Saint Pierre d'Alexandrie

Évêque et

martyr (+ 311)

Il dirigea la célèbre école théologique d'Alexandrie avant de devenir évêque. Lors de la persécution de 303, il préféra se cacher pour continuer à servir l'Eglise; ce qui lui fut reproché par un de ses prêtres qui créa ainsi une Eglise schismatique d'où sortira plus tard l'hérésie d'Arius. En 311, il fut arrêté et condamné à être décapité.

À Alexandrie, en 311, saint Pierre, évêque et martyr. Éminent en toutes sortes

de vertus, il eut soudain la tête tranchée par ordre de l'empereur Galère

Maxime, et fut la dernière victime de la grande persécution et comme le sceau

des martyrs. Avec lui on garde mémoire de trois évêques égyptiens, Hésychius,

Pachymius, et Théodore, qui souffrirent à Alexandrie également, avec beaucoup

d'autres, dans la même persécution.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/9348/Saint-Pierre-d-Alexandrie.html

Saint Pierre d'Alexandrie

Évêque et Martyr

(† 310)

Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie

nous est peu connu jusqu’à son élévation sur le siège épiscopal de cette ville.

Son zèle pour la Foi, à

une époque de persécutions continuelles, l’obligea de fuir ; mais il consola et

fortifia les Chrétiens dans les différentes contrées qu’il parcourut, et il

n’oublia pas son cher troupeau. Par d’éloquentes lettres pastorales, il

rappelait à ses brebis les grands devoirs de la vie chrétienne et la nécessité

de la persévérance.

La paix ayant reparu,

saint Pierre revint dans son Église, où il fut bientôt dénoncé par l’hérétique

Arius et jeté dans les fers. Il ne cessait, dans sa prison, d’encourager les

nombreuses victimes enfermées avec lui, de prier et de chanter les louanges de

Dieu.

Un jour qu’il priait avec

plus de ferveur, Notre-Seigneur lui apparut sous la forme d’un enfant tout

éclatant de lumière, et vêtu d’une belle tunique blanche fendue de haut en bas,

et il en tenait les bords comme pour cacher sa nudité. Saint Pierre, saisi de

frayeur, Lui dit :

« —Seigneur, qui Vous a

mis dans cet état ?

« —C’est Arius, répondit

Jésus, qui a divisé Mon Église et M’a ravi une partie des âmes que J’ai

rachetées de Mon sang. »

Peu de jours après,

plusieurs prêtres vinrent demander à l’évêque la grâce du misérable

hérésiarque, le croyant plein d’un repentir sincère : « Cessez, leur dit saint

Pierre averti par le Sauveur de l’hypocrisie d’Arius, cessez de plaider la

cause de ce misérable ; Dieu l’a maudit ; ses sentiments affectés cachent

l’impénitence et l’impiété ». Les prêtres cessèrent dès lors de se faire

illusion.

« Le temps de mon

supplice est proche, ajouta-t-il, je vous parle pour la dernière fois ; soyez

fermes dans la défense de la vérité et ne dégénérez pas de la vertu des Saints

». L’empereur, en effet, porta contre lui une sentence de mort ; mais les

fidèles, à cette nouvelle, accoururent à la prison pour le défendre, de sorte

que le tribun n’osa se présenter pour exécuter la sentence. Saint Pierre,

s’apercevant que ses chères ouailles retardaient son bonheur, donna aux

gardiens l’idée de faire un trou dans la muraille de la prison, du côté où il

n’y avait personne, et de le faire sortir par là. Son conseil fut mis à

exécution, et après avoir prié, demandant à Dieu la fin des persécutions, il

livra sa tête au bourreau le 26 novembre 310, saint Eusèbe étant pape et

Maximin empereur.

Au moment de son

supplice, une jeune Chrétienne entendit une voix céleste qui disait : « Pierre

le premier des Apôtres ; Pierre le derniers des évêques martyrs d’Alexandrie ».

Les Chrétiens recueillirent son corps et lui rendirent des honneurs solennels,

de sorte que la sépulture de ce vaillant pontife devint un vrai triomphe pour

lui et pour la religion chrétienne.

Saint Pierre d'Alexandrie

Évêque et Martyr

(† 310)

Saint Pierre d'Alexandrie

nous est peu connu jusqu'à son élévation sur le siège épiscopal de cette ville.

Son zèle pour la foi, à une époque de persécutions continuelles, l'obligea de

fuir; mais il consola et fortifia les chrétiens dans les différentes contrées

qu'il parcourut, et il n'oublia pas son cher troupeau. Par d'éloquentes lettres

pastorales, il rappelait à ses brebis les grands devoirs de la vie chrétienne

et la nécessité de la persévérance.

La paix ayant reparu,

Pierre revint dans son église, où il fut bientôt dénoncé par l'hérétique Arius

et jeté dans les fers. Il ne cessait, dans sa prison, d'encourager les

nombreuses victimes enfermées avec lui, de prier et de chanter les louanges de

Dieu. Un jour qu'il priait avec plus de ferveur, Notre-Seigneur lui apparut

sous la forme d'un enfant tout éclatant de lumière, et vêtu d'une belle tunique

blanche fendue de haut en bas, et il en tenait les bords comme pour cacher sa

nudité. Pierre, saisi de frayeur, Lui dit: "Seigneur, qui Vous a mis dans

cet état? — C'est Arius, répondit Jésus, qui a divisé Mon Église et M'a ravi

une partie des âmes que J'ai rachetées de Mon sang."

L'évêque prémunit son

clergé contre le traître et fut décapité peu de temps après.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : https://sanctoral.com/fr/saints/saint_pierre_d_alexandrie.html

SAINT PIERRE

D'ALEXANDRIE, ÉVÊQUE ET MARTYR.

26 NOVEMBRE

L'an 311. — Ce saint

évêque succéda sur le siège d'Alexandrie à un homme d'une grande piété,

appelé Théonos, ce qui ne l'empêcha pas d'acquérir lui-même, en Égypte et dans

toute l'Église, une haute réputation de science et de vertu. Pendant la cruelle

persécution de Maximien-Galère, il édifia tellement son peuple par sa patience,

que beaucoup de personnes se sentirent animées à mener une vie plus chrétienne

qu'elles ne faisaient auparavant. Ce fut lui qui le premier reconnut les

sentiments mauvais d'Arius, alors diacre d'Alexandrie. Il l'excommunia comme

favorisant le schisme des méléciens. Prisonnier pour la foi et condamné à

perdre la tête, le saint évêque fut visité par deux prêtres, Achillas et

Alexandre, qui venaient intercéder en faveur du diacre coupable. Mais il leur

répondit : « Cette nuit j'ai vu en songe Jésus-Christ couvert d'un vêtement

déchiré; et comme je lui demandais la cause de cet état dans lequel il se

trouvait, il m'a répondu : « Arius a déchiré mon vêtement, qui est l'Église. »

Le saint pontife ajouta, en parlant à ces prêtres, que tous deux deviendraient

évêques d'Alexandrie, et il les conjura de ne jamais recevoir Arius dans leur

communion, parce que le malheureux était tout à fait mort à Dieu. La suite ne

prouva que trop combien ces paroles étaient prophétiques. Pierre reçut la

couronne du martyre. On lui coupa la tête, la douzième année de son épiscopat,

le 26ème jour de novembre.

PRATIQUE. — C'est surtout

par 1a patience que nous édifierons utilement nos frères.

PRIÈRE. —Dieu tout-puissant, considérez notre faiblesse; et puisque le poids de nos péchés nous accable, faites que l'intercession du bienheureux Pierre, votre martyr et pontife, nous protège auprès de vous. Ainsi soit-il

SOURCE : https://jesus-passion.com/saint_pierre_alexandrie_FR.htm

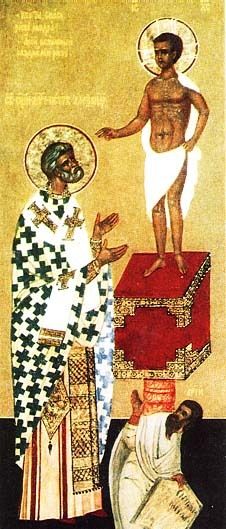

Константинополь.

985 г. Миниатюра Минология Василия II. Ватиканская библиотека. Рим.

The

execution of the patriarch Peter of Alexandria under the emperor Maximinus

Daia, depicted in the Menologion of Basil II, an illuminated

manuscript prepared for the emperor Basil II in c. 1000

Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie

: Théologien et Patriarche Orthodoxe

+Patriarche d'Alexandrie,

+ 310.

Date : 310

Fête : 26 novembre

Pape : saint Eusèbe

Dans l’histoire de la

chrétienté, de nombreux leaders religieux ont émergé, apportant avec eux un

héritage de foi, de sagesse et de dévotion. Parmi eux, saint Pierre

d’Alexandrie se distingue comme l’une des figures les plus éminentes du

christianisme primitif. En tant que Patriarche

d’Alexandrie, il a laissé un héritage durable, tant par ses enseignements

que par son exemple de vie. Dans cet article, nous plongerons dans la vie

fascinante de ce saint homme, explorant son rôle en tant que leader de l’Église

d’Alexandrie et son impact sur la foi chrétienne.

Jeunesse et Formation

Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie,

également connu sous le nom de Pierre le Martyr, est né au début du IIIe

siècle dans la ville égyptienne d’Alexandrie,

un important centre intellectuel et religieux à l’époque. Peu de détails sont

disponibles sur sa jeunesse, mais il est largement admis qu’il a reçu une

éducation religieuse solide, probablement dans les écoles chrétiennes établies

dans la région.

Sa vocation religieuse

s’est rapidement affirmée, et il a été ordonné prêtre avant de gravir les

échelons pour devenir évêque. Son ascension au sein de la hiérarchie

ecclésiastique était le reflet de son engagement envers la foi et sa capacité à

guider les fidèles dans leur cheminement spirituel.

Patriarche d’Alexandrie :

Leadership et Défense de la Foi

L’apogée de la carrière

de saint Pierre d’Alexandrie est survenue lorsqu’il a été élu Patriarche

d’Alexandrie, l’une des positions les plus prestigieuses de l’Église

copte. À cette époque, l’Église

d’Alexandrie jouait un rôle crucial dans la diffusion et la

préservation de la foi chrétienne, et le patriarche était chargé de diriger

cette communauté religieuse importante.

En tant que

patriarche, saint Pierre a fait preuve d’un leadership éclairé et

d’une ferme défense de la foi chrétienne. Il a été confronté à de nombreux

défis, notamment la persécution des chrétiens par les autorités romaines

et les controverses théologiques qui menaçaient l’unité de l’Église.

L’une des batailles les

plus célèbres de saint Pierre d’Alexandrie a été sa lutte contre

l’hérésie d’Arius, un prêtre alexandrin dont les enseignements

remettaient en question la nature divine de Jésus-Christ. Avec une éloquence

passionnée et une conviction inébranlable, saint Pierre a défendu la

doctrine de la Trinité et affirmé la pleine divinité de Jésus-Christ.

Sa contribution à la défaite de l’hérésie d’Arius a

été cruciale pour le développement ultérieur de la théologie chrétienne

orthodoxe.

Martyre et Héritage

Malheureusement, la vie

de saint Pierre d’Alexandrie a été marquée par le martyre. En 311, lors

des persécutions de l’empereur romain Maximin

Daïa, il a été arrêté et soumis à de terribles tortures pour sa foi. Malgré

les souffrances infligées, il est resté fidèle à ses convictions jusqu’à la

fin, refusant de renier sa foi en Jésus-Christ. Finalement, il a été exécuté,

devenant ainsi un martyr de la foi chrétienne.

L’héritage de saint

Pierre d’Alexandrie réside dans sa détermination indéfectible à défendre

la foi, même au prix de sa propre vie. Sa vie et son martyre ont inspiré de

nombreuses générations de chrétiens à rester fidèles à leurs croyances, même

dans les moments les plus sombres de l’histoire.

Conclusion

En conclusion, saint

Pierre d’Alexandrie demeure une figure emblématique du christianisme

primitif, dont l’héritage continue d’inspirer et de guider les croyants à

travers les âges. En tant que Patriarche

d’Alexandrie, il a incarné les valeurs de foi, de courage et de dévouement,

laissant un exemple durable de leadership ecclésiastique. Que son histoire nous

rappelle l’importance de rester fidèles à nos convictions, même lorsque les

temps sont difficiles.

À travers les siècles,

les récits de sa vie et de son martyre ont été transmis de génération en

génération, nourrissant la foi et l’espérance des chrétiens du monde entier.

Puissent ses enseignements continuer à résonner dans nos cœurs et à nous guider

sur le chemin de la vérité et de la lumière. Amen

Ses reliques

Les chrétiens, accourus

au bruit de cette exécution, recueillirent son sang et portèrent son corps au

cimetière des martyrs, où il y avait une chapelle bâtie en l’honneur de

Notre-Dame. Avant de le mettre en terre, ils le portèrent dans sa principale

basilique ; après l’avoir revêtu de ses habits pontificaux, ils le placèrent

dans la chaire de saint Marc, où, par une profonde humilité et une

révérence extrême pour ce bienheureux Évangéliste, il n’avait jamais voulu

s’asseoir pendant sa vie, se mettant seulement sur les degrés. Enfin,

nonobstant la persécution, ils le portèrent solennellement à son

sépulcre, avec des palmes et d’autres branches à la main, chantant

des cantiques de joie, comme s’ils eussent célébré un grand triomphe.

Godeau dit que

l’église de Grasse possède la plus grande partie de ses reliques, qui furent

apportées d’Égypte par un évêque nommé Bertrand, lorsque le siège était

encore à Antibes. Son peuple a souvent ressenti à son tombeau le

pouvoir de son intercession, et sa mémoire a toujours été vénérable

aux fidèles.

Rien n’excuse d’une faute

que l’on commet par ignorance des choses qu’on doit savoir par état 1° D’après

cette règle, on comprend la nécessité où se trouve chacun de bien s’instruire

des devoirs de son état, de se les rappeler sans cesse pour ne point les

oublier. 2° On sent combien est grande la responsabilité de certaines

professions, du prêtre surtout, du magistrat, du médecin.

Anecdotes

Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie a

laissé un héritage riche en anecdotes et en récits qui illustrent sa piété, son

courage et sa détermination. Voici quelques-unes de ces anecdotes qui ont

survécu à travers les siècles :

Sa défense de la foi lors

du Concile de Nicée

Lors du célèbre Concile de Nicée en 325, au cours duquel les évêques se

sont réunis pour débattre de la doctrine chrétienne, saint Pierre

d’Alexandrie aurait été l’un des principaux défenseurs de la pleine

divinité de Jésus-Christ contre les enseignements hérétiques d’Arius.

Son éloquence et sa fermeté dans la foi ont joué un rôle crucial dans la

formulation de la confession de foi qui affirmait la consubstantialité du Fils

avec le Père.

Sa vision prophétique du

martyre

Avant son arrestation et

son martyre sous l’empereur Maximin

Daïa, saint Pierre d’Alexandrie aurait eu une vision prophétique

de son destin. Selon la tradition, il aurait prédit son propre martyre et

aurait accepté avec résignation le sort qui l’attendait, témoignant ainsi de sa

foi inébranlable en dépit des dangers qui le guettaient.

Son pardon aux

persécuteurs

Malgré les tortures et

les souffrances qu’il a endurées aux mains de ses persécuteurs, saint

Pierre d’Alexandrie aurait été capable de pardonner à ceux qui l’ont

opprimé. Cette capacité à pardonner à ses ennemis, même au moment de son

martyr, témoigne de sa profonde compréhension des enseignements de Jésus sur

l’amour et le pardon.

Son influence sur la

conversion de ses bourreaux

Il est dit que certains

des bourreaux chargés de le torturer et de le mettre à mort ont été tellement

impressionnés par sa foi et sa résilience qu’ils se sont convertis au

christianisme eux-mêmes. Cette transformation des cœurs témoigne de la

puissance de son témoignage et de son martyre.

Sa postérité spirituelle

Bien après sa mort, saint

Pierre d’Alexandrie a continué à exercer une influence spirituelle sur les

fidèles chrétiens. De nombreux récits de guérisons miraculeuses et

d’interventions divines attribuées à son intercession ont été rapportés au fil

des siècles, renforçant ainsi sa réputation de saint homme et d’intercesseur puissant

auprès de Dieu.

Oraison

O Dieu tout-puissant,

jetez les yeux de votre miséricorde sur notre faiblesse ; et, parce que nous

sommes accablés sous le poids de nos péchés, faites que nous soyons fortifiés

par la glorieuse intercession du bienheureux Pierre, votre martyr et

pontife. Par Jésus-Christ Notre-Seigneur. Ainsi soit-il.

SOURCE : https://www.laviedessaints.com/saint-pierre-dalexandrie-%E2%9C%9E-310/

Saint Pierre d'Alexandrie

Martyr à Alexandrie le 24

novembre 311, Fête à Rome au XIIème siècle, mais dès le IXème en Italie du sud

sous influence byzantine.

Leçon des Matines (avant

1960)

Neuvième leçon. Pierre,

Évêque d’Alexandrie, après Théonas, homme d’une éminente sainteté, fut, par

l’éclat de ses vertus et de sa doctrine, non seulement la lumière de l’Égypte,

mais encore celle de toute l’Église de Dieu. Pendant la persécution de Maximin

Galère, il supporta la rigueur de ces temps-là avec tant de courage, que

beaucoup de Chrétiens, témoins de son admirable patience, firent de grands

progrès dans la pratique des vertus. Il fut le premier à séparer de la

communion des fidèles, Arius, Diacre d’Alexandrie, parce qu’il favorisait le

schisme de Mélèce. Lorsque Pierre eut été condamné par Maximin à la peine

capitale, les Prêtres Achillas et Alexandre allèrent le trouver dans sa prison,

pour intercéder auprès de lui en faveur d’Arius ; mais il leur répondit que,

pendant la nuit, Jésus lui était apparu, portant une tunique déchirée, et que,

lui en ayant demandé la cause, le Sauveur lui avait dit : « C’est Arius qui a

déchiré ainsi mon vêtement, qui est l’Église. » Puis leur ayant prédit qu’ils

lui succéderaient dans l’épiscopat, il leur défendit de recevoir dans leur

communion Arius, qu’il savait mort devant Dieu. Les événements ne tardèrent pas

à montrer que cette révélation était vraiment de Dieu. Enfin, la douzième année

de son épiscopat, le sixième jour des calendes de décembre, ayant eu la tête

tranchée, il alla recevoir la couronne du martyre.

Dom Guéranger,

l’Année Liturgique

Pierre, évêque

d’Alexandrie après saint Théonas, fut par sa science et sa sainteté la gloire

de l’Égypte et la lumière de toute l’Église de Dieu. Son courage fut tel dans

l’atroce persécution excitée par Maximien Galère, que le spectacle d’une si

admirable patience fortifia la vertu d’un grand nombre de chrétiens. Ce fut lui

qui sépara le premier de la communion des fidèles Arius, diacre d’Alexandrie, à

cause de l’appui qu’il donnait au schisme des Mélétiens. . Honorons et prions

le grand évêque dont l’Église fait mémoire en ce jour. On le nomma longtemps,

comme par excellence, Pierre le Martyr ; jusqu’à ce qu’au XIIIe siècle, un

autre Pierre Martyr, illustre lui-même entre tous, fit qu’on appela désormais

son glorieux homonyme Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Saint pierre, le dernier

martyr, celui qui scella la persécution de Dioclétien à Alexandrie (+ 311),

ainsi que les Grecs le saluent d’un titre d’honneur : sceau et terme de la

persécution, est mentionné pour la première fois dans le martyrologe syriaque

et, par la suite, par tous les Orientaux, le 24 novembre. Le martyrologe

hiéronymien le commémore au contraire aujourd’hui. Son culte, dans l’antiquité,

rencontra une grande faveur, si bien qu’il était très populaire même à

Antioche. Une si grande célébrité est due, en partie, à la place très

importante qu’occupait ce martyr comme patriarche d’Alexandrie, en partie à ses

qualités personnelles, et comme directeur du didascaleion d’Alexandrie, et

comme auteur sacré. Il est certain que Pierre fut « un splendide exemplaire

d’évêque » selon l’attestation d’Eusèbe [1].

Les Syriens ont tiré des

Actes mêmes de saint Pierre un titre glorieux qu’ils lui attribuent ; ils

l’appellent : celui qui passa à travers le mur percé. Les Actes racontent en

effet que le peuple d’Alexandrie montait la garde autour de la prison afin

qu’aucun des soldats païens ne se hasardât à exécuter la sentence capitale

prononcée contre le Patriarche. Que faire ? Il y avait à redouter que la milice

se vengeât du peuple soulevé ; alors le saint Pasteur, pour sauver son

troupeau, résolut de s’offrir spontanément à la cruauté des bourreaux. Il fit

donc savoir secrètement au tribun qu’au cours de la nuit suivante il

indiquerait, par des coups, le point où il fallait percer la muraille pour

ouvrir un passage à l’intérieur de la prison. Cette nuit-là, par bonheur, un

orage avec éclairs, tonnerre et une forte averse, détourna l’attention des

sentinelles chrétiennes, de telle sorte que les soldats du tribun purent, sans

être dérangés, pratiquer une brèche dans la muraille de la prison. Le saint

Patriarche passa donc à travers le mur entr’ouvert et se laissa conduire par

les soldats au lieu même que la tradition indiquait comme celui du martyre de

saint Marc. Là enfin il fut décapité, et les fidèles ensevelirent son cadavre.

La messe Státuit est du

Commun.

[1] Hist.Eccl., IX, 6, 2.

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

Saint Pierre, évêque

d’Alexandrie, martyr en 311. — Comme il était en prison, des prêtres vinrent

intercéder auprès de lui pour Arius, l’hérétique qu’il avait condamné, et le

fondateur d’une des sectes les plus importantes dans l’histoire de l’Église.

Mais saint Pierre leur répondit que, pendant la nuit, Jésus lui était apparu

portant une robe déchirée ; et comme il lui en demandait la raison, le Seigneur

lui avait dit : “Arius a déchiré mon vêtement, qui est mon Église.” Pratique :

Nous pouvons nous appliquer cette parole : si l’Église est le vêtement du

Christ, nous sommes les parties de ce vêtement ; l’hérétique déchire, le

pécheur souille le vêtement du Christ. Nous voulons, par une vie riche en

vertus, orner le vêtement du Christ de perles et de pierres précieuses.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/26-11-St-Pierre-d-Alexandrie

Profile

Suffered in the persecution of Decius,

but survived. Renowned for his knowledge of science and the Bible. Head of

the catechetical school at Alexandria, Egypt. Bishop of Alexandria in 300.

Opposed extreme Origenism.

May have been the first to deal with the Arian heresy.

During the Diocletian persecution,

Peter fled the area with many of his flock. Criticized by many for being

lenient and forgiving to Christians who

had renounced their faith during the persecutions.

However, when a rogue bishop usurped

Peter’s position, the Meletian schism broke

out in his clergy, and Peter had to return from hiding to deal with it.

Peter excommunicated Meletius

and convened a synod of bishops to

condemn the schism.

His writings were

used in the Council

of Ephesus and the Council

of Chalcedon.

Bishop Peter

was martyred with Father Dio, Father Ammonius,

and Father Faustus,

three of his priests,

in the persecutions of Gaius

Valerius Galerius Maximinus. As he was the last Christian martyred in Alexandria by

civil authorities, the Coptic Church calls him “the seal and complement of

the martyrs“.

Born

at Alexandria, Egypt

martyred in 311 at Alexandria, Egypt

initially buried in

an Alexandria martyr‘s

cemetery

most relics later

enshrined in a church at Grasse, France

embracing his executioner

with Christ appearing to

him as a child in rags (from a scene in the Acts of the Martyrdom of Saint

Peter)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by F J Bacchus

Lives of the Saints, by Father Alban Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

websites

in nederlandse

MLA

Citation

“Saint Peter of

Alexandria“. CatholicSaints.Info. 21 April 2022. Web. 23 May 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-of-alexandria-25-november/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-peter-of-alexandria-25-november/

Book of Saints –

Peter of Alexandria

(Saint) Bishop, Martyr (November

26) (4th

century) A learned and holy Prelate who governed the great Church of Alexandria in Egypt for

twelve years in very troubled times. He had to face the dangerous schism of

Meletius among his own clergy at the very time when the comforting and guiding

of Christians in

peril of death at

the hands of heathen persecutors called for the exercise of all his energies.

He seems to have been the first to detect the incipient heresy of Arius. Saint Peter

was put to death by

order of the Caesar Maximin Daza, together with other Christians (A.D. 311),

and was succeeded by Saint Alexander,

the predecessor of the great Saint Athanasius.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate. “Peter

of Alexandria”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

16 October 2016. Web. 23 May 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-peter-of-alexandria/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-peter-of-alexandria/

New

Catholic Dictionary – Saint Peter of Alexandria

Martyr. Bishop of

Alexandria. He suffered in the Decian persecution and was at one time head of

the famous catechetical school at Alexandria. He probably initiated the

reaction there against extreme Origenism. When during the Diocletian

persecution Peter left Alexandria for concealment, the Meletian schism broke

out among his own clergy, and he had this to contend with at a time when it was

all he could do to comfort and guide the captive Christians. He was probably

the first to discover the heresy of Arius. On his return to Alexandria he

convened a synod of bishops against Meletius, Bishop of Lycopolis, who had

usurped his authority. Soon after this he was martyred at Alexandria in 311 at

the command of Maximinus Daja, and was buried in the cemetery for martyrs. Most

of his relics were enshrined in a church at Grasse, France. Feast, Roman

Calendar, 26

November.

MLA

Citation

“Saint Peter of

Alexandria”. New Catholic Dictionary. CatholicSaints.Info. 10

October 2010.

Web. 23 May 2025.

<http://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-peter-of-alexandria/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-peter-of-alexandria/

St. Peter of Alexandria

Feastday: November 25

Death: 311

Bishop of Alexandria from

300. A native of Alexandria, Egypt, Peter survived the persecutions of

Emperor Diocletian and

served as a confessor for

the suffering Christians. Made head of the famed Catechetical School of

Alexandria, he was a vigorous opponent of Origenism before receiving

appointment as bishop. He composed a set of rules by which those who had lapsed

might be readmitted to the faith after

appropriate penance, a settlement which was not to the liking of extremists of

the community. Thus, in 306 when the persecutions began again, Peter was forced

to flee the city. The partisans of Melitius, Peter’s chief critic, installed

their favorite as bishop of

Alexandria, thereby starting the Melitian Schism which

troubled the see for many years. Peter returned to Alexandria in

311 after a lull in the persecutions, but was soon arrested and beheaded by

Roman officials acting on the decree of

Emperor Maximian. He is called the “seal and complement of martyrs” as he was

the last Christian slain

by Roman authorities. Eusebius of Caesarea described him as “a model bishop,

remarkable for his virtuous life and

his ardent study of the Scriptures.” He is much revered by the Coptic

Christians, although since 1969, his cult has been confined to local calendars

in the Catholic Church.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=5376

PETER OF ALEXANDRIA, ST.

Bishop (300–311), martyr;

d. Alexandria, Egypt, Nov. 25, 311. After serving as head of the catechetical

school at Alexandria, Peter succeeded Theonas as bishop c. 300, and

was "beheaded in the ninth year of the persecution" (eusebius, Hist.

eccl. 7.32.31). This intrepid churchman reflected the milder school in his

attitude toward the lapsi. While Peter was in hiding during the persecution of

diocletian (303), Meletius, bishop of Lycopolis, assumed his episcopal rights.

Meletius, whose view of the lapsi was more rigid, was declared

excommunicate by a synod in 306, deposed, and banished to Palestine until 311;

but the meletian schism of which he was the cause continued for several

centuries after his death.

Peter's most important

writing is the Paschal epistle; it contains 15 canons for the reconciliation of

the lapsed (c. 306). Those who denied the faith under torture are assigned

a 40-day fast for three years; those who lapsed without torture are assigned an

additional year; those who obtained certificates of sacrifice are given a

six-month penance; those who fell but later confessed are forgiven, but the

clergy are not to be reinstated; those who sacrificed wealth and fled into

exile are forgiven (Patrologia Graeca 18:468–508).

Peter's works exist

mostly in Greek and Coptic fragments, and include treatises against origen and

origenism, On the Godhead (quoted at ephesus in 431), and a Letter on

the Meletian schism. He was a courageous and enlightened churchman, and despite

the tragic effects of the Meletian schism, his canons were a milestone in

primitive Church discipline. The Acts of the Martyrdom of St. Peter of

Alexandria (Latin, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic) is not authentic.

Feast: Nov. 26.

Bibliography: Peter

of Alexandria, Patrologia Graeca 18:449–522. J. Quasten, Patrology 2:113–118. B. Altaner, Patrology 239–240. G. Fritz, Dictionnaire de théologie

catholique 12.2:1802–04. F. Kettler, Paulys Readenzyklopädie der

klassichen Altertumswissenschaft 12.2 (1938) 1281–88. T. Y. Malaty, Pope

Peter of Alexandria: The Deans of the School of Alexandria (Jersey

City, N.J. 1994). W. Telfer, "St. Peter of Alexandria and Arius," Analecta

Bollandiana 67 (1949) 117–130; Harvard Theological Review 48

(1955) 227–237, and Meletius. M. Richard, Mélanges de science religeuse 3

(1946) 357–358, Christology. H. I. Bell and W. E. Crum, eds., Jews and

Christians in Egypt (London 1924). É. Amann, Dictionnaire de théologie

catholique 10.1:531–536.

AD

[H. Musurillo]

New Catholic Encyclopedia

St. Peter of Alexandria

Local commemorations of

the fourth-century martyr Saint Peter of Alexandria will take place on Nov. 25

and 26. Although his feast day in the Western tradition (on the latter date) is

no longer a part of the Roman Catholic Church’s universal calendar, he remains

especially beloved among Catholic and Orthodox Christians of the Egyptian

Coptic tradition.

Tradition attests that

the Egyptian bishop was the last believer to suffer death at the hands of Roman

imperial authorities for his faith in Christ. For this reason, St. Peter of

Alexandria is known as the “Seal of the Martyrs.” He is said to have undertaken

severe penances for the sake of the suffering Church during his lifetime, and

written letters of encouragement to those in prison, before going to his death

at the close of the “era of the martyrs.”

Both the date of Peter’s

birth, and of his ordination as a priest, are unknown. It is clear, however,

that he was chosen to lead Egypt’s main Catholic community in the year 300

after the death of Saint Theonas of Alexandria. He may have previously been in

charge of Alexandria’s well-known catechetical school, an important center of

religious instruction in the early Church. Peter’s own theological writings were

cited in a later fifth-century dispute over Christ’s divinity and humanity.

In 302, the Emperor

Diocletian and his subordinate Maximian attempted to wipe out the Church in the

territories of the Roman Empire. They used their authority to destroy Church

properties, imprison and torture believers, and eventually kill those who

refused to take part in pagan ceremonies. As the Bishop of Alexandria, Peter

offered spiritual support to those who faced these penalties, encouraging them

to hold to their faith without compromise.

One acute problem for the

Church during this period was the situation of the “lapsed.” These were

Catholics who had violated their faith by participating in pagan rites under

coercion, but who later repented and sought to be reconciled to the Church.

Peter issued canonical directions for addressing their various situations, and

these guidelines became an important part of the Eastern Christian tradition

for centuries afterward.

Around the year 306,

Peter led a council that deposed Bishop Meletius of Lycopolis, a member of the

Catholic hierarchy who had allegedly offered sacrifice to a pagan idol. Peter

left his diocese for reasons of safety during some portions of the persecution,

giving Meletius an opening to set himself up as his rival and lead a schismatic

church in the area.

The “Meletian schism”

would continue to trouble the Church for years after the death of Alexandria’s

legitimate bishop. Saint Athanasius, who led the Alexandrian Church during a

later period in the fourth century, claimed that Meletius personally betrayed

Peter of Alexandria to the state authorities during the Diocletian persecution.

Although Diocletian

himself chose to resign his rule in in 305, persecution continued under

Maximinus Daia, who assumed leadership of the Roman Empire’s eastern half in

310. The early Church historian Eusebius attests that Maximinus, during an

imperial visit to Alexandria, unexpectedly ordered its bishop to be seized and

killed without imprisonment or trial in 311. Three priests – Faustus, Dio, and

Ammonius – were reportedly beheaded along with him.

St. Peter of Alexandria’s

entry in the “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria” (a

volume first compiled by a Coptic Orthodox bishop in the 10th century)

concludes with a description of the aftermath of his death.

“And the city was in

confusion, and was greatly disturbed, when the people beheld this martyr of the

Lord Christ. Then the chief men of the city came, and wrapped his body in the

leathern mat on which he used to sleep; and they took him to the church … And,

when the liturgy had been performed, they buried him with the fathers. May his

prayers be with us and all those that are baptized!”

SOURCE : https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/st-peter-of-alexandria-696

St. Peter of Alexandria

Became Bishop of Alexandria in

300; martyred Nov.,

311. According to Philip of Sidetes he was at one time head

of the famous catechetical school at Alexandria.

His theological importance

lies in the fact that he marked, very probably initiated, the reaction

at Alexandria against extreme Origenism.

When during the Diocletian persecution Peter left Alexandria for

concealment, the Meletian schism broke

out. There are three different accounts of this schism:

(1) According to three Latin documents (translation from

lostGreek originals) published by Maffei, Meletius (or Melitius), Bishop of Lycopolis,

took advantage of St. Peter'sabsence to usurp

his patriarchal functions, and contravened the canons by consecrating bishops to sees

notvacant, their occupants being in prison for

the Faith. Four of them remonstrated, but Meletius took no heed

of them and actually went to Alexandria, where, at the instigation of one

Isidore, and Arius the future heresiarch, he set aside those left in

charge by Peter and appointed others. Upon this Peter excommunicated him.

(2) St.

Athanasius accuses Meletius not only of turbulent and schismatical conduct,

but of sacrificing, and denouncingPeter to the emperor. There is no

incompatibility between the Latin documents and St. Athanasius,

but the statement that Meletius sacrificed must be received with

caution; it was probably based upon rumour arising out of

the immunity which he appeared to enjoy. At all events nothing was

heard about the charge at the Council

of Nicæa. (3) According to St.

Epiphanius (Haer., 68), Meletius and St.

Peter quarrelled over the reconciliation of the lapsi,

the former inclining to sterner views. Epiphanius probably derived

his information from a Meletiansource, and his story is full

of historical blunders. Thus, to take one example, Peter is

made a fellow-prisoner ofMeletius and is martyred in prison.

According to Eusebius his martyrdom was

unexpected, and therefore not preceded by a term of imprisonment.

There are extant a

collection of fourteen canons issued by Peter in the third

year of the persecution dealing

chiefly with the lapsi, excerpted

probably from an Easter Festal Epistle.

The fact that they were ratified by theCouncil of Trullo, and thus

became part of the canon law of the Eastern

Church, probably accounts for their preservation. Many manuscripts contain

a fifteenth canon taken from writing on the Passover.

The cases of different kinds of lapsi were

decided upon in these canons.

The Acts of

the martyrdom of St.

Peter are too late to have any historical value. In them is the

story of Christappearing to St. Peter with His garment rent,

foretelling the Arian schism.

Three passages from "On the Godhead", apparently written

against Origen's subordinationist

views, were quoted by St. Cyril at the Council of Ephesus. Two

further passages (in Syriac) claiming to be from the same book, were

printed by Pitra in "Analecta Sacra", IV, 188; their genuineness is doubtful. Leontius

of Byzantium quotes a passage affirming the

two Naturesof Christ from a work on "The Coming of

Christ", and two passages from the first book of a treatise against the

view that the soul had existed and sinned before

it was united to the body. This treatise must have been written against Origen.

Very important are seven fragments preserved in Syriac (Pitra, op.

cit., IV, 189-93) from another work on the Resurrection,

in which the identity of the risen with the earthly body is

maintained against Origen.

Five Armenian fragments

were also published by Pitra (op. cit., IV, 430 sq.). Two of these

correspond with one of the doubtful Syriac fragments.

The remaining three are probably Monophysite forgeries (Harnack,

"Altchrist. Lit.", 447). A fragment quoted by the Emperor

Justinian in his Letter to the Patriarch Mennas,

purporting to be taken from a Mystagogia of St. Peter's, is probably

spurious (see Routh, "Reliq. Sac.", III, 372; Harnack, op. cit.,

448). The "Chronicon Paschale" gives a long extract from a supposed

writing of Peter on the Passover.

This is condemned as spurious by a reference to St. Athanasius (which

editors often suppress) unless, indeed, the reference is an interpolation. A

fragment first printed by Routh from a Treatise "On

Blasphemy" is generally regarded as spurious. A Coptic fragment

on the keeping of Sunday, published by Schmidt (Texte und Untersuchung.,

IV) has been ruled spurious by Delehaye, in whose

verdict critics seem to acquiesce. Other Copticfragments have

been edited with a translation by Crum in the "Journal of Theological

Studies" (IV, 287 sqq.). Most of these come from the same manuscript as

the fragment edited by Schmidt. Their editor says: "It would be difficult

to maintain the genuineness of these texts after Delehaye's

criticisms (Anal. Bolland., XX, 101), thoughcertain of the passages, which

I have published may indicate interpolated, rather than wholly apocryphalcompositions."

Sources

ROUTH, Reliq. Sac., III,

319-72, gives most of the passages attributed to St. Peter. A translation of

many of these, as well as of the martyrdom, will be found in CLARKE, Ante-Nicene

Christ. Library, in vol. containing works of METHODIUS. For the Meletian

schism: HEFELE, Hist. of Councils, tr. I, 341 sq. The best editions of the

Canons is LAGARDE, Reliq. Juris Eccles., 63-73. The latest edition of the

martyrdom is VITEAU, Passions des saints Ecaterine et Pierre d'Alexandrie,

Barbara et Amysia (Paris, 1897). See HARNACK, Altchrist. Lit.,

443-49; and Chronologie, 71-75. BARDENHEWER, Gesch. d. altkirch. Lit., II,

203 sq. RADFORD, Three Teachers of Alexandria: Theognostus, Pierius and

Peter (Cambridge, 1908).

Bacchus, Francis

Joseph. "St. Peter of Alexandria." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1911. 26 Nov.

2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11771a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by WGKofron. With thanks to Fr.

John Hilkert and St. Mary's Church, Akron, Ohio.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11771a.htm

Peter Martyr of

Alexandria BM (RM)

Born at Alexandria, Egypt; died 311. Peter was a young 'confessor' during the

Decian persecution. Later he became known for his extraordinary virtue, skill

in the sciences, and learning and knowledge of Scripture. Peter was named head

of the catechetical school in Alexandria, and in 300 was elected patriarch of

the city to succeed Saint Theonas.

As bishop Saint Peter

fought Arianism and extreme Origenism and spent the last nine years of his

episcopate encouraging his flock to stand fast against the persecution of

Christians launched by Emperor Diocletian. As the fury of the persecutions

increased, Peter, according to Eusebius, heightened the rigor of his penances.

He perceived the need for some rules that would lovingly, but sternly, welcome

back into the Christian fold those who--under persecution and even torture--had

lapsed from the faith and then wanted to return. These rules were eventually

accepted throughout the Eastern Church; but others criticized Peter of

Alexandria for being far too lenient.

One of those who

apostatized was Bishop Meletius of Lycopolis in the Thebaid. Meletius was

convicted by a council of having sacrificed to idols and other crimes. The

sentence was deposition.

About that time Peter was

forced into hiding; whereupon Meletius installed himself at the head of a

discontent party. He began to usurp Peter's authority as metropolitan and, in

order to justify his disobedience, he accused Peter in writing of treating the

lapsi too leniently. Peter excommunicated Meletius, but still hoped to

reconcile him. His letter of excommunication reads: "Now take heed to this

and hold no communion with Meletius until I meet him, in company with some wise

and discreet men, to find out what he has been plotting." Nevertheless,

this led to a schism in the Egyptian church that lasted for several

generations.

Peter continued

administering his see from hiding and returned to Alexandria when the

persecutions were temporarily suspended. In 311, Emperor Maximinus Daia

unexpectedly renewed the persecution. Peter was arrested and then executed--the

last Christian martyr put to death in Alexandria by the authorities. Martyred

with him were three of his priests: Dio, Ammonius, and Faustus, who appears to

have been the companion of Saint Dionysius during his exile 60 years earlier.

The Coptic Church calls him 'the seal and complement of the martyrs,' because

he was the last Christian to die for the faith before Constantine granted

religious toleration throughout the empire.

Eusebius calls him 'an

inspired Christian teacher . . . a worthy example of a bishop, both for the

goodness of his life and his knowledge of the Scriptures.' Among Peter's

fragmentary writings are some regulations of great interest, drawn up in 306;

they deal with the treatment of those Christians who in varying degrees had

failed under persecution. Portions of a book he wrote on the Divinity are

preserved in the councils of Ephesus (Act. 1 and 7) and Chalcedon (Act. 1).

Several related items of interest are available on the Internet: The Genuine

Acts of Peter, The Canonical Epistle, and a document entitled Peter, Archbishop

of Alexandria (Attwater, Attwater2, Benedictines, Bentley, Coulson, Delaney,

Husenbeth).

Saint Peter is depicted

as a bishop enthroned between angels in Sienese paintings. Sometimes he is

shown (1) holding the city of Siena while wearing a tiara rather than a mitre;

(2) with Christ appearing to him as a child in rags; or (3) embracing his

executioner. He is the patron of Siena, Italy (Roeder).

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saints-of-the-day-peter-martyr-of-alexandria/

EUSEBIUS 1 calls this great prelate the excellent doctor of the Christian religion, and the chief and divine ornament of bishops; and tells us that he was admirable both for his extraordinary virtue, and for his skill in the sciences, and profound knowledge of the holy scriptures. In the year 300 he succeeded Theonas in the see of Alexandria, being the sixteenth archbishop from St. Mark; he governed that church with the highest commendation, says the same historian, during the space of twelve years, for the nine last of which he sustained the fury of the most violent persecutions carried on by Dioclesian and his successors. Virtue is tried and made perfect by sufferings; and Eusebius observes that the fervour of our saint’s piety and the rigour of his penance increased with the calamities of the church. That violent storm which affrighted and disheartened several bishops and inferior ministers of the church, did but awake his attention, inflame his charity, and inspire him with fresh vigour. He never ceased begging of God for himself and his flock necessary grace and courage, and exhorting them to die daily to their passions, that they might be prepared to die for Christ. The confessors he comforted and encouraged by word and example, and was the father of many martyrs who sealed their faith with their blood. His watchfulness and care were extended to all the churches of Egypt, Thebais or Upper Egypt, and Lybia, which were under his immediate inspection. Notwithstanding the activity of St. Peter’s charity and zeal, several in whom the love of this world prevailed, basely betrayed their faith, to escape torments and death. Some, who had entered the combat with excellent resolutions, and had endured severe torments, had been weak enough to yield at last. Others bore the loss of their liberty and the hardships of imprisonment, who yet shrank at the sight of torments, and deserted their colours when they were called to battle. A third sort prevented the inquiries of the persecutors, and ran over to the enemy before they had suffered any thing for the faith. Some seeking false cloaks to palliate their apostacy, sent heathens to sacrifice in their name, or accepted of attestations from the magistrates, setting forth that they had complied with the imperial edict, though in reality they had not. These different degrees of apostacy were distinctly considered by the holy bishop, who prescribed a suitable term of public penance for each in his canonical epistle. 2

Among those who fell during this storm, none was more considerable than Meletius, bishop of Lycopolis in Thebais. That bishop was charged with several crimes; but apostacy was the main article alleged against him. St. Peter called a council, in which Meletius was convicted of having sacrificed to idols, and of other crimes, and sentence of deposition was passed against him. The apostate had not humility enough to submit, or to seek the remedy of his deep wounds by condign repentance, but put himself at the head of a discontented party which appeared ready to follow him to any lengths. To justify his disobedience, and to impose upon men by pretending a holy zeal for discipline, he published many calumnies against St. Peter and his council; and had the assurance to tell the world that he had left the archbishop’s communion, because he was too indulgent to the lapsed in receiving them too soon and too easily to communion. Thus he formed a pernicious schism which took its name from him, and subsisted a hundred and fifty years. The author laid several snares for St. Peter’s life, and though, by an overruling providence, these were rendered ineffectual, he succeeded in disturbing the whole church of Egypt with his factions and violent proceedings: for he infringed the saint’s patriarchal authority, ordained bishops within his jurisdiction, and even placed one in his metropolitical see. Sozomen tells us, these usurpations were carried on with less opposition during a certain time when St. Peter was obliged to retire, to avoid the fury of the persecution. Arius, who was then among the clergy of Alexandria, gave signs of his pride and turbulent spirit by espousing Meletius’s cause as soon as the breach was open, but soon after quitted that party, and was ordained deacon by St. Peter. It was not long before he relapsed again to the Meletians, and blamed St. Peter for excommunicating the schismatics, and forbidding them to baptize. The holy bishop, by his knowledge of mankind, was by this time convinced that pride, the source of uneasiness and inconstancy, had taken deep root in the heart of this unhappy man; and that so long as this evil was not radically cured, the wound of his soul was only skinned over by a pretended conversion, and would break out again with greater violence than ever. He, therefore, excommunicated him, and could never be prevailed with to revoke that sentence. St. Peter wrote a book on the Divinity, out of which some quotations are preserved in the councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon. 3 Also a paschal treatise of which some fragments are extant. 4 From St. Epiphanius 5 it appears that St. Peter was in prison for the faith in the reign of Dioclesian, or rather of Galerius Maximian; but after some time recovered his liberty. Maximin Daia, Cæsar in the East, renewed the persecution in 311, which had been considerably abated by a letter written the same year by the emperor Galerius in favour of the Christians. Eusebius informs us, that Maximin coming himself to Alexandria, St. Peter was immediately seized, when no one expected such a storm, and, without any form of trial, by the sole order of the tyrant, hurried to execution. With him were beheaded three of his priests, Faustus, Dio, and Ammonius. This Faustus seems, by what Eusebius writes, to be the same person of that name who, sixty years before, was deacon to St. Dionysius, and the companion of his exile. 6

The canons of the church are holy laws framed by the wisest and most experienced pastors and saints for the regulation of the manners of the faithful, according to the most pure maxims of our divine religion and the law of nature, many intricate rules of which are frequently explained, and many articles of faith expounded in them. Every clergyman is bound to be thoroughly acquainted with the great obligations of his state and profession: for it is one of the general and most just rules of the canon law, and even of the law of nature, that “no man is excused from a fault by his ignorance in things which, by his office, he is bound to know.” 7 That any one amongst the clergy should be a stranger to those decrees of the universal church and statutes of his own diocess, which regard the conduct and reformation of the clergy, is a neglect and an affected ignorance which aggravates the guilt of every transgression of which it is the cause, according to a well-known maxim of morality. After the knowledge of the holy scriptures, of the articles of faith, and the rules of a sound Christian morality, every one who is charged with the direction of others, is obliged to have a competent tincture of those parts of the canon law which may fall in the way of his practice: bishops and their assistants stand in need of a more profound and universal skill both in what regards their own office, (in which Barbosa 8 may be a manuduction) and others.

Note 1. Eus. Hist. l. 9. c. 6. p. 444. [back]

Note 2. Ap. Beveridge inter Canones Eccl. Græcæ. Item. Labbe, Conc. t. 1. [back]

Note 3. Conc. Ephes. Act. 1, p. 508. Act. 7, p. 836. (Conc. t. 3.) Conc. Chalced. Act. 1, p. 286. [back]

Note 4. Ap. Du Fresne, Lord Du Cange Pref. in Chron. Pasch. n. 7, p. 4. 5. [back]

Note 5. S. Epiph. hær. 68. [back]

Note 6. We have two sorts of acts of St. Peter’s martyrdom, the one published by Surius, the other from Metaphrastes, published by Combefis; both of no credit; and inconsistent both with themselves, and with Eusebius and Theodoret. [back]

Note 7. The canon law is founded upon, and presupposes in some cases the decisions of the civil or Roman law. But for this, Corvinus’s Abstract, or Vinnius upon the Institutes, or some parts of Syntagma Juris Universi per Petr. Gregorinm; or the French advocate, John Domat’s immortal work, entitled, Les Loix Civiles dans leur Ordre Naturel, will be a sufficient introduction. The canon law may be begun by Fleury’s Institutions au Droit Ecclésiastique. The decrees of the general councils should follow, and those of our own country, by Spelman or Wilkins, &c. or Cabassutius’s Epitome of the Councils, the second edition, in folio: then Antonii Augustini Epitome Juris Pontificii, and his excellent book De Emendatione Gratiani, with the additions of Baluze. At least some good commentator on the Decretals must be carefully studied as Fagnanus, Gonzales, Reiffenstuel, or Smaltzgruben; for the new ecclesiastical law, the decrees of the council of Trent, and some other late councils, those especially of Milan: the important parts of the latest bullaries of Clement XII. and Benedict XIV. with Barbosæ Collectanea Bullarii. Van Espen is excellent for showing the origin of each point of discipline; but is to be read with caution in some few places. The French advocate, Lewis d’Hericourt’s Droit Ecclésiastique François is esteemed; but the author sometimes waded out of his depth. This may serve for a general plan to those clergymen who have an hour a day to bestow on this study, and are only deterred from it by wanting an assistant to direct them in it. Those who have not this leisure or opportunity of books, may content themselves with studying some good author who has reduced this study into a regular method, or short collection. Cabassutius’s Theoria et Praxis Juris Canonici is accurate; that of Pichler, in five small volumes, is full, clear, and more engaging: but his relaxed principles concerning usury (which, by order of Pope Benedict XIV. were confuted by Concina, a Dominican friar) must be guarded against. With such helps any one may easily make himself master of those parts which are necessary in his circumstances. How scandalous it is to see a minister of God ready enough to study the extent of the laws concerning parish dues, and strain them in favour of his avarice, yet supinely careless in learning the duties of his ministry and his grievous obligations to God and his flock? The fatal neglect of those wholesome laws which were framed to set a bar to vice and human passions, to fence the ecclesiastical order against the spirit of the world breaking in upon it, and to check a relaxation of manners which tends utterly to extirpate the spirit of Christ among the laity, will excuse, it is hoped, this short note upon a subject which deserves so much to be strongly inculcated. [back]

Note 8. Barboaa, De Officio Episcopi. Item De Officio Parochi. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume XI: November. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/11/261.html

Weninger’s

Lives of the Saints – Saint Peter, Patriarch of Alexandria, Martyr

Article

Saint Peter, a man of

great virtue and learning, was patriarch of Alexandria, his native city. At the

time when the Emperors, Dioclesian and Maximian, endeavored to extirpate the

Christian religion, he did all in his power to strengthen the Christians in the

true faith and encourage them to prepare for martyrdom. He himself desired

nothing more ardently than to give his life for Christ’s sake; but the faithful

forced him to conceal himself until the persecution ceased. Hardly had this

storm abated, when Meletius, a bishop, gave him new trouble, by promulgating

heretical dogmas, and committing other crimes, for which Saint Peter had to

depose him from his see and excommunicate him. The conduct and the doctrine of

Meletius were defended, in defiance of Saint Peter, by Arius, a proud and

ambitious priest of Alexandria; and as neither prayers nor threats could move

Arius to desist from such unjust and wicked proceedings, the zealous Patriarch

saw himself obliged to separate him also, by excommunication, from the Church

of Christ.

During this schism of the

Church, an imperial officer arrived at Alexandria, seized Saint Peter, and cast

him into a dungeon. Arius thought that, after the death of Saint Peter, he

would surely succeed to the patriarchal chair if he were reconciled to the

Church. He therefore pretended to repent of his fault, and going to the clergy,

he requested them to beg the Patriarch to revoke the sentence of

excommunication, declaring that he had abandoned the cause of Meletius, and was

resolved to live and die a Catholic. Achillas and Alexander, moved by his

deceitful words,, begged Saint Peter to grant the request. The Patriarch,

enlightened by God, replied with a deep sigh: “I know that Arius is full of

hypocrisy and blasphemy; how can I receive him again into the Church? You must

know that in excommunicating him, I have not acted of my own accord, but by

inspiration from the Almighty. Only last night, Christ appeared to me in the

form of a beautiful youth, clothed in a snow-white garment, which was sadly

rent. I was terrified, and asked: ‘Lord, what is the meaning of this? Who has

torn Thy robe?’ He answered: ‘Arius has done it; for, by his heresy, he has

divided My Church and will make the rent still larger.'” Peter added that

Christ had forbidden him to receive Arius again into the pale of the Church,

and commanded Achillas and Alexander also to reject him, when they would, one

after the other, succeed to the patriarchal chair. Having said this, the Saint

admonished them to guard, with fatherly care, the flock of Christ, and then,

with his blessing, dismissed them. Soon after, by command of the emperor, Saint

Peter was dragged to the place of execution, without having had a trial. The

Christians endeavored to interfere; but the Saint hastened joyfully to the spot

where he was to receive the crown of martyrdom. His death happened in the year

310. The Christians carried the holy body into the Church, clothed it in the

pontifical robes, and placed it upon the chair of Saint Mark, on which Peter’s

humility and his reverence for the holy Evangelist had never allowed him to sit

in his lifetime, as he always sat down on one of the steps leading to it.

Having for some time showed all due honors to the holy body, they laid it into

the tomb.

Practical Considerations

Saint Peter is one of

those glorious martyrs, who joyfully hastened to the place of execution to give

their lives for the true faith. Have you not sometimes desired that you had

lived at that period, and given your blood for Christ? I praise you for having

had such a pious wish. But as you have no occasion now to die a martyr for the

love of the Saviour, endeavor at least to live for Him, and to be a martyr

without shedding your blood. How can this be done? Origen says: “We can be

martyrs without shedding our blood, by patiently bearing crosses and trials. In

like manner speaks Saint Bernard, when he says: “By preserving true patience

continually in your mind, you may become a martyr without the sword.” Saint

Gregory says the same, and remarks, also: “To bear wrongs and persecutions

patiently, and to love our enemy, is a kind of martyrdom.” “It is martyrdom,”

says Saint Chrysostom, “when we bear poverty patiently for God’s sake.” “If a

Christian,” writes Saint Augustine, “lives according to the gospel, his entire

life is one cross, one long martyrdom.” The same holy teacher instructed us, on

a former occasion, that we are martyrs by conquering our passions, by avoiding

lust, by preserving justice, by despising avarice and by restraining pride. In

a sermon of Saint Lawrence, we read that “martyr,” according to the Greek, means

“witness.” “As often, therefore,” says he, “as we fulfill the commands of

Christ, and do good, so often are we witnesses of the Lord, and in that sense,

martyrs.” Hence you may become a martyr of Christ, in this manner and you will

find frequent opportunity for it. Endeavor, therefore, to bear patiently

crosses and sufferings; live according to the Gospel of the Lord; moderate your

passions; be chaste, and avoid all vices; let your conduct be witness of your

fidelity to your Lord Jesus Christ, and you will be a true, though bloodless,

martyr.

MLA

Citation

Father Francis Xavier

Weninger, DD, SJ. “Saint Peter, Patriarch of Alexandria, Martyr”. Lives of the Saints, 1876. CatholicSaints.Info.

26 May 2018. Web. 23 May 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/weningers-lives-of-the-saints-saint-peter-patriarch-of-alexandria-martyr/>

Vision

des Petrus von Alexandrien; Detail: Arius wird von einem Drachen verschlungen

Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur:

object 20332464 –

image file fmlac10835_21a.jpg

Vision of Peter of Alexandria; detail: Arius is devoured by a dragon

Hieromartyr Peter,

Archbishop of Alexandria

Commemorated on November 25

The Holy Hieromartyr

Peter, Archbishop of Alexandria, was born and raised at Alexandria. He was a

highly educated man, and was head of the school of Alexandria. In the year 300

he became the archpastor of the Alexandrian Church, succeeding his teacher and spiritual

guide, the holy Bishop Theonas.

Forced into exile from

the city during the anti-Christian persecutions under the emperors Diocletian

and Maximian, Saint Peter traveled through many lands, encouraging his flock by

letter. Again returned to his city, in order to guide the Alexandrian Church

personally during this dangerous period. The saint secretly visited Christians

locked up in prison, encouraging them to be steadfast in faith, assisting the

widows and orphans, preaching the Word of God, constantly praying and

officiating at the divine services. And the Lord kept him safe from the hands

of the persecutors.

During this time of

unrest the iniquitous heretic Arius, who denied the divinity of Jesus Christ,

sowed the tares of his impious teaching. When Arius refused to be corrected and

submit to the truth, Saint Peter anathematized the heretic and excommunicated

him from the Church. Arius then sent two of Saint Peter’s priests to beg the

saint to lift the excommunication from him, pretending that he had repented and

given up his false teachings. This was not true, for Arius hoped to succeed

Saint Peter as Archbishop of Alexandria. Saint Peter, under the guidance of the

Holy Spirit, saw through the wickedness and deceit of Arius, and so he

instructed his flock not to believe Arius nor to accept him into communion.

Under the wise nurturing

of Saint Peter the Church of Alexandria strengthened and grew in spite of the

persecutions. But finally, on orders from the emperor Maximian (305-311), the

saint was arrested and sentenced to death. A multitude of people gathered at

the entrance of the prison, expressing their outrage. Wanting to avoid

bloodshed and a riot by the people, the saint sent a message to the

authorities, in which he suggested that they make an opening in the back wall

of the prison, so that he might be taken away secretly to execution.

In the dark of the night

Saint Peter went with the executioners, who took him beyond the city walls and

beheaded him at the same spot where formerly Saint Mark had been executed. That

night a certain pious virgin heard a Voice from heaven saying, “Peter was first

among the Apostles; Peter is the last of the Alexandrian Martyrs.” This took

place in the year 311. In the morning, when people learned of the death of their

bishop, a crowd gathered at the place of execution. They took up the body and

head of the martyr and went to the church, dressing him in his bishop’s

vestments, they sat him in his throne at the high place in the altar. During

his life Saint Peter never sat on it, but sat on a footstool instead. The saint

once explained that whenever he approached his throne he beheld a heavenly

light shining on it, and he sensed the presence of a divine power. Therefore,

he didn’t dare to sit there.

The Lord Jesus Christ

once appeared to Saint Peter as a twelve-year-old child wearing a robe that was

torn from top to bottom. Saint Peter asked the Savior who had torn his garment,

and He replied, “That madman Arius has torn it by dividing the people whom I

have redeemed by My blood. Do not receive him into Communion with the Church,

for he has worked evil against Me and My flock.”

Saint Peter, a great

champion of Orthodoxy, is known also as a profound theologian. Passages from

his book, “On the Divinity (of Jesus Christ)”, were consulted at the Councils

of Ephesus and Chalcedon. Of all his works, the most widely known and highly

esteemed by the Church are his “Penitential Canons”.

SOURCE : https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2025/11/25/103394-hieromartyr-peter-archbishop-of-alexandria

Icona

con San Pietro I di Alessandria

Santi Pietro

d’Alessandria, Esichio, Pacomio e Teodoro e compagni Martiri

Festa: 25 novembre

† Alessandria d’Egitto,

25 novembre 311

San Pietro, vescovo di

Alessandria d’Egitto, era un uomo dotato di tutte le virtù. Nel 311 venne

inaspettatamente condannato a morte per ordine dell’imperatore Massimiano,

ultima vittima e sigillo di una spietata persecuzione contro la Chiesa. Insieme

con lui si ricordano tre santi vescovi egiziani, Esichio, Pacomio e Teodoro e

molti altri cristiani, che sempre presso Alessandria e nella stessa

persecuzione vennero assassinati a colpi di spada.

Martirologio

Romano: Ad Alessandria d’Egitto, san Pietro, vescovo e martire, che,

ornato di ogni virtù, fu improvvisamente decapitato per ordine dell’imperatore

Galerio Massimiano, divenendo ultima vittima della grande persecuzione e

sigillo dei martiri. Con lui si commemorano tre vescovi egiziani, Esichio,

Pacomio e Teodoro, che, sempre ad Alessandria patirono insieme a molti altri

nella stessa persecuzione e salirono al cielo crudelmente trafitti con la

spada.

Nonostante l’assoluta inattendibilità della “passio” di San Pietro, egli è menzionato parecchie volte dal grande storico ecclesiastico Eusebio di Cesarea, che lo descrive quale eccellente insegnante della religione cristiana, nonché come un grande vescovo. Nulla di certo si sa circa le sue origini e la sua provenienza, in quanto fa la sua prima comparsa sulla scena ecclesiale quando viene chiamato a succedere nel 300 a San Teonio sulla cattedra episcopale di Alessandria. Governò così questa Chiesa per circa una dozzina d’anni. Dopo i primi tre anni, dovette sopportare la feroce persecuzione dioclezianea, proseguita anche dai successori di tale imperatore. Divenne celebre per il suo prodigarsi in aiuto dei fratelli cristiani perseguitati. Com’è immaginabile, non tutti riuscirono a restare saldi nella fede essendo sottoposti a torture e toccò dunque a Pietro, la cui giurisdizione si estendeva su tutte le chiese d’Egitto, della Tebaide e della Libia, redigere delle istruzioni volte a regolare il trattamento di coloro che, pur avendo in un primo momento rinnegato la fede cristiana, desideravano riconciliarsi con la Chiesa.

Infine anche Pietro dovette inevitabilmente nascondersi e durante la sua assenza da Alessandria la chiesa egiziana subì uno scisma, le cui cause non sono però ben chiare. Pare che Melezio, vescovo di Antiochia, si fosse assunto la responsabilità di esercitare le funzioni metropolitane spettanti al legittimo vescovo alessandrino. Onde giustificare le sue azioni, diffuse alcune calunnie sul conto di Pietro, accusandolo di troppa indulgenza verso coloro che cadevano in errore. Rifiutando di ritirarsi, a Pietro non rimase altra alternativa che scomunicarlo, continuando nel frattempo a governare la sua Chiesa sino a quando non poté fare finalmente ritorno in città. La persecuzione anticristiana riprese però ben presto con Massimino Daia e nel 311 Pietro venne catturato inaspettatamente e giustiziato seduta stante senza accuse né processo.

In Egitto è conosciuto come “il sugello e il complemento della persecuzione”, in quanto fu l’ultimo martire condannato a morte dalle pubbliche autorità presso Alessandria. E’ inoltre ricordato come “colui che attraversò il muro”, in riferimento alla leggenda secondo cui, quando Pietro si accorse che le autorità erano pronte a massacrare l’enorme folla di cristiani riunitasi in segno di protesta fuori della prigione ove era detenuto, suggerì al comandante di aprire un varco nel muro approfittando delle tenebre affinché il boia potesse entrare senza essere intralciato dalla folla.

Il Martyrologium Romanum lo commemora ancora oggi nell’anniversario della sua nascita al cielo. Insieme con lui si ricordano anche tre santi vescovi egiziani, Esichio, Pacomio e Teodoro, nonché molti altri cristiani, che sempre presso Alessandria e nella stessa persecuzione vennero assassinati a colpi di spada.

Autore: Fabio Arduino

SOURCE : https://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/92837

Detail van 19e- of 20e-eeuwse reliekhouder van diverse heiligen in de Schatkamer van de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwebasiliek in Maastricht. Boven: relieken van Sint-Markus (de evangelist), Sint-Rochus en Sint-Sebastiaan. Reliquaire du XIXe ou XXe siècle de divers saints dans le Trésor de la Basilique Notre-Dame de Maastricht. Ci-dessus : reliques de Saint Marc (l'évangéliste), Saint Roch et Saint Sébastien. Ci-dessous : la partie supérieure de la fibule droite de saint Pierre d'Alexandrie.

Detail

van 19e- of 20e-eeuwse reliekhouder van diverse heiligen in de Schatkamer van

de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwebasiliek in Maastricht. Boven: relieken van Sint-Markus (de

evangelist), Sint-Rochus en Sint-Sebastiaan. Onder: het bovenstuk van het

rechter kuitbeen van de H. Petrus van Alexandrië. In 1930 werd dit

reliekschrijntje door kapelaan Welters omschreven als: "In zilveren doosje

worden bewaard kostbare relieken van het H. Kruis en van de doornenkroon des

Heeren". Wanneer de relieken verwisseld zijn is niet bekend.

Détail du reliquaire du XIXe ou XXe siècle de divers saints dans le Trésor de la Basilique Notre-Dame de Maastricht. Ci-dessus : reliques de Saint Marc (l'évangéliste), Saint Roch et Saint Sébastien. Ci-dessous : la partie supérieure de la fibule droite de saint Pierre d'Alexandrie. En 1930, ce reliquaire fut décrit par l'aumônier Welters comme suit : « De précieuses reliques de la Sainte Croix et de la Couronne d'épines du Seigneur sont conservées dans une boîte en argent ». On ne sait pas quand les reliques ont été échangées.

Petrus van Alexandrië,

Egypte; bisschop & martelaar met nog 3 bisschoppen en vele

medechristenen; † 311.

Feest 25 [Mty.2001] &

26 (voorheen) november.

Hij was in 300 zijn

voorganger Theonas († ca 300; feest 23 augustus) opgevolgd en wordt een van de

meest verlichte en geleerde mannen van zijn tijd genoemd. Met veel liefde en

geduld stond hij de christenen terzijde die tijdens de vervolgingen onder Maximianus

Galerius (284-305) vervolgd werden.

Hij voorspelde zijn

diaken Aríus welk een desastreuze invloed zijn ketterse ideeën op de christenen

van de komende tijd zou hebben.

Keizer Maximianus'

opvolger Maximinus Daia (305-311) hervatte na enige jaren de christenvervolgingen;

bisschop Petrus behoorde tot de eerste slachtoffers. Het was tragisch dat in

een tijd van ernstige christenvervolgingen zijn eigen geestelijkheid zo

verdeeld was over dogmatische vraagstukken van wezenlijk belang.

Door sommige bronnen worden

met hem nog drie bisschoppen genoemd: Hesychius, Pachomius en Theodorus.

Maar die kwamen we ook al tegen bij Faustus († 311; feest 26 november).

Daarnaast werden nog vele andere christenen om het leven gebracht.

[000»Alex.Newski; Bdt.1925; Bly:.1986p:228; Bri.1953; RR2.1690»26nov;

SBy.1982p:31; Dries van den Akker s.j./2005.08.16]

© A. van den Akker

s.j. / A.W. Gerritsen

SOURCE : https://www.heiligen-3s.nl/heiligen/11/25/11-25-0311-petrus.php

Saint Pierre d’Alexandrie

- Programme

du IVème dimanche après la Pentecôte – saint Eusèbe de Samosate – ton 3 - 2

juillet 2020 par Henri de Villiers :

https://schola-sainte-cecile.com/tag/saint-pierre-dalexandrie/

Extracts from Peter of Alexandria (d.311) and the original copy of the Gospel of John, Posted on July 20, 2019 by Roger Pearse : https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/2019/07/20/extracts-from-peter-of-alexandria-d-311-and-the-original-copy-of-the-gospel-of-john/

Cronologia del Patriarcato di Alessandria e cronotassi dei Vescovi e (dal 325) Patriarchi di Alessandria : http://atlasofchurch.altervista.org/comuni/alessandria.htm

.jpg)