

else, directed that the bell should be sounded, and with the brethren he went

into the church to sing a Moleben of Thanksgiving. Returning from church, they

went into the refectory, and the newly arrived, fresh bread was placed before

them. The bread was still warm and soft, and the taste of it was of an

unimaginable strange sweetness, as it were honey mingled with juice of barley

and spices.

When they had eaten, the saint remarked: "And where is our brother who was murmuring about mouldy bread? May he notice that it is sweet and fresh. Let us remember the prophet who said, 'Ashes have I eaten for bread and mixed my drink with tears.' Then he inquired whose bread it was, and who had sent it. The messengers announced, "A pious layman, very wealthy, living a great distance away, sent it to Sergius and his brotherhood." Again the monks, on Sergius' orders, invited the men to sup with them, but they refused, having to hasten elsewhere. The monks came to the abbot in astonishment, saying, "Father, how has this wheaten bread, warm and tasting of butter and spices, been brought from far?"

The following day more food and drink were brought to the monastery in the same manner. And again on the third day, from a distant country. Abbot Sergius, seeing and hearing this, gave glory to God before al] the brethren, saying, "You see, brethren, God provides for everything, and neither does he abandon this place." From this time forth the monks grew accustomed to being patient under trials and privations, enduring all things, trusting in the Lord God with fervent faith, and being strengthened therein by their holy Father Sergius.