Saint Patrick

Confesseur, évêque missionnaire en

Irlande (+ 461)

A 16 ans, Patrick, jeune gallois d'une famille chrétienne, est enlevé par des pirates et vendu comme esclave en Irlande. Il y passe six ans puis s'enfuit et retrouve ses parents. Après un séjour en France où il est consacré évêque, il se sent appelé à revenir dans cette Irlande de sa servitude pour l'évangéliser. Il y débarque en 432 et multiplie prédications et conversions dans une population dont, par force, il connaît bien les coutumes et la langue. Au Rock de Cashel, lors d'un sermon demeuré célèbre, il montra une feuille de trèfle: voilà la figure de la Sainte Trinité. Les figures de triades étaient familières à la religion celtique: le trèfle deviendra la symbole de l'Irlande. On pense que la plupart des druides devinrent moines, adoptant la religion chrétienne présentée avec tant de finesse et de conviction. Lorsque meurt Patrick, à Armagh, l'Irlande est chrétienne sans avoir compté un seul martyr et les monastères y sont très nombreux.

"Saint Patrick fut le premier Primat d'Irlande.

Mais il fut surtout celui qui sut mettre dans l'âme irlandaise une tradition

religieuse si profonde que chaque chrétien en Irlande peut à juste titre se

dire l'héritier de saint Patrick. C'était un Irlandais authentique, c'était un

chrétien authentique: le peuple irlandais a su garder intact cet héritage à

travers des siècles de défis, de souffrances et de bouleversements sociaux et

politiques, devenant ainsi un exemple pour tous ceux qui croient que le Message

du Christ développe et renforce les aspirations les plus profondes des peuples

à la dignité, à l'union fraternelle et à la vérité." (discours

au Corps diplomatique - Jean-Paul II - 29 septembre 1979)

- La saint-Patrick, fêtée le 17 mars, est le jour le plus important de l'année pour les irlandais du monde entier. Si officiellement l'Irlande n'a pas de fête nationale, la Saint Patrick en tient lieu. Vidéo: Qu'est-ce que la Saint-Patrick le 17 mars?

Mémoire de saint Patrice (Patrick), évêque. Né en

Grande Bretagne, il fut capturé par des pirates irlandais. Ayant retrouvé sa

liberté, il voulut entrer dans le clergé et retourna en Irlande, décidé à

consacrer sa vie à l'évangélisation de l'île. Ordonné évêque, il s'employa avec

adresse et succès à faire connaître le Christ, en s'adaptant aux conditions

sociales et politiques du pays et il organisa solidement l'Église, jusqu'à sa

mort à Dunum (Down), en 461.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/825/Saint-Patrick.html

Saint Patrick stained glass window from Cathedral of Christ the Light, Oakland, CA. Photo by Sicarr, Wikipedia Commons.

SAINT PATRICE

Apôtre de l'Irlande

(373-464)

Saint Patrice naquit probablement près de Boulogne-sur-Mer; on croit qu'il

était le neveu de saint Martin de Tours, du côté maternel. Quoi qu'il en soit,

ses parents l'élevèrent dans une haute piété. Il avait seize ans, quand il fut

enlevé par des brigands et conduit providentiellement dans le pays dont il

devait être l'apôtre. Patrice profita des cinq ou six ans de sa dure captivité

pour apprendre la langue et les usages de l'Irlande, tout en gardant des troupeaux.

Un jour qu'il vaquait à ses occupations ordinaires, un ange lui apparut sous la

forme d'un jeune homme, lui ordonnant de creuser la terre, et le jeune esclave

y trouva l'argent nécessaire au rachat de sa liberté. Il passa alors en France

sur un navire et se rendit au monastère de Marmoutier, où il se prépara, par

l'étude, la mortification et la prière, à la mission d'évangéliser l'Irlande.

Quelques années plus tard, il alla, en effet, se mettre, dans ce but, à la

disposition du Pape, qui l'ordonna évêque et l'envoya dans l'île que son zèle

allait bientôt transformer.

Son apostolat fut une suite de merveilles. Le roi lutte en vain contre les

progrès de l'Évangile; s'il lève son épée pour fendre la tête du Saint, sa main

demeure paralysée; s'il envoie des émissaires pour l'assassiner dans ses

courses apostoliques, Dieu le rend invisible, et il échappe à la mort; si on

présente à Patrice une coupe empoisonnée, il la brise par le signe de la Croix.

La foi se répandait comme une flamme rapide dans ce pays, qui mérita plus tard

d'être appelée l'île des saints. Patrice avait peu d'auxiliaires; il était

l'âme de tout ce grand mouvement chrétien; il baptisait les convertis,

guérissait les malades, prêchait sans cesse, visitait les rois pour les rendre

favorables à son oeuvre, ne reculant devant aucune fatigue ni aucun péril.

La prière était sa force; il y passait les nuits comme les jours. Dans la

première partie de la nuit, il récitait cent psaumes et faisait en même temps

deux cents génuflexions; dans la seconde partie de la nuit, il se plongeait

dans l'eau glacée, le coeur, les yeux, les mains tournés vers le Ciel, jusqu'à

ce qu'il eût fini les cinquante derniers psaumes.

Il ne donnait au sommeil qu'un temps très court, étendu sur le rocher, avec une

pierre pour oreiller, et couvert d'un cilice, pour macérer sa chair même en

dormant. Est-il étonnant qu'au nom de la Sainte Trinité, il ait ressuscité

trente-trois morts et fait tant d'autres prodiges? Il mourut plus que

nonagénaire, malgré ses effrayantes pénitences.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame,

1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_patrice.html

Statue

of Saint Patrick at the Hill of Tara, Co. Meath, Ireland.

Pomnik św. Patryka na Wzgórzu Tary.

Saint Patrick, évêque

A 16 ans, Patrick, jeune gallois d'une famille

chrétienne, est enlevé par des pirates et vendu comme esclave en Irlande. Il y

passe six ans puis s'enfuit et retrouve ses parents. Après un séjour en France

où il est consacré évêque, il se sent appelé à revenir dans cette Irlande de sa

servitude pour l'évangéliser. Il y débarque en 432 et multiplie prédications et

conversions dans une population dont, par force, il connaît bien les coutumes

et la langue. Au Rock de Cashel, lors d'un sermon demeuré célèbre, il montra

une feuille de trèfle : voilà la figure de la Sainte Trinité. Les figures de

triades étaient familières à la religion celtique : le trèfle deviendra le

symbole de l'Irlande. Lorsque meurt Patrick, à Armagh en 464, l'Irlande est

chrétienne sans avoir compté un seul martyr et les monastères y sont déjà très

nombreux.

Legendari di sancti istoriado uulgar, 1497 : San Patrizio, Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura, Milan

SAINT PATRICE *

Patrice, qui vécut vers

l’an du Seigneur 280, prêchait la passion, de J.-C. au roi des Scots, et comme,

debout devant ce prince, il s'appuyait sur le bourdon qu'il tenait à la main et

qu'il avait mis par hasard sur le pied du roi, il l’en perça avec la pointe.

Or, le roi croyant que le saint évêque faisait cela volontairement et qu'il ne

pouvait autrement recevoir la foi de J.-C. s'il ne souffrait ainsi, il supporta

cela patiemment. Enfin le saint, s'en apercevant, en fut dans la stupeur, et

par ses prières, il guérit le roi et obtint qu'aucun animal venimeux ne put

vivre dans son pays. Ce ne fut pas la seule chose qu'il obtint; il y a plus :

on prétend que les bois et les écorces de cette province servent de

contre-poisons. Un homme avait dérobé à son voisin une brebis et l’avait

mangée; le saint homme avait exhorté. le voleur, quel qu'il fut, à satisfaire

pour le dommage,, et personne ne s'était présenté : au moment où tout le peuple

était rassemblé à l’église, il commanda, au nom de J.-C., que la brebis poussât

en présence de,tous un bêlement dans le ventre de celui qui l’avait mangée. Ce

qui arriva : le coupable fit pénitence, et tous, se gardèrent bien de voler à

l’avenir. Patrice avait la coutume de témoigner une profonde vénération devant

toutes les croix qu'il voyait; mais ayant passé devant une grande et belle

croix sans l’apercevoir; ses compagnons lui demandèrent pourquoi il ne l’avait

ni vue ni saluée : il demanda à Dieu, dans ses prières à qui était cette croix

et entendit une voix de dessous terre qui disait: « Ne vois-tu pas que je suis

un païen qu'on a enterré ici et qui est indigne du signe de la croix? » Alors

il fit enlever la croix de ce lieu.

En prêchant dans

l’Irlande, saint Patrice y opérait très peu de bien ; alors il pria le Seigneur

de montrer un signe qui portât les pécheurs effrayés à faire pénitence. Par

l’ordre donc du Seigneur, il traça quelque part un grand cercle avec son bâton;

la terre s'ouvrit dans toute la circonférence et il y apparut un puits très

grand et très profond. Il fat révélé au bienheureux Patrice que c'était là le

lieu du Purgatoire où quiconque voudrait descendre n'aurait plus d'autre

pénitence à faire et n'aurait plus souffrir pour ses péchés un autre purgatoire

: Que la plupart n'en sortiraient pas, mais que ceux qui en reviendraient,

devraient y être restés depuis un matin jusqu'à l’autre. Or ,beaucoup de ceux

qui entraient n'en revenaient pas **. Longtemps après la mort de saint Patrice,

un homme noble, appelé Nicolas, qui avait commis beaucoup de péchés, en, fit

pénitence et voulut endurer le Purgatoire de saint Patrice. Après s'être

mortifié, comme tous le faisaient, par quinze jours de jeûne, et avoir ouvert

la porte avec une clef qui se gardait dans une abbaye, il descendit dans le

puits en question et trouva, à son côté, une entrée par laquelle il s'avança.

Il y rencontra une chapelle, où entrèrent des moines revêtus d'aubes qui y

célébraient l’office. Ils dirent à Nicolas d'avoir de la constance, parce que

le diable le ferait passer par bien des épreuves. Il demanda quel aide il

pourrait avoir contre cela : les moines lui dirent : « Quand vous vous sentirez

atteint par les peines, écriez-vous à l’instant et dites : J.-C., fils du Dieu

vivant, ayez pitié de moi qui suis un pécheur. » Les moines s'étant retirés,

aussitôt apparurent des démons qui lui dirent de retourner sur ses pas et de

leur obéir, s'efforçant d'abord de le convaincre par ses promesses pleines de

douceur, l’assurant qu'ils auront soin de lui, et qu'ils le ramèneront sain et

sauf en sa maison. Mais comme il ne voulut leur obéir en rien, tout aussitôt il

entendit des cris terribles poussés par différentes bêtes féroces, et des

mugissements comme si tous les éléments fussent ébranlés. Alors plein d'effroi

et tremblant d'une peur horrible, il eut hâte de s'écrier: « J.-C., fils du

Dieu vivant, ayez pitié, de moi qui suis un pécheur. » Et à l’instant ce

tumulte terrible de bêtes féroces s'apaisa, tout à fait. Il passa outre et

arriva en un lieu où il trouva; une foule de démons qui lui dirent : «Penses-tu

nous échapper ? Pas du tout; mais c'est l’heure où tu vas commencer à être

affligé et tourmenté. » Et voici apparaître un feu énorme et terrible; alors

les démons lui dirent : « Si tu ne te mets à notre disposition, nous te

jetterons dans ce feu pour y brûler. » Sur son refus, ils le prirent et le

jetèrent dans ce brasier affreux ; et quand il s'y sentit torturé, il s'écria

de suite : « J.-C., fils... etc. » et aussitôt le feu s'éteignit. De là il vint

en un endroit où il vit des hommes être brûlés vifs et flagellés parles démons

avec des lames de fer rouge jusqu'au point de découvrir leurs, entrailles,

tandis que d'autres, couchés à plat ventre; mordaient la terre de douleur, en

criant : « Pardon! Pardon ! » et les diables les battaient plus cruellement

encore. Il en vit d'autres dont les membres étaient dévorés par des serpents et

auxquels des bourreaux *** arrachaient les entrailles avec des crochets

enflammés. Comme Nicolas ne voulait pas céder à leurs suggestions, il fut jeté

dans le même feu pour endurer de semblables supplices et il fut flagellé avec

des lames pareilles et ressentit les mêmes tourments. Mais quand il se fut

écrié : «J.-C., fils du Dieu vivant, etc. » il fut incontinent délivré de ces

angoisses. On le conduisit ensuite en un lieu où les hommes étaient frits dans

une poêle; où se trouvait une roue énorme garnie de pointes de fer ardentes sur

lesquelles les hommes étaient suspendus par différentes parties du corps ; or,

cette roue tournait avec une telle rapidité qu'elle jetait des étincelles.

Après quoi, il vit une `immense maison où étaient creusées des fosses pleines

de métaux en ébullition, dans lesquelles l’un avait un pied et l’autre deux.

D'autres y étaient enfoncés jusqu'aux genoux, d'autres jusqu'au ventre, ceux-ci

jusqu’à la poitrine, ceux-là jusqu'au col, quelques-uns enfin jusqu'aux yeux.

Mais en parcourant ces endroits, Nicolas invoquait le nom. de Dieu. Il s'avança

encore; et vit un puits très large d'où s'échappait une fumée horrible

accompagnée d'une puanteur insupportable de là sortaient des hommes rouges

comme du fer qui jette des étincelles; mais les démons les ressaisissaient. Et

ceux-ci lui, dirent : « Ce lieu que tu vois, c'est l’enfer, qu'habite notre

maître Beelzébut. Si tu ne te mets à notre disposition, nous te jetterons dans

ce puits or, quand tu y auras été jeté, tu n'auras aucun moyen d'échapper. »

Comme il les écoutait avec mépris, ils le saisirent et le jetèrent dans ce trou

: mais il fut abîmé d'une si véhémente douleur qu'il oublia presque d'invoquer

le nom du Seigneur cependant en revenant à lui : « J.-C, fils, etc.., »

s'écria-t-il du fond du coeur (il n'avait plus de voix), aussitôt il en sortit

sans aucun mal; et toute la multitude dés démons s'évanouit comme réellement

vaincue. Il s'avança et vit en un autre endroit un pont sur lequel il devait

passer. Ce pont était très étroit, poli et glissant comme une glace, au-dessous

coulait un fleuve immense de soufre et de feu. Comme il désespérait absolument

de pouvoir le traverser, toutefois il se rappela la parole qui l’avait délivré

de tant de maux; il s'approcha avec confiance et eu posant un pied sur le pont,

il se mit à dire : « J.-C., fils, etc...» Mais un cri violent l’effraya au

point qu'il put à peine se soutenir; mais il récita sa prière accoutumée et il

demeura rassuré ; après quoi il posa l’autre pied en réitérant les mêmes

paroles et passa sans accident. Il se trouva donc dans une prairie très

agréable à la vue; embaumée par l’odeur suave de différentes fleurs. Alors lui

apparurent deux fort beaux jeunes gens qui le conduisirent jusqu'à une ville de

magnifique apparence et merveilleusement éclatante d'or et de pierres

précieuses. La porte en laissait transpirer une odeur délicieuse. Elle le

délassa si bien qu'il ne paraissait avoir ressenti ni douleur ni puanteur

d'aucune sorte; et les jeunes gens lui dirent que, cette ville était le

paradis. Comme Nicolas voulait y entrer, ils lui dirent encore qu'il devait

d'abord retourner chez ses parents ; que toutefois les démons ne lui

causeraient point de mal, mais qu'à sa vue ils s'enfuiraient effrayés; que

trente jours après, il mourrait en paix, et qu'alors il entrerait en cette cité

comme citoyen à toujours. Nicolas monta donc par où il était descendu, se

trouva sur la terre et raconta tout ce qui lui était arrivé. Trente jours

après, il reposa heureusement dans le Seigneur.

* Les éditions latines

que nous possédons; ne nous donnent pas l’interprétation du nom de ce saint;

voici celle que nous trouvons dans une traduction française du XVe siècle :

« Patrice est dict ainsi

comme saichant. Car par la voulente de nostre Seigneur, il sceut les secretz de

paradis et d'enfer. »

** Thomas de Massingham a

publié dans le Florilegium insulae sanctorum, seu vitae et acta sanctorum

Hiberniae (Paris, 1624, in-4°) un Traité de Henri de Saltery, moine cistercien

irlandais (en 1150) sur le Purgatoire de saint Patrice. Thomas de Massingham ne

s'est pas contenté de donner le texte entier de cet auteur, il l’a augmenté en

intercalant lies récits d'un certain nombre d'auteurs: anciens et modernes qui

ont parlé du Purgatoire de saint Patrice. Il cite des livres liturgiques

anciens, Mathieu Paris, Denys le Chartreux, Raoul Hygedem, Césaire

d'Hirsterbach, Jean Camers, et un primat d'Irlande nommé David Rotho, ainsi que

bien d'autres, qui ont écrit des relations plus ou moins étendues, ou bien

encore des appréciations sur ce sujet. La Patrologie de Migne contient cet

opuscule, tome CLXXX. Bellarmin parle du Purgatoire de saint Patrice dans ses

controversés.

*** Bufo veut dire crapaud,

Buffones au moyen âgé signifiait bouffons ; on ne saurait concevoir comment des

crapauds pourraient arracher des entrailles avec des instruments aigus.

La Légende dorée de Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction, notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de Seine, 76, Paris mdcccci

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome01/052.htm

Saint

Patrick sent to Ireland by the Pope Celestine

I; wall mosaic in St Mary's Cathedral, Kilkenny.

Saint Patrice (Patrick), évêque

et confesseur

Mort en Irlande vers 461.

La date du 17 mars est attestée dans la vie de Ste Gertrude de Nivelles.

Sa fête est répandue au

VIIIe siècle en Irlande, gagne l’Angleterre au Xe. C’est le Pape Urbain VIII

qui l’inscrivit comme mémoire au calendrier romain en 1632, Innocent XI en fit

une fête semi double en 1687, et Pie IX un double en 1859.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960

Quatrième leçon. Patrice,

appelé l’Apôtre de l’Irlande, naquit dans la Grande-Bretagne ; il était fils de

Calphurnius et de Conchessa, que l’on dit avoir été parente de saint Martin,

Évêque de Tours. Dans sa jeunesse, il fut à plusieurs reprises emmené en captivité

par les barbares, qui l’employèrent à garder les troupeaux, et dès lors il

donna des indices de sa sainteté future. En effet, l’âme remplie de foi, de

crainte de Dieu et d’amour, il se levait diligemment avant l’aube, pour aller,

malgré la neige, la gelée et les pluies, offrir à Dieu ses prières : il avait

coutume de le prier cent fois durant le jour et cent fois la nuit. Délivré de

sa troisième servitude, il embrassa la cléricature, et s’appliqua longtemps à

l’étude de l’Écriture sainte. Après avoir parcouru, non sans beaucoup de

fatigues, les Gaules, l’Italie et les îles de la mer Tyrrhénienne, il fut

divinement inspiré d’aller travailler au salut des Irlandais ; ayant reçu du

Pape saint Célestin le pouvoir d’annoncer l’Évangile, il fut sacré évêque, et

se rendit en Hibernie.

Cinquième leçon. Il est

admirable de voir combien cet homme apostolique souffrit de tribulations dans

l’accomplissement de sa mission, que de fatigues et de peines il supporta, que

d’obstacles il eut à surmonter. Mais par le secours de la divine bonté, cette

terre, qui auparavant adorait les idoles, porta bientôt de si heureux fruits à

la prédication de Patrice, qu’elle fut dans la suite appelée l’île des Saints.

Il régénéra des peuples nombreux dans les eaux saintes du baptême ; il ordonna

des Évêques et un grand nombre de clercs ; il donna des règles aux vierges et

aux veuves qui voulaient vivre dans la continence. Par l’autorité du Pontife

romain, il établit l’Église d’Armach métropolitaine de toute l’île, et

l’enrichit de saintes reliques apportées de Rome. Les visions d’en haut, le don

de prophétie, de grands miracles et des prodiges dont Dieu le favorisa,

jetèrent un tel éclat, que la renommée de Patrice se répandit au loin.

Sixième leçon. Malgré la

sollicitude quotidienne que demandaient ses Églises, Patrice persévérait, avec

une ferveur infatigable, dans une oraison continuelle. On rapporte qu’il avait

coutume de réciter chaque jour tout le Psautier, avec les Cantiques et les

Hymnes, et deux cents oraisons ; en outre, il adorait Dieu trois cents fois,

les genoux en terre, et à chaque Heure canoniale, il se munissait cent fois du

signe de la croix. Partageant la nuit en trois parties, il employait la

première à réciter cent Psaumes et à faire deux cents génuflexions ; il passait

la deuxième à réciter les cinquante autres Psaumes, plongé dans l’eau froide,

et le cœur, les yeux, les mains élevées vers le ciel ; il consacrait la

troisième à un léger repos, étendu sur la pierre nue. Plein de zèle pour la

pratique de l’humilité, il travaillait de ses mains, comme avait fait l’Apôtre.

Enfin, épuisé par des fatigues continuelles endurées pour l’Église, illustre

par ses paroles et par ses œuvres, parvenu à une extrême vieillesse, et fortifié

par les divins mystères, il s’endormit dans le Seigneur ; il fut enseveli à

Down, dans l’Ultonie, au Ve siècle de l’ère chrétienne.

Franz Mayer. Saint Patrick prêchant devant les

rois, vitrail, cathédrale de Carlow, Irlande

Stained

glass window in Carlow Cathedral, showing Saint Patrick preaching

to Irish kings

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

C’est l’Apôtre de tout un peuple que l’Église propose aujourd’hui à nos hommages : le grand Patrice, l’illuminateur de l’Irlande, le père de ce peuple fidèle dont le martyre dure depuis trois siècles. En lui resplendit le don de l’apostolat que le Christ a déposé dans son Église, et qui doit s’y perpétuer jusqu’à la consommation des temps. Les divins envoyés du Seigneur se partagent en deux classes. Il en est qui ont reçu la charge de défricher une portion médiocre de la gentilité, et d’y répandre la semence qui germe avec plus ou moins d’abondance, selon la malice ou la docilité des hommes ; il en est d’autres dont la mission est comme une conquête rapide qui soumet à l’Évangile des nations entières Patrice appartient à cette classe d’Apôtres ; et nous devons vénérer en lui un des plus insignes monuments de la miséricorde divine envers les hommes.

Admirons aussi la solidité de son œuvre. C’est au Ve siècle, tandis que l’île des Bretons était encore presque tout entière sous les ombres du paganisme ; que la race franque n’avait pas encore entendu nommer le vrai Dieu ; que l’immense Germanie ignorait profondément la venue du Christ sur la terre, que toutes les régions du Nord dormaient dans les ténèbres de l’infidélité ; c’est avant le réveil successif de tant de peuples, que l’Hibernie reçoit la nouvelle du salut. La parole divine, apportée par le merveilleux apôtre, prospère dans cette île plus fertile encore selon la grâce que selon la nature. Les saints y abondent et se répandent sur l’Europe entière ; les enfants de l’Irlande rendent à d’autres contrées le même service que leur patrie a reçu de son sublime initiateur. Et quand arrive l’époque de la grande apostasie du XVIe siècle, quand la défection germanique est tour à tour imitée par l’Angleterre et par l’Écosse, par le Nord tout entier, l’Irlande demeure fidèle ; et aucun genre de persécution, si habile ou atroce qu’il soit, n’a pu la détacher de la sainte foi que lui enseigna Patrice.

Honorons l’homme admirable dont le Seigneur a daigné se servir pour jeter la semence dans une terre si privilégiée.

Votre vie, ô Patrice,

s’est écoulée dans les pénibles travaux de l’Apostolat ; mais qu’elle a été

belle, la moisson que vos mains ont semée, et qu’ont arrosée vos sueurs !

Aucune fatigue ne vous a coûté, parce qu’il s’agissait de procurer à des hommes

le précieux don de la foi ; et le peuple à qui vous l’avez confié l’a gardé

avec une fidélité qui fera à jamais votre gloire. Daignez prier pour nous, afin

que cette foi, « sans laquelle l’homme ne peut plaire à Dieu [1] », s’empare

pour jamais de nos esprits et de nos cœurs. C’est de la foi que le juste vit

[2], nous dit le Prophète ; et c’est elle qui, durant ces saints jours, nous

révèle les justices du Seigneur et ses miséricordes, afin que nos cœurs se

convertissent et offrent au Dieu de majesté l’hommage du repentir. C’est parce que

notre foi était languissante, que notre faiblesse s’effrayait des devoirs que

nous impose l’Église. Si la foi domine nos pensées, nous serons aisément

pénitents. Votre vie si pure, si pleine de bonnes œuvres, fut cependant une vie

mortifiée ; aidez-nous à suivre de loin vos traces. Priez, ô Patrice, pour

l’Ile sainte dont vous êtes le père et qui vous honore d’un culte si fervent.

De nos jours, elle est menacée encore ; plusieurs de vos enfants sont devenus

infidèles aux traditions de leur père. Un fléau plus dangereux que le glaive et

la famine a décimé de nos jours votre troupeau ; ô Père ! Protégez les enfants

des martyrs, et défendez-les de la séduction. Que votre œil aussi suive jusque

sur les terres étrangères ceux qui, lassés de souffrir, sont allés chercher une

patrie moins impitoyable. Qu’ils y conservent le don de la foi, qu’ils y soient

les témoins de la vérité, les dociles enfants de l’Église ; que leur présence

et leur séjour servent à l’avancement du Royaume de Dieu. Saint Pontife,

intercédez pour cette autre Ile qui fut votre berceau ; pardonnez-lui ses

crimes envers vos enfants ; avancez par vos prières le jour où elle pourra

rentrer dans la grande unité catholique. Enfin souvenez-vous de toutes les

provinces de l’Église ; voire prière est celle d’un Apôtre ; elle trouvera

accès auprès de celui qui vous a envoyé.

[1] Heb. XI, 6.

[2] Habac. II, 4.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Cet apôtre de l’Irlande

(+ 464), à la vie si austère et si merveilleuse, sema en ces régions lointaines

le grain évangélique avec un si heureux succès que, à cause de l’innombrable

armée de saints qu’elle produisit, la verte Erin mérita au moyen âge le beau

titre d’Ile des Saints, gloire que trois siècles de dures persécutions contre

la foi catholique de la part de l’Église anglicane ne purent éclipser. En

considération de la foi vigoureuse de ce peuple de héros, Pie IX, en 1859,

éleva la fête de saint Patrice (qui apparaît toutefois dans les bréviaires

romains dès le XVe siècle) au rite double.

Patrice peut être

vraiment regardé comme le patriarche de l’épiscopat et du monachisme irlandais,

monachisme dont l’histoire eut une répercussion sur toute l’Europe médiévale,

partout où les Scots errants plantèrent leurs tentes et importèrent leurs

traditions. Rome chrétienne a dédié, près de la voie Salaria, une église

nouvelle à ce grand Apôtre des Irlandais. Mais même anciennement, l’hospice

irlandais Scottorum, devenu par la suite l’abbaye SS. Trinitatis, près du Titre

de Saint-Laurent in Damaso, attestait l’élan de foi et d’amour pour Rome

catholique que la prédication de saint Patrice avait imprimé au sentiment

religieux des Irlandais.

La messe est celle du

Commun des Confesseurs Pontifes, Státuit, mais la première collecte est propre.

Si la sainteté est

nécessaire à tous, elle l’est principalement aux supérieurs ecclésiastiques et

à tous ceux qui, dans les desseins de la Providence, sont appelés à fonder ou à

constituer une société quelconque. Ceux qui viennent par la suite doivent se

garder d’en changer l’esprit et les traditions, mais pour cela, il faut que les

fondateurs aient transmis à leur œuvre un feu si puissant de vie intérieure et

de sainteté, que celui-ci enflamme le cœur des lointaines générations de leurs

disciples. C’est en ce sens qu’on peut entendre la parole de l’apôtre, disant

que ce sont les parents qui sont obligés d’amasser un patrimoine pour leurs

enfants, et non pas ceux-ci pour leurs parents.

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

Saint Patrice, délivrez

l’île de notre âme de tous les reptiles venimeux et faites-en une véritable «

île de saints ».

Saint Patrice : Jour de

mort : 17 mars 464. — Tombeau : à Down, en Irlande. Image : On le représente en

évêque, avec des serpents à ses pieds, ou bien avec un trèfle à trois feuilles.

Vie : Saint Patrice est l’apôtre de l’Irlande. « La vie de ce grand homme, qui

unissait à l’obstination celtique une profondeur étonnante de foi, est riche en

événements merveilleux dont on ne peut nier le caractère historique. Ce qui est

encore plus merveilleux, c’est la reconnaissance de la postérité qui a

transformé la biographie du saint en entourant sa personne d’une couronne de

légendes, comme on ne l’a fait que pour peu de saints. On connaît la légende

d’après laquelle il aurait expulsé et fait jeter dans la mer tous les serpents

et toutes les bêtes dangereuses de l’Irlande. Quoi qu’il en soit, c’est un fait

qu’aujourd’hui encore, on ne trouve en Irlande ni serpents, ni taupes, ni

mulots. Aussi cette légende indique sans doute que Patrice, en introduisant le

christianisme, transforma aussi la culture de la terre (Kaulen). Le saint

adopta l’antique usage païen d’allumer un feu sacré dans la nuit de Pâques et

christianisa cet usage. Les moines irlandais l’apportèrent à Rome. De là, il se

répandit dans toute l’Église sous la forme de bénédiction du feu, le

Samedi-Saint.

Pratique. Le saint a fait de la verte Erin, où dominait le culte des idoles, une île des saints. Qu’il daigne continuer cette œuvre dans nos âmes !

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/17-03-St-Patrice-Patrick-eveque-et#nh1

Saint Patrick Mosaic 1 by Boris Anrep. Christ the King

Cathedral, Mullingar. Own Camera Work Peter Gavigan, May 2007

SAINT PATRICE

Voici peut-être une des vies les plus extraordinaires

et les moins connues que l’hagiographie puisse nous présenter. La légende n’a

rien de plus merveilleux que cette histoire. Saint Patrice occupe dans les

Bollandistes une place très considérable.

Patrice n’avait guère que douze ans quand íl fut enlevé

par des pirates et conduit en Hibernie. Là il fut fait berger et garda

les troupeaux de ses maîtres. Six ans se passèrent, et pendant ces six années,

le jeune Patrice, léger et paresseux, fut saisi par l’esprit de prière. Il

s’agenouillait sur la neige et priait, au milieu des champs, entouré des

animaux qui lui étaient confiés. Au bout de six ans, une voix mystérieuse lui

parla et lui dit: Tu vas bientôt revoir ta patrie, Patrice s’échappa, et guidé

par celui qui lui parlait, arriva à un port qu’il ne connaissait pas, y trouva

un navire qui partait, et obtint du pilote une place á bord.

Mais ce navire ayant pris terre dans un lieu inhabité,

la fatigue et la faim saisirent l’équipage qui marchait dans le désert,

cherchant un gîte et la nourriture. Tous ces hommes étaient païens, excepté

Patrice, — « Tu es chrétien, lui dit le pilote, et tu nous laisses périr ! Si

ton Dieu est puissant, invoque son nom sur nous et nous serons sauvés. »

Patrice commença ici la fonction de sa vie. Il pria, des animaux parurent,

qu'on tua et qu’on mangea,

Patrice, revenu dans son pays, fut une seconde fois

enlevé par les pirates. - « Ta captivité ne durera que deux mois », lui dit la

voix intérieure. » En effet, au bout de deux mois il fut délivré.

Mais, rendu pour la seconde fois á sa patrie et á sa

famille, Patrice ne devait pas rester longtemps immobile dans ce repos.

Une nuit, pendant son sommeil, un personnage se dressa

devant lui, tenant un volume à la main. Et sur la première page du volume

étaient écrits ces mots :

Voix

de l’Hibernie.

Et, dans son sommeil, Patrice croit entendre les voix

des bûcherons de Focludum, qui le suppliaient et lui disaient: Jeune homme,

revenez parmi nous; enseignez-nous les voies du Seigneur !

Le lendemain, Patrice raconta á un ami sa vision, et

son confident lui répondit : Tu seras évêque d’Hibernie.

Quelque temps après, Patrice partit avec sa famille

pour l’Armorique. Là son père et sa mère furent égorgés par les barbares. Patrice

fut gardé vivant par eux, comme un esclave agréable à posséder. Il fut pris, puis

vendu, puis arraché à ses nouveaux maîtres par des Gaulois qui venaient de les

rencontrer et de les battre. Enfin, á Bordeaux, des chrétiens rachetèrent

Patrice, qui vint frapper à la porte du monastère de Saint-Martin de Tours.

II est difficile d’imaginer une vie plus agitée, une succession

plus étrange de situations bizarres et d’événements singuliers. Voilà donc

Patrice tant de fois pris, délivré, repris, vendu, transporté et ballotté, qui

passe quatre années dans la vie cénobitique. Cependant, les visions divines lui

montraient toujours l’Hibernie comme le lieu de sa vocation. II entendait,

dit-on, les cris des enfants dans le sein de leurs mères qui l’appelaient en Hibernie.

II quitta le monastère, franchit le détroit, et vint évangéliser la cité

irlandaise de Remair. Mais telle était la voie étrange par laquelle Patrice était

conduit que, malgré ses désirs, sa sainteté, son zèle, et l’appel surnaturel

dont il était l’objet, il échoua complétement. Traité en ennemi, il fut obligé

de repasser le détroit. L’heure n’était pas venue. L’Irlande n’était pas prête.

Toujours appelé, toujours repoussé, Patrice revient en Gaule, où il passe trois

ans sous la direction de saint Gerrnain l’Auxerrois. Ensuite il alla chercher

la solitude de l’île de Lérins où il continua dans la prière les mystérieuses préparations

qu’il avait commencées dans les travaux et dans les captivités.

Enfin saint Germain l’envoya à Rome où il demanda au

pape saint Célestin la bénédiction apostolique, et il reprit á travers la

France le chemin de cette Irlande qui était pour lui la terre promise. Un évêque

d’Angleterre, nommé Amaton, lui donna la consécration épiscopale, et,

accompagné d’Analius, d’Isornius et de plusieurs autres, saint Patrice aborda

en Irlande, pendant l’été de l’an 432.

On voulut le retenir dans les Cornouailles, où il éclata

par plusieurs miracles. Mais le Seigneur lui parla en vision, et l’appela en

Irlande.

Quand il y fut installé, il se rendit á l’assemblée

générale des guerriers de l’Hibernie. A côté d'eux siégeait le collège

druidique. Patrice attaqua de front le centre religieux et le centre politique

de la nation. Devant tous ses ennemis solennellement réunis et groupés, saint

Patrice prêcha la foi.

A dater de ce moment, les merveilles se succèdent avec

une rapidité dont l’hagiographie offre peu d’exemples. Le roi de Dublin, le roi

de Miurow, les sept fils du roi de Connaugth embrassent le christianisme. Cette

Irlande si stérile devint subitement féconde, au delà des espérances du missionnaire.

Cette Irlande, qui avait chassé les envoyés de Dieu, devint tout á coup l’Ile

des Saints. Ce fut dans une grange que saint Patrice célébra la première fois l’office

sur le sol irlandais.

Dans ce pays où il fut autrefois esclave méprisé des

chefs païens et barbares, saint Patrice marche maintenant en conquérant et en

triomphateur. Rois et peuples, tout vient á lui. Rois, peuples et poètes, car l’Irlande

est une des plus antiques patries de la poésie. On prétend que Patrice rencontra

Ossian.

Le barde irlandais finit, dit-on, par christianiser sa

harpe guerrière. L’Homère de l’Hibernie inclina ses vieux héros devant l’étendard du Dieu inconnu. La poésie celtique demanda aux monastères, qui

sortaient du sol foulé par Patrice, leur ombre hospitalière. Alors, dit un vieil

auteur, les chants des bardes devinrent si beaux que les anges de Dieu se

penchaient au bord du ciel pour les écouter.

Cependant, les invasions des pirates désolaient l’Irlande.

Corotic, chef de clan, désolait le troupeau de Patrice. L’évêque lui écrivit une

lettre :

« Patrice, pécheur ignorant, mais couronné évêque en

Hibernie, réfugié parmi les nations barbares, á cause de son amour pour Dieu,

j’écris de ma main ces lettres pour être transmises aux soldats du tyran... La

miséricorde divine que j’aime ne m’oblige-t-elle pas á agir ainsi, pour

défendre ceux-là même qui naguère m’ont fait captif et qui ont massacré les

serviteurs et les servantes de mon père ? » II prédit que la royauté de ses

ennemis sera moins stable que le nuage et la fumée. « En présence de Dieu et de

ses anges, ajoute-t-il, je certifie que l’avenir sera tel que je l’ai prédit. »

Quelques mois après, Corotic, frappé d’aliénation

mentale, mourait dans le désespoir.

Les ennemis de Patrice tombaient morts, ses amis ressuscitaient.

Les tombeaux semblaient un domaine sur lequel il avait droit. La vie et la mort

avaient l’air de deux esclaves qui auraient suivi ses mouvements.

A son arrivée en Irlande, les démons, dit un historien

du douzième siècle, formèrent un cercle dont ils ceignirent l’île entière, pour

lui barrer le passage, Patrice leva la main droite, fit le signe de la croix et

passa outre. Puis il renversa l’idole du Soleil á laquelle les enfants, comme á

l’ancien Molock, étaient offerts en sacrifice.

Quant au célèbre purgatoire de saint Patrice, les avis

sont partagés sur l’authenticité historique de cette grande tradition.

Du sixième au dix-septième siècle il est facile d’en suivre

la trace. Ni le temps ni l’espace n’a arrêté le bruit et l’émotion de ce

mystère : Calderon a fait un drame intitulé le Purgatoire de saint Patrice.

Il s’agit d’une caverne profonde et souterraine où

saint Patrice faisait pénitence. Plusieurs l’y suivirent ; les grands criminels

descendaient par un puits dans ces profondeurs expiatrices, pour y faire en ce

monde leur purgatoire.

La caverne était située dans une petite île du lac

Dearg, dans la province de l’Ulster occidental.

D’après la tradition, les Irlandais dirent un jour á

Patrice :

« Vous annoncez pour l’autre monde de grandes joies ou

de grandes douleurs : mais nous n’avons jamais vu ni les unes ni les autres;

vous parlez, mais nous ne voyons pas. Que sont des paroles ? Nous ne quitterons

nos habitudes et notre religion que si nous voyons de nos yeux les choses que

vous promettez. »

Patrice se mit en prière, et guidé par son ange, arriva

á sa terrible et célèbre caverne, où il vit et montra les scènes de l’autre

monde, reproduites dans celui-ci. Pour séparer ici l’histoire de la légende par

une ligne de démarcation parfaitement authentique, la critique doit se déclarer

impuissante. D’après la tradition, la caverne était divisée : d’un côté

apparaissaient les anges avec un cortège inouï de splendeurs paradisiaques, de

l’autre les spectres, les idoles, et tous les monstres qu’avait adorés l’Irlande

idolâtre suivis des terreurs et des horreurs qui ne se peuvent imaginer. On

enfermait là deux jours les pénitents volontaires qui réclamaient le

Purgatoire, et nul ne sait l’histoire exacte des quarante-huit heures qu’ils y

passaient.

On attribue au bâton de saint Patrice le pouvoir de

chasser les serpents. Ces animaux venimeux sont, à ce qu’il paraît, inconnus en

Irlande, et leur absence est attribuée á une bénédiction particulière, à la bénédiction

du bois que saint Patrice a tenu dans ses mains.

Saint Patrice et Ossian se sont rencontrés sur terre.

L’histoire possède avec certitude les principaux faits de leur vie. Mais il y a

des détails qui restent incertains, comme les contours, quand la nuit tombe. La

chronographie représente saint Patrice une harpe á la main. L’intimité du saint

et du barde est le trésor qu’elle vent confier symboliquement à la mémoire des

Irlandais.

La figure de saint Patrice ressemble un peu à ces navires qu'on voit s’éloigner du rivage. Pendant quelque temps, l’oeil les suit distinctement, mais le ciel et la mer se confondent á l’horizon, et bientôt le navire semble disparaître á la fois dans le ciel et dans la mer confondus.

Ernest HELLO. Physionomie de saints.

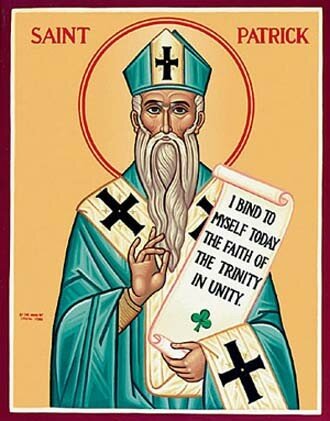

Icône

de saint Patrick portant l'omophore et tenant un trèfle dans sa main droite

Saint Patrick, le trèfle et les druides

Aliénor Goudet - Publié le 16/03/21

Si de nombreux miracles lui sont attribué, il n’y a

que peu de détails sur la vie de saint Patrick. Même son nom et sa date de

naissance sont contestés. Mais une chose est certaine : ce grand saint est à

l’origine de la conversion de l’Irlande au Ve siècle.

Irlande, 432. Sur l’herbe verte de la vaste plaine de

Brega, se tient une foule impressionnante. Paysans et villageois de divers

clans se sont rassemblés. Pourtant certains sont ennemis de longue date. Mais

aucun d’eux ne semble s’en soucier. Toute leur attention est portée sur cet

homme venu de Bretagne. Il s’appelle Patrick et parle remarquablement bien la

langue de cette terre païenne. Les six ans de captivité qu’il y a passé dans sa

jeunesse n’ont jamais quitté sa mémoire. Sa vocation date de cette époque. Le

paganisme de ces peuples peureux l’avait outré.

Mais alors que Patrick prêche la parole, des galops se

font entendre. Un groupe de cinq cavaliers s’arrête près de la foule. Ils sont

vêtus de longues tuniques blanches et de manteau à capuches. Des ossements

d’animaux et autres talismans pendent à leurs ceintures. Leurs barbes et leurs

cheveux descendent jusqu’à leur taille. Lorsque les druides descendent de

leurs montures, la foule opère comme un mouvement de recul. Seul Patrick ne

bronche pas et fixe les ennemis de sa mission. Le plus vieux du groupe s’avance

vers lui.

– C’est donc toi, la langue fourchue qui vient

injurier nos Dieux, dit-il. – On ne peut injurier ce qui n’existe pas, répond

sèchement Patrick. – Prends garde, étranger. Tes blasphèmes ne seront pas

impunis.

Le druide enragé se tourne alors vers la foule qui

recule à nouveau.

– Avez-vous tous perdu la raison ? s’exclame-t-il.

Pauvres fous ! Allez vous repentir à l’arbre de Dagda si vous ne voulez pas que

les mauvais esprits emportent vos enfants.

La foule apeurée recule encore. Certains s’enfuient

déjà et Patrick sent monter en lui un sentiment de colère. C’est là le plus

grand crime de ces croyances païennes : régner par la peur. Avec leur

connaissance des herbes, les druides ont un pouvoir absolu sur les âmes

ignorantes qui ne peuvent échapper à cette emprise.

– Le Dieu unique est mille fois plus puissant que les

vents et corbeaux que vous craignez, déclare Patrick d’une voix forte. C’est

Lui-même qui les a créé et ceux-ci ne se plient qu’à Sa volonté !

La foule cesse de reculer, tandis que Patrick et les

druides s’affrontent du regard. Mais il ne s’arrête pas là. À son tour, il se

tourne vers ceux qui étaient venus l’écouter.

– Vous avez raison d’admirer la nature. Elle est

création de Dieu et l’un des plus beaux cadeaux qu’Il nous accorde. Mais elle

n’est que le fruit de l’amour du Très-Haut pour nous, ses enfants indignes. –

Sornette ! s’écrie le vieux druide. Pourquoi ton Dieu offrirait-il quoi que ce

soit à ceux qui ne l’adorent pas ? – Vos idoles règnent par la peur, mais le

Dieu unique règne par l’amour. Il ne méprise pas ceux qui ne l’adorent pas,

mais les attend. Car il est le père patient et miséricordieux de tous.

La foule se concerte, se rappelant l’histoire du fils

prodigue dont Patrick parlait ce matin même. Le Dieu unique n’attend donc pas

les offrandes et les sacrifices des hommes pour les aimer ? Personne n’a jamais

tenu tête aux druides ainsi, mais les yeux de Patrick ne montrent aucune

crainte. Ce sont plutôt les druides qui s’agitent face à son éloquence. Ivre de

rage, le vieux druide pointe alors un doigt accusateur vers le serviteur de

Dieu.

– Tu clames la grandeur du Dieu unique mais toi aussi

tu adores trois Dieux ! Le père, le fils et le saint esprit.

Patrick se tait quelques instants, laissant le vent

passer. Puis, prenant une grande inspiration, il se penche pour cueillir un

trèfle à ses pieds.

– Voyez ce shamrock, dit-il en le montrant à la

foule. Combien de feuilles comptez-vous ? – Trois mon père, lui répond-on. – Et

combien de trèfles ai-je dans ma main ? – Un seul ! – Ainsi est le Dieu des

chrétiens. Il est seul et unique Dieu, mais se manifeste en trois personnes.

Dieu est le trèfle, et les trois feuilles sont le père, le fils et le saint

Esprit.

Church of Our Lady, Star of the Sea, and St. Patrick, Goleen, County Cork, Ireland. Detail of stained glass of the fourth window of the north wall, depicting St. Patrick.

Also known as

Apostle of Ireland

Maewyn Succat

Patricius

Patrizio

Profile

Kidnapped from

the British mainland around age 16, and shipped to Ireland as

a slave.

Sent to the mountains as a shepherd,

he spent his time in the field in prayer.

After six years of this life, he received had a dream in which he was commanded

to return to Britain; seeing it as a sign, he escaped. He studied in

several monasteries in Europe. Priest. Bishop.

Sent by Pope Celestine

to evangelize England,

then Ireland,

during which his chariot driver was Saint Odran,

and Saint Jarlath was

one of his spiritual students. In 33 years he effectively converted the Ireland.

In the Middle

Ages Ireland became

known as the Land of Saints, and during the Dark Ages its monasteries were

the great repositories of learning in Europe,

all a consequence of Patrick’s ministry.

Born

between 387 and 390 at Scotland as Maewyn

Succat

between 461 and 464 at

Saul, County Down, Ireland of

natural causes

Name Meaning

warlike (Succat – pagan birth

name);

noble (Patricius – baptismal

name)

—

—

Adelaide, Australia, archdiocese of

Armagh, Ireland, archdiocese of

Auckland, New

Zealand, diocese of

Ballarat, Australia, diocese of

Boston, Massachusetts, archdiocese of

Burlington, Vermont, diocese of

Cape

Town, South Africa, archdiocese of

Erie, Pennsylvania, diocese of

Fort

Worth, Texas, diocese of

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, diocese of

Macerata-Tolentino-Recanati-Cingoli-Treia, Italy, diocese of

Madison, Wisconsin, diocese of

Melbourne, Australia, archdiocese of

Mymensingh,

Bangladesh, diocese of

New

York, New

York, archdiocese of

Newark, New

Jersey, archdiocese of

Norwich, Connecticut, diocese of

Ottawa,

Ontario, archdiocese of

Peterborough,

Ontario, diocese of

Port

Elizabeth, South Africa, diocese of

Rapid

City, South

Dakota, diocese of

Sacramento, California, diocese of

Saint

John, New Brunswick, diocese of

Thunder

Bay, Ontario, diocese of

—

bishop driving snakes before

him

Storefront

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Saint Patrick

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Saint Patrick’s Purgatory

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Croagh Patrick

Catholic

World: The Birthplace of Saint Patrick, by J Cashel Hoey

Deer’s

Cry, translated by Kuno Meyer

Epistle

to the Christian Subjects of the Tyrant Coroticus, by Saint Patrick

Golden

Legend, by Jacobus

de Voragine

Handbook

of Christian Feasts and Customs, by Francis X Weiser, SJ

Ireland’s

Apostle and Faith, by Father O’Haire

Legends

of Saint Patrick: Saint Patrick at Tara

Legends

of Saint Patrick: The Disbelief of Milchoor, Saint Patrick’s One

Failure

Legends

of Saint Patrick: The Two Princesses, Fedelm the Red Rose and Ethna

the Fair

Legends

of Saint Patrick: The Baptism of Saint Patrick

Little

Lives of the Great Saints

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Metrical

Life of Saint Patrick, by Saint Fiech

New

Catholic Dictionary: Saint Patrick

New

Catholic Dictionary: Saint Patrick’s Purgatory

Our

Island Saints, by Amy Steedman

Saint

Patrick, Apostle of Ireland, by Monsignor James

B Dollard

Saint

Patrick, The Father of a Sacred Nation, by Father James

F Loughlin

Saint

Patrick, The Life of a Saint, by Monsignor O’Riordan

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Holiness of Saint Patrick, by Father P

F Crudden

Tripartite

Life of Saint Patrick – Part I

Tripartite

Life of Saint Patrick – Part II

Tripartite

Life of Saint Patrick – Part III

Life and Acts of Saint Patrick, by Bishop Jocelin

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of

Saints

Sacred

and Legendary Art, by Anna Jameson

other sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days,

Australian Catholic Truth Society

British Broadcasting Corporation

Cardinal Richard Cushing:

On Saint Patrick

and the Irish People, 1961

Catholic Cuisine: Celtic Knot

Graham Cookies

Catholic Cuisine: Pesto

Tortellini Shamrocks for Saint Patrick’s Day

Encyclopedia Britannica (2008

edition)

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

National Public Radio: How Did

Saint Patrick Get to Be the Patron Saint of Nigeria

Pope John XXIII: Address

on Saint Patrick, 1961

images

audio

Alleluia Audio Books: Life of

Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland, by Father William Bullen Morris

Librivox: Collected Works

video

Life of Saint Patrick, by

Father William Bullen Morris (audio book and image montage)

e-books

Credal Statements of Saint Patrick,

by John Ernest Leonard Oulton

Ireland

and Saint Patrick, by Father William Bullen Morris

Legends

of Saint Patrick, A, by Aubrey De Vere

Life

and Writings of Saint Patrick, The, by Archbishop John Healy

Life

of Saint Patrick, The, by Michael JOseph O’Farrell

Life of Saint Patrick and His Place in

History, The, by John Bagnell Bury

Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland,

by Father William Bullen Morris

Life

of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland, by Mary Francis Cusack

Life

of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland, The, by Patrick Lynch

Patrons of Erin, The, by

William Gouan Todd

Popular

Life of Saint Patrick, A, by Father Michael J O’Farrell

Remains

of Saint Patrick, Apstole of Ireland, by Samuel Ferguson

Rhymed

Life of Saint Patrick, The, by Katharine Tynan

Saint

Patrick, by Abbe Riguet

Saint

Patrick and His Gallic Friends, by Francis Ryan Montmogery

Saint

Patrick and the Early Church of Ireland, by William Maxwell

Blackburn

Saint

Patrick and the Irish, by William Erigena Robinson

Saint Patrick at Tara, by John

William Glover

Saint

Patrick in History, by Father Thomas Joseph Shahan

Saint

Patrick, Apostle of Ireland

Saint

Patrick: His Life and Mission, by Mrs Thomas Concannon

Saint

Patrick: His Life and Teaching, by E J Newell

Saint

Patrick: His Life, His Heroic Virtues, His Labours, and the Fruits of His

Labours, by Father Dean Kinane

Saint Patrick, His Writings and Life,

Saint Patrick, John Davis Newport

Saint

Patrick, The Travelling Man, by Winifred M Letts

Saint

Patrick’s Purgatory, by Thomas Wright

Saint

Patrick’s Purgatory: A Mediaeval Pilgrimage in Ireland, by St John

Drelincourt Seymour

Story of Saint Patrick, Joseph

Snaderson and John Borland Finlay

Story

of Saint Patrick’s Purgatory, The, by Shane Leslie

Succat:

The Story of Sixty Years of the Life of Saint Patrick, by Monsignor

Robert Gradwell

Three Middle Irish Homilies on the Lives

of Saints Patrick, Brigit and Columba, by Whitley Stokes

Tripartite

Life of Patrick, The, by Whitley Stokes

Where was Saint Patrick Born?,

by D Mackintosh MacGregor

Writings

of Saint Patrick, the Apostle of Ireland, The, by Saint Patrick,

Charles Henry Hamilton Wright

Wurra-Wurra:

A Legend of Saint Patrick at Tara, by Curtis Dunham

webseiten auf deutsch

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti in italiano

notitia in latin

nettsteder i norsk

strony w jezyku polskim

spletne strani v slovenšcini

Readings

I came to the Irish people

to preach the Gospel and endure the taunts of unbelievers, putting up with

reproaches about my earthly pilgrimage, suffering many persecutions, even

bondage, and losing my birthright of freedom for the benefit of others. If I am

worthy, I am ready also to give up my life, without hesitation and most

willingly, for Christ’s name. I want to spend myself for that country, even in

death, if the Lord should grant me this favor. It is among that people that I

want to wait for the promise made by him, who assuredly never tells a lie. He

makes this promise in the Gospel: “They shall come from the east and west and

sit down with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.” This is our faith: believers are to

come from the whole world. – from the Confession of

Saint Patrick

Christ shield me this day:

Christ be with me,

Christ within me,

Christ with me,

Christ before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ beside me

Christ to win me,

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ on my right,

Christ on my left,

Christ in quiet,

Christ in danger,

Christ to comfort me and restore me,

Christ when I lie down,

Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of every person who thinks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in the ear that hears me

– Saint Patrick,

from his breast-plate

MLA Citation

“Saint Patrick“. CatholicSaints.Info. 26 December

2020. Web. 17 March 2021. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-patrick/>

Patrick of Ireland B (RM)

Born in Scotland, c. 385-390; died in Ireland c. 461.

"I bind to myself today

The strong virtue of the Incarnation of Christ with his Baptism,

The virtue of His Crucifixion with his burial,

The virtue of His Resurrection with His Ascension,

The virtue of His coming on the Judgment Day.

I bind to myself today

The virtue of the love of the seraphim,

In the obedience of angels,

In the hope of resurrection unto reward,

In prayers of Patriarchs,

In predictions of Prophets,

In preaching of Apostles,

In faith of Confessors,

In purity of holy Virgins,

In deeds of righteous men.

I bind to myself today

The power of Heaven,

The light of the sun,

The brightness of the moon,

The splendor of fire,

The flashing of lightning,

The swiftness of wind,

The depth of the sea,

The stability of the earth,

The compactness of rocks.

I bind to myself today.

God's power to guide me,

God's might to uphold me,

God's wisdom to teach me,

God's eye to watch over me,

God's ear to hear me,

God's word to give me speech,

God's hand to guide me,

God's way to lie before me,

God's shield to shelter me,

God's host to secure me,

Against the snares of demons,

Against the seductions of vices,

Against the lusts of nature,

Against everyone who meditates injury to me,

Whether far or near,

Whether few or many.

I invoke today all these virtues

Against every hostile, merciless power

Which may assail my body and my soul,

Against the incantations of false prophets,

Against the black laws of heathenism,

Against the false laws of heresy,

Against the deceits of idolatry,

Against every knowledge that binds the soul of man and woman.

Christ, protect me today

Against poison,

Against burning,

Against drowning,

Against death-wound,

That I may receive abundant reward.

Christ be with me,

Christ be before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ be with me,

Christ beside me,

Christ to win me,

Christ to comfort and restore me.

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ at my right,

Christ at my left,

Christ be in the fort,

Christ be in the chariot,

Christ be in the ship,

Christ in quiet,

Christ in danger,

Christ in hearts of all that love me,

Christ in mouth of friend and stranger,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.

I bind to myself today

The strong virtue of the Invocation of the Trinity.

I believe the Trinity in the Unity,

The Creator of the Universe. Amen."

--Saint Patrick's Breastplate or Faeth Fiadha (deer's cry).

Note that there are several different versions of this prayer, which is alleged

to be the invocation that led Patrick and his party safely to the confrontation

with the Druids at Tara. It's Irish name, the Deer's Cry, is based on the

legend that Patrick and his eight companions were miraculously turned into deer

to be able to pass unnoticed by the king's guards sent to intercept them.

"I was like a stone lying in the deep mire; and He that is mighty came,

and in His mercy lifted me up, and verily raised me aloft and placed me on the

top of the wall."

--Saint Patrick

The historical Patrick is much more attractive than the Patrick of legend. It

is unclear exactly where Patricius Magonus Sucatus (Patrick) was

born--somewhere in the west between the mouth of the Severn and the Clyde--but

this most popular Irish saint was probably born in Scotland of British origin,

perhaps in a village called Bannavem Taberniae. (Other possibilities are in

Gaul or at Kilpatrick near Dumbarton, Scotland.) His father, Calpurnius, was a

deacon and a civil official, a town councillor, and his grandfather was a

priest.

About 405, when Patrick was in his teens (14-16), he was captured by Irish

raiders and became a slave in Ireland. There in Ballymena (or Slemish) in

Antrim (or Mayo), Patrick first learned to pray intensely while tending his

master's sheep in contrast with his early years in Britain when he "knew

not the true God" and did not heed clerical "admonitions for our

salvation." After six years, he was told in a dream that he should be

ready for a courageous effort that would take him back to his homeland.

He ran away from his owner and travelled 200 miles to the coast. His initial

request for free passage on a ship was turned down, but he prayed, and the

sailors called him back. The ship on which he escaped was taking dogs to Gaul

(France). At some point he returned to his family in Britain, then seems to have

studied at the monastery of Lérins on the Côte d'Azur from 412 to 415.

He received some kind of training for the priesthood in either Britain or Gaul,

possibly in Auxerre, including study of the Latin Bible, but his learning was

not of a high standard, and he was to regret this always. He spent the next 15

years at Auxerre were he became a disciple of Saint Germanus of Auxerre and was

possibly ordained about 417.

The cultus of Patrick began in France, long before Sucat received the noble

title of Patricius, which was immediately before his departure for Ireland

about 431. The center of this cultus is a few miles west of Tours, on the

Loire, around the town of St- Patrice, which is named after him. The strong,

persistent legend is that Patrick not only spent the twenty years after his

escape from slavery there, but that it was his home. The local people firmly

believe that Patrick was the nephew of Saint Martin of Tours and that he became

a monk in his uncle's great Marmoutier Abbey.

Patrick's cultus there reverts to the legend of Les Fleurs de St- Patrice which

relates that Patrick was sent from the abbey to preach the Gospel in the area

of Bréhémont-sur-Loire. He went fishing one day and had a tremendous catch. The

local fishermen were upset and forced him to flee. He reached a shelter on the

north bank where he slept under a blackthorn bush. When he awoke the bush was

covered with flowers. Because this was Christmas day, the incident was

considered a miracle, which recurred each Christmas until the bush was

destroyed in World War I. The phenomenon was evaluated many times and verified

by various observers, including official organizations. His is now the patron

of the fishermen on the Loire and, according to a modern French scholar, the

patron of almost every other occupation in the neighborhood. There is a grotto

dedicated to him at Marmoutier, which contains a stone bed, alleged to have

been his.

It is said that in visions he heard voices in the wood of Focault or that he

dreamed of Ireland and determined to return to the land of his slavery as a

missionary. In that dream or vision he heard a cry from many people together

"come back and walk once more among us," and he read a writing in

which this cry was named 'the voice of the Irish.' (When Pope John Paul II went

to Ireland in 1979, among his first words were that he, too, had heard the

"voice of the Irish.")

In his Confessio Patrick writes: "It was not my grace, but God who

overcometh in me, so that I came to the heathen Irish to preach the Gospel . .

. to a people newly come to belief which the Lord took from the ends of the

earth." Saint Germanus consecrated him bishop about 432, and sent him to

Ireland to succeed Saint Palladius, the first bishop, who had died earlier that

year. There was some opposition to Patrick's appointment, probably from

Britain, but Patrick made his way to Ireland about 435.

He set up his see at Armagh and organized the church into territorial sees, as

elsewhere in the West and East. While Patrick encouraged the Irish to become

monks and nuns, it is not certain that he was a monk himself; it is even less

likely that in his time the monastery became the principal unit of the Irish

Church, although it was in later periods. The choice of Armagh may have been

determined by the presence of a powerful king. There Patrick had a school and

presumably a small familia in residence; from this base he made his missionary

journeys. There seems to have been little contact with the Palladian

Christianity of the southeast.

There is no reliable account of his work in Ireland, where he had been a

captive. Legends include the stories that he drove snakes from Ireland, and

that he described the Trinity by referring to the shamrock, and that he

singlehandedly--an impossible task--converted Ireland. Nevertheless, Saint

Patrick established the Catholic Church throughout Ireland on lasting

foundations: he travelled throughout the country preaching, teaching, building

churches, opening schools and monasteries, converting chiefs and bards, and

everywhere supporting his preaching with miracles.

At Tara in Meath he is said to have confronted King Laoghaire on Easter Eve

with the Christian Gospel, kindled the light of the paschal fire on the hill of

Slane (the fire of Christ never to be extinguished in Ireland), confounded the

Druids into silence, and gained a hearing for himself as a man of power. He

converted the king's daughters (a tale I've recounted under the entry for

Saints Ethenea and Fidelmia. He threw down the idol of Crom Cruach in Leitrim.

Patrick wrote that he daily expected to be violently killed or enslaved again.

He gathered many followers, including Saint Benignus, who would become his

successor. That was one of his chief concerns, as it always is for the

missionary Church: the raising up of native clergy.

He wrote: "It was most needful that we should spread our nets, so that a

great multitude and a throng should be taken for God. . . . Most needful that

everywhere there should be clergy to baptize and exhort a people poor and

needy, as the Lord in the Gospel warns and teaches, saying: Go ye therefore

now, and teach all nations. And again: Go ye therefore into the whole world and

preach the Gospel to every creature. And again: This Gospel of the Kingdom

shall be preached in the whole world for a testimony to all nations."

In his writings and preaching, Patrick revealed a scale of values. He was

chiefly concerned with abolishing paganism, idolatry, and sun-worship. He made

no distinction of classes in his preaching and was himself ready for imprisonment

or death for following Christ. In his use of Scripture and eschatological

expectations, he was typical of the 5th-century bishop. One of the traits which

he retained as an old man was a consciousness of his being an unlearned exile

and former slave and fugitive, who learned to trust God completely.

There was some contact with the pope. He visited Rome in 442 and 444. As the

first real organizer of the Irish Church, Patrick is called the Apostle of

Ireland. According to the Annals of Ulster, the Cathedral Church of Armagh was

founded in 444, and the see became a center of education and administration.

Patrick organized the Church into territorial sees, raised the standard of

scholarship (encouraging the teaching of Latin), and worked to bring Ireland

into a closer relationship with the Western Church.

His writings show what solid doctrine he must have taught his listeners. His

Confessio (his autobiography, perhaps written as an apology against his

detractors), the Lorica (or Breastplate), and the "Letter to the Soldiers

of Coroticus," protesting British slave trading and the slaughter of a

group of Irish Christians by Coroticus's raiding Christian Welshmen, are the

first surely identified literature of the British or Celtic Church.

What stands out in his writings is Patrick's sense of being called by God to

the work he had undertaken, and his determination and modesty in carrying it

out: "I, Patrick, a sinner, am the most ignorant and of least account

among the faithful, despised by many. . . . I owe it to God's grace that so

many people should through me be born again to him."

Towards the end of his life, Patrick made that 'retreat' of forty days on

Cruachan Aigli in Mayo from which the age-long Croagh Patrick pilgrimage

derives. Patrick may have died at Saul on Strangford Lough, Downpatrick, where

he had built his first church. Glastonbury claims his alleged relics. The

National Museum at Dublin has his bell and tooth, presumably from the shrine at

Downpatrick, where he was originally entombed with Saints Brigid and Columba.

The high veneration in which the Irish hold Patrick is evidenced by the common

salutation, "May God, Mary, and Patrick bless you." His name occurs

widely in prayers and blessings throughout Ireland. Among the oldest devotions

of Ireland is the prayer used by travellers invoking Patrick's protection, An

Mhairbhne Phaidriac or The Elegy of Patrick. He is alleged to have promised

prosperity to those who seek his intercession on his feast day, which marks the

end of winter. A particularly lovely legend is that the Peace of Christ will

reign over all Ireland when the Palm and the Shamrock meet, which means when

St. Patrick's Day fall on Passion Sunday.

Most unusual is Well of Saint Patrick at Orvieto, Italy, which was built at the

order of Pope Clement VII in 1537 to provide water for the city during its

periodic sieges. The connection with Saint Patrick comes from the fact that the

project was completed and dedicated by a member of the Sangallo family, a name

derived from the Irish Saint Gall. A common Italian proverb refers to this

exceptionally deep (248 steps to the surface) well: liberal spenders are said

to have pockets as deep as the Well of Patrick (Attwater, Benedictines,

Bentley, Bieler, Bury, Delaney, Encyclopedia, Farmer, MacNeill, Montague,

White).

We are told that often Patrick baptized hundreds on a single day. He would come

to a place, a crowd would gather, and when he told them about the true God, the

people would cry out from all sides that they wanted to become Christians. Then

they would move to the nearest water to be baptized.

On such a day Aengus, a prince of Munster, was baptized. When Patrick had

finished preaching, Aengus was longing with all his heart to become a

Christian. The crowd surrounded the two because Aengus was such an important

person. Patrick got out his book and began to look for the place of the

baptismal rite but his crozier got in the way.

As you know, the bishop's crozier often has a spike at the bottom end, probably

to allow the bishop to set it into the ground to free his hands. So, when

Patrick fumbled searching for the right spot in the book so that he could

baptize Aengus, he absent-mindedly stuck his crosier into the ground just

beside him--and accidentally through the foot of poor Aengus!

Patrick, concentrating on the sacrament, never noticed what he had done and

proceeded with the baptism. The prince never cried out, nor moaned; he simply

went very white. Patrick poured water over his bowed head at the simple words

of the rite. Then it was completed. Aengus was a Christian. Patrick turned to

take up his crozier and was horrified to find that he had driven it through the

prince's foot!

"But why didn't you say something? This is terrible. Your foot is bleeding

and you'll be lame. . . ." Poor Patrick was very unhappy to have hurt

another.

Then Aengus said in a low voice that he thought having a spike driven through

his foot was part of the ceremony. He added something that must have brought

joy to the whole court of heaven and blessings on Ireland:

"Christ," he said slowly, "shed His blood for me, and I am glad

to suffer a little pain at baptism to be like Our Lord" (Curtayne).

In art, Saint Patrick is

represented as a bishop driving snakes before him or trampling upon them. At

times he may be shown (1) preaching with a serpent around the foot of his

pastoral staff; (2) holding a shamrock; (3) with a fire before him; or (4) with

a pen and book, devils at his feet, and seraphim above him (Roeder, White).

Click here to view an anonymous American icon. He is patron of Nigeria (which

was evangelized primarily by Irish clergy) and of Ireland and especially

venerated at Lérins (Roeder, White).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0317.shtml

Icon

of Saint Patrick from Christ the Saviour Church. Christ the Savior Orthodox

Church in Chicago. In the original icon St Patrick is between St Ambrose and St

Gregory the Wonderworker.

Ikona

przedstawiająca św. Patryka z kościoła Chrystusa Zbawiciela w Wayne

St. Patrick, the Apostle of

Ireland

St. Patrick, the Apostle of

Ireland, born at Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton, in Scotland, in the year 387; died

at Saul, Downpatrick, Ireland, 17 March, 461. His parents were Calpurnius and

Conchessa, who were Romans living in Britian in charge of the colonies. As a

boy of fourteen or so, he was captured during a raiding party and taken to

Ireland as a slave to herd and tend sheep. Ireland at this time was a land of

Druids and pagans. He learned the language and practices of the people who held

him.

During his captivity, he

turned to God in prayer. He wrote:“The love of God and his fear grew in me more

and more, as did the faith, and my soul was rosed, so that, in a single day, I

have said as many as a hundred prayers and in the night, nearly the same.” “I

prayed in the woods and on the mountain, even before dawn. I felt no hurt from

the snow or ice or rain.”

Patrick’s captivity

lasted until he was twenty, when he escaped after having a dream from God in

which he was told to leave Ireland by going to the coast. There he found some

sailors who took him back to Britian, where he reunited with his family.

He had another dream in

which the people of Ireland were calling out to him “We beg you, holy youth, to

come and walk among us once more.” He began his studies for the priesthood. He was

ordained by St. Germanus, the Bishop of Auxerre, whom he had studied under for

years.

Later, Patrick was

ordained a bishop, and was sent to take the Gospel to Ireland. He arrived in

Ireland March 25, 433, at Slane. One legend says that he met a chieftain of one

of the tribes, who tried to kill Patrick. Patrick converted Dichu (the

chieftain) after he was unable to move his arm until he became friendly to

Patrick.

Patrick began preaching

the Gospel throughout Ireland, converting many. He and his disciples preached

and converted thousands and began building churches all over the country.

Kings, their families, and entire kingdoms converted to Christianity when

hearing Patrick’s message.

Patrick by now had many

disciples, among them Beningnus, Auxilius, Iserninus, and Fiaac, (all later

canonized as well).

Patrick preached and

converted all of Ireland for 40 years. He worked many miracles and wrote of his

love for God in Confessions. After years of living in poverty, traveling and

enduring much suffering he died March 17, 461.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-patrick/

St.Patrick’s Breastplate

I bind unto myself today

the strong Name of the Trinity,

by invocation of the same,

the Three in One, and One in Three.

I bind this day to me for ever,by power of faith, Christ’s Incarnation ;

his baptism in Jordan river ;

his death on cross for my salvation ;

his bursting from the spicèd tomb ;

his riding up the heavenly way;

his coming at the day of doom:

I bind unto myself today.

I bind unto myself the powerof the great love of

cherubim ;

the sweet “Well done” in judgment hour ;

the service of the seraphim ;

confessors’ faith, apostles’ word,the patriarchs’

prayers, the prophets’ scrolls ;

all good deeds done unto the Lord,

and purity of virgin souls.

I bind unto myself todaythe virtues of the starlit

heaventhe glorious sun’s life-giving ray,

the whiteness of the moon at even,

the flashing of the lightning free,

the whirling wind’s tempestuous shocks,

the stable earth, the deep salt sea,

around the old eternal rocks.

I bind unto myself today

the power of God to hold and lead,

his eye to watch, his might to stay,

his ear to hearken, to my need ;

the wisdom of my God to teach

his hand to guide, his shield to ward ;

the word of God to give me speech,

his heavenly host to be my guard.

Christ be with me,

Christ within me,

Christ behind me,

Christ before me,

Christ beside me,

Christ to win me,

Christ to comfortand restore me.

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ in quiet,

Christ in danger,

Christ in hearts ofall that love me,

Christ in mouth offriend and stranger.

I bind unto myself today

the strong Name of the Trinity,

by invocation of the same,

the Three in One, and One in Three.

Of whom all nature hath creation,

eternal Father, Spirit, Word :

praise to the Lord of my salvation,

salvation is of Christ the Lord.

attributed to St. Patrick (372-466);

trans. Cecil Frances Alexander

(1818-1895), 1889

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/catholicprayers/st-patricks-breastplate/

ST. PATRICK GOING TO TARA. CHAPTER V. ST. PATRICK IN IRELAND. Ireland's crown of thorns and roses; or, The best of her history by the best of her writers, a series of historical narratives that read as entertainingly as a novel, 1904, (Chicago, M. A. Donohue & co.

St. Patrick

Apostle of Ireland,