Maestro di S. Severino, S. Severinop in Trono e Santi, 1472 ca., da Chiesa SS Severino e Sossio, Galleria Napoletana (Museo di Capodimonte), Napoli

Maestro

di S. Severino, S. Severinop in Trono e Santi, 1472 ca., da Chiesa SS Severino

e Sossio, Galleria Napoletana (Museo di Capodimonte), Napoli

Maestro di San Severino ; Severin of Noricum ; Saint Sossius ; Paintings

of Madonna and Child in the Galleria Napoletana (Museum of Capodimonte) ; Galleria

Napoletana (Museum of Capodimonte)

Darstellung des Severin von Noricum. (Detail aus dem Severinaltar in Neapel)

Saint Séverin de Norique

Abbé en Autriche (+

482)

Protecteur de l'Autriche

et de la Bavière. Moine inconnu, venu sans doute de l'Asie Mineure après les

invasions d'Attila. Il fonda en 454 un monastère à Passau en Allemagne et, de

là, il évangélisa toutes ces régions. Il défendit les pauvres contre les petits

rois barbares et sut faire vivre en bonne entente les Romains et les Barbares.

Il mena une vie ascétique qui impressionnait son disciple et biographe,

Eugypius. Il inculqua à tous ses convertis les mœurs chrétiennes.

En Norique, sur les bords

du Danube, vers 482, saint Séverin, prêtre et moine, qui vint dans cette

province après la mort d’Attila, prince des Huns, y prit la défense des

populations sans appui, adoucit ces hommes sauvages, convertit les infidèles,

construisit des monastères et instruisit dans la foi les ignorants.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/393/Saint-Severin-de-Norique.html

Pfarrkirche hl. Severin, Anton-Bruckner-Straße 12, Tulln, Niederösterreich - Darstellung hl. Severin gegenüber dem Portal

Pfarrkirche

hl. Severin, Anton-Bruckner-Straße 12, Tulln, Niederösterreich - Darstellung

hl. Severin gegenüber dem Portal

8 janvier. Saint Séverin

du Norique, Apôtre de l'Autriche et de la Bavière. 482.

Pape : Saint Simplice.

Empereur romain, d'Orient : Zénon.

Chute de l'empire romain d'Occident : Julius Népos (+480) ; Romulus Augustule.

Chef des Hérules, patrice romain, etc. : Odoacre.

Roi des Francs Saliens : Clovis

Ier.

" Quand vous aurez vaincu, ne tuez pas les ennemis."

Saint Séverin au chef de la garnison de Vienne.

Dans le Ve siècle, un

Solitaire d'Orient, poussé par l'esprit d'en-haut, vint annoncer la pénitence

et le royaume de Dieu aux peuples barbares du Septentrion. On ne put savoir sa

patrie ; aux questions qu'on lui faisait à ce sujet, il répondait qu'un prédicateur

de l'Evangile n'avait point d'autre âge que l'éternité, ni d'autre pays que le

ciel. Toutefois, on reconnut facilement, à son parler et à ses manières, qu'il

était Romain ou d'un endroit ou d'un endroit où l'on parlait encore le bon

latin. Comme il était humble et qu'il refusait de dire la condition de sa

famille, on crut, non sans raison, que ses parents étaient illustres selon le

monde. Il faisait précéder sa prédication de l'exemple de sa vie ; il était

pieux, austère et charitable envers les pauvres, les malades et tous les

nécessiteux.

Au temps où vécut saint Séverin, il y a plus de treize cents ans, Attila, ce

terrible roi des Huns, dont nous avons déjà parlé, venait de mourir. En

mourant, il laissa plusieurs fils, qui se disputèrent l'empire, principalement

dans les contrées situées le long des deux rives du Danube. Au loin régnaient

la terreur et la désolation. Saint Séverin demeurait alors aux environs de la

ville d'Astures ; il anonça aux habitants de cette ville qu'ils étaient menacés

des horreurs de la guerre, et que leur cité serait détruite, à moins qu'ils ne

fléchissent le ciel par des jeûnes, des prières et des aumônes. Pour leur

malheur, les Asturiens n'écoutèrent pas les sàges exhortations du Saint, et

leur ville fut ruinée de fond en comble, de sorte qu'aujourd'hui l'on ne sait

plus même le lieu où elle s'est trouvée (d'aucuns pensent que Stockeraw, au

nord de Vienne est située sur le site de l'ancienne Astures).

Mais avant le désastre,

saint Séverin s'était retiré dans une autre ville, appelée Cumanis (aujourd'hui

Haynburg, à une vingtaine de kilomètres à l'Ouest de Vienne). Là il renouvela

ses conseils et ses sinistres prédictions ; mais là aussi il ne fut pas écouté.

Alors un vieillard, qui seul avait échappé ua massacre et à l'incendie

d'Astures, raconta aux habitants de Cumanis tous les détails de l'horrible

désastre dont il avait été témoin ; et il ajouta qu'avant l'événement un homme

inconnu était venu leur prédire tout ce qui était arrivé, et les avait exhortés

à détourner ces malheurs par la pénitence :

" Et c'est parce

qu'on ne l'a pas cru, dit-il en terminant son récit, que tous ces malheurs sont

venus sur ma patries !..."

Et le vieillard, ayant vu

saint Séverin qui l'écoutait discrètement mélé à son nombreux auditoire, s'écria

aussitôt :

" C'est lui-même,

écoutez-le !"

Alors les Cumaniens lui

demandèrent pardon de n'avoir pas voulu l'écouter d'abord et pendant trois

jours ils implorèrent le secours du ciel par des prières, des jeûnes et des

aumônes. Pendant ce temps les farouches ennemis s'étaient rapprochée de Cumanis

mais vers la fin du troisième jour leur camp fut ébranlé par un terrible

tremblement de terre, et ils s'enfuirent épouvantés. Pendant la nuit suivante,

ils s'imaginèrent être poursuivis, et, prenant leurs compagnons pour des

ennemis, ils s'entre-tuèrent.

Une autre

ville * plus loin sur le Danube était désolée par la famine.

C'était au cœur de l'hiver, et l'on attendait des vivres qui devaient arriver

des pays qui sont près de l'Inn. Mais le fleuve était gelé, les bateaux qui

devaient transporter les vivres ne pouvaient arriver. Or, les habitants de

cette ville ayant entendu parler de la merveilleuse efficacité des prières de

saint Séverin, le firent inviter à se rendre auprès d'eux.

Son premier soin, en arrivant, fut de les exhorter à la prière et à la

pénitence. Et presque aussitôt l'on vit arriver une foule de bateaux chargés de

vivres. Que s'était-il donc passé ? Le fleuve, qui depuis longtemps tenait les

bateaux emprisonnés dans les glaces, s'était subitement fondu par l'effet d'un

dégel miraculeux survenu à une époque tout à fait indue. Grande fut la

reconnaissance des Viennois, et grandes furent aussi leurs actions de grâces.

Or, il y avait à Vienne une riche veuve nommée Procule qui avait caché, pendant

une famine, une immense quantité de blé : l'Esprit de Dieu ayant révélé cet

acte d'avarice à Séverin, le Saint reprit publiquement la veuve sans

entrailles, lui reprocha d'être cause, par sa cupidité, de la mort d'un grand

nombre de pauvres, et lui fit voir qu'elle se disait en vain chrétienne,

puisqu'en adorant les richesses elle était tombée dans une détestable

idolâtrie. Procule comprit l'énormité de sa faute et la répara en ouvrant

gratuitement ses greniers.

Dans le même temps, des

barbares menaçaient cette ville par le fer et le feu tout ce qu'ils pouvaient

saisir au dehors des murs, hommes et bêtes, ils l'emmenaient avec eux. La ville

était presque entièrement dépourvue de soldats : saint Séverin harangua leur

chef, lui disant d'avoir confiance en Dieu, et d'aller attaquer résolument

l'ennemi, lui assurant que Dieu lui donnerait la victoire. Il ajouta encore ces

paroles remarquables :

" Mais quand vous

aurez vaincu, ne tuez pas les ennemis !"

Le capitaine partit aussitôt, plein de confiance en Dieu et dans les prières de

son fidèle serviteur. Les barbares, en l'apercevant, furent saisis d'épouvante,

jetèrent leurs armes et s'enfuirent. Ceux d'entre eux qu'on put emmener

captifs, furent conduits devant saint Séverin, qui, après leur avoir reproché

leurs brigandages, leur fit donner à boire et à manger, et puis les renvoya

dans leur pays.

Plus tard saint Séverin se retira dans une solitude, avec le désir de ne plus

vivre que pour Dieu mais il n'y demeura pas longtemps seul. Une foule de gens

allaient le trouver pour lui demander aide et conseil dans leurs besoins

spirituels ou corporels.

Un homme, nommé Rufus,

était malade depuis douze ans : il souffrait horriblement dans tous les membres

de son corps. Or, les moyens employés jusque-là avaient été infructueux. Sa

mère le mit sur une voiture et le conduisit devant l'habitation du Saint. Elle

le supplia de guérir son fils. Le Saint répondit :

" Dieu seul peut

rendre la santé aux malades ; mais je vais vous donner un conseil donnez des

aumônes, selon vos moyens."

Cette femme, n'ayant pour

le moment aucune autre chose à donner, se dépouilla de ses habits pour les

donner aux pauvres. Mais le Saint lui dit :

" Remettez vos

habits ; votre fils va être guéri ensuite, quand vous serez retournée chez

vous, prouvez votre foi par es oeuvres."

Saint Séverin se mit

ensuite en prières ; et aussitôt, au grand étonnement de tous les assistants,

le malade se leva guéri, et s'en retourna chez lui. L'étonnement de tous ceux

qui le connaissaient était si grand, que plusieurs ne voulurent pas croire que

ce fût le même homme qu'ils avaient vu si infirme.

La renommée de la sainteté et des miracles de saint Séverin se répandit au

loin. Plusieurs cités pensèrent que si elles possédaient un tel trésor, elles

seraient à l'abri de toutes les calamités. Le Saint fut donc appelé avec

instance de divers côtés. Or, un jour il se trouvait dans une ville, où une

partie des habitants s'adonnait à l'idolâtrie. Saint Séverin leur représenta

combien grand était ce crime, mais personne ne voulut s'avouer coupable.

Alors il prescrivit un jeûne de trois jours, et ordonna que le troisième jour

chaque famille se rendrait à l'église avec un cierge non allumé. Le Saint

s'étant mis en prières avec les prêtres et le peuple, les cierges des vrais

croyants s'allumèrent d'eux-mêmes, tandis que ceux des idolâtres demeurèrent

non allumés. Etant ainsi miraculeusement convaincus, les idolâtres confessèrent

leur péché ; et le chroniqueur, en rapportant ce fait, ajoute :

" Ô douce puissance

de mon Créateur, qui alluma les coeurs en même temps que les cierges ! Car le

feu se mit aussi aux cierges des coupables, après qu'ils eurent confessé leur

faute et pendant que ce feu consumait la cire qu'ils tenaient en leurs mains,

un feu immatëriel consumait leurs cœurs et faisait couler de leurs yeux des

larmes de componction."

Une autre fois les

campagnes d'alentour furent ravagées par des nuée de sauterelles, et l'on

supplia encore saint Séverin d'éloigner ce fléau par ses prières. Comme

toujours, il recommanda d'avoir recours à la prière, au jeûne et aux aumônes ;

en même temps il exigea que personne n'allât aux champs : " car,

dit-il, vos soins intempestifs seraient faits pour éloigner le secours de Dieu

plutôt que pour chasser les sauterelles ". Tous se conformèrent scrupuleusement

aux prescriptions du Saint, à l'exception d'un tout pauvre homme, qui voulait

absolument aller visiter son champ. Ce champ se trouvait environné de plusieurs

autres, et le pauvre homme s'y rendit pour en chasser les insectes

destructeurs. Mais la nuit même les sauterelles disparurent complètement, en

laissant intacts tous les champs, à l'exception de celui du pauvre incrédule,

sur lequel elles ne laissèrent pas un fruit, ni un brin d'herbe. Ce malheureux

alors courut à la ville, en se lamentant devant tout le monde de ce qui lui

était arrivé. Là-dessus tous sortirent, et virent avec étonnement que leurs

champs avaient été préservés du fléau, et que seul le champ de l'incrédule

avait été dépouillé.

Le Saint alors leur dit

ces simples paroles :

" Apprenez par les

sauterelles à obéir toujours à Dieu !"

Alors le pauvre dit en se

lamentant :

" Je veux bien, à

l'avenir, obéir fidèlement à Dieu, mais qui me donnera de quoi vivre, car mon

champ est dévasté ?"

Le Saint s'adressant à la

foule, dit :

" Il est juste que

celui qui par son châtiment vous apprend à être humbles et obéissants, soit,

pour cette année, nourri par vous."

Et il fut fait une

collecte au profit du pauvre.

Une autre fois une femme,

après avoir été longtemps malade, entra en agonie quelques-uns de ceux qui l'entouraient,

la croyant déjà morte, se mirent à se lamenter, suivant la coutume en pareille

occurrence. Les autres, au contraire, leur imposèrent silence, et, emportant la

malade, ils allèrent la déposer devant la porte de saint Séverin. Le Saint leur

dit :

" Que me voulez-vous

?"

Ils répondirent :

" Nous vous prions

de rendre à ta santé cette femme qui va mourir."

Le Saint reprit :

" Vous demandez trop

à un pauvre pécheur comme moi. Je suis indigne de faire des miracles ; tout ce

que je puis faire, c'est de prier Dieu de me pardonner mes péchés."

Ceux-ci répliquèrent :

" Nous croyons que

si vous priez pour la malade, elle sera guérie."

Alors le Saint se mit à

prier et aussitôt la malade put se lever. Et le Saint leur dit :

" Ce miracle n'est

pas dû à mes mérites, mais à votre foi ; pareille chose arrive journellement en

maint endroit, chez tous les peuples, par la toute-puissance de Dieu, qui seul

peut guérir les malades et ressusciter les morts, afin que tous les peuples

sachent qu'il est le seul vrai Dieu."

Trois jours après, cette

même femme était si bien guérie, qu'elle put de nouveau vaquer à ses travaux

habituels.

Mais, quoiqu'il fît ces prodiges pour gagner les peuples à Jésus-Christ, il ne

voulut point guérir un mal d'yeux qui causait des douleurs très vives à Bonose,

le plus cher de ses disciples ; il aurait cru, en lui enlevant la souffrance,

le priver d'un moyen de perfection. Sa réputation alla si loin que les princes,

même d'au-delà du Danube, infidèles ou Ariens, lui demandaient ses avis pour la

conduite civile de leurs Etats, quoiqu'ils refusassent d'ouvrir les yeux à la

vérité et de corriger les déréglements de leur vie.

Il établit plusieurs

monastères, dont le plus considérable était près de Favienne. Il le quittait

souvent pour aller à deux lieues au delà, dans un endroit écarté, pour prier

plus tranquillement. Mais la charité l'obligeait souvent d'aller en divers lieux,

consoler les habitants dans leurs alarmes car ils se croyaient en sûreté quand

il était avec eux. Il recommandait à ses disciples surtout l'imitation des

anciens et l'éloignement du siècle ; ses exemples leur prêchaient plus encore

que ses paroles. Car, excepté les fêtes, il ne mangeait qu'après le soleil

couché, et en Carême une seule fois dans la semaine il dormait tout vêtu sur un

cilice, étendu sur le pavé de son oratoire. Il marchait toujours pieds-nus,

même lorsque le Danube était gelé. Plusieurs villes le demandèrent pour évêque,

mais il ne voulut jamais se rendre à leurs instances :

" N'est-ce pas assez

que j'aie quitté ma chère solitude pour venir ici vous instruire et vous

consoler ?"

Il ne faut donc pas croire que notre Saint ait établi d'une manière définitive

et durable, ni la religion catholique, ni la vie monastique dans ces pays ; ce

n'était ni le lieu ni le moment. La Providence l'avait amené là, lui Romain,

moine catholique, représentant du monde civilisé qui allait être enfin envahi,

afin d'arrêter un instant, et d'adoucir les envahisseurs ; ainsi Attila trouva

saint Léon au passage du Mincio, saint Aignan sous les murs d'Orléans, et saint

Loup aux portes de Troyes ainsi saint Germain d'Auxerre arrêta Eocharich, roi

des Allemands, au cœur de la Gaule.

L'anachorète qui défendit le Norique, veillait en même temps dans l'intérêt de

toute la Chrétienté. Si le débordement des invasions se fût précipité d'un seul

coup, il aurait submergé la civilisation. L'empire était ouvert, mais les

peuples n'y devaient entrer qu'un à un et le sacerdoce chrétien se mit sur la

brèche, afin de les retenir jusqu'au moment marqué, et pour ainsi dire jusqu'à

l'appel de leur nom. c'était le tour des Hérules : saint Séverin avait contenu

leurs bandes sur le chemin de l'Italie.

Parmi ceux qui venaient

demander sa bénédiction, se trouva un jour un jeune homme, pauvrement vêtu,

mais de race noble, et si grand qu'il lui fallait, se baisser pour entrer dans

la cellule du moine :

" Va, lui dit

Séverin, va vers l'Italie ; tu portes maintenant de chétives fourrures, mais

bientôt tu auras de quoi faire largesse."

Ce jeune homme était

Odoacre, à la tête des Thurilinges et des Hérules ; il s'empara de Rome, envoya

Romulus Augustule mourir en exil, et, sans daigner se faire lui-même empereur,

se contenta de rester le maître de l'Italie. Du sein de sa conquête, il se

souvint de la prédiction du moine romain qu'il avait laissé sur les bords du

Danube, et lui écrivit pour le prier de lui demander tout ce qu'il voudrait.

Séverin en profita pour obtenir la grâce d'un exilé.

Si Odoacre, maître de

Rome, usa de clémence, s'il épargna les monuments, les lois, les écoles, et ne

détruisit que le vain nom de l'empire, c'est qu'il se souvint, notamment, du

moine romain qui avait prédit sa victoire et béni sa jeunesse.

Une autre fois, comme les Allemands ravageaient le territoire de Passau, où il

se trouvait alors, il alla trouver Gibold leur roi, et lui tint un langage si

ferme, que le barbare troublé promit de rendre les captifs et d'épargner le

pays on l'entendit ensuite déclarer à ses compagnons que jamais, en aucun péril

de guerre, il n'avait tremblé si fort. Saint Séverin était donc là comme un

rempart céleste sur les rives du grand fleuve qui ne protégeait plus le

territoire de l'empire. Quand une ville, une contrée de l'empire étaient

menacées par une armée barbare, il entreprenait quelquefois la défense

militaire avec le calme d'un vieux capitaine, rendant d'une parole le courage

aux plus timides, se faisant obéir là où personne ne l'était plus ; s'il

fallait reculer, il organisait la retraite ; s'il n'y avait plus espoir de

salut, il se rendait au camp des vainqueurs, et, au nom de Dieu, il obtenait

que les vaincus seraient respectés dans leurs personnes et dans leurs biens, et

que tous vivraient en paix.

Il avait surtout le plus

grand soin des captifs, d'abord à cause d'eux, en qui il voyait Notre-Seigneur

dans les chaînes et la misère, mais aussi à cause du salut de l'âme des maîtres

qui les opprimaient. Il plaida, selon son habitude, cette sainte cause auprès

de Fléthée, roi des Rugiens, peuplade qui était venue, des bords de la mer

Baltique, s'établir en Pannonie ; peut-être le cœur de ce barbare se serait-il

laissé fléchir ; mais Gisa, sa femme, qui était arienne et plus féroce que lui,

dit un jour à Séverin :

" Homme de Dieu,

tiens-toi tranquille à prier dans ta cellule, et laisse-nous faire ce que bon

nous semble de nos esclaves."

Mais lui ne se lassait

pas et finissait presque toujours par triompher de ces âmes sauvages, mais non

encore corrompues. Sentant sa fin approcher, il mande auprès de son lit de mort

le roi et la reine. Après avoir exhorté le roi à se souvenir du compte qu'il

aurait à rendre à Dieu, il posa la main sur le cœur du barbare, puis se

tournant vers la reine :

" Gisa, aimes-tu

cette âme plus que l'or et l'argent ?"

Et comme Gisa protestait

qu'elle préférait son époux à tous les trésors :

" Eh bien donc,

cesse d'opprimer les justes, de peur que leur oppression ne soit votre ruine.

Je vous supplie humblement tous les deux, en ce moment où je retourne vers mon

maître, de vous abstenir du mal et de vous honorer par vos bonnes

actions."

Saint Séverin avait prédit à ses disciples le jour de sa mort, deux ans

auparavant il les avertit en même temps que les habitants du Norique seraient

obligés de se réfugier en Italie, et leur ordonna de les suivre et d'emporter

son corps. Il fut attaqué d'une pleurésie le 5 janvier 482. Le quatrième jour

de sa maladie, il demanda le saint Viatique ; puis, ayant fait le signe de la

Croix et dit avec le Psalmiste : " Que tout esprit loue le Seigneur

", il s'endormit doucement dans le Seigneur.

CULTE ET RELIQUES

Six ans après, les disciples de saint Séverin furent, selon sa prédiction,

obligés de fuir devant la fureur des barbares ; ils emportèrent le corps de

leur bienheureux Père ; presque toute la contrée l'accompagna, et partout où il

passait on courait lui rendre hommage, de sorte que c'était plutôt un triomphe

qu'une retraite. Il fut déposé à Monte-Feltro, en Ombrie, d'où il fut transféré,

cinq ou six ans après, à Lucullano, entre Naples et Pouzzolles, par l'autorité

du pape saint Gélase.

Saint Séverin est invoqué

particulièrement par les prisonniers, les vignerons et les tisserands.

On y bâtit un monastère

dont Eugippe, auteur de la vie de saint Séverin, fut second abbé. En 910, ses

saintes reliques furent transportées à Naples, dans un monastère de Bénédictins

qui porte son nom. Saint Séverin du Norique est l'un des Patrons de la Bavière,

de l'Autriche, et de Vienne où il est somptueusement fêté dans le quartier de

l'Heiligenstadt, dans le district de Döbling. Il est aussi le saint patron du

diocèse de Linz, de la ville italienne de San Severo.

Les Français, et plus

particulièrement les Parisiens, prendront soin de ne pas le confondre avec

saint Séverin d'Agaume, ou de Paris, ermite, qui, notamment, guérit Clovis

miraculeusement. Ce saint Séverin, quasi-contemporain de notre Saint du jour,

retourna à Notre Père des cieux en 540.

* Probablement

Vienne car le chroniqueur dont s'inspire cette notice - Eugippe, moine

bénédictin de Naples du Ve siècle - nomme cette ville Favienna ou Fabienna. Or,

il n'y a pas loin, philologiquement parlant, de Favienna ou Fabienna à Vienne

qui reçut son nom du général romain Annius Fabianus. Il convient de mentionner

que certains modernes, non sans raisons - lesquelles sont d'être suffisantes

pour le soutenir sans doutes sérieux -, soutiennent qu'il pourrait s'agir de la

ville de Mautern. Cependant, ce que les auteurs catholiques " intégraux

" ont appelé au XIXe " l'hypercritique ", doit être prise en

compte avec une grande prudence compte tenu du fait que ses zélateurs

revisitaient tout au plan historique, hagiographique, etc. Cette

hypercritique, résolument naturaliste, donnera des escrocs contemporains tels

que les sinistres Prieur et Mordillat : leurs descendants directs ;

vulgarisateurs de thèses monstrueuses et hérétiques."

-Saint-Séverin apôtre du Norique (+482)

pnha,n°95, nov. 1998

-Sur la naissance et le

pays d'origine de ce saint règne la plus grande obscurité. Son biographe,

Eugypius, n'en dit rien, et il paraît que Séverin lui-même par humilité, refusa

constamment de répondre aux questions qu'on lui adressait là-dessus. Les historiens

modernes ont émis à ce sujet diverses opinions; voici celle d'un auteur

allemand,Th. Sommerlad

Né en Afrique du Nord

-----Séverin serait né en Afrique, d'une famille distinguée; il aurait été élevé à l'épiscopat dans sa patrie, mais aurait dû prendre le chemin de l'exil, probablement en 437, pour échapper aux vexations que les Vandales ariens faisaient subir aux catholiques. Il se serait retiré en Asie Mineure et y aurait embrassé la vie monastique, selon la règle de Saint-Basile. Ardent défenseur de l'orthodoxie et du monachisme oriental, il serait arrivé dans le Norique, au plus tôt en 434. Peut-être faudrait-il l'identifier avec l'évêque Severianus dont parle Prosper d'Aquitaine (Epitome chronicon, ad an. 437). Cependant, tout cela reste dans le domaine de l'hypothèse.

-----Donc en 454, arrive à Astura, petite ville située au nord du Danube, sur les confins de la Pannonie et du Norique, un inconnu ; Sans aucune lettre de recommandation, il se présente chez le portier de l'église et sollicite une place au foyer. On l'accueille, et sans attirer l'attention, il gagne l'affection de son hôte par sa piété, la pureté de ses moeurs, son zèle charitable. Soudain cet homme obscur sort un jour de son modeste logement ; il parcourt les rues de la ville, appelle à l'église prêtres clercs et laïcs ; là avec un accent d'humilité et de conviction, il avertit ses auditeurs qu'un péril imminent les menace : "Les barbares sont tout près, dit-il, fermez les portes de la ville, mettez-vous en état de défense et, surtout, priez, faites pénitence".

-----Mais c'est en vain, un peuple incrédule méprise ses paroles. Les prêtres eux-mêmes ne veulent pas ajouter foi aux propos de cet étranger qui semble se mêler de prophétiser. Sous le coup d'une juste indignation ; Séverin quitte l'église, rentre chez son hôte, lui prédit le jour et l'heure du désastre : "Pour moi, ajoute-t-il, je quitte cette ville opiniâtre et vouée à une destruction prochaine".

-----Il se rend alors à Comagène, bourg fortifié, situé non loin d'Astura, également au bord du Danube. Une garnison romaine s'était retirée de cette place et les habitants, incapables de se défendre eux-mêmes, avaient traité avec des barbares qui, tyrans autant que protecteurs, s'étaient rendus insupportables.

-----Ils exerçaient une garde sévère sur les portes de la ville. Cependant, sans prendre garde au fugitif d'Astura, ils le laissent passer. Celui-ci va droit à l'église où le peuple est assemblé, et il fait entendre son avertissement sans plus de succès.

-----Dans le même moment, un vieillard, à l'entrée de la ville, demande à y

pénétrer ; il raconte qu'Astura vient d'être mise au pillage, comme cela avait

été prédit par un homme de Dieu. La curiosité s'éveille à ce récit, on laisse

passer le vieillard, qui court à l'église et y reconnaît son hôte dans le

prédicateur improvisé. Devant tout le peuple assemblé, il se jette à ses pieds

et le proclame son sauveur.

Sauvés des Barbares

-----La foule alors se déclare prête à suivre les conseils de Séverin ; dans tout Comagène, ce sont des jeûnes, des prières, des gémissements. Le troisième jour de ces exercices de pénitence, un tremblement de terre se produit, les barbares demandent à quitter la place. Ils se précipitent au dehors ; trompés par l'obscurité, ils croient avoir l'ennemi devant eux, se jettent les uns sur les autres et s'entre-tuent. Le peuple de Comagène est ainsi débarrassé de ses encombrants protecteurs ; on interroge le vieillard d'Astura pour connaître celui qu'il a appelé protecteur. La réponse est que cet homme s'appelle Séverin et vient des régions de l'Orient.

-----A partir de ce moment, la curiosité des habitants de Comagène est excitée au plus haut point ; ils n'osent pourtant pas interroger directement Séverin. Mais après la chute de Romulus Augustule, des Italiens arrivent dans le Norique ; c'est une occasion, semble-t-il de faire parler Séverin qui vient de recevoir comme hôte un prêtre italien nommé Primenius ; on essaie d'employer cet intermédiaire pour en savoir davantage sur les antécédents de Séverin : "Sache seulement, répond-il, à Primenius, que le Dieu qui t'a fait la grâce d'être prêtre m'a ordonné de venir au secours de ces infortunés".

-----Après Comagène, c'est Favianes qui doit à ce saint homme d'être délivré du fléau de la famine et des menaces des Barbares ; il annonce aux habitants auxquels il a prêché la pénitence que Dieu combattra pour eux et, quand cette promesse s'est réalisée, il donne ce dernier avis : "Votre ville n'aura plus à souffrir des déprédations mais à une condition, c'est que, dans la bonne comme dans la mauvaise fortune, vous serez fidèles observateurs du devoir et de la piété". Séverin conçut ensuite le dessein de former une milice spirituelle, et, vers 455, il établit un monastère à quelque distance de Favianes. Homme d'action, il forma ses disciples par ses exemples plus encore que par ses paroles ; en fait de science, il les établit dans un commerce habituel avec les anciens pères ; pour la piété et les moeurs, il les exhorta à ne plus regarder en arrière après avoir quitté le monde et à vivre dans la crainte de Dieu. dans les larmes, les privations et les jeûnes.

-----ll voulut avoir une église dans laquelle il fit placer des autels consacrés aux saints dont il avait pu se procurer des reliques. Sa pratique d'exercer la charité en rachetant des captifs lui valut d'avoir des reliques des saints Gervais et Protais. Il avait entrevu dans une vision un moine porteur de ces reliques, il fit rechercher sur le marché ce moine et réussit à opérer son rachat. Le moine par reconnaissance, céda volontiers les reliques dont il était porteur. Parmi les autres monastères que fonda Séverin dans la région, on ne connaît la situation que d'un seul, celui de Boitro, au confluent de l'Inn et du Danube en face de Passau. Chose étonnante, cet homme d'une activité prodigieuse avait l'amour de la solitude ; il aurait voulu mener au désert la vie contemplative. Jamais il ne voulut accepter la charge de l'épiscopat par humilié et aussi par le désir de garder sa liberté d'allures.

-----Son austérité est à peine concevable ; il avait pour lit un cilice étendu sur le pavé de son oratoire, pour vêtement, en toute saison, une seule tunique ; il ne rompait son jeûne de tous les jours qu'au coucher du soleil ; en carême il ne mangeait qu'une fois par semaine ; en toute saison il marchait pieds nus.

-----Avec une telle austérité pour lui-même, il témoignait aux autres la plus

grande bonté soit pour les âmes, soit pour les corps. Il opéra plusieurs

miracles et même résurrection d'un mort, mais celle-ci ne fut connue qu'après

la mort de Séverin.

Une réputation

grandissante

-----L'action de Séverin s'est étendue à toute une province pour l'amélioration morale de ses habitants, pour la répression des Barbares et leur évangélisation. Trente années d'efforts et d'austérité pour arriver à ce résultat finirent par épuiser ses forces ; il sentait venir son dernier jour et il l'annonça au prêtre Lucillus. Celui-ci était venu le trouver le jour de l'Epiphanie pour lui annoncer que le lendemain il célébrerait l'anniversaire de son ancien évêque, qui avait exercé ses fonctions épiscopales en Réthie. Alors Séverin lui dit : "Si le saint évêque Valentin t'a désigné pour cet anniversaire, je te délègue à mon tour pour me rendre les derniers devoirs et ce sera le même jour". A partir de cet instant, Séverin ne songea plus qu'à se préparer à la mort.

-----Annonçant à ses disciples qu'ils devraient un jour quitter le pays, il leur fit une obligation d'emporter avec eux les ossements de leur père. Le 8 janvier il leur adressa ses dernières recommandations, reçut la sainte communion étendit sa main pour les bénir, entonna le chant du psaume Laudate Dominum in sanctis ejus, ordonnant aux assistants de le continuer et, au dernier verset : "que toute âme loue le Seigneur", il expira (482).

-----Les moines placèrent son corps dans un cercueil, de façon à pouvoir remplir les volontés du défunt quand viendrait l'heure de l'exode, car ils ne doutaient pas que sa prophétie ne se réalisât. Durant les années qui suivirent le monastère fut mis plusieurs fois au pillage.

-----En 486, une invasion de Barbares, les obligea à partir ; on découvrit le corps et, à la grande surprise de tous les témoins, il fut trouvé sans corruption comme au jour du trépas, on changea pieusement les linges et on referma le cercueil.

-----Celui-ci fut placé dans une sorte de chapelle portative et mis sur un charriot traîné par plusieurs chevaux. Le cortège, escorté par des soldats, s'engagea dans les Alpes, descendit vers les côtes de l'Adriatique; sur le parcours, les populations venaient vénérer les saintes reliques, et beaucoup de malades furent guéris.

-----On arriva ainsi à Lucullanum, près de Naples, où une riche dame donna sa

villa pour que les moines en fissent leur monastère. Le corps de Séverin

demeura dans cet endroit jusqu'en 910. Il fut alors transféré à Naples, dans

l'abbaye bénédictine à laquelle on donna le nom de Saint-Séverin. Le

martyrologue romain mentionne ce saint au 8 janvier, que l'on croit avoir été

l'anniversaire de sa mort.

Abbé Vincent Serralda

Vincent Serralda le 22

septembre 1998, à Paris, a rejoint la maison du père. Prêtre magnifique, il

s'était consacré aux Saints d'Afrique du Nord, "ses Berbères" comme

il aimait à les appeler. Il nous a toujours montré de l'affection et a beaucoup

écrit.

Sa mémoire et son oeuvre demeure

SOURCE : https://alger-roi.fr/Alger/religion/pages_liees/st_severin_pn95.htm

Ce

tableau appartient à la cathédrale saint-Étienne de Passau. Les deux premières

lignes de la légende sont en latin : « Un don apostolique est un esprit

qui voit l’avenir. Que d’exploits le père Severinus a-t-il accomplis ! Les deux

lignes suivantes sont en allemand gothique : « Par sa sagesse, son

érudition et ses miracles, il s’est montré apostolique. C’est pourquoi il

convient d’honorer hautement le saint père Severinus ». La forteresse en

feu représentée sur le tableau pourrait être celle de Hainburg/Danube ou de

Salzbourg. (http://www.danube-culture.org/saint-severin-apotre-de-la-frontiere-danubienne-au-cinquieme-siecle/)

Eugippe. Vie de saint Séverin, octobre 1991, Sources Chrétiennes 374. Introduction, texte latin, traduction, notes et index par Philippe Régerat. Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et de l'Institut autrichien de Paris. ISBN : 978-2-204-04460-8. 326 pages

Le Norique (la moderne

Autriche) au 5e siècle, à travers la vie de celui qui fut son apôtre.

Ascète, prédicateur et

homme d'action, Séverin est un de ces témoins qui au Ve siècle incarnent

les vertus évangéliques dans un monde qui voit l'écroulement définitif de

l'ordre romain. Aux avant-postes de l'Empire, dans une province danubienne

agitée en tous sens par les errances des tribus germaniques, il est pour toute

une population désemparée un homme de Dieu, un intercesseur auprès des

puissants et un guide dans les moments les plus critiques. Sa Vie,

composée en 511 par Eugippe, abbé du monastère de Lucullanum près de

Naples, est un document historique d'une valeur inestimable, qui fourmille de

détails concrets sur « la vie quotidienne aux temps des

Barbares » ; elle marque aussi un tournant dans l'évolution du genre

hagiographique et traduit l'émergence d'un nouvel idéal de sainteté où le

service des hommes compte autant que le renoncement aux biens de ce monde.

Philippe Régerat,

agrégé d'Histoire, a été lecteur de français à l'Université de Salzbourg ;

il enseigne actuellement à l'Institut universitaire de formation des maîtres de

Reims.

Le mot du

directeur de Collection

La genèse de cette Vita nous

est connue par la lettre qu’Eugippe adresse au diacre Paschase de Rome pour lui

demander de réviser son ouvrage, et par la réponse de ce dernier. Pour assurer

à son texte une large diffusion, l’auteur a pris le parti de la simplicité.

Divisée en 46 capitula, la Vita accumule les épisodes destinés à

prouver l’élection de S. Séveriin, le grand apôtre du Norique, et l’action de

la grâce divine à travers toutes ses actions. Elle a pour but non seulement

d’offrir un modèle de sainteté à valeur universelle et de remplir le rôle

d’édification de toute littérature hagiographique, mais aussi de fixer la

tradition d’une communauté monastique en lui conservant le souvenir de ses

origines, enfin de promouvoir le culte du saint et de ses reliques. Elle est

surtout un témoignage précieux sur le monachisme sévérinien et sur la vie

chrétienne dans le Norique à l'époque des invasions barbares des Ve-VIe siècles.

Jean-Noël Guinot

Œuvre(s)

contenue(s) dans ce volume

La vie de Séverin est

rédigée en Italie au monastère de Castellum Lucullanum et est documentée par la

correspondance échangée entre Eugippe et le diacre Paschase : elle nous

éclaire sur le refus d’Eugippe d’utiliser la rhétorique classique, et son

dédain pour la littérature profane. Son ouvrage repose uniquement sur la foi et

son but est d’édifier le lecteur.

Nous possédons quatre

familles de manuscrits, dont trois sont intéressantes, classées par Th.

Mommsen :

Une première famille

comprenant les mss Lateranus 79 (Xe s., Rome), Sublacensis 2 (XIe

s., Subiaco), Casinas (XIe s., Monte Cassino), Vaticanus 1197 (XIe

s., Vatican).

La deuxième rassemble un

manuscrit de Turin (biblioteca nazionale, F IV 25, Xe s.), de Rome

(biblioteca Vallicelliana, XII, XIIe s.), et deux de Milan (biblioteca

ambrosiana, D 525 inf., XIe et I 61 inf., XI/XIIe s.)

Troisième

famille : Vindobonensis n. 416 (Vienne, XIe/XIIe s.) ;

Melk, Stifsbibliothek, n. 30 ; ser. nov. 3608 (XIIe/XIIIe

s., Vienne)

L’editio princeps date

de 1570 (L. Surius) et est souvent très défectueuse. L’édition de Th. Mommsen a

longtemps fait autorité ; il a fallu attendre 1963 pour que paraisse une

nouvelle édition de E. Vetter, qui a servi ici. Le texte est divisé en

chapitres et paragraphes conformément à l’usage introduit par H. Sauppe en

1877.

On n’assiste pas aux

progrès continus de Séverin vers un idéal supérieur, mais on lit une

accumulation d’épisodes prouvant son élection divine. On suit la vie de Séverin

dans son déroulement chronologique mais aussi spatial, comme un voyage à

travers le Norique et la Rhétie seconde articulé en trois parties, qui

rappellent certains traits caractéristiques de la structure des

Evangiles : action et prédication dans le Norique ; vallée de Salzach

et Danube jusqu’en Rhétie pour le ramener à son point de départ.

Le texte présente tout

d’abord la correspondance entre Eugippe et Paschase, puis un sommaire en 46

points (ou « mémoires »).

(p. 185)

4. 1. À la même

époque une bande de pillards barbares fit une incursion soudaine et emmena avec

elle tout ce qu’elle trouva hors des murs, les hommes aussi bien que le bétail.

De nombreux habitants de la cité se rassemblèrent alors chez l’homme de Dieu,

tout en larmes, et lui racontèrent les pertes et les malheurs qu’ils venaient

de subir en lui montrant les traces laissées par les derniers pillages.

2. Mais lui interrogea Mamertinus, qui était alors tribun et qui fut par

la suite ordonné évêque pour savoir s’il avait à sa disposition des hommes

armés qui pussent se lancer d’urgence à la poursuite des brigands. Celui-ci

répondit : « J’ai bien encore quelques soldats à ma disposition, mais

je n’ose pas engager le combat contre un ennemi aussi nombreux. Si toutefois Ta

Vénération nous l’ordonne, nous croyons, malgré l’insuffisance de notre

armement, pouvoir grâce à tes prières remporter la victoire. » 3. Et le

serviteur de Dieu dit : « Même si tes soldats sont sans armes, ils en

trouveront maintenant chez l’ennemi : en effet, il n’est besoin ni de la

force du nombre ni du courage de l’homme lorsque Dieu se montre en toute

circonstance notre défenseur. Tu n’as qu’une seule chose à faire : au nom

de Dieu pars sans tarder, pars et garde confiance. »

41, 1. Le jour même où le

très bienheureux Séverin devait quitter son corps, il l’annonça plus de deux

ans à l’avance par l’indication que voici. Le jour de l’Epiphanie, comme le

saint prête Lucillus était venu lui faire part du service solennel qu’il

célèbrerait le lendemain pour l’anniversaire de la mort de son père spirituel

saint Valentin, ancien évêque de Rhétie, Séverin lui répondit : « Si

le bienheureux Valentin t’a désigné pour célébrer cette solennité, moi aussi,

je te laisse le soin de célébrer mes vigiles le même jour quand je serai sorti

de ce corps. » 2. Lucillus fut saisi de tremblement à ces mots et protesta

énergiquement que c’était à lui en quelque sorte de partir le premier vu l’état

de décrépitude où il se trouvait. Séverin ajouta alors : « Il en sera

comme tu l’as entendu, saint prêtre, et les décrets du Seigneur ne seront pas

abolis par quelque volonté humaine que ce soit. »

SOURCE : https://sourceschretiennes.org/collection/sc374

Protasio Crivelli, Madonna col Bambino in trono tra San

Severino Abate e San Sossio Levita e Martire, 1506, 187 x 210, Church of San Giovanni Battista

Also

known as

Severinus of Austria

Severine…

Severino…

Apostle of Austria

Profile

Born to the Roman

nobility. Gave away his wealth to live as a hermit in

the Egyptian desert.

Though he loved the quiet and contemplative life, he felt a call to spread the faith,

and he followed it.

Evangelized in

Noricum (part of modern Austria). Hermit near Vienna.

Prophesied the destruction of Astura, Austria by

the Huns under Attila.

Established refugee centers for people displaced by the invasion. Founded monasteries to

re-establish spirituality and preserve learning in the stricken region

One winter, the city of

Faviana on the River Danube was starving. Following a sermon by Severinus on

penance, the ice cracked, and food barges were able to dock, saving the city.

Noted travelling preacher and healer throughout Austria and Bavaria.

Established funds to ransom and rescue captives.

Ate once a day, less in Lent,

went barefoot, ignored the weather, and slept on a sackcloth that he spread on

the ground where ever he stopped. Foretold the date of his own death, and died singing

Psalm 150.

Born

c.410 in North

Africa

8

January 482 at

Favianae, Noricum (in modern Austria)

of pleurisy

relics moved

to the Benedictine monastery at

Monte Feltre

relics moved

to Castellum Lucullanum in Naples, Italy

relics enshrined in

a chapel at

the Benedictine monastery of

San Severino, Naples in 910

relics moved

to Fratta Maggiore in Avera, Italy in 1807

–

–

abbot in

a tomb with staff and crucifix

with Odoacer (Severinus

prophesied an invasion by him)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Sabine Baring-Gould

Pictorial

Half Hours with the Saints

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, by Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

images

video

ebooks

Life

of Saint Severinus, by Eugippius

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

websites

in nederlandse

nettsteder

i norsk

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

MLA

Citation

“Saint Severinus of

Noricum“. CatholicSaints.Info. 25 April 2024. Web. 18 June 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-severinus-of-noricum/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-severinus-of-noricum/

Detail

des Hauptportals der Sieveringer Pfarrkirche

Book of Saints

– Severinus – 8 January

Article

(Saint) Bishop (January

8) (5th

century) There is considerable difficulty in identifying this Saint.

The Martyrology notice describing him as brother of the Martyr Saint Victorinus

can scarcely be upheld. He was probably the missionary Bishop or Abbot, Saint Severinus,

who evangelised the

countries bordering on the Upper Danube, and whose body was brought to Naples six

years after his death (A.D. 482).

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Severinus”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

25 December 2016. Web. 18 June 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-severinus-8-january/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-severinus-8-january/

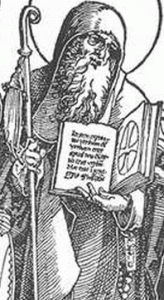

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Die Schutzheiligen

von Österreich, Holzschnitt, ohne Monogramm, 17,7 x 36 cm, Wasserzeichen

kleines gotisches p und Wäppchen (um 1625), späterer Abdruck des II. Zustandes

(Meder 219 g), Drucklegung um 1625. Dorotheum

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Die Schutzheiligen

von Österreich, Holzschnitt, ohne Monogramm, 17,7 x 36 cm, Wasserzeichen

kleines gotisches p und Wäppchen (um 1625), späterer Abdruck des II. Zustandes

(Meder 219 g), Drucklegung um 1625. Dorotheum

St. Severinus of Noricum

Feastday: January 8

Patron: of Noricum (modern Austria); San Severo, Italy

Death: 482

Monk, hermit, and

founder. He labored to evangelize the region of Noricum (part of. modem

Austria), establishing a number of monasteries along the Danube River near

modern Vienna. In his last years, he gave aid and comfort to the many refugees

and victims of the invasion of the region by Attila and the Huns. He was known

for his preaching and prophecies, Severinus died on January 5. His relics were

later carried to Naples. Italy, and enshrined in the Benedictine monastery of

San Severino.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=2523

Breitenfelder

Pfarrkirche - Statue hl. Severin am Triumphbogen

Severinus of Noricum,

Hermit (RM)

Died at Favianae in

Noricum (Austria), c. 476-78. Severinus was a Roman citizen who gave all his

worldly goods to live for a time in the deserts of Egypt. Here he was torn

between his desire to live alone and God's call for him to evangelize

unbelievers. Guess who's will triumphed? Severinus followed God's call to

Austria, which at that time was a highway of invading barbarians, its towns

plundered and beleaguered.

About 453, Severinus came

as a mysterious and unknown man sent by God in that unhappy hour to bring help

to Noricum's suffering people. He gave no information as to who he was beyond

his name, which indicated his high rank, and it was obvious from his manner

that he was a man of scholarship and distinction. He appeared to be an African

Roman from Carthage and a fellow-countryman of Saint Augustine of Hippo.

Attila, the Scourge of God, had just died, leaving behind him, with the break-

up of his empire, confusion and chaos, and the fair and fertile lands of

central and southern Europe were at the mercy of leaderless armies and

plundering tribes.

Into this scene of

wretchedness and distress came Severinus, who settled as a hermit near Vienna.

The work was not easy. Many people ignored all that he preached, but--knowing

that God doesn't ask us to be successful, only obedient--Severinus continued to

preach and found monasteries along the Danube, seeing these as oases of

Christianity in an evil land.

He warned the inhabitants

of approaching invasion, but his words went unheeded. They replied with scorn

that the proud city of Vienna would never surrender and that they had no fear

of the barbarian hordes. But when his words proved only too true, in their

helplessness they sent for him, and quietly and calmly he came to their rescue

and organized relief. He discovered that a rich woman had hidden away vast

quantities of food, which Severinus persuaded her to give to the starving.

He put new heart into the

people, gave them courage to go out to meet the wild German horsemen, and

strengthened the defenses of the city. Then, providentially, the ice melted on

the Danube and the river was filled with ships of food. Thus Severinus stood in

the path of the Goths, and the fear of him was to them, we are told, as the

hand of God.

During this time

Severinus was a great apostle of penance. He redeemed captives, helped to

comfort the oppressed and the poor, tended the sick, and undertook many efforts

for the instruction of the Catholic people of the Danube valley near Vienna. He

also worked miracles. It seems that he drove away a plague of locusts that

threatened to bring another famine. Slowly many Austrians accepted his faith.

He was saddened that he never managed to heal the blindness of one of his

greatest friends, but Severinus continued to trust in God.

When the cloud of terror

lifted, he retired to his hermit's cell, but still continued his relief work of

securing food, redeeming captives, and conciliating enemy tribes; and to this

he added many other works of sanctity and charity. His difficulty was how to

preserve a life of detachment amid so much pressure of activity, for the more

he longed to dwell in solitude and lead a simple life, the greater were the

demands made upon him.

Even the enemies of

Austria came under this influence. The proud and desperate Odoacer, the boldest

of the barbarians, sought his counsel, but on reaching the cell of the hermit,

found it too small for his great height. "Stoop low," said Severinus,

and the ambitious Goth willingly stooped and entered to receive his blessing.

Severinus also built many

churches and evangelized widely in Austria and Bavaria. To Saint Severinus is

attributed the honor of establishing many monasteries, though he himself

remained a contemplative, living apart in a spirit of great penance and prayer.

He became the popular

saint of that area. He went barefoot, even in mid-winter when the Danube was

frozen, and he insisted on possessing only one tunic. It is said that he never

ate until sunset and that in Lent he permitted himself only one meal weekly. To

the end he preserved a simple and austere life. He refused a bishopric, though

it is doubtful whether he was even ordained.

For 30 years this saintly

and active man, whose origin remained unknown, carried on his noble and

enterprising work, conferring with kings and commoners. It is said that he

predicted the day of his death. As he lay dying of pleurisy those around him

could hear him singing the words of the Psalmist: "Let everything that has

breath, praise the Lord." And so he died happily in peace and tranquility.

Six years after his death, his monks were driven from Austria and carried his

relics to Naples, Italy, where the great Benedictine monastery of San Severino

was built to enshrine them (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Encyclopedia,

Gill).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0108.shtml

Pictorial

Half Hours with the Saints – Saint Severinus

Do Penance

Saint Severinus quitted

the solitudes of the East, where he had been devoting himself to the exercises

of the coenobitic life, in order to evangelize the population of Norica, a

province which comprised the greater part of Austria and the Tyrol. He at first

encountered great resistance, but soon effected wonders of conversion, as well

by reason of his humble and mortified life, as because he announced to his

hearers the calamities wherewith the rebellious nations would be afflicted. “Do

penance,” exclaimed he, “sin is the cause of all the woes that God scatters

upon the earth!” Before consenting to pray for those who were afflicted, and

before releasing them from their infirmities, he required that they should do

penance. His own life showed forth the constant example thereof. He foretold to

Odoacer, king of the Herules, that he was to lay waste Italy, by way of

punishment for its crimes; and the prophecy was amply verified. Hence kings and

nations and rulers ended by holding him in singular veneration, regarding him

as the envoy of Heaven. He yielded up his spirit on the 9th January 482.

Moral Reflection

If not out of tenderness

towards Ood, let us, at least from charity for ourselves, repair our past

guilt, and avoid committing fresh offences; for, “As by one man sin entered

into the world, 80 death passes by sin.” – Romans 5:12

– from Pictorial

Half Hours with the Saints, by Father Auguste

François Lecanu, 1865

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-half-hours-with-the-saints-saint-severinus/

Buntglasfenster

in der Kirche von Oberkreuzstetten, Gemeinde Kreuzstetten, Niederösterreich,

Österreich

Stained-glass window at the parish church of Oberkreuzstetten, municipality Kreuzstetten, Lower Austria, Austria

Saint of the Day – 8

January – Saint Severinus of Noricum (c410-482) “The Apostle to Noricum”

Posted on January

8, 2023

Saint of the Day – 8

January – Saint Severinus of Noricum (c410-482) Abbot, Hermit, Missionary,

established Monasteries and refuge centres for those stricken by war. Severinus

was graced with the gifts of prophecy and miracles. He is known as “The

Apostle to Noricum” – Noricum is the Latin name for the Celtic Kingdom or

Federation of Tribes which included most of modern Austria and part of

Slovenia. Born in c410 and died on 8 January 482 at Favianae, Noricum of

natural causes. Patronages – against famine, of linen weavers,

prisoners, vineyards/vintners/wine farms, Austria, Bavaria, Germany, the

Diocese of Linz, Austria. Also known as – Severrin, Severino.

The Roman Martyrology

reads today: “This same day, among the inhabitants of Noricum (now Austria),

the Abbot, St Severin, who preached the Gospel in that country and is called

it’s apostle. By Divine Power, his body was carried to Lucullanum, near Naples

and thence transferred to the Monastery of St Severin.”

It has been speculated

that Severinus was born in either Southern Italy or in the Roman province of

Africa. Severinus himself refused to discuss his personal history prior to

arriving along the Danube in Noricum. However, he did mention experiences with eastern

desert monasticism and his Vita draws connections between Severinus and Saint

Anthony of Lérins (c 428-c 520) https://anastpaul.com/2021/12/28/saint-of-the-day-28-december-saint-anthony-of-lerins-c-428-c-520/

Little is known of his

origins. The source for information about him is the Commemoratorium Vitae

St Severini (511) by Eugippius (c 460-c 535), who was a disciple of

Severinus. In 511 Eugippius wrote to Paschasius and asked his venerated and

dear friend, who had great literary skill, to write a biography of St Severinus

from the accounts of the Saint which he (Eugippius) had put together in crude

and unartistic form. Paschasius, however, replied that the acts and miracles of

the Saint could not be described better than had done by Eugippius. This

Vita is available online at: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/severinus_02_text.htm

Severinus was a high-born

Roman living as an Hermit in the East. He was an ascetic in practice. He is

first recorded as travelling along the Danube in Noricum and Bavaria, preaching

Christianity, procuring supplies for the starving, redeeming captives and

establishing Monasteries at Passau and Favianae,

While the Western Empire

was falling apart, Severinus, thanks to his virtues and organisational skills,

committed himself to the religious and material care of the frontier peoples,

also taking care of their military defence. He organised refugee camps,

migrations to safer areas and food distribution.

Serverinus offered

practical leadership, as well as spiritual leadership. He was a tireless

preacher and a marvellous Miracle-worker – he miraculously multiplied food

reserves, cured the sick, cast out devils, commanded the elements of nature and

once even resurrected the dead.

The main theme of his

teaching was the value of penance. It was a propitious choice. The sufferings

of his people under the Germanic invasions were acute and, uniting them with

Christ’s sufferings for the reparation of sin and the conversion of sinners,

enabled them to find meaning and strength amid calamity. He also practiced what

he preached. In his constant barefoot journeying throughout Austria and

Bavaria, he ate only one meal a day and slept on a sack which he carried around

with him, wherever he happened to find himself at bedtime.

His efforts seem to have

won him wide respect, including that of the Germanic chieftain Odoacer.

Eugippius credits him with the prediction that Odoacer would become king of

Rome. However, Severinus warned that Odoacer would rule not more than fourteen

years.

Severinus also prophesied

the destruction of Asturis in Austria, by the Huns. When the people would not

heed his warning, he took refuge in Comagena. There he established refugee

centres for people displaced by the invasion and founded Monasteries to

re-establish spirituality and preserve learning in the stricken region.

He died in his monastic

cell at Favianae while singing Psalm 150. Six years after his death, his Monks

were driven from their Abbey and his body was taken to Italy, where it was at

first kept in the Castel dell’Ovo, Naples, then eventually interred at the

Benedictine Monastery rededicated to him, the Abbey of San Severino in the City

of Naples.

Author: AnaStpaul

Passionate Catholic.

Being a Catholic is a way of life - a love affair "Religion must be like

the air we breathe..."- St John Bosco Prayer is what the world needs

combined with the example of our lives which testify to the Light of Christ.

This site, which is now using the Traditional Calendar, will mainly concentrate

on Daily Prayers, Novenas and the Memorials and Feast Days of our friends in

Heaven, the Saints who went before us and the great blessings the Church

provides in our Catholic Monthly Devotions. This Site is placed under the

Patronage of my many favourite Saints and especially, St Paul. "For the

Saints are sent to us by God as so many sermons. We do not use them, it is they

who move us and lead us, to where we had not expected to go.” Charles Cardinal

Journet (1891-1975) This site adheres to the pre-Vatican II Catholic Church and

all her teachings. . PLEASE ADVISE ME OF ANY GLARING TYPOS etc - In June 2021 I

lost 100% sight in my left eye and sometimes miss errors. Thank you and I pray

all those who visit here will be abundantly blessed. Pax et bonum! View All Posts

St. Severinus, Abbot, and

Apostle of Noricum, or Austria

From his life, by

Eugippius his disciple, who was present at his death. See Tillemont, T. 16. p.

168. Lambecius Bibl. Vend. T. 1. p. 28. and Bollandus, p. 497.

A.D. 482

WE know nothing of the

birth or country of this saint. From the purity of his Latin, he was generally

supposed to be a Roman; and his care to conceal what he was according to the

world, was taken for a proof of his humility, and a presumption that he was a

person of birth. He spent the first part of his life in the deserts of the

East; but inflamed with an ardent zeal for the glory of God, he left his

retreat to preach the gospel in the North. At first he came to Astures, now

Stokeraw, situate above Vienna; but finding the people hardened in vice, he

foretold the punishment God had prepared for them, and repaired to Comagenes,

now Haynburg on the Danube, eight leagues westward of Vienna. It was not long

ere his prophecy was verified; for Astures was laid waste, and the inhabitants

destroyed by the sword of the Huns, soon after the death of Attila. St.

Severinus’s ancient host with great danger made his escape to him at Comagenes.

By the accomplishment of this prophecy, and by several miracles he wrought, the

name of the saint became famous. Favianes, a city on the Danube, twenty leagues

from Vienna, distressed by a terrible famine, implored his assistance. Saint

Severinus preached penance among them with great fruit, and he so effectually

threatened with the divine vengeance a certain rich woman, who had hoarded up a

great quantity of provisions, that she distributed all her stores amongst the

poor. Soon after his arrival, the ice of the Danube and the Ins breaking, the

country was abundantly supplied by barges up the rivers. Another time by his

prayers he chased away the locusts, which by their swarms had threatened with

devastation the whole produce of the year. He wrought many miracles; yet never

healed the sore eyes of Bonosus, the dearest to him of his disciples, who spent

forty years in almost continual prayer, without any abatement of his fervour.

The holy man never ceased to exhort all to repentance and piety; he redeemed

captives, relieved the oppressed, was a father to the poor, cured the sick,

mitigated, or averted public calamities, and brought a blessing wherever he

came. Many cities desired him for their bishop, but he withstood their

importunities by urging, that it was sufficient he had relinquished his dear

solitude for their instruction and comfort.

He established many

monasteries, of which the most considerable was one on the banks of the Danube,

near Vienna; but he made none of them the place of his constant abode, often

shutting himself up in an hermitage four leagues from his community, where he

wholly devoted himself to contemplation. He never eat till after sunset, unless

on great festivals. In Lent he eat only once a week. His bed was sackcloth

spread on the floor in his oratory. He always walked barefoot, even when the

Danube was frozen. Many kings and princes of the Barbarians came to visit him,

and among them Odoacer, king of the Heruli, then on his march for Italy. The

saint’s cell was so low that Odoacer could not stand upright in it. St.

Severinus told him that the kingdom he was going to conquer would shortly be

his; and Odoacer seeing himself, soon after master of Italy, sent honorable

letters to the saint, promising him all he was pleased to ask; but Severinus

only desired of him the restoration of a certain banished man. Having foretold

his death long before it happened, he fell ill of a pleurisy on the 5th of

January, and on the fourth day of his illness, having received the viaticum,

and arming his whole body with the sign of the cross, and repeating that verse

of the psalmist, Let every spirit praise the Lord, 1 he

closed his eyes and expired in the year 482. Six years after, his disciples,

obliged by the incursions of Barbarians, retired with his relics into Italy,

and deposited them at Luculano, near Naples, where a great monastery was built,

of which Eugippius, his disciple, and author of his life, was soon after made

the second abbot. In the year 910 they were translated to Naples, where to this

day they are honoured in a Benedictin abbey, which bears his name. The Roman

and other Martyrologies place his festival on this day, as being that of his

death.

A perfect spirit of

sincere humility is the spirit of the most sublime and heroic degree of

Christian virtue and perfection. As the great work of the sanctification of our

souls is to be begun by humility, so must it be completed by the same. Humility

invites the Holy Ghost into the soul, and prepares her to receive his graces;

and from the most perfect charity, which he infuses, she derives a new interior

light, and an experimental knowledge of God and herself, with an infused humility

far clearer in the light of the understanding, in which she sees God’s infinite

greatness, and her own total insufficiency, baseness, and nothingness, after

quite a new manner; and in which she conceives a relish of contempt and

humiliations as her due, feels a secret sentiment of joy in suffering them,

sincerely loves her own abjection, dependence, and correction, dreads the

esteem and praises of others, as snares by which a mortal poison may

imperceptibly insinuate itself into her affections, and deprive her of the

divine grace; is so far from preferring herself to any one, that she always

places herself below all creatures, is almost sunk in the deep abyss of her own

nothingness, never speaks of herself to her own advantage, or affects a show of

modesty in order to appear humble before men; in all good, gives the entire glory

to God alone, and as to herself, glories only in her infirmities, pleasing

herself in her own weakness and nothingness, rejoicing that God is the

great all in her and in all creatures.

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume I: January. The Lives of the

Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : https://www.bartleby.com/210/1/082.html

Hauptportal

der Lazaristenkirche in Wien-Währing mit einem bemerkenswerten Tympanon. Das

Relief zeigt Hl. Severin hilft Bedürftigen und Gefangenen. (dehio weiß

nichts über den Künstler)

Sculptures of Severin of

Noricum ; Lazaristenkirche, Währing ; Tympanums in Vienna ; Church portals in Vienna

Baring-Gould’s

Lives of the Saints – Saint Severinus, Priest, Apostle of Noricum

Article

(A.D 482)

[Roman Martyrology and

those of Germany. The life of Saint Severinus was written by his disciple,

Eugippius, in the year 511, as he states in a letter to Paschatius, the deacon.

The following life is extracted from Mr. Kingsley’s “Hermits,” with certain

necessary modifications. What has been once well done, the author is unwilling

to do again, and do in an inferior manner.]

In the middle of the

fifth century the province of Noricum (Austria, as we should now call it), was

the very highway of invading barbarians, the centre of the human Maelstrom, in

which Huns, Allemanni, Rugii, and a dozen wild tribes more, wrestled up and

down, and round the starving and beleaguered towns of what had once been a

happy and fertile province, each tribe striving to trample the other under

foot, and to march southward, over their corpses, to plunder what was still

left of the already plundered wealth of Italy and Rome. The difference of race,

of tongue, and of manners, between the conquered and their conquerors, was made

more painful by difference in creed. The conquering Germans and Huns were

either Arians or heathens. The conquered race (though probably of very mixed

blood), who called themselves Romans, because they spoke Latin, and lived under

the Roman law, were orthodox Catholics; and the miseries of religious persecution

were too often added to the usual miseries of invasion.

It was about the year 455

— 60. Attila, the great King of the Huns, who called himself — and who was —

“the Scourge of God,” was just dead. His empire had broken up. The whole centre

of Europe was in a state of anarchy and war; and the hapless Romans along the

Danube were in the last extremity of terror, not knowing by what fresh invader

their crops would be swept off up to the very gates of the walled towers, which

were their only defense; when there appeared among them, coming out of the

East, a man of God. Who he was he would not tell. His speech showed him to be

an African Roman — a fellow-countryman of Saint Augustine — probably from the

neighbourhood of Carthage. He had certainly at one time gone to some desert in

the East, zealous to learn “the more perfect life.” Severinus, he said, was his

name; a name which indicated high rank, as did the manners and the scholarship

of him who bore it. But more than his name he would not tell.” If you take me

for a runaway slave,” he said, smiling, “get ready money to redeem me with when

my master demands me back.” For he believed that they would have need of him;

that God had sent him into that land that he might be of use to its wretched

people. And certainly he could have come into the neighbourhood of Vienna, at

that moment, for no other purpose than to do good, unless he came to deal in

slaves.

He settled first at a

town, called by his biographer Casturis; and, lodging with the warden of the

church, lived quietly the hermit life. Meanwhile the German tribes were

prowling round the town; and Severinus, going one day into the church, began to

warn the priests and clergy, and all the people, that a destruction was coming

on them which they could only avert by prayer, and fasting, and the works of

mercy. They laughed him to scorn, confiding in their lofty Roman walls, which

the invaders — wild horsemen, who had no military engines — ^were unable either

to scale or batter down. Severinus left the town at once, prophesying, it was

said, the very day and hour of its fall. He went on to the next town, which was

then closely garrisoned by a barbarian force, and repeated his warning there:

but while the people were listening to him, there came an old man to the gate,

and told them how Casturis had been already sacked, as the man of God had

foretold; and going into the church, threw himself at the feet of Saint

Severinus, and said that he had been saved by his merits from being destroyed

with his fellow-townsmen.

Then the dwellers in the

town hearkened to the man of God, and gave themselves up to fasting, and

almsgiving, and prayer for three whole days.

And on the third day,

when the solemnity of the evening sacrifice was fulfilled, a sudden earthquake

happened, and the barbarians, seized with panic fear, and probably hating and

dreading — like all those wild tribes — confinement between four stone walls,

instead of the free open life of the tent and the stockade, forced the Romans

to open their gates to them, rushed out into the night, and, in their madness,

slew each other.

In those days a famine

fell upon the people of Vienna; and they, as their sole remedy, thought good to

send for the man of God from the neighbouring town. He went, and preached to

them, too, repentance and almsgiving. The rich, it seems, had hidden up their

stores of com, and left the poor to starve. At least Saint Severinus discovered

(by divine revelation, it was supposed), that a widow named Procula had done as

much. He called her out into the midst of the people, and asked her why she, a

noble woman and free-born, had made herself a slave to avarice, which is

idolatry. If she would not give her corn to Christ’s poor, let her throw it

into the Danube to feed the fish, for any gain from it she would not have.

Procula was abashed, and served out her hoards thereupon willingly to the poor;

and a little while afterwards, to the astonishment of all, vessels came down

the Danube laden with every kind of merchandise. They had been frozen up for

many days near Passau, in the thick ice of the river Enns : but the prayers of

God’s servant had opened the ice-gates, and let them down the stream before the

usual time.

Then the wild German

horsemen swept around the walls, and carried oif human beings and cattle, as

many as they could find. Severinus, like some old Hebrew prophet, did not

shrink from advising hard blows, where hard blows could avail. Mamertinus, the

tribune, or officer in command, told him that he had so few soldiers, and those

so ill-armed, that he dare not face the enemy. Severinus answered that they

should get weapons from the barbarians themselves; the Lord would fight for

them, and they should hold their peace: only if they took any captives they

should bring them safe to him. At the second milestone from the city they came

upon the plunderers, who fled at once, leaving their arms behind. Thus was the

prophecy of the man of God fulfilled. The Romans brought the captives back to

him unharmed. He loosed their bonds, gave them food and drink, and let them go.

But they were to tell their comrades that, if ever they came near that spot

again, celestial vengeance would fall on them, for the God of the Christians

fought from heaven in his servants cause.

So the barbarians

trembled, and went away. And the fear of Saint Severinus fell on all the Goths,

heretic Arians though they were and on the Rugii, who held the north bank of

the Danube in those evil days. Saint Severinus, meanwhile, went out of Vienna,

and built himself a cell at a place called ” At the Vineyards.” But some

benevolent impulse — divine revelation his biographer calls it — prompted him

to return, and build himself a cell on a hill close to Vienna, round which

other cells soon grew up, tenanted by his disciples. “There,” says his biographer,

“he longed to escape the crowds of men who were wont to come to him, and cling

closer to God in continual prayer: but the more he longed to dwell in solitude,

the more often he was warned by revelations not to deny his presence to the

afflicted people.” He fasted continually; he went barefoot even in the midst of

winter, which was so severe, the story con- tinues, in those days around

Vienna, that waggons crossed the Danube on the solid ice: and yet, instead of

being puffed-up by his own virtues, he set an example of humility to all, and

bade them with tears to pray for him, that the Saviour’s gifts to him might not

heap condemnation on his head.

Over the wild Rugii Saint

Severinus seems to have acquired unbounded influence. Their king, Flaccitheus,

used to pour out his sorrows to him, and tell him how the princes of the Goths

would surely slay him; for when he had asked leave of him to pass on into

Italy, he would not let him go. But Saint Severinus prophesied to him that the

Goths would do him no harm. Only one warning he must take: “Let it not grieve

him to ask peace even for the least of men.” The friendship which had thus

begun between the barbarian king and the cultivated Saint was carried on by his

son Feva: but his “deadly and noxious wife,” Gisa, who appears to have been a

fierce Arian, always, says his biographer, kept him back from clemency. One

story of Gisa’s misdeeds is so characteristic both of the manners of the time

and of the style in which the original biography is written, that I shall take

leave to insert it at length.

“The King Feletheus (who

is also Feva), the son of the afore-mentioned Flaccitheus, following his

father’s devotion, began, at the commencement of his reign, often to visit the

holy man. His deadly and noxious wife, named Gisa, always kept him back from

the remedies of clemency. For she, among the other plague-spots of her

iniquity, even tried to have certain Catholics re-baptized: but when her

husband did not consent, on account of his reverence for Saint Severinus, she

gave up immediately her sacrilegious intention, burdening the Romans,

nevertheless, with hard conditions, and commanding some of them to be exiled to

the Danube. For when one day, she, having come to the village next to Vienna,

had ordered some of them to be sent over the Danube, and condemned to the most

menial offices of slavery, the man of God sent to her, and begged that they

might be let go. But she, blazing up in a flame of fury, ordered the harshest

of answers to be returned. ‘I pray thee,’ she said, ‘servant of God, hiding

there within thy cell, allow us to settle what we choose about our own slaves.’

But the man of God hearing this, ‘I trust,’ he said, ‘in my Lord Jesus Christ,

that she will be forced by necessity to fulfill that which in her wicked will

she has despised.’ And forthwith a swift rebuke followed, and brought low the

soul of the arrogant woman. For she had confined in close custody certain

barbarian goldsmiths, that they might make regal ornaments. To them the son of

the aforesaid king, Frederick by name, still a little boy, had gone in, in

childish levity, on the very day on which the queen had despised the servant of

God. The goldsmiths put a sword to the child’s breast, saying, that if any one

attempted to enter, without giving them an oath that they should be protected,