Saint

Margaret in a stained-glass window (1922) by Douglas

Strachan in St Margaret's Chapel, Edinburgh

Saint

Margaret in a stained-glass window (1922) by Douglas

Strachan in St Margaret's Chapel, Edinburgh

Sainte Marguerite

d'Ecosse

Reine d'Écosse (+ 1093)

Petite-fille du roi

d'Angleterre, elle se réfugia en Ecosse lors de l'invasion normande. Elle

deviendra l'épouse du roi Malcom III dont la piété était fort grande. Il

associait sa femme aux affaires du royaume et son règne durant quarante ans fut

des plus heureux : huit enfants dans un foyer très uni et un pays bien géré

malgré des luttes avec les envahisseurs normands. Elle meurt quelques jours

après l'assassinat de son époux par les Normands d'Angleterre. Elle introduisit

la liturgie romaine dans l'Eglise écossaise.

Elle était fêtée le 10

juin et maintenant le 16 novembre, date de sa mort le 16 novembre 1093.

Fêtée le 16 juin en

Ecosse.

Lire aussi (en anglais)

sa biographie sur le site de la paroisse Saint Margaret of Scotland à Chicago :

http://www.stmargaretofscotland.com/biography.htm

Mémoire de sainte

Marguerite d’Écosse. Née en Hongrie et mariée au roi d’Écosse Malcolm III, à

qui elle donna huit enfants, elle s’intéressa grandement au bien du royaume et

de l’Église, joignant à la prière et aux jeûnes la générosité envers les

pauvres et donnant ainsi un exemple excellent d’épouse, de mère et de reine.

Elle mourut en 1003 à Édimbourg, après avoir appris la nouvelle de la mort de

son mari et de son fils aîné dans une bataille.

Martyrologe romain

La main des pauvres est

l’assurance des trésors royaux. Ce coffre-fort, les cambrioleurs les plus

retors ne sauraient le forcer.

Prpos de sainte

Marguerite

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/9878/Sainte-Marguerite-d-Ecosse.html

Saint Margaret of Scotland in the Genealogical Chronicle of English kings.

SAINTE MARGUERITE

Reine d'Écosse

(1046-1093)

Sainte Marguerite était

nièce de saint Étienne de Hongrie. Elle vint au monde en 1046, et montra

bientôt de merveilleuses dispositions pour la vertu; la modestie rehaussait sa

rare beauté, et dès son enfance elle se signalait par son dévouement aux malheureux,

qui lui mérita dans la suite le nom de mère des orphelins et de trésorière des

pauvres de Jésus-Christ.

Forcée de chercher un

asile en Écosse, elle donna l'exemple d'une sainteté courageuse dans les

épreuves, si bien que le roi Malcolm III, plein d'estime pour elle et épris des

charmes de sa beauté, lui offrit sa main et son trône. Marguerite y consentit,

moins par inclination que dans l'espoir de servir à propager le règne de

Jésus-Christ. Elle avait alors environ vingt-trois ans (1070).

Son premier apostolat

s'exerça envers son mari, dont elle adoucit les moeurs par ses attentions

délicates, par sa patience et sa douceur. Convertir un roi, c'est convertir un

royaume: aussi l'Écosse entière se ressentit de la conversion de son roi: la

cour, le clergé, le peuple furent bientôt transformés.

Marguerite, apôtre de son

mari, fut aussi l'apôtre de sa famille. Dieu lui donna huit enfants, qui firent

tous honneur à la vertu de leur pieuse mère et à la valeur de leur père. Dès le

berceau elle leur inspirait l'amour de Dieu, le mépris des vanités terrestres

et l'horreur du péché.

L'amour des pauvres, qui

avait brillé dans Marguerite enfant, ne fit que s'accroître dans le coeur de la

reine: ce fut peut-être, de toutes les vertus de notre sainte, la plus remarquable.

Pour les soulager, elle n'employait pas seulement ses richesses, elle se

dépensait tout entière: "La main des pauvres, aimait-elle à dire, est la

garantie des trésors royaux: c'est un coffre-fort que les voleurs les plus

habiles ne sauraient forcer." Aussi se fit-elle plus pauvre que les

pauvres eux-mêmes qui lui tendaient la main; car elle ne se privait pas

seulement du superflu, mais du nécessaire, pour leur éviter des privations.

Quand elle sortait de son

palais, elle était toujours environnée de pauvres, de veuves et d'orphelins,

qui se pressaient sur ses pas. Avant de se mettre à table, elle servait

toujours de ses mains neuf petites orphelines et vingt-quatre vieillards; l'on

vit même parfois entrer ensemble dans le palais jusqu'à trois cents pauvres.

Malcolm se faisait un plaisir de s'associer à sa sainte épouse pour servir les

pauvres à genoux, par respect pour Notre-Seigneur, dont ils sont les membres

souffrants. La mort de Marguerite jeta le deuil dans tout le royaume.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/sainte_marguerite_reine_d_ecosse.html

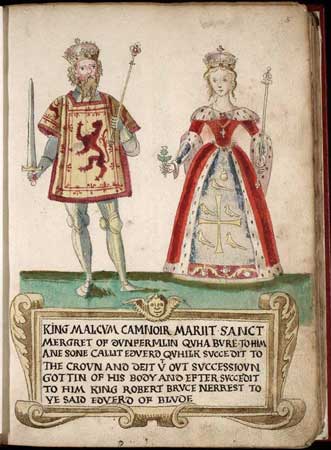

Malcolm and Margaret from the Forman Armorial,1562

Sainte Marguerite Reine d'Ecosse

Au martyrologe, on relève

vingt-et-une Marguerite (dont le nom signifie perle précieuse),

depuis la jeune martyre, décapitée à Antioche vers 303, jusqu'aux deux

religieuses guillotinées à Orange le 9 juillet 1794 : Marguerite de

Justaumont et Marguerite Charransol. La Margaret anglo-saxonne fêtée

aujourd’hui, arrive chronologiquement en seconde position, et mérita si bien

son prénom que l’introït de sa messe, la salue comme admirable par son

exquise charité envers les pauvres ; de plus, l'évangile (Matthieu XIII,

45-46) est la parabole de la perle précieuse.

Petite nièce du saint roi

Edouard le Confesseur1 , née vers 1045, Marguerite naquit

exilée en Hongrie où elle resta jusqu'à l'âge de neuf ans. Revenue en

Angleterre, elle dut fuir l'invasion normande (1066), et se réfugier en Ecosse

où elle fut accueillie par le roi Malcolm III2 qui l’épousa en 1070, au palais de

Dunfermline3. En vingt-trois ans de mariage, ce couple

exemplaire eut huit enfants : six garçons (Edouard, Ethelred, Edmond, Edgard4, Alexandre5, David6) et deux filles (Edith7 et Marie) dont deux auront l’honneur

des autels (David, roi d’Ecosse, et Edith, reine d'Angleterre).

Malcolm III était un rude

guerrier, peu lettré, bien qu'il parlât trois langues vivantes, mais

profondément amoureux et admiratif de sa femme qui, avec intuition et tact,

devint l’inspiratrice des réformes du royaume : plusieurs conciles nationaux où

la reine s’entretenait doctement avec les théologiens et les pontifes,

ramenèrent les Ecossais aux pratiques romaines ; rappel des commandements de

l'Eglise, spécialement la communion pascale et le repos dominical ; extirpation

des rites païens, fâcheusement mêlés au culte, surtout pendant la messe ;

proscription des mariages entre proches parents ; début du carême fixé au

mercredi des cendres ; fondation d'une abbaye locale sur le modèle de Cluny ;

construction d'une église dédiée à la Sainte Trinité.

Chaque matin de l'avent

et du carême, la souveraine lavait les pieds de six pauvres et soignait

personnellement neuf orphelins, puis, l'après-midi, avec le roi, elle servait

trois cents miséreux comme des hôtes privilégiés. Si le peuple les

surnommait la providence des pauvres gens, certains courtisans

craignaient la ruine des finances publiques ; la reine leur répondit :

« La main des pauvres, voilà bien la sûre et unique assurance des trésors

royaux. Ce coffre-fort, les voleurs les plus habiles ne parviendront jamais à

le forcer ! » Son ami et confesseur Thierri, son premier biographe

écrivit : « Malcolm apprend de son épouse comment passer une nuit

d'adoration. La ferveur du roi étonne. N'acquiert-il pas l'esprit de

componction et le don des larmes, signe extérieur de repentir !...

Constamment, la souveraine encourage son illustre époux aux œuvres de justice

et de miséricorde aussi bien qu'à la pratique de toutes vertus chrétiennes. »

La chambre de la reine

Marguerite était un véritable atelier tout rempli des ornements liturgiques

qu’elle confectionnait avec de précieux tissus qu’elle faisait importer

d’Italie. La nuit, après avoir pris quelque repos, elle se relevait pour prier,

récitait les matines de la Sainte-Trinité, à quoi elle ajoutait celles de la

Sainte-Croix ou celles de la Sainte-Vierge ; souvent, elle disait aussi

l’office des morts et lisait des psaumes avant que de dire des laudes. Au

matin, elle faisait quelques charités, entendait une ou plusieurs des messes

basses de ses chapelains, puis assistait à la messe solennelle.

« Elle gardait la

plus rigoureuse sobriété dans ses repas, ne mangeant qu’autant qu’il fallait

pour ne pas mourir, et fuyant tout ce qui aurait pu flatter la sensualité. Elle

paraissait plutôt goûter que manger ce qu’on lui présentait. En un mot , ses

œuvres étaient plus étonnantes que ses miracles : car le don d’en faire lui fut

aussi communiqué. Elle possédait l’esprit de componction dans un degré éminent.

Quand elle me parlait des douceurs ineffables de la vie éternelle, ses paroles

étaient accompagnées d’une grâce merveilleuse. Sa ferveur était si grande en

ces occasions, qu’elle ne pouvait arrêter les larmes abondantes qui coulaient

de ses yeux ; elle avait une telle tendresse de dévotion, qu’en la voyant, je

me sentais pénétré d’une vive componction. Personne ne gardait plus exactement

qu’elle le silence à l’église ; personne ne montrait un esprit plus attentif à

la prière. »

Réaliste et lucide,

Marguerite d’Ecosse établit la religion, la justice et la paix, pour le bonheur

de ses sujets, et ses contemporains lui rendirent un hommage unanime :

« Si, dans tout notre pays, des Higlandes au Cheviot Hills, elle fonde

églises, hospices et monastères, sa réalisation principale demeure celle du

bienfait. » Sous son impulsion, Malcolm fit bâtir la cathédrale de Durham,

fonda le monastère de la Trinité à Dunferline, et, avec l’accord du pape, créa

les évêchés de Murray et Carthneff qui s’ajoutèrent aux quatre évêchés

existants. Pour l'Ecosse, les vingt-et-une années de ce règne demeurent un âge

d'or venu, dirent les vieux hagiographes, de ce qu’« Une source pure donne

de belles eaux ; une sainte mère, une sainte reine, forment de belles

âmes. »

En 1093, Malcolm III

défendait l’Ecosse contre Guillaume le Roux8, fils de Guillaume le Conquérant,

quand, le 13 novembre, à Alnwick (Northumberland), il fut tué au combat, avec

son fils-aîné, comme la reine en eut le pressentiment : « Le jour même de

la mort du monarque, la reine apparaît triste et pensive. Elle confie à ses

suivantes : Aujourd'hui, ce 13 novembre, peut-être l'Ecosse est-elle

frappée d'un malheur si grand qu'elle n'en éprouva pas de semblable depuis de

longues années. Le quatrième jour (16 novembre), lors d'une accalmie

de santé car elle est malade depuis six mois, la souveraine se fait porter dans

son oratoire. De retour en ses appartements, la fièvre qui redouble et les

douleurs qui augmentent, l'obligent à s'aliter. Les chapelains recommandent son

âme à Dieu. Elle envoie chercher une croix. Marguerite embrasse délicatement le

crucifix et forme à plusieurs reprises, sur elle-même, le signe sacré du salut.

Ensuite, serrant la croix entre ses mains, la pieuse reine y fixe don regard et

récite le Miserere ... Sur ce, arrive du front son fils Edouard qui croit

prudent d'énoncer la pieuse restriction mentale : Malcolm se porte

bien ! La reine réplique doucement : Certes, il se porte si bien que

je vais vite le rejoindre là-haut. Et puis, tous les assistants, émus jusqu'aux

larmes, écoutent la dernière prière de la moribonde : Dieu tout-puissant,

merci de m'avoir envoyé si grande peine, à la fin de ma vie. Puisse-t-elle,

avec votre miséricorde, me purifier de mes péché ! Seigneur Jésus qui, par

votre mort, avez donné la vie au monde, délivrez-moi du mal ! Marguerite

expira. Il y avait dans sa mort tant de tranquillité, tant de paix,

qu’ on ne saurait douter que son âme ait été admise dans le séjour de

l’éternelle tranquillité, de la paix éternelle. Chose prodigieuse ! son visage

sur lequel la mort avait mis sa pâleur habituelle, reçut, après la mort même,

une teinte si pure et si parfaite de rose et de blanc, qu’on eût pas dit que la

reine était décédée, mais qu’elle dormait. »

On enterra la reine

Marguerite dans l’église de la Sainte-Trinité de Dunfermline, contre l’autel,

en face de la croix qu’elle avait plantée, où elle fut bientôt rejointe par son

époux. Le 21 septembre 1249, le pape accorda une indulgence à qui visiterait

l’église de Dunferline au jour de sa fête ; elle fut canonisée en 1251 par

Innocent IV. A l'époque de la réforme protestante (1538), ses restes

furent pieusement enlevés par les catholiques et transportés en Espagne où,

pour les accueillir, Philippe II édifia une chapelle à l'Escurial. En 1673, à la

demande instante du recteur de l'église romaine Saint-André des Ecossais,

Clément X, proclama Marguerite patronne de l'Ecosse. A ce titre,

ses clients, descendants des Pictes, des Scots et des Angles, vénèrent et

invoquent dans une même prière « le bon et pieux roi Malcolm, avec

son épouse, la charitable Marguerite qui, tous deux, jamais les pauvres

n'oublièrent. » Le chef de sainte Marguerite, donné à Marie Stuart, fut

sauvé par un bénédictin qui le porta à Anvers (1597) ; on le donna aux

jésuites écossais de Douai d’où il disparut à la Révolution.

1 Saint Edouard le

Confesseur, né en 1002 et mort en 1066, fut roi d’Angleterre de 1042 à 1066.

Guillaume le Conquérant et Harold II se disputèrent son héritage.

2 Malcolm

III Canmore, né vers 1031 et mort en 1093, fut roi d’Ecosse de 1058 à 1093.

3 Dunfermline était

une résidence royale où, en souvenir de son mariage, la reine Marguerite fit

construire une église en l'honneur de la Sainte-Trinité, et, selon toute

vraisemblance, y plaça trois moines envoyés de Cantorbéry par l'archevêque

Lanfranc (avant 1089). Les fils de Malcolm et de Marguerite poursuivirent

l'œuvre commencée : la grande nef romane, qui existe encore, fut

construite sous Alexandre I°, mais c'est sous David I° que la fondation prit

toute son ampleur : le roi obtint de Cantorbéry (1128) une nouvelle

colonie de moines avec un abbé. L'église abbatiale fut consacrée en 1150. Elle

fut longtemps, la nécropole des rois d'Écosse.

4 Edgard,

déposséda l’usurpateur Donald VIII (1093-1097) et fut roi d’Ecosse de 1097 à

1107.

5 Alexandre

I° le Farouche, fut roi d’Ecosse de 1107 à 1124.

6 Saint

David I°, né vers 1084 et mort en 1153, fut roi d’Ecosse de 1124 à 1153.

7 Sainte

Edith, dite Mathilde, épousa Henri I° d’Angleterre (1100) et mourut en

1118.

8 Guillaume

II le Roux, né en 1056, fut roi d’Angleterre de 1087 à 1100.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/11/16.php

Sainte Marguerite

d’Écosse, reine et veuve

Morte à Édimbourg en

1093. Canonisée avant 1249. Fête en 1693.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960

Quatrième leçon.

Marguerite, reine d’Écosse, qui avait la gloire de descendre des rois

d’Angleterre par son père, et des Césars par sa mère, devint plus illustre

encore par la pratique des vertus chrétiennes. Elle naquit en Hongrie, où son

père était alors exilé. Après avoir passé son enfance dans la plus grande

piété, elle vint en Angleterre avec son père qui était appelé par son oncle,

saint Édouard, roi des Anglais, à monter sur le trône de ses aïeux. Bientôt,

partageant les revers de sa famille, Marguerite quitta les rivages

d’Angleterre, mais une tempête, ou plus véritablement un dessein de la divine

Providence, la conduisit sur les côtes d’Écosse. Là, pour obéir à sa mère, elle

épousa le roi de ce pays, Malcolm III, qui avait été charmé par ses belles qualités,

et se rendit merveilleusement utile à tout le royaume par ses œuvres de

sainteté et de piété pendant les trente années qu’elle régna.

Cinquième leçon. Au

milieu des délices de la cour, elle affligeait son corps par des macérations,

des veilles, et réservait une grande partie de la nuit à ses pieuses oraisons.

Indépendamment des autres jeûnes qu’elle observait en diverses circonstances,

elle avait l’habitude de jeûner quarante jours entiers avant les fêtes de Noël,

et cela avec une telle rigueur, qu’elle persévérait à le faire malgré les plus

vives souffrances. Dévouée au culte divin, elle construisit à nouveau ou

restaura plusieurs églises et monastères, qu’elle enrichit d’objets précieux et

d’un revenu abondant. Par son très salutaire exemple, elle amena le roi son

époux à une conduite meilleure et à des œuvres semblables à celles qu’elle

pratiquait. Elle éleva ses enfants avec tant de piété et de succès, que

plusieurs d’entre eux embrassèrent, comme Agathe sa mère et Christine sa sœur,

le genre de vie le plus saint. Pleine de sollicitude pour la prospérité du

royaume entier, elle délivra le peuple de tous les vices qui s’y étaient

glissés insensiblement, et le ramena à des mœurs dignes de la foi chrétienne.

Sixième leçon. Rien

cependant ne fut plus admirable en elle que son ardente charité envers le

prochain et surtout à l’égard des indigents. Non contente d’en soutenir des

multitudes par ses aumônes, elle se faisait une fête de fournir tous les jours,

avec une bonté maternelle, le repas de trois cents d’entre eux, de remplir à

genoux l’office d’une servante envers ces pauvres, de leur laver les pieds de

ses mains royales, et de panser leurs plaies, n’hésitant même point à baiser

leurs ulcères. Pour ces générosités et autres dépenses, elle sacrifia ses

parures royales et ses joyaux précieux, et alla même plus d’une fois jusqu’à

épuiser le trésor. Enfin, après avoir enduré des peines très amères avec une

patience admirable et avoir été purifiée par six mois de souffrances

corporelles, elle rendit son âme à son Créateur le quatre des ides de juin. Au

même instant, son visage défiguré pendant sa longue maladie par la pâleur et la

maigreur, s’épanouit avec une beauté extraordinaire. Marguerite fut illustre,

même après sa mort, par des prodiges éclatants. L’autorité de Clément X l’a

donnée pour patronne à l’Écosse ; et elle est dans le monde entier très

religieusement honorée.

Bleiglasfenster in der katholischen Pfarrkirche Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Sceaux im Département Hauts-de-Seine in der Île-de-France, Darstellung: hl. Margareta von Schottland

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Une semaine s’est écoulée

depuis le jour où, s’élevant de la terre de France dédiée au Christ par ses

soins, Clotilde apprenait au monde le rôle réservé à la femme près du berceau

des peuples. Avant le christianisme, l’homme, amoindri par le péché dans sa

personne et dans sa vie sociale, ne connaissait pas la grandeur en ce point des

intentions divines ; la philosophie et l’histoire ignoraient l’une et l’autre

que la maternité pût s’élever jusqu’à ces hauteurs. Mais l’Esprit-Saint, donné

aux hommes pour les instruire de toute vérité [1], théoriquement et

pratiquement, multiplie depuis sa venue les exemples, afin de nous révéler

l’ampleur merveilleuse du plan divin, la force et la suavité présidant ici

comme partout aux conseils de l’éternelle Sagesse.

L’Écosse était chrétienne

depuis longtemps déjà, lorsque Marguerite lui fut donnée, non pour l’amener au

baptême, mais pour établir parmi ses peuplades diverses et trop souvent

ennemies l’unité qui fait la nation. L’ancienne Calédonie, défendue par ses

lacs, ses montagnes et ses fleuves, avait jusqu’à la fin de l’empire romain

gardé son indépendance. Mais, inaccessible aux armées, elle était devenue le

refuge des vaincus de toute race, des proscrits de toutes les époques. Les

irruptions, qui s’arrêtaient à ses frontières, avaient été nombreuses et sans

merci dans les provinces méridionales de la grande île britannique ; Bretons

dépossédés, Saxons, Danois, envahisseurs chassés à leur tour et fuyant vers le

nord, étaient venus successivement juxtaposer leurs mœurs à celles des premiers

habitants, ajouter leurs rancunes mutuelles aux vieilles divisions des Pictes

et des Scots. Mais du mal même le remède devait sortir. Dieu, pour montrer

qu’il est le maître des révolutions aussi bien que des flots en furie, allait

confier l’exécution de ses desseins miséricordieux sur l’Écosse aux

bouleversements politiques et à la tempête.

Dans les premières années

du XIe siècle, l’invasion danoise chassait du sol anglais les fils du dernier

roi saxon, Edmond Côte de fer. L’apôtre couronné de la Hongrie, saint Etienne

Ier, recevait à sa cour les petits-neveux d’Édouard le Martyr et donnait à

l’aîné sa fille en mariage, tandis que le second s’alliait à la nièce de

l’empereur saint Henri, le virginal époux de sainte Cunégonde. De cette

dernière union naquirent deux filles : Christine qui se voua plus tard au

Seigneur, Marguerite dont l’Église célèbre la gloire en ce jour, et un prince,

Edgard Etheling, que les événements ramenèrent bientôt sur les marches du trône

d’Angleterre. La royauté venait en effet de passer des princes danois à Édouard

le Confesseur, oncle d’Edgard ; et l’angélique union du saint roi avec la douce

Édith n’étant appelée à produire de fruits que pour le ciel, la couronne

semblait devoir appartenir après lui par droit de naissance au frère de sainte

Marguerite, son plus proche héritier. Nés dans l’exil, Edgard et ses sœurs

virent donc enfin s’ouvrir pour eux la patrie. Mais peu après, la mort

d’Édouard et la conquête normande bannissaient de nouveau la famille royale ;

le navire qui devait reconduire sur le continent les augustes fugitifs était

jeté par un ouragan sur les côtes d’Écosse. Edgard Etheling, malgré les efforts

du parti saxon, ne devait jamais relever le trône de ses pères ; mais sa sainte

sœur conquérait la terre où le naufrage, instrument de Dieu, l’avait portée.

Devenue l’épouse de

Malcolm III, sa sereine influence assouplit les instincts farouches du fils de

Duncan, et triompha de la barbarie trop dominante encore en ces contrées

jusque-là séparées du reste du monde. Les habitants des hautes et des basses

terres, réconciliés, suivaient leur douce souveraine dans les sentiers nouveaux

qu’elle ouvrait devant eux à la lumière de l’Évangile. Les puissants se

rapprochèrent du faible et du pauvre, et, déposant leur dureté de race, se

laissèrent prendre aux charmes de la charité. La pénitence chrétienne reprit

ses droits sur les instincts grossiers de la pure nature. La pratique des

sacrements, remise en honneur, produisait ses fruits. Partout, dans l’Église et

l’État, disparaissaient les abus. Tout le royaume n’était plus qu’une famille,

dont Marguerite se disait à bon droit la mère ; car l’Écosse naissait par elle

à la vraie civilisation. David Ier, inscrit comme sa mère au catalogue des

Saints, achèvera l’œuvre commencée ; pendant ce temps, un autre enfant de

Marguerite, également digne d’elle, sainte Mathilde d’Écosse, épouse d’Henri

Ier fils de Guillaume de Normandie, mettra fin sur le sol anglais aux rivalités

persévérantes des conquérants et des vaincus par le mélange du sang des deux

races.

Nous vous saluons, ô

reine, digne des éloges que la postérité consacre aux plus illustres

souveraines. Dans vos mains, la puissance a été l’instrument du salut des

peuples. Votre passage a marqué pour l’Écosse le plein midi de la vraie

lumière. Hier, en son Martyrologe, la sainte Église nous rappelait la mémoire

de celui qui fut votre précurseur glorieux sur cette terre lointaine : au VIe

siècle, Colomb-Kil, sortant de l’Irlande, y portait la foi. Mais le

christianisme de ses habitants, comprimé par mille causes diverses dans son

essor, n’avait point produit parmi eux tous ses effets civilisateurs. Une mère

seule pouvait parfaire l’éducation surnaturelle de la nation. L’Esprit-Saint,

qui vous avait choisie pour cette tâche, ô Marguerite, prépara votre maternité

dans la tribulation et l’angoisse : ainsi avait-il procédé pour Clotilde ;

ainsi fait-il pour toutes les mères. Combien mystérieuses et cachées

n’apparaissent pas en votre personne les voies de l’éternelle Sagesse ! Cette

naissance de proscrite loin du sol des aïeux, cette rentrée dans la patrie,

suivie bientôt d’infortunes plus poignantes, cette tempête, enfin, qui vous

jette dénuée de tout sur les rochers d’une terre inconnue : quel prudent de ce

monde eût pressenti, dans une série de désastres pareils, la conduite d’une

miséricordieuse providence faisant servir à ses plus suaves résolutions la

violence combinée des hommes et des éléments ? Et pourtant, c’est ainsi que se

formait en vous la femme forte [2], supérieure aux tromperies de la vie

présente et fixée en Dieu, le seul bien que n’atteignent pas les révolutions de

ce monde.

Loin de s’aigrir ou de se

dessécher sous la souffrance, votre cœur, établi au-dessus des variations de

cette terre à la vraie source de l’amour, y puisait toutes les prévoyances et

tous les dévouements qui, sans autre préparation, vous tenaient à la hauteur de

la mission qui devait être la vôtre. Ainsi fûtes-vous en toute vérité ce trésor

qui mérite qu’on l’aille chercher jusqu’aux extrémités du monde, ce navire qui

apporte des plages lointaines la nourriture et toutes les richesses au rivage

où les vents l’ont poussé [3]. Heureuse votre patrie d’adoption, si jamais elle

n’eût oublié vos enseignements et vos exemples ! Heureux vos descendants, si

toujours ils s’étaient souvenus que le sang des Saints coulait dans leurs

veines ! Digne de vous dans la mort, la dernière reine d’Écosse porta du moins

sous la hache du bourreau une tête jusqu’au bout fidèle à son baptême. Mais on

vit l’indigne fils de Marie Smart, par une politique aussi fausse que

sacrilège, abandonner en même temps l’Église et sa mère. L’hérésie desséchait

pour jamais la souche illustre d’où sortirent tant de rois, au moment où

l’Angleterre et l’Écosse s’unissaient sous leur sceptre agrandi ; car la

trahison consommée par Jacques Ier ne devait pas être rachetée devant Dieu par

la fidélité de Jacques II à la foi de ses pères. O Marguerite, du ciel où votre

trône est affermi pour les siècles sans fin, n’abandonnez ni l’Angleterre à qui

vous appartenez par vos glorieux ancêtres, ni l’Écosse dont la protection

spéciale vous reste confiée par l’Église de la terre. L’apôtre André partage

avec vous les droits de ce puissant patronage. De concert avec lui, gardez les

âmes restées fidèles, multipliez le nombre des retours à l’antique foi, et

préparez pour un avenir prochain la rentrée du troupeau tout entier sous la

houlette de l’unique Pasteur [4].

[1] Johan. XVI, 13.

[2] Prov. XXXI, 10-31.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Johan. X, 16.

St Margaret of Scotland, Scottish Episcopal Church, Aberdeen

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Cette sainte reine

confirme ce qu’écrivait jadis saint Paul : Une femme remplie de foi peut

sanctifier son mari et toute sa maison. Marguerite fut l’ange tutélaire de son

peuple, c’est pourquoi Clément X la proclama patronne de l’Écosse.

La messe est semblable à

celle de sainte Françoise Romaine, le 9 mars. Seule la première collecte est

spéciale : « Seigneur qui avez inspiré à la bienheureuse reine Marguerite un

tendre amour pour les pauvres ; à son exemple et par ses prières, faites que la

charité embrase de plus en plus notre cœur ».

Il est meilleur de donner

que de recevoir, a dit le Seigneur (Act., XX, 35). Dieu a imprimé sur les

puissants et sur les riches comme un rayon de sa magnificence, afin que

ceux-ci, partageant entre les malheureux les ressources qu’il leur a accordées,

soient les organes et les ministres de la divine Providence. La richesse est

donc une mission sacrée et divine, et c’est la raison pour laquelle Dieu nous

déclare si souvent dans la sainte Écriture qu’il a lui-même créé le riche comme

le pauvre.

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

Que Dieu donne de bonnes

mères !

Sainte Marguerite. Jour

de mort : 10 juin 1093. Tombeau : La plus grande partie des reliques se trouve

au couvent de l’Escurial, en Espagne. Image : On la représente en reine,

secourant les pauvres. « Elle naquit en Hongrie (vers 1045) où son père était alors

exilé. Elle y passa son enfance dans une profonde piété. Elle vint plus tard en

Angleterre. Son père avait, en effet, été élevé par son oncle, le saint roi

Édouard III d’Angleterre, aux plus hautes dignités du royaume. Après la mort

subite de son père, en 1057, elle quitta l’Angleterre. Une violente tempête, ou

plutôt une disposition spéciale de la Providence, la jeta sur les côtes

écossaises. Là, elle épousa, sur l’ordre de sa mère, le roi d’Écosse, Malcolm

III (1070). Sa sainteté et sa charité en firent pendant ses trente ans de règne

la bénédiction du pays. Au sein même des grandeurs royales, Marguerite

mortifiait sa chair par des austérités et des veilles. Ce qui était surtout

admirable dans cette sainte reine, c’était sa charité pour le prochain et particulièrement

pour les nécessiteux. Elle ne se contentait pas de secourir les nombreux

nécessiteux par des aumônes ; elle nourrissait encore chaque jour à sa table

environ 300 pauvres, elle les servait de sa propre main et baisait leurs plaies

». Elle a été déclarée patronne du royaume d’Écosse.

Encore deux traits de sa

vie : La reine insistait souvent auprès de son confesseur pour qu’il lui

indiquât sans pitié tous ses défauts. Elle fit convoquer plusieurs synodes et

manifesta beaucoup de zèle pour faire observer les commandements de l’Église.

Pratique. — L’oraison de

la fête fait ressortir « son amour pour les pauvres » et demande que, « par son

intercession et son exemple, l’amour de Dieu grandisse chaque jour dans nos

cœurs ». La charité doit toujours être cultivée avec un soin particulier. « Ce

que vous aurez fait au plus petit d’entre les miens, c’est à moi que vous

l’aurez fait », dit le Seigneur. — La messe est du commun des saintes femmes

(Cognóvi).

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/10-06-Ste-Marguerite-d-Ecosse

Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746), Queen St Margaret, Queen of Scotland (1045/6–1093), circa 1692, 135 x 103, National Trust

Also

known as

Margaret of Wessex

formerly 10 June

Profile

Granddaughter of King Edmund

Ironside of England.

Great-niece of Saint Stephen

of Hungary. Born in Hungary while

her family was in exile due

to the Danish invasion

of England,

she still spent much of her youth in the British Isles. While fleeing the

invading army of

William the Conqueror in 1066,

her family’s ship wrecked on

the Scottish coast.

They were assisted by King Malcolm

III Canmore of Scotland,

whom Margaret married in 1070. Queen of Scotland.

They had eight children including Saint Maud, wife of

Henry I, and Saint David

of Scotland and Blessed Edmund

of Scotland. Margaret founded abbeys and

used her position to work for justice and improved conditions for the poor.

Born

16

November 1093 at

Edinburgh Castle, Scotland,

four days after her husband and son died in

defense of the castle

buried in

front of the high altar at Dunfermline, Scotland

relics later

removed to a nearby shrine

the bulk of her relics were

destroyed in stages during the Protestant Reformation and the French

Revolution

1251 by Pope Innocent

IV

–

–

in Scotland

queen dispensing gifts to

the poor,

often while carrying a black cross

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Mothers

of History, by J T Moran, C.SS.R.

Our

Island Saints, by Amy Steedman

Panegyric

on Saint Margaret, by James Augustine Stothert

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

The

Book of Saints and Heroes, by Leonora Blanche Lang

The Life and Times of

Saint Margaret, Queen and Patroness of Scotland, by A Secular Priest

books

Favourite Patron Saints, by Paul Burns

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

other

sites in english

Christian

Biographies, by James Keifer

How Saint Margaret Came to Scotland, by Malcolm Canmore

Life

and Times of Saint Margaret, Queen and Patroness of Scotland

images

video

The Life and Times of Saint Margaret, Queen and Patron of

Scotland (Librivox audiobook with image montage)

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

strony

w jezyku polskim

Conference

of the Polish Espiscopate

Saint Margaret of Scotland, by Peter Drzyzga

Strong

Scottish Patron, by Father Tomasz Jaklewicz

MLA

Citation

“Saint Margaret of

Scotland“. CatholicSaints.Info. 11 February 2024. Web. 11 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-margaret-of-scotland/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-margaret-of-scotland/

St Margaret of Scotland. The sixth north nave window of St Mark's Church, Staplefield, West Sussex. It was designed by Joseph E Nuttgens and produced by James Powell and Sons in 1924.

Book of Saints

– Margaret of Scotland

(Saint)

(June

10) Queen, Widow. (11th

century) The grand-daughter of King Edmond Ironside, sister of Edgar

Atheling, and through her mother related to Saint Stephen, King of Hungary. In

exile during the Danish domination in England, Saint Margaret with the rest of

the Royal Family lived in England during the reign of Saint Edward the

Confessor. After the death of the latter, Saint Margaret’s mother, a Hungarian

princess, was compelled to seek refuge for her children and herself on the

Continent from the Normans, who had become masters of England. A storm drove

the ship on which she had embarked on to the coast of Scotland. They were

welcomed by King Malcolm III, who made Margaret his Queen. The Saint used her

influence as Queen for the good of religion and for the promotion of justice.

She had especial thought for the poor, nor would suffer any to be oppressed.

Among the pious foundations she made was the Abbey of Dunfermline. In her

private life she was devoted to prayer. The Book of the Gospels she studied is

still preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. She foretold the day of her

death, which occurred November 16, A.D. 1093, on which day her festival is

still celebrated in Scotland, though in other countries, by Papal Decree, kept

on June 10.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Margaret of Scotland”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

24 November 2014. Web. 11 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-margaret-of-scotland/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-margaret-of-scotland/

Statue of Queen Margaret, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Statue of Queen Margaret, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Pictorial

Lives of the Saints – Saint Margaret of Scotland

Article

Saint Margaret’s name

signifies “pearl;” “a fitting name,” says Theodoric, her confessor and her

first biographer, “for one such as she.” Her soul was like a precious pearl. A

life spent amidst the luxury of a royal court never dimmed its lustre, or stole

it away from Him who had bought it with His blood. She was the granddaughter of

an English king; and in 1070 she became the bride of Malcolm, and reigned Queen

of Scotland till her death in 1093. How did she become a Saint in a position

where sanctity is so difficult? First, she burned with zeal for the house of

God. She built churches and monasteries; she busied herself in making

vestments; she could not rest till she saw the laws of God and His Church

observed throughout her realm. Next, amidst a thousand cares, she found time to

converse with God—ordering her piety with such sweetness and discretion that

she won her husband to sanctity like her own. He used to rise with her at night

for prayer; he loved to kiss the holy books she used, and sometimes he would

steal them away, and bring them back to his wife covered with jewels. Lastly,

with virtues so great, she wept constantly over her sins, and begged her

confessor to correct her faults. Saint Margaret did not neglect her duties in

the world because she was not of it. Never was a better mother. She spared no

pains in the education of her eight children, and their sanctity was the fruit

of her prudence and her zeal. Never was a better queen. She was the most

trusted counsellor of her husband, and she labored for the material improvement

of the country. But, in the midst of the world’s pleasures, she sighed for the

better country, and accepted death as a release. On her deathbed she received

the news that her husband and her eldest son were slain in battle. She thanked

God, who had sent this last affliction as a penance for her sins. After

receiving Holy Viaticum, she was repeating the prayer from the Missal, “O Lord

Jesus Christ, who by Thy death didst give life to the world, deliver me.” At

the words “deliver me,” says her biographer, she took her departure to Christ,

the Author of true liberty.

Reflection – All

perfection consists in keeping a guard upon the heart. Wherever we are, we can

make a solitude in our hearts, detach ourselves from the world, and converse

familiarly with God. Let us take Saint Margaret for our example and

encouragement.

MLA

Citation

John Dawson Gilmary Shea.

“Saint Margaret of Scotland”. Pictorial Lives of

the Saints, 1889. CatholicSaints.Info.

24 May 2014. Web. 11 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-margaret-of-scotland/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-margaret-of-scotland/

Santa Margarita reina de Escocia. Obra de Juan de Roelas, c. 1605. Iglesia de

San Miguel and San Julián, Valladolid.

St. Margaret of Scotland

Born about 1045, died 16

Nov., 1093, was a daughter of Edward "Outremere", or "the

Exile", by Agatha, kinswoman of Gisela, the wife of St.

Stephen of Hungary. She was the granddaughter of Edmund Ironside. A

constant tradition asserts that Margaret's father and his brother Edmund were

sent to Hungary for

safety during the reign of Canute,

but no record of the fact has been found in that country. The date of

Margaret's birth cannot be ascertained with accuracy, but it must have been

between the years 1038, when St.

Stephendied, and 1057, when her father returned to England.

It appears that Margaret came with him on that occasion and, on his death and

the conquest of England by

the Normans, her mother Agatha decided to return to the Continent. A storm

however drove their ship to Scotland,

where Malcolm III received the party under his protection, subsequently taking

Margaret to wife. This event had been delayed for a while by Margaret's desire

to enter religion, but it took place some time between

1067 and 1070.

In her position as queen,

all Margaret's great influence was thrown into the cause

of religion and piety.

Asynod was

held, and among the special reforms instituted the most important were the

regulation of theLenten

fast, observance of the Easter communion,

and the removal of certain abuses concerning marriage

within the prohibited degrees. Her private life was given up to

constant prayer and

practices of piety.

She founded several churches, including the Abbey

of Dunfermline, built to enshrine her greatest treasure, a relicof

the true

Cross. Her book of the Gospels,

richly adorned with jewels, which one day dropped into a river and was

according to legend miraculously recovered,

is now in the Bodleian library at Oxford.

She foretold the day of her death, which took place at Edinburgh on

16 Nov., 1093, her body being buried before

the high

altar at Dunfermline.

In 1250 Margaret

was canonized by Innocent

IV, and her relics were

translated on 19 June, 1259, to a new shrine, the base of which is still

visible beyond the modern east wall of the restored church. At theReformation her

head passed into the possession of Mary

Queen of Scots, and later was secured by theJesuits at Douai,

where it is believed to

have perished during the French

Revolution. According to George Conn, "De duplici statu religionis

apud Scots" (Rome, 1628), the rest of the relics,

together with those of Malcolm, were acquired by Philip

II of Spain, and placed in two urns in the Escorial.

When, however, Bishop

Gillies of Edinburgh applied

through Pius

IX for their restoration to Scotland,

they could not be found.

The chief authority for

Margaret's life is the contemporary biography printed in "Acta SS.",

II, June, 320. Its authorship has been ascribed to Turgot,

the saint's confessor,

a monk of Durham and

later Archbishop of St.

Andrews, and also to Theodoric, a somewhat obscure monk;

but in spite of much controversy the point remains quite unsettled. The feast of St.

Margaret is now observed by the whole Church on

10 June.

Sources

Acta SS., II, June, 320;

CAPGRAVE, Nova Legenda Angliae (London, 1515), 225; WILLIAM OF

MALMESBURY, Gesta Regum in P.L., CLXXIX, also in Rolls Series,

ed. STUBBS (London, 1887-9); CHALLONER, Britannia Sancta, I (London,

1745), 358; BUTLER, Lives of the Saints, 10 June; STANTON, Menology

of England and Wales (London, 1887), 544; FORBES-LEITH, Life of St.

Margaret. . . (London, 1885); MADAN, The Evangelistarium of St. Margaret

in Academy (1887); BELLESHEIM, History of the Catholic Church in

Scotland, tr. Blair, III (Edinburgh, 1890), 241-63.

Huddleston,

Gilbert. "St. Margaret of Scotland." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company,1910. 9

Jun. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09655c.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Anita G. Gorman.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09655c.htm

Edward

Burne-Jones (1833, Birmingham - 1898, Fulham). Sainte Marguerite, 1894

Carton de vitrail réalisé par la firme W. Morris, pour l'Eglise

Sainte-Marguerite de Rottingdean (Grande-Bretagne) Craies de couleur sur papier

marouflé sur toile 214 x 61 cm H.G.: Rotting Dean.St.Margaret's Ch. two light

window right hand light.S.Margareth. Achat à Georges Martin du Nord

(Paris) en 1968 Musée d'Art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg. Inv. :

2326

St. Margaret Queen of

Scotland (1047-1093)

Queen Margaret of

Scotland was by birth an English Princess, grand-daughter of Edmund Ironside.

When Edmund died and the English people chose Cnut to be their king, Edmund’s

infant sons were sent abroad to the protection of King Stephen of Hungary. One

of the twins died young, but the other, Edward Atheling, was brought up as a

protégé of Stephen’s Queen, Gisela, and regarded in that foreign Court as the

heir to the Anglo-Saxon throne. He married a cousin of Gisela, the Princess

Agatha. Their marriage was blessed by one son, Edgar, and two daughters,

Christian and Margaret.

Much has been written

about the significance of the name, Margaret. It came originally from the

Greek, margaron, meaning pearl. For that reason Margaret was sometimes called

“The Pearl of Scotland,” to which her biographer, Turgot, comments, “the

fairness pre-shadowed in her name was eclipsed in the surpassing grace of her

soul.”

When Cnut died in 1035,

his sons Harold and Harthacnut reigned for seven years. Then the English

determined they must have a king of their own blood, thus paving the way for

Edward (afterwards the Confessor) to be chosen. He, too, was an exile, brought

up in Normandy under Benedictine influences. Never attracted by worldly things,

his palace was more monastery than court. He himself was a virtuous man who

protected the kingdom by means of peace rather than violence. The ruling of an

earthly kingdom, however, was of little interest to him. Having vowed to live

in virginity, he resolved to bring Edward the Exile and his family back from

Hungary in order to secure the succession to the throne of England.

Edward, his wife and

three children set out from Hungary in 1054, but whether from natural or

sinister causes, Edward died immediately on landing. His widow and three

children found themselves again living in dependence at court. Now, however,

they were in a position of importance, Edgar being the heir to the throne.

Margaret was about ten

years old when she came to England. The impression seems to have been that she

was a tall, handsome girl of Saxon type, but the early chronicles were so busy

describing the beauty of her nature that they say little about her appearance.

We know that she read the Scriptures in Latin, and it is almost certain that

she was familiar with the writings of St. Augustine.

During some of these

years another prince enjoyed the hospitality of Edward the Confessor. When his

father, Duncan, was murdered by Macbeth, Malcolm III of Scotland was sent for

safety to the English Court. There he met Margaret, his future wife and Queen.

When Edward the Confessor

died, the only direct heirs to the throne of England were Edgar, Margaret, and

Christian. According to the law of the land, however, they had no

constitutional claim to the throne: Edgar not having been born in England and

not being the son of the crowned king, and a princess not being eligible (at

that time) to reign in her own right. And so, the people unanimously chose

Harold, son of Earl Godwine, to be their king. But William of Normandy,

England’s rival across the water, was only biding his time until all his

preparations were made. Then, at the Battle of Hastings, Harold was killed.

Upon Harold’s death,

Edgar was halfheartedly chosen king (he was a very weak character), but was

never crowned. Edgar’s supporters soon saw they had no chance against the

well-equipped Norman forces, and so Edgar and the leaders of Church and State

waited at Berkhampstead to offer William the Conqueror homage. Seeing the

affairs of the English disturbed on every side, and fearing retaliation by his

conqueror, the royal family resolved to return to Hungary. They took ship, but

a fierce gale drove them northwards forcing their vessel to take shelter in the

Firth of Forth. The royal travelers landed in a sheltered bay on the Fifeshire

coast, since called St. Margaret’s Hope, where Malcolm, now King of Scotland,

hastened to welcome the friends he had known in England.

Margaret was about twenty

years old. She would find a primitive style of life at Dunfermline, where the

royal residence was located. It was a time of great poverty in Scotland and

though the people were nominally Christian, Church life was at a low ebb.

Malcolm was then about

forty years old, a widower with one son. He was deeply attracted to Margaret,

whose own inclination and upbringing had prepared her for the cloister rather

than the throne. It was only after long consideration, yielding to her friends

and advisors, that Margaret was married in 1070 at age twenty-four to the King

of Scotland. Through the influence she acquired over her husband, she softened

her husband’s temper, polished his manners, and rendered him one of the most

virtuous kings who have ever occupied the Scottish throne.

What she did for her

husband, Margaret also did in a great measure for her adopted country. Though a

contemplative by nature, she lived the ordered life of prayer and work taught

by St. Benedict, combining the virtues of Martha and Mary in an exemplary

fashion. Through her tireless efforts, she reformed both the spiritual and

social milieu in Scotland, supported in these endeavors by her devoted husband.

She promoted education and religion, made it her constant effort to obtain good

priests and teachers for all parts of the country, founded several churches,

built hospitals, and cared for the poor. Despite her royal position, she

regarded herself merely as the steward of God’s riches, living in the spirit of

inward poverty, looking on nothing as her own, but recognizing that everything

she possessed was to be used for the purposes of God. The miracle is that the

Scots, ever jealous of their liberties, accepted the reforms she introduced!

Her charity was unbounded.

She thought of her poorest subjects before herself, often feeding orphans,

taking in the homeless, and performing other acts of charity. Tradition says

that Margaret used to sit on a stone outside the castle so that anyone in

trouble might come to her. Another tradition describes a daily custom at

Dunfermline in which any destitute poor could come in the morning to the royal

hall where the King and Queen themselves would serve provide for their needs.

She also had great compassion on the English captives in Scotland, often paying

their ransoms and setting them free.

Such a life could not

fail to be a power for good, and for centuries Margaret was honored as the

ideal of a holy woman who lived in the world. She was a reformer of life and

religion rather than the institutional Church. In the process, she improved the

standard of living in Scotland and revived the religious life of the people.

Margaret had eight

children, six sons and two daughters. Of the sons, Edward, the eldest, was

killed in battle, Ethelred died young, and Edmund “fell away from the good.”

But the three youngest sons were the jewels in the crown: Edgar, Alexander, and

David are remembered among the best kings Scotland ever had.

It is an interesting fact

that of all the saints canonized by the Church of Rome, Margaret stands alone

as the happy mother of a large family. It is that image which we use as our

parish logo.

Towards the end of her

life she and King Malcolm lived in the Castle of Edinburgh, none of which

remains with the exception of her little chapel, pictured on the opposite page

of this article. It was here that she died, a few days after she heard that her

husband and eldest son had been killed in battle. Margaret was not yet fifty

when she died.

Though Margaret’s achievements

were great, her selfless spirit in which she achieved them was greater still,

for the height of perfection and blessedness does not consist in the

performance of wonderful works but in the purity of love.

Margaret was canonized in

1250, and was named Patroness of Scotland in 1673. Her feast day had been June

10th, but is presently celebrated on November 16th.

(...)

SOURCE : http://saintmargaret.com/pages/stmargaret.htm

Holy Trinity Church in Crockham Hill : Stained glass window of Saint Margaret of Scotland and Saint Cecilia.

Calendar

of Scottish Saints – Saint Margaret, Queen

A.D. 1093. It is

impossible here to say much in detail of the life of the saintly queen who is

regarded as one of the heavenly patrons of the Kingdom of Scotland; but to omit

all notice of her would make our calendar incomplete. It will be sufficient to note

briefly the chief events of her life. Saint Margaret was granddaughter to

Edmund Ironside. Her father, Edward, having to fly for his life to Hungary,

married Agatha, the sister-in-law of the king. Three children were born to

them. When Edward the Confessor ascended the English throne, Prince Edward

returned with his family to his native land, but died a few years after. When

William the Conqueror obtained the crown, Edgar, the son of Edward, thought it

more prudent to retire from England, and took refuge with his mother and

sisters at the court of Malcolm III of Scotland, having been driven on the

Scottish coast by a tempest. Malcolm, attracted by the virtue and beauty of

Margaret, made her his bride, and for the thirty years she reigned in Scotland

she was a model queen. The historian Dr. Skene says of her: “There is perhaps

no more beautiful character recorded in history than that of Margaret. For

purity of motives, for an earnest desire to benefit the people among whom her

lot was cast, for a deep sense of religion and great personal piety, for the

unselfish performance of whatever duty lay before her, and for entire

self-abnegation she is unsurpassed, and the chroniclers of the time all bear

witness to her exalted character.” Her solicitude for the nation was truly

maternal. She set herself to combat, with zeal and energy, the abuses which had

crept into the practice of religion, taking a prominent part—with her royal

husband as the interpreter of her southern speech—in many councils summoned at

her instigation. She loved and befriended clergy and monks, and was lavish in

her charity to the poor. Her own children, through her training and example,

were one and all distinguished for piety and virtue. Her three sons, Edgar,

Alexander and David, were remarkable for their unparalleled purity of life:

David’s two grandsons, Malcolm IV and William, and William’s son and grandson,

Alexander II and III, were noble Catholic kings. Thus did the influence of this

saintly queen extend over the space of two hundred years and form monarchs of

extraordinary excellence to rule Scotland wisely and well.

Saint Margaret died on

the 16th of November at the age of forty-seven. Her body was buried with that

of King Malcolm, who had been killed in battle only four days before her own

death, in the church they had founded at Dunfermline. At the Reformation her

relics were secretly carried into Spain, together with the remains of her

husband, and placed in the Escurial. Her head, with a quantity of her long,

fair hair, was preserved for a time by the Scottish Jesuits at Douai. The

sacred relics disappeared in the French Revolution. Fairs on the saint’s

feast-day, known as “Margaretmas,” were held at Wick, Closeburn (Dumfries

shire) and Balquhapple (now Thornhill) in Kincardineshire. Saint Margaret’s

Well at Restalrig near Edinburgh, was once covered by a graceful Gothic

building, whose groined roof rested on a central pillar; steps led down to the

level of the water. It is thought to have been erected at the same period as

that covering Saint Triduana’s Well in the same place.

When the North British

Railway required the spot for the building of storehouses, the well-house was

removed to Queen’s Park, where it still stands, but the spring has disappeared

(see October 8th). Innocent XII at the petition of James VII (and II) in 1693,

placed Saint Margaret’s feast on June 10th, the birthday of the King’s son

James (stigmatised the “Old Pretender”), but Leo XIII, in 1898, restored it for

the Scottish calendar to the day of her death.

MLA

Citation

Father Michael

Barrett, OSB.

“Saint Margaret, Queen”. The Calendar of Scottish

Saints, 1919. CatholicSaints.Info.

8 December 2019. Web. 11 January 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/calendar-of-scottish-saints-saint-margaret-queen/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/calendar-of-scottish-saints-saint-margaret-queen/

Saint Barbara, Saint Cecilia, Saint Margaret. Second window on the north side of the nave of St Peter's parish church, Cowfold, West Sussex, with glass made by James Powell and Sons

Mothers

of History – Saint Margaret of Scotland

Saint

Margaret was born in Hungary in the year 1048. She was of royal stock, whose

history is intimately bound up with the history of England.

On the death of King

Edmund Ironsides, Canute of Denmark usurped the English throne and exiled

Edmund’s two young sons, Edmund and Edward, to Sweden. Canute asked the Swedish

King to put them to death. He, however, secretly sent them to Saint Stephen,

King of Hungary, who treated them as his own children.

Prince Edmund, on

reaching maturity, married Saint Stephen’s only daughter. Of this union were

born a son and two daughters, of whom Margaret was the elder.

An ancient biographer

records of the child Margaret that ‘she was more beautiful than any other girl

of her time.’ Margaret was endowed with great intelligence. Saint Stephen’s

court was a model one, and from the saintly king, Margaret learned the lessons

of holiness, which rendered her so illustrious as Queen of Scotland. Renowned

for her beauty, she was deeply admired for the modesty of her demeanour and

gentle disposition. At an early age, she showed a great love of prayer and

liked to spend time before the Blessed Sacrament and at shrines of Our Lady.

Taught by Saint Stephen,

she was prodigal in her generosity to the poor. So much so, that she earned the

beautiful title of ‘Mother of the Motherless and Treasurer of God’s poor.’ At

the death of her father, Prince Edmund, Margaret resolved to leave the Court

and enter the convent. Such, however, was not the Will of God. It was left for

her younger sister, Christina, to become the nun.

History was being made in

England all this while. Canute, the usurper, died and Saint Edward the

Confessor became King of England. He immediately sent for the exiles. Margaret

and her brother, Edgar, thus came to the English court. Great joy attended

their return. But Edward the Confessor died soon after their arrival. Prince

Edgar, Margaret’s brother, was now heir to the throne. Edgar was young and

Harold, who was afterwards defeated by William the Conqueror, seized the

throne. Edgar was forced to flee for his life. Margaret accompanied him. They

were shipwrecked off the coast of Scotland. Malcolm III of Scotland received

them royally and gave them a permanent home at his court.

The characteristics that

distinguished Margaret in Hungary were to the fore in Scotland. All admired

beauty, fortitude under trials, evenness of temper, and unbounded sympathy for

the sick and the poor. King Malcolm requested Margaret’s hand in marriage.

Margaret still longed for the religious life, but, persuaded she was fulfilling

the Divine Will, gave her consent. In 1070, at Dunfermline, she became Queen of

Scotland. She was then twenty-four years of age.

As a thanksgiving to God,

she endowed Dunfermline with a magnificent church, dedicated to the Most Holy

Trinity. ‘Whilst honouring the Three Divine Persons,’ she said, ‘I wish to

ensure, as far as I can, the salvation of my beloved husband and of any

children God may give me, as also my own.’

God blessed her with

children. Six sons and two daughters were born to the royal couple. The

children were early trained to virtue by their saintly mother. She personally

superintended their education.

She chose their

instructors herself so that none but virtuous tutors should influence them. She

even administered corporal punishment, if she deemed it necessary.

Her love for the poor

increased, if anything, with her years. Malcolm gave her free access to the

royal coffers. She dotted the country with abbeys, schools, monasteries and

hospices for travellers and the sick.

Margaret had her

slanderers, but her virtue was proof against all evil tongues. There were those

who would play Iago to Malcolm’s Othello. Their filthy suggestions were refuted

by Malcolm’s own investigations.

Following her to a

supposed assignation in the forest, the mentally tortured King found her in a

cave she had transformed into a chapel. Burning with shame and self-reproach,

the royal eavesdropper heard her praying aloud, beseeching God to “fill the

mind of my dear spouse with Your Divine light. Incline his heart to all that is

highest and best. May he love You more dearly, follow You more nearly and

realize the truth of Your Divine words: ‘What does it profit a man if he gain

the whole world and suffer the loss of his own soul?’ Amen.”

Malcolm burst in with the

heartfelt prayer, ‘My God, forgive me. All unworthy that I am, I render You

thanks for the woman You have given me, my holy queen.’ Falling on his knees,

he humbly confessed his unworthy thoughts and begged Margaret’s pardon, which

she lovingly granted.

From then on, the

chronicler of the times tells us, Malcolm would often ‘watch the night in

prayer by her side.’

Margaret passed to her

eternal reward on the day the now pious Malcolm fell in battle at Alnwick. On

November 16, 1093, she heard from Our Divine Lord the ‘Well done’ of the good

and faithful servant.

Saint Margaret of

Scotland, wife, mother, queen, pray for us.

– text taken from Mothers of History, by J T Moran, C.SS.R., Australian

Catholic Truth Society, 1954>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/mothers-of-history-saint-margaret-of-scotland/

Statua di Santa Margherita di Scozia nella grotta situata a Dunfermline

Statue of Saint Margaret of Scotland in her cave at Dunfermline

Statua di Santa Margherita di Scozia nella grotta situata a Dunfermline

Statue of Saint Margaret of Scotland in her cave at Dunfermline

Statua di Santa Margherita di Scozia nella grotta situata a Dunfermline

Statue of Saint Margaret of Scotland in her cave at Dunfermline

St

Margaret's Cave. This small building which is situated in the Glen Bridge car

park is the entrance to the cave which is named after Queen Margaret, who used

to meditate and pray here in the 11th century. She was Queen of Scotland,

canonised in 1250 and made patron saint of Scotland in 1673. The cave is one of

Scotland's holiest shrines.

During

the construction of the car park in 1969 the council wanted to bury the cave

under tons of concrete. This sparked a public outcry and the council then

agreed to build a tunnel under the car park to allow access to the cave.

From this building 84 steps lead down to a tunnel which then turns into a single chamber 10 feet long by 8 feet wide and 8 feet high. 225048 225037

June 10

ST MARGARET OF SCOTLAND,

MATRON [1] (A.N. 1093)

Margaret was a daughter

of Edward d'Outremer ("The Exile"), next of kin to Edward the

Confessor, and sister to Edgar the Atheling, who took refuge from William the

Conqueror at the court of King Malcolm Canmore in Scotland. [She was born in

Hungary from Edward's Hungarian wife, Agatha.] There Margaret, as beautiful as

she was good and accomplished, captivated Malcolm, and they were married at the

castle of Dunfermline in the year 1070, she being then twenty-four years of

age. This marriage was fraught with great blessings for Malcolm and for

Scotland. He was rough and uncultured but his disposition was good, and

Margaret, through the great influence she acquired over him, softened his

temper, polished his manners, and rendered him one of the most virtuous kings

who have ever occupied the Scottish throne. To maintain justice, to establish

religion, and to make their subjects happy appeared to be their chief object in

life. "She incited the king to works of justice, mercy, charity and other

virtues", writes an ancient author, "in all which by divine grace she

induced him to carry out her pious wishes. For he, perceiving that Christ dwelt

in the heart of his queen, was always ready to follow her advice." Indeed,

he not only left to her the whole management of his domestic affairs, but also

consulted her in state matters.

What she did for her

husband Margaret also did in a great measure for her adopted country, promoting

the arts of civilization and encouraging education and religion. She found

Scotland a prey to ignorance and to many grave abuses, both among priests and

people. At her instigation synods were held which passed enactments to meet

these evils. She herself was present at these meetings, taking part in the

discussions. The due observance of Sundays, festivals and fasts was made

obligatory, Easter communion was enjoined upon all, and many scandalous

practices, such as simony, usury and incestuous marriages, were strictly

prohibited. St Margaret made it her constant effort to obtain good priests and

teachers for all parts of the country, and formed a kind of embroidery guild

among the ladies of the court to provide vestments and church furniture. With

her husband she founded several churches, notably that of the Holy Trinity at

Dunfermline.

God blessed the couple

with a family of six sons and two daughters, and their mother brought them up

with the utmost care, herself instructing them in the Christian faith and

superintending their studies. The daughter Matilda afterwards married Henry I

of England and was known as Good Queen Maud, [2] whilst three of the sons,

Edgar, Alexander and David, successively occupied the Scottish throne, the last

named being revered as a saint. St Margaret's care and attention was extended

to her servants and household as well as to her own family; yet in spite of all

the state affairs and domestic duties which devolved upon her, she kept her

heart disengaged from the world and recollected in God. Her private life was

most austere: she ate sparingly, and in order to obtain time for her devotions

she permitted herself very little sleep. Every year she kept two Lents, the one

at the usual season, the other before Christmas. At these times she always rose

at midnight and went to the church for Matins, the king often sharing her

vigil. On her return she washed the feet of six poor persons and gave them

alms.

She also had stated times

during the day for prayer and reading the Holy Scriptures. Her own copy of the

Gospels was on one occasion inadvertently dropped into a river, but sustained

no damage beyond a small watermark on the cover: that book is now preserved

amongst the treasures of the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Perhaps St Margaret's

most outstanding virtue was her love of the poor. She often visited the sick

and tended them with her own hands. She erected hostels for strangers and

ransomed many captives -- preferably those of English nationality. When she

appeared outside in public she was invariably surrounded by beggars, none of

whom went away unrelieved, and she never sat down at table without first having

fed nine little orphans and twenty-four adults. Often -- especially during

Advent and Lent -- the king and queen would entertain three hundred poor

persons, serving them on their knees with dishes similar to those provided for

their own table.

In 1093 King William

Rufus surprised Alnwick castle, putting its garrison to the sword. King Malcolm

in the ensuing hostilities was killed by treachery, and his son Edward was also

slain. St Margaret at this time was lying on her death-bed. The day her husband

was killed she was overcome with sadness and said to her attendants,

"Perhaps this day a greater evil hath befallen Scotland than any this long

time." When her son Edgar arrived back from Alnwick she asked how his

father and brother were. Afraid of the effect the news might have upon her in

her weak state, he replied that they were well. She exclaimed, "I know how

it is!" Then raising her hands towards Heaven she said, "I thank

thee, Almighty God, that in sending me so great an affliction in the last hour

of my life, thou wouldst purify me from my sins, as I hope, by thy mercy."

Soon afterwards she repeated the words, "O Lord Jesus Christ who by thy

death hast given life to the world, deliver me from all evil!" and

breathed her last. She died four days after her husband, on November 16, 1093,

being in her forty-seventh year, and was buried in the church of the abbey of Dunfermline

which she and her husband had founded. St Margaret was canonized in 1250 and

was named patroness of Scotland in 1673.

The beautiful memoir of

St Margaret which we probably owe to Turgot, prior of Durham and afterwards

bishop of St Andrews, a man who knew her well and had heard the confession of

her whole life, leaves a wonderfully inspiring picture of the influence she

exercised over the rude Scottish court. Speaking of the care she took to

provide suitable vestments and altar linen for the service of God, he goes on:

These works were

entrusted to certain women of noble birth and approved gravity of manners who

were thought worthy of a part in the queen's service. No men were admitted

among them, with the sole exception of such as she permitted to enter along

with herself when she paid the women an occasional visit. There was no giddy

pertness among them, no light familiarity between them and the men; for the

queen united so much strictness with her sweetness of temper, so pleasant was

she even in her severity, that all who waited upon her, men as well as women,

loved her while they feared her, and in fearing loved her. Thus it came to pass

that while she was present no one ventured to utter even one unseemly word,

much less to do aught that was objectionable. There was a gravity in her very

joy, and something stately in her anger. With her, mirth never expressed itself

in fits of laughter, nor did displeasure kindle into fury. Sometimes she chid

the faults of others -- her own always -- with that commendable severity

tempered with justice which the Psalmist directs us unceasingly to employ, when

he says "Be ye angry and sin not". Every action of her life was

regulated by the balance of the nicest discretion, which impressed its own

distinctive character upon each single virtue. When she spoke, her conversation

was seasoned with the salt of wisdom; when she was silent, her silence was

filled with good thoughts. So thoroughly did her outward bearing correspond

with the staidness of her character that it seemed as if she had been born the

pattern of a virtuous life. I may say, in short, every word that she uttered,

every act that she performed, showed that she was meditating on the things of

Heaven.

By far the most valuable

source for the story of St Margaret's life is the account from which the above

quotation is taken, which was almost certainly written by Turgot who, in spite

of his foreign-sounding name, was a Lincolnshire man of an old Saxon family.

The Latin text is in the Acta Sanctorum, June, vol. ii, and elsewhere; there is

an excellent English translation by Fr W. Forbes-Leith (1884). Other materials

are furnished by such chroniclers as William of Malmesbury and Simeon of

Durham; most of these have been turned to profit in Freeman's Norman Conguest.

An interesting account of the history of her relics will be found in DNB., vol.

xxxvi. There are modern lives of St Margaret by S. Cowan (1911), L. Menzies

(1925), J. R. Barnett (1926) and others. For the date of her feast, see the

Acta Sanctorum, Decembris Propylaeum, p. 230.

[1] In Scotland the feast

of St Margaret is observed on the anniversary of her death, November 16.

[2] Through this marriage

the present British royal house is descended from the pre-Conquest kings of

Wessex and England.

Butler's Lives of

the Saints, Christian Classics, 1995

SOURCE : http://www.katolikus.hu/hun-saints/margaret-sc.html

Karl Parsons (1884–1934), St. Margaret stained glass window, St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh 1915

Margaret of Scotland

c. 1045 - 1093

Margaret, despite her

appellation, was born a Saxon in 1046 and raised in Hungary. She came to

England in 1066 when her uncle, King Edward the Confessor, died and Margaret's

brother, Edgar Atheling, decided to make a claim to the English throne. The

English nobles preferred Harold of Wessex over Edgar, but later that year Duke

William of Normandy made it all rather a moot point by invading England and

establishing himself as King. Many members of the English nobility sought

refuge in the court of King Malcolm III Canmore of Scotland, who had himself

been an exile in England during the reign of Macbeth. Among the English

refugees were Margaret and Edgar. While King Malcom was hospitable to all his

new guests, he was rather more hospitable to Margaret, marrying her in 1070 to

make her Queen of Scotland.

Margaret impressed not

only Malcolm but many other members of the Scottish Court both for her

knowledge of continental customs gained in the court of Hungary, and also for

her piety. She became highly influential, both indirectly by her influence on

Malcolm as well as through direct activities on her part. Prominent among these

activities was religious reform. Margaret instigated reforms within the

Scottish church, as well as development of closer ties to the larger Roman

Church in order to avoid a schism between the Celtic Church and Rome. Further,

Margaret was a patroness both of the célidé, Scottish Christian hermits, and

also the Benedictine Order. Although Benedictine monks were prominent

throughout western continental Europe, there were previously no Benedictine

monasteries known to exist in Scotland. Margaret therefore invited English

Benedictine monks to establish monasteries in her kingdom.

On the more secular side,

Margaret introduced continental fashions, manners, and ceremony to the Scottish

court. The popularization of continental fashions had the side-effect of

introducing foreign merchants to Scotland, increasing economic ties and communication

between Scotland and the continent. Margaret was also a patroness of the arts

and education. Further, Malcolm sought Maragret's advice on matters of state,

and together with other English exiles Margaret was influential in introducing

English-style feudalism and parliament to Scotland.

Margaret was also active

in works of charity. Margaret frequently visited and cared for the sick, and on

a larger scale had hostels constructed for the poor. She was also in the habit,

particularly during Advent and Lent, of holding feasts for as many as 300

commoners in the royal castle.

King Malcolm, meanwhile,

was engaged in a contest with William the Conqueror over Northumbria and

Cambria. After an unsuccessful 1070 invasion by Malcom into Northumbria

followed by an unsuccessful 1072 invasion by William into Scotland, Malcom paid

William homage, resulting in temporary peace. William further made assurance of

this peace by demanding Malcolm's eldest son Donald (by Malcolm's previous wife