"L'albero

di Tyburn", il patibolo usato a Londra per alcune delle esecuzioni

capitali.

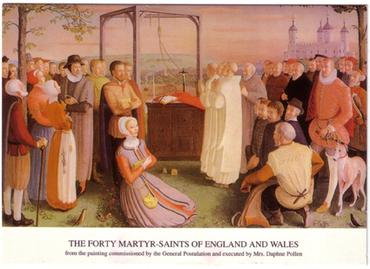

Quarante martyrs d'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles

Catholiques martyrisés en Angleterre et au Pays de

Galles entre 1535 et 1679

Groupe de quarante martyrs canonisés le 25 octobre 1970 par le pape Paul VI pour représenter les catholiques martyrisés en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles entre 1535 et 1679.

Anglais et gallois, qui entre 1535 et 1679, ont été martyrs de leur fidélité à l'Église catholique romaine. Ils sont fêtés le jour de leur canonisation commune, parce que l'unité de leur foi les a réunis malgré des dates éloignées... Durant ces années de persécutions, parce qu'ils refusaient l'adhésion au schisme du roi d'Angleterre, chacun à sa manière a souscrit à cette parole de saint John Plessington: "Que Dieu bénisse le roi et sa famille et daigne accorder à sa Majesté un règne prospère en cette vie et une couronne de gloire en l'autre. Que Dieu accorde la paix à ses sujets en leur donnant de vivre dans la vraie foi, dans l'espérance et dans la charité."

Alexandre Bryant,

David Lewis,

Jean Lloyd,

Luc Kirby

Philippe Evans,

Philippe Howard,

Polydore Plasden,

Swithun Wells (Catholic Parish of St Swithun Wells - site en anglais.)

The

Church of Our Lady and the English Martyrs, Cambridge's only Catholic church,

viewed from the door of the Oak Bistro across the street to the north, using a

6-shot pano and manual approximate perspective correction.

chiesa Santa Maria Assunta Santi quaranta martiri di Inghilterra e Galles, Cambridge

English Martyrs Church in Cambridge

chiesa Santa Maria Assunta Santi quaranta martiri di Inghilterra e Galles, Cambridge

Our

Lady and the English Martyrs Church in Cambridge

Cambridge

- Hills Road - View WNW on Church of Our Lady & the English Martyrs 1890

Dunn and Hansom

chiesa Santa Maria Assunta Santi quaranta martiri di Inghilterra e Galles, Cambridge

English Martyrs Church in Cambridge

chiesa Santa Maria Assunta Santi quaranta martiri di Inghilterra e Galles, Cambridge

Paul VI Homélies 28050

L'ÉGLISE

ET LE MONDE D'AUJOURD'HUI ONT SURTOUT BESOIN DE SAINTS

La canonisation solennelle des Quarante martyrs de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles que nous venons d'accomplir nous offre l'heureuse occasion de vous parler, bien que brièvement, du sens de leur existence et de l'importance que leur vie et leur mort ont eus et continuent d'avoir non seulement pour l'Eglise d'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles, mais aussi pour l'Eglise Universelle et pour tout homme de bonne volonté.

Notre temps a besoin de

saints et, d'une manière spéciale, de l'exemple de ceux qui ont donné le

suprême témoignage de leur amour pour le Christ et pour l'Eglise : « Personne

n'a un amour plus grand que celui qui donne sa vie pour ses amis » (Jn

15,13). Ces paroles du divin Maître, qui se rapportent en premier lieu au

sacrifice que Lui-même accomplit sur la croix en s'offrant pour le salut de

toute l'humanité valent aussi pour la grande foule choisie des martyrs de tous

les temps, depuis les premières persécutions jusqu'à celles de nos jours,

peut-être plus cachées mais pas moins cruelles. L'Eglise du Christ est née du

sacrifice du Christ sur la croix et elle continue à croître et à se développer

en vertu de l'amour héroïque de ses fils les plus authentiques. « Semen est

sanguis christianorum » (tertullianus, Apologeticus, 50 ; PL 1,

534). De même que l'effusion du sang du Christ, l'oblation que les martyrs font

de leur vie devient, en vertu de leur union avec le sacrifice du Christ, une

source de vie et de fécondité spirituelle pour l'Eglise et pour le monde tout

entier. « C'est pourquoi, nous rappelle la Constitution Lumen gentium, 42,

le martyre dans lequel le disciple est assimilé au Maître acceptant librement

la mort pour le salut du monde et dans lequel il devient semblable à Lui dans

l'effusion de son sang, est considéré par l'Eglise comme une grâce éminente et

la preuve suprême de la charité ».

Beaucoup de choses ont

été dites et écrites sur cet être mystérieux qu'est l'homme : sur les

ressources de son esprit, capable de pénétrer dans les secrets de l'univers et

de soumettre les choses matérielles en les utilisant pour arriver à leurs buts

; sur la grandeur de l'esprit humain qui se manifeste dans les oeuvres

admirables de la science et de l'art ; sur sa noblesse et sur sa faiblesse, sur

ses triomphes et sur ses misères. Mais ce qui caractérise l'homme, ce qu'il y a

de plus intime dans son être et dans sa personnalité, c'est la capacité

d'aimer, d'aimer jusqu'au fond, de se donner avec cet amour qui est plus fort

que la mort et qui se prolonge dans l'éternité.

Le martyre des chrétiens est l'expression et le signe le plus sublime de cet amour, non seulement parce que le martyr reste fidèle à son amour jusqu'à l'effusion de son propre sang, mais aussi parce que ce sacrifice est accompli pour l'amour le plus haut et le plus noble qui puisse exister, à savoir pour l'amour de Celui qui nous a créés et rachetés, qui nous a aimés comme Lui seul sait aimer, et qui attend de nous une réponse de don total et sans conditions, c'est-à-dire un amour digne de notre Dieu.

Signe d'amour

Dans sa longue et glorieuse histoire, la Grande Bretagne, île des saints, a

donné au monde beaucoup d'hommes et de femmes qui ont aimé Dieu de cet amour

pur et loyal : c'est pour cela que nous sommes heureux d'avoir pu aujourd'hui

compter quarante autres fils de cette noble terre parmi ceux que l'Eglise

reconnaît publiquement comme saints, les proposant ainsi à la vénération de ses

fidèles, et parce que ces saints représentent par leurs existences un exemple

vivant.

A celui, qui, ému et saisi d'admiration, lit les actes de leur martyre, il est

clair, nous voudrions dire évident, qu'ils sont les dignes émules des plus

grands martyrs des temps passés, en raison de la grande humilité, de

l'intrépidité, de la simplicité et de la sérénité avec lesquelles ils ont

accepté leur sentence et leur mort et même plus encore avec une joie

spirituelle et une charité admirable et radieuse.

C'est justement cette attitude profonde et spirituelle qui groupe et unit ces

hommes et ces femmes qui, par ailleurs, étaient très différents entre eux par

tout ce qui peut différencier un ensemble nombreux de personnes, à savoir l'âge

et le sexe, la culture et l'éducation, l'état de vie et la condition sociale, le

caractère et le tempérament, les dispositions naturelles et surnaturelles, les

circonstances extérieures de leur existence. Nous avons en effet, parmi les

quarante saints martyrs, des prêtres séculiers et réguliers, nous avons des

religieuses de divers ordres et de rangs divers, nous avons des laïcs, des

hommes de très noble descendance et aussi de condition modeste, nous avons des

femmes qui étaient mariées et mères de famille : ce qui les unissait tous,

c'est cette attitude intérieure de fidélité inébranlable à l'appel de Dieu qui

leur demanda, comme réponse d'amour, le sacrifice même de leur vie.

Et la réponse des martyrs fut unanime : « Je ne peux pas m'empêcher de vous

répéter que je meurs pour Dieu et à cause de ma religion — c'est ce que disait

saint Philip Evans — et je me sens si heureux que si jamais je pouvais avoir

beaucoup d'autres vies, je serais très disposé à les sacrifier toutes pour une

cause aussi noble ».

Loyauté et fidélité

Et, comme par ailleurs de nombreux autres, saint Philip Howard, comte

d'Arundel, affirmait aussi : « Je regrette de n'avoir qu'une vie à offrir pour

cette noble cause ». Et sainte Margaret Clitherow exprimait synthétiquement,

avec une simplicité émouvante, le sens de sa vie et de sa mort : « Je meurs

pour l'amour de mon Seigneur Jésus ». « Quelle petite chose, en comparaison de

la mort bien plus cruelle que le Christ a soufferte pour moi », s'écriait saint

Alban Roe.

Comme beaucoup de leurs compatriotes qui moururent dans des circonstances

analogues, ces quarante hommes et femmes de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles

voulaient être et le furent à fond, loyaux, envers leur patrie qu'ils aimaient

de tout leur coeur. Ils voulaient être et ils furent en fait de fidèles sujets

du pouvoir royal que tous, sans aucune exception, reconnurent jusqu'à leur mort

comme légitime en tout ce qui appartenait à l'ordre civil et politique. Mais ce

fut là justement le drame de l'existence de ces martyrs, à savoir que leur

honnête et sincère loyauté envers l'autorité civile se trouva en désaccord avec

la fidélité envers Dieu et qu'ainsi, suivant les préceptes de leur conscience

éclairée par la foi catholique, ils surent conserver les vérités révélées,

spécialement sur la sainte Eucharistie et sur les prérogatives inaliénables du

successeur de Pierre qui, par la volonté de Dieu, est le pasteur universel de

l'Eglise du Christ. Placés devant le choix de rester fermes dans leur foi et

donc de mourir pour elle ou d'avoir la vie sauve en reniant la foi, sans une

minute d'hésitation et avec une force vraiment surnaturelle, ils se rangèrent

du côté de Dieu et affrontèrent le martyre avec joie. Mais leur esprit était si

grand, si nobles étaient leurs sentiments, si chrétienne était l'inspiration de

leur existence que beaucoup d'entre eux moururent en priant pour leur patrie

tant aimée, pour le roi et pour la reine et même pour ceux qui avaient été les

responsables directs de leur arrestation, de leurs tortures et des

circonstances ignominieuses de leur mort atroce.

Les dernières paroles et la dernière prière de saint John Plessington furent

précisément celles-ci : « Que Dieu bénisse le roi et sa famille et daigne

accorder à Sa Majesté un règne prospère en cette vie et une couronne de gloire

en l'autre. Que Dieu accorde la paix à ses sujets en leur donnant de vivre et

de mourir dans la vraie foi, dans l'espérance et dans la charité ».

Activité et sacrifice

Voici comment pria saint Alban Roe peu de temps avant d'être pendu : «

Pardonnez-moi, ô mon Dieu, mes innombrables offenses comme je pardonne à mes

persécuteurs » et, comme lui, saint Thomas Garnet qui, après avoir nommé

particulièrement ceux qui l'avaient livré, arrêté et condamné, supplia Dieu en

disant : « Puissent-ils tous obtenir le salut et avec moi atteindre le ciel ».

En lisant les actes de leur martyre et en méditant la riche matière qui a été

recueillie avec tant de soin sur les circonstances historiques de leurs vies et

de leur martyre, nous restons frappés surtout par ce qui brille sans équivoque

dans leur existence. Cela, par sa nature même, peut traverser les siècles et

par conséquent rester toujours pleinement actuel et, spécialement de nos jours,

d'une importance capitale. Nous nous rapportons au fait que ces héros, fils et

filles de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles, ont pris leur foi vraiment au

sérieux : cela veut dire qu'ils l'acceptèrent comme l'unique règle de leur vie

et de toute leur conduite, en retirant une grande sérénité et une profonde joie

spirituelle. Avec une fraîcheur et une spontanéité non séparées de ce don précieux

de l'humour, typiquement particulier à leur peuple, avec un attachement à leur

devoir fuyant toute ostentation et avec la pureté typique de ceux qui vivent

avec des convictions profondes et bien enracinées, ces saints martyrs sont un

exemple rayonnant du chrétien qui vit vraiment sa consécration baptismale,

croît en cette vie qui lui a été donnée par le sacrement de l'initiation et que

celui de la confirmation a renforcée de telle manière que la religion n'est pas

pour lui un facteur marginal mais bien l'essence même de tout son être et de

son action, faisant en sorte que la charité divine devient la force

inspiratrice, active et agissante d'une existence toute tendue vers l'union

d'amour avec Dieu et avec tous les hommes de bonne volonté, qui trouvera sa plénitude

dans l'éternité.

L'Eglise et le monde d'aujourd'hui ont extrêmement besoin de tels hommes et de

telles femmes, de toutes conditions et de tous états de vie, prêtres, religieux

et laïcs, parce que seules les personnes de cette stature et de cette sainteté

seront capables de changer notre monde tourmenté et de lui rendre, en même

temps que la paix, cette orientation spirituelle et vraiment chrétienne à

laquelle tout homme aspire intimement — même parfois sans s'en rendre compte —

et dont nous avons tous tant besoin.

Que notre gratitude monte vers Dieu qui a voulu dans sa prévoyante bonté

susciter ces saints martyrs dont l'action et le sacrifice ont contribué à la

conservation de la foi catholique en Angleterre et dans le Pays de Galles.

Que le Seigneur continue à susciter dans l'Eglise, des laïcs, des religieux et

des prêtres qui soient de dignes émules de ces hérauts de la foi.

Dieu veuille dans son amour que fleurissent et se développent même aujourd'hui

des centres d'étude, de formation et de prière, aptes à préparer, dans les

conditions modernes, de saints prêtres et des saints missionnaires tels que

furent en ces temps les vénérables collèges de Rome et de Valladolid et les

glorieux séminaires de Saint-Omer et de Douai, des rangs desquels sortirent

justement beaucoup des quarante martyrs. Ainsi, comme le disait l'un d'entre

eux, saint Edmond Campion, une grande personnalité : « Cette Eglise ne

s'affaiblira jamais tant qu'il y aura des prêtres et des pasteurs à veiller sur

leur troupeau ». Que le Seigneur veuille nous accorder la grâce qu'en ces temps

d'indifférentisme religieux et de matérialisme théorique et pratique qui sévit

toujours davantage, l'exemple et l'intercession des saints quarante martyrs

nous réconfortent dans la foi et raffermissent notre amour authentique pour

Dieu, pour son Eglise et pour tous les hommes.

SOURCE : http://www.clerus.org/bibliaclerusonline/fr/itx.htm

Forty Martyrs of

England and Wales

formerly 4

May

Profile

Following the dispute

between the Pope and King Henry

VIII in the 16th

century, faith questions in the British Isles became entangled with

political questions, with both often being settled by torture and murder of

loyal Catholics.

In 1970,

the Vatican selected 40 martyrs,

men and women, lay and religious,

to represent the full group of perhaps 300 known to have died for

their faith and

allegiance to the Church between 1535 and 1679.

They each have their own day of memorial,

but are remembered as a group on 25

October. They are

25

October 1970 by Pope Paul

VI

Additional

Information

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

video

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

MLA

Citation

“Forty Martyrs of England

and Wales“. CatholicSaints.Info. 17 September 2023. Web. 10 December 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/forty-martyrs-of-england-and-wales/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/forty-martyrs-of-england-and-wales/

Forty Martyrs of England

and Wales (RM)

Died 16th and 17th

centuries; canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970. Each of the individual saints has

his own feast day in addition to the corporate one today. The dates vary in the

diocesan calendars of England and Wales. The forty are only a small portion of

the many martyrs of the period whose causes have been promoted. All suffered

for continuing to profess the Catholic faith following King Henry VIII's

promulgation of the Act of Supremacy, which declared that the king of England was

the head of the Church of England.

Most of them were hanged,

drawn, and quartered--a barbaric execution, which meant that the individual was

hanged upon a gallows, but cut down before losing consciousness. While still

alive--and conscious, they were then ripped up, eviscerated, and the hangman

groped about among the entrails until he found the heart--which he tore out and

showed to the people before throwing it on a fire (Undset).

The list below gives very

basic details. More information is given on the individual feast day listed.

Alban Bartholomew Roe--Benedictine

priest (born in Suffolk; died at Tyburn, 1642) (f.d. January 21).

Alexander Briant--priest

(born in Somerset, England; died at Tyburn, 1851) (f.d. December 1).

Ambrose Edward Barlow--Benedictine

priest (born in Manchester, England, 1585; died at Lancaster, 1641) (f.d.

September 10).

Anne Higham Line--widow,

for harboring priests (born at Dunmow, Essex, England; died at Tyburn, 1601)

(f.d. February 27).

Augustine Webster--Carthusian

priest (died at Tyburn, 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Cuthbert Mayne--Priest

(born in Youlston, Devonshire, England, 1544; died at Launceston, 1577) (f.d.

November 30).

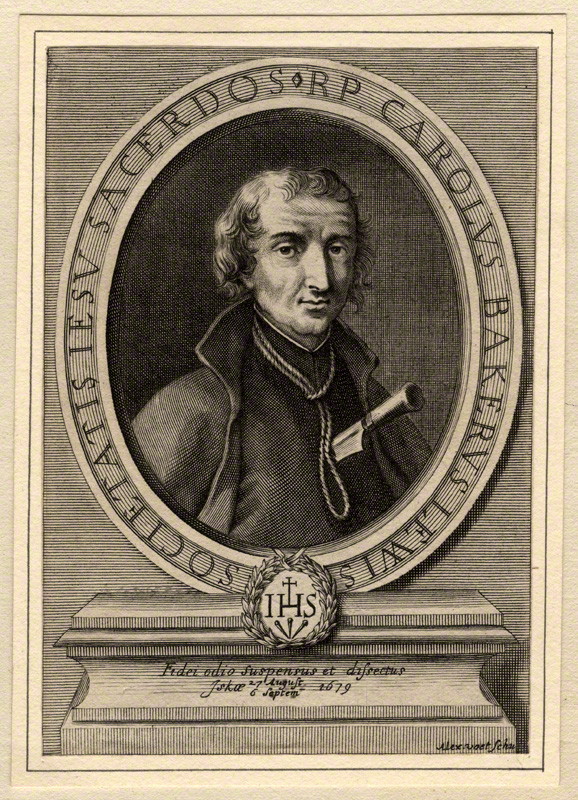

David Lewis--Jesuit

priest, (born at Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, Wales, in 1616; died at Usk 1679)

(f.d. August 27).

(Brian) Edmund Arrowsmith--Jesuit

priest (born Haydock, England, 1584; died at Lancaster in 1628) (f.d. August

28).

Edmund Campion--Jesuit

priest (born in London, England, c. 1540; died at Tyburn, 1581) (f.d. December

1).

Edmund Jennings (Genings,

Gennings)-- priest (born at Lichfield, England, in 1567; died at Tyburn 1591)

(f.d. December 10).

Eustace White--priest

(born at Louth, Lincolnshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1591) (f.d. December

10).

Henry Morse--Jesuit

priest (born at Broome, Suffolk, England, in 1595; died at Tyburn, 1645) (f.d.

February 1).

Henry Walpole--Jesuit

priest (born at Docking, Norfolk, England, 1558; died at York in 1595) (f.d.

April 7).

John Almond--priest (born

at Allerton, near Liverpool, England, 1577; died at Tyburn, 1612) (f.d.

December 5).

John Boste--priest (born

in Dufton, Westmorland, England, c. 1544; died at Dryburn near Durham, 1594)

(f.d. July 24).

John Houghton--Carthusian

priest (born in Essex, England, in 1487; died at Tyburn, 1535) (f.d. May 4).

John Jones (alias

Buckley)--Friar Observant (born in Clynog Fawr, Carnavonshire, Wales; died at

Southwark, London, in 1598) (f.d. July 12).

John Kemble--priest (born

at Saint Weonard's, Herefordshire, England, in 1599; died at Hereford in 1679)

(f.d. August 22).

John Lloyd--priest,

Welshman (born in Brecknockshire, Wales; died in Cardiff, Wales, in 1679) (f.d.

July 22).

John Paine (Payne)--priest

(born at Peterborough, England; died at Chelmsford, 1582) (f.d. April 2).

John Plessington (a.k.a.

William Pleasington)--priest (born at Dimples Hall, Lancashire, England; died

at Barrowshill, Boughton outside Chester, England, 1679) (f.d. July 19).

John Rigby--household

retainer of the Huddleston family (born near Wigan, Lancashire, England, c.

1570; died at Southwark in 1601) (f.d. June 21).

John Roberts--Benedictine

priest, Welshman (born near Trawsfynydd Merionethshire, Wales, in 1577; died at

Tyburn, 1610) (f.d. December 10).

John Southworth--priest

(born in Lancashire, England, in 1592; died at Tyburn 1654) (f.d. June 28).

John Stone--Augustinian

friar (born in Canterbury, England; died at Canterbury, c. 1539) (f.d. December

27).

John Wall--Franciscan

priest (born in Lancashire, England, 1620; died at Redhill, Worcester, in 1679)

(f.d. August 22).

Luke Kirby--priest (born

at Bedale, Yorkshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1582) (f.d. May 30).

Margaret Middleton

Clitherow--wife, mother, and school mistress (born in York, England, c. 1555;

died at York in 1586) (f.d. March 25).

Margaret Ward--gentlewoman

who engineered a priest's escape from jail (born in Congleton, Cheshire,

England; died at Tyburn in 1588) (f.d. August 30).

Nicholas Owen--Jesuit

laybrother (born at Oxford, England; died in the Tower of London in 1606) (f.d.

March 2).

Philip Evans--Jesuit

priest, (born in Monmouthshire, Wales, in 1645; died in Cardiff, Wales, in

1679) (f.d. July 22).

Philip Howard--Earl of

Arundel and Surrey (born in 1557; died in the Tower of London, believed to have

been poisoned, 1595) (f.d. October 19).

Polydore Plasden--priest

(born in London, England; died at Tyburn, in 1591) (f.d. December 10).

Ralph Sherwin--priest

(born at Rodsley, Derbyshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1851) (f.d. December 1).

Richard Gwyn--poet and schoolmaster;

protomartyr of Wales (born at Llanidloes, Montgomeryshire, Wales, in 1537; died

at Wrexham, Wales, in 1584) (f.d. October 17).

Richard Reynolds--Brigittine

priest (born in Devon, England, c. 1490; died Tyburn in 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Robert Lawrence--Carthusian

priest (died at Tyburn in 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Robert Southwell--Jesuit

priest (born at Horsham Saint, Norfolk, England, c. 1561; died at Tyburn in

1595) (f.d. February 21).

Swithun Wells--schoolmaster

(born at Bambridge, Hampshire, England, in 1536; died at Gray's Inn Fields,

London, 1591) (f.d. December 10). Mrs. Wells was also condemned to death, but

was reprieved and died in prison, 1600).

Thomas Garnet--Jesuit

priest (born at Southwark, England; died at Tyburn, in 1608) (f.d. June

23).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1025.shtm

John Houghton, O Cart. M (RM)

Born in Essex, England, in 1487; died at Tyburn on May 4, 1535; beatified in 1886; canonized by Pius VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. Saint John served as a parish priest for four years after his graduation from Cambridge. Then he joined the Carthusians, where he was named prior of Beauvale Charterhouse in Northampton and, just a few months later, prior of London Charterhouse.

In 1534, he and his

procurator, Blessed Humphrey Middlemore, were arrested for refusing to accept

the Act of Succession, which proclaimed the legitimacy of Anne Boleyn's

children by Henry VIII. They were soon released when the accepted the act with

the proviso "as far as the law of God allows."

The following year Father

Houghton was again arrested when he, Saint Robert Lawrence, and Saint Augustine

Webster went to Thomas Cromwell to seek an exemption from taking the oath

required in the Act of Supremacy. He, as the first of hundreds to refuse to

apostatize in favor of the crowned heads of England, gave a magnificent example

to his monks and the whole of Britain of fidelity to the Catholic faith.

As the sentence of

drawing and quartering was read to Father Houghton, he said, "And what

wilt thou do with my heart, O Christ?" The three were dragged through the

streets of London, treated savagely, and then hanged, drawn, and quartered at

Tyburn. After his death, John Houghton's body was chopped into pieces and hung

in various parts of London (Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney).

John Houghton is depicted

as a Carthusian with a rope around his neck, holding up his heart (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0504.shtml

Richard Reynolds, Priest

M (RM)

Born in Devon, England, c. 1490; died at Tyburn on May 4, 1535; beatified in

1886; canonized by Pius VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England

and Wales.

Richard studied at

Cambridge, was elected a fellow of Corpus Christi College in 1510, and took the

degree of B.D. and was appointed university preachers in 1513. That same year,

he professed himself as a Bridgettine monk at Syon Abbey, Isleworth, and became

known for his sanctity and erudition. He was imprisoned when he refused to

subscribe to the Act of Supremacy issued by Henry VIII and was one of the first

martyrs hanged at Tyburn, after being forced to witness the butchering of four

other martyrs (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0504.shtml

Robert Lawrence, Priest M (RM)

Died at Tyburn on May 4, 1535; beatified in 1886; canonized by Pius VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. Saint Robert was prior of the charterhouse of Beauvale, Nottinghamshire, England. He was on a visit to the London charterhouse, as was Saint Augustine Webster, when they accompanied its prior, Saint John Houghton, to see Thomas Cromwell, who had them seized and imprisoned in the Tower of London. When they refused to sign the Act of Supremacy, which placed Henry VIII as head of the Church of England, they were savagely treated and hanged (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0504.shtml

Augustine Webster, O. Cart. M (RM)

Saint

Augustine Webster

Августин

Вебстер (ум. около 1531) - святой Римско-Католической Церкви

Died May 4, 1535; canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. After studying at Cambridge, Father Augustine became a Carthusian and then in 1531 prior of the charterhouse at Axholme, England. While on a visit to the London charterhouse, he accompanied Saint John Houghton and Saint Robert Lawrence to a meeting with Thomas Cromwell, who had the three arrested and imprisoned in the Tower. When they refused to accept the Act of Supremacy of Henry VIII, they were dragged through the streets of London, savagely treated, and executed at Tyburn outside London (Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0504.shtml

Richard Gwyn M (RM)

Born at Llanidloes, Montgomeryshire, Wales, in 1537; died at Wrexham, Wales, on

October 15, 1584; canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs

of England and Wales.

Richard Gwyn was raised a

Protestant, studied briefly at Saint John's College, Cambridge. He returned to

Wales in 1562, opened a school at Overton, Flintshire, married, and had six

children. He left Overton after becoming a Catholic, when his absence from

Anglican services was noticed, but was arrested in 1579 at Wrexham, Wales.

He escaped but was again

arrested in 1580 and imprisoned at Ruthin. He was brought up before eight

assizes, tortured, and fined in between, and four years later, in 1584, he was

convicted of treason on charges by perjuring witnesses and sentenced to death.

During his time in

prison, he wrote numerous religious poems in Welsh. He was hanged, drawn, and

quartered at Wrexham--the first Welsh martyr of Queen Elizabeth I's reign. He

is the protomartyr of Wales (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1017.shtml

John Stone, OSA Priest M (RM)

Born in Canterbury, England; died there 1538-1539; canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales; feast day formerly May 12. John was an Augustinian friar of the Canterbury community. He held a doctorate in Divinity and was highly respected for his erudition. He served as a professor and prior at Droitwich for a time but was back at Canterbury when Henry VIII began his divorce proceedings. John denounced the claims of Henry to ecclesiastical supremacy from the pulpit, was arrested in December 1538, imprisoned at Westgate, and when he reiterated his condemnation of the Act of Supremacy, was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Canterbury before December 1539 (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1227.shtml

Margaret Ward M (RM)

Born at Congleton, Cheshire, England; died August 30, 1588; beatified in 1929;

canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and

Wales. The gentlewoman Margaret was serving as a companion in the home of the

Whittle family in London when she was arrested together with her servant,

Blessed John Roche, for helping Father Richard (William?) Watson to escape from

Bridewell Prison. She had smuggled a rope into the priest's cell so that he

might climb down from the roof. He was injured, but did escape with the help of

John Roche. The rope was traced back to Margaret, who was severely tortured.

They were tried at the Old Bailey on August 29, and offered their freedom if

they would reveal the whereabouts of Watson and convert to the Protestant

faith. Upon refusing, they were hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn,

together with a priest and three other laymen (Benedictines, Delaney, Farmer,

Kalberer).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0830.shtml

Philip Howard M (RM)

Born in 1557; died October 19, 1595; beatified in 1929; canonized by Pope Paul

VI in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

Philip was the eldest son

of Thomas Howard, fourth duke of Norfolk, who had been beheaded under Queen

Elizabeth I in 1572. Philip's godfather was Philip II of Spain. On his mother's

side, Philip was earl of Arundel and Surrey. His life's story is not so

surprising given this heritage of high-birth and martyrdom.

Although Philip was baptized

as a Catholic, he was raised as a Protestant. For years he was an indifferent

Christian, neglectful of his faith. At the tender age of 12 or 14, he was

married to Anne Dacre, his foster sister. He studied at Cambridge for two

years. Although Queen Elizabeth had executed his father, she made Philip one of

her favorites. The son was dazzingly handsome, witty, and a good dancer. Philip

became a wastrel at Elizabeth's court, involved in many love affairs, refusing

to set eyes on his young wife who waited patiently at Arundel House.

Even during this period

of dissipation, Philip was extravagant in helping the poor and sick. He

servants worshipped him because he treated every individual courteously. About

this time his grandfather died and he inherited the title and estates of the

earl of Arundel. Deeply impressed by Saint Edmund Campion when he debated

theology with the deans of Windsor at London, Philip reformed his life, was

reconciled to his neglected wife, and eventually fell deeply in love with her.

About the same time as

Campion's defense of the faith, Anne Dacre and Philip's favorite sister, Lady

Margaret Sackville, were reconciled to the Catholic Church. Elizabeth

immediately banished Anne Dacre and placed her under house arrest in Surrey,

where she gave birth to their first daughter. Philip was imprisoned in the

Tower of London for a short time. Upon his release, he, too, returned to the

Catholic Church in 1584 with fervor and conscientiousness.

In late April 1585,

Philip tried to escape across the English Channel to Flanders with his family

and brother William as so many Catholics of his country had done before. But

the captain of the ship he had hired betrayed him. Again, he was thrown into

the Tower, where he was severely beaten and accused of treason for working with

Mary, Queen of Scots. The charge was not provable, but he was fined 10,000

pounds. His pleas for mercy and to be allowed to see his wife, daughter, and

newborn son went unanswered by the queen.

On various occasions it

was reported to his wife that the earl was drinking in prison, that he had

affairs with all kinds of loose women, and was entirely indifferent to

religious concerns. Even where he was at the point of death in 1596, it was

made a condition that he must renounce his faith if he wanted to see Anne and

the children before he died.

At the time of the

Spanish Armada, he was again accused of treason (though he was in the Tower of

London at the time) and ordered executed--a sentence that was never carried

out. He was kept imprisoned in the Tower and died there six years later, on

October 19, perhaps poisoned (Benedictines, Delaney, Undset).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1019.shtml

John Jones, OFM Priest M

(AC)

Born at Clynog Fawr, Carnarvonshire, Wales; died July 12, 1598; beatified in

1929; canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England

and Wales. Born of a Catholic family, John Jones was ordained at Rheims and in

1587 was working among the Catholic prisoners in Marshalsea Prison in London.

He was discovered, imprisoned at Wisbech Castle, but managed to escape to the

Continent.

He joined the Franciscans

of the Observants, probably at Pontoise, France, and was professed at Ara Coeli

Convent in Rome. He received permission to return to England in 1592, using the

alias John Buckley, worked in London and other parts of England, and was

arrested again in 1596.

He was imprisoned for two

years (he brought Blessed John Rigby back to the faith while in prison), and

when convicted of being a Catholic priest guilty of treason for having been

ordained abroad and returned to England, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at

Southwark in London (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0712.shtml

Thomas Garnet, SJ Priest

M (AC)

Born at Southwark; died 1608; beatified 1929; canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI

as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. Born into a distinguished

Catholic family, Thomas Garnet was the nephew of the famous Jesuit, Father

Henry Garnet, and the son of Richard Garnet, a faithful Catholic who had been a

distinguished fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. His early education was at

Horsham Grammar School, but at the age of 16 or 17, he was sent to the newly

opened College of Saint Omer in France. In January 1595, he and several of the

other students set sail for Spain, but not until 14 months later, after many

adventures which included a term of imprisonment in England, did he succeed in

reaching Spain and the English Jesuit College at Valladolid. There, at the

close of his theological course, he was ordained a priest. He was then sent on

the English mission with Blessed Mark Barkworth in 1599. His manner of life for

the next six years he described in a few words in his evidence when on trial:

"I wandered from place to place to recover souls which had gone astray and

were in error as to the knowledge of the true Catholic Church."

In 1606, the year he

uncle was executed, Father Thomas Garnet was arrested near Warwick shortly

after the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot. First he was imprisoned in the

Gatehouse and then moved to Newgate. Because he had been staying in the house

of Mr. Ambrose Rookwood, who was implicated in the conspiracy, and because he

was so closely connected to Father Henry Garnet, it was hoped that important information

could be extracted from him, but neither threats nor the strictest

cross-examination could elicit any incriminating admission. After eight or nine

months spent in a damp cell with no better bed than the bare ground, he was

deported to Flanders with 46 other priests. While still in England Saint Thomas

had been admitted to the Society of Jesus by his uncle, who was superior of the

Jesuits in England, and he now proceeded to Louvain for his novitiate. The

following year, in September, he returned to England. Six weeks later he was

betrayed by an apostate priest and arrested again.

At the Old Bailey he was

charged with high treason on the grounds that he had been made a priest by

authority derived from Rome and that he had returned to England in defiance of

the law. His priesthood he neither admitted nor denied, but he firmly refused

to take the Oath of Supremacy. On the evidence of three witnesses who declared

that when he was in the Tower he had signed himself Thomas Garnet, Priest, he

was declared guilty and was condemned to death.

On the scaffold he

proclaimed himself a priest and a Jesuit, explaining that he had not

acknowledged this at his trial lest he should be his own accuser or oblige the

judges to condemn him against their consciences. The Earl of Essex and others

tried up to the last moment to persuade him to save his life by taking the

oath, and when the end came and the cart was drawn away they would not allow

him to be cut down until it was certain he was quite dead (Benedictines, Delaney,

Walsh).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0623.shtml

John Kemble, Priest MM

(RM)

Born at Saint Weonard's, Herefordshire, England, in 1599; died at Hereford, in

1679; beatified in 1929; canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty

Martyrs of England and Wales.

John Kemble was born to

Catholic parents, studied for the priesthood at Douai, and was ordained in

1625. He then labored in the English mission in Herefordshire and Monmouthshire

for 53 years. During the hysteria, in 1678, surrounding the Titus Oates Plot,

Father Kemble was arrested at Pembridge Castle, his brother's home, which he

had used as his headquarters. He was charged with complicity in the fraudulent

plot to assassinate King Charles II. When no evidence could be found of his

involvement, he was examined by the Privy Council in London and found guilty of

being a Catholic priest. The 80-year-old Father Kemble was so respected that he

was allowed to die upon the gallows before the other grisly rituals of the

drawing and quartering were carried out. Thus, he was thus spared much of the

agonies that others suffered. One of his hands was cut off and is kept as a

relic in the Catholic Church in Monmouth (Benedictines, Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0822.shtml

John Wall, OFM Priests M (RM)

Born near Preston, Lancashire, England; died at Redhill, Worcester on August

22, 1679; beatified in 1929; canonized in 1970 by Pope Paul VI as one of the

Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. John had his early education at Douai,

France, then completed his studies for the priesthood at the Roman college and

was ordained in Rome in 1645. He served as a missionary for a time. When Father

John Wall entered the Friars Minor in 1651 at Saint Bonaventure's in Douai, he

took the new name of Father Joachim of Saint Anne. He joined the English

mission at Worcester in 1656, where he labored under the aliases of Francis

Johnson, Dormer, and Webb until his arrest 22 years later in December 1678 at

Bromsgrove. After being imprisoned for five months, he was acquitted of any

complicity in the Titus Oates Plot. Nevertheless, he was hanged, drawn, and

quartered for refusing to deny the faith and his priesthood

(Benedictines,Delaney).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0822.shtml

CANONIZATION OF 40

ENGLISH AND WELSH MARTYRS

Paolo Molinari, S.J.

Who the Forty Martyrs are

The forty Martyrs are

among the best known of the many Catholics who gave their lives in England and

Wales during the 16th and 17th centuries owing to the fact that their religious

convictions clashed with the laws of the State at that time.

As is known, King Henry

VIII had proclaimed himself supreme head of the Church in England and Wales,

claiming for himself and his successors power over his subjects also in

spiritual questions. According to our Catholic faith, this spiritual supremacy

is due only to the Vicar of Christ, the Roman Pontiff. The Blessed Martyrs, and

with them many other Catholics, though they wished to be, and actually were,

loyal subjects of the Crown in everything belonging to it legitimately

according to the ideas of that time, refused for reasons of conscience to

recognize the "spiritual supremacy" of the King and to obey the laws

issued by the political power on purely spiritual questions such as Holy Mass,

Eucharistic Communion and similar matters. This was what led many people to face

and meet death courageously rather than act against their conscience and deny

their Catholic faith as regards the spiritual Primacy of the Vicar of Christ

and the dogma of the Blessed Sacrament. From the ecumenical point of view, it

is extremely important to realize the fact, proved historical, that the Martyrs

were not put to death as a result of internal struggles between Catholics and

Anglicans, but precisely because they were not willing to submit to a claim of

the State which is commonly recognized today as being illegitimate and

unacceptable.

If—as has always been

clearly recognized in the case of St. Thomas More—it would be a serious error

to consider him a leading figure in the opposition between Catholics and

Anglicans, whereas he must be considered a person who rose in defence of the

rights of conscience against State usurpation, the same can be said of the 40

Martyrs, who died for exactly the same reasons.

And this is just what the

Church intends to stress with their Canonization. It was and is her intention

to hold up to the admiration not only of Catholics, but of all men, the example

of persons unconditionally loyal to Christ and to their conscience to the

extent of being ready to shed their blood for that reason. Owing to their

living faith in Christ, their personal attachment to Him, their deep sharing of

His life and principles, these persons gave a clear demonstration of their

authentically Christian charity for men, also when—on the scaffold—they prayed

not only for those who shared their religious convictions, but also for all

their fellow-countrymen it; and in particular for the Head of the State and

even for their executioners.

This firm attitude in

defence of their own freedom of conscience and of their faith in the truth of

the Primacy of Christ and of the Holy Eucharist is identical in all the 40

Martyrs. In every other respect, however, they are different as for example in

their state in life, social position, education, culture, age, character and

temperament, and in fact in everything that makes up the most typically

personal qualities of such a large group of men and women. The group is

composed, in fact, of 13 priests of the secular clergy, 3 Benedictines, 3

Carthusians, 1 Brigittine, 2 Franciscans, 1 Augustinian, 10 Jesuits and 7

members of the laity, including 3 mothers.

The history of their

martyrdom makes varied and stimulating reading as the different characters are

revealed, not without a touch of typically English humour.

The torments they

underwent give an idea of their fortitude. The priests—for example—were hanged,

and shortly after the noose had tightened round their neck they were drawn and

quartered. In most cases the second operation took place when they were still

alive, for they were not left hanging long enough to bring about their death,

sometimes only for a very few seconds.

For the others—that is,

those who were not priests—death by hanging was the normal procedure. But

before their execution the Martyrs were usually cruelly tortured, to make them

reveal the names of any accomplices in their "crime", which was

having celebrated Holy Mass, having attended it or having given shelter to

priests. In the course of the trial, and during the tortures, they were offered

their life and freedom on condition they recognized the king (or the queen,

according to the period), as head of the Church of England.

And here are some

particular features that drive home to us the spirituality of these Martyrs and

how they faced death.

Cuthbert Mayne, a secular

priest, replied to a gaoler who came to tell him he would be executed three

days later: "I wish I had something valuable to give you, for the good

news you bring me...".

Edmund Campion, a Jesuit, was so pleased when taken to the place of execution

that the people said about him and his companions: "But they're laughing!

He doesn't care at all about dying...'.

Ralph Sherwin, the first of the martyrs from the English College in Rome had heavy chains round his ankles that rattled at every step he took. "I have on my feet—he wrote wittily to a friend of his—some bells that remind me, when I walk, who I am and to whom I belong. I have never heard sweeter music than this..." He was executed immediately after Campion; he piously kissed the executioner's hands, still stained with the blood of his fellow martyr.

Alexander Briant—the diocesan priest who entered the Society of Jesus shortly before his death—had made himself a little wooden cross during his imprisonment, and held it clasped tightly between his hands all the time, even during the trial. It was then, however that they snatched it away from him But he replied to the judge: "You can take it out of my hands, but not out of my heart". The cross was later bought by some Catholics and is now in the English College in Rome.

John Paine (a secular priest, whose death was long mourned in the whole of

Chelmsford) kissed the gallows before dying; and Richard Gwyn, a layman

helped the hangman, overcome with emotion, to put the rope round his neck Some

strange and extremely revealing episodes are told about Gwyn. Once for example,

when he was in prison he was taken in chains to a chapel and obliged to stand

right under the pulpit where an Anglican preacher was giving a sermon. The

prisoner then began to rattle his chains, making such a din that no one could

hear a word of what was being said. Taken back again to his cell, he was

approached by various Protestant ministers. One of them, who had a purple nose,

wanted to dispute about the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven and asserted that God

had given them also to him, not just to St. Peter. "There is a

difference", Richard Gwyn retorted "St. Peter was entrusted with the

keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, while the keys entrusted to you are obviously

those of the beer cellar".

Cultured Elizabethan

society has its representatives among the martyrs Swithun Wells was

one of them. He had travelled a great deal; he had also been in Rome, and knew

Italian well. He was a sportsman, particularly fond of hunting. On his way to

the gallows, he caught sight of an old friend among the crowd and said to him:

'Farewell, my dear! And farewell too, to our fine hunting-parties. Now I've

something far better to do...". It was December 10th, 1591, and bitterly

cold. When they stripped him, he turned to his main persecutor, Topcliffe, and

said in a joking tone: "Hurry up, please Mr. Topcliffe. Are you not

ashamed to make a poor old man suffer in his shirt in this cold?"

Catholic priests managed

to exercise the ministry thanks to the precious collaboration of the faithful.

who welcomed them and kept them hidden in their homes and facilitated the

celebration of Holy Mass. As can well be understood, now and again some one

would betray them. The Jesuit laybrother, Nicholas Owen, was famous for

the many hiding-places he built in numerous houses all over England. Arrested

and imprisoned in the Tower of London, he died while being brutally tortured.

Of the forty Martyrs, the

one who underwent the most torture was Henry Walpole, a Jesuit priest. His

exceptional physique resisted the most atrocious forms of torture for as many

as 14 times, until the gallows put an end to his sufferings.

The following inscription

can still be read in the Tower of London, in one of the cells in which the

Martyrs were detained: "Quanto plus afflictionis pro Christo in hoc

saeculo, tanto plus gloriae in futuro" (the more suffering for Christ in

this life, the more glory in heaven). The words were carved by Philip

Howard, Earl of Arundell. He was the queen's favourite when he made his

appearance at court, at the age of 18, leading a dissolute life. At the age of

24, he happened to be present at a discussion between Campion and some

Protestant ministers. The holy Jesuit's words made a deep impression on him; as

a result he was converted to Catholicism. As he was about to flee to the

continent. he was captured and thrown into prison. He spent eleven long years there,

reading, praying and meditating. He was condemned to death, but the sentence

was postponed by the Queen's intervention. He fell seriously ill and died in

prison.

A curious fact happened

to the Franciscan John Jones. At the time of his execution, the hangman

found he had forgotten the rope. The martyr took advantage of the hour's wait

to speak to the crowd and to pray.

What is most striking is

the serenity with which they all met death. Some of them even made witty,

humorous remarks.

Thus, for example the

Benedictine; John Roberts, seeing that a fire was being lit to burn his

entrails—after hanging and quartering—made the sally: "I see you are preparing

us a hot breakfast!".

When someone shouted at

the Jesuit Edmund Arrowsmith: "You've got to die, do you

realize?", he replied calmly: "So have you, so have you, my good

man...". It is testified that Alban Roe a Benedictine religious,

was a very entertaining fellow. In spite of the torture that was inflicted on

him in prison he found the courage to invite the wardens to play cards with

him, telling funny stories. He gave all the money he had to the executioner to

drink to his health, warning him not to get drunk, however.

Philip Evans, having

found a particularly kind judge, was treated somewhat indulgently in prison, so

much so that he could even play tennis. Well, it was just during a game that

the news of his condemnation to death arrived. He continued to play, as if

nothing had happened. Then he picked up his harp and began to play.

John Kemple, a secular

priest, was the only one who always refused to go into biding. "I'm too

old now—he would say—and it is better for me to spend the rest of my life

suffering for my religion". Of course he was caught and arrested. Before

he was hanged, he asked to be allowed to smoke his inseparable pipe. The

executioner, who happened to be an old friend of his, was overcome with emotion

when the moment came to carry out his task and showed his hesitation. Then it

was the martyr who urged him on, saying: "My good Anthony, do what you

have to do. I forgive you with all my heart...".

The martyrdom of Margaret

Clitherow is particularly moving. She was accused "of having

sheltered the Jesuits and priests of the secular clergy, traitors to Her

Majesty the Queen"; but she retorted: "I have only helped the Queen's

friends". Margaret knew that the court had decided to condemn her to death

and, not wanting to make the jury accomplices in her condemnation, she refused

the trial. The alternative was to be crushed to death. When the terrible

sentence was passed, Margaret said: "I will accept willingly everything

that God wills".

On Friday March 25th,

1588, at eight o'clock in the morning, Margaret, just thirty-three years old,

left Ouse Bridge prison, barefooted, bound for Toll Booth, accompanied by two

police superintendents, four executioners and four women friends; she carried

on her arm a white linen garment. When she arrived at the dungeon, she knelt in

front of the officials, begging that she should not be stripped, but her prayer

was not granted. While the men looked away, the four pious women gathered round

her and before Margaret lay down on the ground they spread over her body the

white garment that the prisoner had brought with her for that purpose. Then her

martyrdom began.

Her arms were stretched

out in the shape of a cross, and her hands tightly bound to two stakes in the

ground. The executioners put a sharp stone the size of a fist under her back

and placed on her body a large slab onto which weights were gradually loaded up

to over 800 pounds. Margaret whispered: "Jesus, have mercy on me".

Her death agony lasted for fifteen minutes, then the moaning ceased, and all

was quiet.

These brief remarks on

some outstanding episodes of the martyrdom of the 40 Martyrs, and the quoting

of some of the words they uttered at the gallows, are sufficient to show what

was the ultimate reasons for their death and, at the same time, the sublimely

Christian state of mind of these heroes of the faith.

The history of the Cause

The history of the

Beatification and Canonization Cause of our forty blessed Martyrs is part of.

the wider history of a host of Martyrs who shed their blood in defence of the

Catholic religion in England, from the schism that began in the reign of Henry

VIII down to the end of the 17th century.

As early as the end of

1642 the first steps were taken to initiate the canonical process, but owing to

the persecutions that were still rife, this initiative had soon to be suspended

Nevertheless the victims of the persecution continued to be considered and

venerated as martyrs. The Cause to prove their martyrdom and the existence of

their cult was presented in Rome only in the second half of the last century,

that is, following upon the reconstitution of the Catholic hierarchy in England

and Wales, which took place in 1850.

The Cause of 254 martyrs

was introduced on December 9th, 1886, by Leo XIII. Shortly afterwards, on

December 29th 1886, the cult of 54 martyrs was confirmed by special decree,

then on May 13th, 1895, 9 others. Finally, with the Apostolic Letter Atrocissima

tormenta passi on December 15th, 1929, Pius XI beatified 136 victims of

this persecution, and on May 19th 1935 he solemnly canonized Cardinal John Fisher

and Chancellor Thomas More.

In still more recent

times, the Hierarchy of England and Wales, conscious of the deep devotion to

the martyrs who on different occasions had been declared blessed by the

apostolic See, and aware that this devotion was addressed especially to some of

the most popular of them was induced by the requests of the faithful and the

multiplicity of favours obtained, to promote the canonization not of the whole

host of these martyrs, but of a limited group of them. Right from the beginning

of the negotiations, the Canonization Cause of these Martyrs was entrusted by

the Hierarchy of England and Wales to Fr. Paolo Molinari, Postulator General of

the Society of Jesus and President of the College of Postulators. He in turn

nominated as Assistant Postulators Father Philip Caraman and James Walsh of the

English Province of the Society. When the former was put for some years at the

disposal of the Bishop of Oslo for certain important tasks, Father Clement

Tigar, S.J. took his place.

After patient and

laborious work, the list of the 40 martyrs chosen was presented by Fr. Molinari

to the Holy See on December 1st, 1960. After the usual practices the latter

proceeded, on May 24th 1961, with the so-called re-opening of the Cause by

means of the Decree <Sanctorum Insula>, issued by order of Pope John

XXIII.

Eleven of these forty

martyrs had been included among the blessed solely by a decree confirming their

cult. It was now necessary, in view of the hoped-for canonization, to make a

thorough historical re-examination of their martyrdom, which had not been

done ex professo when the Positio super introductione causue was

prepared last century. As is customary, this task was entrusted to the

Historical Section of the Sacred Congregation of Rites. Availing itself

essentially of the studies carried out under its direction by the General

Postulation of the Society of Jesus and by the office of the English

Vice-Postulation, it made a very favourable pronouncement on the material and

formal martyrdom of the eleven Blessed in question. The other studies

prescribed by law having been completed, His Holiness Paul VI signed the

special Decree of the Declaratio Martyrii of these eleven Blessed

Martyrs, on May 4th 1970. In preparing for this Decree, two volumes were

published in English and in Italian respectively of the Positio super

Martyrii et cultu ex officio concinnata (Official Presentation of

Documents on Martyrdom and Cult) (Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1968, pp. XLIV,

375 in folio) which in the judgment of international critics is a real model of

scientific editing of old texts.

Miracles attributed to

the Forty Blessed Martyrs

Even before the rehearing

of the Cause, many reports of favours and apparently miraculous cures

attributed to the intercession of our Blessed Martyrs, had come to the knowledge

of the Catholic Hierarchy of England and Wales, which hastened to inform the

competent Roman Authorities.

From the time when the

Cause of the 40 Blessed Martyrs was reopened, the ecclesiastical Hierarchy

called for a prayer campaign in all English dioceses. Its most outstanding

manifestations were various pilgrimages to the shrines of the Martyrs, diocesan

and interdiocesan rallies, and particularly "<Martyrs'

Sunday>", the yearly celebration of the memory of these Martyrs by all

dioceses and parishes.

As a result of the

intensification of the devotion of the faithful and their prayers, a good many

events took place which looked like miracles. Sufficient data were collected

about them to induce the Archbishop of Westminster, then Cardinal William

Godfrey, to send a description of 24 seemingly miraculous cases to the Sacred

Congregation.

The most striking of

these and of the others that continued to be notified to the Postulation were

first examined with special care by doctors of high repute. On the basis of

their answers, two cases were chosen and the usual Apostolic Proceedings were

instituted, and the acts were sent to the Sacred Congregation of Rites in Rome.

In the meantime requests

and pleas continued to arrive for the canonization of the 40 blessed Martyrs of

England and Wales as soon as possible. His Holiness Paul VI, duly informed

about the extremely favourable outcome of the discussion of the Medical Council

regarding one of the two above-mentioned cases, and keeping in mind the fact that

the blessed Thomas More and John Fisher, belonging to the same group of

Martyrs, had been canonized with a dispensation from miracles, considered that

it was possible to proceed with the Canonization on the basis of this one

miracle, after further discussions at the S. Congregation for the Causes of

Saints had taken place.

The same S. Congregation,

having issued the special Decree on July 30th, 1969, proceeded with the

examination of the miracle, that is, the cure of a young mother affected with a

malignant tumour (fibrosarcoma) in the left scapula, a cure which the Medical

Council had judged gradual, perfect, constant and unaccountable on the natural

plane.

After due assessment of

the case and the usual discussions within the S. Congregation for the Causes of

Saints, which concluded with an extremely favourable result on May 4th, 1970,

his Holiness Paul VI confirmed the preternatural character of this cure brought

about by God at the intercession of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and

Wales.

From the point of view of

canonical procedure, the way was now open for solemn Canonization if the

Sovereign Pontiff so decided.

There still remained

another problem, however, which had been carefully taken into account by the

Postulation right from the beginning, but which now had to be solved on the

basis of another thorough study, that is, the problem of the opportuneness of

this Canonization. While in fact the vast majority of English

Catholics—Bishops, clergy and laity—thorough study, that is, the problem of

faith to be raised to the honours of the altar, some voices had been raised in

repeated circumstances to say that canonization of these Martyrs might be

inopportune for ecumenical reasons.

Opportuneness of the

Canonization

In more recent times—November

1969—the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Ramsey, had expressed his apprehension

that this Canonization might rekindle animosity and polemics detriment to the

ecumenical spirit that has characterized the efforts of the Churches recently.

But the reaction of the press, lay, Anglican and Catholic, showed clearly that

this concern—though shared by some Anglicans and Catholics—did not correspond

to the view of the vast majority. Many people, in fact, both Anglicans and

Catholics, were aware of the fact that, right from the beginning of the

re-opening of the Cause, the policy of its Promoters had been characterized by

an extremely serene and ecumenical note; what is more, they realized the

positive repercussions it offers just in this field if it is presented in this

very spirit.

Right from the first

announcement of the Re-opening of the Cause of the 40 Martyrs, decreed by Pope

John XXIII on 24 May 1961, the Hierarchy of England and Wales let it be clearly

under stood that nothing was further from the intentions of the Bishops than to

stir up bad feelings and quarrels of the past.

The aim of the Postulator

General Paolo Molinari S.J. and his collaborators, James Walsh S.J., Philip

Caraman S.J. and Clement Tigar S.J., while they were carrying out the historical

research and investigation, was to ensure that the Cause would be presented in

an authentically ecumenical way.

For this reason the

Postulator General, always working in close contact with the authorities of the

S. Congregation that deals with the Causes of Saints and in agreement with the

Hierarchy of England and Wales, asked Cardinal Agostino Bea, then President of

the Secretariat for the Union of Christians, to act as the Cardinal Ponens of

the Cause Aware of its ecumenical significance, he sustained, promoted and

encouraged its course until he died. After his death the Secretariat itself

continued to follow attentively the individual phases of the Cause and not only

did not find any contrary motive but collaborated skillfully to ensure that the

approach would benefit the ecumenical cause, instead of hampering it. (See in

this connection the address that the present President of the Secretariat,

Card. Willebrands, delivered in the Anglican cathedral in Liverpool during his

recent visit to England).

The vast majority of

people understood all this. The most authoritative voice in this sense was that

of the British Council of Churches, which made a public declaration on the

matter on December 17th, 1969. Not only does it recognize the importance for

the Catholic Church to venerate its Martyrs, to whom the survival of the

Catholic Church in England and Wales is essentially due, but it also expressed

satisfaction that the various Christian denominations are united today in

recognizing the tradition of the Martyrs as a common element from which we must

all draw strength disregarding denominational frontiers.

Quite a few authoritative

persons—including several Anglican Bishops—keeping in mind and appreciating the

actions of considerable ecumenical value of Pope Paul VI on various

occasion—expressed the view and the hope that the Canonization of the 40

Martyrs might be an opportunity for the members of other Christian

denominations to make a positive gesture that would funkier the cause of union,

by joining in the admiration of Catholics for these Martyrs.

Ecumenical exchanges

Some months before the

Consistory the General Postulation, as well as the Vice-Postulation, had

charged specialized agencies with following the whole national and provincial

press of England and Wales, together with the European and American press, and

sending it constantly everything that was published in connection with the

Cause. At the same time it redoubled its efforts to obtain the widest and most

accurate information not only on the attitude of English and Welsh Catholics,

but above all on that of the Anglicans, with many of whose best qualified

representatives there had long existed relations marked by sincere and

brotherly frankness and a genuine spirit of mutual understanding and

collaboration. The Hierarchy of England and Wales, in its turn, and in the

first place Card. Godfrey's successor, His Eminence Card. Heenan,

Vice-President of the Secretariat for the Union of Christians, made a point of

establishing and maintaining exchanges of views with the competent authorities

of the various Christian denominations in their country.

On the basis of this huge

mass of material, it was established beyond al] shadow of doubt that at least

85 per cent of what had been printed in England and Wales, both on the Catholic

and the non-Catholic side, far from being unfavourable to the Cause, was

clearly in favour of it or at least showed great understanding for the

opportuneness of the canonization. This applies to publications such as "Church

Times", or the "Church of England Newspaper." and the most

widely read English national papers such as "The Times", "The

Guardian", "The Economist", "The Spectator" "The

Daily Telegraph", "The Sunday Times" and many others.

On the other hand some foreign

publications—including some well-known papers of protest—raised difficulties.

It was at once clear, however, that these were based on insufficient knowledge

of the complicated historical situation in which the Martyrs sacrificed their

lives, and, to an even greater degree, of the present ecumenical situation in

England. The latter calls for at least a minimum of concrete knowledge and

cannot easily be understood by those who do not take the trouble to study it

thoroughly Of course, everything possible has been done, by means of press

conferences and other opportune methods, to eliminate this type of

misunderstanding, generally most successfully.

A serious, serene and

objective study of the whole situation led to the conclusion, therefore, that

besides the numerous reasons clearly in favour of the canonization of the 40

blessed Martyrs, there were no real ecumenical objections to it, on the

contrary the canonization offered considerable advantages also from the genuinely

ecumenical point of view.

It was precisely these

ideas that His Holiness Paul VI expressed and explained in a masterly fashion

in the address he delivered on the occasion of the Consistory on May 18th,

1970, in which he announced his intention to proceed with the solemn canonization

of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and Wales on October 25th, 1970. In this

address the Holy Father, besides pointing out, with serene frankness and great

charity, the ecumenical value of this Cause, also laid particular stress on the

fact that we need the example of these Martyrs particularly today not only

because the Christian religion is still exposed to violent persecution in

various parts of the world, but also because at a time when the theories of

materialism and naturalism are constantly gaining ground and threatening to

destroy the spiritual heritage of our civilization, the forty Martyrs—men and

women from all walks of life—who did not hesitate to sacrifice their lives in

obedience to the dictates of conscience and the divine will, stand out as noble

witnesses to human dignity and freedom.

This declaration of the

Sovereign Pontiff was received with practically unanimous approval, which

showed how right the decision had been to proceed with the canonization. His

address was given a great deal of attention and certainly contributed

effectively to dispelling any doubts that may still have existed in certain

quarters.

At the same time the

Pope's words drive home to us unmistakably why the Church continues to propose

new Saints. The formal recognition of the holiness of some of her members has

the aim of presenting to the faithful and to all men the unshaken loyalty with

which they followed Christ and his law. It aims at letting us have, in a living

and existential way, the message that God addressed to us in his Son, who came

on earth to make us share his life and his love. It aims at making us

understand that, by welcoming his teaching and receiving Christ our Lord with

sincere hearts we already become participants in that life that will be granted

to us in its fullness when, having finished the course of our earthly existence

after being faithful to Him, we are admitted to his presence (cfr. Lumen

Gentium, 48).

Through these Saints it

is God himself who is speaking to us and helping us to understand how, in the

shifting circumstances of life, we must live our union with Him more and more

intensely and thus grow in holiness:

"For when we look at

the lives of those who have faithfully followed Christ, we are inspired with a

new reason for seeking the city which is to come (Heb. 13:14; 11:10). At the

same time we are shown a most safe path by which among the vicissitudes of this

world and in keeping with the state in life and condition proper to each of us,

we will be able to arrive at perfect union with Christ, that is, holiness. In

the lives of those who shared in our humanity and yet were transformed into

especially successful images of Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 3:18), God vividly manifests

to men His presence and His face. He speaks to us in them, and gives us a sign

of His kingdom, to which we are powerfully drawn, surrounded as we are by so

many witnesses (cf. Heb. 12:1), and having such an argument for the truth of

the gospel" (Lumen Gentium, No. 50).

The situations in which

we live may vary, but in the last analysis they have a deep element in common

which transcends time and circumstances. At the root of our existence there is

God's invitation, his offer to open our hearts to his love and respond in our

lives with authentic responsibility and consistency, to the claims of the love

of Him who gave his life for us

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano

Weekly Edition in English

29 October 1970

L'Osservatore Romano is

the newspaper of the Holy See.

The Weekly Edition in

English is published for the US by:

The Cathedral Foundation

L'Osservatore Romano

English Edition

320 Cathedral St.

Baltimore, MD 21201

Subscriptions: (410)

547-5324

Fax: (410) 332-1069

lormail@catholicreview.org

Provided Courtesy of:

Eternal Word Television

Network

5817 Old Leeds Road

Irondale, AL 35210

www.ewtn.com

SOURCE : http://www.ewtn.com/library/MARY/40MARTYR.HTM

May

4 – The Forty Martyrs of England and Wales (16th-17th centuries: details)

The image here is of St Margaret Clitherow, the

“pearl of York”, a married woman who held Masses in her house and sheltered

priests. She suffered a horrific death. For details of her life and death,

see 26th

March. Here Patrick Duffy gives the details of the lives and deaths of

each of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

3 Carthusians:

The Carthusians were all priors of different

Charterhouses houses of the Carthusian Order). Summoned in 1535 by

Secretary of State Thomas Cromwell to sign the Oath of Supremacy, they declined

and by virtue of their Carthusian vow of silence refused to speak in their own

defence.

Augustine Webster was educated at Cambridge and

was prior of the Carthusian house of Our Lady of Melwood at Epworth, on the

Isle of Axholme, North Lincolnshire in 1531.

John Houghton was born c. 1486 and educated at

Cambridge. He joined the London Charterhouse in 1515. In 1531, he became abbot

of the Charterhouse of Beauvale in Nottinghamshire but was then elected Prior

of the London house, to which he returned.

Robert Lawrence served as prior of the

Charterhouse at Beauvale, Nottinghamshire.

The three were cruelly tortured and executed at

Tyburn, making them among the first martyrs from the order in England. They

were beatified in 1886.

1 Augustinian friar: John Stone d. 1538

John Stone was a doctor of theology living in the

Augustinian friary at Canterbury. He publicly denounced the behaviour of King

Henry VIII from the pulpit of the Austin Friars and publicly stated his

approval of the status of monarch’s first marriage – clearly opposing the

monarch’s wish to gain a divorce. In 1538, in consequence of the Act of

Supremacy, Bishop Richard Ingworth (a former Dominican, and by then Bishop of

Dover) visited the Canterbury friary as part of the process of the dissolution

of monasteries in England. Ingworth commanded all of the friars to sign a deed

of surrender by which the King should gain possession of the friary and its

surrounding property. Most did, but John Stone refused and even further

denounced bishop Ingworth for his compliance with the King’s desires. He was executed

at the Dane John (Dungeon Hill), Canterbury, for his opposition to the King’s

wishes.

1 Brigittine: Richard Reynolds 1492-1535

The Brigittines were an order of monks founded by St

Bridget of Sweden.

Richard was born in Devon in 1492 and educated at

Cambridge. In 1513, he entered the Brigettines at Syon Abbey, Isleworth. When

Henry VIII demanded royal oaths, Richard was along with the Carthusian priors

who were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn Tree in London after being

dragged through the streets in 1535.

Two Franciscans

John Jones

(Friar Observant – also known as John Buckley, John

Griffith, or Godfrey Maurice)

John Jones was from a good Welsh and strongly Catholic

family. As a youth, he entered the Observant Franciscan convent at Greenwich;

at its dissolution in 1559 he went to the Continent, and took his vows at

Pontoise, France. After many years, he journeyed to Rome, where he stayed at

the Ara Coeli convent of the Observants (A branch of the Franciscan Order of

Friars Minor that followed the Franciscan Rule literally) . There he joined the

Roman province of the Reformati (a stricter observance branch of the Order of

Friars Minor). In 1591, he requested to return on mission to England. His

superiors, aware that such a mission usually ended in death, consented and John

also received a special blessing and commendation from Pope Clement VIII.

Reaching London at the end of 1592, he stayed

temporarily at the house which Father John Gerard SJ had provided for

missionary priests; he then laboured in different parts of the country. His

brother Franciscans in England elected him their provincial. In 1596 a

notorious priest catcher called Topcliffe had him arrested and imprisoned for

nearly two years. During this time he met, and helped sustain in his faith,

John Rigby. On 3 July 1598 Father Jones was tried on the charge of “going over

the seas in the first year of Her majesty’s reign (1558) and there being made a

priest by the authority from Rome and then returning to England contrary to

statute” . He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to being hanged,

drawn, and quartered.

The execution was to take place in the early morning

at St. Thomas’ Watering, in what is now the Old Kent Road, at the site of the

junction of the old Roman road to London with the main line of Watling Street.

Such ancient landmarks had been immemorially used as places of execution,

Tyburn itself being merely the point where Watling Street crossed the Roman

road to Silchester. The executioner had forgotten his ropes! In the delay

while the forgetful man went to collect his necessary ropes John Jones took the

opportunity to talk to the assembled crowd. He explained the important

distinction – that he was dying for his faith alone and had no political