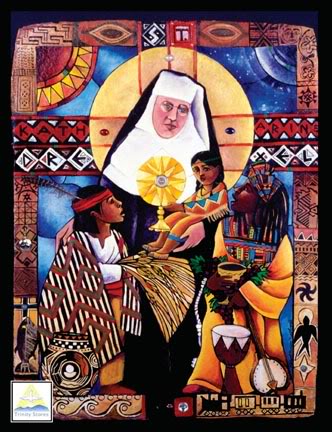

Sainte Catherine Marie

Drexel

Elle naquit à Philadelphie

aux Etats-Unis, dans une famille fortunée et donna tout ce qu’elle possédait

pour soutenir la population noire qui vivait dans un état misérable après

l'émancipation des esclaves. Elle combattit les préjugés raciaux et, pour cela,

et fonda les Sœurs du Saint-Sacrement pour les Indiens et les Noirs. A leur

intention, elle ouvrit de nombreuses écoles dont la "Xavier

University" ouverte aux Afro-américains à La Nouvelle-Orléans en

Louisiane. Elle dut affronter courageusement les difficultés et les obstacles

que lui valaient ses initiatives audacieuses. Elle mourut en 1955.

Sainte Catherine Marie

Drexel

A Philadelphie aux

Etats-Unis, fondatrice de la Congrégation des Sœurs du Saint-Sacrement (+ 1955)

Elle naquit à

Philadelphie aux États-Unis, dans une famille très riche et donna toute sa

fortune pour soutenir la population noire qui vivait dans un état misérable

après l'émancipation des esclaves. Elle combattit les préjugés raciaux et,

pour cela, et fonda les Sœurs du Saint-Sacrement pour les Indiens et les gens

de couleur. A leur intention, elle ouvrit de nombreuses écoles dont la

"Xavier University" ouverte aux Afro-américains à La Nouvelle-Orléans

en Louisiane. Elle dut affronter courageusement les difficultés et les

obstacles que lui valaient ses initiatives audacieuses.

Canonisée le 1er octobre

2000 par Jean-Paul II

- Xavier

university of Louisiana - les Sœurs du Saint-Sacrement, congrégation fondée

en 1891 - en anglais.

- Katharine

Drexel - Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament - en anglais.

À Philadelphie, en

Pennsylvanie aux États-Unis, en 1955, sainte Catherine Drexel, vierge, qui

fonda la Congrégation des Sœurs du Saint-Sacrement et dépensa non seulement les

biens qu’elle avait reçus en héritage, mais encore toutes ses forces, pour

éduquer et aider les Indiens et les Noirs d’Amérique.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/5971/Sainte-Catherine-Marie-Drexel.html

SAINTE CATHERINE

MARIE DREXEL

Religieuse, fondatrice,

sainte

1858-1955

Katharine Drexel naît à

Philadelphie (Pennsylvanie) en 1858. Son père, catholique, est banquier; c'est

un millionnaire philanthrope. Sa mère, protestante, meurt peu après sa

naissance, et son père se remarie. Dan sa famille, on lui enseigne que les

biens dont ils disposent ne sont pas seulement pour eux, mais doivent être

partagés avec les moins chanceux. Au cours d'un voyage en famille dans l'Ouest

de Etats-Unis, elle est profondément émue par la pauvreté et les conditions

dégradantes de vie des Peaux-Rouges et des Noirs (Afro-américains). Elle

utilise alors sa fortune pour financer des œuvres et aider des missionnaires.

En 1887, elle crée l'école Sainte Catherine, sa première école, à Santa Fe

(Nouveau-Mexique). Elle est bien effleurée parfois par l'idée d'une vocation

religieuse, mais la pensée de prendre l'habit et de renoncer au monde à jamais

lui fait horreur. Au cours de l'un de ses voyages en Europe, elle va à Rome et

expose la situation sociale à Léon XIII en lui demandant d'envoyer des

missionnaires. Quelle n'est pas sa surprise quand le Pape lui demande

doucement: "Et pourquoi, mon enfant, ne vous feriez-vous pas missionnaire

vous-même?" La première réaction, après l'audience, est la colère. Sur le

bateau du retour, son émotion n'est pas encore calmée. Elle projette d'en

parler à l'arrivée à son directeur spirituel, l'évêque James O'Connor.

Cet événement constitue sûrement un tournant dans la vie de la bienheureuse

Katharine. Avec un grand courage, elle place sa confiance dans le Seigneur et

elle choisit de donner entièrement non seulement sa fortune, mais toute sa vie

au Seigneur. En 1890, elle entre au Noviciat des Sœurs de la Miséricorde à

Pittsburgh avec l'intention de pouvoir fonder, par la suite, une communauté

religieuse qui aurait pour finalité l'adoration du Saint Sacrement et

l'évangélisation des Américains de couleur et des Indiens. En 1891, au terme

d'une année de noviciat, elle prononce ses vœux simples qui font d'elle la

première Sœur et la supérieure de la communauté du Saint-Sacrement. L'année

suivante, les Sœurs achèvent de s'installer dans le couvent Sainte-Elizabeth à

Cornwells Heights (Pennsylvanie). Leur spiritualité est basée sur l'union avec

le Seigneur-Eucharistie et le service des pauvres et des victimes de

discriminations raciales. Son apostolat contribue à diffuser la conscience

qu'il faut combattre toutes les formes de racisme au moyen de l'éducation et

des services sociaux. En effet, dans les plantations, les gens de couleur sont

très mal payés et les enfants ne sont pas scolarisés. Elle crée une soixantaine

d'écoles. Sa plus grande œuvre est l'érection en 1925, à la Nouvelle-Orléans,

de la "Xavier University" pour les Noirs. (Lorsqu'en1954 la Cour

suprême abolira la séparation des races dans les écoles, cette université

ouvrira ses portes à tous les étudiants sans distinction de couleur ou de

religion.

En 1935, malade et plus que septuagénaire, une crise cardiaque l'affaiblit

beaucoup, et voilà vingt ans qu'elle n'est plus à la tête de sa communauté. Les

18 dernières années de sa vie, devenue presque totalement immobile, elle

consacre son temps à une prière intense. Elle meurt en 1955, à 96 ans. Ses

dernières paroles sont: "O Esprit Saint, je voudrait être une plume, afin

que votre souffle m'emporte où bon vous semble." Entre l'ardente jeune

fille qui regimbait quelque peu contre l'aiguillon — épisode romain qu'elle

aimait à rappeler en souriant —, et la femme très âgée livrée sans résistance

au souffle de l'Esprit, quel chemin parcouru! "Puisse son exemple aider

les jeunes en particulier à reconnaître que l'on ne peut pas trouver de plus

grand trésor que de suivre le Christ avec un cœur sans partage en utilisant

généreusement les dons que nous avons reçus au service des autres afin de

collaborer ainsi à l'édifice d'un monde plus juste et plus fraternel."

(Jean Paul II)

Canonisée le 1° octobre 2000, place Saint-Pierre, par le Pape Jean-Paul II.

SOURCE : http://voiemystique.free.fr/catherine_marie_drexel.htm

CHAPELLE PAPALE POUR LA

CANONISATION DES BIENHEUREUX

HOMÉLIE DE SA SAINTETÉ

JEAN PAUL II

Dimanche 1er octobre 2000

1. "Ta parole

est vérité: consacre-nous dans ton amour" (Chant à l'Evangile:

cf. Jn 17, 17). Cette invocation, écho de la prière que le Christ

adresse au Père après la Dernière Cène, semble s'élever de la foule des saints

et des bienheureux, que l'Esprit de Dieu, de génération en génération, suscite

dans l'Eglise.

Aujourd'hui, deux mille

ans après le début de la Rédemption, nous faisons nôtres ces paroles, tandis

que nous avons devant nous comme modèles de sainteté Agostino Zhao Rong et

ses 119 compagnons, martyrs en Chine, Maria Josepha du Coeur de Jésus Sancho de

Guerra, Katharine Mary Drexel et Giuseppina Bakhita. Dieu

le Père les a "consacrés dans son amour", réalisant la

demande du Fils qui, pour lui donner un peuple saint, a ouvert les bras sur la

croix et, en mourant, a détruit la mort et proclamé la résurrection (cf. Prière

eucharistique, II, Préface).

A vous tous, chers frères

et soeurs, réunis ici en grand nombre pour exprimer votre piété envers ces

témoins lumineux de l'Evangile, j'adresse un salut cordial.

2. "Les

préceptes du Seigneur apportent la joie" (Ps. resp.). Ces paroles du

Psaume responsorial reflètent bien l'expérience d'Agostino Zhao Rong et de ses

119 compagnons, Martyrs en Chine. Les témoignages qui nous sont parvenus

laissent entrevoir chez eux un état d'âme empreint d'une profonde sérénité et

joie.

L'Eglise est aujourd'hui

reconnaissante au Seigneur, qui la bénit et l'inonde de lumière à travers la

splendeur de la sainteté de ces fils et filles de la Chine. L'Année Sainte

n'est-elle pas le moment le plus opportun pour faire resplendir leur témoignage

héroïque? La jeune Anna Wang, âgée de 14 ans, résiste aux menaces du bourreau

qui la somme d'apostasier, et, se préparant à être décapité, le visage

lumineux, déclare: "La porte du Ciel est ouverte à tous" et

murmure trois fois de suite "Jésus". A ceux qui viennent de lui

couper le bras droit et qui se préparent à l'écorcher vif, Chi Zhuzi, âgé de 18

ans, crie avec courage: "Chaque morceau de ma chair, chaque goutte

de mon sang vous répéteront que je suis chrétien".

Les 85 autres Chinois,

hommes et femmes de tout âge et de toute condition, prêtres, religieux et

laïcs, ont témoigné d'une conviction et d'une joie semblables en scellant leur

fidélité indéfectible au Christ et à l'Eglise à travers le don de la vie. Cela

est survenu au cours de divers siècles et en des temps complexes et difficiles

de l'histoire de Chine. La célébration présente n'est pas le lieu opportun pour

émettre des jugements sur ces périodes de l'histoire: on pourra et on

devra le faire en une autre occasion. Aujourd'hui, à travers cette proclamation

solennelle de sainteté, l'Eglise entend uniquement reconnaître que ces martyrs

sont un exemple de courage et de cohérence pour nous tous et font honneur au

noble peuple chinois.

Parmi cette foule de

martyrs resplendissent également 33 missionnaires, hommes et femmes, qui

quittèrent leur terre et tentèrent de s'introduire dans la réalité chinoise, en

assumant avec amour ses caractéristiques, désirent annoncer le Christ et servir

ce peuple. Leurs tombes sont là-bas, représentant presque un signe de leur

appartenance définitive à la Chine, que, même dans leurs limites humaines, ils

ont sincèrement aimée, dépensant pour elle toutes leurs énergies. "Nous

n'avons jamais fait de mal à personne - répond l'Evêque Francesco Fogolla au

gouverneur qui s'apprête à le frapper avec son épée - au contraire, nous avons

fait du bien à de nombreuses personnes".

Dieu fait descendre le

bonheur (en langue chinoise dans le texte).

3. Dans la première

lecture ainsi que dans l'Evangile de la liturgie d'aujourd'hui, nous avons vu

que l'Esprit souffle là où il le désire et que Dieu, en tout temps, élit des

personnes pour manifester son amour aux hommes et qu'il suscite des

institutions appelées à être des instruments privilégiés de son action. C'est ce

qui est arrivé à sainte Maria Josepha du Coeur de Jésus Sancho Guerra,

fondatrice des Servantes de Jésus de la Charité.

Dans la vie de la

nouvelle sainte, première basque à être canonisée, se manifeste de façon

particulière l'action de l'Esprit. Celui-ci la guida vers le service des

malades et la prépara à être la Mère d'une nouvelle famille religieuse.

Sainte Maria Josepha

vécut sa vocation comme une véritable apôtre dans le domaine de la santé, son

service cherchant à conjuguer l'attention matérielle avec l'attention

spirituelle, procurant par tous moyens le salut des âmes. Bien qu'elle fut

malade lors des douze dernières années de sa vie, elle ne s'épargna aucun

effort ni aucune souffrance, et se prodigua sans limites pour le service

caritatif du malade dans un climat d'esprit contemplatif, en rappelant que

"l'assistance ne consiste pas seulement à donner des médicaments et de la

nourriture au malade, il existe un autre type d'assistance,... celle du coeur,

en cherchant à s'adapter à la personne qui souffre".

Que l'exemple et

l'intercession de sainte Maria Josepha du Coeur de Jésus aident le peuple

basque à bannir pour toujours la violence, et qu'Euskadi devienne une terre

bénie et un lieu de coexistence pacifique et fraternelle, où soient toujours

respectés les droits de toutes les personnes et où le sang innocent ne soit

jamais versé.

4. "C'est un

feu que vous avez thésaurisé dans les derniers jours" (Jc 5,

3).

Dans la seconde Lecture

de la Liturgie d'aujourd'hui, l'Apôtre Jacques réprimande les riches qui se

reposent sur leur richesse et traitent les pauvres injustement. Mère

Katharine Drexel est née dans l'aisance à Philadelphie, aux Etats-Unis.

Mais ses parents lui ont enseigné que les possessions de sa famille n'étaient

pas seulement pour eux mais devaient être partagées avec les moins chanceux.

Devenue une jeune femme, elle fut profondément touchée par la pauvreté et les

conditions désespérées qu'enduraient de nombreux natifs américains et

afro-américains. Elle commença à consacrer sa fortune à l'oeuvre missionnaire

et éducative parmi les membres les plus pauvres de la société. Plus tard, elle

comprit que cela n'était pas suffisant. Avec un grand courage et une grande

confiance dans la grâce de Dieu, elle choisit de donner entièrement non

seulement sa fortune, mais toute sa vie au Seigneur.

A sa communauté

religieuse, les Soeurs du Bienheureux Sacrement, elle enseigna une spiritualité

fondée sur l'union de prière avec le Seigneur-Eucharistie et le service zélé

aux pauvres et aux victimes des discriminations raciales. Son apostolat

contribua à diffuser une conscience croissante du besoin de combattre toutes

formes de racisme à travers l'éducation et les services sociaux. Katharine

Drexel représente un excellent exemple de la charité concrète et de la

solidarité généreuse avec les plus pauvres qui est depuis longtemps la marque

distinctive des catholiques américains.

Puisse son exemple aider

les jeunes en particulier à reconnaître que l'on ne peut pas trouver de plus

grand trésor que de suivre le Christ avec un coeur sans partage et en utilisant

généreusement les dons que nous avons reçus au service des autres et pour l'édification

d'un monde plus juste et plus fraternel.

5. "La loi de

Yahvé est parfaite, [...] sagesse du simple" (Ps 19 [18], 8).

Ces paroles tirées du

Psaume responsorial d'aujourd'hui résonnent avec puissance dans la vie de Soeur

Giuseppina Bakhita. Enlevée et vendue en esclavage à l'âge de 7 ans, elle

endura de nombreuses souffrances entre les mains de maîtres cruels. Mais elle

comprit que la vérité profonde est que Dieu, et non pas l'homme, est le

véritable Maître de chaque être humain, de toute vie humaine. L'expérience

devint une source de profonde sagesse pour cette humble fille d'Afrique.

Dans le monde

d'aujourd'hui, d'innombrables femmes continuent d'être victimes de

représailles, même dans les sociétés modernes développées. Chez sainte

Giuseppina Bakhita, nous trouvons un brillant défenseur de la véritable

émancipation. L'histoire de sa vie inspire non pas l'acceptation passive, mais

la ferme résolution à oeuvrer de façon effective pour libérer les jeunes filles

et les femmes de l'oppression et de la violence, et pour leur restituer leur

dignité dans le plein exercice de leurs droits.

Mes pensées se tournent

vers le pays de la nouvelle Sainte, qui est déchiré par une guerre cruelle

depuis dix-sept ans, ne laissant entrevoir que peu de signes en vue d'une

solution. Au nom de l'humanité qui souffre, j'en appelle une fois de plus à

tous ceux qui sont en charge de responsabilités: ouvrez vos coeurs aux

cris de millions de victimes innocentes et empruntez le chemin de la

négociation. Avec la Communauté internationale, j'implore de ne pas continuer à

ignorer l'immense tragédie humaine. J'invite toute l'Eglise à invoquer

l'intercession de sainte Bakhita pour tous nos frères et soeurs persécutés et

esclaves, en particulier en Afrique et dans son Soudan natal, afin qu'ils

puissent connaître la réconciliation et la paix.

J'adresse enfin une parole

de salut affectueux aux Filles de la Charité canossienne, qui se réjouissent

aujourd'hui de voir élever leur Consoeur à la gloire des autels. Qu'elles

sachent tirer de l'exemple de sainte Giuseppina Bakhita un élan renouvelé en

vue d'un dévouement généreux au service de Dieu et de leur prochain.

6. Très chers frères

et soeurs, encouragés par le temps de grâce jubilaire, renouvelons la

disponibilité à nous laisser profondément purifier et sanctifier par l'Esprit.

Nous sommes attirés sur cette voie également par la Sainte dont nous rappelons

aujourd'hui la mémoire: Sainte Thérèse de l'Enfant-Jésus. A elle,

Patronne des missions, ainsi qu'aux nouveaux saints, confions aujourd'hui la

mission de l'Eglise au début du troisième millénaire.

Que Marie, Reine de tous les Saints, soutienne le chemin des chrétiens et de tous ceux qui sont dociles à l'Esprit de Dieu, afin qu'en chaque partie du monde, se diffuse la lumière du Christ Sauveur.

Sainte Catherine Marie

DREXEL

Nom: DREXEL

Prénom: Catherine (Katharine Mary)

Nom de religion: Catherine Marie (Katharine Mary)

Pays: Etats-Unis

Naissance: 26.11.1858 à Philadelphie

Mort: 03.03.1955 à Cornwells Heights (Pennsylvanie)

Etat: Religieuse - Fondatrice.

Note: Fonde en 1891 les Sœurs du Très Saint Sacrement au service des Noirs et des Indiens. Supérieure générale jusqu'en1937. Création d'une soixantaine d'écoles dont la célèbre Xavier University.

Béatification: 20.11.1988 à Rome par Jean Paul II

Canonisation: 01.10.2000 à Rome par Jean Paul II

Fête: 3 Mars

Réf. dans l’Osservatore Romano: 1988 n.47 - 2000 n.40 p.1-6 - n.41 p.7.10

Réf. dans la Documentation Catholique: 1989 p.48 - 2000

n.19 p.906-908.

Notice brève

D'une famille très riche, elle fut é mue devant la misère des Noirs américains et fonda en 1891, pour leur service et celui des Indiens, une Congrégation religieuse dont elle demeura supérieure générale, constamment réélue, jusqu'en 1937: les Sœurs du Très Saint Sacrement.

Son intense activité apostolique se traduisit par la création d'une soixantaine

d'écoles, dont la célèbre Xavier University, à la Nouvelle-Orléans, puisque

aucune université Catholique du Sud ne voulait accepter d'étudiants noirs. Elle

fonda encore des dispensaires et des centres catéchétiques.

Notice développée

Katharine Drexel naît à Philadelphie (Pennsylvanie) en 1858. Son père, Catholique, est banquier; c'est un millionnaire philanthrope.

Sa mère, protestante, meurt peu après sa naissance, et son père se remarie. Dan sa famille, on lui enseigne que les biens dont ils disposent ne sont pas seulement pour eux, mais doivent être partagés avec les moins chanceux.

Au cours d'un voyage en famille dans l'Ouest de États-Unis, elle est profondément émue par la pauvreté et les conditions dégradantes de vie des Peaux-Rouges et des Noirs (Afro-américains).

Elle utilise alors sa fortune pour financer des œuvres et aider des Missionnaires. En 1887, elle crée l'école Sainte Catherine, sa première école, à Santa Fe (Nouveau-Mexique).

Elle est bien effleurée parfois par l'idée d'une vocation religieuse, mais la pensée de prendre l'habit et de renoncer au monde à jamais lui fait horreur.

Au cours de l'un de ses voyages en Europe, elle va à Rome et expose la

situation sociale à Léon XIII en lui demandant d'envoyer des Missionnaires.

Quelle n'est pas sa surprise quand le Pape lui demande doucement: "Et

pourquoi, mon enfant, ne vous feriez-vous pas Missionnaire vous-même?"

La première réaction, après l'audience, est la colère. Sur le bateau du retour, son émotion n'est pas encore calmée. Elle projette d'en parler à l'arrivée à son directeur spirituel, l'Évêque James O'Connor.

Cet événement constitue sûrement un tournant dans la vie de la bienheureuse

Katharine. Avec un grand courage, elle place sa confiance dans Le Seigneur et

elle choisit de donner entièrement non seulement sa fortune, mais toute sa vie

au Seigneur.

En 1890, elle entre au Noviciat des Sœurs de la Miséricorde à Pittsburgh avec

l'intention de pouvoir fonder, par la suite, une Communauté Religieuse qui

aurait pour finalité l'Adoration du Saint Sacrement et l'évangélisation des

Américains de couleur et des Indiens.

En 1891, au terme d'une année de noviciat, elle prononce ses vœux simples qui

font d'elle la première Sœur et la supérieure de la Communauté du

Saint-Sacrement.

L'année suivante, les Sœurs achèvent de s'installer dans le couvent

Sainte-Elizabeth à Cornwells Heights (Pennsylvanie).

Leur spiritualité est basée sur l'union avec Le Seigneur-Eucharistie et le service des pauvres et des victimes de discriminations raciales.

Son apostolat contribue à diffuser la conscience qu'il faut combattre toutes les formes de racisme au moyen de l'éducation et des services sociaux.

En effet, dans les plantations, les gens de couleur sont très mal payés et les enfants ne sont pas scolarisés.

Elle crée une soixantaine d'écoles. Sa plus grande œuvre est l'érection en 1925, à la Nouvelle-Orléans, de la "Xavier University" pour les Noirs.

(Lorsqu'en1954 la Cour suprême abolira la séparation des races dans les écoles,

cette université ouvrira ses portes à tous les étudiants sans distinction de

couleur ou de religion.

En 1935, malade et plus que septuagénaire, une crise cardiaque l'affaiblit

beaucoup, et voilà vingt ans qu'elle n'est plus à la tête de sa Communauté.

Les 18 dernières années de sa vie, devenue presque totalement immobile, elle consacre son temps à une Prière intense.

Elle meurt en 1955, à 96 ans. Ses dernières paroles sont: "O Esprit Saint,

je voudrais être une plume, afin que votre souffle m'emporte où bon vous

semble."

Entre l'ardente jeune fille qui regimbait quelque peu contre l'aiguillon —

épisode romain qu'elle aimait à rappeler en souriant —, et la femme très âgée

livrée sans résistance au souffle de l'Esprit, quel chemin parcouru!

"Puisse son exemple aider les jeunes en particulier à reconnaître que l'on ne peut pas trouver de plus grand trésor que de suivre Le Christ avec un cœur sans partage en utilisant généreusement les dons que nous avons reçus au service des autres afin de collaborer ainsi à l'édifice d'un monde plus juste et plus fraternel." (Jean Paul II)

Canonisée le 1° Octobre 2000, place Saint-Pierre, par le Pape Saint Jean-Paul II.

Also

known as

Catherine Marie Drexel

Profile

Daughter of the extremely

wealthy railroad entrepreneurs and philanthropists Francis Anthony and Emma

(Bouvier) Drexel. She was taught from an early age to use her wealth for the

benefit of others; her parents even opened their home to the poor several

days each week. Katharine’s older sister Elizabeth founded a Pennsylvania

trade school for orphans;

her younger sister founded a liberal arts and vocational school for poor blacks

in Virginia.

Katharine nursed her mother through

a fatal three-year illness before

setting out on her own; Emma died in 1883.

Interested in the

condition of Native Americans, during an audience in 1887,

Katharine asked Pope Leo

XIII to send more missionaries to Wyoming for

her friend, Bishop James

O’Connor. The pope replied,

“Why don’t you become a missionary?”

She visited the Dakotas,

met the Sioux chief, and began her systematic aid to Indian missions,

eventually spending millions of the family fortune. Entered the novitiate of

the Sisters of Mercy. Founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament

for Indians and Colored, now known simply as the Sisters of the Blessed

Sacrament in Santa Fe, New

Mexico, USA in 1891.

Advised by Mother Frances

Cabrini on getting the Order’s rule approved in Rome. She received the approval

in 1913.

By 1942 she

had a system of black Catholic schools

in 13 states, 40 mission centers, 23 rural schools,

50 Indian missions,

and Xavier University in New

Orleans, Louisiana,

the first United

States university for

blacks. Segregationists harassed her work. Following a heart

attack, she spent her last twenty years in prayer and

meditation. Her shrine at

the mother-house was declared a National Shrine in 2008.

Born

26 November 1858 at

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

3 March 1955 of

natural causes at the mother-house of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament,

1663 Bristol Pike, Bensalem, Pennsylvania, USA 19020-8502

interred at

the National Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel in Bensalem

the Shrine closed to the

general public on 30

December 2017

relics moved

to the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in

the summer of 2018 and

open for public veneration in September 2018

26 January 1987 by Pope John

Paul II

20

November 1988 by Pope John

Paul II

1 October 2000 at Rome, Italy by Pope John

Paul II

Additional

Information

other

sites in english

Catholic

Fire: Katharine Drexel, Model of Charity

Catholic Fire: Novena

Catholic News Agency: Historically Black Catholic

University Founded by a Saint

Regina

Magazine: American Millionaire Saint

Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

Readings

The patient and humble

endurance of the cross whatever nature it may be is the highest work we have to

do. – Mother Katharine Drexel

Oh, how far I am at 84

years of age from being an image of Jesus in his sacred life on earth! –

Mother Katharine Drexel

MLA

Citation

“Saint Katharine

Drexel“. CatholicSaints.Info. 29 June 2023. Web. 18 February 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-katharine-drexel/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-katharine-drexel/

Cathedral

Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Completed

in 1864; architects John Notman and Napoleon Eugene Henry Charles Le Brun.

KATHARINE DREXEL

(1858-1955)

Born in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, in the United States of America, on November 26, 1858, Katharine

Drexel was the second daughter of Francis Anthony Drexel and Hannah Langstroth.

Her father was a well known banker and philanthropist. Both parents instilled

in their daughters the idea that their wealth was simply loaned to them and was

to be shared with others.

When the family took a

trip to the Western part of the United States, Katharine, as a young woman, saw

the plight and destitution of the native Indian-Americans. This experience

aroused her desire to do something specific to help alleviate their condition.

This was the beginning of her lifelong personal and financial support of

numerous missions and missionaries in the United States. The first school she

established was St. Catherine Indian School in Santa Fe, New Mexico (1887).

Later, when visiting Pope

Leo XIII in Rome, and asking him for missionaries to staff some of the Indian

missions that she as a lay person was financing, she was surprised to hear the

Pope suggest that she become a missionary herself. After consultation with her

spiritual director, Bishop James O'Connor, she made the decision to give

herself totally to God, along with her inheritance, through service to American

Indians and Afro-Americans.

Her wealth was now

transformed into a poverty of spirit that became a daily constant in a life

supported only by the bare necessities. On February 12, 1891, she professed her

first vows as a religious, founding the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament whose

dedication would be to share the message of the Gospel and the life of the

Eucharist among American Indians and Afro-Americans.

Always a woman of intense

prayer, Katharine found in the Eucharist the source of her love for the poor

and oppressed and of her concern to reach out to combat the effects of racism.

Knowing that many Afro-Americans were far from free, still living in

substandard conditions as sharecroppers or underpaid menials, denied education

and constitutional rights enjoyed by others, she felt a compassionate urgency

to help change racial attitudes in the United States.

The plantation at that

time was an entrenched social institutionin which the coloured people continued

to be victims of oppression. This was a deep affront to Katharine's sense of

justice. The need for quality education loomed before her, and she discussed

this need with some who shared her concern about the inequality of education

for Afro-Americans in the cities. Restrictions of the law also prevented them

in the rural South from obtaining a basic education.

Founding and staffing

schools for both Native Americans and Afro-Americans throughout the country

became a priority for Katharine and her congregation. During her lifetime, she

opened, staffed and directly supported nearly 60 schools and missions,

especially in the West and Southwest United States. Her crowning educational

focus was the establishment in 1925 of Xavier University of Louisiana, the only

predominantly Afro-American Catholic institution of higher learning in the

United States. Religious education, social service, visiting in homes, in

hospitals and in prisons were also included in the ministries of Katharine and

the Sisters.

In her quiet way,

Katharine combined prayerful and total dependence on Divine Providence with

determined activism. Her joyous incisiveness, attuned to the Holy Spirit,

penetrated obstacles and facilitated her advances for social justice. Through

the prophetic witness of Katharine Drexel's initiative, the Church in the

United States was enabled to become aware of the grave domestic need for an

apostolate among Native Americans and Afro-Americans. She did not hesitate to

speak out against injustice, taking a public stance when racial discrimination

was in evidence.

For the last 18 years of

her life she was rendered almost completely immobile because of a serious

illness. During these years she gave herself to a life of adoration and

contemplation as she had desired from early childhood. She died on March 3,

1955.

Katharine left a

four-fold dynamic legacy to her Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, who continue

her apostolate today, and indeed to all peoples:

– her love for the

Eucharist, her spirit of prayer, and her Eucharistic perspective on the unity

of all peoples;

– her undaunted spirit of

courageous initiative in addressing social iniquities among minorities — one

hundred years before such concern aroused public interest in the United States;

– her belief in the

importance of quality education for all, and her efforts to achieve it;

– her total giving of

self, of her inheritance and all material goods in selfless service of the

victims of injustice.

Katharine Drexel

was beatified by Pope John Paul II on November 20, 1980.

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20001001_katharine-drexel_en.html

Saint

Stephen, Martyr Roman Catholic Church (Chesapeake, Virginia) - stained glass,

St. Katharine Drexel

St. Katharine Drexel

St. Katharine Drexel was

born in Philadelphia in 1858. She had an excellent education and traveled

widely. As a rich girl, she had a grand debut into society. But when she nursed

her stepmother through a three-year terminal illness, she saw that all the Drexel

money could not buy safety from pain or death, and her life took a profound

turn.

She had always been

interested in the plight of the Indians, having been appalled by reading Helen

Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor. While on a European tour, she met Pope

Leo XIII and asked him to send more missionaries to Wyoming for her friend

Bishop James O’Connor. The pope replied, “Why don’t you become a missionary?”

His answer shocked her into considering new possibilities.

Back home, she visited

the Dakotas, met the Sioux leader Red Cloud and began her systematic aid to

Indian missions.

She could easily have married. But after much

discussion with Bishop O’Connor, she wrote in 1889, “The feast of St. Joseph

brought me the grace to give the remainder of my life to the Indians and the

Colored.” Newspaper headlines screamed “Gives Up Seven Million!”

After three

and a half years of training, she and her first band of nuns (Sisters of the

Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored) opened a boarding school in Santa

Fe. A string of foundations followed.

By 1942 she had a system

of black Catholic schools in 13 states, plus 40 mission centers and 23 rural

schools. Segregationists harassed her work, even burning a school in

Pennsylvania. In all, she established 50 missions for Native Americans in 16

states.

Two saints met when she was advised by Mother Cabrini about the

“politics” of getting her Order’s Rule approved in Rome. Her crowning

achievement was the founding of Xavier University in New Orleans, the first

Catholic university in the United States for African Americans.

At 77, she suffered a

heart attack and was forced to retire. Apparently her life was over. But now

came almost 20 years of quiet, intense prayer from a small room overlooking the

sanctuary. Small notebooks and slips of paper record her various prayers,

ceaseless aspirations and meditation. She died at 96 and was canonized in 2000.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/katharine-drexel/

The Lansford Historic District in is

a national historic district located at Lansford Carbon County,

Pennsylvania. Our Lady of the Angels Academy on left, St. Katharine Drexel

Parish in center, Trinity Lutheran Church on right.

Saint Katharine Drexel

Virgin and Foundress

L'Osservatore Romano

Feast: March 3

Born in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, U.S.A. on 26 November 1858, Katharine was the second daughter of

Francis Anthony Drexel, a wealthy banker, and his wife, Hannah Jane. The latter

died a month after Katharine's birth, and two years later her father married

Emma Bouvier, who was a devoted mother, not only to her own daughter Louisa

(born 1862), but also to her two step-daughters. Both parents instilled into

the children by word and example that their wealth was simply loaned to them

and was to be shared with others.

Katharine was educated

privately at home; she travelled widely in the United States and in Europe.

Early in life she became aware of the plight of the Native Americans and the

Blacks; when she inherited a vast fortune from her father and step-mother, she

resolved to devote her wealth to helping these disadvantaged people. In 1885

she established a school for Native Americans at Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Later, during an audience

with Pope Leo XIII, she asked him to recommend a religious congregation to

staff the institutions which she was financing. The Pope suggested that she

herself become a missionary, so in 1889 she began her training in religious

life with the Sisters of Mercy at Pittsburgh.

In 1891, with a few

companions, Mother Katharine founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for

Indians and Colored People. The title of the community summed up the two great

driving forces in her life—devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and love for the

most deprived people in her country.

Requests for help reached

Mother Katharine from various parts of the United States. During her lifetime,

approximately 60 schools were opened by her congregation. The most famous

foundation was made in 1915; it was Xavier University, New Orleans, the first

such institution for Black people in the United States.

In 1935 Mother Katharine

suffered a heart attack, and in 1937 she relinquished the office of superior

general. Though gradually becoming more infirm, she was able to devote her last

years to Eucharistic adoration, and so fulfil her life’s desire. She died at

the age of 96 at Cornwell Heights, Pennsylvania, on 3 March 1955. Her cause for

beatification was introduced in 1966; she was declared Venerable by Pope John

Paul II on 26 January 1987, by whom she was also beatified on 20 November 1988.

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano

Weekly Edition in English

21 November 1988, page 2

SOURCE : http://www.ewtn.com/library/mary/drexel.htm

SAINT KATHARINE DREXEL

Saint Katharine Drexel

was born Catherine Marie, second daughter of Francis and Hannah Drexel of

Philadelphia on November 26, 1858. Her mother died about a month after her

birth. In1860 her father, a well-known banker and philanthropist, married Emma

Bouvier. Devout Catholics, they gave a great deal of their time and money to

philanthropic activities. Catherine and her two sisters were educated privately

and were encouraged to conduct a Sunday school for children of the employees of

their family’s summer home. While conducting these sessions, Catherine

developed a devotion to St. Frances of Assisi and she vowed that, like St.

Frances, she would one day give all she had to the poor. Both parents instilled

in their children the idea that their wealth was simply loaned to them and was

meant to be shared with others, especially the poor.

Catherine’s life was

jarred by the protracted illness, and then death in 1883, of her step-mother,

to whom she was devoted; two years later, her father died. At that time she

seriously considered entering a convent but was persuaded by her religious

counselor, Bishop James O’Connor of Omaha, NE, not to make a hasty decision but

rather “wait and pray.” At the time of his death, her father left the largest

fortune recorded in Philadelphia at that time. His three daughters received

bequests that provided them with an extremely generous income for life. The

rest of his fortune was donated to his favorite charities. The sisters

continued to use their great wealth to respond to the many requests for aid

they received from churchmen throughout the country.

In 1885, Catherine and

her sisters traveled to the Western part of the United States, visiting Indian

reservations. Having seen first-hand the poverty and suffering there, she began

to build schools, supply food and clothing, and provide salaries for teachers

on the reservations. She was also able to find priests to serve the spiritual

needs of the people. In 1887 she established her first boarding school, St.

Catherine Indian School, in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

That same year, Catherine

visited Rome to request Pope Leo XIII to provide missionaries to staff the

schools she was funding. The Holy Father responded by suggesting that Catherine

become a missionary herself. On February 12, 1891, in an arrangement with

Bishop James O’Connor, Catherine began a novitiate with the Sisters of Mercy in

Pittsburgh, with the understanding that in two years she would found her own order,

the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People; she would,

she vowed, “be the mother and servant of these races.”

In late 1889 she received

the religious habit and the name of Sister Mary Katharine. Thirteen companions

joined her as the first Sisters of the new order. The motherhouse of the new

order was established at St. Elizabeth’s Convent, Cornwells Height (Bensalem

Township), PA. Mother Katharine, as she was now called, made the decision not

to admit black women in part because laws in some Southern states would force

them to house black and white nuns in segregated convents, and in part to avoid

drawing worthy candidates away from two all black religious orders already

established.

Founding and staffing

schools for both Native and African Americans throughout the country became a

priority for Mother Katharine and her congregation. In 1894 she purchased 1,600

acres in Rock Castle, Virginia, on which to build a boarding school for black

girls. The school opened in 1899 as St. Francis de Sales School. Nearby was St.

Emma’s built in 1895 by her sister Louise. St. Emma’s was a boarding school of

black boys. Both schools concentrated on vocational arts in the belief that

this was the best way at the time to provide training for young blacks to

become economically independent.

Soon thereafter, a school

for Pueblo children was established in New Mexico. Mother Katharine made it a

priority to visit all the schools she helped.

In 1901, Mother Katharine

had made a trip to visit St. Francis de Sales School and to discuss setting up

small catechetical centers in nearby places in Virginia. This necessitated a

considerable amount of train travel. Once in a coach between Richmond and

Lynchburg, the train stopped at a small station marked Columbia. She noticed a

gilt cross gleaming through the trees and said to her companion, Mother

Mercedes, “Do you think that is a Catholic Chapel?” Mother Mercedes replied

that she did not think so, as she had been told there was no Mass celebrated

between Richmond and Lynchburg. Mother Katharine arranged to visit the small

private Wakeham Chapel beneath the cross she had spotted and discovered that no

Masses had been held in years and there was only an elderly caretaker in

residence. Mother Katharine told the caretaker that although she could not

promise that Mass would be said in the Chapel, she would send a few of her

Sisters from St. Francis de Sales there each week to teach catechism She

fulfilled that promise that same year and soon arranged for Josephite Fathers

to say Mass there. The Wakeham Chapel unofficially became a Public Chapel,

known as St. Joseph’s, which is still in existence. Her Sisters remained part

of St. Joseph’s until 1971.

In 1915 Louisiana relocated

a black college, Southern University, out of New Orleans. Mother Katharine

purchased the vacant campus and reopened the school as Xavier College (now

Xavier University). The primary mission of the college was to train lay

teachers who would then staff schools for black children in rural Louisiana.

Xavier was the first and only Catholic college for African-Americans and a

pioneer in co-education.

In 1922, Fr. Sylvester

Eisenmann, a Benedictine priest, visited Mother Katharine at the motherhouse in

Pennsylvania to beg for assistance. He did not want financial aid but rather a

teacher for his small school in Marty, SD, near Yankton. Touched to tears by

his story, Mother Katharine nevertheless felt she could not spare any of her

Sisters to go and teach school. She did, however, promise to pray about his

request overnight. The next day, she reversed her decision. Within two months’

time, Mother Katharine and three of the Sisters arrived at the St. Paul Mission

in Marty to begin teaching. Within a decade more than 400 Native American

children were being educated at St. Paul’s Mission by the 23 Sisters of the

Blessed Sacrament.

Having taken a vow of

poverty, Mother Katharine lived the rest of her life with extreme frugality,

wearing a single pair of shoes for ten years and using her pencils down to the

erasers. During the same time, her income from her father’s trust amounted to

more than $1,000 a day.

From the age of 33 until

her death, she dedicated her life and personal fortune of $20 million to her

work. She was a constant worker, personally reviewing each request for aid,

often indicating her decision on a note on the letter of inquiry. She traveled

tirelessly. Her strongest priority was the creation of church buildings and

schools. No believer in segregation, she recognized that in her time a

segregated church or school was often the most that could be hoped for. She

generally confined her response to pleas for aid to buying land, erecting

buildings, as well as occasionally paying salaries. She had neither the time

nor inclination to supervise. One result of her practice was that she almost

completely avoided conflict with the priests and bishops in charges of the

missions she sponsored. By 1942 she had established a system of 40 mission

centers and 23 rural schools in 13 states.

In 1935 Mother Katharine

suffered a severe heart attack and was confined primarily to a wheelchair. For

the next twenty years lived her life in prayerful retirement at St. Elizabeth’s

Convent. She died there on March 3, 1955 at the age of 96. At the time of her

death 501 members of her order were teaching in 63 schools and missions in 21

states, including Virginia.

Mother Katharine’s

dedication inspired her Sisters and admirers to begin the cause of her

sainthood less than 10 years after her death. In 1987, she was credited with

the miraculous healing of a man’s deaf ear. Pope John Paul II bestowed upon her

the title “Blessed.” In 1999 her intervention was declared to have resulted in

the cure of deafness in a 17-month-old child. She was canonized “Saint

Katharine Drexel” on October 1, 2000. She is only the second American-born

saint.

Our thanks to the Sisters

of the Blessed Sacrament for information about St. Katharine. Learn more at

their website: www.katharinedrexel.org.)

SOURCE : http://www.katharinedrexelcc.org/?page_id=80

Katherine Drexel: A Saint

for Modern Americans

by Br. Lawrence Mary

M.I.C.M., Tert. January 31, 2006

On October 1, 2000, Pope

John Paul II solemnly decreed that Katharine Drexel, Founder of the Sisters of

the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, is a saint of the

Catholic Church. A third-generation, thoroughly “Red-blooded” American had been

added to the rolls of the canonized saints.

First, let us briefly

summarize the significant events in the life of our saint. Katharine Drexel,

the second of three sisters, Elizabeth, Katharine and Louise, was born in 1858.

Her father, Francis, was a Catholic; her natural mother, Hannah Langsroth Drexel,

a Baptist Quaker, died soon after giving birth to Katharine. Two years later,

her father married a Catholic, Emma Bouvier, who gave birth to a third

daughter, Louise, in 1863. In 1887, in a private audience with Pope Leo XIII,

Katharine pleaded for priests to serve the American Indians. His fateful reply

was that she, herself, should become that missionary. At the end of 1888, at

the age of thirty, she received permission from her spiritual director to

become a religious and joined the Sisters of Mercy for her training. In 1891,

she founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Negroes.

(Intending to extend the focus of her order, she later changed the word

“Negroes” to “Colored People.”) The order grew to include sixty schools and

missions while the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament eventually numbered more

than five hundred. In 1935, when she was seventy-seven years old, St. Katharine

suffered a severe heart attack and until her death in 1955 lived in prayerful

retirement. Her cause was opened in 1964 and in 2000 Pope John Paul II

canonized her.

A Privileged American

Catholic Childhood

If anyone could be

described as having been “born with a golden spoon in her mouth,” it would have

been Katharine Drexel and her sisters, Elizabeth and Louise. Few American girls

would have had more of an excuse to be distracted by the world and what it has

to offer than these daughters of one of the most prominent and wealthy families

in the United States. Their father, Francis Drexel, was an outstanding banker

and exchange broker — a founding partner in what was known at the time as

Drexel, Morgan and Company.

Francis Drexel and his

second wife, Emma (Bouvier), were more than devout Catholics. They were

determined to instill truly Catholic teachings and norms of behavior into their

children. They understood the principle, later summed up by the great Fr.

Leonard Feeney, that “Catholicism is a manner.” Thus, from an early age, Emma

trained her daughters in the dispensing of alms and performing other works of Catholic

Charity. She had the charitable heart of a great Catholic woman who wanted her

children to capture the spirit of true Catholic Charity and learn how to give

alms prudently — in sharp contrast to other wealthy Americans of the day who

engaged in self-serving, pompous philanthropy.

Convinced that a proper

education and formation are essential ingredients of a Catholic manner, Francis

and Emma retained two devout Catholic women, both of whom would have a major

influence on the Drexel girls. Johanna Ryan, their trusted servant, was from

Ireland, where she had tried to become a Sister of the Sacred Heart but was

unable to continue because of her health. Although a simple person, she was

unflinching in her defense of the Faith and taught the girls of the necessity

of the Catholic Faith in order for one to be saved. The absolute sincerity of

Johanna’s faith was somewhat indecorously demonstrated during an audience with

Pope Pius IX in 1875. After the family had visited a few moments with the Holy

Father, she fell to the floor, threw her arms around his knees and exclaimed,

“Holy Father — praise God and His Blessed Mother — my eyes have seen our dear

Lord, Himself!”

A more reserved Miss Mary

Cassidy, the governess, was also from Ireland. The Drexels hired her after a

careful search for someone that was not only a devout Catholic but had a deep

and broad education with emphasis on literature and philosophy. As part of Miss

Cassidy’s tutoring program for the girls, she required regular compositions and

lengthy letters while the family traveled. Katharine remained a prodigious

letter writer for the rest of her life. We know a great deal about her

intellectual, emotional and spiritual development from the thousands of her

letters, memos and personal notes that have been preserved in the archives of

the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

Several qualities of

Katharine’s life are indicative of the road to sanctity she was to follow. The

first was her intense love of the Blessed Sacrament which manifested itself

when she was a little girl as a fervent desire to make her First Holy Communion.

In a letter to her mother, written in 1867, she said, “Dear Mama, I am going to

make my First Communion and you will see how I will try to be good. Let me make

it in May, the most beautiful of all the months.”

Katharine’s love for Our

Lord in the Blessed Sacrament was to grow in intensity throughout her life.

After she formed her order, she took great pleasure in building a tabernacle in

a location where the Blessed Sacrament had never been adored before. Often, at

night, long after everyone else had retired for the evening, the sacristan

would find her in the darkened church, kneeling with arms outstretched in front

of the Blessed Sacrament or the Crucifix. Her concentration was so intense that

she remained completely unaware that she was being observed. Throughout her

life she meditated before and upon Jesus present in the Tabernacle and recorded

many of her reflections and prayers. One of her later notes reads as follows:

“Ah, Lord, it is but too

true, YOU ARE NOT LOVED! Shall we not strive by every means in our power to

make you known and loved? Shall we not try to pay many an extra visit to our

dearest Friend, ever present in the Blessed Sacrament, ever living to make

intercession for us? And may this prayer, dearest Lord, be on our lips when we

bow down in lowly adoration in your sacramental presence: ‘Sacred Heart of

Jesus, you love! O Sacred Heart of Jesus, you are not loved! O would that you

were loved!’ Our Lady, open your heart to me, your child. Teach me to know your

Son intimately, to love him ardently, and to follow him closely.”

The salvation of souls,

especially those souls that were the most neglected and forgotten, was the

great quest of St. Katharine. Even as a little girl, she and her sisters knew

that only Catholics are saved. As may be expected in “pluralistic” America,

this proper Catholic belief led to several embarrassing incidents for Mr. and

Mrs. Drexel, who, although they were devout Catholics, appear to have been

somewhat weak in this area. As mentioned earlier, St. Katharine’s natural

mother, Hanna Langsroth, as well as her grandparents, Piscator and Eliza

Langsroth, were Protestants. One day, during a visit at the Langsroth’s,

Katharine’s older sister, Elizabeth, said to her grandmother, “Oh, Grandma, I

am so sorry for you because you can never go to heaven.”

“And, why cannot

Grandmother go to heaven?” Mrs. Langsroth asked.

With the simplicity and

purity of a truly Catholic child, Elizabeth replied, “You are a Protestant and

Protestants never go to heaven.”

On another occasion, a

friend of Grandma Langsroth’s, a Protestant minister, was visiting at the same

time as were Elizabeth and Katharine. As the girls relayed the story in later

years, when Mrs. Langsroth asked the minister to say grace before the meal, it

caused them to go into a kind of panic. The girls decided to hold up their

rosaries in full view during the meal prayer as a clear statement of their

Catholicism. It appears that their feistiness for the Faith was more the result

of the instruction of Johanna, the family servant and staunch Irish Catholic,

than of the direct influence of Mr. and Mrs. Drexel. In fact, both of these

early defenses of the faith caused some embarrassment for Francis and Emma.

Sadly, they decided to smooth the ruffled feathers of the errant grandmother

rather than support the innocent defense of the Faith provided by their

children.

Despite this weakness in

the belief of their parents, the Drexel daughters recognized the necessity of

sacramental Baptism for salvation. When the oldest sister, Elizabeth, was

married and in danger of losing a baby, she wrote to Katharine, “My pious and

good little religious sister, Katharine, we count on your prayer to bring ours

safely to the waters of Baptism and beyond them through a good and useful life

to Heaven.” Later Mother Katharine would record this plea to the Mother of God,

“O Mary, make me endeavor, by all the means in my power, to extend the kingdom

of your Divine Son and offer incessantly my prayers for the conversion of those

who are yet in darkness or estranged from His fold.”

Death and

the Awakening of a Vocation

In 1883, when Katharine

was twenty-four years old, her mother died from a very painful and lingering

cancer. Katharine had been her nurse during the illness and was profoundly

moved by her mother’s resignation to the Will of God and received deep

realizations about the evil of Original Sin. It was at her mother’s bedside

that thoughts of a religious vocation came to Katharine repeatedly and

forcibly. Two years later, her father died. It was a time of profound soul

searching which resulted in growth in the spiritual life and the serious

examination of her vocation. In particular, she pondered whether or not she

would stay in the world, knowing that its allurements lay at her feet, or

whether she would pursue a life of austerity and voluntary poverty.

Some years before her

mother’s death, at the age of fourteen, she had taken as her spiritual director

Fr. James O’Connor, the local parish priest. A few years later, he was

consecrated Bishop and moved to Omaha, Nebraska. They began a lengthy

correspondence on the topic of her vocation, the plight of the Indians under

his care and many other spiritual matters. Because most of their letters have

been preserved, we have a unique opportunity to penetrate into Katherine’s

spiritual development. The graces gained through the means of a good spiritual

director cannot be overestimated and, as is clear from his letters, Bishop

O’Connor was a holy and intelligent guide for our saint. It was Bishop O’Connor

who, for several years, challenged her initial advancement towards a religious

vocation when he detected remnants of worldliness, impulsiveness, vanity or

scrupulosity. Katharine’s natural inclination was to become a contemplative.

Bishop O’Connor, as an insightful spiritual father, knew that this was not the

appropriate venue to develop her spirituality and to utilize her talents and

education. It was he who encouraged and guided her towards the financial

support of the Indian missions, an endeavor which would eventually be

incorporated into her new religious order.

Mrs. Drexel had taught

her daughters of their obligations to the less fortunate and how to engage in

works of Catholic Charity appropriate for a family who was very blessed by God.

From their very early years they assisted their mother while she thrice weekly

threw open the doors of her home to assist the poor and needy and donated money

for rent, medicine, food, clothing and other necessary items. In this manner,

they donated over twenty thousand dollars per year. Mrs. Drexel taught them how

to dispense alms with prudence and justice. For example, she employed a

well-qualified person to investigate and ascertain the need where assistance

was to be given.

In 1884, during their

first trip out West, the family visited Montana, where she saw first hand the

poverty and destitution of the Indian missions. During a conversation with the

priest in charge of one of the missions, she asked what she could do to help.

He told her that the small, primitive chapel needed a statue. Before she left,

she used her own personal money and purchased a beautiful statue of Our Lady

from a catalog and had it shipped to the mission. When she informed her father

of what she had done, instead of reprimanding her for her extravagance, he put

his arm around her and, with great tenderness, told her how glad he was for her

generosity. This began her life-long commitment of personal support of the

Indian missions. Later in her life, Katharine recalled when, as a young

student, she studied the history of America and learned of Christopher

Columbus, she was convinced the only reason for his voyage was to convert the

Indians.

It was not until 1888,

nearly two years after her providential personal audience with Pope Leo XIII,

that Bishop O’Connor dropped his opposition to her desires to pursue a

religious vocation. During that audience, Katharine dropped to her k nees and

pleaded for missionaries for Bishop O’Connor’s Indians. To her astonishment,

His Holiness responded, “Why not, my child, yourself become a missionary?” The

shock and instant realization of the implications of his comment made her

physically ill. Influenced by the Holy Father’s words, Bishop O’Connor guided

her continuing support of the Indian missions and used it as a preparation for

the work of the religious community she would eventually found. For another two

years, he strongly encouraged Katharine to probe the depths of her

spirituality. He assisted her to continually clarify her thoughts and

aspirations until she had attained the vision and depth to pursue the great

work that would eventually lie before her. For the present, he encouraged her

to remain in the world, assist Indian and other missions, and work for the

conversion of her non-Catholic family members.

As stated before, the

guidance of a holy and prudent spiritual director is of immense value. From one

of Bishop O’Connor’s letters, here is a small sample of the advice he gave

Katharine when she was twenty-five years old:

“Most of the reasons you

give, in your paper, for and against your entering the states considered, are

impersonal, that is, abstract and general. These are very well as far as they

go, in settling one’s vocation, but additional and personal reasons

are necessary to decide it. The relative merits of the two states cannot be in

question. It is of faith that the religious state is, beyond measure, the more

perfect. It must be admitted, too, that in both, dangers and difficulties are

to be encountered and overcome. One of these states is for the few, the other,

for the many85.

“You give positive

personal reasons for not embracing the religious state. The first — the

difficulty you would find in separation from your family, does not merit much

consideration, as that would have to be overcome, in any case. The second —

your dislike for community life is a very serious one, and if it continues to

weigh with you, you should give up all thought of religion. You would meet many

perfect souls there, but some, even among superiors, who would be far from

perfect. To be in constant communion with these, to be obliged to obey them, is

the greatest cross of the religious life. Yet to this, all who ‘would be

perfect,’ must be prepared to submit. Indeed, toleration of their faults and

shortcomings is, in the Divine economy, one of the indispensable means of

acquiring perfection. The same must be said of ‘the privations and poverty,’

and the monotony of the religious life, to which you allude. If you do not feel

within you the courage, with God’s help, to bear them, for the sake of Him to

whom they lead, go no further in your examination. Thousands have borne such

things and have been sanctified by them, but only such as had foreseen them,

and resolved, not rashly, to endure them for Our Lord.”

Finally, at the end of

1888, when Katharine was thirty years old and her desire to enter the religious

life became impossible to restrain, he gave his enthusiastic permission for her

to pursue a religious vocation. Although her natural inclination was to join a

cloistered order, Bishop O’Connor led her to the realization that the needs of

the Indian and other missions were such that she would have to found a new

order. This new religious order would use her wealth and talents to serve these

desperate peoples in a manner peculiar to the United States. First, she would

enter the convent of the Sisters of Mercy. There, Bishop O’Connor arranged that

she be trained for the purpose of founding of her own religious order — an

order that would eventually work for the conversion of the most neglected of

all Americans: the Indians and the Negroes. One of Bishop O’Connor’s greatest

challenges as her spiritual director was to help Katharine to exercise careful

prudence over her fortune once she entered the religious life. At first she

wanted to divest herself of everything in order to practice holy poverty. She

preferred to have the American hierarchy disburse these funds to the missions

rather than herself. He wisely saw the need for her to retain control over

these funds in order to ensure the success of the missionary activity of her

new order, and he convinced her to refrain from formally divesting herself of

her inheritance. In fact, without these funds her new order could never have

accomplished the remarkable achievements we are about to describe.

The Birth of a Religious

Order

Although her inclinations

were evident for many years, Katharine was what is referred to today as a “late

vocation.” She was thirty years old when she entered the convent of the Sisters

of Mercy as a postulant. Her years of excellent schooling, practical training

and spiritual growth would be refined by the discipline of the religious life.

She now began to deepen her contemplative spirit. Her own writings and those

who knew her attest to the fact that Katharine never fell prey to the heresy of

“Americanism.” This error, which was spreading across our country at the time,

divided the active from the passive virtues and overemphasized the active life

— good works and activities — to the detriment of the meditative prayer life.

She had the deep realization that the apostolic life must spring forth from the

spirit of contemplative prayer life or it would never produce good fruits. Love

of the Blessed Sacrament and the desire to share this love with others was the

source of her missionary zeal.

Prior to her becoming a

religious, Katharine and her sisters were major financial supporters of the

Indian missions. As knowledgeable Catholics are aware, since the Revolutionary

War, the United States Government has been in the hands of the Protestants. The

policy towards the Indians was one of continual displacement. When the Indians

rebelled and uprisings occurred, they were subdued and moved. In 1870,

President Grant made an attempt to rectify the injustices perpetrated by the

government and initiated his “Peace Policy.” He assigned the Indian agencies to

the religious groups who had established prior missions in the various tribes

and groups.

Although Grant’s

intention was good, things did not work out well in practice. Of the total

seventy-two Indian missions, thirty-eight were originally Catholic. Under the

auspices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the government gave over to

Protestant control thirty of the Catholic missions, containing eighty thousand

Catholic Indians. This was a direct violation of President Grant’s official

policy statement, which had specified that the missions were to remain under

the control of the missionaries who instituted them. Without money and

missionaries many of the Indians were in grave danger of losing their Faith and

drifting into various forms of heresy or apostasy. They also suffered many

injustices at the hands of their new Protestant masters. The religious and

Indian representatives wrote strong letters to the Secretary of the Interior to

protest this direct violation of the policy. Their letters were never answered.

In addition to the

failure of Grant’s well-intentioned program, in 1881, Garfield was elected and

was openly opposed to the Peace Plan. Garfield’s assassination soon after his

election proved no reprieve either, for Vice President Arthur appointed Henry

M. Teller — a man hostile to Grant’s policy — as the new Secretary of the

Interior. Teller terminated the arrangement whereby religious associations

selected Indian bureau agents. He simply ignored all appeals and requests to

correct the many injustices replying, “I do not know what you mean by the Peace

Policy of the Government.”

In 1885, following the

collapse of Grant’s Plan and prior to Katharine’s entrance into the religious

life, two of the most intrepid Catholic missionaries traveled across the

country to seek a meeting with Katharine and her sisters, Elizabeth and Louise.

The two were Bishop Martin Marty, O.S.B., Vicar Apostolic of Northern

Minnesota, and Reverend Joseph Stephan, Director of the Bureau of Catholic

Indian Missions. Both were zealous, experienced missionaries who were deeply

concerned over the preservation of the Faith of the Indians in the formerly

Catholic territories. They appealed for help to educate the Indians. Schools

were desperately needed. They described the abject poverty and horrible

conditions and explained that the salvation of many souls hung in the balance.

With the assistance of the Drexels, many Indians could be preserved in the

Faith. Katharine and her sisters were deeply moved by their appeal and

generously responded. By 1907 they had donated over 1.5 million dollars to the

Indian Missions in addition to all of their other works of Charity.

The association with

Father Stephan would last until the end of his life. He and other selfless

missionaries would open Katharine’s eyes to the need for qualified religious to

teach and work among the Indians. Money was not enough; workers were

desperately needed as well. The priests, along with their bishops, sent appeals

for aid to the Drexel sisters so that these souls would remain Catholic.

Eventually, her deep realization of the need for qualified, selfless and stable

religious became the germ of the new order she was to found — The Sisters of

the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Negroes. The goal of the order would be

education, both in the Faith and in the trades that would be most useful for

solid employment and conducting family life. Schools were to be built and

staffed. Tabernacles would be established and the Blessed Sacrament adored

where it had never been worshiped before.

Bishop O’Connor guided

her through these years of decision and the formation of the new order. His

influence was such that she referred to the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament as

Bishop O’Connor’s order. He had helped her prudently to fund and care for

various Indian missions. He was a keen observer of human nature and realized

that, if Katharine were seen as a source of limitless funds, other donors would

not step forward. He advised her to donate as secretly as possible, to fund

only the start of a new program, and immediately to locate other donors once it

had been established.

In 1890, just a year

before the official establishment of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament,

Bishop O’Connor passed to his eternal reward. Katharine was devastated and

began to despair of her ability to carry on with the founding of the new

religious order. She felt completely abandoned. The Archbishop of Philadelphia,

Patrick Ryan, who had been an intimate friend of Bishop O’Connor, wrote her a

letter in which he promised to visit after he had celebrated the Requiem High

Mass for Bishop O’Connor. She had met him on a number of occasions since his

installation as Archbishop in 1884, and they were on very friendly terms. In the

past, he had written her a number of letters with spiritual advice and had, on

several occasions, celebrated Mass in the Drexel home. During the promised

meeting, she confided her profound distress and sense of inadequacy. He

replied, “If I share the burden with you, if I help you, can you go on?” This

was the beginning of a long and fruitful spiritual relationship — one that

would last for the next twenty years. He truly became her father in God.

Archbishop Ryan knew the minds of Bishop O’Connor and Katharine as well as the

needs of the Catholic missions in America. His guidance proved most

providential for the Catholics in this country and for the growth in personal

sanctity of our saint.

Shortly after this

meeting, in one of Archbishop Ryan’s first letters to Katharine, he advised her

to acquire a deep interior spirit and warned her that the success of her future

activities would depend on that spirit. Katharine took his words very much to

heart. She had received similar advice from Bishop O’Connor and had already

begun to cultivate a life of reflection and prayer from which she would draw

the strength to live a very active religious life. This growth in her spiritual

life was one of the remarkable traits which distinguished her from the “social

activists” of the day. The Paulists and other contemporaneous American

Catholics were stressing the active virtues to the exclusion of the

contemplative. In his letter, Testem Benevolentiae , Pope Leo XIII

condemned the idea as part of a heresy named “Americanism.” Katharine was

neither a theological nor a practical Americanist.

Reaping the Harvest

Finally, on February 12,

1891, Katharine made her profession as the first Sister of the Blessed

Sacrament for Indians and Colored People. The initial vows of poverty, chastity

and obedience were for five years, to which she added another vow: “To be the

mother and servant of the Indian and Negro races according to the rule of the

Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament; and not to undertake any work which would

lead to the neglect or abandonment of the Indian and Colored races.” She

desired to unite herself with the great missionaries of the age — to continue

and enhance their work of converting the nation.

Although Katharine was

willing to give up everything completely, Archbishop Ryan made it clear that

her vow of poverty was not to include a complete renunciation of her

inheritance. He advised her, “As to the mode of holding the property, this

should be only until the Motherhouse is completed and you have entered

it. Afterwards , the property should be in the name of yourself and a

few of the sisters, as in the case of the Good Shepherd and other institutions.

But there is time enough for this consideration.” In other words, it was

necessary that she retain control of the finances of her new order, while

maintaining her spirit of poverty. Fortunately, she was most obedient to her

spiritual advisor. As a result, her personal poverty was a virtue that

continued to grow until it was one that she practiced to a heroic degree.

The Drexel’s summer home,

which the family had named “St. Michael’s,” was remodeled to become the first

novitiate for the new order. It was located in Torresdale, Pennsylvania, a

suburb of Philadelphia. The new home of the order housed ten novices and three

postulants. Immediately, they set about forming a school for the area

residents, both white and Colored. Having discussed the purpose of the order

and the people who would be the focus of its missionary efforts, we deem a

slight diversion necessary.

In recent years St.

Katharine has been portrayed as some sort of saint of “Social Justice” — as one

who campaigned for the “rights” of the Colored and Indian peoples. Nothing

could be further from the truth. Closely akin to her concern for her own

personal sanctity was her burning desire for the salvation of souls through

conversion to the Catholic Faith. When her efforts in this endeavor were

undermined or openly opposed, she worked to overcome these obstacles. She was

not intimidated by anyone who attempted to impede the salvation of souls. She

discovered the intense prejudice against Negroes and Indians — a particularly

evil manifestation of Protestantism in America. In several instances, similar

to today’s Traditional Catholics, she was forced to use more discreet means to

secure property for her schools for the Negro children in the South. In more

than one instance, she purchased a property through an intermediary. In

Nashville, for instance, when the former owner discovered who had purchased the

property and that it would be used as a school for Negro children, he organized

the neighbors in an attempt to thwart the project. He even attempted to

resurrect a long abandoned proposal to build a road through the property — all

for naught.

Such bigotry was not

limited to the South. In 1891, her ancestral home of St. Michael’s in

Torresdale, Pennsylvania was to be remodeled to serve as the new order’s

Motherhouse. Just before Archbishop Ryan was to conduct the formal ceremony to

lay the cornerstone of the new Motherhouse, they had a terrible fright. A stick

of dynamite was found in the very spot marked for the cornerstone. There were

rumors that all the Catholics on the platform attending the ceremony would be

blown to bits. When Archbishop Ryan was apprised of the situation, he requested

a dozen plainclothes policemen to be present during the ceremony. The architect

of the building project had a clever idea of his own. He bought a dozen

broomsticks and placed them into a wooden box, which he nailed shut and