Sainte Hildegarde de

Bingen

Abbesse bénédictine, 35e docteur

de l'Église (+ 1179)

Elle était d'une noble

famille germanique. Très jeune, on la confie au couvent de Disibodenberg, un

monastère double, sur les bords du Rhin, où moines et moniales chantent la

louange divine en des bâtiments mitoyens. Devenue abbesse, elle s'en va fonder une

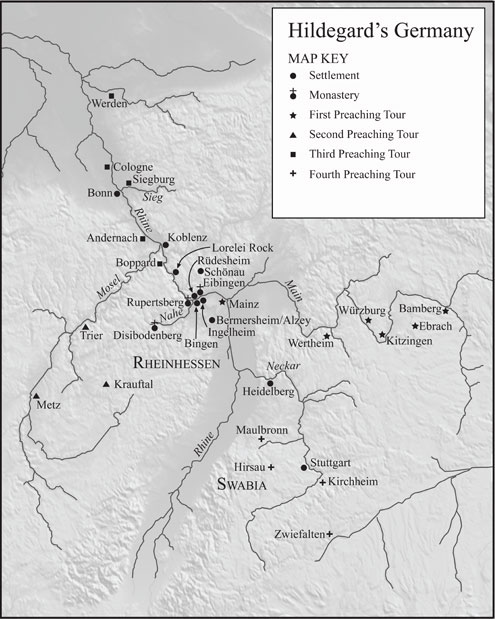

autre communauté à Bingen puis une à Eibingen. Elle voyage, va où on l'appelle,

prêche dans les cathédrales et les couvents, correspond avec toutes les têtes

couronnées, les pontifes de son temps, saint Bernard et

bien d'autres. Elle plaide pour une réforme radicale de l'Église. Depuis

sa petite enfance, elle est favorisée de visions exceptionnelles. Par

obéissance, elle les couchera sur le papier. Ses récits apocalyptiques (au sens

littéral de dévoilement des fins dernières) donnent de l'univers une vision

étonnante de modernité où la science actuelle peut se reconnaître (création

continue, énergie cachée dans la matière, magnétisme) mais qui peut aussi

apaiser la soif actuelle de nos contemporains tentés par le "Nouvel

Age". ("Le monde ne reste jamais dans un seul état",

écrit-elle.) L'essentiel de sa pensée réside dans le combat entre le Christ et

le prince de ce monde, au cœur d'un cosmos conçu comme une symphonie invisible.

Dante lui emprunta sa vision de la Trinité.

- Sainte Hildegarde de Bingen, le 2 février 2021, décret inscrivant la mémoire facultative de trois docteurs de l'Église: Grégoire de Narek, Jean d'Avila et Hildegarde de Bingen au Calendrier romain.

Dimanche 7 octobre 2012 - Messe pour l'ouverture du Synode des Évêques et proclamation comme "Docteur de l'Église" de saint Jean D'Avila et sainte Hildegarde de Bingen.

"Ces deux grands témoins de la foi vécurent à des époques et dans des contextes culturels très différents. Hildegarde, une bénédictine vivant en plein Moyen Age allemand, fut un vrai maître de théologie versée dans les sciences naturelles et la musique. Prêtre de la Renaissance espagnole, Jean prit part au renouveau culturel et religieux d'une Eglise et d'une société parvenues au seuil des temps modernes". Leur sainteté de vie et la profondeur de leur doctrine disent leur actualité. La grâce de l'Esprit les projeta dans une expérience de plus profonde compréhension de la Révélation, et leur permit de dialoguer intelligemment avec le monde dans lequel l'Eglise agissait". Puis le Pape a indiqué que ces deux figures de saints docteurs revêtent de l'importance à la veille de l'Année de la foi et en vue de la nouvelle évangélisation, à laquelle est consacrée la prochaine assise synodale. "Aujourd'hui encore, dans leurs enseignements, l'Esprit du Ressuscité résonne et éclaire le chemin vers la Vérité qui rend libre et donne son plein sens à nos vies". (source: VISnews)

Avant de présenter la figure de la sainte, le Pape a évoqué la Lettre apostolique de Jean-Paul II Mulieris Dignitatem, publiée en 1988 et qui traitait du "rôle précieux que les femmes ont accompli et accomplissent dans la vie de l'Eglise" et qui exprimait le remerciement de l'Eglise "pour toutes les manifestations du génie féminin au cours de l'histoire... Même au cours de ces siècles d'histoire que nous avons coutume d'appeler Moyen Age, certaines figures féminines se détachent par la sainteté de leur vie et la richesse de leur enseignement", comme Hildegarde de Bingen, issue d'une famille noble et nombreuse qui décida de la consacrer au service de Dieu. Après avoir reçu une bonne formation humaine et chrétienne de Jutta de Spanheim, Hildegarde entra au monastère bénédictin du Disibodenberg et reçut le voile des mains de l'évêque Othon de Bamberg. En 1136, elle fut élue supérieure et poursuivit son devoir "en faisant fructifier ses dons de femme cultivée, spirituellement élevée et capable de gérer avec compétence l'organisation de la vie de clôture", a ajouté le Pape.

Peu après, face aux nombreuses vocations, Hildegarde fonda un autre couvent à Bingen, dédié à saint Rupert, où elle passa le reste de sa vie. "Le style avec lequel elle exerçait son ministère d'autorité est exemplaire pour toute communauté religieuse: elle suscitait une émulation dans la pratique du bien". La sainte commença à décrire ses visions mystiques alors qu'elle était supérieure du Disibodengerg à son conseiller spirituel, le moine Volmar, et à son secrétaire, Richard. "Comme cela arrive toujours dans la vie des vrais mystiques, Hildegarde voulut aussi se soumettre à l'autorité de personnes sages pour discerner l'origine de ses visions craignant qu'elle ne fussent le fruit d'illusions et qu'elles ne proviennent pas de Dieu". Elle parla à ce sujet avec saint Bernard de Clairvaux qui la tranquillisa et l'encouragea. Puis, en 1147, elle reçut surtout l'approbation du Pape Eugène III qui, lors du synode de Trèves, lut un texte d'Hildegarde que lui avait présenté l'archevêque de Mayence. "Le Pape autorisa la mystique à écrire ses visions et à en parler en public. A compter de ce moment-là, le prestige spirituel de Hildegarde s'en trouva grandi, au point que ses contemporains lui attribuèrent le titre de prophétesse rhénane", a ajouté Benoît XVI.

"Voilà le signe d'une authentique expérience de l'Esprit-Saint, source de tout charisme: la personne dépositaire de dons surnaturels ne s'en vante jamais, ne les montre pas et surtout fait preuve d'une obéissance totale envers l'autorité ecclésiastique. Chaque don donné par l'Esprit-Saint est destiné, en fait, à l'édification de l'Eglise, et l'Eglise, par ses pasteurs, en reconnaît l'authenticité", a conclu le Saint-Père. (source: VIS 20100901 490)

Le 8 septembre 2010, Benoît XVI a poursuivi son évocation de sainte Hildegarde, bénédictine allemande du XII siècle, "qui se distingua par sa sainteté de vie et sa sagesse spirituelle". Rappelant les visions de cette mystique, il a en souligné la dimension théologique. Elles "se référaient aux principaux évènements de l'histoire du salut et utilisaient un langage largement poétique et symbolique. Dans son œuvre majeure sur la connaissance de la vie, Hildegarde de Bingen a résumé ce processus en trente cinq visions, de la création à la fin des temps... La partie centrale développe le thème du mariage mystique entre Dieu et l'humanité réalisé dans l'incarnation". Puis le Saint-Père a souligné combien ces brèves observations montrent que "la théologie peut recevoir des femmes un apport spécifique. Grâce à leur intelligence et à leur sensibilité, elles sont capables de parler de Dieu et des mystères de la foi. J'encourage donc -a-t-il dit- toutes celles qui assument ce service à l'accomplir dans un profond esprit ecclésial, en alimentant leur réflexion à la prière et en tenant compte de la grande richesse peu explorée de la mystique médiévale, cette mystique lumineuse que Hildegarde de Bingen représente" parfaitement.

Les autres écrits de sainte Hildegarde, comme le Livre des mérites de la vie ou le Livre des œuvres divines, a poursuivi le Pape, développent aussi "la relation profonde existant entre Dieu et l'homme. Le premier traité rappelle que la création, tout ce dont l'homme est l'accomplissement, reçoit la vie de la Trinité". Le second, "généralement considéré comme son œuvre majeure, décrit la création dans sa relation à Dieu et à la centralité de l'homme, et dénote un fort christocentrisme de sa connaissance biblique et patristique". Puis il a rappelé qu'Hildegarde s'intéressa aussi de médecine, de sciences naturelles et de musique. "Pour elle, la création entière est une symphonie de l'Esprit". Sa renommé en faisait l'objet de nombreux conseils. Des religieux, des évêques et des abbés s'adressaient à elle, et nombre de ses réponses demeurent valables. Forte de son autorité spirituelle, elle voyagea beaucoup à la fin de sa vie. Partout on l'écoutait "car on la considérait une messagère de Dieu. Elle rappelait clergé et communautés monastiques à une vie conforme à leur vocation. Elle combattit de manière énergique le catharisme allemand...en appelant de ses vœux une réforme radicale de l'Eglise, principalement pour corriger les abus du clergé auquel elle reprochait de vouloir renverser la nature même de l'Eglise. Elle disait aux clercs qu'un véritable renouveau de la communauté ecclésiale ne dépend moins du changement des structures que d'un sincère esprit de pénitence et de conversion. Ce message ne doit pas être oublié", a conclu le Pape. "Invoquons donc l'Esprit, afin qu'il suscite au sein de l'Eglise des femmes saintes et courageuses qui, en valorisant les dons reçus de Dieu, offrent une contribution particulière à la croissance spirituelle de nos communautés et de l'Église d'aujourd'hui". (source: VIS 20100908 500)

Au monastère de Rupertsberg, près de Bingen en Hesse rhénane, en 1179, sainte

Hildegarde, vierge moniale. Experte en sciences naturelles, en médecine et en

musique, elle composa plusieurs ouvrages où elle décrivit religieusement les

visions mystiques qu'il lui fut donné de contempler.

Martyrologe romain

Cette multitude des anges

a une raison d'être qui est liée à Dieu plus qu'à l'homme et elle n'apparaît

aux hommes que rarement. Certains anges, cependant, qui sont au service des

hommes, se révèlent par des signes, quand il plait à Dieu.

Sainte Hildegarde - Le

livre des œuvres divines

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1865/Sainte-Hildegarde-de-Bingen.html

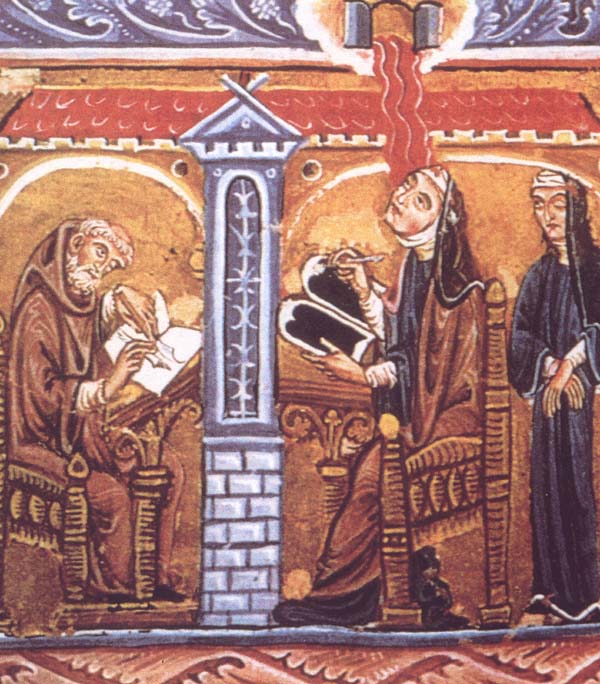

Hildegard

von Bingen empfängt eine göttliche Inspiration und gibt sie an ihren Schreiber

weiter. Miniatur aus dem Rupertsberger Codex des Liber Scivias

Hildegard

von Bingen receives a divine inspiration and passes it on to her scribe. Miniature

from the Rupertsberg Codex of Liber Scivias.

Illumination

from Hildegard's Scivias (1151) showing her receiving a vision and

dictating to teacher Volmar. Miniature, Rupertsberger

Codex des Liber Scivias.

Lumière pour son peuple

et pour son temps, sainte Hildegarde, dont le nom de famille est de Bingen,

brille encore davantage aujourd'hui puisqu'on célèbre le 800ème anniversaire

de celle qui, après avoir quitté la malice et l'impureté d'un monde sur lequel,

pressée par la charité du Christ, elle a répandu d'innombrables bienfaits,

mourut d'une sainte mort pour aller vivre dans l'éternité auprès de Dieu. Nous

participons d'un cœur joyeux au souvenir de cet anniversaire avec tous ceux qui

admirent et vénèrent cette femme qui nous donne un exemple rare; et nous vous

demandons, vénérable frère, d'être l'interprète et le messager de nos

sentiments puisque c'est sur le territoire de votre diocèse que cette femme a

vécu et qu'elle a été enlevée aux réalités terrestres.

Personne n'ignore que la

première gloire de cette fleur de la Germanie est la sainteté de sa vie : elle

avait été confiée, à l'âge de huit ans, à de saintes moniales qui firent son

éducation et, devenue adulte, elle s'engagea elle-même dans la vie religieuse,

voie qu'elle suivit avec amour et fidélité ; elle rassembla des compagnes ayant

le même projet de vie qu'elle-même et fonda un nouveau monastère d'où se

répandit avec bonheur "la bonne odeur du Christ" (cf. 2 Co 2,

15).

Comblée dès son jeune âge

par de remarquables dons surnaturels, sainte Hildegarde cultiva avec sagesse

les arcanes de la théologie, de la médecine, de la musique et d'autres arts ;

elle écrivit abondamment sur ces sujets et mit en lumière le rapport entre la

rédemption et la créature. Elle aima uniquement l'Eglise : dans l'ardeur de sa

charité, elle n'hésita pas à sortir de la clôture de son monastère et, pour

défendre la vérité et la paix, à rendre visite aux évêques et aux autorités

civiles et même à l'empereur ; elle n'hésita pas non plus à parler aux foules.

D'une santé faible mais

d'une très grande force spirituelle, cette "femme forte" était

appelée autrefois "la prophétesse de la Germanie"; aujourd'hui, en

cet anniversaire, il semble qu'elle s'adresse d'une façon pressante aux fidèles

de sa nation ainsi qu'à tous les autres. La vie même et l'action de cette

illustre sainte nous enseignent que la relation à Dieu et l'accomplissement de

sa volonté sont les biens qu'il faut rechercher avant tout, surtout pour ceux

qui ont choisi la voie étroite dans l'état religieux : à ceux-ci, il nous plaît

d'adresser les paroles de sainte Hildegarde : "Regardez et marchez dans le

droit chemin" (Epist. CXL ; PL 197, 371). Que ceux qui ont la foi

chrétienne se sentent poussés à traduire la bonne nouvelle de l'Evangile dans

la pratique de leur vie. Cette maîtresse, toute pénétrée de Dieu, nous montre

que l'on ne peut comprendre vraiment et gouverner le monde que si l'on est une

créature du Père des cieux qui est amour et providence. Enfin que la

sollicitude que cette infatigable servante du Sauveur a mise au service des

âmes et des corps de ses contemporains, conduise les hommes de bonne volonté

qui vivent aujourd'hui à venir en aide, dans la mesure de leurs forces, à leurs

frères et sœurs qui se trouvent dans le besoin.

En priant de tout cœur

pour que la solennité de cet anniversaire de sainte Hildegarde permette de

recueillir une ample moisson de fruits spirituels, à vous vénérable frère, aux

autres évêques, aux prêtres, aux fidèles qui se rassembleront pour célébrer

cette sainte, nous accordons bien volontiers notre bénédiction apostolique en

témoignage de notre amour.

Du Vatican, le 8

septembre 1979, première année de notre pontificat.

JEAN-PAUL II

© Copyright 1979 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastère pour la Communication

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Palais pontifical de Castel Gandolfo

Mercredi 1er septembre 2010

Sainte Hildegarde de

Bingen

Chers frères et sœurs,

En 1988, à l’occasion de

l’Année mariale, le vénérable Jean-Paul

II a écrit une Lettre apostolique intitulée Mulieris

dignitatem, traitant du rôle précieux que les femmes ont accompli et

accomplissent dans la vie de l’Eglise. «L'Eglise — y lit-on — rend grâce pour

toutes les manifestations du génie féminin apparues au cours de

l'histoire, dans tous les peuples et dans toutes les nations; elle rend grâce

pour tous les charismes dont l'Esprit Saint a doté les femmes dans l'histoire

du Peuple de Dieu, pour toutes les victoires remportées grâce à leur foi, à

leur espérance et à leur amour: elle rend grâce pour tous les fruits de la

sainteté féminine» (n. 31).

Egalement, au cours des

siècles de l’histoire que nous appelons habituellement Moyen Age, diverses

figures de femmes se distinguent par la sainteté de leur vie et la richesse de

leur enseignement. Aujourd’hui, je voudrais commencer à vous présenter l’une

d’entre elles: sainte Hildegarde de Bingen, qui a vécu en Allemagne au XIIe siècle.

Elle naquit en 1098 en Rhénanie, probablement à Bermersheim, près d’Alzey, et

mourut en 1179, à l’âge de 81 ans, en dépit de ses conditions de santé depuis

toujours fragiles. Hildegarde appartenait à une famille noble et nombreuse, et

dès sa naissance, elle fut vouée par ses parents au service à Dieu. A l’âge de huit

ans, elle fut offerte à l’état religieux (selon la Règle de saint Benoît, chap.

59) et, afin de recevoir une formation humaine et chrétienne appropriée, elle

fut confiée aux soins de la veuve consacrée Uda de Göllheim puis de Judith de

Spanheim, qui s’était retirée en clôture dans le monastère bénédictin

Saint-Disibod. C’est ainsi que se forma un petit monastère féminin de clôture,

qui suivait la Règle de saint Benoît. Hildegarde reçut le voile des mains de

l’évêque Othon de Bamberg et en 1136, à la mort de mère Judith, devenue magistra (Prieure)

de la communauté, ses concours l’appelèrent à lui succéder. Elle accomplit

cette charge en mettant à profit ses dons de femme cultivée, spirituellement

élevée et capable d’affronter avec compétence les aspects liés à l’organisation

de la vie de clôture. Quelques années plus tard, notamment en raison du nombre

croissant de jeunes femmes qui frappaient à la porte du monastère, Hildegarde

se sépara du monastère masculin dominant de Saint-Disibod avec la communauté à Bingen,

dédiée à saint Rupert, où elle passa le reste de sa vie. Le style avec lequel

elle exerçait le ministère de l’autorité est exemplaire pour toute communauté

religieuse: celui-ci suscitait une sainte émulation dans la pratique du bien,

au point que, comme il ressort des témoignages de l’époque, la mère et les

filles rivalisaient de zèle dans l’estime et le service réciproque.

Déjà au cours des années

où elle était magistra du monastère Saint-Disibod, Hildegarde avait

commencé à dicter ses visions mystiques, qu’elle avait depuis un certain temps,

à son conseiller spirituel, le moine Volmar, et à sa secrétaire, une consœur à

laquelle elle était très attachée Richardis de Strade. Comme cela est toujours

le cas dans la vie des véritables mystiques, Hildegarde voulut se soumettre

aussi à l’autorité de personnes sages pour discerner l’origine de ses visions,

craignant qu’elles soient le fruit d’illusions et qu’elles ne viennent pas de

Dieu. Elle s’adressa donc à la personne qui, à l’époque, bénéficiait de la plus

haute estime dans l’Eglise: saint Bernard de Clairvaux, dont j’ai déjà parlé

dans certaines catéchèses. Celui-ci rassura et encouragea Hildegarde. Mais en

1147, elle reçut une autre approbation très importante. Le Pape Eugène III, qui

présidait un synode à Trèves, lut un texte dicté par Hildegarde, qui lui avait

été présenté par l’archevêque Henri de Mayence. Le Pape autorisa la mystique à

écrire ses visions et à parler en public. A partir de ce moment, le prestige

spirituel d’Hildegarde grandit toujours davantage, d’autant plus que ses

contemporains lui attribuèrent le titre de «prophétesse teutonique». Tel est,

chers amis, le sceau d’une expérience authentique de l’Esprit Saint, source de

tout charisme: la personne dépositaire de dons surnaturels ne s’en vante

jamais, ne les affiche pas, et surtout, fait preuve d’une obéissance totale à

l’autorité ecclésiale. En effet, chaque don accordé par l’Esprit Saint est

destiné à l’édification de l’Eglise, et l’Eglise, à travers ses pasteurs, en

reconnaît l’authenticité.

Je parlerai encore une

fois mercredi prochain de cette grande femme «prophétesse», qui nous parle avec

une grande actualité aujourd’hui aussi, à travers sa capacité courageuse à

discerner les signes des temps, son amour pour la création, sa médecine, sa

poésie, sa musique, qui est aujourd’hui reconstruite, son amour pour le Christ

et pour son Eglise, qui souffrait aussi en ce temps-là, blessée également à

cette époque par les péchés des prêtres et des laïcs, et d’autant plus aimée

comme corps du Christ. Ainsi, sainte Hilegarde nous parle-t-elle; nous

l’évoquerons encore mercredi prochain. Merci pour votre attention.

* * *

Je salue avec joie les

pèlerins francophones, en particulier l’aumônerie des jeunes travailleurs du

Golfe de Saint Tropez. À la suite de Sainte Hildegarde dont je parlerai plus

amplement prochainement, puissiez-vous, chers frères et sœurs, vous laisser instruire

par l’Esprit Saint. Vous découvrirez alors les dons que le Seigneur vous fait

pour le service de l’Église et du monde entier. Bon pèlerinage à tous et bonne

rentrée à ceux qui vont reprendre leur travail ou le chemin des études. Je

pense particulièrement aux enfants et aux jeunes.

© Copyright 2010 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100901.html

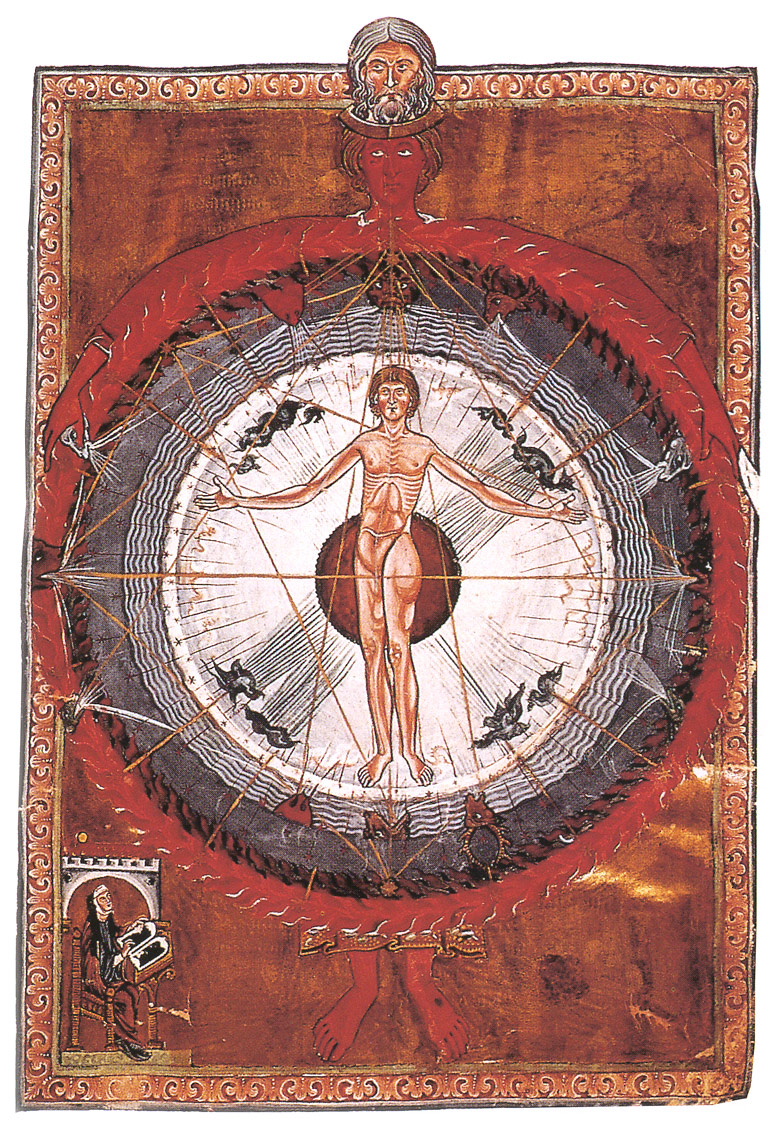

The

Universal Man, Liber divinorum operum of St.

Hildegard of Bingen, 1165 Copy of the XIIIth century. Biblioteca statale, Lucca

(Italia)

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI

Mercredi 8 septembre

2010

Sainte Hildegarde (2)

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais aujourd’hui

reprendre et poursuivre la réflexion sur sainte Hildegarde de Bingen, figure

importante de femme au Moyen âge, qui se distingua par sa sagesse spirituelle

et la sainteté de sa vie. Les visions mystiques d’Hildegarde ressemblent à celles

des prophètes de l’Ancien Testament: s’exprimant à travers les expressions

culturelles et religieuses de son époque, elle interprétait à la lumière de

Dieu les Saintes Ecritures, les appliquant aux diverses circonstances de la

vie. Ainsi, tous ceux qui l’écoutaient se sentaient exhortés à pratiquer un

style d’existence chrétienne cohérent et engagé. Dans une lettre à saint

Bernard, la mystique de Rhénanie confesse: «La vision envahit tout mon être: je

ne vois plus avec les yeux du corps, mais elle m’apparaît dans l’esprit des

mystères... Je connais la signification profonde de ce qui est exposé dans le

psautier, dans l’Evangile, et d’autres livres, qui m’apparaissent en vision.

Celle-ci brûle comme une flamme dans ma poitrine et dans mon âme, et m’enseigne

à comprendre en profondeur le texte» (Epitolarium pars prima I-XC: CCCM

91).

Les visions mystiques

d’Hildegarde sont riches de contenus théologiques. Elles font référence aux

événements principaux de l’histoire du salut, et adoptent un langage principalement

poétique et symbolique. Par exemple, dans son œuvre la plus célèbre,

intitulée Scivias, c’est-à-dire «Connais les voies», elle résume en

trente-cinq visions les événements de l’histoire du salut, de la création du

monde à la fin des temps. Avec les traits caractéristiques de la sensibilité

féminine, Hildegarde, précisément dans la partie centrale de son œuvre,

développe le thème du mariage mystique entre Dieu et l’humanité réalisé dans

l’Incarnation. Sur l’arbre de la Croix s’accomplissent les noces du Fils de

Dieu avec l’Eglise, son épouse, emplie de grâce et rendue capable de donner à

Dieu de nouveaux fils, dans l’amour de l’Esprit Saint (cf. Visio tertia:

PL 197, 453c).

A partir de ces brèves

évocations, nous voyons déjà que la théologie peut également recevoir une

contribution particulière des femmes, car elles sont capables de parler de Dieu

et des mystères de la foi à travers leur intelligence et leur sensibilité

particulières. J’encourage donc toutes celles qui accomplissent ce service à

l’accomplir avec un profond esprit ecclésial, en nourrissant leur réflexion à

la prière et en puisant à la grande richesse, encore en partie inexplorée, de

la tradition mystique médiévale, surtout celle représentée par des modèles

lumineux, comme le fut précisément Hildegarde de Bingen.

La mystique rhénane est

aussi l'auteur d'autres écrits, dont deux particulièrement importants parce

qu'ils témoignent, comme le Scivias, de ses visions mystiques: ce sont

le Liber vitae meritorum (Livre des mérites de la vie) et le Liber

divinorum operum (Livre des œuvres divines), appelé aussi De

operatione Dei. Dans le premier est décrite une unique et vigoureuse vision de

Dieu qui vivifie l’univers par sa force et sa lumière. Hildegarde souligne la

profonde relation entre l'homme et Dieu et nous rappelle que toute la création,

dont l'homme est le sommet, reçoit la vie de la Trinité. Cet écrit est centré

sur la relation entre les vertus et les vices, qui fait que l'être humain doit

affronter chaque jour le défi des vices, qui l'éloignent dans son cheminement

vers Dieu et les vertus, qui le favorisent. L'invitation est de s'éloigner du

mal pour glorifier Dieu et pour entrer, après une existence vertueuse, dans la

vie «toute de joie». Dans la seconde œuvre, considérée par beaucoup comme son

chef-d'œuvre, elle décrit encore la création dans son rapport avec Dieu et la

place centrale de l’homme, en manifestant un fort christocentrisme aux accents

bibliques et patristiques. La sainte, qui présente cinq visions inspirées par

le Prologue de l'Evangile de saint Jean, rapporte les paroles que le Fils

adresse au Père: «Toute l’œuvre que tu as voulue et que tu m'as confiée, je

l'ai menée à bien, et voici que je suis en toi, et toi en moi, et que nous

sommes un» (Pars III, Visio X: PL 197, 1025a).

Dans d’autres écrits,

enfin, Hildegarde manifeste la versatilité des intérêts et la vivacité

culturelle des monastères féminins du Moyen âge, à contre-courant des préjugés

qui pèsent encore sur l'époque. Hildegarde s'occupa de médecine et de sciences

naturelles, ainsi que de musique, étant doté de talent artistique. Elle composa

aussi des hymnes, des antiennes et des chants, réunis sous le titre de Symphonia

Harmoniae Caelestium Revelationum (Symphonie de l'harmonie des révélations

célestes), qui étaient joyeusement interprétés dans ses monastères, diffusant

un climat de sérénité, et qui sont également parvenus jusqu'à nous. Pour elle,

la création tout entière est une symphonie de l'Esprit Saint, qui est en soi

joie et jubilation.

La popularité dont

Hildegarde jouissait poussait de nombreuses personnes à l’interpeller. C’est

pour cette raison que nous disposons d’un grand nombre de ses lettres. Des

communautés monastiques masculines et féminines, des évêques et des abbés

s’adressaient à elle. De nombreuses réponses restent valable également pour

nous. Par exemple, Hildegarde écrivit ce qui suit à une communauté religieuse

féminine: «La vie spirituelle doit faire l’objet de beaucoup de dévouement. Au

début, la fatigue est amère. Car elle exige la renonciation aux manifestations

extérieures, au plaisir de la chair et à d’autres choses semblables. Mais si

elle se laisse fasciner par la sainteté, une âme sainte trouvera doux et plein

d’amour le mépris même du monde. Il suffit seulement, avec intelligence, de

faire attention à ce que l’âme ne se fane pas» (E. Gronau, Hildegard. Vita

di una donna profetica alle origini dell’età moderna, Milan 1996, p. 402).

Et lorsque l’empereur Frédéric Barberousse fut à l’origine d’un schisme

ecclésial opposant trois antipapes au Pape légitime Alexandre III, Hildegarde,

inspirée par ses visions, n’hésita pas à lui rappeler qu’il était lui aussi

sujet au jugement de Dieu. Avec l’audace qui caractérise chaque prophète, elle

écrivit à l’empereur ces mots de la part de Dieu: «Attention, attention à cette

mauvaise conduite des impies qui me méprisent! Prête-moi attention, ô roi, si

tu veux vivre! Autrement mon épée te transpercera!» (ibid., p. 142).

Avec l’autorité

spirituelle dont elle était dotée, au cours des dernières années de sa vie,

Hildegarde se mit en voyage, malgré son âge avancé et les conditions difficiles

des déplacements, pour parler de Dieu aux populations. Tous l’écoutaient

volontiers, même lorsqu’elle prenait un ton sévère: ils la considéraient comme

une messagère envoyée par Dieu. Elle rappelait surtout les communautés

monastiques et le clergé à une vie conforme à leur vocation. De manière

particulière, Hildegarde s’opposa au mouvement des cathares allemands.

Ces derniers — littéralement cathares signifie «purs» — prônaient une

réforme radicale de l’Eglise, en particulier pour combattre les abus du clergé.

Elle leur reprocha sévèrement de vouloir renverser la nature même de l’Eglise,

en leur rappelant qu’un véritable renouvellement de la communauté ecclésiale ne

s’obtient pas tant avec le changement des structures, qu’avec un esprit de

pénitence sincère et un chemin actif de conversion. Il s’agit là d’un message

que nous ne devrions jamais oublier. Invoquons toujours l’Esprit Saint afin

qu’il suscite dans l’Eglise des femmes saintes et courageuses, comme sainte

Hildegarde de Bingen, qui, en valorisant les dons reçus par Dieu, apportent

leur contribution précieuse et spécifique à la croissance spirituelle de nos

communautés!

* * *

Je salue les pèlerins

francophones présents particulièrement les pèlerins venus de Metz et de Saint

Just d’Arbois. Je ne désire pas oublier le Secrétaire et les membres de

l’Assemblée Parlementaire du Conseil de l’Europe qui ont tenu à être présent ce

matin, ainsi que des membres de l’association des retraités du Ministère des

Affaires Etrangères. Puissiez-vous à l’exemple de sainte Hildegarde continuer à

chercher Dieu! Bon pèlerinage à tous!

MESSAGE VIDÉO POUR

LA VISITE

AU ROYAUME-UNI

J’attends avec beaucoup

de plaisir ma visite au Royaume-Uni dans une semaine, et j’adresse des

salutations sincères à tout le peuple de Grande-Bretagne. Je suis conscient

qu’un immense travail a été accompli en vue de la préparation de ma visite, non

seulement par la communauté catholique, mais par le gouvernement, les autorités

locales en Ecosse, à Londres et à Birmingham, les moyens de communications et

les services de sécurité, et je voudrais dire combien j’apprécie les efforts

qui ont été accomplis afin de garantir que les divers événements au programme

soient des célébrations véritablement joyeuses. Je remercie avant tout les

innombrables personnes qui ont prié pour le succès de cette visite et pour une

abondante effusion de la grâce de Dieu sur l’Eglise et sur les habitants de

votre nation.

Ce sera en particulier

une joie pour moi de béatifier le vénérable John Henry Newman à Birmingham, le

dimanche 19 septembre. Cet Anglais remarquable a vécu une vie sacerdotale

exemplaire et, à travers ses écrits, a apporté une contribution durable à

l’Eglise et à la société dans son pays natal et dans de nombreuses autres

parties du monde. Je forme le vœu et la prière que toujours plus de personnes bénéficient

de sa sagesse et soient inspirées par son exemple d’intégrité et de sainteté de

vie.

J’attends avec plaisir de

rencontrer les représentants des nombreuses et diverses traditions religieuses

et culturelles, qui composent la population britannique, ainsi que les

responsables civils et politiques. Je suis profondément reconnaissant à Sa

Majesté la reine et à Sa Grâce l’archevêque de Canterbury de me recevoir, et

j’attends avec plaisir de les rencontrer. Tandis que je regrette de ne pouvoir

visiter de nombreux lieux et rencontrer de nombreuses personnes, je vous assure

tous de mes prières. Dieu bénisse le peuple du Royaume-Uni!

© Copyright 2010 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100908.html

Reliques d'Hildegarde de Bingen et de Saint Bernard de Clairvaux au sanctuaire de Lourdes, les reliques sont actuellement conservées dans la chapelle 'Pax Christi' à la Basilique Saint-Pie X de Lourdes.

Reliques d'Hildegarde de Bingen et de Saint Bernard de Clairvaux au sanctuaire de Lourdes, les reliques sont actuellement conservées dans la chapelle 'Pax Christi' à la Basilique Saint-Pie X de Lourdes.

Reliques

d'Hildegarde de Bingen et de Saint Bernard de Clairvaux au sanctuaire de

Lourdes, les reliques sont actuellement conservées dans la chapelle 'Pax

Christi' à la Basilique Saint-Pie X de Lourdes.

HOMÉLIE DU PAPE BENOÎT

XVI

Vénérés Frères,

Chers frères et sœurs,

Avec cette concélébration

solennelle, nous inaugurons la XIIIe Assemblée

générale ordinaire du Synode des Évêques, qui a pour thème : La

nouvelle évangélisation pour la transmission de la foi chrétienne. Ce

thème répond à une orientation programmatique pour la vie de l’Église, de tous

ses membres, des familles, des communautés, et de ses institutions. Et cette

perspective est renforcée par la coïncidence avec le début de l’Année de la foi, qui aura

lieu jeudi prochain, 11 octobre, à l’occasion du 50° anniversaire de

l’ouverture du Concile

Œcuménique Vatican II. Je vous adresse ma cordiale et reconnaissante

bienvenue à vous, qui êtes venus former cette Assemblée synodale,

particulièrement au Secrétaire Général du Synode des Évêques et à ses collaborateurs.

J’étends mon salut aux Délégués fraternels des autres Églises et Communautés

ecclésiales et à tous ceux qui sont ici présents, en les invitant à accompagner

par la prière quotidienne les travaux qui se dérouleront dans les trois

prochaines semaines.

Les lectures bibliques

qui forment la Liturgie de la Parole de ce dimanche nous offrent deux

principaux points de réflexion : le premier sur le mariage, que j’aimerais

aborder plus loin ; le second sur Jésus Christ, que je reprends

immédiatement. Nous n’avons pas le temps pour commenter le passage de la Lettre

aux Hébreux, mais au début de cette Assemblée synodale, nous devons accueillir

l’invitation à fixer le regard sur le Seigneur Jésus, « couronné de gloire

et d’honneur à cause de sa Passion et de sa mort » (He 2, 9). La

Parole de Dieu nous place devant le Crucifié glorieux, de sorte que toute notre

vie, et particulièrement les travaux de cette Assise synodale, se déroulent en

sa présence et dans la lumière de son mystère. L’évangélisation, en tout temps

et en tout lieu, a toujours comme point central et d’arrivée Jésus, le Christ,

le Fils de Dieu (cf. Mc 1, 1) ; et le Crucifié est le signe

distinctif par excellence de celui qui annonce l’Évangile : signe d’amour

et de paix, appel à la conversion et à la réconciliation. Nous, les premiers,

vénérés Frères, gardons le regard du cœur tourné vers Lui et laissons-nous

purifier par sa grâce.

Maintenant, je voudrais

réfléchir brièvement sur la « nouvelle évangélisation », en la

mettant en rapport avec l’évangélisation ordinaire et avec la mission ad

gentes. L’Église existe pour évangéliser. Fidèles au commandement du Seigneur

Jésus Christ, ses disciples sont allés dans le monde entier pour annoncer la

Bonne Nouvelle, en fondant partout les communautés chrétiennes. Avec le temps,

elles sont devenues des Églises bien organisées avec de nombreux fidèles. À des

périodes historiques déterminées, la divine Providence a suscité un dynamisme

renouvelé de l’activité évangélisatrice de l’Église. Il suffit de penser à l’évangélisation

des peuples anglo-saxons et des peuples slaves, ou à la transmission de

l’Évangile sur le continent américain, et ensuite aux époques missionnaires

vers les populations de l’Afrique, de l’Asie et de l’Océanie. Sur cet

arrière-plan dynamique, il me plaît aussi de regarder les deux figures

lumineuses que je viens de proclamer Docteurs de l’Église : Saint Jean

d’Avila et Sainte Hildegarde de Bingen. Dans notre temps, l’Esprit Saint a

aussi suscité dans l’Église un nouvel élan pour annoncer la Bonne Nouvelle, un

dynamisme spirituel et pastoral qui a trouvé son expression la plus universelle

et son impulsion la plus autorisée dans le Concile

Vatican II. Ce nouveau dynamisme de l’évangélisation produit une influence

bénéfique sur deux « branches » spécifiques qui se développent à

partir d’elle, à savoir, d’une part, la missio ad gentes, c’est-à-dire

l’annonce de l’Évangile à ceux qui ne connaissent pas encore Jésus Christ et

son message de salut ; et, d’autre part, la nouvelle

évangélisation, orientée principalement vers les personnes qui, tout en

étant baptisées, se sont éloignées de l’Église, et vivent sans se référer à la

pratique chrétienne. L’Assemblée synodale qui s’ouvre aujourd’hui est consacrée

à cette nouvelle évangélisation, pour favoriser chez ces personnes, une

nouvelle rencontre avec le Seigneur, qui seul remplit notre existence de sens

profond et de paix ; pour favoriser la redécouverte de la foi, source de

grâce qui apporte la joie et l’espérance dans la vie personnelle, familiale et

sociale. Évidemment, cette orientation particulière ne doit diminuer ni l’élan

missionnaire au sens propre, ni l’activité ordinaire d’évangélisation dans nos

communautés chrétiennes. En effet, les trois aspects de l’unique réalité de

l’évangélisation se complètent et se fécondent réciproquement.

Le thème du mariage, qui

nous est proposé par l’Évangile et la première Lecture, mérite à ce propos une

attention spéciale. On peut résumer le message de la Parole de Dieu dans

l’expression contenue dans le Livre de la Genèse et reprise par Jésus

lui-même : « à cause de cela, l’homme quittera son père et sa mère,

il s’attachera à sa femme, et tous deux ne feront qu’une seule chair » (Gn 2,

24 ; Mc 10, 7-8). Qu’est-ce que cette Parole nous dit

aujourd’hui ? Il me semble qu’elle nous invite à être plus conscients

d’une réalité déjà connue mais peut-être pas valorisée pleinement :

c’est-à-dire que le mariage en lui-même est un Évangile, une Bonne Nouvelle

pour le monde d’aujourd’hui, particulièrement pour le monde déchristianisé.

L’union de l’homme et de la femme, le fait de devenir « une seule

chair » dans la charité, dans l’amour fécond et indissoluble, est un signe

qui parle de Dieu avec force, avec une éloquence devenue plus grande de nos

jours, car, malheureusement, pour diverses raisons, le mariage traverse une

crise profonde justement dans les régions d’ancienne évangélisation. Et ce

n’est pas un hasard. Le mariage est lié à la foi, non pas dans un sens

générique. Le mariage, comme union d’amour fidèle et indissoluble, se fonde sur

la grâce qui vient de Dieu, Un et Trine, qui, dans le Christ, nous a aimés d’un

amour fidèle jusqu’à la Croix. Aujourd’hui, nous sommes en mesure de saisir

toute la vérité de cette affirmation, en contraste avec la douloureuse réalité

de beaucoup de mariages qui malheureusement finissent mal. Il y a une

correspondance évidente entre la crise de la foi et la crise du mariage. Et,

comme l’Église l’affirme et en témoigne depuis longtemps, le mariage est appelé

à être non seulement objet, mais sujet de la nouvelle évangélisation. Cela se

vérifie déjà dans de nombreuses expériences, liées à des communautés et

mouvements, mais se réalise aussi de plus en plus dans le tissu des diocèses et

des paroisses, comme l’a montré la récente Rencontre

Mondiale des Familles.

Une des idées

fondamentales de la nouvelle impulsion que le Concile

Vatican II a donnée à l’évangélisation est celle de l’appel universel

à la sainteté, qui, comme tel, concerne tous les chrétiens (cf. Const. Lumen

gentium, nn. 39-42). Les saints sont les vrais protagonistes de

l’évangélisation dans toutes ses expressions. Ils sont aussi, d’une manière

particulière, les pionniers et les meneurs de la nouvelle évangélisation :

par leur intercession et par l’exemple de leur vie, attentive à la créativité

de l’Esprit Saint, ils montrent aux personnes indifférentes et même hostiles,

la beauté de l’Évangile et de la communion dans le Christ, et ils invitent les

croyants tièdes, pour ainsi dire, à vivre dans la joie de la foi, de l’espérance

et de la charité, à redécouvrir le « goût » de la Parole de Dieu et

des Sacrements, particulièrement du Pain de vie, l’Eucharistie. Les saints et

les saintes fleurissent parmi les missionnaires généreux qui annoncent la Bonne

Nouvelle aux non-chrétiens, traditionnellement dans les pays de mission et

actuellement en tout lieu où vivent des personnes non chrétiennes. La sainteté

ne connaît pas de barrières culturelles, sociales, politiques, religieuses. Son

langage – celui de l’amour et de la vérité – est compréhensible par tous les

hommes de bonne volonté et les rapproche de Jésus Christ, source intarissable

de vie nouvelle.

Maintenant, arrêtons-nous

un instant pour admirer les deux Saints qui ont été associés aujourd’hui au

noble rang des Docteurs de l’Église. Saint Jean d’Avila a vécu au XVIe siècle.

Grand connaisseur des Saintes Écritures, il était doté d’un ardent esprit

missionnaire. Il a su pénétrer avec une profondeur singulière les mystères de

la Rédemption opérée par le Christ pour l’humanité. Homme de Dieu, il unissait

la prière constante à l’action apostolique. Il s’est consacré à la prédication

et au développement de la pratique des sacrements, en concentrant sa mission

sur l’amélioration de la formation des candidats au sacerdoce, des religieux et

des laïcs, en vue d’une réforme féconde de l’Église.

Importante figure

féminine du XIIe siècle, Sainte Hildegarde de Bingen a offert sa précieuse

contribution pour la croissance de l’Église de son temps, en valorisant les

dons reçus de Dieu et en se montrant comme une femme d’une intelligence vivace,

d’une sensibilité profonde et d’une autorité spirituelle reconnue. Le Seigneur

l’a dotée d’un esprit prophétique et d’une fervente capacité à discerner les

signes des temps. Hildegarde a nourri un amour prononcé pour la création ;

elle a pratiqué la médecine, la poésie et la musique. Et surtout, elle a

toujours conservé un amour grand et fidèle pour le Christ et pour son Église.

Le regard sur l’idéal de

la vie chrétienne, exprimé dans l’appel à la sainteté, nous pousse à considérer

avec humilité la fragilité de tant de chrétiens, ou plutôt leur péché –

personnel et communautaire – qui représente un grand obstacle pour

l’évangélisation, et à reconnaître la force de Dieu qui, dans la foi, rencontre

la faiblesse humaine. Par conséquent, on ne peut pas parler de la nouvelle

évangélisation sans une disposition sincère de conversion. Se laisser

réconcilier avec Dieu et avec le prochain (cf. 2 Co 5, 20) est la

voie royale pour la nouvelle évangélisation. C’est seulement purifiés que les

chrétiens peuvent retrouver la fierté légitime de leur dignité d’enfants de

Dieu, créés à son image et sauvés par le sang précieux de Jésus Christ, et

peuvent expérimenter sa joie afin de la partager avec tous, avec ceux qui sont

proches et avec ceux qui sont loin.

Chers frères et sœurs,

confions à Dieu les travaux de l’Assise synodale, dans le vif sentiment de la

communion des Saints, en invoquant particulièrement l’intercession des grands

évangélisateurs, au nombre desquels nous voulons compter le Bienheureux

Pape Jean-Paul

II, dont le long pontificat a été aussi un exemple de nouvelle

évangélisation. Nous nous mettons sous la protection de la Bienheureuse Vierge

Marie, Etoile de la nouvelle évangélisation. Avec elle, invoquons une effusion

spéciale de l’Esprit Saint ; que d’en-haut il illumine l’Assemblée

synodale et la rende fructueuse pour la marche de l’Église

aujourd'hui, dans notre temps. Amen.

© Copyright 2012 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastère

pour la Communication

St. Nikolaus (Koblenz-Arenberg), Fenster im Seitenschiff, St. Hildegard von Bingen, Fa. Binsfeld, um 1950

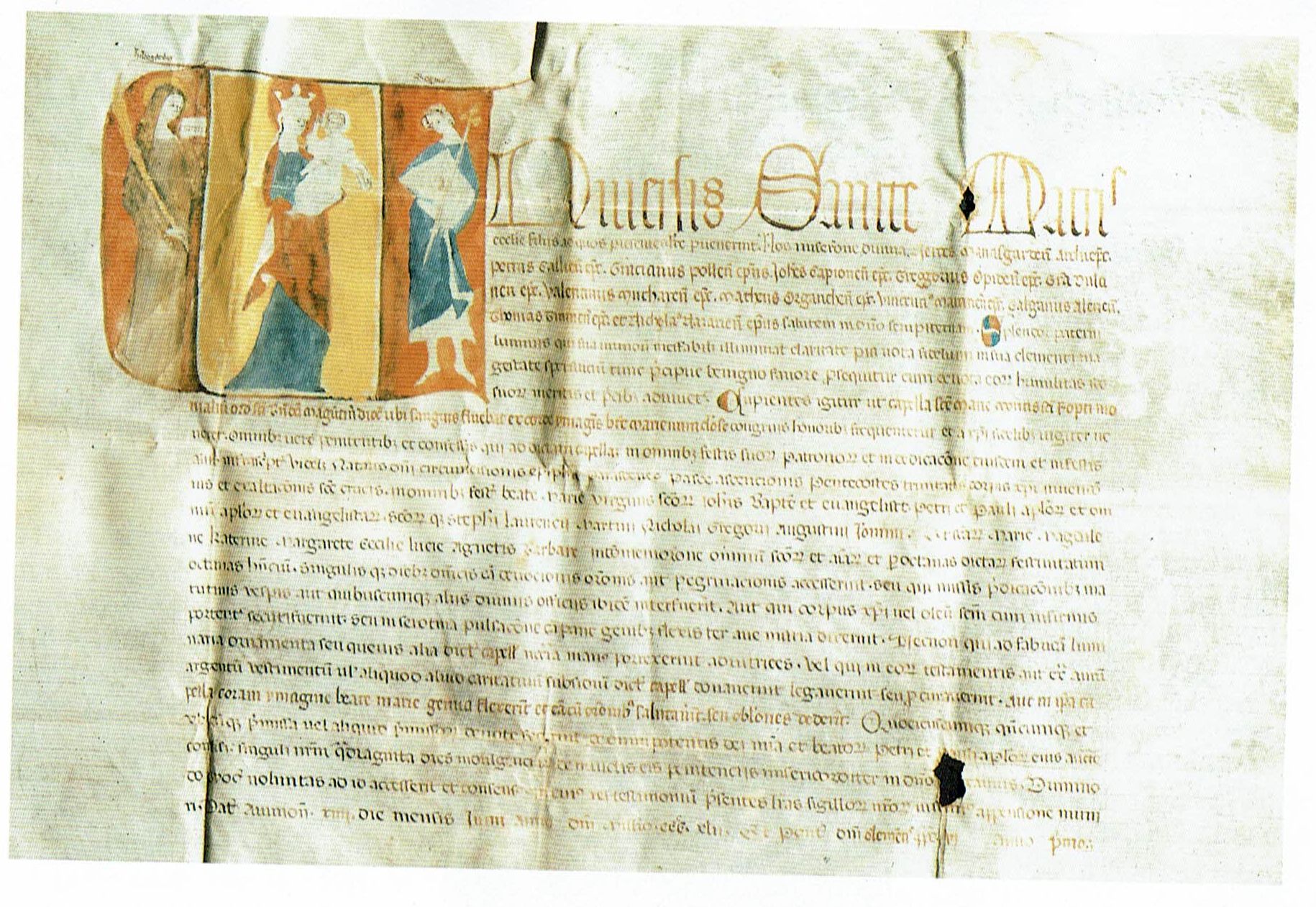

Décret apostolique pour

la proclamation de sainte Hildegarde de Bingen Docteur de l’Église

Benoît XVI, pape

en perpétuelle mémoire.

1. « Lumière de

sa nation et de son temps » : c’est par ces mots que notre

prédécesseur, le bienheureux Jean-Paul II, saluait en 1979 Ste Hildegarde, à

l’occasion du 800e anniversaire de la mort de la mystique allemande.

Effectivement, cette femme éminente se détache sur l’horizon de l’Histoire par

la sainteté de sa vie et l’originalité de son enseignement. Oui, comme c’est le

cas pour toute expérience humaine et théologale authentique, son autorité

dépasse vraiment le cadre d’une époque et d’une société, et abstraction faite

de la distance chronologique et culturelle, sa pensée apparaît toujours

actuelle.

La vie quotidienne de Ste

Hildegarde se révèle en parfaite harmonie avec son enseignement. Chez elle

s’expriment la recherche de la volonté de Dieu et la suite du Christ comme une

constante mise en pratique des vertus, qu’elle cultive avec le plus grand soin

et nourrit aux sources bibliques, liturgiques et patristiques, ainsi qu’à la

lumière de la Règle de St Benoît. En elle rayonne de façon toute particulière

l’exercice persévérant de l’obéissance, de la simplicité, de la charité et de

l’hospitalité. Dans son adhésion totale à Dieu, elle s’est distinguée par ses

dons humains singuliers, son intelligence vive ainsi que par sa capacité à

scruter les réalités divines.

2. Hildegarde est

née en 1098 à Bermersheim près d’Alzey ; ses parents étaient de nobles

propriétaires fonciers. À l’âge de huit ans, Hildegarde fut confiée comme

oblate à l’abbaye bénédictine du Disibodenberg, où elle prononça ses vœux en

1115. À la mort de Jutta de Sponheim, en 1136, Hildegarde fut nommée pour lui

succéder comme magistra. De faible constitution physique mais dotée d’un

puissant esprit, elle se consacra avec un soin spécial au renouveau de la vie

religieuse. Le fondement de sa spiritualité était la Règle bénédictine,

qui trace un chemin vers la sainteté fait d’équilibre et d’ascèse mesurée. En

raison du nombre croissant des moniales, ce qu’il convient d’attribuer avant

tout à la haute estime liée à sa personne, elle fonda en 1150 un monastère sur

une colline – le Rupertsberg près de Bingen – où elle se rendit avec vingt

sœurs. Elle fonda en 1165 un autre monastère à Eibingen, de l’autre côté du

Rhin. Elle était abbesse des deux monastères.

Au sein du monastère,

elle prit soin du bien-être spirituel et matériel de ses sœurs en favorisant

spécialement la vie commune, la culture et la liturgie. En dehors du monastère,

elle s’efforça de fortifier la foi chrétienne et d’affermir la pratique

religieuse en s’opposant aux tendances hérétiques des Cathares ; elle

favorisa par ses écrits et prédications la réforme de l’Église et contribua à

l’amélioration de la discipline et de la vie du clergé. À l’invitation de

Hadrien IV et ensuite d’Alexandre III, Hildegarde exerça un apostolat fécond –

ce qui n’était guère usuel à l’époque pour une femme – , elle entreprit de

nombreux voyages, qui n’étaient pas sans dangers ni difficultés, afin

d’exhorter aussi sur les places publiques et dans quelques cathédrales, entre

autres Cologne, Trêves, Lüttich, Mayence, Metz, Bamberg et Würzburg. La

profonde spiritualité de ses écrits exerce une influence notable sur les

fidèles et les hautes personnalités de son temps, car elle s’intègre dans un

puissant renouvellement de la théologie, de la liturgie, des sciences et de la

musique.

Atteinte durant l’été

1179 d’une grave maladie, Hildegarde mourut en odeur de sainteté le 17

septembre 1179 au monastère du Rupertsberg, près de Bingen, entourée de ses

sœurs.

3. Dans ses nombreux

écrits, Hildegarde se consacre exclusivement à l’exposé de la révélation divine

et à l’annonce de Dieu dans la clarté de son amour. Son enseignement se

distingue par la hauteur et la droiture de ses interprétations comme aussi par

l’originalité de ses visions. Ses textes paraissent animés d’une authentique

« intelligence d’amour » et expriment leur profondeur et fraîcheur

dans la contemplation du mystère de la Très Sainte Trinité, de l’Incarnation,

de l’Église, de l’Humanité et de la Nature qui, en tant qu’œuvre de Dieu, doit

être estimée et respectée.

Ses œuvres sont le fruit

d’une expérience mystique profonde et offrent une réflexion effective sur le

mystère de Dieu. Déjà enfant, le Seigneur l’avait gratifiée d’une série de

visions, dont elle avait raconté le contenu au moine Volmar, son secrétaire et directeur

spirituel, ainsi qu’à une sœur, la moniale Richardis de Stade. Particulièrement

éclairant reste cependant le jugement de St Bernard de Clairvaux, qui

l’encouragea, et surtout celui du pape Eugène III, lequel l’autorisa en 1147 à

écrire et à parler en public. La réflexion théologique permit à Hildegarde

d’exposer de façon thématique le contenu de ses visions et, au moins en parti,

de les comprendre. En dehors de livres de théologie et de mystique, elle

rédigea aussi des œuvres consacrées à la médecine et à la Science. Ses lettres

sont aussi très nombreuses – environ 400 – , qu’elle adressa à des gens

simples, des communautés religieuses, des papes, des évêques et aux autorités

séculières de son temps. Elle fut aussi compositrice de musique spirituelle.

Par son ampleur, sa qualité et sa variété, le recueil de ses écrits est sans

comparaison chez les femmes du Moyen-Âge.

Les œuvres majeures

sont : le Scivias (Sache les voies), le Liber vitae

meritorum (le Livre des mérites de la vie) et le Liber divinorum

operum (le Livre des œuvres divines). Tous racontent ses visions et le

commandement reçu du Seigneur de les mettre par écrit. Ses Lettres n’ont

pas moins d’intérêt, comme Hildegarde l’estime elle-même, car elles manifestent

son attention pour les événements de son temps, qu’elle interprète à la lumière

des mystères divins. Il convient d’ajouter 58 Sermons, adressés

exclusivement à ses sœurs. Il s’agit d’Expositiones evangeliorum (explications

des Évangiles), qui contiennent un commentaire littéral et moral pour les

péricopes évangéliques lues aux grandes fêtes de l’année liturgique. Les

travaux de caractère artistique et scientifique se concentrent de façon

particulière au domaine de la musique, avec la Symphonia armoniae

caelestium revelationum ; au domaine de la science avec les Physica ;

au domaine de la médecine avec le Liber subtilitatum diversarum naturarum

creaturarum et l’œuvre Causae et curae. Enfin, il importe de mentionner

des écrits de caractère philologique, comme la Lingua ignota et

les Litterae ignotae, dans lesquels apparaissent des mots dans une langue

inconnue inventée par Hildegarde seule, mais qui sont composés principalement

de phonèmes présents dans la langue allemande.

La langue de Hildegarde,

caractérisée par un style original et fortement expressif, puise volontiers

dans un registre poétique à la force symbolique puissante, avec des intuitions

lumineuses, des analogies concises et des métaphores saisissantes.

4. Hildegarde dirige

son regard sur l’événement de la Révélation avec une sensibilité aiguë, sage et

prophétique. Son étude se déploie à partir de la Bible, à laquelle elle reste

fermement attachée au cours des phases suivantes. Le regard de la mystique de

Bingen ne se limite pas à résoudre quelques questions, elle veut au contraire

offrir une synthèse de toute la foi chrétienne. Elle résume ainsi, dans ses

visions et les réflexions suivantes, toute l’Histoire du Salut à partir du

commencement de l’univers jusqu’au dernier jour. La décision de Dieu de

réaliser l’œuvre de la Création est le premier pas de cet immense chemin, qui

se déroule, à la lumière de la Sainte Écriture, de la constitution de la

hiérarchie céleste jusqu’à la chute de l’ange et au péché originel de nos

premiers parents. À cette image des commencements succèdent l’œuvre salutaire

du Fils de Dieu, l’action de l’Église, qui poursuit dans le temps le mystère de

l’Incarnation et la lutte contre Satan. La venue finale du Règne de Dieu et le

Jugement dernier seront le couronnement de cette œuvre.

Hildegarde se demande, à

elle-même et à nous aussi, s’il est possible de connaître Dieu ; c’est la

tâche fondamentale de la théologie. Sa réponse est des plus affirmative :

par la foi, comme par une porte, l’homme est dans la mesure de s’approcher de

cette connaissance. Dieu, cependant, se réserve toujours un lieu de mystère

insondable. Il est connaissable dans la création qui, de son côté, n’est pas

entièrement connue si elle est séparée de Dieu. En effet, la nature considérée

en elle-même ne fournit que des informations partielles, et il n’est pas rare

qu’elles soient motifs d’erreurs ou d’abus. C’est pourquoi, dans la dynamique

de la connaissance naturelle, a-t-on besoin de la foi, sinon la connaissance

est limitée, peu satisfaisante et source d’égarement.

La Création est un acte

d’amour, par lequel l’univers peut surgir du néant : c’est pourquoi

l’ensemble des créatures s’écoule comme un fleuve de l’amour divin. Parmi les

créatures, Dieu aime spécialement l’homme et lui confie une dignité

particulière en lui offrant la gloire que les anges déchus ont perdue.

L’humanité peut ainsi être considérée comme le dixième chœur de la hiérarchie

angélique. L’homme est dans la mesure de connaître Dieu en lui-même,

c’est-à-dire son essence individuelle dans la trinité des personnes. Hildegarde

aborde le mystère de la Ste Trinité selon une approche que proposait déjà St

Augustin : par une ressemblance avec sa constitution de créature

raisonnable, l’homme est en mesure de se forger au moins une image de la

réalité intime de Dieu. Mais c’est seulement dans l’économie de l’Incarnation

et de l’histoire humaine du Fils de Dieu que ce mystère devient accessible à la

foi et à la conscience de l’homme. La Trinité et suprême unité sainte et

ineffable demeure cachée aux serviteurs de la Loi ancienne, mais, dans le

régime de la grâce, elle a été dévoilée à ceux qui ont été délivrés de la

servitude. La Trinité a été révélée de façon toute particulière dans la Croix

du Fils.

Un deuxième

« lieu », où Dieu se fait connaître, est sa Parole contenue dans les

livres de l`Ancien et du Nouveau Testament. C’est justement parce que Dieu

« parle » que l’homme est appelé à écouter. Cette approche donne à

Hildegarde l’occasion d’exposer son enseignement sur le chant, spécialement le

chant liturgique. L’écho des paroles divines est créateur de vie et se révèle

dans les créatures. Même les créatures non raisonnables sont intégrées dans la

dynamique créatrice grâce à la parole qui crée. Mais c’est naturellement

l’homme qui est la créature pouvant, avec sa voix, répondre à la voix du

Créateur, et il peut le faire principalement de deux manières : in

voce oris – avec la voix orale, c’est-à-dire dans la célébration de la

liturgie – et in voce cordis, avec la voix du cœur, c’est-à-dire par une

vie vertueuse et sainte. L’ensemble de la vie humaine peut ainsi être

interprétée comme une symphonie et une harmonie.

5. L’anthropologie

de Hildegarde prend comme point de départ le récit biblique de la création de

l’homme à l’image et à la ressemblance de Dieu (Gn 1, 26). Selon la cosmologie

de Hildegarde fondée sur la Bible, l’homme contient tous les éléments du monde,

parce qu’il est formé de la même matière que la création et résume en lui

l’ensemble de l’univers. C’est pourquoi il peut entrer en relation avec Dieu de

façon tout à fait consciente. Cela ne se réalise pas par une vision directe,

mais, selon la célèbre expression de Paul, « comme en un miroir » (1

Co 13, 12). L’image divine en l’homme consiste en sa nature raisonnable, qui se

compose d’intelligence et de volonté. Par l’intelligence, l’homme est capable

de discerner le bien et le mal ; par la volonté, il est entraîné à agir.

L’homme est envisagé

comme une union d’un corps et d’une âme. On constate chez la mystique allemande

une disposition positive vis-à-vis du corps, et elle réussit même à voir dans

la fragilité du corps une valeur providentielle : le corps n’est pas un

fardeau dont il faut se libérer, et même s’il est faible et fragile, il

« éduque » l’homme à l’humilité et à sa condition de créature en le

protégeant de l’orgueil et de l’arrogance. Dans un vision, Hildegarde voit les

âmes des bienheureux au Paradis, qui attendent d’être unis à nouveau à leur

corps. En effet, comme pour le corps du Christ, nos corps sont destinés, par

une transformation radicale, à la Résurrection glorieuse. La vision de Dieu, en

laquelle consiste la vie éternelle, ne peut être définitivement atteinte sans

le corps.

L’homme existe comme

homme et femme. Hildegarde reconnaît que dans cette structure ontologique de la

condition humaine s’enracinent une relation de complémentarité ainsi qu’une

égalité essentielle entre l’homme et la femme. Cependant, dans l’être de

l’homme habite aussi le mystère du péché, qui entre pour la première fois dans

l’histoire justement dans cette relation entre Adam et Ève. À l’inverse

d’autres auteurs médiévaux, qui voyaient la cause de la chute originelle dans

la faiblesse d’Ève, Hildegarde comprend cette chute avant tout comme une passion

immodérée d’Adam pour Ève.

Même dans son état de

pécheur, l’homme reste par la suite destiné à recevoir l’amour de Dieu, parce

que cet amour est sans conditions et revêt, après le péché originel, le visage

de la miséricorde. La peine elle-même, que Dieu impose à l’homme et la femme,

laisse poindre l’amour miséricordieux du Créateur. En ce sens, la description

la plus correcte de la créature est celle d’un être en chemin, d’un homo

viator. Dans ce pèlerinage vers la patrie céleste, l’homme est appelé à

combattre pour pouvoir sans cesse choisir le bien et éviter le mal.

Le choix continuel du

bien produit une existence vertueuse. Le Fils de Dieu fait homme est porteur de

toutes les vertus, c’est pourquoi l’imitation du Christ dans une vie vertueuse

consiste dans la communion avec le Christ. La force des vertus provient de l’Esprit-Saint,

répandu dans les cœurs des croyants : il rend possible une constante

disposition vertueuse. C’est le but de l’existence humaine. L’homme expérimente

de cette manière sa perfection christiforme.

6. Pour pouvoir

atteindre ce but, le Seigneur a donné les Sacrements à l’Église. Le Salut et la

perfection de l’homme ne s’atteignent pas en effet à la seule force de la

volonté, mais par un don gracieux, que Dieu accorde à son Église.

L’Église elle-même est le

premier sacrement, que Dieu place dans le monde afin de communiquer son Salut

aux hommes. Elle est « l’édifice d’âmes vivantes » et peut à bon

droit être considérée comme vierge, épouse et mère ; dès lors s’établit

une étroite comparaison avec la figure historique et mystique de la Mère de Dieu.

L’Église transmet le Salut avant tout par l’annonce des deux grands mystères de

la Trinité et de l’Incarnation, qui sont comme les « sacrements

premiers », ensuite par l’administration des autres sacrements. Le sommet

du caractère sacramentel de l’Église est l’eucharistie. Les sacrements

pourvoient à la sainteté des fidèles, au Salut et à la purification des

pécheurs, à la Rédemption, à l’amour et aux autres vertus. Mais l’Église vit

encore, parce que Dieu exprime en elle son amour intra-trinitaire. Le Seigneur

Jésus est le Médiateur par excellence. Du sein de la Trinité, il vient à la

rencontre des hommes, et du sein de Marie il vient à la rencontre de

Dieu : comme Fils de Dieu, il est l’amour fait chair ; en tant que

fils de Marie, il est le représentant de l’humanité devant le trône de Dieu.

Enfin, l’homme peut faire

même l’expérience de Dieu. La relation avec Lui ne s’épuise pas en effet dans

le seul domaine de la pensée rationnelle, mais intègre l’ensemble de la

personne. Tous les sens, intérieurs et extérieurs de Dieu, sont participants de

l’expérience de Dieu : « Homo autem ad imaginem et similitudinem Dei

factus est, ut quinque sensibus corporis sui opererur ; per quos etiam

divisus non est, sed per eos est sapiens et sciens et intelligens opera sua

adimplere. […] Sed et per hoc, quod homo sapiens, sciens et intellegens est,

creaturas conosci ; itaque per creaturas et per magna opera sua, quae

etiam quinque sensibus suis vix comprehendit, Deum cognoscit, quem nisi in fide

videre non valet » [« L’homme a été en effet créé à l’image et à la

ressemblance de Dieu, pour agir avec les cinq sens de son corps ; il n’est

pas divisé par eux, mais par eux il est sage, doué de science et

d’intelligence, pour réaliser ce qu’il doit faire. (…) Mais du fait que l’homme

est sage, doué de science et d’intelligence, il connaît les créatures ;

c’est pourquoi, par le biais des créatures et par les grandes œuvres qu’il

comprend aussi avec peine par ses cinq sens, il connaît Dieu, qu’on ne peut

voir que dans la foi »] (Explanatio Symboli Sancti Athanasii : PL

197, 1066). Cette voie faite d’expérience trouve son accomplissement de nouveau

dans la participation aux sacrements.

Hildegarde voit aussi les

contradictions présentes dans la vie des croyants et dénonce les situations les

plus blâmables. Elle souligne tout spécialement que l’individualisme dans

l’enseignement et la pratique aussi bien des laïcs que des personnes consacrées

est une expression d’orgueil et représente l’obstacle majeur à l’œuvre

d’évangélisation des non-chrétiens.

Un des sommets de

l’enseignement de Hildegarde est l’invitation claire à la vie vertueuse

adressée précisément à ceux qui vivent dans un état consacré. Sa compréhension

de la vie consacrée est une véritable « métaphysique théologique », parce

qu’elle s’enracine fortement dans la vertu théologale de foi, qui est la source

et la motivation constante pour s’engager totalement dans l’obéissance, la

pauvreté et la chasteté. Par la pratique des conseils évangéliques, la personne

consacrée partage l’expérience du Christ pauvre, chaste et obéissant, et suit

ses pas dans la vie quotidienne. C’est la caractéristique essentielle de la vie

consacrée.

7. L’enseignement

remarquable de Hildegarde reflète l’enseignement des apôtres, de la littérature

patristique et des œuvres d’auteurs de son époque, tandis qu’elle trouve dans

la Règle de St Benoît de Nursie un continuel point de référence. La

liturgie monastique et l’assimilation de la Sainte Écriture représentent les

lignes directrices de sa pensée, qui se concentre sur le mystère de

l’Incarnation et, en même temps, trouve son expression dans une profonde unité

stylistique, qui parcourt toutes ses œuvres.

L’enseignement de la

sainte bénédictine se présente comme un guide pour l’homo viator. Son message

apparaît extraordinairement actuel dans le monde d’aujourd’hui, qui est

particulièrement attiré par tout ce qu’elle a proposé et vécu. Nous pensons

spécialement à la capacité charismatique et spéculative de Hildegarde, qui se

présente comme un stimulant vivant pour la recherche théologique ; à sa

réflexion sur le mystère du Christ contemplé dans sa beauté ; au dialogue

de l’Église et de la théologie avec la culture, la science et les arts

contemporains ; à l’idéal de la vie consacrée comme possibilité de

réalisation humaine ; à la mise en valeur de la liturgie comme fête de la

vie ; à l’idée d’une réforme de l’Église, conçue non pas comme un changement

stérile des structures, mais comme une conversion du cœur ; à sa

sensibilité pour la nature, dont les lois sont à protéger et ne sauraient être

violées.

Dès lors, la

reconnaissance du titre de docteur de l’Église à Hildegarde de Bingen a une

grande signification pour le monde d’aujourd’hui, spécialement pour les femmes.

Chez Hildegarde s’expriment les valeurs féminines les plus nobles : c’est

pourquoi Hildegarde jette une lumière spéciale sur la présence des femmes dans

l’Église et la société, aussi bien du point de vue de la recherche scientifique

que de l’action pastorale. Sa capacité de parler à ceux qui se tiennent loin de

la foi et de l’Église fait de Hildegarde un témoin crédible de la nouvelle

évangélisation.

En raison de sa

réputation de sainteté et de son enseignement remarquable, le 6 mars 1979, le

cardinal Joseph Höffner, archevêque de Cologne et président de la conférence

épiscopale allemande, en accord avec les cardinaux, archevêques et évêques de

cette conférence, à laquelle nous aussi, alors cardinal et archevêque de Munich

et Freising, nous faisions partie, adressa au bienheureux Jean-Paul II la

Supplique suivante : que Hildegarde de Bingen puisse être déclarée docteur

de l’Église. Notre vénérable frère soulignait dans la Supplique l’orthodoxie de

l’enseignement de Hildegarde, reconnue au XIIe siècle par le pape Eugène

III, sa sainteté continuellement reconnue et célébrée par le peuple fidèle, la

valeur de ses traités. Au fil des années, d’autres Suppliques sont venues

s’ajouter à celle de la conférence épiscopale allemande, en premier lieu celle

des moniales du monastère d’Eibingen, placé sous le patronage de Hildegarde. À

la demande générale du Peuple de Dieu que Hildegarde soit déclarée sainte,

s’est donc ajoutée la demande de l’élever au rang de « docteur de l’Église

universelle ».

Avec notre accord, la

Congrégation pour la Cause des Saints a donc préparé avec attention une Positio

super Canonizatione et Concessione tituli Doctoris Ecclesiae universalis pour

la mystique de Bingen. Puisqu’il s’agit d’un maître éminent en théologie, à

laquelle ont été consacrées des études nombreuses et reconnues, nous avons

accordé la dispense de l’article 73 de la constitution apostolique Pastor

bonus. Le 20 mars 2012, ce cas a été examiné et unanimement approuvé par les

cardinaux et évêques lors d’une assemblée plénière, sous la présidence du

cardinal Angelo Amato, préfet de la Congrégation pour la Cause des Saints. Lors

de l’audience du 10 mai 2012, le cardinal Amato nous a lui-même informé en

détail du status quaestionis et du vote unanime des évêques lors de

l’assemblée plénière de la Congrégation pour la Cause des Saints évoquée

ci-dessus. Le 27 mai 2012, dimanche de Pentecôte, sur la place St Pierre, au

moment où commençait le synode des évêques et à la veille de « l’année de

la foi », nous avions la joie d’annoncer à la foule des pélerins venus du

monde entier la nouvelle de la reconnaissance du titre de docteur de l’Église à

Ste Hildegarde de Bingen et à St Jean d’Avila.

C’est ce qui est arrivé

aujourd’hui, avec l’aide de Dieu et l’approbation de l’ensemble de l’Église.

Sur la place St Pierre, en présence de nombreux cardinaux et évêques de la

Curie romaine et du monde entier, nous avons confirmé cette décision et comblé

ainsi les vœux des postulateurs en prononçant au cours de l’Eucharistie les

paroles suivantes :

« Nous, à la demande

de plusieurs frères dans l’épiscopat et de nombreux fidèles du monde, après

avoir reçu l’avis de la Congrégation pour la Cause des Saints, ayant longuement

réfléchi et en toute connaissance de cause, en vertu de l’autorité apostolique,

nous déclarons docteurs de l’Église St Jean d’Avila, prêtre diocésain, et Ste

Hildegarde de Bingen, moniale de l’Ordre de St Benoît. Au nom du Père et du

Fils et du Saint-Esprit. »

Nous le décidons et

l’ordonnons, en décrétant ces Lettres fermes, légitimes et efficaces, en

établissant qu’elles portent leur effet de façon pleine et entière et qu’on les

reçoive en conséquence. Nous décidons et décrétons par ailleurs qu’est nul et

non avenu tout changement conscient ou inconscient qui y serait porté, par qui

que ce soit ou en vertu de quelque autorité que ce soit.

Donné à Rome, près St

Pierre, muni du sceau du pêcheur, le 7 octobre 2012, en la huitième année de

mon pontificat.

Übersetzung aus dem

Lateinischen : P. Xavier Batllo OSB, Solesmes

SOURCE : http://www.abtei-st-hildegard.de/?p=3741

Portret

van Hildegard Hildegardis (titel op object) Historie der Kerken en ketteren

(..) tot aan het jaar onses Heeren 1688

Sainte Hildegarde de

Bingen : 4e femme docteur de l'Eglise

Maîtresse en théologie,

experte en sciences naturelles et en musique

27 mai 2012 |

Anne Kurian

ROME, dimanche 27 mai

2012 (ZENIT.org)

– Benoît XVI a annoncé qu’il proclamera sainte Hildegarde de Bingen (1089-1179)

docteur de l’Eglise, le 7 octobre 2012, en même temps que saint Jean d’Avila.

Le pape a fait cette

annonce avant la prière du Regina Coeli, qu’il présidait ce dimanche 27 mai,

place Saint-Pierre, à Rome.

Sainte Hildegarde sera la

quatrième femme à être proclamée docteur de l’Eglise, après sainte Catherine de

Sienne, sainte Thérèse d’Avila et sainte Thérèse de Lisieux.

« Je suis heureux d’annoncer

que le 7 octobre prochain, au commencement de l’Assemblée ordinaire du synode

des évêques, je proclamerai saint Jean d’Avila et sainte Hildegarde de Bingen

docteurs de l’Eglise universelle », a déclaré Benoît XVI sous les

applaudissements.

« Hildegarde, a

ajouté Benoît XVI, fut une moniale bénédictine au cœur de l’Allemagne

médiévale, authentique maîtresse en théologie et grande experte des sciences

naturelles et de la musique ».

Pour le pape, la

« sainteté de la vie et la profondeur de la doctrine » de Jean

d’Avila et Hildegarde les rendent « toujours actuels »: par

l’Esprit-Saint, ils sont témoins d’une « expérience de compréhension

pénétrante de la révélation divine » et d’un « dialogue intelligent

avec le monde ».

Ces deux expériences, a précisé

Benoît XVI, « constituent l’horizon permanent de la vie et de l’action de

l’Eglise ». C’est pourquoi « ces deux figures de saints et docteurs

sont d’une importance et d’une actualité majeures ».

Benoît XVI a récemment

étendu à toute l’Eglise le culte rendu à sainte Hildegarde (cf Zenit

du 10 mai 2012), reconnaissant ainsi la tradition multiséculaire qui avait

inscrit la mystique rhénane au martyrologe romain, sans même que son procès de

canonisation n’ait abouti. Sainte Hildegarde de Bingen est fêtée le 17

septembre.

Avec Hildegarde de Bingen

et Jean d’Avila, les docteurs de l’Eglise seront au nombre de 35.

(27 mai 2012) ©

Innovative Media Inc.

SOURCE : http://www.zenit.org/fr/articles/sainte-hildegarde-de-bingen-4e-femme-docteur-de-l-eglise

Stiftskirche

Kyllburg, Statuen auf der Brüstung der Orgelempore: St. Hildegard von Bingen

und Papst St. Gregor der Große

Qui était sainte

Hildegarde?

Qui était donc sainte

Hildegarde de Bingen, cette étonnante moniale fondatrice de monastères,

naturaliste, musicienne, peintre et visionnaire ? Mis à jour le 23 décembre

2015.

Dixième enfant d’une

famille noble de Bemersheim, en Rhénanie, Hildegarde reçoit, dès l’âge de trois

ans, des visions. Et cela durera soixante dix-huit ans ! C’est peut-être en

partie pour cette raison que ses parents la confient très tôt – à huit

ans – au couvent dépendant du monastère bénédictin de Disibodenberg, à

soixante kilomètres de là, tout près de Mayence. La mère supérieure du couvent,

Jutta de Sponheim, une amie de ses parents, veille à son instruction.

Hildegarde prononce ses vœux perpétuels au couvent et reçoit, vers l’âge de

quinze ans, le voile monastique des mains de son évêque. À la mort de Jutta de

Sponheim, Hildegarde a 38 ans. Elle est élue, par les sœurs du monastère,

abbesse du couvent. Toutes ces années lui ont permis de se former à la vie

monastique, rythmée par le travail, l’étude et la prière liturgique, et aussi

d’acquérir une érudition immense – même si elle se dit volontiers ignare.

Des visions

incandescentes

Au cours d’une vision, à

l’âge de 42 ans et sept mois (c’est elle qui précise !), Hildegarde reçoit de

Dieu l’ordre de rendre ses visions publiques. Écris ce que tu vois et ce que tu

entends ! Hildegarde doit vaincre de fortes résistances intérieures pour obéir

à l’ordre reçu. Elle raconte elle-même qu’il a fallu qu’elle tombe malade pour commencer

enfin, avec l’aide du moine Volmar qui écrit sous sa dictée, à composer son

premier livre, le Scivias(Connais les voies). Suivent alors dix années d’un

travail monumental traversées de beaucoup de doutes et d’hésitations.

Hildegarde va même jusqu’à solliciter l’avis du pape. Pour cela elle demande

son aide à Bernard de Clairvaux. En 1148, lors du grand synode de Trèves,

devant toute l’assemblée des cardinaux, des évêques et des prêtres réunis,

Eugène III prend un des écrits d’ Hildegarde, le lit à voix haute et conclut à

son adresse : «Écrivez donc ce que Dieu vous inspire».

Mais qu’y a-t-il donc

dans ce livre plein de lumières, de couleurs et de visions étranges ? En

réalité, Hildegarde retrace dans cet ouvrage l’histoire sainte depuis la

création du monde jusqu’à la rédemption finale en passant par l’Incarnation, la

crucifixion, la Résurrection et l’édification de l’Église. À chaque

chapitre, elle décrit la vision, l’interprète et lui donne son sens spirituel.

Elle le fait avec les codes de son temps – qui sont les codes bibliques –

enrichis par la lecture des Pères de l’Église. Elle y ajoute une vigueur et une

audace de style tout à fait étonnantes. On comprend que ces pages

incandescentes aient inspiré Dante Alighieri, lorsqu’il composa, deux siècles

plus tard, la Divine Comédie, le chef-d’œuvre de la langue italienne naissante.

Son couvent rayonne

Pendant toutes ces

années, le petit couvent féminin de Disbodenberg continue de vivre à l’ombre du

monastère bénédictin masculin dont il dépend. Pourtant, le couvent

rayonne, les vocations se multiplient et c’est lui, sans doute à cause du

rayonnement d’Hildegarde, qui attire les dons. Hildegarde, logiquement, veut

fonder sa propre abbaye. Le père abbé s’y oppose. Hildegarde tombe malade et

son état s’aggrave. Après quelque résistance, le père abbé laisse la supérieure

du petit couvent voler de ses propres ailes. Mais c’est l’indépendance

qu’elle veut, pas l’exil. Elle s’installe à quelques kilomètres de là, près de

Bingen, à Ruperstberg où elle terminera sa longue vie. Et lorsqu’il s’agira

pour elle, devant l’afflux des vocations, de fonder une autre abbaye, elle

n’ira pas non plus bien loin. Le monastère d’Eibingen, qu’elle ouvre environ

vingt ans plus tard, est lui aussi tout proche. Ainsi, celle dont les paroles

ont franchi les frontières du temps et de l’espace ne sortit pas, de son

vivant, d’un tout petit quadrilatère de quelques dizaines de kilomètres, au

cœur de la Rhénanie.

Mais Hildegarde n’est pas

seulement une visionnaire, c’est aussi une musicienne. Elle compose des pièces

liturgiques, 77 pour être exact, dont certaines sont aujourd’hui disponibles en

CD ! Car ces pièces sont parmi les premières à nous avoir été transmises

intégralement. Ainsi, le drame de l’Ordo Virtutum(L’Ordre des vertus), entièrement

composé par Hildegarde et mis en scène au monastère de Ruperstberg en 1152 par

les religieuses du couvent naissant, sera joué à Cologne en 1982, huit cents

ans plus tard.

Au centre de ses

recherches, l’Homme

Hildegarde n’a pas fini

de nous surprendre. Elle est femme de son temps, libre des préjugés que les

siècles suivants imposeront aux femmes. Elle dirige, commande, fonde, acquiert,

discute pied à pied avec les autorités religieuses et politiques. Mais surtout,

chose étonnante chez cette femme recluse et qui n’a pas quitté sa Rhénanie

natale, elle se met en route pour prêcher. Ainsi, de 1158 à 1170, elle prêche

en public à Mayence, Wurtzburg, Bamberg, Trèves et Cologne.

Mais surtout,

inlassablement, elle écrit. Selon l’ordre jadis reçu, elle consigne ses

visions. Le Livre des mérites de la vie l’occupe quatre ans, le Livre des

œuvres de Dieu, onze ans. Pendant cette époque, elle écrit une Physiqueet un

livre sur les causes des maladies et la manière de les soigner. Ce sont les

deux seuls ouvrages médicaux qui nous soient parvenus du XIIe siècle. Certains

y ont vu la partie émergée d’une science d’initiés. Mais il s’agit beaucoup

plus sûrement de faire droit, avec les connaissances du temps, au souci de

soigner l’homme global. Car c’est l’homme qui est au centre de la théologie d’

Hildegarde, l’homme-Dieu bien sûr, le Christ, mais qui rejoint à jamais l’homme

concret. Hildegarde a retranscrit ses visions dans de superbes enluminures au

symbolisme lumineux. Trois siècles avant Léonard de Vinci, elle représente dans

une de ses visions l’homme aux bras étendus situé au centre du cosmos. Il a été

créé libre. Il peut, à l’image de son créateur s’élever vers Lui.

Telle est sans doute la

leçon que l’on peut tirer de la vie de cette grande mystique aux multiples dons

et au destin hors du commun qui meurt à 81 ans dans son monastère de

Rupertsberg, entourée de ses sœurs et dont la renommée est si grande vers la