Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Henryk Siemiradzki, Les Torches de Néron

(Lumières guidant la Chrétienté), huile sur toile, 385 x 704, 1876, National Museum Kraków

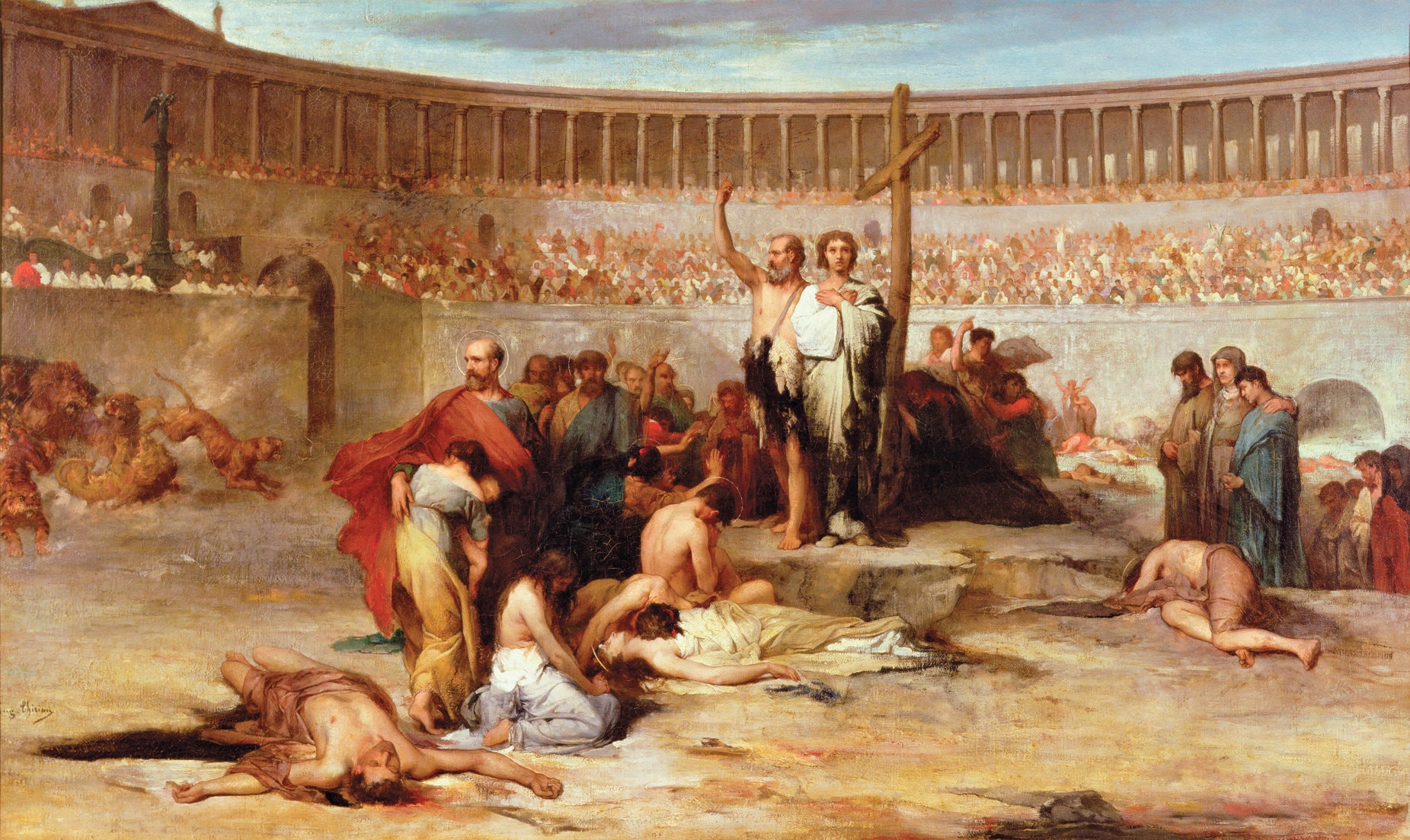

Henryk Siemiradzki, Nero's

Torches, 1876, 385 x 704, National Museum in Kraków

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Henryk Siemiradzki, Les Torches de Néron

(Lumières guidant la Chrétienté), huile sur toile, 385 x 704, 1876, National Museum Kraków

Henryk Siemiradzki, Nero's

Torches, 1876, 385 x 704, National Museum in Kraków

Saints Premiers martyrs

de Rome

(+64)

Injustement accusés par Néron de la responsabilité de l'incendie de Rome, cité qui, selon l'Apocalypse, "se saoulait du sang des témoins de Jésus." Ils furent livrés aux bêtes, éclairèrent les fêtes de Néron en brûlant comme des torches dans les jardins de Rome où ils furent torturés pour le plaisir sadique de leurs bourreaux.

Mémoire des premiers saints martyrs de la sainte Église romaine. En 64, après

l'incendie de la ville de Rome, l'empereur Néron accusa faussement les

chrétiens de ce forfait et en fit cruellement périr un grand nombre: les uns,

revêtus de peaux de bêtes, furent exposés aux morsures des chiens; d'autres

crucifiés; d'autres transformés en torches, afin qu'à la chute du jour ils

servissent d'éclairage nocturne dans le cirque. Tous étaient disciples des

Apôtres; ils furent les premiers des martyrs que l'Église romaine offrit au

Seigneur.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1413/Saints-Premiers-martyrs-de-Rome.html

Les premiers martyrs de l'Eglise

de Rome

Publié le 29 juin

2010 par jardinier de Dieu

30 juin

En l’an 64, date à

laquelle furent martyrisés les chrétiens de Rome, l’empereur régnant était trop

célèbre Néron. Celui-ci avait eu pour maître le philosophe Sénèque. Après avoir

suivi ses conseils et gouverné avec douceur et sagesse, il deviendra celui que

l’histoire jugera comme fou sanguinaire ...

Ce que nous savons de sa

responsabilité dans l’affaire des premiers martyrs de Rome, nous vient

essentiellement de l’historien païen Tacite. Tout peut mener aux pires excès,

même des goûts d’artiste. Néron trouvait certains quartiers de Rome mal bâtis

et laids, et il en souffrait. Lorsque, en 64, un terrible incendie les

détruisit en partie, la rumeur courut, non sans fondement, bien qu’il soit

difficile d’apporter des preuves, qu’il en était responsable. Il prit peur et

fit diversion en accusant les membres d’une secte nouvelle que l’on considérait

comme des ennemis du genre humain, et que l’on appelait les chrétiens.

Tacite, qui partageait

l’opinion de ses contemporains païens au sujet des disciples du Christ, mais

qui n’approuva pas la cruauté de Néron, nous dit qu’ils furent très nombreux à

être suppliciés. Certains cousus dans des peaux de bêtes, furent livrés aux

chiens. D’autres périrent crucifiés, d’autres encore, enduits de poix,

servirent de torches pour éclairer les jardins impériaux sur la colline du

Vatican. Parmi ces martyrs, il y avait des femmes. Des auteurs anciens pensent

que Pierre périt en ces jours-là.

La lettre de St Paul aux

Romains a été rédigée vers l’an 57. Beaucoup, parmi les martyrs de Néron,

l’avaient donc lue et méditée. Comment n’auraient-ils pas puisé dans ce passage

magnifique choisi pour célébrer leur triomphe, le courage de confesser leur foi

jusqu’au bout ? On se plaît à reprendre ici ce texte qui peut nous encourager,

nous aussi, à persévérer dans les épreuves de cette vie, même si nous ne sommes

pas appelés au martyr du sang : Qui pourra nous séparer de l’amour du Christ ?

La détresse ? L’angoisse ? La persécution ? La faim ? Le dénuement ? Le danger

? Le supplice ? .. J’en ai la certitude … rien ne pourra nous séparer de

l’amour de Dieu qui est en Jésus-Christ notre Seigneur.

Marcel DRIOT, 1995. Le Saint du jour. Médiaspaul, Paris, p.189

SOURCE : http://jardinierdedieu.fr/article-les-premiers-martyrs-de-l-eglise-de-rome-53163151.html

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Gustave Doré,

Les Martyrs Chrétiens, 1871, 139.7 x 213.4, Musée

d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg – MAMCS (67)

Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Christian Martyrs,

1871, 139.7 x 213.4, Strasbourg Museum

of Modern and Contemporary Art

LES

MARTYRS DES JARDINS DE NÉRON A ROME VERS LE Ier AOUT DE L'AN 64

Le 59 juillet 64,

commença l'incendie de Rome, qui dura neuf jours. Quand il fut éteint, une

immense population réduite au plus complet dénuement s'entassa aux enviions du

Champ de Mars, où Néron fit dresser des baraques et distribuer du pain et des

vivres. D'ordinaire, ces oisifs acclamaient l'empereur; maintenant qu'ils

avaient faim, ils le haïrent. Des accusations persistantes poursuivaient le

pitre impérial. On savait qu'il était venu d'Antium pour jouir de l'effroyable

spectacle dont la sublime horreur le transportait; on racontait même, ou du

moins on insinuait, que lui-même avait ordonné ce spectacle, tel qu'on n'en

avait jamais vu de pareil. Les accusations se haussaient jusqu'à la menace.

Néron, qui le sut, essaya de détourner les soupçons en jetant à la foule un nom

et une proie. Il y en avait un tout trouvé. En brûlant Rome, Néron avait blessé

au vif les préjugés tenaces d'un peuple conservateur au plus haut degré de ses

monuments religieux. Toute la friperie liturgique du paganisme, trophées, ex-votos,

dépouilles opimes, pénates, tout le matériel religieux du culte avait flambé.

L'horreur avait sa source dans le sentiment très vif de la religion et de la

patrie outragées. Or il y avait, à Rome même, un groupe de population que son

irréductible protestation contre les dieux de l'empire signalait à tous,

c'était la colonie juive ; une circonstance semblait accablante contre eux dans

l'enquête sur la responsabilité des récents désastres. Le feu avait pris dans

les échoppes du Grand-Cirque, occupées par des marchands orientaux, parmi

lesquels étaient beaucoup de Juifs. Mais il avait épargné la région de la

porte Capène et le Transtevère, dont les Juifs formaient presque exclusivement

la population. Ils n'avaient donc souffert quelque dommage qu'au Champ de Mars.

De là à inculper les Juifs il y avait peu à faire, cependant ils échappèrent ;

c'est que Néron était entouré de Juifs : Tibère Alexandre et Poppée étaient au

plus haut point de leur faveur ; dans un rang inférieur, des esclaves, des

actrices, des mimes, tous juifs et fort choyés. Est-ce trop s'avancer, que

d'attribuer à ce groupe l'odieux d'avoir fait tomber sur les chrétiens la

vengeance menaçante? Il faut se rappeler l'atroce jalousie que les Juifs

nourrissaient contre les chrétiens, et si on la rapproche « de ce fait

incontestable que les Juifs, avant la destruction de Jérusalem, furent les

vrais persécuteurs des chrétiens et ne négligèrent rien pour les faire

disparaître », on y trouvera le commentaire authentique d'un mot de saint

Clément Romain, qui, faisant allusion aux massacres de chrétiens ordonnés par

Néron, les attribue « à la jalousie, dia Zelon ».

Quand la rumeur se

répandit, à l'aide de ce que nous appellerions aujourd'hui « la pression

officielle », on fut surpris de la multitude de ceux qui suivaient la doctrine

du Christ, laquelle n'était autre chose, aux yeux du plus grand nombre, qu'un

schisme juif. Les gens sensés trouvèrent l'artifice pitoyable; l'accusation

d'incendie portée contre ces pauvres gens ne tenait pas debout; « leur vrai

crime, disait-on, c'est la haine du genre humain ».

Néanmoins on ne s'apitoya

pas longtemps, car on allait s'amuser. En effet, les jeux que l'on donna

dépassèrent en horreur tout ce que l'on avait jamais vu. Tacite et le pape

saint Clément nous ont laissé quelques traits de ces jeux, qui durèrent

peut-être plusieurs jours; nous donnons plus loin leurs trop courts récits,

dont la brièveté ne peut se passer du commentaire que l'on va lire.

« A la barbarie des

supplices, cette fois, on ajouta la dérision. Les victimes furent gardées pour

une fête, à laquelle on donna sans doute un caractère expiatoire. Rome compta

peu de journées aussi extraordinaires. Le ludus matutinus, consacré aux

combats d'animaux, vit un défilé inouï. Les condamnés, couverts de peaux de

bêtes fauves, furent lancés dans l'arène, où on les fit déchirer par des chiens

; d'autres furent crucifiés ; d'autres, enfin, revêtus de tuniques trempées

dans l'huile, la poix ou la résine, se virent attachés à des poteaux et

réservés pour éclairer la fête de nuit. Quand le jour baissa, on alluma ces

flambeaux vivants. Néron offrit pour le spectacle les magnifiques jardins qu'il

possédait au delà du Tibre et qui occupaient l'emplacement actuel du Borgo, de

la place et de l'église de Saint-Pierre. Il s'y trouvait un cirque, commencé

par Caligula, continué par Claude, et dont un obélisque, tiré d'Héliopolis

(celui-là même qui marque de nos jours le centre de la place Saint-Pierre),

était la borne. Cet endroit avait déjà vu des massacres aux flambeaux.

Caligula, en se promenant, y fit décapiter, à la lueur des torches, un certain

nombre de personnages consulaires, de sénateurs et de clames romaines. L'idée

de remplacer les falots par des corps humains, imprégnés de

substances inflammables, put paraître ingénieuse. Comme supplice,

cette façon de brûler vif n'était pas neuve; mais on n'en avait jamais fait un

système d'illumination. A la clarté de ces hideuses torches, Néron, qui avait

mis à la mode les courses du soir, se montra dans l'arène, tantôt mêlé au

peuple en habit de jockey, tantôt conduisant son char et recherchant les

applaudissements. Il y eut pourtant quelques signes de compassion. Même ceux

qui croyaient à la culpabilité des chrétiens et qui avouaient qu'ils avaient

mérité le dernier supplice eurent horreur de ces cruels plaisirs. Les hommes

sages eussent voulu qu'on fit seulement ce qu'exigeait l'utilité publique,

qu'on purgeât la ville d'hommes dangereux, mais qu'on n'eût pas l'air de

sacrifier des criminels à la férocité d'un seul.

« Des femmes, des vierges

furent mêlées à ces jeux horribles. On se fit une fête des indignités sans nom

qu'elles souffrirent. L'usage s'était établi, sous Néron, de faire jouer aux

condamnés, dans l'amphithéâtre. des rôles mythologiques entraînant la mort de

l'acteur. Ces hideux opéras, où la science des machines atteignait à des effets

prodigieux, étaient chose nouvelle ; la Grèce eût été surprise si on lui eût

suggéré une pareille tentative pour appliquer la férocité à l'esthétique, pour

faire de l'art avec la torture. Le malheureux était introduit dans l'arène,

costumé en dieu ou en héros voué à la mort, puis représentait, par son

supplice, quelque scène tragique des fables consacrées par les sculpteurs et

les poètes. Tantôt c'était Hercule furieux brûlé sur le mont Oeta, arrachant de

dessus sa peau la tunique de poix enflammée ; tantôt Orphée mis eu pièces par

un ours, Dédale précipité du ciel et dévoré par les bêtes, Pasiphaé subissant

les étreintes du taureau, Atys meurtri ; quelquefois c'étaient d'horribles

mascarades, où les hommes étaient accoutrés en prêtres de Saturne, le manteau

rouge sur le dos, les femmes en prêtresses de Cérès, portant les bandelettes au

front ; d'autres fois enfin, des pièces dramatiques, au courant desquelles le

héros était réellement mis à mort, comme Lauréolus, ou bien des représentations

d'actes tragiques, comme celui de Mucius Scaevola. A la fin, Mercure, avec une

verge de fer rougie au feu, touchait chaque cadavre pour voir s'il remuait; des

valets masqués, représentant Pluton ou l'Orcus, traînaient les morts par les

pieds, assommant avec des maillets tout ce qui palpitait encore.

« Les dames

chrétiennes les plus respectables durent se prêter à ces monstruosités. Les

unes jouèrent le rôle des Danaïdes, les autres celui de Dircé. Il est difficile

de dire en quoi la fable des Danaïdes pouvait fournir un tableau sanglant. Le

supplice que toute la tradition mythologique attribue à ces femmes coupables,

et dans lequel on les représentait, n'était pas assez cruel pour suffire aux plaisirs

de Néron et des habitués de son amphithéâtre. Peut-être défilèrent-elles

portant des urnes et reçurent-elles le coup fatal d'un acteur figurant Lyncée.

Peut-être vit-on Amymone, l'une des Danaïdes, poursuivie par un satyre et

violée par Neptune. Peut-être enfin ces malheureuses traversèrent-elles

successivement devant les spectateurs la série des supplices du Tartare et

moururent-elles après des heures de tourments.

« Quant aux supplices des

Dircés, il n'y a pas de doute. On connaît le groupe colossal désigné sous le

nom de Taureau Farnèse, maintenant au musée de Naples. Amphion et Zethus

attachent Dircé aux cornes d'un taureau indompté, qui doit la traîner à travers

les rochers et les ronces du Cithéron. Ce médiocre marbre rhodien, transporté à

Rome dès le temps d'Auguste, était l'objet de l'universelle admiration. Quel

plus beau sujet pour cet art hideux que la cruauté du temps avait mis en vogue

et qui consistait à faire des tableaux vivants avec les statues célèbres? Un

texte et une fresque de Pompei semblent prouver que cette scène terrible était

souvent représentée dans les arènes, quand on avait à supplicier une femme.

Attachées nues par les cheveux aux cornes d'un taureau furieux, les

malheureuses assouvissaient les regards lubriques d'un peuple féroce.

Quelques-unes des chrétiennes immolées de la sorte étaient faibles de corps ;

leur courage fut surhumain; mais la foule infâme n'eut d'yeux que pour leurs

entrailles ouvertes et leurs seins déchirés. »

TACITE, Annales,

liv. XV, ch. XLIV. — CLÉMENT ROMAIN, Epître aux Corinthiens, I, ch. III, V et

VI. — SUÉTONE, Néron, 16. — Pour la discussion des textes, leur valeur

critique, voyez : RENAN, Origines du christianisme, t. IV (cité ici pour

le commentaire du texte), p. 152 et suiv. — P. ALLARD, Hist. des Perséc.,

t. 1, p. 33 et suiv.: «L'incendie de Rome et les martyrs d'août 64. » —

Douais, La persécution des chrétiens de Rome en l'année 64, dans la Rev.

des Quest. hist. du 1er octobre 1885, en réponse à Recasa : : La

persécution des chrétiens sous Néron (1884).—Ramsay, The Church in the Roman

Empire (1884), p. 232 et suiv., et les ouvrages de DOULCET, MILMAN,

NEUMANN, traitant des rapports de l'Eglise avec l'Etat Romain. — BAUER, Christus

und die Caesaren (1877), p. 273. — ARNOLD, Die Neronische Christenverfolgung,

p. 105. — SCRILLER, Gesch. d. Kaiserrechts enter der Regierung des Nero,

p. 437. — Voyez la note de HOLBROOKE ad Tacit., Annal. XV, 44. —

ATTILIO PROFUMO, Le fonti ed i tempi dell' incendio neroniano, in-4°,

Roma, 1904.

1° TACITE (Annales, XV,

44)

Ni les efforts humains,

ni les largesses du prince, ni les prières aux dieux, ne détruisirent la

persuasion que Néron avait eu l'infamie d'ordonner l'incendie. Pour faire taire

cette rumeur, Néron produisit des accusés et livra aux supplices le plus raffinés

les hommes odieux à cause de leurs crimes que le vulgaire nommait « chrétiens

». Celui dont ils tiraient ce nom, Christ, avait été sous le règne de Tibère

supplicié par le procurateur Ponce-Pilate. Réprimée d'abord, l'exécrable

superstition faisait irruption de nouveau, non seulement en Judée, berceau de

ce fléau, mais jusque dans Rome, où reflue et sé rassemble ce qu'il y a partout

ailleurs de plus atroce et de plus honteux. On saisit d'abord ceux qui

avouaient; puis, sur leur déposition, une grande multitude, convaincue moins du

crime d'incendie que de la haine du genre humain. On ajouta la dérision au

supplice ; des hommes enveloppés de peaux de bêtes moururent déchirés par les

chiens, ou furent attachés à des croix, ou furent destinés à être enflammés et,

à la chute du jour, allumés en guise de luminaire nocturne. Néron avait prêté

ses jardins pour ce divertissement et y donnait des courses, mêlé à la foule en

habit de cocher, ou monté sur un char. Aussi, quoique coupables et dignes des

derniers supplices, on avait pitié de ces hommes, parce qu'ils étaient

sacrifiés, non à l'utilité publique, mais à la barbarie d'un seul.

2° SAINT CLÉMENT ROMAIN

(Epître, I, 6)

[A Pierre et à Paul] on

joignit une grande multitude d'élus qui endurèrent beaucoup d'affronts et de

supplices, laissant aux chrétiens un illustre exemple. Par l'effet de la

jalousie, des femmes, les Danaïdes et les Dircés, après avoir souffert de

terribles et monstrueuses indignités, ont atteint leur but dans la course

sacrée de la foi, et ont reçu la noble récompense, toutes faibles de corps

qu'elles étaient.

LES

MARTYRS. TOME I. LES TEMPS NÉRONIENS ET LE DEUXIÈME SIÈCLE.

Recueil de pièces authentiques sur les martyrs depuis les origines du

christianisme jusqu'au XXe siècle traduites et publiées par le B. P. DOM

H. LECLERCQ, Moine bénédictin de Saint-Michel de Farnborough. Précédé d’une

Introduction. Quatrième édition. Imprimi potest FR. FERDINANDUS CABROL, Abbas

Sancti Michaelis Farnborough. Die 4 Maii 1903. Imprimatur. Turonibus, die

18 Octobris 1920. P. BATAILLE, vic. Gen. Animulae Nectareae Eorginae Franciscae

Stuart.

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/martyrs/martyrs0001.htm#_Toc90633597

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904). Prière

des Martyrs chrétiens à Rome. 1863-1883, 87.9 X 150.1, Walters Art Museum

Saints premiers martyrs

de l'Eglise de Rome : par le sang versé

ARTICLE | 28/06/2003 |

Numéro 1328 | Par Marie-Christine Lafon

«Martyr»... le mot est

ancien.

Avec le Christ, sa

signification est nouvelle. D'origine grecque, «martyr» désigne une personne

capable de fournir des renseignements puisés dans sa mémoire, celui qui, ayant

vu ou entendu, se souvient et peut témoigner. En latin, on traduit

«testimonium», ce qui donne en français «témoin». On tua d'abord les chrétiens,

parce qu'ils étaient martyrs, témoins de Jésus ; ensuite, on appela martyrs

ceux-là qui avaient été tués pour leur Foi. Tout chrétien peut être appelé,

comme le Christ, à «rendre témoignage» (1) par le sang versé.

Ainsi, en juillet 64, un

violent incendie ravage durant plusieurs jours les quarts de Rome. Est-il dû au

hasard ou à la malignité de l'empereur Néron, qui voulait reconstruire la ville

à son idée ? On ne le sait. Aussi, pour effacer la rumeur selon laquelle

l'incendie a été ordonné par le prince, celui-ci condamne les chrétiens comme

responsables, et organise dans ses jardins des jeux dont ils seront les proies

des bêtes, ou les torches vivantes quand le jour déclinera...

Ils seront des centaines

à préférer subir la fureur d'un tyran que de cacher leur identité de chrétiens.

Parmi eux, très probablement, leur chef, Pierre.

Maintenant étendu sur sa

croix, Pierre se souvient de la nuit où il dit à Jésus sur le lac de Génésareth

: «Donne- moi l'ordre de venir à Toi en marchant sur les eaux». Comme à ce

moment-là, il a l'impression de s'enfoncer dans l'eau, il pousse le même cri :

«Seigneur, sauve-moi !» A cette seconde, Jésus lui avait tendu la main. On la

lui prend : le soldat lui plaque le poignet sur le bois. Plus que les coups de

marteau, Pierre sent la main de Jésus dans la sienne. «Jésus, je Te remercie de

m'avoir fait confiance... Merci pour tout le chemin fait ensemble. Tu sais, la

fin du parcours est difficile... oui, Tu sais.»

Des amis se sont glissés

dans les gradins le plus près possible de lui. «Dis-nous quelque chose !»,

«N'ayez pas peur, n'ayez pas peur.»

Dans le cirque,

désormais, il fait nuit. Pour lui, c'est l'aurore.

Marie-Christine Lafon

(1) Apocalypse 1, 5 ; 3,

14

(2) Pierre 4-15.

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Eugène

Thirion (1839-1910). Triomphe de la Foi. Martyrs chrétiens au temps de

Néron, 89 x 146, Collection particulière

PREMIERS MARTYRS DE

L’ÉGLISE DE ROME

Lundi 15 avril 2019,

par Secrétariat // LE

SAINT DU JOUR

Les Premiers martyrs de

l’Église de Rome concerne, suivant l’hagiographie catholique, le nom donné à un

groupe indéterminé de chrétiens victimes du premier épisode de persécution des

chrétiens qui prend place à Rome entre 64 et 68 à l’instigation de Néron à la

suite du grand incendie de Rome.

Un violent incendie se

déclare à Rome en 64, que les pompiers de l’Urbs ne peuvent maîtriser. La

rumeur court alors que la catastrophe serait le fait de Néron, désireux de

détruire les quartiers insalubres et de rebâtir la ville.

L’historien Tacite, tout

en étant réservé quant à l’origine de l’incendie (« Fut-il dû au hasard ou

à la malignité du prince, on ne sait ») rapporte dans ses Annales (XV, 44)

que l’empereur était incapable de faire taire la rumeur dévastatrice :

« Aucun moyen humain, ni largesses princières, ni cérémonies expiatoires

ne faisaient reculer la rumeur infamante d’après laquelle l’incendie avait été

ordonné ». Les chrétiens – un groupe religieux minuscule, encore mal distingué

des juifs – sont choisis comme boucs émissaires : « [Néron] supposa

des coupable et infligea des tourments raffinés à ceux que leurs abominations

faisaient détester et que la foule appelait "Chrétiens" ».

Tacite décrit les

supplices atroces auxquels les chrétiens sont soumis (et qui ont largement

alimenté l’iconographie chrétienne) : « On ne se contenta pas de les

faire périr ; on se fit un jeu de les revêtir de peaux de bêtes pour

qu’ils fussent déchirés par la dent des chiens, ou bien ils étaient attachés à

des croix et enduits de matières inflammables, quand le jour avait fui, ils

éclairaient les ténèbres comme des torches… ». Tacite n’a aucune attirance

personnelle pour cette « détestable superstition ». Cependant, à la

vue de ce spectacle horrible, il en vient à éprouver quelque sympathie :

« Aussi quoique ces gens fussent coupables et dignes des dernières

rigueurs on se mettait à les prendre en pitié ».

Sans se prononcer sur la

culpabilité des chrétiens, Tacite propose une théorie du bouc émissaire lui

permettant de faire ressortir la cruauté et l’arbitraire de l’empereur et non

par sympathie pour les chrétiens qui sont amalgamés aux juifs, porteurs à ses

yeux d’une même « haine du genre humain ».

Suétone mentionne

également une persécution au milieu d’une liste de mesures prises par Néron mais

sans la lier à l’incendie.

Les chrétiens sont

peut-être visés après avoir vu dans l’incendie le signe précurseur de

l’imminence de la fin du monde : se répandant dans les rues pour appeler à

la conversion, tombant ainsi sous le coup du crime de prosélytisme, ils

auraient ainsi attiré l’attention sur eux. Ils sont condamnés comme

incendiaires et subissent une peine réflexive : ils sont eux-mêmes, pour

certains, brûlés vifs dans les jardins impériaux ; d’autres sont utilisés

pour des jeux de rôle de type mythologiques ou des jeux de chasse, dont est

friand le public romain, dans les arènes du cirque du Vatican. Ils sont

condamnés en vertu de la lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis sans que leur

religion ne rentre pour autant en ligne de compte. Ainsi, la justification de

cette première persécution par un hypothétique institutum neronianum relève de

la légende.

Une tradition de la

communauté chrétienne de Rome lie dès la fin du Ier siècle à cet épisode la mort

des apôtres Pierre et Paul de Tarse, comme en atteste pour la première fois

Clément de Rome dans son épître aux Corinthiens, bien qu’on n’en connaisse rien

d’un point de vue historique. La communauté chrétienne de Rome sera prompte,

malgré le traumatisme subi, à dédouaner le pouvoir impérial de cette

persécution suivant l’injonction paulinienne de se soumettre « à toute

institution humaine » et Clément de Rome lui-même impute les victimes

néroniennes et la mort des deux apôtres à des tensions intra-communautaires.

Suivant cette tradition,

l’apôtre Pierre aurait été crucifié et son corps fut déposé dans une sépulture

au flanc de la colline du Vatican soit en 64, soit en 67. L’apôtre Paul de

Tarse, suivant une tradition remontant au IIIe siècle, aurait lui été décapité

aux Aquae Salvae, sur la route d’Ostie, en 65 ou 67, à l’emplacement de

l’actuelle basilique Saint-Paul-hors-les-Murs.

SOURCE : https://www.paroissedelimogne.fr/PREMIERS-MARTYRS-DE-L-EGLISE-DE-ROME.html

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Jules Eugène Lenepveu, I

martiri nelle catacombe, 1855, Parigi, Museo d'Orsay

24 June on

some calendars

Profile

Christians who

were blamed by

the Roman Emperor Nero with

setting fire to Rome, Italy,

and were sentenced to death as

punishment. They were all disciples of the Apostles. The total number of these

murders is known only to God.

martyred in 64 in

a variety of ways, the gorier the better from Nero‘s

point of view; some were covered with the skins of animals and

thrown to wild dogs to

be torn apart; others were crucified and at sunset were covered in oil and used

as human torches

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

nettsteder

i norsk

Readings

O God, who consecrated

that abundant first fruits of the Roman Church by the blood of the Martyrs,

grant, we pray, that with firm courage we may together draw strength from so

great a struggle and ever rejoice at the triumph of faithful love. Through our

Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the

Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. – collect for the liturgy of the

First Martyrs of Rome

MLA

Citation

“First Martyrs of

Rome“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 April 2024. Web. 9 June 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/first-martyrs-of-rome/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/first-martyrs-of-rome/

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902), Martyre

romaine, / Christian Dirce, 1897, 263 x 530, National Museum in Warsaw

Book of

Saints – Martyrs of Rome – 24 June

Article

(Saints)

(June

24) (1st

century) These, many hundreds in number, are the Christians put

to death by the Emperor Nero (A.D. 64) on the absurd charge that it was they

who had caused the great Fire of Rome, probably his own work. The strange and

horrible deaths they suffered are well known. Some, sewn up in the skins of

animals, were thrown to the wild beasts in the Amphitheatre; others, besmeared

with oil, were used as torches to illuminate the Imperial Gardens; others were

crucified, etc, etc.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Martyrs of Rome”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

28 November 2014. Web. 9 June 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-martyrs-of-rome-24-june/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-martyrs-of-rome-24-june/

First Martyrs of the See

of Rome

Feastday: June 30

Death: 64

The holy men and women

are also called the “Protomartyrs of Rome.” They were accused of burning Rome by Nero ,

who burned Rome to

cover his own crimes. Some martyrs were burned as living torches at evening

banquets, some crucified, others were fed to wild animals. These martyrs died

before Sts. Peter and Paul, and are called “disciples of the Apostles. . . whom

the Holy Roman church sent to their Lord before

the Apostles’ death.”

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=3385

First Martyrs of Rome

Feastday: June 30

Many martyrs who suffered

death under Emperor Nero .

Owing to their executions during the reign of Emperor Nero, they are called the

Neronian Martyrs, and they are also termed the Protomartyrs of Rome, being

honored by the site in Vatican City called the Piazza of the Protomartyrs.

These early Christians were disciples of the Apostles, and they endured hideous

tortures and ghastly deaths following the burning of Rome in

the infamous fire of 62.Their dignity in suffering, and their fervor to the

end, did not provide Nero or

the Romans with

the public diversion desired. Instead, the faith was

firmly planted in the Eternal City.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=4937

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Karl

Theodor von Piloty, Nero Walks on Rome’s Cinders, circa 1861,

446 x 582, Szépművészeti Múzeum, Museum of Fine Arts and the Hungarian National

Gallery

Saints

of the Day – Roman Martyrs under Nero

Article

Died 64. On a summer’s

day, July 19, in the reign of the Emperor Nero, the city of Rome caught fire.

For six days the fire raged, from the foot of the Palatine Hill to the outer

suburbs, and only by the demolition of property to create a gap in the path of

the flames were four districts of the city preserved.

The mystery of the fire’s

origin was never solved, but it was thought to be due to incendiarism. There

was an ugly rumor that Nero himself had set fire to his own capital, and that

slaves of the imperial household had been seen spreading the flames. Nero was

at Antium when it occurred, and for three days, despite urgent messages, made

no move and issued no instructions; only after this delay did he return to the

capital, and from the Tower of Macaenas he surveyed the blazing city.

With a lyre in his hand and

in a theatrical pose, he declaimed Homer’s account of the destruction of Troy,

and it was this incident which gave rise to the legend that Nero fiddled while

Rome burned. Though it is unlikely that he caused the calamity, the suspicion

was strengthened by his annexation, after the fire, of a considerable part of

the desolated area for the erection of his ‘Golden House,’ a palace of immense

size, with triple colonnades a mile long, where, he declared, ‘now at last he

was housed like a human being.’

But the growth of the

rumor spread by the outraged population who were homeless and without food, and

also the fear of revolution, obliged him to take counter measures. The imperial

gardens were thrown open as a refuge to the destitute, temporary buildings were

improvised, welfare and food services were organized; and, to divert attention

from himself, he turned upon the Christians and openly declared that they were

responsible.

Then began the most

ruthless persecution. He ranged against them not only him own bitter hostility

but also the rage and hatred of the populace. Tacitus records the grim story:

“They died in torments and their torments were embittered by insult and

derision. Some were nailed on crosses, others sewn up in the skins of wild

beasts and exposed to the fury of dogs, others again, smeared over with

combustible materials, were used as torches to illuminate the darkness of

night.” Rarely has the world known such a spectacle of horror as when the

gardens of Nero blazed with this fiendish carnival.

How many suffered is

beyond compute. We only know that through the deserted streets and among the

smoldering ruins the Christians were hunted like rats and, when caught, became

the victims of Nero’s insensate fury. They were nights of horror and days when

no man could trust his neighbor. Whole families were rounded up and sent to

death. In the pages of the martyrs there is an honored place for these unknown

victims who suffered for the faith and in the patience of Christ, and left

behind them an imperishable memory (Gill).

MLA

Citation

Katherine I

Rabenstein. Saints of the Day, 1998. CatholicSaints.Info.

29 June 2020. Web. 30 June 2020. <https://catholicsaints.info/saints-of-the-day-roman-martyrs-under-nero/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saints-of-the-day-roman-martyrs-under-nero/

Solemnities & Holy

Days: First Holy Martyrs of the Holy Roman Church

Feast Day: June 30

Patronage: All

Christians

These early Christians

were the first persecuted in mass by the Emperor Nero in the year 64 A.D.,

before the martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul. Nero was widely believed to have

caused the fire that burned down much of Rome in that same year. He blamed

the fire on Christians and put them to death, many by crucifixion, being fed to

the wild animals in the circus, or by being tied to posts and lit up as human

torches.

These Holy martyrs were

called the “Disciples of the Apostles” and their firmness in the face of their

gruesome deaths were a powerful testimony that led to many conversions in the

early Roman Church. These were all early Christians in Rome within a

dozen or so years after the death of Jesus, though they were not the converts

of the “Apostle of the Gentiles” Romans 15:20. Paul had not yet visited

them at the time he wrote his great letter in 57-58 A.D.

There was a large Jewish

population in Rome. Probably as a result of Controversy between Jews and

Jewish Christians, the Emperor expelled all Jews from Rome in 49-50 A.D.

Historians tell us that the expulsion was due to disturbances in the city,

“Caused by certain Christians”. It is believed that many came back after

the Emperor’s death in 54 A.D., because Paul’s letter was addressed to a Church

with members from Jewish and Gentile backgrounds.

In July of 64 A.D., more

than half of Rome was destroyed by fire. Rumor blamed the tragedy on

Nero, who wanted to enlarge his palace. He shifted the blame by accusing

the Christians. According to the Historian Tacitus, many Christians were

put to death because of their “hatred of the human race”. Peter and Paul

were probably among the victims of this time. Eventually Nero was

threatened by an army revolt and condemned to death by the senate, and committed

suicide in 68 A.D. at the age of 30 because of these, the first of Christian

martyrs being falsely blamed.

Wherever the Good News of

Jesus was preached, it met the same opposition as Jesus did, and many of those

who began to follow him shared his sufferings and death. Notice how no

human force could stop the Spirit unleashed upon the world through the

Christians? They only became stronger witnesses to the faith. Pope

Clement I, third successor of St. Peter writes, “It was through envy and

jealousy that the greatest and most upright pillars of the church were

persecuted and struggled unto death… First of all, Peter whom because of

unreasonable jealousy suffered not merely once or twice, but many times, and,

having thus given his witness, went to the place of glory that he

deserved. It was through jealousy and conflict that Paul showed the way

to the prize for perseverance. He was put in chains seven times, sent

into exile, and stoned; a herald both in the east and the west, he achieved a

noble fame by his faith.” We too, can follow the examples of the Great Saints

that went before us, paving the way of our faith that has stood the many

centuries of time. Don’t forget to call upon the First Holy Martyrs of

the Holy Roman Church on this their Feast Day – as they are always willing to

help us, if only we call upon them for assistance.

SOURCE : https://connection.newmanministry.com/saint/first-holy-martyrs-of-the-holy-roman-church/

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Santi Protomartiri Romani (Rome ; Santi Protomartiri Romani (Rome)

Santi Primi martiri

della santa Chiesa di Roma

Santi Protomartiri Romani (Rome ; Santi Protomartiri Romani (Rome)

Butler’s

Lives of the Saints – Martyrs of Rome under Nero

Article

Tertullian observes, that

it was the honour of the Christian religion that Nero, the most avowed enemy to

all virtue, was the first Roman emperor who declared against it a most bloody

war. The sanctity and purity of the manners of the primitive Christians was a

sufficient motive to stir up the rage of that monster; and he took the

following occasion to draw his sword against them. The city of Rome had been

set on fire, and had burned nine days, from the 19th to the 28th of July, in

the year 64; in which terrible conflagration, out of the fourteen regions or

quarters into which it was then divided, three were entirely laid in ashes,

seven of them were miserably defaced and filled with the ruins of half-burnt

buildings, and only four entirely escaped this disaster. During this horrible

tragedy, Nero came from Antium to Rome, and seated himself on the top of a

tower upon a neighbouring hill, in the theatrical dress of a musician, singing

a poem which himself had composed on the burning of Troy. The people accused

him of being the author of this calamity, and said he caused fire to be set to

the city that he might glut his eyes with an image of the burning of Troy.

Tillemont, Crevier, and other judicious critics make no doubt but he was the

author of this calamity. Suetonius and Dion Cassius positively charge him with

it. Tacitus indeed doubts whether the fire was owing to accident or to the

wickedness of the prince; but by a circumstance which he mentions, it appears

that the flame was at least kept up and spread for several days by the tyrant’s

orders; for several men hindered all that attempted to extinguish the fire, and

increased it by throwing lighted torches among the houses, saying they were

ordered so to do. In which, had they been private villains, they would not have

been supported and backed, but brought to justice. Besides, when the fire had

raged seven days, and destroyed every thing from the great circus, at the foot

of mount Palatine, to the further end of the Esquiliæ, and had ceased for want

of fuel, the buildings being in that place thrown down, it broke out again in

Tigellinus’s gardens, which place increased suspicion, and continued burning

two days more. Besides envying the fate of Priam, who saw his country laid in

ashes, Nero had an extravagant passion to make a new Rome, which should be

built in a more sumptuous manner, and extended as far as Ostia to the sea; he

wanted room in particular to enlarge his own palace; accordingly, he

immediately rebuilt his palace of an immense extent, and adorned all over with

gold, mother-of-pearl, precious stones, and whatever the world afforded that

was rich and curious, so that he called it the Golden Palace. But this was

pulled down after his death. The tyrant seeing himself detested by all mankind

as the author of this calamity, to turn off the odium and infamy of such an

action from himself, and at the same time to gratify his hatred of virtue and

thirst after blood, he charged the Christians with having set the city on fire.

Tacitus testifies, that nobody believed them guilty; yet the idolaters, out of

extreme aversion to their religion, rejoiced in their punishment.

The Christians therefore

were seized, treated as victims of the hatred of all mankind, insulted even in

their torments and death, and made to serve for spectacles of diversion and

scorn to the people. Some were clothed in the skins of wild beasts, and exposed

to dogs to be torn to pieces: others were hung on crosses set in rows, and many

perished by flames, being burnt in the night-time that their execution might

serve for fires and light, says Tacitus. This is further illustrated by Seneca,

Juvenal, and his commentator, who say that Nero punished the magicians, (by

which impious name they meant the Christians,) causing them to be besmeared over

with wax, pitch, and other combustible matter, with a sharp spike put under

their chin to make them hold it upright in their torments, and thus to be burnt

alive. Tacitus adds, that Nero gave his own gardens to serve for a theatre to

this spectacle. The Roman Martyrology makes a general mention of all these

martyrs on the 24th of June, styling them the disciples of the apostles, and

the first fruits of the innumerable martyrs with which Rome, so fruitful in

that divine seed, peopled heaven. These suffered in the year 64, before the

apostles SS. Peter and Paul, who had pointed out the way to them by their holy

instructions. After this commencement of the persecution, laws were made, and

edicts published throughout the Roman empire, which forbade the profession of

the faith under the most cruel torments and death, as is mentioned by Sulpicius

Severus, Orosius, and others. No sooner had the imperial laws commanded that

there should be no Christians, but the senate, the magistrates, the people of

Rome, all the orders of the empire, and every city rose up against them, says

Origen. Yet the people of God increased the more in number and strength the

more they were oppressed, as the Jews in Egypt had done under Pharoah.

MLA

Citation

Father Alban Butler.

“Martyrs of Rome, under Nero”. Lives of the

Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info.

25 June 2013. Web. 30 June 2020. <https://catholicsaints.info/butlers-lives-of-the-saints-martyrs-of-rome-under-nero/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/butlers-lives-of-the-saints-martyrs-of-rome-under-nero/

Martyr

The Greek word martus signifies

a witness who testifies to a fact of which he has knowledge from

personal observation. It is in this sense that the term first appears in Christian literature;

the Apostles were "witnesses" of all that they had observed in the

public life of Christ,

as well as of all they had learned from His teaching, "in Jerusalem,

and in all Judea,

and Samaria, and even to the uttermost part of the earth" (Acts

1:8). St. Peter, in his address to the Apostles and disciples relative to

the election of a successor to Judas,

employs the term with this meaning: "Wherefore, of these men who have

accompanied with us all the time that the Lord

Jesus came in and went out among us, beginning from the baptism of

John until the day he was taken up from us, one of these must be made witness with

us of his resurrection"

(Acts

1:22). In his first public discourse the chief of the Apostles speaks of

himself and his companions as "witnesses" who saw the risen Christ

and subsequently, after the miraculous escape

of the Apostles from prison,

when brought a second time before the tribunal, Peter again alludes to the

twelve as witnesses to Christ,

as the Prince and Saviour of Israel,

Who rose from the dead; and added that in giving their public testimony to the

facts, of which they were certain, they must obey God rather

than man (Acts

5:29 sqq.). In his First Epistle St. Peter also refers to himself as a

"witness of the sufferings

of Christ" (1

Peter 5:1).

But even in these first

examples of the use of the word martus in Christian terminology

a new shade of meaning is already noticeable, in addition to the accepted

signification of the term. The disciples of Christ were no ordinary witnesses

such as those who gave testimony in a court of justice.

These latter ran no risk in bearing testimony to facts that came under their

observation, whereas the witnesses of Christ were brought face to face daily,

from the beginning of their apostolate, with the possibility of incurring

severe punishment and even death itself. Thus, St. Stephen was a witness who

early in the history of Christianity sealed

his testimony with his blood. The careers of the Apostles were at all times

beset with dangers of the gravest character, until eventually they all suffered

the last penalty for their convictions. Thus, within the lifetime of the

Apostles, the term martus came to be used in the sense of a witness

who at any time might be called upon to deny what he testified to, under

penalty of death. From this stage the transition was easy to the ordinary

meaning of the term, as used ever since in Christian literature:

a martyr, or witness of Christ,

is a person who,

though he has never seen nor heard the Divine Founder of the Church,

is yet so firmly convinced of the truths of

the Christian

religion, that he gladly suffers death rather than deny it. St. John, at

the end of the first century, employs the word with this meaning; Antipas, a

convert from paganism,

is spoken of as a "faithful witness (martus) who was slain among you,

where Satan dwelleth"

(Revelation

2:13). Further on the same Apostle speaks of the "souls of them that

were slain for the Word of God and

for the testimony (martyrian) which they held" (Revelation

6:9).

Yet, it was only by

degrees, in the course of the first age of the Church,

that the term martyr came to be exclusively applied to those who had died for

the faith.

The grandsons of St.

Jude, for example, on their escape from the peril they underwent when cited

before Domitian were

afterwards regarded as martyrs (Eusebius,

"Hist. eccl", III, xx, xxxii). The famous confessors of Lyons,

who endured so bravely awful

tortures for their belief,

were looked upon by their fellow-Christians as martyrs, but they themselves

declined this title as of right belonging only to those who had actually died:

"They are already martyrs whom Christ has deemed worthy to be taken up in

their confession, having sealed their testimony by their departure; but we are

confessors mean and lowly" (Eusebius,

op. cit., V, ii). This distinction between martyrs and confessors is thus

traceable to the latter part of the second century: those only were martyrs who

had suffered the extreme penalty, whereas the title of confessors was given

to Christians who

had shown their willingness to die for their belief,

by bravely enduring imprisonment or

torture, but were not put

to death. Yet the term martyr was still sometimes applied during the third

century to persons still

living, as, for instance, by St.

Cyprian, who gave the title of martyrs to a number of bishops, priests,

and laymen condemned

to penal servitude in the mines (Ep. 76). Tertullian speaks

of those arrested as Christians and

not yet condemned as martyres designati. In the fourth century, St.

Gregory of Nazianzus alludes to St.

Basil as "a martyr", but evidently employs the term in the

broad sense in which the word is still sometimes applied to a person who

has borne many and grave hardships in the cause of Christianity.

The description of a martyr given by the pagan historian

Ammianus Marcellinus (XXII, xvii), shows that by the middle of the fourth

century the title was everywhere reserved to those who had actually suffered

death for their faith.

Heretics and schismatics put

to death as Christians were

denied the title of martyrs (St.

Cyprian, Treatise

on Unity 14; St.

Augustine, Ep. 173; Euseb., Church

History V.16, V.21). St.

Cyprian lays down clearly the general principle that "he cannot

be a martyr who is not in the Church;

he cannot attain unto the kingdom who forsakes that which shall reign

there." St.

Clement of Alexandria strongly disapproves (Stromata IV.4)

of some heretics who

gave themselves up to the law;

they "banish themselves without being martyrs".

The orthodox were

not permitted to seek martyrdom. Tertullian,

however, approves the conduct of the Christians of

a province of Asia who

gave themselves up to the governor, Arrius Antoninus (Ad. Scap., v). Eusebius also

relates with approval the incident of three Christians of

Cæsarea in Palestine who, in the persecution of Valerian,

presented themselves to the judge and were condemned to death (Church

History VII.12). But while circumstances might sometimes excuse such a

course, it was generally held to be imprudent. St.

Gregory of Nazianzus sums up in a sentence the rule to be followed in

such cases: it is mere rashness to seek death, but it is cowardly to refuse it

(Orat. xlii, 5, 6). The example of a Christian of Smyrna named

Quintus, who, in the time of St.

Polycarp, persuaded several of his fellow believers to declare

themselves Christians,

was a warning of what might happen to the over-zealous: Quintus at the last

moment apostatized,

though his companions persevered. Breaking idols was condemned by the Council

of Elvira (306), which, in its sixtieth canon, decreed that a Christian put

to death for such vandalism would not be enrolled as a martyr.

Lactantius, on the other hand, has only mild censure for a Christian of Nicomedia who

suffered martyrdom for tearing down the edict of persecution (Do

mort. pers., xiii). In one case St.

Cyprian authorizes seeking martyrdom. Writing to his priests and deacons regarding

repentant lapsi who

were clamouring to be received back into communion, the bishop after

giving general directions on the subject, concludes by saying that if these

impatient personages are so eager to get back to the Church there

is a way of doing so open to them. "The struggle is still going

forward", he says, "and the strife is waged daily. If they (the lapsi)

truly and with constancy repent of what they have done, and the fervour of

their faith prevails,

he who cannot be delayed may be crowned"

(Ep. xiii).

Legal basis of the

persecutions

Acceptance of the

national religion in antiquity was an obligation incumbent

on all citizens; failure to worship the gods of the State was equivalent to

treason. This universally accepted principle is responsible for the various

persecutions suffered by Christians before

the reign of Constantine; Christians denied

the existence of and therefore refused to worship the gods of the state

pantheon. They were in consequence regarded as atheists.

It is true,

indeed, that the Jews also

rejected the gods of Rome,

and yet escaped persecution.

But the Jews,

from the Roman standpoint, had a national religion and a national God, Jehovah,

whom they had a full legal right to worship. Even after the destruction

of Jerusalem,

when the Jews ceased

to exist as a nation, Vespasian made

no change in their religious status, save that the tribute formerly sent

by Jews to

the temple at Jerusalem was

henceforth to be paid to the Roman exchequer. For some time after its

establishment, the Christian

Church enjoyed the religious privileges of the Jewish nation, but from

the nature of the case it is apparent that the chiefs of the Jewish

religion would not long permit without protest this state of things.

For they abhorred Christ's

religion as much as they abhorred its Founder. At what date the Roman

authorities had their attention directed to the difference between the Jewish

and the Christian religion

cannot be determined, but it appears to be fairly well established that laws proscribing Christianity were

enacted before the end of the first century. Tertullian is

authority for the statement that persecution of

the Christians was institutum

Neronianum — an institution of Nero —

(Ad nat., i, 7). The First Epistle of St. Peter also clearly alludes to the

proscription of Christians,

as Christians,

at the time it was written (I, St. Peter, iv, 16). Domitian (81-96)

also, is known to have punished

with death Christian members

of his own family on

the charge of atheism (Suetonius,

"Domitianus", xv). While it is therefore probable that the formula:

"Let there be no Christians"

(Christiani non sint) dates from the second half of the first century, yet the

earliest clear enactment on the subject of Christianity is

that of Trajan (98-117)

in his famous letter to the younger Pliny, his legate in

Bithynia.

Pliny had been sent

from Rome by

the emperor to restore order in the Province of Bithynia-Pontus. Among the

difficulties he encountered in the execution of his commission one of the most

serious concerned the Christians.

The extraordinarily large number of Christians he

found within his jurisdiction greatly

surprised him: the contagion of their "Superstition", he reported

to Trajan,

affected not only the cities but even the villages and country districts of the

province (Pliny, Ep., x, 96). One consequence of the general defection from the

state religion was of an economic order:

so many people had become Christians that

purchasers were no longer found for the victims that once in great numbers were

offered to the gods. Complaints were laid before the legate relative

to this state of affairs, with the result that some Christians were

arrested and brought before Pliny for examination. The suspects were

interrogated as to their tenets and those of them who persisted in declining

repeated invitations to recant were executed. Some of the prisoners,

however, after first affirming that they were Christians,

afterwards, when threatened with punishment, qualified their first admission by

saying that at one time they had been adherents of the proscribed body but were

so no longer. Others again denied that they were or ever had been Christians.

Having never before had to deal with questions concerning Christians Pliny

applied to the emperor for instructions on three points regarding which he did

not see his way clearly: first, whether the age of the accused should be taken

into consideration in meting out punishment; secondly, whether Christians who

renounced their belief should

be pardoned; and thirdly, whether the mere profession of Christianity should

be regarded as a crime, and punishable as such, independent of the fact of the

innocence or guilt of the accused of the crimes ordinarily associated with such

profession.

To these inquiries Trajan replied

in a rescript which

was destined to have the force of law throughout the second century in relation

to Christianity.

After approving what his representative had already done, the emperor directed

that in future the rule to be observed in dealing with Christians should

be the following: no steps were to be taken by magistrates to ascertain who

were or who were not Christians,

but at the same time, if any person was

denounced, and admitted that he was a Christian,

he was to be punished — evidently with death. Anonymous denunciations were not

to be acted upon, and on the other hand, those who repented of being Christians and

offered sacrifice to the gods, were to be pardoned. Thus, from the year 112,

the date of

this document, perhaps even from the reign of Nero,

a Christian was

ipso facto an outlaw. That the followers of Christ were known to the highest

authorities of the State to be innocent of the numerous crimes and misdemeanors

attributed to them by popular calumny,

is evident from Pliny's testimony to this effect, as well as from Trajan's order: conquirendi

non sunt. And that the emperor did not regard Christians as

a menace to the State is apparent from the general tenor of his instructions.

Their only crime was that they were Christians,

adherents of an illegal religion. Under this regime of proscription the Church existed

from the year 112 to the reign of Septimius

Severus (193-211). The position of the faithful was always one of

grave danger, being as they were at the mercy of every malicious person who

might, without a moment's warning, cite them before the nearest tribunal. It

is true indeed,

that the delator was an unpopular person in

the Roman Empire, and, besides, in accusing a Christian he

ran the risk of incurring severe punishment if unable to make good his charge

against his intended victim. In spite of the danger, however, instances are

known, in the persecution era,

of Christian victims

of delation.

The prescriptions

of Trajan on

the subject of Christianity were

modified by Septimius

Severus by the addition of a clause forbidding any person to

become a Christian.

The existing law of Trajan against Christians in

general was not, indeed, repealed by Severus, though for the moment it was

evidently the intention of the emperor that it should remain a dead letter. The

object aimed at by the new enactment was, not to disturb those already Christians,

but to check the growth of the Church by

preventing conversions. Some illustrious convert martyrs, the most famous being

Sts. Perpetua and Felicitas, were added to the roll of champions of religious

freedom by this prohibition, but it effected nothing of consequence in regard

to its primary purpose. The persecution came

to an end in the second year of the reign of Caracalla (211-17).

From this date to the reign of Decius (250-53)

the Christians enjoyed

comparative peace with the exception of the short period when Maximinus the

Thracian (235-38) occupied the throne. The elevation of Decius to

the purple began a new era in the relations between Christianity and

the Roman State. This emperor, though a native of Illyria,

was nevertheless profoundly imbued with the spirit of Roman conservatism. He

ascended the throne with the firm intention of restoring the prestige which the

empire was fast losing, and he seems to have been convinced that the chief

difficulty in the way of effecting his purpose was the existence of Christianity.

The consequence was that in the year 250 he issued an edict, the tenor of which

is known only from the documents relating to its enforcement, prescribing that

all Christians of

the empire should on a certain day offer sacrifice to the gods.

This new law was quite a

different matter from the existing legislation against Christianity.

Proscribed though they were legally, Christians had

hitherto enjoyed comparative security under a regime which clearly laid down

the principle that they were not to be sought after officially by the civil

authorities. The edict of Decius was

exactly the opposite of this: the magistrates were now constituted religious

inquisitors, whose duty it

was to punish Christians who

refused to apostatize.

The emperor's aim, in a word, was to annihilate Christianity by

compelling every Christian in

the empire to renounce his faith.

The first effect of the new legislation seemed favourable to the wishes of its

author. During the long interval of peace since the reign of Septimius

Severus — nearly forty years — a considerable amount of laxity had

crept into the Church's discipline,

one consequence of which was, that on the publication of the edict of persecution,

multitudes of Christians besieged

the magistrates everywhere in their eagerness to comply with its demands. Many

other nominal Christians procured

by bribery certificates stating that they had complied with the law,

while still others apostatized under

torture. Yet after this first throng of weaklings had put themselves outside

the pale of Christianity there

still remained, in every part of the empire, numerous Christians worthy

of their religion, who endured all manner of torture, and death itself, for

their convictions. The persecution lasted

about eighteen months, and wrought incalculable harm.

Before the Church had

time to repair the damage thus caused, a new conflict with the State was

inaugurated by an edict of Valerian published

in 257. This enactment was directed against the clergy — bishops, priests,

and deacons —

who were directed under pain of exile to offer sacrifice. Christians were

also forbidden, under pain of death, to resort to their cemeteries. The results

of this first edict were of so little moment that the following year, 258, a

new edict appeared requiring the clergy to

offer sacrifice under penalty of death. Christian senators, knights,

and even the ladies of their families,

were also affected by an order to offer sacrifice under penalty of confiscation

of their goods and reduction to plebeian rank. And in the event of these severe

measures proving ineffective the law prescribed

further punishment: execution for the men, for the women exile. Christian slaves

and freedmen of the emperor's household also were punished by confiscation of

their possessions and reduction to the lowest ranks of slavery. Among the

martyrs of this persecution were Pope

Sixtus II and St.

Cyprian of Carthage. Of its further effects little is known, for want of

documents, but it seems safe to surmise that, besides adding many new martyrs

to the Church's roll,

it must have caused enormous suffering to the Christian nobility.

The persecution came

to an end with the capture (260) of Valerian by

the Persians;

his successor, Gallienus (260-68),

revoked the edict and restored to the bishops the

cemeteries and meeting places.

From this date to the

last persecution inaugurated

by Diocletian (284-305)

the Church,

save for a short period in the reign of Aurelian (270-75),

remained in the same legal situation as in the second century. The first edict

of Diocletian was promulgated at Nicomedia in

the year 303, and was of the following tenor: Christian assemblies

were forbidden; churches and sacred books were ordered to be destroyed, and

all Christians were

commanded to abjure their

religion forthwith. The penalties for failure to comply with these demands were

degradation and civil death for the higher classes, reduction to slavery for

freemen of the humbler sort, and for slaves incapacity to receive the gift of

freedom. Later in the same year a new edict ordered the imprisonment of ecclesiastics of

all grades, from bishops to exorcists.

A third edict imposed the death-penalty for refusal to abjure,

and granted freedom to those who would offer sacrifice; while a fourth

enactment, published in 304, commanded everybody without exception to offer

sacrifice publicly. This was the last and most determined effort of the Roman

State to destroy Christianity.

It gave to the Church countless

martyrs, and ended in her triumph in the reign of Constantine.

Number of the martyrs

Of the 249 years from the

first persecution under Nero (64)

to the year 313, when Constantine established lasting peace, it is calculated

that the Christians suffered persecution about

129 years and enjoyed a certain degree of toleration about 120 years. Yet it

must be borne in mind that even in the years of comparative tranquillity Christians were

at all times at the mercy of every person ill-disposed

towards them or their religion in the empire. Whether or not delation of Christians occurred

frequently during the era of persecution is

not known, but taking into consideration the irrational hatred of

the pagan population

for Christians,

it may safely be surmised that not a few Christians suffered

martyrdom through betrayal. An example of the kind related by St.

Justin Martyr shows how swift and terrible were the consequences of

delation. A woman who

had been converted to Christianity was

accused by her husband before a magistrate of being a Christian.

Through influence the accused was granted the favour of a brief respite to

settle her worldly affairs, after which she was to appear in court and put

forward her defence. Meanwhile her angry husband caused the arrest of the

catechist, Ptolomæus by name, who had instructed the convert. Ptolomæus, when

questioned, acknowledged that he was a Christian and

was condemned to death.

In the court, at the time this sentence was pronounced, were two persons who

protested against the iniquity of inflicting capital punishment for the mere

fact of professing Christianity.

The magistrate in reply asked if they also were Christians,

and on their answering in the affirmative both were ordered to be executed. As

the same fate awaited the wife of the delator also, unless she recanted, we

have here an example of three, possibly four, persons suffering

capital punishment on the accusation of a man actuated by malice, solely for

the reason that his wife had given up the evil life

she had previously led in his society (St.

Justin Martyr, II, Apol., ii).

As to the actual number

of persons who

died as martyrs during these two centuries and a half we have no definite

information. Tacitus is authority for the statement that an immense multitude (ingens

multitudo) were put

to death by Nero.

The Apocalypse of St. John speaks of "the souls of

them that were slain for the word of God"

in the reign of Domitian,

and Dion Cassius informs us that "many" of the Christian nobility

suffered death for their faith during

the persecution for

which this emperor is responsible. Origen indeed,

writing about the year 249, before the edict of Decius,

states that the number of those put

to death for the Christian

religion was not very great, but he probably means that the number of

martyrs up to this time was small when compared with the entire number of Christians (cf.

Allard, "Ten Lectures on the Martyrs", 128). St.

Justin Martyr, who owed his conversion largely

to the heroic example of Christians suffering

for their faith,

incidentally gives a glimpse of the danger of professing Christianity in

the middle of the second century, in the reign of so good an emperor as Antoninus

Pius (138-61). In his "Dialogue with Trypho" (cx), the apologist,

after alluding to the fortitude of

his brethren in religion, adds, "for it is plain that, though beheaded,

and crucified, and thrown to wild beasts, and chains, and fire, and all other

kinds of torture, we do not give up our confession; but, the more such things

happen, the more do others in larger numbers become faithful. . . . Every Christian has

been driven out not only from his own property,

but even from the whole world; for you permit no Christian to

live." Tertullian also,

writing towards the end of the second century, frequently alludes to the

terrible conditions under which Christians existed

("Ad martyres", "Apologia", "Ad Nationes", etc.):

death and torture were ever present possibilities.

But the new régime of

special edicts, which began in 250 with the edict of Decius,

was still more fatal to Christians.

The persecutions of Decius and Valerian were

not, indeed, of long duration, but while they lasted, and in spite of the large

number of those who fell away, there are clear indications that they produced

numerous martyrs. Dionysius

of Alexandria, for instance, in a letter to the Bishop of Antioch tells

of a violent persecution that

took place in the Egyptian capital,

through popular violence,

before the edict of Decius was

even published. The Bishop of

Alexandria gives several examples of what Christians endured

at the hands of the pagan rabble

and then adds that "many others, in cities and villages, were torn asunder

by the heathen"

(Eusebius, Church

History VI.41 sq.). Besides those who perished by actual violence,

also, a "multitude wandered in the deserts and

mountains, and perished of hunger and thirst, of cold and sickness and robbers

and wild beasts" (Eusebius,

l. c.). In another letter, speaking of the persecution under Valerian,

Dionysius states that "men and women,

young and old, maidens and matrons, soldiers and civilians, of every age and

race, some by scourging and fire, others by the sword, have conquered in the

strife and won their crowns" (Id., op. cit., VII, xi). At Cirta, in North

Africa, in the same persecution,

after the execution of Christians had

continued for several days, it was resolved to expedite matters. To this end

the rest of those condemned were brought to the bank of a river and made to

kneel in rows. When all was ready the executioner passed along the ranks and

despatched all without further loss of time (Ruinart, p. 231).

But the last persecution was

even more severe than any of the previous attempts to extirpate Christianity.

In Nicomedia "a great multitude" were put

to death with their bishop,

Anthimus; of these some perished by the sword, some by fire, while others were

drowned. In Egypt "thousands

of men, women and

children, despising the present life, . . . endured various deaths" (Eusebius, Church

History VII.4 sqq.), and the same happened in many other places

throughout the East. In the West the persecution came

to an end at an earlier date than in the East, but, while it lasted, numbers of

martyrs, especially at Rome,

were added to the calendar (cf. Allard, op. cit., 138 sq.). But besides those

who actually shed their blood in the first three centuries account must be

taken of the numerous confessors of the Faith who, in prison,

in exile, or in penal servitude suffered a daily martyrdom more difficult to

endure than death itself. Thus, while anything like a numerical estimate of the

number of martyrs is impossible, yet the meagre evidence on the subject that

exists clearly enough establishes the fact that countless men, women and

even children, in that glorious, though terrible, first age of Christianity,

cheerfully sacrificed their goods, their liberties, or their lives, rather than

renounce the faith they

prized above all.

Trial of the martyrs

The first act in the

tragedy of the martyrs was their arrest by an officer of the law.

In some instances the privilege of custodia libera, granted to St.

Paul during his first imprisonment,

was allowed before the accused were brought to trial; St.

Cyprian, for example, was detained in the house of the officer who arrested

him, and treated with consideration until the time set for his examination. But

such procedure was the exception to the rule; the accused Christians were

generally cast into the public prisons,

where often, for weeks or months at a time, they suffered the greatest

hardships. Glimpses of the sufferings they endured in prison are

in rare instances supplied by the Acts of the Martyrs. St. Perpetua, for

instance, was horrified by the awful darkness, the intense heat caused by

overcrowding in the climate of Roman Africa, and the brutality of the soldiers

(Passio SS. Perpet., et Felic., i). Other confessors allude to the various

miseries of prison life

as beyond their powers of description (Passio SS. Montani, Lucii, iv). Deprived

of food, save enough to keep them alive, of water, of light and air; weighted

down with irons, or placed in stocks with their legs drawn as far apart as was

possible without causing a rupture; exposed to all manner of infection from

heat, overcrowding, and the absence of anything like proper sanitary conditions

— these were some of the afflictions that preceded actual martyrdom. Many

naturally, died in prison under

such conditions, while others, unfortunately, unable to endure the strain,

adopted the easy means of escape left open to them, namely, complied with the

condition demanded by the State of offering sacrifice.

Those whose strength,

physical and moral, was capable of enduring to the end were, in addition,

frequently interrogated in court by the magistrates, who endeavoured by

persuasion or torture to induce them to recant. These tortures comprised every

means that human ingenuity in antiquity had devised to break down even the

most courageous;

the obstinate were scourged with whips, with straps, or with ropes; or again

they were stretched on the rack and their bodies torn apart with iron rakes.

Another awful punishment consisted in suspending the victim, sometimes for a

whole day at a time, by one hand; while modest women in

addition were exposed naked to the gaze of those in court. Almost worse than

all this was the penal servitude to which bishops, priests, deacons, laymen and women,

and even children, were condemned in some of the more violent persecutions;

these refined personages of both sexes, victims of merciless laws were

doomed to pass the remainder of their days in the darkness of the mines, where

they dragged out a wretched existence, half naked, hungry, and with no bed save

the damp ground. Those were far more fortunate who were condemned to even the

most disgraceful death, in the arena, or by crucifixion.

Honours paid the martyrs

It is easy to understand

why those who endured so much for their convictions should have been so

greatly venerated by

their co-religionists from even the first days of trial in the reign of Nero.

The Roman officials usually permitted relatives or friends to gather up the

mutilated remains of the martyrs for interment, although in some instances such

permission was refused. These relics the Christians regarded

as "more valuable than gold or precious stones" (Martyr. Polycarpi,

xviii). Some of the more famous martyrs received special honours, as for

instance, in Rome,

St. Peter and St.

Paul, whose "trophies", or tombs,

are spoken of at the beginning of the third century by the Roman priest Caius

(Eusebius, Church

History II.21.7). Numerous crypts and chapels in

the Roman

catacombs, some of which, like the capella grœca, were constructed in

sub-Apostolic times, also bear witness to the early veneration for those

champions of freedom of conscience who

won, by dying, the greatest victory in the history of the human

race. Special commemoration services of the martyrs, at which the holy

Sacrifice was offered over their tombs —

the origin of the time — honoured custom

of consecrating altars by enclosing in them the relics of

martyrs — were held on the anniversaries of their death; the famous Fractio

Panis fresco of the capella grœca, dating from the early second

century, is probably a representation (see s.v. FRACTIO

PANIS; SYMBOLS

OF EUCHARIST) in miniature, of such a celebration. From the age of

Constantine even still greater veneration was accorded the martyrs. Pope

Damasus (366-84) had a special love for

the martyrs, as we learn from the inscriptions, brought to light by de Rossi,

composed by him for their tombs in

the Roman