Janani Luwum

De 1924 à 1977

Anglican (Mouvement

Balokole)

Ouganda

L'archevêque Janani

Luwum, archevêque et martyr anglican, était adversaire implacable d'Idi AMIN,

qui l'a fait assassiner.

A partir de 1956, Luwum a

travaillé comme prêtre de paroisse. Il a été élu évêque de l'Ouganda du nord en

1969, et en 1974 il a été choisi archevêque de l'Ouganda, du Rwanda, du Burundi

et du Boga-Zaïre. Il a confronté les injustices et les atrocités du régime

d'Amin presque immédiatement, d'abord par les remontrances privées, et enfin

dans un discours à la radio à Noël, en 1976. Le sermon a été censuré avant

qu'il ne puisse terminer. Luwum a menacé de convoquer une démonstration

publique, et pendant un certain temps, les catholiques et les protestants

étaient d'un front uni derrière lui - un accomplissement rare dans l'Ouganda,

pays très diversifié sur le plan religieux.

Amin a réagi rapidement

et sans merci, et la maison de Luwum a été saccagée. Les évêques anglicans ont

répliqué par une dénonciation cinglante des abus d'Amin. Luwum a été détenu et

a été questionné par Amin lui même. Deux jours plus tard, Luwum a été accusé de

sédition et de trafic d'armes alors qu'il participait à un grand rallye public

à Kampala. Cet événement a donné l'excuse voulue pour une deuxième arrestation,

et à la fin de la journée, Luwum était mort. La cause de sa mort est donnée

comme "accident de voiture," mais il a été révélé par la suite que

Luwum et deux autres ministres du gouvernement ont été tués par coup de feu par

ordre d'Amin. Luwum a immédiatement été accepté comme héro de la résistance à

la tyrannie, et il y a eu de nombreux efforts dans l'église anglicane de le

reconnaître comme saint.

Norman C. Brockman

Bibliographie:

Ewechue, Ralph

(éd.). Makers of Modern Africa [Les créateurs de l'Afrique moderne]

2ème édition. London: Africa Books, 1991.

Lecture supplémentaire:

Ford, Margaret. Janani:

The Making of a Martyr [Janani: la vie d'un martyr] (1978).

SOURCE : http://www.dacb.org/stories/uganda/f-luwum_janani.html

Janani Luwum et ses

compagnons

Janani Luwum naquit en

1922 à Acholi, en Ouganda. Enfant de la première génération de chrétiens

ougandais, convertis par les missionnaires anglais, comme tous ses frères.

Adolescent il avait gardé les brebis et les chèvres qui appartenaient à sa

famille de paysans.

Le jeune Janani,

toutefois, manifesta un tel désir d'apprendre que la possibilité lui fut

offerte d'étudier et de devenir enseignant. À vingt-six ans, lui aussi devint

chrétien, et en 1956 il fut ordonné prêtre de l'Église anglicane du lieu. Élu

évêque de l'Ouganda du Nord en 1969, il fut nommé archevêque de l'Ouganda cinq

ans plus tard, quand déjà le régime dictatorial du général Idi Amin Dada

faisait fureur. Luwum commença à s'exposer en public, contestant la brutalité

de la dictature et se faisant l'écho du mécontentement des chrétiens ougandais

et d'importantes couches de la population.

En 1977, face à la

multiplication des massacres de l'État, l'opposition des évêques se fit

manifeste et vibrante. Le 17 février, quelques jours après qu'Idi Amin Dada eut

reçu une lettre sévère de protestation signée par tous les évêques anglicans,

le régime fit savoir que Luwum avait trouvé la mort dans un accident d'auto en

compagnie de deux ministres du gouvernement ougandais.

À son épouse qui

insistait pour qu'il ne s'opposât pas au dictateur, Luwum avait dit, quelques

heures avant sa mort : « Je suis l'archevêque, je ne peux pas fuir. Puisse-je

voir en tout ce qui m'arrive la main du Seigneur. »

Un médecin, qui avait vu

les corps des trois victimes pendant le changement de la garde, confirma que

tous les trois avaient été assassinés. Par la suite quelques détails ont été

donnés sur les dernières heures de l'archevêque. Il avait été pris par le

centre de recherche de l'État, dépouillé et poussé dans une grande cellule

pleine de prisonniers condamnés à mort. Ces derniers le reconnurent et l'un

d'eux lui demanda de le bénir. Puis les soldats lui rendirent ses vêtements et

son crucifix. Il retourna ensuite dans la cellule, pria avec les prisonniers et

les bénit. Une grande paix et un grand calme descendirent sur eux tous, selon

le témoignage d'un survivant. On dit aussi qu'ils cherchèrent à lui faire

signer une confession. D'autres ont témoigné qu'il priait à haute voix pour ses

gardes-chiourme quand il fut massacré.

D'après le récit d'un

témoin.

Témoins de Dieu, Martyrologe universel, Bayard pp. 148-149

SOURCE : http://www.spiritualite2000.com/page-2297.php

Janani Luwum

His Life.

On 6 January 1948 a young

school teacher, Janani Luwum, was converted to the charismatic Christianity of

the East African Revival, in his own village in Acoli, Uganda. At once he

turned evangelist, warning against the dangers of drink and tobacco, and, in the

eyes of local authorities, disturbing the peace. But Luwum was undeterred by

official censure. He was determined to confront all who needed, in his eyes, to

change their ways before God.

In January 1949 Luwum

went to a theological college at Buwalasi, in eastern Uganda. A year later he

came back a catechist. In 1953 he returned to train for ordination. He was

ordained deacon on St Thomas's Day, 21 December 1955, and priest a year later.

His progress was impressive: after two periods of study in England, he became

principal of Buwalasi. Then, in September 1966, he was appointed Provincial

Secretary of the Church of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Boga-Zaire. It was a

difficult position to occupy, and these were anxious days. But Luwum won a

reputation for creative and active leadership, promoting a new vision with

energy and commitment. Only three years later he was consecrated bishop of

Northern Uganda, on 25 January 1969. The congregation at the open-air Services

included the prime minister of Uganda, Milton Obote, and the Chief of Staff of

the army, Idi Amin.

Amin sought power for

himself. Two years later he deposed Obote in a coup. In government he ruled by

intimidation, violence and corruption. Atrocities, against the Acoli and Langi

people in particular, were perpetrated time and again. The Asian population was

expelled in 1972. It was in the midst of such a society, in 1974, that Luwum

was elected Archbishop of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Boga-Zaire. He pressed

ahead with the reform of his church in time to mark the centenary of the

creation of the Anglican province. But he also warned that the Church should

not conform to "the powers of darkness". Amin cultivated a

relationship with the archbishop, arguably to acquire credibility. For his part,

Luwum sought to mitigate the effects of his rule, and to plead for its victims.

The Anglican and Roman

Catholic churches increasingly worked together to frame a response to the

political questions of the day. Soon they joined with the Muslims of Uganda. On

12 February 1977 Luwum delivered a protest to Amin against all acts of violence

that were allegedly the work of the security services. Church leaders were

summoned to Kampala and then ordered to leave, one by one. Luwum turned to

Bishop Festo Kivengere and said, "They are going to kill me. I am not

afraid". Finally alone, he was taken away and murdered. Later his body was

buried near St Paul's Church, Mucwini.

Amin's state was

destroyed by invading Tanzanian forces in 1979. Amin himself fled abroad and

escaped justice.

"I am prepared to

die in the army of Jesus." Janani Luwum

SOURCE : http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/janani-luwum

Janan

Luwum Burial Site, Kitgum

There are currently three graves: St. Janani Luwum's, his wife Mama Mary Luwum, who passed away in August 2019 at age 93, outliving her husband, who died at age 55, and Ezira Kubwota Ode's, who died on March 30, 2001. In Mucwiini, Chua Kitgum District, Uganda, Archbishop Janani Luwum was born in 1924. Since the Archbishops of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer and William Laud were both killed while in office in 1556 AD and 1645 AD, respectively, he was the first sitting Archbishop in the entire Anglican communion to be martyred in office in the 20th century. The martyrdom on February 16, 1977, served as inspiration for the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral to create a chapel to honor modern martyrs. The first African martyr of the 20th century was named Archbishop Janani Luwum by the Canterbury Cathedral/Church of Uganda in 1978.

JANANI LUWUM

ARCHBISHOP OF UGANDA,

MARTYR (16 FEB 1977)

Janani Luwum was born in

1922. His father was a convert to Christianity. Janani was sent to school and

eventually became a schoolteacher. In 1948 he was converted. He became very

active in the East African revival movement, and became a lay reader, then a

deacon, and then a priest in 1956. He was chosen to study for a year at St

Augustine's College in Canterbury, England. He returned to Uganda, worked as a

parish priest, and then taught at Buwalasi Theological College. He made a

second visit to Britain to study at the London College of Divinity, returning

to Uganda to become Principal of Buwalasi. In 1969 he was consecrated bishop of

Northern Uganda.

The Church in Uganda

began with the deaths of martyrs (see Martyrs of Uganda, 3 June 1886, and James

Hannington and his Companions, Martyrs, 29 October 1885). Around 1900, Uganda

became a British protectorate, with the chief of the Buganda tribe as nominal

ruler, and with several other tribes included in the protectorate. In 1962

Uganda became an independent country within the British Commonwealth, with the

Bugandan chief as president and Milton Obote, of the Lango tribe, as Prime

Minister. In 1966, Obote took full control of the government. In 1971, he was

overthrown by General Idi Amin, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces. Almost

immediately, he began a policy of repression, arresting anyone suspected of not

supporting him. Hundreds of soldiers from the Lango and Acholi tribes were shot

down in their barracks. Amin ordered the expulsion of the Asian population of

Uganda, about 55,000 persons, mostly small shopkeepers from India and Pakistan.

Over the next few years, many Christians were killed for various offenses. A

preacher who read over the radio a Psalm which mentioned Israel was shot for

this in 1972.

In 1974 Janani Luwum he

became Archbishop of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Boga-Zaire. As we have seen,

it was a time of widespread terror. Archbishop Luwum often went personally to

the office of the dreaded State Research Bureau to help secure the release of

prisoners.

Tension between Church

and state worsened in 1976. Religious leaders, including Archbishop Luwum,

jointly approached Idi Amin to share their concern. They were rebuffed. But

Archbishop Luwum continued to attend Government functions. One of his critics

accused him of being on the Government side and he replied: "I face daily

being picked up by the soldiers. While the opportunity is there I preach the

Gospel with all my might, and my conscience is clear before God that I have not

sided with the present Government which is utterly self-seeking. I have been

threatened many times. Whenever I have the opportunity I have told the

President the things the churches disapprove of."

Early in 1977, there was

a small army rebellion that was put down with only seven men dead. However,

Amin determined to stamp out all traces of dissent. His men killed thousands,

including the entire population of Milton Obote's home village. On Sunday, 30

January, Bishop Festo Kivengere preached on "The Preciousness of

Life" to an audience including many high government officials. He

denounced the arbitrary bloodletting, and accused the government of abusing the

authority that God had entrusted to it. The government responded on the

following Saturday (5 February) by an early (1:30am) raid on the home of the

Archbishop, Janani Luwum, ostensibly to search for hidden stores of weapons.

The Archbishop called on

President Amin to deliver a note of protest, signed by nearly all the bishops

of Uganda, against the policies of arbitrary killings and the unexplained

disappearances of many persons. Amin accused the Archbishop of treason,

produced a document supposedly by former President Obote attesting his guilt, and

had the Archbishop and two Cabinet members (both committed Christians) arrested

and held for military trial.

On 16 February, the

Archbishop and six bishops were tried on a charge of smuggling arms. Archbishop

Luwum was not allowed to reply, but shook his head in denial. The President

concluded by asking the crowd: "What shall we do with these

traitors?" The soldiers replied "Kill him now". The Archbishop

was separated from his bishops. As he was taken away Archbishop Luwum turned to

his brother bishops and said: "Do not be afraid. I see God's hand in

this."

The three (the Archbishop

and the two Cabinet members) met briefly with four other prisoners who were

awaiting execution, and were permitted to pray with them briefly. Then the

three were placed in a Land Rover and not seen alive again by their friends.

The government story is that one of the prisoners tried to seize control of the

vehicle and that it was wrecked and the passengers killed. The story believed

by the Archbishop's supporters is that he refused to sign a confession, was

beaten and otherwise abused, and finally shot. His body was placed in a sealed

coffin and sent to his native village for burial there. However, the villagers

opened the coffin and discovered the bullet holes. In the capital city of

Kampala a crowd of about 4,500 gathered for a memorial service beside the grave

that had been prepared for him next to that of the martyred bishop Hannington.

In Nairobi, the capital of nearby Kenya, about 10,000 gathered for another

memorial service. Bishop Kivengere was informed that he was about to be

arrested, and he and his family fled to Kenya, as did the widow and orphans of

Archbishop Luwum.

The following June, about

25,000 Ugandans came to the capital to celebrate the centennial of the first

preaching of the Gospel in their country, among the participants were many who

had abandoned Christianity, but who had returned to their Faith as a result of

seeing the courage of Archbishop Luwum and his companions in the face of death.

by James Kiefer

SOURCE : http://satucket.com/lectionary/janani_luwum.htm

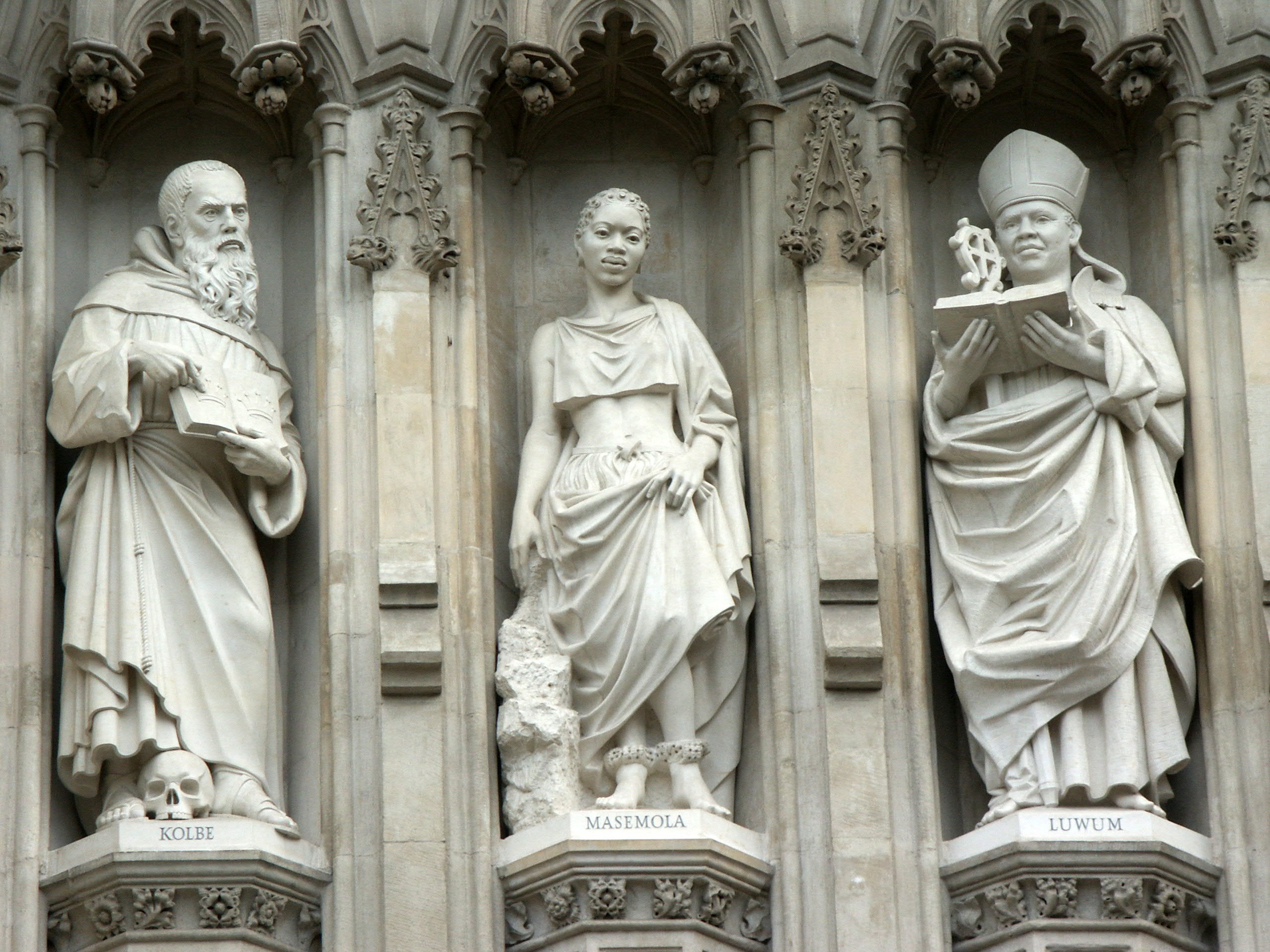

Martyrs

on the façade of Westminster Abbey, London. left to

right: Maximilian Kolbe, Manche

Masemola, and Janani Luwum. See also: en:List of

architectural sculpture in Westminster#Westminster Abbey

Martyrs sur la façade de la Westminster Abbey à Londres : Maximilian Kolb, Manche Masemolae et Janani Luwum

Martyrs on the façade of Westminster Abbey : Janani Luwum.

Martyrs

sur la façade de la Westminster Abbey à Londres : Janani

Luwum

A Modern Martyr :

Janani Jakaliya Luwum (1922-1977)

Anglican Archbishop of

Uganda

Biographical Sketch by

William J. Myers

Ugandans know death well.

With a population of about 24.7 million, it is estimated that some 1.05 million

people suffer from HIV/AIDS. Life Expectancy is estimated at 54 years at birth

(Uganda AIDS commission 2003). Truly, life is difficult in Uganda. Difficult,

yes, but in the 1970's, under General Idi Amin, life was cheap. Amin seized

power in 1971 from President Milton Obote and began a series of mass killings

aimed at "weeding out" enemies. "Bodies were regularly found

floating on Lake Victoria or caught amongst the papyrus, or buried carelessly

in shallow graves. Others were burned in petrol fires or simply thrown into the

bush and left there to rot or be eaten by wild beasts. There was the smell of

death from the marshes. The crocodiles which basked contentedly on the banks of

the River Nile were fat" (Ford 1978. p.67) So many bodies were fed to the

crocodiles that the intake ducts were often clogged with remains at the

hydroelectric plant of Jinja. One of the "enemies" "weeded

out" by Idi Amin was Janani Luwum, the Anglican archbishop of Kampala.

Janani Jakaliya Luwum was

born in 1922 in Northern Uganda. At 10, he began schooling, going on to

Teacher's Training College where he graduated and became a respected teacher.

In 1948 his life changed, though, when he met members of the Balokole

("saved ones") who visited his village. After his conversion

experience, Luwum enrolled in Buwalasi Theological College; and became a priest

in 1956 within the Church of Uganda, a member church of the Anglican Communion.

Luwum studied for a year at Saint Augustine's College and for two more years at

London Divinity College. He subsequently held various posts, including

principal of Buwalasi and provincial secretary. In 1960, he was consecrated as

Bishop of Northern Uganda. He served his diocese so magnificently that in 1974

he was elected Archbishop of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Boga-Zaire. The

archdiocese was centered in Kampala, the capital of Uganda.

When Luwum arrived in

Kampala, it was a frightening place. General Idi Amin's brutal regime was

escalating atrocities. Amin, a convert to Islam, was certainly known to be

pro-Muslim and anti-Christian. Many Christians became targets during Amin's

rule. The volatile situation suggested comparison to the reign of King Mwanga

of Buganda, nearly a century before. Mwanga began martyring Christians around

1885. Joseph Mukasa, a Roman Catholic convert, became King Mwanga's first

victim (Balasundaram 2003).

In August 1976, Amin

declared himself field marshal and life president. The country was beginning to

crumble and church leaders began to unite their voices of discontent. Cardinal

Nsubuga, Sheik Mufti of Uganda, and Archbishop Janani Luwum convened an ecumenical

meeting to discuss the situation within the country. With great trepidation,

they carefully discussed the deteriorating infrastructure. They requested a

meeting with President Amin, but he responded with an angry reprimand about

their conducting a meeting without presidential permission! Given Amin's

deserved reputation, Luwum had to have known that his actions in defense of

justice and his demand for answers made him a marked man, and that his own

murder was a very real possibility.

On January 30, 1977, the

Church of Uganda publicly voiced opposition to Amin. Bishop Festo Kivengere

preached against Amin's misuse of power at the consecration of the Bishop of

West Ankole. A month later a man indicated Luwum as a "possible"

agitator. His home and belongings were ransacked by Amin's troops. On February

16, religious, government, and military leaders were summoned to condemn Luwum

and indict him for various "subversive acts." The vice president

insisted Luwum was given a "fair" trial by a military tribunal. He

was taken to the infamous Nile Hotel, the site of numerous murders and

torturing. The archbishop, who refused to sign a confession of treason, prayed

for his captors as he was undressed and thrown to the floor, whipped, possibly

sodomized, and then, at about 6:00, shot twice in the chest (Mairs 1996. p.84).

Vehicles were then driven over his corpse to suggest a vehicle accident. When

his body was sent home for burial, though, the faithful ripped open the sealed

casket and saw the bullet holes.

Idi Amin's regime was

toppled two years later by Tanzanian forces. Amin sought and received refuge in

Saudi Arabia. Idi Amin finally died, just recently--on August 16, 2003--from

multiple organ failure. The murderous dictator lived 26 years longer than Janani

Luwum, the majority of that time spent in luxury in Saudi Arabia. Amin's legacy

was such that--even in his mortal state before death--President Museveni of

Uganda wanted Amin to stand trial if he returned alive to the country. Contrary

to Amin's epitaph, Christians throughout the world, even years after his

short-lived episcopacy and brutal death, continue to celebrate Janani Luwum's

life. His statue now adorns Westminster Cathedral along with those of other

20th century martyrs. Luwum, unlike other bishops mentioned in this journal,

could not deter Amin's wrath by threats of excommunication or interdict. Armed

only with his faith and his conviction, he risked losing everything--including

his own life--by demanding an end to Amin's murderous rage. Yet he had so much

to live for. He had a devoted wife and loving children. He had the option of a

promising ecclesiastical or academic career (if he had chosen to pursue them

elsewhere), an option not readily available to other priests in Uganda.

Instead, he put his flock and the Gospel of Jesus Christ above all his own

priorities.

"Do not be afraid. I

see God's hand in this." were Janani Luwum's last words to his brother

bishops before his murder (Mission Saint Clare 2003). This statement was a

simple affirmation of faith. Yet it served as a message of comfort and

encouragement in the face of incomprehensible evil. The memory of that

heart-felt farewell constitutes a memorial more enduring than any cast in

bronze or carved from granite.

SOURCE : http://www.orccna.org/publications/np42/martyr.htm

Voir aussi : http://wwwworldwidelife.blogspot.ca/2007/02/in-memory-of-in-memory-of-janani-luwum.html