Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682), La Trinité,1681, huile sur toile , 293 x 207, National Gallery, Londres

SYMBOLE

DES APÔTRES

Je

crois en Dieu le Père tout-puissant,

Créateur

du ciel et de la terre,

Et

en Jésus-Christ son Fils unique Notre-Seigneur,

Qui

a été conçu du Saint-Esprit,

est

né de la Vierge Marie,

A

souffert sous Ponce Pilate,

a

été crucifié, est mort et a été enseveli,

Est

descendu aux enfers,

le

troisième jour est ressuscité d’entre les morts,

Est

monté aux cieux, Est assis à la droite de Dieu le Père tout-puissant,

D’où

il viendra juger les vivants et les morts.

Je

crois au Saint-Esprit,

la

sainte Eglise catholique,

la

communion des saints,

la

rémission des péchés,

la

résurrection de la chair,

la

vie éternelle.

Amen.

CREDO

- SYMBOLE DE NICÉE-CONSTANTINOPLE

Je

crois en un seul Dieu, le Père tout-puissant,

Créateur

du ciel et de la terre,

de

l’univers visible et invisible.

Je

crois en un seul Seigneur,

Jésus

Christ, le Fils unique de Dieu,

né

du Père avant tous les siècles :

Il

est Dieu, né de Dieu, lumière, née de la lumière,

vrai

Dieu, né du vrai Dieu,

engendré,

non pas créé, consubstantiel au Père,

et

par lui tout a été fait.

Pour

nous les hommes, et pour notre salut,

il

descendit du ciel ;

par

l’Esprit Saint,

il

a pris chair de la Vierge Marie,

et

s’est fait homme.

Crucifié

pour nous sous Ponce Pilate,

il

souffrit sa passion et fut mis au tombeau.

Il

ressuscita le troisème jour,

comformément

aux Ecritures,

et

il monta au ciel ;

il

est assis à la droite du Père.

Il

reviendra dans la gloire,

pour

juger les vivants et les morts ;

et

son règne n’aura pas de fin.

Je

crois en l’Esprit Saint,

qui

est Seigneur et qui donne la vie ;

il

procède du Père et du Fils ;

avec

le Père et le Fils,

il

reçoit même adoration et même gloire ;

il

a parlé par les prophètes.

Je

crois en l’Eglise,

une,

sainte, catholique et apostolique.

Je

reconnais un seul baptême pour le pardon des péchés.

J’attends

la résurrection des morts

et

la vie du monde à venir.

Amen.

Bartolo di Fredi (1330–1410) Le

retable de la Trinité. 1397, Quatre panneaux, 317 x 217), Tempera sur

bois : La Sainte Trinité (160 x 228) ; La Visitation (156 x

112) ; Saint Dominique (156 x 56) ; Saint Christophe (156 x

56), musée des Beaux-Arts de Chambéry

Altarpiece

of the Trinity (upper panel). The upper panel, depicting the Holy Trinity,

of an altarpiece made up of four tableaux. The other

three tableaux depict the Visitation (lower centre panel), Saint

Dominic (lower left panel), and Saint Christopher (lower right panel).

Fête

de la Sainte Trinité

Année

A

Première

lecture

Lecture du livre de

l'Exode (XXXIV 4b-6 & 8-9)[1]

Moïse se leva de bon

matin, et il gravit la montagne du Sinaï comme le Seigneur le lui avait

ordonné. Le Seigneur descendit dans la nuée et vint se placer auprès de Moïse.

Il proclama lui-même son nom ; il passa devant Moïse et proclama :

« Je suis Yahvé, le Seigneur, le Dieu tendre et miséricordieux, lent à la

colère, plein d'amour et de fidélité. » Aussitôt Moïse se prosterna

jusqu'à terre, et il dit : « S'il est vrai, Seigneur, que j'ai trouvé

grâce devant toi, daigne marcher au milieu de nous. Oui, c'est un peuple à la

tête dure ; mais tu pardonneras nos fautes et nos péchés, et tu feras de

nous un peuple qui t'appartienne. »

Textes liturgiques ©

AELF, Paris

[1] Moïse

est convoqué par Dieu sur la montagne pour y recevoir la charte de l'Alliance.

Le Seigneur descend : la nuée qui lui sert de véhicule, manifeste surtout

le clair-obscur de la présence divine. Dieu s'approche de Moïse, il passe même

devant lui. Le narrateur ne dit pas que Moise voit Dieu, car « l’homme ne

peut voir Dieu et vivre »; tout au plus, voit-il son dos « car sa

face il ne peut la voir » (XXXIII 20-23). Dieu ne proclame plus son nom

pour se faire connaître, comme à la première rencontre (III 13), mais pour se

faire reconnaître par Moïse. Cette proclamation contient le nom propre de Dieu

(Yahvé) révélé en III 14, mais aussi des qualificatifs qui le définissent et

justifient son intervention présente. Tendresse et miséricorde, grâce et

fidélité en disent, en termes presque synonymes, l’essentiel : le

vocabulaire de l'amour humain, transposé en Dieu, dévoile l'insondable richesse

de l'amour qui est en Dieu comme en sa source. Quant à la colère, elle existe

en Dieu, de même que sa jalousie (XX 5), car il ne peut tolérer le mal, pèse

moins dans la balance que la miséricorde : car si Dieu châtie jusqu'à la

troisième et quatrième génération, il fait grâce jusqu'à la millième (verset 7,

ici omis). A cette présentation de Dieu, Moïse répond par un geste de foi, la

prosternation ; et par une prière suppliante: puisque Dieu a daigné le

choisir comme médiateur, que Dieu prenne à nouveau la tête de son peuple, qu'il

lui pardonne ses égarements et qu'il fasse alliance à nouveau avec lui. A cette

requête, Dieu va redonner au peuple ses promesses et ses commandements, le

Décalogue.

Cantique (Dn

3, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56)

R/ À toi, louange et

gloire éternellement ! (Dn 3, 52)

Béni sois-tu, Seigneur, Dieu

de nos pères,

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Béni soit ton nom de

gloire et de sainteté,

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Béni sois-tu au temple

saint de ta gloire,

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Béni sois-tu sur le trône

de ton règne

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Béni sois-tu qui siège

au-dessus des Chérubins,

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Béni sois-tu dans le

ciel, au firmament,

R/ A toi louange et

gloire éternellement !

Textes liturgiques ©

AELF, Paris

Épître

Lecture de la lettre

de saint Paul Apôtre aux Corinthiens (XIII 11-13)[1]

Frères, soyez dans la

joie, cherchez la perfection, encouragez-vous, soyez d'accord entre vous, vivez

en paix, et le Dieu d'amour et de paix sera avec vous. Exprimez votre amitié en

échangeant le baiser de paix. Tous les fidèles vous disent leur amitié. Que la grâce

du Seigneur Jésus Christ, l'amour de Dieu et la communion de l'Esprit Saint

soient avec vous tous.

Textes liturgiques ©

AELF, Paris

[1]C'est

ici la conclusion de la deuxième épître de saint Paul à l’Eglise de Corinthe

dont tout le monde sait aujourd'hui les dissensions et les contestations ;

aussi, ces petites phrases, en conclusion de larges développements, résument

ce que saint Paul souhaite à ces chrétiens qu'il aime mais qui lui donnent tant

de soucis et le font tant souffrir. Rien ne fait plus souffrir un pasteur que

de présider à une communauté agitée de contestations et divisée de toutes

sortes d'inimitiés sordidement entretenues. Saint Paul leur souhaite la joie,

fruit de la foi en Jésus ressuscité : « réjouissez-vous dans le

Seigneur » (Philippiens, III 1 & IV 4). La joie, signe distinctif des

chrétiens dans un monde perturbé. Il leur souhaite aussi la recherche de la

perfection, non à la manière stoïcienne, mais l'aboutissement,

l’accomplissement dans une vie de fidélité du germe de sainteté déposé par Dieu

en chacun par le baptême : « voilà le but de nos prières: votre

perfectionnement » (II Corinthiens, XIII 9). L'encouragement est le

mot qui sert à désigner le « Paraclet » ; il comporte le soutien

mutuel, l’exhortation, l’émulation pour tenir dans l'épreuve et marcher vers

le but, et aussi la consolation (II Corinthiens, I 3-7). La concorde et la

paix, dans l’acceptation des diversités normales mais dans une soumission

commune à l'unique vérité : pas seulement dans le cœur, mais dans la

pensée. Le baiser de paix, dans l'assemblée liturgique, en sera le signe. La

salutation finale est l'amplification trinitaire du.salut biblique « Le Seigneur

soit avec vous ». Jésus est nommé le premier, car il est appelé le Seigneur,

et son attribut est la grâce, c'est-à-dire le don gratuit de sa vie qu'il fait

à ses disciples. A Dieu (le Père) revient l’agapé, l’amour dont il est la

source. A l’Esprit Saint est attribuée la mission de réaliser entre les fidèles

la communion, de même qu'il est entre le Père et le Fils le lien d'unité.

Évangile

Suite du saint

Évangile de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ selon Saint Jean (III, 16-18).

Dieu a tant aimé le monde

qu'il a donné son Fils unique[1] :

ainsi tout homme qui croit en lui ne périra pas, mais il obtiendra la vie

éternelle[2].

Car Dieu a envoyé son Fils dans le monde, non pas pour condamner le monde, mais

pour que, par lui, le monde soit sauvé. Celui qui croit en lui échappe au

jugement, celui qui ne veut pas croire est déjà condamné, parce qu'il n'a pas

cru au nom du Fils unique de Dieu[3].

Textes liturgiques ©

AELF, Paris

[1] L'amour

se mesure par ses dons ; l'amour de Dieu a été jusqu'au don de son Fils, de son

propre Fils, de son Fils unique (saint Hilaire de Poitiers :

« De Trinitate », VI).

Il a donné non un

serviteur, ni un ange, il a donné son Fils. Aussi Jésus ne dit-il plus ici le

Fils de l'homme, mais le Fils unique de Dieu (saint Jean

Chrysostome : homélie XXVII sur l'évangile selon saint Jean).

Dieu entre avec l'homme

dans un magnifique combat de générosité : Abraham lui offre son fils et Dieu

doit lui-même arracher ce fils à la mort ; mais Dieu donnant son Fils aux

hommes, ce Fils qui était immortel par nature, le livre pour eux à la mort. Que

dirons-nous à ces choses ? (Origène : homélie VIII sur la Genèse).

[2] Toutefois

il ne faut pas que devant cette révélation de l'amour du Sauveur, la

présomption et l'audace au péché naissent dans le coeur de l'homme. Il y a deux

avènements du Christ, l'un où il viendra juger et où il jugera chacun selon ses

oeuvres ; et plus les miséricordes auront été grandes et plus sévère sera la

justice ; et il y a un autre avènement, le premier, où il vient non pour

examiner nos fautes, mais pour les pardonner (saint Jean

Chrysostome : homélie XXVIII sur l'évangile selon saint Jean).

[3] Vous

ne voulez pas être sauvé, vous serez jugé par vous-même. Que dis-je, vous serez

jugé ? le Sauveur a dit : il est jugé. Le jugement n'a pas été manifesté,

mais il est déjà fait. Le Seigneur connaît ceux qui sont à lui : il connaît

ceux qui sont réservés pour la couronne, et ceux qui sont réservés pour le feu

; il connaît dans son aire le froment et la paille, le bon grain et

l'ivraie. Celui qui ne croit pas est déjà jugé, parce qu'il ne croit pas

aun nom du Fils unique de Dieu (saint Augustin : Tractatus in

Johannis evangelium, XII 12).

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Annee_A/paques/trinite.html

Llanbeblig

Hours (f. 4v.) God, The Holy Spirit, and Christ Crucified, circa 1390, Ink

and Illuminations on parchment, 17.5 x 12.1, bibliothèque nationale du

pays de Galles, 'Aberystwyth, comté de Ceredigion.

Fête de la Sainte Trinité

Année B

Première lecture

Lecture du livre du Deutéronome (IV

32-34 ; 39-40)[1]

Moïse disait au peuple d'Israël : « Interroge

les temps anciens qui t'ont précédé, depuis le jour où Dieu créa l'homme sur la

terre : d'un bout du monde à l'autre, est-il arrivé quelque chose d'aussi

grand, a-t-on jamais connu rien de pareil ? Est-il un peuple qui ait

entendu comme toi la voix de Dieu parlant du milieu de la flamme, et qui soit

resté en vie ? Est-il un Dieu qui ait entrepris de se choisir une nation,

de venir la prendre au milieu d'une autre, à travers des épreuves, des signes,

des prodiges et des combats, par la force de sa main et la vigueur de son bras,

et par des exploits terrifiants - comme tu as vu le Seigneur ton Dieu, le

faire pour toi en Égypte ?

Sache donc aujourd'hui, et médite cela dans ton

cœur : le Seigneur est Dieu, là-haut dans le ciel comme ici-bas sur la

terre, et il n'y en a pas d'autre. Tu garderas tous les jours les commandements

et les ordres du Seigneur que je te donne aujourd'hui, afin d'avoir, toi et tes

fils, bonheur et longue vie sur la terre que te donne le Seigneur ton Dieu. »

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

[1] Sous

le mode exhortatif (« Reconnais-le aujourd'hui »), à l'aide de

questions (« Est-il rien d'arrivé d'aussi grand ? ») et à grand

renforts d'images (« Par sa main forte et son bras étendu »), le

Deutéronome veut exprimer la grandeur et l'unicité de Dieu. Israël a d'abord

reconnu l'action de Dieu dans l'événement fondateur de la libération d’Egypte

qui est ici rappelée au verset 34 : « Est-ce qu'un Dieu a tenté de venir

prendre pour lui une nation au milieu d'une autre », et aux versets

37-38 : « Il t'a fait sortir d'Egypte. » Le thème est celui de

l'élection par Dieu de ce peuple, et l’amour de Dieu pour ce peuple est

fortement souligné. Cependant, la foi s'approfondissant, le peuple découvre

dans le Dieu libérateur et sauveur, le Créateur qui est à la source de l'humanité

et de toutes choses (verset 32) : « Depuis le jour où Dieu créa l'humanité

sur la terre. » A travers l'œuvre de la création et l'œuvre de libération,

de salut dans l'histoire, le peuple d'Israël est invité à reconnaître

Dieu : « C'est le Seigneur qui est Dieu, il n'y en a pas d'autre. »

Ce verset 39, déjà annoncé au verset 35, constitue le sommet de ce texte. Cette

reconnaissance du Dieu unique comme dans tout le Deutéronome entraîne une

attitude du cœur, le cœur désignant dans la Bible non seulement le lieu de la

vie affective, mais aussi le centre des choix décisifs, de la conscience

morale. Cette attitude du cœur se manifeste par des actes concrets :

garder les lois et les commandements, ceux-ci étant donnés par Dieu pour le

bonheur et l'épanouissement de l'homme.

Psaume 32

Oui, elle est droite, la parole du Seigneur ;

il est fidèle en tout ce qu'il fait.

Il aime le bon droit et la justice ;

la terre est remplie de son amour.

Le Seigneur a fait les cieux par sa parole,

l'univers, par le souffle de sa bouche.

Il parla, et ce qu'il dit exista ;

il commanda et ce qu'il dit survint.

Dieu veille sur ceux qui le craignent,

qui mettent leur espoir en son amour.

Nous attendons notre vie du Seigneur :

il est pour nous un appui, un bouclier.

La joie de notre cœur vient de lui,

notre confiance est dans son nom très saint.

Que ton amour, Seigneur, soit sur nous,

comme notre espoir est en toi !

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

Épître

Lecture de la première lettre de saint Paul

Apôtre aux Romains (VIII[1] (14-17).

Frères, tous ceux qui se laissent conduire par

l'Esprit de Dieu, ceux-là sont fils de Dieu. L'Esprit que vous avez reçu ne

fait pas de vous des esclaves, des gens qui ont encore peur ; c'est un

Esprit qui fait de vous des fils ; poussés par cet Esprit, nous crions

vers le Père en l'appelant : « Abba[2] ! »

C'est donc l'Esprit Saint lui-même qui affirme à notre esprit que nous sommes

enfants de Dieu. Puisque nous sommes ses enfants, nous sommes aussi ses

héritiers ; héritiers de Dieu, héritiers avec le Christ, à condition de

souffrir avec lui pour être avec lui dans la gloire.

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

[1] Dans

la sombre description du chapitre VII de cette épître, saint Paul a montré

l'humanité sous le pouvoir du péché ; dans le chapitre VIII, il décrit la

vie du chrétien qui se laisse conduire par le Saint-Esprit. Dans ce passage, on

remarque la répétition des mots « fils », « enfants »,

« héritiers » qui sont en relation avec les mots « esclaves »

et « peur. » Le Fils est en relation avec le Père, la vie du baptisé

est une vie relationnelle, une vie trinitaire, une vie de liberté. Par l'Esprit

qui habite en lui, le baptisé peut prier la prière du Fils et oser appeler Dieu

« Père », Abba. Cette révélation transforme l'image de Dieu

que nous nous faisons, elle chasse la peur et nous invite à entrer dans une

relation de confiance, une relation filiale. Cette relation ne suppose pas

l'évasion des réalités de ce monde, car Jésus a prononcé cette prière dans son agonie

à Gethsémani (évangile selon saint Marc, XIV 36). Le chrétien, pour

participer à cette prière du Fils unique, passe aussi par la souffrance et la

croix du Fils avant de participer à la gloire.

[2] « Abba »,

mot araméen que l’on traduit par Père, est une expression

respectueuse d’affection filiale que l’on pourrait traduire par Papa.

Évangile

Suite du saint Évangile de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ

selon Saint Matthieu (XXVIII 16-20).

Au temps de Pâques, les onze disciples s'en allèrent

en Galilée, à la montagne[1] où

Jésus leur avait ordonné de se rendre. Quand ils le virent, ils se

prosternèrent, mais certains eurent des doutes. Jésus s'approcha d'eux et leur

adressa ces paroles : « Tout pouvoir m'a été donné au ciel et sur la

terre[2].

Allez donc ! De toutes les nations faites des disciples[3],

baptisez-les au nom du Père, et du Fils, et du Saint-Esprit[4] ;

et apprenez-leur à garder tous les commandements que je vous ai donnés[5].

Et moi, je suis avec vous[6],

tous les jours jusqu'à la fin du monde[7]. »

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

[1] Il

veut nous apprendre que pas sa résurrection, il a revêtu d’une vertu céleste ce

corps qu’il a pris de la famille humaine, et qu’il est déjà au dessus de la

terre. Il veut avertir ses fidèles que, s’ils veulent contempler les grandeurs

de la Résurrection, ils doivent s’élever au dessus des pensées terrestres, et

n’avoir plus que le désir des choses d’en-haut (Raban Maur).

[2] Le

démon devait être vaincu par la justice plus encore que par la puissance (…) Car

il avait péché, par son amour excessif de la puissance, en attaquant la

justice ; et les hommes le suivent, quand négligeant ou haïssant la

justice, ils recherchent la puissance. Pour arracher l’homme à la puissance du

démon, Dieu voulut donc que le démon fût vaincu non par la puissance mais par

la justice (saint Augustin : « De Trinitate », XIII

17).

[3] « Faites

des disciples » : cette mission répond tout à fait à la place

importante que ce mot occupe dans tout le premier évangile. L'emploi de ce mot

après la résurrection de Jésus signifie que la condition du disciple décrite

dans l'évangile n'est pas réservée aux seuls compagnons de Jésus durant sa vie,

mais elle est la condition dans laquelle tout homme est invité à rentrer.

Devenir chrétien signifie devenir disciple.

[4] « Baptisez-les

au nom du Père, et du Fils, et du Saint-Esprit » : l'expression

« au nom de » indique que le baptisé se trouve mis en relation

étroite avec le Nom, c'est-à-dire avec les personnes mêmes du Père, du fils et

de l'Esprit. Cette expérience du Dieu trinité, l'Eglise du temps de saint

Matthieu la fait à travers la célébration du Christ ressuscité le premier jour

de la semaine, et à travers le sacrement du baptême.

[5] « Apprenez-leur

à garder tous les commandements que je vous ai donnés » : ce passage

signale l'importance, dans la communauté chrétienne, de la nécessité pour les

croyants de comprendre ce qu'ils croient, de la nécessité de l'intelligence de

la foi, une foi qui est vivante et agissante. Cet enseignement consiste à

rappeler les commandements du Seigneur, ceux qu'il a donnés dans le Sermon sur

la Montagne. Par ses commandements, Jésus accomplit en les dépassant les lois

de Moïse : « il a été dit... moi je vous dis. » (évangile selon

saint Matthieu, V 22 ss). Au commandement de l'amour sont suspendus la

loi et les prophètes, car pour Matthieu la véritable adoration de Dieu ne

consiste pas seulement à prononcer son nom du bout des lèvres, mais à faire sa

volonté (évangile selon saint Matthieu, VII 21).

[6] Il

s'en allait en tant qu'homme, et il demeurait en tant que Dieu. Ils allaient

être privés de cette présence qui est restreinte à un lieu particulier, mais il

devait demeurer avec eux par cette présence qui remplit le monde entier.

Devaient-ils se troubler quand il se dérobait à leurs yeux, mais sans

s'éloigner de leur cœur ? (saint Augustin : Tractatus in

Johannis evangelium, LXVIII 1).

[7] Comme

les apôtres à qui il parle en ce moment doivent mourir un jour, il promet donc

cette assistance à tous les fidèles qui doivent croire en eux, et qui formeront

un seul corps avec eux (saint Jean Chrysostome : homélie XC sur

l’évangile selon saint Matthieu, 2).

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Annee_B/paques/trinite.html

La

Trinité, Le Roman de la Rose, manuscript f. 138r, Illumination on

parchment, XIVe siècle, bibliothèque nationale du

pays de Galles, 'Aberystwyth, comté de Ceredigion

Fête de la Sainte Trinité

Année C

Première lecture

Lecture du livre des Proverbes (VIII 22-31)[1]

Ecoutez ce que déclare la Sagesse :

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

[1] Des

sages d’Israël ayant glané, dans les cultures et les civilisations, les paroles

de sagesse compatibles avec leur foi, composèrent le Livre des Proverbes.

L’originalité de ce passage qui présente Yahvé comme le véritable maître de

sagesse, tient en ce que la Sagesse y est une personne qui d'une certaine

manière remplace le roi et le prophète ; elle parle comme quelqu'un qui

partage l'intimité divine. Antérieure à la Création, elle est le premier enfant

de Dieu. Les créatures sont la manifestation de la présence de cette Sagesse de

Dieu personnifiée. Elle ne se contente pas de partager l'activité de Dieu dont

elle est la première née, elle partage la condition humaine et trouve ses

délices parmi les enfants des hommes qui sont le couronnement et l'achèvement

de la création. La Sagesse est la figure du Messie. Comme l’Ecclésiastique (XXIV

3-10), ce texte, exprime que la Parole, la Sagesse de Dieu, a planté sa tente

au milieu des hommes. Elle est déjà le Verbe. Comme le prologue de saint Jean (I

14), saint Luc avait déjà dit en parlant du Fils de l'homme :

« La sagesse de Dieu se révèle juste auprès de tous ses enfants »

(VII 34-35). On comprend ainsi le choix de ce passage des Proverbes en la fête

de la Sainte Trinité. La théologie de saint Paul souligne à quel point cette

Sagesse éclate dans la création : les hommes sont inexcusables de n'être

pas remontés du créé au Créateur (épître aux Romains, I 18-32). De la même

manière, l’hymne aux Colossiens développe jusqu'au bout ce qui est

contenu en germe dans les Proverbes : le Fils est « l’image du Dieu

invisible, Premier-né de toute créature, car en lui tout a été créé, dans les

cieux et sur la terre, les êtres visibles comme les invisibles: tout est créé

par lui et pour lui » (I 15-16).

Psaume 8

À voir ton ciel, ouvrage de tes doigts,

la lune et les étoiles que tu fixas,

qu'est-ce que l'homme pour que tu penses à lui,

le fils d'un homme, que tu en prennes souci ?

Tu l'as voulu un peu moindre qu'un dieu,

le couronnant de gloire et d'honneur.

tu l'établis sur les œuvres de tes mains,

tu mets toute chose à ses pieds.

Les troupeaux de bœufs et de brebis,

et même les bêtes sauvages,

les oiseaux du ciel et les poissons de la mer,

tout ce qui va son chemin dans les eaux.

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

Épître

Lecture de la lettre de saint Paul Apôtre aux

Romains (II 1-5) [1].

Frères, Dieu a fait de nous des justes par la

foi ; nous sommes ainsi en paix avec Dieu par notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ,

qui nous a donné, par la foi, l'accès au monde de la grâce dans lequel nous

sommes établis ; et notre orgueil à nous, c'est d'espérer avoir part à la

gloire de Dieu. Mais ce n'est pas tout : la détresse elle-même fait notre

orgueil, puisque la détresse, nous le savons, produit la persévérance ; la

persévérance produit la valeur éprouvée ; la valeur éprouvée produit

l'espérance ; et l'espérance ne trompe pas, puisque l'amour de Dieu a été

répandu dans nos cœurs par l'Esprit Saint qui nous a été donné[2].

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

[1] Ce

passage est un des plus anciens textes exprimant l'action commune du Père, du

Fils et de l'Esprit au cœur des hommes. Par le Christ les hommes sont en paix

avec Dieu qui fait d'eux des justes par la foi. Au milieu de la détresse,

malgré le péché, ils persévèrent et tiennent bon parce que l'Esprit répand dans

le fond de leur être l'amour de Dieu. Est en germe dans ce texte la théologie

des vertus théologales : la foi, l'espérance et la charité. La

participation à la gloire de Dieu, l’accès au monde de la grâce, la valeur

éprouvée, la persévérance peuvent être sources d'orgueil et de fierté parce

qu'elles sont l'œuvre du Père, de Jésus Christ et de l'Esprit : foi,

espérance, amour sont dons de Dieu. La vie spirituelle est partage de la vie

divine. La souffrance, les épreuves prennent un sens nouveau. Elles redonnent

énergie et espérance au chrétien qui avec sagesse y discerne le travail

d'enfantement d'un monde neuf (épître de saint Paul aux Romains, VIII 21),

Cette espérance authentique ne peut être déçue car l'amour de Dieu ne trompe

pas.

[2] L’espérance est

la vertu théologale par laquelle nous désirons comme notre bonheur le Royaume

des cieux et la vie étemelle, en mettant notre confiance dans les promesses du

Christ et en prenant appui, non sur nos forces, mais sur le secours de la grâce

du Saint-Esprit. « Gardons indéffectible la confession de l'espérance, car

celui qui a promis est fidèle » (Hébreux, X 23). « Cet Esprit, il l'a

répandu sur nous à profusion, par Jésus-Christ notre Sauveur, afin que,

justifiés par la grâce du Christ, nous obtenions en espérance l'héritage de la

vie éternelle » (Tite, III 6-7). La vertu d'espérance répond à

l'aspiration au bonheur placée par Dieu dans le cœur de tout homme ; elle

assume les espoirs qui inspirent les activités des hommes ; elle les

purifie pour les ordonner au Royaume des cieux ; elle protège du

découragement ; elle soutient en tout délaissement ; elle dilate le

cœur dans l'attente de la béatitude éternelle. L'élan de l'espérance préserve

de l'égoïsme et conduit au bonheur de la charité. L'espérance chrétienne

reprend et accomplit l'espérance du peuple élu qui trouve son origine et son

modèle dans l'espérance d'Abraham comblé en Isaac des promesses de Dieu et purifiée

par l’épreuve du sacrifice. « Espérant contre toute espérance, il crut et

devint ainsi père d’une multitude de peuples » (Romains, IV 18).

L'espérance chrétienne se déploie dès le début de la prédication de Jésus dans

l'annonce des béatitudes. Les Béatitudes élèvent notre espérance comme vers le

ciel la nouvelle Terre promise ; elles en tracent le chemin à travers les

épreuves qui attendent les disciples de Jésus. Mais par les mérites de

Jésus-Christ et de sa passion, Dieu nous garde dans « l'espérance qui ne

déçoit pas » (Romains, V 5). L'espérance est « l'ancre de l'âme »,

sûre et ferme, « qui pénétre... là où est entré pour nous, en

précurseur, Jésus » (Hébreux, VI 19-20). Elle est aussi une arme qui nous

protège dans le combat du salut : « Revêtons la cuirasse de la foi et

de la charité, avec le casque de l'espérance du salut » (I Timothée,

V 8). Elle nous procure la joie dans l'épreuve même : « Avec la joie

de l'espérance, constants dans la tribulations » (Romains, XII 12). Elle

s'exprime et se nourrit dans la prière, tout particulièrement dans celle

du Pater, résumé de tout ce que l'espérance nous fait désirer. (« Catéchisme

de l’Eglise universelle » : 3° partie, 1° section, chapitre I°,

article 7, II)

Évangile

Suite du saint Évangile de notre Seigneur

Jésus-Christ selon Saint Jean (XVI 12-15).

À l'heure où Jésus passait de ce monde à son Père, il

disait à ses disciples : « J'aurais encore beaucoup de choses à vous

dire, mais pour l'instant vous n'avez pas la force de les porter. Quand il

viendra, lui, l'Esprit de vérité, il vous guidera vers la vérité tout entière.

En effet, ce qu'il dira ne viendra pas de lui-même : il redira tout ce

qu'il aura entendu ; et ce qui va venir, il vous le fera connaître. Il me

glorifiera, car il reprendra ce qui vient de moi pour vous le faire connaître.

Tout ce qui appartient au Père est à moi ; voilà pourquoi je vous ai

dit : Il reprend ce qui vient de moi pour vous le faire connaître. »

Textes liturgiques © AELF, Paris

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Annee_C/paques/trinite.html

La Trinité

La façon la plus simple d'expliquer la Trinité est

de considérer qu'elle s'est développée à partir d'une question fondamentale :

Qui est Jésus Christ ? Juste un homme… Plus qu'un homme, moins qu'un dieu… Dieu

lui-même…? C'est cette dernière réponse qui a prévalu, mais elle a pris

beaucoup de temps à se formuler. Et à partir du moment où l'on conçoit que Jésus

est Dieu, alors comment penser sa relation au Père ? Comment interpréter

l'expérience de foi toujours renouvelée des communautés chrétiennes et la

fulgurante expansion de cette expérience aux premiers siècles de notre ère,

sinon que l'Esprit de Jésus était toujours vivant et que, même s'il est vrai

que pendant sa vie terrestre, il n'a jamais fondé de religion, il conduisait ce

qu'on appellera l'Église. La Trinité est donc la relation d'amour qui subsiste

entre le Père, le Fils et l'Esprit. Comme cet Esprit est celui de Jésus Christ,

c'est Lui qui nous fait entrer dans cet espace de communion des trois personnes

divines.

Yolande Girard, bibliste

SOURCE : http://www.interbible.org/interBible/source/lampe/2004/lampe_040416.htm

Le Greco. La Santísima Trinidad, 1577, 300 x 177, musée du Prado, Madrid. (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Trinit%C3%A9_(Le_Greco)

Augustin, Sermons 52

SERMON LII. LA

SAINTE TRINITÉ (1). (Ps 26,9 )

1. Mt 3,13

ANALYSE. - On venait de lire dans l'Évangile l'histoire du Baptême de

Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ. Saint Augustin saisit cette occasion, qu'il

regarde comme toute providentielle, pour démontrer comment les trois personnes

divines sont inséparables. Au Baptême du Sauveur on les croirait séparées; mais

en réalité elles sont inséparables dans toutes leurs opérations, comme

l'Écriture le prouve et comme on peut s'en faire une idée en interrogeant les

opérations de l'âme humaine. - 1. L'Écriture nous montre en effet que la

création et le gouvernement de l'univers sont dus au Père, au Fils et par

conséquent au Saint-Esprit. Si le Fils seul est né, si seul il a souffert, s'il

est seul ressuscité et monté aux cieux; sa naissance et sa passion, sa

résurrection et son ascension sont l'oeuvre de son Père comme la sienne. Ainsi

en est-il de ses miracles et de tout ce qu'il a fait. - 2. on peut se former

une idée de ce mystère en considérant, non pas la nature matérielle, mais l'âme

spirituelle de l'homme. N'y a-t-il pas dans cette âme trois facultés

distinctes: la mémoire, l'entendement et la volonté? Ces facultés sont

toutefois si inséparables dans leurs actes, qu'on ne peut nommer une seule

d'entre, elles sans le concours des trois ensemble. Saint Augustin proteste qu'il

ne veut pas établir ici de comparaison entre ces trois facultés et les trois

divines Personnes. Mais si la créature nous présente une telle simultanéité

d'action, pourquoi nous étonner de rencontrer ce phénomène dans la Trinité

créatrice?

1. La lecture de l'Évangile vient de nous faire connaître, en quelque sorte par

l'ordre du Seigneur, ou plutôt et véritablement par son ordre, de quel sujet

nous devons entretenir votre Charité. Mon coeur attendait de lui le mot

d'ordre; je sentais qu'il me commandait de parler de ce qu'il voudrait qu'on

récitât. Que votre zèle et votre piété se montrent donc attentifs; aidez auprès

du Seigneur notre Dieu le travail de mon esprit.

Voici sous nos yeux comme un divin spectacle; sur les rives du Jourdain notre

Dieu se révèle à nous dans sa Trinité sainte.

Jésus vient et il est baptisé par saint Jean; le Seigneur reçoit le baptême du

serviteur afin de nous donner un exemple d'humilité, car l'humilité est la

plénitude de la justice; lui-même l'a enseigné, quand à ces paroles de Jean:

«C'est moi qui dois être baptisé par vous, et c'est vous qui venez à moi!» il

répondit: «Laisse maintenant, afin d'accomplir toute justice.» Lors donc que

Jésus fut baptisé, les cieux s'ouvrirent, et l'Esprit-Saint descendit sur lui

en forme de colombe. On entendit ensuite cette voix d'en haut: «Celui-ci est

mon Fils bien-aimé, en qui j'ai mis mes affections.» Ne voyons-nous pas ici la

Trinité distinctement? Dans la voix nous entendons le Père, nous adorons le

Fils dans l'homme qui reçoit le baptême, et l'Esprit-Saint dans la colombe. Il

suffit de le rappeler; rien n'est plus facile à saisir. Quoi de plus évident?

Quoi de plus indubitable? C'est bien ici la Trinité. En effet, celui qui vient

vers Jean sous la forme de serviteur, Jésus-Christ Notre-Seigneur est sûrement

le Fils de Dieu; on ne peut dire qu'il soit ni le Père ni l'Esprit-Saint.

«Jésus vint, u dit le texte sacré; c'est sans aucun doute le Fils de Dieu. D'un

autre côté, qui peut hésiter à propos de la colombe? Qui peut demander ce qu'elle

est, quand l'Évangile dit expressément: «L'Esprit-Saint descendit sur lui en

forme de colombe?» On ne saurait douter non plus que la voix ne fût celle du

Père, puisqu'elle dit: «Vous êtes mon Fils (Mc 1,11).»

La Trinité est donc ici distincte.

2. J'ose même dire, en considérant espace, j'ose dire, quoique je le fasse en

tremblant, que cette auguste Trinité est en quelque sorte séparable. Jésus en

venant vers le fleuve se transportait d'un lieu dans un autre; la colombe en

descendant du ciel sur la terre allait aussi d'un lieu à l'autre; et la voix du

Père ne se faisait entendre ni de dessus la terre, ni du sein des eaux, mais du

haut du ciel. Il y a donc ici comme une triple séparation de lieux, de

fonctions et d'oeuvres.

Mais, me dira-t-on, montre plutôt que la Trinité est inséparable. Souviens-toi

que tu es catholique et que tu parles à des catholiques. Tel est en effet

l'enseignement de notre foi, c'est-à - 247 - dire de la foi véritable, de la

foi droite, de la foi catholique, de la foi qui ne repose pas sur les

présomptions de l'esprit mais sur les témoignages de l'autorité, de la foi qui

ne flotte pas incertaine au souffle téméraire des hérétiques, mais qui demeure

fortement établie sur la vérité apostolique. Voilà donc ce qu'elle nous fait

connaître, ce qu'elle nous donne à croire. Tant que la foi nous purifie encore,

nous ne voyons cette vérité ni des yeux du corps ni des yeux du coeur. Cette

même foi cependant nous assure avec une exactitude et une force incomparables

que le Père, le Fils et le Saint-Esprit forment une inséparable trinité, un

seul Dieu et non pas trois Dieux: un seul Dieu, sans que, toutefois, le Fils

soit le Père et sans que le Père soit le Fils, sans que le Saint-Esprit soit le

Père ou le Fils, car il est l'Esprit et du Père et du Fils. Cette ineffable

Divinité, cette Trinité ineffable, qui demeure en elle-même et qui néanmoins

renouvelle toutes choses; qui crée et répare, qui envoie et rappelle, qui juge et

absout, nous la savons non moins inséparable qu'elle est ineffable.

3. Mais quoi? Le Fils vient séparément avec son humanité; séparément

l'Esprit-Saint descend du ciel sous forme de colombe, et séparément encore la

voix du Père crie du haut du ciel: «Celui-ci est mon Fils bien-aimé.» Comment

donc la Trinité est-elle inséparable

Dieu vient par moi de vous rendre attentifs. Priez pour nous, conjurez-le, en

ouvrant votre coeur, de nous donner de quoi le remplir. Appliquons-nous

ensemble. Vous voyez quelle est notre entreprise; vous connaissez et ce que

nous projetons, et ce que nous sommes, de quoi nous voulons vous parler et où

nous sommes placé; placé hélas! dans ce corps qui se corrompt et appesantit

l'âme, dans cette maison de boue qui abat l'esprit, malgré tous ses efforts

pour s'élever (Sg

9,15). Je rappelle cet esprit répandu sur tant d'objets, je veux

l'appliquer au Dieu unique, à l'inséparable Trinité, pour chercher à vous en

parler, pour essayer de vous entretenir convenablement d'un si grand sujet;

mais pensez-vous que sous le lourd fardeau de ce corps je pourrai m'écrier:

«C'est vers vous, Seigneur, que j'ai élevé mon âme (Ps 75,4)?»

Ah! qu'il me vienne en aide et l'élève avec moi. Je suis trop faible et c'est

un poids trop lourd pour moi.

4. Les frères les plus studieux proposent souvent la question suivante, les

amis de la parole de Dieu se demandent souvent et souvent on frappe au coeur de

Dieu en disant: Le Père fait-il quelque chose sans le Fils et le Fils agit-il

quelquefois sans le Père? Restreignons-nous pour le moment au Père et au Fils,

et lorsque nous serons tirés de cette difficulté par Celui à qui nous disons:

«Soyez mon aide, ne me délaissez pas;» nous comprendrons que l'Esprit-Saint

agit toujours aussi avec le Fils et le Père. Appliquez donc, mes frères, votre

attention au Père et au Fils.

Le Père fait-il quelque chose sans le Fils? Nous répondons que non. En

doutez-vous? Mais que fait-il sans Celui par qui tout a été fait? «Tout, dit

l'Écriture, a été fait par lui.» Et pour ne rien laisser à désirer aux esprits

lourds, aux intelligences lentes et difficiles, elle ajoute: «Et sans lui rien

n'a été fait ( Jn 1,3)».

5. Mais quoi, mes frères, tout en voyant dans ces paroles: «Tout a été fait par

lui,» la preuve que le Père a fait par son Verbe, que Dieu a fait par sa Vertu

et par sa Sagesse toutes les créatures qui ont été faites par le Fils;

dirons-nous que tout a été fait par lui au moment de la création, mais que le

Père aujourd'hui ne fait plus tout par lui? Non: que cette pensée s'éloigne du

coeur des fidèles, qu'elle n'entre point dans l'esprit des hommes religieux,

dans l'entendement des âmes pieuses. On ne saurait admettre que Dieu ait créé

et ne gouverne point par son Fils. Comment ce qui a l'être serait-il dirigé

sans lui, puisque c'est lui qui a donné cet être? Mais recourons au témoignage

de l'Écriture. Elle enseigne, non-seulement que tout a été fait et créé par

lui, comme nous l'avons rappelé en citant ces paroles de l'Évangile. «Tout a

été fait par lui et sans lui rien n'a été fait;» mais encore que tout ce qu'il

a fait est régi et gouverné par lui. Le Christ, vous venez de le reconnaître,

est la Vertu de Dieu, la Sagesse de Dieu. Mais n'est-ce pas de la Sagesse qu'il

est dit: «Elle atteint avec force d'une extrémité à l'autre et dispose tout

avec douceur (Sg

8,1)?» Ainsi donc, gardons-nous d'en douter: Celui par qui tout a été fait,

gouverne également tout, et conséquemment le Père ne fait rien sans le Fils ni

le Fils sans le Père.

6. Ici se présente une question et nous entreprenons de la résoudre au nom du

Seigneur et par sa volonté. - Si le Père ne fait rien sans le Fils, ni le Fils

rien sans le Père, n'en devons- 248 - nous pas conclure que c'est le Père aussi

qui est né de la Vierge Marie, le Père qui a souffert sous Ponce-Pilate, le

Père qui est ressuscité et monté au ciel? - Non. Nous ne tenons pas ce langage,

parée qu'il n'est pas conforme à notre foi. «J'ai cru, est-il dit; c'est

pourquoi j'ai parlé; nous aussi nous croyons et c'est pourquoi nous parlons (2Co 4,13).»

Que nous dit la foi? Que le Fils, et non le Père, est né de la Vierge. Que

dit-elle encore? Que le Fils, et non le Père, a souffert et est mort sous

Ponce-Pilate.

J'oubliais de remarquer qu'il est des hommes, peu intelligents, connus sous le

nom de Patripassiens. Ils affirment que c'est le Père qui est né d'une femme et

qui a souffert, que le Fils n'est autre chose que le Père; deux noms, mais une

seule personne. Or pour les empêcher de séduire qui que ce soit, pour qu'ils ne

pussent contester que hors de son sein, l'Eglise catholique les a retranchés de

la communion des fidèles.

7. Rappelons maintenant à votre souvenir la difficulté de la question. Vous

avez avancé, peut-on me dire, que le Père ne fait rien saris le Fils, ni le

Fils sans le Père; vous avez cité l'Ecriture; le Père ne fait rien sans le

Fils, avez-vous dit, car c'est par le Fils que tout a été fait; et rien n'est

gouverné sans le Fils, car il est la Sagesse du Père, atteignant avec force

d'une extrémité à l'autre et disposant tout avec douceur. Mais n'êtes-vous pas

maintenant en contradiction avec vous-même? Le Fils, dites-vous, est né d'une

vierge, et non le Père; le Fils a souffert, le Fils est ressuscité, mais non le

Père. Ainsi le Fils fait quelque chose que ne fait pas le Père. De deux choses

l'une: avouez que le Fils agit quelquefois sans le Père, ou bien avouez que le

Père est né aussi, qu'il a souffert, qu'il est mort et qu'il est ressuscité. Il

n'y a point de milieu, il faut l'un ou l'autre: - Eh bien! je neveux ni l'un ni

l'autre. Je n'avouerai pas que le Fils fait quelque chose sans le Père, car ce

serait mentir; je n'avouerai par non plus que le Père est né, qu'il a souffert,

qu'il est mort et qu'il est ressuscité: ce serait mentir également. Comment,

dira-t-on, vous tirer de cet embarras?

8. Vous aimez cette question telle qu'elle est proposée; que Dieu m'accorde la

grâce que vous l'aimiez aussi telle qu'elle sera résolue. C'est-à-dire, qu'il

nous tire de peine, vous et moi; car sous l'étendard du Christ nous avons la

même foi, nous vivons sous le même Seigneur dans la même maison; membres du

même corps nous dépendons du même Chef et nous sommes animes du même souffle.

Afin donc que le Seigneur délivre des embarras de cette difficile question,

soit vous qui m'entendez, soit moi qui vous parle; voici ce que je dis: Le

Fils, et non le Père, est né de la Vierge Marie; mais cette naissance est

l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils. Le Père n'a point enduré la passion, c'est le

Fils; mais cette passion est l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils. Le Père n'est pas

ressuscité, c'est le Fils; relais la résurrection aussi est l'oeuvre du Père et

du Fils. Il semble donc que la question soit résolue. Cependant l'est-elle dans

l'Ecriture autant que dans mes paroles? Je dois donc démontrer, par le

témoignage des livres saints, que la naissance du Fils, que sa passion et sa

résurrection sont l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils; que si le Fils seul a été le

sujet de ces trois évènements, la cause en est, non pas uniquement dans le

Père, ou dans le Fils uniquement, mais dans le Père et le Fils tout ensemble.

Prouvons chacune de ces assertions, vous êtes juges, la cause dont il s'agit

est expliquée, faisons paraître les témoins. Que votre tribunal me dise

maintenant comme on dit aux plaideurs: Prouve ce que tu avances. Avec l'aide du

Seigneur je le prouve clairement, je vais produire des passages du coite

céleste; et si vous vous êtes montrés attentifs à la proposition, soyez plus

attentifs encore à ce qui en fait voir la vérité.

9. Je dois m'arrêter d'abord à la naissance du Fils et démontrer qu'elle est

l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils, quoique le Fils seul en soit le sujet. Je produis

ici l'autorité de Paul, cet habile docteur en droit divin. Il est aujourd'hui

des avocats qui citent ce grand homme pour envenimer les disputes et non pour

mettre fin aux contestations; je le cite, moi, pour établir la paix et non pour

exciter la guerre. Montrez-nous, saint Apôtre, comment la naissance du Fils est

l'oeuvre du Père. «Lorsqu'est venue la plénitude du temps, dit-il, Dieu a

envoyé son Fils, formé d'une femme, soumis à la loi, pour racheter ceux qui

étaient sous la loi (Ga 4,4-5).»

Vous avez entendu et vous avez compris, rien de plus clair, de plus évident.

C'est le Père qui a fait naître son Fils d'une vierge. La plénitude du temps

étant venue, «Dieu a envoyé son Fils,» le Père a envoyé le Christ. Comment

l'a-t-il envoyé? Il l'a envoyé «formé d'une femme, soumis à la Loi.» C'est -

249 - donc le Père qui l'a formé d'une femme et soumis à la loi.

10. Etes-vous surpris que j'aie dit: d'une vierge, et que Paul dise: d'une

femme? Ne vous en étonnez point, ne nous arrêtons pas à cela; je ne parle pas à

des ignorants. L'Écriture emploie les deux expressions; elle dit: d'une vierge,

et: d'une femme. D'une vierge: «Voici qu'une, Vierge concevra et enfantera un

Fils (Is 7,14).»

D'une femme; vous venez de l'entendre. Mais il n'y a aucune contradiction, car

la langue hébraïque appelle femmes, non pas celles qui ont perdu leur

virginité, mais toutes les personnes du sexe. La Genèse en présente un exemple

frappant, au moment même de la création d'Eve: de cette côte, dit-elle, «Dieu

forma la femme (Gn 2,22).»

Ailleurs encore l'Écriture rappelle que Dieu ordonna de séparer les femmes qui

n'avaient point connu d'homme (Nb 31,17-18 Jg 21,11).

Assez d'explication sur ce point; ne nous y arrêtons pas davantage, cherchons

plutôt à expliquer avec la grâce de Dieu ce qui présente plus de difficultés.

11. Nous avons prouvé que la naissance du Fils est l'oeuvre du Père; démontrons

aussi qu'elle est l'oeuvre du Fils. Le Fils est né de la Vierge Marie,

qu'est-ce à dire? C'est-à-dire que dans le sein de cette vierge il a pris la

nature de serviteur: la naissance dit Fils est-elle autre chose que cela? Mais

le Fils en est l'auteur comme le Père; écoutez: «Il avait la nature de Dieu,

dit l'Apôtre, et il ne croyait par usurper en s'égarant à Dieu; mais il s'est

anéanti lui-même en prenant la nature de serviteur (Ph 2,6-7).»

- «Lorsqu'est venue la plénitude du temps, Dieu a envoyé son Fils, formé d'une

femme; son fils qui lui est né selon la chair, de la race de David (Rm 1,3).»

Voilà la naissance du Fils produite par le Père; mais comme le Fils «s'est

anéanti lui-même en prenant la nature de serviteur,» sa naissance est aussi son

oeuvre. La preuve est faite, passons, appliquez-vous à ce qui suit.

12. Démontrons que la passion du Fils est également l'ouvrage et du Père et du

Fils. L'ouvrage du Père: «Il n'a point épargné son propre Fils, mais il l'a

livré pour nous tous (Rm 8,32).»

L'oeuvre du Fils: «Il m'a aimé et s'est livré lui-même pour moi (Ga 2,20).»

Le Père a livré son Fils, le Fils s'est livré lui-même; cette passion n'a pesé

que sur l'un des deux, mais elle est l'oeuvre de l'un et de l'autre; et, comme

la naissance, elle n'a pas été produite par le Père sans le Fils, ni par le

Fils sans le Père. Le Père a livré son Fils, le Fils s'est livré lui-même. Qu'a

fait ici Judas sinon le péché? Passons et arrivons à la résurrection.

13. C'est le Fils, et non le Père, qui ressuscite; mais la résurrection du Fils

est l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils. L'oeuvre du Père: «C'est pourquoi il l'a

exalté et lui a donné un nom qui est au-dessus de tout nom (Ph 2,19).»

En exaltant son Fils et en le tirant d'entre les morts, le Père l'a donc ressuscité.

Le Fils aussi ne s'est-il pas ressuscité? Sans aucun doute, car il a dit de son

corps, en style figuré: «Renversez ce temple, et je le relèverai en trois jours

(Jn 2,19).»

Autre preuve: Si la passion consiste à donner son âme, la résurrection consiste

à la reprendre. Voyons donc si le Fils a bien pu donner son âme et s'il a fallu

que le Père la lui rendit. Il est certain que le Père la lui a rendue, car il

est dit dans un psaume: «Ressuscitez-moi et je les châtierai (Ps 40,11)»

Mais pourquoi attendez-vous que nous vous montrions le Fils la reprenant de son

coté? N'a-t-il pas dit lui-même: «J'ai le pouvoir de donner mon âme?» - Mais ce

n'est pas encore ce que je vous ai promis; j'ai dit seulement: «Le pouvoir de

la donner;» et vous applaudissez, parce que vous devancez mes paroles. Formés à

l'école du Maître du ciel, vous écoutez attentivement ses leçons, vous les

reproduisez avec piété; aussi vous n'ignorez pas ce qui suit: «J'ai le pouvoir,

dit-il, de donner mon âme, et j'ai le pouvoir de la reprendre. Personne ne me

la ravit; mais je la donne et la reprends de moi-même (Jn 10,18).»

14. Nous avons rempli nos promesses; nous avons, je crois, prouvé nos

propositions par les plus sûrs témoignages. Retenez ce que vous venez

d'entendre. Je répète en peu de mots et je vous recommande de conserver dans

vos esprits une vérité que je crois fort importante. Le Père n'est pas né de la

Vierge, c'est le Fils; mais cette naissance est l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils. Le

Père n'a point souffert sur la croix; mais la passion du Fils est l'oeuvre du

Père et du Fils. Le Père n'est point ressuscité d'entre les morts; mais la

résurrection du Fils est l'oeuvre du Père et du Fils. Voilà la distinction des

personnes et l'unité des opérations. Gardons-nous donc de dire que le Père fait

quelque chose sans le Fils ou le Fils quelque chose sans le Père.

Demanderez-vous si parmi ses miracles Jésus n'en a pas fait quelques-uns sans

le Père? Eh! que - 250 - deviendraient alors ces mots: «Mon Père, qui demeure

en moi, fait lui-même mes oeuvres (Jn 14,10)?»

Ce que nous venons de dire était clair, il n'y avait qu'à l'énoncer; aucun

effort n'était nécessaire pour le comprendre, il suffisait de le rappeler.

15. Je veux vous dire encore quelque chose; et ici je vous demande

véritablement l'attention la plus active et l'union de vos coeurs avec Dieu.

L'espace ne contient que des corps, au delà de l'espace est la divinité, il ne

faut donc pas la chercher comme si elle était un corps. Elle est partout

invisible et inséparable, sans avoir ici ou là plus ou moins d'étendue; car

elle est partout tout entière, indivisible partout. Qui voit ce mystère? Qui le

comprend? Modérons-nous; rappelons-nous qui nous sommes et de quoi nous

parlons. Quelles que soient les perfections divines, croyons-les avec piété,

méditons-les avec respect, et comprenons autant que nous en sommes capables,

autant qu'il nous est donné, ce qui est ineffable. Ici point de paroles, point

de discours; c'est le coeur qu'il faut exciter et élever vers Dieu. Ce n'est

pas à Dieu de monter dans le coeur de l'homme, mais au coeur de l'homme de

monter en Dieu.

Étudions la créature: «Les invisibles perfections de Dieu, rendues

compréhensibles par les choses qui ont été faites, sont devenues visibles (Rm 1,20).»

Dans ces oeuvres de Dieu au milieu desquelles nous vivons, ne pourrait-on

découvrir quelque ressemblance, quelque objet qui nous montre trois choses bien

distinctes, mais dont les opérations sont inséparables?

16. Allons, mes frères, appliquez-vous de tout votre coeur. Rappelez-vous

d'abord quel est mon dessein; comme le Créateur est infiniment élevé au dessus

de nous, je veux savoir si dans la créature je ne trouverai pas quelque

similitude.

Au moment où la vérité brille comme un éclair dans son esprit, quelqu'un

d'entre nous pourrait peut-être s'approprier ces paroles: «J'ai dit dans le

transport de mon âme,» Et qu'as-tu dit dans ce transport de ton âme? «J'ai été

rejeté de devant vos yeux (Ps 30,23).»

Il me semble en effet que celui qui parlait ainsi avait élevé son âme vers

Dieu, qu'en s'entendant demander chaque jour «Où est ton Dieu (Ps 41,4-11)?»

il avait répandu son âme au dessus d'elle-même, que d'une manière toute

spirituelle il avait atteint à la Lumière immuable, sans que sa faiblesse en

pût supporter la vue; il retombe alors de tout son poids sur son infirmité, et

se mesurant avec cette vive splendeur de la sagesse divine, il sent que le

regard de son esprit ne peut la supporter encore. C'est dans le transport de

l'âme qu'il a vu tout cela, quand élevé au dessus de la vie des sens il était

ravi en Dieu. Mais quand il quitte Dieu en quelque sorte pour rentrer en

lui-même, il s'écrie: «J'ai dit dans le transport de mon âme;» j'ai vu alors je

ne sais quoi; il m'a été impossible de le supporter longtemps; et revenu à ce

corps mortel qui appesantit l'âme et aux mille soucis des choses périssables

qui naissent de lui, j'ai dit. Quoi? «Je suis rejeté de devant vos yeux;» vous

êtes trop haut et je suis trop bas.

Que pouvons-nous donc dire de Dieu, mes frères? Si l'on comprend ce que l'on

veut dire de lui, ce n'est pas lui; ce n'est pas lui que l'on peut comprendre,

c'est autre chose en place de lui; et si l'on croit l'avoir saisi lui-même, on

est le jouet de son imagination. Il n'est pas ce que l'on comprend; il est ce

que l'on ne comprend pas; et comment vouloir parler de ce que l'on ne saurait comprendre?

17. Cherchons par conséquent si nous ne découvrirons pas dans la créature trois

choses qui s'énoncent séparément et qui agissent d'une manière inséparable.

Mais où aller? Au ciel pour y considérer le soleil, la lune et les autres

astres? Sur terre pour y étudier les végétaux, les plantes et les animaux qui

la remplissent? Faut-il envisager le ciel même et la terre qui comprennent tout

ce que nous y voyons? Mais pourquoi, ô homme, chercher ainsi dans la créature?

Rentre en toi-même, considère-toi, étudie-toi, examine-toi en personne. Tu veux

trouver dans la créature trois choses qui s'énoncent séparément, tout eu

agissant d'une manière inséparable; s'il en est ainsi, contemple-toi d'abord.

N'es-tu pas une créature? Tu veux une comparaison, la chercheras-tu parmi les

bestiaux? C'est de Dieu qu'il est question, lorsque tu cherches cette

similitude; c'est de l'ineffable Trinité de la Majesté suprême; et parce que tu

es trop au dessous de ce qui est divin, parce que tu as dû avouer humblement

ton impuissance, tu t'es rabattu sur ce qui est humain; c'est donc sur ceci que

tu dois arrêter ta pensée.

Pourquoi chercher parmi les troupeaux, dans le soleil ou les étoiles? Lequel de

ces êtres est formé à l'image et à la ressemblance de Dieu? Il y a en toi quelque

chose de bien préférable (251) de plus rapproché de ton Créateur. Dieu en effet

n'a-t-il point formé l'homme à son image et à ski ressemblance? Inspecte ton

âme; vois si l'image de la Trinité ne t'offrira point quelque vestige de la

Trinité? Mais quelle image es-tu? C'est une image bien distante du modèle;

c'est une ressemblance et une image bien imparfaite, et qui n'est pas égale à

Dieu comme le Fils est égal au Père, dont il est l'image. Quelle différence

entre l'image reproduite dans un fils, et l'image représentée par le miroir? Tu

te vois toi-même en voyant ton image dans ton fils, car ton fils a la même

nature que toi; et s'il est autre par sa personne, par sa nature il est le

même. Ainsi clone l'homme n'est pas l'image de Dieu comme l'est le Fils unique

du Père; il est plutôt formé à son image et à une certaine ressemblance avec

lui. Examine donc si tu ne pourras découvrir en toi trois choses qui s'énoncent

séparément et qui agissent toujours ensemble. Examinons ensemble, chacun de

nous en soi-même; examinons en commun et en commun étudions notre commune

nature, notre commune substance.

18. Ouvre les yeux, ô homme, reconnais si je dis vrai. As-tu un corps, as-tu un

corps de chair? - Oui, réponds-tu. Comment, sans cela, pourrais-je occuper une

place ici, me transporter d'un lieu dans un autre? Ne me faut-il pas, pour

entendre ce qu'on me dit, des oreilles de chair, et des yeux de chair pour voir

qui me parle?- C'est une chose sûre, tuas un corps; il ne faut pas chercher

longtemps ce qui est sous nos yeux. Autre chose: Qu'est-ce qui agit par le

corps? L'oreille entend, mais elle ne te fait pas entendre; il y a au dedans

quelqu'un qui entend par elle. Tu vois par l'oeil; mais regarde l'oeil

lui-même. Te contenteras-tu de considérer la maison sans t'occuper de celui qui

l'habite? L'oeil voit-il par lui-même? N'y a-t-il pas en lui quelqu'un qui voit

par lui? Je ne dis pas L'oeil d'un mort ne voit point, quand il est sûr que

l'âme a quitté le corps; je dis que l'oeil d'un homme occupé d'autre chose ne

voit pas ce qui est devant lui. C'est donc l'homme intérieur qu'il faut

considérer en toi. C'est là surtout qu'il faut chercher l'idée de trois choses

qui s'énoncent séparément et qui agissent ensemble.

Qu'y a-t-il dans ton âme? Il est possible qu'en scrutant j'y découvre beaucoup

de choses; mais tout d'abord il s'en présente une qui est facile à saisir. Qu'y

a-t-il dans ton âme? Rappelle tes idées, réveille tes souvenirs. Je ne demande

pas que tu me croies sur parole; n'accepte ce que je vais dire qu'autant que tu

le reconnaîtras en toi. Regarde donc.

Mais, ce qui nous a échappé, voyons d'abord si l'homme est l'image du Fils

seulement, ou du Père, ou bien s'il l'est à la fois du Père, et du Fils, et

conséquemment du Saint-Esprit. Il est dit dans la Genèse: «Faisons l'homme à

notre image et à notre ressemblance (Gn 1,36).»

Ainsi le Père ne l'a point fait sans le Fils ni le Fils sans le Père. «Faisons

l'homme à notre ressemblance. - Faisons;» et non pas: je ferai, fais, qu'il

fasse, mais «faisons à l'image,» non pas à ton image ou à la mienne, mais «à la

nôtre.»

19. Je questionne donc et j'interroge ce qui est bien dissemblable. Ne dites

pas: Comment! c'est ce qu'il compare à Dieu! Je l'ai dit et redit, je vous ai

prévenus et j'ai pris mes, précautions les termes de comparaison sont à une

distance infinie; il y a entre eux la distance du ciel à la terre, de

l'immuable au muable, du Créateur à la créature, du divin à l'humain. Retenez

avant tout cette observation, et que personne ne m'accuse s'il y a tant

d'éloignement entre les deux termes; que nul ne-me montre les dents au lieu de

m'ouvrir l'oreille; tout ce que j'ai promis de faire voir c'est trois choses

qui s'énoncent séparément et qui agissent inséparablement. Quant à leur

dissemblance plus ou moins considérable avec la Trinité toute puissante, il

n'en est pas question pour le moment; ce que j'entreprends, c'est de montrer

que dans cette créature infirme et muable il y a trois facultés qui se peuvent

considérer séparément et qui agissent indivisiblement: O pensée charnelle! ô

conscience opiniâtre et infidèle! pourquoi douter que cette ineffable Majesté

possède ce que tu peux discerner en toi-même?

Voyons, ô homme, réponds-moi: As-tu de la mémoire? Mais si tu n'en as point,

comment as-tu retenu ce que j'ai dit? Peut-être as-tu oublié ce que tu viens

d'entendre; mais cette parole: J'ai dit; mais ces deux syllabes, tu ne les

retiens que par la mémoire. Comment saurais-tu qu'il y a en deux, si tu avais

oublié la première quand je prononce la seconde? Pourquoi d'ailleurs m'arrêter

plus longtemps? Pourquoi me presser, me forcer de prouver cela? Il est clair

que tu as de la mémoire.

Autre question: As-tu de l'entendement? Oui, réponds-tu. - De fait, si tu ne

pouvais, sans la mémoire, retenir ce que j'ai dit; tu ne saurais le comprendre

sans l'entendement. Tu as donc de l'entendement; cet entendement, tu

l'appliques à ce que garde ta mémoire, tu comprends alors, et comprendre c'est

savoir.

Troisième question: Tu as de la mémoire pour retenir ce qu'on te dit; tu as de

l'entendement pour comprendre ce que tu retiens; mais dis-moi: Est-ce

volontairement que tu retiens et que tu comprends? Sans aucun doute,

reprends-tu. - Donc aussi de la volonté.

Voilà les trois choses que j'avais promis de faire entendre à vos oreilles et à

votre esprit. Elles sont toutes trois en toi, tu peux les compter sans pouvoir

les séparer. Les voilà toutes trois mémoire, intelligence et volonté, remarque

bien; on les énonce séparément et elles agissent inséparablement.

20. Le Seigneur nous viendra en aide et déjà il y est venu: je le vois à la

manière dont vous saisissez; car ces acclamations me font sentir que vous

comprenez, et j'espère qu'avec sa grâce vous comprendrez également tout le

reste. J'ai promis de montrer trois choses qui s'énoncent séparément et qui

agissent inséparablement. J'ignorais ce qu'il y a dans ton âme; tu me l'as fait

connaître en disant: la mémoire. Cette parole, ce son, ce trot a jailli de ton

coeur à mes oreilles. Car avant de parler tu réfléchissais silencieusement à ce

qu'on nomme- la mémoire. Tu le savais et tu ne me l'avais pas dit encore. Or

afin de me le faire entendre, tu as prononcé ce mot, la mémoire. J'ai entendu,

j'ai distingué les trois syllabes dont est composé ce terme, la mémoire. C'est

en effet un mot de trois syllabes; ce mot a été prononcé, il a frappé mes

oreilles et a révélé quelque chose à mon esprit. Le son s'est évanoui; la cause

et l'effet du son demeurent.

Dis-moi cependant: lorsque tu prononces ce mot: mémoire? remarques-tu qu'il n'y

est question effectivement que de la mémoire? Les deux autres facultés ont

leurs noms propres; l'une s'appelle l'intelligence, l'autre la volonté et

aucune j'a mémoire. Et pourtant afin de prononcer ce dernier mot, afin de

produire ces trois syllabes, quel moyen as-tu employé? Ce mot qui ne désigne

que la mémoire a été formé en toi par la mémoire, qui te faisait retenir ce que

tu disais; par l'intelligence, qui te faisait comprendre ce que tu retenais;

enfin par la volonté, qui te portait à proférer ce que tu comprenais. Grâces au

Seigneur notre Dieu! Il a donné son secours à vous et à nous. Je le dis

franchement à votre charité, je tremblais en commençant à discuter et à vous

expliquer ce sujet. Je craignais qu'en faisant plaisir aux esprits plus

avances, je ne vinsse à ennuyer fortement les intelligences plus lentes. Mais à

votre attention et à l'activité de votre intelligence; je vois que votas avez

compris et que même avant moi vous preniez votre essor pour vous écrier: Grâces

au Seigneur.

21. Voyez encore: je reviens sans inquiétude sur ce que vous avez compris; je

ne dis rien ale nouveau, je répète seulement, pour mieux Ici graver en vous, ce

que vous avez parfaitement saisi.

De ces trois facultés nous en avons nommé une, nous avons prononcé seulement le

nom de la Mémoire, et ce nom qui n'appartient qu'à la mémoire, a été formé par

les trois facultés réunies, On n'a pu nommer la mémoire qu'avec le concours (le

la volonté, de l'intelligence et de la mémoire. On ne saurait non plus nommer

l'intelligence qu'avec le concours de la mémoire, de la volonté et de

l'intelligence; ni nommer la volonté qu'avec le concours de la mémoire, de

l'intelligence et de la volonté.

Je crois donc avoir expliqué ce que j'ai promis d'expliquer; j'ai vu réuni dans

ma pensée ce que j'ai énoncé séparément. Il a fallu les trois facultés pour

former le nom de l'une d'entre elles, et ce nom formé par les trois

n'appartient qu'à une seule. Les trois ont formé le nom de la mémoire; et ce

nom n'appartient qu'à la mémoire. Les trois ont formé le nom de l'intelligence;

et ce nom ne désigne que l'intelligence. Les trois ont formé le nom de la

volonté; et ce nom n'appartient qu'à la volonté. Ainsi la Trinité a formé la

chair du Christ; et cette chair n'est qu'au Christ. Ainsi la Trinité a formé la

colombe descendue du ciel; et cette colombe ne désigne que l'Esprit-Saint.

Ainsi la Trinité a fait entendre la voit d'en haut; et cette voix n'appartient

qu'au Père.

22. Que nul maintenant ne me dise, que nul n'essaie de tourmenter tua faiblesse

en s'écriant: De ces trois facultés que tu as montrées dans notre esprit ou

plutôt clans notre âme, laquelle désigne le Père, c'est-à-dire la ressemblance

du Père, laquelle désigne le Fils et laquelle le (253) Saint-Esprit? Je ne

saurais le dire, je ne saurais l'expliquer. Laissons quelque chose à la

méditation, laissons aussi quelque chose au silence. Rentre en toi, et te

soustrais au bruit. Lis en toi-même, si toutefois tu as su te faire dans ta

conscience connue un doux sanctuaire; ou tu ne produises ni bruit ni querelle,

où tu tic cherches ni à disputer ni à contredire avec opiniâtreté. «Sois docile

à écouter la parole, afin de la comprendre (Si 5,13).»

Peut-être diras-tu bientôt: «Vous ferez entendre à mon oreille la joie et

l'allégresse, et mes os tressailleront dans l'humilité, (Ps 50,10)»

et non dans l'orgueil.

23. C'est donc assez d'avoir montré ces trois facultés qui s'énoncent

séparément et qui agissent inséparablement. Si tu as pu reconnaître ce

phénomène dans ta personne, dans un homme, dans un homme qui marche sur la

terre et qui porte un corps fragile dont le poids appesantit l'ante; crois donc

que le Père, le Fils et le Saint-Esprit peuvent se montrer séparément sous des

symboles visibles, sous des formes empruntées à la créature, et néanmoins agir

inséparablement. C'est assez.

Je ne dis pas que la mémoire représente le Père, l'intelligence le Fils et la

volonté l'Esprit Saint; je ne dis pas cela, quelque sens que l'on y donne, je

ne l'ose. Réservons ces mystères pour de plus grands esprits, et faibles

expliquons aux faibles ce que nous pouvons. Je ne dis donc pas qu'entre ces

trois facultés et la Trinité il y ait analogie, c'est-à-dire des rapports qui

permettent une comparaison véritable; je ne dis pas cela non plus. Que dis-je,

alors? Je dis qu'en toi j'ai découvert trois facultés qui s'énoncent séparément

et qui agissent inséparablement car le nom de chacune est formé par les trois,

sans toutefois convenir aux trois mais à une seule d'entre elles. Et si tu as

entendu, si tu as saisi, si tu as retenu cela, crois en Dieu ce que tu ne

saurais voir en lui. Tu peux connaître en toi ce que tu es; mais dans Celui qui

t'a fait, comment, quoi qu'il soit, connaître ce qu'il est? Si tu le peux un

jour, tu n'en es pas capable aujourd'hui; et lors-même que tu le pourras, te

sera-t-il possible de connaître Dieu comme Dieu se connaît?

Que votre charité se contente de ce peu. Nous avons dit ce que nous avons pu;

nous avons, à votre demande, acquitté nos promesses; ce qu'il faudrait ajouter

encore pour élever plus haut votre entendement, demandez-le au Seigneur.

SOURCE : https://www.clerus.org/bibliaclerusonline/es/dnd.htm

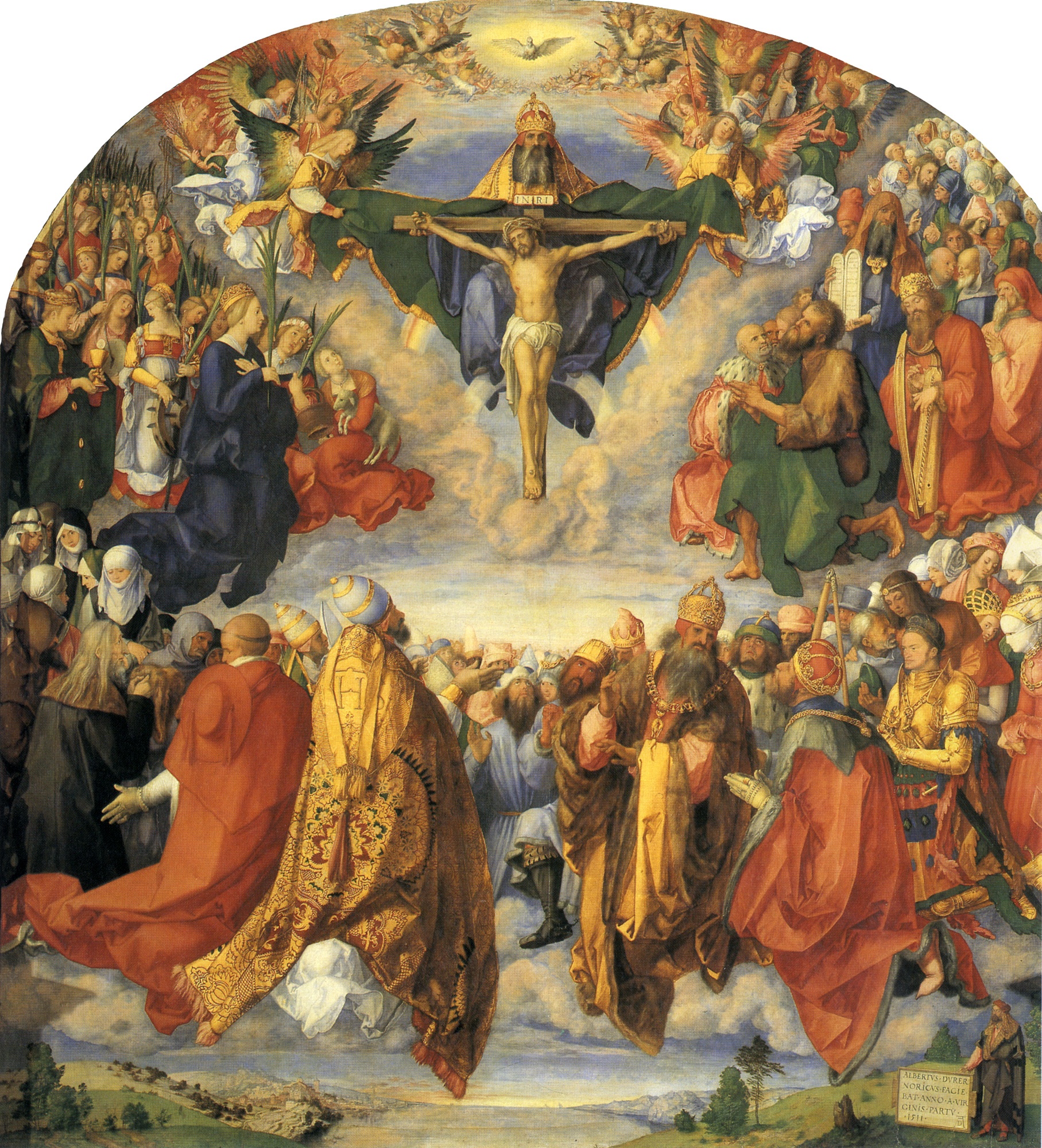

Albrecht

Dürer, Adoration de la Sainte Trinité, 1511, retable, 135 x

123.4, musée d'Histoire de l'art de Vienne.

(https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Adoration_de_la_Sainte_Trinit%C3%A9)

Albrecht

Dürer, Adoration de la Sainte Trinité, 1511, retable, 135 x

123.4, musée d'Histoire de l'art de Vienne.

(https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Adoration_de_la_Sainte_Trinit%C3%A9)

THE

CREDO

THE

APOSTLES CREED

I believe in God the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth.

I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord. He was conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary Under Pontius Pilate He was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended to the dead. On the third day he rose again. He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.

Amen.

THE

NICENE CREED

We believe in one God, the Father,

the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father. Through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation, he came down from heaven: by the power of the Holy Spirit he was born of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered died and was buried. On the third day he rose again in fulfillment of the Scriptures; he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. With the Father and the Son he is worshipped and glorified. He has spoken through the Prophets. We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church. We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins. We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Amen.

Detail

of the earliest known artwork of

the Trinity, the Dogmatic or Trinity Sarcophagus, c. 350 (Vatican

Museums). Three similar figures, representing the Trinity, are involved in

the creation of Eve,

whose much smaller figure is cut off at lower right; to her right, Adam lies on the

ground.

The Blessed Trinity

This article is divided

as follows:

Proof

of the doctrine from Scripture

Proof

of the doctrine from Tradition

The

doctrine as interpreted in Greek theology

The

doctrine as interpreted in Latin theology

The dogma of the Trinity

The Trinity is the term

employed to signify the central doctrine of

the Christian

religion — the truth that

in the unity of the Godhead there

are Three Persons,

the Father, the Son,

and the Holy

Spirit, these Three Persons being

truly distinct one from another.

Thus, in the words of

the Athanasian

Creed: "the Father is God,

the Son is God,

and the Holy

Spirit is God,

and yet there are not three Gods but

one God."

In this Trinity of Persons the Son is

begotten of the Father by an eternal generation,

and the Holy

Spirit proceeds by an eternal procession

from the Father and the Son.

Yet, notwithstanding this difference as to origin, the Persons are

co-eternal and co-equal: all alike are uncreated and omnipotent.

This, the Church teaches,

is the revelation regarding God's

nature which Jesus

Christ, the Son

of God, came upon earth to deliver to the world: and which she proposes

to man as

the foundation of her whole dogmatic system.

In Scripture there

is as yet no single term by which the Three Divine Persons are

denoted together. The word trias (of which the Latin trinitas is

a translation) is first found in Theophilus

of Antioch about A.D. 180. He speaks of "the Trinity of God [the

Father], His Word and

His Wisdom (To

Autolycus II.15). The term may, of course, have been in use before

his time.

Afterwards it appears in its Latin form of trinitas in Tertullian (On

Pudicity 21). In the next century the word is in general use. It is

found in many passages of Origen ("In

Ps. xvii", 15). The first creed in

which it appears is that of Origen's pupil, Gregory

Thaumaturgus. In his Ekthesis

tes pisteos composed between 260 and 270, he writes:

There is therefore

nothing created,

nothing subject to another in the Trinity: nor is there anything that has been

added as though it once had not existed, but had entered afterwards: therefore

the Father has never been without the Son,

nor the Son without

the Spirit:

and this same Trinity is immutable and unalterable forever (P.G., X, 986).

It is manifest that

a dogma so mysterious presupposes

a Divine

revelation. When the fact of revelation,

understood in its full sense as the speech of God to man,

is no longer admitted, the rejection of the doctrine follows

as a necessary consequence.

For this reason it has no place in the Liberal Protestantism of

today. The writers of this school contend that the doctrine of

the Trinity, as professed by the Church,

is not contained in the New

Testament, but that it was first formulated in the second century and

received final approbation in the fourth, as the result of the Arian and Macedonian controversies.

In view of this assertion it is necessary to

consider in some detail the evidence afforded by Holy

Scripture. Attempts have been made recently to apply the more extreme

theories of comparative religion to

the doctrine of

the Trinity, and to account for it by an imaginary law of nature

compelling men to

group the objects of their worship in threes. It seems needless to give more

than a reference to these extravagant views, which serious thinkers of every

school reject as destitute of foundation.

Proof of doctrine from

Scripture

New Testament

The evidence from

the Gospels culminates

in the baptismal commission

of Matthew

28:20. It is manifest from the narratives of the Evangelists that Christ only

made the great truth known to

the Twelve step

by step.

First He taught them to

recognize in Himself the Eternal

Son of God. When His ministry was drawing to a close, He promised that the

Father would send another Divine Person,

the Holy

Spirit, in His place. Finally after His resurrection,

He revealed the doctrine in

explicit terms, bidding them "go and teach all nations, baptizing them

in the name of the Father, and of the Son,

and of the Holy

Ghost" (Matthew

28:18). The force of this passage is decisive. That "the Father"

and "the

Son" are distinct Persons follows

from the terms themselves, which are mutually exclusive. The mention of

the Holy

Spirit in the same series, the names being connected one with the

other by the conjunctions "and . . . and" is evidence that we have

here a Third Person co-ordinate

with the Father and the Son,

and excludes altogether the supposition that the Apostles understood

the Holy

Spirit not as a distinct Person,

but as God viewed

in His action on creatures.

The phrase "in the

name" (eis to onoma) affirms alike the Godhead of

the Persons and

their unity of nature.

Among the Jews and

in the Apostolic

Church the Divine name was representative of God.

He who had a right to

use it was invested with vast authority: for he wielded the supernatural powers

of Him whose name he employed. It is incredible that the phrase "in the

name" should be here employed, were not all the Persons mentioned

equally Divine. Moreover, the use of the singular, "name," and not

the plural, shows that these Three Persons are

that One

Omnipotent God in whom the Apostles believed.

Indeed the unity of God is

so fundamental a tenet alike of the Hebrew and

of the Christian

religion, and is affirmed in such countless passages of the Old and New

Testaments, that any explanation inconsistent with this doctrine would

be altogether inadmissible.

The supernatural appearance

at the baptism of Christ is

often cited as an explicit revelation of

Trinitarian doctrine,