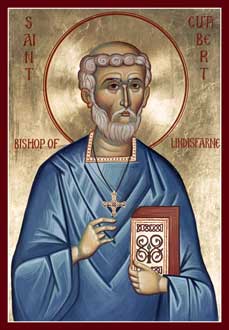

Saint Cuthbert , évêque

Né vers 634, il est élevé

en Écosse, il travaille d’abord comme berger. A 15 ans, il décide après une

expérience spirituelle, de devenir moine. Il est reçu à l’abbaye de Melrose,

dont le prieur, Saint-Boisil, lui enseigne les Écritures et les principes de la

vie religieuse. Quelques années plus tard, il accompagne l'abbé Eata au nouveau

monastère de Ripon, où il exerce la charge d'hôtelier. Il retourne ensuite à

Melrose, où il est élu abbé en remplacement de Boisil, décédé de la peste en

664. Un conflit s'étant produit à Lindisfarne, monastère frère de Melrose, il

se rend sur place, parvient à ramener la paix et y demeure plus de douze ans

comme abbé, où il introduit la liturgie romaine. Il se retire ensuite sur l’île

de Farne et s'installe dans une caverne. Huit ans plus tard, tous les notables

de la région lui rendent visite et le supplient d'accepter la dignité

épiscopale. Il refuse tout d'abord, mais finit par accepter, et c'est à York

qu'il est finalement consacré comme évêque de Lindisfarne, en 685. Moins de

deux ans plus tard, cependant, il tombe malade et abandonne son siège pour

passer les deux derniers mois de sa vie dans son île de Farne où il meurt le 20

mars 687.

Saint Cuthbert

Évêque de

Lindisfarne (+ 687)

Confesseur.

Cuthbert fut d'abord

évêque de Lindisfarne en Angleterre. Il établit le rite de la liturgie romaine

dans son diocèse. Il préféra reprendre la vie monastique au monastère de

Melrose, de tradition irlandaise, et s'en fut solitaire dans la paix de

Dieu.

Et c'est là que saint

Herbert, son meilleur ami, venait le rejoindre chaque année pendant

plusieurs jours pour parler des choses de Dieu. Ils connurent la grâce de

mourir à quelques jours l'un de l'autre et à la même heure.

Dans l’île de Farne en

Northumbrie d’Angleterre, l’an 687, le trépas de saint Cuthbert, évêque de

Lindisfarne. Il montra dans son ministère pastoral le même empressement

qu’auparavant au monastère et en ermitage. Il sut harmoniser pacifiquement les

austérités et la manière de vivre des Celtes avec les coutumes romaines, et

termina sa vie dans son ermitage insulaire.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/837/Saint-Cuthbert.html

Cuthbert

of Lindisfarne. Fresko aus dem 11. Jh. in der Galilee-Kapelle der Durham

Cathedral

Saint-Cuthbert,

thaumaturge de Grande-Bretagne, est né en Northumbrie autour de 634. Lors qu’il

était encore jeune, gardant les moutons de son maître, il eut une vision

d'anges emmenant l'âme de saint Aidan au Ciel dans une sphère de feu. Quelques

jours plus tard, il apprit que l'évêque Aidan de Lindisfarne avait reposé à

l'heure même où Cuthbert avait vu sa vision.

Adulte, saint Cuthbert

décida de quitter le monde et d'embrasser la vie monastique. Il entra au

monastère de Melrose, où il se consacra au service de Dieu. Son jeûne et ses

veilles étaient si extraordinaires que les autres moines l’admiraient. Il

passait souvent des nuits entières en prière, et ne mangeant rien pendant des

jours et des jours. Saint Cuthbert fut ensuite choisi pour être higoumène de

Melrose, guidant les frères par ses paroles et par son exemple. Il fit des

voyages dans toute la région environnante pour encourager les chrétiens et

prêcher l'Évangile à ceux qui n’en avaient jamais entendu parler. Il accomplit

également beaucoup de miracles, guérissant les malades et libérant ceux qui

étaient possédés par des démons.

En 664, Cuthbert étant

nommé prieur, il partit à Lindisfarne. Pendant son séjour à Lindisfarne, saint

Cuthbert continua comme à son habitude de visiter les gens du commun afin de les

inciter à chercher le Royaume des Cieux. Bien que certains des moines

préféraient leur style de vie négligent à la voie ascétique, par sa patience et

sa douce persuasion, saint Cuthbert les amena progressivement à l'obéissance et

à un meilleur état d'esprit. Le saint n'hésita pas à corriger ceux qui se

comportaient mal. Toutefois, sa gentillesse lui faisait rapidement pardonner à

ceux qui se repentaient. Quand les gens se confessaient à lui, il pleurait

souvent en sympathie avec leur faiblesse et souvent lui-même accomplissait

leurs épitimies.

Saint Cuthbert fut un

vrai père pour ses moines, mais son âme aspirait à une solitude complète, alors

il alla vivre sur une petite île ( à présent île Saint Cuthbert), à une courte

distance de Lindisfarne. Après avoir obtenu la victoire sur les démons par la

prière et le jeûne, le saint décida d'aller encore plus loin de ses semblables.

En 676, il se retira à Inner Farne, un lieu encore plus éloigné. Saint Cuthbert

y construisit une petite cellule qui ne pouvait être vue depuis le continent. A

quelques mètres, il construisit une maison d'hôtes pour les visiteurs de

Lindisfarne. Il resta là pendant près de neuf ans.

Un synode à Twyford, avec

le saint archevêque Théodore comme président, élit Cuthbert évêque de Hexham en

684. l’évêque Cuthbert resta humble comme il l’avait été avant sa consécration,

en évitant les parures et il porta des vêtements simples. Il remplit ses

fonctions avec dignité et grâce, tout en continuant à vivre comme un moine.

Cependant Il servit comme évêque pendant deux ans seulement. Sentant que le

moment de sa mort approchait, saint Cuthbert renonça à ses fonctions

archipastorales, se retirant en solitude pour se préparer.

Conseillant ses frères

immédiatement avant sa mort, saint Cuthbert parla de la paix et de l'harmonie,

leur enjoignant de se tenir en garde contre ceux qui encourageaient l’orgueil

et la discorde. Bien qu'il les ait encouragés à accueillir les visiteurs et à

leur offrir l'hospitalité, il leur recommanda également de ne pas avoir de

relations avec les hérétiques ou avec ceux qui menaient une mauvaise vie. Il

leur dit d'apprendre les enseignements des Pères et de les mettre en pratique,

et d’adhérer à la règle monastique qu’il leur avait apprise. Après avoir reçu

des Saints Mystères du Christ, saint Cuthbert remit son âme sainte à Dieu le 20

Mars 687.

Onze ans plus tard, le

tombeau de saint Cuthbert fut ouvert et ses reliques furent trouvées non

corrompues. Dans les siècles subséquents, les reliques furent déplacées à

plusieurs reprises en raison de la menace d'une invasion. Elles furent

finalement portées en lieu sûr, à Durham. Les reliques du saint furent ouvertes

à nouveau le 24 août 1104, et les reliques incorruptibles et fragrantes furent

placées dans la cathédrale, récemment achevée.

En 1537, trois

commissaires du roi Henry VIII vinrent piller la tombe et profaner les

reliques. Le corps de saint Cuthbert était encore intact, et il fut inhumé plus

tard. La tombe fut ouverte à nouveau en 1827. Dans le cercueil intérieur il y

avait un squelette enveloppé dans un linceul et cinq tuniques. Dans les

vêtements, une Croix d'or et de grenat fut trouvée, c’était probablement la

Croix pectorale de saint Cuthbert. On trouva également un peigne en ivoire, un

autel portatif de bois et d'argent, un épitrachelion, des morceaux d'un

cercueil en bois sculpté, et d'autres articles. Ceux-ci peuvent être vus à ce

jour dans le trésor de la cathédrale de Durham.

Saint Cuthbert est fêté

le 20Mars.

Version française Claude

Lopez-Ginisty

d'après

http://www.oodegr.com/english/biographies/

arxaioi/Cuthbert_Lindisfarne.htm

SOURCE : http://orthodoxologie.blogspot.ca/2010/04/saint-cuthbert-eveque-de-lindisfarne.html

Also

known as

Thaumaturgus of England

Wonder-Worker of England

4

September (translation of relics)

Profile

Orphaned at

an early age. Shepherd.

Received a vision of Saint Aidan

of Lindesfarne entering heaven; the sight led Cuthbert to become

a Benedictine monk at

age 17 at the monastery of Melrose,

which had been founded by Saint Aidan.

Guest-master at Melrose where he was know for his charity to poor travellers;

legend says that he once entertained an angel disguised

as a beggar.

Spiritual student of Saint Boswell. Prior of Melrose in 664.

Due to a dispute

over liturgical practice,

Cuthbert and other monks abandoned Melrose for Lindisfarne.

There he worked with Saint Eata. Prior and

then abbot of Lindesfarne until 676. Hermit on

the Farnes Islands. Bishop of Hexham, England. Bishop of Lindesfarne in 685.

Friend of Saint Ebbe

the Elder. Worked with plague victims

in 685.

Noted (miraculous) healer.

Had the gift of prophecy.

Evangelist in

his diocese,

often to the discomfort of local authorities both secular and ecclesiastical.

Presided over his abbey and

his diocese during

the time when Roman rites were

supplanting the Celtic,

and all the churches in the British Isles were brought under a single

authority.

Born

634 somewhere

in the British Isles

20

March 687 at Lindesfarne, England of

natural causes

interred with

the head of Saint Oswald,

which was buried with

him for safe keeping

body removed to Durham Cathedral at Lindesfarne in 1104

his body, and the head

of Saint Oswald,

were incorrupt

bishop accompanied

by swans and

otters

bishop holding

the crowned head

of Saint Oswald

hermit with

tau staff being fed by an eagle

incorrupt body being

found with a chalice on

his breast

man praying by

the sea

man rebuilding a hut and

driving out devils

man rebuking crows

man tended by eagles

man tended by swans

man tended by sea otters

man with a Benedictine monk kissing

his feet

man with pillars of light

above him

—

Hexham and Newcastle, England, diocese of

Lancaster, England, diocese of

Additional

Information

Apostle

of Northumbria, by Leonora Blanche Lang

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Book

of Saints and Friendly Beasts, by Abbie Farwell Brown

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by Edwin Burton

Golden

Legend, by Jacobus

de Voragine

Legends

of Saints and Birds, by Agnes Aubrey Hilton

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Our

Island Saints, by Amy Steedman

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Saints

of the Order of Saint Benedict, by Father Aegedius

Ranbeck, O.S.B.

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Christ

Church stained glass window

Christian

Biographies, by James Keifer

Life

and Miracles of Saint Cuthbert, by Saint Bede

images

ebooks

Life

of Saint Cuthbert, by Edward Consitt

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Readings

According to F. Cashier,

the swan is chiefly assigned to this saint, for this bird has been chosen as an

emblem of men who are particularly attached to a solitary life, since it is

generally very silent. However, we are inclined to think that the bird here

mentioned was the downy goose, and not the swan.

Let us judge from what M.

de Montalembert says, “They used to swarm on the rock (of Lindisfarne) in

former days, and are still found there, though in much smaller numbers, on

account of the people who come and steal their nests and shoot them. These

birds were found nowhere else in the British Isles, and were called the birds

of Saint Cuthbert. It is he who, according to a monk of the thirteenth century,

inspired their hereditary confidence because he took them for companions of his

solitude, and was careful that no one should disturb them in their

habits.” – from “The Little Bollandists” by Monsignor Paul Guérin, 1882

MLA

Citation

“Saint Cuthbert of

Lindisfarne“. CatholicSaints.Info. 4 November 2021. Web. 28 January 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-cuthbert-of-lindisfarne/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-cuthbert-of-lindisfarne/

St. Cuthbert

Bishop of Lindisfarne, patron of Durham,

born about 635; died 20 March, 687. His emblem is the head of St. Oswald,

king and martyr,

which he is represented as bearing in his hands. His feast is

kept in Great Britain and Ireland on

the 20th of March, and he is patron of the Diocese

of Hexham and Newcastle, where his commemoration is inserted among

the Suffrages of the Saints. His early biographers give no

particulars of his birth, and the accounts in the "Libellus de ortu",

which represent him as the son of an Irish king

named Muriahdach, though recently supported by Cardinal

Moran and Archbishop Healy, are rejected by

later English writers as legendary. Moreover, St.

Bede's phrase, Brittania . . . genuit (Vita Metricia,

c. i), points to his English birth. He was probably born in the

neighbourhood of Mailros (Melrose) of lowly parentage, for as a

boy he used to tend sheep on the mountain-sides near that monastery.

While still a child living with his foster-mother Kenswith his future lot

as bishop had

been foretold by a little play-fellow, whose prophecy had a lasting

effect on his character. He was influenced, too, by the holiness of

the community of Mailros, where St.

Eata was abbot and St.

Basil prior. In the year 651, while watching his sheep, he saw in

a vision the soul of St.

Aidan carried to heaven by angels,

and inspired by this became a monk at Mailros.

Yet it would seem that the troubled state of the country hindered him from

carrying out his resolution at once. Certain it is that at one part of his life

he was a soldier, and the years which succeed the death of St.

Aidan and Oswin of Deira seem to have been such as would

call for the military service of most of the able-bodied men of

Northumbria, which was constantly threatened at this time by the ambition of

its southern neighbor, King Penda of Mercia. Peace was not restored to the land

until some four years later, as the consequence of a great battle which was

fought between the Northumbrians and the Mercians at

Winwidfield. It was probably after this battle that Cuthbert found

himself free once more to turn to the life he desired. He arrived

at Mailros on horseback and armed with a spear. Here he soon became

eminent for holiness and

learning, while from the first his life was distinguished by supernatural occurrences

and miracles.

When the monastery at

Ripon was founded he went there as guest-master, but in 661 he, with

other monks who

adhered to the customs of Celtic

Christianity, returned to Mailros owing to

the adoption at Ripon of the Roman Usage in

celebrating Easter and

other matters. Shortly after his return he was struck by a pestilence which

then attacked the community, but he recovered, and became prior in

place of St.

Boisil, who died of the disease in 664. In this year the Synod

of Whitby decided in favour of the Roman Usage, and St.

Cuthbert, who accepted the decision, was sent by St.

Eata to be prior at Lindisfarne,

in order that he might introduce the Roman customs into that house.

This was a difficult matter which needed all his gentle tact and

patience to carry out successfully, but the fact that one so renowned for sanctity,

who had himself been brought up in the Celtic tradition, was loyally

conforming to the Roman use, did much to support

the cause of St.

Wilfrid. In this matter St. Cuthbert's influence on

his time was very marked. At Lindisfarne he

spent much time in evangelizing the people. He was noted

for his devotion to the Mass, which he could not celebrate

without tears, and for the success with which his zealous charity drew

sinners to God.

At length, in 676, moved

by a desire to attain greater perfection by means of

the contemplative life, he retired, with the abbot's leave,

to a spot which Archbishop Eyre identifies with St.

Cuthbert's Island near Lindisfarne,

but which Raine thinks was near Holburn, where "St. Cuthbert's

Cave" is still shown. Shortly afterwards he removed to Farne Island,

opposite Bamborough in Northumberland, where he gave himself up to a

life of great austerity. After some years he was called from this retirement by

a synod of bishops held

at Twyford in Northumberland, under St. Theodore, Archbishop of Canterbury.

At this meeting he was elected Bishop of Lindisfarne,

as St.

Eata was now translated to Hexham.

For a long time he withstood all pressure and only yielded after a long

struggle. He was consecrated at York by St.

Theodore in the presence of six bishops,

at Easter,

685. For two years he acted as bishop,

preaching and labouring without intermission, with wonderful results. At Christmas,

686, foreseeing the near approach of death, he resigned his see and

returned to his cell on Farne Island, where two months later he was seized with

a fatal illness. In his last days, in March, 687, he was tended by monks of Lindisfarne,

and received the last sacraments from Abbot Herefrid,

to whom he spoke his farewell words, exhorting the monks to

be faithful to Catholic unity and

the traditions of the Fathers. He died shortly after midnight,

and at exactly the same hour that night his friend St. Herbert, the hermit,

also died, as St. Cuthbert had predicted.

St. Cuthbert

was buried in his monastery at Lindisfarne,

and his tomb immediately

became celebrated for remarkable miracles.

These were so numerous and extraordinary that he was called the

"Wonder-worker of England".

In 698 the first transfer of the relics took

place, and the body was found incorrupt. During the Danish invasion

of 875, Bishop Eardulf and the monks fled

for safety, carrying the body of the saint with

them. For seven years they wandered, bearing it first into Cumberland, then

into Galloway and

back to Northumberland. In 883 it was placed in

a church at Chester-le-Street, near Durham,

given to the monks by

the converted Danish king,

who had a great devotion to the saint,

like King

Alfred, who also honoured St.

Cuthbert as his patron and was a benefactor to this church.

Towards the end of the tenth century, the shrine was removed to Ripon,

owing to fears of fresh invasion. After a few months it was being

carried back to be restored to Chester-le-Street, when, on arriving

at Durham a

new miracle, tradition says,

indicated that this was to be the resting-place of the saint's body.

Here it remained, first in a chapel formed

of boughs, then in a wooden and finally in a stone church, built on

the present site of Durham cathedral,

and finished in 998 or 999. While William the Conqueror was ravaging

the North in 1069, the body was once more removed, this time to Lindisfarne,

but it was soon restored. In 1104, the shrine was transferred to the

present cathedral,

when the body was again found incorrupt, with it being the head of St.

Oswald, which had been placed with St. Cuthbert's body for safety — a fact

which accounts for the well-known symbol of the saint.

From

this time to the Reformation the

shrine remained the great centre of devotion throughout the North

of England.

In 1542 it was plundered of all its treasures, but the monks had

already hidden the saint's body

in a secret place. There is a well-known tradition, alluded to in Scott's

"Marmion", to the effect that the secret of the hiding-place is known

to certain Benedictines who

hand it down from one generation to another. In 1827 the Anglican clergy of

the cathedral found

a tomb alleged

to be that of the saint,

but the discovery was challenged by Dr.

Lingard, who showed cause for doubting the identity of

the body found with that of St. Cuthbert. Archbishop Eyre,

writing in 1849, considered that the coffin found was undoubtedly that of

the saint,

but that the body had been removed and other remains substituted, while a later

writer, Monsignor Consitt, though not expressing a definite view,

seems inclined to allow that the remains found in 1827 were truly the bones

of St. Cuthbert. Many traces of the former widespread devotion to St.

Cuthbert still survive in the numerous churches, monuments,

and crosses raised in his honour,

and in such terms as "St. Cuthbert's patrimony", "St.

Cuthbert's Cross", "Cuthbert ducks" and "Cuthbert

down". The centre of modern devotion to him is found at St.

Cuthbert's College, Ushaw, near Durham,

where the episcopal ring of gold, enclosing a sapphire, taken

from his finger in 1537, is preserved, and where under

his patronage most of the priests for

the northern counties of England are

trained. His name is connected with two famous early copies of

the Gospel text. The first, known as the Lindisfarne or Cuthbert Gospels (now

in the British Museum, Cotton manuscripts Nero

D 4), was written in the eighth century by Eadfrid, Bishop of Lindisfarne.

It contains the four gospels and between the lines a number of

valuable Anglo-Saxon (Northumbrian) glosses; though written by

an Anglo-Saxon hand it is considered by the

best judges (Westwood) a noble work of old-Irish calligraphy and

illumination, Lindisfarne as

is well known being an Irish foundation.

The manuscript,

one of the most splendid in Europe,

was originally placed by its scribe as an offering on the

shrine of Cuthbert, and was soon richly decorated

by monastic artists (Ethelwold, Bilfrid) and provided by

another (Aldred) with the aforesaid

interlinear gloss (Karl Bouterwek, Die vier Evangelian in

altnordhumbrischer Sprache, 1857). It has also a history scarcely

less romantic than the body of Cuthbert. When in the ninth century

the monks fled

before the Danes with the latter treasure, they took with them

this manuscript,

but on one occasion lost it in the Irish Channel.

After three days it was found on the seashore at Whithern,

unhurt save for some stains of brine. Henceforth in the

inventories of Durham and Lindisfarne it

was known as "Liber S. Cuthberti qui demersus est

in mare" (the book of St. Cuthbert that fell into the sea). Its

text was edited by Stevenson and Warning (London, 1854-65)

and since then by Kemble and Hardwick, and

by Skeat (see LINDISFARNE). The second

early Gospel text connected with his name is the

seventh-century Gospel of St. John (now in possession of the Jesuit College at Stonyhurst, England)

found in 1105 in the grave of St. Cuthbert.

Burton,

Edwin. "St. Cuthbert." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 19 Mar.

2016<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04578a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Paul Knutsen.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John

M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04578a.htm

Saint

Cuthbert. Detail from Christopher Whall window in Gloucester Cathedral.

Saint Cuthbert

St. Cuthbert (634

-687) was thought by some to be Irish and by others, a Scot. Bede, the

noted historian, says he was a Briton. Orphaned when a young child, he was a

shepherd for a time, possibly fought against the Mercians, and became a monk at

Melrose Abbey.

In 661, he accompanied

St. Eata to Ripon Abbey, which the abbot of Melrose had built, but returned to

Melrose the following year when King Alcfrid turned the abbey over to St.

Wilfrid, and then became Prior of Melrose. Cuthbert engaged in missionary work

and when St. Colman refused to accept the decision of the Council of Whitby in

favor of the Roman liturgical practices and immigrated with most of the monks

of Lindisfarn to Ireland, St. Eata was appointed bishop in his place and named

Cuthbert Prior of Lindisfarn.

He resumed his missionary

activities and attracted huge crowds until he received his abbot’s permission

to live as a hermit, at first on a nearby island and then in 676, at one of the

Farnes Islands near Bamborough. Against his will, he was elected bishop of

Hexham in 685, arranged with St. Eata to swap Sees, and became bishop of

Lindisfarn but without the monastery. He spent the last two years of his

life administering his See, caring for the sick of the plague that dessimated

his diocese, working numerous miracles of healing, and gifted with the ability

to prophesy. He died at Lindisfarn. Feast day is March 20.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/cuthbert/

St

Cuthbert, Ackworth, West Yorkshire, England. The nave and chancel were restored

by John West Hugall in 1852-1854. The 15th century tower remains. Some carving

by Robert Mawer, and some by Catherine Mawer and William Ingle. This is St

Cuthbert above the porch door, carved by Catherine.

CUTHBERT OF LINDISFARNE.

634 A.D. – 687 A.D.

Cuthberts’ Call…

When Cuthbert was a child

he was not interested in anything spiritual, he loved sports and he loved to

play. He was always looking for a challenge or a challenger..One day while he

was playing a game in a field, at about eight years old, a little boy of around

three years old ran up to him. The child asked Cuthbert why he was playing and

wasting his time on sports when he should be praying and preparing to serve

God. When Cuthbert laughed, the little boy threw himself on the ground and

began to sob. The other boys tried to console the child but it was no use.

Cuthbert also tried to comfort him. The little boy got up and addressed

Cuthbert sternly, “Why are you so stubborn in playing these games when God is

calling you to serve him?” The child prophesied that one day Cuthbert would be

a Bishop. Cuthbert was amazed and he hugged the child who immediately stopped

crying. He knew that the words had reached Cuthberts’ heart.

Later on Cuthbert was a

shepherd, and one night when he saw a light streaming from Heaven he discovered

that Aiden the Beloved Bishop of Lindisfarne had died, he immediately went and

took the sheep to their owner and decided to become a monk at the monastery at

Melrose.

Cuthberts’ life was

filled with incredible spiritual miracles including incidents with animals and

birds which was fairly common with the Celtic church (came from the stream of

the church which flowed from the Desert fathers in Egypt).

Cuthbert and the Otters

One of the young men

wanted to find out where Cuthbert went in the night-time when he left the

monastery and so he followed him secretly. Cuthbert went into the river up to

his neck and stayed for several hours worshipping and praying. When he came out

of the water two otters came to him and stretched themselves out beside him,

warming him with the heat of their own bodies. The young man who had followed

him was so frightened he had difficulty making it back to the monastery. When

he saw Cuthbert he fell at his feet asking forgiveness for his spying.

Cuthbert and the birds…

Cuthbert decided, having

left the monastery that he wanted to emulate the lives of the Desert Fathers,

and live by the labor of his own hands. He asked the monks to bring him barley

seeds to sow. Having planted the barley, it soon sprang up, but just as it was

ripening, some birds flew down and began to eat it.. Cuthbert came out and

began to scold the birds, “Why are you eating that which you didn’t sow? Is it

that your need is greater than mine? If so, you can have permission to help

yourselves; if not go away, and stop taking that which does not belong to you.”

The birds left and the barley was harvested. A while later the birds returned

and began taking straw from the roof for their nests. Cuthbert again came out

and shouted at them, “In the name of Jesus Christ, depart at once; do not dare

to cause further damage.” When he finished speaking the birds flew away. Three

days later they returned when Cuthbert was digging, and they came and stood in

front of him with their heads bowed down. Cuthbert was happy to forgive them

and invited them to return. Next time the birds came back bringing a lump of

pigs lard which Cuthbert kept in the guest house for his visitors to grease

their shoes. He said, “If the birds can show humility, how much more should we

humans seek such virtues.” The birds remained on the island with Cuthbert for

many years, building nests with materials they found THEMSELVES.

Just prior to his death

Cuthbert felt a fire in his stomach and the same day a minister/ priest arrived

by boat. Cuthbert knew that he was going to leaving this world and sat down and

dictated his final instructions for the brethren. “Live at peace with one

another, when you meet try and agree and be of one mind. Live at peace with

those around you and never treat anyone else with contempt. Always welcome

others to your monastery. Never imagine that you or your way of life is

superior to others, all who share the Christian faith are equal in Gods

sight..” When he had finished speaking he was very quiet. He stayed quiet until

the evening when he took communion. As he took the bread he lifted his arms

upward as if embracing someone, then his face filled with joy, he gave up his

spirit to God.

O’Hanlans Lives of

the Irish Saints

FROM CELTIC FLAMES-KATHIE

WALTERS

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, OSB B (RM)

Born in Northumbria, England (?) or Ireland, c. 634; died on Inner Farne in

March 20, 687; feast of his translation to Durham, September 4. Saint Cuthbert

is possibly the most venerated saint in England, especially in the northern

part of the country, where he was a very active missionary. Yet his real

nationality is debated. His biographer, Saint Bede, did not specify it. Of

course, the English claim him, but so do the Scottish.

There is a good

likelihood the he was an Irishman named Mulloche, great-grandson of the High

King Muircertagh of Ireland because, according to Moran citing documents in

Durham Cathedral, the rood screen bore the inscription: "Saint Cuthbert,

Patron of Church, City and Liberty of Durham, an Irishman by birth of royal

parentage who was led by God's Providence to England." The cathedral's

stained glass windows, which had been registered but destroyed during the reign

of Henry VI, depicted the saint's life begin with his birth "at

Kells" in Meath. This fact is corroborated by an ancient manuscript viewed

by Alban Butler at Cottonian Library. One tradition relates that his mother,

the Irish princess Saba, set out on a pilgrimage to Rome, left Cuthbert in the

care of Kenswith, and died in Rome.

Thus, Cuthbert, like

David, was a shepherd boy on the hills above Leader Water or the valley of the

Tweed. Of unknown parentage, he was reared in the Scottish lowlands by a poor

widow named Kenswith, and was a cripple because of an abscess on the knee made

worse by an attempted cure. But despite this disability he was boisterous and

high-spirited, and so physically strong that after he became a monk, on a visit

to the monastery at Coldingham, he spent a whole night upon the shore in

prayer, and strode into the cold sea praising God.

According to one of Saint

Bede's two vitae of the saint, when Cuthbert was about 15, he had a vision of

angels conducting the soul of Saint Aidan to heaven. Later, while still a

youth, he became a monk under Saint Eata at Melrose Abbey on the Tweed River.

The prior of Melrose, Saint Boisil, taught Cuthbert Scripture and the pattern

of a devout life. Cuthbert went with Eata to the newly-founded abbey of Ripon

in 661 as guest steward. He returned to Melrose, still just a mission station

of log shanties, when King Alcfrid turned Ripon over to Saint Wilfrid. It was

from Melrose that Cuthbert began his missionary efforts throughout Northumbria.

Cuthbert attended Boisil

when the latter contracted the plague. The book of the Scriptures from which he

read the Gospel of John to the dying prior was laid on the altar at Durham in

the 13th century on Saint Cuthbert's feast. Thus, in 664, Cuthbert became prior

of Melrose at the death of Boisil. Soon thereafter Cuthbert fell deathly ill

with the same epidemic. Upon hearing that the brethren had prayed throughout

the night for his recovery, he called for his staff, dressed, and undertook his

duties (but he never fully recovered his health thereafter).

In 664, when Saint Colman

refused to accept the decision of the Synod of Whitby in favor of Roman

liturgical custom and migrated to Ireland with his monks, Saint Tuda was

consecrated bishop in his place, while Eata was named abbot and Cuthbert prior

of Lindisfarne, a small island joined to the coast at low tide. From

Lindisfarne Cuthbert extended his work southward to the people of

Northumberland and Durham.

Afterwards Cuthbert was

made abbot of Lindisfarne, where he grew to love the wild rocks and sea, and

where the birds and beasts came at his call. Then for eight years beginning in

676, Cuthbert followed his solitary nature by removing himself to the solitude

of the isolated, infertile island of Farne, where it was believed that he was

fed by the angels. There built an oratory and a cell with only a single small

window for communication with the outside world. But he was still sought after,

and twice the king of Northumberland implored him to accept election as bishop

of Hexham, to which he finally agreed in 684, though unwillingly and with

tears.

Almost immediately

Cuthbert exchanged his see with Eata for that of Lindisfarne, which Cuthbert

preferred. Thus, on Easter Sunday 685, Cuthbert was consecrated bishop of

Lindisfarne by Saint Theodore archbishop of Canterbury, with six bishops in

attendance at York. For two years Cuthbert was bishop of Lindisfarne, still

maintaining his frugal ways and "first doing himself what he taught

others." He administered his see, cared for the sick of the plague that

decimated his see, distributed alms liberally, and worked so many miracles of

healing that he was known in his lifetime as the "Wonder-Worker of Britain."

Then at Christmas in 686, in failing health and knowing that his end was near,

he resigned his office and retired again to his island cell; but though

seriously ill and suffering intensely, he refused all aid, allowing none to

nurse him, and finished his course alone.

In the very act of

lifting his hands in prayer "his soul sped its way to the joys of the

heavenly kingdom." News of his death was flashed by lantern to the

watchers at Lindisfarne. Bede reports: "As the tiny gleam flashed over the

dark reach of sea, and the watchman hurried with his news into the church, the

brethren of the Holy Island were singing the words of the Psalmist: "Thou

hast cast us out and scattered us abroad . . . Thou hast shown thy people heavy

things."

He was buried at

Lindisfarne, where they remained incorrupt for several centuries, but after the

Viking raids began his remains wandered with the displaced monks for about 100

years until they were translated to Durham cathedral in 1104. Until its

desecration under Henry VIII, his shrine at Durham was one of the most

frequented places of pilgrimage for the power of healing that Cuthbert

possessed during his lifetime lived on after him. The bones discovered in 1827

beneath the site of the medieval shrine are probably his. He is said to have

had supernatural gifts of healing and insight, and people thronged to consult

him, so that he became known as the wonder-worker of Britain. He had great

qualities as a preacher, and made many missionary journeys. Bede wrote that

"Cuthbert was so great a speaker and had such a light in his angelic face.

He also had such a love for proclaiming his good news, that none hid their

innermost secrets from him." Year after year, on horseback and on foot, he

ventured into the remotest territories between Berwick and Galloway. He built

the first oratory at Dull, Scotland, with a large stone cross before it and a

little cell for himself. Here a monastery arose that became Saint Andrew's

University.

His task was not easy,

for he lived in an area of vast solitude, of wild moors and sedgy marshes

crossed only by boggy tracts, with widely scattered groups of huts and hovels

inhabited by a wild and heathen peasantry full of fears and superstitions and haunted

by terror of pagan gods. His days were filled with incessant activity in an

attempt to keep the spirit of Christianity alive and each night he kept vigil

with God.

But unlike the Celtic

missionaries, he spoke their language and knew their ways, for he had lived

like them in a peasant's home. Once, when a snowstorm drove his boat onto the

coast of Fife, he cried to his companions in the storm: "The snow closes

the road along the shore; the storm bars our way over the sea. But there is

still the way of Heaven that lies open."

Cuthbert was the Apostle

of the Lowlands, renowned for his vigor and good-humor; he outstripped his

fellow monks in visiting the loneliest and most dangerous outposts from cottage

to cottage from Berwick to Solway Firth to bring the Good News of Christ.

Selflessly he entered the houses of those stricken by the plague. And he was

the most lovable of saints. His patience and humility persuaded the reluctant

monks of Lindisfarne to adopt the Benedictine Rule.

He is especially appealing

to us today because he was a keenly observant man, interested in the ways of

birds and beasts. In fact, the Farne Islands, which served as a hermitage to

the monks of Durham, are now a bird and wildlife sanctuary appropriately under

the protection of Cuthbert. In his own time he was famed as a worker of

miracles in God's name. On one occasion he healed a woman's dying baby with a

kiss. The tiny seashells found only on his Farne Island are traditionally

called Saint Cuthbert's Beads, and are said by sailors to have been made by

him. This tradition is incorporated in Sir Walter Scott's Marmion.

The ample sources for his

life and character show a man of extraordinary charm and practical ability, who

attracted people deeply by the beauty of holiness.

His cultus is recalled in

places names, such as Kirkcudbright (Galloway), Cotherstone (Yorkshire), Cubert

(Cornwall), and more than 135 church dedications in England as well as an

additional 17 in Scotland. A chapel in the crypt of Fulda was dedicated to him

at its consecration (Attwater, Attwater2, Benedictines, Bentley, Colgrave,

D'Arcy, Delaney, Encyclopedia, Fitzpatrick, Gill, Montague, Montalembert2,

Moran, Skene, Tabor, Webb).

The following legends

about Saint Cuthbert reveal as much about their author, the Venerable Bede as

they do about Saint Cuthbert. Though they repeat in detail some of what is

outlined above, they show the historian's care to note source and authority and

show his quick eye that observes nature in detail. The complete biography can

be found at the Medieval Sourcebook.

"One day as he rode

his solitary way about the third hour after sunrise, he came by chance upon a

hamlet a spear's cast from the track, and turned off the road to it. The woman

of the house that he went into was the pious mother of a family, and he was

anxious to rest there a little while, and to ask some provision for the horse

that carried him rather than for himself, for it was the oncoming of winter.

"The woman brought him kindly in, and was earnest with him that he would

let her get ready a meal, for his own comfort, but the man of God denied her.

'I must not eat yet,' said he, 'because today is a fast.' It was indeed Friday

when the faithful for the most part prolong their fast until the third hour

before sunset, for reverence of the Lord's Passion.

"The woman, full of hospitable zeal, insisted. 'See now,' said she, 'the

road that you are going, you will find never a clachan or a single house upon

it, and indeed you have a long way yet before you, and you will not be at the

end of it before sundown. So do, I ask you, take some food before you go, or

you will have to keep your fast the whole day, and maybe even till the morrow.'

But though she pressed him hard, devotion to his religion overcame her

entreating, and he went through the day fasting, until evening.

"But as twilight fell and he began to see that he could not come to the

end of the journey he had planned that day, and that there was no human

habitation near where he could stay the night, suddenly as he rode he saw close

by a huddle of shepherds' huts, built ramshackle for the summer, and now lying

open and deserted.

"Thither he went in search of shelter, tethered his horse to the inside

wall, gathered up a bundle of hay that the wind had torn from the thatch, and

set it before him for fodder. Himself had begun to say his hours, when suddenly

in the midst of his chanting of the Psalms he saw his horse rear up his head

and begin cropping the thatch of the hovel and dragging it down, and in the

middle of the falling thatch came tumbling a linen cloth lapped up; curious to

know what it might be, he finished his prayer, came up and found wrapped in the

linen cloth a piece of loaf still hot, and meat, enough for one man's meal.

"And chanting his thanks for heaven's grace, 'I thank God,' said he, 'Who

has stooped to make a feast for me that was fasting for love of His Passion,

and for my comrade.' So he divided the piece of loaf that he had found and gave

half to the horse, and the rest he kept for himself to eat, and from that day

he was the readier to fasting because he understood that the meal had been

prepared for him in the solitude by His gift Who of old fed Elijah the solitary

in like fashion by the birds, when there was no man near to minister to him; Whose

eyes are on them that fear Him and that hope in His mercy, that He will snatch

their souls from death and cherish them in their hunger.

"And this story I had from a brother of our monastery which is at the

mouth of the river Wear, a priest, Ingwald by name, who has the grace of his

great age rather to contemplate things eternal with a pure heart than things

temporal with the eyes of earth; and he said that he had it from Cuthbert

himself, the time that he was bishop."

And a second story

recorded by Bede:

"It was his way for

the most part to wander in those places and to preach in those remote hamlets,

perched on steep rugged mountain sides, where other men would have a dread of

going, and whose poverty and rude ignorance gave no welcome to any scholar. . .

. Often for a whole week, sometimes for two or three, and even for a full

month, he would not return home, but would abide in the mountains, and call

these simple folk to heavenly things by his word and his ways. . . ."

[He was, moreover, easily entreated, and came to stay at the abbey of

Coldingham on a cliff above the sea.]

"As was his habit, at night while other men took their rest, he would go

out to pray; and after long vigils kept far into the night, he would come home

when the hour of common prayer drew near. One night, a brother of this same

monastery saw him go silently out, and stealthily followed on his track, to see

where he was going or what he would do.

"And so he went out from the monastery and, his spy following him went

down to the sea, above which the monastery was built; and wading into the

depths till the waves swelled up to his neck and arms, kept his vigil through

the dark with chanting voiced like the sea. As the twilight of dawn drew near,

he waded back up the beach, and kneeling there, again began to pray; and as he

prayed, straight from the depths of the sea came two four-footed beasts which

are called by the common people otters.

"These, prostrate before him on the sand, began to busy themselves warming

his feet with pantings, and trying to dry them with their fur; and when this

good office was rendered, and they had his benediction, they slipped back again

beneath their native waters. He himself returned home, and sang the hymns of

the office with the brethren at the appointed hour. But the brother who had

stood watching him from the cliffs was seized with such panic that he could

hardly make his way home, tottering on his feet; and early in the morning came

to him and fell at his feet, begging forgiveness with his tears for his foolish

attempt, never doubting but that his behavior of the nights was known and

discovered.

"To whom Cuthbert: 'What ails you, my brother? What have you done? Have

you been out and about to try to come at the truth of this night wandering of

mine? I forgive you, on this one condition: That you promise to tell no man

what you saw, until my death.' . . . And the promise given, he blessed the

brother and absolved him alike of the fault and the annoyance his foolish

boldness had given: The brother kept silence on the piece of valor that he had

seen, until after the Saint's death, when he took pains to tell it to

many"

Bede relates another

story:

After many years at

Lindisfarne Abbey, Cuthbert set out to become a hermit on an island called

Farne, which unlike Lindisfarne, "which twice a day by the upswelling of

the ocean tide . . . becomes an island, and twice a day, its shore again bared

by the tide outgoing, is restored to its neighbor the land. . . . No man,

before God's servant Cuthbert, had been able to make his dwelling here alone,

for the phantoms of demons that haunted it; but at the coming of Christ's

soldier, armed with the helmet of salvation, the shield of faith and the sword

of the Spirit which is the word of God, the fiery darts of the wicked fell

quenched, and the foul Enemy himself, with all his satellite mob, was put to

flight."

Cuthbert built himself a cell on the island by cutting away the living rock of

a cave. He constructed a wall out of rough boulders and turf. Some of the

boulders were so large that "one would hardly think four men could lift

them, and yet he is known to have carried them thither with angelic help and

set them into the wall. He had two houses in his enclosure, one an oratory, the

other a dwelling place. . . . At the harbor of the island was a larger house in

which the brethren when they came to visit him could be received and take their

rest. . . ."

At first he accepted bread from Lindisfarne, "but after a while he felt it

was more fit that he should live by the work of his own hand, after the example

of the Fathers. So he asked them to bring him tools to dig the ground with, and

wheat to sow; but the grain that he had sown in spring showed no sign of a crop

even by the middle of the summer. So when the brethren as usual were visiting

him the man of God said, 'It may be the nature of the soil, or it may be it is

not the will of God that any wheat should grow for me in this place: So bring

me, I pray you, barley, and perhaps I may raise some harvest from it. But if God

will give it no increase, it would be better for me to go back to the community

than be supported here on other men's labors.'

"They brought him the barley, and he committed it to the ground, far past

the time of sowing, and past all hope of springing: and soon there appeared an

abundant crop. When it began to ripen, then came the birds, and its was who

among them should devour the most. So up comes God's good servant, as he would

afterwards tell--for many a time, with his benign and joyous regard, he would

tell in company some of the things that he himself had won by faith, and so

strengthen the faith of his hearers--'And why,' says he, 'are you touching a

crop you did not sow? Or is it, maybe, that you have more need of it than I? If

you have God's leave, do what He allows you: but if not, be off, and do no more

damage to what is not your own.' He spoke, and at the first word of command,

the birds were off in a body and come what might for ever after they contained

themselves from any trespass on his harvests. . . .

"And here might be told a miracle done by the blessed Cuthbert in the

fashion of the aforesaid Father, Benedict, wherein the obedience and humility

of the birds put to shame the obstinacy and arrogance of men. Upon that island

for a great while back a pair of ravens had made their dwelling: And one day at

their nesting time the man of God spied them tearing with their beaks at the

thatch on the brethren's hospice of which I have spoken, and carrying off

pieces of it in their bills to build their nest.

"He thrust at them gently with his hand, and bade them give over this

damage to the brethren. And when they scoffed at his command, 'In the name of

Jesus Christ,' said he, 'be off with you as quick as ye may, and never more

presume to abide in the place which ye have spoiled.' And scarcely had he

spoken, when they flew dismally away.

"But toward the end of the third day, one of the two came back, and

finding Christ's servant busy digging, comes with his wings lamentably trailing

and his head bowed to his feet, and his voice low and humble, and begs pardon

with such signs as he might: which the good father well understanding, gives

him permission to return.

"As for the other, leave once obtained, he straight off goes to fetch his

mae, and with no tarrying, back they both come, and carrying along with them a

suitable present, no less than a good- sized hunk of hog's lard such as one

greases axles with: Many a time thereafter the man of God would show it the

brethren who came to see him, and would offer it to grease their shoes, and he

would urge on them how obedient and humble men should be, when the proudest of

birds made haste with prayers and lamentation and presents to atone for the

insult he had given to man. And so, for an example of reformed life to men,

these did abide for many years thereafter on that same island, and built their

nest, nor ever wrought annoyance upon any" (Bede).

In art, Saint Cuthbert is

dressed in episcopal vestments bearing the crowned head of Saint Oswald (Seal

of Lindisfarne). At times he may be shown (1) with pillars of light above him;

(2) with swans tending him; (3) as a hermit with a tau staff being fed by an

eagle; (4) rebuking crows; (5) rebuilding a hut and driving out devils; (6)

praying by the sea; (7) with a Benedictine monk kissing his feet; (8) when his

incorrupt body was found with a chalice on his breast (Roeder); or (9) tended

by sea otters, which signifies either his living in the midst of waters, or

alludes to a legend. It is said that one night as he lay on the cold shore,

exhausted from his penances, two otters revived his numb limbs by licking them

(Tabor). There is a stained-glass icon of Cuthbert in York Minster from the

late Middle Ages, as well as paintings on the backs of the stalls at Carlisle

cathedral (Farmer).

The shrine of Saint

Cuthbert is at Durham, but he is also venerated at Ripon and Melrose. His feast

is still kept at Meath, Saint Andrews, and the northern dioceses of England

(Attwater2). He is the patron of shepherds and seafarers, and invoked against

the plague (Roeder). His patronage of sailors was the result of his appearance

in the midst of violent storms at sea, wearing his mitre, as late as the 12th

century. He is said to have used his crozier sometimes as an oar and at other

times as a helm to save the struggling sailors from shipwreck. He is also said

to have appeared to King Alfred, the conquering Canute the Dane, William the

Conqueror, and others at critical moments. Thus, until the time of Henry VIII,

soldiers marched under a sacred standard containing the corporal Cuthbert had

used at Mass (D'Arcy).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0320.shtml

Frontispiece of Bede's Life of St Cuthbert, showing King Æthelstan (924–939) presenting a copy of the book to the saint himself. 29.2 x 20. Originally from MS 183, f.1v at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. circa 930. The National Portrait Gallery History of the Kings and Queens of England by David Williamson, 1998

Golden Legend – Saint

Cuthbert

Article

Here next followeth the

Life of Saint Cuthbert of Durham.

Saint Cuthbert was born

in England, and when he was eight years old our Lord showed for him a fair

miracle for to draw him to his love. For on a time, as he played at the ball

with other children, suddenly there stood among them a fair young child of the

age of three years, which was the fairest creature that ever they beheld, and

anon he said to Cuthbert: Good brother, use no such vain plays, ne set not thy

heart on them. But for all that Cuthbert took none heed to his words, and then

this child fell down and made great heaviness, wept sore and wrung his hands,

and then Cuthbert and the other children left their play and comforted him, and

demanded of him why he made such sorrow. Then the child said to Cuthbert: All

mine heaviness is only for thee, because thou usest such vain plays, for our

Lord hath chosen thee to be an head of holy church; and then suddenly he

vanished away. And then he knew verily that it was an angel sent from our Lord

to him, and from then forthon he left all such vain plays and never used them

more, and began to live holily. And then he desired of his father that he might

be set to school, and anon he drew him to perfect living, for he was ever in

his prayers, night and day, and most desired of our Lord to do that which might

please him and eschew that should displease him. And he lived so virtuously and

holily, that all the people had joy of him, and within a while after, Aidanus

the bishop died. And as Cuthbert kept sheep in the field, looked upward and saw

angels bear the soul Aidanus the bishop to heaven with great melody. And after

that Saint Cuthhert would no more keep sheep but went anon to the abbey of

Jervaulx, and there he was a monk, of whom all the convert were right glad, and

thanked our Lord that had sent him thither. For he lived there full holily, in

fasting and great penance doing. And at last he had the gout in his knees,

which he had taken of cold in kneeling upon the cold stones when he said his

prayers, in such wise that his knees began to swell and the sinews of his leg

were shrunk that he might neither go nor stretch out his leg, but ever he took

it full patiently and said: When it pleaseth our Lord it shall pass away.

And within a while after,

his brethren for to do him comfort bare him into the field, and there they met

with a knight which said: Let me see and handle this Cuthbert’s leg; and then

when he had felt it with his hands, he bade them take the milk of a cow of one

colour, and the juice of small plantain, and fair wheat flour, and seethe them

all together, and make thereof a plaister and lay it thereto and it will make

him whole. And as soon as they had so done he was perfectly whole, and then he

thanked our Lord full meekly. And after, he knew by revelation that it was an

angel sent by our Lord to heal him of his great sickness and disease.

And the abbot of that

place sent him to a cell of theirs to be hosteler, for to receive their guests

and do them comfort, and soon after our Lord showed there a fair miracle for

his servant Saint Cuthbert, for angels came to him oft-times in likeness of

other guests, whom he received and served diligently with meat and drink and

other necessaries. On a time there came guests to him whom he received, and

went into the houses of office for to serve them, and when he came again they

were gone, and went after for to call and could not espy them, ne know the

steps of their feet, how well that it was then a snow; and when he returned he

found the table laid and thereon three fair white loaves of bread all hot which

were of marvellous beauty and sweetness, for all the place smelled of the sweet

odour of them. Then he knew well that the angels of our Lord had been there,

and rendered thankings to our Lord that he had sent to him his angels for to

comfort him.

And every night when his

brethren were abed he would go and stand in the cold water all naked up to the

chin till it were midnight, and then he would issue out, and when he came to

land he might not stand for feebleness and faintness, but oft fell down to the

ground. And on a time as he lay thus, there came two otters which licked every

place of his body, and then went again to the water that they came from. And

then Saint Cuthbert arose all whole and went to his cell again, and went to

matins with his brethren. But his brethren knew nothing of his standing thus

every night in the sea to the chin, but at the last one of his brethren espied

it and knew his doing, and told him thereof, but Saint Cuthbert charged him to

keep it secret and tell no man thereof during his life. And after this within a

while the bishop of Durham died, and Saint Cuthbert was elected and sacred

bishop in his stead after him, and ever after he lived full holily unto his

death, and, by his preaching and ensample giving, he brought much people to

good living. And tofore his death he left his bishopric and went into the holy

island, where he lived an holy and solitary life, unto that he being full of

virtues, rendered his soul unto Almighty God and was buried at Durham, and

after translated, and the body laid in a fair and honourable shrine, where as

yet daily our Lord showeth for his servant there many fair and great miracles.

Wherefore let us pray unto this holy saint that he pray for us.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/golden-legend-saint-cuthbert/

Statue

of St Cuthbert, at Lindisfarne Priory, Northumberland. The east end of the

priory church is visible beyond the statue.

Saints

of the Order of Saint Benedict – Saint Cuthbert, Bishop

At an early age Saint Cuthbert’s thoughts were turned

to religion by a vision, in which, while engaged in prayer in the night-time,

he saw Saint Aidan’s soul surrounded by a brilliant light, entering Heaven at

the very moment that Saint died. This vision made Saint

Cuthbert betake himself to the Monastery of Melrose, which at that time was

governed by Saint Eatta. The young novice was so pious, so strict an observer

of the Rule, and so courteous and pleasing in manner, that, six years after his

profession, he was entrusted with the duties of guest-master. On one occasion,

when proceeding early in the morning to the guest-house to attend to the duties

of his office, he found in front of the door a young man, who seemed exhausted

from exposure to the weather and from want of food. The guest-master, pitying

the stranger’s condition, took him indoors, washed and warmed his feet, and

bade him wait till he prepared and brought him some food. When the Saint

returned, he was amazed to find the stranger gone. On the table lay two loaves

of surpassing whiteness, which gave forth a delicious perfume, and showed that

the Saint had entertained an angel unawares. This was not the only occasion on

which Saint Cuthbert enjoyed the converse of angels; often was he honoured by

receiving his food from their hands.

It was Saint Cuthbert’s

custom, when on a journey, to pass the night in prayer, and unknown to his

travelling-companions, to slip out to a church, or to wherever the fervour of

his devotion carried him. Once his companions missed him, and curious to know

what Cuthbert was doing out of doors at that hour of the night, they followed

him, and found him praying, immersed to his neck in the sea. By his holy life,

and by preaching the Gospel to the rude inhabitants of the mountainous

districts, Saint Cuthbert won them over from their superstitious and idolatrous

practices, and gained such an influence over them that they confided to him the

secrets of their inmost hearts. They were afraid to conceal from him whatever

sins they had committed.

On the death of Boisil

the Prior, Cuthbert was chosen in his place. The new Prior inspired his

disciples with a zealous desire to emulate his virtues. Many miracles too were

wrought by him, such as the driving out of devils, and the extinguishing of

sudden outbursts of fire. It is said that, when he was worn out by want of food

on one of his journeys, some fish was brought to him by an eagle.

By the command of Eatta,

Cuthbert was summoned to Lindisfarne to reform the monks of that abbey, who had

become somewhat lax. This he soon effected by his patience, by his persuasiveness,

and above all, by his example. When he had succeeded in this task, he, at his

urgent request, was allowed by Eatta to retire to the Island of Farn, to lead

the solitary life. There for years he subjected himself to the most severe

penances, and every day brought himself nearer and nearer to God. By sending

her his girdle to wear, he was enabled to cure the Abbess Elfleda, a lady of

royal birth, when all hope of saving her life was abandoned by the physicians.

He also foretold the death of King Egfrith in the battle against the Picts, the

plague that soon after devastated England, and his own departure from his

hermitage to the Cathedral of Lindisfarne.

Many letters and

messengers had been sent by the Synod of Bishops and by King Egfrith to summon

Cuthbert to undertake the charge of this See, but the Saint’s humility shrank

from the honour; at last Egfrith himself sailed to Farn and compelled Cuthbert

to accompany him to the Synod at York, where he was consecrated.

In this high office Saint

Cuthbert preached and laboured for two years, never relaxing the strict

discipline of his former life. Finding his strength failing, he retired to his

old retreat of Farn to prepare for death. There two months later he breathed

his last, on the 20th March, A.D. 687.

When Saint Cuthbert’s

body was dug up, four hundred and eleven years after his death, it was found

quite free from any signs of corruption. It was again found whole and incorrupt

in 1537 by the men who were sent by Henry VIII to destroy the shrine and to

scatter the relics of the Saint.

– text and illustration

taken from Saints

of the Order of Saint Benedict by Father Aegedius

Ranbeck, O.S.B.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saints-of-the-order-of-saint-benedict-saint-cuthbert-bishop/

Ernest

Ange Duez, Saint Cuthbert, 1879,

huile

sur toile, partie centrale du triptyque. 334 x 134, Paris, Musée d’Orsay

March 20

St. Cuthbert, Bishop of

Lindisfarne, Confessor

From his life written by

Bede, and from that author’s Church History, b. 4. c. 27 to c. 32. Simeon

Dunelm, or rather Turgot, Hist. Dunelm. published by Bedford: the old Latin

hymn on St. Cuthbert. MS. in Bibl. Cotton. n. 41. apud Wanley, p. 184. and four

Latin prayers, in honour of St. Cuthbert, MS. n. 190. in the library of Durham

Church. Warnly, Catal. t. 2. p. 297. Harpsfield, sæc. 7. c. 34. Hearne on

Langtoft, t. 2. p. 687. N. B. The history of Durham, which is here quoted, was

compiled by Turgot, prior of Durham, down to the year 1104, and continued to

the year 1161 by Simeon.

A.D. 687

WHEN the Northumbrians, under the pious King Oswald, had, with great fervour,

embraced the Christian faith, the holy bishop St. Aidan founded two

monasteries, that of Mailros, on the bank of the Tweed and another in the isle

of Lindisfarne, afterwards called Holy Island, four miles distant from Berwick.

In both he established the rule of St. Columba; and usually resided himself in

the latter. St. Cuthbert 1 was

born not very far from Mailros, and in his youth was much edified by the devout

deportment of the holy inhabitants of that house, whose fervour in the service

of God, and the discharge of the duties of a monastic life, he piously

endeavoured to imitate on the mountains where he kept his father’s sheep. It

happened one night that, whilst he was watching in prayer, near his flock,

according to his custom, he saw the soul of St. Aidan carried up to heaven by

angels, at the very instant that holy man departed this life in the isle of

Lindisfarne. Serious reflections on the happiness of such a death determined

the pious young man to repair, without delay, to Mailros, where he put on the

monastic habit, whilst Eata was abbot, and St. Boisil prior. He studied the

holy scriptures under the latter, and in fervour surpassed all his brethren in

every monastic exercise. Eata being called to govern the new monastery of

Rippon, founded by King Alcfrid, he took with him St. Cuthbert, and committed

to him the care of entertaining strangers; which charge is usually the most

dangerous in a religious state. Cuthbert washed the feet of others, and served

them with wonderful humility and meekness, always remembering that Christ

himself is served in his members. And he was most careful that the functions of

Martha should never impair his spirit of recollection. When St. Wilfrid was

made abbot of Rippon, St. Cuthbert returned with Eata to Mailross; and St.

Boisil dying of the great pestilence, in 664, he was chosen provost or prior in

his place.

In this station, not content by word and example to form his monks

to perfect piety, he laboured assiduously among the people to bring them off

from several heathenish customs and superstitious practices which still

remained among them. For this purpose, says our venerable historian, he often

went out sometimes on horseback, but oftener on foot, to preach the way of life

to such as were gone astray. Parochial churches being at this time very scarce

in the country, it was the custom for the country people to flock about a

priest or ecclesiastical person, when he came into any village, for the sake of

his instructions; hearkening willingly to his words, and more willingly

practising the good lessons he taught them. St. Cuthbert excelled all others by

a most persuasive and moving eloquence; and such a brightness appeared in his

angelical face in delivering the word of God to the people, that none of them

durst conceal from him any part of their misbehaviour, but all laid their

conscience open before him, and endeavoured by his injunctions and counsels to

expiate the sins they had confessed, by worthy fruits of penance. He chiefly

visited those villages and hamlets at a distance, which, being situate among

high and craggy mountains, and inhabited by the most rustic, ignorant, and

savage people, were the less frequented by other teachers. After St. Cuthbert

had lived many years at Mailros, St. Eata, abbot also of Lindisfarne, removed

him thither, and appointed him prior of that larger monastery. By the perfect

habit of mortification and prayer the saint had attained to so eminent a spirit

of contemplation, that he seemed rather an angel than a man. He often spent

whole nights in prayer, and sometimes, to resist sleep, worked or walked about

the island whilst he prayed. If he heard others complain that they had been

disturbed in their sleep, he used to say, that he should think himself obliged

to any one that awaked him out of his sleep, that he might sing the praises of

his Creator, and labour for his honour. His very countenance excited those who

saw him to a love of virtue. He was so much addicted to compunction and

inflamed with heavenly desires, that he could never say mass without tears. He

often moved penitents, who confessed to him their sins, to abundant tears, by

the torrents of his own, which he shed for them. His zeal in correcting sinners

was always sweetened with tender charity and meekness. The saint had governed

the monastery of Lindisfarne, under his abbot, several years, when earnestly

aspiring to a closer union with God, he retired, with his abbot’s consent, into

the little isle of Farne, nine miles from Lindisfarne, there to lead an austere

eremitical life. The place was then uninhabited, and afforded him neither

water, tree nor corn. Cuthbert built himself a hut with a wall and trench about

it, and, by his prayers, obtained a well of fresh water in his own cell. Having

brought with him instruments of husbandry, he sowed first wheat, which failed;

then barley, which, though sowed out of season, yielded a plentiful crop. He

built a house at the entry of the island from Lindisfarne, to lodge the

brethren who came to see him, whom he there met and entertained with heavenly

conferences. Afterwards he confined himself within his own wall and trench, and

gave spiritual advice only through a window, without ever stirring out of his

cell. He could not however, refuse an interview with the holy abbess and royal

virgin Elfleda, whom her father King Oswi, had dedicated to God from her birth,

and who in 680, succeeded St. Hilda in the government of the abbey of Whitby.

This was held in the isle of Cocket, then filled with holy anchorets. This

close solitude was to our saint an uninterrupted exercise of divine love,

praise, and compunction; in which he enjoyed a paradise of heavenly delights,

unknown to the world.

In a synod of bishops, held by St. Theodorus at Twiford, on the river Alne, in

the kingdom of Northumberland, it was resolved, that Cuthbert should be raised

to the episcopal see of Lindisfarne. But as neither letters, nor messengers,

were of force to obtain his consent to undertake the charge, King Egfrid, who

had been present at the council, and the holy bishop Trumwin, with many others,

sailed over to his island, and conjured him, on their knees, not to refuse his

labours, which might be attended with so much advantage to souls. Their

remonstrances were so pressing, that the saint could not refuse going with

them, at least to the council, but weeping most bitterly. He received the episcopal

consecration at York, the Easter following, from the hands of St. Theodorus,

assisted by six other bishops. In this new dignity the saint continued the

practice of his former austerities; but remembering what he owed to his

neighbour, he went about preaching and instructing with incredible fruit, and

without any intermission. He made it every where his particular care to exhort,

feed, and protect the poor. By divine revelation he saw and mentioned to

others, at the very instant it happened, the overthrow and death of King

Egfrid, by the Picts, in 685. He cured, by water which he had blessed the wife

of a noble Thane, who lay speechless and senseless at the point of death, and

many others. For his miracles he was called the Thaumathurgus of Britain. But the

most wonderful of his miracles was that which grace wrought in him by the

perfect victory which it gave him over his passions. His zeal for justice was

most ardent; but nothing seemed ever to disturb the peace and serenity of his

mind. By the close union of his soul with God, whose will alone he sought and

considered in all things, he overlooked all temporal events, and under all

accidents his countenance was always cheerful, always the same: particularly in

bearing all bodily pains, and every kind of adversity with joy, he was

invincible. His attention to, and pure view of God in all events, and in all

his actions arose from the most tender and sweet love, which was in his soul a

constant source of overflowing joy. Prayer was his centre. His brethren discovered

sometimes that he spent three or four nights together in that heavenly

exercise, allowing himself very little or no sleep. When St. Ebba, the royal

virgin, sister to the kings St. Oswald and Oswi, abbess of the double monastery

of Coldingham, invited him to edify that house by his exortations, he complied,

and staid there some days. In the night, whilst others were asleep, he stole

out to his devotions according to his custom in other places. One of the monks

who watched and followed him one night, found that the saint, going down to the

sea-shore, went into the water up to the arm-pits, and there sung praises to

God. In this manner he passed the silent time of the night. Before the break of

day he came out, and having prayed awhile on the sands, returned to the

monastery, and was ready to join in morning lauds.

St. Cuthbert, foreseeing his death to approach, resigned his bishopric, which

he had held two years, and retired to his solitude in Farne Island, to prepare

himself for his last passage. Two months after he fell sick, and permitted

Herefrid, the abbot of Lindisfarne, who came to visit him, to leave two of his

monks to attend him in his last moments. He received the viaticum of the body

and blood of Christ from the hands of the abbot Herefrid, at the hour of

midnight prayer, and immediately lifting up his eyes, and stretching out his

hands, sweetly slept in Christ on the 20th day of March, 687. He died in the

island of Farne: but, according to his desire, his body was buried in the

monastery of Saint Peter in Lindisfarne, on the right side of the high altar.

Bede relates many miracles performed at his tomb; and adds, that eleven years

after his death, the monks taking up his body, instead of dust which they

expected, found it unputrified, with the joints pliable, and the clothes fresh

and entire. 2 They

put it into a new coffin, placed above the pavement, over the former grave: and

several miracles were there wrought, even by touching the clothes which covered

the coffin. William of Malmesbury 3 writes,

that the body was again found incorrupt four hundred and fifteen years

afterwards at Durham, and publicly shown. In the Danish invasions, the monks

carried it away from Lindisfarne; and after several removals on the continent,

settled with their treasure on a woody hill almost surrounded by the river

Were, formed by nature for a place of defence. They built there a church of stone,

which Aldhune, bishop of Lindisfarne, dedicated in 995, and placed in it the

body of St. Cuthbert with great solemnity, transferring hither his episcopal

see. 4 Many

princes enriched exceedingly the new monastery and cathedral, in honour of St.

Cuthbert. Succeeding kings, out of devotion to this saint, declared the bishop

a count palatine, with an extensive civil jurisdiction. 5 The