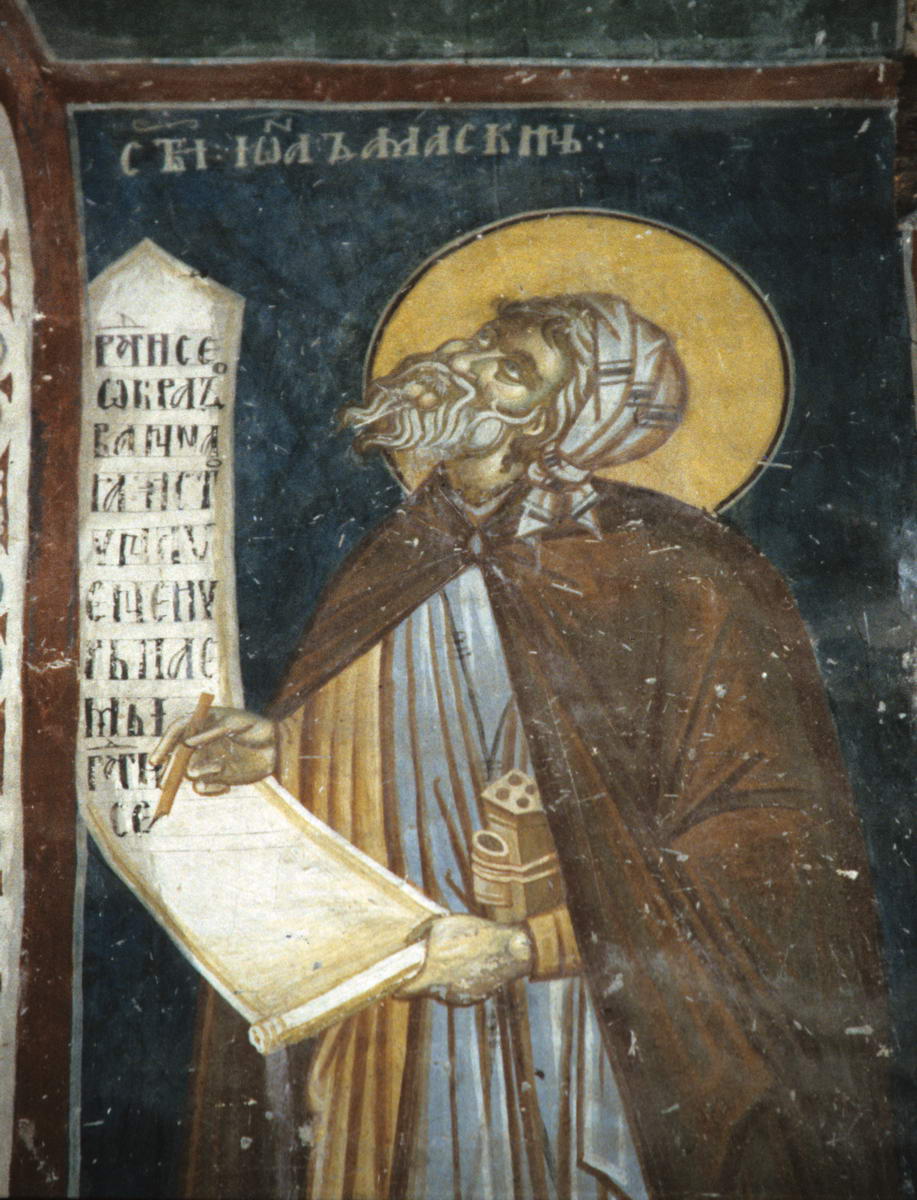

John de Damascus - http://www.orthodox.net/ikons/john-of-damascus-01.jpg 295

x 400 pixels - 17k. This image is provided courtesy of St Nicholas Russian

Orthodox Church, Dallas Texas

Saint Jean Damascène

Jean de Damas, Docteur de l'Église (+ 749)

Jean Mansour est né à Damas en Syrie, dans une famille de fonctionnaires des

impôts, arabe et chrétienne. Son grand-père et son père ont servi

successivement sous les Perses, les Byzantins et les Arabes. Mansour, à son

tour, supervise durant des années la perception des impôts que les chrétiens

doivent à l'émir de Damas. Vers 720, le nouveau calife décide d'islamiser son

administration et en chasse les chrétiens. Mansour a 45 ans et il est désormais

sans travail. Cette liberté lui permet de se rendre en Palestine où il entre au

monastère de Mar Saba (saint Sabas) entre Jérusalem et Bethléem. Devenu prêtre,

il prend le nom de Jean et partage désormais sa vie entre la prédication à

Jérusalem où le patriarche l'a choisi comme conseiller théologique et l'étude

dans son monastère. Son principal écrit "La source de la

connaissance" résume toute la théologie byzantine. Il est aussi un grand

défenseur des Saintes Images lors de la première crise iconoclaste. On lui doit

de nombreux tropaires, des hymnes et des poèmes. C'est lui composa le canon que

la liturgie chante à Pâques et il rédigea la plupart des hymnes de l'Octoèque

(hymnes pour les dimanches selon les huit tons musicaux) en l'honneur de la

résurrection du Seigneur. Le Pape Léon XIII l'a proclamé docteur de l'Église en

1890.

A l'audience générale du 6 mai 2009, Benoît XVI a tracé le portrait de saint

Jean Damascène (675 - 749), qui occupe une place importante dans la théologie

byzantine: "Il fut avant tout témoin de l'effondrement de la culture

chrétienne gréco-syrienne, qui dominait la partie orientale de l'empire, devant

la nouveauté musulmane qui se répandait avec les conquêtes militaires de

l'actuel proche et moyen orient. Né dans une riche famille chrétienne, il

devint jeune responsable des finances du califat. Vite insatisfait de la vie de

cour, il choisit la voie du monachisme et entra vers 700 au couvent de St. Saba

proche de Jérusalem, sans jamais plus s'en éloigner. Il se consacra alors

totalement à l'ascèse et à l'étude, sans dédaigner l'activité pastorale dont

témoignent ses nombreuses homélies... Léon XIII le proclama Docteur de l'Église

en 1890".

Puis le Pape a rappelé que Jean Damascène est surtout resté fameux pour ses

trois discours contre les iconoclastes, condamnés après sa mort au concile de

Hieria (754). Il y développe les premiers arguments en défense de la vénération

des icônes exprimant de mystère de l'Incarnation. "Ainsi fut-il l'un des

premiers à distinguer entre cultes public et privé, entre adoration et

vénération, la première étant réservée à Dieu seul. La seconde forme peut

servir à s'adresser au saint représenté. "Cette distinction fut très

importante pour répondre chrétiennement à qui prétendait universelle et

définitive l'interdiction mosaïque des images dans le culte. Ayant débattu de

la question, les chrétiens de l'époque ont alors trouvé une justification de la

vénération des images... Mais le débat était de grande actualité dans le monde

musulman, qui fit sienne l'interdiction hébraïque des images". Témoin du

culte des icônes, Jean Damascène en fit une caractéristique de la théologie et

de la spiritualité orientale. Jusqu'à nos jours, son enseignement porte la

tradition de l'Église universelle, dont la doctrine sacramentale prévoit que

des éléments matériels, repris de la nature, peuvent être source de grâces par

le biais de l'invocation de l'Esprit, doublée de la confession de la vraie

foi". Il admit aussi la vénération des reliques des saints car,

participant à la Résurrection, on ne peut les considérer comme de simples

morts. "L'optimisme chrétien de saint Jean Damascène -a conclu le

Saint-Père- dans la contemplation de la nature, dans la capacité à voir le bon,

le beau et le véritable dans la création, n'a rien d'ingénu. Il tient compte de

la blessure infligée à la nature humaine par la liberté voulue de Dieu et

souvent mal utilisée par l'homme, ce qui entraîne une disharmonie diffuse du

monde et tout ce qui en découle. D'où l'exigence du théologien de Damas de

clairement percevoir la nature, en tant que reflet de la bonté et de la beauté

de Dieu, blessées par la faute de l'homme, mais renforcées et renouvelées par

l'incarnation du Fils". (source: VIS 090506)

Mémoire de saint Jean Damascène, prêtre et docteur de l’Église, célèbre par sa

sainteté et sa doctrine. Pour le culte des saintes images, il combattit avec

vigueur par sa parole et ses écrits contre l’empereur Léon l’Isaurien et,

devenu moine et prêtre dans la laure de Saint-Sabas près de Jérusalem, il

composa des hymnes sacrées et y mourut, vers 749.

Martyrologe romain

A propos des icônes: Ce n’est pas la matière que j’adore mais le créateur

de la matière qui, à cause de moi, s’est fait matière, a choisi sa demeure dans

la matière. Par la matière, il a établi mon salut. En effet, le Verbe s’est

fait chair et il a dressé sa tente parmi nous… Cette matière, je l’honore comme

prégnante de l’énergie et de la grâce de Dieu.

Saint Jean Damascène-Discours sur les images

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saints_215.html

The

dream of Saint John Damascene : the Virgin attaches his severed right hand.

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais parler aujourd'hui de Jean Damascène, un personnage de premier plan

dans l'histoire de la théologie byzantine, un grand docteur dans l'histoire de

l'Église universelle. Il représente surtout un témoin oculaire du passage de la

culture chrétienne grecque et syriaque, commune à la partie orientale de

l'Empire byzantin, à la culture de l'islam, qui s'est imposée grâce à ses

conquêtes militaires sur le territoire reconnu habituellement comme le Moyen ou

le Proche Orient. Jean, né dans une riche famille chrétienne, assuma encore

jeune la charge - remplie déjà sans doute par son père - de responsable

économique du califat. Mais très vite, insatisfait de la vie de la cour, il

choisit la vie monastique, en entrant dans le monastère de Saint-Saba, près de

Jérusalem. C'était aux environs de l'an 700. Ne s'éloignant jamais du

monastère, il consacra toutes ses forces à l'ascèse et à l'activité littéraire,

ne dédaignant pas une certaine activité pastorale, dont témoignent avant tout

ses nombreuses Homélies. Sa mémoire liturgique est célébrée le 4 décembre. Le

Pape Léon XIII le proclama docteur de l'Eglise universelle en 1890.

En Orient, on se souvient surtout de ses trois Discours pour légitimer la

vénération des images sacrées, qui furent condamnés, après sa mort, par le

Concile iconoclaste de Hiéria (754). Mais ces discours furent également le

motif fondamental de sa réhabilitation et de sa canonisation de la part des Pères

orthodoxes convoqués par le second Concile de Nicée (787), septième Concile

œcuménique. Dans ces textes, il est possible de retrouver les premières

tentatives théologiques importantes de légitimer la vénération des images

sacrées, en les reliant au mystère de l'Incarnation du Fils de Dieu dans le

sein de la Vierge Marie.

Jean Damascène fut, en outre, parmi les premiers à distinguer, dans le culte

public et privé des chrétiens, l'adoration (latreia) de la vénération

(proskynesis): la première ne peut être adressée qu'à Dieu, suprêmement

spirituel, la deuxième au contraire peut utiliser une image pour s'adresser à

celui qui est représenté dans l'image même. Bien sûr, le saint ne peut en aucun

cas être identifié avec la matière qui compose l'icône. Cette distinction se

révéla immédiatement très importante pour répondre de façon chrétienne à ceux

qui prétendaient universel et éternel l'observance de l'interdit sévère de

l'Ancien Testament d'utiliser des images dans le culte. Tel était le grand

débat également dans le monde islamique, qui accepte cette tradition juive de

l'exclusion totale d'images dans le culte. Les chrétiens, en revanche, dans ce

contexte, ont débattu du problème et trouvé la justification pour la vénération

des images. Damascène écrit: "En d'autres temps, Dieu n'avait jamais été

représenté en image, étant sans corps et sans visage. Mais à présent que Dieu a

été vu dans sa chair et a vécu parmi les hommes, je représente ce qui est

visible en Dieu. Je ne vénère pas la matière, mais le créateur de la matière,

qui s'est fait matière pour moi et a daigné habiter dans la matière et opérer

mon salut à travers la matière. Je ne cesserai donc pas de vénérer la matière à

travers laquelle m'a été assuré le salut. Mais je ne la vénère absolument pas

comme Dieu! Comment pourrait être Dieu ce qui a reçu l'existence à partir du

non-être?... Mais je vénère et respecte également tout le reste de la matière

qui m'a procuré le salut, car pleine d'énergie et de grâces saintes. Le bois de

la croix trois fois bénie n'est-il pas matière? L'encre et le très saint livre

des Evangiles ne sont-ils pas matière? L'autel salvifique qui nous donne le

pain de vie n'est-il pas matière?.... Et, avant tout autre chose, la chair et

le sang de mon Seigneur ne sont-ils pas matière? Ou bien tu dois supprimer le

caractère sacré de toutes ces choses, ou bien tu dois accorder à la tradition

de l'Eglise la vénération des images de Dieu et celle des amis de Dieu qui sont

sanctifiés par le nom qu'ils portent, et qui, pour cette raison, sont habités

par la grâce de l'Esprit Saint. N'offense donc pas la matière: celle-ci n'est

pas méprisable; car rien de ce que Dieu a fait n'est méprisable" (Contra

imaginum calumniatores, I, 16, ed; Kotter, pp. 89-90). Nous voyons que, à cause

de l'incarnation, la matière apparaît comme divinisée, elle est vue comme la

demeure de Dieu. Il s'agit d'une nouvelle vision du monde et des réalités

matérielles. Dieu s'est fait chair et la chair est devenue réellement demeure

de Dieu, dont la gloire resplendit sur le visage humain du Christ. C'est

pourquoi, les sollicitations du Docteur oriental sont aujourd'hui encore d'une

très grande actualité, étant donnée la très grande dignité que la matière a

reçue dans l'Incarnation, pouvant devenir, dans la foi, le signe et le sacrement

efficace de la rencontre de l'homme avec Dieu. Jean Damascène reste donc un

témoin privilégié du culte des icônes, qui deviendra l'un des aspects les plus

caractéristiques de la théologie et de la spiritualité orientale jusqu'à

aujourd'hui. Il s'agit toutefois d'une forme de culte qui appartient simplement

à la foi chrétienne, à la foi dans ce Dieu qui s'est fait chair et s'est rendu

visible. L'enseignement de saint Jean Damascène s'inscrit ainsi dans la

tradition de l'Eglise universelle, dont la doctrine sacramentelle prévoit que

les éléments matériels issus de la nature peuvent devenir un instrument de

grâce en vertu de l'invocation (epiclesis) de l'Esprit Saint, accompagnée par

la confession de la foi véritable.

Jean Damascène met également en relation avec ces idées de fond la vénération

des reliques des saints, sur la base de la conviction que les saints chrétiens,

ayant participé de la résurrection du Christ, ne peuvent pas être considérés

simplement comme des "morts". En énumérant, par exemple, ceux dont

les reliques ou les images sont dignes de vénération, Jean précise dans son

troisième discours en défense des images: "Tout d'abord (nous vénérons)

ceux parmi lesquels Dieu s'est reposé, lui le seul saint qui se repose parmi

les saints (cf. Is 57, 15), comme la sainte Mère de Dieu et tous les saints. Ce

sont eux qui, autant que cela est possible, se sont rendus semblables à Dieu

par leur volonté et, par l'inhabitation et l'aide de Dieu, sont dits réellement

dieux (cf. Ps 82, 6), non par nature, mais par contingence, de même que le fer

incandescent est appelé feu, non par nature mais par contingence et par

participation du feu. Il dit en effet: Vous serez saint parce que je suis saint

(Lv 19, 2)" (III, 33, col. 1352 A). Après une série de références de ce

type, Jean Damascène pouvait donc déduire avec sérénité: "Dieu, qui est

bon et supérieur à toute bonté, ne se contenta pas de la contemplation de

lui-même, mais il voulut qu'il y ait des êtres destinataires de ses bienfaits,

qui puissent participer de sa bonté: c'est pourquoi il créa du néant toutes les

choses, visibles et invisibles, y compris l'homme, réalité visible et

invisible. Et il le créa en pensant et en le réalisant comme un être capable de

pensée (ennoema ergon) enrichi par la parole (logo[i] sympleroumenon) et

orienté vers l'esprit (pneumati teleioumenon)" (II, 2, PG, col. 865A). Et

pour éclaircir ultérieurement sa pensée, il ajoute: "Il faut se laisser

remplir d'étonnement (thaumazein) par toutes les œuvres de la providence (tes

pronoias erga), les louer toutes et les accepter toutes, en surmontant la

tentation de trouver en celles-ci des aspects qui, a beaucoup de personnes,

semblent injustes ou iniques (adika), et en admettant en revanche que le projet

de Dieu (pronoia) va au-delà des capacités cognitives et de compréhension

(agnoston kai akatalepton) de l'homme, alors qu'au contraire lui seul connaît

nos pensées, nos actions et même notre avenir" (II, 29, PG, col. 964C). Du

reste, Platon disait déjà que toute la philosophie commence avec

l'émerveillement: notre foi aussi commence avec l'émerveillement de la

création, de la beauté de Dieu qui se fait visible.

L'optimisme de la contemplation naturelle (physikè theoria), de cette manière

de voir dans la création visible ce qui est bon, beau et vrai, cet optimisme

chrétien n'est pas un optimisme naïf: il tient compte de la blessure infligée à

la nature humaine par une liberté de choix voulue par Dieu et utilisée de

manière impropre par l'homme, avec toutes les conséquences d'un manque d'harmonie

diffus qui en ont dérivées. D'où l'exigence, clairement perçue par le

théologien de Damas, que la nature dans laquelle se reflète la bonté et la

beauté de Dieu, blessées par notre faute, "soit renforcée et

renouvelée" par la descente du Fils de Dieu dans la chair, après que de

nombreuses manières et en diverses occasions Dieu lui-même ait cherché à

démontrer qu'il avait créé l'homme pour qu'il soit non seulement dans

l'"être", mais dans le "bien-être" (cf. La foi orthodoxe,

II, 1, PG 94, col. 981°). Avec un enthousiasme passionné, Jean explique:

"Il était nécessaire que la nature soit renforcée et renouvelée et que

soit indiquée et enseignée concrètement la voie de la vertu (didachthenai

aretes hodòn), qui éloigne de la corruption et conduit à la vie éternelle...

C'est ainsi qu'apparut à l'horizon de l'histoire la grande mer de l'amour de

Dieu pour l'homme (philanthropias pelagos)...". C'est une belle

expression. Nous voyons, d'une part, la beauté de la création et, de l'autre,

la destruction accomplie par la faute humaine. Mais nous voyons dans le Fils de

Dieu, qui descend pour renouveler la nature, la mer de l'amour de Dieu pour

l'homme. Jean Damascène poursuit: " Lui-même, le Créateur et le Seigneur,

lutta pour sa créature en lui transmettant à travers l'exemple son

enseignement... Et ainsi, le Fils de Dieu, bien que subsistant dans la forme de

Dieu, abaissa les cieux et descendit... auprès de ses serviteurs... en

accomplissant la chose la plus nouvelle de toutes, l'unique chose vraiment

nouvelle sous le soleil, à travers laquelle se manifesta de fait la puissance

infinie de Dieu" (III, 1. PG 94, coll. 981C-984B).

Nous pouvons imaginer le réconfort et la joie que diffusaient dans le cœur des

fidèles ces paroles riches d'images si fascinantes. Nous les écoutons nous

aussi, aujourd'hui, en partageant les mêmes sentiments que les chrétiens de

l'époque: Dieu veut reposer en nous, il veut renouveler la nature également par

l'intermédiaire de notre conversion, il veut nous faire participer de sa

divinité. Que le Seigneur nous aide à faire de ces mots la substance de notre

vie.

* * *

J’accueille avec plaisir les pèlerins de langue française. Je salue en

particulier les pèlerins du diocèse de Bâle ainsi que les jeunes de Malines et

de Buzançais ainsi que ceux de l’École internationale de formation et

d’évangélisation de Paray-le-Monial. En ce temps pascal, je vous invite à

entrer dans une relation toujours plus intime avec le Christ qui est vivant

dans notre monde. Que Dieu vous bénisse!

Mes chers amis, vendredi je quitterai Rome pour une visite apostolique en

Jordanie, Israël et dans les Territoires palestiniens. Je profite de l'occasion

qui m'est donnée ce matin, à travers la radio et la télévision, pour saluer

toutes les populations de ces pays. J'attends avec impatience de pouvoir être

avec vous pour partager vos aspirations et vos espérances, tout comme vos

souffrances et vos combats. Je viendrai parmi vous en pèlerin de paix. Mon

intention principale est de visiter les lieux devenus saints par la vie de Jésus

et de prier dans ces lieux pour le don de la paix et de l'unité pour vos

familles et pour tous ceux dont la Terre Sainte et le Moyen Orient sont le

foyer. Parmi les nombreux rassemblements religieux et civils qui se dérouleront

au cours de la semaine, il y aura des rencontres avec les représentants des

communautés musulmanes et juives avec qui ont été accomplis de grands progrès

dans le dialogue et dans les échanges culturels. Je salue avec une affection

particulière les catholiques de la région et je vous demande de vous unir à moi

dans la prière afin que cette visite porte beaucoup de fruits pour la vie

spirituelle et civile de ceux qui vivent en Terre Sainte. Prions tous Dieu pour

sa bonté! Que nous puissions tous devenir un peuple d'espérance! Que nous

puissions être tous fermes dans notre désir et nos efforts de paix!

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20090506_fr.html

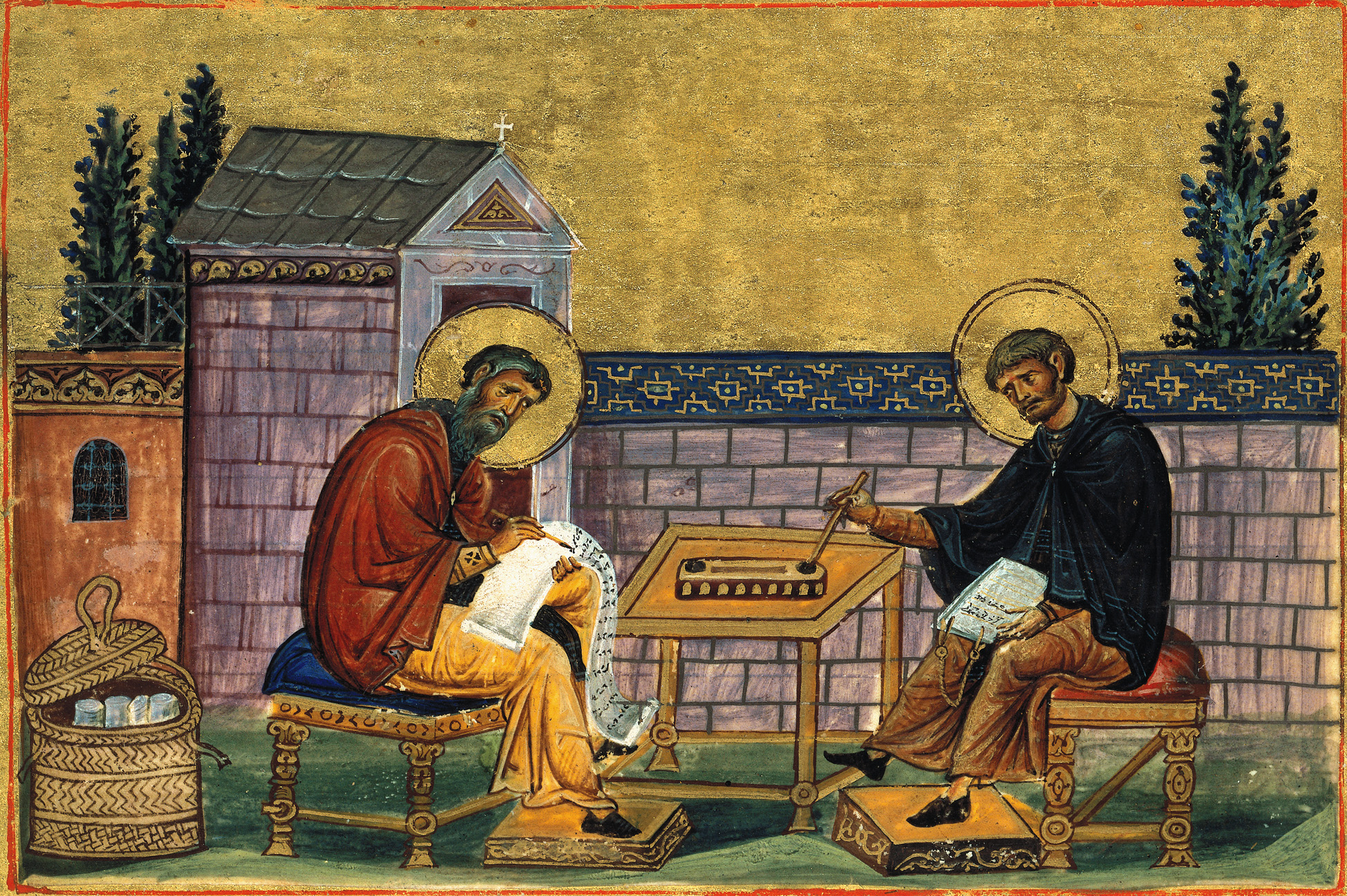

Saint

Jean de Damas tenant un rouleau avec une hymne à la Théotokos,

icône grecque de 1734.John of Damascus, painting by Michael Anagnostou

Chomatzas locate in

Ο Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Δαμασκηνός κρατώντας ειλητάριο με ύμνο προς τη Θεοτόκο (Μιχαήλ Αναγνώστου 1734 Βυζαντινό Μουσείο Χίου)

Le signe du Christ

La croix est un symbole

du Christ. Il a dit en effet à ses disciples en guise de

testament : « Alors paraîtra dans le ciel le signe du Fils de

l’homme » (Mt 24, 30), en parlant de la croix. Il faut donc se

prosterner devant le signe du Christ, car là où est son signe, lui aussi sera.

Cette croix précieuse,

l’arbre de la vie que Dieu planta dans le paradis (cf. Gn 2, 9) l’a

préfigurée (car, puisque la mort fut donnée par le bois, il fallait que par le

bois fussent données la vie et la résurrection [cf. préface du 14 septembre]).

Jacob, après s’être prosterné devant le sommet de son bâton (cf. Gn 47,

31 ; He 11, 21), a croisé les mains pour bénir les fils de

Joseph (cf. Gn 48, 14), traçant distinctement le signe de la croix. Le

bâton de Moïse, en signe de la croix, frappa la mer, sauva Israël et engloutit

Pharaon ; ses mains étendues, signe de la croix, mirent aussi en fuite

Amalec ; une baguette adoucit l’eau amère, brisa le rocher, fit jaillir

des flots d’eau (cf. Ex 14, 16-17 ; 17, 11 ; 15, 25 ;

17, 6) ; une verge concrétisa pour Aaron la dignité sacerdotale (cf.

Nb 17, 23) ; un serpent est exposé en trophée sur le bois (cf. Nb 21,

9 ; Jn 3, 14) : de même que ce serpent a été mis à mort quand le bois

a sauvé les croyants parmi ceux qui voyaient l’ennemi mort, de même le Christ a

été crucifié en une chair de péché (cf. Rm 8, 3) qui ne savait

rien du péché (cf. He 4, 15). Nous qui nous prosternons devant la croix,

puissions-nous avoir part au Christ crucifié !

St Jean Damascène

Saint Jean († 750), haut

fonctionnaire du calife à Damas avant de devenir moine à Saint-Sabas près de

Jérusalem, est parfois tenu pour le dernier des Pères de l’Église, dont il

récapitule toute la théologie. / La Foi orthodoxe 84 (IV, 11), trad.

P. Ledrux, Paris, Cerf, 2011, Sources Chrétiennes 540, p. 197-199.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/mardi-26-avril/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Platanias

(Creta, Grecia), museo del monastero di Gonia Odigitria - Icona di san Giovanni

Damasceno, realizzata dallo ieromonaco Parthenios, seconda metà XVII secolo

Platanias

(Crete, Greece), Gonia Odigitria monastery museum - Icon of saint John of

Damascus, by hieromonk Parthenios, second half 17th century

Voir l’image de Dieu

Saint Jean de Damas, que

nous fêtons en ce jour, fut l’un des plus grands défenseurs de la vénération

des icônes.

Puisque certains nous

font reproche de nous prosterner devant l’image de notre Sauveur et celle de

notre souveraine, Marie, et de les vénérer ainsi que celles des autres saints

et serviteurs du Christ, qu’ils apprennent qu’au commencement Dieu créa l’homme

à sa propre image (Gn 1, 27). Pourquoi donc nous prosternons-nous les

uns devant les autres, si ce n’est parce que nous avons été créés à l’image de

Dieu ? Or, comme le dit Basile, le porte-Dieu et savant ès choses divines,

« l’honneur rendu à l’image passe à l’original ».

Qui peut faire une

imitation du Dieu invisible, incorporel, sans contours et sans figure ?

Donner une figure à la divinité relève effectivement de l’extrême démence et de

l’impiété. De là vient que dans l’ancienne Alliance l’usage des images n’avait

pas cours. Mais quand Dieu, de par les entrailles de sa

miséricorde (Lc 1, 78), se fit véritablement homme pour notre salut, il ne

se fit pas voir comme à Abraham (cf. Gn 18, 2) ou comme aux prophètes

sous une apparence humaine ; il se fit vraiment homme.

Voir l’image du Christ

crucifié nous remet en mémoire la Passion qui nous sauve et, tombant à genoux,

nous nous prosternons non devant la matière, mais devant ce qui est représenté,

de même que notre prosternation ne s’adresse pas à la matière de l’Évangile,

non plus qu’à la matière de la croix, mais à la reproduction figurative. En

quoi diffèrent, en effet, la croix qui ne porte pas la reproduction de l’image

du Seigneur et celle qui la porte ?

St Jean de Damas

Saint Jean († 750), haut

fonctionnaire du calife à Damas avant de devenir moine à Saint-Sabas près de

Jérusalem, est parfois tenu pour le dernier des Pères de l’Église, dont il

récapitule toute la théologie. / La Foi orthodoxe 89 (IV, 16), trad.

P. Ledrux, Paris, Cerf, Sources chrétiennes 540, 2011, p. 237-241.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-4-decembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Docteur de l'Église

(776-880)

Saint Jean Damascène, ainsi nommé parce qu'il naquit à Damas, en Syrie, est le

dernier des Pères grecs et le plus remarquable écrivain du huitième siècle.

Son père, quoique zélé chrétien, fut choisi comme ministre du calife des

Sarrasins, et employa sa haute situation à protéger la religion de

Jésus-Christ. Il donna comme précepteur à son fils un moine italien devenu

captif, et auquel il rendit la liberté. Ce moine se trouvait être un saint et

un savant religieux; à son école, Jean développa d'une manière merveilleuse son

génie et sa vertu.

A la mort de son père, il fut choisi par le calife comme ministre et comme

gouverneur de Damas. Dans ces hautes fonctions, il fut, par la suite d'une vile

imposture et d'une basse jalousie, accusé de trahison. Le calife, trop

promptement crédule, lui fit couper la main droite. Jean, ayant obtenu que

cette main lui fût remise, se retira dans son oratoire, et là il demanda à la

Sainte Vierge de rétablir le membre coupé, promettant d'employer toute sa vie à

glorifier Jésus et Sa Mère par ses écrits. Pendant son sommeil, la Sainte

Vierge lui apparut et lui dit qu'il était exaucé; il s'éveilla, vit sa main

droite jointe miraculeusement au bras presque sans trace de séparation. Le

calife, reconnaissant, à ce miracle, l'innocence de son ministre, lui rendit sa

place; mais bientôt Jean, après avoir distribué ses biens aux pauvres, se

retira au monastère de Saint-Sabas, où il brilla par son héroïque obéissance.

Ordonné prêtre, il accomplit sa promesse à la Sainte Vierge en consacrant

désormais le reste de ses jours à la défense de sa religion et à la

glorification de Marie. Il fut, en particulier, un vigoureux apologiste du

culte des saintes Images, si violemment attaqué, de son temps, par les

Iconoclastes.

Ses savants ouvrages, spécialement ses écrits dogmatiques, lui ont mérité le

titre de docteur de l'Église. Il a été, par sa méthode, le précurseur de la

méthode théologique qu'on a appelée Scholastique. Ses nombreux et savants

ouvrages lui laissaient encore du temps pour de pieux écrits.

Sa dévotion envers la Très Sainte Vierge était remarquable; il L'appelait des

noms les plus doux. A Damas, Son image avait occupé une place d'honneur dans le

palais du grand vizir, et nous avons vu par quel miracle il en fut récompensé.

Les discours qu'il a composés sur les mystères de Sa vie, et en particulier sur

Sa glorieuse Assomption, font assez voir comment il était inspiré par Sa divine

Mère. Ses immenses travaux ne diminuèrent point sa vie, car il mourut à l'âge

de cent quatre ans.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame,

1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jean_damascene.html

A

Georgian fresco and inscriptions from Jerusalem. Sts. John of Damascus, Maximus

Confessor, with Shota Rustaveli praying.

Saint Jean Damascène

(environ 650-750)

Docteur de l'Eglise.

Jean naquit à Damas d'une famille chrétienne noble d'origine arabe, vers 650.

La ville est alors soumise aux musulmans. Il reçut une éducation et une bonne

connaissance de la culture grecque et arabe. Comme son père, il fut au service

des califes Omeyyades, pendant quelques années.

Par fidélité à la foi chrétienne, il laissa tout, donna ses biens aux pauvres,

et entra comme moine dans le monastère de Saint Saba, près de Jérusalem. il est

ordonné prêtre par Jean IV, patriarche de Jérusalem (706 - 736), et il continua

sa mission de professeur, prédicateur et écrivain, développant la théologie de

l'incarnation surtout et de la transfiguration. Il mourut vers 750, à un âge

très avancé.

Enseignements :

Damas était déjà une cité musulmane. Jean Damascène analysa le coran, le

compara à la Bible, et en déduisit que l'islam était une hérésie.

Jean Damascène souligne le fait que, en prenant la condition humaine, le Christ

lui apporte le salut et appelle l'être humain à partager la vie divine, à

connaître la déification.

C'est ce qu'il met en évidence dans sa réflexion sur les icônes qui

représentent l'humanité transfigurée ou dans sa célèbre Homélie sur la

Transfiguration.

Le concile de Nicée II a reconnu et a repris sa pensée pour la défense du culte

des icônes sacrées parce qu'il a su allier la théologie de l'incarnation et la

théologie de la beauté, en créant un espace liturgique où "le ciel est

descendu sur la terre."

La doctrine mariale de Jean Damascène peut être considérée comme une synthèse

exhaustive et puissante de tout l'enseignement des auteurs chrétiens qui l'ont

précédé.

Sont particulièrement importantes quatre homélies mariales : une sur la

Nativité de la Vierge, trois sur la Dormition.

Avec Germain de Constantinople et André de Crète, Jean Damascène est cité dans

le Munificentissimus Deus de Pie XII; et son nom apparaît aussi dans le

chapitre VIII de la Lumen Gentium du concile Vatican II, et dans la lettre

encyclique Redemptoris Mater de Jean Paul II.

Jean Damascène fut aussi un grand hymnographe qui a célébré la Vierge Marie par

ses hymnes dont beaucoup sont entrés dans la liturgie byzantine.

Bibliografia

- M. SCHUMPP, Zur Mariologie des hl. Johannes Damascenus, in Divus Thomas

2 (1924), 222-234.

- A. MITCHEL, The Mariology of St John Damascene, Kirkwood, Missouri 1930.

- C. CHEVALIER, La Mariologie de Saint Jean Damascène, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 109, Roma 1936.

- V. GRUMEL, « La Mariologie de Saint Jean Damascène », in Echos d'Orient 40 (1937),318-346.

- J. M. CANAL, « San Juan Damasceno, doctor de la muerte y de la asuncion de Maria », in Estudios Marianos 12 (1952),270-330.

- L. FERRONI, « La Vergine, nuova Eva, cooperatrice della divina economia e mediatrice, secondo il Damasceno », in Marianum 17 (1955),1-36.

- B. M. GARRIDO, « Lugar de la Virgen en la Iglesia, segun san Juan Damasceno », in Estudios Marianos 28 (1966),333-353.

- D. DIMITRIJEVIC, « Die Entwicklung der liturgischen Verehrung der Mutter Gottes nach dem Ephesinum bis rum 12. Jahrhundert », in De cultu mariano saeculis VI-XI, vol. IV, Roma 1972,101-1 lO.

- F. M. JELLY , « Mary's Mediation in the Distribution of Grace according to

Sto Jobn Damascene's Homilies in her Dormition », Ibid., 301-312.

Françoise

Breynaert

Saint Jean Damascène :

Marie et le Sinaï (St Jean

Damascène)

Marie immaculée

dans sa conception (St Jean Damascène)

Beauté de Marie,

arbre de vie (St Jean Damascène)

Les vertus attirent Marie et

Jésus en nous

Marie mère de Dieu (St Jean

Damascène)

Elie et l’Assomption de Marie

L’arche d’Alliance et

l’Assomption de Marie

Assomption et

royauté de Marie (St Jean Damascène)

L'Assomption

: du sanctuaire de Gethsémani à celui de Blacherne

Marie échelle

de Jacob et médiatrice (St Jean Damascène)

Culte et consécration

marials (St Jean Damascène)

Saint Jean Damascène et les icônes

SOURCE : http://www.mariedenazareth.com/2212.0.html?&L=0

Afresco

de São João de Damasco em Chora

Lecture

Le Divin est ineffable et incompréhensible. « En effet, personne ne connaît Le Père si ce n’est Le Fils, et personne ne connaît Le Fils si ce n’est Le Père ». Et L’Esprit saint aussi connaît ce qui est de Dieu, de même que l’esprit de l’homme connaît ce qui est dans l’homme.

Personne n’a jamais connu Dieu, si ce n’est celui auquel lui-même l’a révélé. Dieu, pourtant, ne nous a pas abandonné dans une ignorance totale.

En effet, la connaissance de Dieu a été ensemencée par lui, conformément à la nature, en tout homme.

La Création elle-même, sa sauvegarde et son organisation proclament la grandeur de la nature Divine. De plus, d’abord par le moyen de la Loi et des Prophètes, puis par son Fils unique, Le Seigneur Notre Dieu et Sauveur Jésus Christ, Dieu a révélé la connaissance de Lui-même par tout ce qui nous est accessible.

C’est pourquoi nous accueillons, nous reconnaissons et nous vénérons ce qui

nous a été transmis par la Loi, les Prophètes, les Apôtres et les Evangélistes,

sans rien rechercher au-delà de ces médias.

Jean Damascène, La Foi Orthodoxe

Prière

Accorde-nous, Seigneur,

de trouver un appui

dans les prières de saint Jean Damascène ;

que la vraie Foi,

dont il fut un maître éminent,

soit toujours notre force et notre lumière.

Les

trois saints Georges, Jean Damascène et Éphrem le Syrien. Part d'un

triptyque, peut-être constantinoplois.

Monastaire

Sainte Catherine, Sinai (Egypte). Début du 14ième siècle. 21,4 x 9,5

Saint Jean de Damas

docteur de l'église catholique

Au VIIe siècle, sous

l'influence croissante de l'Islam, un empereur de Constantinople, Léon III

l'Isaurien, ordonnait par un édit d'ôter des églises et des lieux publics les

tableaux et statues sacrés qui y étaient exposés à la vénération des fidèles;

cet arrêt devait être sanctionné par des violences inouïes. De la persécution

des iconoclastes ou briseurs d'images, on retrouvera plus tard l'esprit chez

les Albigeois, les Vaudois, les Hussites et les Protestants. A travers les

siècles et jusqu'à nos jours, dans l'esprit des chrétiens et surtout en Orient,

la tyrannie hérétique de Léon l'Isaurien évoque principalement le nom de saint

Jean Damascène qui fut avec saint Germain de Constantinople et Georges de

Chypre, à la tête des défenseurs des saintes icônes. Toutefois, c'est

restreindre sa gloire légitime que de ne voir que cela en lui. Il est plus

justement apprécié par l’Église orientale, qui le regarde comme le meilleur de

ses théologiens.

Saint Jean est né à Damas

vers l'année 675 d'une famille chrétienne d'origine arabe probablement de la

tribut des Ghassanides, son grand-père était un chef arabe qui s'appelait Al

Mansour. En effet l'empire Byzantin utilisait les tribus arabes dans son propre

système de défense face à la Perse. En 630, avec l'aide des tributs arabes,

l'empereur Byzantin Héraclius avait pu chasser les Perses du Proche-Orient et

ramené la Croix à Jérusalem. Les Byzantins, que les arabes appellent les

"Roums" c'est à dire Romains utilisaient les tribus arabes pour

défendre les frontières sud de leur Empire. Mais en 636, lors de l'invasion

musulmane du Proche-Orient, la cavalerie des ghassanides refusa de combattre

leurs frères arabes et après des négociations entre tributs, les ghassanides se

sont joint à l'armée Arabe pour battre à Yarmouk, l'armée Byzantine qui n'était

plus que l'ombre d'elle même. D'ailleurs Damas, malgré les légendes qui se sont

développés dans le monde musulman, n'a pas été conquise militairement, bien au

contraire, ce sont les arabes chrétiens qui, pour se débarrasser des Byzantins,

ont aidé l'armée musulmane aà prendre la ville. Un accord entre la majeure

partie des habitants, qui étaient des Chrétiens Arabes, et Abû `Ubaydah fut

signé.

Le père de Saint Jean qui

s'appelait Serge, était un chrétien fervent et occupait un poste important

auprès du nouveau Calife Mouawiya. Le nouveau calife refusa de résider à Médine

et transféra en 660, le siège du Califat à Damas. Serge dépensait en œuvres de

charité ses revenus, et surtout il profita de sa situation pour racheter les

captifs chrétiens. Et parmi ces derniers, se trouvait un religieux venu de

Sicile, futur évêque et hymnographe orthodoxe, nommé Cosmas de Maïouma, ou

Cosmas de Jérusalem, très versé dans la philosophie, et parlant plusieurs

langues. Or, précisément, Serge Mansour cherchait depuis longtemps un homme

capable de donner à son fils une éducation convenable. La Providence le

comblait en lui faisant trouver un trésor d'érudition et de piété dans ce

captif qu'on allait égorger. Il courut le demander au calife qui n'y fit aucune

objection. Cosme reçut la liberté, et devint l'ami du père et le maître du

fils, qui, sous sa direction apprit avec un succès prodigieux les linéaments de

la belle méthode aristotélicienne qui sera si en faveur au moyen âge. C'est

dans cette environnement que grandit Saint Jean.

Quand l'éducation de Jean

fut achevée, le moine dit à Serge: Vos vœux sont accomplis, la sagesse de votre

enfant surpasse la mienne: Dieu complétera l'œuvre. Je vous prie de me laisser

me retirer au désert, afin de vaquer à la céleste contemplation. Serge fit la

plus grande résistance, mais il dut céder aux vœux ardents du saint moine, qui

se retira en Palestine, dans la laure de Saint-Sabas.

L’orient chrétien devait

être agité pendant plus d'un siècle (725-840) par l'hérésie iconoclaste, et

particulièrement sous le règne de l'empereur Léon III l'Isaurien. Ce rustre

couronné, ancien marchand de bestiaux, puis heureux soldat, était monté sur le

trône de Constantinople en l'an 716. Arrivé au pouvoir au milieu d'une

véritable anarchie, il venait de se révéler comme un homme d’État de premier

ordre, et il peut être regardé comme le réorganisateur de l'Empire byzantin.

Mais en proscrivant le culte des images, à quel mobile obéissait-il? Avait-il

gardé quelque sympathie, manifestée dans sa jeunesse, pour cette terrible secte

des pauliciens, issue du manichéisme, qui avait mis à feu et à sang l'Asie

Mineure, incendiant les églises d'Arménie et de Syrie, et détruisant partout

les saintes icônes? Plus vraisemblablement, il avait l'ambition, sorte

d'empereur-sacristain, d'étendre au sanctuaire les réformes qu'il était fier

d'avoir réalisées dans l'ordre social et militaire: à coup sûr, il ne prévoyait

pas que ces querelles iconoclastes allaient séparer Constantinople de Rome, et

rapprocher Rome de Charlemagne, l'empereur d'Occident. Avant d'arriver aux

mesures de violence, Léon III l'Isaurien avait procédé peu à peu à

l'«épuration» de l'épiscopat oriental; il devait, après la persécution, qui

commença à l'automne de 725, mettre en demeure saint Germain, patriarche de

Constantinople, d'adhérer à l'hérésie ou de se retirer.

En terre musulmane, les

Églises melkites n'avaient rien à craindre de l'empereur chrétien; elles

restèrent fidèles au culte des saintes images, grâce à Georges de Chypre et à

Jean de Damas.

Des témoins racontent:

Jean parle avec éloquence du culte qui est rendu aux

Saints dans l’Église

catholique. Le culte qui s'adresse à une créature est motivé par une relation,

un rapport de cette créature avec Dieu. Ce principe général s'applique à la

fois au culte des Saints et de leurs reliques, et au culte des Images en

général. Nous vénérons les Saints à cause de Dieu, parce qu'ils sont ses

serviteurs, ses enfants et ses héritiers, des «dieux» par participation, les

amis du Christ, les temples vivants du Saint-Esprit. Cet honneur rejaillit sur

Dieu lui-même, qui se considère comme honoré dans ses fidèles serviteurs, et

nous comble de ses bienfaits. Les Saints sont, en effet, les patrons du genre

humain. Il faut bien se garder de les mettre au nombre des morts. Ils sont

toujours vivants, et leurs corps mêmes, leurs reliques méritent aussi notre

culte.

En dehors des corps des

Saints, méritent aussi notre culte, mais culte relatif, qui remonte à

Jésus-Christ ou à ses Saints, toutes les autres reliques et choses saintes,

qu'il s'agisse de la vraie croix et des autres instruments de la Passion ou des

objets et lieux consacrés par la présence ou le contact de Jésus-Christ, de la

Sainte Vierge ou des Saints. Ces mêmes principes trouvent leur application

toute logique dans le culte rendu aux saintes images. Ce culte «présente pour

les fidèles de multiples avantages: l'image est d'abord le livre des ignorants;

c'est une exhortation muette à imiter les exemples des Saints; c'est enfin un

canal des bienfaits divins.»

Quand l'empereur byzantin

voit se dresser en face de lui Jean Damascène, un adversaire redoutable à la

cour même des califes, c'est-à-dire hors de sa portée il décide de se venger

d'une manière hypocrite et cruelle: il fait remettre au calife une lettre

écrite par un faussaire, signée du nom de Jean Serge Mansour et invitant

l'empereur de Byzance à s'emparer de Damas. On conçoit la colère du calife

devant cette pièce à conviction, qui est pour lui la preuve d'une trahison.

Aussitôt, il fait mander saint Jean et lui fait trancher la main droite. Le

martyr supporte courageusement ce supplice, rentre dans son oratoire privé; il

se met en prière devant une image de la Très Sainte Vierge, suppliant la Mère

de Dieu de lui rendre l'usage de sa main pour lui permettre de reprendre la

plume. Alors il s'endort; la Vierge de l’icône abaisse sur son chevaleresque

défenseur un regard maternel et lui rend l'usage de sa main, autour de laquelle

un mince liseré rouge persistera pour attester le prodige.

Dès lors, l'heureux

miraculé renonce au monde et va s'enfermer dans la solitude de Saint-Sabas, où

il continuera d'écrire à la louange de Marie.

Une autre tradition,

s'ajoute à la précédente: sur l’icône miraculeuse, Jean avait suspendu en

ex-vota une main d'argent, de même qu'en certains sanctuaires on a offert et

peut-être offre-t-on encore des figurines de représentant têtes, mains ou

jambes, correspondant à des parties du corps pour lesquelles les fidèles ont

obtenu la guérison. L’icône avec son ex-voto fut conservée comme une relique

précieuse sous le nom de «Vierge Damascène» ou de « Vierge à trois mains».

Quelle que soit son origine, cette image a une histoire que raconte ainsi le P.

Joseph Goudard :

Au XIIIe siècle, elle fut

remise par le supérieur de la laure à saint Sabas métropolite de Serbie et

grand serviteur de Notre-Dame, dans un de ses deux pèlerinages en Terre Sainte.

De retour dans son pays, le prélat en fit don à son frère, Étienne, roi de

Serbie, de la dynastie des Némanya, lui recommandant de la garder et de

l'honorer d'un culte spécial comme un très précieux trésor de famille. Plus

tard, après l'extinction des Nérnanyn, l’icône fut transférée au Mont Athos, la

montagne de Marie, et déposée au monastère de Kilandar. Cette «Vierge Damascène

» a eu une très grande célébrité en Orient. Les peintres la prirent pour

modèle, et telle est l'origine de ces curieuses peintures où la Sainte Vierge

est représentée avec trois mains. Les Serbes allèrent plus loin; ce titre de

«Vierge à triple main», ils en ont fait le vocable de plusieurs de leurs

églises cathédrales réputées «thaumaturges » encore aujourd'hui, telles

Notre-Dame d'Uskub, Notre Dame de Skoplie , etc.

Jean Damascène fut à la

fois philosophe, théologien, orateur ascétique, historien, exégète, poète même.

Le principal de ses écrits dogmatiques est la Source de la connaissance. Il

comprend trois grandes divisions. La première, appelée Dialectique, met sous

les yeux du lecteur ce qu'il y a de meilleur dans la philosophie grecque; la deuxième,

tout historique, est un clair résumé des hérésies apparues dans l’Église

jusqu'à celle des iconoclastes: l'auteur y expose et réfute tout au long le

mahométisme. La troisième partie comprend son grand ouvrage bien connu:

Exposition de la foi orthodoxe. Il y parle de Dieu, de ses œuvres, de ses

attributs, de sa Providence, de l'Incarnation, des Sacrements; sur chaque

vérité il résume l’Écriture et la Tradition.

Il est vraisemblable que ce dernier écrit fut composé au monastère de Saint-Sabas. Le texte nous en a été conservé dans une traduction arabe. Cet ouvrage est d'une grande importance pour l'histoire de la théologie; malgré ses lacunes, il est le fidèle écho des enseignements des Pères de l'Eglise qui ont précédé son auteur, et on a dit qu'il représente la première Somme théologique digne de ce nom. Le mystère de l'Incarnation est celui sur lequel Jean Damascène s'étend le plus longuement; sa théologie mariale, soit dans ce traité soit en d'autres ouvrages, est irréprochable: ici encore, interprète de renseignement des autres théologiens byzantins. il expose d'une manière admirable les vues les plus orthodoxes sur l’Immaculée Conception (bien avant Lourdes) et la virginité perpétuelle de Marie, son rôle de corédemptrice du genre humain par sa libre coopération au plan divin; son Assomption, sa royauté sur les créatures, sa médiation universelle et sa maternité de grâce.

L’exposition de la foi

orthodoxe fut mise à contribution souvent d'une façon inavouée par les

théologiens byzantins; elle fut traduite en paléoslave, vers la fin du IXe

siècle, par les soins de Jean, exarque de Bulgarie; en Russie, elle a été

imprimée plusieurs fois. Les Byzantins ont surnommé Jean Damascène Chrysorrhoas

(qui roule de l'or), et ce nom dit assez toute l'admiration que la postérité a

vouée à sa personne et à ses travaux. Nul n'est prophète dans son pays. Les

étrangers ont reconnu la grandeur de Saint Jean de Damas mais les arabes, ses

propres fères, l'ont rejeté.

Saint Jean Damascène est

considéré comme l'auteur d'un grand nombre de chants, savants et populaires,

dont on voit quelques-uns cités dans les anthologies de musique religieuse,

anciennes et modernes. En tels d'entre eux la Très Sainte Vierge est chantée

d'une manière heureuse; il a composé aussi des tropaires dans lesquels il

demande pour les défunts le repos éternel, ce qui est très important pour

l'histoire de la croyance au purgatoire. On a même voulu faire du moine de

Saint-Sabas l'organisateur du chant liturgique grec, l'inventeur de la notation

musicale qui porte son nom, l'auteur de l'Octoekos, livre liturgique d'un

charme et d'une fraîcheur antiques, qui sous huit tons musicaux contient des

tropaires et des canons sur la Résurrection, la Croix, la Vierge.

Le Père Pargoire déclare toutefois que s'il a jeté les bases du célèbre recueil, «Jean le Moine » ne l'a certainement pas bâti seul, ni tout d'une pièce, car d'autres, même au IXe siècle, apporteront leur pierre à cet édifice. D'autre part, un historien de la musique byzantine, le P. Joannès Thibaut, affirme que « le Canon musical prouve que Jean Damascène connaissait son art à la perfection, et qu'il était, suivant L’expression consacrée, un musicien dans l'âme. »

Pour mémoire encore,

enregistrons une autre tradition touchante: la Vierge Marie «venant doucement

gourmander l'archimandrite de la laure, homme austère qui saisissait

difficilement la portée apostolique des livres et surtout de la poésie.

- Pourquoi, lui dit Notre-Dame, pourquoi empêches-tu cette source de donner ses eaux limpides, lesquelles, en coulant sur le monde, emporteront les hérésies?»

Comme ou peut le voir, la

trame de la vie de Jean Damascène est aussi ténue que possible, au moins dans

la mesure où nous la connaissons. On pourrait même se demander pourquoi

l’Église le vénère comme Saint. Comme s'il répondait précisément à cette

question, le P. Jugie remarque judicieusement:

Sa sainteté, on la voit transparaître dans ses œuvres. Le ton d'humilité sincère avec lequel il parle de lui-même en plusieurs endroits de ses écrits, allant jusqu'à se traiter d'homme ignorant, son amour pour Jésus-Christ, sa tendre dévotion à Marie, son dévouement pour l’Église qui lui a fait composer tous ses ouvrages, tout cela nous montre que le docteur de Damas appartient à la race des grands Saints qui ont illustré l’Église à la fois par leur science et par leur vertu.

Selon la tradition Saint

Jean Damascène est mort le 4 décembre 749. Un concile des briseurs d'images

réuni, le 10 février 753, au palais impérial de Hiéria, près de Chalcédoine,

avec le bienveillant appui de l'empereur byzantin Constantin Copronyme,

enregistrait avec une joie apparente la mort des trois défenseurs des saintes

images, saint Germain, Georges de Chypre et saint Jean Damascène, par une

formule demeurée célèbre: La Trinité a fait disparaître les trois. Reprenant

cette phrase et la rectifiant d'une manière heureuse, le VIle Concile

œcuménique, réuni à Nicée en 787 et qui condamna l'hérésie des iconoclastes,

déclara: «La Trinité a glorifié les trois»: la sixième session de ce même

Concile entendit l'éloge de saint Jean Damascène; la septième proclama sa

«mémoire éternelle».

Le corps de saint Jean Damascène fut conservé pendant au moins quatre siècles dans la laure de Saint-Sabas; plus tard, il fut transporté à Constantinople. Certains Martyrologes latins semblent faire allusion à cette translation en inscrivant au 6 mai la mention suivante: «A Constantinople, déposition de Jean Damascène, de sainte mémoire, docteur insigne. »

Le couvent de Saint-Sabas

conserve deux tableaux qui représentent le Saint. Sur le premier, on voit un

vieillard à cheveux blancs, la figure rayonnante de beauté et de majesté,

penché sur un parchemin, écrivant et chantant les louanges de Marie, telles que

les a conservées la liturgie de l’Église grecque. Sur le second, qui couronne

l'entrée du tombeau de saint Jean, on voit un moine étendu sur son lit funèbre;

sur sa poitrine, il a les mains jointes, contre lesquelles on a déposé une

petite icône de Marie portant l'Enfant Jésus; la multitude des moines entoure

le corps, qui semble plutôt reposer après une dure journée de travail.

De temps immémorial on

montrait dans le quartier chrétien de Soufanieh à Damas, non loin de la porte

de Bab Touma, une ruine appartenant au wouakf dépendant de la grande mosquée et

connu de toute la ville sous le nom de maison de saint Jean Damascène. En 1878,

après de longues démarches, les Jésuites achetèrent cette ruine et la

transformèrent en un sanctuaire. Si en Occident Saint Jean de Damas fait parti

des Docteurs de l'Eglise, malheureusement à Damas et dans le monde arabe, rares

sont ceux qui le connaissent ou qui ont jamais lu ses oeuvres.Contactez-nous

Copyright © 0002.net Tous droits réservés

SOURCE : http://orient.chretien.free.fr/jeanDeDamas.htm et https://www.reflexionchretienne.com/pages/vie-des-saints/decembre/saint-jean-damascene-jean-de-damas-pretre-et-docteur-de-l-eglise-749-fete-le-04-decembre.html

Фрески

во Црквата „Св. Архангел Михаил“ Лесновскиот Манастир во Лесново пробиштипско,

прилепско

Frescos

in St. Michael the Archangel Church in Lesnovo, Macedonia

Фресок Лесновского монастыря Македония

Saint Jean Damascène

Prêtre et docteur de l'Eglise

Jean naît, vers 650, dans

une riche famille arabe et chrétienne de Damas, les Mansûr, dont les

hommes occupent des postes officiels, tant sous les empereurs byzantins que, à

partir de 636, sous les califes. Compagnon d'enfance du futur calife Yazid, il

reçoit, avec son frère adoptif, Cosmas, une bonne éducation à la fois grecque

et arabe. Ils ont comme précepteur un moine italien, autre Cosmas, naguère pris

comme esclave en Sicile par les Sarrasins et que Sergius, père de Jean, avait

racheté. Leur ayant appris tout ce qu'il pouvait savoir de rhétorique, de

dialectique, d'arithmétique, de philosophie et de théologie, le savant Cosmas

se retire au monastère de Saint-Sabas, tandis que son premier élève rejoint son

père à la cour du calife pour être initié aux affaires de l'Etat, et que

l'autre s'en va parfaire ses études ecclésiastiques à Jérusalem.

A la mort de Sergius, son

fils lui succède et prend un tel ascendant sur l'esprit des califes qu'il est,

vers 730, créé grand vizir. Lorsque l'empereur Léon d'Isaurien prescrit de

détruire les saintes images (730), Jean Damascène s'y oppose très

vigoureusement et publie trois adresses. Pour élimer cet intelligent

adversaire, l'empereur byzantin envoie au Calife une lettre rédigée par des

faussaires, selon laquelle Jean ne se proposait rien moins que de lui livrer

Damas. En possession du faux, le Calife refuse d’écouter son grand vizir et le

renvoie après lui avoir fait trancher la main droite ; Jean récupère sa main et

se retire dans son oratoire pour s'adresser ainsi à la sainte Vierge :

« Très pure Vierge Marie qui avez enfanté mon Dieu, vous savez pourquoi on

m'a coupé la main droite, vous pouvez, s'il vous plaît, me la rendre et la

rejoindre à mon bras. Je vous demande avec instance cette grâce pour que je

l'emploie désormais à écrire les louanges de votre Fils et les

vôtres. » La Vierge lui apparaît pendant son sommeil et lui dit :

« Vous êtes maintenant guéri, composez des hymnes, écrivez mes louanges,

accomplissez ainsi votre promesse. » Le Calife reconnaît l'innocence de

Jean et le rétablit dans ses fonctions qu'il conserve le temps d'instruire son

successeur et de mettre de l'ordre dans ses affaires.

Délivré des affaires du

monde, il partage ses biens entre sa famille et les pauvres, puis rejoint les

deux Cosmas, son ancien précepteur et son frère adoptif, appelé l'Hagiopolite,

à la laure de Saint-Sabas ; après que de nombreux moines se sont jugés indignes

sa formation, l'higoumène de Mar-Saba, Nicodème, le confie à un vieux moine

triste, ennemi de la poésie et de la musique, qui lui interdit d'écrire et le livre

à toutes sortes d'humiliations ridicules. Ayant supporté en silence cet affreux

noviciat, Jean Damascène, autorisé à étudier et à écrire, compose ses fameuses

hymnes. Ordonné prêtre, vers 735, par Jean de Jérusalem, un peu avant que son

frère adoptif devienne évêque de Majuma (Palestine) Jean Damascène ne quitte

plus son monastère que pour prêcher. Il mourut à Mar-Saba très vieux, dit-on,

entre 754 et 780.

O fille du roi David et

Mère de Dieu, roi universel.

O divin et vivant objet

dont la beauté a charmé le Dieu créateur,

vous dont l'âme est toute

sous l'action divine

et attentive à Dieu seul

;

tous vos désirs sont

tendus vers Celui-là seul

qui mérite qu'on le

cherche et qui est digne d'amour ;

vous n'avez de colère que

pour le péché et son auteur.

Vous aurez une vie

supérieure à la nature

mais vous ne l'aurez pas

pour vous,

vous qui n'avez pas été

créée pour vous.

Vous l'aurez consacrée

tout entière à Dieu

qui vous a introduite

dans le monde

afin de servir au salut

du genre humain,

afin d'accomplir le

dessein de Dieu,

l'Incarnation de son Fils

et la déification du genre humain.

Votre coeur se nourrira

des paroles de Dieu :

elles vous féconderont,

comme l'olivier fertile

dans la maison de Dieu,

comme l'arbre planté au

bord des eaux vives de l'Esprit,

comme l'arbre de vie qui

a donné son fruit au temps fixé :

le Dieu incarné, la vie

de toutes choses.

Vos pensées n'auront

d'autre objet que ce qui profite à l'âme,

et toute idée non

seulement pernicieuse, mais inutile,

vous la rejetterez avant

même d'en avoir senti le goût.

Vos yeux seront toujours

tournés vers le Seigneur,

vers la lumière éternelle

et inaccessible ;

vos oreilles attentives

aux paroles divines

et au son de la harpe de

l'Esprit

par qui le Verbe est venu

assumer notre chair. (...)

O Vous qui êtes à la fois

fille et souveraine de Joachim et d'Anne,

Accueillez la prière de

votre pauvre serviteur :

il n'est qu'un pécheur,

et, pourtant, de tout son

coeur, il vous aime et vous honore.

C'est en vous

qu'il veut trouver la

seule espérance de son bonheur,

le guide de sa vie,

la réconciliation auprès

de votre Fils

et le gage assuré de son

salut.

Délivrez-moi du poids de

mes fautes,

dispersez l'obscurité

accumulée autour de mon esprit,

débarrassez-moi de mon

épaisse boue,

arrêtez mes tentations,

gouvernez ma vie avec

bonheur

et conduisez-moi au

bonheur du ciel.

Accordez la paix au

monde.

Donnez à tous les

chrétiens de cette ville

la joie parfaite et le salut

éternel.

Nous vous en supplions,

obtenez-nous d'être

sauvés,

d'être délivrés des

passions de nos âmes,

d'être guéris des

maladies de nos corps,

d'être délivrés de nos

difficultés ;

obtenez-nous une vie

tranquille dans la lumière de l'Esprit.

Enflammez-nous d'amour

pour votre Fils.

Que notre vie lui soit

agréable,

pour que,

établis dans la béatitude

du ciel,

nous puissions vous voir

un jour

resplendir dans la gloire

de votre Fils,

pour que nous puissions

chanter, dans une joie sans fin,

des hymnes saintes d'une

manière digne de l'Esprit,

au milieu de l'assemblée

des élus,

en l'honneur de Celui

qui, par vous, nous a sauvés,

le Christ, Fils de Dieu

et notre Dieu.

A lui soient la puissance

et la gloire,

avec le Père et l'Esprit,

maintenant et toujours,

dans les siècles des

siècles.

Amen.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/12/04.php

San Giovanni Damasceno

St Jean Damascène,

confesseur et docteur

Mort probablement le 4 décembre vers 749. Inscrit par Baronius dans le

martyrologe romain au 6mai. Déclaré Docteur de l’Église par Léon XIII en 1890,

fête inscrite alors au calendrier sous le rite double à la date du 27 mars.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Jean, surnommé Damascène du nom de sa patrie, était de

naissance illustre, et fut instruit dans les lettres divines et humaines par te

moine Cosme de Constantinople. Comme en ce temps, l’empereur Léon l’Isaurien

avait déclaré une guerre impie au culte des saintes images, Jean, sur

l’invitation du Pontife romain Grégoire III, défendit avec ardeur par sa parole

et ses écrits la sainteté de ce culte. Ce zèle suscita contre lui les haines de

l’empereur à ce point que celui-ci, par l’artifice de fausses lettres, le fit

accuser de trahison auprès du calife de Damas dont Jean était le conseiller et

le ministre. Le prince, trompé par cette fourberie, ordonna de couper la main

droite de Jean, qui protestait avec serment contre cette infâme calomnie. Mais la

Vierge bénie vint au secours de son fidèle serviteur, qui lui avait adressé de

ferventes prières, et vengea son innocence. Par un insigne bienfait de sa part,

la main qui avait été coupée lui fut rendue et si bien unie au bras qu’il ne

restait aucune trace de la séparation. Profondément touché de ce miracle, Jean

résolut d’accomplir le dessein qu’il avait conçu depuis longtemps. Ayant

obtenu, quoiqu’avec peine, son congé du calife, il distribua tous ses biens aux

pauvres et donna la liberté à ses esclaves. Il parcourut en pèlerin les lieux

saints de la Palestine et se retira enfin avec Cosme, son ancien maître, près

de Jérusalem, dans la laure de saint Sabbas, où il fut ordonné Prêtre.

Cinquième leçon. Dans la carrière de la vie religieuse, il donna aux autres

moines d’illustres exemples de toutes les vertus, particulièrement de

l’humilité et de l’obéissance. Il revendiquait comme son droit les emplois les

plus vils du monastère, et s’y appliquait avec ardeur. Ayant eu l’ordre d’aller

vendre de petites corbeilles à Damas, la ville où naguère il avait reçu les

plus grands honneurs, il y recueillait avec une- sainte avidité les dérisions

et les moqueries de la multitude. Il pratiquait si bien l’obéissance que, non

seulement il se rendait au moindre signe des supérieurs mais encore qu’il ne se

crut jamais permis de rechercher les motifs des ordres qu’il recevait, quelque

difficiles et insolites qu’ils parussent être. Au milieu des exercices de ces

vertus, il ne cessa jamais de défendre avec zèle le dogme catholique du culte

des saintes images. Aussi fut-il en butte à la haine et aux vexations de

Constantin Copronyme, comme il l’avait été auparavant à celles de l’empereur

Léon ; d’autant plus qu’il reprenait avec liberté l’arrogance de ces empereurs,

assez hardis pour traiter des choses de la foi et prononcer à leur gré sur ces

matières.

Sixième leçon. On ne peut voir sans étonnement le grand nombre des écrits en

prose et en vers que Jean Damascène a composés pour la défense de la foi et

l’augmentation de la piété, digne assurément des éloges que le deuxième concile

de Nicée lui a décernés et du surnom de Chrysorrhoas, c’est-à-dire de fleuve

d’or, qui lui fut donné à cause de son éloquence. Non seulement il défendit la

foi orthodoxe contre les Iconoclastes, mais il combattit avec zèle presque tous

les hérétiques, principalement les Acéphales, les Monothélites, les

Patripassiens. Il revendiqua les droits et la puissance de l’Église ; il

affirma hautement la primauté du prince des Apôtres ; il le nomma le soutien des

Églises, la pierre qui ne peut être brisée, le docteur et l’arbitre de

l’univers. Tous ses écrits se distinguent non seulement par la science et la

doctrine, mais encore respirent un profond sentiment de piété, surtout

lorsqu’il adresse ses louanges à la Mère de Dieu, à laquelle il rendait un

culte et un amour singuliers. Mais ce qui fait son plus grand mérite, c’est

qu’il fut le premier à embrasser dans un ordre suivi toute la théologie, et

qu’il ouvrit la voie à saint Thomas pour exposer ainsi méthodiquement la

doctrine sacrée. Enfin cet homme très saint, rempli de mérites, et dans un âge

avancé, s’endormit dans la paix du Christ vers l’an sept cent cinquante-quatre.

Le souverain Pontife Léon XIII a concédé à l’Église universelle l’Office et la

Messe de saint Jean Damascène avec l’addition du titre de Docteur.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Luc. Cap. 6, 6-11.

En ce temps-là : Il arriva un autre jour de Sabbat, que Jésus entra dans la

synagogue et qu’il y enseignait ; or, il y avait là un homme dont la main

droite était desséchée. Et le reste.

Homélie de S. Pierre Chrysologue.

Septième leçon. Cet homme est l’image de tous les hommes, sa guérison est celle

de tous.- En lui la santé si longtemps attendue est rendue au genre humain.

Cette main desséchée l’était plus par la paralysie de la foi, que par

l’atrophie des nerfs, par le péché de l’âme plus que par l’affaiblissement de

la chair. Cette maladie était très ancienne et remontait aux premiers jours du

monde. Contractée par un châtiment divin, elle ne pouvait être guérie par l’art

ou les soins de l’homme. L’homme avait touché à ce qui lui était interdit, il

avait franchi les bornes posées à sa liberté, en portant la main sur l’arbre de

la science du bien et du mal. Il avait besoin, non d’une main qui lui appliquât

un remède corporel, mais d’un Maître qui pût révoquer la sentence portée contre

lui et délier par son pardon ce qu’il avait lié par sa juste colère.

Huitième leçon. En cet homme était seulement la - figure de notre guérison,

mais c’est dans le Christ que la santé parfaite nous est réservée ; notre main

déplorablement desséchée reprend sa force, quand elle est arrosée du sang du

Seigneur dans sa passion, quand elle est étendue sur le bois vivifiant de la

Croix, quand elle recueille dans la douleur la vertu fructifiant en bonnes

œuvres, quand elle embrasse tout l’arbre du salut, quand, attaché à ce bois par

les clous du Seigneur, le corps ne peut plus revenir à l’arbre de la

concupiscence et des voluptés qui l’ont desséché. « Et Jésus dit à l’homme qui

avait la main desséchée : Lève-toi au milieu de l’assemblée », protestant de ta

propre faiblesse, tirant ton salut de la pitié de Dieu, attestant sa puissance,

rendant manifeste l’incrédulité des Juifs ; lève-toi dans l’assemblée, et

qu’insensibles à de si grands miracles, endurcis devant une guérison si

merveilleuse, ils se laissent du moins saisir et fléchir au sentiment de pitié

qu’inspiré une faiblesse si déplorable.

Neuvième leçon. Il dit à l’homme : « Étends ta main, et il retendit, et sa main

redevint saine ». Étends ta main : l’ordre divin la délie, comme l’ordre divin

l’avait liée. Étends ta main : le châtiment cède à la voix du Juste ; la

créature entend la voix de Dieu, et le Créateur se trahit à son pardon. Priez,

mes frères, que le mal d’une telle faiblesse n’atteigne que la synagogue ;

qu’il n’y ait point dans l’Église d’homme dont la main soit desséchée par la

cupidité, contractée par l’avarice, affaiblie par la rapine, malade et

resserrée par l’attachement aux richesses ; mais s’il est quelqu’un que ce

malheur atteigne, qu’il entende la voix du Seigneur, et qu’aussitôt il étende

la main dans les œuvres de la piété, qu’il en détende les nerfs endurcis dans

la douceur de la miséricorde, qu’il l’ouvre pour répandre l’aumône. Il ne sait

trouver le remède, celui qui ne sait donner aux pauvres pour le profit de son

âme.

Saint

Jean Dammascène en la vie de Saint Barlaam nous représente par cette figure la

dangereuse vie des mondains…, gravure

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

On n’a point oublié que les Grecs célèbrent au premier dimanche de Carême une

de leurs plus grandes solennités : la fête de l’Orthodoxie. La nouvelle Rome,

montrant bien qu’elle ne partageait aucunement l’indéfectibilité de l’ancienne,

avait parcouru tout le cycle des hérésies concernant le dogme du Dieu fait

chair. Après avoir rejeté successivement la consubstantialité du Verbe, l’unité

de personne en l’Homme-Dieu, l’intégrité de sa double nature, il semblait

qu’aucune négation n’eût échappé à la sagacité de ses empereurs et de ses

patriarches. Un complément pourtant des erreurs passées manquait encore au

trésor doctrinal de Byzance.

Il restait à proscrire ici-bas les images de ce Christ qu’on ne parvenait pas à

diminuer sur son trône du ciel ; en attendant qu’impuissante à l’atteindre même

dans ces représentations figurées, l’hérésie laissât la place au schisme pour arriver

à secouer du moins le joug de son Vicaire en terre : dernier reniement, qui

achèvera de creuser pour Constantinople la tombe que le Croissant doit sceller

un jour.

L’hérésie des Iconoclastes ou briseurs d’images marquant donc, sur le terrain

de la foi au Fils de Dieu, la dernière évolution des erreurs orientales, il

était juste que la fête destinée à rappeler le rétablissement de ces images

saintes s’honorât, en effet, du glorieux nom de fête de l’Orthodoxie ; car en

célébrant le dernier des coups portés au dogmatisme byzantin, elle rappelle

tous ceux qu’il reçut dans les Conciles, depuis le premier de Nicée jusqu’au

deuxième du même nom, septième œcuménique. Aussi était-ce une particularité de

ladite solennité, qu’en présence de la croix et des images exaltées dans une

pompe triomphale, l’empereur lui-même se tenant debout à son trône, on

renouvelât à Sainte-Sophie tous les anathèmes formulés en divers temps contre

les adversaires de la vérité révélée.

Satan, du reste, l’ennemi du Verbe, avait bien montré qu’après toutes ses

défaites antérieures, il voyait dans la doctrine iconoclaste son dernier

rempart. Il n’est pas d’hérésie qui ait multiplié à ce point en Orient les

martyrs et les ruines. Pour la défendre, Néron et Dioclétien semblèrent revivre

dans les césars baptisés Léon l’Isaurien, Constantin Copronyme, Léon

l’Arménien, Michel le Bègue et son fils Théophile. Les édits de persécution,

publiés pour protéger les idoles autrefois, reparurent pour en finir avec

l’idolâtrie dont l’Église, disait-on, restait souillée.

Vainement, dès l’abord, saint Germain de Constantinople rappela-t-il au

théologien couronné sorti des pâturages de l’Isaurie, que les chrétiens

n’adorent pas les images, mais les honorent d’un culte relatif se rapportant à

la personne des Saints qu’elles représentent. L’exil du patriarche fut la

réponse du césar pontife. La soldatesque, chargée d’exécuter les volontés du

prince, se rua au pillage des églises et des maisons des particuliers. De

toutes parts, les statues vénérées tombèrent sous le marteau des démolisseurs.

On recouvrit de chaux les fresques murales ; on lacéra, on mit en pièces les

vêtements sacrés, les vases de l’autel, pour en faire disparaître les émaux

historiés, les broderies imagées. Tandis que le bûcher des places publiques

consumait les chefs-d’œuvre dans la contemplation desquels la piété des peuples

s’était nourrie, l’artiste assez osé pour continuer de reproduire les traits du

Seigneur, de Marie ou des Saints, passait lui-même par le feu et toutes les

tortures, en compagnie des fidèles dont le crime était de ne pas retenir

l’expression de leurs sentiments à la vue de telles destructions. Bientôt,

hélas ! dans le bercail désolé, la terreur régna en maîtresse ; courbant la

tête sous l’ouragan, les chefs du troupeau se prêtèrent à de lamentables

compromissions.

C’est alors qu’on vit la noble lignée de saint Basile, moines et vierges

consacrées, se levant tout entière, tenir tête aux tyrans. Au prix de l’exil,

de l’horreur des cachots, de la mort par la faim, sous le fouet, dans les

flots, de l’extermination par le glaive, ce fut elle qui sauva les traditions

de l’art antique et la foi des aïeux. Vraiment apparut-elle, à cette heure de

l’histoire, personnifiée dans ce saint moine et peintre du nom de Lazare qui,

tenté par flatterie et menaces, puis torturé, mis aux fers, et enfin,

récidiviste sublime, les mains brûlées par des lames ardentes, n’en continua

pas moins, pour l’amour des Saints, pour ses frères et pour Dieu, d’exercer son

art, et survécut aux persécuteurs.

Alors aussi s’affirma définitivement l’indépendance temporelle des Pontifes

romains, lorsque l’Isaurien menaçant de venir jusque dans Rome briser la statue

de saint Pierre, l’Italie s’arma pour interdire ses rivages aux barbares

nouveaux, défendre les trésors de ses basiliques, et soustraire le Vicaire de

l’Homme-Dieu au reste de suzeraineté que Byzance s’attribuait encore.

Glorieuse période de cent vingt années, comprenant la suite des grands Papes

qui s’étend de saint Grégoire II à saint Paschal Ier, et dont les deux points

extrêmes sont illustrés en Orient par les noms de Théodore Studite, préparant

dans son indomptable fermeté le triomphe final, de Jean Damascène qui, au

début, signifia l’orage. Jusqu’à nos temps, il était à regretter qu’une époque

dont les souvenirs saints remplissent les fastes liturgiques des Grecs, ne fût

représentée par aucune fête au calendrier des Églises latines. Sous le règne du

Souverain Pontife Léon XIII, cette lacune a été comblée ; depuis l’année 1892,

Jean Damascène, l’ancien visir, le protégé de Marie, le moine à qui sa doctrine

éminente valut le nom de fleuve d’or, rappelle au cycle de l’Occident

l’héroïque lutte où l’Orient mérita magnifiquement de l’Église et du monde.

La notice liturgique consacrée à l’illustre Docteur est assez complète pour

nous dispenser d’y rien ajouter. Mais il convient de conclure en donnant ici

les traits principaux des définitions parles quelles, au VIIIe siècle et plus

tard au XVIe, l’Église vengea les saintes Images de la proscription à laquelle

les avait condamnées l’enfer. « C’est légitimement, déclare le deuxième concile

de Nicée, qu’on place dans les églises, en fresques, en tableaux, sur les

vêtements, les vases sacrés, comme dans les maisons ou dans les rues, les

images soit de couleur, soit de mosaïque ou d’autre matière convenable,

représentant notre Seigneur et Sauveur Jésus-Christ, notre très pure Dame la

sainte Mère de Dieu, les Anges et tous les Saints ; de telle sorte qu’il soit

permis de faire fumer l’encens devant elles et de les entourer de lumières [1].

— Non, sans doute, reprennent contre les Protestants les Pères de Trente, qu’on

doive croire qu’elles renferment une divinité ou une vertu propre, ou que l’on

doive pincer sa confiance dans l’image même comme autrefois les païens dans

leurs idoles ; mais, l’honneur qui leur est rendu se référant au prototype [2],

c’est le Christ à qui vont par elles nos adorations, ce sont les Saints que

nous vénérons dans les traits qu’elles nous retracent d’eux [3]. »

Vengeur des saintes Images, obtenez-nous, comme le demande l’Église [4],

d’imiter les vertus, d’éprouver l’appui de ceux qu’elles représentent. L’image

attire notre vénération et notre prière à qui en mérite l’hommage : au Christ

roi, aux princes de sa milice, aux plus vaillants de ses soldats, qui sont les

Saints ; car c’est justice qu’en tout triomphe, le roi partage avec son armée

ses honneurs [5]. L’image est le livre de ceux qui ne savent pas lire ; souvent

les lettrés mêmes profitent plus dans la vue rapide d’un tableau éloquent,

qu’ils ne feraient dans la lecture prolongée de nombreux volumes [6]. L’artiste

chrétien, dans ses travaux, fait acte en même temps de religion et d’apostolat

; aussi ne doit-on pas s’étonner des soulèvements qu’à toutes les époques

troublées la haine de l’enfer suscite pour détruire ses œuvres. Avec vous, qui

compreniez si bien le motif de cette haine, nous dirons donc :

« Arrière, Satan et ton envie, qui ne peut souffrir de nous laisser voir

l’image de notre Seigneur et nous sanctifier dans cette vue ; tu ne veux pas

que nous contemplions ses souffrances salutaires, que nous admirions sa

condescendance, que nous ayons le spectacle de ses miracles pour en prendre

occasion de connaître et de louer la puissance de sa divinité. Envieux des

Saints et des honneurs qu’ils tiennent de Dieu, tu ne veux pas que nous ayons

sous les yeux leur gloire, de crainte que cette vue ne nous excite à imiter

leur courage et leur foi ; tu ne supportes pas le secours qui provient à nos

corps et à nos âmes de la confiance que nous mettons en eux. Nous ne te

suivrons point, démon jaloux, ennemi des hommes [7]. »

Soyez bien plutôt notre guide, ô vous que la science sacrée salue comme un de

ses premiers ordonnateurs. Connaître, disiez-vous, est de tous les biens le

plus précieux [8]. Et vous ambitionnez toujours d’amener les intelligences au

seul maître exempt de mensonge, au Christ, force et sagesse de Dieu : pour

qu’écoutant sa voix dans l’Écriture, elles aient la vraie science de toutes

choses ; pour qu’excluant toutes ténèbres du cœur comme de l’esprit, elles ne

s’arrêtent point à la porte extérieure de la vérité, mais parviennent à

l’intérieur de la chambre nuptiale [9].

Un jour, ô Jean, Marie elle-même prédit ce que seraient votre doctrine et vos

œuvres ; apparaissant à ce guide de vos premiers pas monastiques auquel vous

obéissiez comme à Dieu, elle lui dit : « Permets que la source coule, la source

aux eaux limpides et suaves, dont l’abondance parcourra l’univers, dont

l’excellence désaltérera les âmes avides de science et de pureté, dont la

puissance refoulera les flots de l’hérésie et les changera en merveilleuse

douceur. » Et la souveraine des célestes harmonies ajoutait que vous aviez

aussi reçu la cithare prophétique et le psaltérion, pour chanter des cantiques

nouveaux au Seigneur notre Dieu, des hymnes émules de ceux des Chérubins [10].

Car les filles de Jérusalem, qui sont les Églises chantant la mort du Christ et

sa résurrection [11], devaient avoir en vous l’un de leurs chefs de chœurs. Des

fêtes de l’exil, de la Pâque du temps, conduisez-nous par la mer Rouge et le

désert à la fête éternelle, où toute image d’ici-bas s’efface devant les

réalités des cieux, où toute science s’évanouit dans la claire vision, où

préside Marie, votre inspiratrice aimée, votre reine et la nôtre.

[1] Concil. Nic. Il, sess. VII.

[2] Cette formule, où se trouve exprimée la vraie base théologique du culte des

images, est empruntée par le concile de Trente au second de Nicée, qui lui-même

l’a tirée textuellement de saint Jean Damascène : De fide orthodoxa, IV, XVI.

[3] Concil. Trident., sess. XXV.

[4] Collecte de la Messe.

[5] Damasc. De Imaginibus, I, 19-21.

[6] Ibid. Comment, in Basil.

[7] De Imaginibus, III, 3.

[8] Dialectica, I.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Joan. Hierosolymit. Vita J. Damasceni, XXXI.

[11] Ibid.

170

St John, Damascus Syria 1966

Bhx Cardinal Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Cette fête fut introduite dans la liturgie romaine en 1890 et coïncide avec

cette première période du pontificat de Léon XIII où la question d’Orient lui

fut si chère. Si les efforts du Pape n’eurent pas tout le succès qu’on pouvait

espérer, ce ne fut certes pas faute de zèle de la part de l’Église catholique

qui alors, comme toujours d’ailleurs, ouvrit ses bras maternels pour accueillir

ses filles déshéritées d’Orient, affaiblies par un schisme déjà presque

millénaire, et avilies en outre par leur servitude sous le Croissant.