Mathias

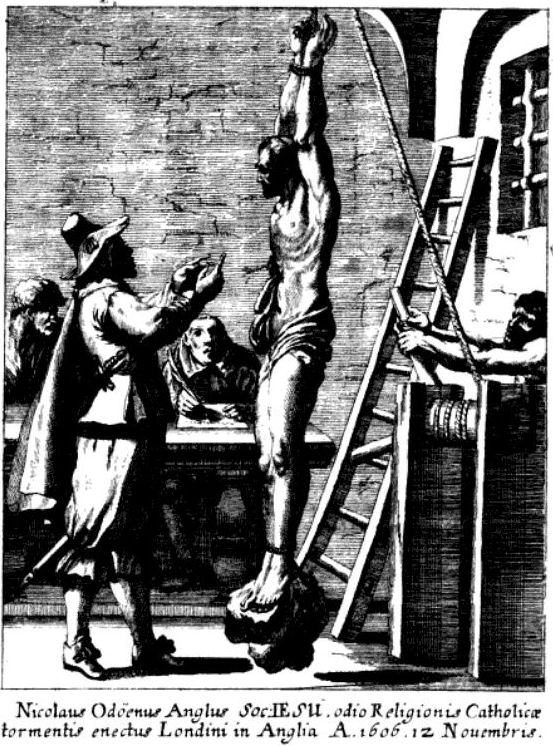

Tanner. Engraver Melchior Kusell. Saint Nicholas Owen being tortured in

the Tower of London in 1606,

1675, "Societas Jesu ad sanguinis et vitae profusionem militans"

Saint Nicolas Owen, martyr

Cet anglais, religieux de

la Compagnie de Jésus, fidèle à la foi de ses pères au péril de sa vie, assura

des refuges aux prêtres persécutés grâce à sa formation initiale de charpentier

et de maçon. Trois fois emprisonné, la dernière fois, sous le roi Jacques Ier,

parce qu’il se livra lui-même pour empêcher les poursuivants de saisir des

prêtres, il fut alors détenu à la Tour de Londres, torturé pour livrer des

prêtres, et enfin écartelé par le supplice du chevalet, sous le roi Jacques

Ier, en 1606.

SOURCE : http://www.paroisse-saint-aygulf.fr/index.php/prieres-et-liturgie/saints-par-mois/icalrepeat.detail/2015/03/22/14071/-/saint-nicolas-owen-martyr

Saint Nicolas Owen

Frère convers jésuite en

Angleterre (+ 1606)

Il construisait des cachettes pour les prêtres persécutés. Il ne s'écarta pas de l'Église romaine au moment où c'était une cause de mort. Emprisonné et torturé par deux fois, il fut écartelé la troisième fois pour avoir refusé de donner des renseignements au sujet de la conspiration des Poudres où les catholiques étaient accusés d'avoir voulu faire sauter le Parlement de Londres et tuer le roi Jacques Ier, en 1605.

Il fait partie des Quarante martyrs d'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles qui ont été canonisés en 1970.

À Londres, en 1606, saint Nicolas Owen, religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus et

martyr. Charpentier et maçon de métier, il fabriqua pendant trente-six ans des

cachettes pour y loger des prêtres. Trois fois emprisonné, la dernière fois,

sous le roi Jacques Ier, parce qu’il se livra lui-même pour empêcher les

poursuivants de saisir des prêtres, il fut alors détenu à la Tour de Londres,

torturé pour livrer des prêtres, et enfin écartelé par le supplice du chevalet.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/5940/Saint-Nicolas-Owen.html

Saint Nicolas OWEN

On connaît mal la

première partie de sa vie, mais on croit qu'il est né à Oxford, en Angleterre

vers 1550 dans une famille très catholique et grandit pendant des lois

scélérates.

Il devînt menuisier sans

doute par nécessité, pour gagner son pain quotidien.

Pendant de nombreuses

années, Owen travailla sous la direction du père jésuite Henry Garnet, qui le

fit admettre dans la Compagnie de Jésus en qualité de frère, et ce fut

probablement alors qu’il commença à construire dans les maisons des familles

catholiques, des cachettes pour les prêtres catholiques persécutés.

Il voyagea souvent d'une

maison à une autre, sous le nom de “Little John”, n'acceptant que le stricte

nécessaire pour survivre, en paiement de ses services, avant le départ pour un

nouveau projet. Pour minimiser le risque de trahison, il travaillait souvent la

nuit, et toujours seul. Et, malgré sa petite taille, il réussissait à percer de

grosses pierres, quand cela était nécessaire pour la cachette qu’il

construisait.

Le nombre de cachettes

qu'il construisit ne sera probablement jamais connu. Grâce à l'ingéniosité de

son artisanat, certaines restent peut-être encore inconnues. Il ne

s'écarta pas de l'Eglise romaine, même au moment où c'était une cause de mort.

Il fut arrêté une

première fois en 1582 ou 1583, après l'exécution d'Edmund Campion, pour

proclamer publiquement l'innocence de ce dernier, mais a été libéré plus tard.

Il a été arrêté à nouveau en 1594, et a été torturé, mais n'a rien révélé. Il a

été libéré après qu’une riche famille catholique ait payé une grosse somme pour

sa libération.

Il reprit son travail,

mais fut bientôt accusé d’avoir orchestré la fuite du père jésuite John Gerard

de la Tour de Londres en 1597.

Début de 1606, Owen fut

arrêté une dernière fois à Hindlip Hall dans le Worcestershire, se donnant

volontairement dans l'espoir de détourner l'attention des enquêteurs sur

certains prêtres qui se cachaient à proximité. Réalisant alors seulement la

valeur de la prise qu'ils avaient faite, le secrétaire d'État, Robert Cecil

exultait : « C'est incroyable, quelle fut la joie causée par son arrestation...

connaissant le grand talent d'Owen dans la construction de cachettes, et le

nombre incalculable de trous noirs qu’il avait construit pour cacher tant de

prêtres à travers l'Angleterre ».

Enfermé dans une prison

sur la rive sud de la Tamise, Owen fut transféré à la Tour de Londres. Il

y fut soumis à de terribles « examens » sur la grille Topcliffe, où

il fut suspendu par les deux poignets, alors que de lourds poids furent ajoutés

à ses pieds.

Cette procédure fut

pratiquée jusqu’à ce que “ses entrailles se soient répandues” et qu’il perde sa

vie.

Il fut canonisé en 1970

avec trente-neuf autres martyrs anglais et gallois.

Alphonse Rocha

(d’après plusieurs documents)

SOURCE : http://nouvl.evangelisation.free.fr/nicolas_owen.htm

Gaspar

Bouttats. Edward Oldcorne; Nicholas Owen, National Portrait Gallery: NPG

D17092

Supplices

de Edward Oldcorne et de Nicholas Owen, gravure par Gaspar Bouttats

Stampa con Martirio di san Nicola Owen e del beato Edoardo Oldcorne

Also

known as

John Owen

Little John

25 October as

one of the Forty

Martyrs of England and Wales

3 May on

some calendars

1 December on

some calendars

Profile

Son of a carpenter,

Nicholas was raised in a family dedicated to the persecuted Church,

and became a carpenter and mason.

Two of his brothers became priests,

another a printer of

underground Catholic books, and

Nicholas used his building skills to save the lives of priests and

help the Church‘s

covert work in England.

Nicholas worked

with Saint Edmund

Campion, sometimes using the pseudonym John Owen; his short stature

led to the nickname Little John. When Father Edmund was martyred,

Nicholas spoke out against the atrocity. For his trouble, he was imprisoned.

Father Henry

Garnet, Superior of English Jesuits,

employed Nicholas to construct hiding places and escape routes in the various

mansions used as priest-centers

throughout England.

By day he worked at the mansion on regular wood–

and stone-working

jobs at the mansions so that no one would question his presence; by night he

worked alone, digging tunnels, creating hidden passages and rooms in the house.

Some of his rooms were large enough to hold cramped, secretive prayer services,

but most were a way for single clerics to

escape the priest-hunters.

As there were no records of his work, there is no way of knowing how many of

these hiding places he built, or how many hundreds of priests he

saved. The anti–Catholic authorities

eventually learned that the hiding places existed, but had no idea who was

doing the work, or how many there were.

Due to the work, the

danger, and the periodic arrests of

the Jesuits,

Nicholas never had a formal novitiate,

but he did receive instruction, and in 1577 became

a Jesuit Brother.

On 23

April 1594 he

was arrested in London and

lodged in the Tower of London for his association with Father John

Gerard. Not knowing who they had, the authorities released Nicholas soon after,

and he resumed his work.

On 5 November 1605,

Brother Nicholas and three other Jesuits were

forced to hide in Hinlip Hall, a structure with at least 13 of his hiding

places, to escape the priest-hunters.

Owen spent four days in one of his secret rooms, but having no food or water,

he finally surrendered and was taken to a London prison.

There he was endlessly tortured for

information on the underground network of priests and

their hiding. He was abused so violently that on 1 March 1606,

while suspended from a wall, chained by

his wrists, with weights on his ankles, his stomach split open, spilling his

intestines to the floor; he survived for hours before dying from

the wound. Because he was under orders not to kill Nicholas, the torturer spread

the lie that Owen had committed suicide. One of the Forty

Martyrs of England and Wales.

Born

tortured to death on 2 March 1606 in London, England

8 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI (decree

of martyrdom)

15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI

25 October 1970 by Pope Paul

VI

Additional

Information

A

Gret Deviser of Priests’s Holes, by Allan Fea

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

MLA

Citation

“Saint Nicholas

Owen“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 October 2023. Web. 14 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-nicholas-owen/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-nicholas-owen/

St. Nicholas Owen

Feastday: March 22

Birth: 1550

Death: 1606

Nicholas was born at

Oxford, England. He became a carpenter or builder and served the Jesuit priests

in England for two decades by constructing hiding places for them in mansions

throughout the country. He became a Jesuit lay brother in 1580, and was arrested

in 1594 with Father John Gerard,

and despite prolonged torture would not give the names of any of his Catholic colleagues;

he was released on the payment of a ransom by a wealthy Catholic. Nicholas is

believed responsible for Father Gerard's dramatic escape from the Tower of

London in 1597. Nicholas was again arrested in 1606 with Father Henry Garnet,

who he had served eighteen years, Father Oldcorne, and Father Oldcorne's

servant, Brother Ralph Ashley, and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Nicholas

was subjected to such vicious torture that he died of it on March 2nd. He was

known as Little John and

Little Michael and used the aliases of Andrews and Draper. He was canonized by

Pope Paul VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of

England and Wales. His feast is March 22nd.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=805

Nicholas Owen

A Jesuit lay-brother, martyred in

1606. There is no record of his parentage, birthplace, date of

birth, or entrance into religion.

Probably a carpenter or builder by trade, he entered the Society

of Jesus before 1580, and had previously been the trusty servant of

the missionary fathers. More (1586-1661)

associates him with the first English lay-brothers.

He was imprisoned on

the death of Edmund

Campion for openly declaring that martyr's innocence,

but afterwards served Fathers Henry

Garnett and John

Gerard for eighteen years, was captured again with the latter, escaped

from the Tower, and is said to have contrived the escape of Father

Gerard. He was finally arrested at Hindlip Hall, Worcestershire,

while impersonating Father

Garnett. "It is incredible", writes Cecil, "how great

was the joy caused by

his arrest . . . knowing the great skill of Owen in

constructing hiding places, and the innumerable quantity of dark

holes which he had schemed for hiding priests all

through England."

Not only the Secretary of State but Waade, the Keeper of the

Tower, appreciated the importance of the disclosures which Owen might

be forced to make. After being committed to the Marshalsea and thence removed

to the Tower, he was submitted to most terrible "examinations" on the

Topcliffe rack, with both arms held fast in iron rings and

body hanging, and later on with heavy weights attached to his feet, and at last

died under torture. It was given out that he had committed suicide,

a calumny refuted

by Father

Gerard in his narrative. As to the day of his death, a letter of Father

Garnett's shows that he was still alive on 3 March; the "Menology" of

the province puts his martyrdom as

late as 12 Nov. He was of singularly innocent life and

wonderful prudence,

and his skill in devising hiding-places saved the lives of many of

the missionary fathers.

[Note: In 1970, Nicholas Owen was canonized by Pope Paul VI among the Forty

Martyrs of England and Wales, whose joint feast day is kept on 25 October.]

Sources

FOLEY, Records of English Jesuits (London, 1875-82), IV, 245; VII,

561; MORE, Hist. Prov. Anglicanae (St. Omers, 1660), 322; NASH, Mansions

of England (London, 1906); TAUNTON, Hist. of Jesuits in England (London,

1901); Bibl. Dict. Eng. Cath., s.v.; POLLARD in Dict. Nat. Biog.

(London, 1909), s.v.

Parker,

Anselm. "Nicholas Owen." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 22 Mar.

2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11364a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. Saint

Nicholas, and all ye holy Martyrs, pray for us.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11364a.htm

St. Nicholas Owen (c.1550-1606), familiarly known as “Little John,”

was small in stature but big in the esteem of his fellow Jesuits.

Born at Oxford, this humble artisan saved the lives of many priests and

laypersons in England during the penal times (1559-1829), when a series of

statutes punished Catholics for the practice of their faith.

Over a period of about 20 years he used his skills to build secret hiding

places for priests throughout the country.

His work, which he did completely

by himself as both architect and builder, was so good that time and time again

priests in hiding were undetected by raiding parties. He was a genius at

finding, and creating, places of safety: subterranean passages, small spaces

between walls, impenetrable recesses. At one point he was even able to

mastermind the escape of two Jesuits from the Tower of London. Whenever

Nicholas set out to design such hiding places, he began by receiving the Holy

Eucharist, and he would turn to God in prayer throughout the long, dangerous

construction process.

After many years at his unusual task, he entered the Society of Jesus and

served as a lay brother, although—for very good reasons—his connection with the

Jesuits was kept secret.

After a number of narrow escapes, he himself was finally caught in 1594.

Despite protracted torture, he refused to disclose the names of other

Catholics. After being released following the payment of a ransom, “Little

John” went back to his work. He was arrested again in 1606. This time he was

subjected to horrible tortures, suffering an agonizing death. The jailers tried

suggesting that he had confessed and committed suicide, but his heroism and

sufferings soon were widely known.

He was canonized in 1970 as one of the 40 Martyrs of England and Wales.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-nicholas-owens/

Nicholas Owen M (RM)

Born in Oxford, England; died in the Tower of London, 1606; beatified in 1929;

canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and

Wales; feast day formerly March 12.

Saint Nicholas was probably the most important person in the preservation of

Catholicism in England during the period of the penal laws against the faith.

He was a carpenter or builder, who saved the lives of countless Jesuit priests

in England for two decades by constructing hiding places for them in mansions

throughout the country. He became a Jesuit lay brother in 1580, was arrested in

1594 with Father John Gerard, and despite prolonged torture would not give the

names of any of his Catholic colleagues; he was released on the payment of a

ransom by a wealthy Catholic.

Brother Nicholas is believed to have been responsible for Father Gerard's

dramatic escape from the Tower of London in 1597.

Nicholas was arrested a third time in 1606 with Father Henry Garnet, whom he

had served 18 years, Father Edward Oldcorne, and Father Oldcorne's servant,

Brother Ralph Ashley. He refused to give any information concerning the

Gunpowder Plot. They were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Nicholas was

subjected to such vicious torture, which literally tore his body to pieces,

that he died of it.

Nicholas was also known as Little John and Little Michael and used the aliases

of Andrewes and Draper (Attwater2, Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0322.shtml

St Nicholas Owen was

born in 1562 in Oxford into a devout recusant family, and trained as a

carpenter and joiner. As a Jesuit lay brother he became the servant of

Henry Garnet SJ, the Superior of the English mission, in 1588 - a time

when the penalty for Catholic priests discovered in England was torture and

death. His carpentry skills were put to use in building priest holes or

hiding places in the houses of Catholics all over the country. Known as

“Little Jo hn”, (few of his clients knew his real name) Owen was of very short

stature and suffered ill health, including a hernia. Nevertheless he

spent eighteen years doing strenuous physical labour in cramped spaces, always

alone and at night to avoid discovery. In 1597 he helped to plan

the famous escape from the Tower of London of his Jesuit colleague John Gerard

SJ. Fr Garnet said of him:

"I verily think no

man can be said to have done more good of all those who laboured in the English

vineyard. He was the immediate occasion of saving the lives of many hundreds of

persons, both ecclesiastical and secular."

Owen was finally arrested

in 1606 in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot. The authorities were

delighted to have caught him, and hoped to extract valuable information under

torture. They were disappointed. Nicholas Owen was arrested and

taken away to Marshalsea Prison where he endured a great deal of torture. No

exact records of what he endured are in existence, but we do know from Fr John

Gerard, of the tortures that he endured:

They took me to a big

upright pillar, one of the wooden posts which held the roof of this huge

underground chamber. Driven into the top of it were iron staples for supporting

heavy weights. Then they put my wrists into iron gauntlets and ordered me to

climb two or three wicker steps. My arms were then lifted up and an iron bar

passed through the rings of one gauntlet. This done, they fastened the bar with

a pin to prevent it slipping, and then, removing the wicker steps one by one

from under my feet, they left me hanging by my hands and arms fastened above my

head … Hanging like this I began to pray … But I could hardly utter the words,

such a gripping pain came over me. It was worst in my chest and belly, my hands

and arms. All the blood of my body seemed to rush up into my arms and hands and

I thought that blood was oozing out from the ends of my fingers and pores of my

skin. But it was only a sensation caused by my flesh swelling above the irons

holding them. The pain was so intense that I thought I could not possibly

endure it … Sometime after one o’clock, I think, I fell into a faint. How long

I was unconscious I don’t know, but I don’t think it was long, for the men held

my body up or put the wicker steps under my feet until I came to. Then they

heard me pray and immediately let me down again. And they did this every time I

fainted – eight or nine times that day – before it struck five … The next

morning the gauntlets were placed on the same part of my arms as last time. They

would not fit anywhere else, because the flesh on either side had swollen into

small mounds, leaving a furrow between; and the gauntlets could only be

fastened in the furrow … I stayed like this and began to pray, sometimes aloud,

sometimes to myself, and I put myself in the keeping of Our Lord and His

blessed Mother. This time it was longer before I fainted, but when I did they

found it so difficult to bring me round that they thought that I was dead, or

certainly dying and summoned the Lieutenant … I was hung up again. The pain was

intense now, but I felt great consolation of soul, which seemed to me to come

from a desire of death … For many days after I could not hold a knife in my

hands – that day I could not even move my fingers or help myself in the

smallest way. The gaoler had to do everything for me.

Nicholas suffered all of

this and more, made all the worse by the injuries he had incurred through years

of manual labour. Yet he wouldn’t say anything. His two confessions stand from

those days.

Examination of Nicholas

Owen, taken on the 26th February, 1606.

He confesses that he has

been called by the name of Andrews, but doesn’t know whether he has been known

by the name Little John or Draper, or any other name other than Owen or

Andrews.

That he came to Mr

Abington’s house the Saturday before he was taken, but refuses to answer from

what place he came to the house from.

He denies that he knows

Father Garnett or that he has ever served him, or that Fr Garnett is known by

the name Mease, Darcy, Whalley, Philips,, Fermor, or any other name.

He denies that he knows a

Jesuit called Oldcorne or Hall, and also denies that he knows that Chambers

served Hall the Jesuit.

He confesses that he has

known George Chambers for six or seven years, and that he became acquainted

with him at an ordinarie in Fleet Street and that at this time he served Mr

Henry Drury of Sussex.

The confession of

Nicholas Own, taken on the 1st March 1606.

He confesses that he has

known and sometimes attended Henry Garnett, the Provincial of the Jesuits for

around four years.

He confesses that he was

at the house of Thomas Throgmorton called Coughton at the beginning of November

last year, when the Lady Digby was there and by the watch that was in town they

knew that Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and the rest of the gun powder plotters

were up in arms.

That on All Saints Day

last year, Garnett said Mass at Coughton House, and that at that Mass there

were around half a dozen people.

That Henry Garnett was at

Henlipp, the house of Thomas Abington some six weeks before he was apprehended

and Hall the Jesuit was there about three days before the house of Mr Abington

was searched.

That while he was staying

with Garnett, he made his fire and served him and that both he and Garnett hid

in a secret room below the dining room.

There was no new

information in these confessions and the authorities lost patience. The

tortures became more violent and on the next day, despite a plate they had

fitted around Nicholas to prevent the torture further damaging his pre-existing

injuries, Nicholas died, quite literally broken apart by the torture.

The authorities were now

in an awkward position. Not only had they been torturing illegally an already

injured man, but they had murdered him before extracting a confession. A cover

up was swiftly arranged with an inquest returning a verdict of suicide.

Many of the martyrs of

England died very public deaths on the scaffold of Tyburn, but Nicholas died as

he had lived; in secret. We have no memorable saying of his to meditate on –

his priest holes, which are his wordless prayers, are all that remain. Nicholas

in his agonised, furtive death had finished with all concealment and disguises

and was welcomed by Campion and all the martyrs into a fellowship where there

is no use for human language.

SOURCE : http://www.jesuit.org.uk/st-nicholas-owen-sj-biography-and-last-confession

A Great Deviser

of “Priests’ Holes”

During the deadly feuds

which existed in the Middle Ages, when no man was secure from spies and

traitors even within the walls of his own house, it is no matter of wonder that

the castles and mansions of the powerful and wealthy were usually provided with

some precaution in the event of a sudden surprise, viz. a secret means of

concealment or escape that could be used at a moment’s notice; but the majority

of secret chambers and hiding-places in our ancient buildings owe their origin

to religious persecution, particularly during the reign of Elizabeth, when the

most stringent laws and oppressive burdens were inflicted upon all persons who

professed the tenets of the Church of Rome.

In the first years of the

virgin Queen’s reign all who clung to the older forms of the Catholic faith

were mercifully connived at, so long as they solemnised their own religious

rites within their private dwelling-houses; but after the Roman Catholic rising

in the north and numerous other Popish plots, the utmost severity of the law

was enforced, particularly against seminarists, whose chief object was, as was

generally believed, to stir up their disciples in England against the

Protestant Queen. An Act was passed prohibiting a member of the Church of Rome

from celebrating the rites of his religion on pain of forfeiture for the first

offence, a year’s imprisonment for the second, and imprisonment for life for

the third. (In December, 1591, a priest was hanged before the door of a house

in Gray’s Inn Fields for having there said Mass the month previously.) All

those who refused to take the Oath of Supremacy were called “recusants” and

were guilty of high treason. A law was also enacted which provided that if any

Papist should convert a Protestant to the Church of Rome, both should suffer

death, as for high treason.

The sanguinary laws

against seminary priests and “recusants” were enforced with the greatest

severity after the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot. These were revived for a

period in Charles II’s reign, when Oates’s plot worked up a fanatical hatred

against all professors of the ancient faith. In the mansions of the old Roman

Catholic families we often find an apartment in a secluded part of the house or

garret in the roof named “the chapel,” where religious rites could be performed

with the utmost privacy, and close handy was usually an artfully contrived

hiding-place, not only for the officiating priest to slip into in case of

emergency, but also where the vestments, sacred vessels, and altar furniture

could be put away at a moment’s notice.

It appears from the

writings of Father Tanner that most of the hiding-places for priests, usually

called “priests’ holes,” were invented and constructed by the Jesuit Nicholas

Owen, a servant of Father Garnet, who devoted the greater part of his life to

constructing these places in the principal Roman Catholic houses all over

England.

“With incomparable

skill,” says an authority, “he knew how to conduct priests to a place of safety

along subterranean passages, to hide them between walls and bury them in

impenetrable recesses, and to entangle them in labyrinths and a thousand

windings. But what was much more difficult of accomplishment, he so disguised

the entrances to these as to make them most unlike what they really were.

Moreover, he kept these

places so close a secret with himself that he would never disclose to another

the place of concealment of any Catholic. He alone was both their architect and

their builder, working at them with inexhaustible industry and labour, for

generally the thickest walls had to be broken into and large stones excavated,

requiring stronger arms than were attached to a body so diminutive as to give

him the nickname of ‘Little John,’ and by this his skill many priests were

preserved from the prey of persecutors. Nor is it easy to find anyone who had

not often been indebted for his life to Owen’s hiding-places.”

How effectually “Little

John’s” peculiar ingenuity baffled the exhaustive searches of the

“pursuivants,” or priest-hunters, has been shown by contemporary accounts of

the searches that took place frequently in suspected houses. Father Gerard, in

his Autobiography, has handed down to us many curious details of the mode of

procedure upon these occasions – how the search-party would bring with them

skilled carpenters and masons and try every possible expedient, from systematic

measurements and soundings to bodily tearing down the panelling and pulling up

the floors. It was not an uncommon thing for a rigid search to last a fortnight

and for the “pursuivants” to go away empty handed, while perhaps the object of

the search was hidden the whole time within a wall’s thickness of his pursuers,

half starved, cramped and sore with prolonged confinement, and almost afraid to

breathe lest the least sound should throw suspicion upon the particular spot

where he lay immured.

After the discovery of

the Gunpowder Plot, “Little John” and his master, Father Garnet, were arrested

at Hindlip Hall, Worcestershire, from information given to the Government by

Catesby’s servant Bates. Cecil, who was well aware of Owen’s skill in

constructing hiding-places, wrote exultingly: “Great joy was caused all through

the kingdom by the arrest of Owen, knowing his skill in constructing

hiding-places, and the innumerable number of these dark holes which he had

schemed for hiding priests throughout the kingdom.” He hoped that “great booty

of priests” might be taken in consequence of the secrets Owen would be made to

reveal, and directed that first he should “be coaxed if he be willing to

contract for his life,” but that “the secret is to be wrung from him.” The

horrors of the rack, however, failed in its purpose. His terrible death is thus

briefly recorded by the Governor ot the Tower at that time: “The man is dead –

he died in our hands”; and perhaps it is as well the ghastly details did not

transpire in his report.

The curious old mansion

Hindlip Hall (pulled down in the early part of the last century) was erected in

1572 by John Abingdon, or Habington, whose son Thomas (the brother-in-law of

Lord Monteagle) was deeply involved in the numerous plots against the reformed

religion. A long imprisonment in the Tower for his futile efforts to set Mary

Queen of Scots at liberty, far from curing the dangerous schemes of this

zealous partisan of the luckless Stuart heroine, only kept him out of mischief

for a time. No sooner had he obtained his freedom than he set his mind to work

to turn his house in Worcestershire into a harbour of refuge for the followers

of the older rites. In the quaint irregularities of the masonry free scope was

given to “Little John’s” ingenuity; indeed, there is every proof that some of

his masterpieces were constructed here. A few years before the “Powder Plot”

was discovered, it was a hanging matter for a priest to be caught celebrating

the Mass. Yet with the facilities at Hindlip he might do so with comfort, with

every assurance that he had the means of evading the law. The walls of the

mansion were literally riddled with secret chambers and passages. There was

little fear of being run to earth with hidden exits everywhere. Wainscoting,

solid brickwork, or stone hearth were equally accommodating, and would swallow

up fugitives wholesale, and close over them, to “Open, Sesame!” again only at

the hider’s pleasure.

– text taken from Secret Chambers and Hiding Places, by Allan

Fea, London, England, 1904

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/a-great-deviser-of-priests-holes/

MAR 22 – ST NICHOLAS

OWEN, SJ, (D. 1606) – MARTYR, ARTIST, BUILDER OF HIDING PLACES FOR PRIESTS

Nicholas, familiarly

known as “Little John,” was small in stature but big in the esteem of his

fellow Jesuits. Born at Oxford, this humble artisan saved the lives of

many priests and laypersons in England during the penal times (1559-1829), when

a series of statutes punished Catholics for the practice of their faith.

Over a period of about 20

years he used his skills to build secret hiding places for priests throughout

the country. His work, which he did completely by himself as both architect and

builder, was so good that time and time again priests in hiding were undetected

by raiding parties. He was a genius at finding, and creating, places of safety:

subterranean passages, small spaces between walls, impenetrable recesses. At

one point he was even able to mastermind the escape of two Jesuits from the

Tower of London. Whenever Nicholas set out to design such hiding places, he

began by receiving the Holy Eucharist, and he would turn to God in prayer

throughout the long, dangerous construction process.

Nicholas enrolled as an

apprentice to the Oxford joiner William Conway on the feast of the Purification

of Blessed Mary, February 2nd, 1577. He was bound in indenture and as an

apprentice for a period of eight years and the papers of indenture state that

he was the son of Walter Owen, citizen of Oxford, carpenter. Oxford at the time

was strongly Catholic. The Statute of artificers determined that sons should

follow the profession into which they were born. If he completed his

apprenticeship it would have been in 1585. We know from Fr. John Gerard, SJ, a

biographer of Nicholas’, that he began building hides in 1588 and continued

over a period of eighteen years when he could have been earning good money

satisfying the contemporary demand for well-made solid furniture.

St Henry Garnet, SJ,

Jesuit Superior in England at the time, in a letter dated 1596 writes of a

carpenter of singular faithfulness and skill who has traveled through almost

the entire kingdom and, without charge, has made for Catholic priests hiding

places where they might shelter the fury of heretical searchers. If money is

offered him by way of payment he gives it to his two brothers; one of them is a

priest, the other a layman in prison for his faith.

Owen was only slightly

taller than a dwarf, and suffered from a hernia caused by a horse falling on

him some years earlier. Nevertheless, his work often involved breaking through

thick stonework; and to minimize the likelihood of betrayal he often worked at

night, and always alone. The number of hiding-places he constructed will never

be known. Due to the ingenuity of his craftsmanship, some may still be

undiscovered.

After many years at his

unusual task, he entered the Society of Jesus and served as a lay brother,

although—for very good reasons—his connection with the Jesuits was kept secret.

After a number of narrow escapes, he himself was finally caught in 1594.

Despite protracted torture, he refused to disclose the names of other

Catholics. After being released following the payment of a ransom, “Little

John” went back to his work. He was arrested again in 1606. This time he was

subjected to horrible tortures, suffering an agonizing death. The jailers tried

suggesting that he had confessed and committed suicide, but his heroism and

sufferings soon were widely known.

Why should priests need

hiding places? From 1585 it was considered treason, punishable by a traitor’s

death, to be found in England if a priest had been ordained abroad. Of Owen,

the modern edition of Butler’s Lives of the Saints says: “Perhaps no single

person contributed more to the preservation of Catholic religion in England in

penal times”.

The Gunpowder Plot of

1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the

Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I of

England and VI of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by

Robert Catesby. The last hope for the Catholics collapsed when peace was

made with Spain. They had hoped that Catholic Spain, as part of the bargain,

would have secured freedom for them to practice their religion. Relief of

Catholics was discussed, but James said that his Protestant subjects wouldn’t

stand for it. So there was to be no relief. In fact the screw was

tightened again.

Anglican bishops were

ordered to excommunicate Catholics who would not attend Anglican services –

this meant that no sale or purchase by them was valid, no property could

be passed on by deed or by will. The level of persecution was higher than

ever it had been under Elizabeth.

In the aftermath of the

Gunpowder Plot, 1605, the result of the frustration of a group of young

Catholics when, after dropping hints of toleration, James I made it clear that

there would be no relaxation of anti – Catholic legislation, the hunt for

priests accused of complicity centered on Hindlip House. This had been provided

with hiding places by Nicholas Owen which proved undetectable. He himself was

there and when he emerged after four days of hiding he was arrested.

At daybreak on Monday,

20th November, 1605, Hindlip House was surrounded by 100 men. They began to rip

the house to pieces. In the dark, early on Thursday morning, two men,

Owen and Bl Ralph Ashley, SJ, another lay-brother and cook, were spotted

stealing along a gallery. They said they were no longer able to conceal

themselves, having had but one apple between them for four days. They would not

give their names.

It was hardly likely that

Nicholas Owen, of all people, would not have been better provided. They

had twice been tipped off during the previous week that a search was imminent.

Possibly they hoped that in giving themselves up they would distract attention

from the two priests still in hiding, Fr Garnet, SJ, and Fr Oldcorne, SJ, still

hiding in Hindlip House, even to being mistaken for them. It was a ruse

that had worked before. It didn’t work now. The search was

intensified. The priests were in a hide which had been supplied with a

feeding tube from an adjoining bedroom, but the hiding place had not been

designed to be lived in for a week. After 8 days they emerged, were arrested

and identified. All four were taken to London.

Nicholas Owen, SJ, had

been in prison before; he had been tortured before. He was now taken to

the torture room, for the first time, on the 26th of February 1606. His

identity as a hide-builder seemed to have been betrayed. “We will try to get

from him by coaxing, if he is willing to contract for his life, an excellent

booty of priests”. Realizing just whom they had caught, and his value,

Secretary of State, Robert Cecil exulted: “It is incredible, how great was the

joy caused by his arrest… knowing the great skill of Owen in constructing

hiding places, and the innumerable quantity of dark holes which he had schemed

for hiding priests all through England.”

On March 2nd it was

announced that Nicholas Owen had committed suicide. People were simply

incredulous. It would have been impossible for one who had been tortured as he

had. The Venetian Ambassador reported home: “Public opinion holds

that Owen died of the tortures inflicted on him, which were so severe that they

deprived him not only of his strength but of the power to move any part of his

body”.

It seems certain that the

suicide story was a fiction concocted by a Government deeply embarrassed to

find itself with a corpse in its custody as a result of torture.

For those few grim days

in February, writes a historian, as the Government tried to break him, the fate

of almost every English Catholic lay in Owen’s hands.

In life he had saved

them, in death he would too: not a single name escaped him.

In opposition to English

law, which forbade the torture of a man suffering from a hernia, as he was, he

was racked day after day, six hours at a time. He died under torture without

betraying any secret – and he knew enough to bring down the entire network of

covert Catholics in England.

“Most brutal of all was

the treatment given to Nicholas Owen, better known to the recusants as Little

John. Since he had a hernia caused by the strain of his work, as well as a

crippled leg, he should not have been physically tortured in the first place.

But Little John, unlike many of those interrogated, did have valuable

information about the hiding places he had constructed; if he had talked, all

too many priests would have been snared ‘like partridges in a net’. In this

good cause the government was prepared to ignore the dictates of the law and

the demands of common humanity. A leading Councillor, on hearing his name, was

said to have exclaimed: “Is he taken that knows all the secret places? I am

very glad of that. We will have a trick for him.”

The trick was the

prolonged use of the manacles, an exquisitely horrible torture for one of

Owen’s ruptured state. He was originally held in the milder prison of the

Marshalsea, where it was hoped that other priests would try to contact him, but

Little John was ‘too wise to give any advantage’ and spent his time safely and

silently at prayer. In the Tower he was brought to make two confessions on 26

February and 1 March.

In the first one, he

denied more or less everything. By the time of the second confession, long and

ghastly sessions in the manacles produced some results (his physical condition

may be judged by the fact that his stomach had to be bound together with an

iron plate, and even that was not very effective for long). Little John

admitted to attending Father Garnet at White Webbs and elsewhere, that he had

been at Coughton during All Saints visit, and other details of his service and

itinerary. However, all of this was known already. Little John never gave

up one single detail of the hiding places he had spent his adult life

constructing for the safety of his co-religionists.

The lay brother died

early in the morning of 2 March. He died directly as a result of his ordeal and

in horrible, lingering circumstances. By popular standards of his day, this was

a stage of cruelty too far. The government acknowledged this in its own way by

putting out the story that Owen had ripped himself open with the knife given

him to eat his meat – while his keeper was conveniently looking elsewhere –

rather than face renewed bouts of torture. Yet Owen’s keeper had told a

relative who wanted Owen to make a list of his needs that his prisoner’s hands

were so useless that he could not even feed himself, let alone write.

The story of the suicide

was so improbable that neither Owen’s enemies nor his friends, so well

acquainted with his character over so many years, believed it. Suicide was a

mortal sin in the Catholic Church, inviting damnation, and it was unthinkable

that a convinced Catholic like Nicholas Owen should have imperiled his immortal

soul in this manner.”

Father Gerard wrote of

him: “I verily think no man can be said to have done more good of all

those who laboured in the English vineyard. He was the immediate occasion of

saving the lives of many hundreds of persons, both ecclesiastical and

secular.” -Autobiography of an Elizabethan

http://www.marysdowryproductions.org/Saint_Nicholas_Owen.html

http://www.medieval-castle.com/architecture_design/medieval_priest_hole.htm

-St Nicholas Owen, SJ,

being tortured in the Tower of London, 1606. Engraver Melchior Kusell – “Societas

Jesu ad sanguinis et vitae profusionem militans”

-engraving, “Torture of

Blessed Edward Oldcorne, SJ & St Nicholas Owen, SJ, by Gaspar Bouttats,

National Portrait Gallery, London. The Jesuit hanging from his wrists

with weights tied to his feet is suffering the “Topcliffe rack”. This

method of torture was ultimately what killed Nicholas Owen, as due to his

hernia, “his bowels gushed out with his life”.

Catholic stage magicians

who practice Gospel Magic, a performance type promoting Christian values and

morals, consider St. Nicholas Owen the Patron of Illusionists and Escapologists

due to his facility at using “trompe l’oeil”, “to deceive the eye”, when

creating his hideouts and the fact that he engineered an escape from the Tower

of London. Many Catholic builders, if they are familiar with him, may say

a prayer of intercession to St Nicholas Owen prior to beginning a new project.

“May the blood of these

Martyrs be able to heal the great wound inflicted upon God’s Church by reason

of the separation of the Anglican Church from the Catholic Church. Is it not

one — these Martyrs say to us — the Church founded by Christ? Is not this their

witness? Their devotion to their nation gives us the assurance that on the day

when — God willing — the unity of the faith and of Christian life is restored,

no offence will be inflicted on the honour and sovereignty of a great country

such as England.”

–from the Homily

of Pope Paul VI at the canonization of Forty Martyrs of England and

Wales, including St. Nicholas Owen, SJ, 25 October 1970.

Statua

di San Nicola Owen

San Nicola Owen Gesuita,

martire

>>>

Visualizza la Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

Oxfordshire, Inghilterra,

1550 circa - Londra, Inghilterra, 22 marzo 1606

Tra i quaranta martiri

inglesi canonizzati il 25 ottobre 1970 da Paolo VI figura un’abile falegname,

Nicholas Owen, non l’unico del mestiere ad avere scalato l’onore degli altari

in duemila anni. Il lavoro nobilita l’uomo e vissuto in unione con Dio lo eleva

alle vette della santità. La sua vicenda si colloca sotto il regno di Giacomo I

e la sua arte gli consentì, da religioso gesuita, di realizzare per molti anni

rifugi per nascondervi i sacerdoti perseguitati, come ricorda il Martirologio

Romano. Nicholas, nato ad Oxfordshire verso il 1550, era uno dei quattro figli

di Walter Owen, un carpentiere di Oxford, che gli trasmesse una straordinaria

abilità manuale. Uno dei fratelli divenne editore di libri cattolici, mentre

gli altri due divennero sacerdoti. Nicholas lavorò a stretto contatto con i

gesuiti per parecchi anni prima di entrare nel 1597 egli stesso, ormai adulto,

nella Compagnia quale fratello converso. Era un ometto piccolino e rimase zoppo

da quando un cavallo da soma gli cadde addosso rompendogli una gamba. Il nome

di Nicholas Owen compare la prima volta in relazione al più celebre confratello

gesuita Sant’Edmondo Campion, del quale pare fu servitore e ne prese le difese

quando questi venne accusato di tradimento. Erano infatti gli anni delle persecuzioni

anticattoliche, suscitate in Inghilterra dall’avvento dello scisma anglicano e

fomentate dagli stessi sovrani inglesi, interessati a salvaguardare l’unità

religiosa della nazione. John Gerard ebbe a scrivere di Owen: “Davvero penso

che nessuno abbia fatto più bene di lui tra tutti quelli che lavorarono nella

vigna inglese”. Fu crudelmente torturato per giorni sempre allo scopo di

estorcergli informazioni circa le case che ospitavano sacerdoti ed in cui si

celebrava la Santa Messa cattolica. Infine venne appeso ai polsi, con dei pesi

alle caviglie, e dopo sei il suo corpo si squarciò per la trazione. Non rivelò

mai nulla di compromettente, limitandosi a ripetere i nomi di Gesù e Maria.

Morì dopo una terribile agonia il 22 marzo 1606.

Martirologio Romano: A

Londra in Inghilterra, san Nicola Owen, religioso della Compagnia di Gesù e

martire, che per molti anni costruì rifugi per nascondervi i sacerdoti e per

questo sotto il re Giacomo I fu incarcerato e crudelmente torturato e, messo

infine sul cavalletto, morì seguendo gloriosamente l’esempio di Cristo

Signore.

Nicholas, nato ad Oxfordshire verso il 1550, era uno dei quattro figli di Walter Owen, un carpentiere di Oxford, che gli trasmesse una straordinaria abilità manuale. Uno dei fratelli divenne editore di libri cattolici, mentre gli altri due divennero sacerdoti. Nicholas lavorò a stretto contatto con i gesuiti per parecchi anni prima di entrare nel 1597 egli stesso nella congregazione quale converso. Era un ometto piccolino e rimase zoppo da quando un cavallo da soma gli cadde addosso rompendogli una gamba.

Il nome di Nicholas Owen compare la prima volta in relazione al più celebre Sant’Edmondo Campion, del quale pare fu servitore e ne prese le difese quando questi venne accusato di tradimento. Erano infatti gli anni delle persecuzioni anticattoliche, suscitate in Inghilterra dalla nascita della Chiesa Anglicana e fomentate dagli stessi sovrani inglesi, interessati a salvaguardare l’unità religiosa della nazione. Anche Nicholas venne arrestato nel 1581 ed incarcerato in condizioni assai dura. Quando fu liberato, sparì per un certo periodo, ma pare che poi dal 1586 al 1606 fu al servizio del padre provinciale gesuita, Henry Granet, con il quale viaggio molto, ospitato dai cattolici inglesi e costruendo rifugi per i missionari ricercati, opera quest’ultima in cui adoperò ogni sua energia ed in cui poté dimostrare tutto il suo ingegno.

John Gerard ebbe a scrivere di lui: “Davvero penso che nessuno abbia fatto più bene di lui tra tutti quelli che lavorarono nella vigna inglese”. Nel 1594 Nicholas andò a Londra con padre Gerard per l’acquisto di una casa, ma furono traditi da un tale che già aveva tentato di incastrarli. John Gerard e Nicholas Owen furono così arrestati e poi incarcerati separatamente. Nicholas fu torturato per ore insieme ad un suo compagno di prigionia, ma ostinandosi a non voler rivelare nulla fu rilasciato dietro il pagamento di cauzione. Continuò allora a frequentare Gerard e questi di conseguenza nel 1597 fu imprigionato nella Torre di Londra. Il suo discepolo fu però complice della sua spettacolare fuga e probabilmente fu anche lui a trovargli un sicuro nascondiglio.

Dalla fine del 1605, con la Congiura delle polveri, si accrebbero in Inghilterra i sentimenti di opposizione verso i cattolici, ma il segretario di stato venne a conoscenza del luogo ove Owen e tre confratelli si erano rifugiati, Hindlip Hill nel Worcestershire. Dopo una settimana di ricerche, Nicholas decise di uscire allo scoperto e consegnarsi volontariamente per tentare in tal modo di salvare la vita ai sacerdoti, ma i ricercatori lungi dal demordere scovarono comunque il nascondiglio. Padre Oldcorne ed Ashley vennero impiccati, sventrati e squartati nel 1606 a Worcester, mentre padre Garnet ed Owen vennero condotti a Londra.

Quest’ultimo fu crudelmente torturato per giorni sempre allo scopo di estorcergli informazioni circa le case che ospitavano sacerdoti ed in cui si celebrava l’Eucaristia. Infine venne appeso ai polsi, con dei pesi alle caviglie, e dopo sei il suo corpo si squarciò per la trazione. Non rivelò mai nulla di compromettente, limitandosi a ripetere i nomi di Gesù e Maria. Morì dopo una terribile agonia il 22 marzo 1606 presso Londra. Nicholas Owen fu beatificato nel 1929, insieme ad una folta schiera di martiri della medesima persecuzione, ed infine canonizzato il 25 ottobre 1970 da Papa Paolo VI insieme ai Quaranta Martiri d’Inghilterra e Galles.

Autore: Fabio Arduino

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/Detailed/93218.html

CANONIZZAZIONE DI

QUARANTA MARTIRI DELL’INGHILTERRA E DEL GALLES

OMELIA DEL SANTO PADRE

PAOLO VI

Domenica, 25 ottobre l970

We extend Our greeting first of all to Our venerable brother Cardinal John Carmel Heenan, Archbishop of Westminster, who is present here today. Together with him We greet Our brother bishops of England and Wales and of all the other countries, those who have come here for this great ceremony. We extend Our greeting also to the English priests, religious, students and faithful. We are filled with joy and happiness to have them near Us today; for us-they represent all English Catholics scattered throughout the world. Thanks to them we are celebrating Christ’s glory made manifest in the holy Martyrs, whom We have just canonized, with such keen and brotherly feelings that We are able to experience in a very special spiritual way the mystery of the oneness and love of .the Church. We offer you our greetings, brothers, sons and daughters; We thank you and We bless you.

While We are particularly pleased to note the presence of the official

representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Reverend Doctor Harry Smythe,

We also extend Our respectful and affectionate greeting to all the members of

the Anglican Church who have likewise come to take part in this ceremony. We

indeed feel very close to them. We would like them to read in Our heart the

humility, the gratitude and the hope with which We welcome them. We wish also

to greet the authorities and those personages who have come here to represent

Great Britain, and together with them all the other representatives of other

countries and other religions. With all Our heart We welcome them, as we

celebrate the freedom and the fortitude of men who had, at the same time,

spiritual faith and loyal respect for the sovereignty of civil society.

STORICO EVENTO PER LA

CHIESA UNIVERSALE

La solenne canonizzazione dei 40 Martiri dell’Inghilterra e del Galles da Noi or ora compiuta, ci offre la gradita opportunità di parlarvi, seppur brevemente, sul significato della loro esistenza e sulla importanza the la loro vita e la loro morte hanno avuto e continuano ad avere non solo per la Chiesa in Inghilterra e nel Galles, ma anche per la Chiesa Universale, per ciascuno di noi, e per ogni uomo di buona volontà.

Il nostro tempo ha bisogno di Santi, e in special modo dell’esempio di coloro che hanno dato il supremo testimonio del loro amore per Cristo e la sua Chiesa: «nessuno ha un amore più grande di colui che dà la vita per i propri amici» (Io. l5, l3). Queste parole del Divino Maestro, che si riferiscono in prima istanza al sacrificio che Egli stesso compì sulla croce offrendosi per la salvezza di tutta l’umanità, valgono pure per la grande ed eletta schiera dei martiri di tutti i tempi, dalle prime persecuzioni della Chiesa nascente fino a quelle – forse più nascoste ma non meno crudeli - dei nostri giorni. La Chiesa di Cristo è nata dal sacrificio di Cristo sulla Croce ed essa continua a crescere e svilupparsi in virtù dell’amore eroico dei suoi figli più autentici. «Semen est sanguis christianorum» (TERTULL., Apologet., 50; PL l, 534). Come l’effusione del sangue di Cristo, così l’oblazione che i martiri fanno della loro vita diventa in virtù della loro unione col Sacrificio di Cristo una sorgente di vita e di fertilità spirituale per la Chiesa e per il mondo intero. «Perciò - ci ricorda la Costituzione Lumen gentium (Lumen gentium, 42) – il martirio, col quale il discepolo è reso simile al Maestro che liberamente accetta la morte per la salute del mondo, e a Lui si conforma nell’effusione del sangue, è stimato dalla Chiesa dono insigne e suprema prova di carità».

Molto si è detto e si è scritto su quell’essere misterioso che è l’uomo : sulle

risorse del suo ingegno, capace di penetrare nei segreti dell’universo e di

assoggettare le cose materiali utilizzandole ai suoi scopi; sulla grandezza

dello spirito umano che si manifesta nelle ammirevoli opere della scienza e

dell’arte; sulla sua nobiltà e la sua debolezza; sui suoi trionfi e le sue

miserie. Ma ciò che caratterizza l’uomo, ciò che vi è di più intimo nel suo

essere e nella sua personalità, è la capacità di amare, di amare fino in fondo,

di donarsi con quell’amore che è più forte della morte e che si prolunga

nell’eternità.

IL SACRIFICIO NELL’AMORE

PIÙ ALTO

Il martirio dei cristiani è l’espressione ed il segno più sublime di questo amore, non solo perché il martire rimane fedele al suo amore fino all’effusione del proprio sangue, ma anche perché questo sacrificio viene compiuto per l’amore più alto e nobile che possa esistere, ossia per amore di Colui che ci ha creati e redenti, che ci ama come Egli solo sa amare, e attende da noi una risposta di totale e incondizionata donazione, cioè un amore degno del nostro Dio.

Nella sua lunga e gloriosa storia, la Gran Bretagna, isola di santi, ha dato al mondo molti uomini e donne che hanno amato Dio con questo amore schietto e leale: per questo siamo lieti di aver potuto annoverare oggi 40 altri figli di questa nobile terra fra coloro che la Chiesa pubblicamente riconosce come Santi, proponendoli con ciò alla venerazione dei suoi fedeli, e perché questi ritraggano dalle loro esistenze un vivido esempio.

A chi legge commosso ed ammirato gli atti del loro martirio, risulta chiaro, vorremmo dire evidente, che essi sono i degni emuli dei più grandi martiri dei tempi passati, a motivo della grande umiltà, intrepidità, semplicità e serenità, con le quali essi accettarono la loro sentenza e la loro morte, anzi, più ancora con un gaudio spirituale e con una carità ammirevole e radiosa.

È proprio questo atteggiamento profondo e spirituale che accomuna ed unisce questi uomini e donne, i quali d’altronde erano molto diversi fra loro per tutto ciò che può differenziare un gruppo così folto di persone, ossia l’età e il sesso, la cultura e l’educazione, lo stato e condizione sociale di vita, il carattere e il temperamento, le disposizioni naturali e soprannaturali, le esterne circostanze della loro esistenza. Abbiamo infatti fra i 40 Santi Martiri dei sacerdoti secolari e regolari, abbiamo dei religiosi di vari Ordini e di rango diverso, abbiamo dei laici, uomini di nobilissima discendenza come pure di condizione modesta, abbiamo delle donne che erano sposate e madri di famiglia: ciò che li unisce tutti è quell’atteggiamento interiore di fedeltà inconcussa alla chiamata di Dio che chiese a loro, come risposta di amore, il sacrificio della vita stessa.

E la risposta dei martiri fu unanime: «Non posso fare a meno di ripetervi che

muoio per Dio e a motivo della mia religione; - così diceva il Santo Philip

Evans - e mi ritengo così felice che se mai potessi avere molte altre vite,

sarei dispostissimo a sacrificarle tutte per una causa tanto nobile».

LEALTÀ E FEDELTÀ

E, come d’altronde numerosi altri, il Santo Philip Howard conte di Arundel asseriva egli pure: «Mi rincresce di avere soltanto una vita da offrire per questa nobile causa». E la Santa Margaret Clitherow con una commovente semplicità espresse sinteticamente il senso della sua vita e della sua morte: «Muoio per amore del mio Signore Gesù». « Che piccola cosa è questa, se confrontata con la morte ben più crudele che Cristo ha sofferto per me », così esclamava il Santo Alban Roe.

Come molti loro connazionali che morirono in circostanze analoghe, questi quaranta uomini e donne dell’Inghilterra e del Galles volevano essere e furono fino in fondo leali verso la loro patria che essi amavano con tutto il cuore; essi volevano essere e furono di fatto fedeli sudditi del potere reale che tutti - senza eccezione alcuna - riconobbero, fino alla loro morte, come legittimo in tutto ciò che appartiene all’ordine civile e politico. Ma fu proprio questo il dramma dell’esistenza di questi Martiri, e cioè che la loro onesta e sincera lealtà verso l’autorità civile venne a trovarsi in contrasto con la fedeltà verso Dio e con ciò che, secondo i dettami della loro coscienza illuminata dalla fede cattolica, sapevano coinvolgere le verità rivelate, specialmente sulla S. Eucaristia e sulle inalienabili prerogative del successore di Pietro, che, per volere di Dio, è il Pastore universale della Chiesa di Cristo. Posti dinanzi alla scelta di rimanere saldi nella loro fede e quindi di morire per essa, ovvero di aver salva la vita rinnegando la prima, essi, senza un attimo di esitazione, e con una forza veramente soprannaturale, si schierarono dalla parte di Dio e gioiosamente affrontarono il martirio. Ma talmente grande era il loro spirito, talmente nobili erano i loro sentimenti, talmente cristiana era l’ispirazione della loro esistenza, che molti di essi morirono pregando per la loro patria tanto amata, per il Re o per la Regina, e persino per coloro che erano stati i diretti responsabili della loro cattura, dei loro tormenti, e delle circostanze ignominiose della loro morte atroce.

Le ultime parole e l’ultima preghiera del Santo John Plessington furono appunto

queste: «Dio benedica il Re e la sua famiglia e voglia concedere a Sua Maestà

un prospero regno in questa vita e una corona di gloria nell’altra. Dio conceda

pace ai suoi sudditi consentendo loro di vivere e di morire nella vera fede,

nella speranza e nella carità».

«POSSANO TUTTI OTTENERE

LA SALVEZZA»

Così il Santo Alban Roe, poco prima dell’impiccagione, pregò: «Perdona, o mio Dio, le mie innumerevoli offese, come io perdono i miei persecutori», e, come lui, il Santo Thomas Garnet che - dopo aver singolarmente nominato e perdonato coloro che lo avevano tradito, arrestato e condannato - supplicò Dio dicendo: «Possano tutti ottenere la salvezza e con me raggiungere il cielo».

Leggendo gli atti del loro martirio e meditando il ricco materiale raccolto con

tanta cura sulle circostanze storiche della loro vita e del loro martirio,

rimaniamo colpiti soprattutto da ciò che inequivocabilmente e luminosamente

rifulge nella loro esistenza; esso, per la sua stessa natura, è tale da

trascendere i secoli, e quindi da rimanere sempre pienamente attuale e, specie

ai nostri giorni, di importanza capitale. Ci riferiamo al fatto che questi

eroici figli e figlie dell’Inghilterra e del Galles presero la loro fede

veramente sul serio: ciò significa che essi l’accettarono come l’unica norma

della loro vita e di tutta la loro condotta, ritraendone una grande serenità ed

una profonda gioia spirituale. Con una freschezza e spontaneità non priva di

quel prezioso dono che è l’umore tipicamente proprio della loro gente, con un

attaccamento al loro dovere schivo da ogni ostentazione, e con la schiettezza

tipica di coloro che vivono con convinzioni profonde e ben radicate, questi

Santi Martiri sono un esempio raggiante del cristiano che veramente vive la sua

consacrazione battesimale, cresce in quella vita che nel sacramento

dell’iniziazione gli è stata data e che quello della confermazione ha

rinvigorito, in modo tale che la religione non è per lui un fattore marginale,

bensì l’essenza stessa di tutto il suo essere ed agire, facendo sì che la

carità divina diviene la forza ispiratrice, fattiva ed operante di una

esistenza, tutta protesa verso l’unione di amore con Dio e con tutti gli uomini

di buona volontà, che troverà la sua pienezza nell’eternità.

La Chiesa e il mondo di oggi hanno sommamente bisogno di tali uomini e donne, di ogni condizione me stato di vita, sacerdoti, religiosi e laici, perché solo persone di tale statura e di tale santità saranno capaci di cambiare il nostro mondo tormentato e di ridargli, insieme alla pace, quell’orientamento spirituale e veramente cristiano a cui ogni uomo intimamente anela - anche talvolta senza esserne conscio - e di cui tutti abbiamo tanto bisogno.

Salga a Dio la nostra gratitudine per aver voluto, nella sua provvida bontà, suscitare questi Santi Martiri, l’operosità e il sacrificio dei quali hanno contribuito alla conservazione della fede cattolica nell’Inghilterra e nel Galles.

Continui il Signore a suscitare nella Chiesa dei laici, religiosi e sacerdoti che siano degni emuli di questi araldi della fede.

Voglia Dio, nel suo amore, che anche oggi fioriscano e si sviluppino dei centri di studio, di formazione e di preghiera, atti, nelle condizioni di oggi, a preparare dei santi sacerdoti e missionari quali furono, in quei tempi, i Venerabili Collegi di Roma e Valladolid e i gloriosi Seminari di St. Omer e Douai, dalle file dei quali uscirono appunto molti dei Quaranta Martiri, perché come uno di essi, una grande personalità, il Santo Edmondo Campion, diceva: «Questa Chiesa non si indebolirà mai fino a quando vi saranno sacerdoti e pastori ad attendere al loro gregge».

Voglia il Signore concederci la grazia che in questi tempi di indifferentismo

religioso e di materialismo teorico e pratico sempre più imperversante,

l’esempio e la intercessione dei Santi Quaranta Martiri ci confortino nella

fede, rinsaldino il nostro autentico amore per Dio, per la sua Chiesa e per gli

uomini tutti.

PER L’UNITA DEI CRISTIANI

May the blood of these Martyrs be able to heal the great wound inflicted upon God’s Church by reason of the separation of the Anglican Church from the Catholic Church. Is it not one-these Martyrs say to us-the Church founded by Christ? Is not this their witness? Their devotion to their nation gives us the assurance that on the day when-God willing-the unity of the faith and of Christian life is restored, no offence will be inflicted on the honour and sovereignty of a great country such as England. There will be no seeking to lessen the legitimate prestige and the worthy patrimony of piety and usage proper to the Anglican Church when the Roman Catholic Church-this humble “Servant of the Servants of God”- is able to embrace her ever beloved Sister in the one authentic communion of the family of Christ: a communion of origin and of faith, a communion of priesthood and of rule, a communion of the Saints in the freedom and love of the Spirit of Jesus.

Perhaps We shall have to go on, waiting and watching in prayer, in order to

deserve that blessed day. But already We are strengthened in this hope by the

heavenly friendship of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales who are canonized

today. Amen.

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/it/homilies/1970/documents/hf_p-vi_hom_19701025.html

i martiri

Elenco dei martiti con

relativa ricorrenza:

John Houghton, Sacerdote

certosino, 4 maggio

Robert Lawrence,

Sacerdote certosino, 4 maggio

Augustine Webster,

Sacerdote certosino, 4 maggio

Richard Reynolds,

Sacerdote brigidino, 4 maggio

John Stone, Sacerdote

agostiniano, 23 dicembre

Cuthbert Mayne,

Sacerdote, 30 novembre

Edmund Campion, Sacerdote

gesuita, 1 dicembre

Ralph Sherwin, Sacerdote,

1 dicembre

Alexander Briant,

Sacerdote gesuita, 1 dicembre

John Paine, Sacerdote, 2

aprile

Luke Kirby, Sacerdote, 30

maggio

Richard Gwyn, Laico, 17

ottobre

Margaret Clitherow,

Laica, 25 marzo

Margaret Ward, Laica, 30

agosto

Edmund Gennings,

Sacerdote, 10 dicembre

Swithun Wells, Laico, 10

dicembre

Eustace White, Sacerdote,

10 dicembre

Polydore Plasden,

Sacerdote, 10 dicembre

John Boste, Sacerdote, 24

luglio

Robert Southwell,

Sacerdote gesuita, 21 febbraio

Henry Walpole, Sacerdote

gesuita, 7 aprile

Philip Howard, Laico, 19

ottobre

John Jones, Sacerdote dei

Frati Minori, 12 luglio

John Rigby, Laico, 21

giugno

Anne Line, Laica, 27

febbraio

Nicholas Owen, Religioso

gesuita, 2 marzo

Thomas Garnet, Sacerdote

gesuita, 23 giugno

John Roberts, Sacerdote

benedettino, 10 dicembre

John Almond, Sacerdote, 5

dicembre

Edmund Arrowsmith,

Sacerdote gesuita, 28 agosto

Ambrose Edward Barlow,

Sacerdote benedettino, 10 settembre

Alban Bartholomew Roe,

Sacerdote benedettino, 21 gennaio

Henry Morse, Sacerdote

gesuita, 1 febbraio

John Southworth,

Sacerdote, 28 giugno

John Plessington,

Sacerdote, 19 luglio

Philip Evans, Sacerdote

gesuita, 22 luglio

John Lloyd, Sacerdote, 22

luglio

John Wall (Gioacchino di

Sant’Anna), Sacerdote dei Frati Minori, 22 agosto

John Kemble, Sacerdote,

22 agosto

David Lewis, Sacerdote

gesuita, 27 agosto

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/40-martiri-di-inghilterra-e-galles.html

HOMILIA DO PAPA PAULO VI

Domingo, 25 de Outubro de

1970

Dirigimos a Nossa

saudação, em primeiro lugar, ao venerado Irmão, Cardeal Dom John Carmel Heenan,

Arcebispo de Westminster, aqui presente, e também aos Nossos Irmãos, Bispos da

Inglaterra, de Gales e de outros Países, que vieram a Roma para assistir a esta

grandiosa cerimónia, juntamente com muitos sacerdotes, religiosos, estudantes e

fiéis de língua inglesa. Sentimo-Nos feliz e comovido por os ter hoje à Nossa

volta. Representam, para Nós, todos os católicos ingleses, espalhados pelo

mundo e levam-Nos a celebrar a glória de Cristo nos Santos Mártires, que

acabámos de canonizar, com um sentimento tão vivo e tão fraterno que Nos

permite saborear, com singularíssima experiência espiritual, o mistério da

unidade e da caridade da Igreja. Saudamo-vos, Irmãos e Filhos, agradecemo-vos e

abençoamo-vos.

A Nossa saudação, cheia

de respeito e de afecto, também se dirige aos membros da Igreja Anglicana,

presentes a este rito. De modo particular, apraz-Nos sublinhar a presença do

representante oficial do Arcebispo de Canterbury, Reverendo Doutor Harry

Smythe. Como os sentimos perto! Gostaríamos que eles lessem no Nosso coração a

humildade, o reconhecimento e a esperança com que os acolhemos. E, agora,

saudamos as Autoridades e as Personalidades que aqui vieram representar a Grã-

Bretanha e, com elas, todos os Representantes de outros Países e de outras

Religiões. Associamo-los, de bom grado, a esta celebração da liberdade e da

fortaleza do homem, que tem fé e vive espiritualmente, ao mesmo tempo que

mantém respeitosa fidelidade à soberania da sociedade civil.

A solene canonização dos

Quarenta Mártires da Inglaterra e de Gales, que acabámos de realizar,

proporciona-Nos a agradável oportunidade de vos falar, embora brevemente, sobre

o significado da sua existência e sobre a importância que a sua vida e a sua

morte tiveram, e continuam a ter, não só para a Igreja na Inglaterra e no País

de Gales, mas também para a Igreja Universal, para cada um de nós e para todos

os homens de boa-vontade.

O nosso tempo tem

necessidade de Santos e, de modo especial, do exemplo daqueles que deram o

testemunho supremo do seu amor por Cristo e pela sua Igreja: «Ninguém tem maior

amor do que aquele que dá a sua vida pelos seus amigos » (Jo 15, 13).

Estas palavras do Divino Mestre, que se referem, em primeiro lugar, ao

sacrifício que Ele próprio realizou na cruz, oferecendo-se pela salvação de

toda a humanidade, são válidas para as grandes e eleitas fileiras dos mártires

de todos os tempos, desde as primeiras perseguições da Igreja nascente até às

dos nossos dias, talvez mais veladas, mas igualmente cruéis. A Igreja de Cristo

nasceu do sacrifício de Cristo na cruz, e continua a crescer e a desenvolver-se

em virtude do amor heróico dos seus filhos mais autênticos. Semen est

sanguis christianorum (Tertuliano, Apologeticus, 50,

em: PL 1, 534). A oblação que os mártires fazem da própria vida, em

virtude da sua união com o sacrifício de Cristo, torna-se, como a efusão do

sangue de Cristo, uma nascente de vida e de fecundidade espiritual para a

Igreja e para o mundo inteiro. Por isso, a Constituição sobre a Igreja

recorda-nos: «o martírio, pelo qual o discípulo se assemelha ao Mestre que

aceitou livremente a morte pela salvação do mundo e a Ele se conforma na efusão

do sangue, é considerado pela Igreja como doação insigne e prova suprema da

caridade » (Lumen

Gentium, n. 42)-

Tem-se falado e escrito

muito sobre este ser misterioso que é o homem: sobre os dotes do seu engenho,

capaz de penetrar nos segredos do universo e de dominar as realidades

materiais, utilizando-as para alcançar os seus objectivos; sobre a grandeza do

espírito humano, que se manifesta nas admiráveis obras da ciência e da arte;

sobre a sua nobreza e a sua fraqueza; sobre os seus triunfos e as suas

misérias. Mas o que caracteriza o homem, o que ele tem de mais íntimo no seu

ser e na sua personalidade, é a capacidade de amar, de amar profundamente, de

se dedicar com aquele amor que é mais forte do que a morte e que continua na

eternidade.

O martírio dos cristãos é

a expressão e o sinal mais sublime deste amor, não só porque o mártir se

conserva fiel ao seu amor, chegando a derramar o próprio sangue, mas também

porque este sacrifício é feito pelo amor mais nobre e elevado que pode existir,

ou seja, pelo amor d'Aquele que nos criou e remiu, que nos ama como só Ele sabe

amar, e que espera de nós uma resposta de total e incondicionada doação, isto

é, um amor digno do nosso Deus.

Na sua longa e gloriosa

história, a Grã-Bretanha, Ilha de Santos, deu ao mundo muitos homens e

mulheres, que amaram a Deus com este amor franco e leal. Por isso, sentimo-Nos

feliz por termos podido incluir hoje, no número daqueles que a Igreja reconhece

publicamente como Santos, mais quarenta filhos desta nobre terra, propondo-os,

assim, à veneração dos seus fiéis, para que estes possam haurir, na sua

existência, um vívido exemplo.

Quem lê, comovido e

admirado, as actas do seu martírio, vê claramente e, podemos dizer, com

evidência, que eles são os dignos émulos dos maiores mártires dos tempos

passados, pela grande humildade, simplicidade e serenidade, e também pelo

gáudio espiritual e pela caridade admirável e radiosa com que aceitaram a

sentença e a morte.

É precisamente esta

atitude de profunda espiritualidade que agrupa e une estes homens e mulheres,

que, aliás, eram muito diversos entre si em tudo aquilo que pode diferenciar um

grupo tão numeroso de pessoas: a idade e o sexo, a cultura e a educação, o

estado e a condição social de vida, o carácter e o temperamento, as disposições

naturais, sobrenaturais e as circunstâncias externas da sua existência.

Realmente, entre os Quarenta Mártires, temos sacerdotes seculares e regulares,

religiosos de diversas Ordens e de categoria diferente, leigos de nobilíssima

descendência e de condição modesta, mulheres casadas e mães de família. O que

os une todos é a atitude interior de fidelidade inabalável ao chamamento de

Deus, que lhes pediu, como resposta de amor, o sacrifício da própria vida.

E a resposta dos Mártires

foi unânime. São Philip Evans disse: « Não posso deixar de vos repetir que

morro por Deus e por causa da minha religião. E sinto-me tão feliz que, se

alguma vez pudesse ter mais outras vidas, estaria muito disposto a

sacrificá-las todas por uma causa tão nobre ».

E, como aliás também

muitos outros, São Philip Howard, conde de Arundel, afirmou igualmente: «Tenho

pena de ter só uma vida a oferecer por esta nobre causa». Santa Margaret

Clitherow, com simplicidade comovedora, exprimiu sintèticamente o sentido da

sua vida e da sua morte: « Morro por amor do meu Senhor Jesus ». Santo Alban

Roe exclamou: «Como isto é pouco em comparação com a morte, muito mais cruel,

que Jesus sofreu por mim ».

Como muitos outros dos

seus compatriotas, que morreram em circunstâncias análogas, estes quarenta

homens e mulheres da Inglaterra e de Gales queriam ser, e foram até ao fim,

leais para com a própria pátria que eles amavam de todo o coração. Queriam ser

e foram, realmente, fiéis súbditos do poder real, que todos, sem qualquer

excepção, reconheceram até à morte como legítimo em tudo o que pertencia à

ordem civil e política. Mas consistia exactamente nisto o drama da existência

destes mártires: sabiam que a sua honesta e sincera lealdade para com a

autoridade civil estava em contraste com a fidelidade a Deus e com tudo o que,

segundo os ditames da sua consciência, iluminada pela fé católica, compreendia

verdades reveladas sobre a Sagrada Eucaristia e sobre prerrogativas