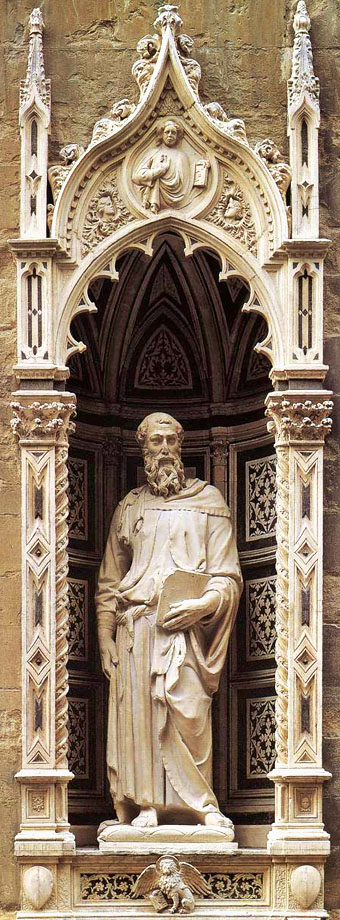

Donatello, Saint Mark, 1411–1413, Orsanmichele, Florence

Donatello, San Marco, 1411-1413, Chiesa di Orsanmichele, Firenze

Saint Marc

Un des quatre

évangélistes (Ier siècle)

Second dans l'ordre des évangiles synoptiques, serait-il l'inventeur du genre évangélique ? C'est possible puisque son livre, en mauvais grec, semé de sémitismes, fut composé très tôt à Rome, selon les données orales de Saint Pierre. Sans doute au plus tard en 70. L'auteur en serait le jeune Jean, surnommé Marc, fils de Marie chez qui la première communauté chrétienne de Jérusalem se réunissait pour prier (Actes 12. 12). Il accompagne Paul et Barnabé dans leur mission à Chypre. Peu après, il refuse de suivre Paul, en partance pour l'Asie Mineure. Il préfère rentrer à Jérusalem. Saint Paul lui en voudra, un moment, de ce lâchage : il préféra se séparer de Barnabé plutôt que de reprendre Marc (Acte 15. 39) Mais Marc se racheta et deviendra le visiteur du vieux prisonnier à Rome. Dans le même temps, saint Pierre le traite comme un fils (1ère lettre de Pierre 5. 13). Certains considèrent que saint Marc aurait été l'évangélisateur de l'Egypte. Ce n'est pas invraisemblable. D'autres affirment que son corps serait désormais à Venise. Après tout, pourquoi pas ? En tous cas, il fut un fidèle secrétaire pour saint Pierre dont il rédigea les "Mémoires", qui sont l'évangile selon saint Marc, à l'intention des Romains.

De Jérusalem, il suivit d'abord saint Paul dans ses voyages missionnaires, puis

s'attacha aux pas de saint Pierre, qui l'appelait son fils et dont, selon la

tradition, il recueillit dans son Évangile la catéchèse aux Romains. Il aurait

enfin fondé l'Église d'Alexandrie.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1033/Saint-Marc.html

SAINT MARC

Évangéliste, Évêque

d'Alexandrie

(mort vers l'an 75)

Saint Marc était

probablement de la race d'Aaron; il était né en Galilée. Il semble avoir fait

partie du groupe des soixante-douze disciples du Sauveur; mais il nous apparaît

surtout dans l'histoire comme le compagnon fidèle de l'apostolat de saint

Pierre.

C'est sous l'inspiration

du chef des Apôtres et à la demande des chrétiens de Rome qu'il écrivit

l'Évangile qui porte son nom. Marc cependant ne suivit pas saint Pierre jusqu'à

son glorieux martyre; mais il reçut de lui la mission spéciale d'évangéliser

Alexandrie, l'Égypte et d'autres provinces africaines.

Le disciple ne faillit

pas à sa tâche et porta aussi loin qu'il put, dans ces contrées, le flambeau de

l'Évangile. Alexandrie en particulier devint un foyer si lumineux, la

perfection chrétienne y arriva à un si haut point, que cette Église, comme

celle de Jérusalem, ne formait qu'un coeur et qu'une âme dans le service de

Jésus-Christ. La rage du démon ne pouvait manquer d'éclater.

Les païens endurcis

résolurent la mort du saint évangéliste et cherchèrent tous les moyens de

s'emparer de lui. Marc, pour assurer l'affermissement de son oeuvre, forma un

clergé sûr et vraiment apostolique, puis échappa aux pièges de ses ennemis en

allant porter ailleurs la Croix de Jésus-Christ. Quelques années plus tard, il

eut la consolation de retrouver l'Église d'Alexandrie de plus en plus

florissante.

La nouvelle extension que

prit la foi par sa présence, les conversions nombreuses provoquées par ses

miracles, renouvelèrent la rage des païens. Il fut saisi et traîné, une corde

au cou, dans un lieu plein de rochers et de précipices. Après ce long et

douloureux supplice, on le jeta en prison, où il fut consolé, la nuit suivante,

par l'apparition d'un ange qui le fortifia pour le combat décisif, et par

l'apparition du Sauveur Lui-même.

Le lendemain matin, Marc

fut donc tiré de prison; on lui mit une seconde fois la corde au cou, on le

renversa et on le traîna en poussant des hurlements furieux. La victime,

pendant cette épreuve douloureuse, remerciait Dieu et implorait Sa miséricorde.

Enfin broyé par les rochers où se heurtaient ses membres sanglants, il expira

en disant: "Seigneur, je remets mon âme entre Vos mains."

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_marc.html

A

painted miniature in an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609,

Qui est saint Marc l’évangéliste ?

Jacques

Gauthier | 25 avril 2017

Si l’évangile selon saint

Marc ne donne aucune information sur son auteur, on en apprend plus sur lui

dans les Actes des Apôtres ou les épîtres de Paul et de Pierre.

L’évangile selon saint

Marc ne dit rien rien de son auteur. Nous le connaissons par les Actes des

Apôtres, les épîtres de Paul et de Pierre. On parle d’un certain

« Jean », surnommé « Marc », en grec Markos, qui est

en relation avec Pierre à Jérusalem. Pierre mentionne son nom quand il s’évade

de la prison d’Hérode Agrippa 1er : « Il se rendit à la maison de

Marie, la mère de Jean surnommé Marc, où se trouvaient rassemblées un certain

nombre de personnes qui priaient » (Ac

12, 12).

Collaborateur de Pierre

et Paul

Marc accompagne Paul et

Barnabé dans une première mission d’évangélisation en Asie Mineure. « Ils

avaient Jean-Marc comme auxiliaire » (Ac

13, 5). Âgé autour de la vingtaine, il leur sert d’adjoint dans plusieurs

voyages. Paul décide de quitter Chypre pour la ville de Pergé. Sur la

route, Marc s’oppose à Paul et repart pour Jérusalem, le laissant avec Barnabé

en direction de la Pisidie. Au début des années 50, Marc et Barnabé repartent

évangéliser l’île de Chypre, sans l’approbation de Paul :

Paul dit à Barnabé : «

Retournons donc visiter les frères en chacune des villes où nous avons annoncé

la parole du Seigneur, pour voir où ils en sont. » Barnabé voulait emmener

aussi Jean appelé Marc. Mais Paul n’était pas d’avis d’emmener cet homme, qui

les avait quittés à partir de la Pamphylie et ne les avait plus accompagnés

dans leur tâche. L’exaspération devint telle qu’ils se séparèrent l’un de

l’autre. Barnabé emmena Marc et s’embarqua pour Chypre (Ac

15, 36-39).

Paul se réconcilie avec

Marc vers l’an 62 quand celui-ci le retrouve à Rome alors qu’il est prisonnier.

« Vous avez les salutations d’Aristarque, mon compagnon de captivité, et

celles de Marc, le cousin de Barnabé – vous avez reçu des instructions à son

sujet : s’il vient chez vous, accueillez-le » (Col

4, 10).

Marc devient l’interprète

et le secrétaire de Pierre, qui séjourne alors à Rome ; il participe aux

travaux apostoliques de celui-ci. Il l’apprécie tellement qu’il l’appelle

« mon fils » : « La communauté qui est à Babylone, choisie

comme vous par Dieu, vous salue, ainsi que Marc, mon fils » (1

P 5, 13). Il excelle dans ce rôle de second. C’est de cette époque que date

son Évangile, composé de plusieurs documents antérieurs, dans lesquels il met

sa touche personnelle. Le style est vivant et direct. Pierre lui a donné des

informations précises sur Jésus, lui partageant ses souvenirs : la

guérison de sa belle-mère, l’appel de Lévi, la résurrection de la fille de

Jaïre, la transfiguration de Jésus, l’expulsion des vendeurs du temple,

l’onction à Béthanie, l’arrestation de Jésus, son reniement. Marc s’en est

souvenu au moment d’écrire son Évangile vers 65, le premier en date. Il sera

une source précieuse pour les évangiles de Matthieu et de Luc, écrits entre dix

et quinze ans plus tard. Lire

la suite sur le blogue de Jacques Gauthier

Extrait de la nouvelle

édition revue et augmentée, à paraître fin 2017 : Les

saints, ces fous admirables.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/2017/04/25/qui-est-saint-marc-levangeliste/

Saint

Mark, illumination on parchment,

1524, Library of Congress

L'auteur du deuxième évangile ne se nomme pas, mais certains ont cru pouvoir

l'identifier au jeune homme qui s'enfuit lors de l'arrestation du Seigneur : Et

un jeune homme le suivait, un drap jeté sur son corps nu. Et on l'arrête, mais

lui, lâchant le drap s'enfuit tout nu (évangile selon saint Marc XIV 51-52).

D'après Jean le Presbytre

dont le témoignage rapporté par Papias (évêque d'Hiérapolis en Phrygie vers le

premier quart du II° siècle) est cité par Eusèbe de Césarée dans un passage de

son Histoire ecclésiastique (Livre III, chapitre XXXIX, 15) :

Voici ce que le presbytre

disait : Marc, qui avait été l'interprète de Pierre, écrivit exactement

tout ce dont il se souvint, mais non dans l'ordre de ce que le Seigneur avait

dit ou fait, car il n'avait pas entendu le Seigneur et n'avait pas été son

disciple, mais bien plus tard, comme je disais, celui de Pierre. Celui-ci

donnait son enseignement selon les besoins, sans se proposer de mettre en ordre

les discours du Seigneur. De sorte que Marc ne fut pas en faute, ayant écrit

certaines choses selon qu'il se les rappelait. Il ne se souciait que d'une

chose : ne rien omettre de ce qu'il avait entendu, et ne rien rapporter que de

véritable.

Saint Justin (vers 150)

cite comme appartenant aux Mémoires de Pierre un trait qui ne se trouve que

dans l'évangile selon saint Marc (Dialogue avec Tryphon, n°106) : surnom de

Boarnergès (fils du tonnerre) donné à Jacques et Jean, fils de Zébédée (Saint

Marc III 16-17).

Saint Irénée (vers 180)

dit qu'après la mort de Pierre et de Paul, Marc, disciple et interprète de

Pierre, nous transmit lui aussi par écrit ce qui avait été prêché par

Pierre(Contra haereses, Livre III, chapitre I, 1).

Tertullien attribue à

Pierre ce que Marc a écrit (Adversus Marcionem, Livre IV, chapitre V).

La tradition le désigne

donc comme un disciple de Pierre et son interprète authentique (Saint Clément

d'Alexandrie, Origène - selon ce que Pierre lui avait enseigné- et saint Jérôme

- Marc, interprète de l'apôtre Pierre et premier évêque d'Alexandrie).

Les anciens l'ont

identifié avec le Marc ou le Jean-Marc des Actes des Apôtres et des épîtres

pauliniennes : son nom hébreux aurait été Jean et son surnom romain aurait été

Marc (Marcus qui a donné le grec Marcos), usage que l'on rencontre pour Joseph,

surnommé Justus (Actes des Apôtres I 23), ou pour Simon, surnommé Niger (Actes

des Apôtres XIII 1) ; il serait le fils d'une Marie, probablement veuve, chez

qui se réunissait la première communauté chrétienne de Jérusalem et chez qui

saint Pierre se réfugia après sa délivrance de la prison (Actes des Apôtres XII

12) ; celui-ci accompagna Paul et Barnabé, son propre cousin (Colossiens IV 10)

dans un premier voyage (Actes des Apôtres XII 25), puis se sépara deux à Pergé

en Pamphylie (Actes des Apôtres XIII 13) avant de repartir pour Chypre avec

Barnabé (Actes des Apôtres XV 39) ; on le retrouve à Rome près de saint Paul

prisonnier (Billet à Philémon 24) qui le charge d'une mission en Asie Mineure

(Colossiens IV 10) et finalement l'appelle auprès de lui (II Timothée IV 11) ;

la mention à Rome de Marc comme le fils très cher de l'apôtre Pierre (I Pierre

V 13) fait penser que Marc a été baptisé par Pierre et qu'il se mit à son

service après la mort de Paul.

Eusèbe de Césarée

rapporte que Marc aurait été le fondateur de l'Eglise d'Alexandrie : Pierre

établit aussi les églises d'Egypte, avec celle d'Alexandrie, non pas en

personne, mais par Marc, son disciple. Car lui-même pendant ce temps s'occupait

de l'Italie et des nations environnantes ; il envoya don Marc, son disciple,

destiné à devenir le docteur et le conquérant de l'Egypte (Histoire ecclésiastique

Livre II, chapitre XVI), ce qu'un texte arménien fixe à la première année du

règne de Claude (41) et saint Jérôme la troisième (43) ; Eusèbe dit qu'il

établit son successeur, Anien, la huitième année du règne de Néron (62).

L'attribut de saint Marc est le lion parce que son évangile commence par la prédication de saint Jean-Baptiste dans le désert et que le lion est l'animal du désert (Evangile selon saint Marc I 12-13).

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/04/25.php

Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 1857, Stundenbuch der Maria von Burgund. In: Franz Unterkirchner (Hrsg.): Das Stundenbuch der Maria von Burgund. Codex Vindobonensis 1857 der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek (Glanzlichter der Buchkunst), Darmstadt 1993.

MARC, disciple et interprète de Pierre, écrivit, à la demande de ses

frères de Rome, un évangile résumé d'après ce qu'il avait recueil. li de la

bouche de Pierre lui-même. Cet apôtre l'ayant lu, l'approuva, le fit publier,

et ordon na qu'il fût lu dans les églises. Ces faits son attestés par Clément

dans le sixième livre de ses Hypotyposes. Pappias, évêque

d'Hiéropolis, a fait mention de Marc, et Pierre, dans première épître, s'exprime

ainsi : « Vos confrères de Babylone et Marc, mon fils chéri vous saluent. » Par

le mot de Babylone il désigne figurément l'Eglise de Rome. Marc alla ensuite en

Egypte, emportant avec lui l'évangile qu'il avait rédigé. Il commença par

prêcher la religion chrétienne à Alexandrie, y fonda une Eglise, et obtint tant

d'influence par sa science et par la pureté de ses moeurs que les sectateurs de

Jésus-Christ le prirent pour modèle. Comme les membres de cette première Eglise

suivaient encore quelques pratiques judaïques, Philon, le plus grand des

écrivains juifs, composa un traité sur le genre de vie des néophytes

d'Alexandrie, croyant faire le panégyrique de sa nation. Les chrétiens de

Jérusalem mettaient, au rapport de Luc, tous leurs biens en commun: Philon prétend

qu'il en était de même à Alexandrie sous les enseignements de Marc. Cet

évangéliste mourut la huitième année du règne de Néron, et fut enterré dans

cette ville. Il eut, pour successeur Anianus.

Saint Jérôme. Tableau

des écrivains ecclésiastiques, ou Livre des hommes illustres.

SOURCE : http://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/jerome/002.htm

Saint Marc, le premier à

avoir raconté la vie de Jésus

Agnès

Pinard Legry | 24 avril 2018

À l’occasion de la

Saint-Marc ce 25 avril, la rédaction d’Aleteia s’est intéressée à cet homme

dont l’Évangile est le plus court et le plus ancien.

« Commencement de

l’Évangile de Jésus, Christ, Fils de Dieu ». Dès le premier verset, Marc

donne des éléments sur celui dont son Évangile n’aura de cesse de

s’interroger : qui est cet homme, Jésus ? Second dans l’ordre des

évangiles synoptiques, saint Marc pourrait bien être l’inventeur du genre

évangélique. Pourtant, il a longtemps été « délaissé » en raison de

son style. « L’Évangile de Marc est le plus ancien, il donne la trame de

celui de Matthieu et de Luc. Pourtant, il a longtemps été considéré comme un

texte frustre, maladroit. Il a fallu attendre la réforme liturgique pour le

remettre à l’honneur », détaille à Aleteia Éric Julien, accompagnateur de

confirmands et de catéchumènes et auteur du livre Plongez

dans l’Évangile avec Marc.

D’une lecture simple et

descriptive, l’Évangile de Marc peut parfois paraître naïf. Pour Jean-Pierre

Rosa, philosophe et éditeur, saint Marc est pourtant celui qui a eu

« le premier, le courage et l’humilité de prendre sa plume pour “raconter

Jésus”, le faire résonner pour les hommes et les femmes de son temps ». Il

est celui « qui a ouvert la voie ». « L’Évangile de Marc

est celui avec lequel il faut se laisser guider. Ce texte est déroutant par

l’authenticité avec laquelle Marc décrit la foi, ou plutôt le manque de foi des

disciples. Il ne fait aucune concession devant leur fragilité. On a toujours

l’impression que la foi ne supporte pas le doute. Mais avec Marc on comprend

que c’est tout l’inverse. Ces hommes qui ont connu Jésus ont eu du mal à

reconnaître en lui quelqu’un de pleinement homme et de pleinement Dieu »,

explique Éric Julien.

Jésus, en toute humanité

« Oser prendre le

temps de lire en entier cet Évangile, c’est prendre le risque de la rencontre

de Jésus qui sait s’intéresser aux personnes, à leur vie, à leurs souffrances,

à leurs attentes », a récemment écrit le

père Pierre-Yves Pecqueux, secrétaire général adjoint de la Conférence des

évêques de France. Lire cet Évangile, c’est aussi « laisser percer la

foi qui habite le cœur de ceux qui s’adressent à Jésus et que Jésus

reconnaît : “Ta foi est grande”. La rencontre de la souffrance des hommes

marque profondément son témoignage qui trouvera son sommet à la

crucifixion ».

Partir à la rencontre de

Jésus avec saint Marc revient à cheminer aux côtés de Jésus dans son

environnement, en toute humanité. Cet Évangile pousse le lecteur, le croyant et

le curieux à répondre à une question, tout à la fois brûlante d’actualité et

éternelle : pour nous, qui est ce « Jésus, Christ, Fils de

Dieu » ?

[VIDÉO] Marc, un saint

reconnaissable entre tous !

Mélina de

Courcy - Anthony Cormy - publié le 24/04/24

En la fête de saint Marc,

découvrez la richesse des représentations artistiques de l'évangéliste à partir

d'une fresque réalisée par Friedrich Stummels.

Il est le saint patron

des écrivains ! Le peintre allemand Friedrich Stummels a réalisé cette fresque

de saint Marc l’évangéliste pour la coupole de la basilique du Rosaire à

Berlin.

Sur l’azur parsemé de

nuages rose, Saint Marc l’évangéliste est représenté assis, un calame dans la

main, l’autre posé sur une reliure à côté d’un encrier et d’un coffret de

parchemin roulé. Il est escorté du lion ailé. Pourquoi une telle iconographie ?

Voyez ces quelques

détails pour la comprendre. Premièrement, l’emblème de Marc est le lion,

car l’un des premiers

versets de son évangile évoque le désert où l’on entend le rugissement

du lion. Deuxièmement, l’Évangile qu’il est en train d’écrire est le premier et

le plus court des quatre évangiles.

Troisièmement, il

évangélise avec Pierre à Rome, puis il fonde l’église d’Alexandrie en Égypte,

où il meurt martyr un 25 avril vers l’an 75. C’est pourquoi il regarde en

arrière, ses écrits font mémoire. Lors de son passage à Venise, un ange lui

aurait dit la phrase qui deviendra la devise de la ville : “Que la paix soit

avec toi, Marc, mon évangéliste.”

Eh bien, aujourd’hui, en

la fête de saint Marc, que la paix soit avec vous !

Lire aussi :[VIDEO] L’Annonciation dans le jardin de Maurice Denis

Lire aussi :[VIDÉO] La décollation de Jean-Baptiste, ce tableau que Caravage

n’a pas signé

Lire aussi :Saint Pierre et saint Marc aussi n’avaient pas tenu leurs bonnes

résolutions…

Vladimir Borovikovsky (1757–1825). Saint Marc Évangéliste, 1804, Kazan Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

Parmi les 4

Évangiles, Marc est l’auteur du second, lequel est en fait le premier

du point de vue de sa rédaction. Marc avait un nom double : Jean-Marc. Il

naquit à Jérusalem et la première communauté chrétienne se rassemblait parfois

dans la maison de sa mère (Actes 12, v. 12). Jean Marc ne fait pas partie des

douze Apôtres de Jésus, mais peut-être est-il présent au jardin des Oliviers

lors de l’agonie du Seigneur. On a vu souvent comme la signature discrète de

son Evangile le trait suivant :

"Tous abandonnèrent

Jésus en prenant la fuite. Un jeune homme le suivait, n'ayant qu'un drap sur le

corps. On l'arrête : mais lui, lâchant le drap, s'enfuit tout nu" (Mc. 14.

50-52).

Après la Pentecôte,

encore très jeune, Marc est l'un de ces hommes prêts à partir vers les Nations

païennes pour leur porter l'Évangile. Il participe au premier grand départ,

vers l'année 45, avec Paul et Barnabé son parent. Tout alla bien au début, mais

quand il s'agit d'affronter l'entrée en Asie mineure par les monts du Taurus,

Marc panique et retourne chez sa mère à Jérusalem. Plus tard, pour le second

voyage missionnaire, Barnabé insiste auprès de Paul pour que Marc parte avec

eux. "Mais Paul ne fut pas d'accord de reprendre comme compagnon celui qui

les avait abandonnés en Pamphylie. Leur désaccord s'aggrava tellement que

chacun partit de son côté: Barnabé avec Marc s'embarqua pour Chypre, tandis que

Paul s'adjoignait Silas" (Actes 15. 37-40). A la fin à Rome, au moment de

la captivité et du martyre de Pierre et de Paul, Marc se retrouve intime de

l'un et l'autre. On ne sait pas comment se termina la vie de Jean-Marc,

rédacteur de l'Évangile, où il se montre très influencé par le témoignage de

Pierre qui l'appelait son fils. Saint Marc est spécialement vénéré en Egypte à

Alexandrie. Il est aussi le saint patron de Venise. Une douzaine d'autres Marc

ont également illustré ce beau prénom.

Rédacteur : Frère Bernard Pineau, OP

SOURCE : http://www.lejourduseigneur.com/Web-TV/Saints/Marc-Evangeliste

Saint Marc, Évangéliste

Le Lion évangélique qui

assiste devant le trône de Dieu, avec l’Homme, le Taureau et l’Aigle, se montre

aujourd’hui sur le Cycle. Ce jour a vu Marc s’élancer de la terre au ciel, le

front ceint de la triple auréole de l’Évangéliste, de l’Apôtre et du Martyr.

De même que les quatre

grands Prophètes, Isaïe. Jérémie, Ézéchiel et Daniel, résument en eux la

prédiction en Israël ; ainsi Dieu voulait que la nouvelle Alliance reposât sur

quatre textes augustes, destinés à révéler au monde la vie et la doctrine de son

Fils incarné. Les quatre Évangiles, nous disent les anciens Pères, sont les

quatre fleuves qui arrosaient le jardin des délices, et ce jardin était la

figure de l’Église à venir. Le premier des quatre oracles de la nouvelle

Alliance est Matthieu, qui avant tout autre initia les hommes a la vie et à la

doctrine de Jésus : nous verrons poindre son astre en septembre ; le second est

Marc, qui nous illumine aujourd’hui ; le troisième est Luc, dont nous

attendrons le lever jusqu’en octobre ; le quatrième est Jean, que nous avons

connu près de la crèche de l’Emmanuel en Bethléhem. Arrêtons-nous à contempler

les grandeurs du second.

Marc est le disciple

chéri de Pierre, le brillant satellite du Soleil de l’Église. Son Évangile a

été écrit à Rome, sous les yeux du Prince des Apôtres. Le récit de Matthieu

avait déjà cours dans l’Église ; mais les fidèles de Rome désiraient y joindre

la narration personnelle de leur Apôtre. Pierre ne consent pas à écrire

lui-même ; il engage son disciple à prendre la plume, et l’Esprit-Saint conduit

la main du nouvel Évangéliste. Marc s’attache à la narration de Matthieu ; il

l’abrège, mais en même temps il la complète. Un mot, un trait de développement,

viennent attester à chaque page que Pierre, témoin et auditeur de tout, a suivi

de près le travail de son disciple. Mais le nouvel Évangéliste passera-t-il

sous silence ou cherchera-t-il à atténuer la faute de son maître ? Loin de là ;

l’Évangile de Marc sera plus dur que celui de Matthieu dans le récit du

reniement de Pierre. On sent que les larmes amères provoquées par le regard de

Jésus dans la maison de Caïphe, n’ont pas encore cessé de couler. Le travail de

Marc étant terminé, Pierre le reconnut et l’approuva, les Églises accueillirent

avec transportée second récit des mystères du salut du monde, et le nom de Marc

devint célèbre par toute la terre.

Matthieu, qui ouvre son

Évangile par la généalogie humaine du Fils de Dieu, avait réalise le type

céleste de l’Homme ; Marc remplit celui du Lion ; car il débute par le récit de

la prédication de Jean-Baptiste, rappelant que le rôle de ce Précurseur du

Messie avait été annoncé par Isaïe, quand il avait parlé de la Voix de celui

qui crie dans le désert ; voix du lion qui ébranle les solitudes par ses

rugissements.

La carrière d’Apôtre s’ouvrit

devant Marc lorsqu’il eut écrit son Évangile. Pierre le dirigea d’abord sur

Aquilée, où il fonda une insigne Église ; mais c’était trop peu pour un

Évangéliste. Le moment était venu où l’Égypte, la mère de toutes les erreurs,

devait recevoir la vérité, où la superbe et tumultueuse Alexandrie allait voir

s’élever dans ses murs la seconde Église de la chrétienté, le second siège de

Pierre. Marc fut destiné par son maître à ce grand œuvre. Par sa prédication,

la doctrine du salut germa, fleurit et produisit le bon grain sur cette terre

la plus infidèle de toutes ; et l’autorité de Pierre se dessina dès lors,

quoique à des degrés différents, dans les trois grandes cités de l’Empire :

Rome, Alexandrie et Antioche.

Sous l’inspiration de

Marc, la vie monastique préluda à ses saintes destinées, dans Alexandrie même,

par l’institution chrétienne des Thérapeutes. L’intelligence de la vérité

révélée prépara de bonne heure, dans ce grand centre des études humaines, les

éléments de la brillante école chrétienne qui commença d’y fleurir dès le

second siècle. Tels furent les effets de l’influence du disciple de Pierre dans

la seconde Église du monde.

Mais la gloire de Marc

fût restée incomplète, si l’auréole du martyre ne fût pas venue la couronner.

Les succès de la prédication du saint Évangéliste ameutèrent contre lui les

fureurs de l’antique superstition égyptienne. Dans une fête de Sérapis, Marc

fut maltraité par les idolâtres, et on le jeta dans un cachot. Ce fut là que le

Seigneur ressuscité, dont il avait raconté la vie et les œuvres divines, lui

apparut la nuit, et lui dit ces paroles célèbres qui sont la devise de

l’antique république de Venise : « Paix soit avec toi, Marc, mon Évangéliste !

» A quoi le disciple ému répondit : « Seigneur ! » Sa joie et son amour ne

trouvèrent pas d’autres paroles. Ainsi Madeleine, au matin de Pâques, avait

gardé le silence après ce cri du cœur : « Cher Maître ! » Le lendemain, Marc

fut immolé par les païens ; mais il avait rempli sa mission sur la terre, et le

ciel s’ouvrait au Lion, qui allait occuper au pied du trône de l’Ancien des

jours la place d’honneur où le Prophète de Pathmos le contempla dans sublime

vision.

Au IXe siècle, l’Église

d’Occident s’enrichit de la dépouille mortelle de Marc. Ses restes sacrés

fuient transportés à Venise, et sous les auspices du Lion évangélique

commencèrent pour cette ville les glorieuses destinées qui ont duré mille ans.

La foi en un si grand patron opéra des merveilles dans ces îlots et ces lagunes

d’où s’éleva bientôt une cite aussi puissante que magnifique. L’art byzantin

construisit l’imposante et somptueuse Église qui fut le palladium de la reine

des mers, et la nouvelle république frappa ses monnaies à l’effigie du Lion de

saint Marc : heureuse si, plus filiale envers Rome et plus sévère dans ses

mœurs, elle n’eût jamais néré de sa gravité antique, ni de la foi de ses plus

beaux siècles !

Réunissons à la gloire de

Saint Marc les éloges de l’Orient et de l’Occident. Nous commencerons par cette

Hymne que lui consacra au IXe siècle saint Paulin, l’un de ses successeurs sur

le siège d’Aquilée.

HYMNE.

Déjà par le monde entier

elle répand son éclat, cette Lumière céleste qui la splendeur du Père, et de

laquelle procède la lumière créée qui nous réjouit de son éclat ; ce flambeau

qui dans sa splendeur n’éprouve jamais de défaillance et éclaire notre ciel, en

dissipant les ombres qui couvraient le monde.

Le bienheureux Marc,

docteur évangélique, avait reçu dans son cœur un rayon de cette lumière sacrée

; reflet ardent et lumineux, il chassa devant lui les ténèbres dont le monde

était enveloppé.

Il fut une des sept

blanches colonnes qui soutiennent l’édifice, l’un des sept chandeliers d’or, un

astre dont l’éclat parcourt l’univers entier ; placé à la base. il soutient,

comme un de leurs quatre fondements, les Églises qui sont sous le ciel.

Ézéchiel, l’antique et

saint prophète, Jean qui reposa sur le sein du Christ, l’ont vu l’un et l’autre

la forme d’un animal mystique, sous le symbole du Lion qui fait retentir le

désert de ses rugissements.

Le bienheureux Pierre

l’envoya vers la ville d’Aquilée, cité fameuse en ces temps ; Marc y sema la

parole sainte, et sa moisson s’élevait au centuple, lorsqu’il la transporta

dans les greniers célestes.

Ce fut lui qui établit

dans cette ville l’Église du Christ, la posant survie solide fondement de la

loi, sur cette pierre sans tache, que ni les débordements du fleuve, ni la

fureur des vents, ni les torrents, ni les pluies, ne sauraient ébranler.

Il en revint le front

ceint, d’une couronne qui mêlait à ses palmes et à ses lauriers l’éclat des

roses et des lis ; athlète combattant du Christ, il portait ce diadème

glorieux, lorsqu’il rentra dans Rome, conduit parce Maître divin.

Ce fut alors que, rempli de

l’Esprit-Saint, il se dirigea vers Alexandrie, et on l’entendit dans toute

l’étendue de l’Égypte annoncer aux hommes que le Fils unique du l’ère adorable

était venu sur la terre pour le salut du monde.

Mais ce peuple endurci et

cruel préparait des tourments au soldat du Christ. Un jour il le chargea

déchaînes, le blessa avec la pointe de ses javelots, déchira sa chair à coups

de fouets, et l’enferma dans une noire prison.

Marc fut donc le premier

qui porta le nom du Dieu suprême dans Alexandrie ; il dédia au Christ une

basilique qui fut consacrée par l’effusion de son sang, et à laquelle il donna

la sainte foi pour rempart.

Gloire et empire soit au

Père ! à vous aussi, Fils de Dieu, plus haut des cieux ! à l’Esprit-Saint

honneur et puissance ! à l’indivisible Trinité, nos hommages dans les siècles

éternels ! Amen.

L’Église grecque, dans

ses Ménées, célèbre à son tour le saint Évangéliste par de nombreuses strophes,

entre lesquelles nous choisissons les suivantes.

(DIE XXV APRILIS.)

Célébrons, ô fidèles, par

de dignes louanges l’écrivain sacré, le grand patron de l’Égypte, et disons : O

Marc rempli de sagesse, par ton enseignement et tes prières conduis-nous tous,

comme un Apôtre, à cette vie tranquille qui ne connaît plus les tempêtes.

Tu fus d’abord le

compagnon des voyages de celui qui est le Vase d’élection, et avec lui tu

parcourus toute la Macédoine ; venu ensuite à Rome, tu apparus en cette ville

comme l’interprète de Pierre, et après de dignes combats soutenus pour Dieu,

l’Égypte fut le lieu de ton repos.

Tu rendis la vie aux âmes

brûlées de soif, en faisant tomber sur elles la blanche neige de ton Évangile ;

c’est pour cela, divin Marc, que Alexandrie célèbre aujourd’hui ta fête avec

nous par des chants magnifiques, et s’incline avec respect devant tes reliques.

Heureux Marc, tu t’es

désaltéré au torrent des délices célestes, et tu as jailli du Paradis comme un

fleuve de paix dont les eaux sont éclatantes de lumière, arrosant la face de la

terre par les ruisseaux de ta prédication évangélique, versant les flots de ta

doctrine divine sur les plantations de l’Église.

Si Moïse autrefois

engloutit les Égyptiens dans es abîmes de la mer, c’est toi, ô Marc digne de

toute louange, qui par la sagesse de tes enseignements les as retirés du gouffre

de l’erreur, étant assisté du divin pouvoir de celui qui a daigné être pèlerin

dans ce pays, et a détruit dans la Force de son bras les idoles que la main de

l’homme avait faites.

O divin Marc, tu as été

la plume de l’écrivain sage et rapide, en racontant d’une façon merveilleuse

l’incarnation du Christ, et annonçant dans un splendide langage les paroles de

l’éternelle vie qui sont rapportées dans ton livre ; adresse au Seigneur tes

prières en faveur de ceux qui célèbrent et honorent ta glorieuse mémoire.

O Marc digne de louange,

par ton Évangile tu as parcouru la terre entière ; elle était couverte des

ténèbres de l’idolâtrie ; tu l’as éclairée comme un soleil des rayons de la foi

: prie Dieu maintenant qu’il daigne octroyer à nos âmes la paix et sa grande

miséricorde.

Apôtre Marc, tu as

accompli ta prédication dans la région où régna tout d’abord la folie de

l’impiété ; messager de Dieu, l’éclat de tes paroles dissipa les ombres de

l’Égypte ; demande aujourd’hui à Dieu qu’il nous donne la paix et sa grande

miséricorde.

Disciple de Pierre, qui

fut maître de la sagesse, honoré de son adoption, Marc, digne de toute louange,

tu es devenu l’interprète des mystères du Christ et le cohéritier de sa gloire.

Ta voix a retenti par

toute la terre ; la vertu de tes paroles, comme la trompette de David, a

résonné jusqu’aux confins du monde, nous annonçant le salut et une nouvelle

naissance.

Tes paroles ont été comme

de doux ruisseaux de piété, et toi tu as été comme la montagne divine d’où ils

émanent, toute rayonnante des feux du Soleil spirituel de la grâce, ô Marc très

heureux !

Tu as jailli de la maison

du Seigneur comme une source, et tu as arrosé les âmes altérées des eaux

abondantes de l’Esprit-Saint, faisant produire à leur stérilité des fruits

abondants, ô bienheureux Apôtre !

Pierre, le prince des

Apôtres, t’a initié à sa merveilleuse doctrine ; il t’a chaîné d’écrire

l’Évangile sacré, et t’a désigné comme le ministre de la grâce ; alors tu as

fait briller à nos yeux la lumière qui fait connaître Dieu.

La grâce de l’Esprit-Saint

étant descendue sur toi. Apôtre, tu as anéanti les subtilités de l’éloquence

humaine, et semblable à un pécheur, tu as entraîné an Seigneur dans ton filet

toutes les nations, ô Marc digne de tout éloge, prédicateur du divin Évangile.

Tu as été le digne

disciple du Prince des Apôtres ; comme lui tu as proclame-le Christ Fils de

Dieu ; tu as établi sur la Pierre de vérité ceux qui flottaient au vent de

l’erreur. Établis-moi aussi sur cette Pierre, ô Marc plein de sagesse ; dirige

les pas de mon âme, afin que j’échappe aux pièges de l’ennemi, et que je puisse

te glorifier sans obstacles, o toi qui as répandu la lumière sur tous les

hommes en leur adressant l’Évangile divin.

Vous êtes, ô Marc, le

Lion mystérieux attelé avec l’Homme, le Taureau et l’Aigle, au char sur lequel

le Roi des rois s’avance à la conquête du monde. Dès l’ancienne Alliance,

Ézéchiel vous vit dans le ciel, et Jean, le Prophète de la Loi nouvelle, vous a

reconnu près du trône de Jéhovah. Quelle gloire est la vôtre ! Historien du

Verbe fait chair, vous racontez à toutes les générations ses titres à l’amour

et à l’adoration des hommes ; l’Église s’incline devant vos récits, et les

proclame inspirés par l’Esprit-Saint.

Nous vous avons entendu

au jour même de la Pâque nous raconter la résurrection de notre Sauveur ;

faites, ô saint Évangéliste, que ce divin mystère produise en nous tous ses

fruits ; que notre cœur, comme le vôtre, s’attache au divin Ressuscité, afin

que nous le suivions partout dans cette vie nouvelle qu’il nous a ouverte en

ressuscitant le premier. Demandez-lui qu’il daigne nous donner sa paix, comme

il l’a donnée à ses Apôtres en leur apparaissant dans le Cénacle, comme il vous

la donna à vous-même dans la prison.

Glorieux Marc, vous fûtes

le disciple chéri de Pierre ; Rome s’honore de vous avoir possédé dans ses murs

; priez aujourd’hui pour le successeur de Pierre votre maître, pour l’Église

Romaine battue par la tempête Lion évangélique, implorez le Lion de la tribu de

Juda en faveur de son peuple ; réveillez-le de son sommeil ; priez-le de se

lever dans sa force : par son seul aspect, il dissipera tous les ennemis.

Apôtre de l’Égypte,

qu’est devenue votre florissante Église d’Alexandrie, le second siège de

Pierre, empourpré de votre sang ? Les ruines mêmes ont péri. Le vent brûlant de

l’hérésie avait désolé l’Égypte, et Dieu dans sa colère déchaîna sur elle, il y

a douze siècles, le torrent de l’islamisme. Ces contrées doivent-elles renoncer

pour jamais à voir briller de nouveau le flambeau de la foi, jusqu’à l’arrivée

du Juge des vivants et des morts ? Nous l’ignorons : mais au milieu des

événements qui se succèdent, nous osons vous prier, ô Marc, d’intercéder pour

ces régions que vous avez évangélisées, et où les âmes sont aussi dévastées que

le sol.

Vous vous souviendrez

aussi de Venise, ô Marc ! Sa couronne est tombée, peut-être sans retour ; mais

là vit encore ce peuple dont les ancêtres se donnèrent à vous. Conservez la foi

dans son sein ; faites qu’il prospère, qu’il se relevé de ses épreuves, qu’il

rende gloire à Dieu qui l’a châtié dans sa justice. Toute nation qui s’unit à

l’Église sera bénie : que Venise revienne aux traditions de son antique

fidélité à Rome ; et qui sait si le Seigneur, fléchi par vos instances, ô

céleste protecteur, ne rouvrira pas pour elle le cours de ces nobles destinées

qui ne s’arrêtèrent qu’au jour où, devenue infidèle à tout son passé, elle

s’éleva contre sa mère, et oublia les palmes glorieuses de Lépante ?

Il Pordenone (c. 1484 – 1539). Saint Marc

Évangéliste, vers 1535, 72 x 74,5, Budapest

Dom

Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Aujourd’hui se

célébraient à Rome les Robigalia, remplacés plus tard par la procession

chrétienne qui se déroulait le long de la voie Flaminienne jusqu’au pont

Milvius et rejoignait ensuite Saint-Pierre. La fête de l’évangéliste Marc dut

donc attendre presque jusqu’au XIIe siècle avant d’être inscrite régulièrement

dans le Calendrier romain. Ce retard est d’autant plus surprenant que saint

Marc fut parmi les premiers hérauts qui, avec saint Pierre, annoncèrent à Rome

la bonne nouvelle ; en outre, il écrivit son Évangile dans la Ville éternelle,

à la demande des Romains eux-mêmes, et quand, un peu plus tard, Paul y subit

son premier emprisonnement, Marc lui prêta avec Luc une affectueuse assistance,

comme il l’avait déjà fait en faveur du Prince des Apôtres.

Cependant cet oubli, que

l’on pourrait taxer d’ingratitude, n’est pas isolé. Jean lui aussi a prêché à

Rome et y a trouvé le martyre dans la chaudière d’huile bouillante. Et

pourtant, on dirait presque que sa présence dans la Ville éternelle n’a laissé

aucune trace, comme cela arriva également pour Luc et pour d’autres insignes

personnages de l’âge apostolique. Cette anomalie s’explique pourtant aisément.

A l’origine, les commémorations liturgiques des saints avaient un caractère

local et funéraire, étant exclusivement célébrées près de leurs tombeaux

respectifs. Comme ni Jean, ni Luc, ni Marc, ni, à notre connaissance, d’autres

premiers compagnons des Apôtres ne finirent leurs jours à Rome, les diptyques

romains n’enregistrèrent pas leur déposition ou natalis. Les calendriers du

moyen âge à Rome dépendent principalement de ces listes, aussi s’explique-t-on

leur silence. Près du portique in Pallacinis, dans la première moitié du IVe

siècle, le pape Marc érigea une basilique qui, avec le temps, prit le nom de

l’évangéliste homonyme. D’autres églises également, au moyen âge, furent

dédiées à saint Marc, comme celles de calcarario, in macello, etc. Mais la

splendide basilique du pape Marc les surpassa toutes en célébrité tant par sa

beauté que par l’importance exceptionnelle qu’elle acquit dans l’histoire.

Aujourd’hui les Litanies

majeures se terminent par la messe stationnale à Saint-Pierre. La procession

litanique n’est donc aucunement en relation avec la fête de saint Marc, si bien

que, quand celle-ci est remise à un autre jour, on ne transfère point pour cela

les Litanies majeures. Il n’est fait d’exception que pour la fête de Pâques,

car si celle-ci tombait le 25 avril, la procession se célébrerait alors le

mardi suivant. Dans le bas moyen âge disparut de Rome tout souvenir des

Robigalia avec le parcours traditionnel du classique cortège de la jeunesse

romaine le long de la voie Flaminienne. La procession avait accoutumé de se

rendre du Latran à la basilique de Saint-Marc, et, de là, se dirigeait vers Saint-Pierre

; ce rite demeura en vigueur jusqu’à la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle.

Les antiennes et les

répons de la messe de saint Marc sont empruntés à la messe Protexisti, qui est

celle des Martyrs durant le temps pascal.

Néanmoins les collectes

et les lectures sont propres.

« O Dieu, qui avez élevé

le bienheureux Marc, votre évangéliste, à la grâce d’annoncer la Bonne

Nouvelle, faites que nous puissions profiter toujours de sa doctrine afin

d’être protégés par sa prière. Par notre Seigneur, etc. » : Souvent, dans la

sainte Écriture, la parole de Dieu est comparée à une source d’eau, qui apaise

les ardeurs de la soif, rafraîchit la terre aride, la féconde et fait reverdir

les plantes.

Dans le haut moyen âge,

les fontaines publiques revêtaient pour cette raison un certain caractère

religieux, en tant qu’elles symbolisaient le Verbe et la grâce divine. Nous en

avons pour preuve, entre autres témoignages, un puteal qui existe encore sous

le portique de la basilique de Saint-Marc de Pallacine, avec cette légende :

DE • BONIS • DEI • ET •

SANCTI • MARCI • IOHANNES • PRESBITER • FIERI • ROGABIT

OMNES • SITIENTES •

VENITE • AD • AQVAS • ET • SI • QVIS • DE • ISTA • AQVA • PRETIO

TVLERIT • ANATHEMA • SIT.

Qu’il est beau, dans

l’esprit du moyen âge, cet anathème lancé contre celui qui aurait trafiqué de

ce puteal par cela seul qu’il symbolisait l’eau de la grâce, qu’on n’eût pu

vendre pour de l’argent sans se rendre coupable de simonie.

Le texte d’Ézéchiel, lu

en ce jour (I, 10-14), décrit les symboles des quatre saints Évangiles qui,

dictés par un même Esprit, reflètent en un quadruple rayon la lumière et la

sagesse du Verbe éternel de Dieu. Quand l’œil humain, obscurci par le voile de

l’infidélité et des passions, veut lire la sainte Écriture, il l’estime sans

doute le livre le plus simple et le plus puéril qui se puisse imaginer. Au

contraire, quand avec une humble foi, l’œil pur et fort du croyant se fixe sur

ces pages sacrées, la vue demeure comme éblouie par cette lumière divine, et

l’intellect créé, pénétrant les secrets de la Sagesse incréée, sent la vanité

de tous les raisonnements humains. C’est à cet état de sublime ignorance que

fut élevé saint Paul—et, après lui, beaucoup d’autres saints — et dont il

déclare ne trouver dans le langage terrestre ni paroles ni concepts aptes à

exprimer ce qu’il y a vu.

L’Évangile est le récit

de la vocation et de la mission des soixante-douze disciples du Sauveur. Selon

toute probabilité, Marc ne fut pas de ce nombre ; mais appelé plus tard à la

suite du Seigneur, il accomplit lui aussi parfaitement les œuvres de

l’apostolat.

Des historiens récents

ont voulu voir dans les documents scripturaires quelque allusion au caractère

un peu timide de saint Marc. Quand, au soir de l’arrestation de Jésus, le jeune

Marc, éveillé en sursaut de son sommeil, sortit sur la route enveloppé simplement

dans son ample drap de toile, on l’arrêta, et lui, tout effrayé, se débarrassa

adroitement du drap et s’échappa nu des mains des soldats. Cet incident dut

toutefois l’impressionner et influer sur son caractère craintif ; il était fait

plutôt pour travailler docilement dans une position subordonnée que pour

assumer la responsabilité des initiatives hardies. Élevé au sein d’une famille

distinguée de Jérusalem, et ayant grandi au milieu des Apôtres, le jeune Marc

accompagna son cousin Barnabé et saint Paul dans leur première mission

apostolique en Pamphylie et finit par perdre courage à cause de la hardiesse

audacieuse des deux missionnaires juifs qui, en terre païenne, traitaient

librement avec les Gentils exécrés de la Thora, et leur donnaient part à l’héritage

des fils d’Abraham. En cette circonstance, Marc sentit que son heure n’avait

pas encore sonné pour ce service d’avant-garde, et, prenant congé des deux

missionnaires, il retourna au port tranquille de Jérusalem. Cependant il

portait le germe de la vocation à l’apostolat, et c’est pourquoi il ne se

sentit point en repos dans la paisible demeure du Cénacle. Quelque temps après

il voulut faire comme amende honorable de ce qu’il considérait comme une

faiblesse et il proposa aux deux apôtres de les accompagner dans leur seconde

mission. Mais cette fois, Paul, qui connaissait le caractère encore

insuffisamment mûri de Marc, craignit que sa présence fût plutôt un obstacle

qu’une aide pour la conversion des Grecs, et refusa de l’accepter ; c’est

pourquoi il partit avec son cousin dans la direction de Salamine.

Quand enfin, en 61-62,

Paul est prisonnier à Rome, nous retrouvons à ses côtés l’évangéliste Luc et

Marc, qui, après une courte absence en Asie Mineure et à Colosses, grâce à la

deuxième lettre adressée à Timothée, a été de nouveau appelé auprès de Paul,

comme une personne mihi utilis in ministerium [2]. On voit que le désaccord

momentané entre l’Apôtre, Barnabé et son cousin, n’avait laissé aucune trace

dans ces âmes grandes et généreuses. Durant le voyage de Paul en Espagne, Marc

demeura à Rome et servit d’interprète à Pierre, dont, à la demande des fidèles,

il mit ensuite par écrit les catéchèses.

Après le martyre des deux

Apôtres, une antique tradition rapporte que Marc alla à Alexandrie, où, au

commencement du IVe siècle, on voyait son sépulcre.

La préface est celle qui

est commune aux apôtres. Les manuscrits nous donnent toutefois le texte suivant

: ... per Christum Dominum nostrun. Cuius gratia beatum Marcum in sacerdotium

elegit, doctrina ad praedicandum erudit, potentia ad perseverandum confirmavit,

ut per sacerdotalem infulam pervenerit ad martyrii paltnam ; docensque

subditos, instruens vivendi exemplo, confirmans patiendo, ad Te coronandus

perveniret, qui persecutorum minas intrepidus superasset. Cuius interventus,

nos quaesumus, a nostris mundet delictis, qui tibi placuit tot donorum

praerogativis. Per quem, etc.

Quand Dieu appelle, il ne

faut pas reculer par crainte du péril et de la propre faiblesse. En ce cas, la

grâce recouvre les défauts de la nature, comme il advint pour saint Marc. Son

caractère était naturellement timide, et il eut un premier moment de défiance,

mais la grâce finit par prendre sur lui l’avantage, si bien qu’il devint l’«

interprète » de Pierre, l’Évangéliste glorieux, l’apôtre de l’Égypte et le

fondateur du trône des patriarches d’Alexandrie, héritiers chrétiens de la

puissance des anciens Pharaons.

Les vers du pape Grégoire

IV, sous la mosaïque absidale du titulus Marci in Pallacine ne sont pas sans

intérêt :

VASTA • THOLI • PRIMO •

SISTVNT • FVNDAMINE • FVLCRA

QVAE • SALOMONIACO •

FVLGENT • SVB • SIDERA • RITV

HAEC • TIBI • PROQVE •

TVO • PERFECIT • PRAESVL • HONORE

GREGORII • MARGE • EXIMIO

• CVM • NOMINE • QVARTVS

TV • QVOQVE • POSCE •

DEVM • VIVENDI - TEMPORA • LONGA

DONET • ET • AD • CAELI •

POST • FVNVS • SYDERA • DVCAT

La voûte de l’abside

s’élève sur un solide fondement ;

Comme le temple de

Salomon, elle resplendit, irradiée par le soleil.

En ton honneur, ô évêque

Marc, il éleva cette voûte

Celui qui, le quatrième,

porte l’illustre nom de Grégoire.

A ton tour, demande pour

lui à Dieu une longue vie

Et, après sa mort, le

royaume céleste.

Donc au IXe siècle, ce

temple continuait à être dédié, non à l’Évangéliste d’Alexandrie, mais au

MARCVS PRAESVL, c’est-à-dire au Pape qui avait fondé le Titre de Pallacines et

qui y était enseveli.

[2] II Timot., IV, 11.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/25-04-St-Marc-evangeliste

Apostel

Markus, Abbildung 21 aus dem Lorscher Evangeliar, auch als Codex

Aureus Laureshamensis bekannt, vermutlich in der Hofschule

Karls des Großen entstanden.

Mark

the Evangelist, image 21 of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch or Lorsch

Gospels, presumably written in the scriptorium of the Lorsch Abbey (Hofschule

Karls des Großen), Germany.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

L’Église a donné un rang

élevé à la fête de ce saint parce qu’il est l’auteur du second évangile. Saint

Marc nous a fait un présent dont nous devons lui être toujours reconnaissants.

— Jean Marc, appelé plus tard simplement Marc, l’auteur du second évangile,

était Juif de naissance. Sa mère s’appelait Marie (Act. Ap., XII, 12). Marie

était la propriétaire du Cénacle, la salle de la Cène, qui fut le lieu de

réunion de l’Église naissante de Jérusalem. Au moment de la mort du Seigneur,

Marc n’était encore qu’un jeune homme. Il semble que le jeune homme qui

assistait à l’arrestation de Jésus et qui échappa aux gardes en laissant son

manteau entre leurs mains (Marc XIV, 31) n’était autre que Marc. « Le peintre a

placé son monogramme dans un coin sombre du tableau ». Dans les années

suivantes, le jeune homme, qui devenait un homme, aura suivi, dans la maison de

sa mère ; la croissance de la jeune Église, il aura recueilli toutes les

traditions qu’il sut utiliser dans la rédaction de son évangile. Plus tard,

nous voyons Marc accompagner Barnabé qui était son cousin, ainsi que Paul, à

Antioche et, peu de temps après, dans le premier voyage de mission (Act. Ap.,

XI, 3 ; XII, 25 ; XII, 5). Mais il n’était pas de taille à supporter les

fatigues d’un tel voyage ; à Pergé, en Pamphilie, il quitta ses compagnons et

s’en revint. Quand les deux Apôtres entreprirent leur second voyage, Barnabé

voulut emmener son cousin. Paul s’y refusa et renonça à la compagnie de

Barnabé. Barnabé s’en alla avec Marc évangéliser Chypre. Plus tard, les

relations entre Paul et Marc devinrent plus intimes. Dans sa première captivité

romaine (61-63), Marc lui rendit de grands services (Col. IV, 10 ; Philem. 24),

et l’Apôtre se mit à l’apprécier. Dans sa seconde captivité, il le réclama (II

Tim., IV, II). Marc eut des relations particulièrement amicales avec saint

Pierre ; il fut son disciple, son compagnon, son interprète. D’après la

tradition unanime des Pères, il était présent à Rome pendant la prédication de

Pierre, et c’est sous l’influence du prince des Apôtres qu’il composa son

évangile. Aussi les passages où il est question de Pierre sont très développés

(par ex. le grand jour de Capharnaüm I, 14 sq.). Sur ce qui concerne la fin de

la vie de Marc, on a peu de renseignements. Il est certain qu’il fut évêque

d’Alexandrie, en Égypte, et y subit le martyre. Ses reliques furent transportées

d’Alexandrie à Venise où elles ont trouvé, dans la cathédrale de Saint-Marc, un

magnifique tombeau.

L’évangile de saint Marc

est, il est vrai, le plus court des quatre et est assez peu utilisé dans la

liturgie. Cependant il a aussi ses avantages. C’est avant tout l’évangile

romain. Il a été composé à Rome et est adressé à la chrétienté romaine ou, pour

mieux dire, à la chrétienté occidentale. Un autre avantage, c’est qu’il expose

la vie du Seigneur dans l’ordre chronologique et il est bien certain que nous

tenons à connaître les événements de la vie du Seigneur dans leur succession

historique. En outre, Marc est un miniaturiste. Souvent, d’un mot, d’une

addition, il donne à une scène déjà connue une nouvelle lumière. Cet évangile

est l’évangile de Pierre. Il est certain qu’il a été rédigé avec la

collaboration et sous la surveillance du prince des Apôtres. « L’évangéliste

Marc a comme symbole le lion parce qu’il commence par le désert : Voix de celui

qui crie dans le désert : Préparez les voies du Seigneur ; ou bien parce que le

Seigneur règne comme un Roi invincible » (c’est ce que l’évêque explique aux

catéchumènes le mercredi après le quatrième dimanche de Carême).

La messe (Protexisti.) —

La messe est composée de parties du commun des martyrs au temps pascal et de

parties du commun des évangélistes. A l’Introït, nous entendons le saint martyr

chanter son cantique d’action de grâces : « Dieu m’a protégé dans le martyre ».

Le psaume 63 chante sa victoire sur ses ennemis. La leçon et l’Évangile sont choisis

en considération de l’évangéliste et du disciple. Ézéchiel voit les quatre

Chérubins sous quatre aspects différents. Cette quadruple forme est interprétée

par les saints Pères comme le symbole des quatre évangélistes ; Marc a le

symbole du lion. L’Évangile raconte l’envoi des 72 disciples. Le Seigneur

recommande à tous ses disciples — et nous le sommes, nous aussi — de

restreindre leurs besoins et d’avoir le zèle des âmes.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/25-04-St-Marc-evangeliste

Dom

Pius Parsch, le Guide dans l’année liturgique

[1] Suite de l’Homélie :

A chacun d’eux appartiennent donc les quatre faces. Voulez-vous, en effet,

savoir ce que pense saint Matthieu du mystère de l’Incarnation du Verbe ? Il a

sur ce point la même doctrine que saint Marc, saint Luc et saint Jean. Voulez-vous

savoir ce qu’en pense saint Jean ? Il n’a pas d’autre sentiment à cet égard que

saint Luc, saint Marc et saint Matthieu. Cherchez-vous ce qu’en pense saint

Marc ? C’est aussi ce qu’en pensent saint Matthieu, saint Jean et saint Luc.

Voulez-vous enfin connaître sur cette question le sentiment de saint Luc ?

C’est le même encore que celui de saint Jean, de saint Matthieu et de saint

Marc. Les quatre faces appartiennent donc bien réellement a chacun d’eux, car

la notion de la foi par laquelle Dieu les connaît est, dans chacun pris

isolément, la même que dans les quatre réunis. Ce que vous trouvez dans l’un

d’eux, vous le voyez également dans tous les quatre. « Et chacun d’eux avait

quatre ailes. » Tous, d’un commun accord, annoncent le Fils de Dieu tout-puissant,

Jésus-Christ notre Seigneur, et tenant les yeux de l’âme levés vers sa

divinité, ils volent sur les ailes de la contemplation. Les faces des quatre

Évangélistes ont donc rapport à la sainte humanité du Sauveur, et leurs ailes à

sa divinité. Quand ils le considèrent revêtu d’un corps, ils tournent en

quelque sorte leurs faces vers lui, et quand ils proclament qu’il est, en tant

que Dieu, l’Être infini et incorporel, ils s’élèvent, pour ainsi dire dans les

airs, sur les ailes de la contemplation. Comme ils ont tous une même foi en son

Incarnation, et que les uns et les autres ont aussi le privilège de contempler

sa divinité, il est juste de dire : « Chacun d’eux avait quatre faces, et

chacun d’eux quatre ailes. »

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/25-04-St-Marc-evangeliste

Vrcholek

střechy baziliky svatého Marka v Benátkách.

Patron Benátek svatý Marek je zde obklopen anděly a níže je

okřídlený drak, maskot Benátek

Detail

of the rooftop of San Marco cathedral in Venice, Italy. Venice patron Saint,

St. Mark with angels. Underneath is winged lion, mascot of Venice.

Détail

du toit de la basilique Saint-Marc à Venise en

Italie. On peut voir sur cette photo Saint Marc, patron de Venise, et un lion

ailé, emblème de la ville.

Detajl

sa krova crkve Svetog Marka u Veneciji, Italija. Sv. Marko je zavetnik

Venecije, a krilati lav maskota grada.

SAINT MARC, ÉVANGÉLISTE*

Marc veut dire sublime en commandement, certain, abaissé et amer. Il fut sublime en commandement par la perfection de sa vie, car non seulement, il observa les commandements qui sont communs à tous, mais encore ceux qui sont sublimes, tels que les conseils. Il fut certain en raison de la certitude de la doctrine dans son évangile, parce que cette certitude a pour garant saint Pierre, son maître, de qui il l’avait appris. Il fut abaissé, en raison de sa profonde humilité, qui lui fit, dit-on, se couper le pouce, afin de ne pas être trouvé capable d'être prêtre. Il fut amer en raison de l’amertume du tourment qu'il endura lorsqu'il fut traîné par la ville, et, qu'il rendit l’esprit au milieu des supplices. Ou bien Marc vient de Marco, qui est une masse, dont le même coup aplatit le fer, produit la mélodie, et affermit l’enclume. De même saint Marc, par l’unique doctrine de son évangile, dompte la perfidie des hérétiques, dilate la louange divine et affermit l’Eglise.

Marc, évangéliste, prêtre de la tribu de Lévi, fut, par le baptême, le fils de saint Pierre, apôtre, dont, il était le disciple en la parole divine. Il alla à Rome avec ce saint. Comme celui-ci v prêchait la bonne nouvelle, les fidèles de Rome prièrent saint Marc de vouloir écrire l’Evangile, pour l’avoir toujours présent à la mémoire. Il le leur écrivit loyalement, tel qu'il l’avait appris de la bouché de son maître saint Pierre, qui l’examina avec soin, et après avoir vu qu'il était plein de vérité, il l’approuva et le jugea digne d'être reçu par tous les fidèles (Saint Jérôme, Vir. illustr., c. VIII; — Clément d'Alexandrie, dans Eusèbe, l. II, c. XV). Saint Pierre, considérant que Marc était constant dans la foi, le destina pour Aquilée, où après avoir prêché la parole de Dieu, il convertit des multitudes innombrables de gentils à J.-C. On dit que là aussi, il écrivit son évangile que l’on montre encore à présent dans l’église d'Aquilée, où on le garde avec grand respect. Enfin saint Marc conduisit à Rome, auprès de saint Pierre, nu citoyen d'Aquilée, nommé Ermagoras, qu'il avait converti à la foi afin que l’apôtre le consacrât évêque d'Aquilée. Ermagoras, après avoir reçu la charge du pontificat, gouverna avec zèle cette église : il fut pris ensuite par les infidèles et reçut la couronne du martyre. Pour saint Marc, il fut envoyé par saint Pierre à Alexandrie, où il prêcha le premier la parole de Dieu (Eusèbe, c. XVI ; Epiphan., LI, c. VI; saint Jér., ibid.). A son entrée dans cette ville, au rapport de Philon, juif très disert, il se forma une assemblée immense qui reçut la foi et pratiqua la dévotion et la continence. Papias, évêque de Jérusalem, fait de lui le plus grand éloge en très beau langage ; et voici ce que Pierre Damien dit à son sujet : « Il jouit d'une si grande influence à Alexandrie, que tous ceux qui venaient en foule pour être instruits dans la foi, atteignirent bientôt au sommet de la perfection, par la pratique de la continence; et de toutes sortes de bonnes oeuvres, en sorte que l’on eût dit une communauté de moines. On devait ce résultat moins aux miracles extraordinaires de saint Marc et à l’éloquence de ses prédications, qu'à ses exemples éminents. » Le même Pierre Damien ajoute qu'après sa mort, son corps fut ramené en Italie, afin que la terre où il lui avait été donné d'écrire son Evangile, eût l’honneur de posséder ses dépouilles sacrées. « Tu es heureuse, ô Alexandrie, d'avoir été arrosée de son sang glorieux, comme toi, en Italie, tu ne l’es pas moins de posséder un si rare trésor. »

On rapporte que saint Marc fut doué d'une si grande Humilité qu'il se coupa le pouce afin que l’on ne songeât pas à l’ordonner prêtre (Isidore de Sév., Vies et morts illustres, ch. LIV). Mais par une disposition de Dieu et par l’autorité de saint Pierre, il fut choisi pour évêque d'Alexandrie: A son entrée dans cette ville, sa chaussure se rompit et se déchira subitement; il comprit intérieurement ce que cela signifiait, et dit : « Vraiment, le Seigneur a raccourci mon chemin, et Satan ne sera pas un obstacle pour moi, puisque le Seigneur m’a absous des oeuvres de mort. » Or, Marc voyant un savetier qui cousait de vieilles chaussures, lui donna la sienne à raccommoder : mais en le faisant, l’ouvrier se blessa grièvement à la main gauche, et se mit à crier : « Unique Dieu. » En l’entendant, l’homme de Dieu dit : « Vraiment le Seigneur a rendu mon voyage heureux. » Alors il fit de la boue avec sa salive et de la terre, l’appliqua sur la main du savetier qui fut incontinent guéri. Cet homme, voyant le pouvoir extraordinaire de Marc, le fit entrer chez lui et lui demanda qui il était, et d'où il venait. Marc lui avoua être le serviteur du Seigneur Jésus.

L'autre lui dit : « Je voudrais bien le voir. » Je te le montrerai, lui répondit saint Marc. » Il se mit alors à lui annoncer l’Evangile de J.-C. et le baptisa avec tous ceux de sa maison. Les habitants de la ville ayant appris l’arrivée d'un Galiléen, qui méprisait les sacrifices de leurs dieux, lui tendirent des pièges. Saint Marc, en ayant été instruit, ordonna évêque Anianus, cet homme-là même qu'il avait guéri (Actes de saint Marc), et partit pour la Pentapole, où il resta deux ans, après lesquels il revint à Alexandrie. Il y avait fait élever une église sur les rochers qui bordent la mer, dans un lieu appelé Bucculi (Probablement: l’abattoir) ; il y trouva le nombre des chrétiens augmenté. Or, les prêtres des temples cherchèrent à le prendre; et le jour de Pâques, comme saint Marc célébrait la- messe, ils s'assemblèrent tous au lieu où était le saint, lui attachèrent une corde au cou et le traînèrent par toute la ville en disant : « Traînons le buffle au Bucculi (A l’abattoir). » Sa chair et son sang étaient épars sur la terre et couvraient les pierres, ensuite il fut, enfermé dans une prison où un ange le fortifia. Le Seigneur J.-C. lui-même daigna le visiter et lui dit pour, le conforter : « La paix soit avec toi, Marc, mon évangéliste; ne crains rien car je suis avec toi pour te délivrer. » Le matin arrivé, ils lui jettent encore une fois une corde au cou, et le traînent çà et là en criant : « Traînez le buffle au Bucculi. » Au milieu de ce supplice, Marc rendait grâces à Dieu en disant : « Je remets mon esprit entre vos mains. » Et en prononçant ces mots, il expira. C'était sous Néron, vers l’an 57. Comme les païens le voulaient brûler, soudain, l’air se trouble, une grêle s'annonce, les tonnerres grondent, les éclairs brillent, tout le monde s'empressa de fuir, et le corps du saint reste intact. Les chrétiens le prirent et l’ensevelirent dans l’église en toute révérence. Voici le portrait de saint Marc (Un ms. de la Bibliothèque de Saint-Victor, coté 28 et cité par Ducange donne en ces termes le portrait du saint : « La forme de saint Marc fu tele, lonc nés, sourciz yautis, biaus par iex, les cheveux cercelés, longe barbe, de très bele composition de cors, de moien eaige » Gloss. ° Eagium) : Il avait le nez long, les sourcils abaissés, les yeux beaux, le front un, peu chauve, la barbe épaisse. Il était de belles manières, d'un âge moyen ; ses cheveux commençaient à blanchir, il était affectueux, plein de mesure et rempli de la grâce de Dieu. Saint Ambroise dit de lui : « Comme le bienheureux Marc brillait par des miracles sans nombre, il arriva qu'un cordonnier auquel il avait donné sa chaussure à raccommoder, se perça la main gauche dans son travail, et en se faisant la blessure, il cria: « Un Dieu! » Le serviteur de Dieu fut tout joyeux de l’entendre : il prit de la boue qu'il fit avec sa salive, en oignit la main de l’ouvrier qu'il guérit à l’instant et avec laquelle cet homme put continuer son travail. Comme le Sauveur il guérit aussi un aveugle-né. »

L'an de l’Incarnation du Seigneur 468, du temps de l’empereur Léon, des Vénitiens transportèrent le corps de saint Marc, d'Alexandrie à Venise, où fut élevée, en l’honneur du saint, une église d'une merveilleuse beauté. Des marchands vénitiens, étant allés à Alexandrie; firent tant par dons et par promesses auprès de deux prêtres, gardiens du corps de saint Marc, que ceux-ci le laissèrent enlever en cachette et emporter à Venise. Mais comme on levait le corps du tombeau, une odeur si pénétrante se répandit dans Alexandrie que tout le,monde s'émerveillait d'où pouvait venir une pareille suavité. Or; comme les marchands étaient en pleine mer, ils découvrirent aux navires qui allaient de conserve avec eux qu'ils portaient le corps de saint Marc; un des gens dit : « C'est probablement le corps de quelque Egyptien que l’on vous a donné, et vous pensez emporter le corps de saint Marc. » Aussitôt le navire qui portait le corps de saint Marc vira de bord avec une merveilleuse célérité et se heurtant contre le navire où se trouvait celui qui venait de parler, il en brisa un côté. Il ne s'éloigna point avant que tous ceux qui le montaient n'eussent acclamé qu'ils croyaient que le corps de saint Marc s'y trouvât.

Une nuit, les navires étaient emportés par un courant très rapide, et les nautoniers; ballottés par la tempête et enveloppés de ténèbres, ne savaient où ils allaient; saint Marc apparut au moine gardien de son corps, et lui dit : « Dis à tout ce monde de carguer vite les voiles, car ils ne sont pas loin de la terre. » Et on les cargua. Quand le matin fut venu, on se trouvait vis-à-vis une île. Or, comme on longeait divers rivages, et qu'on cachait à tous le saint trésor, des habitants vinrent et crièrent : « Oh! que vous êtes heureux, vous qui portez le corps de saint Marc ! Permettez que nous lui rendions nos profonds hommages.» Un matelot encore tout à fait incrédule est saisi par le démon et vexé jusqu'au moment où, amené auprès du corps, il avoua qu'il croyait que c'était celui de saint Marc. Après avoir été délivré, il rendit gloire à Dieu et eut par la suite une grande dévotion au saint. Il arriva que, pour conserver avec plus de précaution le corps de saint Marc, on le déposa au bas d'une colonne de marbre, en présence d'un petit nombre de personnes; mais par le cours du temps, les témoins étant morts, personne ne pouvait savoir, ni reconnaître, à aucun indice, l’endroit où était le saint trésor. Il y eut des pleurs dans le clergé, une grande désolation chez les laïcs, et un chagrin profond dans tous. La peur de ce peuple dévot était en effet qu'un patron si recommandable n'eût été enlevé furtivement. Alors on indique un jeûne solennel, on ordonne une procession plus solennelle. encore ; mais voici que, sous les veux et à la surprise de tout le monde, les pierres se détachent de la colonne et laissent voir à découvert la châsse où le corps était caché. A l’instant on rend des actions de grâces au Créateur quia daigné révéler le saint patron ; et ce jour, illustré par la gloire d'un si grand prodige, fut fêté dans la suite des temps (Au 23 juin).

Un jeune homme, tourmenté par un cancer dont les vers lui rongeaient la poitrine, se mit à implorer d'un coeur dévoué les suffrages de saint Marc; et voici que, dans son sommeil, un homme en habit de pèlerin lui apparut se hâtant dans sa marche. Interrogé par lui qui il était et où il allait en marchant si vite, il lui répondit qu'il était saint Marc, qu'il courait porter secours à un navire en péril qui l’invoquait. Alors il étendit la main, en toucha le malade qui, à son réveille matin, se sentit complètement guéri. Un instant après le navire entra dans le port de Venise et ceux qui le montaient racontèrent le péril dans lequel ils s'étaient trouvés et comme saint Marc leur était venu en aide. On rendit grâces pour ces deux miracles et Dieu fut proclamé admirable dans Marc, son saint.

Des marchands de Venise qui allaient à Alexandrie sur un vaisseau sarrasin, se voyant dans un péril imminent, se jettent dans une chaloupe, coupent la corde, et aussitôt le navire est englouti dans les flots qui enveloppent tous les Sarrasins. L'un d'eux invoqua saint Marc et fit comme il put, voeu de recevoir le baptême et de visiter son église, s'il lui prêtait secours. A l’instant, un personnage éclatant lui apparut, l’arracha des flots et le mit avec les autres ans la chaloupe. Arrivé à Alexandrie, il fut ingrat envers son libérateur et ne se pressa ni d'aller à l’église de saint Marc, ni de recevoir les sacrements de notre foi. De rechef saint Marc lui apparut et lui reprocha son ingratitude. Il rentra donc en lui-même, vint à Venise, et régénéré dans les fonts sacrés du baptême, il reçut le nom de Marc. Sa foi en J.-C. fut parfaite et il finit sa vie dans les bonnes oeuvres. — Un homme qui travaillait au haut du campanile de saint Marc de Venise, tombe tout à coup à l’improviste; ses membres sont déchirés par lambeaux; mais, dans sa chute, il se rappelle saint Marc, et implore son patronage alors il rencontre une poutre qui le retient. On lui donne une corde et il s'en relève sans blessure; il remonte ensuite à son travail avec dévotion pour le terminer. — Un esclave au service d'un noble habitant de la Provence, avait fait voeu de visiter le corps de saint Marc; mais il n'en pouvait obtenir la permission : enfin il tint moins de compte de la peur, de son maître temporel que de son maître céleste. Sans prendre congé, il partit avec dévotion pour accomplir son voeu. A son retour, le maître, qui était fâché, ordonna de lui arracher les yeux. Cet homme cruel fut favorisé dans son dessein par des hommes plus cruels encore qui jettent, par terre, le serviteur de Dieu, lequel invoquait saint Marc, et s'approchent avec des poinçons pour lui crever les yeux : les efforts qu'ils tentent sont inutiles, car le fer se rebroussait et se cassait tout d'un coup. Il ordonne donc que ses jambes soient rompues et ses pieds coupés à coups de haches, mais le fer qui est dur de sa nature s'amollit comme le plomb. Il ordonne qu'on lui brise la figuré et les dents avec des maillets de fer; le fer perd sa force et s'émousse par la puissance de Dieu. A cette vue son maître stupéfait demanda pardon et alla avec son esclave visiter en grande dévotion le tombeau de saint Marc. — Un soldat reçut au bras dans une bataille une blessure telle que sa main restait pendante. Les médecins et ses amis lui conseillaient de la faire amputer; mais ce soldat qui était preux, honteux d'être manchot, se fit remettre la main à sa place et l’assujettit avec des bandeaux sans aucun médicament. Il invoqua les suffrages de saint Marc et sa main fut guérie aussitôt : il n'y resta qu'une cicatrice qui fut un témoignage d'un si grand miracle et un monument d'un pareil bienfait. — Un homme de la ville de Mantoue, faussement accusé par des envieux, fut mis en une prison, où, après être resté 40 jours dans le plus grand ennui, il se mortifia par un jeûne de trois jours en invoquant le patronage de saint Marc. Ce saint lui apparaît et lui commande de sortir avec confiance de sa prison. Cet homme, que l’ennui avait endormi, ne se mit pas en peine d'obéir aux ordres du saint, tout en se croyant le jouet d'une illusion. Il eut une seconde et une troisième apparition du saint qui lui renouvela les mêmes ordres. Revenu à soi, et voyant la porte ouverte, il sortit avec confiance de la prison et brisa ses entraves comme si c'eût été des liens d'étoupes. Il marchait donc en plein jour au milieu des gardes et des autres personnes présentes, sans être vu, tandis que lui voyait tout le monde. Il vint au tombeau de saint Marc pour s'acquitter dévotement de sa dette de remerciements.

L'Apulie entière était en proie à la stérilité, et pas une goutte de pluie n'arrosait cette terre. Alors il fut révélé que c'était un châtiment de ce qu'on ne célébrait pas la fête de saint Marc. Donc on invoqua ce saint et on promit de fêter avec solennité le jour de sa fête. Le saint fit cesser la stérilité et renaître l’abondance en donnant un air pur et une pluie convenable. — Environ l’an 1212, il y avait à Pavie, dans le, couvent des Frères Prêcheurs, un frère de sainte et religieuse vie, nommé Julien, originaire de Faënza, jeune de corps, mais vieux d'esprit; dans sa dernière maladie il s'inquiéta de sa position auprès du prieur, qui lui répondit que sa mort était prochaine. Aussitôt la figure du malade devint resplendissante de, joie et il se mit à crier en applaudissant des mains et de tousses membres : « Faites place, mes frères, car ce sera dans un excès d'allégresse que mon âme va sortir de mon corps, depuis que j'ai entendu d'agréables nouvelles. » Et en élevant les mains- au ciel, il se mit à dire : « Educ de custodia animam meam, etc. Seigneur, tirez mon âme de sa prison. Malheureux homme que je suis! qui me délivrera de ce corps de mort? » Il s'endormit alors d'un léger sommeil, et vit venir à lui saint Marc qui se plaça à côté de son lit : et une voix qui s'adressait au saint, lui dit : « Que faites-vous, ici, ô Marc? » Celui-ci répondit : « Je suis venu trouver ce mourant, parce que son ministère a été agréable à Dieu. » La voix se fit encore entendre : « Comment se fait-il que de tous les saints, ce soit vous de préférence qui soyez venu à lui? » «C'est, répondit-il, parce qu'il a eu pour moi une dévotion spéciale et qu'il a visité avec une dévotion toute particulière le lieu où repose mon corps. C'est donc pour cela que je suis venu le visiter à l’heure de sa mort. » Et voici que des hommes couverts d'aubes blanches remplirent toute la maison. Saint Marc leur dit : « Que venez-vous faire ici ? » « Nous venons, répondirent-ils, pour présenter l’âme de ce religieux devant le Seigneur. » A son réveil, ce frère envoya chercher aussitôt le prieur qui m’a lui-même raconté ces faits, et lui rendant compte de tout ce qu'il avait vu, il s'endormit heureusement et en grande joie dans le Seigneur **.

* Ordéric Vital raconte (Hist. Eccl., part. I, liv. II, c. XX) chacun des faits consignés dans la légende de saint Marc.

** La traduction française de M. Jehan Batallier intercale ici un miracle que le texte latin ne fournit pas, et que nous copions :

« Si côe ung autre

chevalier chevauchoist tout arme dessus un pont, le cheval cheut sur le pont,

et le chevalier cheut, ou parfont de leaue en bas. Et si côme il vit qu'il

nistroit iamais de la par force ppre, il reclama le benoit Marc : et le sainct

luy tendit une lance et le mist hors de leaue et doncqs il vît a Venise et

racôta le miracle et acôplit son voeu devotemêt. »

La Légende dorée de

Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction,

notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine

honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de

Seine, 76, Paris mdcccci

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome01/061.htm

Gioacchino Assereto (1600–1649). Saint

Marc Évangéliste, vers 1640,

95 x 71, Toulouse, Musée des Augustins

Qui était Marc ?

L’Évangile ne fournit

aucune indication directe sur son identité. C’est pourquoi certains

spécialistes renoncent à toute tentative d’identification. Selon la tradition,

il s’agit de « Jean surnommé Marc » connu par les Actes des Apôtres. Marc n’a

pas connu Jésus mais fait partie des premiers convertis au christianisme. Il

est emmené par Paul et Barnabé lors du premier voyage missionnaire. Plus tard,

Marc fut auprès de l’Apôtre Paul. On sait, selon la tradition, qu’il a

également été l’interprète de Pierre. « Il a dû rejoindre Pierre à Rome »,

raconte Frère Claude Coulot, exégète et professeur émérite à la faculté de

théologie catholique de l’université de Strasbourg.

Le franciscain s’appuie

sur le livre L’Explication des paroles du Seigneur de Papias d’Hiérapolis : «

Marc qui était l’interprète de Pierre a écrit avec exactitude tout ce dont il

se souvenait de ce qui avait été dit ou fait par le Seigneur. Car il n’avait

pas entendu, ni accompagné le Seigneur mais plus tard, il a accompagné Pierre.

Celui-ci donnait ses informations sans faire une synthèse des paroles du

Seigneur. De la sorte, Marc n’a pas commis d’erreur en écrivant comme il se

souvenait. Mais il n’a eu en effet qu’un seul dessein, celui de ne rien laisser

de côté de ce qu’il avait entendu et de ne tromper en rien en ce qu’il

rapportait. » Selon la tradition, Marc serait mort martyr en 68 mais on ne

connaît pas sa date de naissance. L’animal qui le symbolise est le lion ailé

qui représente le courage et l’élévation.

Quand a-t-il écrit

l’Évangile ?

L’Évangile selon Saint

Marc est, de l’avis des experts, le premier en date. Il aurait été écrit vers

65. Claude Coulot soutient la théorie des deux sources « qui veut que Marc soit

une des sources des évangiles de Matthieu et de Luc écrites entre dix et quinze

ans plus tard ». La tradition donne Rome comme lieu de composition de

l’écriture. Marc y aurait séjourné auprès de Paul et de Pierre. « L’étude du

texte qui mentionne des circonstances de la vie, traduction de paroles

araméennes, emploi de mots latins, usage de monnaies romaines, explication de

coutumes juives, permet de justifier une telle hypothèse », indique Claude

Coulot.

Comment se démarque-t-il

des autres Évangiles ?

La place accordée aux

disciples est l’une des particularités de l’Évangile selon saint Marc. « Marc

est l’évangéliste qui présente le plus souvent dans ses récits les disciples

aux côtés de Jésus, confirme Frère Claude Coulot. Il y a toute une réflexion

sur la condition de disciple dans l’Évangile de Marc, le fait de s’engager à la

suite de Jésus. » Mais il soulève un paradoxe : « Les disciples manifestent