Saint Damien de Molokai

(Joseph de Veuster)

Prêtre - Religieux Picpus (+ 1889)

Né à Tremelo (Belgique) le 03.01.1840 Retourné à Dieu le 15.04.1889 à Molokaï

(Hawaï) Béatifié le 04.06.1995 par Jean-Paul II à Bruxelles.

Joseph de Veuster naît dans une famille belge de langue flamande au village de

Tremelo en 1840. Il est le septième de huit enfants dont quatre entreront en

religion. Il suit l’un de ses frères dans la Congrégation des Sacrés Cœur de

Jésus et Marie (ou Pères de Picpus), prenant le nom de Damien. Il y développe

son amour de l’adoration eucharistique qui sera son seul soutien dans les

heures de solitude, et son amour de la Sainte Vierge. Dans son ardeur

missionnaire, le jeune religieux s’adresse directement au supérieur général et

obtient la permission de partir, à la place de son frère tombé malade, dans la

mission nouvellement fondée aux îles Hawaï. Il s’embarque avant même son ordination

sacerdotale qui lui sera conférée à Honolulu. Le gouvernement avait regroupé

d’autorité tous les lépreux de l’archipel dans l’île Molokaï, le Père Damien

est choisi parmi d’autres volontaires pour assurer une présence sacerdotale

dans cet enfer de désespoir et de misère morale. Il organise alors la vie

religieuse, sociale et fraternelle dans cette île mise au ban de la société. Il

se solidarise avec les lépreux (il aimait dire: "nous les lépreux")

et même, malgré ses précautions, il est atteint à son tour par la maladie.

“Qu’il est doux de mourir comme un enfant du Sacré-cœur”, disait-il à son

dernier jour. Il avait souhaité que ce fut le jour de Pâques; ce fut le Lundi

Saint, 15 avril 1889. source Abbaye Saint Benoît de Port-Valais

"Construire un monde plus juste en solidarité avec les plus pauvres"

Le Père Damien: Le plus grand Belge de tous les temps (Action Damien)

Béatifié par le Pape Jean-Paul II le 4 juin 1995

Biographie sur le site site officiel de la Province de France des Frères et du Secteur

France des Sœurs de la Congrégation des Sacrés-Cœurs (dite de Picpus).

Il est canonisé le 11 octobre 2009 et une 'année Damien' s'est ouverte à

Louvain le 10 mai 2009 (catho.be).

Canonisation de Jeanne Jugan et de Damien de Veuster - dossier sur le site

internet de l'Eglise catholique en France.

"Le Père Damien, dans le siècle Jozef De Veuster, membre de la

Congrégation des Sacrés Cœurs de Jésus et de Marie, a quitté sa terre natale,

les Flandres, pour annoncer l’évangile aux îles Hawaii et a consacré la

dernière partie de sa vie aux lépreux sur l’île de Molokaï, devenant lui-même

lépreux.

En ce 20e anniversaire de la canonisation d’un autre saint belge, le Frère

Mutien-Marie, l’Eglise en Belgique - a relevé Benoît XVI dans son homélie - est

unie une nouvelle fois pour rendre grâce à Dieu pour l’un de ses fils reconnu

comme un authentique serviteur de Dieu. Nous nous souvenons devant cette noble

figure que c’est la charité qui fait l’unité: elle l’enfante et la rend

désirable. À la suite de saint Paul, saint Damien nous entraîne à choisir les

bons combats (cf. 1 Tim 1, 18), non pas ceux qui portent la division, mais ceux

qui rassemblent. Il nous invite à ouvrir les yeux sur les lèpres qui défigurent

l’humanité de nos frères et appellent encore aujourd’hui, plus que notre

générosité, la charité de notre présence servante."

(source: Radio Vaticana - Cinq nouveaux saints pour l'Eglise universelle - 11

octobre 2009)

La fête liturgique de Saint Damien de Molokaï est le 10 mai:

Il aurait été logique de fêter Damien au jour de sa mort (Dies Natalis), le 15

avril. Mais, désirant mettre en relief la figure de Damien, lors de la

béatification de l'Apôtre des Lépreux en 1995, et souhaitant éviter que

celle-ci ne tombe lors de la Pâque, Jean-Paul II, a souhaité fixer ce jour au

10 mai. Cela correspond à l'arrivée de Joseph Damien de Veuster à la léproserie

de Molokaï. (site de la congrégation des sacrés cœurs de Jésus et de Marie -

Picpus - France)

À Kalawao, dans l’île de Molokai en Océanie, l’an 1889, Damien de Veuster,

prêtre de la Congrégation des Missionnaires des Saints Coeurs de Jésus et de

Marie, qui se dévoua tellement de tout son cœur au service des lépreux qu’il

contracta lui-même la lèpre et en mourut.

Martyrologe romain

le Bienheureux P. Damien de Veuster descendit dans la léproserie de Molokai –

considérée alors "le cimetière et l’enfer des vivants" – et, dès sa

première prédication, il embrassa tous ces malheureux en disant simplement:

"Nous lépreux." Et au premier malade qui lui dit: "Attention,

Père, vous pourriez attraper mon mal", il répondit: "Mon fils, si la

maladie m’emporte le corps, Dieu m’en donnera un autre."

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/9930/Saint-Damien-de-Molokai-(Joseph-de-Veuster).html

Padre

Damiano tra i lebbrosi della colonia di Kalaupapa

Cathedral

of Our Lady of Peace archived image of Father Damien with the Kalawao Girls

Choir, at Kalaupapa, Moloka'i, circa 1878. The photo was recently used in the

project "The Separating Sickness" in 1997. Henry Lyman

Chase - Hawaii State Archives Law, Anwei Skinsnes (2012) Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory (Ka

Hokuwelowelo), Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,

p. 118 ISBN: 978-0-8248-6580-1. OCLC: 830023588.

VOYAGE APOSTOLIQUE EN

BELGIQUE

HOMÉLIE DU SAINT-PÈRE

JEAN-PAUL II

Solennité de la Pentecôte, Bruxelles

Dimanche 4 juin 1995

Geliefde broeders en

zusters,

1. «Zoals de Vader

Mij gezonden heeft, zo zend Ik u... Ontvangt de Heiligе Geest » [1].

De Apostelen hoorden deze

woorden uit de mond van de Verrezen Christus, op de avond van de verrijzenis.

's Morgens van de eerste dag van de week, stelden de vrouwen en daarna Petrus

en Johannes vast, dat het graf waar ze Jezus hadden neergelegd, leeg was. 's

Avonds van dezelfde dag verscheen Jezus in hun midden. Het was dezelfde

Jezus die ze eerder gekend hadden, maar toch was Hij verschillend. In zijn

lichaam droeg Hij de tekenen van zijn kruisiging en terzelfder tijd was Hij

verrezen. Niet meer onderworpen aan de huidige wetten van de materie, kon Hij

het cenakel binnentreden, ook al waren alle deuren gesloten. Na de Apostelen

gegroet te hebben: «de vrede zij met u », richt de verrezen Jezus woorden tot

hen die voor de toekomst van de Kerk beslissend zijn: «Zoals de Vader Mij

gezonden heeft, zo zend Ik u ». Na zo gesproken te hebben, blaast Hij over hen

en zegt: «Ontvangt de Heilige Geest. Wier zonden gij vergeeft, hun zijn ze

vergeven, en wier zonden gij niet vergeeft, hun zijn ze niet vergeven » [2].

Het ware moment van de

nederdaling van de Heilige Geest heeft plaats op de avond van de

verrijzenis. Jezus, de Zoon Gods, één in wezen met de Vader, blaast over de

Apostelen. Deze adem manifesteert de oorsprong van de Heilige Geest, die komt

van de Vader en de Zoon. Deze adem is heilbrengend. Hij bevat al de kracht

van de verlossing die Christus bewerkt heeft. We begrijpen dat Christus,

nadat Hij tot zijn Apostelen gezegd heeft: « Ontvangt de Heilige Geest »,

dadelijk over de vergiffenis der zonden spreekt. Hij geeft hun de macht om

zonden te vergeven, een macht die van God komt. Hij verleent hun die macht en

terzelfder tijd zijn verlossende adem, die de definitieve komst van de Heilige

Geest aankondigt. Op de dag van Pinksteren leidde de nederdaling van de Heilige

Geest over de Apostelen hen die, op het woord van Petrus, in Christus geloofden

naar het doopsel. Het waren zij die naar het heil verlangden, dat aan alle

mensen gegeven is, door het Kruis en de Verrijzenis van Christus.

2. De Handelingen van de

Apostelen beschrijven in detail de ge beurtenis van Sinksen. De Heilige Geest,

de adem van de Vader en de Zoon, openbaart zijn aanwezigheid door een

hevige windstoot. Boven de Apostelen, in het cenakel verenigd, verschijnt iets

als vuur, dat zich in tongen verdeelt, die zich op ieders hoofd neerzetten. Zo

getuigen de natuurelementen wind en vuur van de komst van de Heilige Geest.

Maar deze manifestaties

gaan gepaard met een bovennatuurlijk ver schijnsel. De Apostelen, beginnen,

van de Heilige Geest vervuld, vreemde talen te spreken, naargelang de

Geest hun te vertolken geeft. Dit gebeuren wekt grote verbazing onder allen die

op dat ogenblik in Jeruzalem verblijven, «vrome joden, afkomstig uit alle

volkeren onder de hemel » [3]. Verbaasd en verwonderd roepen ze uit: «

Zijn al die daar spreken dan geen Galileeërs? Hoe komt het dan dat ieder van

ons hen hoort spreken in zijn eigen moedertaal » [4]?

Wanneer de schrijver van

het boek der Handelingen van de Apostelen de lijst opmaakt van de landen van de

toen gekende wereld, van waar de bedevaarders afkomstig zijn, die aan het

pinkstergebeuren deelnemen, tekent hij bijna een geografie van de eerste

evangelіatie, die de Apostelen moeten ten uitvoer brengen, door in de

verschillende talen «de wondere tekenen van God» te verkondigen. Met

uitzondering van Rome, wordt van geen enkel land uit het Westen, het Centrum,

het Noorden of het Oosten van Europa melding gemaakt. België wordt niet

genoemd en nog minder worden de eilanden van de Molokаi-archipel in de

verre Pacifiek genoemd. Geen woord over het vaderland van Pater Damiaan de

Veuster, of over het land waar hij naar toe zou trekken als missionaris, om er

zijn leven te geven voor Christus, in dienst van de liefde tot de naaste.

3. Bij deze vermelding

van de plaatsen die Pater Damiaan lief waren, groet ik Hunne Majesteiten de

Koning der Belgen en de Koningin, Hare Majesteit Koningin Fabiola, alsook de

leden van het Corps Diplomatique en de burgerlijke gezagvoerders. Mijn

broederwens aan Kardinaal Danneels, die zijn verjaardag viert, en mijn

hartelijke wensen, ook aan Kardinaal Suenens, die dit over enkele dagen zal

doen. Een warme groet aan de verzamelde bisschoppen. Ik ben blij om de

aanwezigheid van de familie van Pater Damiaan, van talrijke missionarissen, ook

van de delegaties van Tremelo, Malonne en Leuven en van de vereniging van de

Vrienden van Pater Damiaan, de Damiaanactie.

Ik ben gelukkig de

afgevaardigden van de Hawaï-eilanden te verwelkomen:

Weiléna eilohei oknu. Mei

keikou peikeihé ei peiu kei meiluhlei ei mei kei eilohei o Ieisu Chrésto.

4. De eeuwen door heeft

de Kerk zich altijd verder ontwikkeld en het Evangelie gebracht tot aan de

uiteinden der aarde. Zo heeft ze de vraag van Christus zelf beantwoord, die de

Heilige Geest geschonken heeft, onmisbare kracht om die opdracht van

evangelisatie te volbrengen. De Kerk dankt de Heilige Geest voor Pater

Damiaan, want het is de Geest die hem het verlangen heeft ingegeven om zich

zonder reserve aan de melaatsen van de eilanden van de Pacifiek, in het

bijzonder van Molokaï, te wijden. De Kerk erkent en bevestigt vandaag,

door mijn mond, de waarde en het voorbeeld van Pater Damiaaan op de weg

van heiligheid. Ze looft God die hem gegidst heeft tot op het einde van zijn

bestaan, op een weg die dikwijls moeilijk was. Ze beschouwt met vreugde

wat God kan tot stand brengen doorheen de menselijke zwakheid, want «Hij is

het, die ons de heiligheid schenkt en de mens is het die haar ontvangt » [5].

Pater Damiaan heeft,

tijdens zijn ministerie, een bijzondere vorm van heiligheid ontwikkeld. Hij

was terzelfder tijd priester, religieus en missionaris. In deze

drievoudige hoedanigheid, heeft hij het gelaat van Christus zichtbaar

gemaakt. Hij heeft de weg van het heil getoond, het Evangelie onderricht

en onvermoeibaar tot de ontwikkeling bijgedragen. Hij heeft op Molokaï het

religieuze, sociale en broederlijke leven georganiseerd. De bewoners van het

eiland waren toen door de maatschappij verbannen. Met Damiaan kreeg iedereen

zijn plaats, werd iedereen erkend en door zijn broeders bemind.

Op deze Pinksterdag

vragen wij voor onszelf en voor alle mensen de bijstand van de Heilzģe

Geest om ons door Hem te laten grijpen. Wij hebben de zekerheid dat Hij

ons niets onmogelijks oplegt, maar dat Hij ons zijn en ons bestaan, langs soms

steile wegen, tot volmaaktheid leidt. Deze viering is ook een oproep tot

verdieping van het geestelijk leven van zieken en gezonden, van armeren en

rijkeren.

Dierbare broeders en

zusters van België, u zijt allen tot heiligheid geroepen. Stel uw talenten

ter beschikking van Christus, van de Kerk, van uw broeders. Laat u nederig en

geduldig kneden door de Geest! De heiligheid is niet de volmaaktheid van

de menselijke criteria. Ze is niet aan een klein aantal uitzonderlijke

wezens voorbehouden. Ze is voor allen. De Heer is het die tot de heiligheid

toegang verschaft, wanneer wij aanvaarden om, niettegenstaande onze zonde en

ons soms opstandig temperament, mee te werken, tot glorie van God en tot het

heil van de wereld. In uw dagelijks leven zijt gij geroepen om keuzen te maken

die «soms buitengewone offers» vragen [6]. Dat is de prijs van het ware geluk.

Hiervan is de apostel van de melaatsen getuige.

5. Today’s celebration is

also a call to solidarity. While Damien was among the sick, he could say

in his heart: "Our Lord will give me the graces I need to carry my cross

and follow him, even to our special Calvary at Kalawao". The certainty

that the only things that count are love and the gift of self was his

inspiration and the source of his happiness. The apostle of the lepers is a

shining example of how the love of God does not take us away from the world.

Far from it: the love of Christ makes us love our brothers and sisters even to

the point of giving up our lives for them.

I am pleased to greet the

Bishop of Honolulu who accompanied the pilgrims of Hawaii for this solemn

joyful celebration.

6. An euch, liebe

Schwestern und Brüder Belgiens, liegt es, die Fackel Pater Damians erneut zu

ergreifen. Sein Zeugnis ist für euch alle, vor allem für euch junge Menschen,

ein Anruf, um ihn kennenlernen zu können und durch sein Opfer in euch die

Sehnsucht nach der Gottesliebe, dem Quell aller wahren Liebe und jedes

gelungenen Lebens, und das Verlangen, aus eurem Leben eine fruchtbare Gabe zu

machen, wachsen zu lassen.

7. Mon cœur se

tourne vers ceux qui sont aujourd’hui encore atteints de la lèpre. Avec

Damien, ils ont désormais un intercesseur, car, avant d’être malade, il s’était

déjà identifié à eux et disait souvent: «Nous autres, lépreux». En appuyant

auprès de Paul VI la

cause de béatification, Raoul Follereau avait eu l’intuition du rayonnement

spirituel que Damien pouvait avoir après sa mort. Ma prière rejoint aussi tous

ceux qui sont frappés par des maladies graves et incurables, ou qui sont à

l’approche de la mort. Comme les évêques de votre pays l’ont rappelé, tous les

hommes ont le droit d’avoir, de la part de leurs frères, une main tendue, une

parole, un regard, une présence patiente et aimante, même s’il n’y a pas

d’espoir de guérison. Frères et Sœurs malades, vous êtes aimés de Dieu et

de l’Eglise! La souffrance est pour l’humanité un mystère inexplicable; si

elle écrase l’homme laissé à ses propres forces, elle trouve un sens dans le

mystère du Christ mort et ressuscité, qui demeure proche de tout être et qui

lui murmure: «Courage, j’ai vaincu le monde» [7]. Je rends grâce au Seigneur pour les

personnes qui accompagnent et entourent les malades, les petits, les êtres

faibles et sans défense, les exclus: je pense spécialement aux professionnels

de la santé, aux prêtres et aux laïcs des équipes d’aumônerie, aux visiteurs

d’hôpitaux, et à ceux qui se dévouent pour la cause de la vie, pour la

sauvegarde des enfants, et pour que chaque homme ait un toit et une place au

sein de la société. Par leur action, ils rappellent l’incomparable dignité de

nos frères qui souffrent, dans leur corps ou dans leur cœur; ils manifestent

que toute vie, même la plus fragile et la plus souffrante, a du poids et du

prix au regard de Dieu. Avec les yeux de la foi, au-delà des apparences, on

peut voir que tout être est porteur du riche trésor de son humanité et de la

présence de Dieu, qui l’a tissé dès l’origine [8].

8. Dans la Première

Lettre aux Corinthiens, saint Paul écrit: «Personne n’est capable de dire

"Jésus est le Seigneur" s’il n’est avec l’Esprit Saint» [9]. En effet, dire «Jésus est le Seigneur»

signifie confesser sa divinité, comme l’avait confessée saint Pierre au nom des

Apôtres à Césarée de Philippe. «Le Seigneur» – Kyrios en grec – est

celui qui domine sur toute la création, celui auquel s’adresse le psaume que

nous avons entendu: «Bénis le Seigneur, ô mon âme; Seigneur mon Dieu, tu es si

grand! Quelle profusion dans tes œuvres, Seigneur! La terre s’emplit de tes

biens. Tu reprends leur souffle, ils expirent et retournent à leur poussière.

Tu envoies ton souffle: ils sont créés; tu renouvelles la face de la terre» [10].

Ces versets de la

liturgie parlent du pouvoir de Dieu sur toute la création. Elles

concernent l’Esprit Saint, qui est Dieu, et qui donne la vie avec le Père

et le Fils. Aussi, l’Eglise prie-t-elle aujourd’hui: «O Seigneur, envoie ton

Esprit qui renouvelle la face de la terre»! L’Esprit Saint fait en sorte

que l’homme parvienne à la connaissance du Christ et confesse sa divinité:

«Jésus est Seigneur» – Kyrios!

Cette foi en la divinité

du Christ, le Père Damien, d’une certaine manière, l’a sucée avec le lait

maternel, dans sa famille en Flandres. Il a grandi avec elle et il la porta

ensuite à ses frères et sœurs, dans les lointaines îles Molokaï. Pour confirmer

jusqu’au bout la vérité de son témoignage, il a offert sa vie au milieu d’eux.

Qu’aurait-il pu offrir d’autre aux lépreux, condamnés à une mort lente, sinon

sa propre foi et cette vérité que le Christ est Seigneur et que Dieu est

Amour? Il devint lépreux au milieu des lépreux, il devint lépreux pour les

lépreux. Il a souffert et il est mort comme eux, croyant en la résurrection

dans le Christ, car le Christ est Seigneur!

9. Saint Paul écrit

encore: «Les dons de la grâce sont variés, mais c’est toujours le même Esprit.

Les fonctions dans l’Eglise sont variées, mais c’est toujours le même Seigneur.

Les activités sont variées, mais c’est toujours le même Dieu qui agit en tous.

Chacun reçoit le don de manifester l’Esprit en vue du bien de tous» [11]. Par ces paroles, l’Apôtre présente

une vision dynamique de l’Eglise, dynamique et en même temps

charismatique. Dans cette vision charismatique, se manifeste l’Esprit que

le Père, au nom du Christ, envoie sur les Apôtres. Tout a sa source dans les

divers dons de la grâce, qui rendent les croyants capables de réaliser les

activités, les vocations et les ministères variés, dans l’Eglise et dans le

monde.

Le regard de Paul est

universel, et, dans ce regard universel, nous retrouvons certainement une

partie de la vie de notre bienheureux: son charisme, sa vocation et son

ministère. En tout ceci, l’Esprit Saint s’est manifesté, pour le bien de tous.

La béatification du Père Damien sert au bien de toute l’Eglise. Elle revêt une

importance particulière pour l’Eglise qui est en Belgique, ainsi que pour

l’Eglise dans les îles de l’Océanie.

10. Il est providentiel

que cette béatification se déroule au cours de la solennité de la

Pentecôte. Dans la Lettre au Corinthiens, Paul continue ainsi: «Notre corps

forme un tout, il a pourtant plusieurs membres; et tous les membres, malgré

leur nombre, ne forment qu’un seul corps. Il en est ainsi pour le Christ.

Tous, ...nous avons été baptisés dans l’unique Esprit pour former un seul

corps. Tous, nous avons été désaltérés par l’unique Esprit» [12]. Cet Esprit a soufflé dans les

lointaines îles de l’Océanie, par le ministère du Père Damien; il trouve un

écho dans vos familles, dans vos paroisses et dans les Congrégations

missionnaires. Dans l’histoire de votre pays, se sont multipliées les œuvres,

pour le bien et la croissance de l’Eglise; il faut noter en particulier la

naissance de nombreuses congrégations religieuses qui ont eu un rayonnement

important, par leurs activités spirituelles, caritatives, intellectuelles et

sociales. D’autre part, des personnes douées de profonds charismes ont commencé

à réaliser de grandes œuvres. Il suffit de mentionner des fondations comme les

Universités catholiques de Louvain et de Louvain-la-Neuve, ainsi que la Jeunesse

ouvrière catholique (JOC); il suffit de se rappeler des personnes

comme le Cardinal Mercier, pionnier de l’œcuménisme, ou plus tard, le

Cardinal Cardijn, fondateur de la JOC, et bien d’autres par qui l’Esprit

agissait, pour le bien de toute l’Eglise, non seulement sur votre terre, mais

encore dans le monde entier.

11. Bienheureux Damien,

tu t’es laissé conduire par l’Esprit Saint, en fils obéissant à la volonté du

Père. Par ta vie et par ton œuvre missionnaire, tu manifestes la tendresse et

la miséricorde du Christ pour tout homme, lui dévoilant la beauté de son être

intérieur, qu’aucune maladie, qu’aucune difformité ni que nulle faiblesse

ne peuvent totalement défigurer. Par ton action et par ta prédication, tu

rappelles que Jésus a pris sur lui la pauvreté et la souffrance des hommes, et

qu’il en a révélé la valeur mystérieuse. Intercède auprès du Christ, médecin

des corps et des âmes, pour nos frères et sœurs malades, afin que, dans les

angoisses et les douleurs, ils ne se sentent pas abandonnés, mais, unis au

Seigneur ressuscité et à son Eglise, qu’ils découvrent que l’Esprit Saint vient

les visiter, et qu’ils obtiennent ainsi la consolation promise aux affligés.

12. «Gloire au Seigneur à tout jamais! Que Dieu se réjouisse en ses œuvres» [13]! C’est avec ces paroles du psalmiste que je veux conclure notre méditation, en ce jour solennel si attendu, au cours duquel le fruit mûr de la sainteté – le Père Damien de Veuster – reçoit la gloire des autels dans sa patrie. Frères et sœurs, soyez dociles à l’Esprit Saint, pour qu’à travers votre vie les hommes puissent découvrir le Dieu de qui vient tout don parfait!

[1] Io. 20, 21-22.

[2] Io. 20, 22-23.

[3] Act. 2, 5.

[4] Ibid. 2, 7-8.

[5] Origenis Homiliae in Samuelem, I, 11,

11.

[6] Ioannis Pauli PP. II Veritatis

Splendor, 102.

[7] Io. 16, 33.

[8] Cfr. Ps. 139 (138).

[9] 1 Cor. 12, 3.

[10] Ps. 104 (103), 1. 24. 29-30.

[11] 1 Cor. 12, 4-7.

[12] 1 Cor. 12, 12-13.

[13] Ps. 104 (103), 31.

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

CHAPELLE PAPALE

POUR LA CANONISATION DES

BIENHEUREUX:

ZYGMUNT SZCZĘSNY FELIŃSKI

(1822 – 1895)

FRANCISCO COLL Y GUITART

(1812 – 1875)

JOZEF DAMIAAN DE VEUSTER

(1840 – 1889)

RAFAEL ARNÁIZ BARÓN (1911

– 1938)

MARIE DE LA CROIX

(JEANNE) JUGAN (1792 – 1879)

HOMÉLIE DU PAPE BENOÎT

XVI

Basilique Vaticane

Dimanche 11 octobre 2009

Chers frères et sœurs!

"Que dois-je faire pour avoir en héritage la vie éternelle?". C'est par cette question que commence le bref dialogue que nous avons écouté dans la page de l'Evangile entre un personnage, ailleurs identifié comme le jeune homme riche, et Jésus (cf. Mc 10, 17-30). Nous n'avons pas beaucoup de détails concernant ce personnage anonyme; de ces quelques traits, nous arrivons cependant à percevoir son désir sincère de parvenir à la vie éternelle en conduisant une honnête et vertueuse existence terrestre. Il connaît en effet les commandements et les observe fidèlement depuis le début de sa jeunesse. Et pourtant, tout ceci, qui est certes important, ne suffit pas - dit Jésus - une seule chose manque, mais elle est essentielle. En le voyant alors bien disposé, le divin Maître le fixe avec amour et lui propose le saut de qualité, l'appelle à l'héroïsme de la sainteté et lui demande de tout abandonner pour le suivre: "Vends tout ce que tu as, donne-le aux pauvres (...) puis viens et suis-moi" (v. 21).

"Viens et suis-moi!". Voilà la vocation chrétienne qui jaillit d'une proposition d'amour du Seigneur et qui ne peut se réaliser que grâce à notre réponse d'amour. Jésus invite ses disciples au don total de leur vie, sans calcul ni intérêt humain, avec une confiance sans réserve en Dieu. Les saints accueillent cette invitation exigeante et se mettent, avec une humble docilité, à la suite du Christ crucifié et ressuscité. Leur perfection, dans la logique de la foi parfois humainement incompréhensible, consiste à ne plus se mettre au centre, mais à choisir d'aller à contre-courant en vivant selon l'Evangile. C'est ce qu'ont fait les cinq saints qui sont proposés aujourd'hui, avec grande joie, à la vénération de l'Eglise universelle: Zygmunt Szczesny Felinski, Francisco Coll y Guitart, Jozef Damiaan de Veuster, Rafael Arnáiz Barón, et Marie de la Croix (Jeanne) Jugan. En eux, nous contemplons la réalisation des paroles de l'apôtre Pierre: "Voilà que nous avons tout quitté pour te suivre" (v. 28) et la consolante promesse de Jésus: "personne n'aura quitté, à cause de moi et de l'Evangile, une maison, des frères, des sœurs, une mère, un père, des enfants ou une terre, sans qu'il reçoive, en ce temps déjà, le centuple: ... avec des persécutions, et, dans le monde à venir, la vie éternelle" (vv 29-30).

Zygmunt Szczesny Felinski, Archevêque de Varsovie, fondateur de la Congrégation des Sœurs Franciscaines de la Famille de Marie, a été un grand témoin de la foi et de la charité pastorale à une époque très difficile pour la nation et pour l'Eglise en Pologne. Il s'occupait avec ferveur de la croissance spirituelle de ses fidèles, aidait les pauvres et les orphelins. A l'Académie ecclésiastique de Saint-Pétersbourg, il prit grand soin de la formation des prêtres. En tant qu'Archevêque de Varsovie, il invita avec ferveur tous les fidèles à un renouveau intérieur. Avant l'insurrection de 1863 contre l'annexion russe, il mit en garde le peuple contre une inutile effusion de sang. Quand pourtant l'émeute éclata et que les persécutions s'ensuivirent, il défendit courageusement les opprimés. Sur ordre du tsar russe, il passa vingt ans en exil à Jaroslaw sur la Volga, sans jamais pouvoir rentrer dans son diocèse. Il conserva en toute situation sa foi inébranlable dans la Providence divine et priait ainsi: "Ô, Dieu, protège-nous des tribulations et des inquiétudes de ce monde... multiplie l'amour dans nos cœurs et fais que nous conservions avec la plus profonde humilité la confiance infinie dans Ton aide et dans Ta miséricorde...". Aujourd'hui, que son don de soi à Dieu et aux hommes, empli de confiance et d'amour, devienne un exemple éclatant pour toute l'Eglise.

Saint Paul nous rappelle dans la deuxième lecture que "la Parole de Dieu est vivante et énergique" (He 4, 12). En elle, le Père qui est aux cieux, converse amoureusement avec ses fils de tous les temps (cf. Dei Verbum, n. 21), leur communiquant son amour infini et, de cette manière, les encourageant, les consolant et leur offrant son dessein de salut pour l'humanité et pour chaque personne. Conscient de cela, saint Francisco Coll se consacra avec acharnement à la propager, accomplissant ainsi fidèlement sa vocation dans l'Ordre des Prêcheurs, dans lequel il fit profession. Sa passion était d'aller prêcher, en grande partie de manière itinérante et suivant la forme des "missions populaires" pour annoncer et raviver la Parole de Dieu dans les villages et les villes de la Catalogne, aidant ainsi les personnes à une rencontre profonde avec Lui. Une rencontre qui porte à la conversion du cœur, à recevoir avec joie la grâce divine et à maintenir un dialogue constant avec Notre Seigneur par la prière. Pour lui, son activité d'évangélisation comprenait un grand dévouement au Sacrement de la Réconciliation, une emphase remarquable sur l'Eucharistie et une insistance constante sur la prière. Francisco Coll atteignait le cœur des autres parce qu'il transmettait ce que lui-même vivait intérieurement avec passion, ce qui brûlait ardemment dans son cœur: l'amour du Christ, son dévouement total à Lui. Pour que la semence de la Parole de Dieu rencontre un terrain fertile, Francisco fonda la Congrégation des Sœurs Dominicaines de l'Annonciation, dans le but de donner une éducation intégrale aux enfants et aux jeunes, de façon à ce qu'ils puissent découvrir la richesse insondable qu'est le Christ, l'ami fidèle qui ne nous abandonne jamais ni ne se lasse d'être à nos côtés, renforçant notre espérance avec sa Parole de vie.

Jozef De Veuster, qui reçut le nom de Damiaan dans la Congrégation des Sacrés Cœurs de Jésus et de Marie, quitta la Flandre, son pays natal, en 1863, à l'âge de 23 ans, pour annoncer l'Évangile à l'autre bout du monde, sur les îles Hawaï. Son activité missionnaire, qui l'a tellement rempli de joie, atteint son sommet dans la charité. Non sans peur et sans répugnance, il fit le choix d'aller sur l'île de Molokai au service des lépreux qui s'y trouvaient, abandonnés de tous; c'est ainsi qu'il s'exposa à la maladie dont ils souffraient. Il se sentait chez lui avec eux. Le serviteur de la Parole devint ainsi un serviteur souffrant, lépreux parmi les lépreux, au cours des quatre dernières années de sa vie. Pour suivre le Christ, le Père Damien n'a pas seulement quitté sa patrie, mais a également mis en jeu sa santé: c'est pour cela - comme le dit la parole de Jésus qui a été annoncée dans l'Evangile d'aujourd'hui - qu'il a reçu la vie éternelle (cf. Mc 10, 30). En ce 20 anniversaire de la canonisation d'un autre saint belge, le Frère Mutien-Marie, l'Église en Belgique est unie une nouvelle fois pour rendre grâce à Dieu pour l'un de ses fils reconnu comme un authentique serviteur de Dieu. Nous nous souvenons devant cette noble figure que c'est la charité qui fait l'unité: elle l'enfante et la rend désirable. À la suite de saint Paul, saint Damien nous entraîne à choisir les bons combats (cf. 1 Tm 1, 18), non pas ceux qui portent la division, mais ceux qui rassemblent. Il nous invite à ouvrir les yeux sur les lèpres qui défigurent l'humanité de nos frères et appellent encore aujourd'hui, plus que notre générosité, la charité de notre présence servante.

En revenant à l'Evangile d'aujourd'hui, à la figure du jeune qui présente à Jésus son désir d'être bien plus qu'un bon exécuteur des devoirs que lui imposent la loi, répond la figure de Frère Rafael, canonisé aujourd'hui, mort à vingt-sept ans comme Oblat de la Trappe de San Isidro de Dueñas. Même s'il était de famille aisée et, comme il le disait lui-même, d'"âme un peu rêveuse", ses rêves ne se dissipèrent pas devant l'attachement aux biens matériels et à d'autres buts que la vie du monde propose parfois avec grande insistance. Il répondit oui à la proposition de suivre Jésus, de manière immédiate et décidée, sans limites ni conditions. De cette manière, il entreprit un chemin qui, du moment où il se rendit compte dans le Monastère, qu'il "ne savait pas prier", le porta en quelques années au sommet de sa vie spirituelle qu'il relate avec une grande simplicité et un grand naturel dans de nombreux écrits. Frère Rafael, encore proche de nous, continue à nous offrir par son exemple et son œuvre un parcours attractif, en particulier pour les jeunes qui ne se contentent pas facilement, mais aspirent à la plénitude de la vérité, à la plus indicible joie que l'on atteint pour l'amour de Dieu. "Vie d'amour... C'est là la seule raison de vivre" dit le nouveau Saint. Et il insiste: "De l'amour de Dieu provient toute chose". Que le Seigneur écoute avec bienveillance l'une des dernières prières de Saint Rafael Arnáiz, lorsqu'il lui remit toute sa vie en suppliant: "Prends moi et donne-Toi au monde". Qui se donne pour ranimer la vie intérieure des chrétiens d'aujourd'hui. Qui se donne pour que ses frères de la Trappe et les centres monastiques continuent à être le phare qui permet de découvrir le désir intime de Dieu qu'il a placé dans tout cœur humain.

Par son œuvre admirable au service des personnes âgées les plus démunies, Sainte Marie de la Croix est aussi comme un phare pour guider nos sociétés qui ont toujours à redécouvrir la place et l'apport unique de cette période de la vie. Née en 1792 à Cancale, en Bretagne, Jeanne Jugan a eu le souci de la dignité de ses frères et de ses sœurs en humanité, que l'âge a rendus vulnérables, reconnaissant en eux la personne même du Christ. "Regardez le pauvre avec compassion, disait-elle, et Jésus vous regardera avec bonté, à votre dernier jour". Ce regard de compassion sur les personnes âgées, puisé dans sa profonde communion avec Dieu, Jeanne Jugan l'a porté à travers son service joyeux et désintéressé, exercé avec douceur et humilité du cœur, se voulant elle-même pauvre parmi les pauvres. Jeanne a vécu le mystère d'amour en acceptant, en paix, l'obscurité et le dépouillement jusqu'à sa mort. Son charisme est toujours d'actualité, alors que tant de personnes âgées souffrent de multiples pauvretés et de solitude, étant parfois même abandonnées de leurs familles. L'esprit d'hospitalité et d'amour fraternel, fondé sur une confiance illimitée dans la Providence, dont Jeanne Jugan trouvait la source dans les Béatitudes, a illuminé toute son existence. Cet élan évangélique se poursuit aujourd'hui à travers le monde dans la Congrégation des Petites Sœurs des Pauvres, qu'elle a fondée et qui témoigne à sa suite de la miséricorde de Dieu et de l'amour compatissant du Cœur de Jésus pour les plus petits. Que sainte Jeanne Jugan soit pour les personnes âgées une source vive d'espérance et pour les personnes qui se mettent généreusement à leur service un puissant stimulant afin de poursuivre et de développer son œuvre!

Chers frères et sœurs, rendons grâce au Seigneur pour le don de la sainteté qui resplendit aujourd'hui dans l'Eglise avec une beauté singulière. Alors que je salue affectueusement chacun d'entre vous - Cardinaux, Evêques, autorités civiles et militaires, prêtres, religieux et religieuses, fidèles laïcs de différentes nationalités qui prenez part à cette solennelle célébration eucharistique -, je voudrais vous adresser à tous l'appel à vous laisser attirer par les lumineux exemples de ces saints, à vous laisser guider par leurs enseignements pour que toute notre existence devienne un cantique de louange à l'amour de Dieu. Que leur intercession céleste et surtout la protection maternelle de Marie, Reine des Saints et Mère de l'humanité, nous obtienne cette grâce. Amen.

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/homilies/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20091011_canonizzazioni_fr.html

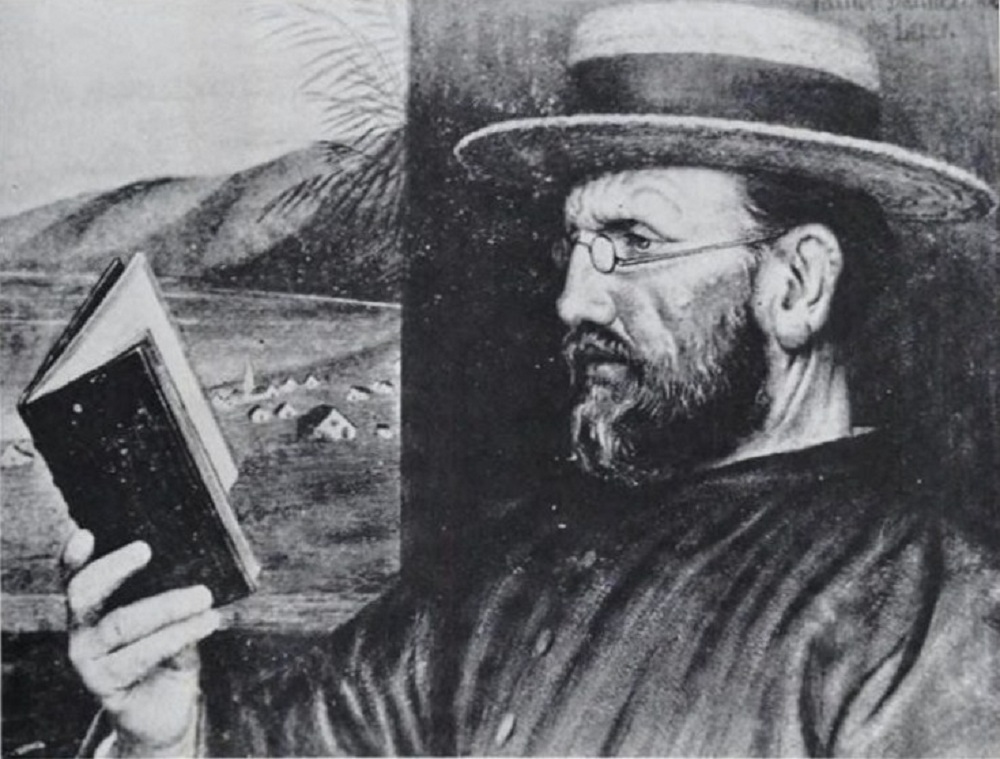

Father

Damien in 1878. Photograph taken by Henry Lyman

Chase (1832–1901). Previously miscredited to Menzies Dickson and

incorrectly dated as 1873, the year he went to Molokai. Boon, Ruben and Patrik

Jaspers (2019). "Father

Damien’s First Photograph at Kalaupapa Reveals Its Secrets". The

Hawaiian Journal of History 53: 151–157. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical

Society.

Père Bernard Couronne, ss. cc.

« Je suis réputé attaqué moi-même de la terrible maladie. Les microbes de la lèpre se sont finalement nichés dans ma jambe gauche et dans mon oreille. Ma paupière commence à tomber. Il m’est impossible de me rendre encore à Honolulu parce que la lèpre devient visible. Bientôt ma figure sera endommagée, je suppose. Étant sûr que la maladie est réelle, je reste calme et résigné et je suis même plus heureux parmi mon monde. Le bon Dieu sait ce qui est mieux pour ma sanctification et dans cette conviction je dis tous les jours un bon fiat voluntas tuas. »

5 octobre 1886

Le Père Damien de Molokaï représente beaucoup pour les Amis des enfants. Il est comme un premier de cordée dans la grande aventure de l’amour de compassion. Il a aimé les lépreux de l’île de Molokaï dont il a choisi d’être le prêtre jusqu’à devenir lui-même lépreux et mourir de cette terrible maladie. Il représente même tant que nous avons choisi de mettre sous sa protection la Fraternité de ceux qui, parmi les Amis des enfants, se sentent appelés à consacrer toute leur vie à Dieu et aux pauvres dans l’Œuvre Points-Cœur.

La brûlure de l’appel

Sur le chemin qui le ramène à sa ferme de Ninde près de Tremelo, Frans De Veuster a le cœur gros. Ce solide paysan flamand vient de laisser son « Jef » au couvent des Sacrés-Cœurs à Louvain (Belgique) où il rejoint son aîné Auguste. Que va dire Anne-Catherine, son épouse, quand elle le verra rentrer seul ? Ces derniers temps, il est vrai, le comportement de Joseph qui vient de fêter ses dix-neuf ans en ce début de janvier 1859, a surpris les siens. Ses parents qui comptaient sur lui pour développer leur commerce de grains l’ont inscrit à l’Ecole moyenne de Braine-le-Comte. Il s’agit d’une « remise à niveau » nécessaire : à quatorze ans, Joseph a arrêté ses études pour aider à la ferme. Malgré le retard et son ignorance du français, le jeune homme intelligent et travailleur progresse rapidement. À Tremelo, cependant, on devine que quelque chose le travaille qui ne correspond guère aux projets des parents. Ainsi, en juillet 1858, à l’occasion de la profession religieuse de sa sœur Pauline – la deuxième de ses sœurs à choisir la vie religieuse – ne laisse-t-il pas percer, dans une lettre, son désir de « suivre » son frère Auguste entré chez les Picpuciens (nom usuel donné aux membres de la Congrégation des Sacrés-Cœurs dont la première maison à Paris fut installée rue de Picpus) à Louvain ?

À Noël de cette même année, les parents de Veuster doivent se rendre à l’évidence : leur fils choisit une autre voie que celle du commerce. « Ce jour [de Noël] m’a confirmé, leur écrit-il, que la volonté du bon Dieu est que je quitte le monde pour embrasser la vie religieuse… Vous ne me le refuserez pas, car c’est Dieu qui appelle et je dois obéir. Auguste m’a écrit que je serais certainement reçu chez eux comme frère de chœur, que je dois me présenter sans délai à son Supérieur pour la nouvelle année, pour commencer sous peu mon noviciat. »

Voilà qui est fait ! La brûlure de l’appel était trop vive pour ce cœur ardent. Il a l’âge de toutes les audaces, de toutes les folies, pensent les gens raisonnables. Il ne le sait pas encore ou du moins est-il incapable de l’exprimer : ce feu qui le pousse de l’avant est celui de « l’ambition de l’Amour ». Elle a sa source dans le Cœur de Dieu. Elle ne le laissera plus jamais en repos.

Anne-Catherine essuie quelques larmes : son « Jef » lui échappe… Elle se souvient. Il n’a pas encore dix ans. Sur le chemin de l’école, avec ses frères et sœurs, il rencontre un jeune mendiant qui, pour apaiser sa faim, se contenterait bien de l’un des gâteaux dorés… « Donnons-lui tout, lance Joseph, ce pauvre garçon est toujours dans le besoin ! » Les gâteaux disparaissent dans la musette du mendiant… Et le déjeuner des enfants De Veuster tourne court. Mais qu’importe, la demi-mesure aurait été bien plus lourde à digérer pour le petit Jef. Cœur sensible, caractère entier, Anne-Catherine l’a vu grandir et devenir un solide jeune homme « adroit et intelligent comme quatre… capable de soulever comme rien des sacs de cent kilos. » C’est sûr, un jour ou l’autre, Jef devait les quitter…

L’offrande du grain de blé

Le 2 février 1859, il prend l’habit et commence son noviciat. Désormais, il est le frère Damien. « Silence, recueillement, prière » sont pour lui les maîtres-mots de ce temps (18 mois) de préparation à la profession religieuse. En cours de route, alertés par son frère Auguste, ses supérieurs découvrent ses capacités intellectuelles et l’admettent parmi ceux qui poursuivront leurs études en vue du sacerdoce. Chaque jour, discrètement, il monte à la tribune de la chapelle où se trouve une peinture de saint François-Xavier. « Je supplie le bon Dieu, confie-t-il à son maître des novices, par l’intercession de saint François Xavier, de m’accorder la grâce d’être, un jour, envoyé en mission. »

Voilà un novice bien sérieux et plein d’idéal ! Damien, pourtant, n’a pas laissé sa gaieté naturelle à la porte du couvent. « Nous rions trop », s’inquiète son frère tandis que le P. Caprais assure qu’il n’a jamais rencontré « un caractère plus sociable et plus aimable ».

C’est à Paris (rue de Picpus), le 7 octobre 1860, qu’il fait sa profession religieuse par laquelle il se consacre aux « Sacrés-Cœurs de Jésus et de Marie au service desquels il veut vivre et mourir. » Après avoir prononcé leurs vœux, les profès se prosternent et on étend sur eux le drap mortuaire. Le Supérieur général qui préside la cérémonie prie : « Dieu, Toi qui veux que morts au monde nous vivions dans le Christ, guide Tes serviteurs sur le chemin du Salut. Que leur vie soit cachée dans le Christ… » Tandis qu’il se relève de la prostration, Damien comprend que nul ne peut aimer et servir comme Jésus s’il ne meurt à lui-même tel le grain de blé mis en terre… Ce rite laisse en lui une empreinte indélébile : aux étapes décisives de son existence, il y fera référence. Et désormais, quand nous l’entendrons évoquer ce qui doit mourir en lui, il nous faudra comprendre qu’il parle de naissance, de résurrection, de « vie en Christ »… Au bas de l’acte de profession, sa signature vigoureuse et appuyée traduit se résolution et laisse deviner une émotion intense. Avec l’ardeur de ses vingt ans, il offre sa vie dans un élan d’amour. Ce don sans retour le greffe sur celui du Christ pour devenir, en Lui, serviteur du dessein d’Amour du Père. La réponse de Damien à l’appel de Dieu n’est pas une décision froide et raisonnée. Ce jeune homme – comme on peut l’être à son âge – est amoureux. Et cet Amour est une passion. Le voilà prêt à supporter mille morts pour aimer à la manière de Jésus. La liturgie de sa profession est un rite nuptial : il décide de mourir à lui-même, de ne plus penser à lui… car, aujourd’hui, il épouse la Passion de Dieu pour le bonheur de l’homme ! « Leur vocation est toute de zèle et d’un zèle en¾ammé, aimait à dire le fondateur de la Congrégation parlant de ses disciples. Ils doivent se sacrifier par zèle pour le Seigneur : ils manqueront à leur vœu le plus essentiel dès le moment où ils voudront vivre pour eux seuls et ne pas travailler au salut de leurs frères. »

Sur ces sentiers évangéliques où, conduit par l’appel de Dieu, il rejoint toute une famille religieuse, la Congrégation des Sacrés-Cœurs de Jésus et de Marie, Damien se sent chez lui, irrévocablement.

L’urgence d’aimer et de servir

Le voilà, frère étudiant, d’abord à Paris et à partir du 25 septembre 1861 à Louvain. « Son amour pour l’étude est extrême, assure un de ses condisciples. Que de courage, que d’efforts pour apprendre. Ses progrès sont rapides car il a un esprit ouvert et un jugement solide. De plus, il possède une puissance de travail peu commune qui lui permet de prolonger ses veilles bien au-delà des limites ordinaires. Il passe avec aisance des études les plus sérieuses au repos de la récréation ou au recueillement. »

Malgré la monotonie et l’austérité de cette vie conventuelle son cœur reste en éveil. Chaque jour, à l’Adoration, il prend dans son intercession les frères et les sœurs de sa famille religieuse en mission en Amérique du Sud, dans les îles du Pacifique, en Californie… Quelle fête quand l’un d’eux s’arrête à Paris ou à Louvain et parle à ses jeunes frères de sa vie missionnaire ! Damien a des fourmis dans les jambes et « le cœur tout brûlant »… Mais il faut retourner aux études !

Son frère, ordonné prêtre le 28 février 1863, est sur la liste du prochain départ pour l’Océanie. Une épidémie de typhus éclate à Louvain et le jeune prêtre se dévoue sans compter au chevet des malades jusqu’au jour où il est, lui-même atteint. « Jamais il ne sera sur pied pour partir vers les îles », pronostique son cadet. L’occasion est trop belle, pourquoi ne partirait-il pas à la place de son aîné ? Avec le consentement de ce dernier, il rédige sa demande. Va-t-on le laisser partir alors qu’il n’a pas encore achevé son séminaire ? Quelques jours après, la réponse du Supérieur général lui parvient : il part !

Le moment est enfin venu pour Damien d’aimer et de servir à la mesure de son cœur totalement livré à l’Amour de Jésus comme celui de Marie !

Le temps presse maintenant. Nous sommes en octobre et le départ est fixé au 1er novembre. Notre futur missionnaire court à Tremelo annoncer la nouvelle. La famille se rassemble autour de son « Jef ». On parle longuement, le cœur serré. Chacun sait, ici, qu’on ne reverra plus ce fils, ce frère très aimé. C’est au pied de Notre-Dame de Montaigu qu’il tient à faire ses adieux à sa mère. « Le sacrifice est grand, écrit-il quelques jours plus tard, pour un cœur qui affectionne tendrement ses parents, sa famille, ses confrères et ce pays qui l’a vu naître. Mais la voix qui nous a invités, qui nous appelle à faire généreusement cette offrande de tout ce que nous avons est la voix de Dieu même. C’est Notre Seigneur qui nous dit comme à ses premiers Apôtres : “Allez enseigner toutes les nations, leur apprenant à observer tous mes commandements. Et voici que je suis avec vous jusqu’à la fin des siècles.” Jésus Christ est d’une manière particulière avec les missionnaires. »

C’est « avec un courage véritablement apostolique », note Damien que le 8 novembre 1863, il embarque avec six frères et dix sœurs de sa Congrégation sur le RW-Wood à Brême (Allemagne). Ils atteindront les îles Hawaï le 19 mars de l’année suivante.

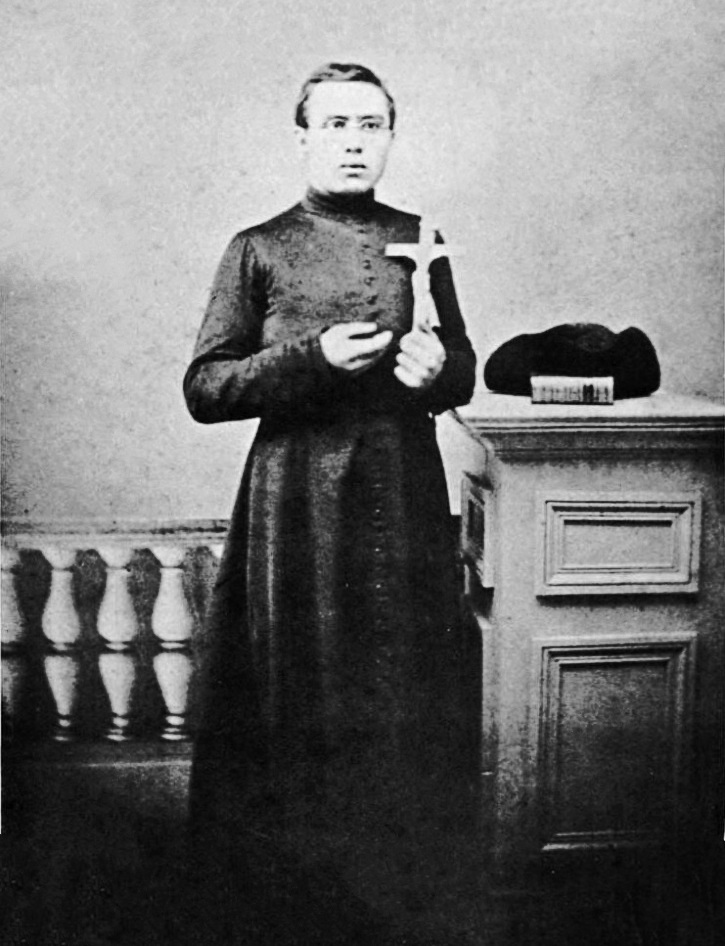

Avant de quitter Paris, Damien a envoyé aux siens une photographie. Devant l’objectif il a pris l’attitude de saint François Xavier présentant la croix du Christ aux païens. Tout un programme !

Avec la fougue – les illusions et les rêves – de sa jeunesse, Damien va de l’avant. Les yeux fixés sur le Christ, il s’efforcera de faire de l’Amour en forme de service son métier d’homme.

À Kalawao

Kalawao, le village des lépreux, est en effervescence. Le Docteur Fitch, médecin attitré de la léproserie, arrive accompagné d’étrangers encore sonnés par la vertigineuse descente du « pali » 2 qui sépare la presqu’île du reste de l’île de Molokaï. La petite troupe se dirige vers l’église à l’autre bout du village.

« La porte de l’enclos de la Mission nous est ouverte par une troupe de joyeux gamins, raconte Charles Stoddard, professeur à l’université Notre-Dame (Indiana, États-Unis), ils sont tous défigurés par la lèpre. La porte de la chapelle est entrebâillée. En un instant, elle est ouverte et un jeune prêtre paraît sur le seuil pour nous souhaiter la bienvenue. Sa soutane est usée et décolorée, ses cheveux ébouriffés comme ceux d’un écolier, ses mains tâchées et durcies par le travail, le visage éclatant de santé, l’allure juvénile… C’est le Père Damien. »

« Son rire bruyant, sa sympathie empressée et le magnétisme contagieux de sa personne » 3 impressionnent l’universitaire et ses compagnons.

Une prompte charité

Lorsque Charles Stoddard lui rend visite en cette fin d’octobre 1884, Damien est parmi les lépreux de Molokaï depuis onze ans. Il y a débarqué un jour de mai 1873. Encore, un coup de tête, aux dires de certains. Cette année-là, Monseigneur Hilaire Maigret, vicaire apostolique des îles Hawaï 4, est venu bénir une église sur l’île voisine où il exerce son sacerdoce depuis une dizaine d’années. Le vieil évêque s’entretient avec ses missionnaires, rassemblés pour l’occasion, de la situation des catholiques lépreux de Molokaï. Depuis 1866, le Gouvernement de l’archipel parque les lépreux sur une langue de terre désolée de l’île. À cette époque, la ségrégation est la seule parade possible contre la maladie. Une fois les lépreux déposés sur le rivage, l’administration se préoccupe fort peu du sort des malades. Un missionnaire passe de temps en temps à Kalawao. C’est trop peu, pense l’évêque. Avant qu’il ait fini de parler, Damien bondit et se propose. Monseigneur Maigret, surpris, accepte. Le Père Damien séjournera quelques semaines à Kalawao, ensuite un autre missionnaire prendra la relève. Damien ne l’entend pas ainsi. Sa décision est prise, définitive comme toujours : « Joseph, mon garçon, se dit-il, en voilà pour la vie ! » Il n’emporte rien avec lui, si ce n’est son bréviaire et son chapelet. Ce samedi 10 mai 1873, Damien se hâte vers ses ouailles de Molokaï avec pour seul bagage, cette compassion de Dieu qu’il a épousée au jour de sa profession religieuse en mettant ses pas dans ceux de Jésus. « Lui aussi, dans sa divine charité, consola les lépreux, écrit-il alors, si je ne puis les guérir comme lui, au moins je puis les consoler. » Ni médecin, ni infirmier, il n’a que sa présence affectueuse et surtout les sacrements de l’Église à offrir à un peuple de moribonds.

Des épousailles dans les larmes

À Honolulu, les journaux protestants, habituellement peu amènes pour la Mission catholique, font l’éloge du Père Damien « qui volontiers s’est offert à vivre avec les lépreux et pour eux » et n’hésitent pas à le proclamer « héros chrétien ». Cependant les premiers contacts sont difficiles : « Leurs doigts de pieds et des mains sont quasiment mangés et exhalent une odeur fétide, leur haleine également empoisonne l’air, raconte-t-il. J’ai beaucoup de peine à m’y habituer… Ils sont hideux à voir », mais, ajoute-t-il aussitôt, « ils ont une âme rachetée au prix du Sang adorable de notre divin Sauveur ! » Alors, comment ne pas les aimer ! Il va de case en case. Il se fait tout à tous à sa manière un peu brouillonne, quelquefois impulsive. « Du matin au soir, je suis au milieu des misères physiques et morales qui navrent le cœur, cependant, je tâche de me montrer toujours gai afin de relever le courage de mes infirmes… Mon plus grand bonheur, ajoute-t-il, est de servir le Seigneur dans ces pauvres enfants malades, repoussés par les autres hommes. » Pas question, de laisser sa place à un autre ! Deux jours seulement après son arrivée à Kalawao, sa résolution est prise : « Vous connaissez ma disposition, écrit-il à ses Supérieurs, je veux me sacrifier à mes pauvres lépreux ». Quelques mois plus tard, il confie à son frère : « Je me fais lépreux avec les lépreux. Quand je prêche, c’est ma tournure “nous autres lépreux”. Puissè-je les gagner tous au Christ comme Saint Paul ! » C’est dire combien il a épousé au nom du Christ la cause des lépreux. La compassion, au prix du « sacrifice de sa vie », abolit les distances entre les êtres : Dieu y célèbre ses noces avec l’humanité.

Une dévorante fécondité

Les visites aux malades, l’accompagnement des mourants ne suffisent pas à l’ardeur dévorante du curé de Kalawao.La lèpre gangrène les corps, elle corrompt également les cœurs.

Les enfants, sans défense, en sont les premières victimes. Damien crée un orphelinat pour les jeunes filles lépreuses plus exposées. Celui des garçons suit peu après. « Depuis quelque mois, raconte-t-il à ses correspondants européens, j’ai un petit orphelinat de jeunes enfants lépreuses, dont une bonne veuve, non-lépreuse, elle, et déjà avancée en âge, est la mère et la cuisinière, notre cuisine se fait ensemble et nous partageons nos provisions… Il est plus ou moins rebutant à la nature d’être entouré de ces malheureux enfants ; mais j’y trouve ma consolation. »

L’œil avisé du paysan flamand ne tarde pas à percevoir d’autres besoins et pas seulement dans le domaine moral ou thérapeutique. Pour Damien de Molokaï tendre la main aux lépreux comme le Christ entraîne plus loin que la catéchèse, la célébration des sacrements ou les soins à domicile. Le meilleur remède contre la lèpre des corps et des cœurs lui paraît être de mobiliser ce qui leur reste d’énergie autour de projets collectifs au profit de tous. Les initiatives se succèdent à perdre haleine : rénovation et assainissement de l’habitat, adduction d’eau, construction d’une route, ouverture d’un magasin, sans oublier l’organisation de courses de chevaux et la création d’une fanfare. Pour autant, le missionnaire de Molokaï ne néglige pas sa tâche pastorale. Bien au contraire ! La lèpre inguérissable détruit les personnes. Toute l’action pastorale de Damien vise à leur redonner le goût de vivre. N’est-ce pas le meilleur remède ? L’église Sainte-Philomène qu’il a dû agrandir devient le centre d’une paroisse dynamique : des équipes s’organisent pour la visite des malades et l’adoration perpétuelle. Les enterrements quasi quotidiens n’ont plus rien de lugubre : la fanfare paroissiale en fait une fête. Cette terre, hier aride, aujourd’hui revit. Aimant les lépreux à la manière du Christ-Serviteur, Damien met en œuvre la puissance de la Résurrection dans ce lieu de mort. Seul l’Amour est capable de faire refleurir des déserts d’humanité.

Une Passion bienheureuse

Damien à Molokaï rend l’Amour plus contagieux que la lèpre. De partout dans le monde, on lui prodigue éloges et encouragements. Les dons et les bénévoles affluent L’humble missionnaire de Molokaï a inventé avant l’heure « l’humanitaire ». Grâce à lui, l’assistance aux lépreux devient une cause mondiale.

Gandhi considérait que « le monde de la politique et du journalisme ne connaît pas de héros dont il peut se glorifier et qui soit comparable au Père Damien de Molokaï. » Il conseillait à ses disciples de « rechercher à quelle source s’alimente un tel héroïsme ». Pourquoi Damien est-il allé s’ensevelir sur ce bout de terre inhospitalière au milieu d’individus repoussants ? La réponse vient, le jour où, en 1885, il se découvre lépreux après avoir longtemps espéré être épargné. « C’est bien par le souvenir d’avoir été couché sous le drap mortuaire, le jour de mes vœux, écrit-il à son évêque, que j’ai bravé le danger de contracter cette terrible maladie en faisant mon devoir ici et tâchant de mourir de plus en plus à moi-même. » Le secret de l’héroïsme de Damien de Molokaï a un nom : Jésus Christ dans le mystère de sa Mort et de sa Résurrection. Jésus Christ dans l’élan de cet Amour manifesté sous le signe du Cœur blessé.

Nul ne peut prétendre communier au mystère pascal de Jésus, vivre sa consécration baptismale, s’il n’a le cœur ouvert par et à la détresse de ses frères. C’est par cette déchirure que s’engouffre la Passion de Dieu pour l’humanité. Le lourd manteau de la lèpre le recouvre comme naguère le drap mortuaire de sa profession religieuse ; il prend l’habit du lépreux et se charge de la croix du Christ. « J’ai accepté cette maladie, confie-t-il à son frère, comme une croix spéciale ; je tâche de la porter comme Simon le Cyrénéen en suivant les traces de son divin Maître. » À la maladie viennent s’ajouter les angoisses de la solitude – il est longtemps le seul prêtre de l’île – les incompréhensions de ses supérieurs, les calomnies et les jalousies. Le voilà, enfin, identifié au « lépreux devant lequel on se voile la face ; maltraité, il s’humilie ; broyé de souffrance, il fait de sa vie un sacrifice, à cause de ses souffrances, à cause de son Amour, il verra la lumière » (Is, 53). Sur les sentiers escarpés de la compassion, dans le cœur de Damien, Dieu consomme ses noces avec les lépreux de Molokaï « pour qu’ils aient la vie en abondance ».

Le missionnaire le plus heureux du monde

La Croix semble l’anéantir. C’est alors qu’il écrit cette phrase incroyable : « La joie et le contentement du cœur que me procurent les Sacrés-Cœurs [de Jésus et de Marie] font que je me crois être le missionnaire le plus heureux du monde ! » Le bonheur des Béatitudes égrenées par Jésus paraît étrange à qui n’en fait pas l’expérience. Celui que l’Église, en écho à la voix du prêcheur de Galilée, proclamera Bienheureux le 4 juin 1995 puis Saint le 11 octobre 2009 sait où il puise cette joie et cette paix. « Notre ministère, note-t-il dans son carnet de retraite, demande un Amour tendre pour notre Seigneur, une force de courage inaltérable dans le travail et une patience invincible dans la souffrance. L’Eucharistie est le Pain des forts dont nous avons besoin. » À qui veut trouver, pour s’y désaltérer, la source de l’héroïque compassion du Père Damien et le secret de son bonheur, il faut le rejoindre dans son adoration matinale précédant la célébration de sa messe. « Sans la présence de notre divin Maître à l’autel de mes pauvres chapelles, je n’aurais pu persévérer à jeter mon sort avec les lépreux de Molokaï… Comme la sainte communion est le Pain de tous les jours, je me sens heureux ! »

Jour après jour, il y rencontre Celui auquel il a donné sa vie et de qui il reçoit tout. Jésus Christ est là dans la puissance de son Mystère de mort et de vie qui se saisit de ce cœur disponible pour aimer. Sur ce rocher perdu du Pacifique, inconnu jusqu’alors, la compassion de Dieu fait des merveilles. Lorsque le père Damien consumé par sa lèpre s’éteint le 15 avril 1889, il est aussi célèbre que Mère Teresa aujourd’hui. Par-delà le siècle qui les sépare une connivence naît entre ces deux champions de la compassion. Le 4 juin 1995, malgré la fatigue qui se lit sur son visage raviné par tant de souffrances sur lesquelles elle s’est penchée, la Mère des mourants de Calcutta est là, sur cette place de Bruxelles, au premier rang, assistant à la célébration de béatification du prêtre lépreux de Molokaï.

Elle entend le Successeur de Pierre proclamer : « Damien est de retour ! Comme un frère aîné, désormais configuré au Christ, il vous montre le chemin de la sainteté et le secret du bonheur ! » Ô toi qui lis ces lignes, puisse son témoignage et sa prière élargir ton cœur aux dimensions du monde. « C’est l’ambition que Dieu propose à chacun, l’ambition d’un Amour sans limites ! » (Cardinal J.-M. Lustiger).

1840 : 3 janvier, Naissance de Joseph de Veuster, au village de Tremelo, en Belgique.

1858 : Joseph entre à l’école moyenne de Braine-le-Comte (Belgique) pour y apprendre le francais.

1859 : 2 février, Joseph de Veuster prend l’habit religieux chez les Pères des Sacrés-Cœurs de Picpus à Louvain, en Belgique. Il prend le nom de Damien et rejoint ainsi son frère Pamphile dans le même Institut.

1863 : Départ pour les îles Hawaï, le 30 octobre

1864 : 4 mai, Ordination sacerdotale en la cathédrale d’Honolulu, à Hawaï.

1873 : Le Père Damien de Veuster est missionnaire dans les diverses îles de l’Archipel des Hawaii dans le Pacifique. Ouverture de la léproserie de Molokaï en 1866.

1873 : 10 mai, entrée du Père Damien à la léproserie de Molokaï.

1884 : En fin de cette année, le Père Damien se découvre lépreux. Alertée par la presse, l’opinion internationale s’émeut du sort des lépreux.

1889 : Le 1er avril, le Père Damien meurt lépreux.

SOURCE : http://www.pointscoeur.org/molokai/Damien_de_Molokai.html

Témoignage sur le Père

Damien de Veuster, l’apôtre des lépreux 1

Par Robert Louis

STEVENSON

INTRODUCTION PAR OMER

ENGLEBERT

Il manquait à Damien

d’être attaqué au point le plus sensible de son honneur sacerdotal.

C’est souvent de la

bouche édentée des dévotes rancies que sortent les pires calomnies contre le

clergé. Celle-ci vint d’un ancien sacristain. Le béat faisait la cour à la

veuve d’un lépreux, dont le Père utilisait le dévouement. Cette vertueuse

personne préparait ses repas, surveillait les fillettes de son orphelinat,

trayait les vaches de son étable. Elle repoussa les avances du dégoûtant

personnage, qui se vengea en clabaudant contre la veuve et le prêtre qu’elle

servait.

L’ordure fût communiquée

à la presse par le docteur Hyde.

Comme certaines feuilles

de canton rapetassent encore parfois cette grossièreté, il faut raconter ce qui

se passa.

Le pasteur Hyde, docteur

en théologie, [...] habitait à Honolulu une maison superbe. C’était un ennemi

fanatique des missionnaires catholiques. Tant que Damien vécut, le pasteur se

borna à diffamer sous le manteau.

Il ne prit la plume

qu’après la mort du Père, quand il apprit qu’à Londres, un Comité, présidé par

le Prince de Galles, se constituait pour perpétuer son nom.

Il écrivit alors à son

confrère, le docteur Gage, la lettre ouverte suivante :

Honolulu, 2 août 1889.

Mon cher Frère,

Pour répondre à votre

enquête sur le Père Damien, que nous avons fort bien connu, je vous dirai notre

surprise à la vue des éloges extravagants que font de lui les journaux, comme

s’il s’agissait d’un grand philanthrope et d’un saint. La vérité est que

c’était un homme grossier, malpropre, entêté et sectaire.

S’il alla à Molokaï, ce

fut de sa propre volonté, car personne ne l’y envoya.

Il n’habitait d’ailleurs

pas dans le quartier des lépreux, avant d’être lui-même atteint de la

lèpre ; mais il circulait en liberté dans l’île, dont un peu moins de la

moitié est réservée aux malades, et très souvent il était à Honolulu.

Il ne fut pour rien dans

les réformes et améliorations réalisées au lazaret, celles-ci ont été l’œuvre

du Comité et du gouvernement qui y pourvurent dans la mesure du possible, selon

les circonstances et les besoins.

Ses relations avec les

femmes ne furent rien moins que pures, et c’est à sa débauche et à son

laisser-aller qu’il dut de contracter la lèpre dont il mourut.

D’autres ont fait de

grandes choses en faveur des lépreux : nos propres pasteurs, les médecins

nommés par le gouvernement, etc., mais ceux-ci n’ont pas été mus, comme les

catholiques, par l’égoïste pensée de gagner ainsi la vie éternelle.

Votre, etc.

Cette lettre parut un peu

partout, produisant d’abord quelques-uns des effets que les ministres en

attendaient.

Pour y parer, de longues

et irréfragables réfutations picpuciennes 2 furent

élaborées et quelques-unes publiées.

Mgr K... lui-même prit la

plume ; il déclara qu’une enquête serrée l’autorisait à se porter caution

de la pureté de son missionnaire et assura que celui-ci, en seize ans, n’avait

point passé deux mois à Honolulu.

Le lépreux Hutchison, qui

était depuis 1876 à Molokaï, se fit l’interprète de tous ses compagnons pour

affirmer que le Révérend Hyde « n’était, des pieds à la tête, qu’un fieffé

menteur ».

Courte appréciation que

le Père Aubert développa et prouva en trois études critiques qui concluaient à

l’innocence de Damien et à la perfidie de son accusateur. Le docteur,

disait-il, avec saint Paul, « est un homme animal, incapable de rien

entendre aux choses qui sont de l’esprit de Dieu », et il en appelait à

Mme Hyde elle-même pour le démontrer. Le Père Aubert établissait aussi qu’aucun

ministre protestant n’avait jamais mis les pieds au lazaret, sauf le Révérend

Pogue, qui avait voulu qu’on parlât de lui dans les journaux. Son unique visite

avait, d’ailleurs, été rapide : « Il se pencha de loin sur quelques

malades, évita prudemment d’entrer dans les cases, et sous la risée des

lépreux, regagna son bateau à toute vitesse. » Il y avait bien eu un

pasteur au lazaret, mais c’était un Canaque lépreux qui y avait résidé parce qu’il

ne pouvait faire autrement. Les exploits de son zèle n’étaient, d’ailleurs, pas

tels qu’ils valussent d’être mentionnés.

* *

Puis, tout à coup, les

Picpuciens cessèrent de défendre leur confrère. Ce n’était plus nécessaire, car

Robert Stevenson venait de répondre au docteur Hyde. Après la réplique du grand

écrivain anglais, on peut dire qu’il ne resta plus rien de la lettre du

pasteur, et peu de chose du pasteur lui-même.

Stevenson vivait à cette

époque à Tahiti. Il passa de longs mois à Honolulu, séjourna huit jours à

Molokaï, fit une enquête approfondie, puis, écrivit une lettre ouverte qui fit

le tour du monde.

L’auteur du Maître

de Ballentrae, de L’île au Trésor et de tant de livres célèbres, a

voulu que ces pages fussent jointes à ses Œuvres complètes. Comme elles

n’ont jamais été traduites en français et qu’elles forment un témoignage absolument

indépendant, nous les analyserons complètement.

LETTRE DE ROBERT LOUIS

STEVENSON

AU PASTEUR HYDE

Sydney, 25 février 1890.

Monsieur, vous vous

souviendrez peut-être que nous nous connaissons, que nous avons échangé des

visites et avons eu des entretiens qui, pour ma part, furent pleins d’intérêt.

Vous m’avez témoigné une courtoisie que je veux reconnaître. Mais il est des devoirs

plus importants que la gratitude et des offenses qui séparent les amis les plus

intimes, à plus forte raison les simples connaissances.

Quand vous m’auriez

empêché de mourir de faim en me donnant plus de pain que je n’en puis manger,

quand vous auriez sacrifié le repos de vos nuits pour veiller mon père mourant,

votre lettre au révérend Gage me relèverait de toute obligation à votre égard.

[...] C’est un devoir

envers l’humanité que j’accomplis en prenant la plume, car son honneur exige

que, jusque dans les coins les plus reculés du monde, Damien soit vengé, et que

le public sache à quoi s’en tenir sur votre compte.

Je commencerai par vous

citer tout au long ; ensuite je passerai au crible vos assertions, tout en

tâchant d’esquisser le portrait du saint disparu que vous avez pris tant

plaisir à calomnier ; puis je vous dirai un éternel adieu.

Après avoir transcrit la

lettre du pasteur Hyde, Stevenson continue.

Pour bien répondre à

votre factum, il est nécessaire que je vous montre tel que je vous connais.

Pourquoi garderais-je des ménagements envers un homme qui ne respecte

rien ? Je suis donc heureux de pouvoir me servir d’une épée nue. Si mes

paroles froissent vos collègues que je respecte et affectionne, qu’ils me

pardonnent en faveur des grands intérêts que je défends. La peine qu’ils en

ressentiront sera d’ailleurs bien légère au regard de celle qu’ils ont éprouvée

en vous lisant. La faute n’est donc pas à moi. Ce n’est pas le bourreau qui

déshonore la famille humaine, c’est le criminel.

L’Église à laquelle vous

appartenez, qui est aussi la mienne et celle de mes ancêtres, avait une

situation prépondérante aux Hawaï. [...] Ce n’est pas ici le lieu de faire le

compte des succès et des échecs des premières missions, ni d’en rechercher les

causes.

Il faut néanmoins

déplorer que dans l’exercice de leur ministère évangélique, trop de ces

missionnaires se soient enrichis. Vous vous étonnerez peut-être d’apprendre

l’émerveillement qui s’empara de mon cocher quand il vit la grande, luxueuse et

confortable maison que vous habitez et le goût exquis qui préside à son

aménagement. Moi-même, j’aurais été fort étonné si, alors, on m’avait dit que

je parlerais un jour de ces détails. C’est vous qui me forcez de m’abaisser à

votre niveau. Mais le public, appelé à trancher notre débat, doit savoir que

votre lettre fut écrite dans une maison qui fait envie aux passants et provoque

leurs réflexions désobligeantes.

Vous n’avez jamais mis le

pied là où vécut et mourut Damien, sinon, splendidement installé comme vous

l’étiez, vous n’eussiez point parlé de lui comme vous l’avez fait. Votre plume

se fût arrêtée d’elle-même.

[...] Votre lettre est

inspirée par la colère, née elle-même de la jalousie. Vous êtes jaloux de ce

que l’héroïsme de Damien ait réalisé ce que votre Église et la mienne a négligé

d’accomplir. Vous avez du remords de cette inertie et de cette bataille perdue.

Je vous dirai – ce sera l’unique compliment que je vous ferai – que, de tous

les sentiments de votre lettre, c’est le seul qui ne soit pas entièrement ignoble.

Seulement, quand quelqu’un réussit où nous avons échoué, quand il va prendre la

place que nous avons désertée, quand il monte sur la brèche et tombe victime de

son héroïsme, le moyen de se réhabiliter soi-même n’est pas de l’accabler

d’attaques ignominieuses. La bataille était perdue à jamais. Par inertie, vous

aviez manqué l’occasion de bien faire. Il vous restait l’occasion de ne point

vous avilir. Celle-là aussi vous l’avez manquée. Vous pouviez garder le silence

et vous avez parlé. Pendant que, couronné de gloire, Damien, succombant à la

tâche, pourrissait sous un toit à porcs, vous, douillettement installé dans

votre home confortable, vous rassembliez d’immondes commérages pour les

répandre dans le public. C’était consommer votre déshonneur.

Stevenson prie le docteur

Hyde de ne pas se formaliser de ce « toit à porcs ». L’expression est

à peine exagérée. Celle « d’homme grossier et malpropre », n’est pas

non plus tout à fait fausse. Et l’écrivain se félicite de pouvoir substituer à

l’image conventionnelle que certains ont répandue, un portrait plus véridique

et non moins admirable du prêtre lépreux.

Vous me demanderez si

j’en suis capable ?

Hélas ! pour mon

malheur, le hasard a voulu que ce fût du Révérend Docteur Hyde, et non pas du

Révérend Père Damien, que je fis jadis la connaissance. Quand j’arrivai au

lazaret, Damien reposait déjà dans son tombeau. Mais j’ai interrogé ceux qui

vécurent avec lui. Certains vénéraient sa mémoire, d’autres, ses anciens

adversaires, ne cherchaient pas à lui tresser des couronnes. C’est des lèvres

de ces derniers que j’ai appris ce que je sais, c’est à leur témoignage peu

suspect que je m’en tiendrai.

Je suis donc allé à

Molokaï que vous n’avez pas visité et dont vous dites qu’un peu moins de

la moitié est réservée aux lépreux.

Stevenson décrit la

configuration physique du lazaret :

Cela vous permettra,

Monsieur, de le situer sur la carte et de voir s’il forme ou non la vingtième

partie de l’île.

Je vous admire de parler

si joyeusement d’un endroit où un attelage de bœufs, avec des câbles de navire,

ne réussirait pas à vous traîner. Ne m’en veuillez point de troubler la

quiétude dont vous jouissez rue Beretania, en vous le décrivant dans toute son horreur.

Le matin où j’y abordai,

deux religieuses débarquèrent avec moi. L’une d’elles pleurait en silence, je

ne pus m’empêcher d’en faire autant. Vous-même, je crois, auriez été touché.

Ces êtres déformés, cette humanité de cauchemar vous eussent, en tout cas, fait

regretter la douceur de vivre qu’on goûte, rue Beretania.

Quand on voit ces visages

qui sont comme des taches hideuses sur le ciel, ces débris humains qui

respirent encore sur leur lit d’hôpital, l’idée de vivre là est de celles qui

vous font reculer d’épouvante comme l’éclat du soleil vous force à cligner les

yeux. C’est l’enfer que de devoir passer son existence en ce lieu.

Je ne suis pas moins

brave qu’un autre, mais je ne puis me reporter au temps que j’y ai vécu – huit

jours et sept nuits ! – sans ressentir la joie de n’y être plus. Sur le

bateau qui me ramenait, malgré moi, ce refrain me poursuivait : De

toutes les contrées connues, c’est la plus désolée.

Cependant, ce que j’ai vu

– des hôpitaux bien installés, des maisons proprettes formant un nouveau

village, une colonie bien tenue – ne ressemblait plus à ce que Damien

découvrit, quand il s’éveilla sous l’arbre où il avait passé sa première nuit.

Il était seul avec la peste comme compagne ! Seul, il allait vivre le

reste de ses jours au milieu de cette pourriture humaine ! [...]

Abandonnant tout espoir, de sa propre main, il refermait sur lui la porte de

son tombeau.

Stevenson cite alors les

extraits suivants du journal qu’il tint à Molokaï. Ils constituent, dit-il,

« la liste des imperfections de Damien, tout ce qu’on peut vraiment lui

reprocher, car ce sont uniquement des protestants, ses adversaires, qui m’ont

renseigné. »

A. – Damien est mort. Là

même où il a tant souffert et travaillé, on ne lui est cependant pas très

reconnaissant. C’était un homme vertueux, me dit l’un, mais fort

touche-à-tout. D’autres déclarent qu’il avait pris les façons de penser et

d’agir des Canaques, ce dont il convenait et riait lui-même.

À ce que je vois, en

dépit de sa sincérité, il n’était pas très populaire.

B. – Quand mourut le

fameux sous-intendant Ragsdale, qui avait réussi à dompter la colonie rebelle,

Damien lui succéda un moment. Cet intérimat révéla son côté faible. Sa manière

était rude, le contrôle qu’il exerçait, insuffisant ; il y eut un relâchement

de la discipline, sa vie même fut menacée. Aussi s’empressa-t-il de

démissionner.

C. – Je commence à me

former une idée de son caractère. C’était, me semble-t-il, un paysan

intelligent, mais peu cultivé et sectaire ; d’esprit ouvert ; capable

d’accepter une réprimande durement donnée et d’en profiter ; d’un cœur

admirablement généreux dans les petites comme dans les grandes choses ;

prêt, tout en grommelant, à donner sa chemise comme à donner sa vie. Il était

indiscret, s’ingérant partout, ce qui ne le rendait pas de commerce

facile ; autoritaire, et cependant dépourvu de véritable autorité, car ses

enfants se moquaient de lui et c’était à force de gâteries qu’il s’en faisait

obéir.

Il avait la manie de

s’occuper de médecine et contribuait à ruiner, chez les malades, leur confiance

dans les médecins officiels. Si cela peut avoir quelque importance dans le

traitement d’une maladie pareille, ce fut là peut-être son plus grand crime.

L’homme se révéla parfaitement dans l’affaire des livres sterling envoyées par

M. Chapman. Il eut, un moment, l’intention de tout dépenser en faveur des

catholiques. On essaya de lui remontrer son erreur. À son habitude il écouta

d’abord avec une parfaite bonhomie et un entêtement absolu. Puis, quand il vit

clair, il reconnut loyalement qu’il s’était trompé et dit à son

interlocuteur : Je vous remercie. C’eût été du vol. Vous m’avez rendu

un grand service, et il modifia sa liste.

Ce portrait est-il

exact ? Il fut, en tout cas, tracé par un vrai psychologue qui était sans

parti pris et avait tous les moyens de s’informer. Si on ne le trouve pas assez

flatté, on se souviendra que les informateurs de Stevenson étaient protestants.

Pour en revenir à la

lettre de Stevenson, elle réfute, point par point, dans sa dernière partie, les

accusations du pasteur Hyde :

Damien était grossier.

C’est possible !

Vous êtes bien bon de vouloir nous apitoyer sur ces pauvres lépreux qui

n’avaient pour ami et pour père qu’un paysan ignorant. Mais vous, qui êtes si

distingué, que n’étiez-vous là pour les charmer par votre culture ?

Puis-je cependant vous rappeler que saint Jean-Baptiste n’était pas très

élégant, que saint Pierre, dont vous chantez les louanges en chaire, était un

pêcheur plein de rudesse et d’entêtement ? La Bible protestante l’appelle

pourtant saint. Le docteur Hyde, lui, n’a rien de grossier ; seulement, le

malheur a voulu qu’à cette époque il restât dans sa belle maison de la rue

Beretania au lieu de venir à Molokaï.

Damien était entêté.

Cette fois encore, je

crois que vous avez raison. Et je bénis Dieu de lui avoir donné sa forte tête

et sa volonté ferme.

Damien était sectaire.

J’ai peu de goût pour les

bigots, parce qu’ils n’en ont pas pour moi. Aussi, si Damien n’avait été qu’un

sectaire et un bigot, s’il ne s’était manifesté que par sa foi étroite et

intransigeante, je l’aurais soigneusement évité pendant sa vie et nous n’en parlerions

pas. Ce qui est admirable, c’est précisément que cette foi ait été chez lui un

pareil instrument du bien, et ait fait de lui le héros de l’humanité qu’admire

le monde entier.

Damien ne fut pas envoyé

à Molokaï, il y alla de son plein gré.

Est-ce que je lis bien,

ou y a-t-il une faute d’impression ? Est-ce là un reproche de votre

part ? J’ai souvent entendu nos ministres nous pousser à imiter le Christ,

dont le sacrifice fut si méritoire parce que volontaire. Le docteur Hyde

serait-il d’un autre avis ?

Damien s’absentait

souvent de Molokaï.

C’est sans doute qu’on

lui en laissait la liberté. Le blâmez-vous d’en avoir usé ?... C’est un

programme bien spartiate qu’on lui eût tracé rue Beretania ! Vous

trouverez peu de gens pour être aussi exigeants que vous !

Damien n’a été pour rien

dans les réformes établies au lazaret.

[...] Ceux que le préjugé

n’aveugle pas, reconnaissent, au contraire, que toutes les réformes doivent

être mises à son compte. Ses réussites et son héroïque acharnement eurent

raison de la négligence et du mauvais vouloir des officiels. Ceux-ci furent

contraints de le suivre et même de le dépasser. Avant lui, peu de chose avait

été fait. Il vint, et son sacrifice éclatant émut le monde entier. Les regards

de l’univers se tournèrent vers Molokaï. Il y attira l’argent, et surtout la

sympathie des cœurs. L’opinion publique exerça son contrôle sur le soin qu’on

prenait des lépreux. C’était tout ce qu’il fallait ; c’était le germe de

toutes les améliorations futures. S’il y eut jamais un homme qui créa des

réformes et mourut pour en assurer le triomphe, ce fut bien lui. Il n’y a pas

une tasse lavée, il n’y a pas une serviette blanchie dans le Bishop’s home,

actuellement si bien tenu, qui ne doive leur propreté à Damien.

Damien n’était pas pur dans

ses rapports avec les femmes, etc.

Où avez-vous pris

cela ? C’est là le genre de propos qu’on tient, rue Beretania ? Dans

cette belle demeure, qu’enviait mon cocher, c’est avec ces histoires